Spare a thought for all the mortal goal-scoring experts the current Bundesliga has to offer. Keyword: mortal. Because whatever Robert Lewandowski and Timo Werner are currently doing in front of goal must be illegal in some countries. The prolific Bayern striker and the lightning-quick frontman of RB Leipzig stand at goal tallies of 16 and 12, respectively, 12 matchdays into the 2018–19 season. While Lewandowski and Werner have been in ludicrous form so far, the standout performances the two stars get all the attention and glory. So let us — we, fair people at StatsBomb — shine some light on the ‘other’ goal scorers one can find in the highest level of German pro football. Exempting those two, there are seven players who have scored at least six goals this campaign. Sorry, Marcus Thuram (five goals), Serge Gnabry (four goals plus one glorious moustache) and Jadon Sancho (four), but you awesome youngsters will surely come up in a future Bundesliga digest on this here fine website. The seven non-alien penalty box poachers can be divided into four categories. The question is — are these guys for real, or just on a very nice hot streak?

The (fairly) unknowns

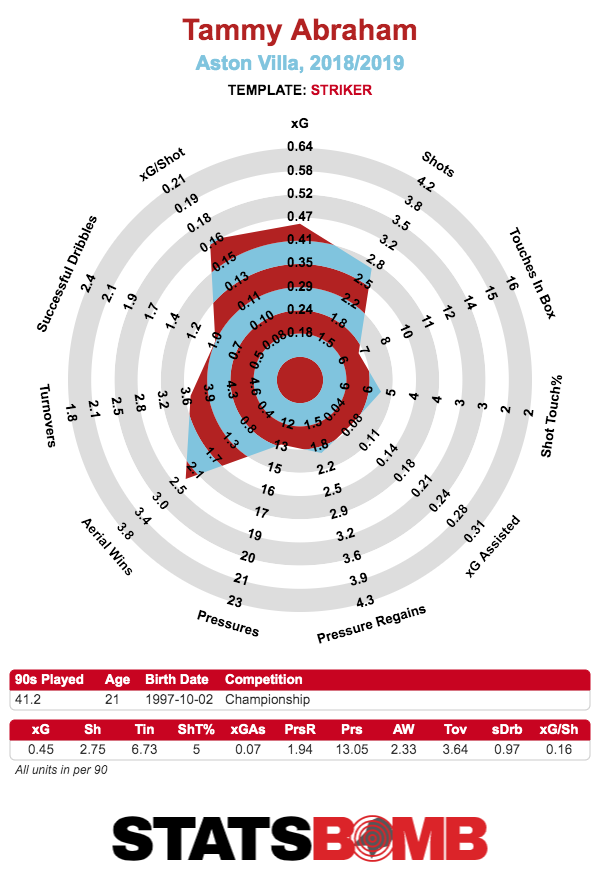

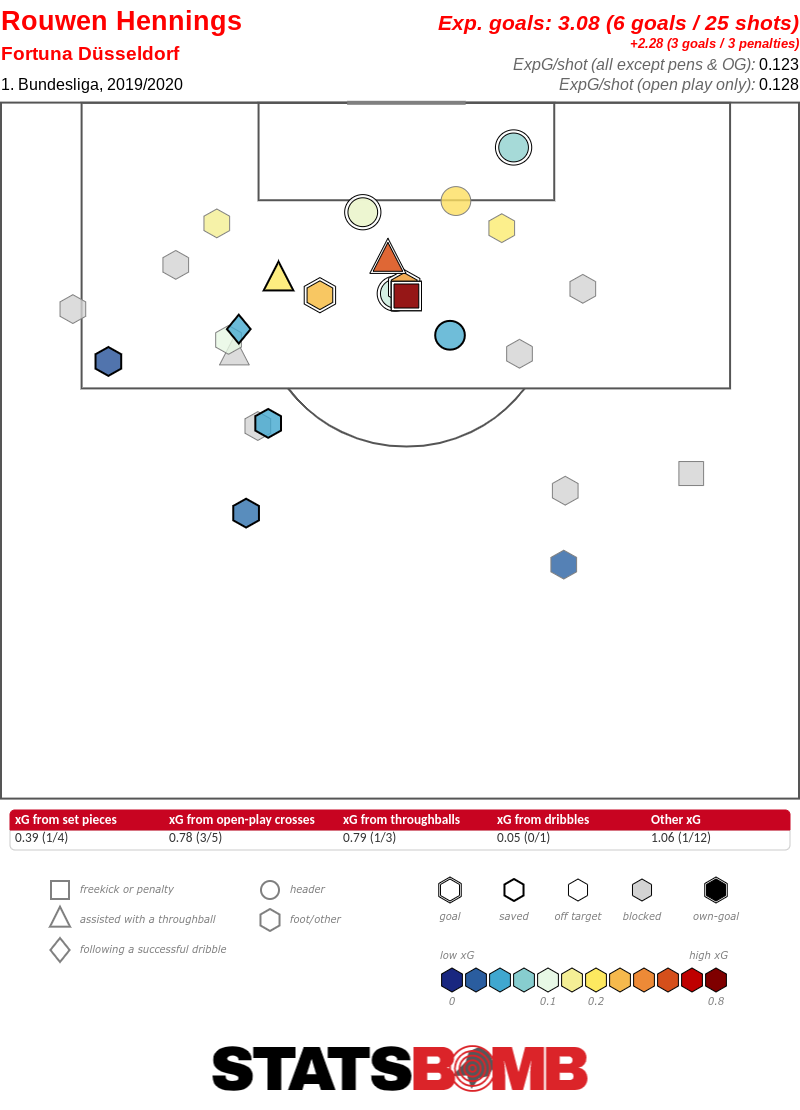

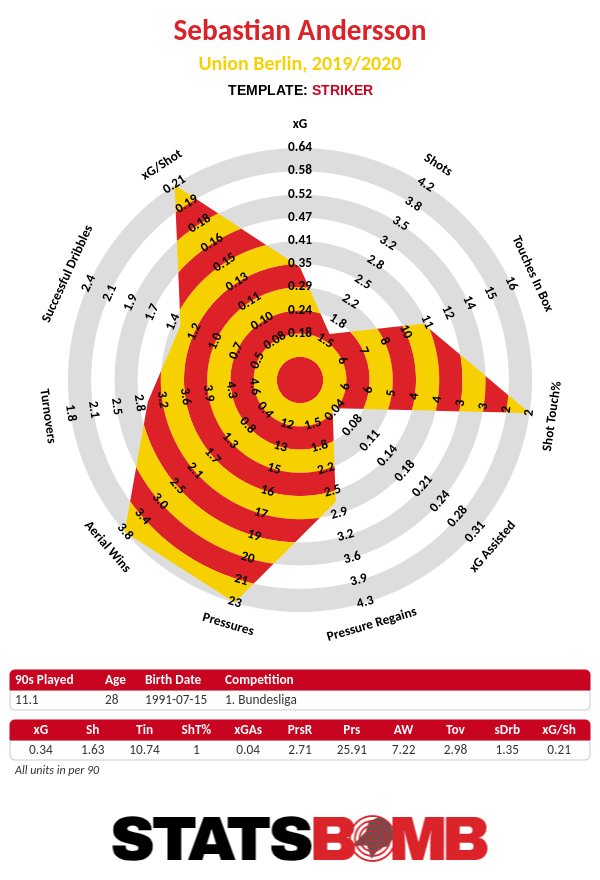

A big, big shoutout to Rouwen Hennings. The 32-year old Fortuna Düsseldorf attacker flopped at Burnley just three years ago. After being a bench-warmer during their 2016–17 Championship campaign, Hennings was let go on a free transfer after Düsseldorf was promoted. The veteran lefty is now enjoying the best season of his career — which took him to four other German clubs in the lower-level leagues — by a wide margin. Hennings has already scored nine goals this Bundesliga season, three from the penalty spot, the rest from, ehm, quite the hot finishing touch he's applied in and around the box. Fortuna players not named Hennings have just mustered six goals in twelve league games so far, so the streaky shooting of their frontman has been more than welcome in the early months of a season that has the makings of a tough relegation battle for Düsseldorf.  The other fairly anonymous name toward the top of the Bundesliga’s goal scorers charts seems to have more staying power given his all-around skills. Sebastian Andersson (28) is utterly crucial to surprise outfit Union Berlin. The Christmas carol club from the capital city is on a three-game winning streak, with Andersson scoring three crucial goals in the last two wins (a brace in the 2–3 road win at Mainz, the stoppage time clincher in a 2–0 home upset of Mönchengladbach). The 6'3" frontman is surprisingly mobile for someone his size, and his off-ball work rate is solid. Andersson may have developed later, but he's still got plenty of years left, and his aerial prowess and diligent pressing make him a reasonable option as a target man in a 4-4-2 formation, should things change at Union, or Sweden call him up. He may not take a lot of shots, with only 1.63 per 90, but when he does, they're lethal. He's averaging a sky-high 0.21 expected goals per shot.

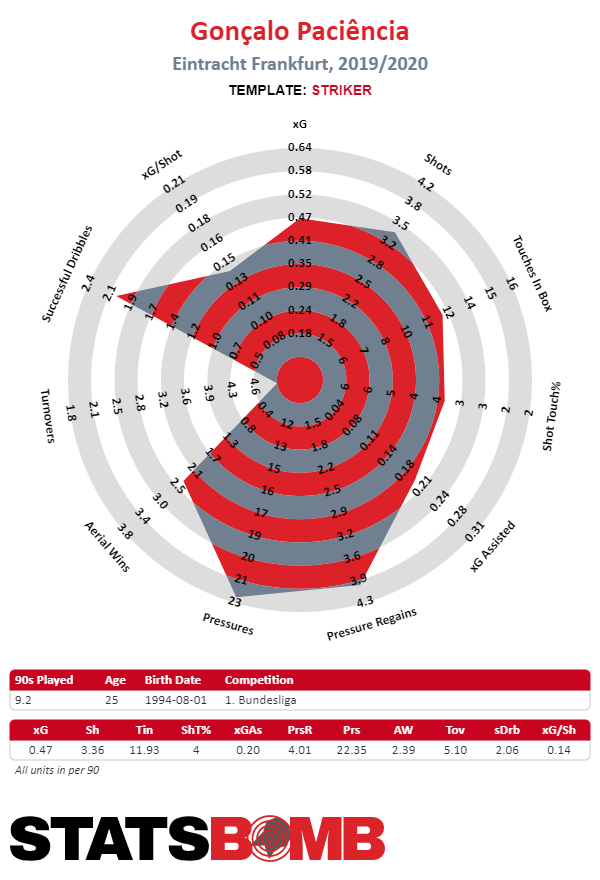

The other fairly anonymous name toward the top of the Bundesliga’s goal scorers charts seems to have more staying power given his all-around skills. Sebastian Andersson (28) is utterly crucial to surprise outfit Union Berlin. The Christmas carol club from the capital city is on a three-game winning streak, with Andersson scoring three crucial goals in the last two wins (a brace in the 2–3 road win at Mainz, the stoppage time clincher in a 2–0 home upset of Mönchengladbach). The 6'3" frontman is surprisingly mobile for someone his size, and his off-ball work rate is solid. Andersson may have developed later, but he's still got plenty of years left, and his aerial prowess and diligent pressing make him a reasonable option as a target man in a 4-4-2 formation, should things change at Union, or Sweden call him up. He may not take a lot of shots, with only 1.63 per 90, but when he does, they're lethal. He's averaging a sky-high 0.21 expected goals per shot.  The third ‘unknown’ finding the net with surprising ease is discussed in StatsBomb’s guide of Bundesliga break-out players, published earlier this season. Gonçalo Paciência’s mix of on-ball skill, positional awareness and aggressive play means he's the number one option in Eintracht Frankfurt’s rotation of strikers. A nice achievement for the 25-year-old Portuguese attacker, given the big-name competition in André Silva and Bas Dost. Paciência looks to have leapfrogged his Silva as well in the Portugal national team hierarchy.

