We’ve reached the 21st century in this week’s edition of our history of the European Cup, as we take a look at the 2009 final between Barcelona and Manchester United. Nearly a decade and a half on from the last one we covered, this is now recognisably the football of the modern age.

This is the fifth entry in our series.

We’ve already analysed:

- 1960: Real Madrid 7 - 3 Eintracht Frankfurt

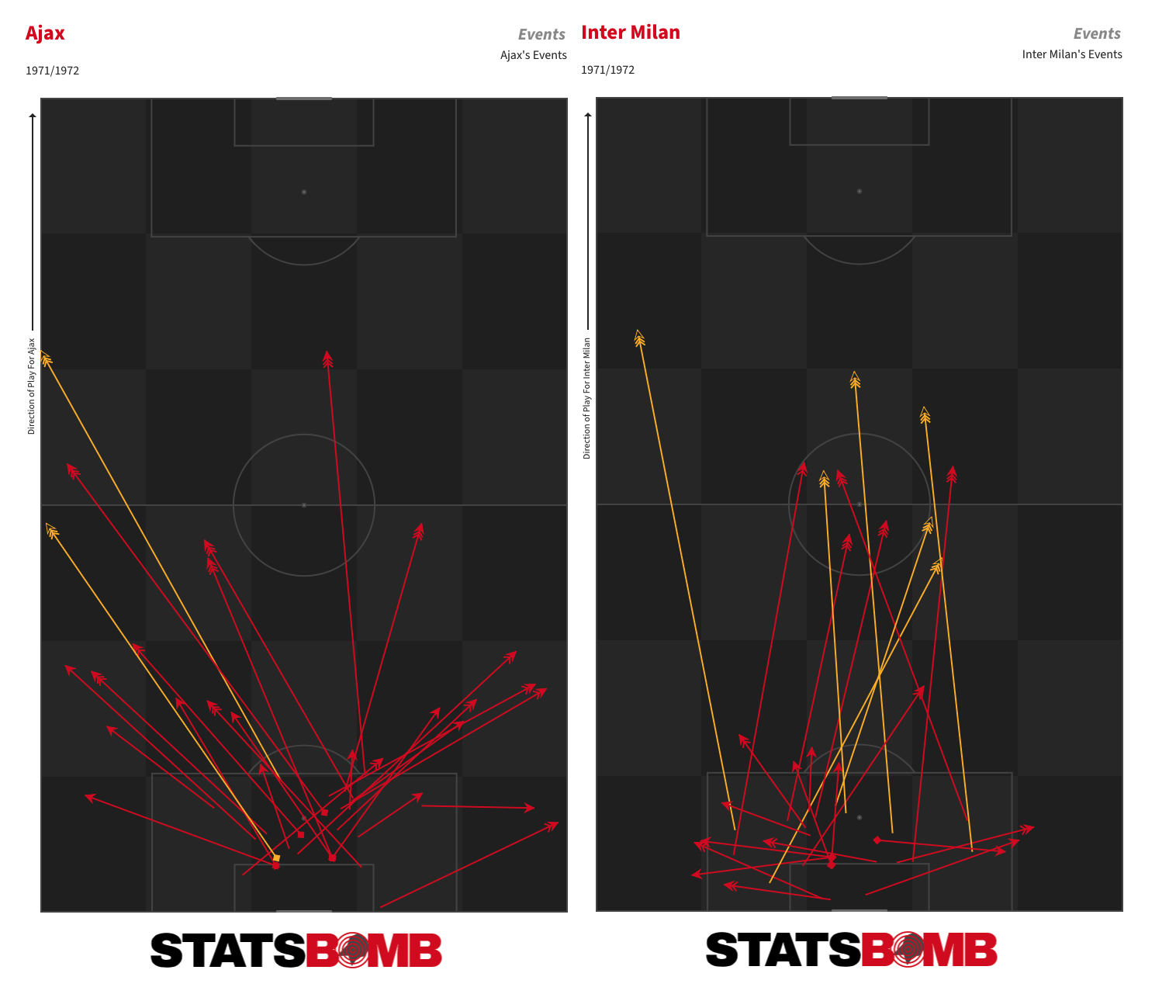

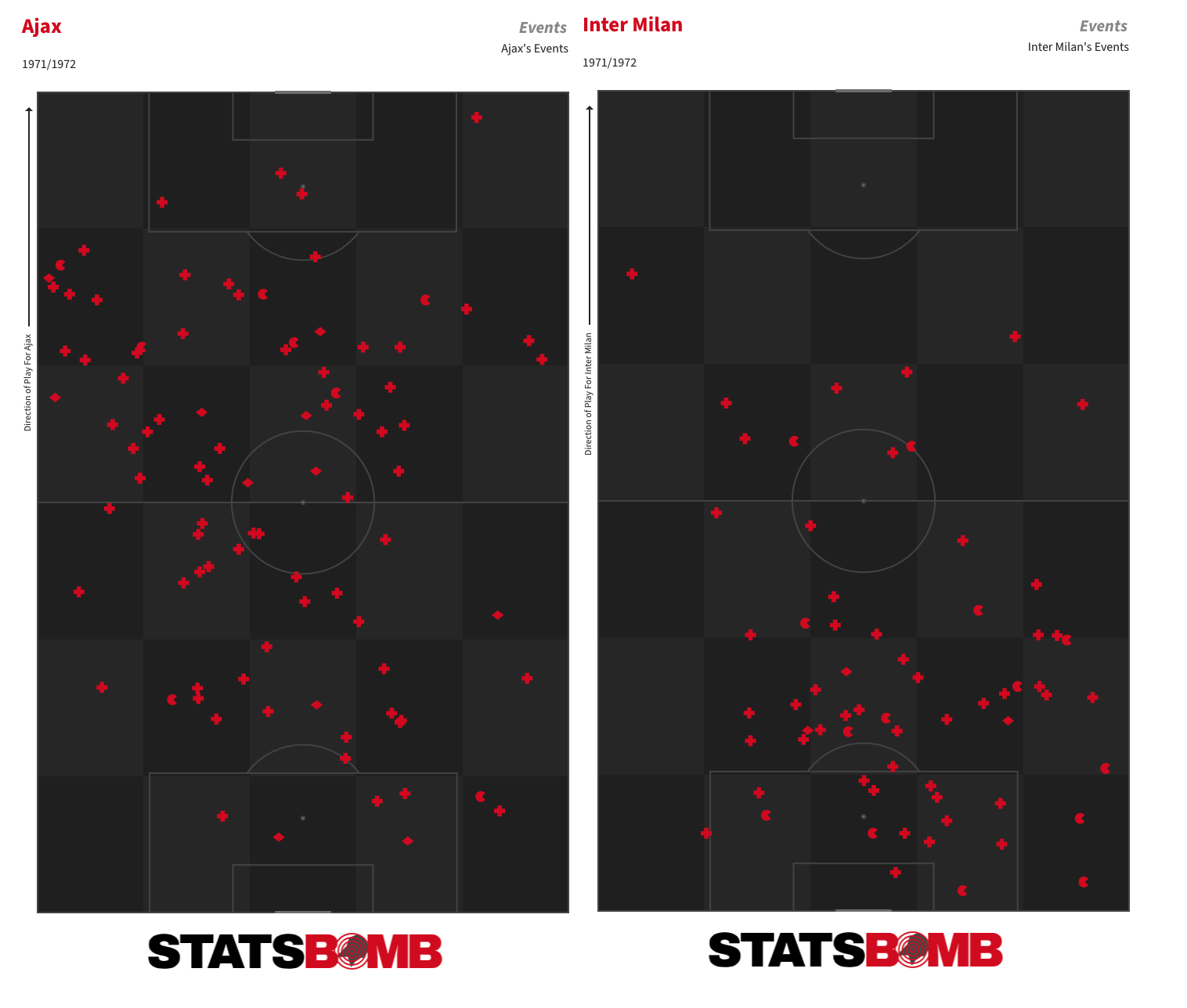

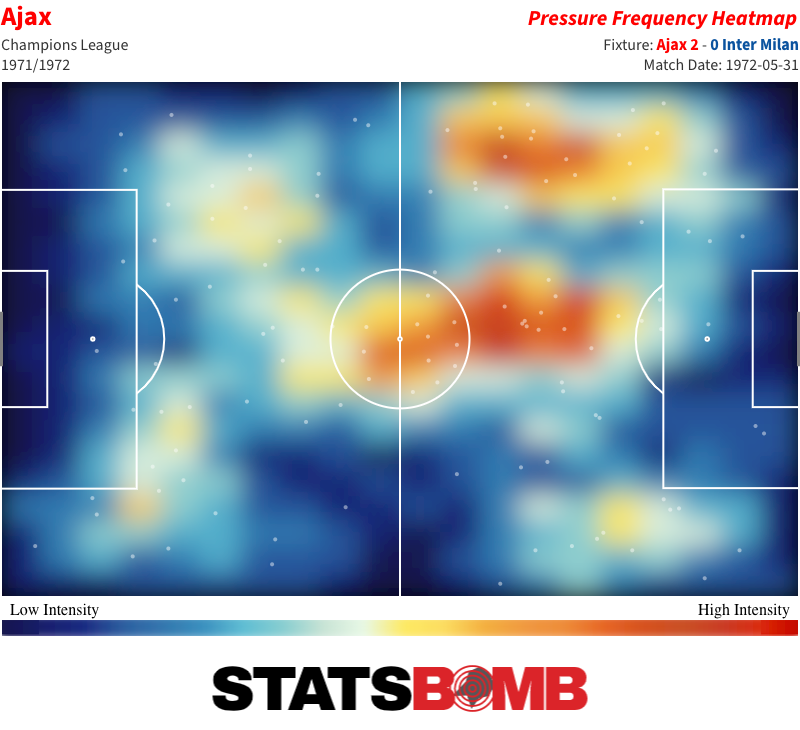

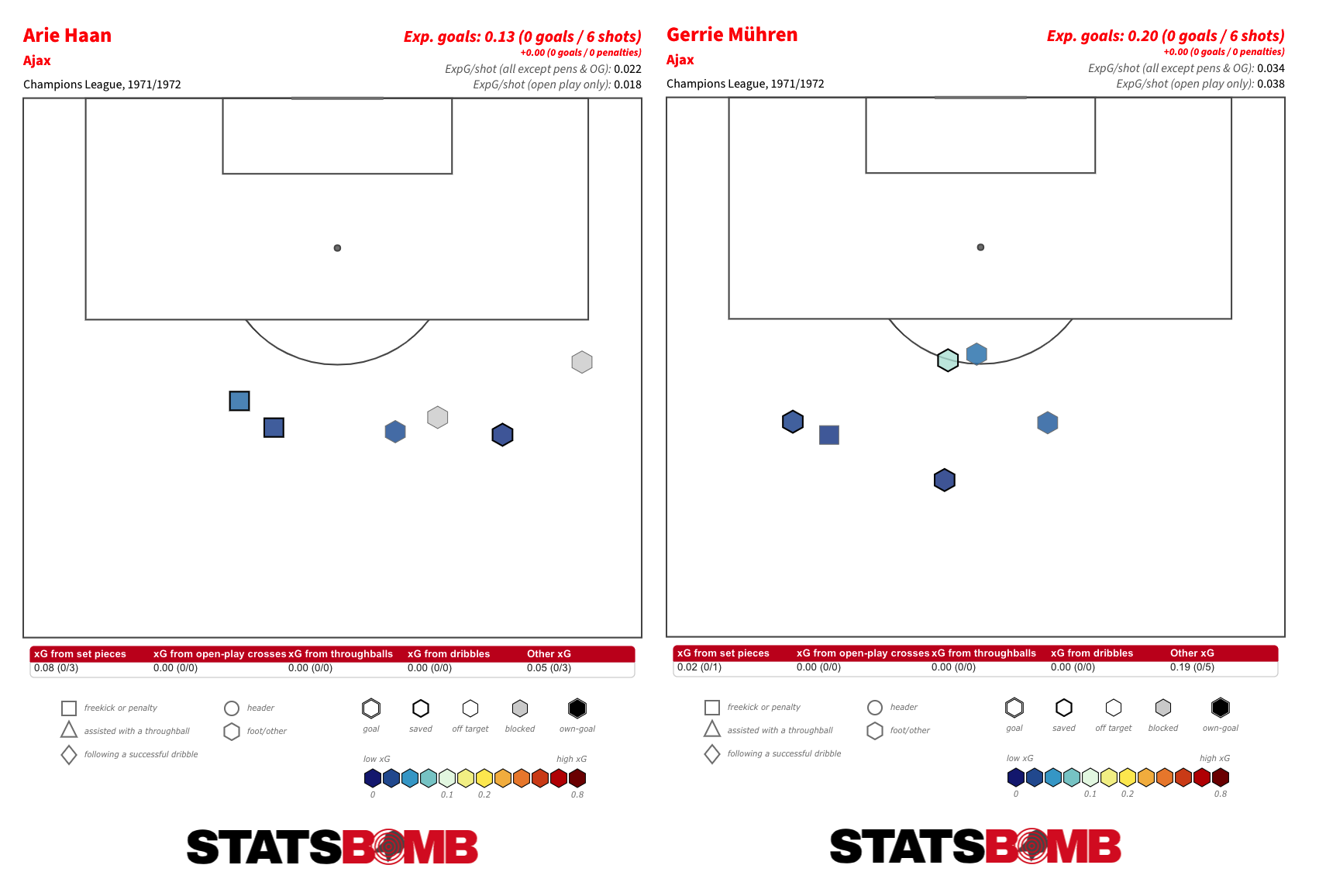

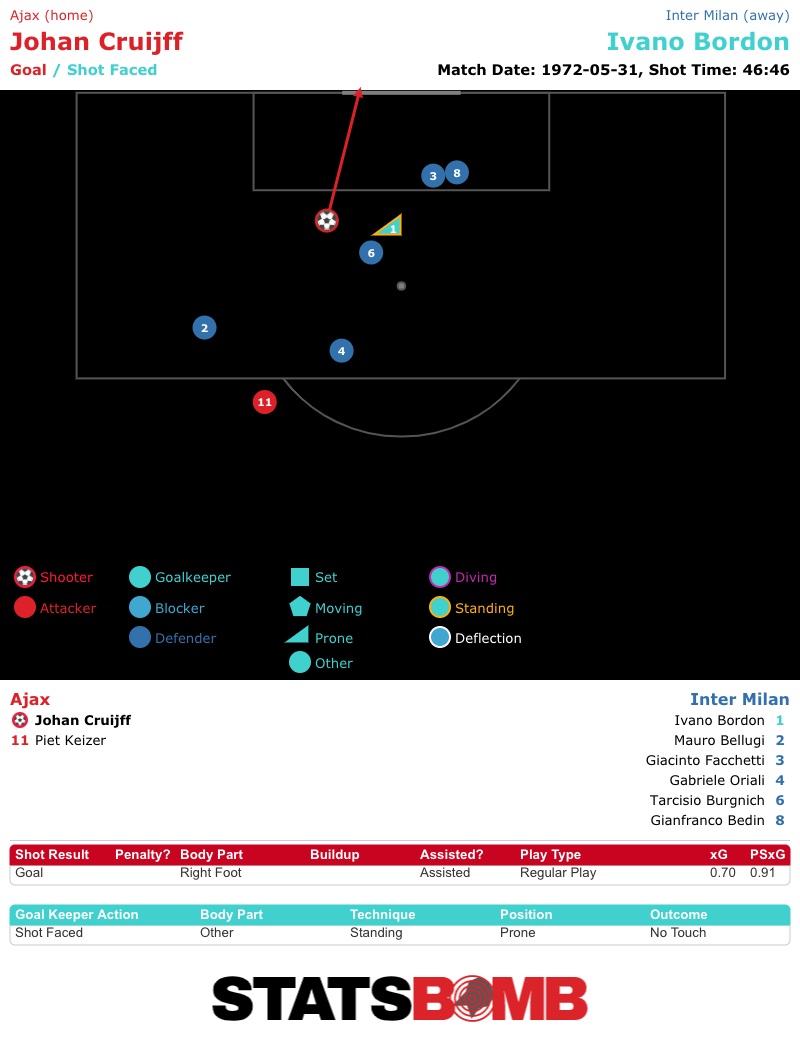

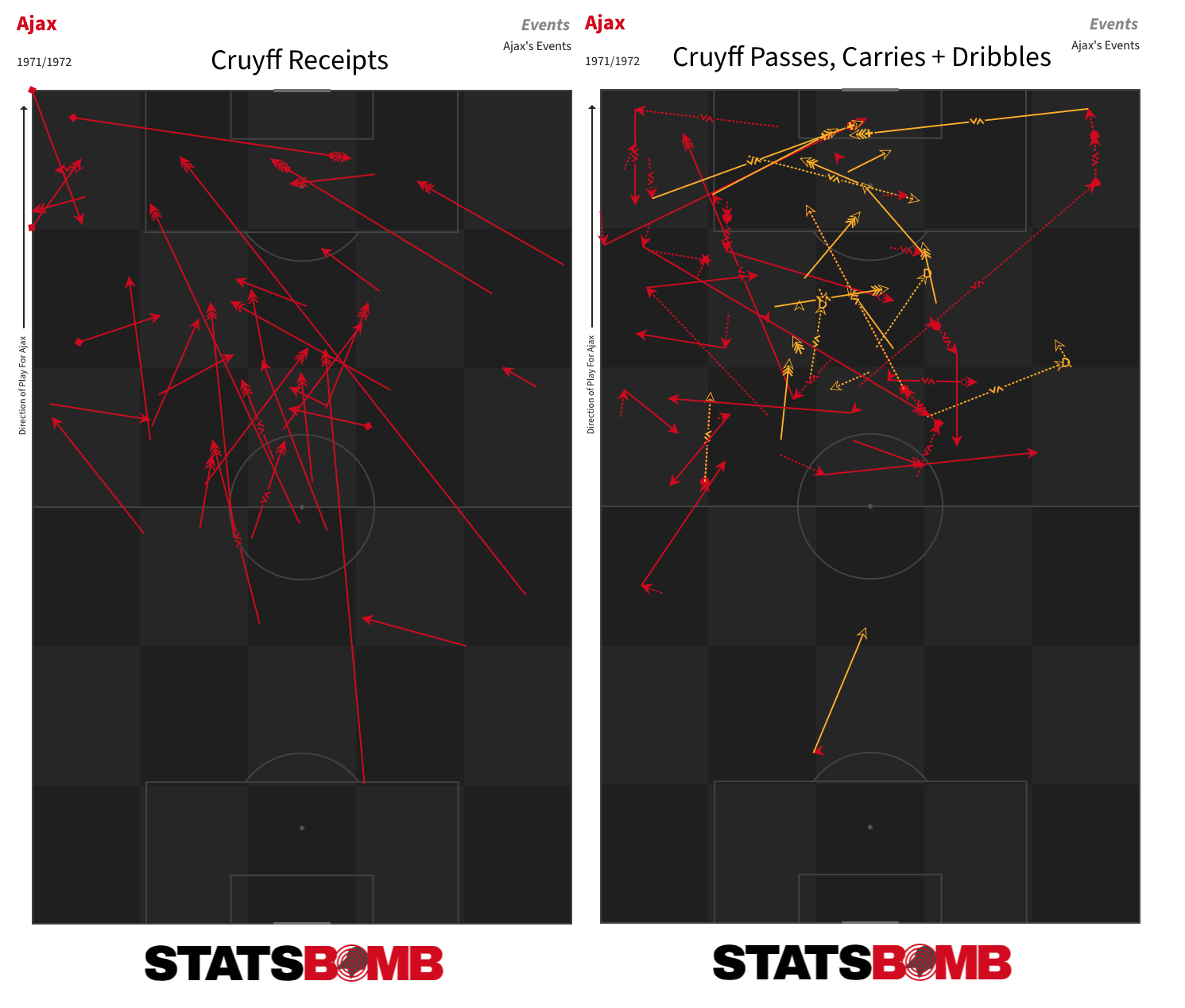

- 1972: Ajax 2 - 0 Inter Milan

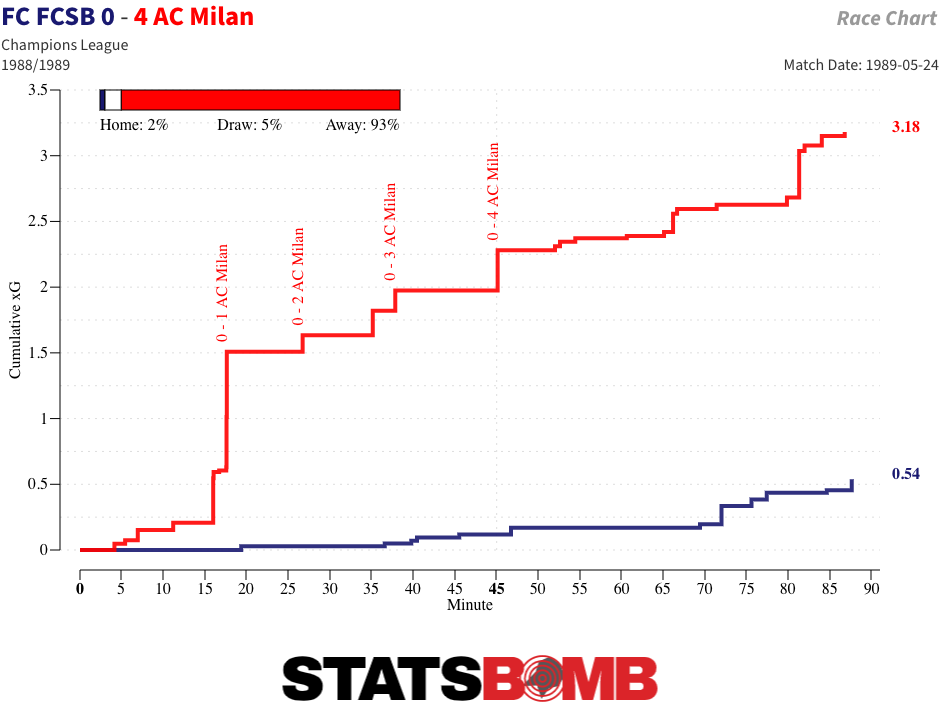

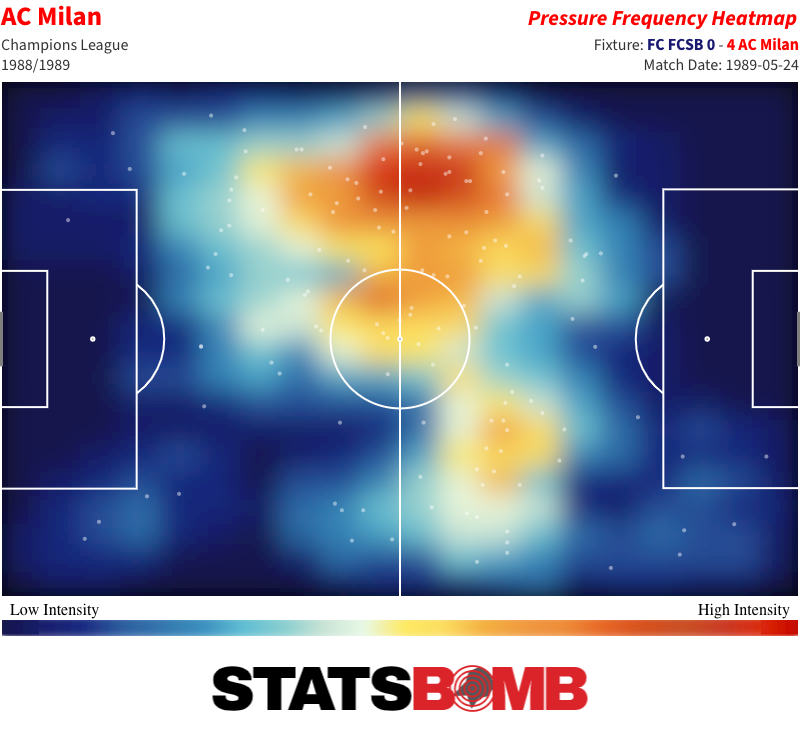

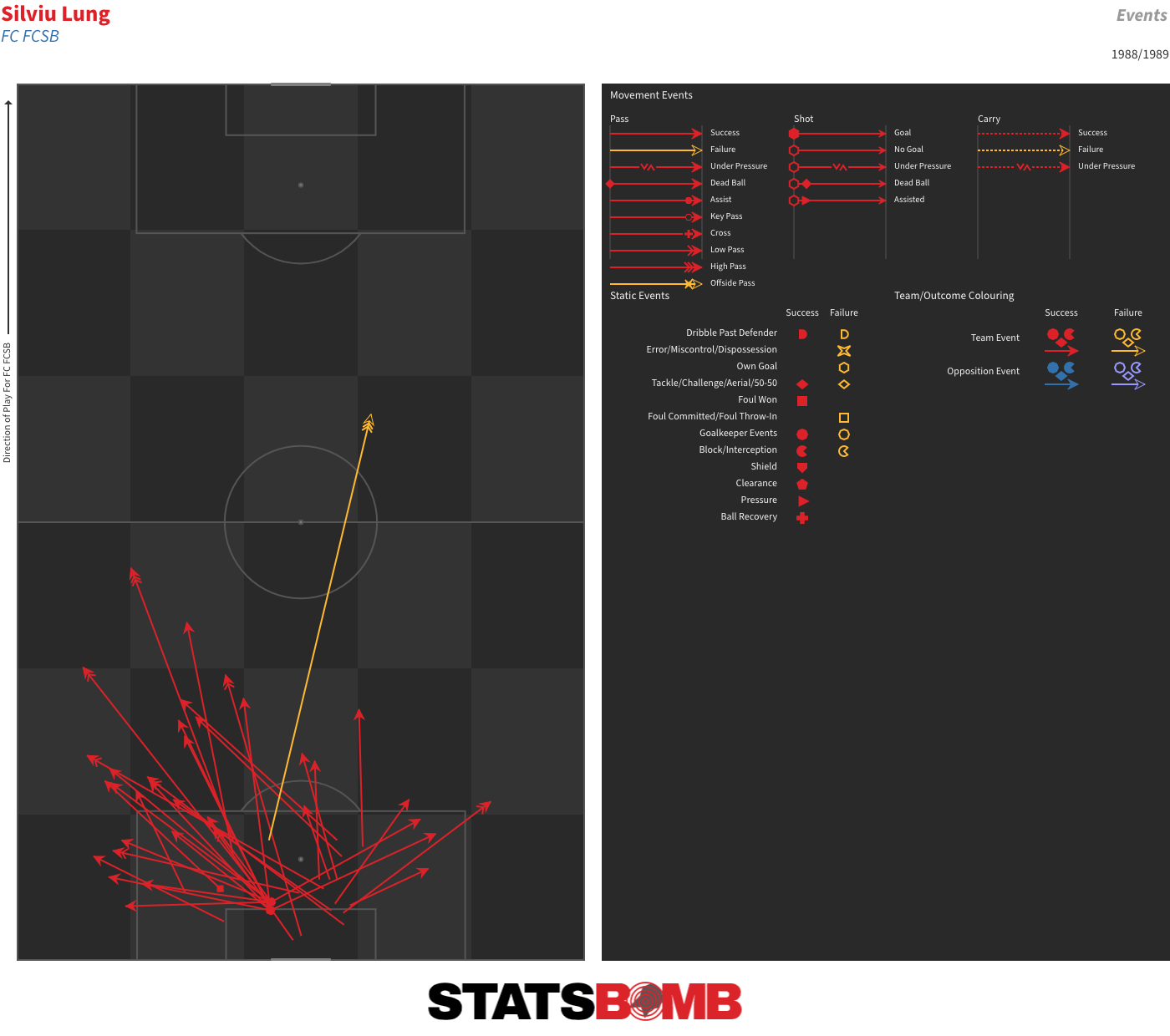

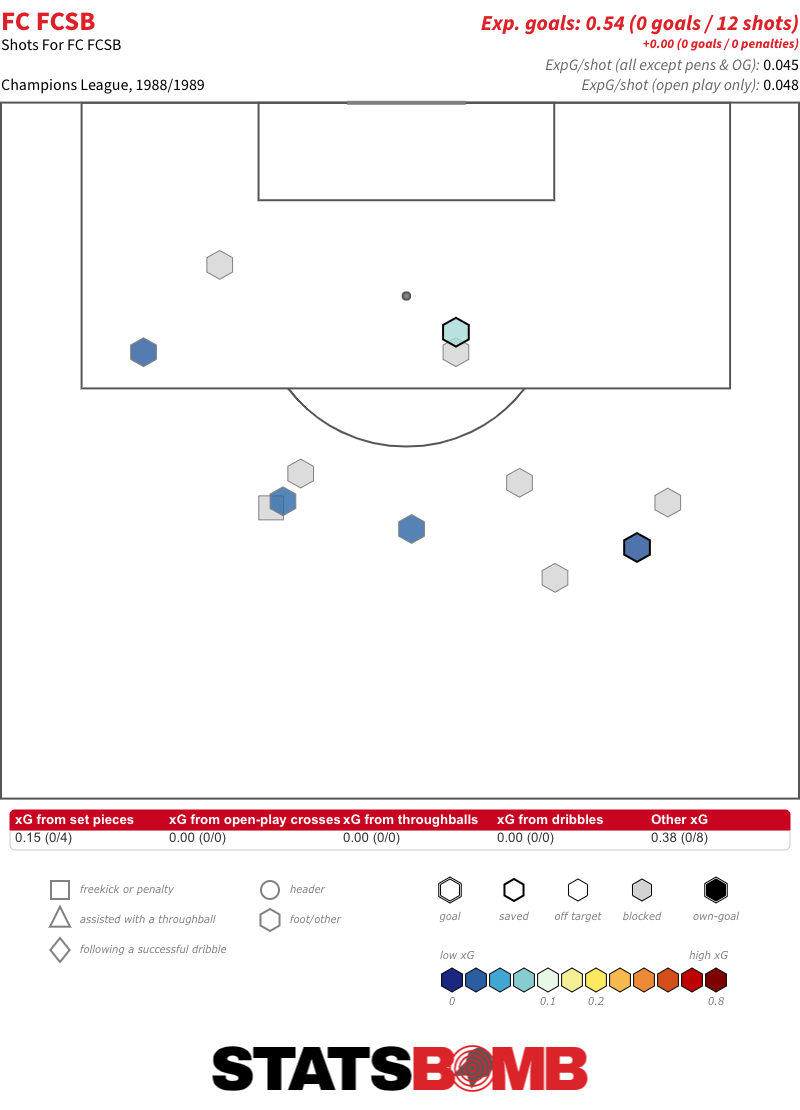

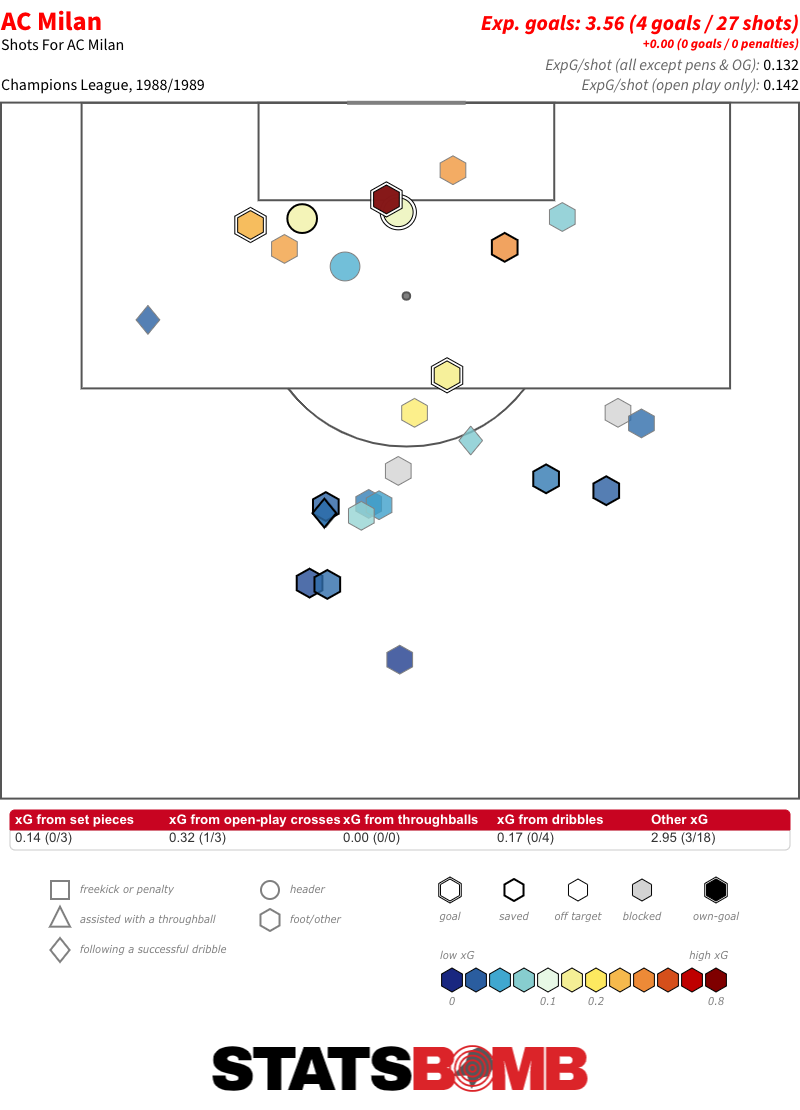

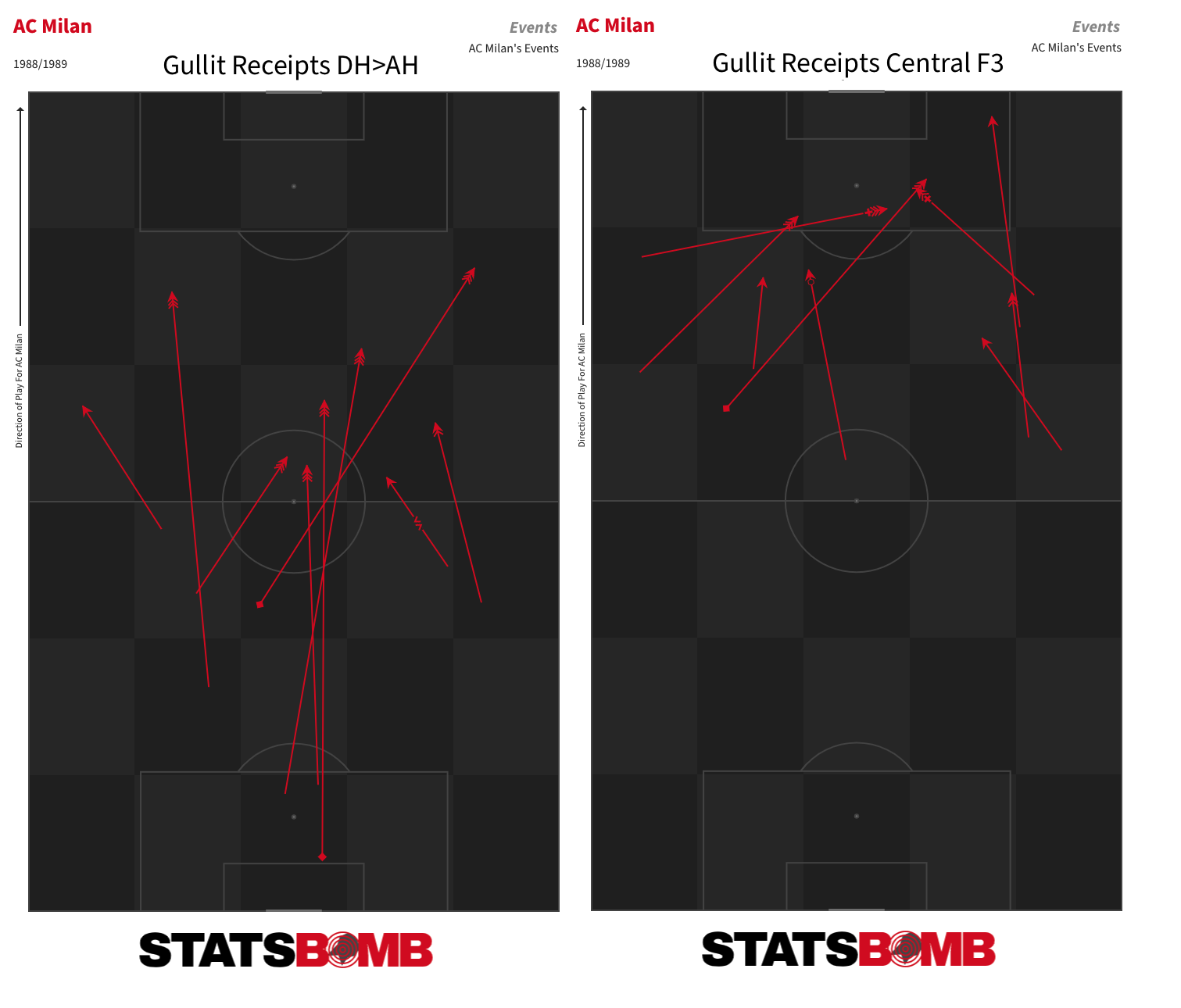

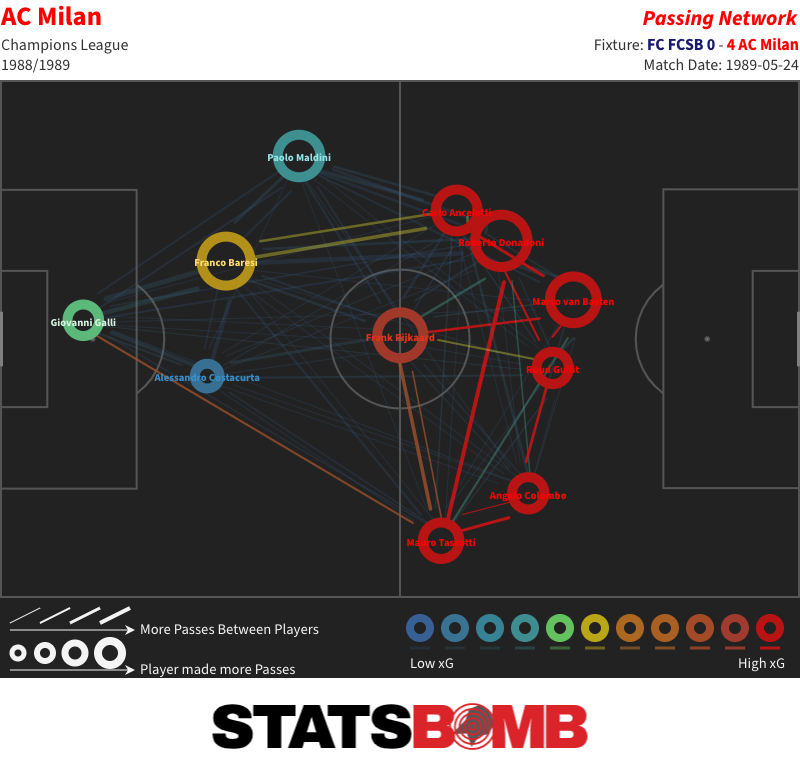

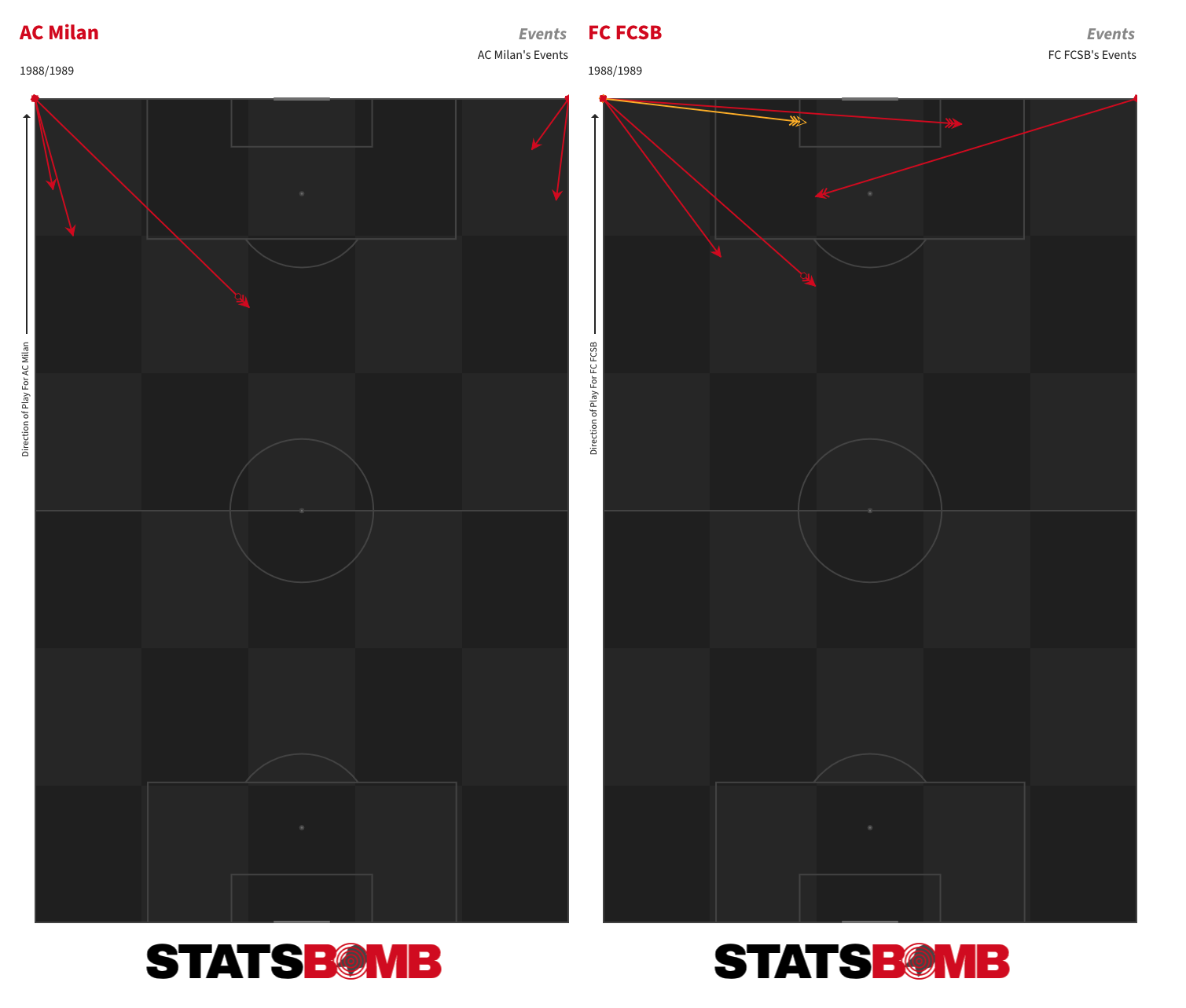

- 1989: AC Milan 4 - 0 Steaua Bucharest

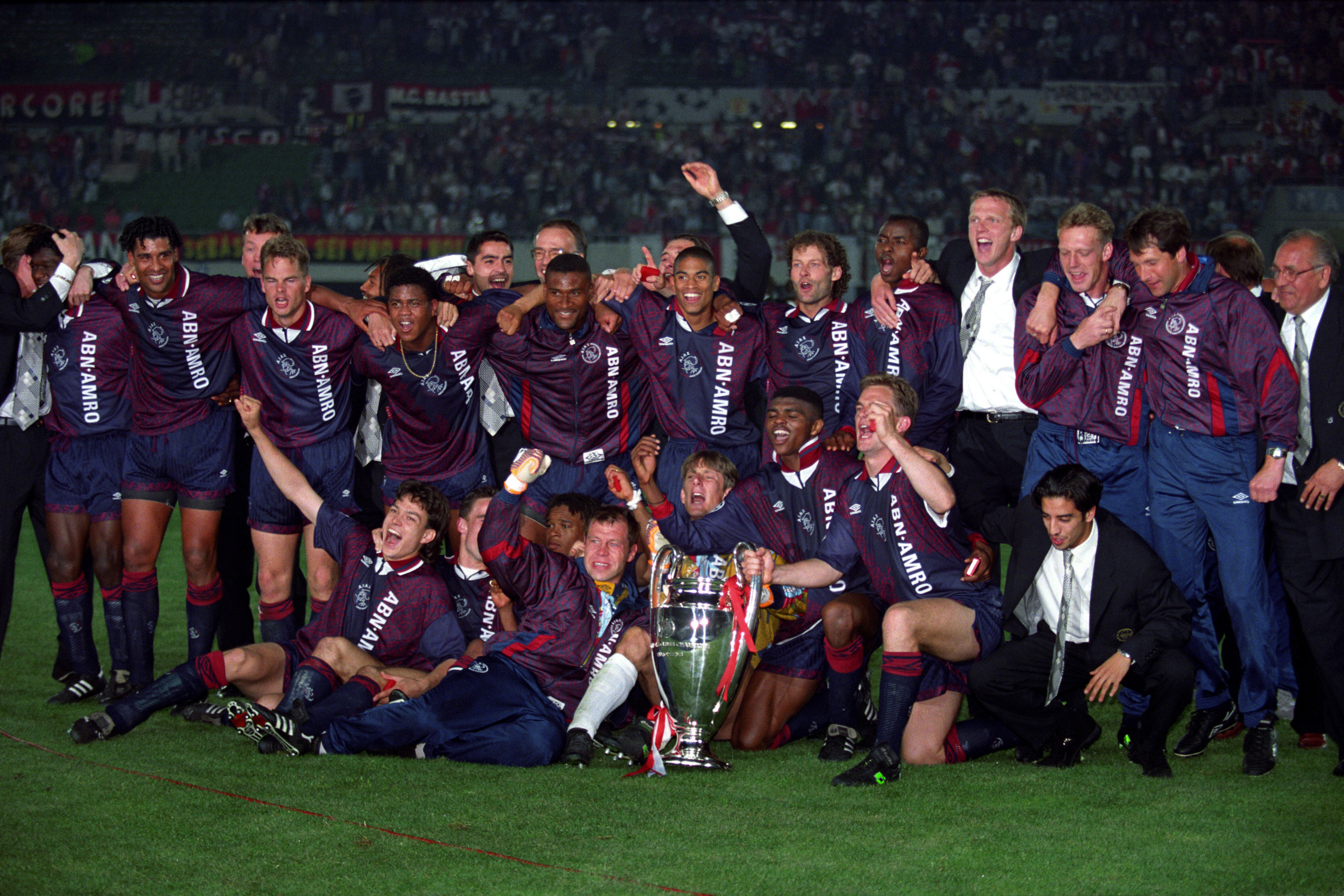

There were some familiar faces from some of those finals in this one. Manchester United goalkeeper Edwin van de Sar had started for Ajax in 1995; Patrick Kluivert, scorer of the winning goal in that match, was in amongst the Barcelona support; Johan Cruyff, scorer of both goals is the 1972 final, was watching on from a more tranquil post.

