Ever experience that rare moment where you find something, say, a spreadsheet, with information on it you barely recall recording some three months earlier? No? Well, I did. And that information involves a quirky new team and player stat called Final Third Zone Entries.

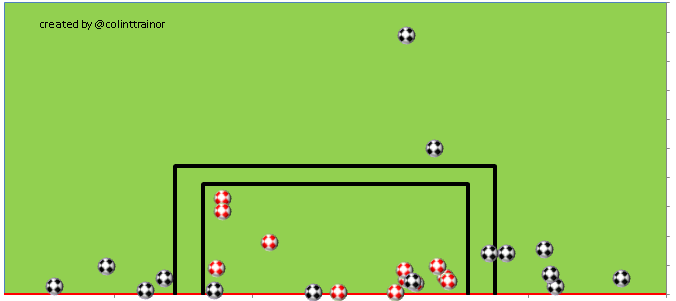

Today's article is going to focus on the Final 1/3rd Zone Entries for 2013 CL final, the method of entry and the outcome of entry.

What Is A Final 1/3rd Zone Entry?

A controlled entry into the final 1/3rd of the pitch, which is where all the magic happens. EPL Index is a popular stats site that houses all kinds of numbers on final third actions - passing%, pass volume, turnovers - and we know virtually every shot is attempted from the final 1/3rd of the pitch, so we then take a step back. What did the attacking team do to get deep into opposition territory? Was it a long pass, a carry, a short pass? Over a large sample, do any of these methods result in a higher number of shots?

Why Is It Important?

The ability to gain entry into the final 1/3rd leads to possession around the opponents 18 yard box, this possession leads to shots and goals and wins. A team really needs to have some ability to gain entry into the final 1/3rd in a controlled manner. A team could try the direct Stoke method of 'chance' balls into the box, this may method be necessary if a team has a sub-par midfield, but it is surely better to have control of the football whilst entering the oppositions territory.

What Are The Methods Of Final 1/3rd Entry?

There's a few: Carry (dribble), Turnover and passes of the long, medium and short variety. If a throw-in was used to gain the final 1/3rd (rare) then it is grouped as a pass.

Can These Methods Of Entry Tell Us Anything About Tactics?

It's early doors for Zone Entries, but if I had a Stoke Season ticket pointed to my head I'd say lots of short passes are generally a sign of a slow build-up/possession heavy teams.

Long passes could be the sign of a long ball team, or as with medium passes, it could be a sign of a good counter attacking tactics.

Carrying the ball into the zone is either due to outstanding skill when faced with a set defense, but it's more likely to be down to quick, skilled forwards launching full or partial counter attacks.

Turnovers are pretty important. The attacking team regains possession in the crucial final 1/3rd and the oppositions defense is likely not in a correct defensive position.

Are There Any Examples Of Previous Zone Entry Work?

Yes, Danny looked at zone entries first (link) and I looked at them for Man City (link) and Spain (link). I'm almost done with setting up a framework for recording Zone Entries, and it is something Danny and I will be recording for every Man City game next season. It's also come to light that a regular of StatsBomb has been recording their own Zone data for the MLS. Guess who?!

That recording of data should, hopefully, yield some cool info on teams' preferred method of entry and give us a baseline success rate of each type of entry. We will also find out who is 'driving the bus', as the 'Mericans say. A single season should give us an N of ~3700 to 3900 zone entries. It'll probably tell us some cool things about team tactics and how teams behave at certain game states.

Let's get started on the Champions League Final

Zone Entries

| Team | Carry | Turnover | Long Pass | Med Pass | Short Pass | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dortmund | 12 | 3 | 9 | 11 | 6 | 41 |

| Bayern | 7 | 6 | 13 | 15 | 6 | 47 |

This is the basic data. I would normally post the success and failure rate of each entry, but for clarity I will only post succesful entries today.

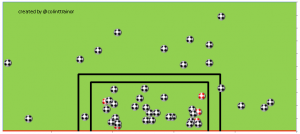

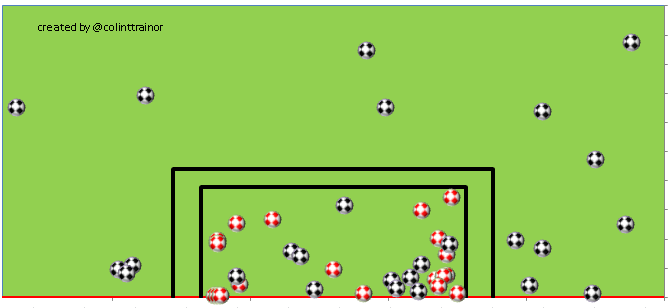

The method of controlled entries varies for each team. Bayern seemed to employ a quick and direct tactic against Dortmund which relied upon medium to long passes to spring Robben and Ribery on counter attacking raids. Bayern also had more success in turning the ball over in the final third, which usually causes havoc but, strangely, that wasn't the case for Bayern in this CL final.