The third ‘unknown’ finding the net with surprising ease is discussed in StatsBomb’s guide of Bundesliga break-out players, published earlier this season. Gonçalo Paciência’s mix of on-ball skill, positional awareness and aggressive play means he's the number one option in Eintracht Frankfurt’s rotation of strikers. A nice achievement for the 25-year-old Portuguese attacker, given the big-name competition in André Silva and Bas Dost. Paciência looks to have leapfrogged his Silva as well in the Portugal national team hierarchy.

Nils Petersen is still ‘Nils-ing’

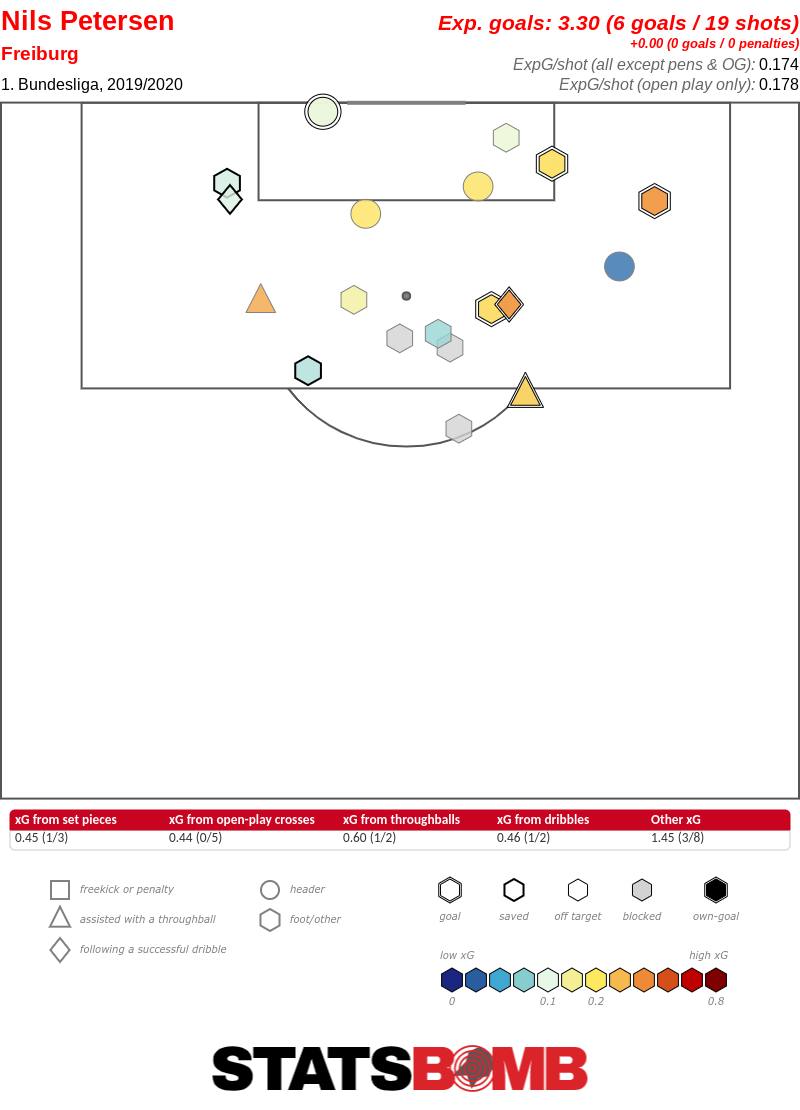

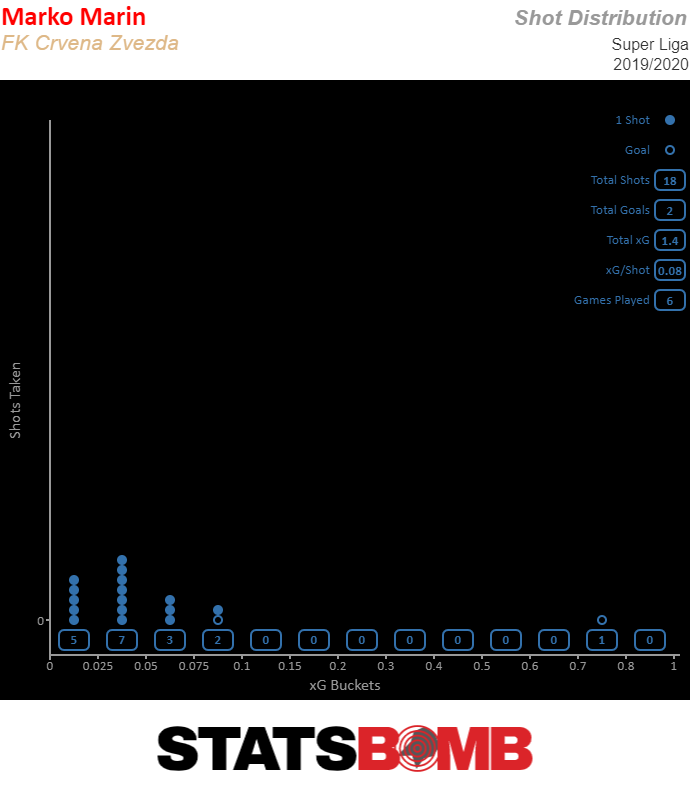

No, Petersen is not the most elegant player to grace the Bundesliga pitches. But his somewhat janky-looking playing style leaves him perpetually underrated. The Freiburg striker continues to do what he does: score some goals. He’s scored six in twelve, bringing his total in the 1. Bundesliga to 50 goals in 113 league games. Just look at this shot map, friends. Good ol’ Nils sure knows what a good shooting opportunity looks like, even if his goal total seems somewhat generous given the underlying xG.

Playmakers who ‘have to’ score to keep their offenses humming

Playmakers who ‘have to’ score to keep their offenses humming

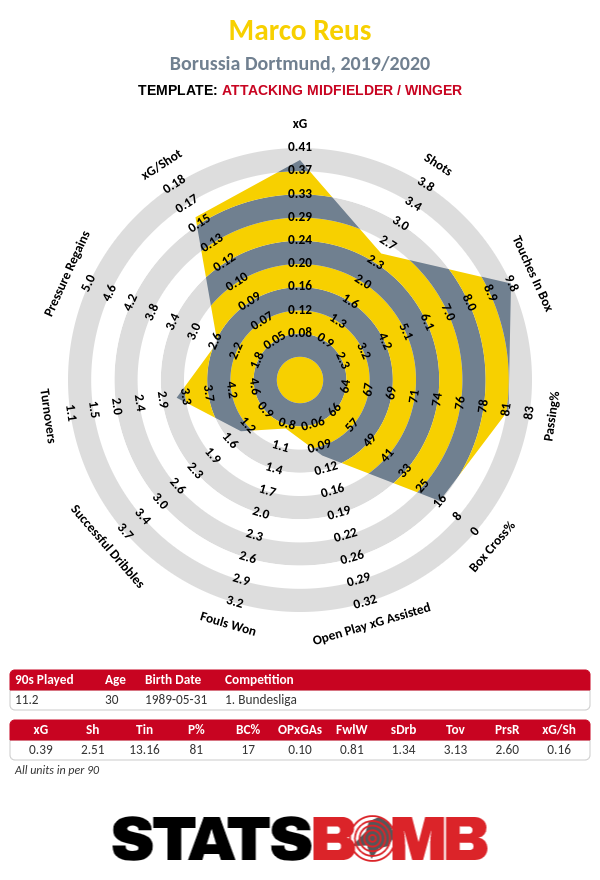

Please, I beg of you. Appreciate the greatness of Marco Reus while we still can. The injury-plagued superstar of Borussia Dortmund has, frustratingly, been turned into somewhat more of an out-and-out second striker under Lucien Favre than the free-wheeling playmaker slash wide creator slash box-hunting attacking force he was in years past. But Reus is still such a good player. Even in a team that is malfunctioning in all types of ways at the moment.  But while we’ve gotten used to Reus chipping in as a goalscorer as well as being the team’s main creative hub, Dortmund’s arch-rivals Schalke 04 have been pleasantly surprised by Amine Harit suddenly finding his scoring boots. The dribbling expert scored just four goals in 60 official games across all competitions in his first two seasons for the Königsblauen. Yet this season he's scored six already, and two have been late game-winners. If the 22-year-old attacking midfielder is able to continue in adding goal-scoring to his already impressive skill-set, we might see his silky smooth dribbles at a bigger club than Schalke sooner rather than later. If Harit is set on achieving that, he’ll need to improve his shot decisions quickly, though.

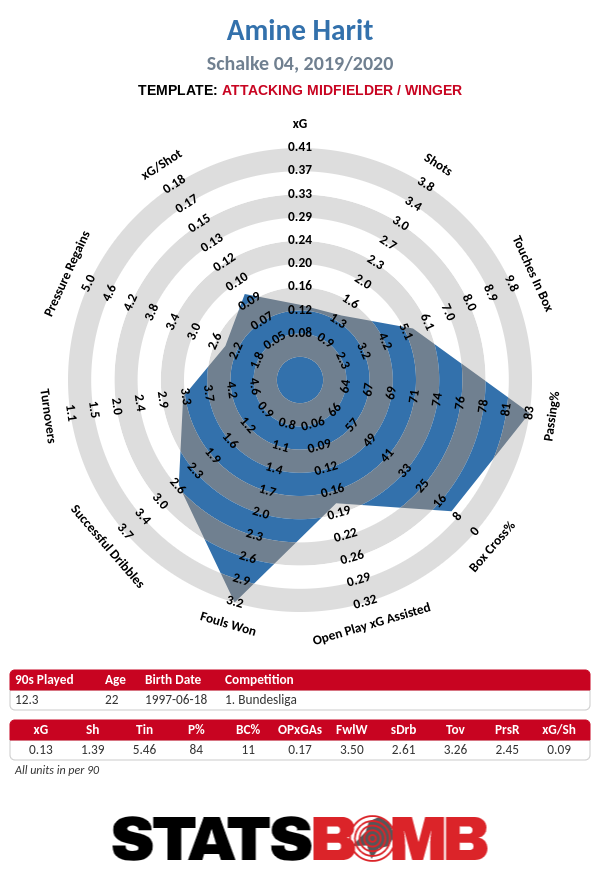

But while we’ve gotten used to Reus chipping in as a goalscorer as well as being the team’s main creative hub, Dortmund’s arch-rivals Schalke 04 have been pleasantly surprised by Amine Harit suddenly finding his scoring boots. The dribbling expert scored just four goals in 60 official games across all competitions in his first two seasons for the Königsblauen. Yet this season he's scored six already, and two have been late game-winners. If the 22-year-old attacking midfielder is able to continue in adding goal-scoring to his already impressive skill-set, we might see his silky smooth dribbles at a bigger club than Schalke sooner rather than later. If Harit is set on achieving that, he’ll need to improve his shot decisions quickly, though.  Harit really is doing a lot of things well with the ball at his feet; however, he is neither shooting a lot (1.39 shots per 90), nor taking high-value shots (0.09 xG per shot). If the goals are going to keep coming, at least one of those two things will have to change.