Less directly, a then 18-year-old Sir Alex Ferguson had attended the 1960 final at Hampden Park and been left spellbound by the brilliance of that Real Madrid side.

United were the competition holders following their penalty shoot out win over Chelsea in the 2008 final, and had just wrapped up the Premier League title. Barcelona, in Pep Guardiola’s first season as head coach, had already secured a domestic double.

United Start Strong, Barcelona Gain Control

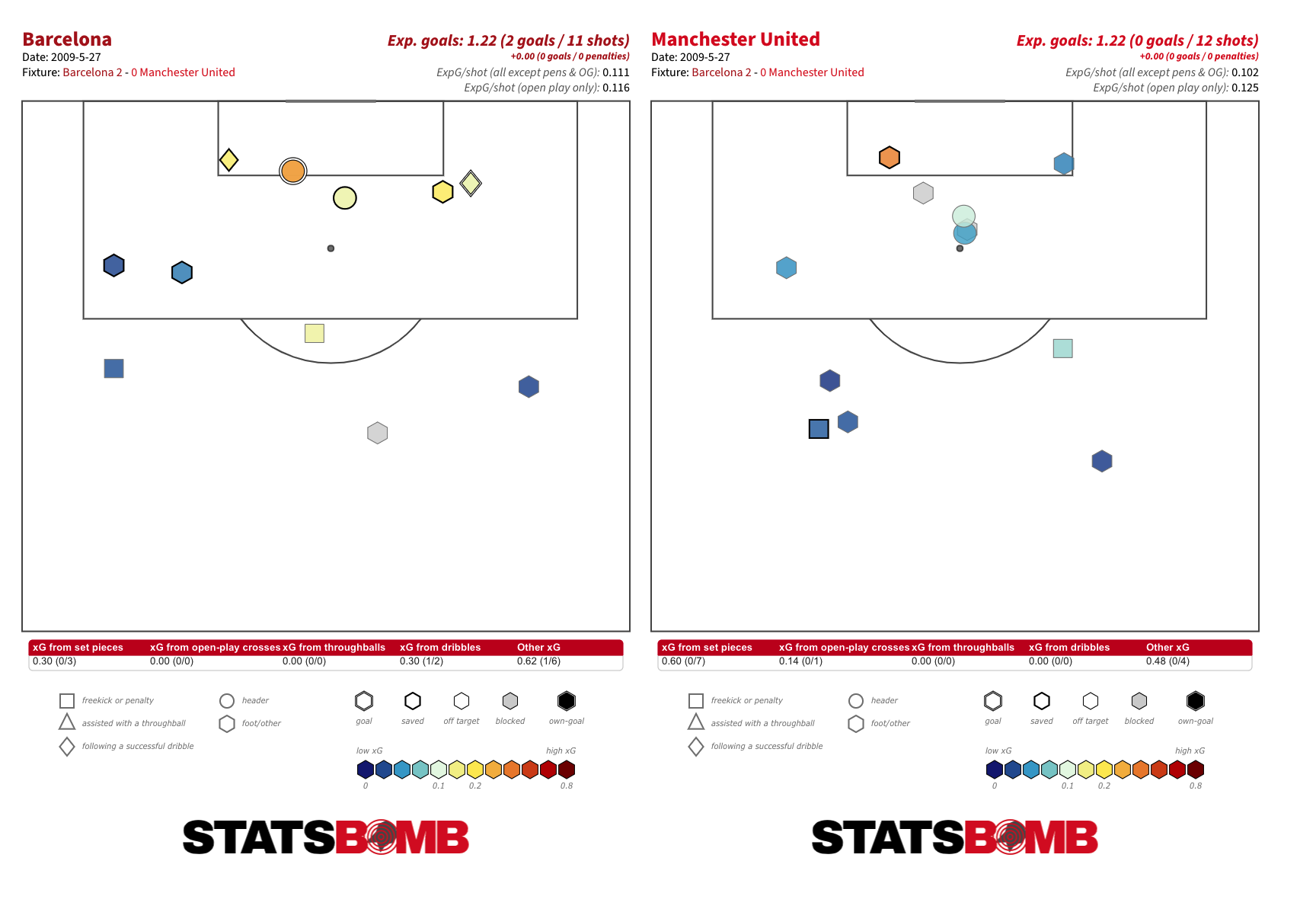

United were considered the pre-match favourites (marginally by the bookmakers; more robustly by the more insulated members of the British sporting press), and began on the front foot with a series of quick-fire attacks that saw them register five shots within the opening nine minutes. Only a sliding block from Gerard Piqué prevented Park Ji-Sung from turning in the rebound from a parried Cristiano Ronaldo free-kick.

With both of their regular full-backs Dani Alves and Eric Abidal suspended, and central defensive option Rafael Márquez also out injured, Barcelona fielded a makeshift backline that featured Yaya Touré alongside Piqué in the centre of defence. Touré played as if he was still in midfield, stepping out, shadowing opponents and taking time to regain his position. He settled in a bit as the match went on, but he was still regularly found in advance of his defensive colleagues.

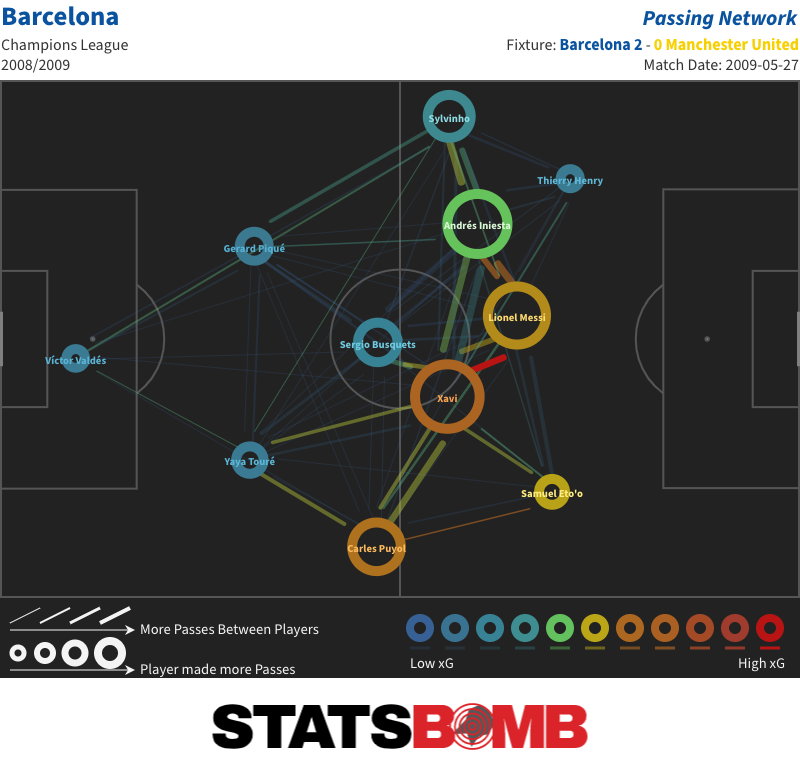

