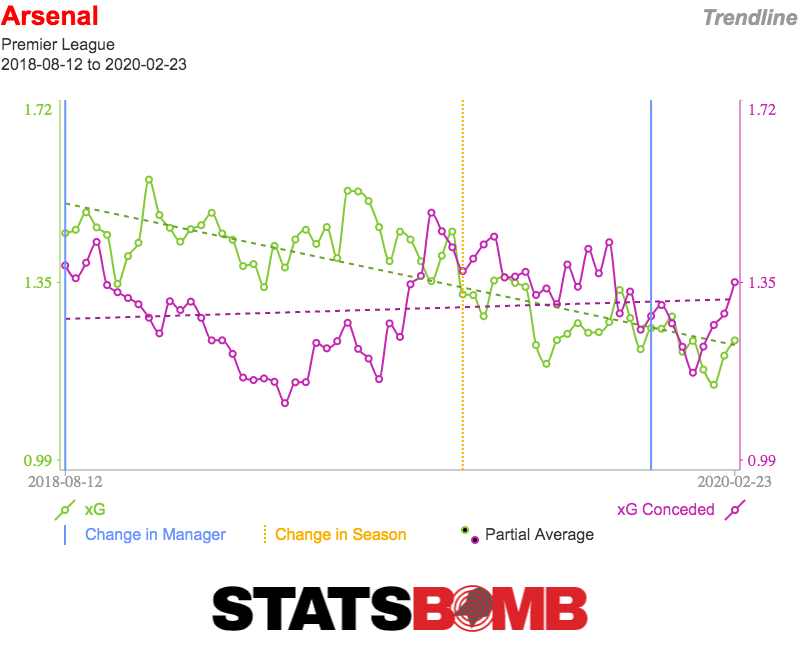

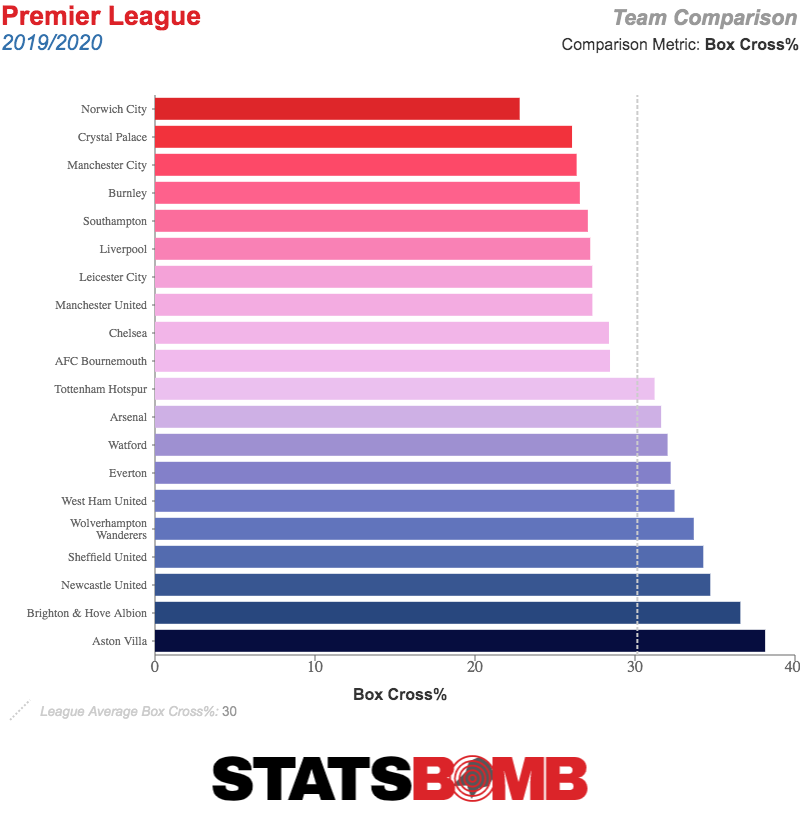

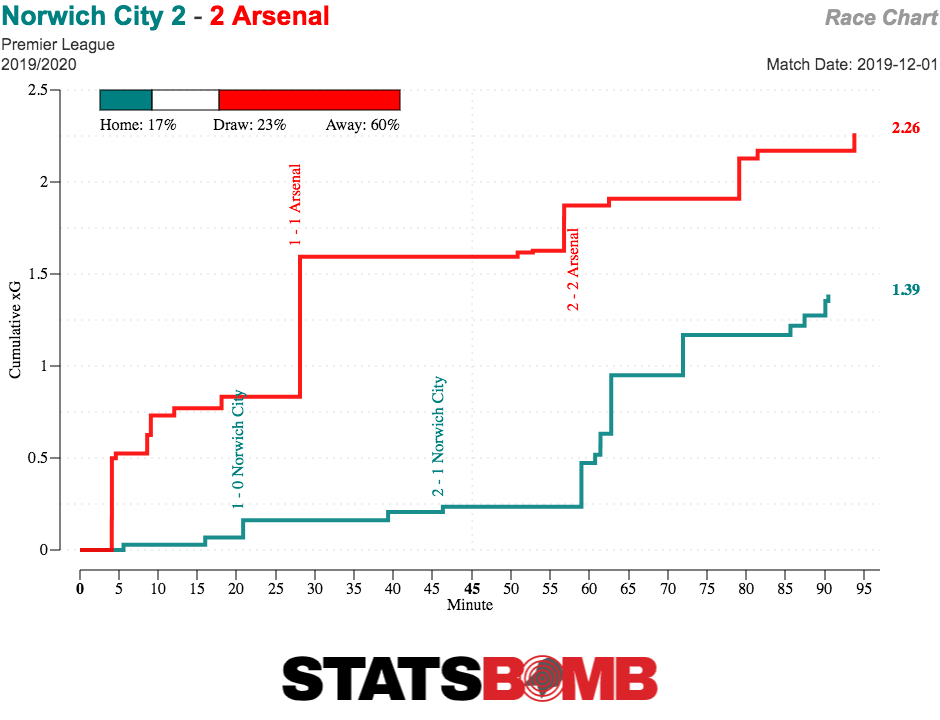

Whatever the post-Arsène Wenger era at Arsenal was supposed to be, it wasn’t this. The thing about Unai Emery’s Arsenal is that no one really knew how good they were supposed to be. There was a sense among many that Wenger was underachieving with this squad, and someone else should be able to produce more with these players, but there was no firm sense of how much more. Emery was tasked with setting the terms of this and, if we are merely to take it by what he achieved, the answer seemed to be that this squad isn’t capable of much more than what we’d already seen. When looking at the expected goals trendlines from August 2017 to the present, that late Wenger era looks almost like a golden age by comparison.  However you slice it, Emery’s Arsenal just were not good. Their xG difference per game this season of +0.09 put them seventh-best in the Premier League with a cataclysmic gap between the Gunners and the top sides. But that might not have been what frustrated fans most. What arguably grated even more was the way in which Arsenal were mediocre. This is a side that conceded more shots than they took. It’s a side that had so little ability to exert control over games that they faced more shots than all but two teams in the league. What they were able to do is keep the shot quality down, and their xG per shot faced is the second-lowest in the top flight. But is this how a club of Arsenal’s ambitions are “supposed” to be doing it? Facing a lot of shots of low quality suggests a team ceding control of the game, allowing opponents to attack them at will, but protecting against this by getting bodies behind the ball and forcing teams to put cheap crosses in or take potshots from range. This is a strategy one would expect to see from a team in the bottom half of the table, acknowledging their technical inferiorities and trying to make things difficult for better opponents. Quite why Emery seemed unfazed by conceding so many shots against sides like Southampton and Watford is a mystery. The picture wasn’t much brighter in attack. If the Wenger era is remembered for fluid, intricate football in the final third that sometimes proved effective, the Emery era will likely be remembered for functional football in the final third that failed to be any more efficient. Take passes in the opponent’s box as an example. Arsenal long dominated this stat, and their five per game in Wenger’s last season was more than even Pep Guardiola’s symphonic Manchester City. This season, that figure has fallen to 3.44, fifth in the Premier League behind even West Ham. Similarly, Arsenal are much more reliant on crosses to pump the ball into the box. In 2017–18, only 24% of their box entries came from crosses, the fewest in the league. This season, it’s 32%, slightly above average for a side in England’s top flight. The plan tends to be some form of just getting the ball into a decent area and hope one of the attackers, most frequently Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang, gets something on it.

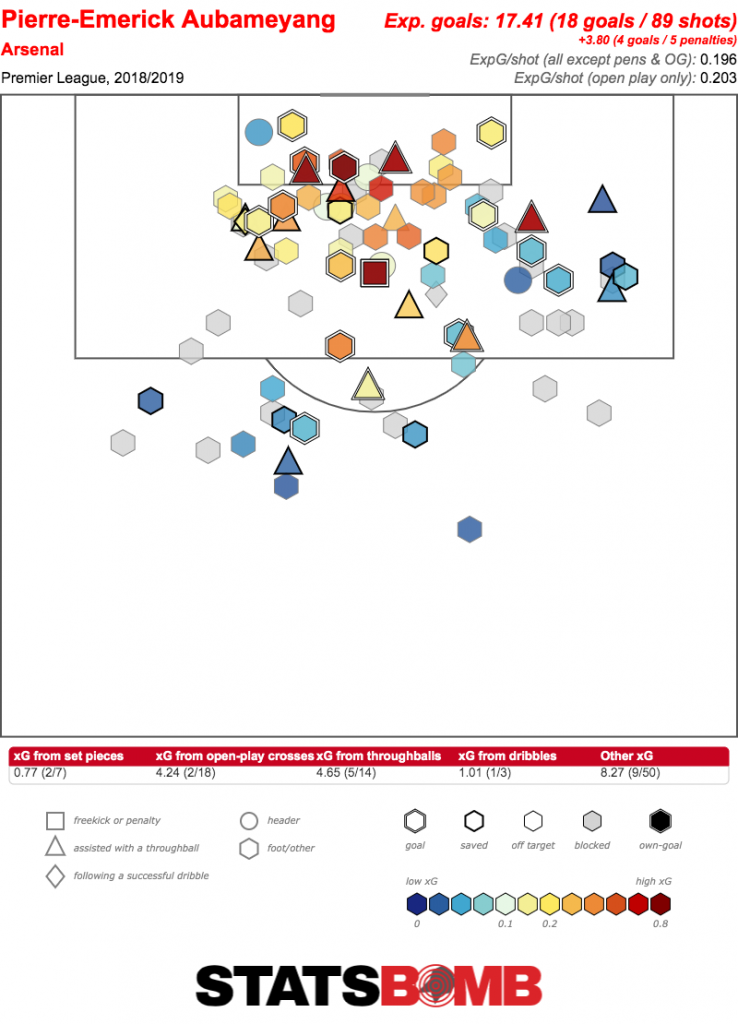

However you slice it, Emery’s Arsenal just were not good. Their xG difference per game this season of +0.09 put them seventh-best in the Premier League with a cataclysmic gap between the Gunners and the top sides. But that might not have been what frustrated fans most. What arguably grated even more was the way in which Arsenal were mediocre. This is a side that conceded more shots than they took. It’s a side that had so little ability to exert control over games that they faced more shots than all but two teams in the league. What they were able to do is keep the shot quality down, and their xG per shot faced is the second-lowest in the top flight. But is this how a club of Arsenal’s ambitions are “supposed” to be doing it? Facing a lot of shots of low quality suggests a team ceding control of the game, allowing opponents to attack them at will, but protecting against this by getting bodies behind the ball and forcing teams to put cheap crosses in or take potshots from range. This is a strategy one would expect to see from a team in the bottom half of the table, acknowledging their technical inferiorities and trying to make things difficult for better opponents. Quite why Emery seemed unfazed by conceding so many shots against sides like Southampton and Watford is a mystery. The picture wasn’t much brighter in attack. If the Wenger era is remembered for fluid, intricate football in the final third that sometimes proved effective, the Emery era will likely be remembered for functional football in the final third that failed to be any more efficient. Take passes in the opponent’s box as an example. Arsenal long dominated this stat, and their five per game in Wenger’s last season was more than even Pep Guardiola’s symphonic Manchester City. This season, that figure has fallen to 3.44, fifth in the Premier League behind even West Ham. Similarly, Arsenal are much more reliant on crosses to pump the ball into the box. In 2017–18, only 24% of their box entries came from crosses, the fewest in the league. This season, it’s 32%, slightly above average for a side in England’s top flight. The plan tends to be some form of just getting the ball into a decent area and hope one of the attackers, most frequently Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang, gets something on it.  We don’t yet have a sense of who the next Arsenal manager will be. Names such as Carlo Ancelotti, Mikel Arteta, Max Allegri and Marcelino have been floated, all of whom have very different footballing philosophies and managerial approaches. This suggests Arsenal have no clear blueprint outlining what they want to be going forward. What they have is a disparate set of talented players into whom Emery was unable to instill a distinct type of football. But what could someone else do with this squad? At the top end, there is obvious quality, but a strange unease with how the pieces fit together. Aubameyang has been, most would agree, Arsenal’s outstanding player since his arrival in January 2018. His game, ever since Thomas Tuchel reinvented him four years ago, has been about making himself available in the box and positioning himself to get on the end of a good number of very high-quality chances, which he subsequently finishes at a reasonable rate. Whatever he may have been earlier in his career, Aubameyang’s best work now comes within the width of the six-yard box.

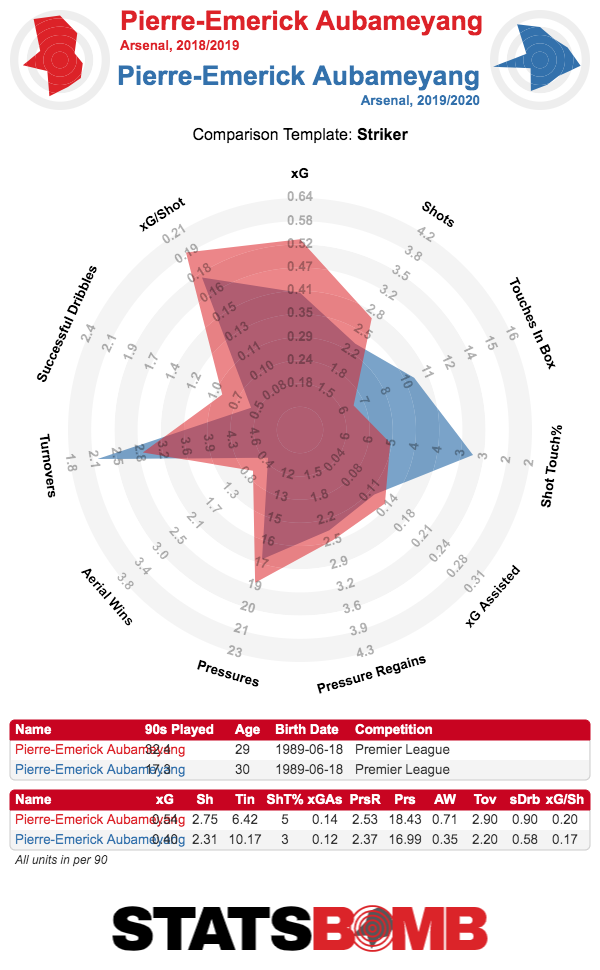

We don’t yet have a sense of who the next Arsenal manager will be. Names such as Carlo Ancelotti, Mikel Arteta, Max Allegri and Marcelino have been floated, all of whom have very different footballing philosophies and managerial approaches. This suggests Arsenal have no clear blueprint outlining what they want to be going forward. What they have is a disparate set of talented players into whom Emery was unable to instill a distinct type of football. But what could someone else do with this squad? At the top end, there is obvious quality, but a strange unease with how the pieces fit together. Aubameyang has been, most would agree, Arsenal’s outstanding player since his arrival in January 2018. His game, ever since Thomas Tuchel reinvented him four years ago, has been about making himself available in the box and positioning himself to get on the end of a good number of very high-quality chances, which he subsequently finishes at a reasonable rate. Whatever he may have been earlier in his career, Aubameyang’s best work now comes within the width of the six-yard box.  Alexandre Lacazette is also a definite centre forward, and has at times combined well with Aubameyang in a kind of throwback way to classic strike partnerships of old. This made the decision to recruit Nicolas Pépé all the more bizarre. Pépé is very much an inverted right winger in the mould of Arjen Robben or Mohamed Salah. We saw what he does best against West Ham on Monday, dribbling inside from the right flank and using his dominant left foot. Fitting all three of these players in the same side feels like a game of rock-paper-scissors in that someone is going to inevitably lose out. Play Pépé on the right of a 4-4-2 system and you lose his quality coming inside. Play him higher in a 4-2-3-1 and Lacazette has to drop into an unfamiliar deeper role. Play a 4-3-3 shape and Aubameyang has to move wide, finding himself less able to get on the end of chances in the box. The third option seems to be the most frequent, while also the most perplexing. Aubameyang has continued scoring goals this season, but is running somewhat over his xG (10 non-penalty goals scored from 6.99 expected) and is getting fewer good chances overall than last season. Whoever gets the job at the Emirates needs to make a decision in terms of who to prioritise and who to sacrifice. There doesn’t seem a way to get all three of these players firing.

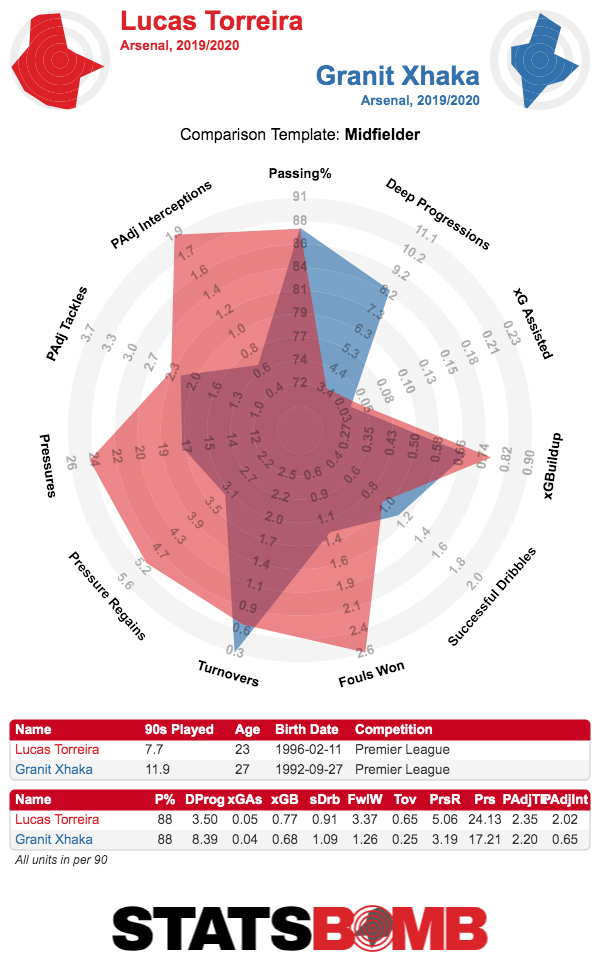

Alexandre Lacazette is also a definite centre forward, and has at times combined well with Aubameyang in a kind of throwback way to classic strike partnerships of old. This made the decision to recruit Nicolas Pépé all the more bizarre. Pépé is very much an inverted right winger in the mould of Arjen Robben or Mohamed Salah. We saw what he does best against West Ham on Monday, dribbling inside from the right flank and using his dominant left foot. Fitting all three of these players in the same side feels like a game of rock-paper-scissors in that someone is going to inevitably lose out. Play Pépé on the right of a 4-4-2 system and you lose his quality coming inside. Play him higher in a 4-2-3-1 and Lacazette has to drop into an unfamiliar deeper role. Play a 4-3-3 shape and Aubameyang has to move wide, finding himself less able to get on the end of chances in the box. The third option seems to be the most frequent, while also the most perplexing. Aubameyang has continued scoring goals this season, but is running somewhat over his xG (10 non-penalty goals scored from 6.99 expected) and is getting fewer good chances overall than last season. Whoever gets the job at the Emirates needs to make a decision in terms of who to prioritise and who to sacrifice. There doesn’t seem a way to get all three of these players firing.  The midfield also lacks obvious answers. Granit Xhaka offers passing range from deep areas, but his fairly obvious weaknesses in terms of discipline and defensive control are likely no secret to anyone reading this. A side would need to be very confident in its ability to control a game to really trust Xhaka as the deepest midfielder. Torreira offers better defensive work rate and energy, which in theory should compliment Xhaka, but the two seem to create a strange anti-chemistry with no midfield control and little defensive solidity when playing together. Matteo Guendouzi remains the great hope of Arsenal’s midfield and certainly has a strong case for playing every week, but his weaknesses in understanding without the ball mean he’s not necessarily a fix alongside Xhaka and Torreira.

The midfield also lacks obvious answers. Granit Xhaka offers passing range from deep areas, but his fairly obvious weaknesses in terms of discipline and defensive control are likely no secret to anyone reading this. A side would need to be very confident in its ability to control a game to really trust Xhaka as the deepest midfielder. Torreira offers better defensive work rate and energy, which in theory should compliment Xhaka, but the two seem to create a strange anti-chemistry with no midfield control and little defensive solidity when playing together. Matteo Guendouzi remains the great hope of Arsenal’s midfield and certainly has a strong case for playing every week, but his weaknesses in understanding without the ball mean he’s not necessarily a fix alongside Xhaka and Torreira.  Defensively, things are what might be politely called unclear. Héctor Bellerín has returned from injury as the first choice right back out of inertia more than anything else, without an obvious challenger as Ainsley Maitland-Niles has made it clear he prefers to play in midfield. Bellerín should be afforded time to regain full match sharpness, but his weaknesses defensively were obvious even before the injury. David Luiz is another player I doubt many reading this do not already have an opinion on. What has been the case in his career is that he can perform well in a well-drilled system, such as Antonio Conte’s Chelsea side, but is prone to making rash decisions when left with a lot of choices to make. Arsenal have been so far from a well-drilled system as to make this feel like a cruel joke on Mr. Luiz. Sokratis can’t be said to be doing much better, but both could make the very reasonable case that they’re not receiving anything like the protection they hope for. At left back, Kieran Tierney has yet to feature much. It's always hard to gauge how a player will adapt from the Scottish Premiership, though the better judges of football in Scotland insist he is the real deal. At the very least, he should be a significant athleticism upgrade on Sead Kolašinac. What should be fairly obvious by now is just how much of a mess this Arsenal squad is. Emery’s side lacked a clear identity, and much of that is his fault, but it’s also far from obvious what it is this group of players should do in an ideal world. It’s likely that a long rebuilding process is coming, as the first attempted reboot post-Wenger burns out. The next manager, then, has one most pressing task: decide on a vision and make the hard choices toward executing it, even if it is to the detriment of the quality of players on the pitch. Arsenal will not be fixed today, or tomorrow. A clear plan and strategy in both recruitment and coaching is the only way that change can come about.

Defensively, things are what might be politely called unclear. Héctor Bellerín has returned from injury as the first choice right back out of inertia more than anything else, without an obvious challenger as Ainsley Maitland-Niles has made it clear he prefers to play in midfield. Bellerín should be afforded time to regain full match sharpness, but his weaknesses defensively were obvious even before the injury. David Luiz is another player I doubt many reading this do not already have an opinion on. What has been the case in his career is that he can perform well in a well-drilled system, such as Antonio Conte’s Chelsea side, but is prone to making rash decisions when left with a lot of choices to make. Arsenal have been so far from a well-drilled system as to make this feel like a cruel joke on Mr. Luiz. Sokratis can’t be said to be doing much better, but both could make the very reasonable case that they’re not receiving anything like the protection they hope for. At left back, Kieran Tierney has yet to feature much. It's always hard to gauge how a player will adapt from the Scottish Premiership, though the better judges of football in Scotland insist he is the real deal. At the very least, he should be a significant athleticism upgrade on Sead Kolašinac. What should be fairly obvious by now is just how much of a mess this Arsenal squad is. Emery’s side lacked a clear identity, and much of that is his fault, but it’s also far from obvious what it is this group of players should do in an ideal world. It’s likely that a long rebuilding process is coming, as the first attempted reboot post-Wenger burns out. The next manager, then, has one most pressing task: decide on a vision and make the hard choices toward executing it, even if it is to the detriment of the quality of players on the pitch. Arsenal will not be fixed today, or tomorrow. A clear plan and strategy in both recruitment and coaching is the only way that change can come about.

Stats of Interest

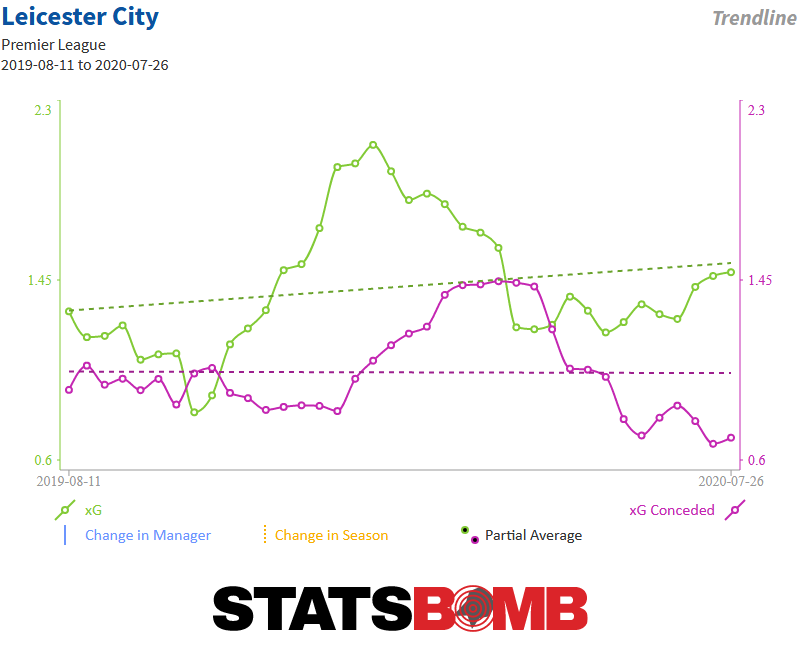

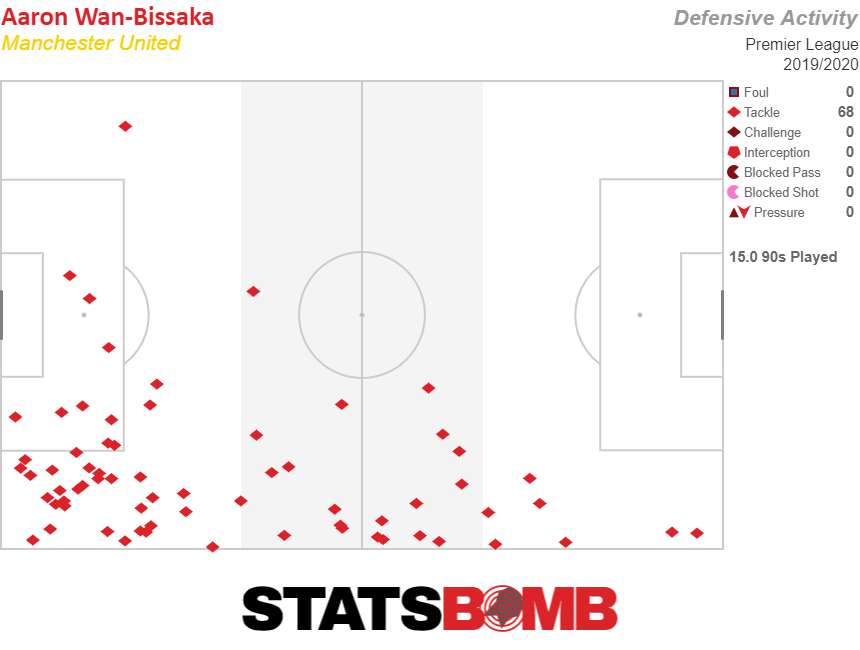

Leicester had the rub of the green in the early going this season, picking up a number of good results above and beyond their underlying performances. But recent games have seen a different trend. A number of xG dominant wins have caused a fairly dramatic turnaround on their trendlines. This is the form the Foxes need to put up a title challenge.  Aaron Wan-Bissaka put in an excellent defensive performance against Manchester City last weekend, locking down Manchester United’s right flank. It’s well known that he makes a lot of tackles, and his possession-adjusted 4.62 per 90 puts him in the top 5 players in the league on this stat. What’s really impressive is that none of the other players near the top of this list have a better ratio of being able to make a tackle instead of getting dribbled past than his 80%. For all the challenges he makes, he rarely gets caught out, and may well be the best tackler in the Premier League.

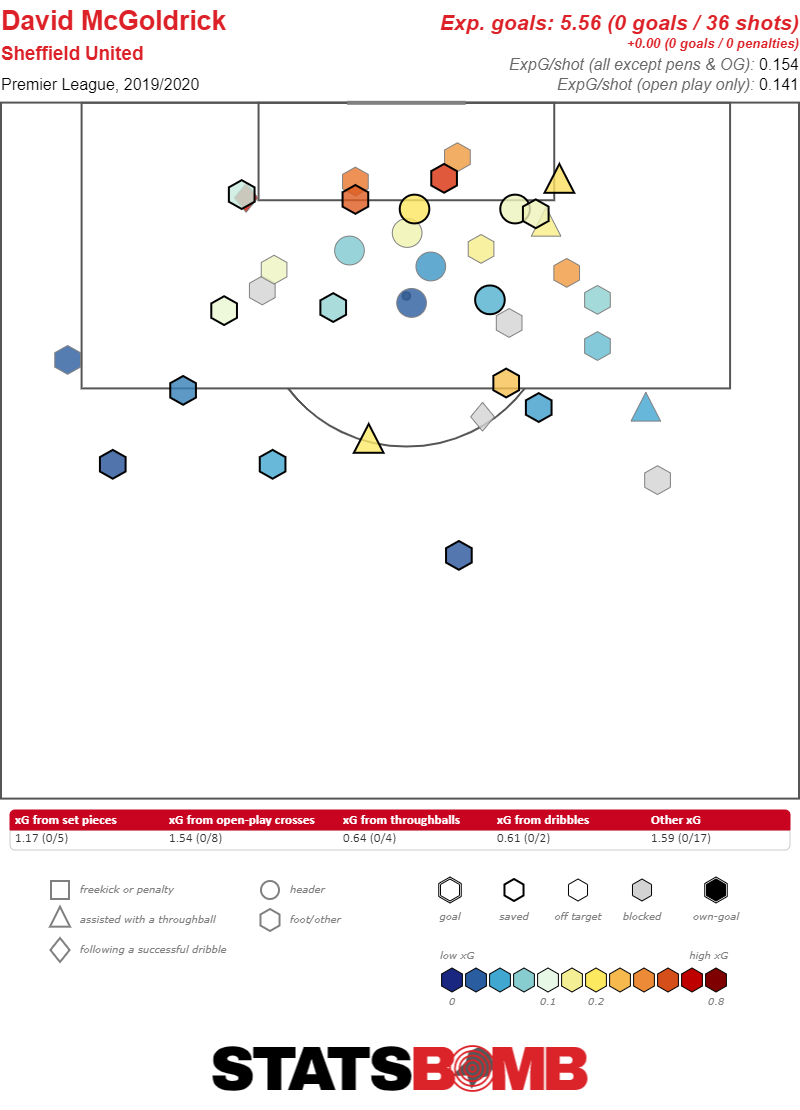

Aaron Wan-Bissaka put in an excellent defensive performance against Manchester City last weekend, locking down Manchester United’s right flank. It’s well known that he makes a lot of tackles, and his possession-adjusted 4.62 per 90 puts him in the top 5 players in the league on this stat. What’s really impressive is that none of the other players near the top of this list have a better ratio of being able to make a tackle instead of getting dribbled past than his 80%. For all the challenges he makes, he rarely gets caught out, and may well be the best tackler in the Premier League.  Dave McGoldrick must be feeling awfully frustrated by now, producing 4.18 xG without yet scoring a goal this season. No player in the league has put up more xG without scoring. It might be time for Sheffield United fans to pray to the finishing gods for things to turn around for McGoldrick.

Dave McGoldrick must be feeling awfully frustrated by now, producing 4.18 xG without yet scoring a goal this season. No player in the league has put up more xG without scoring. It might be time for Sheffield United fans to pray to the finishing gods for things to turn around for McGoldrick.  Header image courtesy of the Press Association

Header image courtesy of the Press Association

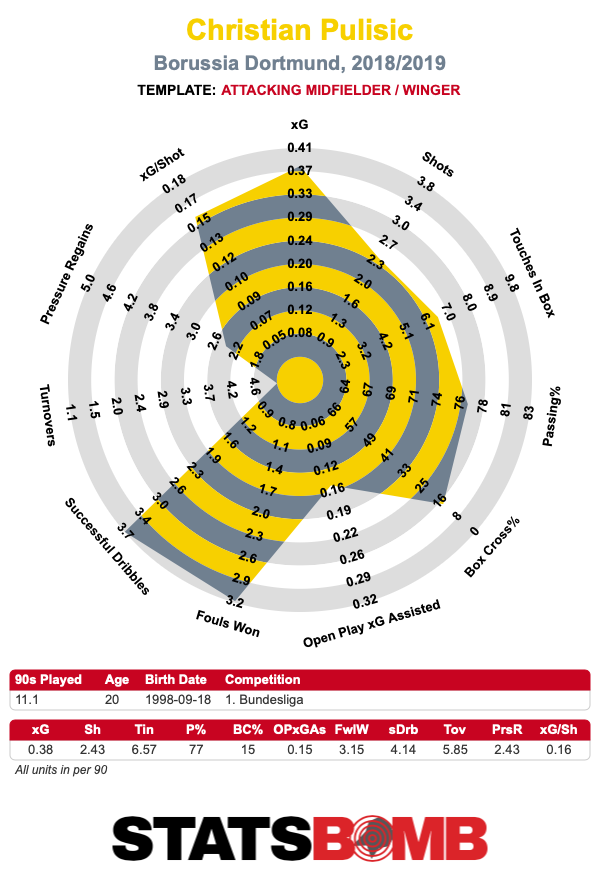

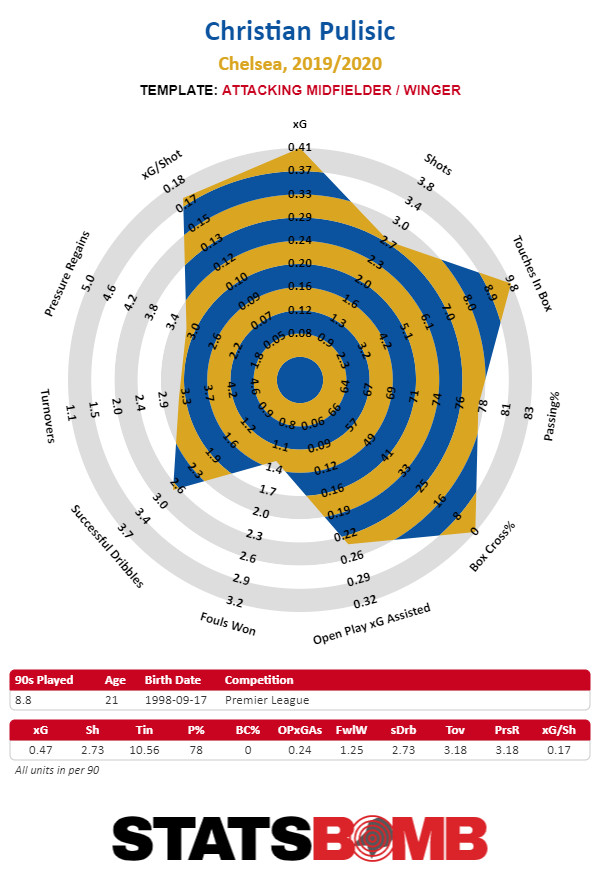

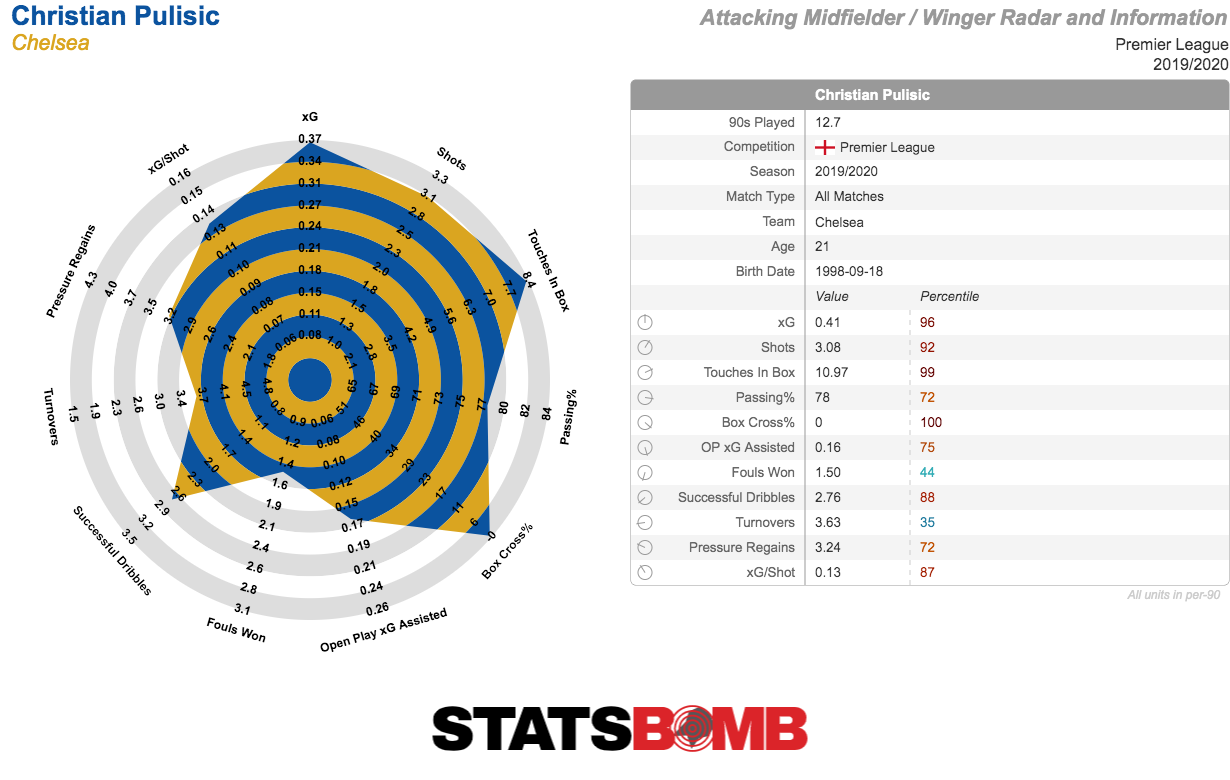

That formed a promising foundation for Pulisic even as he sat on the bench watching Mount and Hudson-Odoi shine. He hadn't shown it yet at Chelsea, but his time at Dortmund clearly suggested Pulisic had the instincts of a prolific goal scorer. And when Pulisic then struck a hat-trick at Burnley, the underlying numbers suggested that he had the ability to keep scoring over a longer spell. And that he has. By now Pulisic has started eight games in a row and scored six goals over the same period. The underlying numbers have improved since his final campaign at Dortmund. His shots per 90, xG per 90, and xG per shot are all up year over year.

That formed a promising foundation for Pulisic even as he sat on the bench watching Mount and Hudson-Odoi shine. He hadn't shown it yet at Chelsea, but his time at Dortmund clearly suggested Pulisic had the instincts of a prolific goal scorer. And when Pulisic then struck a hat-trick at Burnley, the underlying numbers suggested that he had the ability to keep scoring over a longer spell. And that he has. By now Pulisic has started eight games in a row and scored six goals over the same period. The underlying numbers have improved since his final campaign at Dortmund. His shots per 90, xG per 90, and xG per shot are all up year over year.  Part of what makes Pulisic so dangerous is his ability to get into good positions in central areas. His main rival on the left wing, Hudson-Odoi, likes to get the ball out wide before taking on defenders. The graphic below shows the passes Hudson-Odoi has received in the league this season.

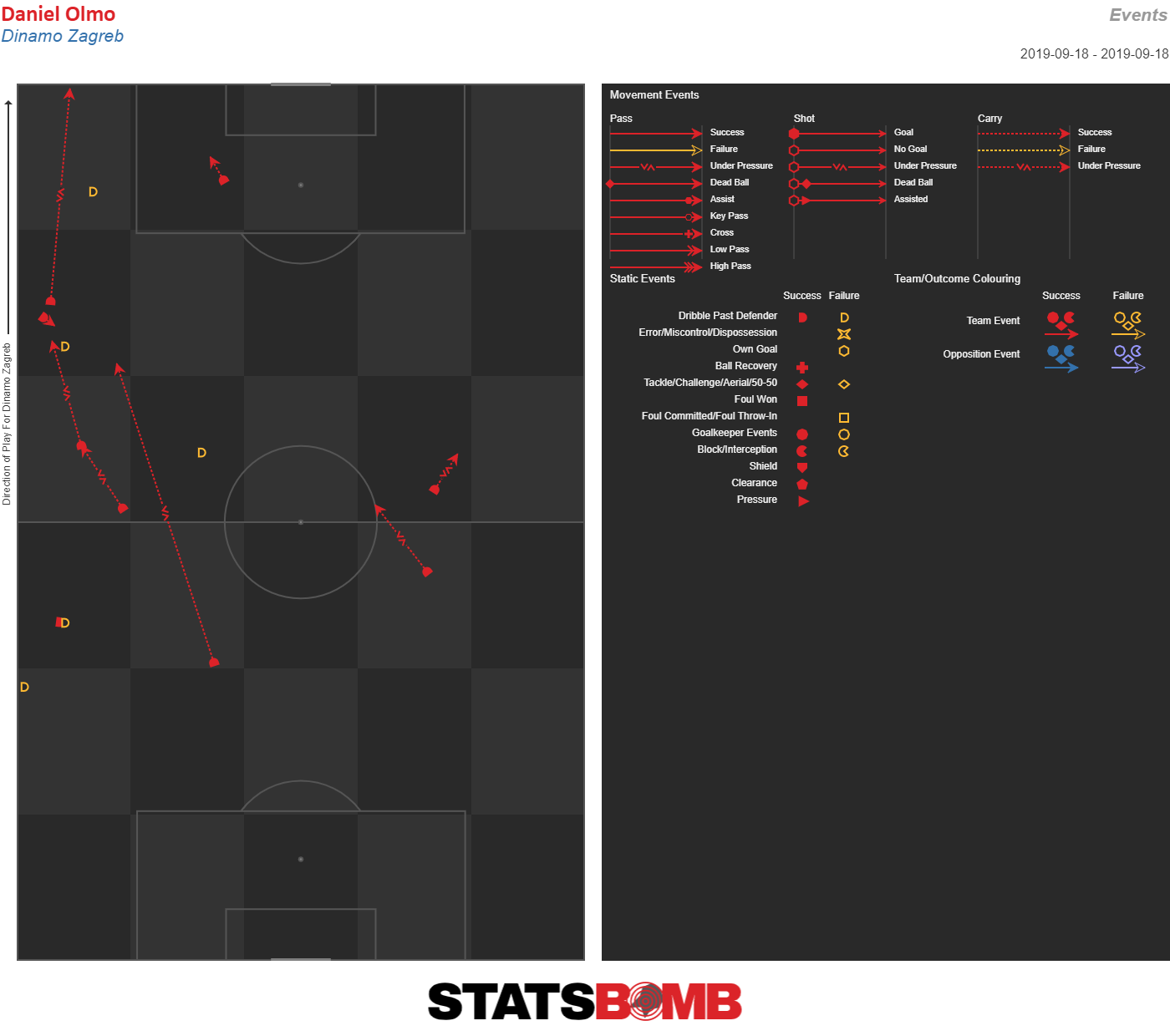

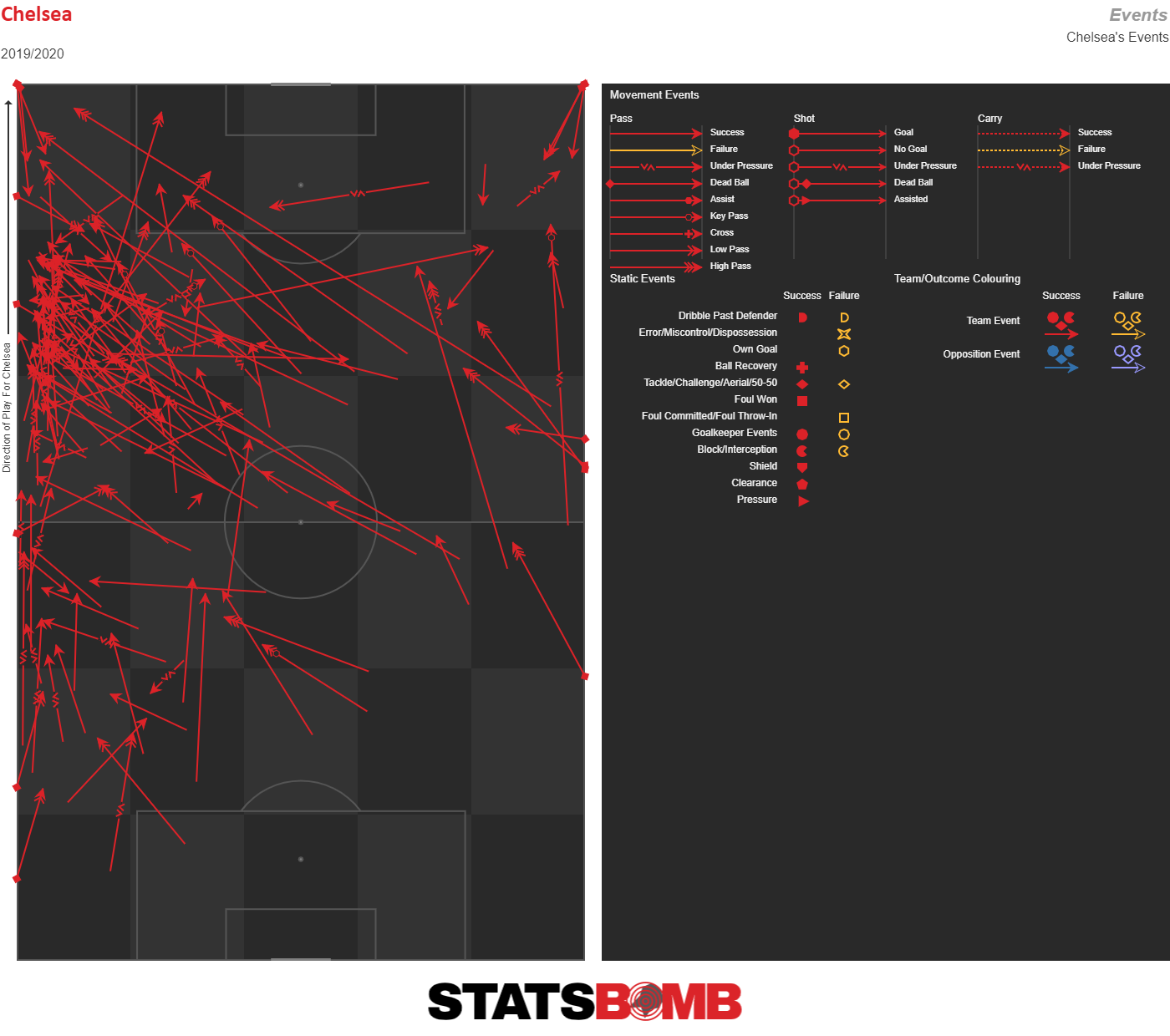

Part of what makes Pulisic so dangerous is his ability to get into good positions in central areas. His main rival on the left wing, Hudson-Odoi, likes to get the ball out wide before taking on defenders. The graphic below shows the passes Hudson-Odoi has received in the league this season.  Pulisic moves in between the lines and into the box far more often. The graphic below shows the passes he has received in his last four league games.

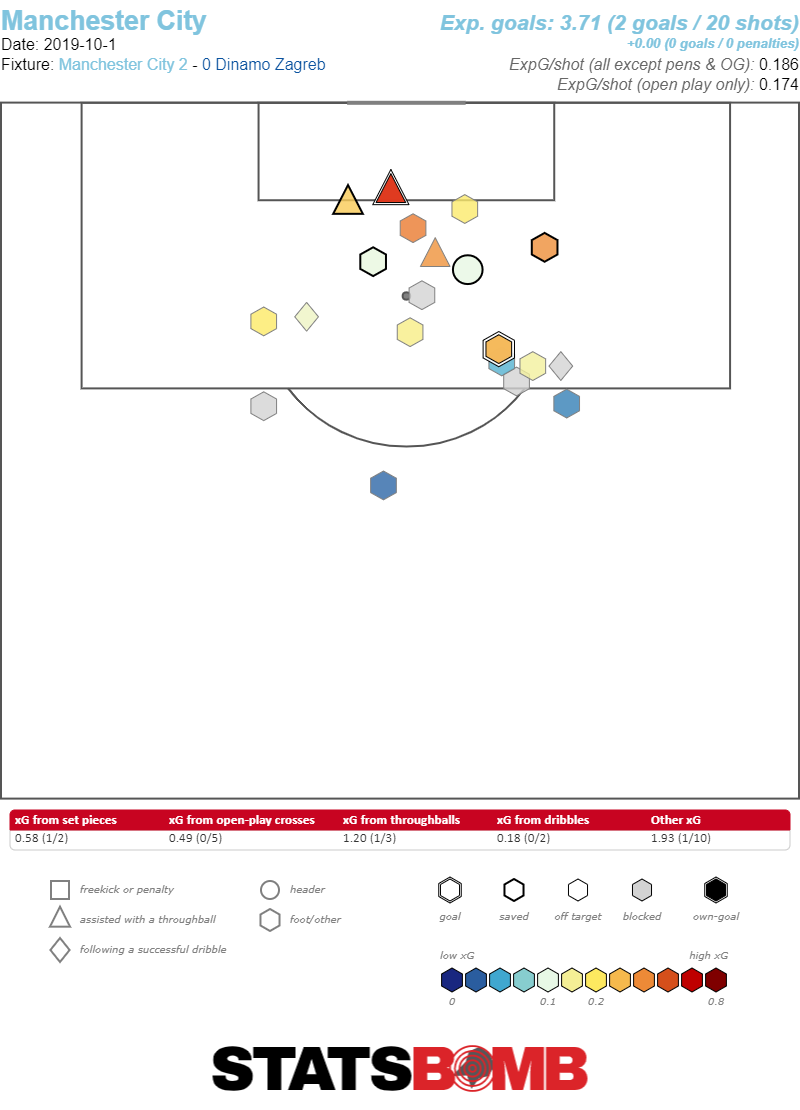

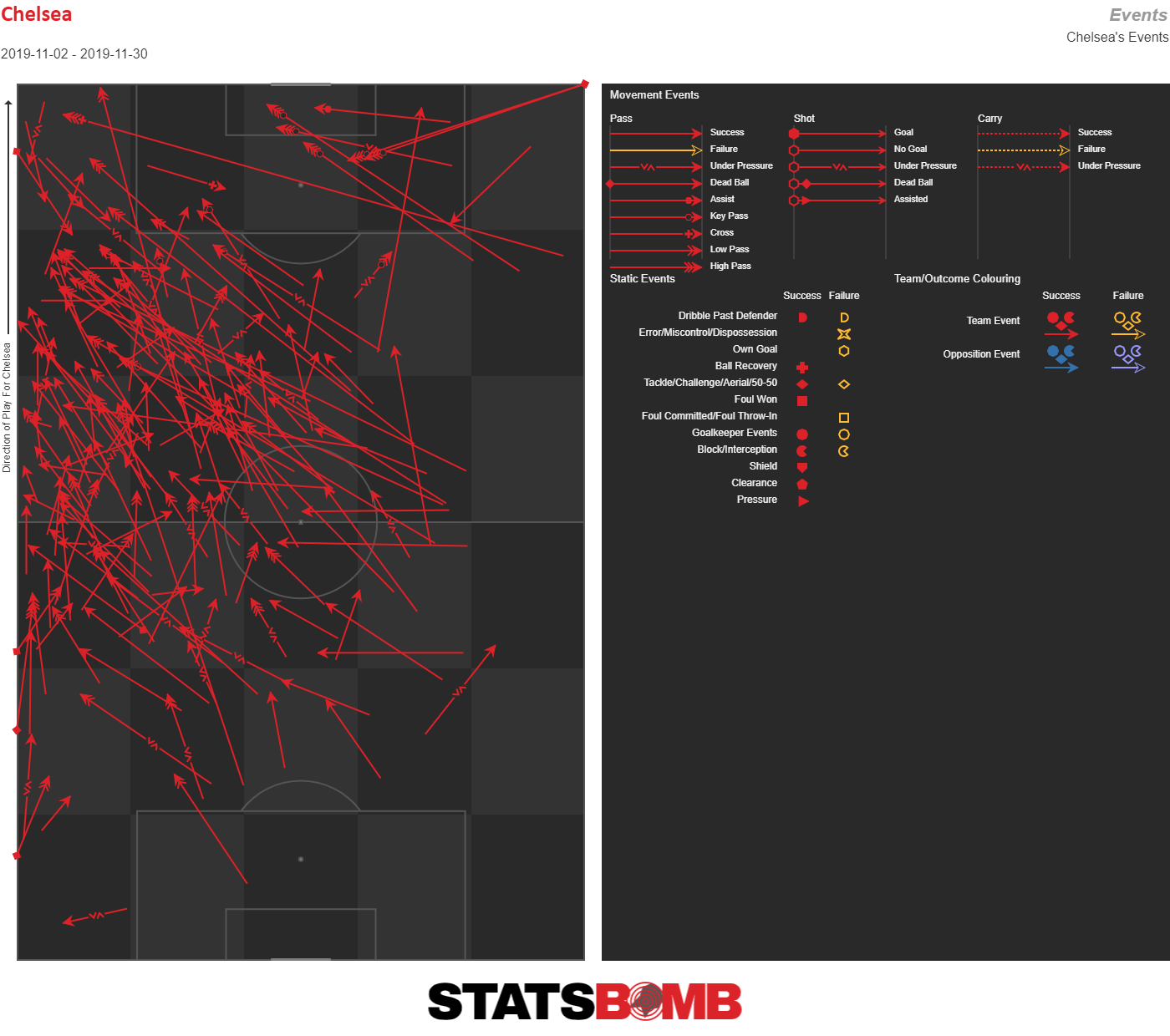

Pulisic moves in between the lines and into the box far more often. The graphic below shows the passes he has received in his last four league games.  Once Pulisic enters the box, his quick feet and sense of anticipation enable him to unleash a series of high-quality shots. Few wingers post shot maps like this one.

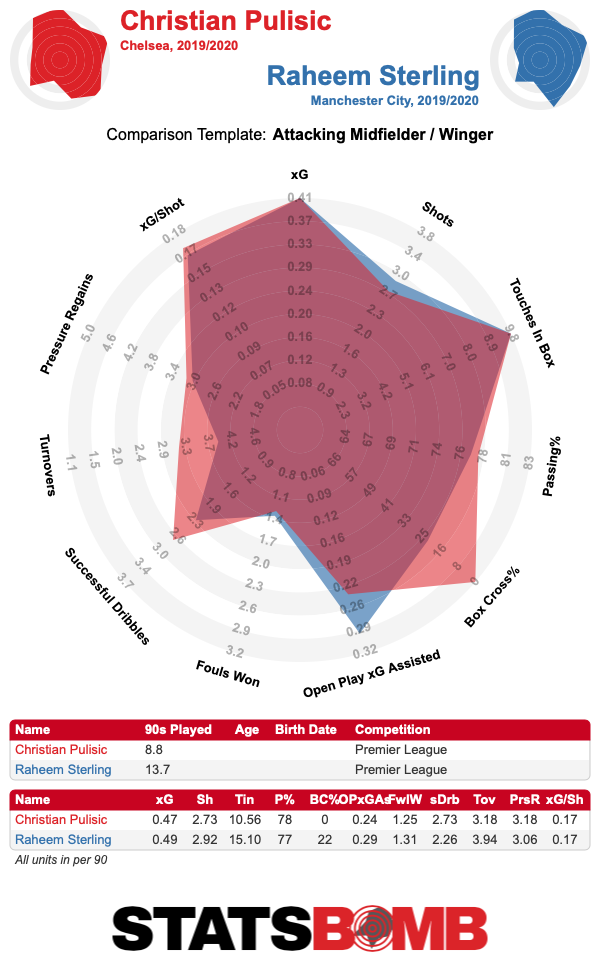

Once Pulisic enters the box, his quick feet and sense of anticipation enable him to unleash a series of high-quality shots. Few wingers post shot maps like this one.  Where do these numbers put Pulisic among the players in the league? Among those who play regularly, he has the sixth-highest open-play xG per 90. The only winger ahead of him is Raheem Sterling. Pulisic is ahead of Mohamed Salah, Sadio Mané, Jamie Vardy, Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang and Son Heung-Min. Pulisic is also sixth in expected assists from open play, with 0.24 per 90. That gives him an expected goal involvement of 0.71 per 90, which is not bad at all for a winger who turned 21 a few months ago. Compare Pulisic with the most productive winger in the league over the last few years and the numbers are actually similar.

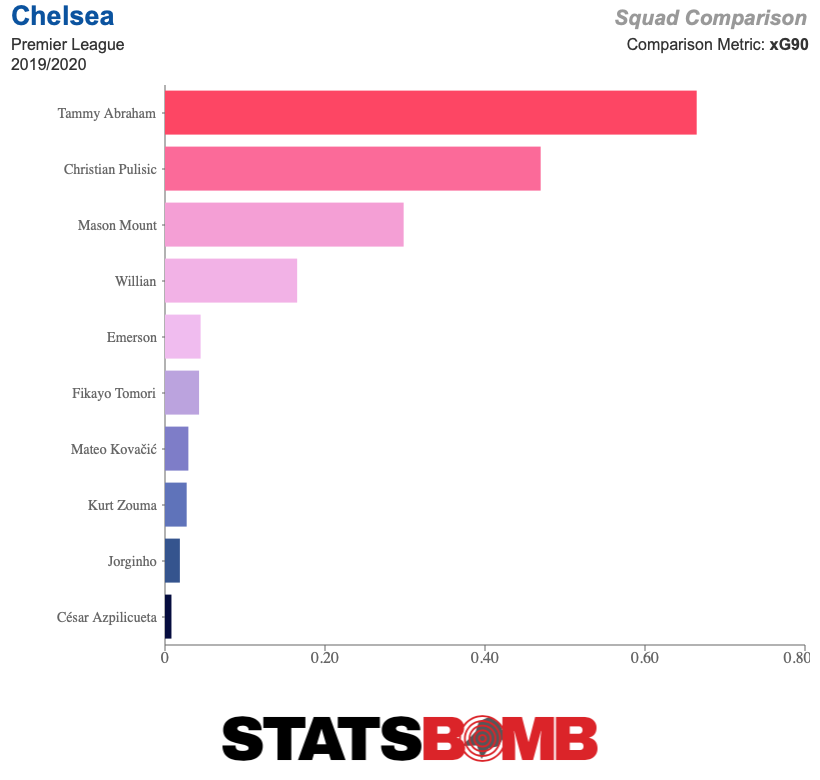

Where do these numbers put Pulisic among the players in the league? Among those who play regularly, he has the sixth-highest open-play xG per 90. The only winger ahead of him is Raheem Sterling. Pulisic is ahead of Mohamed Salah, Sadio Mané, Jamie Vardy, Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang and Son Heung-Min. Pulisic is also sixth in expected assists from open play, with 0.24 per 90. That gives him an expected goal involvement of 0.71 per 90, which is not bad at all for a winger who turned 21 a few months ago. Compare Pulisic with the most productive winger in the league over the last few years and the numbers are actually similar.  Pulisic enjoys a higher status at Chelsea now. He was one of few players who escaped rotation at home to West Ham after the taxing midweek clash at Valencia, and when Chelsea were chasing an equaliser on Saturday, Lampard replaced Olivier Giroud not with Michy Batshuayi, but with Hudson-Odoi, and moved Pulisic up front. He has now said that Pulisic might play as a striker if Tammy Abraham is out for long. If Lampard wants his most dangerous players as close to goal as possible, such a move would make sense.

Pulisic enjoys a higher status at Chelsea now. He was one of few players who escaped rotation at home to West Ham after the taxing midweek clash at Valencia, and when Chelsea were chasing an equaliser on Saturday, Lampard replaced Olivier Giroud not with Michy Batshuayi, but with Hudson-Odoi, and moved Pulisic up front. He has now said that Pulisic might play as a striker if Tammy Abraham is out for long. If Lampard wants his most dangerous players as close to goal as possible, such a move would make sense.  In any case Pulisic will surely not follow De Bruyne and Salah now. His form would need to decline significantly if he is to lose his place in the team, and he shows no signs of that. Whether he’ll ever be as good as those two remains to be seen, but what is certain is that he has continued his development at Dortmund in the Premier League. Having long been considered a player for the future, Pulisic is turning into a star for the present. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

In any case Pulisic will surely not follow De Bruyne and Salah now. His form would need to decline significantly if he is to lose his place in the team, and he shows no signs of that. Whether he’ll ever be as good as those two remains to be seen, but what is certain is that he has continued his development at Dortmund in the Premier League. Having long been considered a player for the future, Pulisic is turning into a star for the present. Header image courtesy of the Press Association