Rebuilding a Premier League squad isn’t easy, especially when the memories of achieving such great heights are still so fresh, as it was for Leicester City with their Premier League title win in 2016. One of the dangers that Leicester faced was that because of the extraordinary feat that they accomplished, it would be hard to exist as a normal PL club afterwards. The next couple of years were filled with shaky transfers and the slow disassembling of their title winning squad, all the while there was the gradual accumulation of young talent that was sorely needed.

As we approach the end of the 2018-19 season, and with the growing pains that have occurred, Leicester have finally moved onto a new era and remodeled their squad in a way that’s more optimum for a club outside the big six. They’ve assembled a collection of young talent that not only ranks favorably with the non traditional powers in the PL, but also within some of the big players higher up the table. Players like Harvey Barnes, Wilfred Ndidi, Kelechi Ihenacho, Çağlar Söyüncü, Ben Chilwell are young and thread the needle between providing solid current value and still having future upside. A major reason why it’s smart to load up on young talent as a mid-table PL club is that any opportunities to break into the top tier will likely come through one of the young talents breaking out and becoming a star. Having more tickets to the lottery is a better strategy for upward mobility as a smaller club.

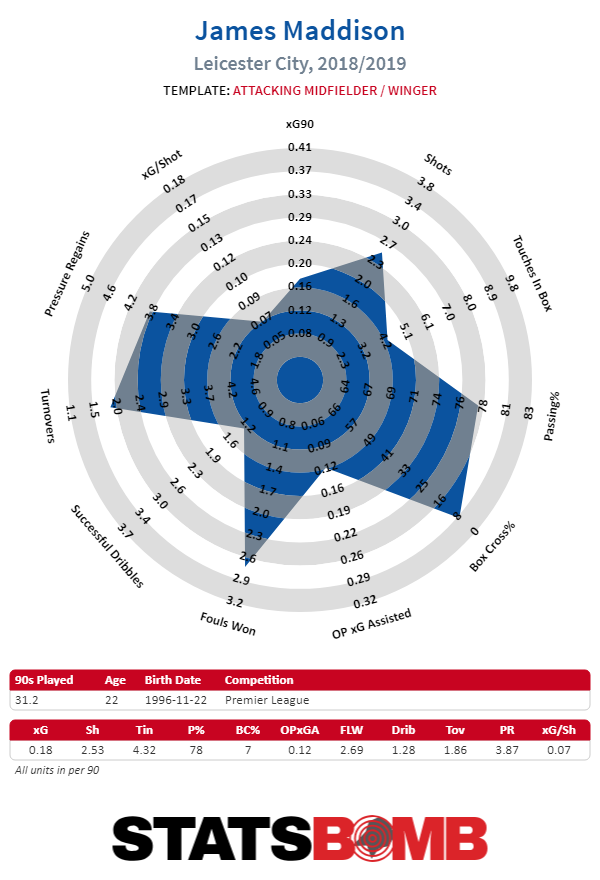

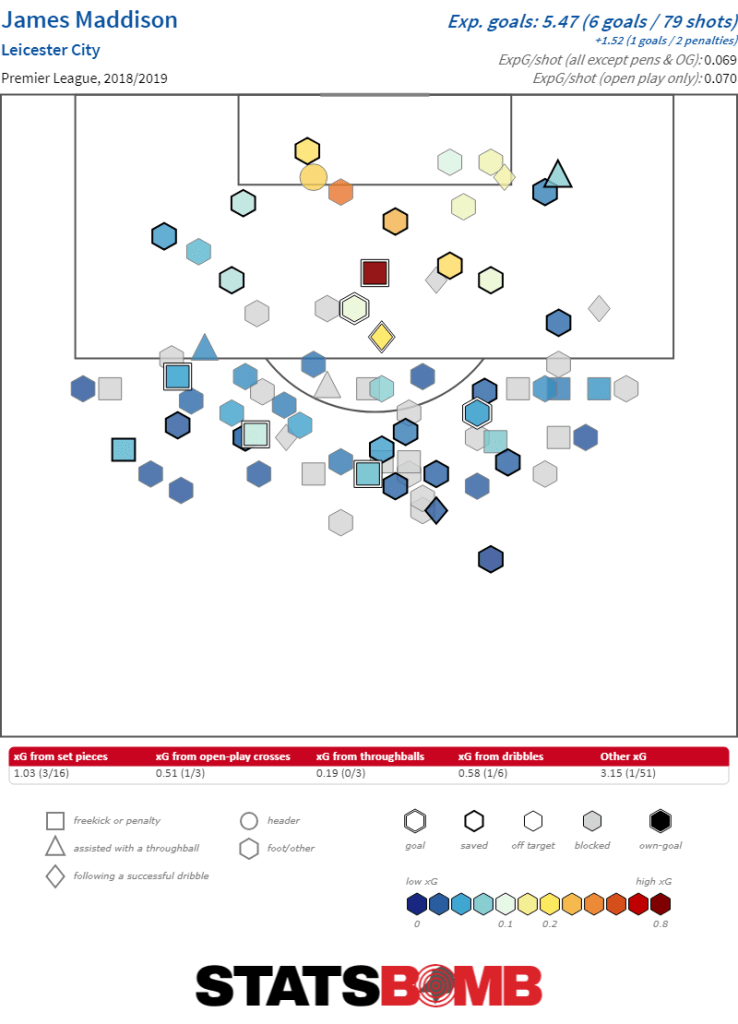