Dortmund recorded fewer overall entries, turned the ball over on fewer occasions than Bayern did and carried the ball into the final third on more occasions than the opposition. One Dortmund player was driving that ball carrying controlled entry number. More on that later.

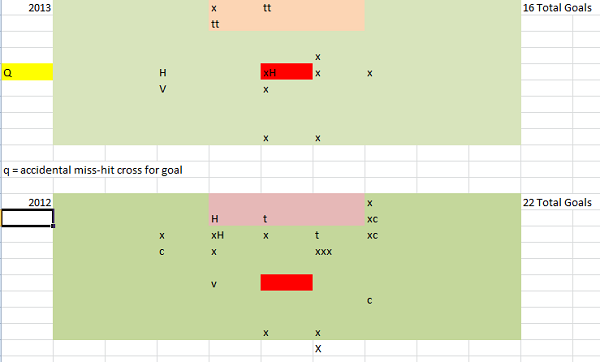

First Half, Second Half, Final 30 Minutes

| Carry | Turnover | Long Pass | Med Pass | Short Pass | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Half | ||||||

| Dortmund | 4 | 2 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 23 |

| Bayern | 1 | 2 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 19 |

| 2nd Half | ||||||

| Dortmund | 8 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 18 |

| Bayern | 6 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 28 |

| Last ½ an Hour | ||||||

| Dortmund | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 11 |

| Bayern | 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 16 |

Here we break the entries down into halves and final 30 minute segments.

First Half

It was Dortmund who came out quicker, passed the ball with more purpose and enjoyed the early territory advantage. This showed in their final third zone entry numbers. Dortmund edged Bayern in the first half and did so with more short passes and carries into the zone.

Second Half

It wasn't even close, Dortmund continued to rely on carrying the ball into the zone on counter attacks and using a mixed passing strategy. Bayern, in that second half, were by far the better team with 10 more controlled zone entries and Bayern achieved this using every method available: carries, turnovers and a mixed passing strategy.

Watching the game back, Dortmund definitely seemed to flag and run out of ideas in that second half.

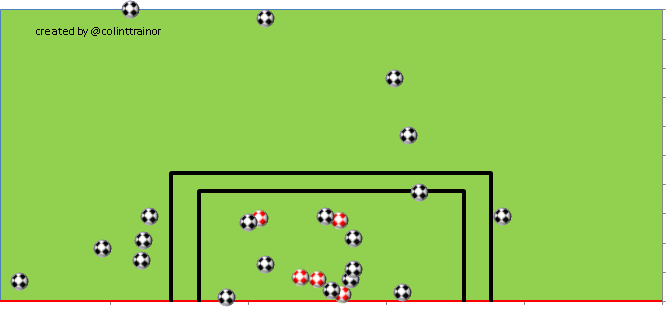

Final 30 Minutes saw 3 goals scored, but really it was about what happened after Bayern scored their opener: They played long and medium passes, carried the ball fewer times (less risk) and employed a pretty good defensive system, even after conceding an equalizer, that, when added to Dortmund's struggles, led to just 7 final third entries against in the last 26 minutes.

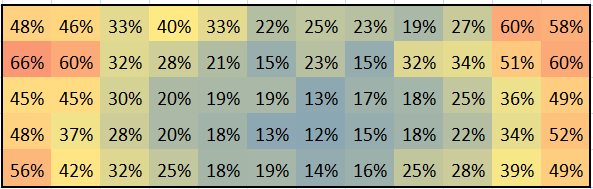

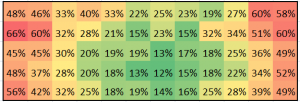

Frequency Of Zone Entries

Dortmund went off great guns at the start of both halves but the inability of Dortmund to gain entry in Bayern's defensive end in the last 15 minutes was telling. Bayern started slowly, got better, improved even more in the second half and took control of the game accoriding to the entry count in the crucial last 15 minutes of the game.