Harit really is doing a lot of things well with the ball at his feet; however, he is neither shooting a lot (1.39 shots per 90), nor taking high-value shots (0.09 xG per shot). If the goals are going to keep coming, at least one of those two things will have to change.

Big Wout keeps surprising

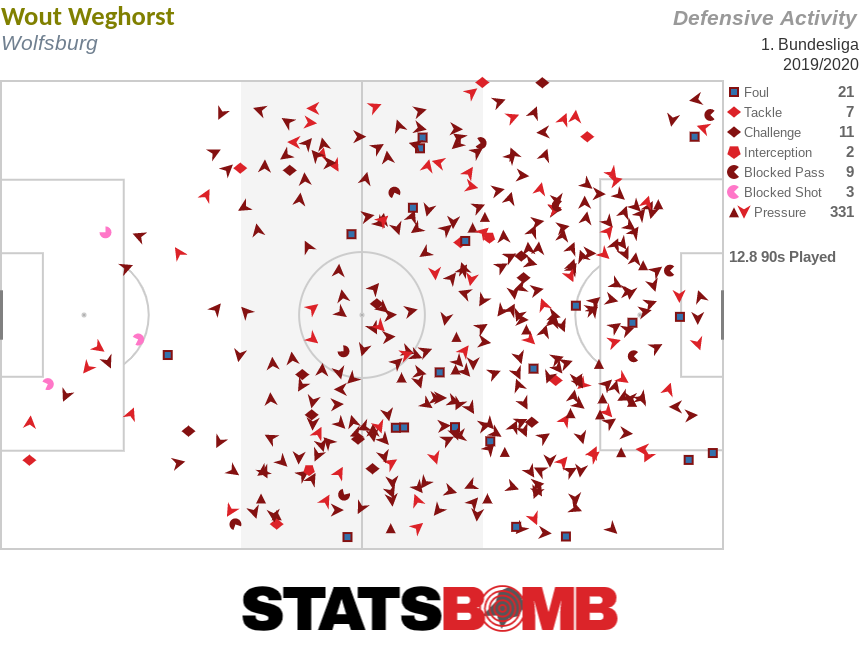

A little more than five years ago, Wout Weghorst was a back-up striker at lowly FC Emmen in the second tier of Dutch football. Weghorst was deemed too tall, too slow, too immobile and too stubborn to be the 'total striker’ Dutch coaches and scouts are often times obsessed with. But mid-level Eredivisie squad Heracles Almelo took a shine to Weghorst, who proved himself a useful target man up top in his first season at the highest level, and developed into a solid goalscorer in his second. Next up for the 6'6" Weghorst was a move to AZ Alkmaar. AZ? The analytically-driven club that ‘doesn’t do long crosses into the box’ signed the Eredivisie's only good aerial specialist? Yup. Turns out, Weghorst can do much more than win headers and poach goals in the box. The big frontman impressed at Alkmaar due to his almost-insane work rate when pressing the opposition’s build-up. When VfL Wolfsburg brought in Weghorst for a lofty (at the time) sum of 10.5 million Euros, Dutch pundits started their fourth ‘Weghorst cycle of doubt'. But really, this dude is just a fine footballer. It's just his size and incredible confidence he openly exudes at times can distract from his funky, but very useful, set of skills.

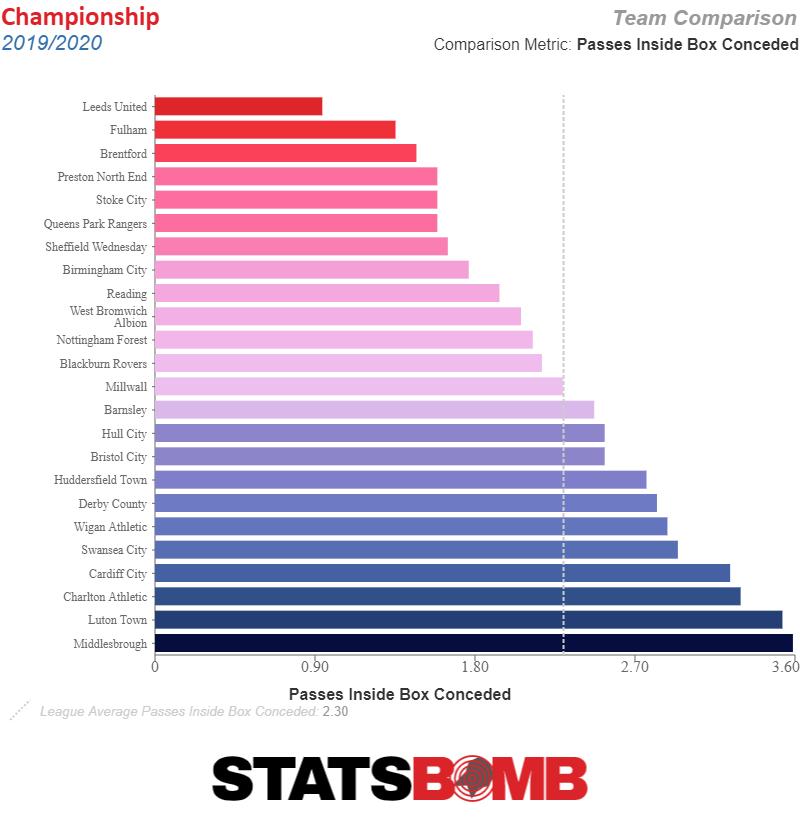

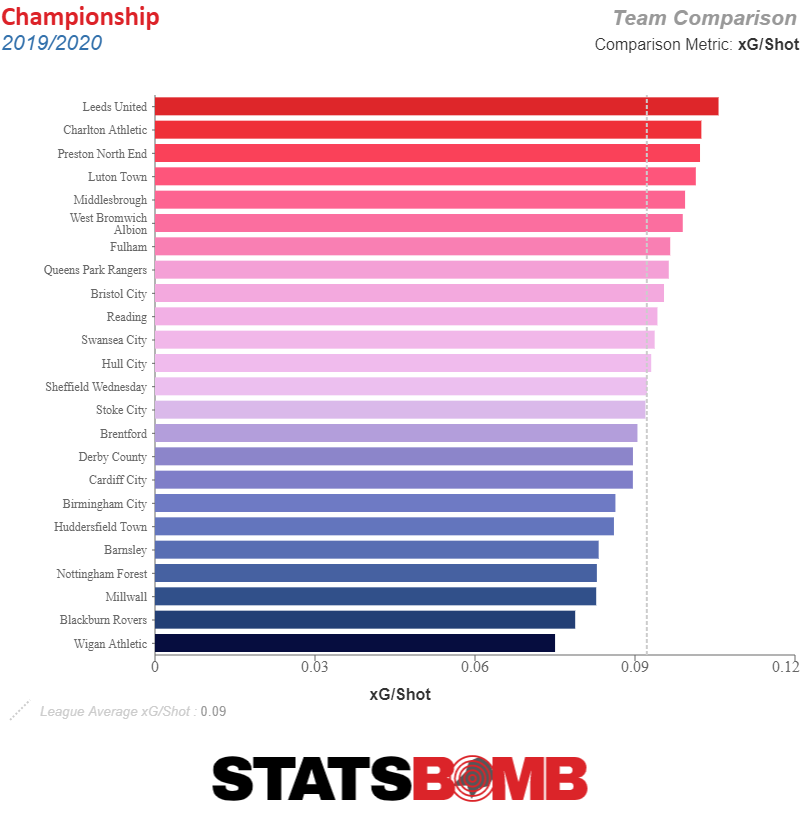

Stoke already seem to have a mid-table process in place, so don’t be shocked if O’Neill starts to pick up points at a rate you’d expect from a mid-table side even before he makes changes. Until recently, Luton Town were treading water in a deep-but-ultimately-safe tide, but five defeats on the spin has dragged them into choppier waters. Captain of the ship is former long-term Roberto Martinez sidekick Graeme Jones, so with that in mind it may not be too much of a surprise that whilst things are looking relatively healthy at the attacking end of the pitch, they appear a little sick at the back. Off the ball, Luton simply aren’t doing enough to disrupt the opposition. It's just a little too easy for teams to move the ball into dangerous areas in Luton’s third. Their opponents' pass completion rate is 79%, the fourth-highest in the Championship. In itself, this is not a bad thing, as long as the team are forcing their opponents to complete those passes in areas where they can’t hurt. But Luton have also conceded the fourth most deep completions (completed passes within 20 metres of goal) and are then allowing the opponent to move the ball into the penalty area, conceding passes inside the penalty box at a rate worse than only one other side in the league.

Stoke already seem to have a mid-table process in place, so don’t be shocked if O’Neill starts to pick up points at a rate you’d expect from a mid-table side even before he makes changes. Until recently, Luton Town were treading water in a deep-but-ultimately-safe tide, but five defeats on the spin has dragged them into choppier waters. Captain of the ship is former long-term Roberto Martinez sidekick Graeme Jones, so with that in mind it may not be too much of a surprise that whilst things are looking relatively healthy at the attacking end of the pitch, they appear a little sick at the back. Off the ball, Luton simply aren’t doing enough to disrupt the opposition. It's just a little too easy for teams to move the ball into dangerous areas in Luton’s third. Their opponents' pass completion rate is 79%, the fourth-highest in the Championship. In itself, this is not a bad thing, as long as the team are forcing their opponents to complete those passes in areas where they can’t hurt. But Luton have also conceded the fourth most deep completions (completed passes within 20 metres of goal) and are then allowing the opponent to move the ball into the penalty area, conceding passes inside the penalty box at a rate worse than only one other side in the league.  Needless to say, when the ball’s spending this much time in those threatening areas, it’s inevitably going to translate into dangerous chances when the opponent decides to pull the trigger. Luton are conceding the most dangerous chances in the league per game.