The headliner of those young talents is James Maddison, who’s transitioned quite seamlessly from the Championship. Maddison didn’t come cheap, with his fee in the region of £22m, but it looked a sensible deal given that he was one of the best players in the Championship last season. It was easy to see the appeal with Maddison coming in: he was a high volume shot contributor as a central midfielder for both himself and teammates at Norwich along with being a capable passer, and that player archetype is something that Leicester have not had over the past few years. For the most part he’s been as advertised, which is an encouraging return on Leicester's investment.

Maddison's role with Leicester has changed as the season has progressed. Under Claude Puel, Maddison played more like a traditional #10, playing high up the pitch and constantly hunting for space between the opposition midfield and defensive lines to receive passes. He would maneuver himself to be able to progress the ball upon receiving. If buildup was done properly, the defense would either put emphasis on his positioning and open space elsewhere, or Maddison would free himself in dangerous areas towards the final third. This was largely effective for Maddison, though there were times where there was a disconnect between his positioning and the double pivot behind him.

When Brendan Rodgers took over in late February he changed Maddison’s role. While you still see plenty of moments where he functions like a #10, you’re also seeing him more often collect the ball from deeper areas and trying to dictate play during buildup through recycling possession. Under Rodgers, Leicester have more often used a midfield three featuring Maddison, Ndidi, and Youri Tielemans. Of the three, Maddison has the most free rein to change his positioning depending on the situation.

