We have a model at StatsBomb we call Passing Ability. You've probably seen the percentile numbers in newer radar charts, and if you want more on the detail work, you'll find it here. It was created by the very talented DOCTOR Marek Kwiatkowski. We use this model in place of passing percentages because as I explain in the link, passing percentages actually tell you very little about whether someone is a good passer. We think this is better, and we use it professionally every day.

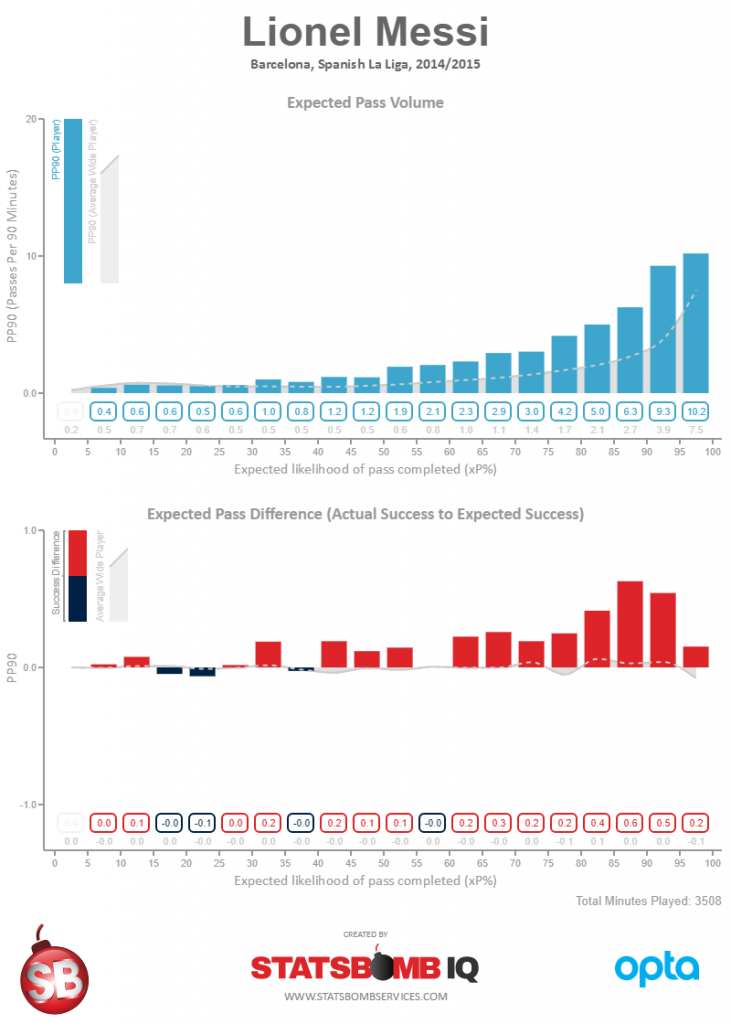

Anyway, many of you probably already believe Lionel Messi is a great passer. His skill in this area is pretty easy to pick up just from the eye test, and from a stats perspective, if you had to say one area that Messi is quantifiably better than CR7, you'd pick his passing. However, when you plug the info into an expected pass completion model, Messi's passing takes on an entirely new dimension.