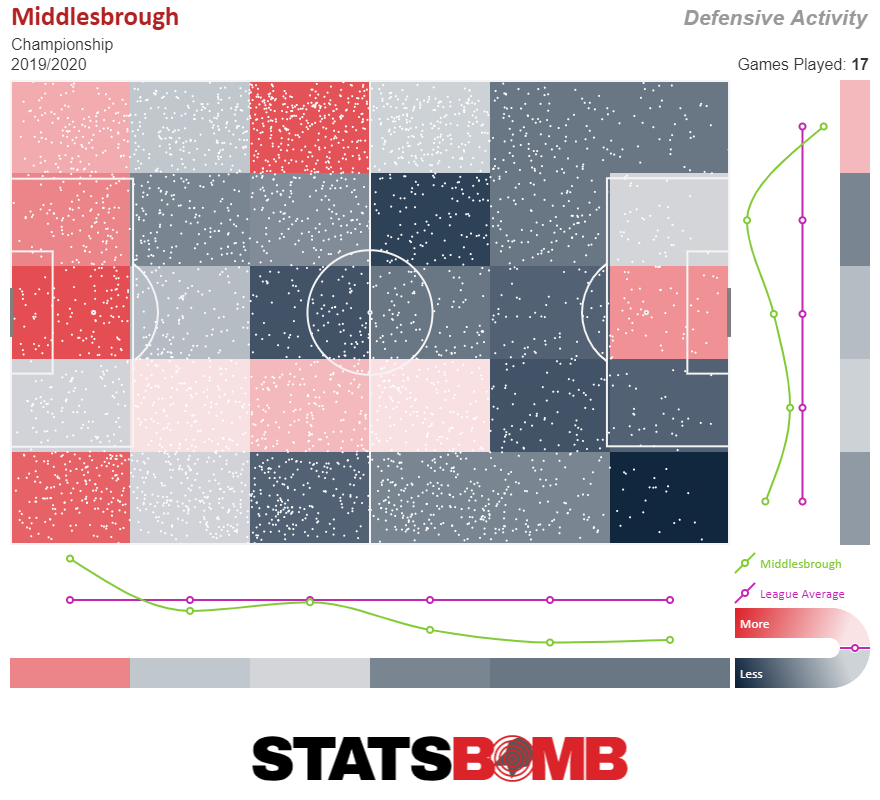

Needless to say, when the ball’s spending this much time in those threatening areas, it’s inevitably going to translate into dangerous chances when the opponent decides to pull the trigger. Luton are conceding the most dangerous chances in the league per game.  Transforming a Tony Pulis oil tanker into a luxury yacht was never going to be a straightforward task, but so far Jonathan Woodgate has really struggled to mould Middlesbrough into a new machine. This job was always going to be a tough way for him to cut his managerial teeth, especially with the knowledge that parachute payments will be cut once again in the summer, but the

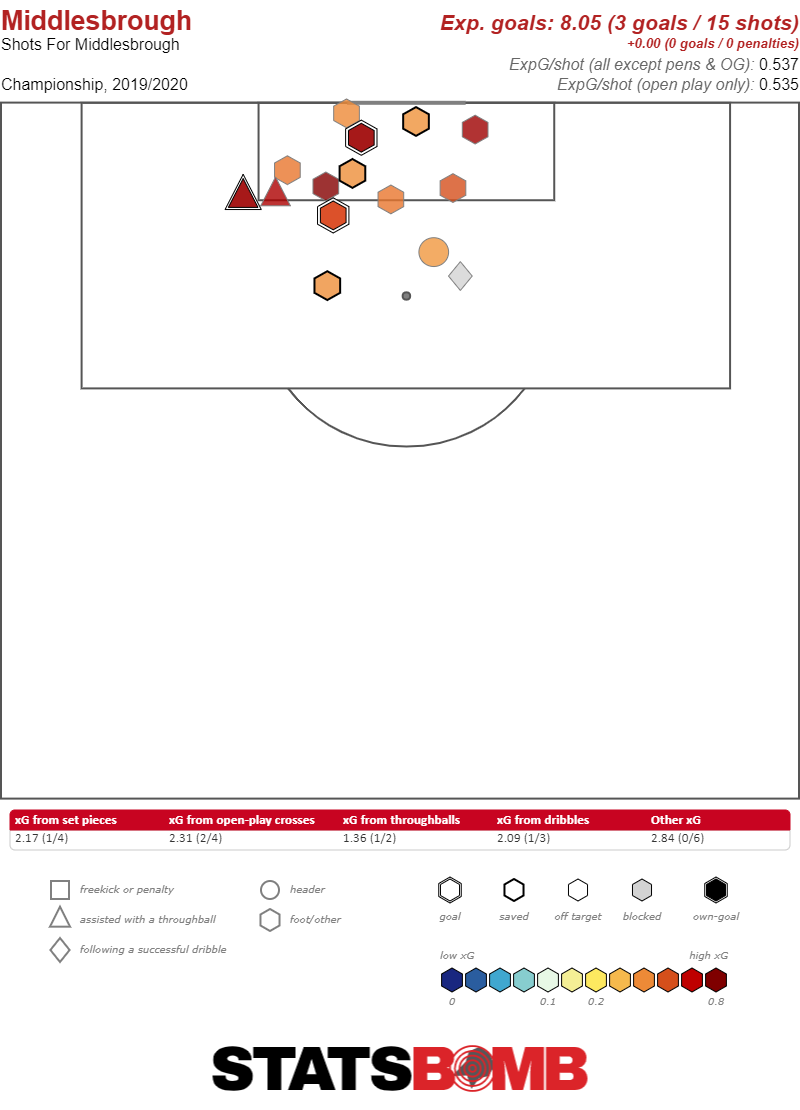

Transforming a Tony Pulis oil tanker into a luxury yacht was never going to be a straightforward task, but so far Jonathan Woodgate has really struggled to mould Middlesbrough into a new machine. This job was always going to be a tough way for him to cut his managerial teeth, especially with the knowledge that parachute payments will be cut once again in the summer, but the  This team's current form doesn't pass the eye test; they look disjointed both in and out of possession. However, there’s definitely a case to be made that as bad as Boro look on the pitch, there’s something in the numbers that suggests they could be better off. After all, you can hardly lay blame at Woodgate’s door for the bizarre amount of clear-cut chances, several of which have quite literally been open goals, that have been missed by his team so far. All of these attempts had a 35% or higher expected conversion rate.

This team's current form doesn't pass the eye test; they look disjointed both in and out of possession. However, there’s definitely a case to be made that as bad as Boro look on the pitch, there’s something in the numbers that suggests they could be better off. After all, you can hardly lay blame at Woodgate’s door for the bizarre amount of clear-cut chances, several of which have quite literally been open goals, that have been missed by his team so far. All of these attempts had a 35% or higher expected conversion rate.  Regardless of where things might go, for now the situation looks dismal. .Fifteen shots. Eight expected goals. Three actual goals. Lots of missed sitters. Woodgate tearing his hair out. Middlesbrough in the relegation zone. Huddersfield parachuted Danny and Nicky Cowley in to save the ship quickly sinking under Jan Siewert, and the East London pair have set the Terriers on an instant path of recovery, going 4-5-3 in their twelve games in charge. Given Huddersfield’s tragic record before their arrival — they’d won just 1 of their previous 31 league games going back to November 2018 — this is a dramatic turnaround. The gameplan in achieving this in the short-term was clear and epitomised in their first win, which came in their fourth attempt away at Stoke. Huddersfield played the long game and sat 11 men behind the ball for 75 minutes, then scored on a counter attack that you’d imagine was rehearsed 100 times over in training prior to the game.

Regardless of where things might go, for now the situation looks dismal. .Fifteen shots. Eight expected goals. Three actual goals. Lots of missed sitters. Woodgate tearing his hair out. Middlesbrough in the relegation zone. Huddersfield parachuted Danny and Nicky Cowley in to save the ship quickly sinking under Jan Siewert, and the East London pair have set the Terriers on an instant path of recovery, going 4-5-3 in their twelve games in charge. Given Huddersfield’s tragic record before their arrival — they’d won just 1 of their previous 31 league games going back to November 2018 — this is a dramatic turnaround. The gameplan in achieving this in the short-term was clear and epitomised in their first win, which came in their fourth attempt away at Stoke. Huddersfield played the long game and sat 11 men behind the ball for 75 minutes, then scored on a counter attack that you’d imagine was rehearsed 100 times over in training prior to the game.  This bend-but-don’t-break approach has served the Terriers well; just one defeat in their last ten games has lifted them out of the relegation zone. But it’s fair to say such a dramatic improvement has been aided by a small dose of fortune, with the team finishing clinically since the Cowley brothers came in, maximising their results compared to their performances.

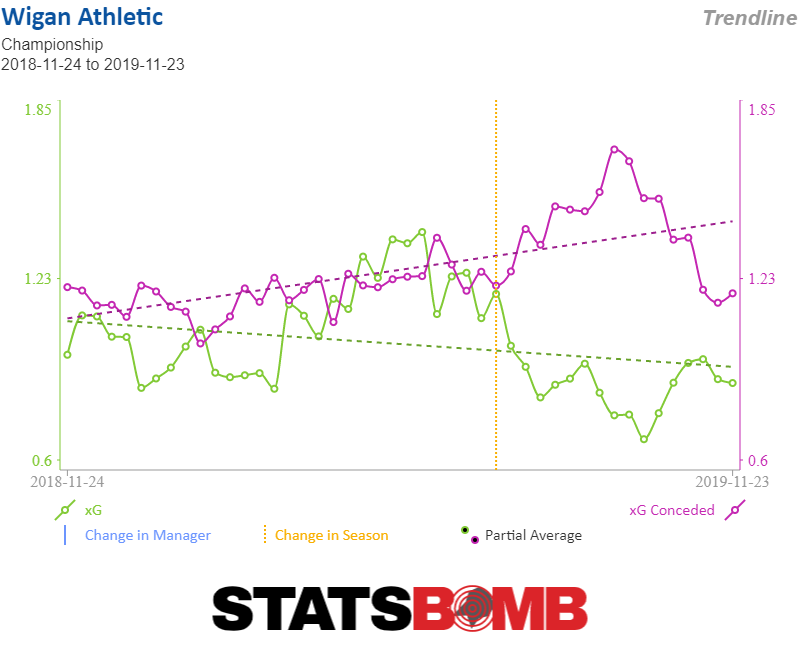

This bend-but-don’t-break approach has served the Terriers well; just one defeat in their last ten games has lifted them out of the relegation zone. But it’s fair to say such a dramatic improvement has been aided by a small dose of fortune, with the team finishing clinically since the Cowley brothers came in, maximising their results compared to their performances.  In general, things are looking up for Huddersfield. The opposite, however, is true for Wigan. After promotion, they managed a solid first season in 2018–19, comfortably avoiding the drop. But rather than pushing on from there, the team has instead gone backward.