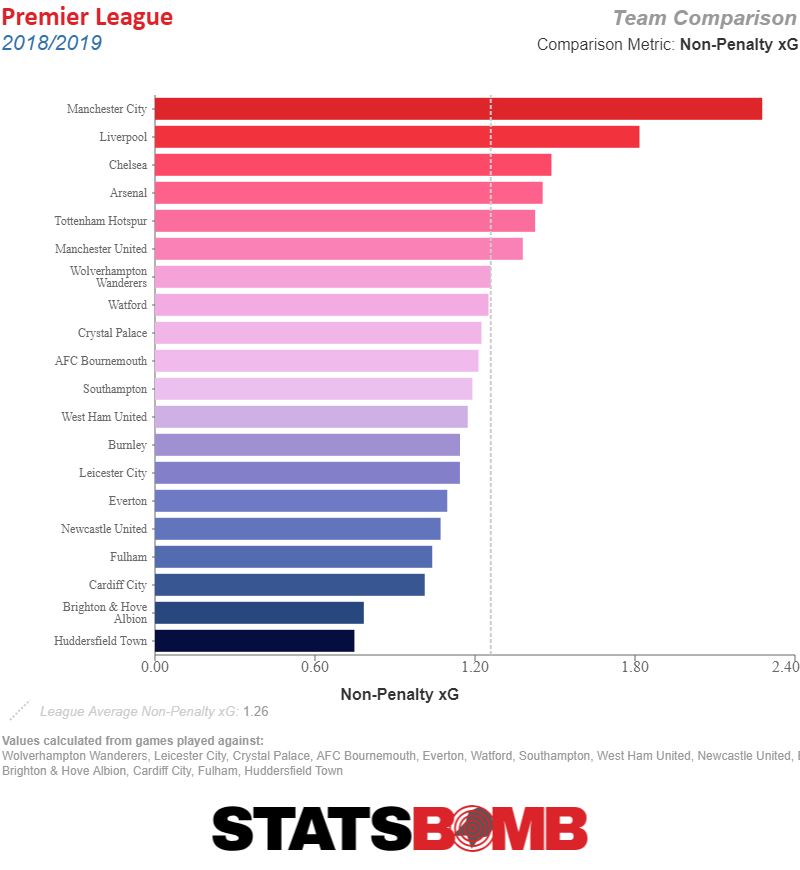

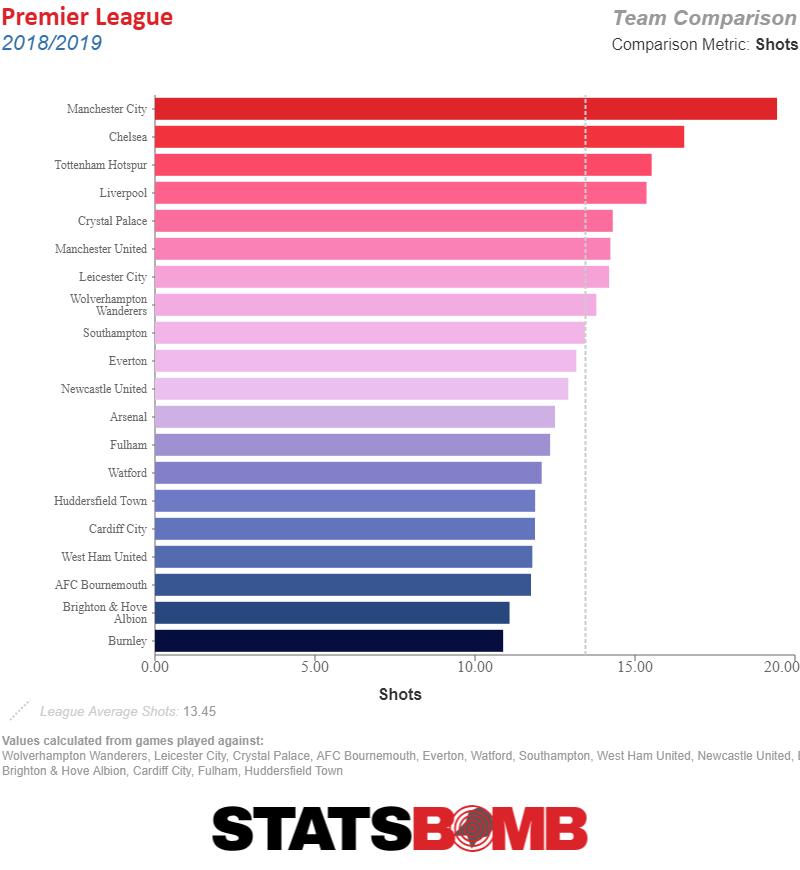

On a team level, the early returns under Rodgers have been promising, though it's important to note that Leicester have played seven out of their eight Premier League matches with Rodgers at the helm against clubs outside the big six.

In this role as a free roaming central midfielder, a lot of what makes Maddison an intriguing player is still on display but in slightly deeper areas. He's just constantly on his toes trying to get himself into open space for teammates to get him the ball. Whether it be moving a couple of yards diagonally to be between two opposition players, or making in-out cuts on the blindside of his marker to lose him, he's got a lot of tricks in the bag. Because of how much he's on the move, there'll be times where he's open for a couple of seconds but he doesn't receive the ball in the middle third. As a result, it's not uncommon to see Maddison visibly show frustration when this happens.

Upon receiving the ball, Maddison does a very good job of maintaining balance if he's pressured by the opponent. Maddison isn't a physically imposing midfielder, he has more of a wiry frame, but he is able to use a quick burst to get the initial step on his opponent, and from there position his body so that all his marker can do is pull him down to draw fouls. This can be seen in Maddison's near elite rate in drawing fouls, making up for his own individual dribbling numbers not necessarily standing out.

This play is illustrative of the multitude of skills that Maddison has in his locker. As he retreats back to help with buildup, the littlest of sidesteps helps confuse his marker and create enough space for a passing angle. When he's about to receive the pass, he opens his body positioning so that once the ball is played to him from the CB, he's able to immediately move forward in one motion instead of turning beforehand. With the littlest of bursts, he gets initial separation from his opponent and baits him to committing a foul by being in front of him and leveraging the threat of leaving him in the dust.