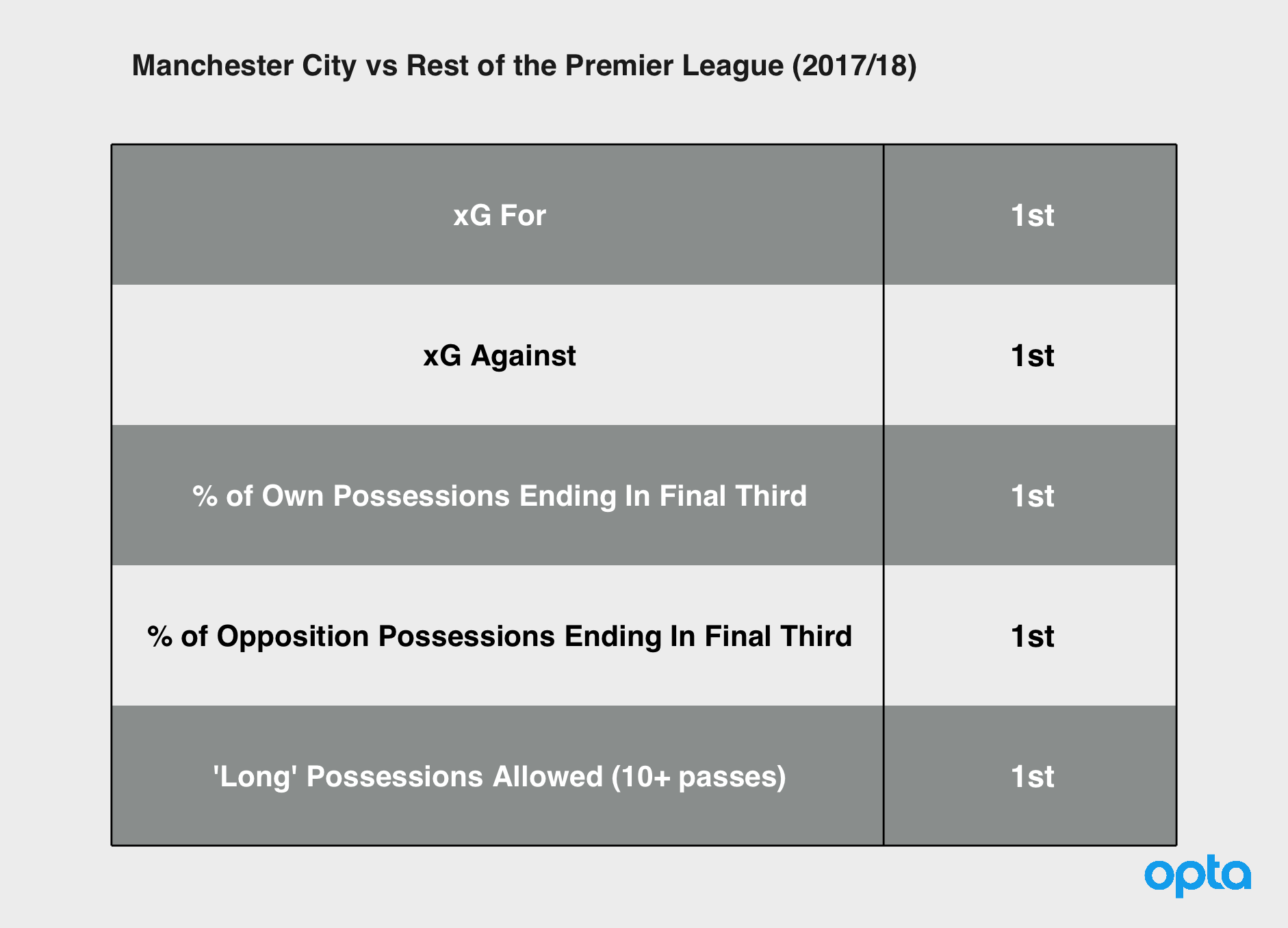

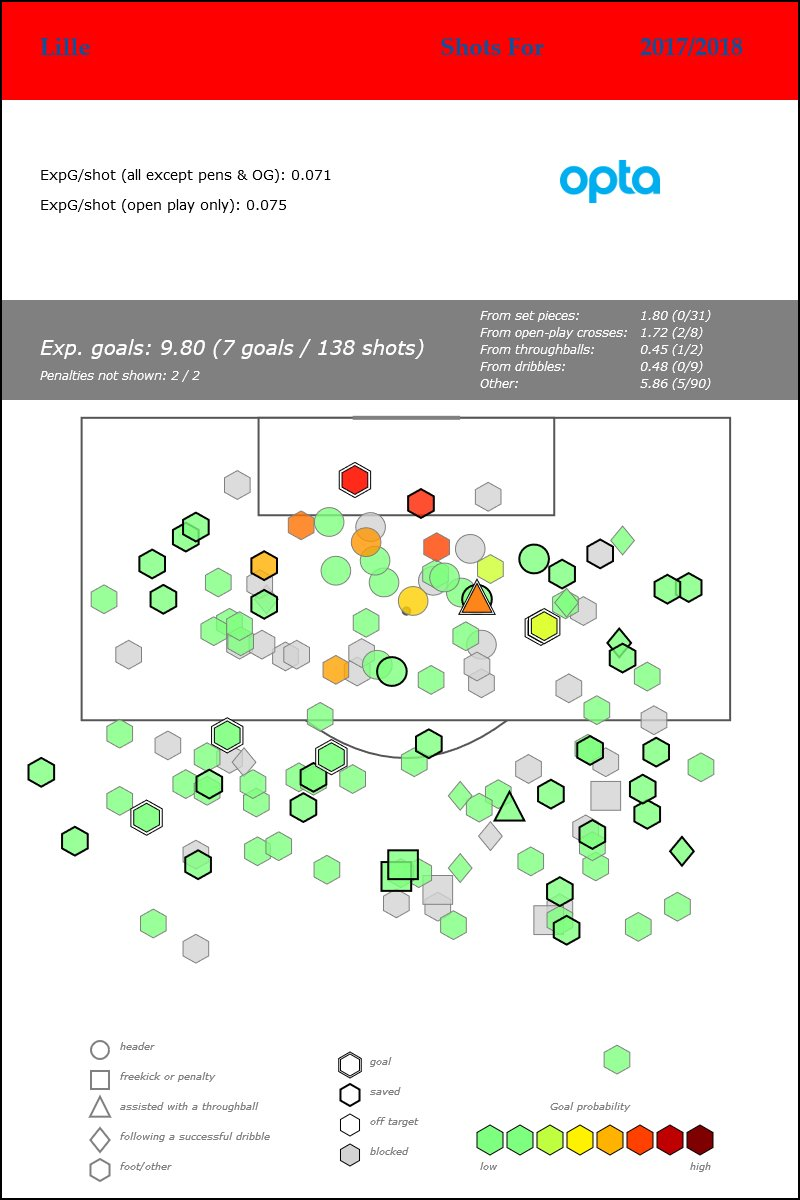

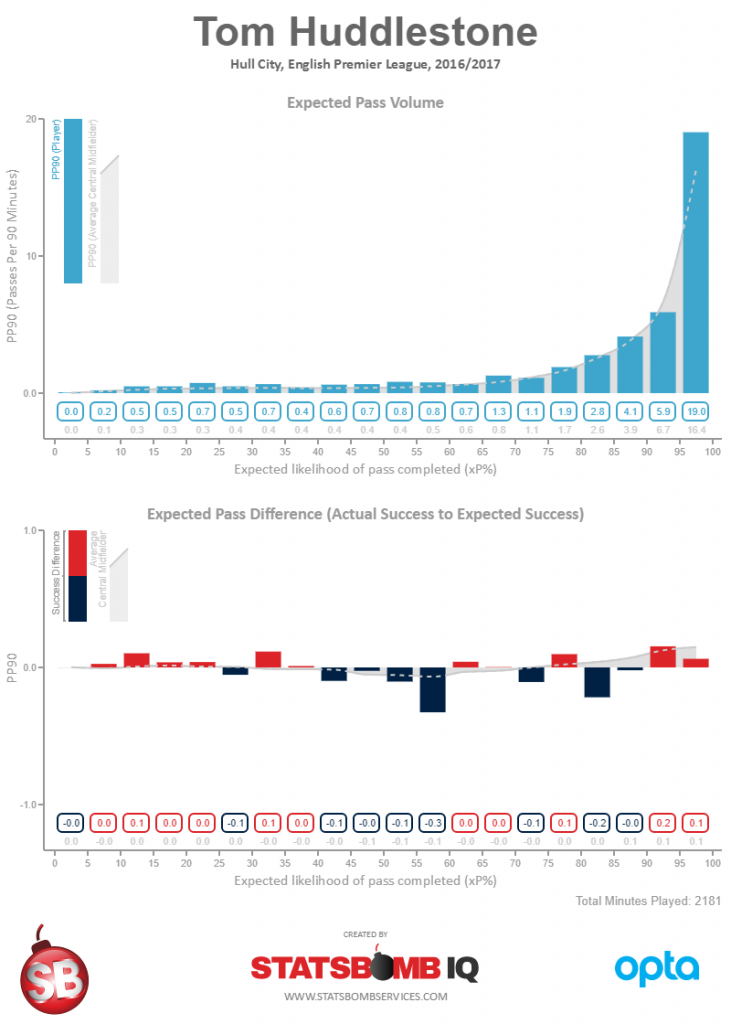

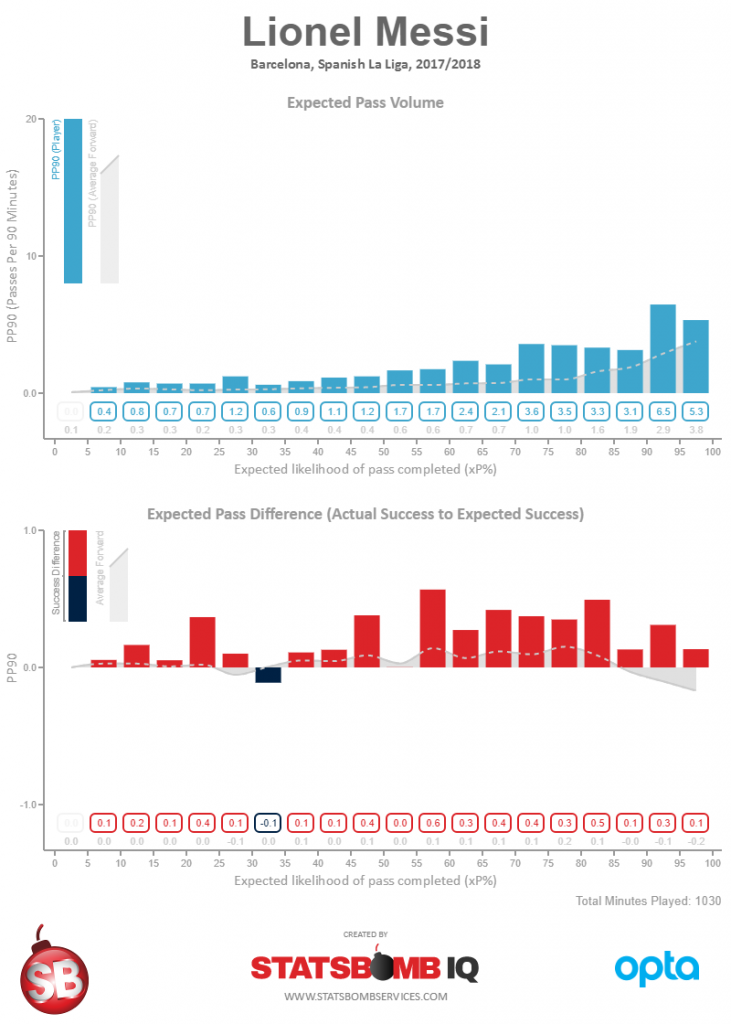

Below is a visualisation we produced to help uncover a little more information about each player's passing and how it's graded by the model. The top set of bars is volume of passes per 90 in each expected passing percentage (xP) bucket. So the bucket to the far right are passes the model expects to be completed between 95 and 100 percent of the time. The grey line is the league average volume for players in his position.

The second set of bars details whether they are performing better or worse than the model expects in each bucket.

Tom Huddlestone is in the 50.9th percentile of all passers in the data set, and as you can see, his completion by bucket ebbs and flows. It's not a perfect model, but in the vast majority of cases it passes the sense test. It thinks Xavi and Toni Kroos and Mesut Ozil and David Silva are awesome and so does everyone else.

Which brings us back to Messi... Messi is awesome in a way almost no one else ever has been or ever will be. The next chart is from Messi's passing output in 2014-15.

Now what you have to remember about Messi is that he's marked more than any other player. He's subject to more double and triple teams around the box. He's bodied constantly. And his teammates are also often marked more heavily than other players in the model, because teams always collapse the box against Barcelona.