Not that it mattered all that much because after that initial United flurry, Barcelona took control of the match off the back of a goal from Samuel Eto’o. Xavi, Andres Iniesta and Lionel Messi combined through the centre for the first time, Iniesta moved the ball on to Eto’o, and he skipped inside Nemanja Vidic before prodding home in the 10th minute of play.

As in Barcelona’s 6-2 victory over Real Madrid in the league earlier the same month (a match we covered in detail as part of our series on Messi’s evolution), Messi lined up here as a False 9, with Eto’o and Thierry Henry either side of him as wide forwards.

Just as in that match, it was Barcelona’s numerical superiority in the centre of pitch, with Messi essentially at the head of a diamond that had Sergio Busquets at its base, that allowed them to take control. For a while, there were still spaces for United to attack in transition. Piqué obstructed Ronaldo to prevent him getting into the area from a nice diagonal pass from Ryan Giggs. But those opportunities all but disappeared as Barcelona started to string together long sequences of controlled and progressive possession.

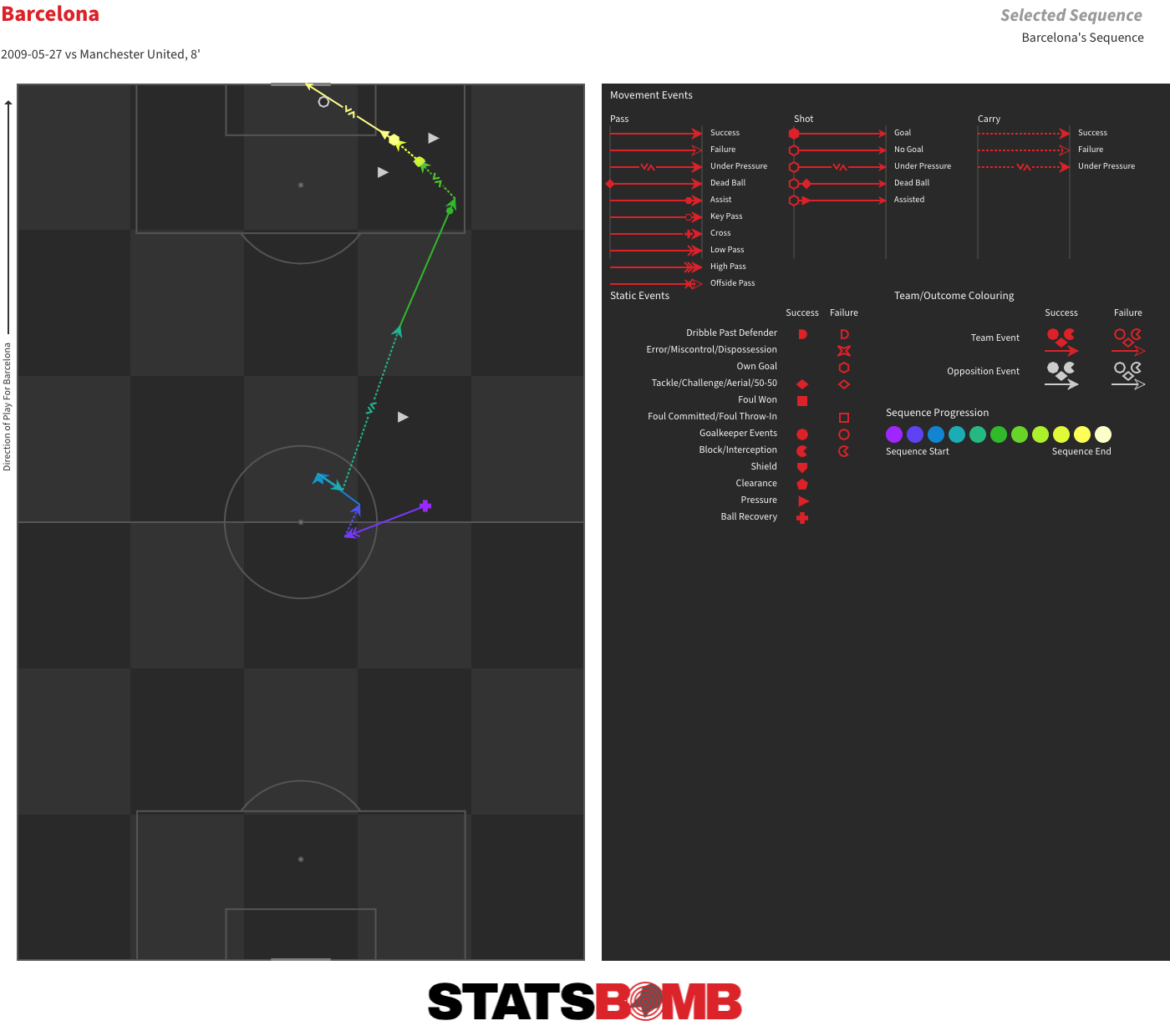

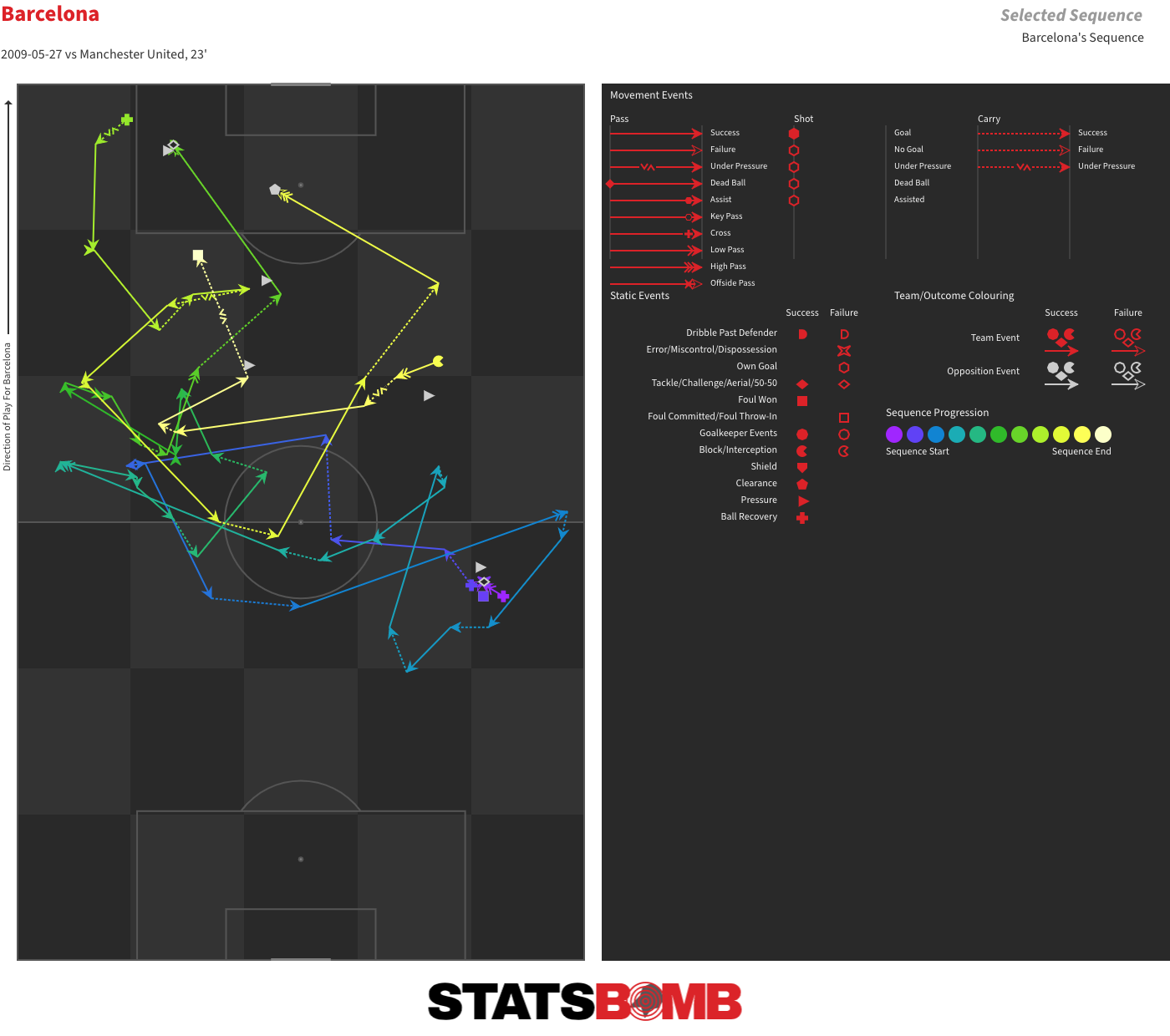

This sequence, which ended with a foul on Iniesta, acts as a good example of the way in which Guardiola’s side were able to move the ball and keep it away from United. Iniesta, Messi and Xavi were all heavily involved.

