Spare a thought for all the mortal goal-scoring experts the current Bundesliga has to offer. Keyword: mortal. Because whatever Robert Lewandowski and Timo Werner are currently doing in front of goal must be illegal in some countries. The prolific Bayern striker and the lightning-quick frontman of RB Leipzig stand at goal tallies of 16 and 12, respectively, 12 matchdays into the 2018–19 season. While Lewandowski and Werner have been in ludicrous form so far, the standout performances the two stars get all the attention and glory. So let us — we, fair people at StatsBomb — shine some light on the ‘other’ goal scorers one can find in the highest level of German pro football. Exempting those two, there are seven players who have scored at least six goals this campaign. Sorry, Marcus Thuram (five goals), Serge Gnabry (four goals plus one glorious moustache) and Jadon Sancho (four), but you awesome youngsters will surely come up in a future Bundesliga digest on this here fine website. The seven non-alien penalty box poachers can be divided into four categories. The question is — are these guys for real, or just on a very nice hot streak?

The (fairly) unknowns

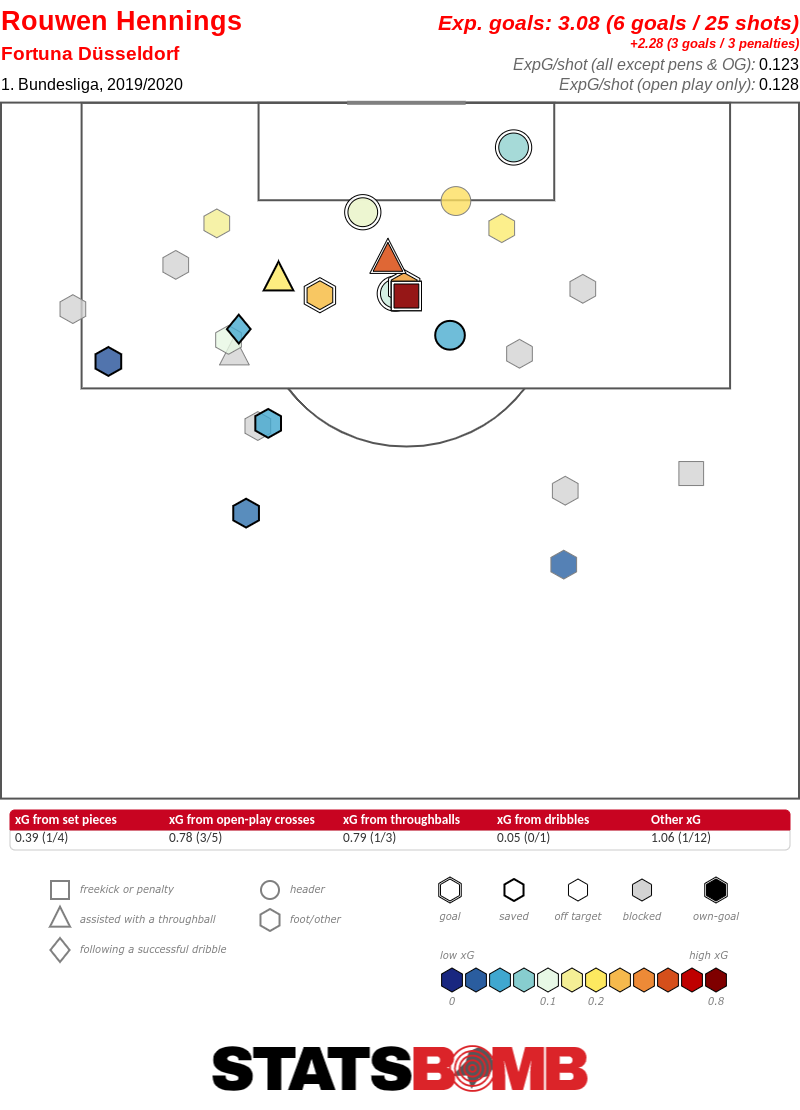

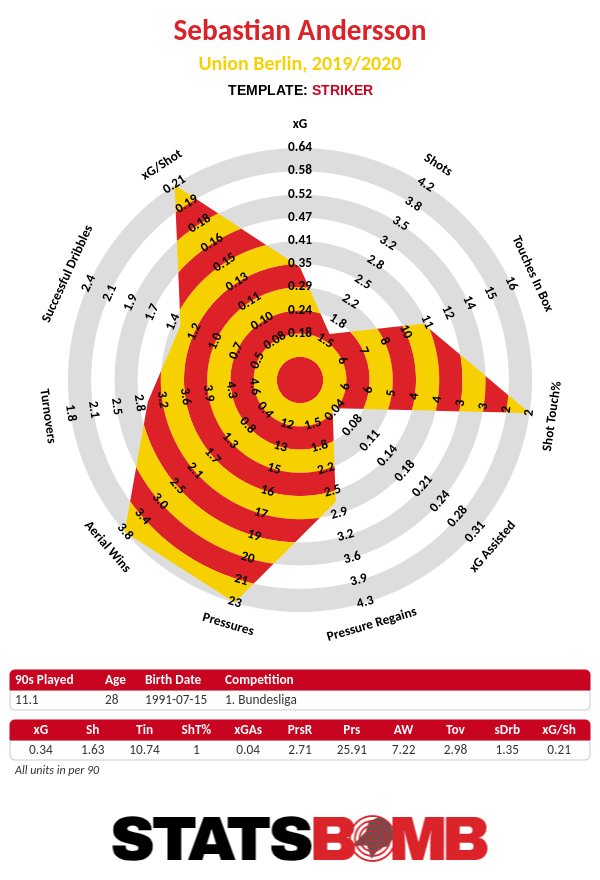

A big, big shoutout to Rouwen Hennings. The 32-year old Fortuna Düsseldorf attacker flopped at Burnley just three years ago. After being a bench-warmer during their 2016–17 Championship campaign, Hennings was let go on a free transfer after Düsseldorf was promoted. The veteran lefty is now enjoying the best season of his career — which took him to four other German clubs in the lower-level leagues — by a wide margin. Hennings has already scored nine goals this Bundesliga season, three from the penalty spot, the rest from, ehm, quite the hot finishing touch he's applied in and around the box. Fortuna players not named Hennings have just mustered six goals in twelve league games so far, so the streaky shooting of their frontman has been more than welcome in the early months of a season that has the makings of a tough relegation battle for Düsseldorf.  The other fairly anonymous name toward the top of the Bundesliga’s goal scorers charts seems to have more staying power given his all-around skills. Sebastian Andersson (28) is utterly crucial to surprise outfit Union Berlin. The Christmas carol club from the capital city is on a three-game winning streak, with Andersson scoring three crucial goals in the last two wins (a brace in the 2–3 road win at Mainz, the stoppage time clincher in a 2–0 home upset of Mönchengladbach). The 6'3" frontman is surprisingly mobile for someone his size, and his off-ball work rate is solid. Andersson may have developed later, but he's still got plenty of years left, and his aerial prowess and diligent pressing make him a reasonable option as a target man in a 4-4-2 formation, should things change at Union, or Sweden call him up. He may not take a lot of shots, with only 1.63 per 90, but when he does, they're lethal. He's averaging a sky-high 0.21 expected goals per shot.

The other fairly anonymous name toward the top of the Bundesliga’s goal scorers charts seems to have more staying power given his all-around skills. Sebastian Andersson (28) is utterly crucial to surprise outfit Union Berlin. The Christmas carol club from the capital city is on a three-game winning streak, with Andersson scoring three crucial goals in the last two wins (a brace in the 2–3 road win at Mainz, the stoppage time clincher in a 2–0 home upset of Mönchengladbach). The 6'3" frontman is surprisingly mobile for someone his size, and his off-ball work rate is solid. Andersson may have developed later, but he's still got plenty of years left, and his aerial prowess and diligent pressing make him a reasonable option as a target man in a 4-4-2 formation, should things change at Union, or Sweden call him up. He may not take a lot of shots, with only 1.63 per 90, but when he does, they're lethal. He's averaging a sky-high 0.21 expected goals per shot.  The third ‘unknown’ finding the net with surprising ease is discussed in StatsBomb’s guide of Bundesliga break-out players, published earlier this season. Gonçalo Paciência’s mix of on-ball skill, positional awareness and aggressive play means he's the number one option in Eintracht Frankfurt’s rotation of strikers. A nice achievement for the 25-year-old Portuguese attacker, given the big-name competition in André Silva and Bas Dost. Paciência looks to have leapfrogged his Silva as well in the Portugal national team hierarchy.

The third ‘unknown’ finding the net with surprising ease is discussed in StatsBomb’s guide of Bundesliga break-out players, published earlier this season. Gonçalo Paciência’s mix of on-ball skill, positional awareness and aggressive play means he's the number one option in Eintracht Frankfurt’s rotation of strikers. A nice achievement for the 25-year-old Portuguese attacker, given the big-name competition in André Silva and Bas Dost. Paciência looks to have leapfrogged his Silva as well in the Portugal national team hierarchy.

Nils Petersen is still ‘Nils-ing’

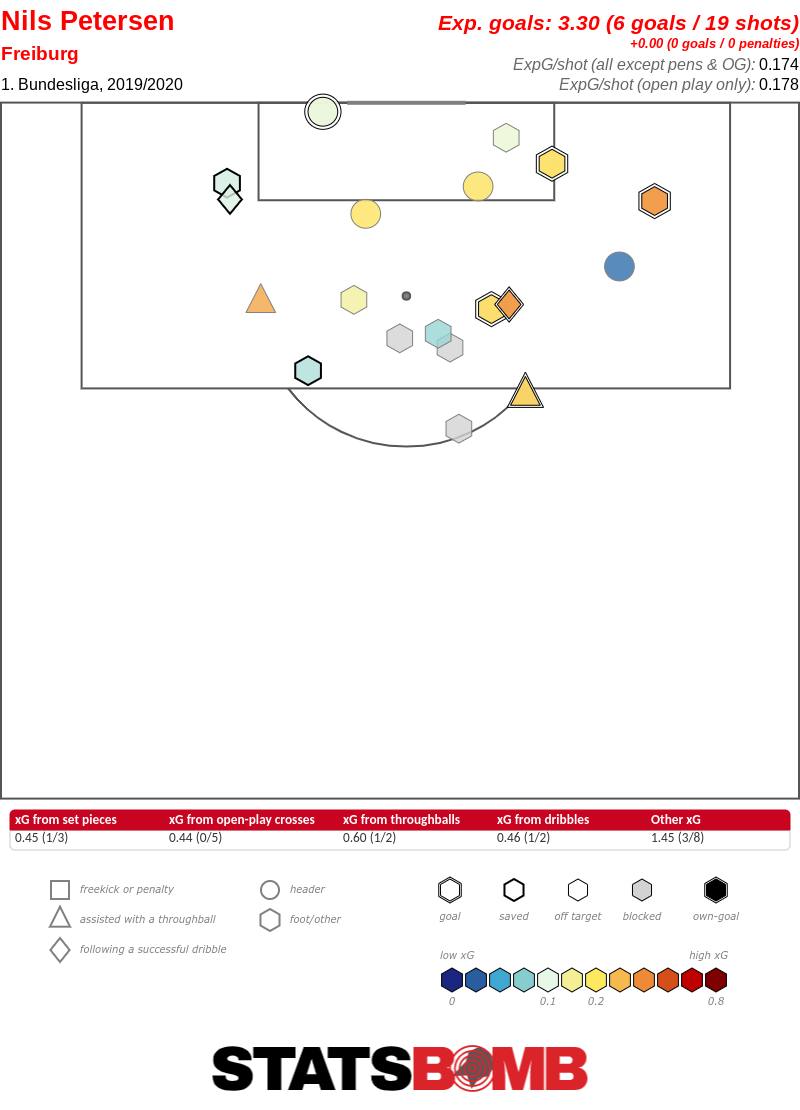

No, Petersen is not the most elegant player to grace the Bundesliga pitches. But his somewhat janky-looking playing style leaves him perpetually underrated. The Freiburg striker continues to do what he does: score some goals. He’s scored six in twelve, bringing his total in the 1. Bundesliga to 50 goals in 113 league games. Just look at this shot map, friends. Good ol’ Nils sure knows what a good shooting opportunity looks like, even if his goal total seems somewhat generous given the underlying xG.

Playmakers who ‘have to’ score to keep their offenses humming

Playmakers who ‘have to’ score to keep their offenses humming

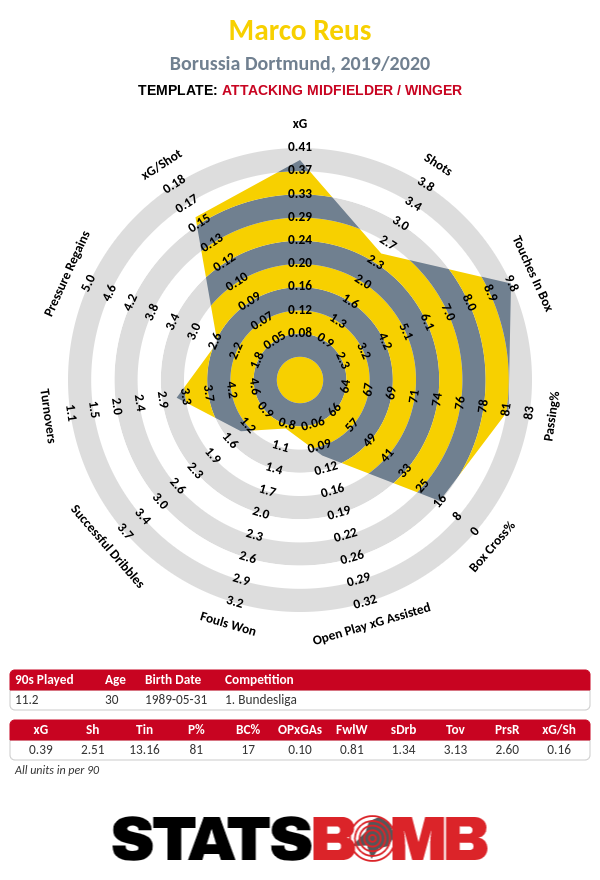

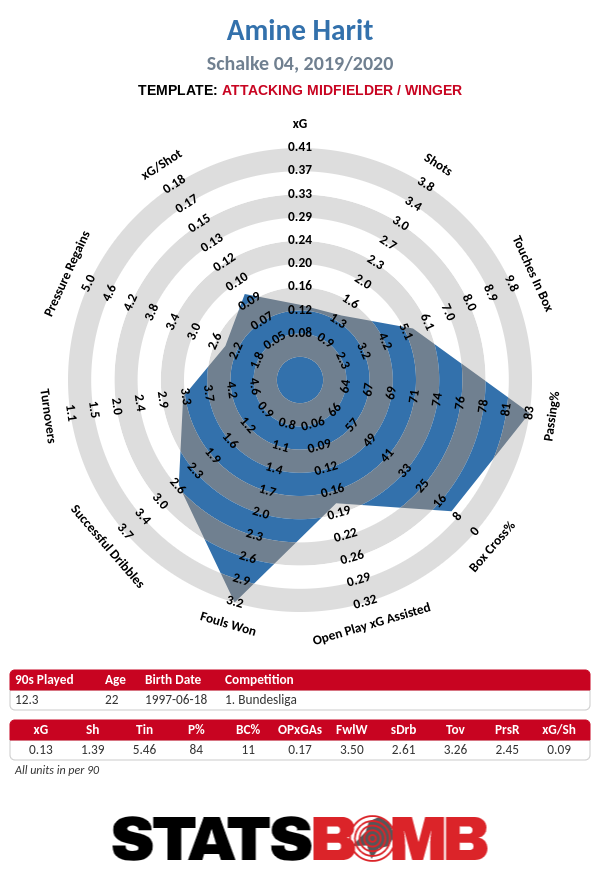

Please, I beg of you. Appreciate the greatness of Marco Reus while we still can. The injury-plagued superstar of Borussia Dortmund has, frustratingly, been turned into somewhat more of an out-and-out second striker under Lucien Favre than the free-wheeling playmaker slash wide creator slash box-hunting attacking force he was in years past. But Reus is still such a good player. Even in a team that is malfunctioning in all types of ways at the moment.  But while we’ve gotten used to Reus chipping in as a goalscorer as well as being the team’s main creative hub, Dortmund’s arch-rivals Schalke 04 have been pleasantly surprised by Amine Harit suddenly finding his scoring boots. The dribbling expert scored just four goals in 60 official games across all competitions in his first two seasons for the Königsblauen. Yet this season he's scored six already, and two have been late game-winners. If the 22-year-old attacking midfielder is able to continue in adding goal-scoring to his already impressive skill-set, we might see his silky smooth dribbles at a bigger club than Schalke sooner rather than later. If Harit is set on achieving that, he’ll need to improve his shot decisions quickly, though.

But while we’ve gotten used to Reus chipping in as a goalscorer as well as being the team’s main creative hub, Dortmund’s arch-rivals Schalke 04 have been pleasantly surprised by Amine Harit suddenly finding his scoring boots. The dribbling expert scored just four goals in 60 official games across all competitions in his first two seasons for the Königsblauen. Yet this season he's scored six already, and two have been late game-winners. If the 22-year-old attacking midfielder is able to continue in adding goal-scoring to his already impressive skill-set, we might see his silky smooth dribbles at a bigger club than Schalke sooner rather than later. If Harit is set on achieving that, he’ll need to improve his shot decisions quickly, though.  Harit really is doing a lot of things well with the ball at his feet; however, he is neither shooting a lot (1.39 shots per 90), nor taking high-value shots (0.09 xG per shot). If the goals are going to keep coming, at least one of those two things will have to change.

Harit really is doing a lot of things well with the ball at his feet; however, he is neither shooting a lot (1.39 shots per 90), nor taking high-value shots (0.09 xG per shot). If the goals are going to keep coming, at least one of those two things will have to change.

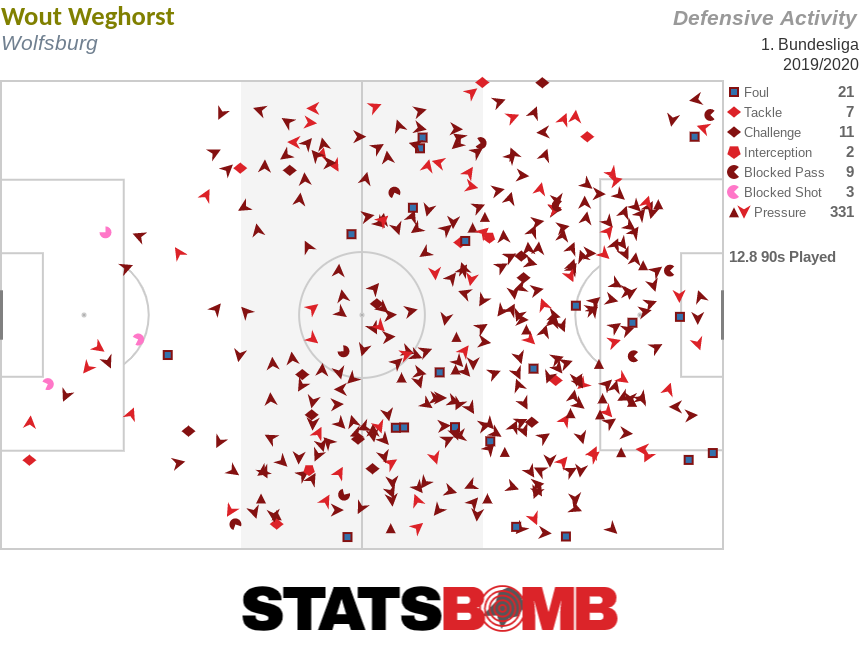

Big Wout keeps surprising

A little more than five years ago, Wout Weghorst was a back-up striker at lowly FC Emmen in the second tier of Dutch football. Weghorst was deemed too tall, too slow, too immobile and too stubborn to be the 'total striker’ Dutch coaches and scouts are often times obsessed with. But mid-level Eredivisie squad Heracles Almelo took a shine to Weghorst, who proved himself a useful target man up top in his first season at the highest level, and developed into a solid goalscorer in his second. Next up for the 6'6" Weghorst was a move to AZ Alkmaar. AZ? The analytically-driven club that ‘doesn’t do long crosses into the box’ signed the Eredivisie's only good aerial specialist? Yup. Turns out, Weghorst can do much more than win headers and poach goals in the box. The big frontman impressed at Alkmaar due to his almost-insane work rate when pressing the opposition’s build-up. When VfL Wolfsburg brought in Weghorst for a lofty (at the time) sum of 10.5 million Euros, Dutch pundits started their fourth ‘Weghorst cycle of doubt'. But really, this dude is just a fine footballer. It's just his size and incredible confidence he openly exudes at times can distract from his funky, but very useful, set of skills.

Here are some La Liga players doing good and/or interesting things so far this season.