The environment he's completing passes in is tougher than what's faced by almost anyone else.

And the model doesn't KNOW...

So the model is out there thinking, "Yeah, this guy is pretty awesome. And not only is he awesome, but he has an insanely high volume of passes for a forward in almost every difficulty range, which is even more impressive. But I have to treat him like all the other students because I am a lowly event data model and can't tell the pressure he's under for every pass... here you go: 99.89 percentile."

But in reality, the degree of difficulty is closer to whatever the Chinese divers always do to obliterate everyone else at the Olympics, and Messi pulls it off just as easily.

This season has arguably been Barcelona's weakest in terms of available weapons. Suarez has struggled. Dembele is injured. Neymar is gone. So it's very much The Lionel Messi Show, and more so than it's ever been. How has Messi's passing graded out this season?

Just when you think you have investigated all of the ways Messi is ridiculous, he finds another way to blow your mind.

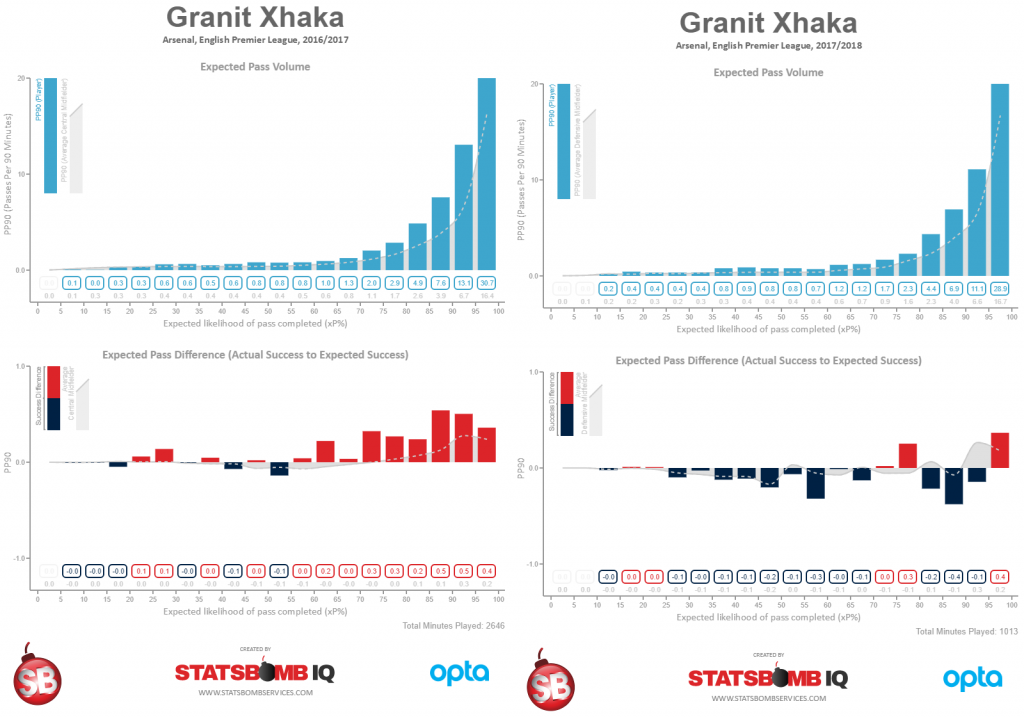

This Was a Bit of a Xhaka

One of the things that's been weird about Arsenal's start to the season isn't the results - the squad is quite good - but Granit Xhaka's drop off in pass completion. He's still completing 83% of his passes, but that's down from nearly 90% last season. Volume is also up slightly to 80 a game vs 72 in league play last year, and Arsenal are winning, so who cares?

This doesn't have to be a big deal. Xhaka could simply be attempting more difficult passes regularly and his passing percentage would go down. I kind of shrugged my shoulders until I pulled up the info from the passing vis and it was unhappy as well.

This is probably a blip. It's early in the season, the volume of passes isn't that high, and maybe teams are playing Xhaka differently on the ball. But it's also something to pay attention to going forward, because this year is different than every other Xhaka season I have data on.