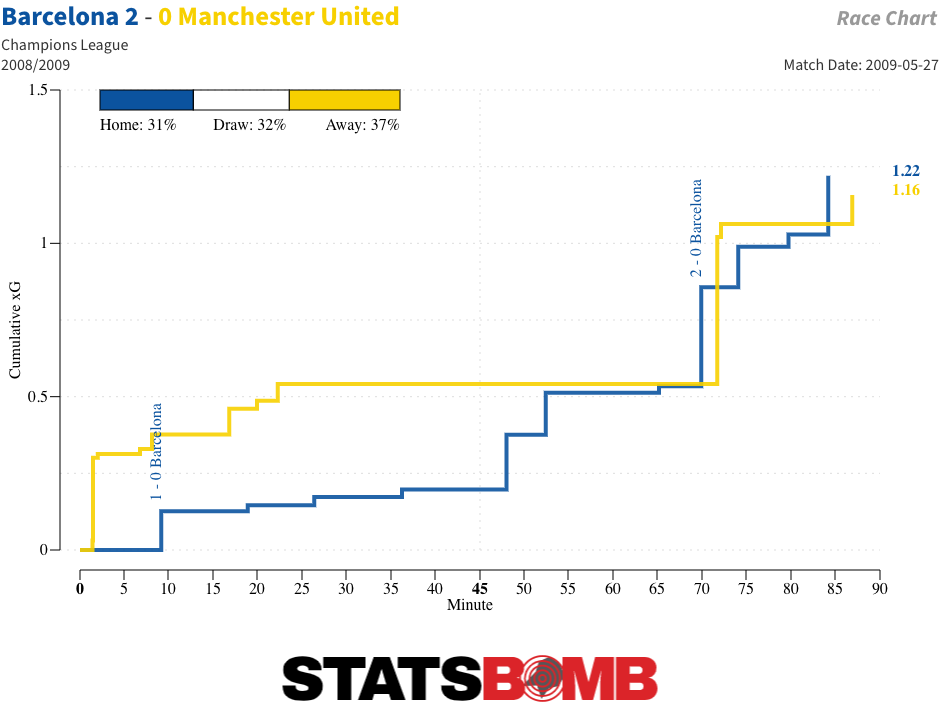

United seemed to have little response. From Barcelona’s opener until the 72nd minute, by which time Messi had doubled their lead, they mustered just three shots, including just one from open play. They got off none at all for almost 50 minutes after Ronaldo’s header wide from a corner on 23 minutes. Their offence was a flatline for over half the match despite the presence of Ronaldo, Wayne Rooney, and following his half-time introduction, Carlos Tevez.

In fact, with Tevez on the field in place of Anderson, United found it even harder to get on the ball, and Barcelona began to close in on a second goal. A lovely piece of footwork from Iniesta began a swift attack that ended in a presentable Henry chance saved; Xavi hit the post with a free-kick from the edge of the area; and then, after a lull, Messi rose to head home Xavi’s pinpoint cross and all but end the match as a contest.

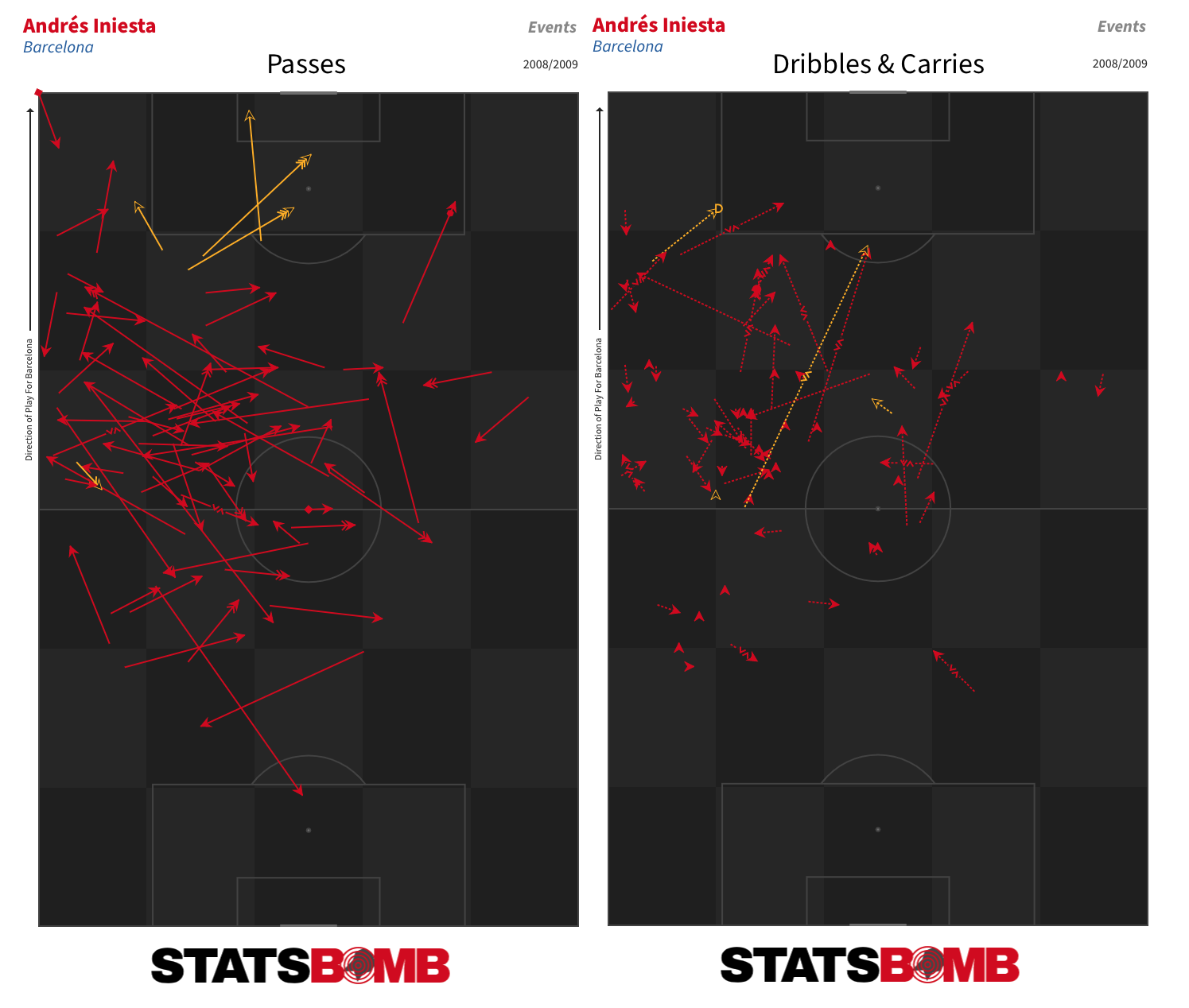

Xavi had an excellent match, as did Iniesta, whose touches left the Spanish commentators purring on multiple occasions. He was a reliable receiver under pressure, and a very able ball carrier. He advanced the ball into the final third more often than any other Barcelona player.

United came close to getting one back almost straight from kickoff following Barcelona’s second goal, but Giggs mis-kicked before Ronaldo had his low effort saved behind by Victor Valdés. From then on, they never looked likely to get back into it. Over the full course of the match, the two teams were evenly matched in terms of chances, but the timing of that first goal changed the complexion of the contest. From then on, Barcelona were in charge.

A Sign of Things to Come

There were spells in this match in which in contrast with the supple shifting of their opponents, United looked decidedly leaden-footed on the ball. While extended Barcelona possessions often eventually resulted in progress towards goal, United’s longer sequences regularly produced a steadily decreasing possibility of meaningful advancement. The counter-attack was their most dangerous weapon, and Barcelona swiftly neutered it.

This match acted as a preview of the prevailing style clash of the following years. Spain had won the European Championship the year previous, and they and Barcelona set a template that other teams were forced to adapt to. Their approach was dissected and counter-measures created. In La Liga, this 2008-09 Barcelona side still has the best expected goal difference of any in the Messi era. Subsequently, both their and Spain’s use of possession as a means of control became ever-more pronounced.

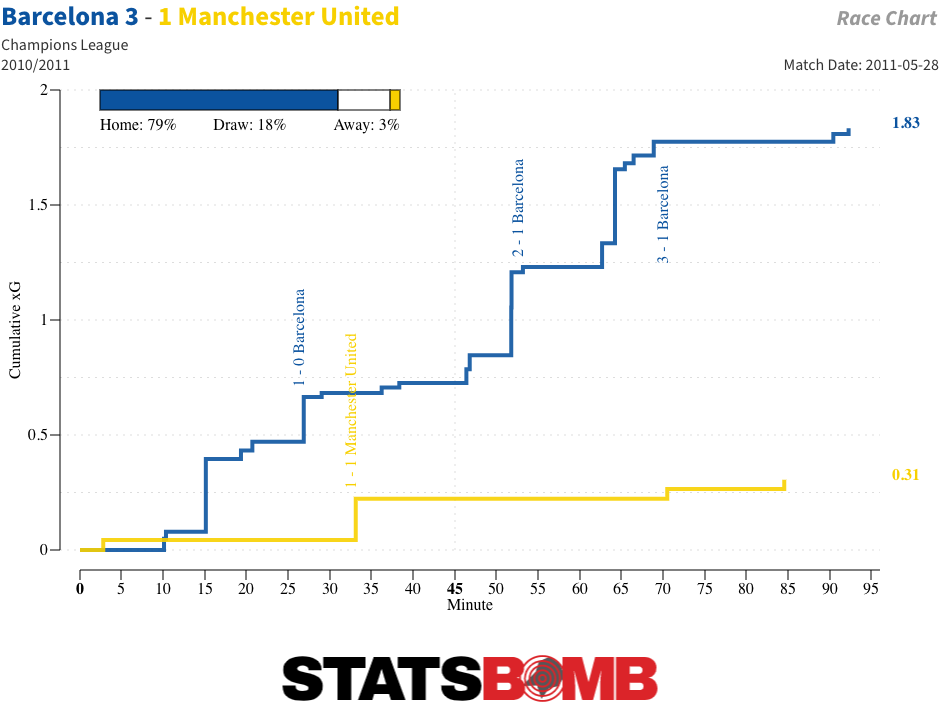

Not that the intervening couple of years and various demonstrations of ways of potentially countering Guardiola’s Barcelona did United any good. By the time the two teams met again in the 2011 final, the gap between them had widened considerably.

Shot Distances

This match felt like one from the modern era partly because it was the first we’ve seen that featured a reasonable spread of shots of decent average quality. Aside from a few speculative efforts from Ronaldo (after one of which, the sadly recently deceased Michael Robinson noted: “I’m more than happy for him to shoot from there. If it goes in, we’ll take off our hats to him, but very few are going to go in from there.”) and others, it was a set of shots of an average quality much closer to the contemporary average.

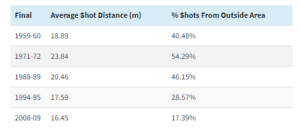

Over the last four finals of this series, there has been a consistent decrease in both the average shot distance and the percentage of efforts from outside the area.

The only outlier is the 1960 final, likely because the heaviness of the ball in that age rendered long-range efforts inefficient. The only other relatively contemporaneous match in our system is the 1953 friendly between Hungary and England at Wembley, which had an even closer average shot distance and featured a lower percentage of efforts from outside the area.