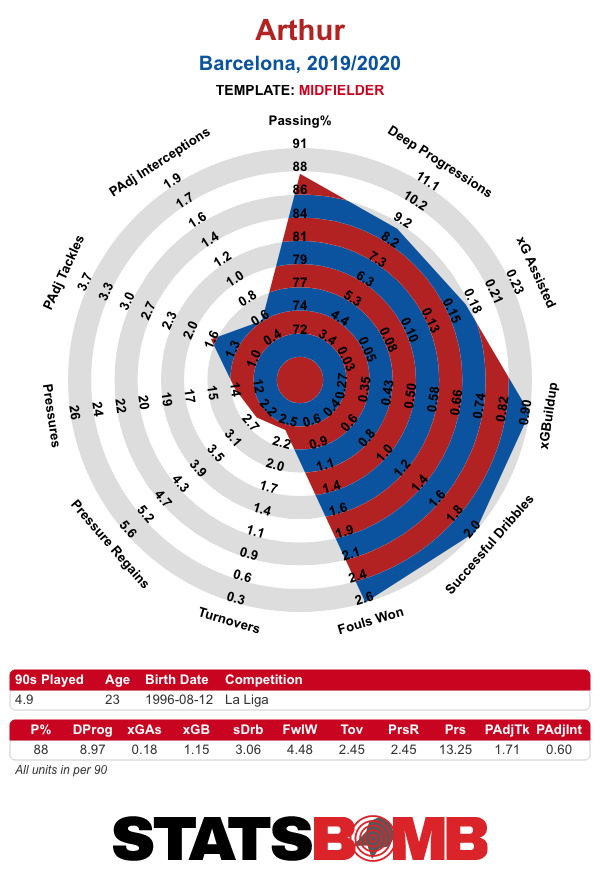

Arthur’s Increased Attacking Output

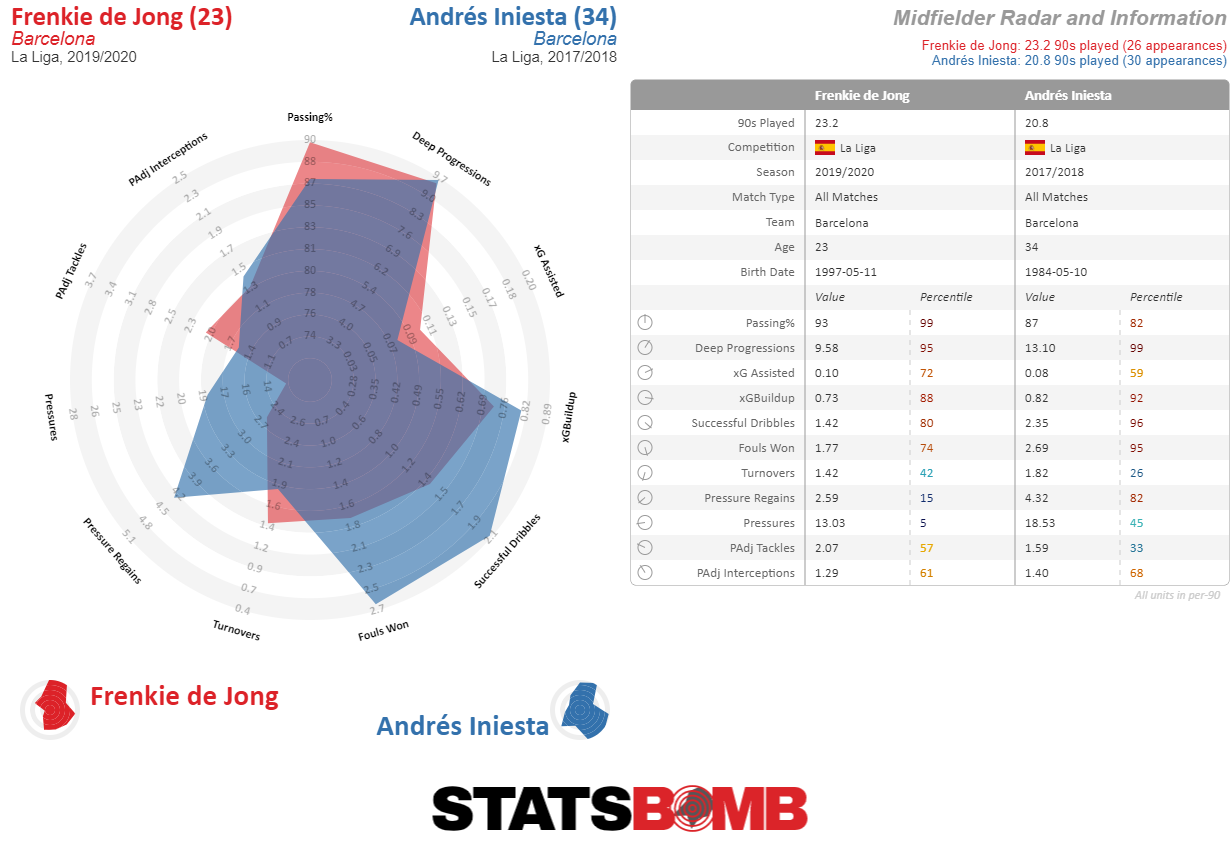

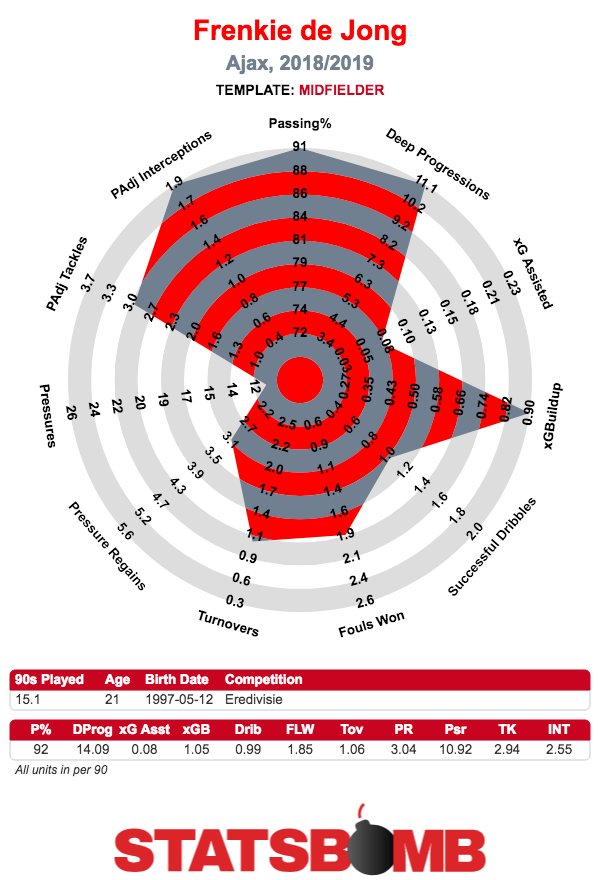

Frenkie de Jong has rightly taken plaudits for his good start at Barcelona (including a standing ovation from the Ipurua crowd in Saturday’s win away at Eibar). Despite a certain degree of awkwardness in set attacking situations, as is probably to be expected at this stage, in more open environments his movement and on and off-ball contributions have impressed.  Another member of the Barcelona midfield has also looked good. Last season, Arthur settled in well following his move from Gremio in Brazil. This time around, he has been set the target of increasing his attacking output by coach Ernesto Valverde. He has responded gamely, scoring his first goals for the club, doubling his through-ball and shot output, increasing his key pass and expected assist numbers, and taking a huge jump forward in terms of successful dribbles.

Another member of the Barcelona midfield has also looked good. Last season, Arthur settled in well following his move from Gremio in Brazil. This time around, he has been set the target of increasing his attacking output by coach Ernesto Valverde. He has responded gamely, scoring his first goals for the club, doubling his through-ball and shot output, increasing his key pass and expected assist numbers, and taking a huge jump forward in terms of successful dribbles.  Not since Andrés Iniesta in 2013/14 (thanks Messi Data Biography!) has a regular Barcelona midfielder completed over three dribbles per match. In an admittedly fairly low sample size that is exactly what Arthur is doing. A small, scampering figure of neat touches and tight turns, he has also carried a 100% success rate through his 15 dribble attempts to date (the most anyone else has completed without fail is Thomas Partey’s eight). Arthur has transitioned from more of a controlling role last season (with more deep progressions and a higher passing success rate) to a more aggressively forward-minded one. The arrival of De Jong has helped balance the midfield to make that possible. They are both very able ball-carriers (for the first time since Xavi and Iniesta’s last season together in 2014-15, Barcelona have a pair of regular midfielders who are both carrying the ball over 300 metres per 90), and while any statistical assessment of their impact is complicated by the fact that two of the four league matches they’ve started together have also been two of the three that Lionel Messi has started, on a subjective level, Barcelona’s best midfield lineup already looks to be the pair of them plus one other as circumstances dictate.

Not since Andrés Iniesta in 2013/14 (thanks Messi Data Biography!) has a regular Barcelona midfielder completed over three dribbles per match. In an admittedly fairly low sample size that is exactly what Arthur is doing. A small, scampering figure of neat touches and tight turns, he has also carried a 100% success rate through his 15 dribble attempts to date (the most anyone else has completed without fail is Thomas Partey’s eight). Arthur has transitioned from more of a controlling role last season (with more deep progressions and a higher passing success rate) to a more aggressively forward-minded one. The arrival of De Jong has helped balance the midfield to make that possible. They are both very able ball-carriers (for the first time since Xavi and Iniesta’s last season together in 2014-15, Barcelona have a pair of regular midfielders who are both carrying the ball over 300 metres per 90), and while any statistical assessment of their impact is complicated by the fact that two of the four league matches they’ve started together have also been two of the three that Lionel Messi has started, on a subjective level, Barcelona’s best midfield lineup already looks to be the pair of them plus one other as circumstances dictate.

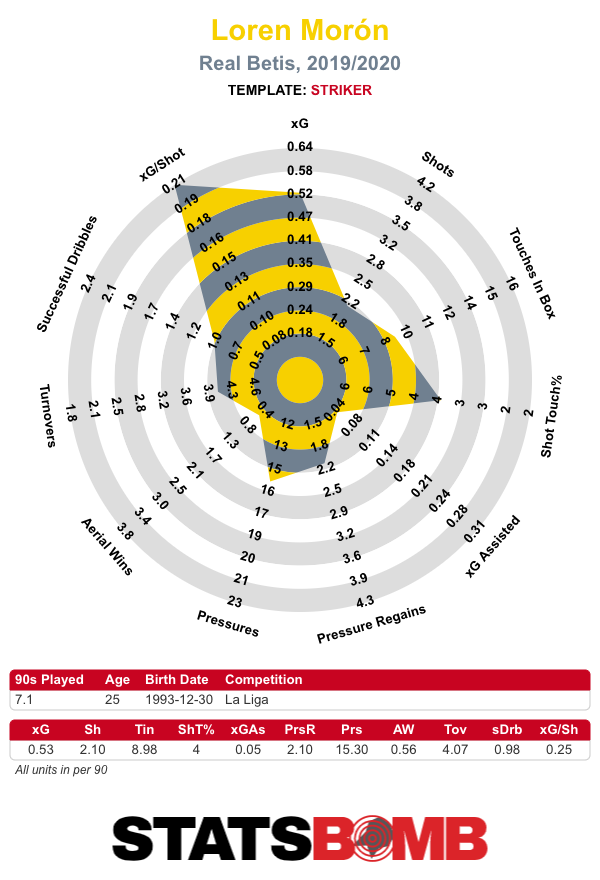

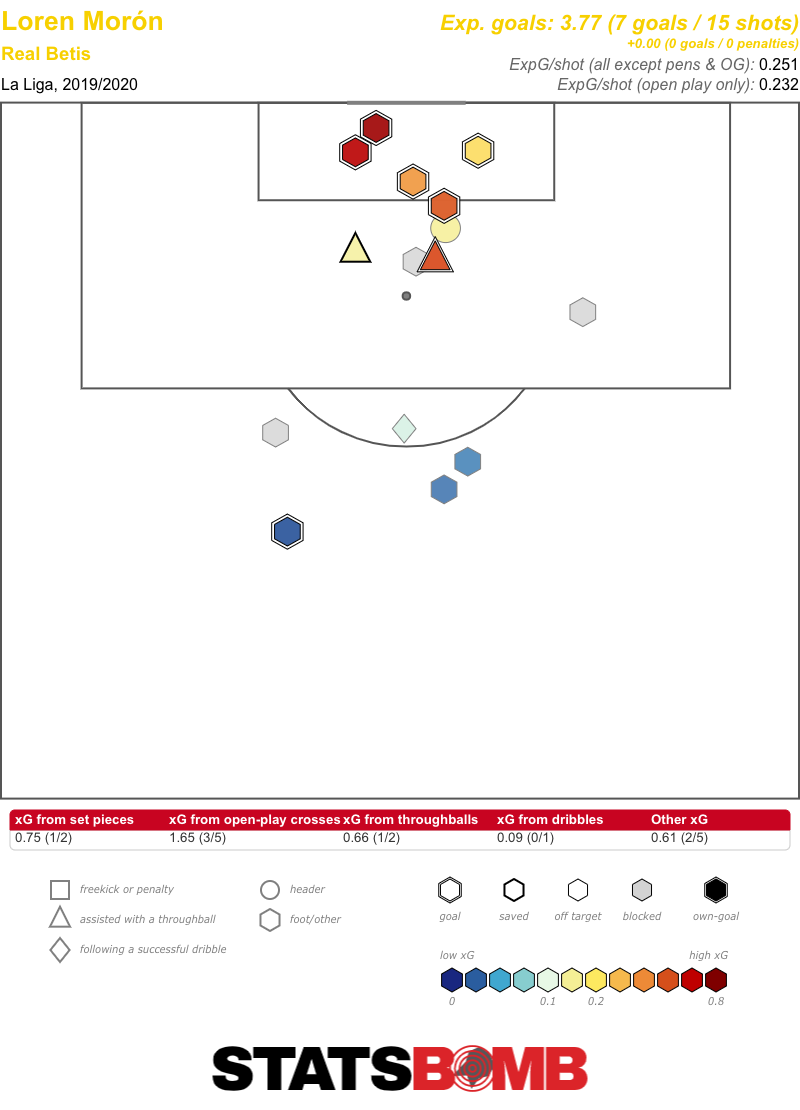

Loren Morón’s Scoring Start

Real Betis have made a disappointing start to the season and are currently down in the relegation zone. Amidst a series of structural and individual issues, one player has nevertheless managed to stand out. Loren Morón is La Liga’s top scorer, with seven goals. There has been a fair degree of over-performance in relation to his expected goals (xG), but even at an underlying level, the 25-year-old is still approximating the output of an elite striker.  Last season, only 12 players in the big five leagues recorded 0.50 or more xG per 90. Most of those were high volume shooters, with only two of them taking less than three shots per 90. Loren is averaging just over two so far, which does place a question mark over the sustainability of his output. In that group, Edinson Cavani has the most similar shot profile, but he plays for a dominant team in his league. Loren has shown himself to be a sharp and decisive presence inside the area, but he is relatively service reliant.

Last season, only 12 players in the big five leagues recorded 0.50 or more xG per 90. Most of those were high volume shooters, with only two of them taking less than three shots per 90. Loren is averaging just over two so far, which does place a question mark over the sustainability of his output. In that group, Edinson Cavani has the most similar shot profile, but he plays for a dominant team in his league. Loren has shown himself to be a sharp and decisive presence inside the area, but he is relatively service reliant.  It is also worth noting that at this stage last season, Loren sat on 0.48 xG per 90. Of the five players in the league who were averaging over 0.50 xG per 90 at that juncture, only one of them maintained it over the course of the entire campaign (although Levante’s Roger Martí came very close, at 0.49 xG per 90). Loren ended up with a seasonal average of 0.34 per 90, a smidgen up from his mark during his first half-season in the first team. Can he sustain his improved top-line and underlying numbers this time around?

It is also worth noting that at this stage last season, Loren sat on 0.48 xG per 90. Of the five players in the league who were averaging over 0.50 xG per 90 at that juncture, only one of them maintained it over the course of the entire campaign (although Levante’s Roger Martí came very close, at 0.49 xG per 90). Loren ended up with a seasonal average of 0.34 per 90, a smidgen up from his mark during his first half-season in the first team. Can he sustain his improved top-line and underlying numbers this time around?

Sergio Reguilón’s Attacking Impact

Sergio Reguilón showed enough in his minutes at Real Madrid last season to suggest that he was, at the very least, a competent top-flight performer with room for further growth. This season, on loan at Sevilla, he’s arguably been the best attacking full-back in La Liga. Sevilla’s system under Julen Lopetegui puts a lot of emphasis on the full-backs to get forward and support the attack, and in Reguilón he has a player who relishes the opportunity to constantly drive forward down the left. He is one of only seven players in La Liga to have carried the ball over 300 metres per 90, while only Samuel Chukwueze and Vinícius Junior have carried the ball at a greater average speed. Reguilón also stands out in just how often he gets forward into positions to shoot or assist. His tally of 3.35 shots and key passes per 90 is far more than that of any other full-back with a reasonable number of minutes, while his 4.77 touches inside the box per 90 is again a clear league high among players in his position. He looks comfortable carrying the ball into central areas, maintaining a good panorama of play and picking out some nice passes at pace. Here are his key passes to date:  Defensively, he looks better on the front foot and does struggle a bit with movement in and around him in more set situations. But that is something that can be refined over time. As it is, in Reguilón and Achraf Hakimi (on loan at Borussia Dortmund), Real Madrid have two young and talented full-backs capable of competing in the first team group next season if space opens up for them to do so.

Defensively, he looks better on the front foot and does struggle a bit with movement in and around him in more set situations. But that is something that can be refined over time. As it is, in Reguilón and Achraf Hakimi (on loan at Borussia Dortmund), Real Madrid have two young and talented full-backs capable of competing in the first team group next season if space opens up for them to do so.

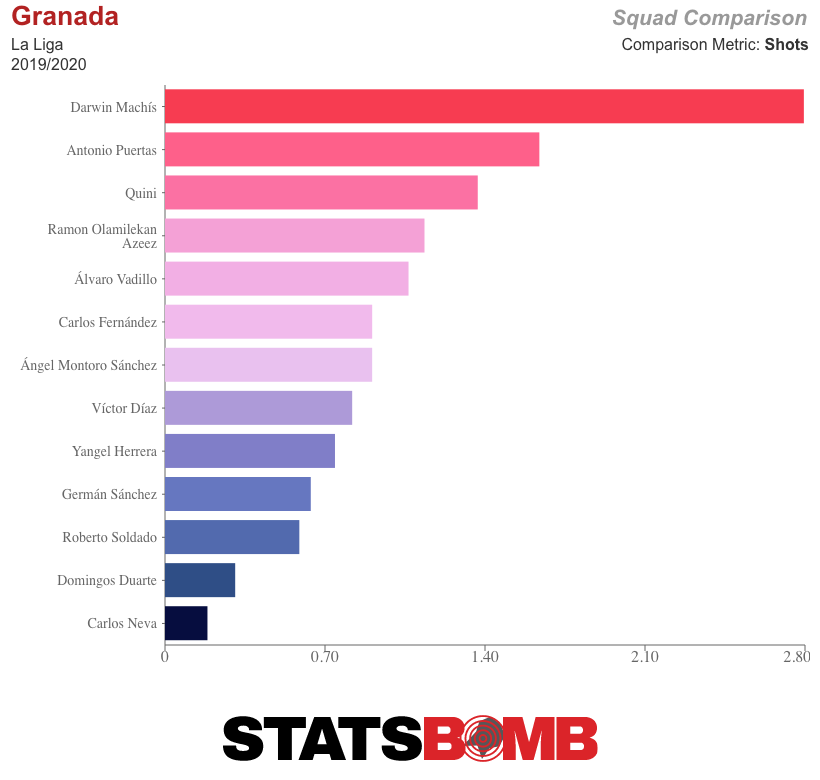

Darwin Machís: Shot Machine

Granada have exceeded all expectations on their return to the top flight. They are up in third, just two points behind leaders Barcelona and with the opportunity to go top, at least for a time, with victory at home to Real Betis on Sunday. Theirs has primarily been a collective triumph, but certain individuals have still shone. Goalkeeper Rui Silva has been a solid and assured presence, while Ángel Montoro has proved to be a key ball-progressor and creative force from both open play and set pieces. But the Granada player with the most interesting statistical profile is probably Darwin Machís. He doesn’t really seem to do anything other than carry, dribble and shoot. He attempts fewer passes than all but one of his teammates, carries the ball further that any of them (at one of the quickest speeds in the division), completes far more dribbles than any of them, and also clearly leads the way in terms of shots per 90.  A league-third-high (amongst players with at least 400 minutes) 4.53% of his total touches to date have been shots. They’ve not exactly been a stellar selection of efforts:

A league-third-high (amongst players with at least 400 minutes) 4.53% of his total touches to date have been shots. They’ve not exactly been a stellar selection of efforts:  But within the context of a team who don't necessarily have the personnel to consistently create good looks in open play, a player capable of advancing upfield and getting off shots can still form a useful part of a wider and more varied game plan.

But within the context of a team who don't necessarily have the personnel to consistently create good looks in open play, a player capable of advancing upfield and getting off shots can still form a useful part of a wider and more varied game plan.