Zone Entry And Outcome

This next section features the method of entry and the outcome of that method.

| Dortmund | Back Out | Shot | Tackled | Giveaway |

| Carry | 4 | 6 | 2 | |

| Turnover | 1 | 2 | ||

| Long Pass | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Medium Pass | 5 | 3 | 3 | |

| Short Pass | 2 | 1 | 3 |

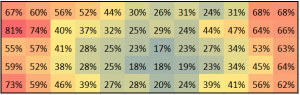

For Dortmund, carrying the ball into the final third was a high risk/high reward tactic. It generated shots but it led to losing the ball often. Medium length passes was Dortmund's best shot generating tactic. A medium pass, and to some extent, carries, are probably signs of quick attacks.

| Bayern | Back Out | Shot | Tackled | Giveaway |

| Carry | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Turnover | 2 | 4 | ||

| Long Pass | 8 | 4 | 3 | |

| Medium Pass | 6 | 2 | 9 | |

| Short Pass | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

Bayern's outcome chart is a lot different to Dortmunds. Just look at the shots generated from long ball passes (mostly center back passes) and medium passes. Both teams generated a lot of shots from medium passes (10-25 yarders) but whereas DOrtmund were able to generate shots from medium passes into the final third, Bayern generated shots by using long balls to Robben, Mandzukic and Ribery. Different tactics.

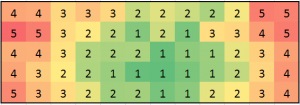

Player Zone Entries

A list of the players, the number of entries created, the method and how many shots each players zone entry created. In descending order:

| Entries | Carry | Short Pass | Medium Pass | Long Pass | Shots | |

| Reus | 9 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Ribery | 7 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Gundogan | 7 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

| Turnovers | 6 | 0 | ||||

| Robben | 6 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | |

| Boateng | 5 | 5 | 3 | |||

| Schweinsteiger | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Lahm | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| hummels | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Piszczek | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Blaszczykowski | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Martinez | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Dante | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Muller | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Alaba | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Turnovers | 3 | 1 | ||||

| Mandzukic | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Subotic | 2 | 2 | 0 | |||

| Bender | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Grosskreutz | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Weidenfeller | 2 | 2 | 0 | |||

| Lewandowski | 1 | 1 | 1 |

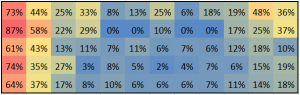

I have a long standing admiration for Reus. And frankly, Dortmund relied heavily on Reus's dribbling and passing to gain the final third zone. Gundogan's dream like passing was as important as it was impressive. These two players accounted for 39% of all Dortmund entries in the game.

Hummels, strangely, is Dortmund's 3rd ranked player and Dortmund's right sided players, aided by an early second half burst, accounted for 8 zone entries.

It was a different story for Bayern. who had four players contribute 5 or more zone entries. Bayern also turned the ball over on 6 occasions which is mighty impressive, but managed zero shots from turnovers which is, well, as unimpressive as it is strange.

Final Thoughts

Final Third Zone Entries are, in my opinion, pretty important. If a team can not gain entry into the heart of the opoositions territory with a modicum of control then how can it be expected to register shots at goal, score or even win games?

I'm only guessing here, but over a large sample, the team with a higher number of controlled final third entries will likely be the teams who outshot their opponents. And what does out-shooting your opponents usually lead to? More points.

As for this specific game and it's data, it's clear that the teams had different tactical set-up's with Bayern relying on long and direct passes and Dortmund utilizing Reus' dribbling ability and Gundogan's balanced passing to gain the final third.

The frequency of final third entries is really interesting: Dortmund went off early and dominated the count for a huge portion of the game, but Bayern tactics, or Dortmund's fatigue, were important.

Bayern, ever so slowly, began to gain Dortmund's zone which led to more shots and more pressure and in the last 15 minutes of the 2013 CL final, it was Bayern who were getting into the final third zone with more frequency, it was Bayern who were shooting more.

Finally, in the 89th minute, a long pass from Boateng (one of five long passes) enabled Bayern to gain controlled entry in the final third and from there, a twist, a turn and a toe-poke was all it took for Robben and Bayern to score the game winner.

Our eyes told us Dortmund were the better and more threatening team in the first half. Our eyes told us Bayern took hold of this game in the second half. The final third zone data tells us the same thing, but it tells us the about how (method) each team created it's shots, the frequency of that creation and the players who were driving the play in terms of controlled entry into the final third zone.