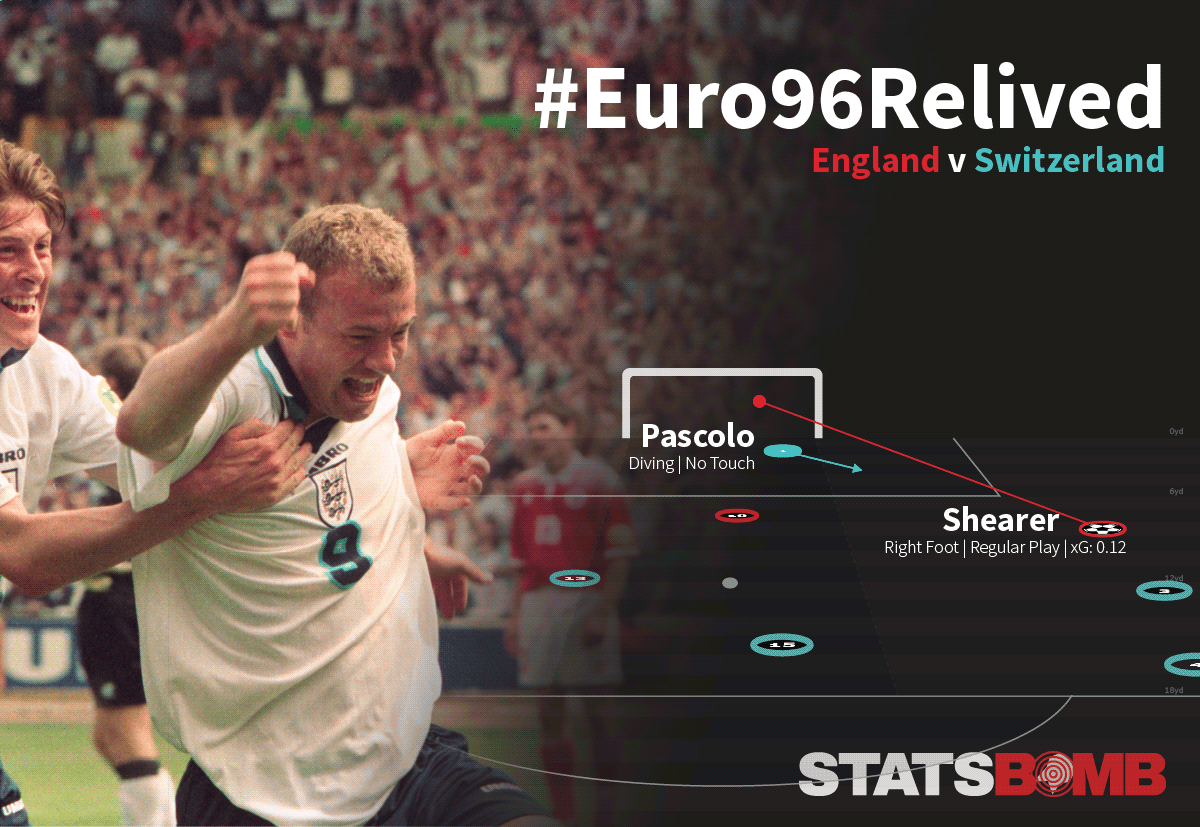

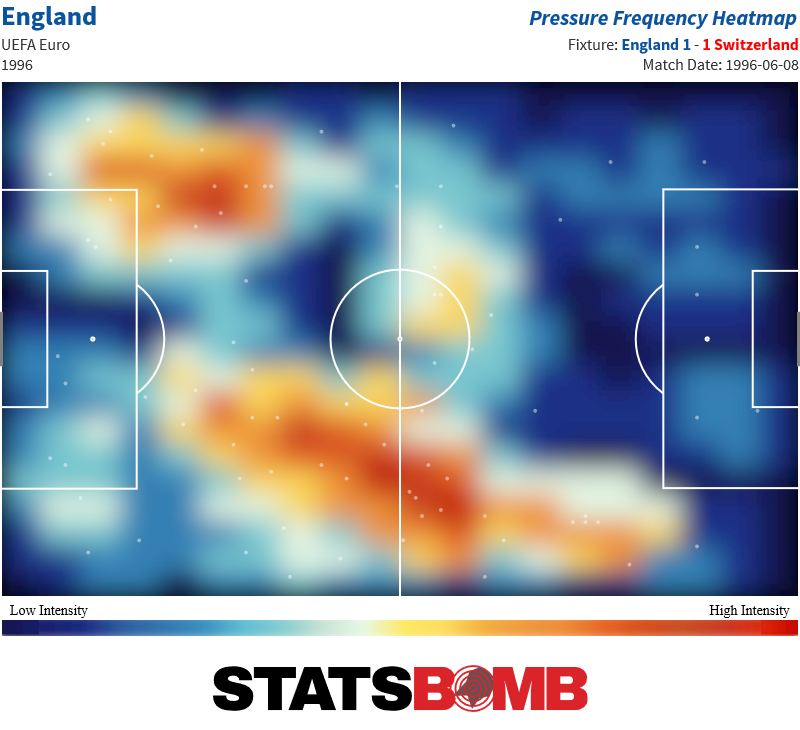

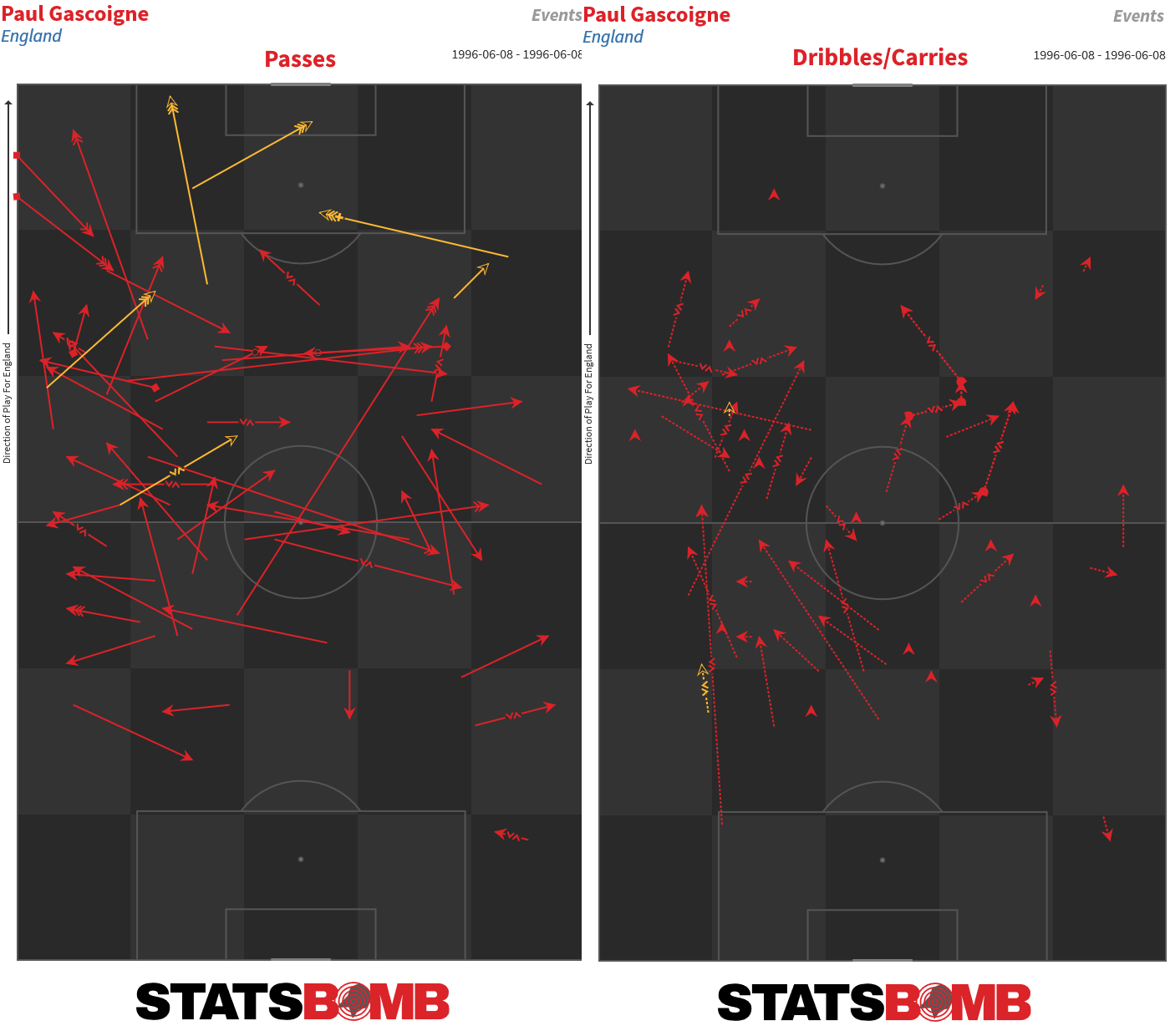

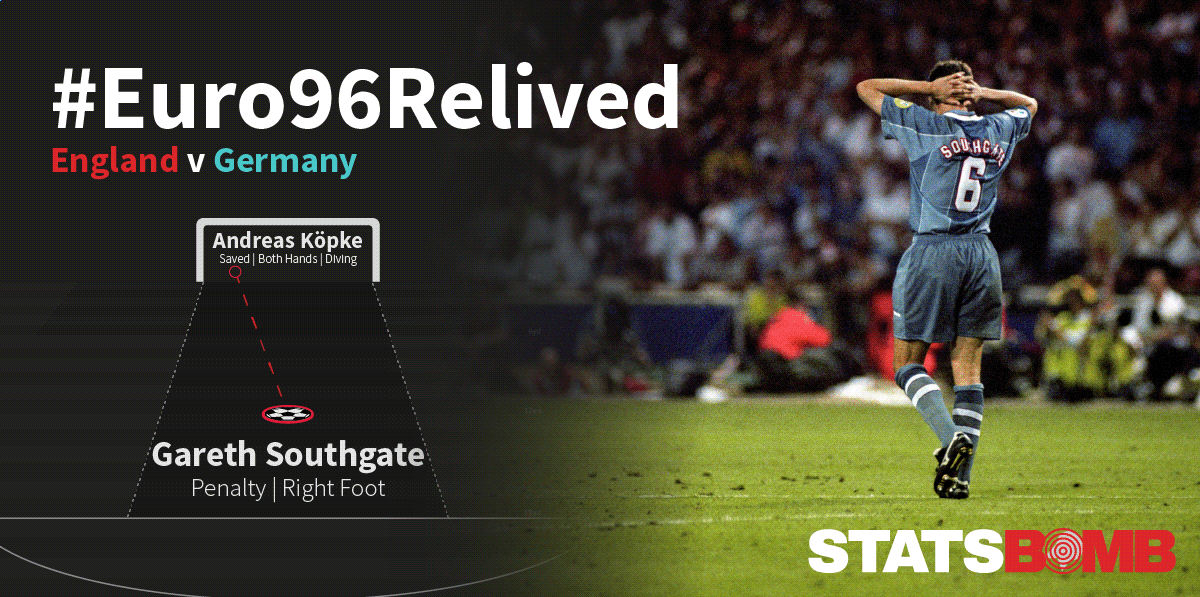

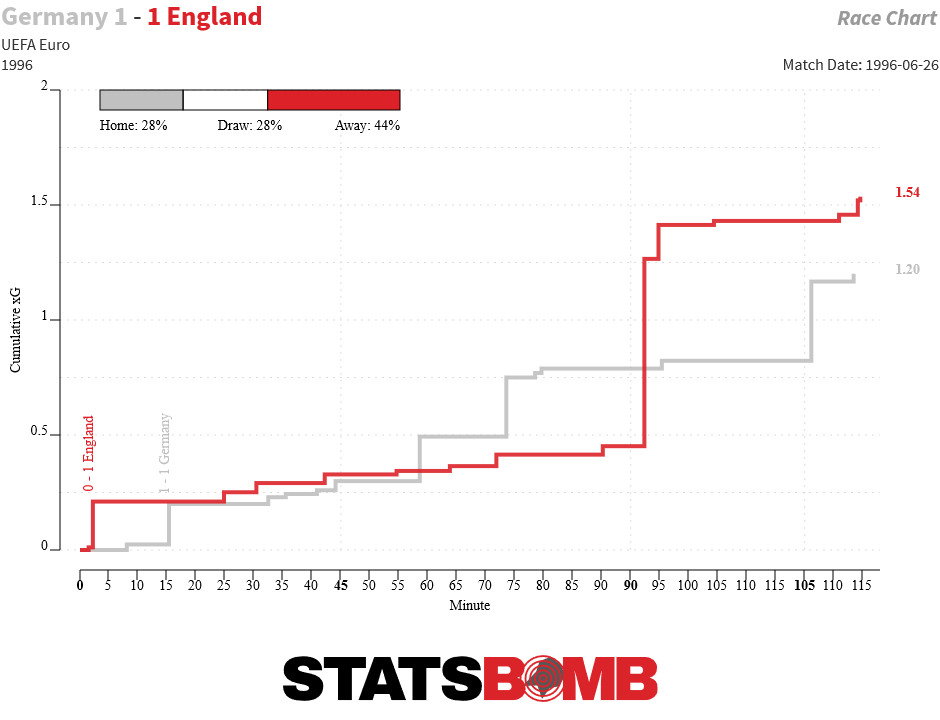

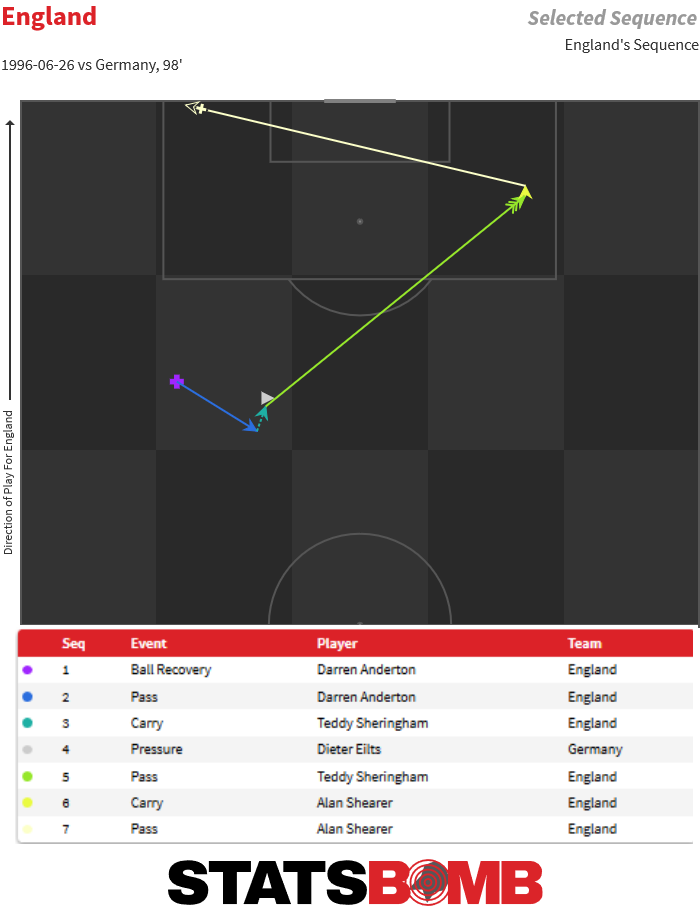

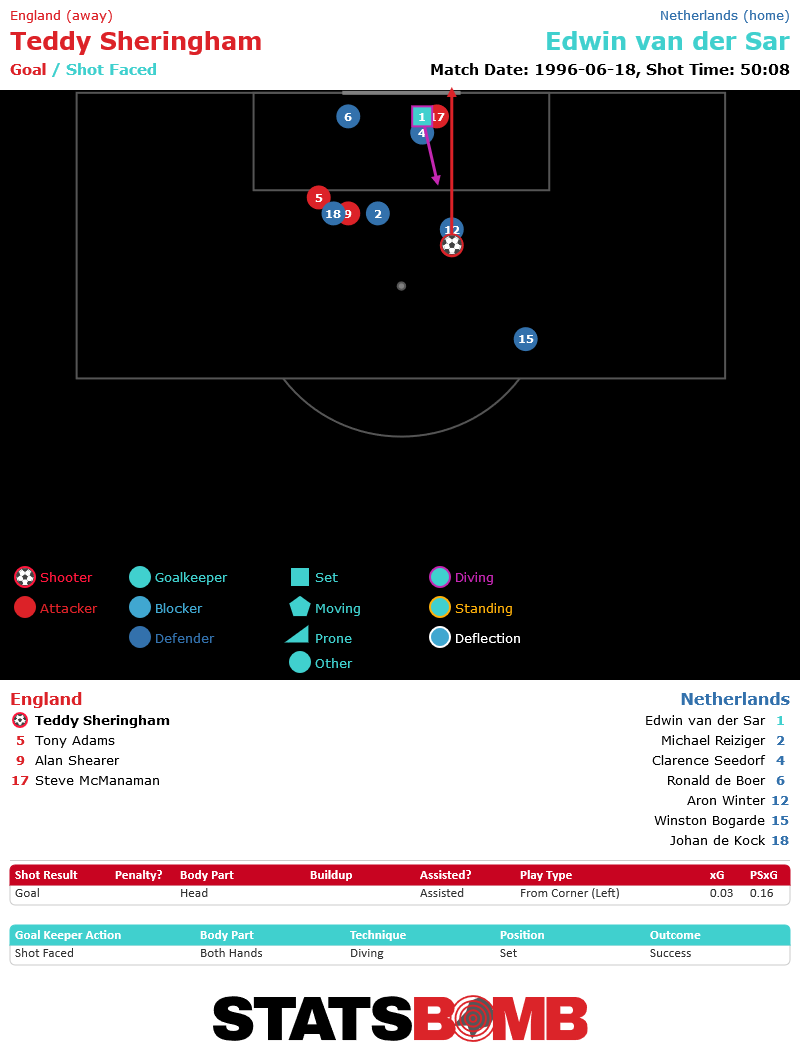

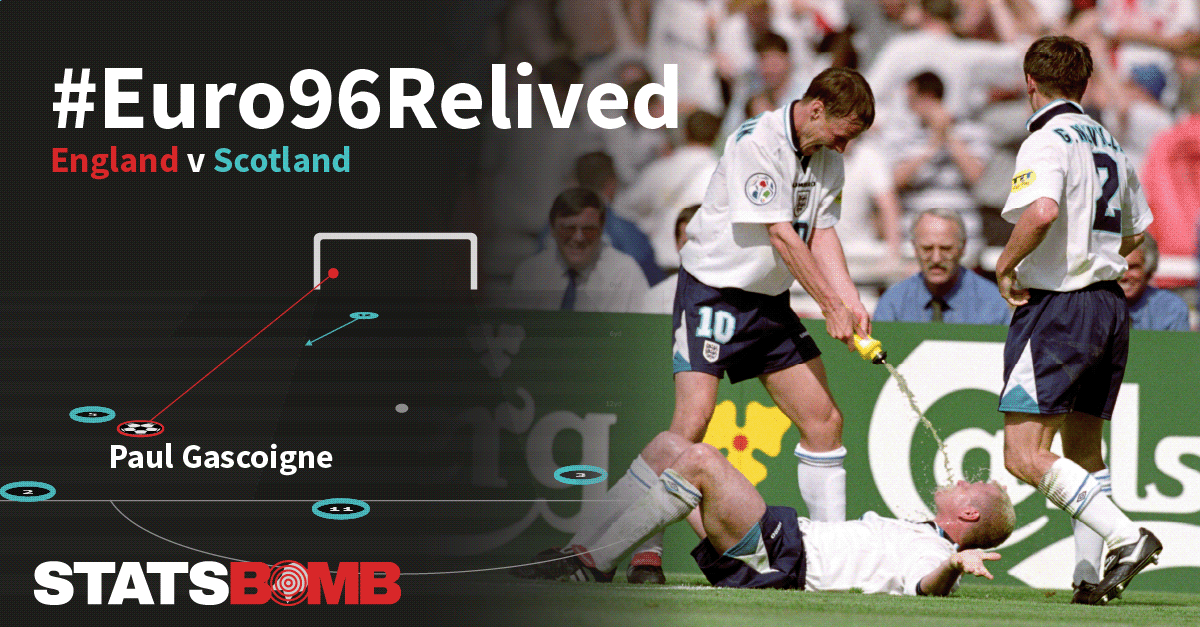

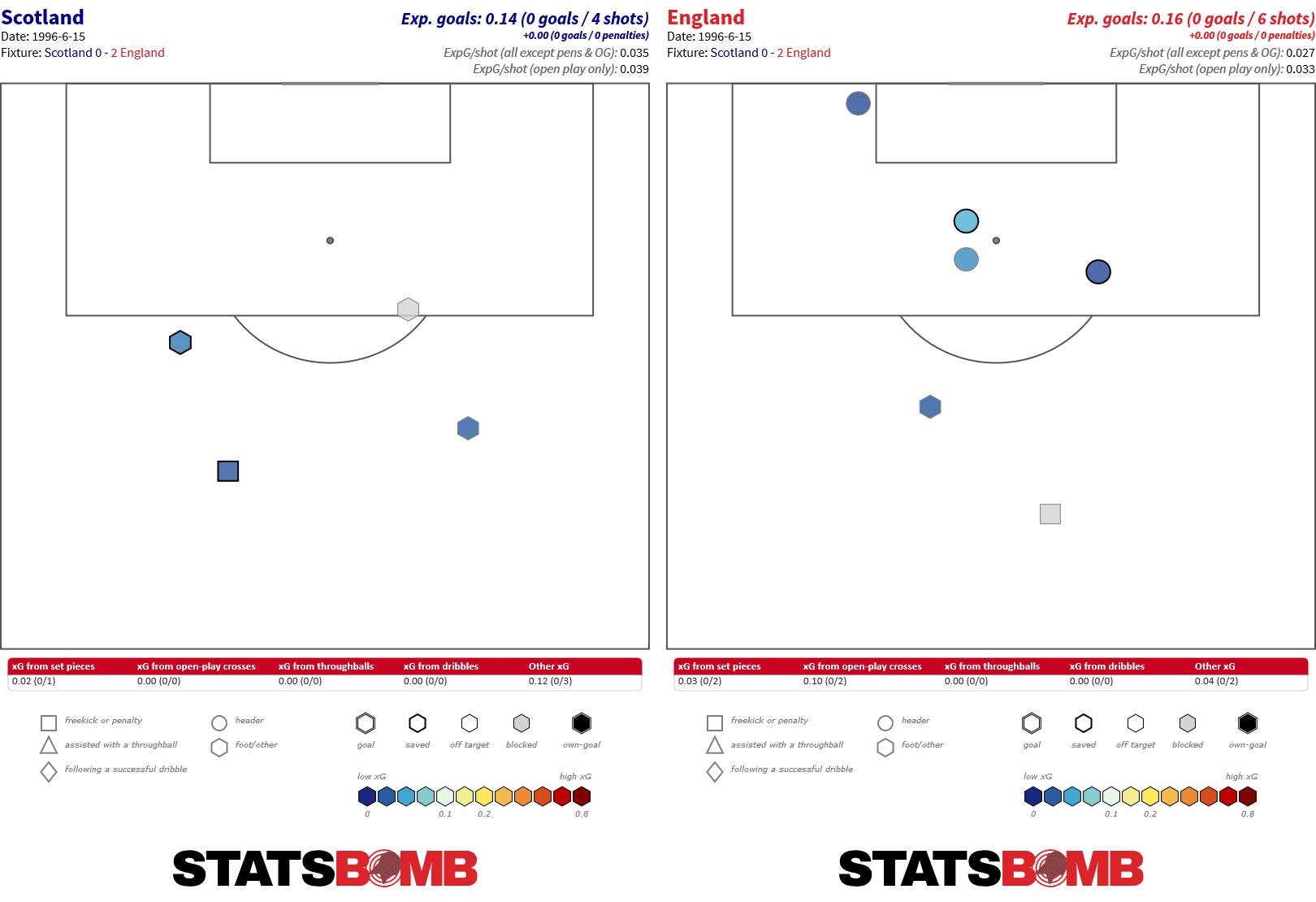

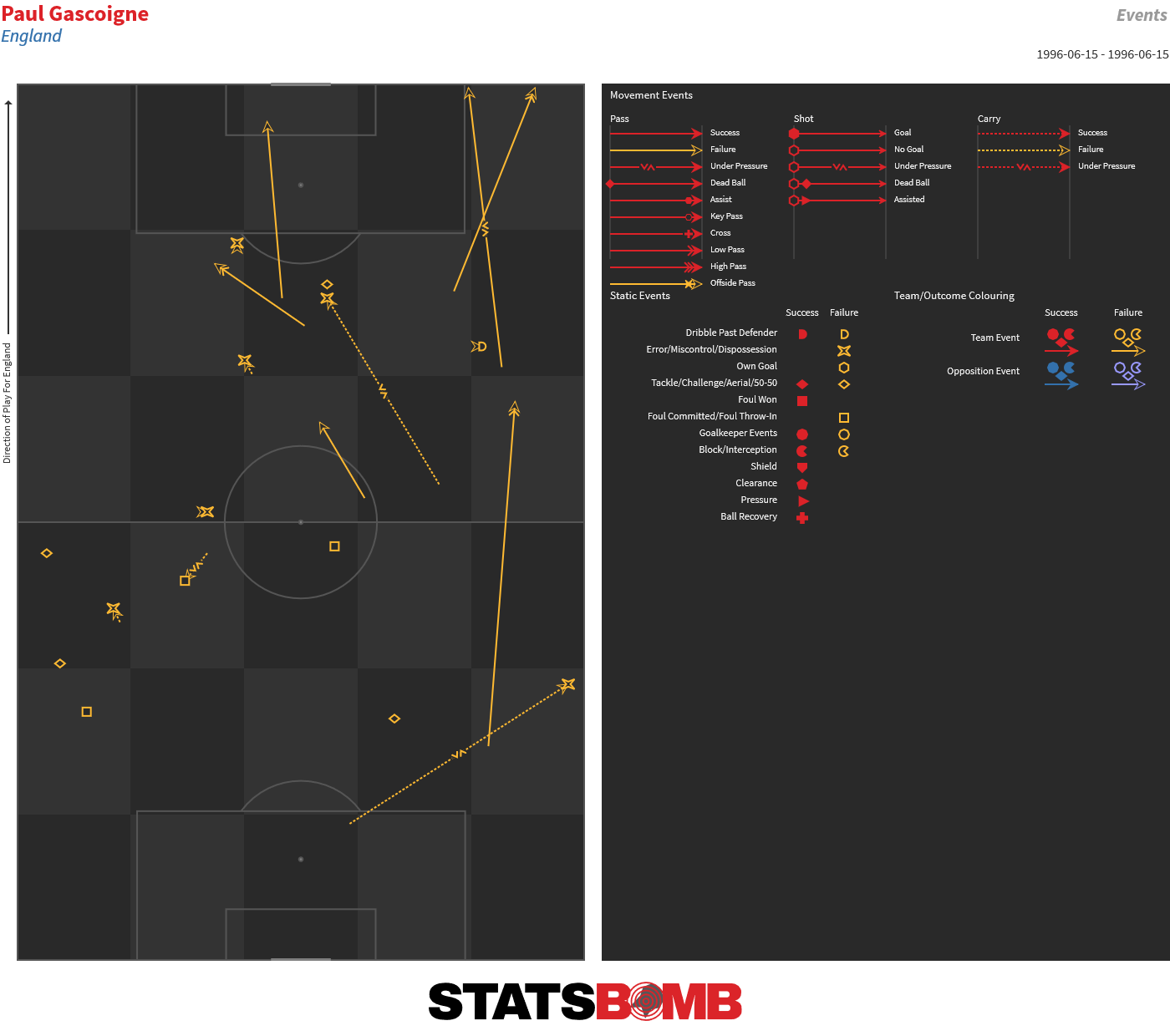

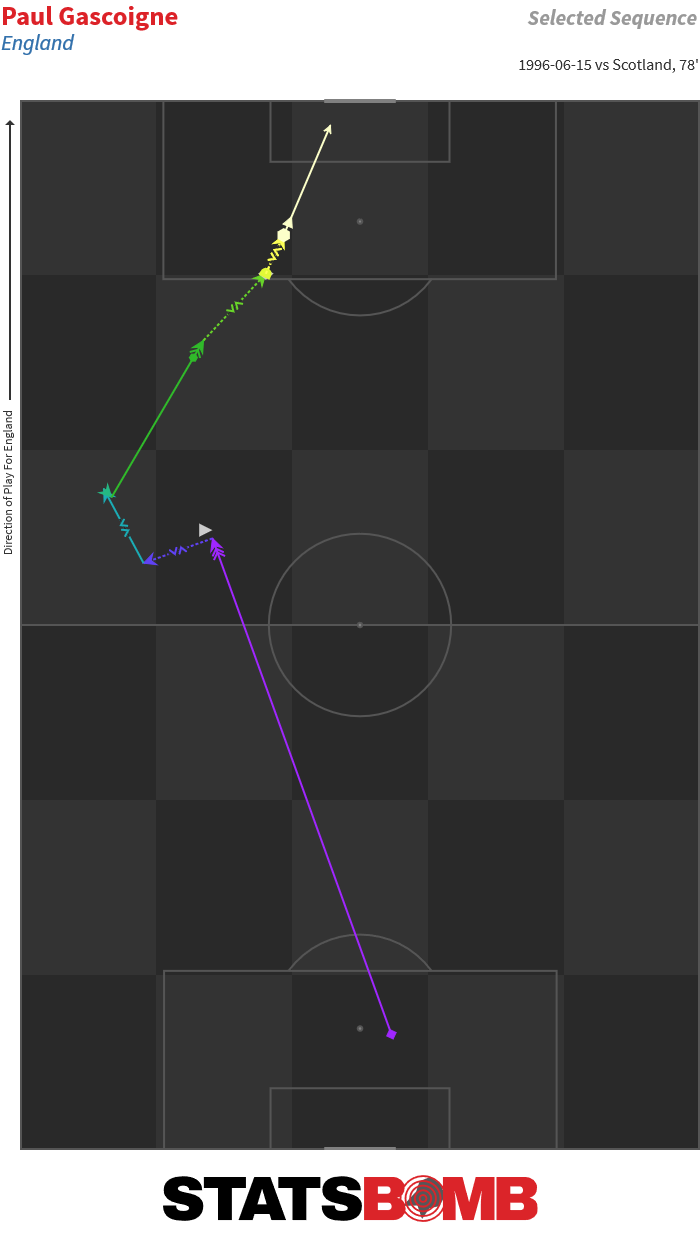

The game was as close as the final score suggested. Two early goals parked the sides at 1-1, a scoreline that persisted to the end of extra time. England had not one but two huge chances to win the game late on. Darren Anderton hit the post with the net gaping, as he tried to turn a ball that had trickily landed behind him, then famously Paul Gascoigne failed to connect with a cross that seemed easier to finish than not. No touch, no shot and therefore no mention in the sequence:

The game was as close as the final score suggested. Two early goals parked the sides at 1-1, a scoreline that persisted to the end of extra time. England had not one but two huge chances to win the game late on. Darren Anderton hit the post with the net gaping, as he tried to turn a ball that had trickily landed behind him, then famously Paul Gascoigne failed to connect with a cross that seemed easier to finish than not. No touch, no shot and therefore no mention in the sequence:

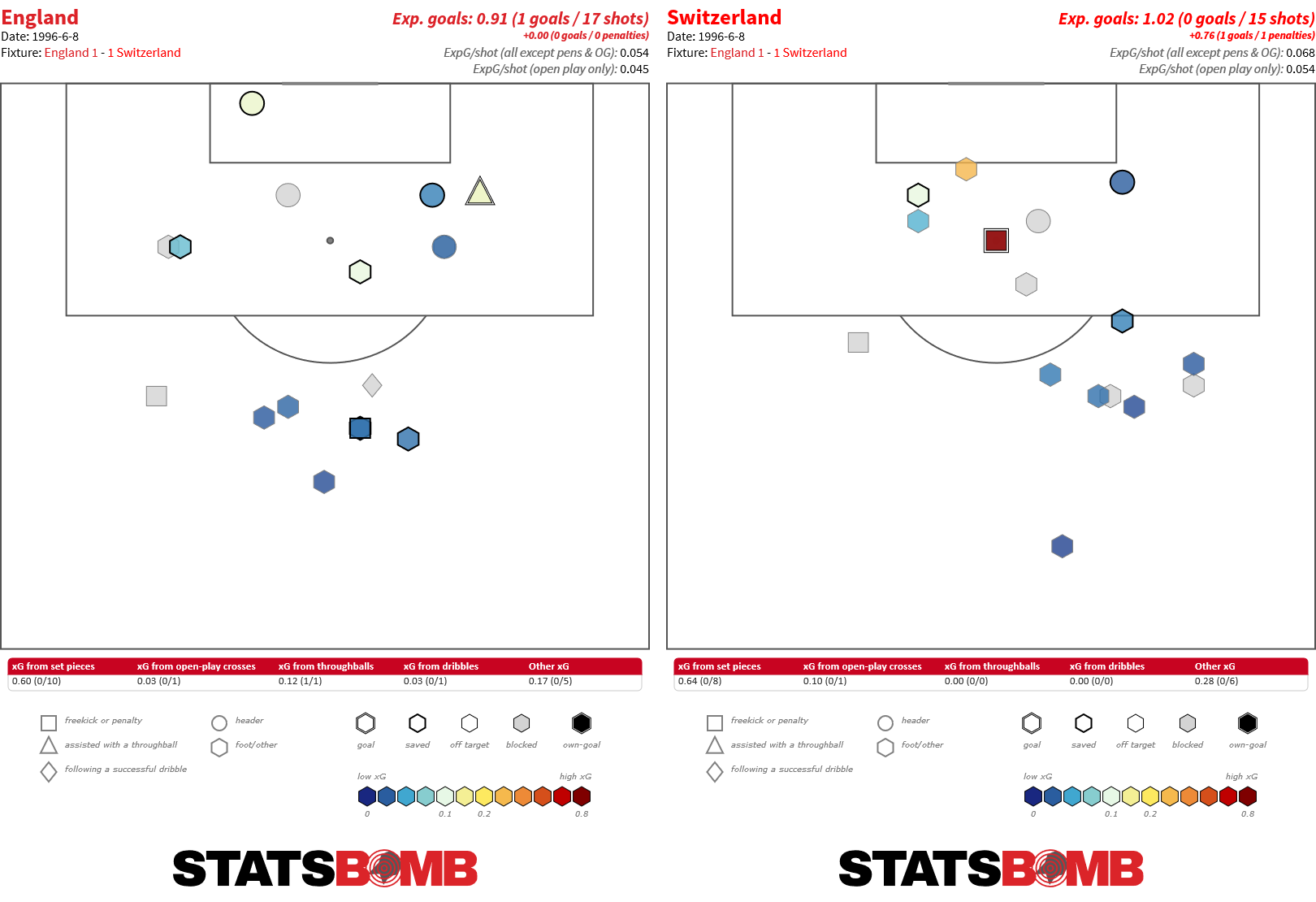

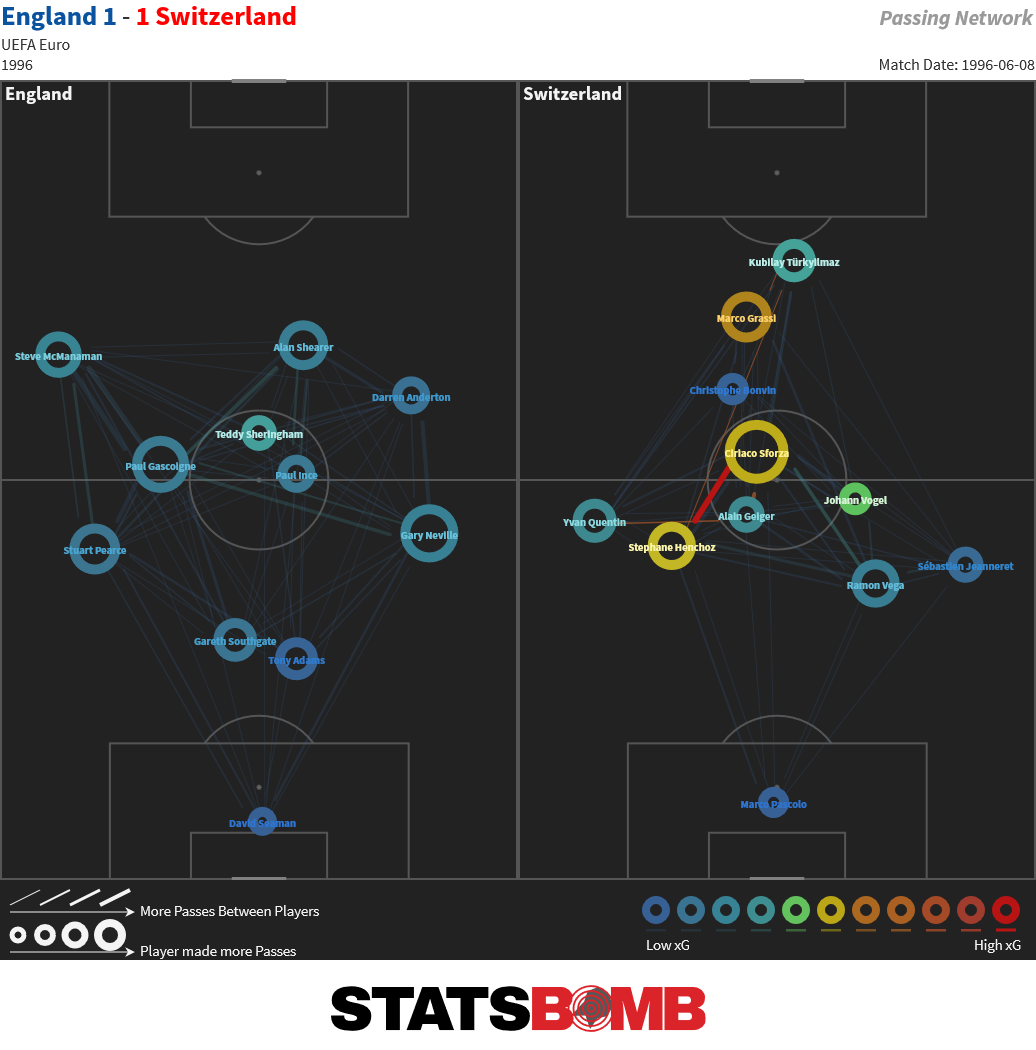

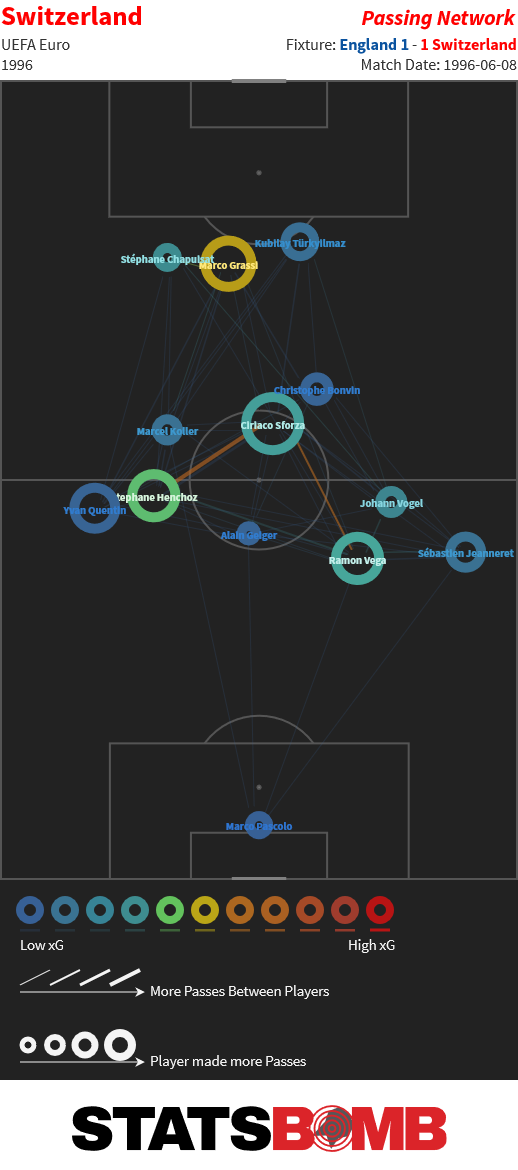

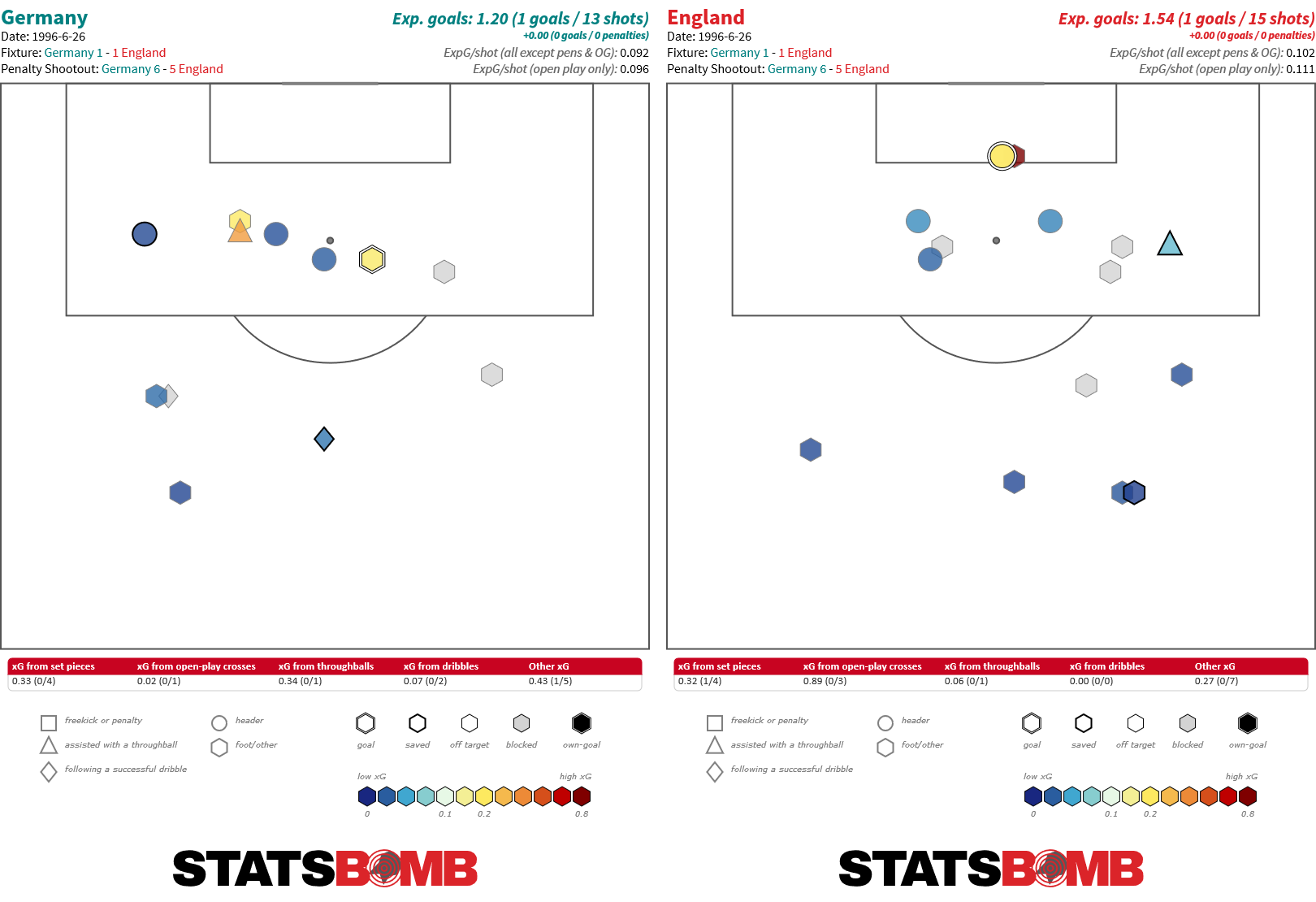

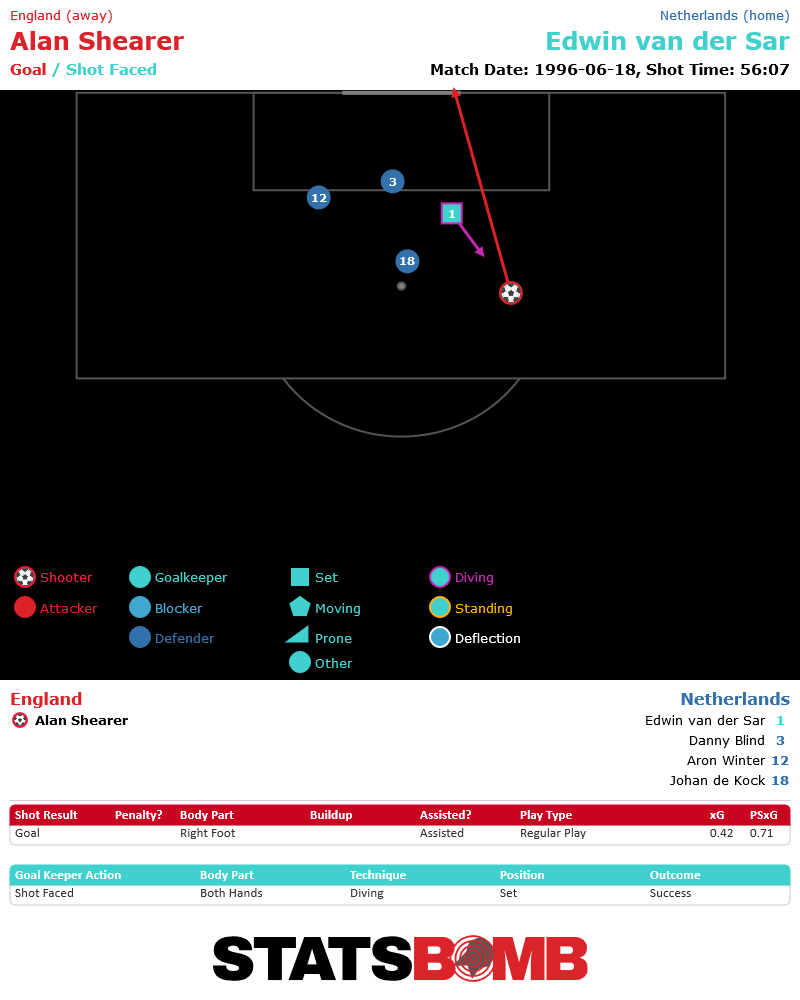

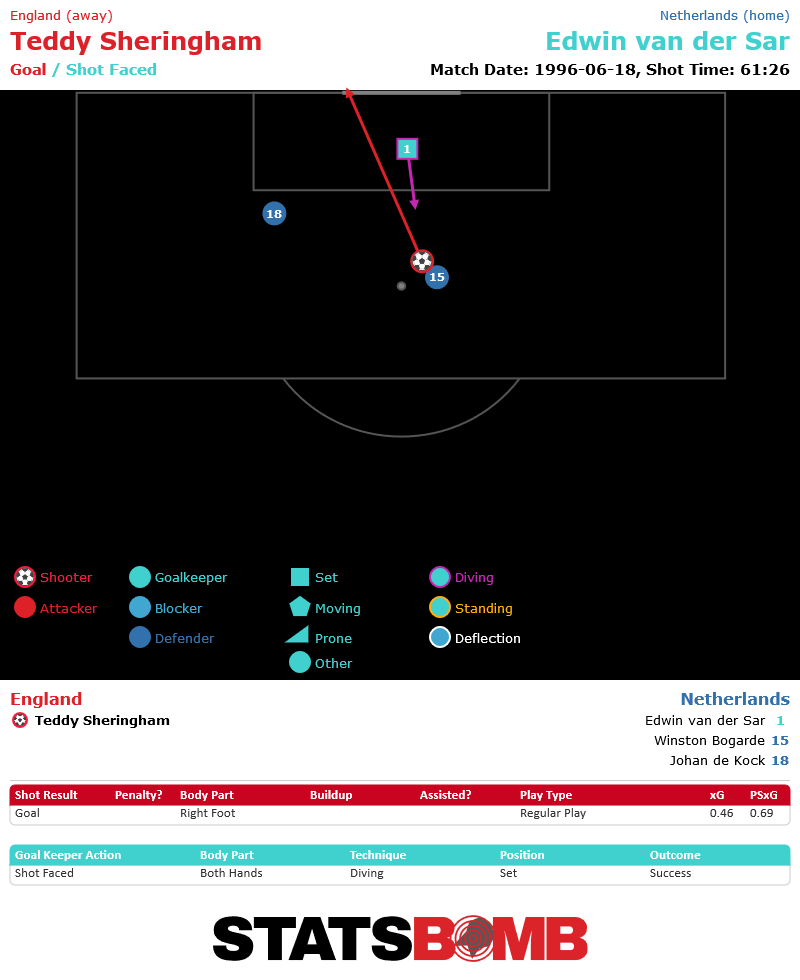

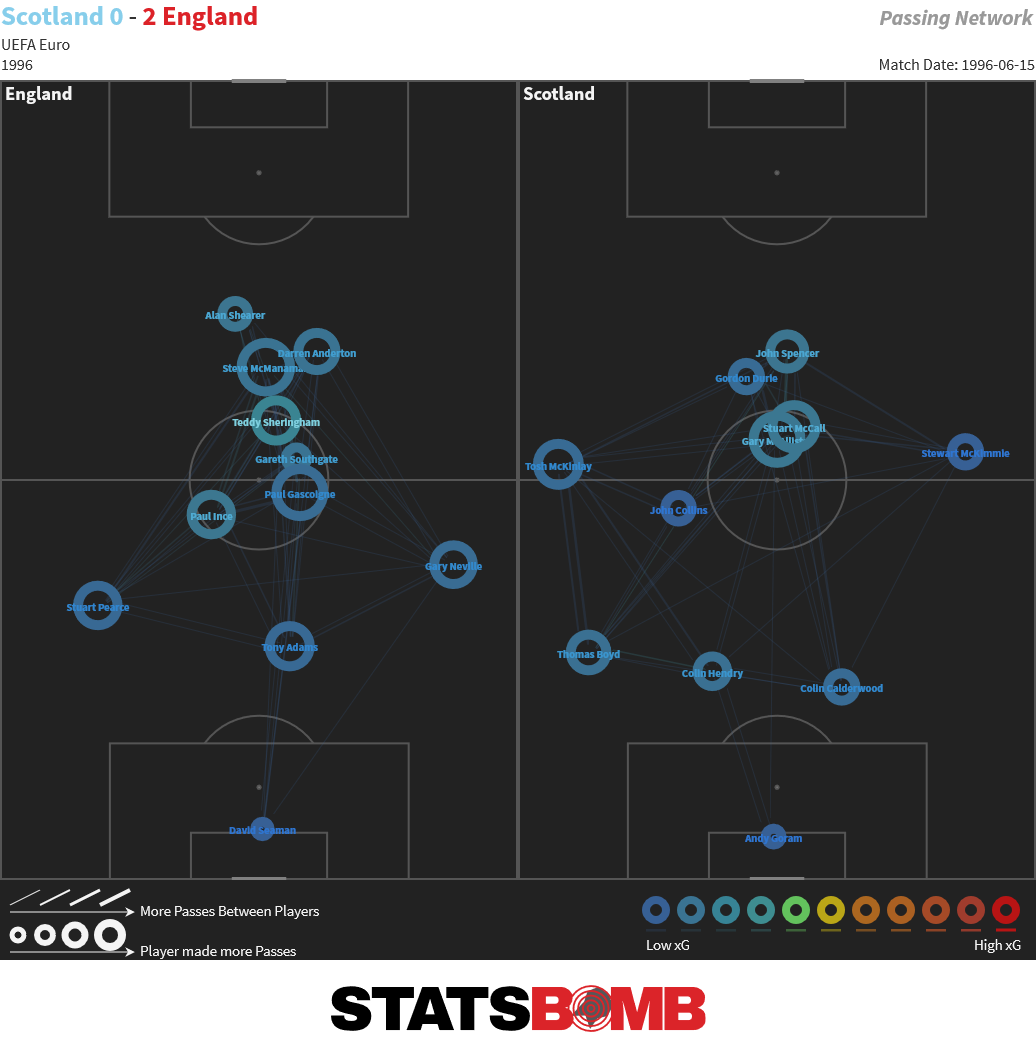

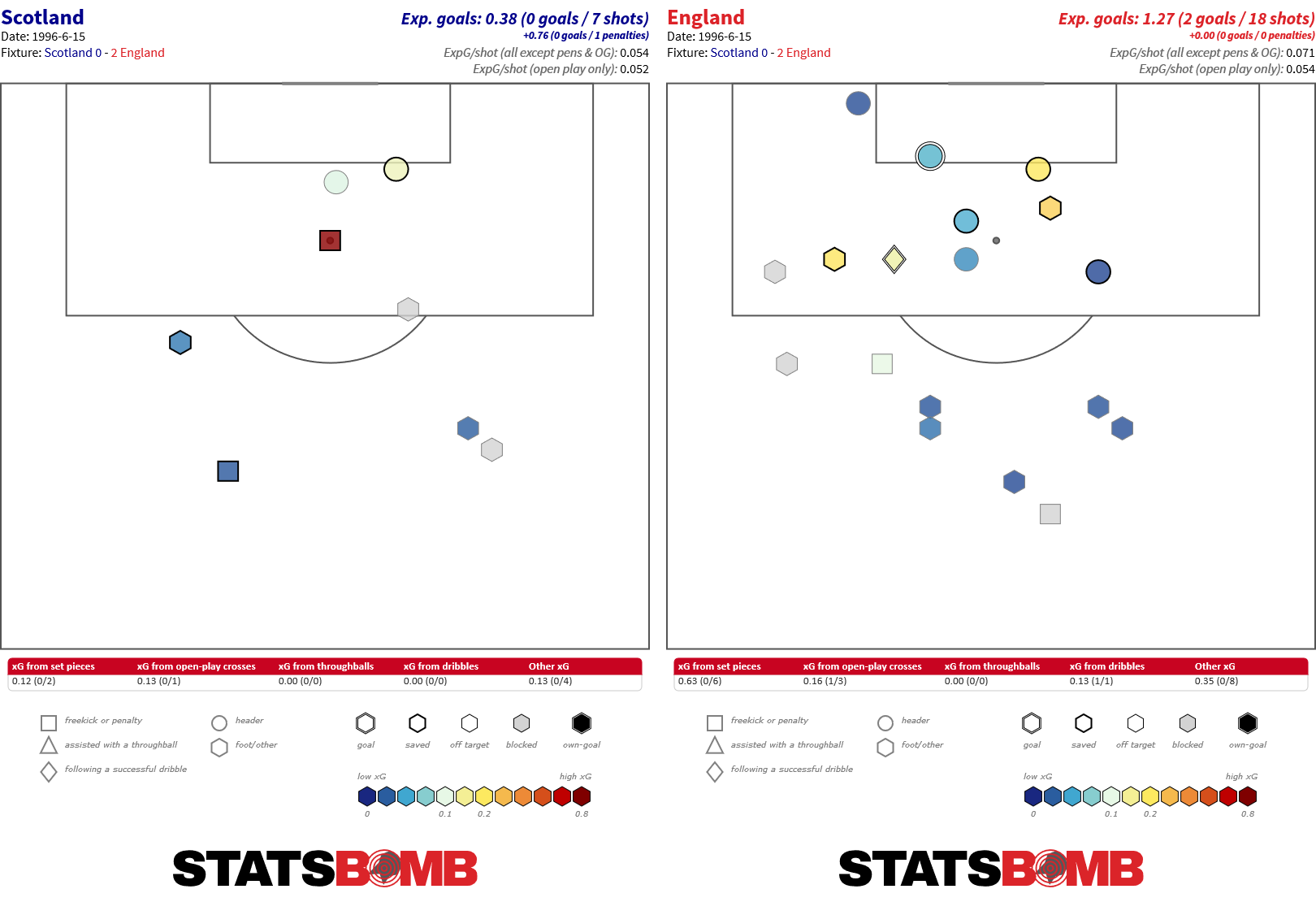

As we can see this was not a game of high quality chances. Apart from Anderton's miss, Alan Shearer's 3rd minute opener was the only shot significantly in advance of the penalty sport for either side. England once again tweaked their formation in this game, with three centre backs in a nominal 3-5-2 system, with wingers rather than traditional full backs placed in the wide slots:

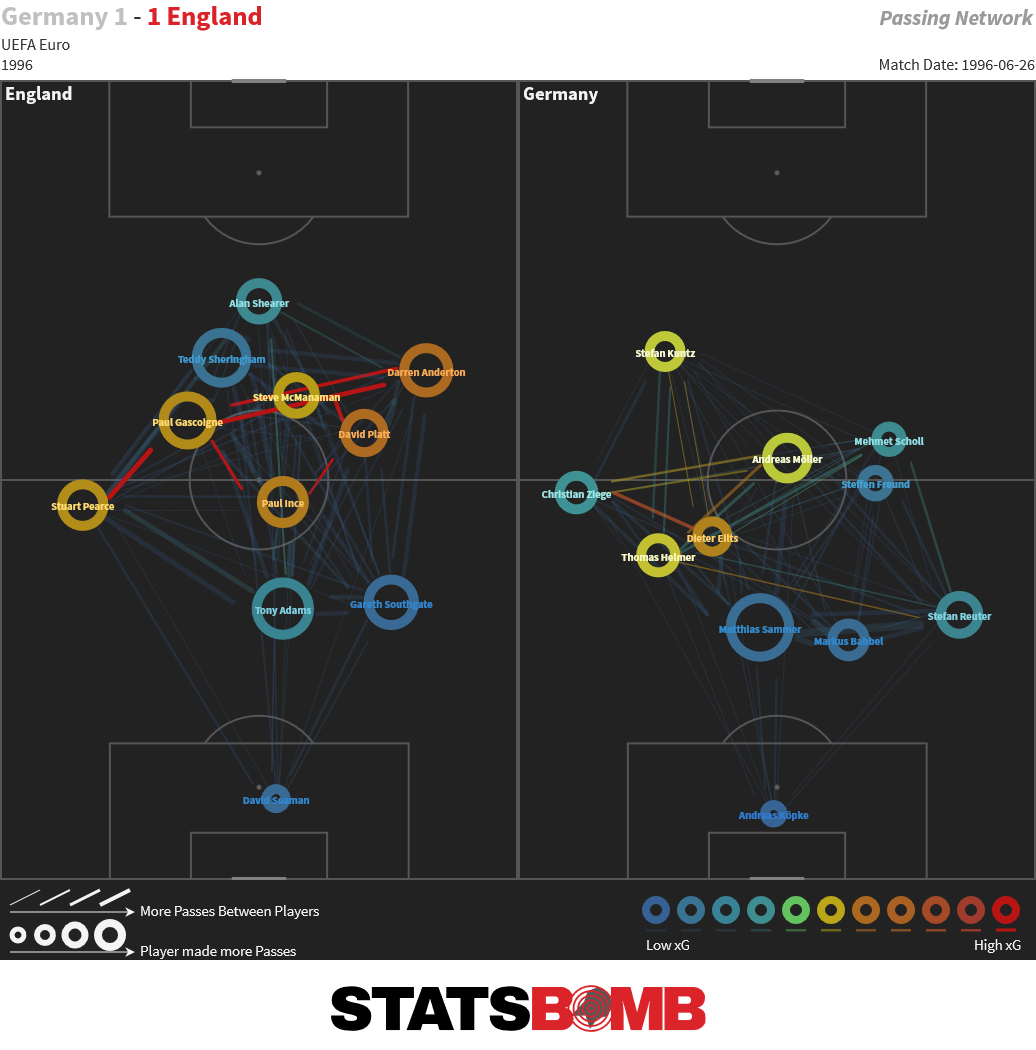

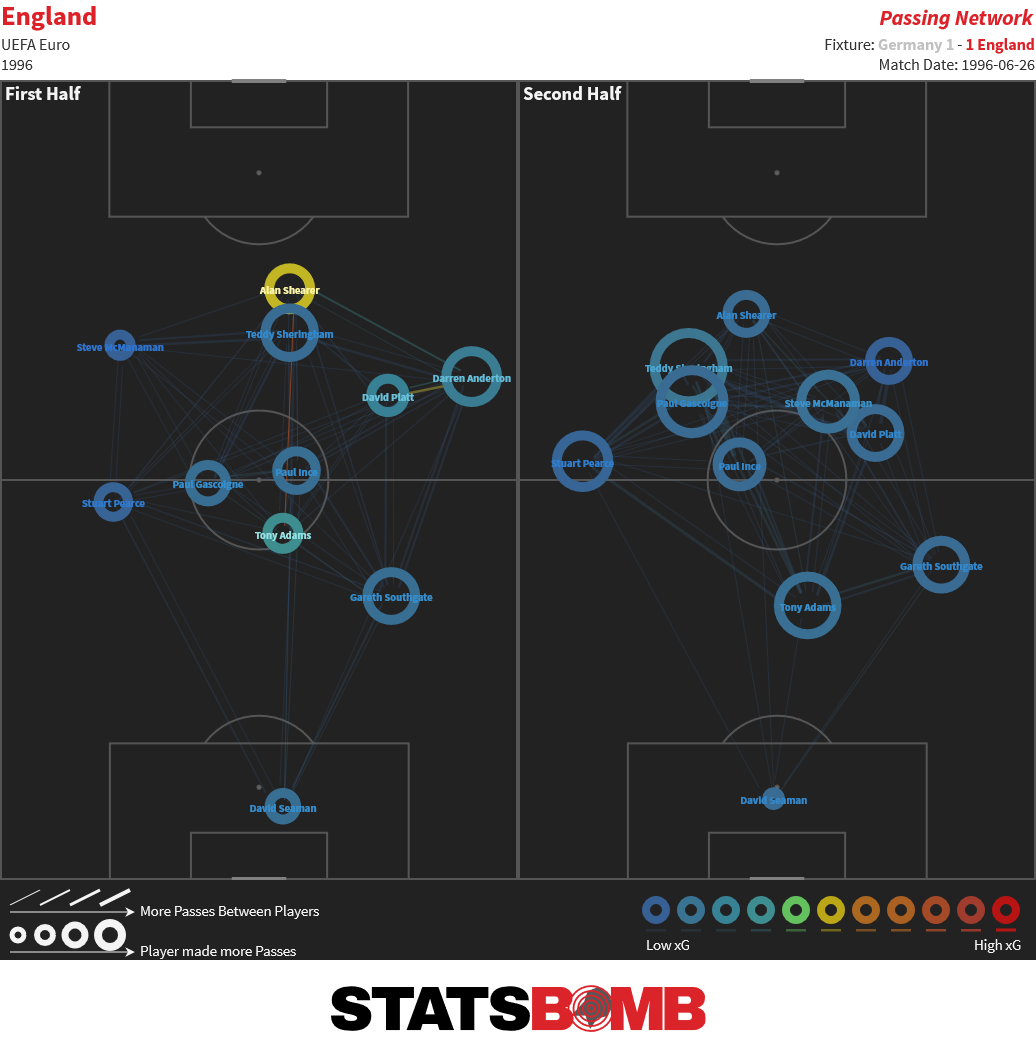

As we can see this was not a game of high quality chances. Apart from Anderton's miss, Alan Shearer's 3rd minute opener was the only shot significantly in advance of the penalty sport for either side. England once again tweaked their formation in this game, with three centre backs in a nominal 3-5-2 system, with wingers rather than traditional full backs placed in the wide slots:  Unusually England did not make a substitution during the whole game, which gives us a unique opportunity to compare the first and second half pass positions without the interruption of replacements:

Unusually England did not make a substitution during the whole game, which gives us a unique opportunity to compare the first and second half pass positions without the interruption of replacements:  Steve McManaman and Darren Anderton kept to their wings in the first half, but were far more flexible in the second half. Gascoigne too saw a change in role from half to half, as he moved forwards as the game went on. Territory wise, England had far the better of it. Six players attempted over twenty passes in Germany's final third, while no German player attempted more than fifteen at the opposite end. David Platt in particular was neat and tidy with 94% passing, while unusually for a forward, Teddy Sheringham got through the most volume; 75 passes in total. In the end though, they couldn't make it pay and the game went to penalties.