As an analyst in the team, I'd take a close look at this and see if I could figure out why this has happened, because maybe there's a tactical element to it we can solve going forward. Or maybe this is a happy trade-off for a style of play that is bringing us more success, and you're fine with it. Sometimes potential problems are simply something you want to know more about before dismissing.

A Note About Imperfections

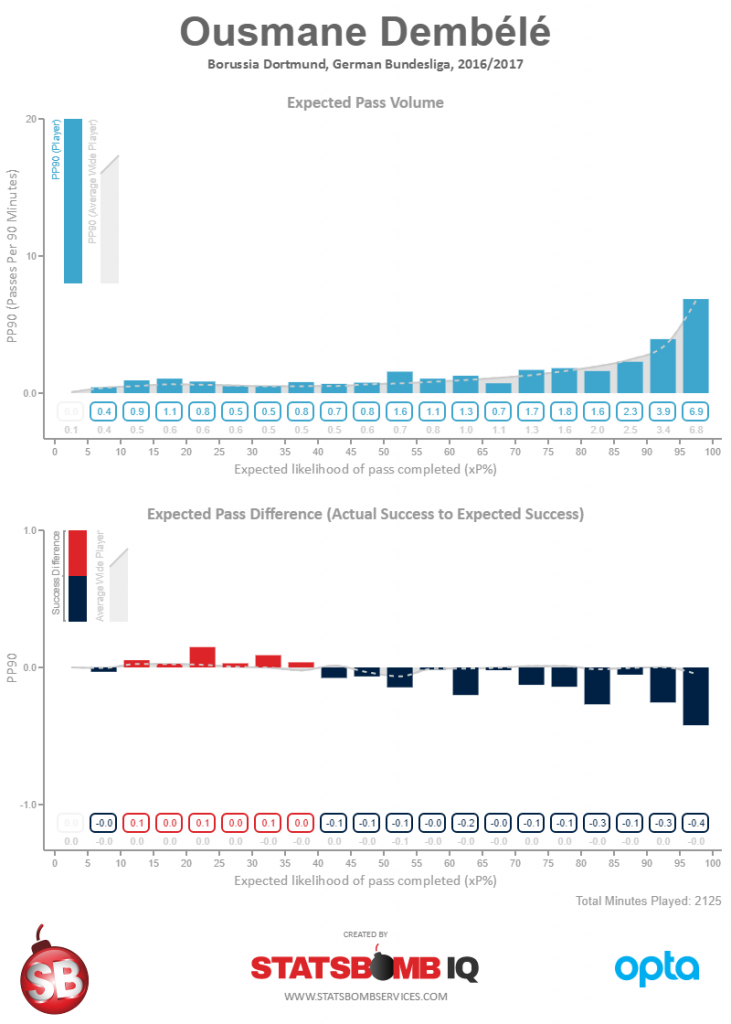

The passing model does not like Ousmane Dembele. It grades him quite low, despite the fact that he's one of the best creative wide players in football. The vis I've been using in this article was built to help explain why this big ass model that uses 20 million open play passes is unimpressed.

As you can see above, it thinks Dembele doesn't complete nearly enough of the "easy" passes. However, it also flags the fact that he's pretty good at completing the hard ones, which are exactly the types of passes that create goals for his teammates.

Now there are options available to "fix" this problem. We could skew the weight of the rating to account for high risk/high reward passers to help boost their numbers. Or, we could scrap the model and start over, attempting to account for this problem, but potentially open up other issues in the process. OR, since we've learned a bit about where the holes are in this current model and we like how it performs almost everywhere else, we can just account for this with human judgement layered over the top of the data algorithm.

Using data in sport is always challenging. A bit like being an athlete on the pitch, nothing you ever do will be perfect. You are typically faced with a series of sub-optimal choices, and have to choose the one that is least wrong. There are valid critiques of almost everything we do, but my response these days is often, "I agree with you, but show me something better." This is exactly why you can't let perfection get in the way of progress, because in a sport with the complexity of football, perfection does not exist.

Except maybe in the case of Lionel Messi.

Ted Knutson ted@statsbombservices.com @mixedknuts