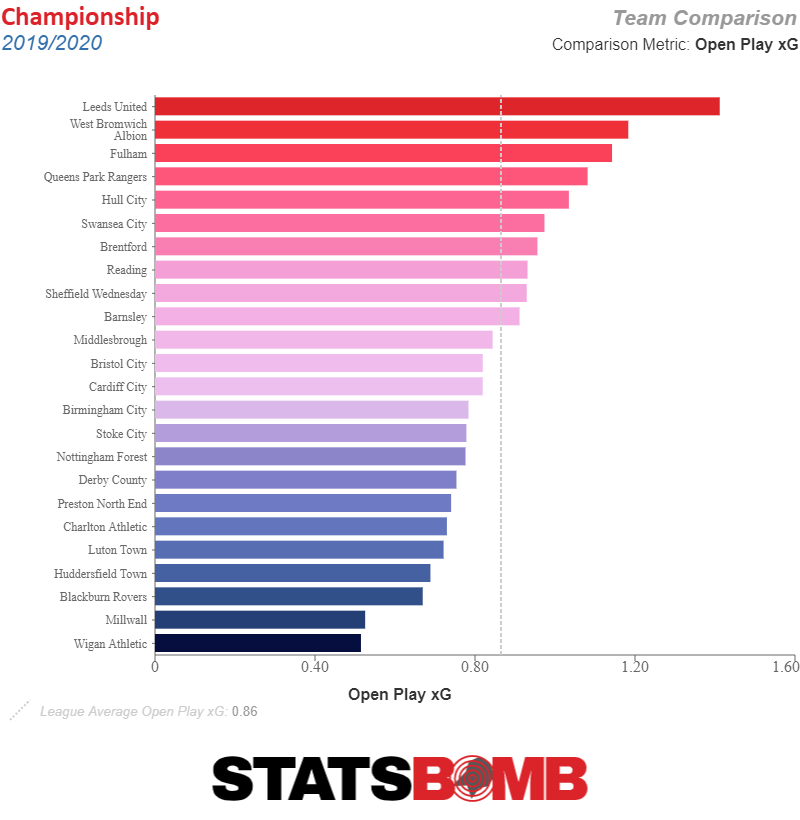

In general, things are looking up for Huddersfield. The opposite, however, is true for Wigan. After promotion, they managed a solid first season in 2018–19, comfortably avoiding the drop. But rather than pushing on from there, the team has instead gone backward.  They were roughly equally as good in both attack and defence last season, but now they're equally as bad, having gotten worse at both ends of the pitch, creating less and conceding more. In defence, the main concern and an area they could quickly improve is in their defending of set pieces, conceding a league-high nine goals from set play situations. It’s not just that their opponents are finishing well in these situations either, as Wigan also have the worst expected goals conceded rate in this phase of play. At the other end, it’s in open play that they’re struggling. Wigan are rock-bottom in the Championship for expected goals from open play and, whilst they’re only 18

They were roughly equally as good in both attack and defence last season, but now they're equally as bad, having gotten worse at both ends of the pitch, creating less and conceding more. In defence, the main concern and an area they could quickly improve is in their defending of set pieces, conceding a league-high nine goals from set play situations. It’s not just that their opponents are finishing well in these situations either, as Wigan also have the worst expected goals conceded rate in this phase of play. At the other end, it’s in open play that they’re struggling. Wigan are rock-bottom in the Championship for expected goals from open play and, whilst they’re only 18 Lastly, they may be 14

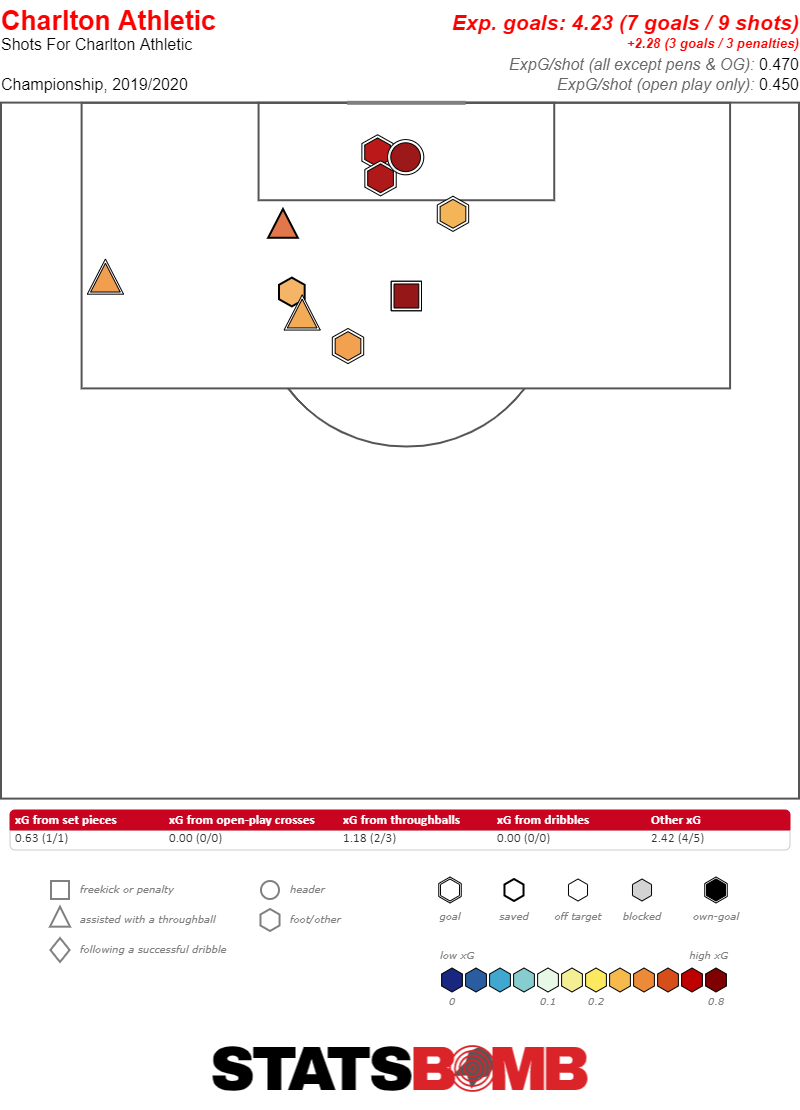

Lastly, they may be 14 Charlton have made their higher-probability chances count, converting seven of their nine shots with a goal probability of 30% or greater, whilist converting 3/3 penalties.

Charlton have made their higher-probability chances count, converting seven of their nine shots with a goal probability of 30% or greater, whilist converting 3/3 penalties.  Charlton’s issues really involve shot volume. For all their good work in creating and clinically converting the occasional good chance, their threat is fairly blunt otherwise, taking only 9.5 shots per game overall — the lowest in the Championship. This isn’t counterbalanced by a tight defence at the other end, which has conceded 15.7 shots per game, the leakiest in the Championship. Given they’re still nine points above the relegation zone at the time of writing, those early season points could play a crucial role in their survival bid. Yet the stats suggest their long-term form will more closely resemble their recent 2-3-7 record than their opening 4-2-0 . Charlton’s best chance of survival may be to just hope they sink slowly enough to avoid being caught by the sharks circling below them.

Charlton’s issues really involve shot volume. For all their good work in creating and clinically converting the occasional good chance, their threat is fairly blunt otherwise, taking only 9.5 shots per game overall — the lowest in the Championship. This isn’t counterbalanced by a tight defence at the other end, which has conceded 15.7 shots per game, the leakiest in the Championship. Given they’re still nine points above the relegation zone at the time of writing, those early season points could play a crucial role in their survival bid. Yet the stats suggest their long-term form will more closely resemble their recent 2-3-7 record than their opening 4-2-0 . Charlton’s best chance of survival may be to just hope they sink slowly enough to avoid being caught by the sharks circling below them.

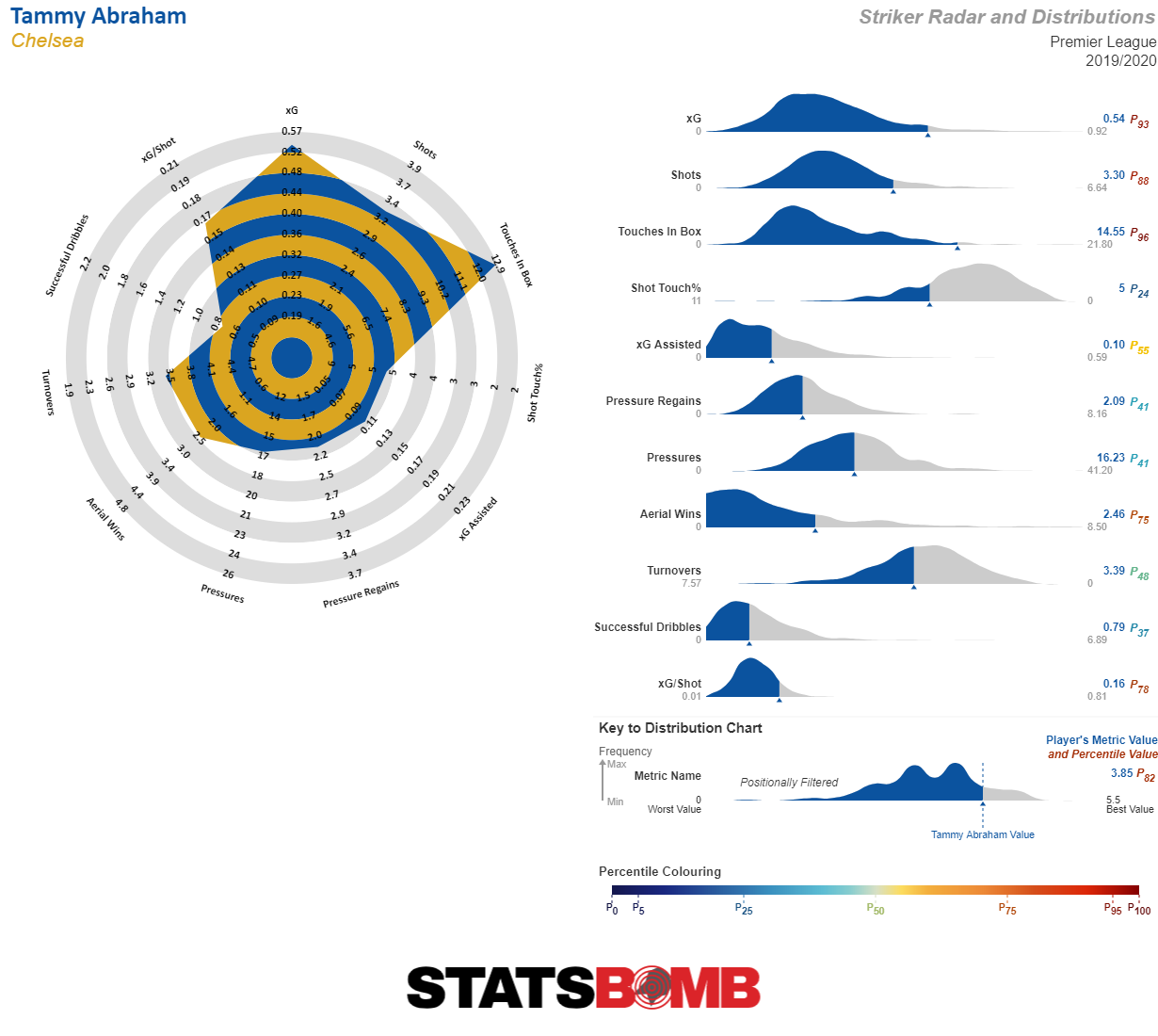

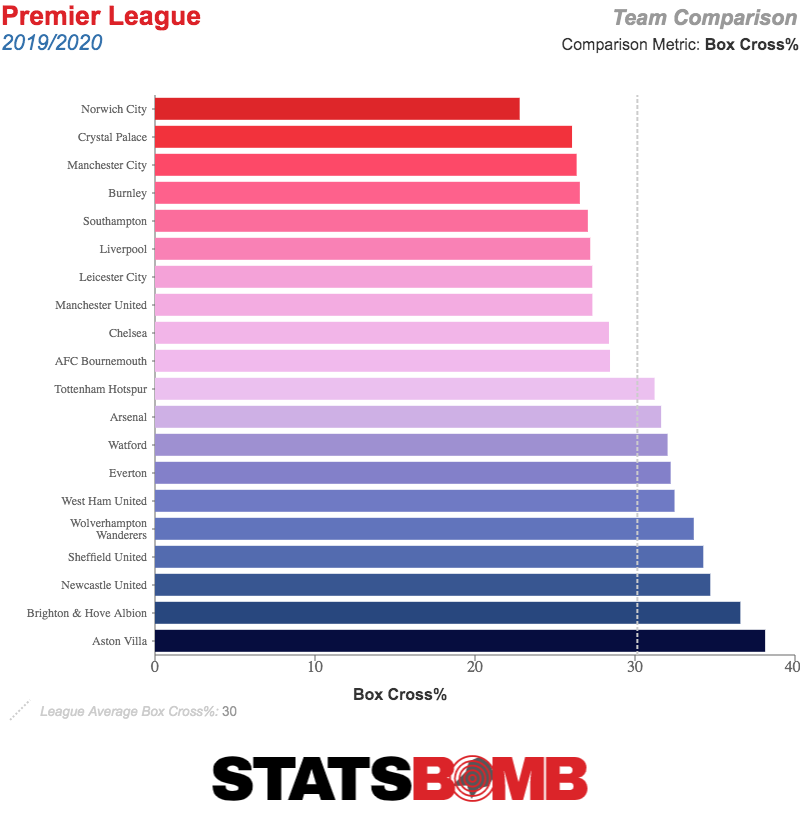

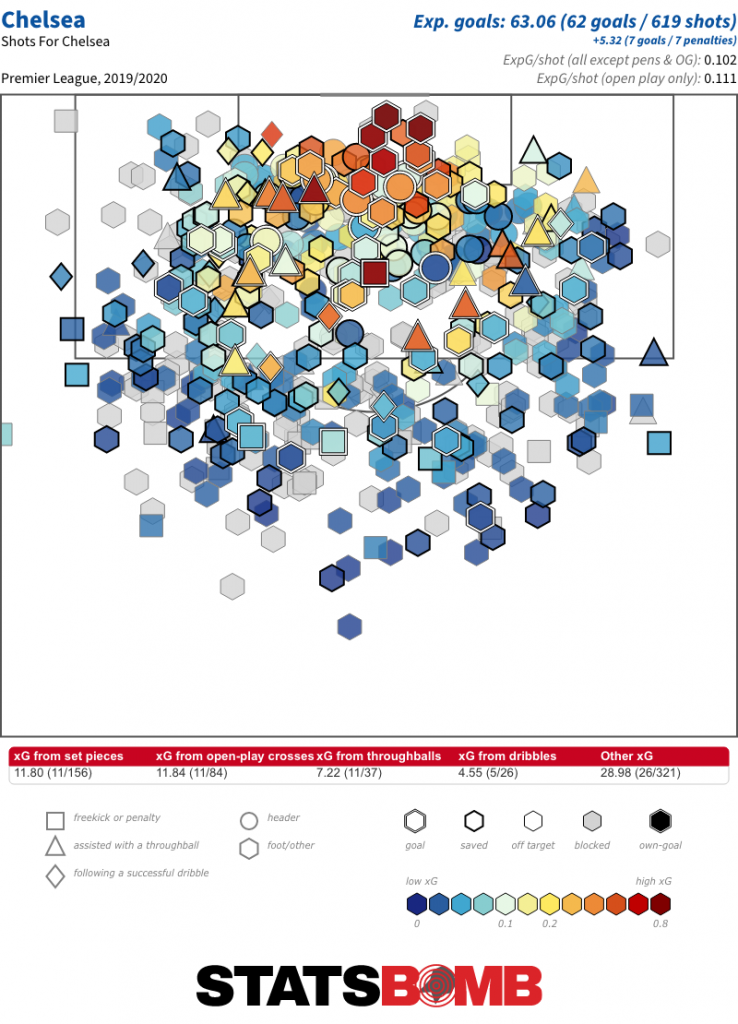

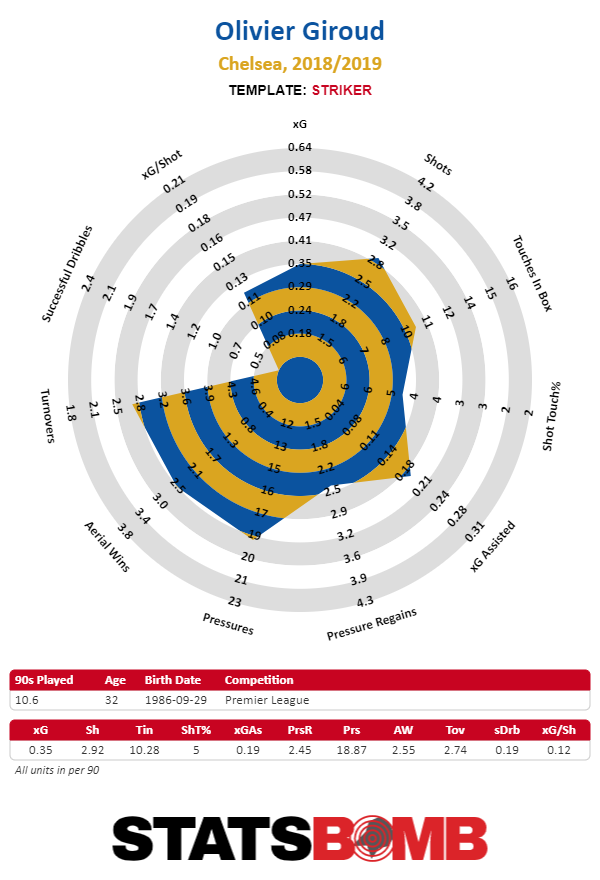

While some sides are embracing elaborate set-piece routines to find new edges, Chelsea isn't one of them. Frank Lampard's side have the lowest xG per set piece of any team in the league. Lampard admits that the Chelsea team he played in did not work on elaborate routines, believing just getting it into the area with players like Didier Drogba and John Terry was enough. Unfortunately, it doesn't look like that's enough now.

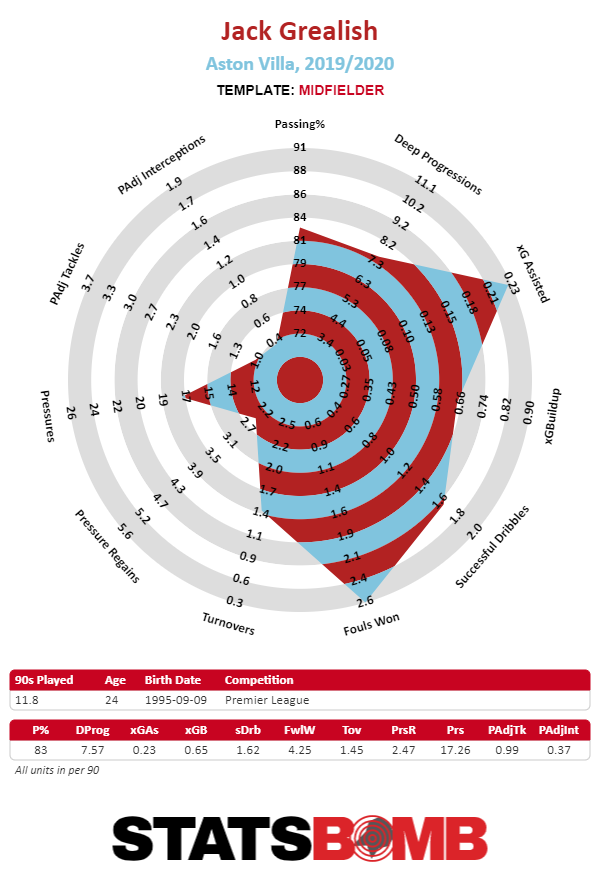

While some sides are embracing elaborate set-piece routines to find new edges, Chelsea isn't one of them. Frank Lampard's side have the lowest xG per set piece of any team in the league. Lampard admits that the Chelsea team he played in did not work on elaborate routines, believing just getting it into the area with players like Didier Drogba and John Terry was enough. Unfortunately, it doesn't look like that's enough now.  Jack Grealish is earning himself a fair bit of hype at the moment and the numbers indicate it's much deserved. Aston Villa's captain is completing the most open play passes into the box of any non-top-six player, while also winning more fouls than anyone else in the league. In Grealish, Villa have an excellent creator, whether he's playing on the left or in a central midfield role.

Jack Grealish is earning himself a fair bit of hype at the moment and the numbers indicate it's much deserved. Aston Villa's captain is completing the most open play passes into the box of any non-top-six player, while also winning more fouls than anyone else in the league. In Grealish, Villa have an excellent creator, whether he's playing on the left or in a central midfield role.

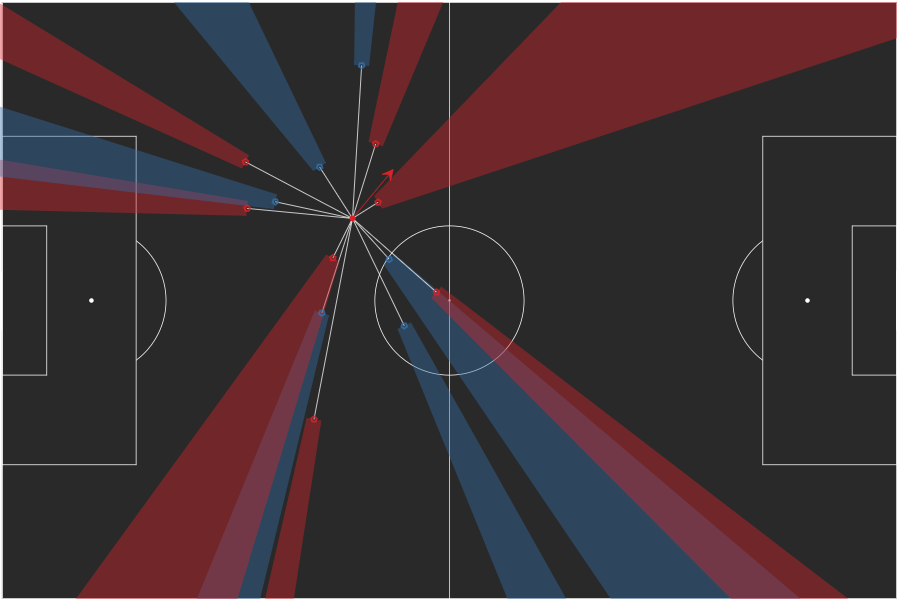

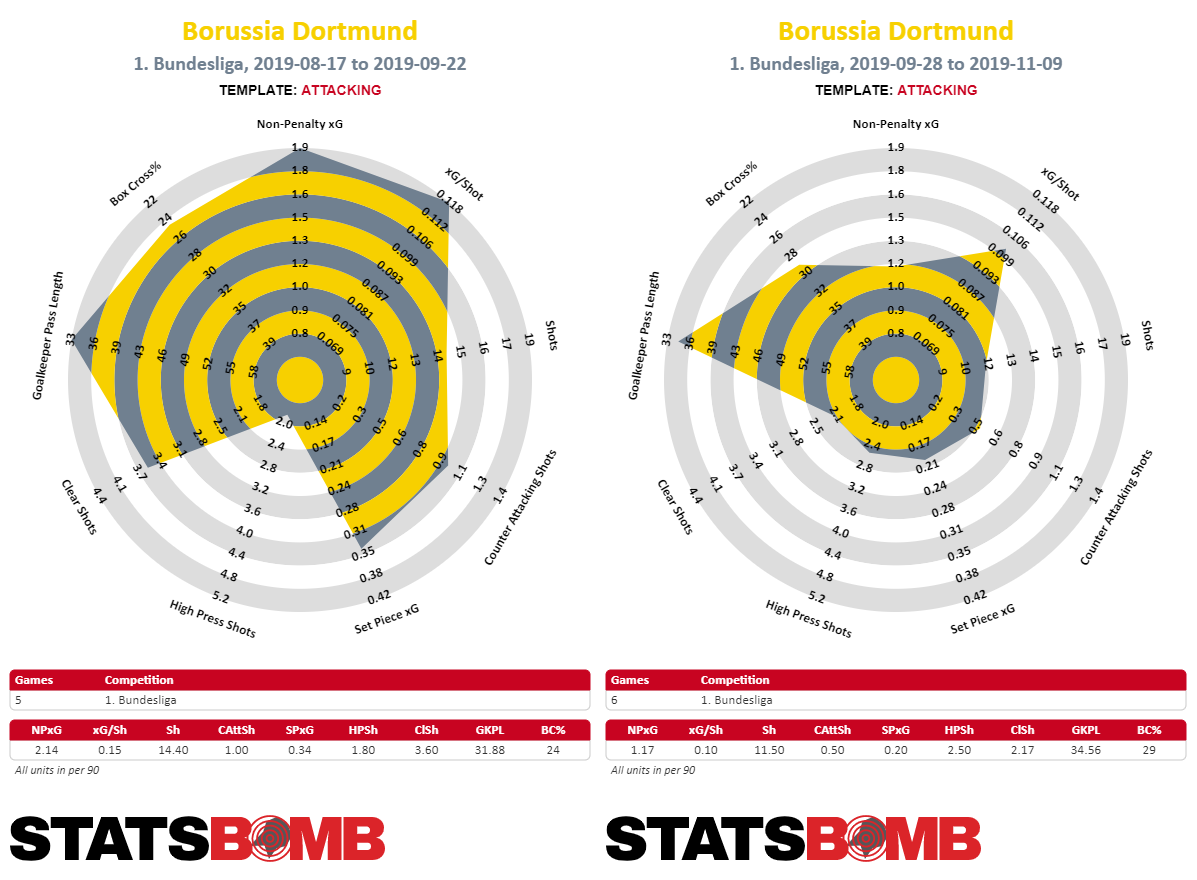

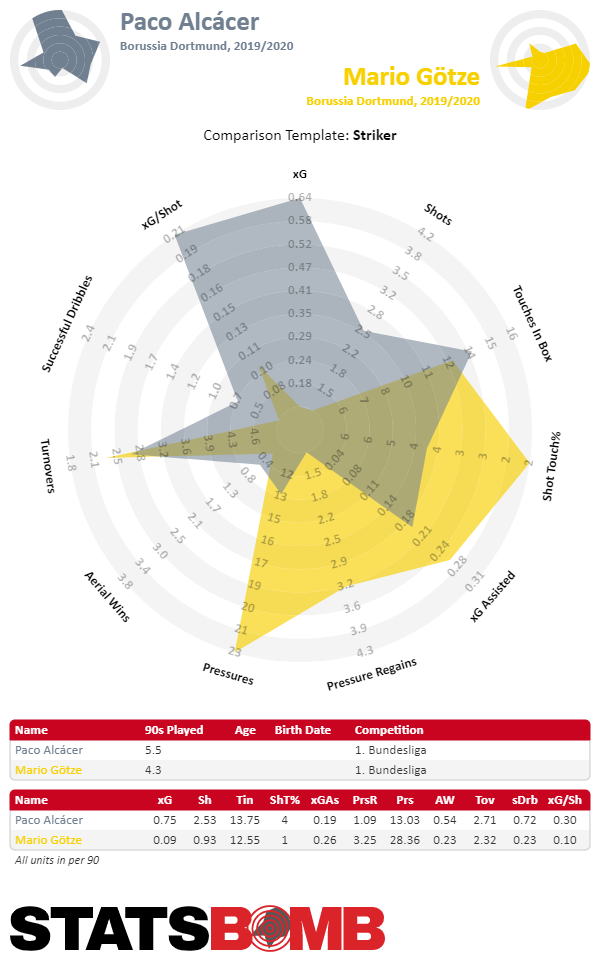

Comparison of Dortmund’s values in attack until Alcácer’s absence and since. Overall, Dortmund amassed fewer shots, while at the same time being less creative in attack, which one can infer from the larger rate of crosses, for example. Obviously, the toothless attacking performances were not singularly down to the absence of Alcácer, seeing as Dortmund faced some of the powerhouses of the league in Schalke, Mönchengladbach and Bayern, who all know to be solid defensively in their own ways. Still, it became evident that Dortmund do not have an adequate replacement at hand to allow the ball progression to flow through that one important target player, particularly in the transition into the final third and even more so when playing into the box. Mario Götze adds a number of qualities, but he is often used incorrectly when played at the very front of the formation. He would be of better use in central midfield, where his footballing intelligence and compartmentalised playing style would shine through for the better of the team. For the moment, though, Götze seems to have been tabbed as Alcácer’s replacement. However, this cannot be a long-term solution for a club as ambitious as BVB, especially as Götze’s time with the club may be over in the summer.

Comparison of Dortmund’s values in attack until Alcácer’s absence and since. Overall, Dortmund amassed fewer shots, while at the same time being less creative in attack, which one can infer from the larger rate of crosses, for example. Obviously, the toothless attacking performances were not singularly down to the absence of Alcácer, seeing as Dortmund faced some of the powerhouses of the league in Schalke, Mönchengladbach and Bayern, who all know to be solid defensively in their own ways. Still, it became evident that Dortmund do not have an adequate replacement at hand to allow the ball progression to flow through that one important target player, particularly in the transition into the final third and even more so when playing into the box. Mario Götze adds a number of qualities, but he is often used incorrectly when played at the very front of the formation. He would be of better use in central midfield, where his footballing intelligence and compartmentalised playing style would shine through for the better of the team. For the moment, though, Götze seems to have been tabbed as Alcácer’s replacement. However, this cannot be a long-term solution for a club as ambitious as BVB, especially as Götze’s time with the club may be over in the summer.  Götze and Alcácer could hardly be any more different from one another—even if we dismiss the context of the games. This holds especially true for the way they integrate themselves into general play, but also for their options in counter-attacks and fast attacks.

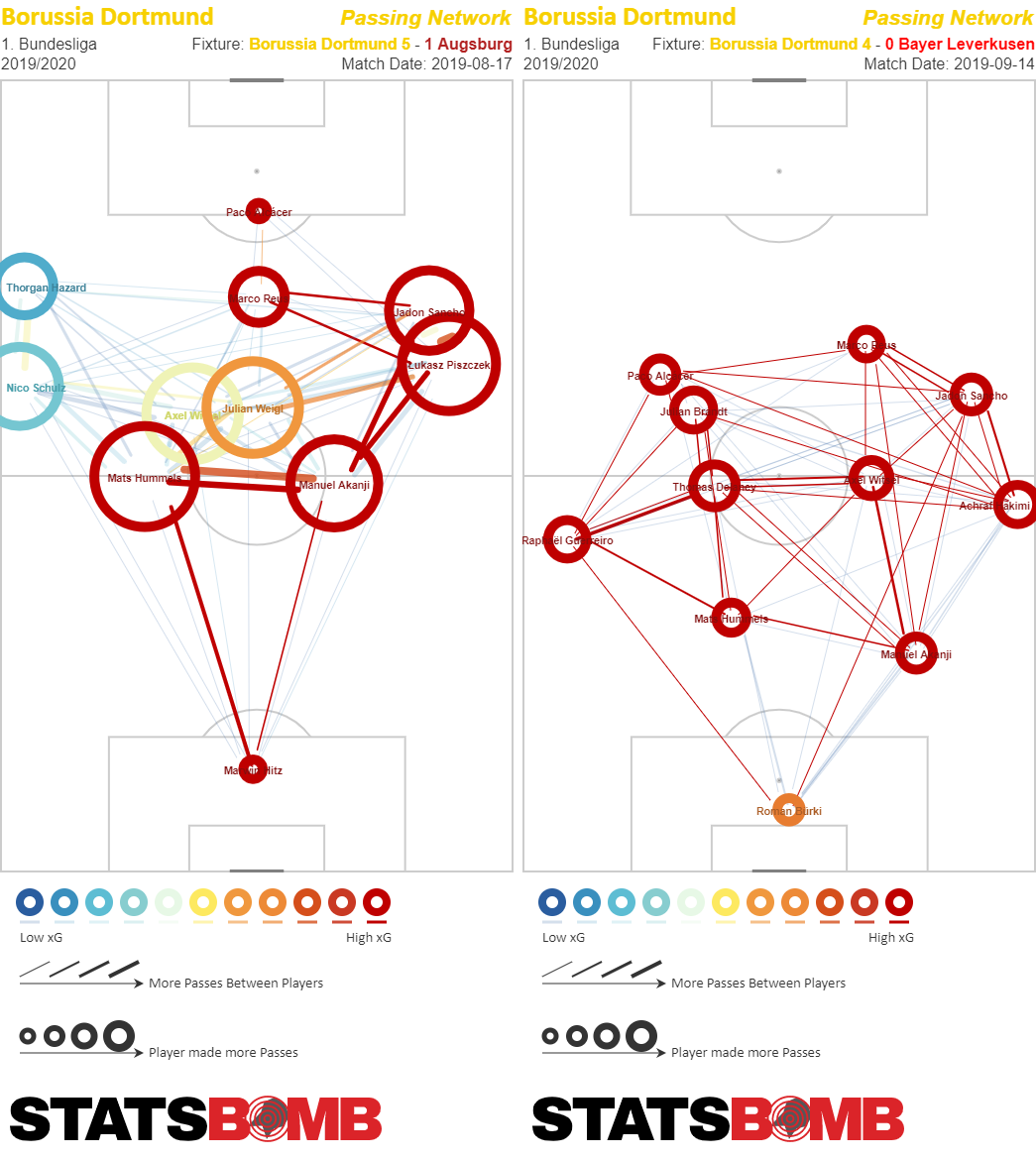

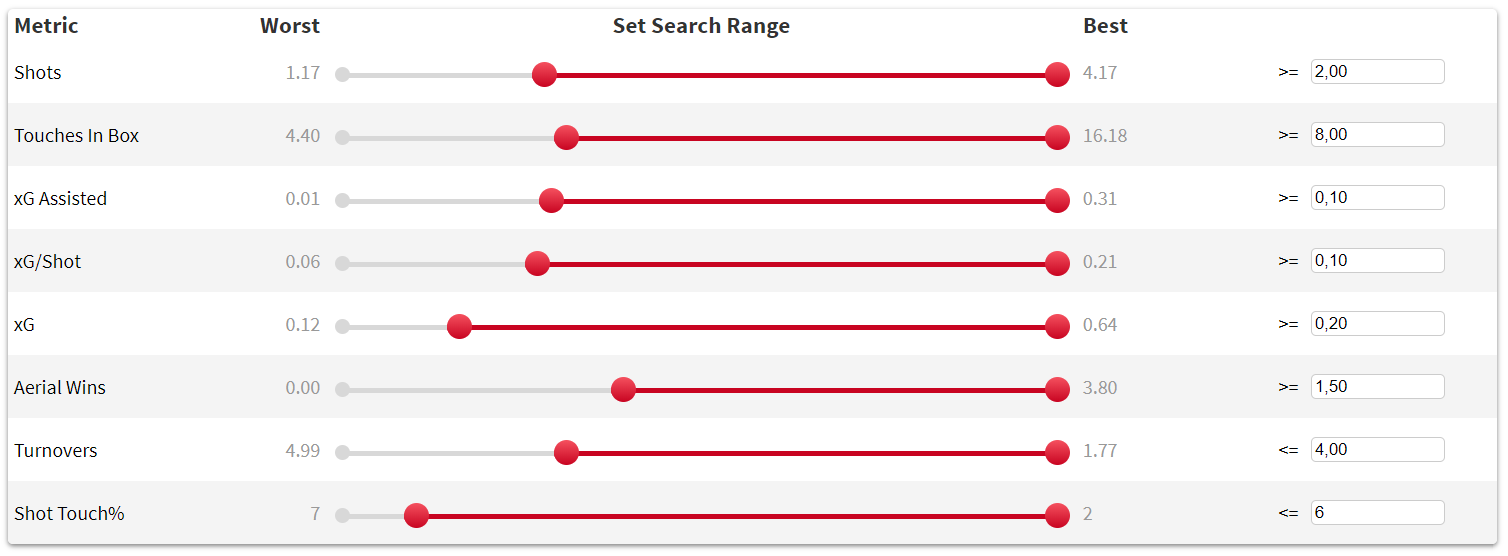

Götze and Alcácer could hardly be any more different from one another—even if we dismiss the context of the games. This holds especially true for the way they integrate themselves into general play, but also for their options in counter-attacks and fast attacks.  In the inaugural league match of the season, BVB played quite asymmetrically, with Alcácer as a central target player. Against Leverkusen, on the other hand, Alcácer moved toward the left side frequently, especially in a tough first half. He received passes and tried to carry on Dortmund’s counter-attacking. This is Alcácer’s big strength: He is neither a classic penalty-box striker (despite his eye for goal and intelligent positioning), nor is he a true counter-attacker (despite his quickness and evasive movement). He unites both elements very well, making him the perfect striker for BVB, seeing as they have to adapt their playing style on occasion because of their vulnerability against a high press. An Alcácer copy? This short analysis then poses the question of whether Dortmund should make an effort in the coming summer to sign a “second” Paco Alcácer. The statistical numbers from this and last season show that the Bundesliga have a few strikers that would fit that bill and have a statistical resemblance of roughly 80%. First, Kevin Volland, who has transformed into a central target player recently but can still play through the half-space given his career history. Peter Bosz has used him on the left wing five times this season, from where Volland moved inwards frequently and always attempted to create proximity to the central striker. Volland can perform similarly evasive movements in a counter-attacking scheme to those of Alcácer and carry on the attack. Another tactically flexible striker who falls in the statistical category of Alcácer is Andrej Kramarić. In the current campaign, a knee injury has limited the Croatian to only two appearances. But in recent years at Hoffenheim, he has regularly proved he can play his part in the attack both from the centre and from a position in the left half-space. He distinguishes himself from Volland insofar as he generates more high-quality shooting attempts, while at the same time playing with more risk, especially when deployed up front, losing the ball more frequently than Volland. The third striker in this equation is Alfreð Finnbogason, but he cannot be an option for Dortmund based on his age, career to this point and susceptibility to injury.

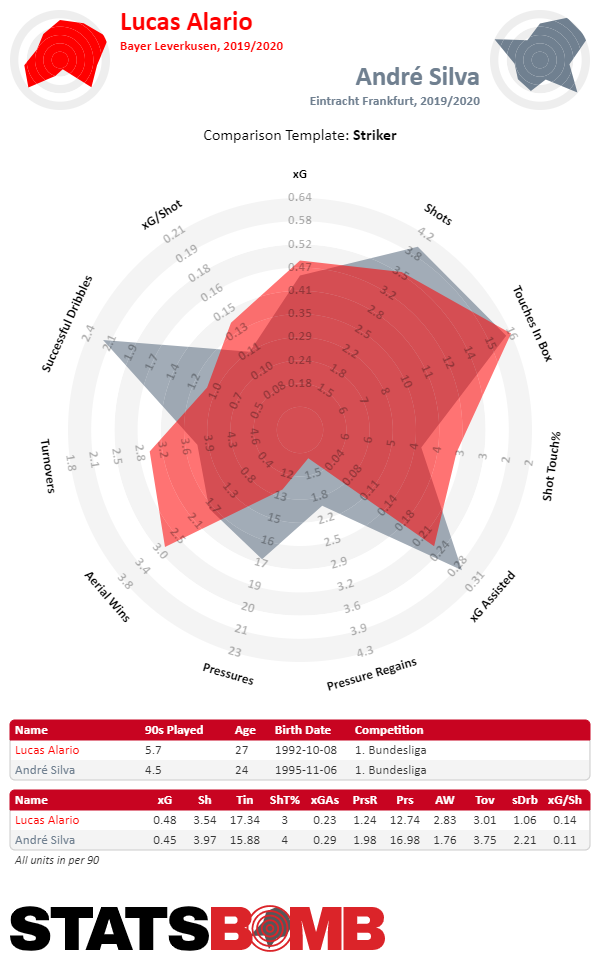

In the inaugural league match of the season, BVB played quite asymmetrically, with Alcácer as a central target player. Against Leverkusen, on the other hand, Alcácer moved toward the left side frequently, especially in a tough first half. He received passes and tried to carry on Dortmund’s counter-attacking. This is Alcácer’s big strength: He is neither a classic penalty-box striker (despite his eye for goal and intelligent positioning), nor is he a true counter-attacker (despite his quickness and evasive movement). He unites both elements very well, making him the perfect striker for BVB, seeing as they have to adapt their playing style on occasion because of their vulnerability against a high press. An Alcácer copy? This short analysis then poses the question of whether Dortmund should make an effort in the coming summer to sign a “second” Paco Alcácer. The statistical numbers from this and last season show that the Bundesliga have a few strikers that would fit that bill and have a statistical resemblance of roughly 80%. First, Kevin Volland, who has transformed into a central target player recently but can still play through the half-space given his career history. Peter Bosz has used him on the left wing five times this season, from where Volland moved inwards frequently and always attempted to create proximity to the central striker. Volland can perform similarly evasive movements in a counter-attacking scheme to those of Alcácer and carry on the attack. Another tactically flexible striker who falls in the statistical category of Alcácer is Andrej Kramarić. In the current campaign, a knee injury has limited the Croatian to only two appearances. But in recent years at Hoffenheim, he has regularly proved he can play his part in the attack both from the centre and from a position in the left half-space. He distinguishes himself from Volland insofar as he generates more high-quality shooting attempts, while at the same time playing with more risk, especially when deployed up front, losing the ball more frequently than Volland. The third striker in this equation is Alfreð Finnbogason, but he cannot be an option for Dortmund based on his age, career to this point and susceptibility to injury.  These criteria, used for last and this season, produces four results: André Silva, Gonçalo Paciência, Lucas Alario and, naturally, Robert Lewandowski. For Paciência, the result only refers to last season, in which he played only sparingly. In the current campaign, he would fall off the radar due to too many losses of possession, but he remains an interesting alternative to Silva and Alario regardless.

These criteria, used for last and this season, produces four results: André Silva, Gonçalo Paciência, Lucas Alario and, naturally, Robert Lewandowski. For Paciência, the result only refers to last season, in which he played only sparingly. In the current campaign, he would fall off the radar due to too many losses of possession, but he remains an interesting alternative to Silva and Alario regardless.  Those two, in turn, differ from one another in the way they participate in general play. Silva is more involved in situations in which he is not the one to look for the shooting attempt, rather setting up players from a zone ahead of the penalty box. Of course, this is also down to the playing style of Eintracht Frankfurt, in whose 3-4-1-2 or 3-5-2 the ball-near striker drops deeper during attacks along the wings. Particularly when playing over Filip Kostić, Silva drops back a bit, meaning he is not the furthest-most target player. Alario, on the other hand, constitutes a classic spearhead in the Bayer Leverkusen system, playing a role more oriented toward shooting attempts in comparison to Alcácer, which is why he is less likely to take part in the prepared combination play, bus also why he loses possession in the final third less often.

Those two, in turn, differ from one another in the way they participate in general play. Silva is more involved in situations in which he is not the one to look for the shooting attempt, rather setting up players from a zone ahead of the penalty box. Of course, this is also down to the playing style of Eintracht Frankfurt, in whose 3-4-1-2 or 3-5-2 the ball-near striker drops deeper during attacks along the wings. Particularly when playing over Filip Kostić, Silva drops back a bit, meaning he is not the furthest-most target player. Alario, on the other hand, constitutes a classic spearhead in the Bayer Leverkusen system, playing a role more oriented toward shooting attempts in comparison to Alcácer, which is why he is less likely to take part in the prepared combination play, bus also why he loses possession in the final third less often.  Silva, Alario and even Paciência offer the physical qualities needed for the proposed profile. The last two seem a tad stronger in the air, which can become apparent in pressure situations within the penalty box. Silva and Alario also have sufficient footballing qualities to not represent a steep decline from the rest of Dortmund's attack where they would only function as a last-resort target player and force BVB into attacking with nine instead of ten outfield players. The preferred option remains an attack with Alcácer. But for more tactical flexibility, for example, to increase the success rate of attacks over the wings or to play against an opponent's isolated high press, one of these strikers could help BVB.

Silva, Alario and even Paciência offer the physical qualities needed for the proposed profile. The last two seem a tad stronger in the air, which can become apparent in pressure situations within the penalty box. Silva and Alario also have sufficient footballing qualities to not represent a steep decline from the rest of Dortmund's attack where they would only function as a last-resort target player and force BVB into attacking with nine instead of ten outfield players. The preferred option remains an attack with Alcácer. But for more tactical flexibility, for example, to increase the success rate of attacks over the wings or to play against an opponent's isolated high press, one of these strikers could help BVB.  Another name, and one that would fit the category of “Fantasy Manager”, is Erling Håland of Salzburg, arguably the most wanted young striker in Europe. His fit at BVB is not an obvious one, however. While Håland is outstanding in terms of offensive productivity, a few smaller technical mistakes in his ball-handling abilities leave some question marks. Salzburg's playing style is predicated on a certain verticality and openness to risk, so a few losses of possession at the top of the formation are not a big problem. However, Håland does not seem to be overly stable in sophisticated combinations. Additionally, he has to prove how far he can develop other components of his finishing game given his height and physicality — especially in the air. Right now he is probably not a realistic option for BVB, even though they have a strong need for a big talent and have the ambition to attract this kind of player. You can also find

Another name, and one that would fit the category of “Fantasy Manager”, is Erling Håland of Salzburg, arguably the most wanted young striker in Europe. His fit at BVB is not an obvious one, however. While Håland is outstanding in terms of offensive productivity, a few smaller technical mistakes in his ball-handling abilities leave some question marks. Salzburg's playing style is predicated on a certain verticality and openness to risk, so a few losses of possession at the top of the formation are not a big problem. However, Håland does not seem to be overly stable in sophisticated combinations. Additionally, he has to prove how far he can develop other components of his finishing game given his height and physicality — especially in the air. Right now he is probably not a realistic option for BVB, even though they have a strong need for a big talent and have the ambition to attract this kind of player. You can also find