Steve McManaman and Darren Anderton kept to their wings in the first half, but were far more flexible in the second half. Gascoigne too saw a change in role from half to half, as he moved forwards as the game went on. Territory wise, England had far the better of it. Six players attempted over twenty passes in Germany's final third, while no German player attempted more than fifteen at the opposite end. David Platt in particular was neat and tidy with 94% passing, while unusually for a forward, Teddy Sheringham got through the most volume; 75 passes in total. In the end though, they couldn't make it pay and the game went to penalties.

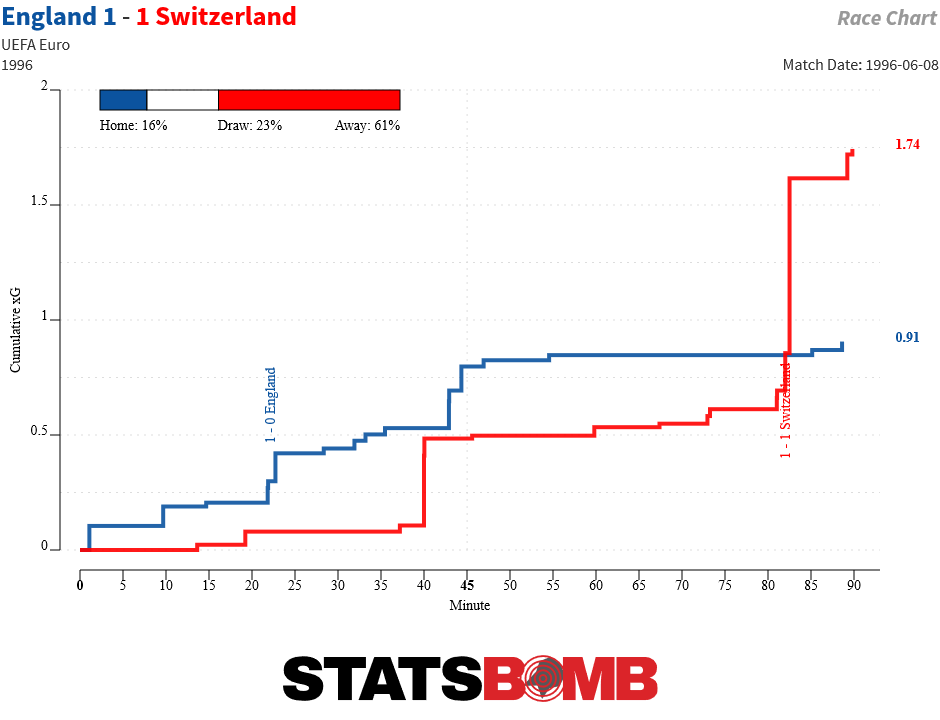

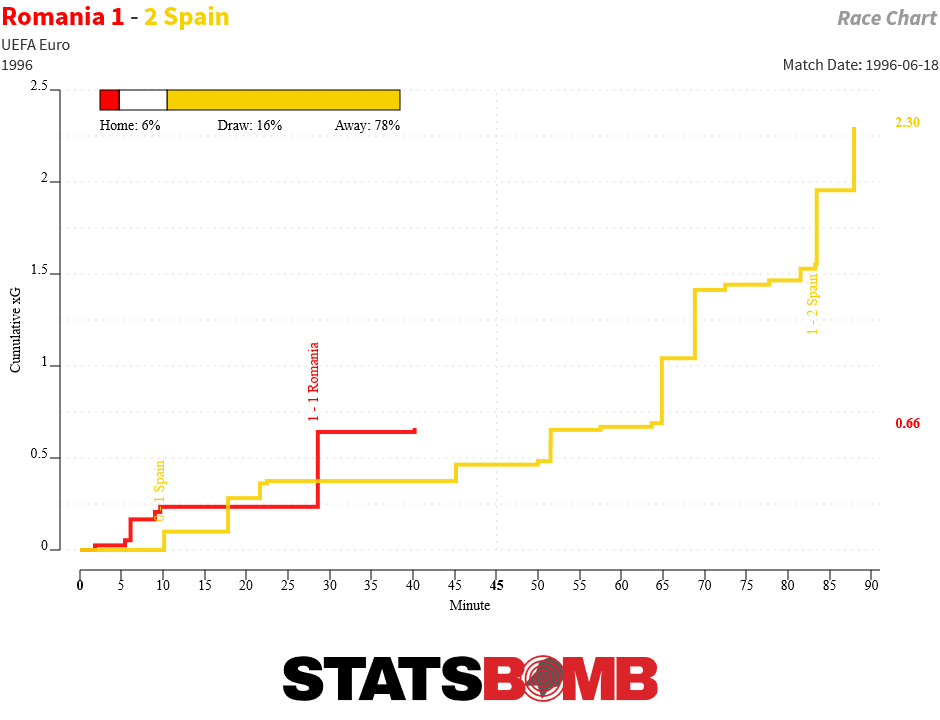

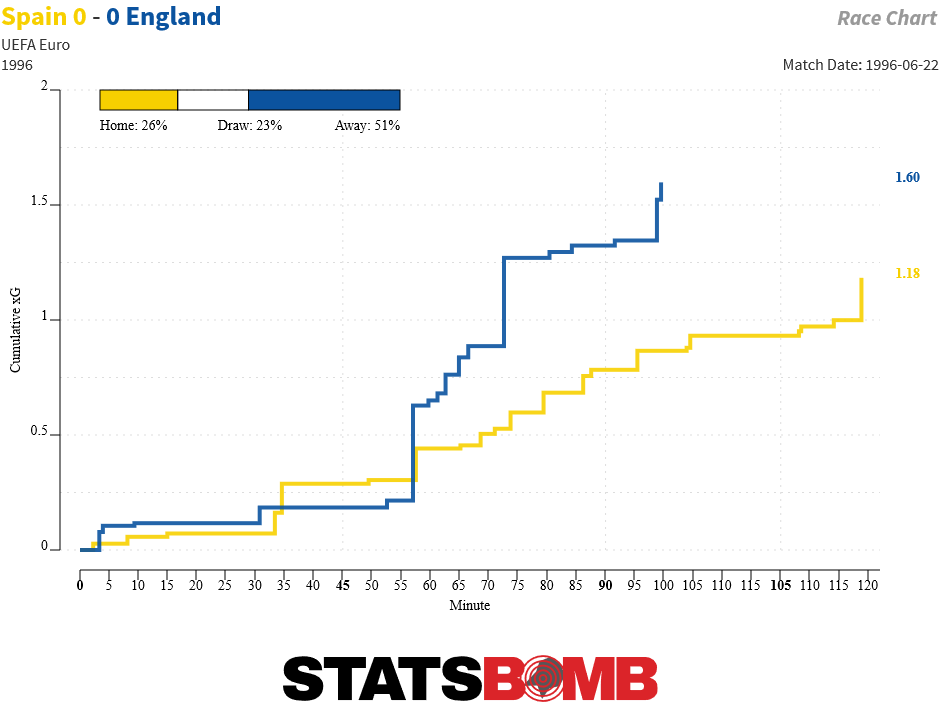

This game would be different though, up against an English team who top scored in the group stages. In the event the game was fairly cagey and even. Both team attempted around 600 passes and completed them at a percentage in the low 70s and while the shots were frequent, good chances were few:

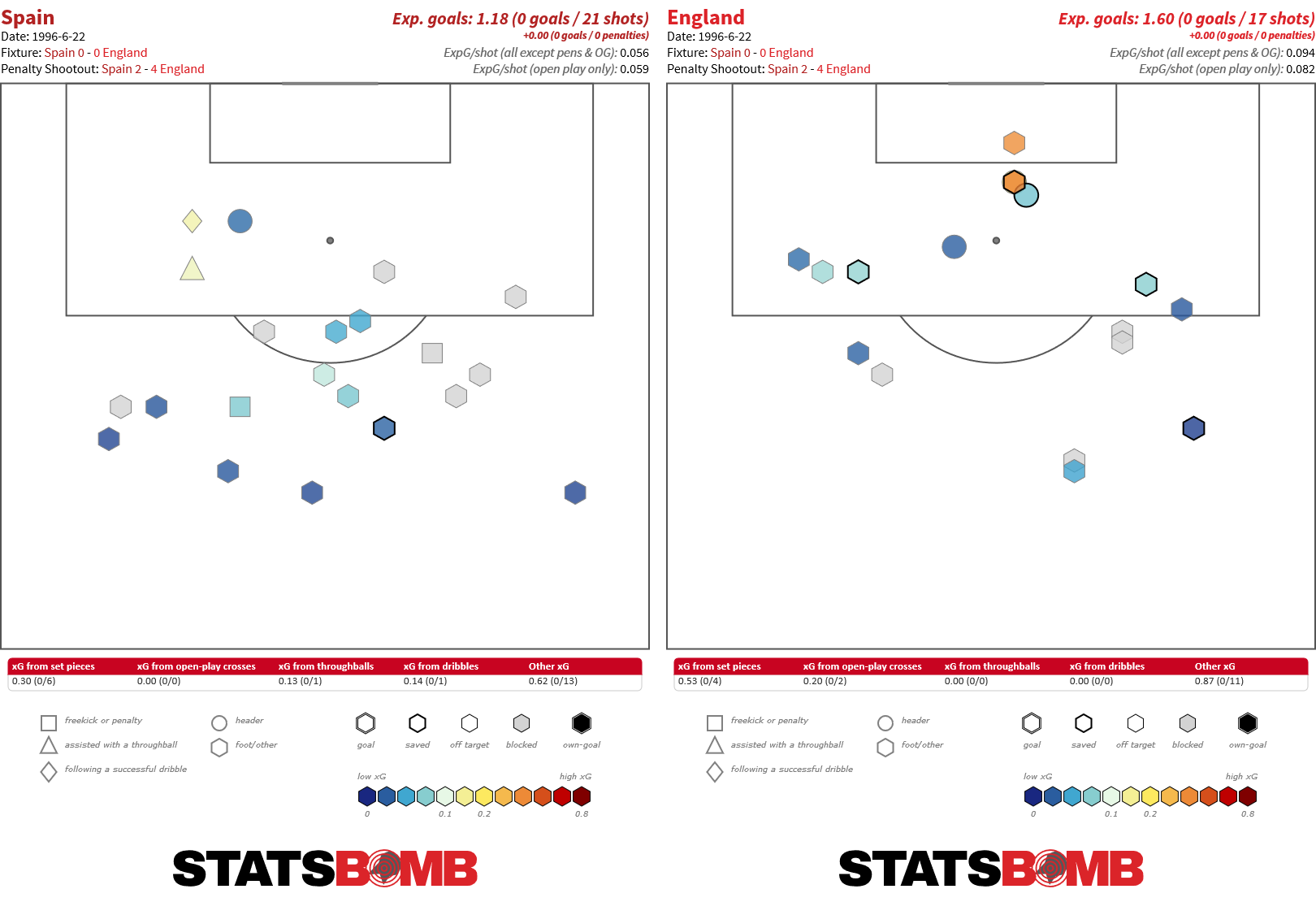

This game would be different though, up against an English team who top scored in the group stages. In the event the game was fairly cagey and even. Both team attempted around 600 passes and completed them at a percentage in the low 70s and while the shots were frequent, good chances were few:  Did England tire? Surely they didn't try and hold for penalties? Regardless they had no shots in the second half of extra time. Overall, Spain outshot England 21 to 17 but their shot quality and accuracy was poor; just one shot on target and a lot of efforts from long range:

Did England tire? Surely they didn't try and hold for penalties? Regardless they had no shots in the second half of extra time. Overall, Spain outshot England 21 to 17 but their shot quality and accuracy was poor; just one shot on target and a lot of efforts from long range:  And so penalties took centre stage, with memories of England's 1990 World Cup still fresh.