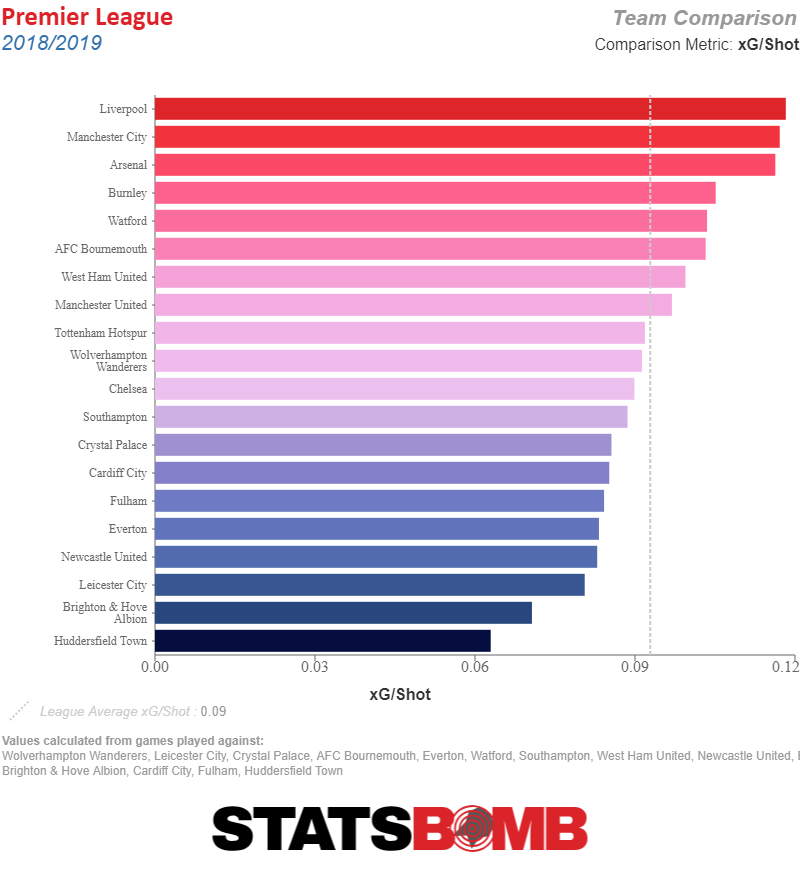

Given his intelligent positioning, ball progression into the final third and overall chance creation (in addition to everything else Maddison adds value with set piece creation) along with the ability to sporadically produce individual moments of ball carrying, the Ndidi/Maddison/Tielemans midfield has been quite harmonious in the limited sample size. Ndidi handles the brunt of the defensive work, while Maddison and Tielemans are positioned in the halfspaces, tasked with unlocking defenses. Maddison's move to a deeper role hasn't had an effect on his individual shot volume, as he's taken more shots under Rodgers than Puel, 2.86 per 90 minutes as opposed to 2.41. His positional change has meant that he's been starting his runs from deeper, being able to sneakily get into the edge of the box for shooting opportunities. It's not the most optimal marriage of shot volume and location, but you'll live with it given what else Maddison brings.

The most encouraging thing that can be said about James Maddison's debut season at Leicester is that he's largely been the same player that he was at Norwich, which is impressive given the jump up in league quality. His positioning and ability to interpret space is arguably his greatest strength, constantly hunting for openings within the opposition. His ability to pass into tight windows in the middle third has been solid, along with his capacity to either be the initiator of combination plays or act as the link-man. I'm interested to see if under Rodgers, his open play expected goal assisted rate increases next season given that he already ranks in the top three among Leicester players in either open play key passes or passes into the box. Maddison's skillset is quite favorable to a permanet switch to the free roaming eight role, though there are the concerns with potential injuries because he gets kicked around a lot.

Next season will be fascinating for both Maddison individually and Leicester as a whole. With a smart transfer window (which should include keeping Tielemans on a permanent basis), Leicester should have a squad capable of contending for a top six spot if one or two of the giants has an off season, and it's not entirely unreasonable to think that could happen. Manchester United and Chelsea are facing turbulent near futures for different reasons, while Arsenal have the unenviable task of having to massively retool an aging squad on limited funds. The door is ever so slightly open for some upward mobility by non-big six clubs, and for Leicester to take advantage, one or two of their young talents has to make the leap. Maddison is a good candidate given that he's already got the rough outlines of an very good-perhaps-even-great center midfielder, and the limited sample size has been promising. If Maddison could even slightly increase his xG contribution in open play, not only will that take him to a higher level as a player, but it could be the jolt needed for Leicester to do big things next season.