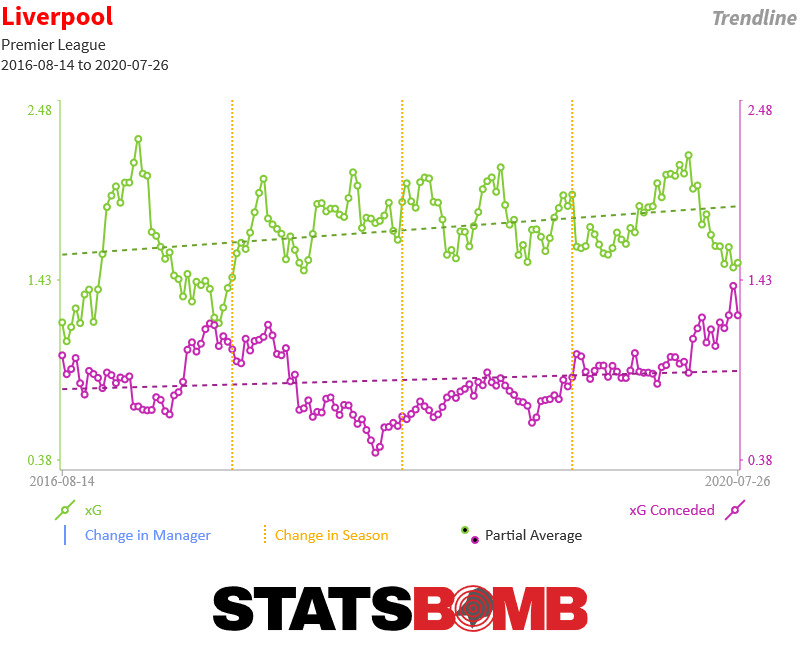

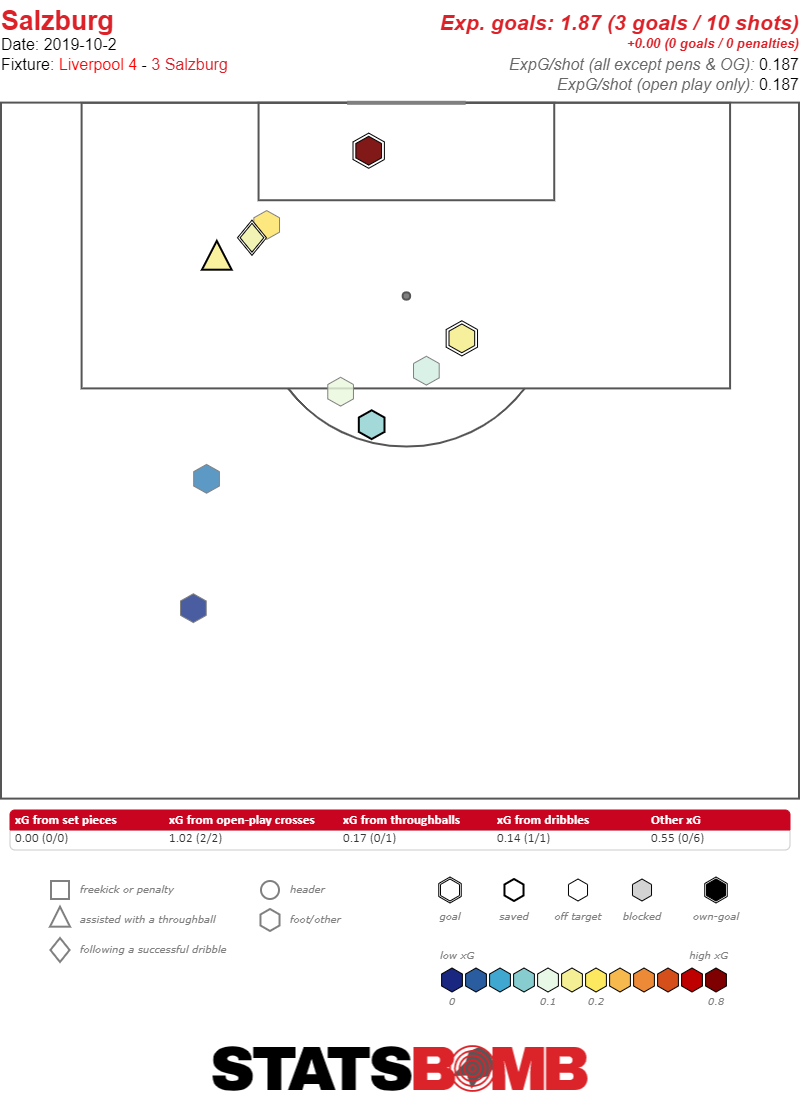

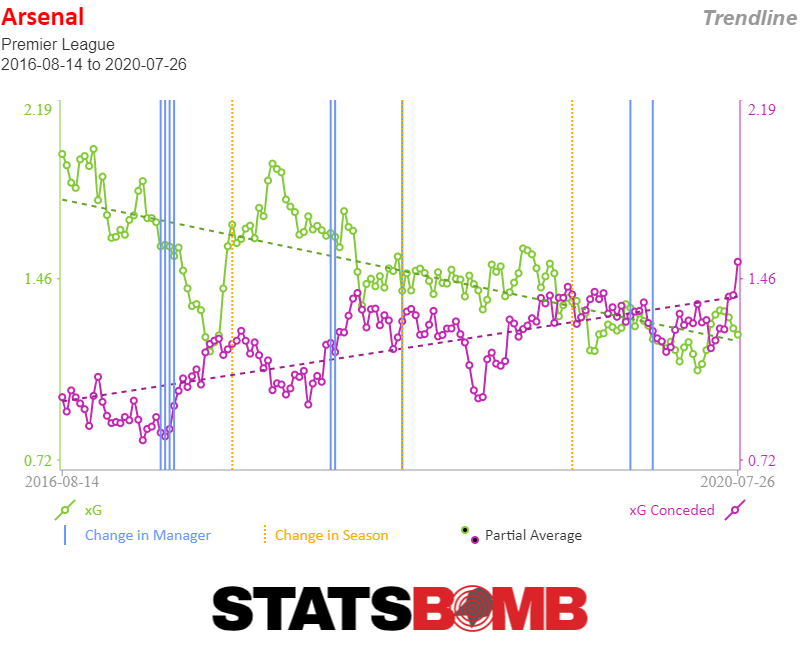

There’s an attacker in England who, after two seasons of utter dominance, has fallen down to Earth with good but not great production. His team’s record remains surprisingly strong, but underneath the hood, their expected goals record belies a team not actually at the station they expected to be, lucky to be above their rivals in the table. I’m talking, of course, about Mo Salah and Liverpool. It’s hard to complain about a team that has taken 21 of 21 points in the league and a guy who has three non-penalty goals and three assists in seven league matches, but the statistical record is flashing some warning signs. In 2017-2018, Salah came into the Premier League and set the world on fire. He took four shots per game, and racked up buckets of high quality chances, dribbling past would be defenders with aplomb, leaving them on the ground, and firing shots from the center of the box. His 0.6 expected goals per 90 minutes and 0.2 open play expected goals assisted per 90 led him to a Premier League Player of the Year. Last season, he came back to earth but was still excellent, with 0.4 xG per 90 and 0.22 open play xG assisted per 90. This season though? Through seven league matches Salah has just 0.37 xG per 90 and 0.05 xG assisted per 90. He’s still getting tons of touches in the box, more than last year in fact. But Salah is completing just 30% of his passes in the box or into the box to teammates, as compared to almost 50% last year. He’s also taken just a single shot with his feet within nine yards of goal this season. He had 29 such shots over the past two seasons combined. Perhaps that will change, but he does look somewhat less explosive than he did the last couple years, not turning the corner in the box with the same gusto. Two seasons of 4500 minutes plus playing in international tournaments may be taking its toll. Interestingly, the attack remains near last year's heights. Roberto Firmino and Sadio Mane have been excellent. While the team is not creating from open play like it did two seasons ago, they are finding more goals from set pieces. With the team treading water offensively, Liverpool’s xGD is a far cry from the heights of last season, and quite frankly, the second half of last season is a far cry from the first half:  As we saw against Salzburg, it is the defense that is struggling in particular, shipping significantly more high quality chances than it did last season.

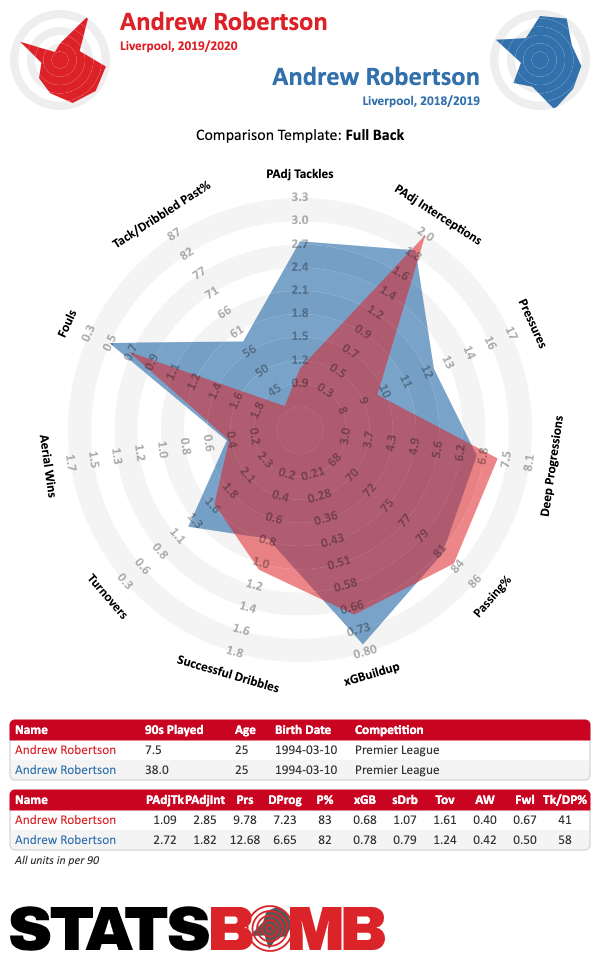

As we saw against Salzburg, it is the defense that is struggling in particular, shipping significantly more high quality chances than it did last season.  Perhaps the defense is struggling because the defenders are being asked to do too much in attack. Klopp played Andrew Robertson over 4500 minutes last season, rarely rotating his hyper-athletic left back who also was one of the team’s major creative engines. The wear on Robertson appears to be showing, with Robbo getting beaten much more consistently this season.

Perhaps the defense is struggling because the defenders are being asked to do too much in attack. Klopp played Andrew Robertson over 4500 minutes last season, rarely rotating his hyper-athletic left back who also was one of the team’s major creative engines. The wear on Robertson appears to be showing, with Robbo getting beaten much more consistently this season.  Trent Alexander-Arnold who also played a huge number of minutes at such a demanding position is also struggling to meet last year’s heights and is also one of Liverpool’s key creators. Last season and this season Liverpool got much of its creative output from its two fullbacks, but have perhaps ramped up their intensity even higher as a result of the midfield’s lack of ball progression. Alexander-Arnold and Robertson are combining for over 5.5 touches in the box so far this season, up significantly from about 4 combined last season. Robertson has even more deep progressions this year than last, one of his few increases in output. Robertson’s charging run into the box for a goal against Salzburg was a wonderful piece of skill, but also perhaps indicative of a team that has turned to its fullbacks to do too much, especially given that in the same move he was the player to advance the ball into the opposition half from his own defensive zone. Even so, last year Liverpool asked a lot of its fullbacks and were rock solid defensively. Teams do seem to be exploiting the space left by Alexander-Arnold more ruthlessly. The number of successful passes into areas he nominally would be controlling have increased significantly on a per 90 basis this season. But perhaps the other major change has been the loss of Alisson to start the season. Alisson is significantly more aggressive off his line than Adrian.

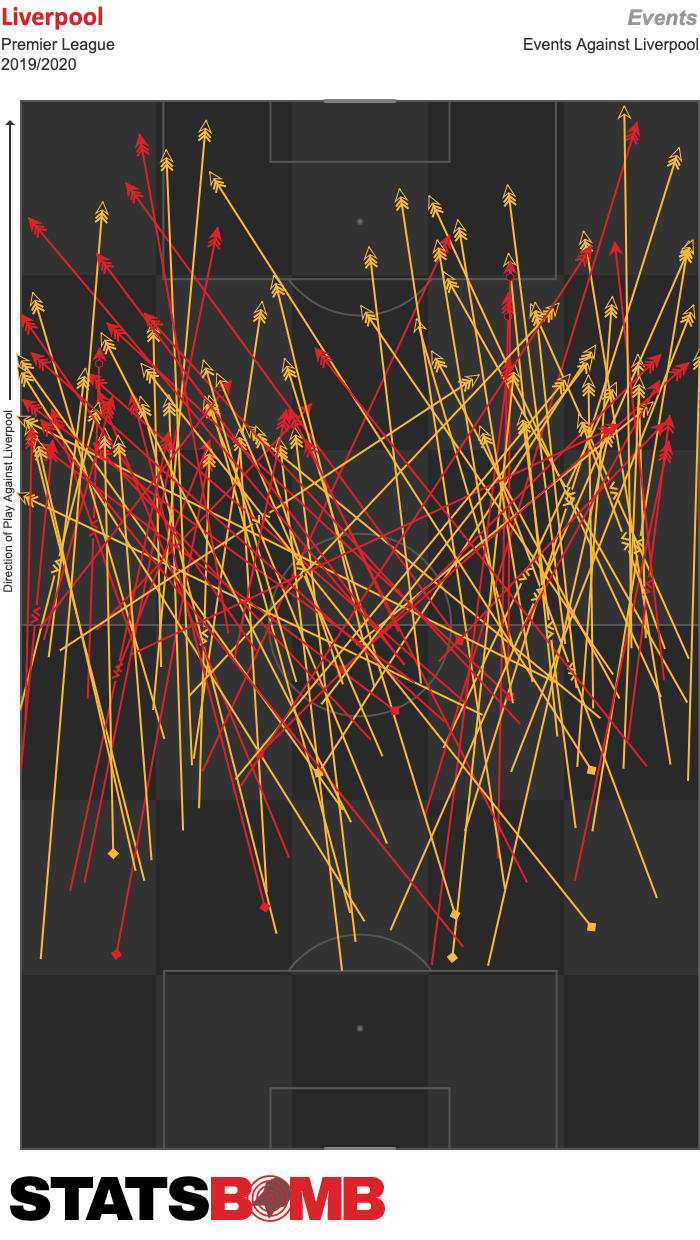

Trent Alexander-Arnold who also played a huge number of minutes at such a demanding position is also struggling to meet last year’s heights and is also one of Liverpool’s key creators. Last season and this season Liverpool got much of its creative output from its two fullbacks, but have perhaps ramped up their intensity even higher as a result of the midfield’s lack of ball progression. Alexander-Arnold and Robertson are combining for over 5.5 touches in the box so far this season, up significantly from about 4 combined last season. Robertson has even more deep progressions this year than last, one of his few increases in output. Robertson’s charging run into the box for a goal against Salzburg was a wonderful piece of skill, but also perhaps indicative of a team that has turned to its fullbacks to do too much, especially given that in the same move he was the player to advance the ball into the opposition half from his own defensive zone. Even so, last year Liverpool asked a lot of its fullbacks and were rock solid defensively. Teams do seem to be exploiting the space left by Alexander-Arnold more ruthlessly. The number of successful passes into areas he nominally would be controlling have increased significantly on a per 90 basis this season. But perhaps the other major change has been the loss of Alisson to start the season. Alisson is significantly more aggressive off his line than Adrian.  While Virgil Van Dijk can do almost everything, perhaps he cannot cover for two fullbacks and a less aggressive keeper. Looking at the radars of the two keepers, you can see that Alisson’s “GK Aggressive Distance” - where he makes tackles, interceptions, etc. - is much farther off the line than Adrian, who has otherwise filled in quite admirably. Liverpool’s high line, and very high fullbacks, have survived because Van Dijk is so good at filling in space, but also because their goalkeeper was perhaps also good at protecting the team from dangerous long balls into space. Using Statsbomb’s IQ tactics we can look at how well teams are completing passes against Liverpool that start from above the box in their own half and go into the final third. Last season teams completed 29% of such passes and completed 4.6 such passes per match. So far those numbers are 39% and 6.3.

While Virgil Van Dijk can do almost everything, perhaps he cannot cover for two fullbacks and a less aggressive keeper. Looking at the radars of the two keepers, you can see that Alisson’s “GK Aggressive Distance” - where he makes tackles, interceptions, etc. - is much farther off the line than Adrian, who has otherwise filled in quite admirably. Liverpool’s high line, and very high fullbacks, have survived because Van Dijk is so good at filling in space, but also because their goalkeeper was perhaps also good at protecting the team from dangerous long balls into space. Using Statsbomb’s IQ tactics we can look at how well teams are completing passes against Liverpool that start from above the box in their own half and go into the final third. Last season teams completed 29% of such passes and completed 4.6 such passes per match. So far those numbers are 39% and 6.3.  Simpler explanations for Liverpool’s statistical (though otherwise non-existent) struggles may also suffice. Seven matches is a small sample size. Virgil Van Dijk could have experienced a career year at 27 and still be great, just not superhuman this season. Of course, Liverpool may well start producing at last year’s levels again soon. Still, it’s important not to get fooled by the record and to see that maybe there are some cracks in what otherwise seems like an unstoppable juggernaut.

Simpler explanations for Liverpool’s statistical (though otherwise non-existent) struggles may also suffice. Seven matches is a small sample size. Virgil Van Dijk could have experienced a career year at 27 and still be great, just not superhuman this season. Of course, Liverpool may well start producing at last year’s levels again soon. Still, it’s important not to get fooled by the record and to see that maybe there are some cracks in what otherwise seems like an unstoppable juggernaut.

There are a lot of players in the Premier League. Generally speaking, to reach the top flight of English football, most of them are quite good. We're quite used to generalised qualities at this point. Fullbacks who can overlap, inverted wingers who can cut inside and shoot, defensive midfielders who can win the ball back aggressively. But there are some players who just do things differently to everyone else. This might not necessarily be a positive or negative thing, but here are six individuals who have statistically stood out as unusual so far this season.

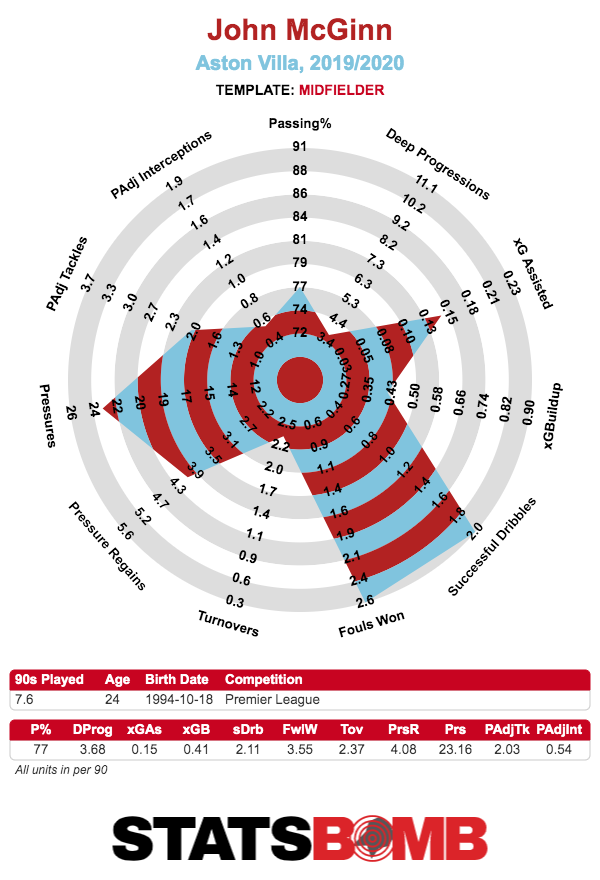

John McGinn

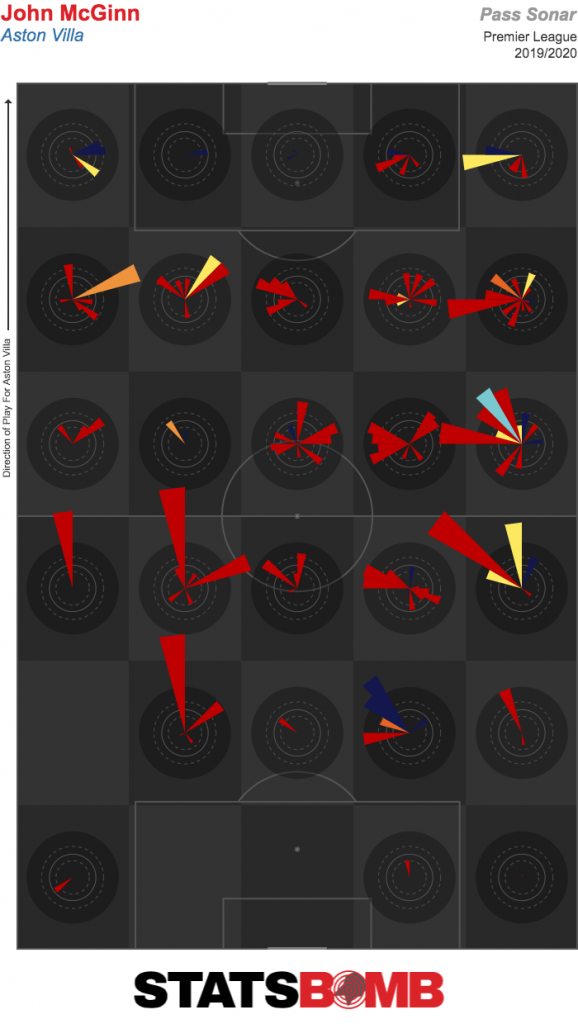

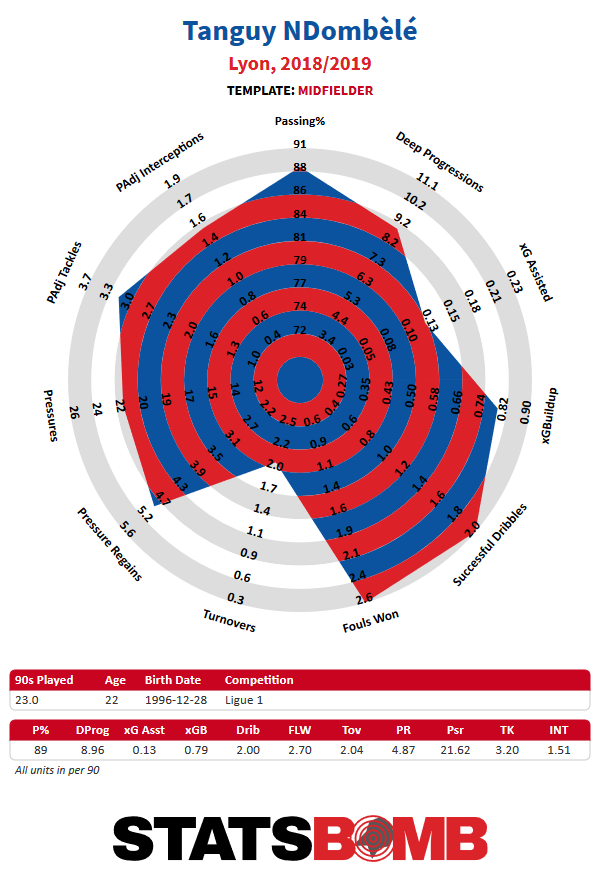

Of all the players to feature in central midfield this season, only three, Ross Barkley, Tanguy Ndombele and Kevin De Bruyne (interpreting “central midfield” loosely here), have made more successful dribbles per 90 than John McGinn. Only McGinn’s Villa teammate Jack Grealish has won more fouls per 90 than the Scotland international. So we know what it is that he does. But on the other side, no central midfielder is making fewer passes per 90 than McGinn. This is someone who seems to choose to dribble and thus draw fouls over passing the ball at every possible opportunity.  When McGinn does pass the ball, he isn’t shy about pinging it, with the seventh longest average pass length of any central midfielder. It’s clear in his sonar just how direct he’s willing to go.

When McGinn does pass the ball, he isn’t shy about pinging it, with the seventh longest average pass length of any central midfielder. It’s clear in his sonar just how direct he’s willing to go.  Or alternatively, he’ll carry it, with the third longest carry length in the position. He’ll do anything except the obvious option of keeping it simple and making a pass. This might be because he’s playing with Grealish, natural playmaker extraordinaire. It could simply be that it’s just his natural game. His application and desire to run is the kind of thing that catches the eye of fans, especially in the UK, and it’s hard to argue he’s not a useful player for Villa. He does have this very obvious, somewhat bizarre limit, and Dean Smith needs to construct his side accordingly for it. Unfortunately for McGinn, one would imagine these limitations make the bottom half of the Premier League his ceiling, with a better side that dominates possession unlikely to want to have to tweak the midfield balance to fit him in. For now, though, Villa fans should enjoy the things he does and worry not about his lack of passing.

Or alternatively, he’ll carry it, with the third longest carry length in the position. He’ll do anything except the obvious option of keeping it simple and making a pass. This might be because he’s playing with Grealish, natural playmaker extraordinaire. It could simply be that it’s just his natural game. His application and desire to run is the kind of thing that catches the eye of fans, especially in the UK, and it’s hard to argue he’s not a useful player for Villa. He does have this very obvious, somewhat bizarre limit, and Dean Smith needs to construct his side accordingly for it. Unfortunately for McGinn, one would imagine these limitations make the bottom half of the Premier League his ceiling, with a better side that dominates possession unlikely to want to have to tweak the midfield balance to fit him in. For now, though, Villa fans should enjoy the things he does and worry not about his lack of passing.

Ryan Fredericks

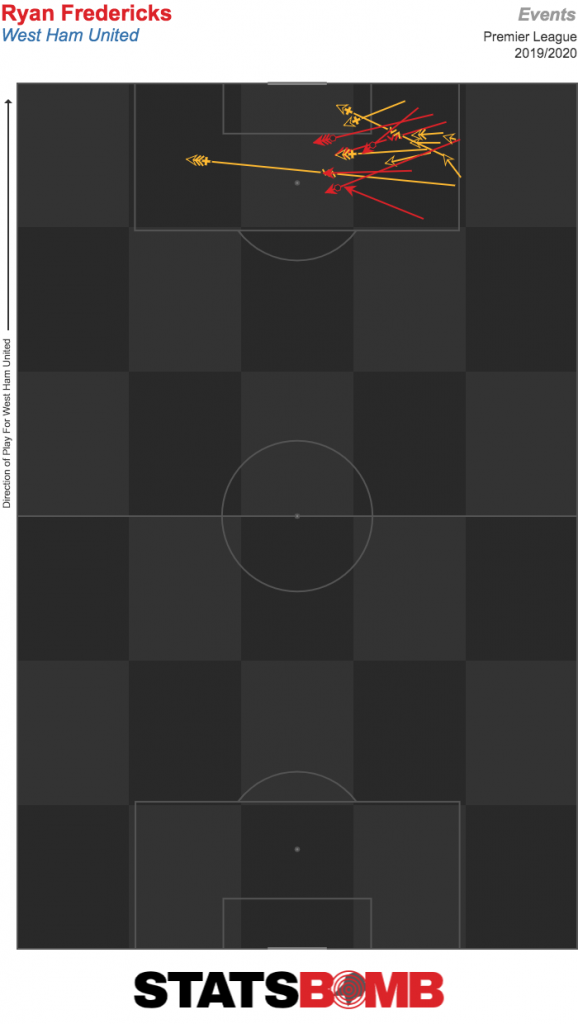

Mohamed Salah has attempted 18 passes inside the box so far this season. That’s the most of any player in the division. Wilfried Zaha and Jamie Vardy are next up with 17 and 13 each. If I told you the next player was a fullback, you might think of Liverpool’s pair of Andy Robertson and Trent Alexander-Arnold, or possibly someone like Oleksandr Zinchenko. You probably wouldn’t expect it to be someone who featured so irregularly for West Ham last season.  Ryan Fredericks looks a fairly average right back by most other measures. He’s not a hugely active defender, and he’s not progressing the ball up the pitch that well until it gets into the box. The player this is somewhat reminiscent of is Sead Kolasinac. Last season, Kolasinac consistently put up incredible creative numbers by getting forward and delivering cut backs to Arsenal’s talented attack. Fredericks isn’t creating at such a rate yet, but the potential seems to be there. Of course, the other side of Kolasinac was his inability to cover such ground that he could provide a threat in the final third without leaving his side horribly exposed. That Arsenal felt the need to buy Kieran Tierney shows just how little Kolasinac’s unusual skills were seen as helpful in the end. Fredericks may have the advantage here of being a much better athlete. He has the speed to cover much more ground than Kolasinac, to get into the box and still potentially recover defensively if the Hammers get caught out. We’re dealing with a small sample size here, and this is something that could easily drift away as the season goes on, especially if Manuel Pellegrini wants to tighten things up at the back. But Fredericks might have the toolkit to be a very interesting, very adventurous right back who can be an important cog in West Ham’s attack.

Ryan Fredericks looks a fairly average right back by most other measures. He’s not a hugely active defender, and he’s not progressing the ball up the pitch that well until it gets into the box. The player this is somewhat reminiscent of is Sead Kolasinac. Last season, Kolasinac consistently put up incredible creative numbers by getting forward and delivering cut backs to Arsenal’s talented attack. Fredericks isn’t creating at such a rate yet, but the potential seems to be there. Of course, the other side of Kolasinac was his inability to cover such ground that he could provide a threat in the final third without leaving his side horribly exposed. That Arsenal felt the need to buy Kieran Tierney shows just how little Kolasinac’s unusual skills were seen as helpful in the end. Fredericks may have the advantage here of being a much better athlete. He has the speed to cover much more ground than Kolasinac, to get into the box and still potentially recover defensively if the Hammers get caught out. We’re dealing with a small sample size here, and this is something that could easily drift away as the season goes on, especially if Manuel Pellegrini wants to tighten things up at the back. But Fredericks might have the toolkit to be a very interesting, very adventurous right back who can be an important cog in West Ham’s attack.

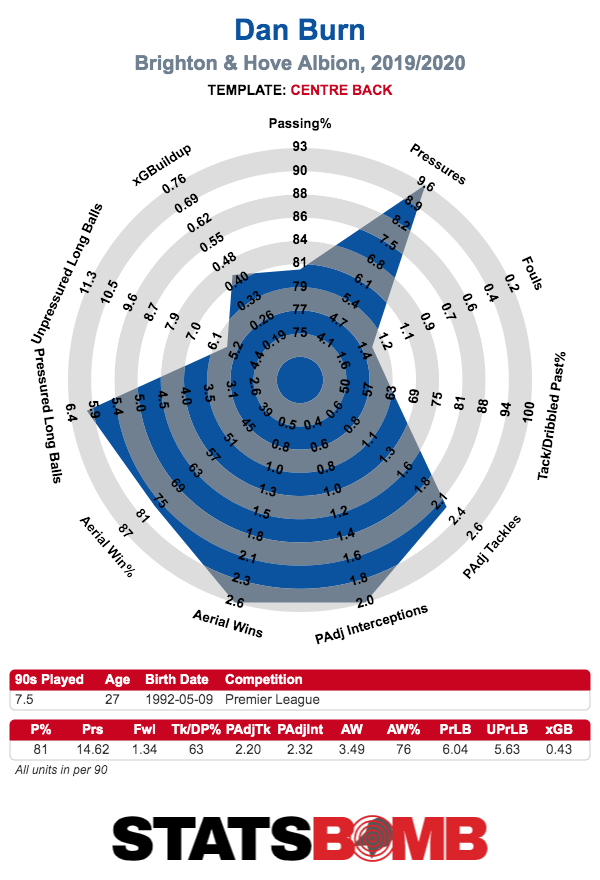

Dan Burn

When Graham Potter arrived at Brighton, the expectation was that he would change the style of football. The attacking emphasis would be greater, he’d move to a system with three at the back, and defenders previously accustomed to hoofing it would be asked to play more football. The assumption was that new signing Adam Webster, a centre back extremely comfortable taking risks, would be the poster boy for this shift. It was not expected that Potter would make Dan Burn the key player in his new defensive system.  If you’re moving to a back three, having a left footed defender like Burn is always a bonus, especially when he even played occasional left back minutes at Wigan. What we’re seeing so far from Burn is someone extremely comfortable moving forward. While we’re dealing with small sample sizes here, no other centre back in the league gets close to his 0.8 open play passes into the box per 90. Similarly, he leads the division’s centre backs in open play passes in the final third per 90. And it doesn’t stop with his passing range, also posting the most frequent attempted dribbles, though with fully half of them not coming off, he should probably slow down on that front. The wide centre back roles in a back three can often be slightly strange hybrid positions, neither centre back nor full back. Perhaps unexpectedly, Burn is interpreting the role in a particularly expansive manner.

If you’re moving to a back three, having a left footed defender like Burn is always a bonus, especially when he even played occasional left back minutes at Wigan. What we’re seeing so far from Burn is someone extremely comfortable moving forward. While we’re dealing with small sample sizes here, no other centre back in the league gets close to his 0.8 open play passes into the box per 90. Similarly, he leads the division’s centre backs in open play passes in the final third per 90. And it doesn’t stop with his passing range, also posting the most frequent attempted dribbles, though with fully half of them not coming off, he should probably slow down on that front. The wide centre back roles in a back three can often be slightly strange hybrid positions, neither centre back nor full back. Perhaps unexpectedly, Burn is interpreting the role in a particularly expansive manner.

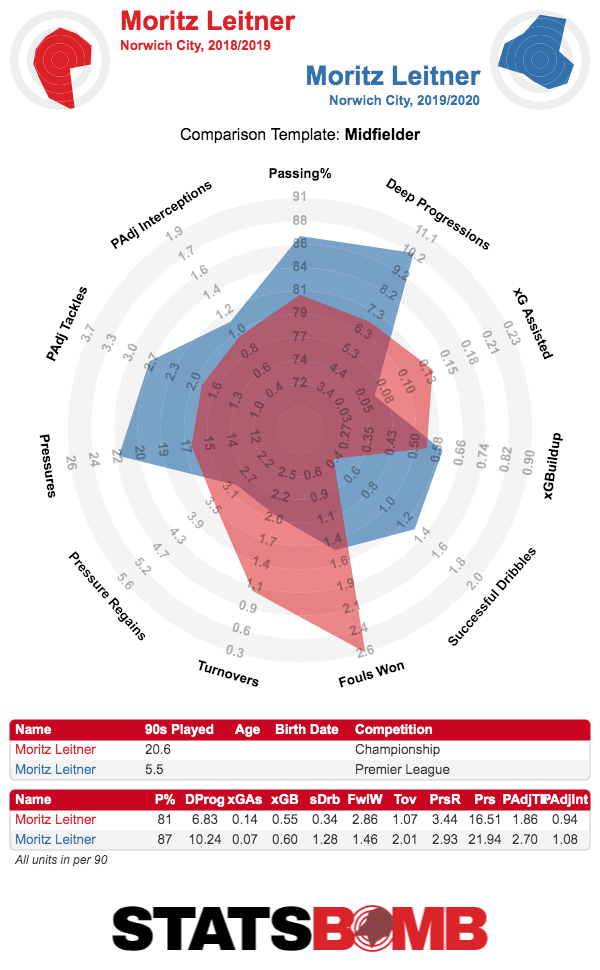

Moritz Leitner

So you’re a promoted side that decides to stick with your progressive brand of football in the Premier League. You’ve also decided to keep the budget down and avoid splashing out on expensive signings. What you need is one of your central midfielders to really step up and progress the ball at an even better rate than last season, while at the same time working harder defensively than before.  After failing to make the grade at Borussia Dortmund before bouncing around Stuttgart, Lazio and Augsburg, Moritz Leitner has become the hard working creative central midfielder that makes Norwich tick. In the entire league, only Harry Winks is putting up more deep progressions per 90 than the German. Aymeric Laporte and Robertson are the only players with more carries per 90 than Leitner. And even after the ball is worked into the final third, he’s still among the top 20 players for passes within that zone. For a team with only 50% possession. Norwich are more an interesting team this season than they are good, with the side needing to hope their fourth worst expected goal difference in the league will be enough to see them right. When they work the ball into dangerous areas, though, they’re a delight to watch, and Leitner is absolutely a key player in making those situations happen.

After failing to make the grade at Borussia Dortmund before bouncing around Stuttgart, Lazio and Augsburg, Moritz Leitner has become the hard working creative central midfielder that makes Norwich tick. In the entire league, only Harry Winks is putting up more deep progressions per 90 than the German. Aymeric Laporte and Robertson are the only players with more carries per 90 than Leitner. And even after the ball is worked into the final third, he’s still among the top 20 players for passes within that zone. For a team with only 50% possession. Norwich are more an interesting team this season than they are good, with the side needing to hope their fourth worst expected goal difference in the league will be enough to see them right. When they work the ball into dangerous areas, though, they’re a delight to watch, and Leitner is absolutely a key player in making those situations happen.

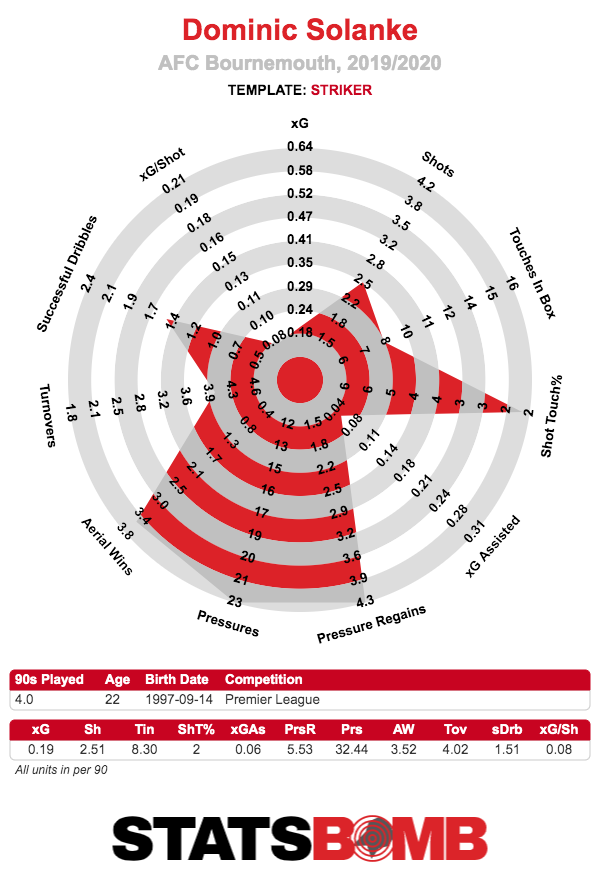

Dominic Solanke

Let’s not beat around the bush here: Dominic Solanke has been bad at scoring goals. And this isn’t even a situation similar to his time at Liverpool where he just wasn’t finishing good chances. His 0.19 xG per 90 is nothing other than poor, especially compared to what his teammate Callum Wilson is doing. But that’s not the end of the story for Solanke. Only two players in the Premier League are managing more pressures per 90 than the Bournemouth man. What’s more, no striker (if we discount Wilfried Zaha and Gerard Deulofeu on the grounds that they are not really strikers) is making more deep progressions per 90 than Solanke. He’s working hard for the team by closing down opponents, then receiving the ball in deep areas to progress it forward. While playing as a striker.  Does it matter that he’s not scoring more? In terms of public perception it seems to. Solanke will be “shit until he scores loads” in the court of public opinion. But in terms of Bournemouth’s system, it’s not obvious that this is a problem. Playing in a front two with Wilson, the more important role is to ensure that the strikers do not become isolated or the midfield gets exposed. Solanke is ideal for this, and should be able to do the role at a higher level than Joshua King.

Does it matter that he’s not scoring more? In terms of public perception it seems to. Solanke will be “shit until he scores loads” in the court of public opinion. But in terms of Bournemouth’s system, it’s not obvious that this is a problem. Playing in a front two with Wilson, the more important role is to ensure that the strikers do not become isolated or the midfield gets exposed. Solanke is ideal for this, and should be able to do the role at a higher level than Joshua King.

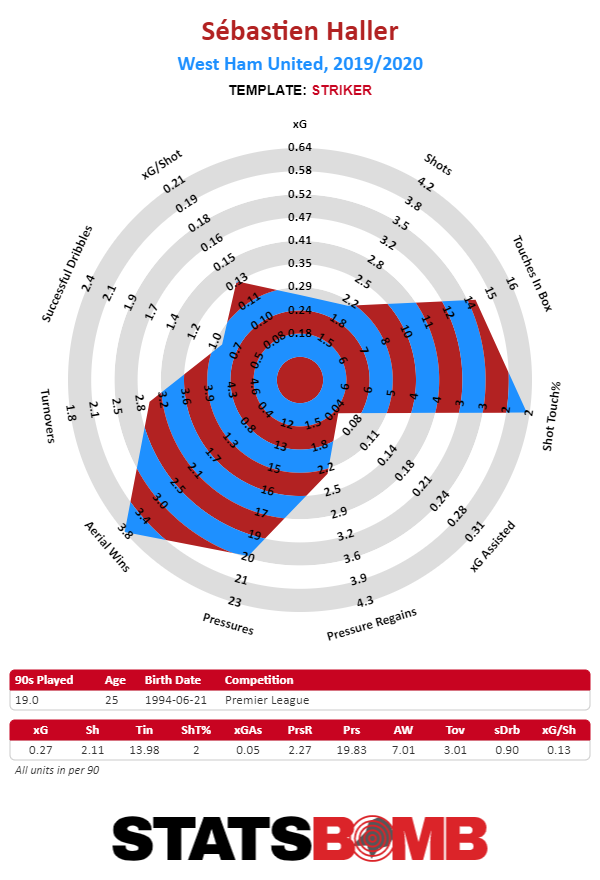

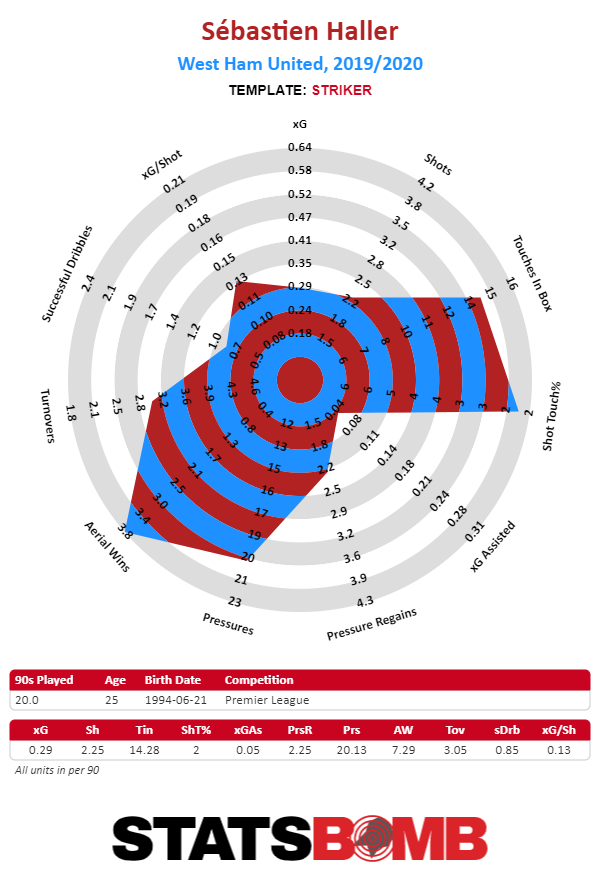

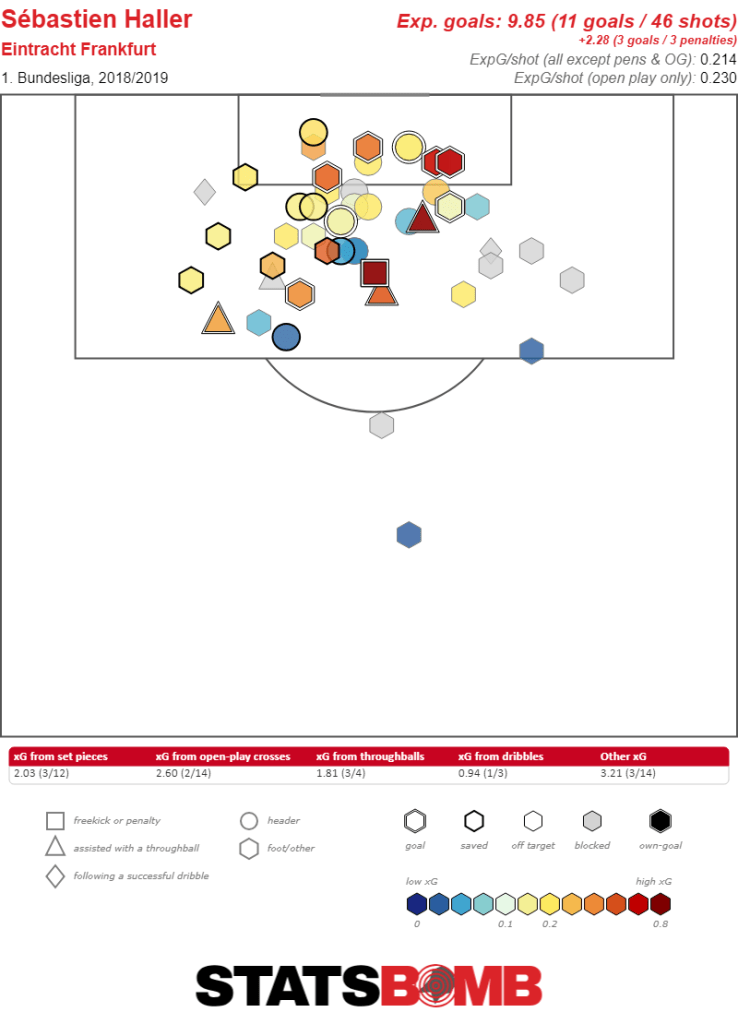

Sebastien Haller

Ok, but what if someone was doing a lot of the things Solanke offers, while also scoring goals? Meet Sebastien Haller.  No striker (again, discounting Deulofeu because he isn’t one) is making more open play passes per 90 than Haller. Only Solanke is putting up more deep progressions. He’s exerting a very respectable 20.11 pressures per 90. His shot volume is on the low side, but when he gets them, boy does he get some good ones.

No striker (again, discounting Deulofeu because he isn’t one) is making more open play passes per 90 than Haller. Only Solanke is putting up more deep progressions. He’s exerting a very respectable 20.11 pressures per 90. His shot volume is on the low side, but when he gets them, boy does he get some good ones.  Haller combines the all round play of a striker who typically wouldn’t score a lot of goals with the shot profile of a pure poacher. It’s a fascinating package of skills and West Ham can consider themselves to have a real gem here.

Haller combines the all round play of a striker who typically wouldn’t score a lot of goals with the shot profile of a pure poacher. It’s a fascinating package of skills and West Ham can consider themselves to have a real gem here.

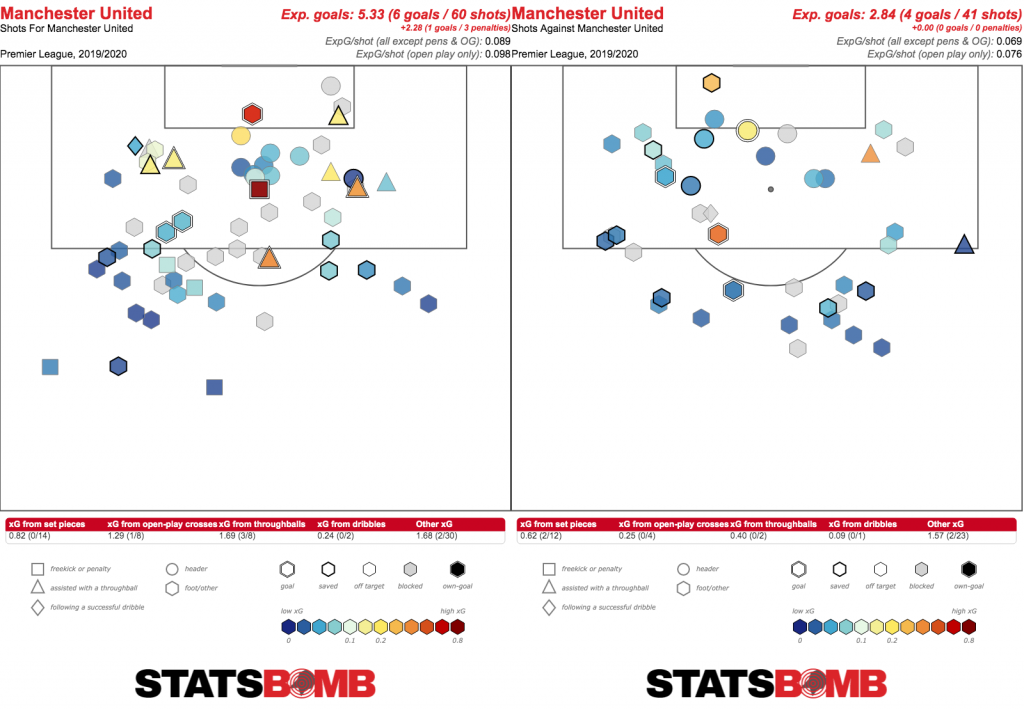

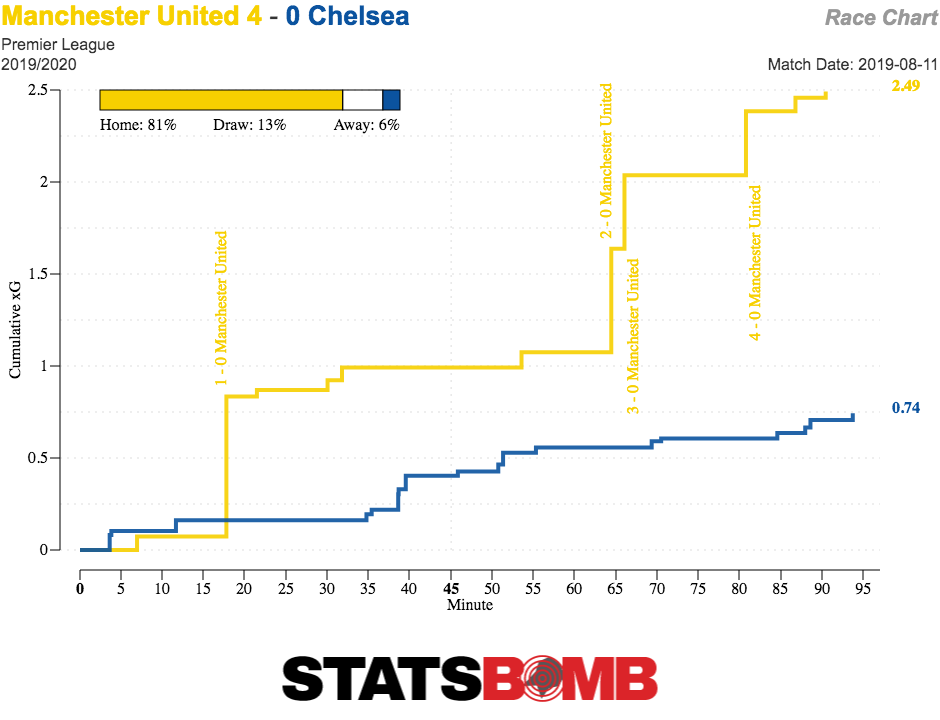

As always, it’s complicated. Any traditional results based analysis will tell you that Manchester United have started the Premier League season very poorly. Five points from four games is never a great haul, and it goes down all the worse when it features underwhelming draws at Wolves and Southampton along with the cherry on the cake, a 2-1 defeat at home to Crystal Palace. Memories of a 4-0 win over Chelsea on the first weekend of the season have all but vanished. This side has just stunk, and there’s no putting a positive spin on it. Right? It didn’t go unnoticed that United’s expected goals haven’t looked so bad, at least at first glance. This made some noises among some United-focused Twitter accounts, but really hit the stratosphere when Sam Carney of the official Manchester United website wrote an article on the subject. xG has made its way into a lot of mainstream publications in recent years to the delight of many, but something put out on the official site of one of the biggest clubs in the world might be a new pinnacle. In the article, Carney argues that “In each of our four matches so far, United have significantly outperformed our opponents in terms of xG”, eventually stating that “through a combination of bad luck and superb opposition goalkeeping – think Rui Patricio’s excellent save from Paul Pogba’s penalty in the Wolves game – our dominance hasn’t been reflected in the final scoreline. “But these numbers suggest to me that Ole [Gunnar Solskjaer] has [United] playing a positive brand of attacking football that should start to pay dividends sooner, rather than later”. To start with, yes, the numbers do look pretty solid. Not “we’re gonna win the league” good, but definitely decent, and nothing that would ring any alarm bells if Paul Pogba and Marcus Rashford score a few penalties and David De Gea makes a couple of big saves.  Since we’re only four games into the season, making definitive claims from the numbers is hard. So let’s look a little closer at each of these fixtures and see what actually happened here.

Since we’re only four games into the season, making definitive claims from the numbers is hard. So let’s look a little closer at each of these fixtures and see what actually happened here.

One Game at a Time

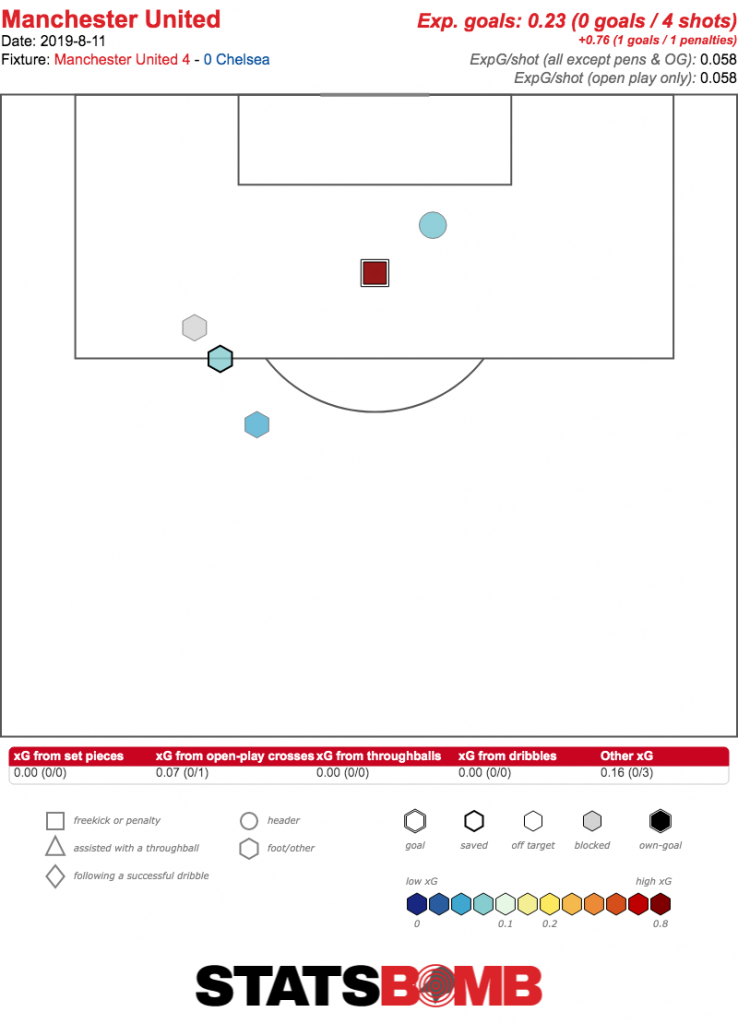

Game one was the actual win, a very pleasing 4-0 scoreline against Chelsea.  It’s worth mentioning here that United were only a penalty better than Chelsea in the first half. Including penalties in xG models is always questionable, and if predicting future performance is what you’re aiming to do, the prevailing consensus is generally to exclude them. That way, you’re left with four shots in 45 minutes, none of them decent chances.

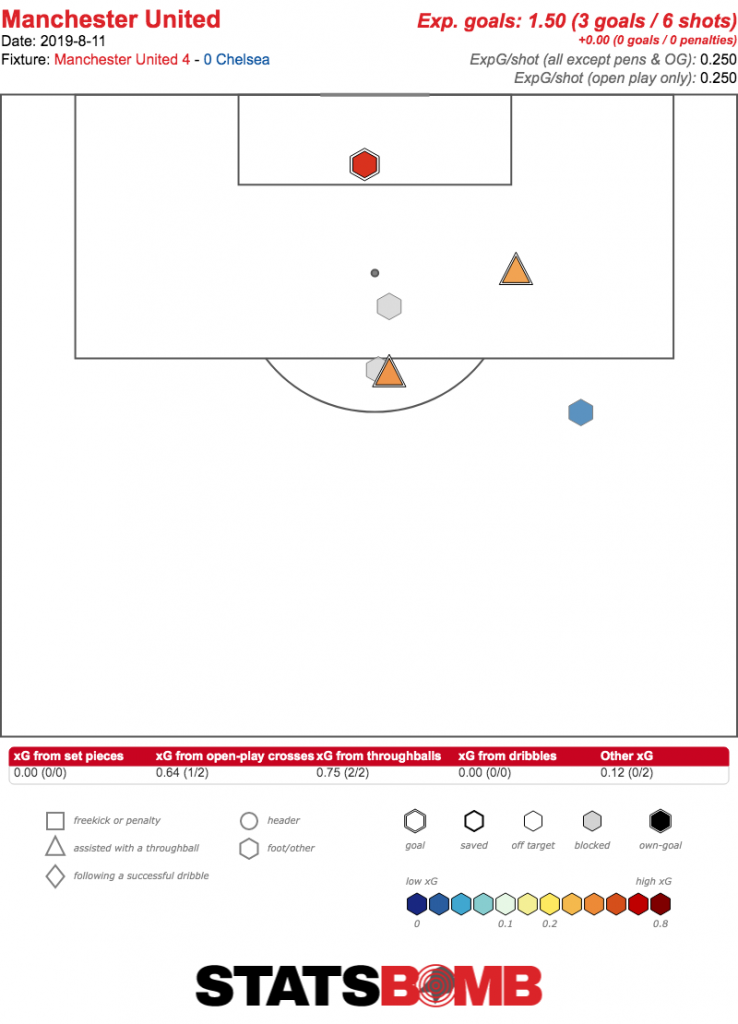

It’s worth mentioning here that United were only a penalty better than Chelsea in the first half. Including penalties in xG models is always questionable, and if predicting future performance is what you’re aiming to do, the prevailing consensus is generally to exclude them. That way, you’re left with four shots in 45 minutes, none of them decent chances.  But ahead they were, and it allowed them to play on the break in the second half. With Chelsea’s poor defensive organisation, United created three very good chances on the counter, and scored them all.

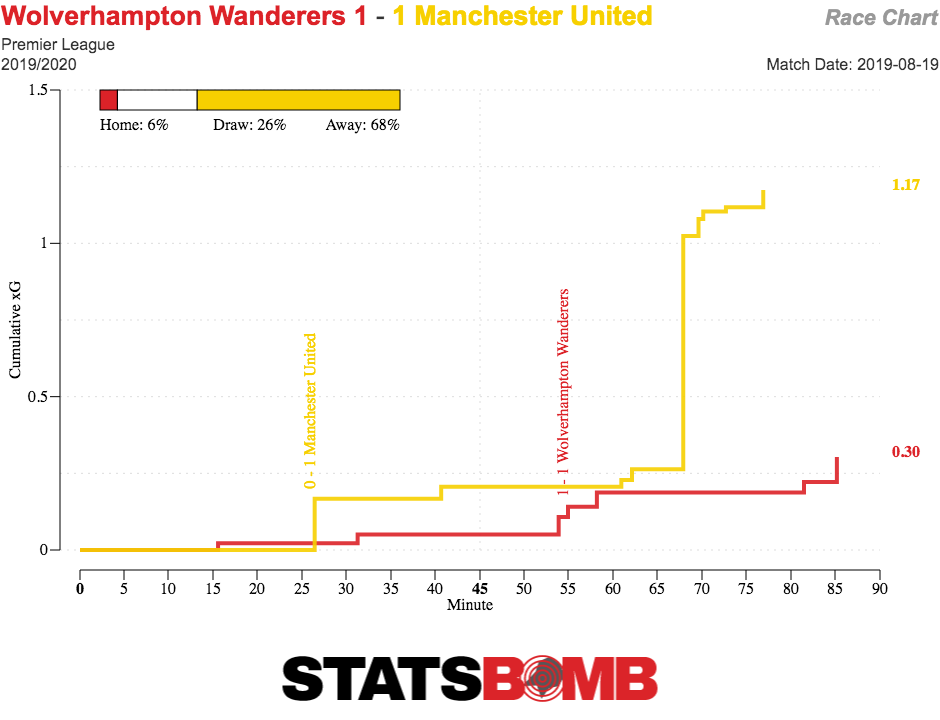

But ahead they were, and it allowed them to play on the break in the second half. With Chelsea’s poor defensive organisation, United created three very good chances on the counter, and scored them all.  Onto the game at Wolves and where the supposed troubles started. The home side, as they often do, played very conservatively and looked to create on the counter, but it’s a credit to United that they really struggled with this, producing just five shots of which none were more than half-chances.

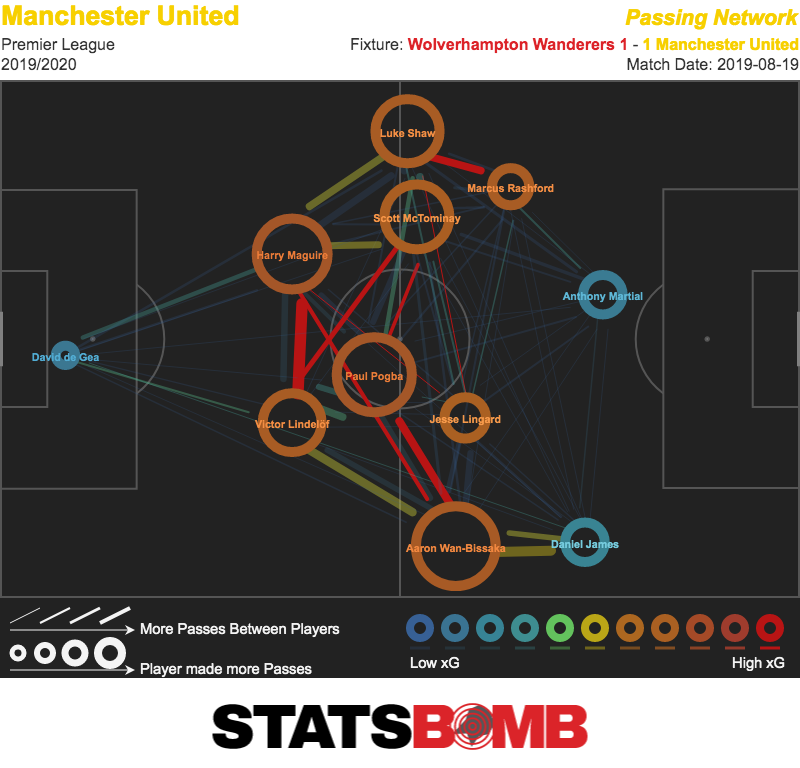

Onto the game at Wolves and where the supposed troubles started. The home side, as they often do, played very conservatively and looked to create on the counter, but it’s a credit to United that they really struggled with this, producing just five shots of which none were more than half-chances.  In his Premier League career so far, Ruben Neves has taken 67 shots that were not penalties or direct free kicks. All were from outside the box. Exactly one of them went in the goal, and it came in this match. It’s hard not to chalk that up to a case of shit happens. Solskjaer’s side shut down Wolves’ counter attacks, but seemed pretty toothless in creating chances themselves. The very mobile front four of Daniel James, Jesse Lingard, Marcus Rashford and Anthony Martial didn’t seem to have any way of breaking down a deep defence, and registered just 8 shots outside of the now infamous missed penalty, and 0.41 expected goals. The passmap sums up United’s issues: lots of dominance and interplay with the back four and midfielders, but a struggle to get the attackers involved in dangerous areas.

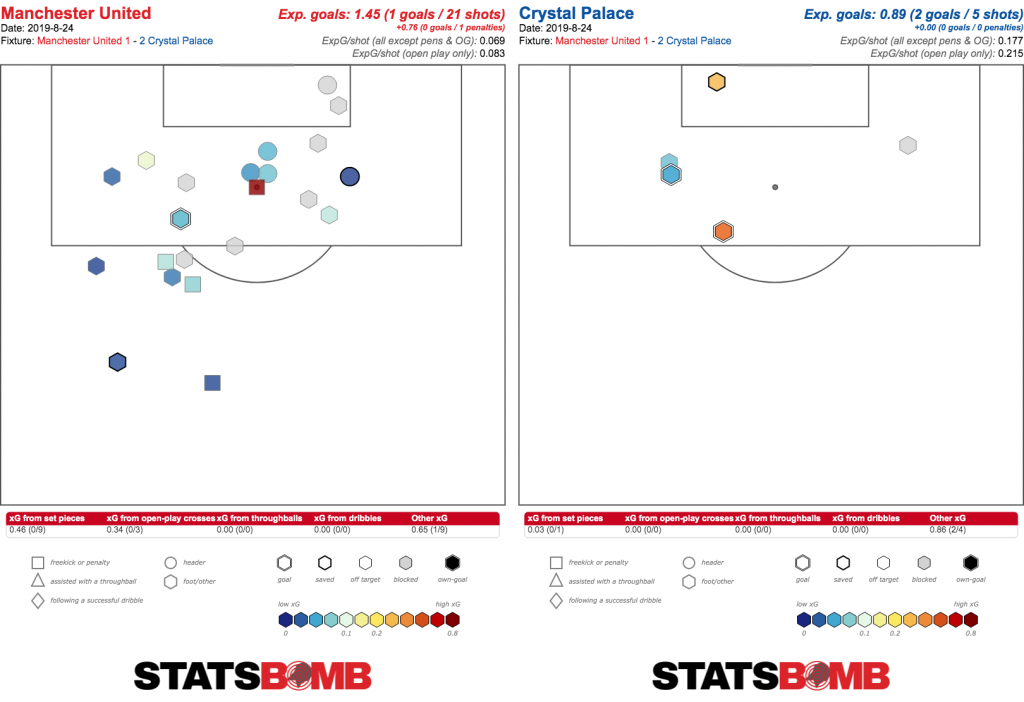

In his Premier League career so far, Ruben Neves has taken 67 shots that were not penalties or direct free kicks. All were from outside the box. Exactly one of them went in the goal, and it came in this match. It’s hard not to chalk that up to a case of shit happens. Solskjaer’s side shut down Wolves’ counter attacks, but seemed pretty toothless in creating chances themselves. The very mobile front four of Daniel James, Jesse Lingard, Marcus Rashford and Anthony Martial didn’t seem to have any way of breaking down a deep defence, and registered just 8 shots outside of the now infamous missed penalty, and 0.41 expected goals. The passmap sums up United’s issues: lots of dominance and interplay with the back four and midfielders, but a struggle to get the attackers involved in dangerous areas.  Crystal Palace also defended deep in the following game at Old Trafford, but United had at least a better go at breaking them down. They put up plenty of shots both before and after Jordan Ayew scored the game’s first goal. But, just as Roy Hodgson likely planned it, Palace’s deep block ensured that the chances were of poor quality, mostly being headers or shots with plenty of bodies in the way. Again, if United score the penalty they probably win the game, but you have to squint a bit to argue this was a good attacking performance. At the other end, Palace scored two goals from five shots and 0.89 xG, which doesn’t feel like too much of a serious concern for Solskjaer.

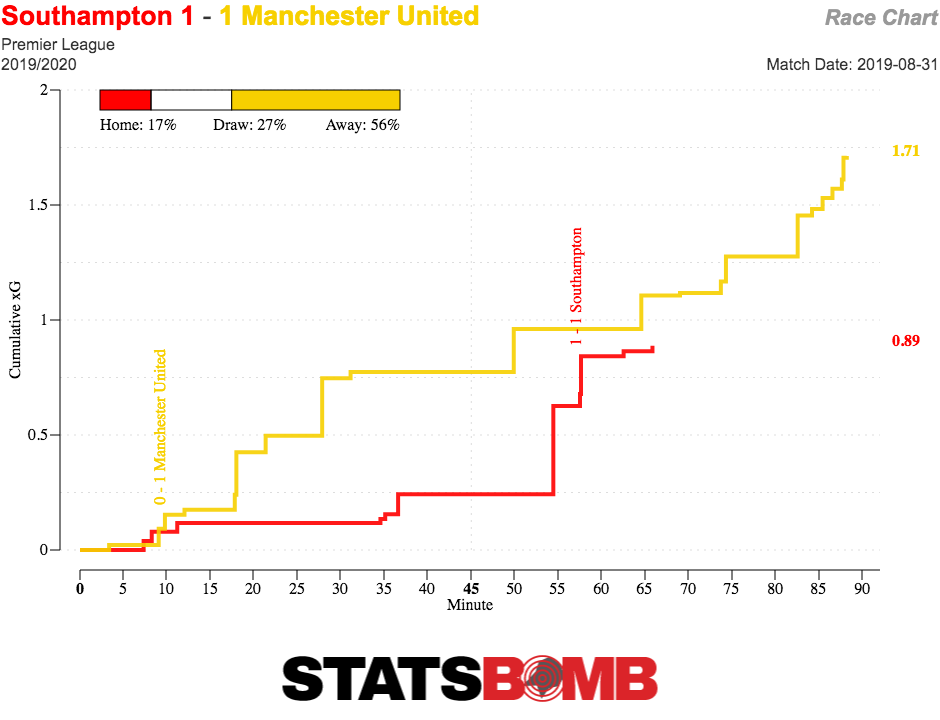

Crystal Palace also defended deep in the following game at Old Trafford, but United had at least a better go at breaking them down. They put up plenty of shots both before and after Jordan Ayew scored the game’s first goal. But, just as Roy Hodgson likely planned it, Palace’s deep block ensured that the chances were of poor quality, mostly being headers or shots with plenty of bodies in the way. Again, if United score the penalty they probably win the game, but you have to squint a bit to argue this was a good attacking performance. At the other end, Palace scored two goals from five shots and 0.89 xG, which doesn’t feel like too much of a serious concern for Solskjaer.  Southampton away was another fixture where United “deserved” to win on xG, but there were still real concerns to be had.

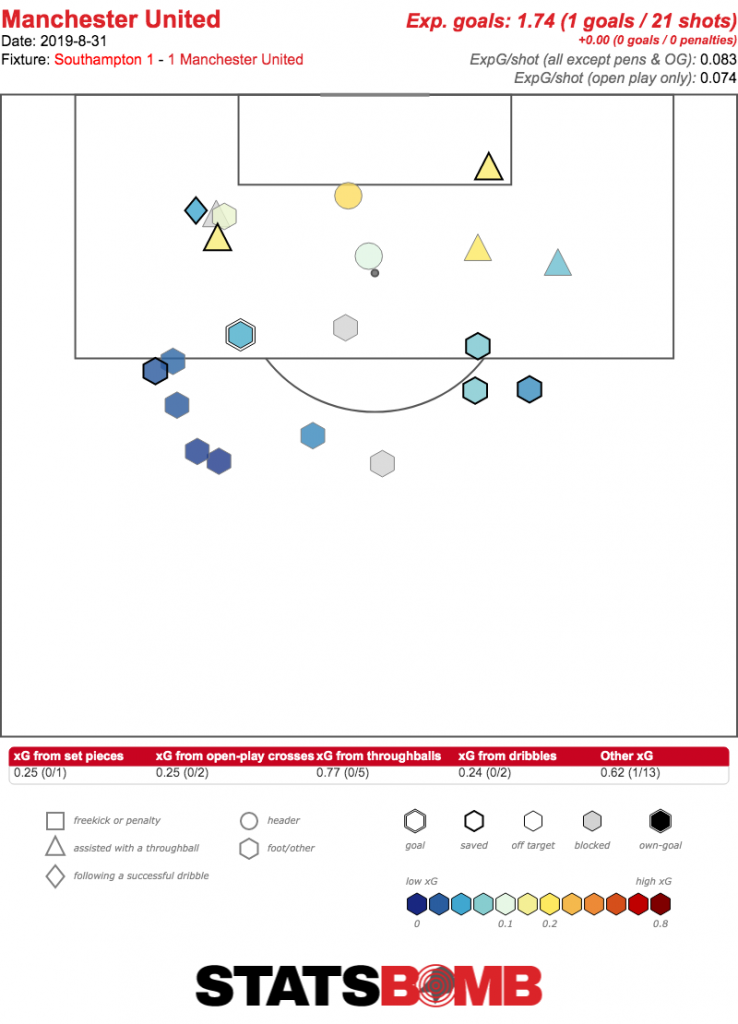

Southampton away was another fixture where United “deserved” to win on xG, but there were still real concerns to be had.  They again recorded plenty of shots, and again struggled in terms of the quality of those chances. Southampton defend in a slightly different way to Wolves and Palace, but the effect was the same. This was a better attacking performance than in those games, but also one in which they were facing ten men for the closing stages. If United can’t create high xG shots then, when will they?

They again recorded plenty of shots, and again struggled in terms of the quality of those chances. Southampton defend in a slightly different way to Wolves and Palace, but the effect was the same. This was a better attacking performance than in those games, but also one in which they were facing ten men for the closing stages. If United can’t create high xG shots then, when will they?

The Bigger Picture

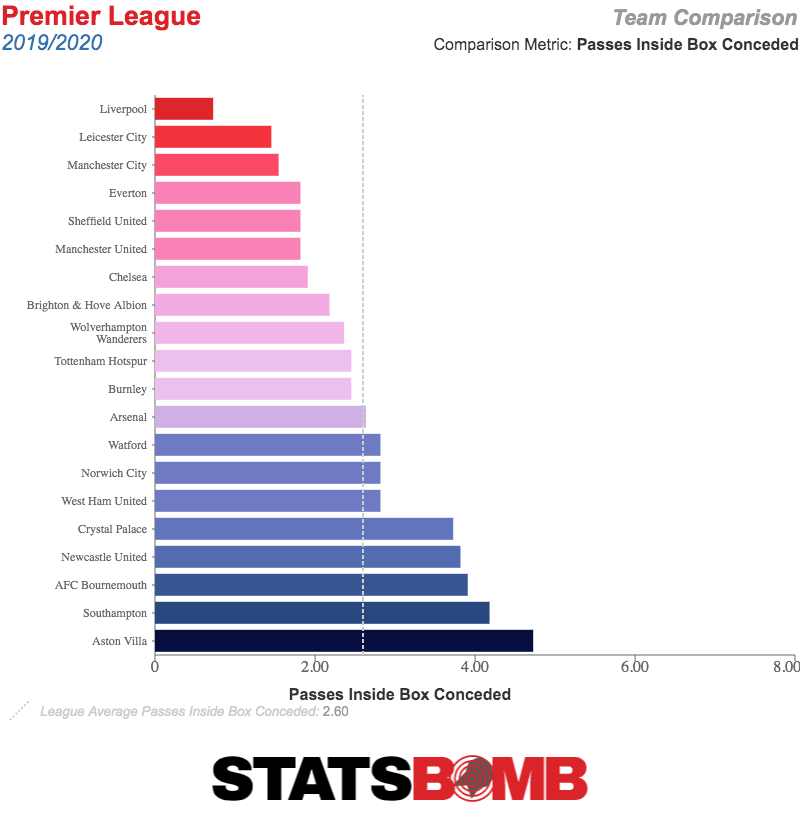

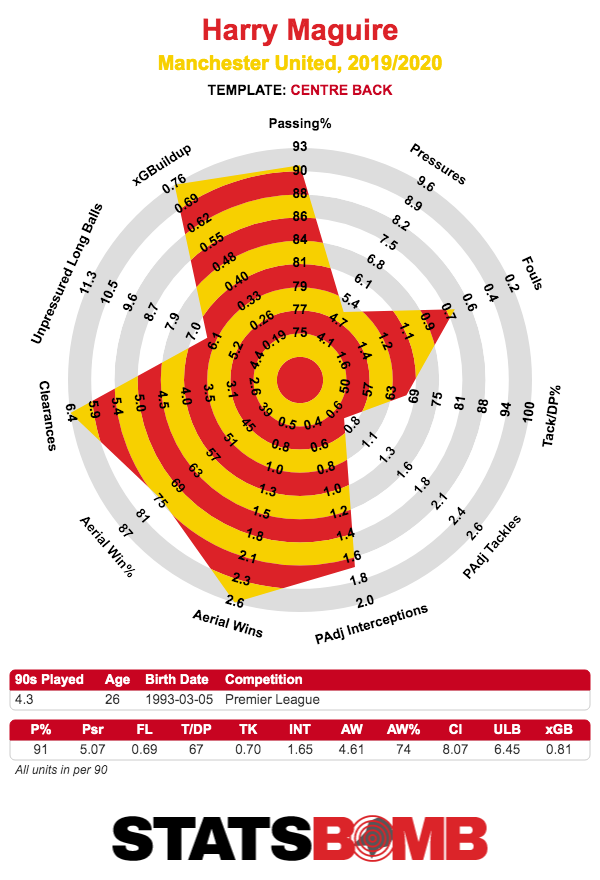

Expected goals says that Man United have been excellent at preventing the opposition from creating chances. At the other end, there’s an unusually large difference in whether the model includes penalties or not. It’s unusual to miss two of three penalties, but it’s also unusual to win three penalties in four games. Otherwise, xG says that United have been fairly middling at creating good chances so far. That the defence has been legitimately excellent does come as something of a surprise. And it’s not just xG that says so. Solskjaer’s team are restricting opposing sides to just three passes in United’s box, the second fewest in the league. Teams have found it very difficult simply to work the ball into dangerous areas.  Should this be a surprise? The club did, after all, spend huge sums on Harry Maguire and Aaron Wan-Bissaka to upgrade the back line. If these players are worth the money, they presumably should be having a noticeable effect on United’s defensive numbers. Judging centre backs statistically is an extremely difficult thing to do, so we’re not going to even attempt that here. What we can say is that he’s been unsurprisingly dominant with his head, amassing the most aerial wins of any player in the so called top six so far this season. It looks good, but again, don’t read too much into numbers for a centre back.

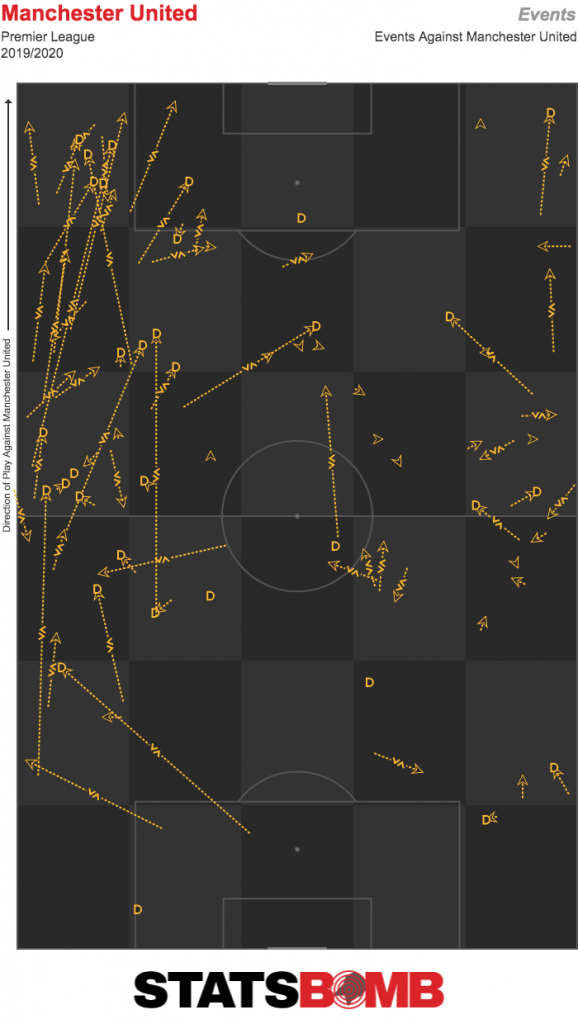

Should this be a surprise? The club did, after all, spend huge sums on Harry Maguire and Aaron Wan-Bissaka to upgrade the back line. If these players are worth the money, they presumably should be having a noticeable effect on United’s defensive numbers. Judging centre backs statistically is an extremely difficult thing to do, so we’re not going to even attempt that here. What we can say is that he’s been unsurprisingly dominant with his head, amassing the most aerial wins of any player in the so called top six so far this season. It looks good, but again, don’t read too much into numbers for a centre back.  As for Wan-Bissaka, he’s won plaudits for his volume of tackles so far, but that’s not the real story. Defending is not about what you do, but what you stop your opponent from doing. Palace fans had a delightful song about Wan-Bissaka to the tune of “Rock the Casbah” with the line “your wingers don’t like him”, and that sums up what his game is about perfectly. At his best, he doesn’t let players he’s directly up against get past him. Can we find evidence for this in the numbers? Well here’s what there is. When looking at failed attempts to dribble or carry the ball against United this season when under pressure, there’s a pattern. Teams seem to be getting stopped particularly frequently down Wan-Bissaka’s side. Of course, Wan-Bissaka now finds himself injured, so it’s possible that teams will begin to find more joy down this flank.

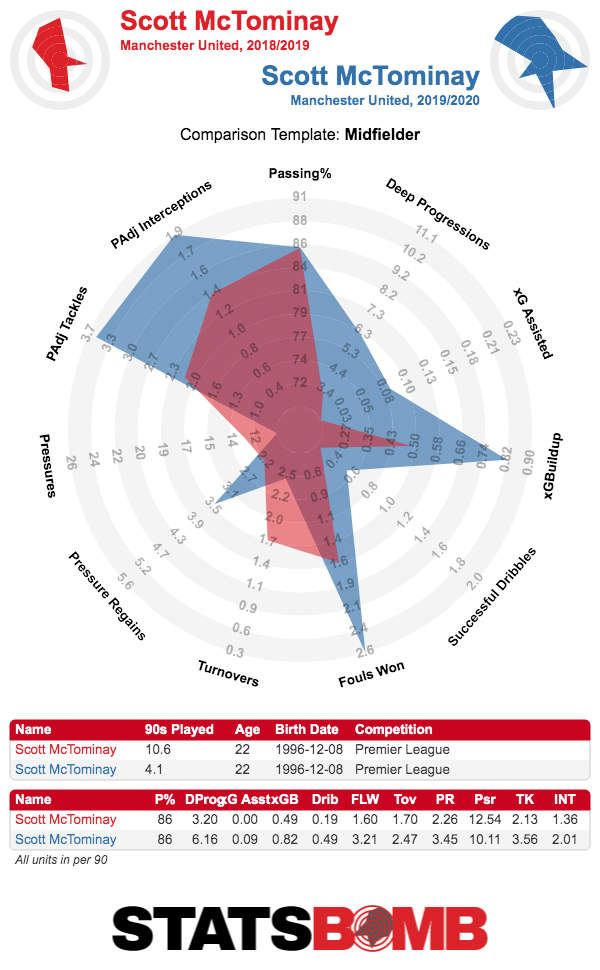

As for Wan-Bissaka, he’s won plaudits for his volume of tackles so far, but that’s not the real story. Defending is not about what you do, but what you stop your opponent from doing. Palace fans had a delightful song about Wan-Bissaka to the tune of “Rock the Casbah” with the line “your wingers don’t like him”, and that sums up what his game is about perfectly. At his best, he doesn’t let players he’s directly up against get past him. Can we find evidence for this in the numbers? Well here’s what there is. When looking at failed attempts to dribble or carry the ball against United this season when under pressure, there’s a pattern. Teams seem to be getting stopped particularly frequently down Wan-Bissaka’s side. Of course, Wan-Bissaka now finds himself injured, so it’s possible that teams will begin to find more joy down this flank.  In front of that back four is where it was thought that United would be flimsy, but not so far. Scott McTominay as the side’s primary ball winning midfielder seemed like a strange idea since he’d previously shown little aptitude for winning the ball. Now, it remains very early, and we’re talking about 10 tackles and 6 interceptions here, hardly a sample size worthy of huge extrapolation. But this is a promising start for him in a new role, as he’ll certainly need to keep it up if United are to hold this midfield together.

In front of that back four is where it was thought that United would be flimsy, but not so far. Scott McTominay as the side’s primary ball winning midfielder seemed like a strange idea since he’d previously shown little aptitude for winning the ball. Now, it remains very early, and we’re talking about 10 tackles and 6 interceptions here, hardly a sample size worthy of huge extrapolation. But this is a promising start for him in a new role, as he’ll certainly need to keep it up if United are to hold this midfield together.  The obvious area with less positive news, though, is in goal. When people put out their Premier League teams of the decade this December, it seems very likely that most will feature De Gea between the posts. There have been times when the Spaniard has seemed to single-handedly keep United afloat while everything around him was collapsing. But from the 2018 World Cup onwards, De Gea has seemed positively mortal. In the time since Solskjaer took the reins at Old Trafford, StatsBomb’s shot stopping model has had De Gea as almost exactly league average, after having previous periods of astonishing numbers. The early stages of this season have been notably worse than that, with De Gea already estimated to have cost United a goal more than the average ‘keeper. My instincts throughout this disappointing period have been to back the player who previously looked so good to turn it around, to expect that he’ll shake it off sooner rather than later. But these issues have been going on long enough that clearly something is up with him. Expected goals is an invaluable metric in understanding football and its increasing media prominence is undoubtedly a positive. In past years, United’s results would have told the whole story and everyone would have agreed that the club was in crisis. We can now see that the scorelines do not tell the whole story and there are positives to take from the four games so far, with the team having avoided conceding much in the way of real chances. But it’s important to understand what the numbers do and do not tell us. This team has not been attacking especially well, and three penalties clouds things somewhat. Perhaps if opposing players did not foul United in the box, those three moments would have led to some excellent opportunities that would boost the attacking xG. We will never know. What we also have to note is that this is just four games, and the approaches of the opposition sides has had a significant impact on these numbers. With the exception of the first half against Chelsea, United have not been facing opponents continually trying to force the issue and really push this team. The pattern of play for the most part has been of teams soaking up pressure and looking to counter. That they have struggled to counter effectively is something United should get credit for, yes, but we will have to wait and see if this defence holds up to being tested in other ways. On the attacking side, there are real questions to be answered. United have played better football than the results would suggest, yes. But that does not mean that there are not concerns, or that the performances will continue to look so positive in terms of xG. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

The obvious area with less positive news, though, is in goal. When people put out their Premier League teams of the decade this December, it seems very likely that most will feature De Gea between the posts. There have been times when the Spaniard has seemed to single-handedly keep United afloat while everything around him was collapsing. But from the 2018 World Cup onwards, De Gea has seemed positively mortal. In the time since Solskjaer took the reins at Old Trafford, StatsBomb’s shot stopping model has had De Gea as almost exactly league average, after having previous periods of astonishing numbers. The early stages of this season have been notably worse than that, with De Gea already estimated to have cost United a goal more than the average ‘keeper. My instincts throughout this disappointing period have been to back the player who previously looked so good to turn it around, to expect that he’ll shake it off sooner rather than later. But these issues have been going on long enough that clearly something is up with him. Expected goals is an invaluable metric in understanding football and its increasing media prominence is undoubtedly a positive. In past years, United’s results would have told the whole story and everyone would have agreed that the club was in crisis. We can now see that the scorelines do not tell the whole story and there are positives to take from the four games so far, with the team having avoided conceding much in the way of real chances. But it’s important to understand what the numbers do and do not tell us. This team has not been attacking especially well, and three penalties clouds things somewhat. Perhaps if opposing players did not foul United in the box, those three moments would have led to some excellent opportunities that would boost the attacking xG. We will never know. What we also have to note is that this is just four games, and the approaches of the opposition sides has had a significant impact on these numbers. With the exception of the first half against Chelsea, United have not been facing opponents continually trying to force the issue and really push this team. The pattern of play for the most part has been of teams soaking up pressure and looking to counter. That they have struggled to counter effectively is something United should get credit for, yes, but we will have to wait and see if this defence holds up to being tested in other ways. On the attacking side, there are real questions to be answered. United have played better football than the results would suggest, yes. But that does not mean that there are not concerns, or that the performances will continue to look so positive in terms of xG. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

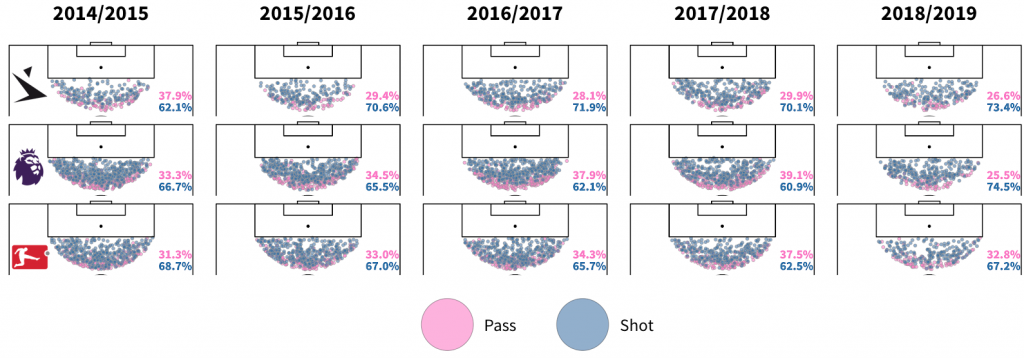

This week I was lucky enough to present a comprehensive analysis of the Danish Superliga to an audience of 300 coaches, analysts, and administrators in Danish Football. The report was commissioned to not only analyse how the league has changed over the last five seasons, but also to benchmark it against the German Bundesliga and English Premier League. Our analyst Euan Dewar did a great job on the analysis and preparing the report, and it was fun to once again be in a packed room of football people, discussing data analysis. My understanding is that the entire report will be made available to the public at some point in the future.

StatsBomb do this type of analysis for clubs, federations, and governing bodies fairly regularly, and it’s a huge compliment to be trusted to produce honest, insightful analysis about the game.

One thing that was absolutely clear in the report was that Danish teams remain innovators in one specific area: set pieces. Danish teams score consistently more goals from set pieces than pretty much every other league in the world, including ones with considerably more money and more talent. (For more analysis on this, check out my earlier piece I Think We Broke Denmark.)

Let me also make something else clear - more goals are not being scored off set pieces because the defenses are bad at defending this phase of the game. More goals are being scored because a number of Danish teams are simply better at executing them. And they are better at executing because they do things differently.

What are the differences? First of all, they shoot more often off direct free kicks.

This might seem a basic point - OH GEEZ TAEK MORE SHOTS, SCORE MOAR GOALS RAAAAR - but they also score a higher percentage of those shots. Danish teams convert 8% of their DFKs compared to 6% in the Premier League, and 5.7% in the Bundesliga. That’s a significant gap, and one that seems to suggest there is a lot of slack in execution for teams in the bigger leagues.

Alright, what else?

Danish teams also target and succeed at exploiting different spaces off corners. If you know the better positions of maximum opportunity and are able to deliver balls to those areas, you can score more goals off what is traditionally a low-return phase of the game. (Teams score off corners between 2 and 2.5% across the full data set. We have seen certain teams double or treble that for multiple seasons.)

And…?

Well, remember how Andy Gray mocked Liverpool hiring a long throw coach?

Look ma, nearly free goals! (Approximate value in the Premier League, £2.5M each.)

Only possible in Denmark? Nope:

Find the edges, then exploit them. One team in Liverpool is suddenly scoring a bunch of goals from long throws. The other one hired our favourite long throw coach--Thomas Gronnemark.

Set piece execution is one main reasons Liverpool are having their greatest ever Premier League season. We have Liverpool scoring 17 goals so far in the league and conceding 6 for a goal difference of +11 in this phase of the game. Manchester City are +2 (9 scored, 7 conceded). Without that gap, the goal difference between the two contenders would go from a gap of 8 to 19, and there would likely be no title race.

The same is true further down the table as well. Given how tight the Top 4 race is right now, it’s entirely possible a difference of a few goals off this phase of the game could swing Champions League qualification for next season. When qualification is an automatic passport to tens of millions, and the least an English club will receive this season is a minimum of £86m, any edge to traverse the gap or maintain participation is worth every penny of outlay. We’ll take some time to revisit this once the season ends.

A couple of notes before I wrap this up...

Set Piece Program

We are taking applications from professional teams that want to work with us on set pieces for next season. We only work with a couple of teams on this max every season, and are exclusive to one team per league. If you work for a professional team with significant budget (bringing you goals does not come cheap), please send me an email to ted@statsbomb.com. We will choose who we work with by the end of May, so if your team wants to be in the mix, now is the time.

Set Piece Courses

For everyone else, we have tickets available for three set piece courses in June in New York, London, and Los Angeles. The courses will be taught by me, and cover both process and execution of set pieces from a coaching and analysis perspective.

To my knowledge, no one else in the world teaches a course like this, and certainly no one who works with professional teams. I made the decision to teach this information to interested parties quite simply because I feel the game is ready to change, but needed more talented people with education to carry it out. Part of my commitment to StatsBomb and its audience has been to teach people more about the game and how it operates instead of hoarding the info, and this once again falls squarely under that umbrella.

Links to buy tickets can be found here:

I hope to see a lot of you this summer.

Ted Knutson

CEO, StatsBomb

ted@statsbomb.com

Header Image Courtesy of the Press Association

While you were paying attention to things that mattered like who won matches and who lost, some under the radar storylines are bubbling along that might eventually impact teams in important ways.

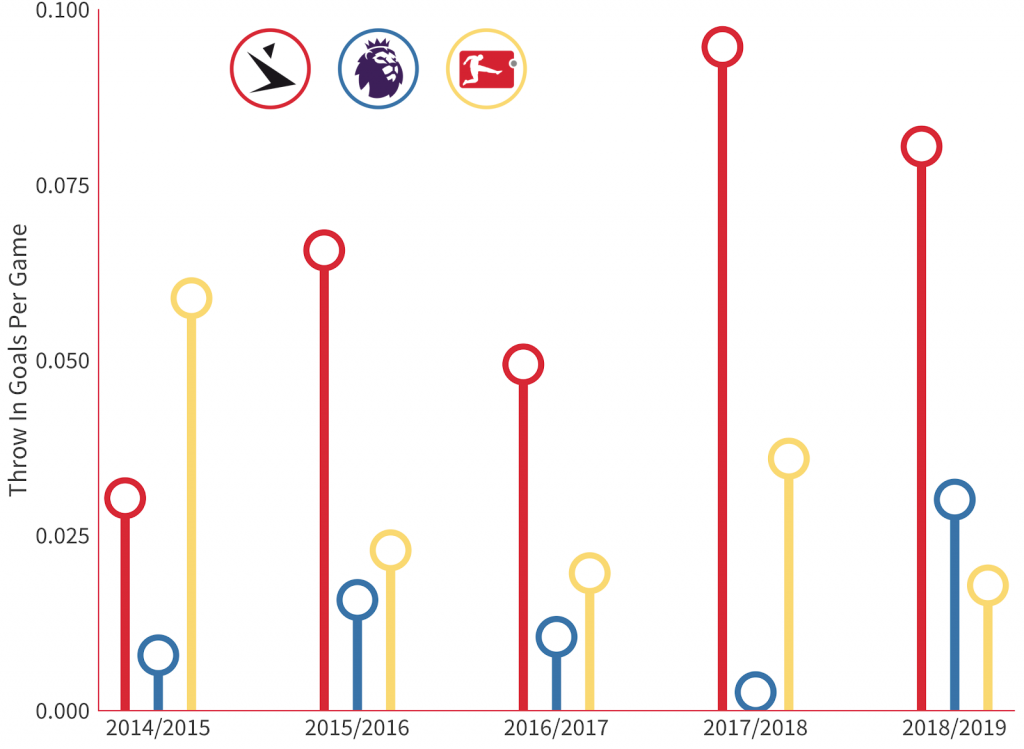

Can Gabriel Jesus Score?

This seems like the most absurd question in the world. He’s averaging 0.49 non-penalty goals per 90 minutes, so clear he can score. That’s a pretty good, if not absolutely spectacular number. For player that have played over 1000 minutes in Europe’s big five leagues this season, he’s narrowly in the top 50. That’s…fine. It’s probably even good enough to be the back up on perhaps the best team in Europe. It’s also significantly behind the man he backs up, Sergio Aguero who clocks in at 0.71 non-penalty goals per 90.

Expected goals, on the other hand, tells a much much rosier story. Jesus’s xG per 90 is at a whopping 0.70, that’s the fourth best total across Europe’s big five leagues, and a whisker ahead of Aguero’s 0.69. Jesus is also just 22 years old. Aguero is, of course, now on the wrong side of the 30. So, if the only thing that matters is xG then expect Jesus to be inheriting the reins of the attack any year now.

There are of course, mitigating factors here. Jesus is generally a substitute and generally plays against weaker opposition than the first choice forward, so his numbers probably get a bit of a boost. Everybody on that City machine reinforces everybody else, a training dummy parked at the penalty spot could probably put up a positive xG total. It’s nice to be the tip of a spear wielded by the likes of David Silva and Raheem Sterling. But still, there’s no denying that Jesus’s underlying numbers are excellent.

But, boy does that kid miss a lot.

Does it matter? From an analytics perspective it does not, the best bet is to play the kid, let him shoot through the yips and expect, as the numbers suggest, that he’s about to be a superstar. But, part of the reality of leading the line at the very top of the game is that if you haven’t proven you can do it, you don’t get a lot of time to prove you can do it. People (and coaches) remember the misses, the pressure mounts, fans get restless and eventually you become Alvaro Morata (who to be fair has never had xG like Jesus’s, but who has also, to be fair, never gotten to play striker on a team quite like City), and everybody just kind of agrees that while the numbers are fine, maybe it’s time for a change of scenery.

For now, Jesus has the luxury of being a backup, but if he does eventually get the job then he’s not going to have the luxury of all these whiffs going basically unnoticed.

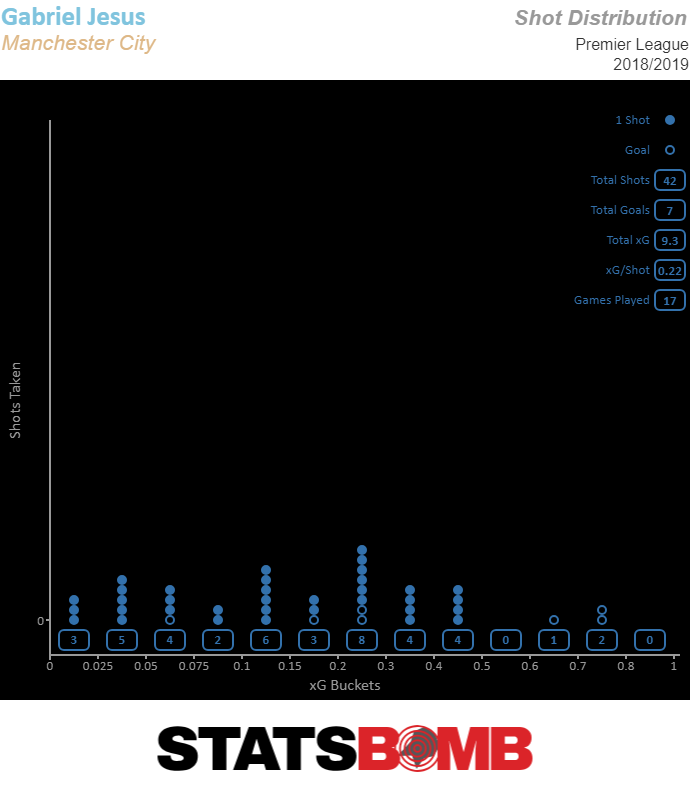

Eintracht Frankfurt’s Other Star Forwards

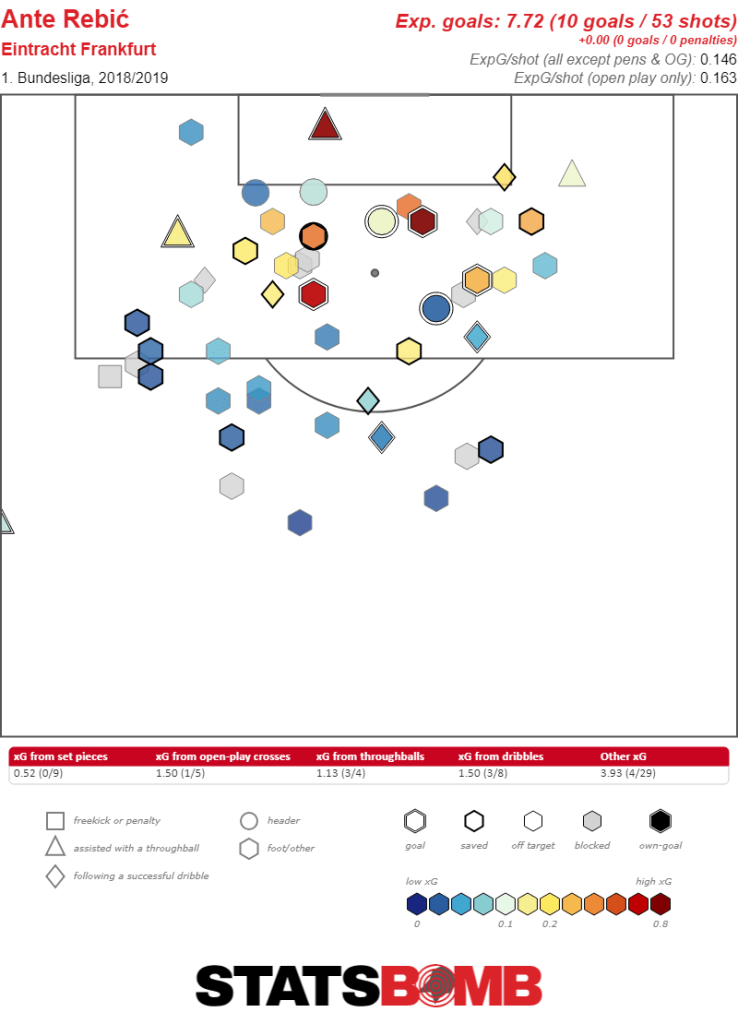

Luka Jovic gets the most attention, and well he should. He’s averaging 0.56 xG per 90, the 11th best total across Europe’s top five leagues, and it doesn’t hurt the old hype-o-meter that his actual goal scoring rate of 0.73 non-penalty goals per 90 is ahead of that pace. But, it’s not happening in a vacuum and the team’s other two main attackers, Sébastien Haller and Ante Rebić are right there with him with 0.40 and 0.42 xG per 90 and 0.48 and 0.52 non-penalty goals respectively.

While Jovic does a little bit of everything his teammates have slightly more defined roles. Haller as the more traditional forward gets the bulk of his shots from point blank range. He’s ruthlessly disciplined and almost always fires from 12 yards or closer.

Rebić on the other hand is as often a playmaker behind the striker partnership ahead of him as he is a striker himself. Consequently his output is less about efficiency, he averages 0.14 xG per shot as opposed to Haller’s excellent 0.21, and more about volume, he takes 2.93 shots per game as opposed to Haller’s 1.93.

Jovic, given his age and production, has garnered much of the hype, but the story of Eintracht Frankfurt’s season is that they have three attackers all of whom are 25 or younger, all of whom are putting up strong numbers and all of whom are outperforming those numbers. Either by strong planning or dumb luck, the team has put together the perfect attacking unit, one that is young, dynamic, and perfectly complementary. It’s no wonder that in addition to currently being the only German team alive in European competitions (even if only barely) they’re also holding onto fourth place in the Bundesliga and on track to qualify for next season’s Champions League.

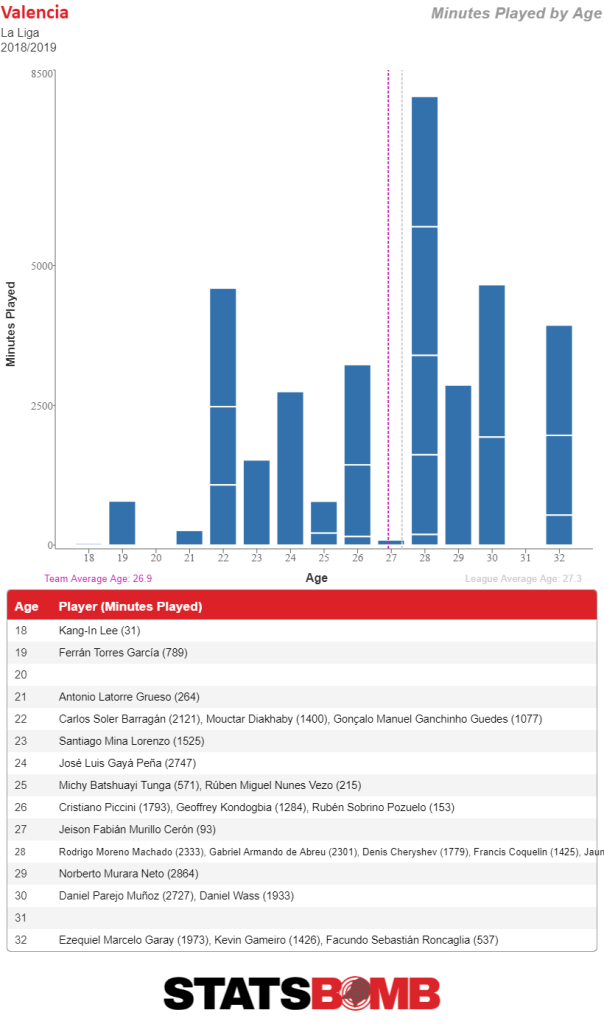

The Old Man of Valencia

Valencia have had a fascinating season. It’s not just that they started so slowly and are now coming on so strong, it’s that the team as currently constructed is an interesting hodgepodge of young and old.

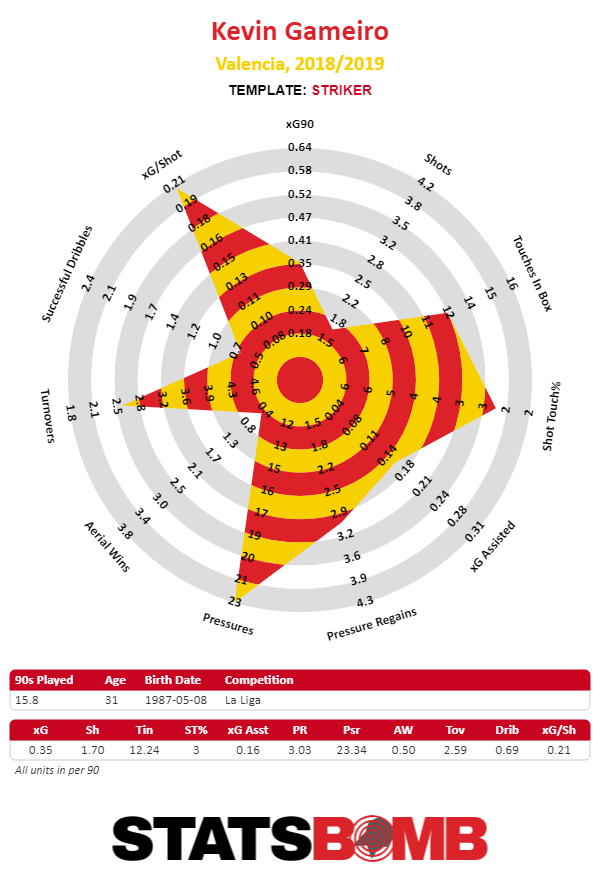

The kids, players like Carlos Soler, Gonçalo Guedes, Ferrán Torres (as well as Mouctar Diakhaby further back on the field) provide skill and hope for the future, but it’s some of the old hands who have done much to steady the uncertain ship. Specifically, Kevin Gameiro, less than a month from his 32 birthday continues to put up important numbers leading the line for Valencia.

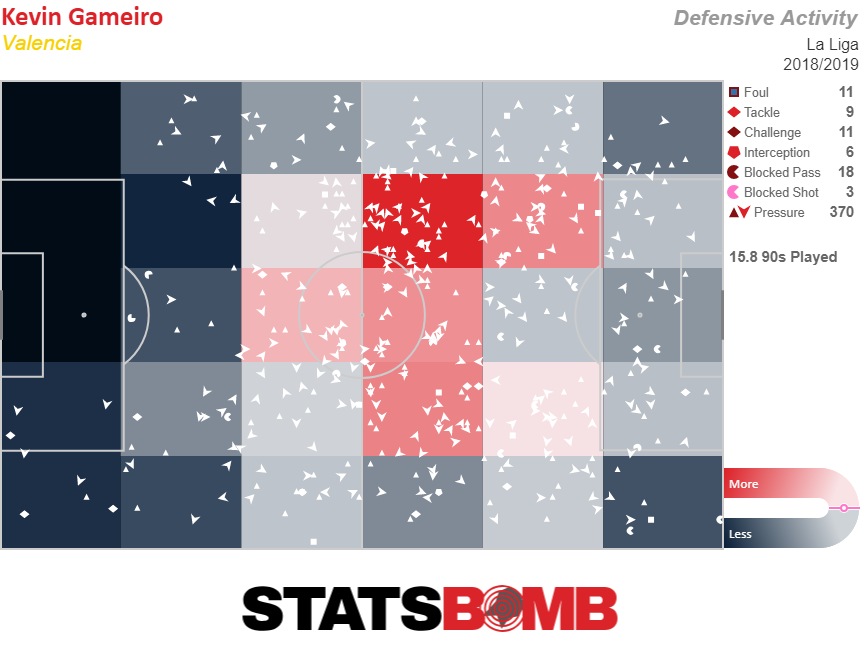

Despite his age, he’s an active defender. He’s happy to drop into Valencia's shape and harass the opposition as they attempt to enter the ball into midfield.

He pairs that defensive willingness with a lethal nose for goal. He only has four goals this season, though his expected goal total is somewhat higher at 5.41. But, he’s also only taken 27 total shots. He’s one of only six players across Europe’s top five leagues this season who have managed at least 0.33 xG per 90 and over 0.20 xG per shot.

Gameiro has shown to have a perfect set of skills for this Valencia side. He doesn’t need the ball a lot, which allows their younger, more exciting players to feature but he’s happy to do all sorts of dirty work from the striker position that lets them shine. Then, on the rare occasions when he does shoot, he does it from absolutely lethal positions. His game is perfectly suited to letting the kids have the spotlight, because he has enough edge to pounce when the opposition fails to take him into account. If Valencia manage to finish their remarkable second half of the season comeback, and nip fourth place at the wire, it will provide them a Champions League platform to feature their exciting prospects next season, but it will be thanks in no small part to the veterans that they got there.

StatsBomb is unveiling three new (to us) passing metrics to better profile passers in professional football. Why passing metrics? Because this is football and passing is omnipresent. For better or for worse, the ubiquitous event may need even more attention than we’re already giving it. It is our objective through these metrics to evaluate a passer’s creativity, their predictability and frankly their overall passing ability.

Thanks to some of the great work by peers made publicly available, we were able to put these together without too much time consuming innovation. We will release the metrics in a series of posts to spread out the joy and peak the eagerness for all you nerds. The first metric we are releasing today is “Pass Uniqueness”.

Pass Uniqueness Methodology

“Pass Uniqueness” is a variation on previous work (I am not claiming the novelty of this idea in the slightest, but I am expanding on it thanks to the vast amount of data over here at StatsBomb). The original methodology is available on FC RStat’s GitHub, you can even find the original code. The advantage of a uniqueness metric is to see which players make less common passes than others. Although, as the original write up notes, a less common pass is not necessarily an advantageous one. It could be completely erratic, but in and of itself it is unique. In a follow up post, we will talk about identifying advantageous passes.

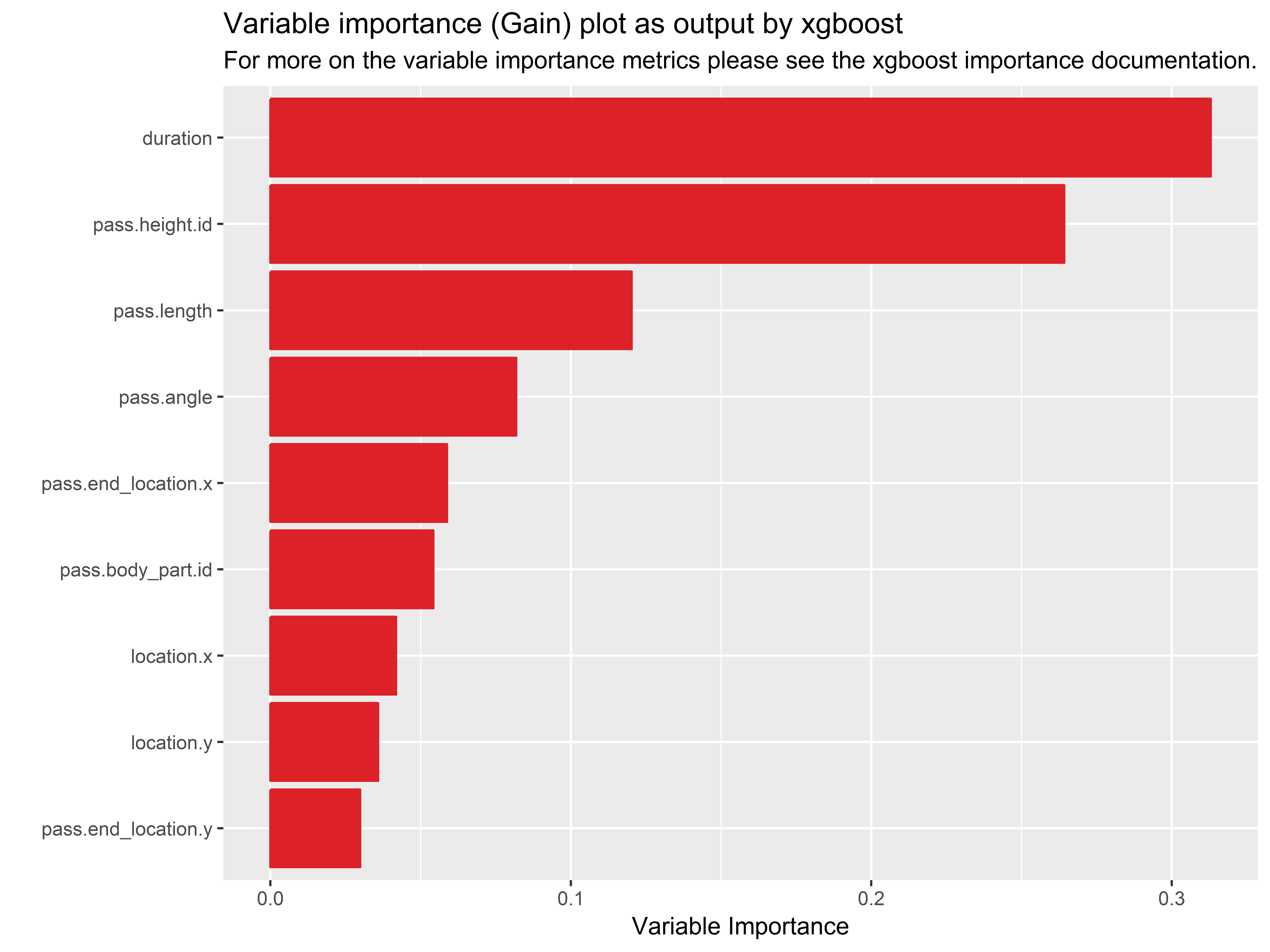

The basis for these methods is largely the same as previous iterations, however we make some key extensions that require a bit different methodology. We extract the similar following variables describing each pass:

- duration

- length

- angle

- height.id (1 = Ground Pass, 2 = Low Pass, 3 = High Pass)

- body_part.id (1 = Right Foot, 2 = Left Foot, 3 = Other)

- location.x

- location.y

- end_location.x

- end_location.y

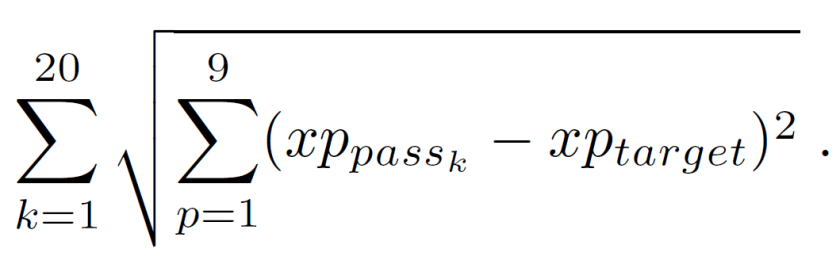

At the competition level, we then do a KNN search for the 20 most similar passes (k = 20) to each individual pass (target). Most similar is defined as the closest passes in Euclidean distance to the target pass. The “uniqueness” metric is calculated as the sum of the euclidean distances for all k = 20 passes. More formally,

There is some controversy in using Euclidean distance with categorical variables like height.id and body_part.id. However, for simplicity, we make the intentionally, naive assumption that their numeric IDs are continuous and we order them intuitively so that Ground Pass is closer to Low Pass which is closer to High Pass.

There are other metrics to better account for categorical variables and a good reference for KNN distance metrics can be found here. Since the euclidean distance is aggregated across all variables in the search, it is important that we scale all variables to have the same mean 0 and standard deviation 1. Otherwise, variables on a larger scale would unjustly carry more weight just because their individual distance metric would be larger than the other covariates.

The R package FNN makes this search very quick, a data set of 3.2 million passes takes about 2 minutes to run. To reduce dimensions and to keep the sample for each search more homogeneous, we only search for nearest neighbors inside of each league and backdating up to one season. It’s important to note a limitation here. The limitation is that with larger sample sizes there is a higher propensity for more similar passes and as a result fewer unique passes due to the lower euclidean distances. In order to make the uniqueness metric more scalable across bigger and smaller competitions, it would make sense to set k equal to a proportion of the total population within each competition.

We account for that limitation in a different way. We extend the KNN search into a model based method. Using the “uniqueness” value calculated from the KNN search in each league, we then regress the uniqueness value on the same covariates in the original search. We could do this in a simple linear regression, but one would have to properly specify the non-linear relationship between location coordinates and the uniqueness. Instead, we use a tree based method to handle the non-linearities seamlessly. Using extreme gradient boosting (xgboost), we construct trees with a maximum depth of 12 different predictor combinations training for 1000 rounds.

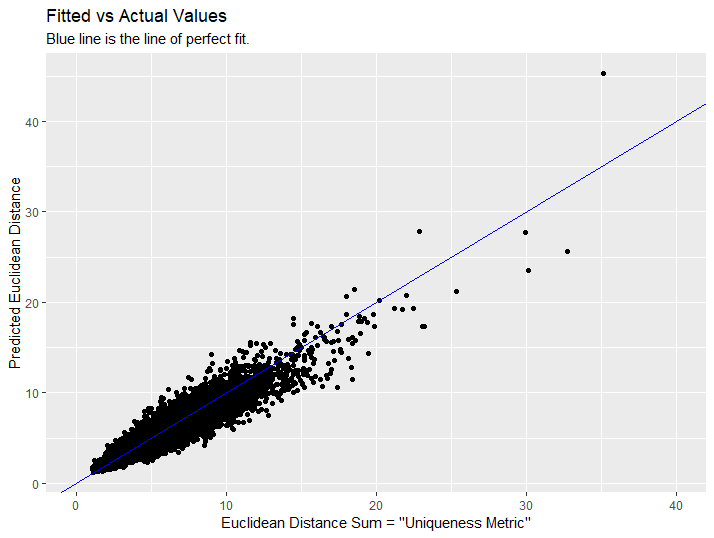

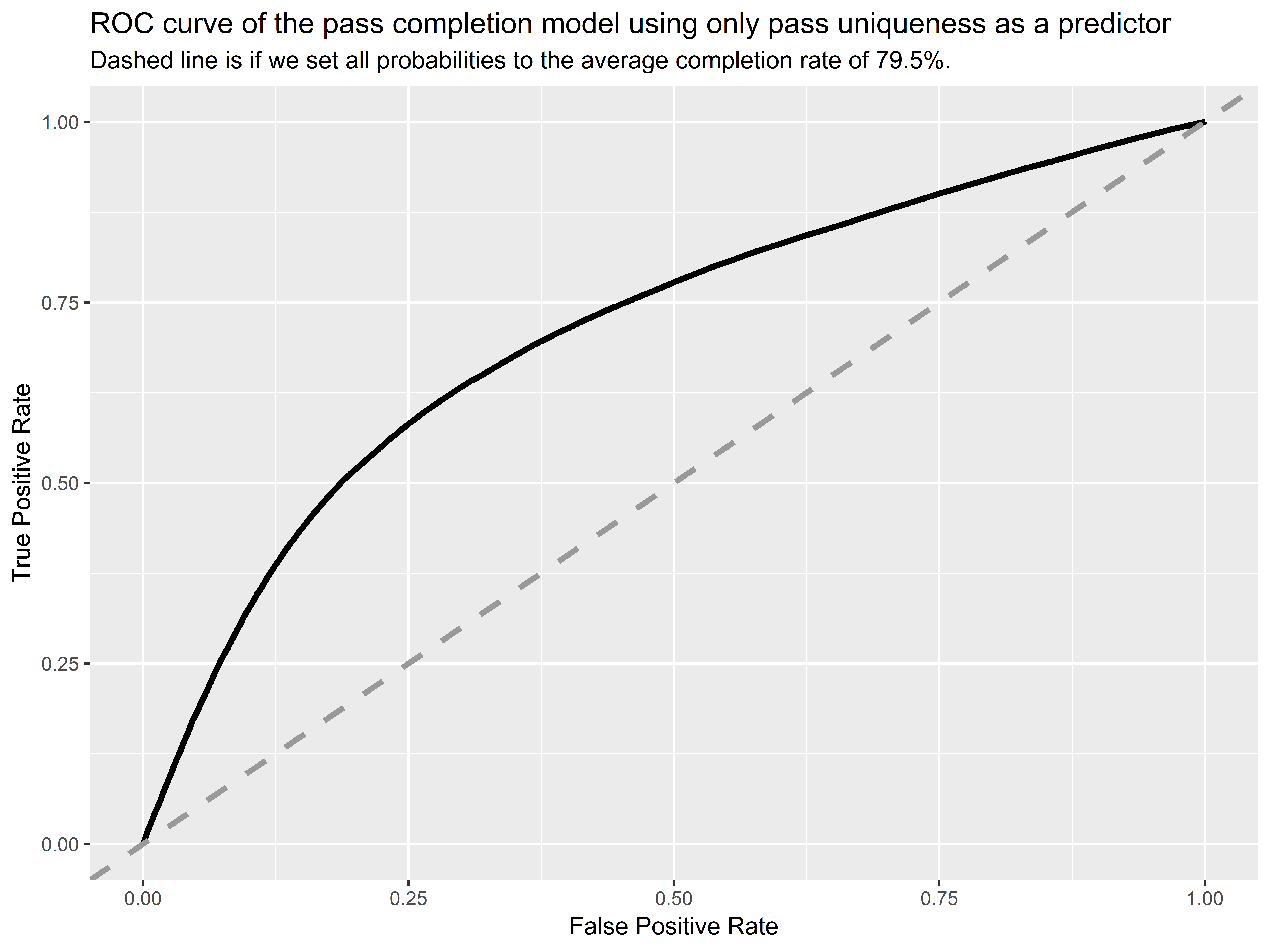

We then check the correlation between the actual uniqueness from the KNN search and the predicted uniqueness from the xgboost method. A scatterplot of our results is shown below:

Correlation

It looks like we did pretty well! The correlation between observed uniqueness and predicted uniqueness was 0.967!

Now, why is this model based extension helpful? There are a few reasons. The first is that the original framework of the uniqueness metric requires searching an entire competition at each update. That can be computationally expensive especially if you have to update competitions 2-3 times a week. Secondly, the results are dependent on the individual competitions that they are in and therefore cannot easily extend into new competitions, especially competitions with fewer matches.

Using a model based approach allows us to quickly extend the “uniqueness” metric to new passes in new matches and competitions. The model based approach also allows us to further investigate the most important features influencing the actual “uniqueness” value.

Applications

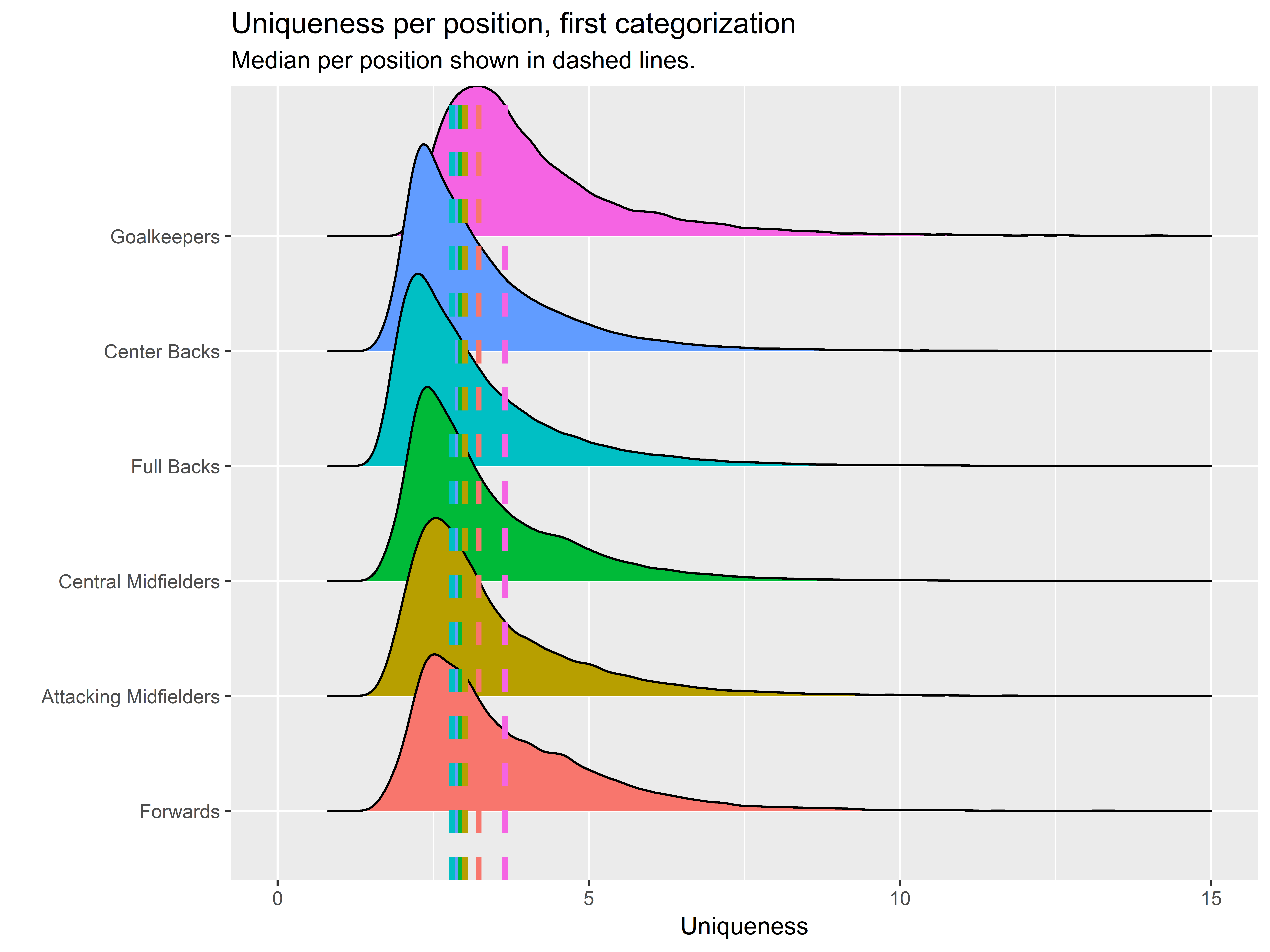

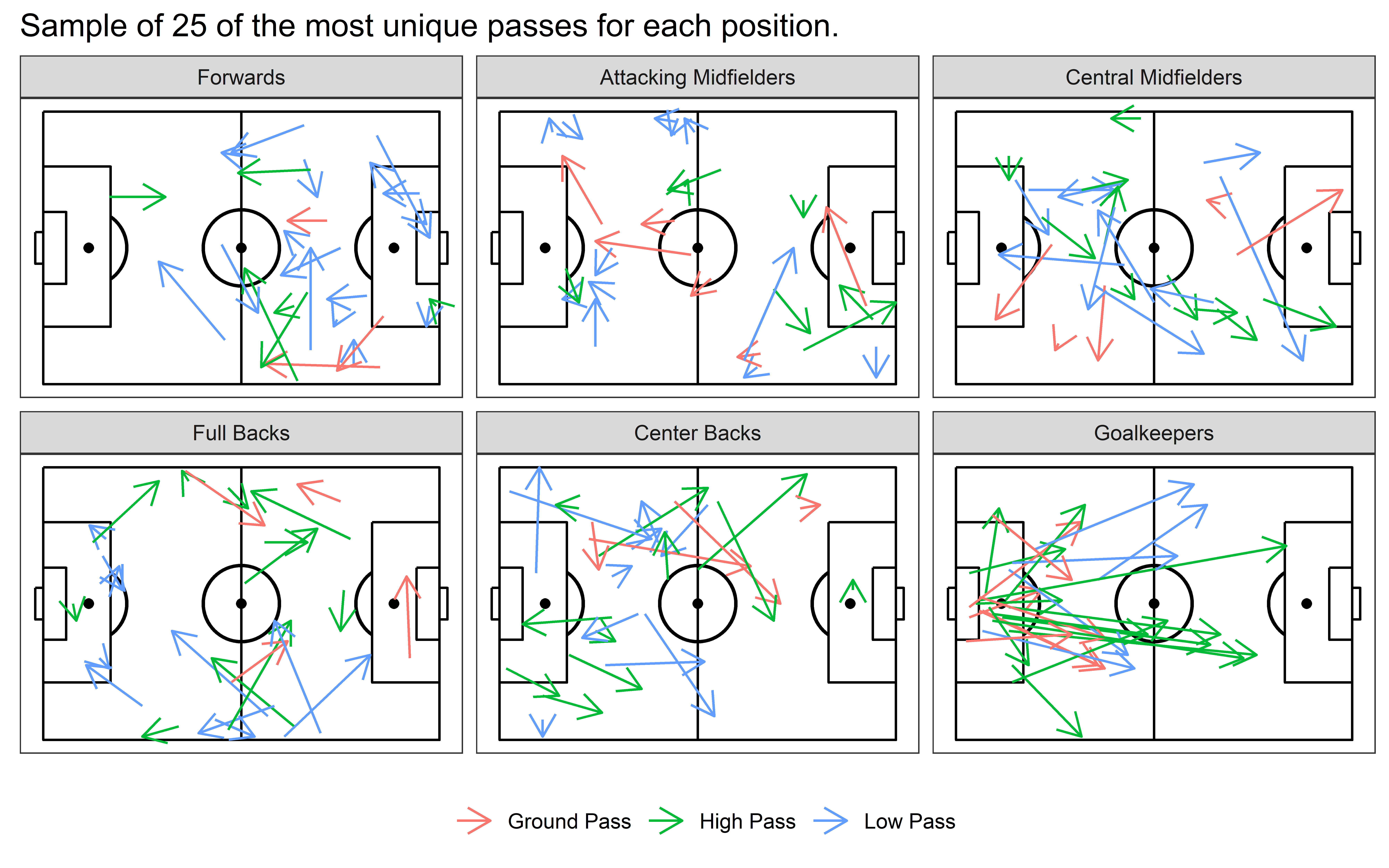

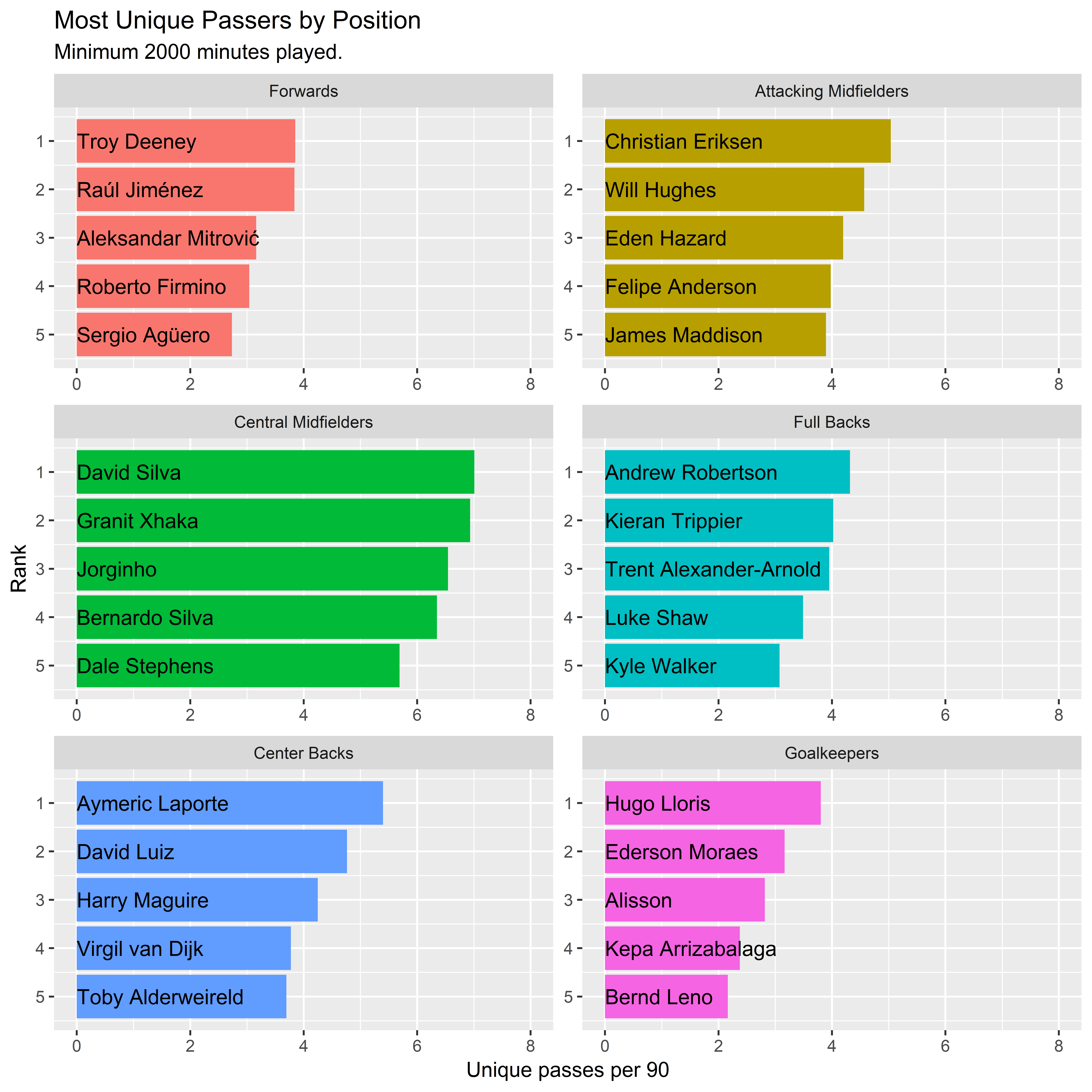

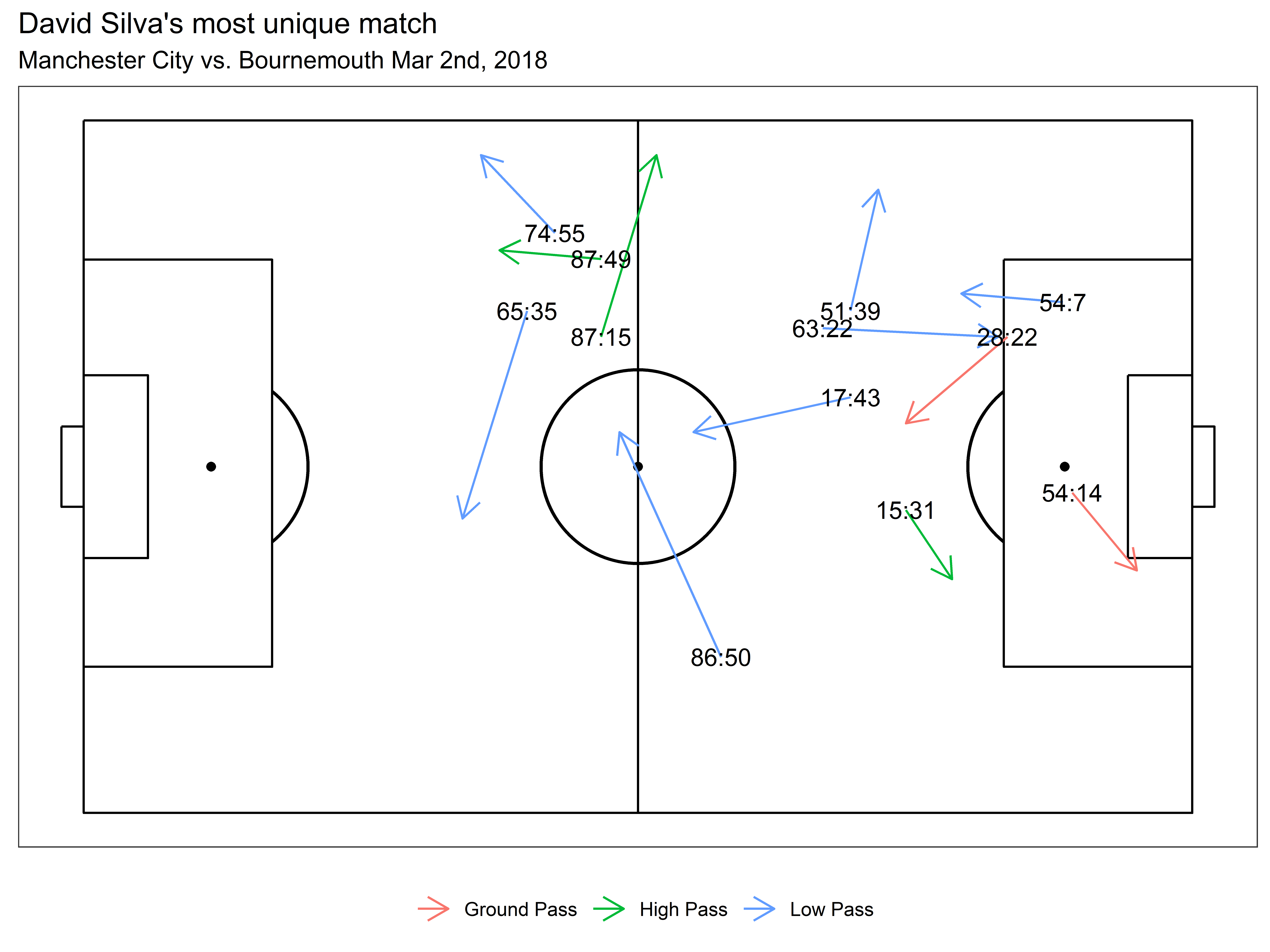

With that long winded methodology out of the way, let’s get into all the cool and intriguing applications. The uniqueness metric describes passes that are more unusual than most. It can separate extraordinary passers from the ordinary and it can be used to better grade pass difficulty, pass predictability and positive attacking contribution. Let’s first look at the distribution of pass uniqueness for different player’s positions.

The density plot above proves a very interesting point and also highlights a potentially limiting factor of this metric. Goalkeepers are the most “unique” passers in the game! Much as I’d like to shout out my beloved and under-appreciated position, unfortunately, that just can’t be the case. If goalkeepers were the most unique passers in the game they wouldn’t be playing in net.