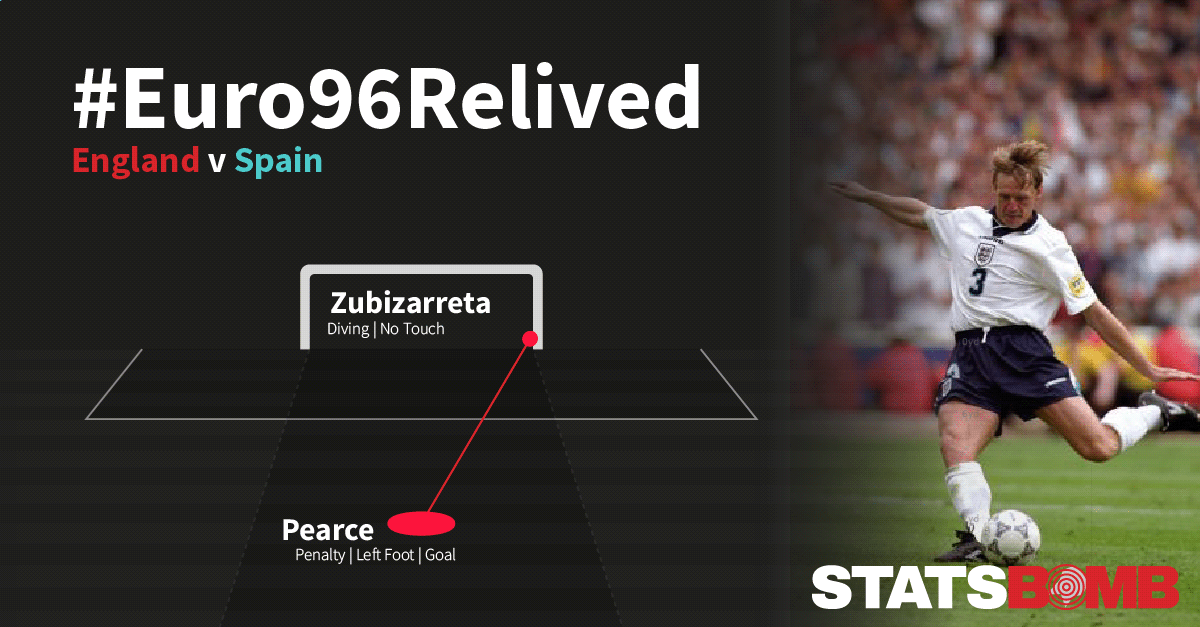

And so penalties took centre stage, with memories of England's 1990 World Cup still fresh.  Shearer scored with aplomb, Fernando Hierro--who had taken the most shots in the game-7-with no success, failed again as he crashed the ball against the bar. David Platt scored, as did Guillermo Amor. Stuart Pearce stepped up next, like Platt he'd taken a penalty against Germany six years before, however unlike Platt he'd missed. Time for redemption? A trademark powerful strike answered that question with a resounding "yes" and the Wembley crowd responded wildly. Alberto Belsué scored to temporarily quieten them, Paul Gascoigne scored to raise the noise levels once more. Lastly Miguel Ángel Nadal stepped up, put the ball to David Seaman's left and the keeper guessed correctly. The semi-finals and Germany beckoned for England.

Shearer scored with aplomb, Fernando Hierro--who had taken the most shots in the game-7-with no success, failed again as he crashed the ball against the bar. David Platt scored, as did Guillermo Amor. Stuart Pearce stepped up next, like Platt he'd taken a penalty against Germany six years before, however unlike Platt he'd missed. Time for redemption? A trademark powerful strike answered that question with a resounding "yes" and the Wembley crowd responded wildly. Alberto Belsué scored to temporarily quieten them, Paul Gascoigne scored to raise the noise levels once more. Lastly Miguel Ángel Nadal stepped up, put the ball to David Seaman's left and the keeper guessed correctly. The semi-finals and Germany beckoned for England.

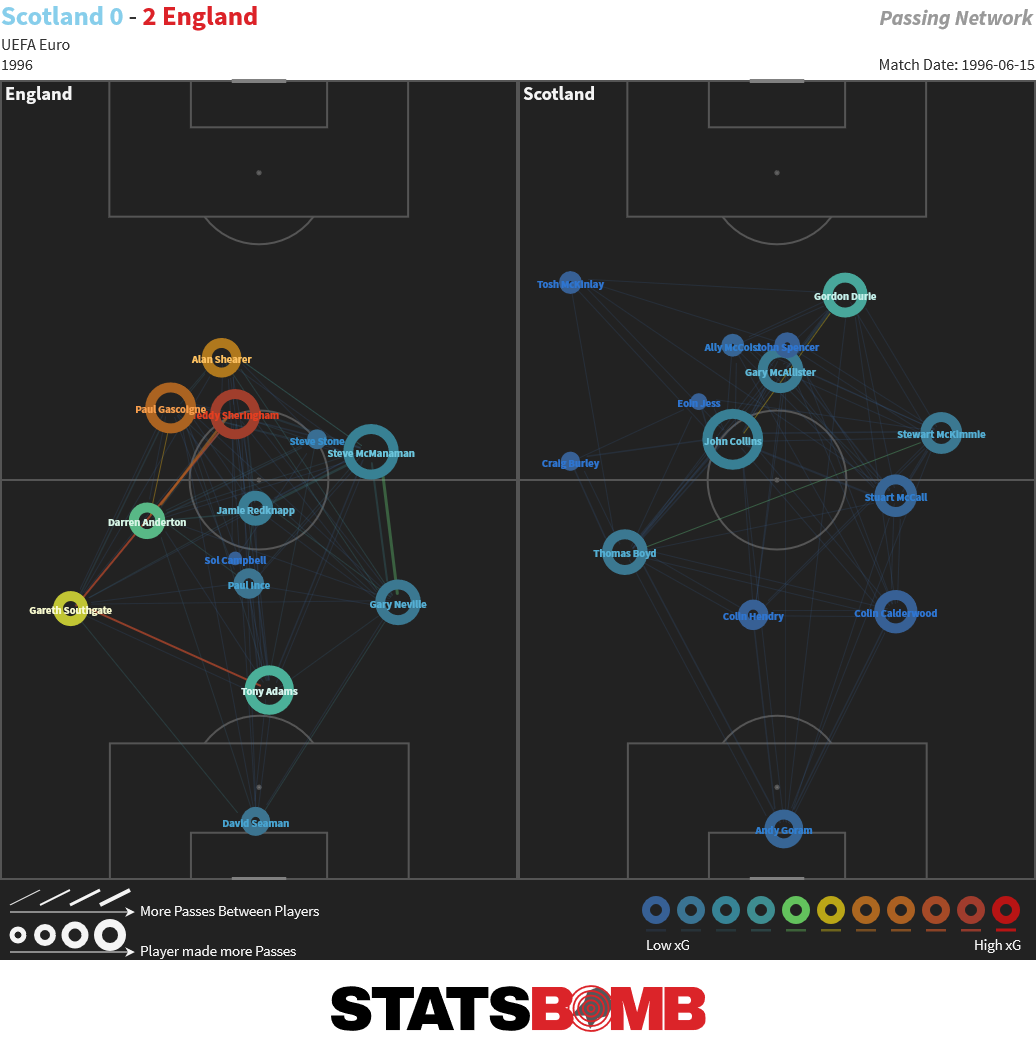

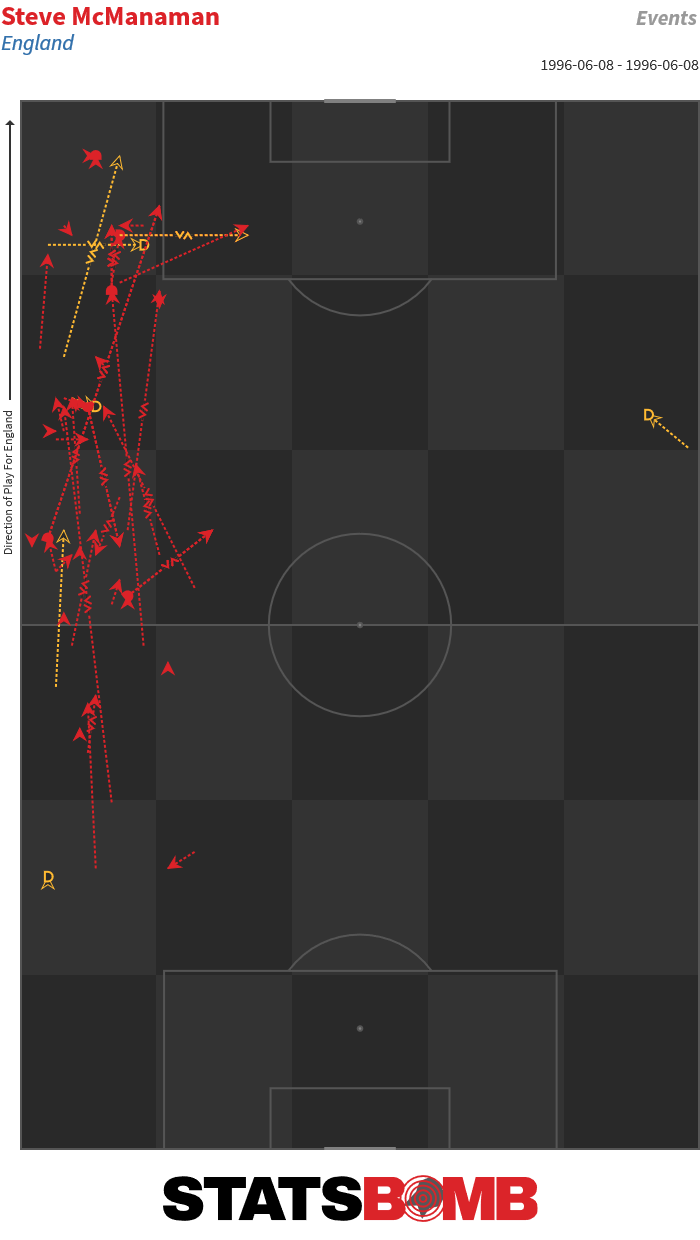

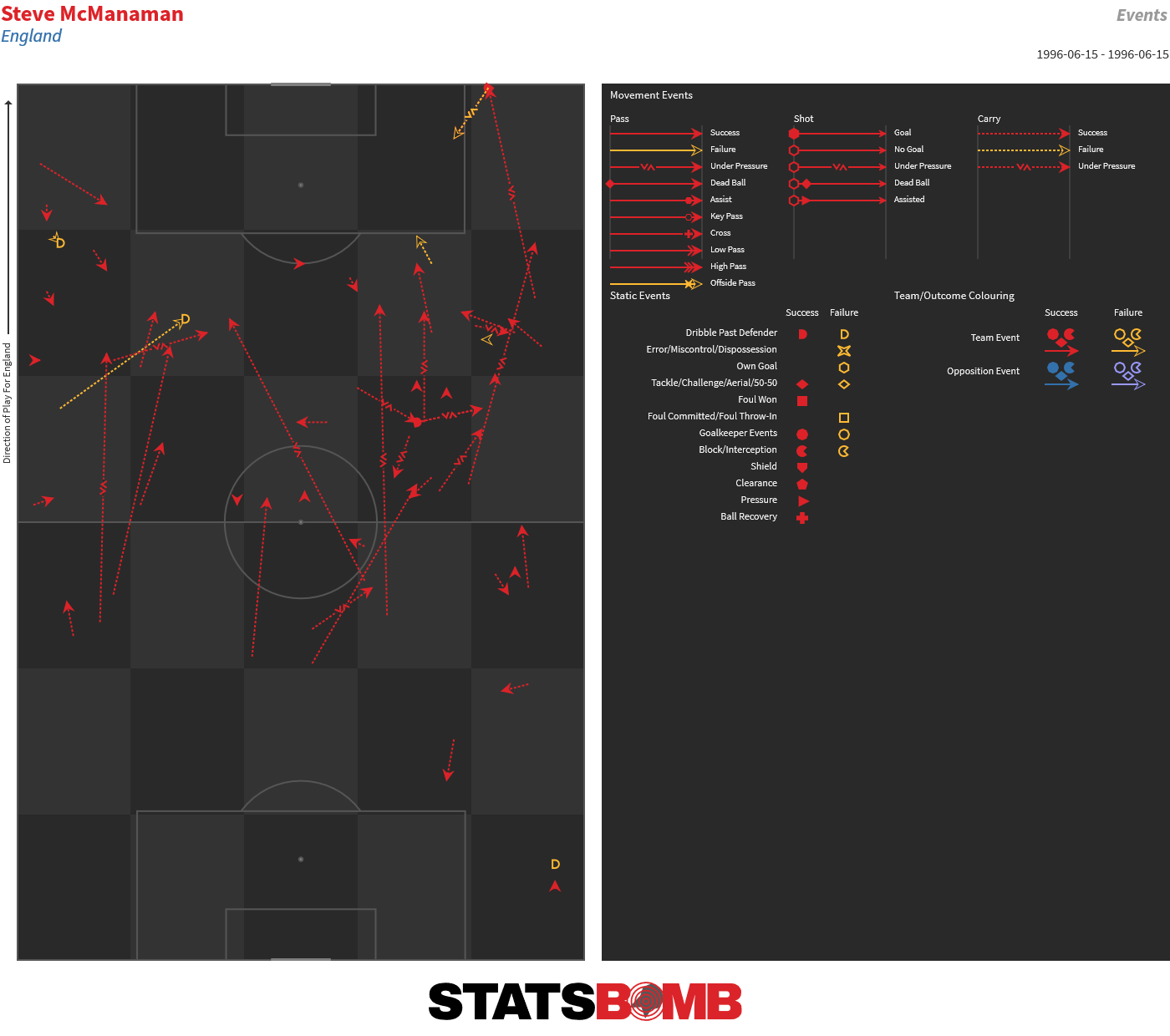

England made a key change at half-time, Jamie Redknapp came on for Stuart Pearce. This meant Southgate could move back to his more usual position in the back line, and Redknapp's passing range could allow England a little more control in the middle of the park. The opening minutes of the second half saw England come to the fore, Sheringham missed an open header deep inside the box and 2 minutes later they were rewarded when Shearer opened the scoring with a far post header from Neville's cross. However, it was Steve McManaman who set the tempo here, moments before freeing Neville to make that cross he'd advanced from halfway before whistling a left foot shot past the post. Indeed, McManaman's ball carrying was a notable plus again in this game, and he saw more of the ball (48 passes, 22 in the final third) than anyone else on the pitch with good retention (86% completion) for a wide player. Here we see how he carried the ball effectively, a series of long runs deep into Scotland's half.

England made a key change at half-time, Jamie Redknapp came on for Stuart Pearce. This meant Southgate could move back to his more usual position in the back line, and Redknapp's passing range could allow England a little more control in the middle of the park. The opening minutes of the second half saw England come to the fore, Sheringham missed an open header deep inside the box and 2 minutes later they were rewarded when Shearer opened the scoring with a far post header from Neville's cross. However, it was Steve McManaman who set the tempo here, moments before freeing Neville to make that cross he'd advanced from halfway before whistling a left foot shot past the post. Indeed, McManaman's ball carrying was a notable plus again in this game, and he saw more of the ball (48 passes, 22 in the final third) than anyone else on the pitch with good retention (86% completion) for a wide player. Here we see how he carried the ball effectively, a series of long runs deep into Scotland's half.

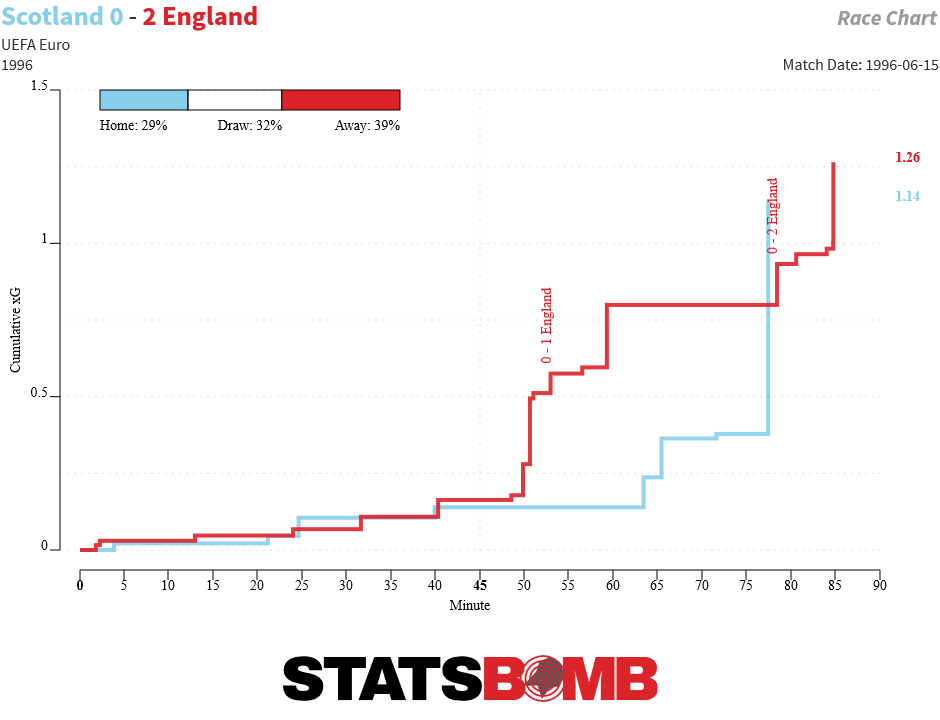

By the end of the game, England were good for their win. The penalty had been Scotland's only good quality chance in the game and England's shot count and expected goals were superior:

By the end of the game, England were good for their win. The penalty had been Scotland's only good quality chance in the game and England's shot count and expected goals were superior:

The change of personnel at half time appeared to be effective and the second half shape of the teams was more forward inclined for England than in the first half, Gascoigne especially found himself higher up the pitch and with Southgate back in the back line, the three central midfielders occupied distinct roles, while the wingers remained in more fixed roles with Anderton left and McManaman right. Scotland struggled to get real width high up the pitch:

The change of personnel at half time appeared to be effective and the second half shape of the teams was more forward inclined for England than in the first half, Gascoigne especially found himself higher up the pitch and with Southgate back in the back line, the three central midfielders occupied distinct roles, while the wingers remained in more fixed roles with Anderton left and McManaman right. Scotland struggled to get real width high up the pitch: