The European season is over. The World Cup is still two weeks away. We have entered the Great Content Gap. But never fear. I shall step in to the breach and fill the yawning hole in your football media consumption diet with my first ever StatsBomb Mailbag. Let’s kick things off with a question from the boss. Where do you want the content side of StatsBomb to be one year from now? --Ted Knutson Because Ted’s the boss his question goes first, but because I run the website I get to refuse to answer his other question about what my most painful moment as an Everton supporter was. What’s interesting about trying to answer this, other than it being essentially an interview question that I’m now answering in public, is that StatsBomb has a lot of freedom in terms of direction. As I’ve written about before, the website exists because the greater StatsBomb data collection and consulting company exists. We are lucky to get to build on the data and not be beholden to selling ads to justify our content. So, if the purpose isn’t to chase clicks (and it isn’t) then how do you measure growth, and channel ambition. Well, one axis is simply the quality of the work. A year from now I want Statsbomb to be a place where readers know they’ll be getting great content, and writers know they have a home for smart ideas. Just because we aren’t selling ads doesn’t mean we’re indifferent to getting eyeballs. We want people to read StatsBomb, it’s just we want them to do it because they believe in our product and our content, not because we have a business model that depends on it. That doesn’t mean that great content can’t also make money. It wouldn’t make sense for StatsBomb to become a subscription site (since the entire point is to be a free place where people can read good work which is supported by the resources that the services StatsBomb actually do sell) but that doesn’t mean there aren’t other ways to grow a business. One particular idea that has always intrigued me is trying to make and sell a Baseball Prospectus style season preview, perhaps with periodic email newsletter updates over the course of the season for those who purchased it. It’s a good engine for developing a discrete marketable content product but also not cannibalizing the free content we’re committed to giving y’all. A year from now I hope that the content on the website continues to grow, evolve and improve (and maybe increases in volume) and that on top of that we are launching different types of content products, some of which are even intended to be profitable. Oh, and I also want a copy editor. https://twitter.com/joe_fishfish/status/1001901722183327744 This was such a good question that Ted decided to answer it on Twitter before I could even write the mailbag. https://twitter.com/mixedknuts/status/1001908098297147392 The question and answer here get at something I think is often misunderstood about analytics and the nerds that do it. Frequently analysts will be skeptical of causal claims surrounding soft factors. Things like confidence, or succumbing to pressure in big moments, or any of the other clichés that swirl around the idea of mentality. But, crucially, that doesn’t mean that they don’t exist. Human beings are human. Sometimes they feel good and sometimes they feel bad. Sometimes they perform well. Sometimes they perform poorly. Sometimes my articles contain lots of typos and sometimes I write clean copy. For data driven people the skepticism isn’t that the underlying thing can't be true, it’s the assumption of causality. Analytics is a field that’s deeply aware of the idea of uncertainty and randomness. It’s not that a player can’t be clutch, it’s that a player who isn’t clutch in a big moment would look more or less the same to an observer as one who had a four-month-old baby that kept him up half the night, or one who was fighting off some bad pad thai or one who just plain old got unlucky. Claiming to know that it was specifically a weak mentality (or whatever you want to call it), as opposed to a weaker claim of simply acknowledging that as one of a number of possibilities is where the difficulties lie. Analysts are rightly quite reticent to make those links strongly given the relatively little data we have. And, quite frankly, historically we aren’t great at correctly predicting who is bad in a big moment and who isn’t. Players choke until they don’t. Arjen Robben was a failure in big moments until he scuffed a shot that found its way into the back of the net in a Champions League final. Then, he isn’t. It’s not that soft factors don’t exist, it’s that all too commonly the things that end up defining a player’s mentality are the things they don’t have control over as opposed to the things they do. It’s an important distinction. It defines how analysts look at a problem. Ted’s response is typical of good work. Be skeptical, but look for data. Try to ground the problem as much as possible. Accept both the reality that humans are humans, and that we are terrible at understanding the transmission mechanism from the human brain to performance on the field. Then, work to bridge that gap. Ok, now it’s time to fill this particular precondition for doing a mailbag. https://twitter.com/Classlicity/status/1001898252084527106 Listen, the obvious answer to this question is Jose Mourinho. The man is a born troll. He’s a master at deploying the same arguments against adversaries that he ridicules as absurd when deployed against him. He says things that are technically correct while being wildly inaccurate if contextualized. He is brilliant at taking any argument and twisting it around until its fought on whatever grounds he wants to fight it on. When he’s feeling threatened he bursts into the football world’s mentions and refuses to leave. Of course he’d have burner accounts. Mourinho would have a gazillion sock puppets. He’s already the king of turning any fan base that rallies around him into an army of trolls repeating at ever ascending volume whatever dubious claim he’s making about why this week’s disappointing result wasn’t his fault. Jose Mourinho is the king of the trolls, burner accounts are par for that course. https://twitter.com/kevinmccauley/status/1001899773362888704 Injuries and analytics are a combustible brew. There is definitely both a desire for, and a realistic possibility of, advancements through data which can help both spot injuries and prevent them. There’s also a lot of quackery. And, because we’re dealing with science and medicine and data, it’s even harder of non-experts to determine the difference between the two. On a general top down lever there are things teams can do to mitigate injury risks, and lots of the sports science industry is dedicated to developing injury prevention methods. Whether that’s monitoring work load (and having Arsene Wenger ignore that monitoring and play players who are in the “red zone” anyway) or identifying when movement mysteriously drops off, or advising on sleep cycles and eating habits, teams across sports certainly try and ring every last drop of an edge that they can get out of the medical side of data. How much any of this works is an open question though. And in a specific case, like Nabil Fekir’s surgically repaired knee, it’s even more questionable. There’s no way that from the outside anybody is going to know more about Fekir’s health than a good sports medicine team working with him personally. The strongest claim that you might be able to make is that data could eventually be used to raise the kind of red flags that might make you leery enough to want to get a second, third or fourth opinion. https://twitter.com/GregorydSam/status/1001908460752162816 I founded my own short-lived blog in April of 2013, and started writing for Grantland in June of that year. I think what’s surprised me the most has been the distribution of work done in public vs private since then. In American sports a lot of work was done publicly before teams began to take it seriously. Baseball work was around for a long time, and it took a more widespread adoption by the public before teams began committing to using that work to gain an edge for themselves. In football teams, or companies that make their money consulting with teams, stepped into the analytics world much more quickly. The pipeline from talented blogger to super-secret team consultant happened faster than it did in American sports. It actually happened faster than public awareness of analytics happened. Despite all the usual silly battles over real football men, and air conditioned offices, owners have been fairly quick to hire analytics people. Now, that’s different than saying that whoever they hire as any real influence, or that team transfer policy, or management choices have reflected analytics best practices. Managing teams are tricky, effecting change is difficult, and doing analytics well is hard. Put all that together and you’ve got an environment where hiring people is the beginning of the process not the end of it. But, in general I’ve been surprised that the speed of teams doing at least some analytics works seems to have outstripped the speed with which work is viewed as mainstream by fans. Have I been a big enough influence on your writing that you’re going to stretch this mailbag content into a two day thing? --Fake Bill Simmons You better believe it.

Month: May 2018

World Cup Scouting: Iran's Alireza Jahanbakhsh

Iran are going into this year’s World Cup as clear underdogs. But, unlike in past years they have an attacking star, Alireza Jahanbakhsh, to complement their defensive gameplan.

At the 2014 World Cup Iran were long shots to make it out of the group stage, and that hasn't changed this time around. Against Portugal and Spain, the giants of their group, their best chance at doing something noteworthy will probably be through the same compact defensive style they played last time. It's a successful style, one which allowed zero goals during the final round of AFC qualifying until the last matchday. Unlike 2014, however, the attacking talent at Carlos Queiroz's disposal will be more formidable when it comes time to spring counter attacks against opponents.

Iran's biggest star is Jahanbakhsh, the man who tore through the Eredivisie this past season and finished as the league’s top scorer. His performances helped AZ Alkmaar reach 71 points and a 3rd place finish in the table, their highest point tally since winning the title in 2008–09. Watch AZ Alkmaar’s attack and you realize how much it flowed through Jahanbakhsh. Both his monstrous individual shot and creation numbers, 4.5 shots per 90 minutes and 2.5 key passes, demonstrate the dual threat he brings to the table.

It’s undoubtedly true that the wide expanses of open space that exist in the Eredivisie helps attacking players put up big numbers, but there’s still a lot to like about Jahanbakhsh’s creativity. Not only does he pass the statistical test in terms of volume of chances created, but he also passes the eye test in how he creates those chances. Despite having license to drift around, he largely sticks to the wide areas on the right, presenting himself as a passing option. He’s a willing crosser, delivering a high volume of aerial balls for teammates, even if sometimes he'd be better off taking a more efficient option. If the cross isn’t available, he’s good at creating cut backs or hard driven crosses near the edge of the penalty area. He has the ability to find teammates when they’re making runs past an opponent’s defensive line, and even uses more simple passes like basic lay offs effectively. His locker is overflowing with a large catalog of passes and he has the confidence to show them off.

https://gfycat.com/exemplarywelcomebluefish

In general, Jahanbakhsh's passing was quite good this season and there's something to appreciate about how willing he was to try high danger passes. He's great at weighting his passes into the penalty area perfectly so that his teammates can make the additional pass that leads to a shot, similar to how Kevin De Bruyne ran the show with Manchester City this season. Should this be the summer where Jahanbakhsh leaves the Eredivisie, his passing would be his most translatable skill.

It wasn't just his strong passing ability that made Jahanbakhsh a standout figure this season. He also took a lot of shots and scored a lot of goals as a result. Jahanbakhsh is a prolific dribbler, and he constantly makes opponents look silly despite not being a speedster. He was quite adept at creating shots for himself through both galloping runs and shuffling his feet with the ball to evade defenders and set up a shot. Hopefully that particular skill will translate to the World Cup and he'll put some poor unsuspecting defenders on skates.

https://gfycat.com/mammothwebbedduck

There are things to like about what Jahanbakhsh could bring to the table for teams looking for wide players: dynamic passing skills, fludity with his dribbling to create shots for himself or others, but there are flaws to Jahanbakhsh’s game. Because of the heavy usage that he was entrusted with, his shot selection definitely emphasized quantity over quality. It’s fair to wonder how good he’ll be if asked to play a lesser role on a team like Napoli (who he’s been linked to previously). While he used his left foot for combination dribbles and the occasional shot, he only took 11.2% of his shots with his left foot this season and 18.7% over the past four seasons so it’s probably safe to say that he won’t bring extra value for being two footed. Despite the obvious grace that he has when at full bloom and the coordination he has on the ball, it’s still hard to call him an elite athlete, and that might be an issue against higher level competition if he does make a post World Cup summer move. It's hard to tell exactly how much of his impressive numbers, should be chalked up to the massive talent disparity that exists in Holland between the top and bottom clubs along with the defensive frailties in the league.

The odds of Iran making it past the group stage are low all things considered, with Portugal and Spain the odds on favorite to finish 1st and 2nd in some order and Morocco more likely to spring an upset than Iran. That doesn’t mean that Alireza Jahanbakhsh can’t make a name for himself in the three group stage games he’ll get. We’ve seen numerous players in the past who have used a good World Cup showing to catapult themselves to bigger clubs, even if some of those players didn’t have much of a resume preceding those World Cup performances. Jahanbakhsh is different. Although you can poke some holes in his resume, he was arguably the best player in the league and the biggest reason why AZ Alkmaar had their best season in nearly a decade. His contract runs until the summer of 2020 which means that the club could get a big enough transfer fee should they opt to sell. And, if Iran do the unthinkable and make it out of this group, there's a good chance that Jahanbakhsh will be a big reason why.

Images provided by the Press Association

How to Find Footballing Beauty in the Age of Stats

At some point in the early 2000s, the football fan became a pundit. Can you really blame them? Technological advances meant that the most casual hobbyist could put up a blog that looked roughly as reputable as a specialist site and skim information from around the world. Distribution channels — social media, podcasts, and Fan TV-type video — multiplied. It’s a fun hustle for those who can make it work. This development hardly troubled traditional football media, which has always internalized the bare minimum from its challengers whilst fending them off. It did, however, change the language of football fandom. Your average fan now speaks in the sweeping, definitive language of a talking head, interpreting everything — who did what now; who should be signed; who should be fired, because someone should always be fired — through the prism of whether it helps a team. This leaves scant room for idle curiosity, amusement, or one’s own esoteric feelings. It is a view from nowhere that mainly sees transfer rumours and crises. The main difference between radio show callers and talking heads employed by those same stations is microphone quality. The football world’s dirty secret is that most everyone hates Paul Merson while also wanting to be him. All of this has been a boon to Merson et al. — actual pundits with institutional support. Centrist punditry establishes its authority in opposition to perspectives that can be characterized as radically unreasonable. Data analysts, then, are written off as nerds who cannot see the world beyond their spreadsheets. The idea of football as an artistic entertainment — the movement of bodies in space, like ballet, but with a ball — is derided as the fantasy of humanities graduates who never played the sport. These uncharitable conceptions present different schools of thought as antagonists, leaving them even more siloed, their only commonality being the way their niche-ness is used as proof of their invalidity The only winner is the pundit’s faux-everyman routine. This starting point hinders talk of conciliation between the statistical and aesthetic realms,. limiting it to a focus on lowering expectations. It forces a counterargument that claims art is not the enemy of science, and vice versa, and stops there. That construction betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of soccer aesthetics and a curious lack of faith in how analytics can be used. In actuality, data and analytics can help us better discuss and appreciate soccer’s aesthetic dimension. /// Artistic criticism is overwhelmingly the work of considering what a piece evokes. Much of that is introspection, the hard work of thinking about what something made you feel. In turning that feeling into an argument, one then considers the mechanics of the work in question: what did it do to produce this outcome? This is where the language of artistic criticism varies from field to field. One might consider brushstrokes in painting or word choice in poetry or movement in ballet. Using the language of the medium, a reviewer asks whether the work at hand evokes what it set out to evoke, and whether that’s of any value. Or, artlessly, was it good? This analytical work must build upon a shared understanding between writer and reader of what is actually being criticized. In many fields, this is the maligned but useful work of summarizing. It helps the reader of criticism to know that Martin Amis’s The Pregnant Widow is actually about a bunch of childless twenty-somethings. Criticism can be 99 percent figurative but not 100. In some fields, though, such summations are not useful. The plot of Cinderella tells you next to nothing about Prokofiev’s ballet. Stop there and you’re left with exuberant metaphors about grace, elegance yet absolutely no sense of the actual show. Soccer has a similar problem. A scoreline, like the fact that (spoiler alert) Cinderella finishes the ballet with the prince, only tells you how the piece under consideration ends — not what previously happened. Plot summarization is an insufficient starting point in certain forms of artistic criticism, orthogonal to the endeavor being undertaken; you need a language of movement. Enter statistics. Football statistics are not marketed as a language of movement, but that is one of their functions. Before being spun into models, they are inventories of actions performed and positions occupied. The heat maps proliferating in your Twitter timeline and on this website are accounts of spatial relations. Most other systems for thinking about how players occupy space — tactical maps with dots and arrows, lineup graphics, positional names and numbers — are approximate representations of how players should move as opposed to those actually performed in matches. Quants and aesthetes who consider football, like ballet, the study of how bodies move in space, can find common cause in the need for more precise spatial information. Expressionist football writing has regularly built on the foundations laid by prevailing forms tactical analysis. For a time in the early aughts, “false nine” was both a meaningful positional description and metaphysical proposition. This term, which was rooted in a specific observation about movement, birthed thousands of florid meditations about our place in the cosmos. That it can no longer serves either purpose speaks to the ways tactical and aesthetic discourses in football are intertwined. Other terms — the dreaded, ineffable likes of “gegenpressing,” “half spaces” and “between the lines” — followed a similar trajectory. Our appreciation of the subtler pleasures of midfielders who don’t rack up the goals owes a great deal to these concepts. It is the fate of all tactical concepts to eventually become platitudinous. For our aesthetic understanding of football to move forward, descriptions of what is happening on the pitch must also be progressing. The statistical view of football imbues these measures with little more than instrumental value. There are no extra points for flair. Sites like this one differentiate between all sorts of passes, touches, and shots, but those differences only matter insofar as they tell us whether an action helped bring about a goal. In this worldview, creativity and assists are largely synonymous; the former is not an end unto itself. . That is where the aesthetic point of view branches off from statistical analysis. Inefficiency is often more compelling to the aesthete. A touch with the outside of the boot may be profoundly unhelpful to the team, yet oddly compelling. (See also: nutmegs.) Waxing lyrical about strange-but-evocative movements still requires a clear sense of what is happening on the pitch, otherwise it risks becoming meaningless or ascribing qualities to players who do not possess them. The latter problem often manifests as physical, national, and perniciously racial determinism: all small midfielders are twinkle-toed magicians unless they’re English (all-action) or black (powerful); every tall forward is an oafish header merchant. The artistic analysis of football, however, should seek to choose adjectives and metaphors based on what is actually happening on the pitch. Data remains fallible and artistic criticism remains subjective — Charlie Adam's potshots will evoke different sentiments in different observers — but the statistical language of movement puts the undertaking on sounder footing. /// The economics of football media have allowed the schism between the artistic and statistical visions of the sport to persist. In order to survive, all but the most traditional of approaches to the beautiful game tend to be reduced to their most easily monetized forms. Stats, then, are the purview of scouting types, gamblers, and/or almighty nerds. (Hello, dear StatsBomb reader.) The vision of football as a balletic undertaking is monetized in the form of over-sized prints and print products that a certain type of middle-class fan can keep on display. (Disclosure: I’m an editor of Howler Magazine and would love to sell you a luxurious print product.) The difference between these camps is not actually substantive so much as they just don’t communicate. Add in a decade of parochialism and you have our current mess. We have all become quite good at articulating where the statistical and artistic projects diverge and failed to develop language around their considerable common ground. This has only benefited the traditionalist pundits who always sought to cast these camps as dueling irrational extremists. The solution to these problems needn’t be particularly radical. Data analysts do not have to make sense of Wayne McGregor’s Genus and relate it to matches. Analysts interested in artistic performance don’t have to all go out and take remedial R statistical programming lessons. (Both of those options are fun, mind you.) A marked improvement in how we discuss football could be achieved by building a shared understanding of what both projects seek to achieve and how they overlap. We all want to know what actually happens on the pitch, we just use that information towards different ends.

Will Unai Emery Succeed at Arsenal?

Unai Emery is Arsenal’s new head coach. After an exhaustive search Emery emerged as a surprising pick, after the team seemed to be zeroing in on giving Mikel Arteta the first managerial appointment of his career. So, why Emery? And does the move, unexpected as it was, make sense? Manager signings are difficult to evaluate in a vacuum. The job calls for lots of soft, difficult to measure, skills. It’s not just about tactics and substitutions, and monitoring fitness levels. In addition to the Xs and Os managers have to do all of the interpersonal things that keep a team humming. There’s the ego soothing, and man management, the times when a manager has to tell an old hand they just don’t have it anymore and a youngster will be taking their place. The times when they need to yank that youngster from the lineup and not destroy his confidence. They need to keep players involved and invested while dealing with all sorts of very public pressures. It’s hard figuring out who the best person to run a team should be. Arsenal’s selection of Emery, along with naming him head coach and not manager, makes one thing abundantly clear. In the wake of Arsene Wenger, who had total control over every aspect of the club, the team is moving in a new structural direction. Emery will sit within that structure, not on top of it. His job is to handle the team. Other people are responsible for building it. Emery has worked that way before, most famously at Sevilla, but also afterwards at Paris Saint-German and before at Valencia. But, just because he has experience doesn’t mean he’s necessarily the right man for the job.

The Case For Emery

The positive case for Emery starts with his time at Sevilla. He finished fifth twice, then seventh in his final season. That's roughly in line with his budget. On top of that, he managed the team to a sensational three Europa League wins in a row. Knowing exactly how heavily to weight those trophies is a difficult kind of question. Trophies are certainly not the be all, end all. It would not be a meaningfully different reflection of Emery's skills if, instead of a threepeat, Sevilla had lost to Benfica, FC Dnipro or Liverpool in the finals and instead won two out of three. But, it’s also silly to ignore that Emery consistently won matches against a good subset of teams. Three years of Europa League is 39 games (one of those three years involved them dropping down from the Champions League and playing only nine games instead of the usual 15 that finalists would play), or an entire extra season of data. Sevilla's Europa League success is a point in Unai's favor, and a big one. It’s certainly true that Emery’s Sevilla teams were less than inspiring. By his final season there they were downright moribund, especially away from home where they didn’t win a match all season, drawing nine and losing ten. But, how much of that is his fault is an open question. Emery was handed the squad by director of football, and Sevilla legend, Monchi. If the players that Monchi brought in were more defensively oriented, then it was up to Emery to get the most out of them. It’s not unreasonable to suggest that Emery’s style was dictated by his circumstances and not the other way around. It’s possible to view the rest of his career through that lens. Emery managed Valencia for four seasons under difficult conditions. He finished sixth and then third three times in a row. Those teams were certainly accomplished attacking sides. Players like David Villa, David Silva and Juan Mata grew and thrived under Emery at Valencia before being sold off to the highest bidder to stabilize the books. And, while it’s true that after Sevilla Emery struggled in his first season at PSG (nothing is more emblematic of that adjustment than Emery bringing Grzegorz Krychowiak, watching his pet defensive midfielder utterly fail and then being forced to ship him off to find his level at West Bromwich Albion), and then managed to not win the league when faced with a miracle Monaco side, by year two he was much better. It is, of course, easy to be a lot better when the team you’re managing adds Neymar and Kylian Mbappe, but the point is that Emery didn’t shackle them. The team scored 108 goals, up from 83 the year before. Look at the course of Emery’s career and it’s easy to make the case that he’s not particularly defensive minded, it’s just that his most notable success came with his most defensive sides.

The Case Against Emery

It’s also possible to look at those facts and see exactly the opposite story. Valencia weren’t that high scoring, they notched between 59 and 64 goals per year when he was there. They did it with a bevy of talented attacking players too, all of whom went on to star at the biggest clubs in the world. Maybe they should have been even higher scoring than they were. The same is certainly true of PSG in Emery’s first year. Trying to instill defensive structure was clearly not the best plan, and it wasn’t until he was handed two of the best attackers in the world that he consented to take the reins off. The concern for Emery at Arsenal would be that his inclination is to be defensive, and that it’s only when he is overwhelmed by talent that gives him no choice that he opens up. Will he look at Alexandre Lacazette, Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang, and Mesut Ozil and see a team that has no choice but to play upbeat attacking football, or will he revert to his instincts and try to structure the team more conservatively even if it means stifling them. Then there’s the Europa League mystique. Whatever tournament magic Emery had, it wore off quickly with PSG. He oversaw one of the greatest collapses in history against Barcelona one season and then meekly rolled over for Real Madrid the next. Sure, winning three in a row with Sevilla was impressive, but two years, and two Champions League failures on, maybe that was a reflection of Sevilla’s squad, more than Emery’s magic. Put it all together and it adds up to a fine, if overly conservative, manager, a man who was in the right place at the right time to steward Monchi’s collection of talent to a unique achievement, but nothing more. A boring, slightly better than average manager is not exactly a ringing recommendation for Arsene Wenger’s successor.

The Wait and See Game

The problem with evaluating Arsenal’s Emery hire is that both of those narratives are equally accurate from the outside. They are simply differently constructed versions of the same set of facts. Is Emery a practical manager who can manage a variety of different styles depending on the talented he’s presented with? Maybe. He also might be a fundamentally conservative manager who only attacks when his talent deck is so stacked he has absolutely no other option, a man whose conservative tendencies just happened to make him the perfect steward for the undervalued talent Monchi assembled at Sevilla. There’s no way to definitively answer the question now. Instead the two possibilities provide a useful framework for evaluating Emery’s early days at Arsenal. What kind of players is Arsenal management getting for Emery? What sorts of tactical choices is he making during an abbreviated post World Cup preseason? Is he playing formations that look like they might accommodate both Lacazette and Aubameyang, even if they aren’t necessarily on the field? Or, is he playing more rigid one striker looks? Does the team seem to be preparing for a future with one forward and a single creative midfielder behind them? There are the kinds of issues that will define Emery’s early days at the club. Hiring managers is a messy business. There’s lots of uncertainty. It’s exceedingly difficult to isolate what exactly is important and necessary for a new manager, even a manager with a substantial track record, to succeed with a new club. It’s impossible to answer the question of whether Emery will turn out to be a good hire ahead of time. All we can do is start the evaluation process by asking the right questions. Images provided by the Press Association

Champions League Spotlight: How Roberto Firmino and Mohamed Salah Propel Liverpool

The good folks here at StatsBomb are very excited about the Champions League final. We’re so excited that we wanted to make sure we got some of our cool new toys out in public view before the last match of the season kicks off. This involved making a compromise or two. The data isn’t quite done yet. Such is life in big data city. Who knew launching a technology company could be so hard? But, rather than deprive the people of what they want (and we are quite confident that what the people want is pictures with bright colors and lots of squiggly lines), we just decided to make do with some slightly incomplete data. Here, without further ado, are a bunch of cool pictures that help explain why Liverpool are so dang good. They just happened to be drawn from a slightly incomplete picture of 32 matches of Premier League data rather than waiting for our diligent data mice to finishing sewing the last six games in.

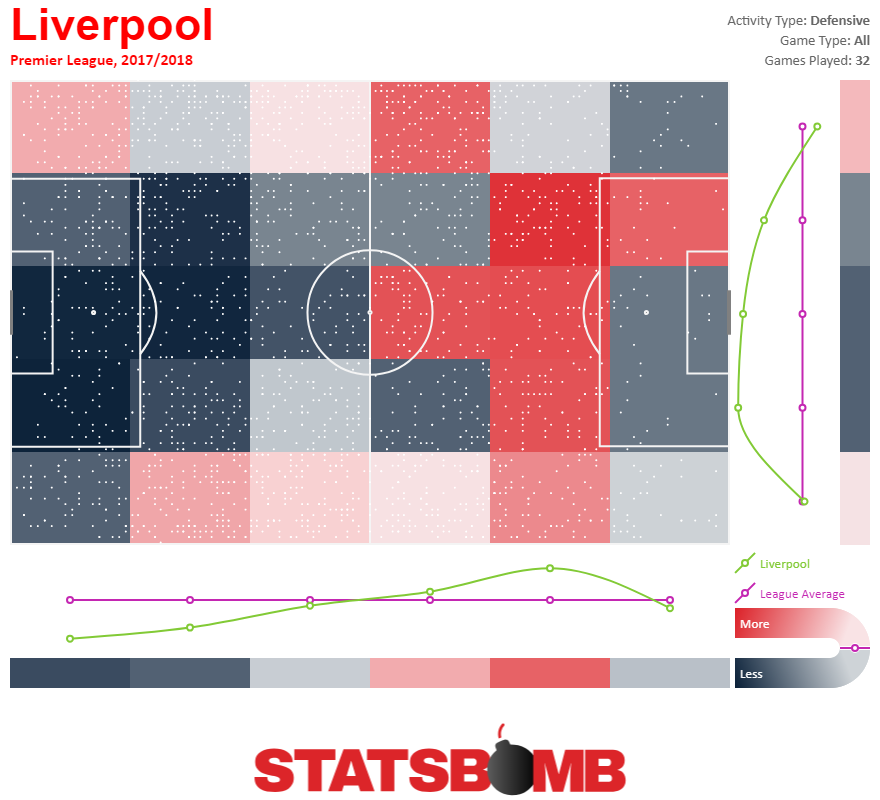

Liverpool’s Defensive Pressure.

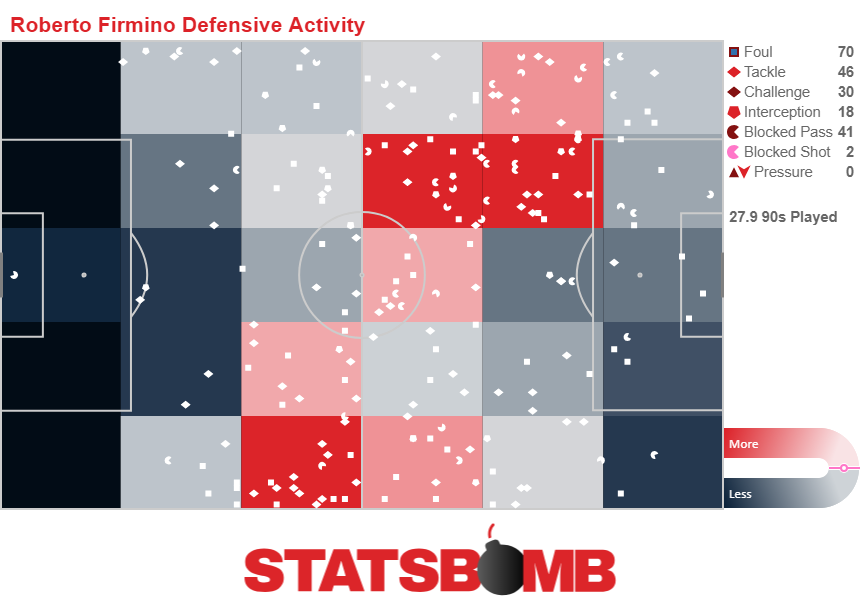

We’ve talked about a lot about how we record pressure in matches. Liverpool are a perfect example of how doing that helps paint a fuller data picture of what a team is actually doing on the pitch. Here’s what Liverpool look like as a defensive team without pressures included.  It paints a pretty good picture. The degree to which Liverpool bother opponents deep in their own territory is apparent. Looking at that map it doesn’t get anything noticeably wrong. Now, let’s look at a map with pressures included.

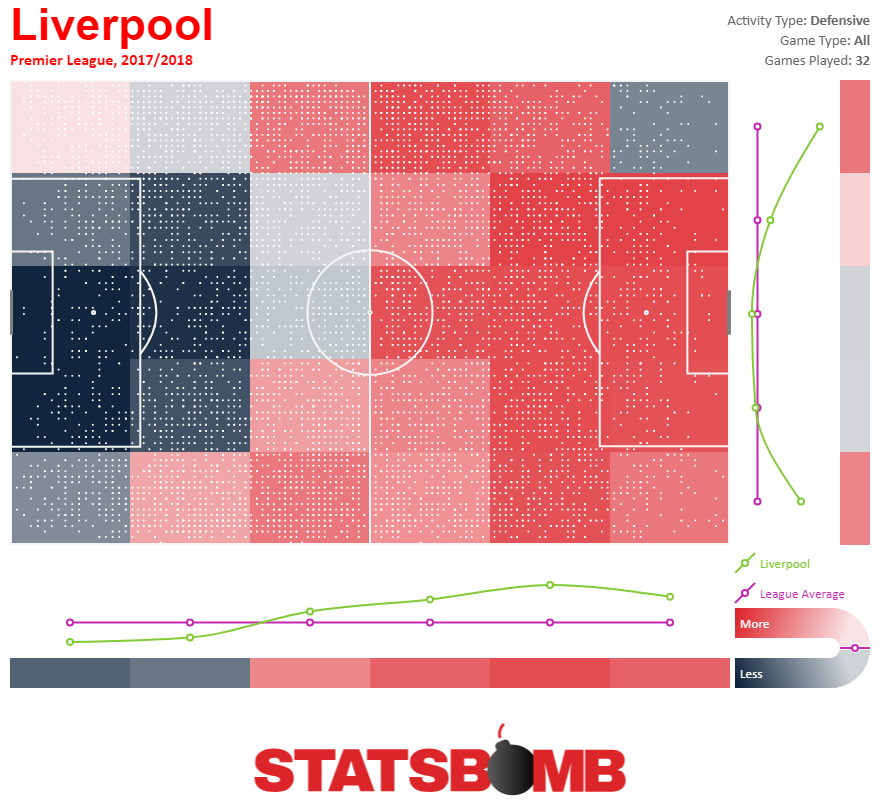

It paints a pretty good picture. The degree to which Liverpool bother opponents deep in their own territory is apparent. Looking at that map it doesn’t get anything noticeably wrong. Now, let’s look at a map with pressures included.  Yowser. This really makes clear how aggressively Liverpool are taking the game to opponents. Those on ball actions don’t come from nowhere. Liverpool contest everything across the field, and it’s those actions that force opponents back and into the kinds of mistakes that ultimately lead to turnovers and easy opportunities for Jurgen Klopp’s band of merry pressers to take advantage of. Now, let’s look at the same dynamic on an individual player level. Here’s Roberto Firmino’s defensive actions without pressures included.

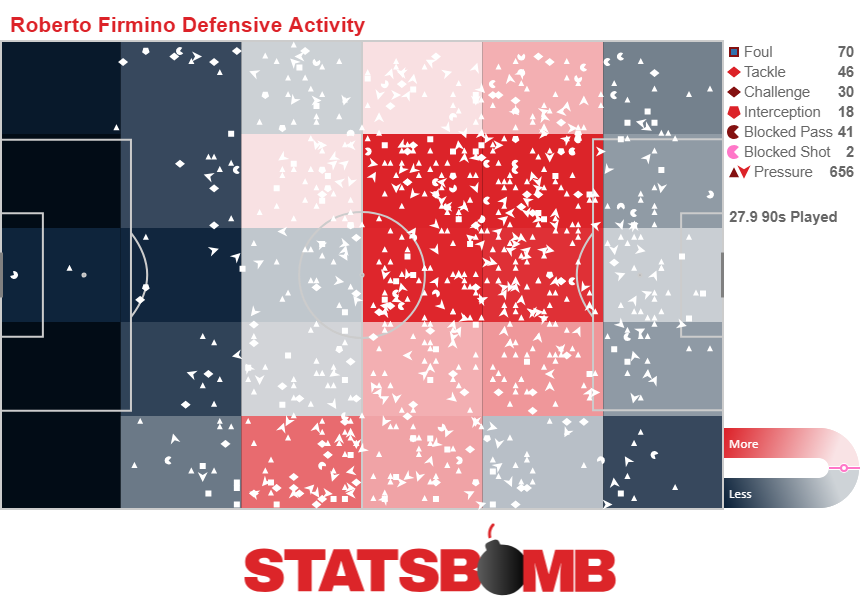

Yowser. This really makes clear how aggressively Liverpool are taking the game to opponents. Those on ball actions don’t come from nowhere. Liverpool contest everything across the field, and it’s those actions that force opponents back and into the kinds of mistakes that ultimately lead to turnovers and easy opportunities for Jurgen Klopp’s band of merry pressers to take advantage of. Now, let’s look at the same dynamic on an individual player level. Here’s Roberto Firmino’s defensive actions without pressures included.  Firmino has rightfully garnered a reputation as a player willing to do tremendous amounts of defensive work for Klopp’s side, exactly the kind of high motor ball harassing forward a good pressing team needs. This particular chunk of data doesn’t disprove that, but it doesn’t exactly prove it either. It shows a player who is quite active in a fairly limited forward zone. Clearly he’s committed defensively, but the breadth of his commitment is still mostly something that data didn’t capture. And now to add in the pressure.

Firmino has rightfully garnered a reputation as a player willing to do tremendous amounts of defensive work for Klopp’s side, exactly the kind of high motor ball harassing forward a good pressing team needs. This particular chunk of data doesn’t disprove that, but it doesn’t exactly prove it either. It shows a player who is quite active in a fairly limited forward zone. Clearly he’s committed defensively, but the breadth of his commitment is still mostly something that data didn’t capture. And now to add in the pressure.  Hey there Bobby! That’s a more accurate picture of the player we keep seeing on the pitch. Add in pressure events and Firmino’s defensive range and determination becomes much more apparent. All this pressing information is contained on Liverpool’s defensive radar too.

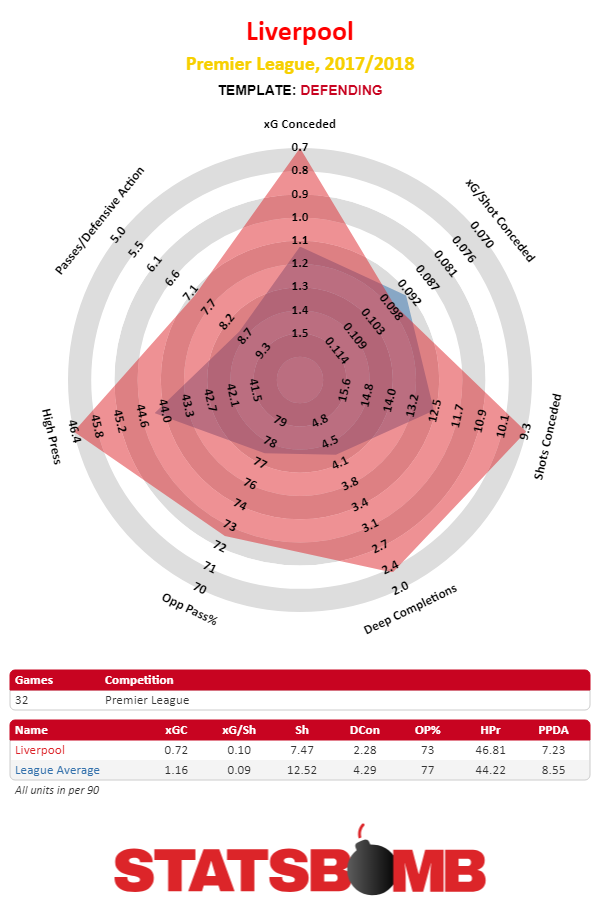

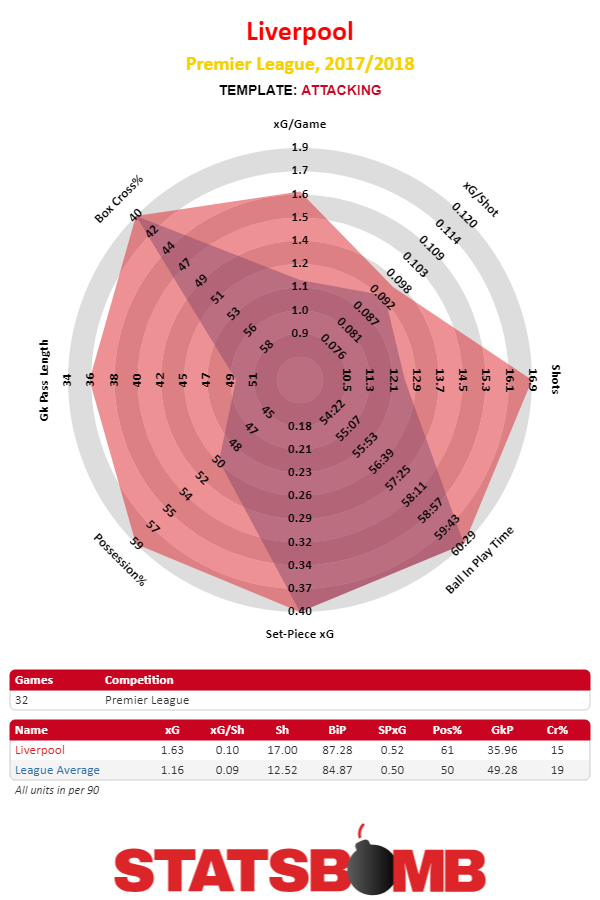

Hey there Bobby! That’s a more accurate picture of the player we keep seeing on the pitch. Add in pressure events and Firmino’s defensive range and determination becomes much more apparent. All this pressing information is contained on Liverpool’s defensive radar too.  The radar in particular shows Liverpool with a very high defensive pressure rating while only having a mediocre pass per defensive action score. That, in part, is because of the presence of all those pressures. Liverpool have a cohesive pressing unit that makes life difficult for opponents even when they aren’t tackling, intercepting or otherwise actively taking the ball away. The one possible fly in the ointment here is that Liverpool’s xG per shot conceded is below average. It’s tempting to look at that is a result of the tradeoffs a pressing team makes, a concession that when the press is broken opponents will get very good shots. It turns out that’s not the case for Liverpool, at least not this season. The result of all of Liverpool’s effective pressure is that the team simply doesn’t give up a lot of shots of any variety. They restrict opponents bad shots, and they also don’t concede very many golden chances either. Opponents simply have a very hard time creating anything against this Liverpool defense.

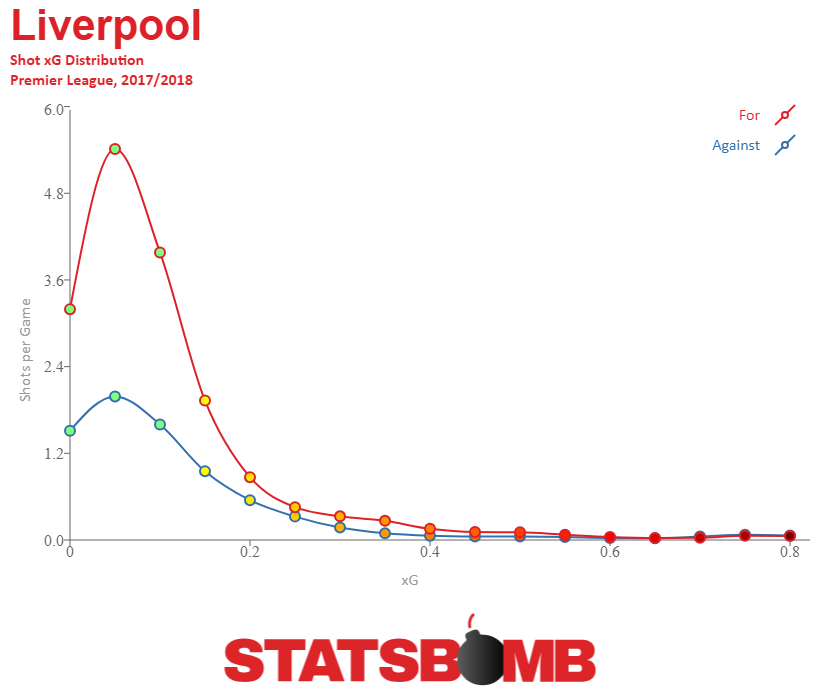

The radar in particular shows Liverpool with a very high defensive pressure rating while only having a mediocre pass per defensive action score. That, in part, is because of the presence of all those pressures. Liverpool have a cohesive pressing unit that makes life difficult for opponents even when they aren’t tackling, intercepting or otherwise actively taking the ball away. The one possible fly in the ointment here is that Liverpool’s xG per shot conceded is below average. It’s tempting to look at that is a result of the tradeoffs a pressing team makes, a concession that when the press is broken opponents will get very good shots. It turns out that’s not the case for Liverpool, at least not this season. The result of all of Liverpool’s effective pressure is that the team simply doesn’t give up a lot of shots of any variety. They restrict opponents bad shots, and they also don’t concede very many golden chances either. Opponents simply have a very hard time creating anything against this Liverpool defense.  Teams' average xG per shot isn't higher against Liverpool because they creati more good chances. They don't. Rather, it's because in addition to preventing good chances Liverpool also prevent a high number of bad ones. Salah Days It will not surprise anybody with a pulse that Mohamed Salah is the central hub of Liverpool’s attack. The attack does almost everything well. They keep possession and pass the ball from back to front and take an avalanche of chances. The only place where they might get a slight demerit is the average shot quality of their chances, but that's largely a function of how often defenses sit deep and make themselves difficult to break down. Sometimes there’s not much to do but hammer away with mediocre chances until one finally goes in.

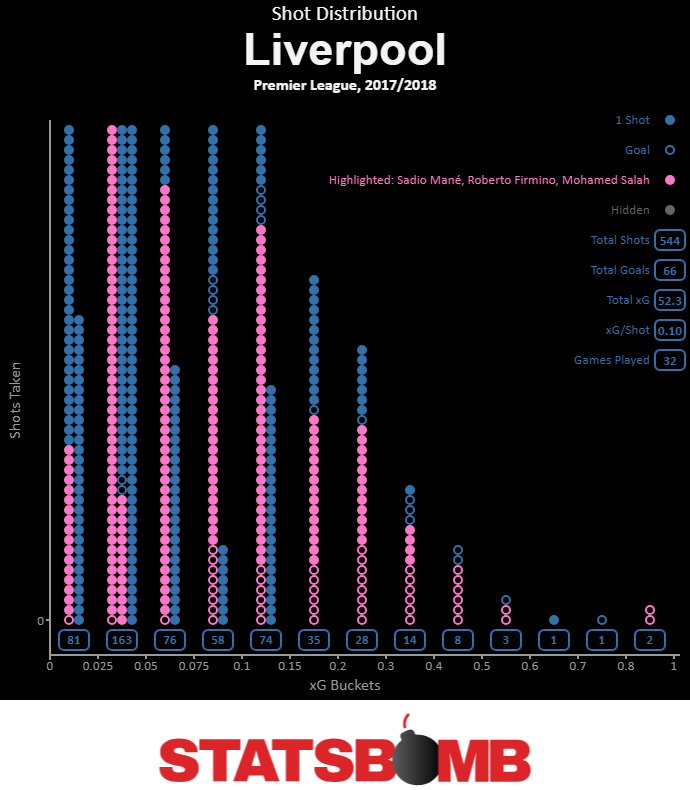

Teams' average xG per shot isn't higher against Liverpool because they creati more good chances. They don't. Rather, it's because in addition to preventing good chances Liverpool also prevent a high number of bad ones. Salah Days It will not surprise anybody with a pulse that Mohamed Salah is the central hub of Liverpool’s attack. The attack does almost everything well. They keep possession and pass the ball from back to front and take an avalanche of chances. The only place where they might get a slight demerit is the average shot quality of their chances, but that's largely a function of how often defenses sit deep and make themselves difficult to break down. Sometimes there’s not much to do but hammer away with mediocre chances until one finally goes in.  The majority of the goal scoring thrust obviously comes from the front three of Salah, Firmino and Sadio Mane.

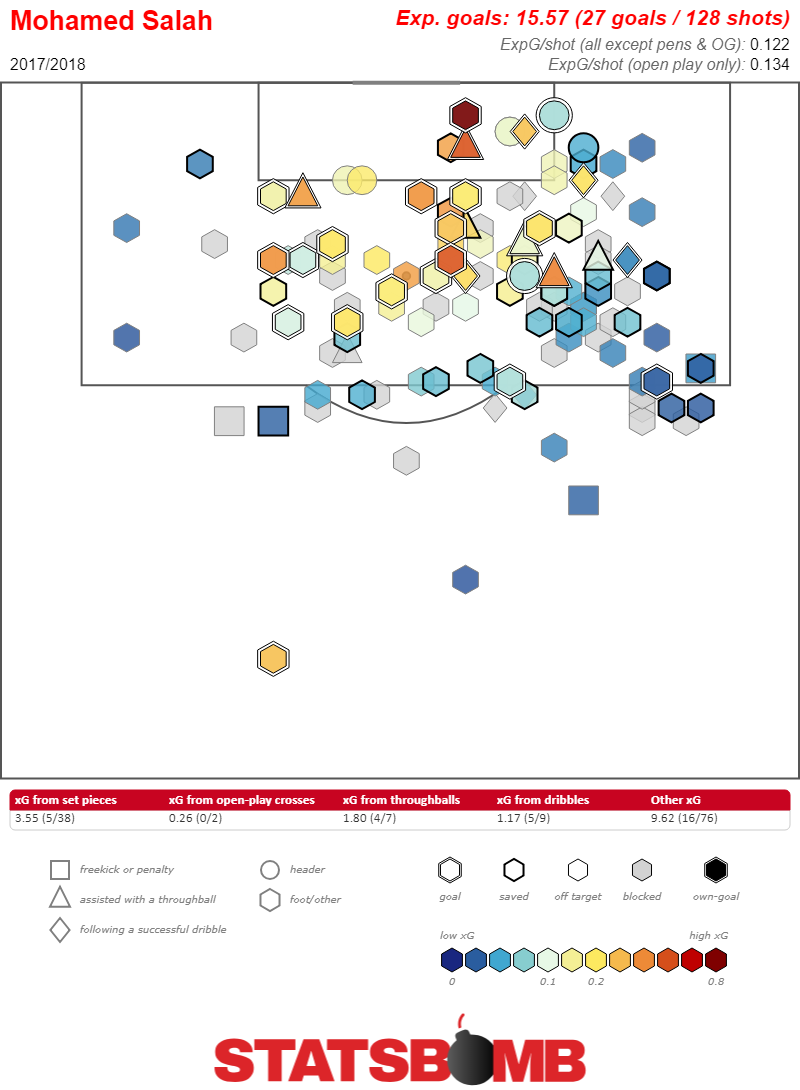

The majority of the goal scoring thrust obviously comes from the front three of Salah, Firmino and Sadio Mane.  And, of course, Salah in particular has had an absolutely unstoppable season. His scoring numbers crashing into the box from his right side wide forward position are enormous. It’s not just that he’s cutting off the right side and onto his stronger left foot to terrorize the defense, it’s that when he does that he consistently gets deep into the heart of the backline trying to stop him. Ineffective wide forwards end up cutting in and shooting from the edge of the 18. Salah, on the other hand, lives six to twelve yards out.

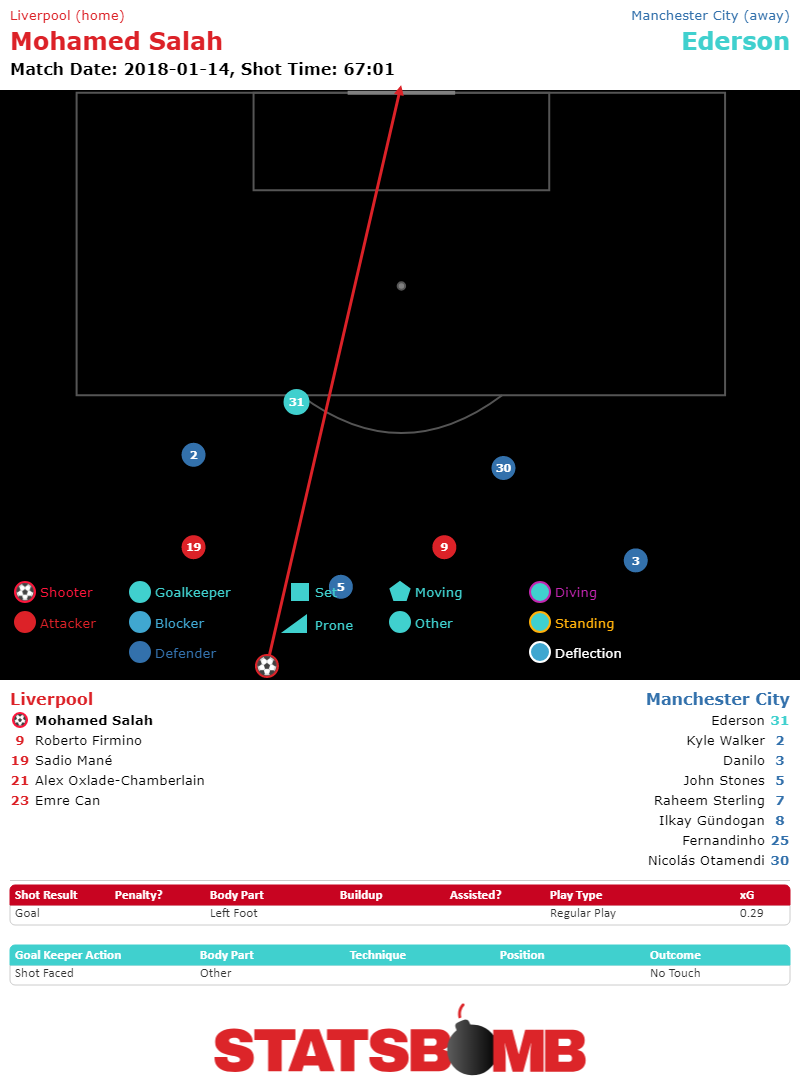

And, of course, Salah in particular has had an absolutely unstoppable season. His scoring numbers crashing into the box from his right side wide forward position are enormous. It’s not just that he’s cutting off the right side and onto his stronger left foot to terrorize the defense, it’s that when he does that he consistently gets deep into the heart of the backline trying to stop him. Ineffective wide forwards end up cutting in and shooting from the edge of the 18. Salah, on the other hand, lives six to twelve yards out.  Oh, in case you’re wondering why that one Salah goal he scored from the parking lot seems like a good chance. It’s because it actually looked like this.

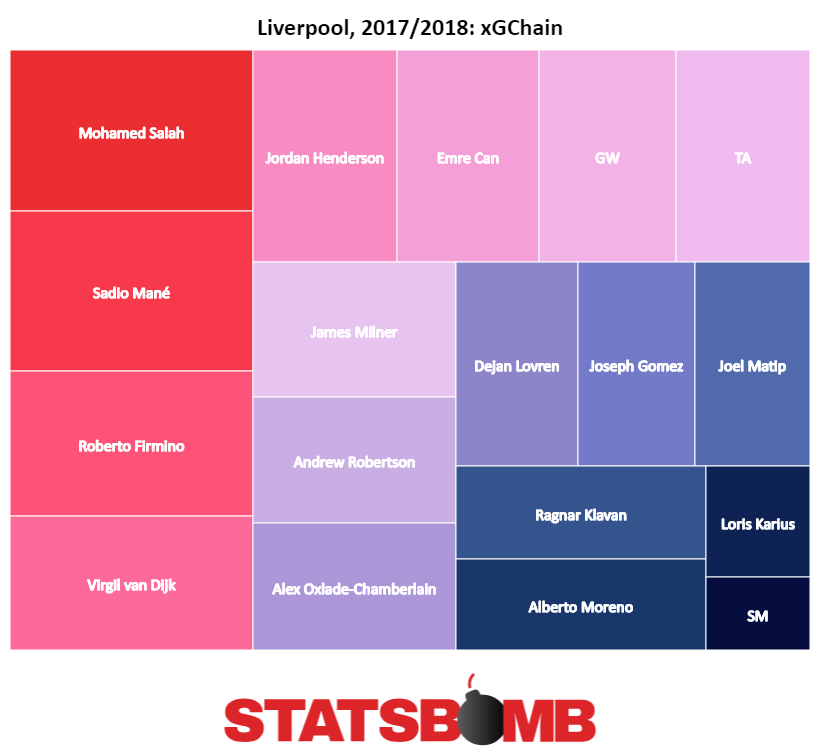

Oh, in case you’re wondering why that one Salah goal he scored from the parking lot seems like a good chance. It’s because it actually looked like this.  Despite Salah’s magnificent scoring season, Liverpool’s attack remains highly balanced. Looking at the distribution of the team's xGChain per 90 (among players with more than 900 minutes played because I'm mean and wanted to deny the departed Coutinho any glory) paints a picture of a team operating with Salah as the first among equals rather than a lone superstar. He might get to finish a disproportionate number of the moves, but Salah is standing on the shoulders of all of his teammates working to find good opportunities.

Despite Salah’s magnificent scoring season, Liverpool’s attack remains highly balanced. Looking at the distribution of the team's xGChain per 90 (among players with more than 900 minutes played because I'm mean and wanted to deny the departed Coutinho any glory) paints a picture of a team operating with Salah as the first among equals rather than a lone superstar. He might get to finish a disproportionate number of the moves, but Salah is standing on the shoulders of all of his teammates working to find good opportunities.  So, that’s Liverpool. They’re a hard pressing, high scoring, beast of a unit. Now, we have more ways than ever to show how they do it. Images provided by the Press Association

So, that’s Liverpool. They’re a hard pressing, high scoring, beast of a unit. Now, we have more ways than ever to show how they do it. Images provided by the Press Association

StatsBomb Data Launch - Actions Under Pressure

Embedded below is the final video of our presentations from the StatsBomb launch event. StatsBomb CTO Thom Lawrence discusses Actions Under Pressure. Thom looks at all the ways that pressure from defenders impact the team with the ball, and what we can learn from recording those events. He examines how we can look for weak links, which players are able to beat pressure most effectively, and much much more.

World Cup Scouting: Serbia's Andrija Zivkovic

Buying players based on summer tournament performances is common practice. It's also a bad idea. Eye-catching performances under extremely specific conditions, over the course of only five or six matches, will often turn into overblown transfer fees and contracts that seem to last forever. That’s why it’s important to highlight lesser known players before the World Cup and take a deeper look who actually had impressive seasons and might end up breaking out in Russia for the world to see. Andrija Zivkovic is exactly that type of player.

Zivkovic plays for Serbia, a team with a solid talent pool. Thanks to a soft path to qualification, they competed with Ireland, Wales and Austria for the top two spots in their group, Serbia managed to earn a decent World Cup draw. While Brazil is likely to win Group E, second place is wide open. Serbia will only have to get by Switzerland and Costa Rica to advance.

Initially it seemed like Zivkovic might play a bit part at best. Serbia’s squad is mostly composed of players in or past the prime years of their careers. The eleven most used players by now former manager Slavoljub Muslin during qualification, where they topped their group with 21points while only losing once, average the ripe ol’ age of 29. This will, therefore, be the last tournament for a sizable portion of this group.

The appointment of a new manager, Mladen Krstajić, after the end of the qualifiers led to the recent integration of a few more interesting, younger, talents into the side. That includes not only Zivkovic, but the incredibly hyped Sergej Milinkovic-Savic as well, who, despite having over 7000 Serie A minutes under his belt, only debuted for Serbia in a friendly in November.

Before this year Zivkovic might have been best known as a Football Manager legend. He moved from Partizan to Benfica on a free transfer in the summer of 2016. While his talent was clear every time he stepped on the pitch, he was never given a chance at getting consistent playing time until early 2018. An injury to Filip Krovinovic, who otherwise could’ve been a World Cup revelation himself, left the team with a hole in midfield and no option to fill it other than, as it turns out, their most talented player. Zivkovic, a left-footed 21 year old who spent most of his career playing from wide, starred throughout the second half of the campaign as the left-sided center-midfielder in a 4-3-3.

His role was all about freedom: to roam into either of the wide areas with or without the ball, to arrive in the box in support of the lone striker or to aid in build-up. Zivkovic became the team’s creative dynamo and the numbers reflect that in a way that his 3 goals and 4 assists don’t fully capture.

Zivkovic’s 2.2 key passes per 90 minutes ranks him third best in the league for “central” players with over 1000 minutes, and the fact that 1.7 of those key passes came from open play situations makes that all the more valuable. His assists were all in repeatable contexts and the sheer number of situations he created for his teammates are proof of that.

He’s the kind of player to show up well in all kinds of passing models, completing a rather large and diverse number of difficult passes. His freedom to roam means he’s often compelled to drop and aid in build-up from deeper, where he pulls off longer side-switching passes with ease. He also moves wide where he executed 1.6 crosses per 90 – top 10 in the league – with a solid 26% accuracy.

Zivkovic is technically sublime. He passes the eye test with flying colors. His ability to use different parts of his foot: from the outside to the side and across the laces helps his passing range be as diverse as possible and gives him a ton of solutions even when space is limited. Often, he’ll delay a pass, making his own task more difficult, just so he can assure his teammate’s run will align with the timing of the ball.

Give him the ball in the final third and he’ll find a way to get his team up close and personal with the opposing goalkeeper. And, as much as the definition of “through-ball” leads to a snow-ball of questions for stats providers across this sport, the lists of players who play the most of them always seem to pick out guys on the upper echelon of technique. Zivkovic leads the league with 0.3 per 90.

His capacity to dribble is of major importance too. Beyond just beating players one against one and being able to unravel himself from tight situations –which he does, with two completed take-ons per 90 and around a 65% success rate, there's a lot of value in being able to carry the ball from a deep position all the way to the final third. That’s true even if the situation doesn't involve overcoming a player with any sort of YouTube-montage-worthy skill-move. He's sublime at it, capable of bursts of acceleration to create separation from his marker and put his ball-carrying abilities to use.

Zivkovic is by no means perfect.

He can still improve when it comes to his box arrivals and has some awareness issues when having his back towards goal – too often choosing against turning into space simply because he didn’t realize said space was there. But, his positional change has helped accentuate his strengths and hide his weaknesses.

Serbia used a 3-4-3 during the entirety of the qualification process, but over the last friendly breaks the new manager has taken out one of the center-backs to add a third midfielder in a 4-2-3-1 or 4-3-3 set-up depending on personnel. The line-up could well end-up accommodating Milinkovic-Savic ahead of Serbian mainstay Nemanja Matic and Crystal Palace’s Luka Milivojevic. In this set-up Zivkovic is a front-runner to wreak havoc off the bench – also because he can fill in any creative role, either from wide or central – and to potentially unlock defenses such as Costa Rica’s.

Zivkovic is under contract with Benfica until 2021, but the constant need to sell by the Portuguese side combined with the fact that the Serb is one of the few valuable assets that could bring in revenue during this window, will make this a very interesting case to follow. Serbia have an intriguing national team and it will be interesting to see how their younger talent will stand-out among a solid foundation of personnel. Brazil will still likely tear through their group, but the Eastern European side has enough about them to overcome Costa Rica and Switzerland and finish in second place if they play their cards right. And if Zivkovic impresses during the process and earns himself a big money move, it will be justified not simply because of his performances this summer, but based on everything he accomplished before it.

How StatsBomb Data Helps Measure Counter-Pressing

The concept of pressing has existed in football for decades but its profile has been increasingly raised over recent years due to its successful application by numerous teams. Jürgen Klopp and Pep Guardiola in particular have received acclaim across their careers, with pressing seen as a vital component of their success. There are numerous other recent examples, such as the rise of Atlético Madrid, Tottenham Hotspur and Napoli under Diego Simeone, Mauricio Pochettino and Maurizio Sarri respectively.

Alongside this rise, public analytics has sought to quantify pressing through various metrics. Perhaps the most notable and widely-used example was ‘passes per defensive action’ or PPDA, which was established by Colin Trainor and first came to prominence on this very website. Anecdotally, PPDA found its way inside clubs and serves as an example of public analytics penetrating the private confines of football. Various metrics have also examined pressing through the prism of ‘possessions’, which Michael Caley has put to effective use on numerous occasions. Over the past year, I sought to illustrate pressing by quantifying a team’s ability to disrupt pass completion. While this was built on some relatively complex numerical modelling, it did provide what I thought was a nice visual representation of the effectiveness of a team’s pressing.

While the above metrics and others have their merits, they tend to ignore that pressing can take several forms and are biased towards the outcome, rather than the actual process. The one public example that side-steps many of these problems is the incredible work by the Anfield Index team through their manual collection of Liverpool’s pressing over the past few seasons but this has understandably been limited to one team.

Step-forward the new pressure event data supplied by StatsBomb Services. This new data is an event that is triggered when a player is within a five-yard radius of an opponent in possession. The radius varies as errors by the opponent would prove more costly, with a maximum range of ten-yards that is usually associated with goalkeepers under pressure. As well as logging the players involved in the pressure event and its location, the duration of the event is also collected.

The data provides an opportunity to explore pressing in greater detail than ever before. Different teams use different triggers to instigate their press, which can now be isolated and quantified. Efficiency and success can be separated from the pressing process in a number of ways at both the team and player-level. Such tools can be used in team-evaluation, opposition scouting and player recruitment.

One such application of the new data is to explore gegenpressing or counter-pressing, which is the process where a team presses the opposition immediately after losing possession. The initial aim of counter-pressing is to disrupt the opponent’s counter-attack, which can be a significant danger during the transition phase from attack-to-defence when a team is more defensively-unstable. Ideally possession is quickly won back from the opponent, with some teams seeking to exploit such situations to attack quickly upon regaining possession. Five seconds is often used as a cut-off for the period where pressure on the opposition is most intensely applied during the counter-press.

The exciting new dimension provided by StatsBomb’s new pressure data is that the definition of counter-pressing you would find in a coaching manual can be directly drawn from the data i.e. a team applies pressure to their opponent following a change in possession. The frequency at which counter-pressing occurs can be quantified and then we can develop various metrics to examine the success or failure of this process. Furthermore, we can analyse counter-pressing at the player-level, which has been out-of-reach previously.

The figure below illustrates where on the pitch counter-pressing occurs based on data from 177 matches from the Premier League this past season. The pitch is split into six horizontal zones and is orientated so that the team out-of-possession is playing from left-to-right. The colouring on the pitch shows the proportion of open-play possessions starting in each zone where pressure is applied within five seconds of a new possession.

The figure illustrates that pressure is most commonly applied on possessions starting in the midfield zones, with marginally more pressure in the opposition half. Possessions beginning in the highest zone up the pitch come under less pressure, which is likely driven by the lower density of players in this zone on average. Very few possessions actually begin in the deepest zone and a smaller proportion of them come under pressure quickly than those in midfield.

From a tactical perspective, pressing is generally reserved for areas outside of a team’s own defensive third. The exact boundary will vary but for the following analysis, I have only considered possessions starting higher up the pitch, as denoted by the counter-pressing line in the previous figure.

In the figures below, the proportion of possessions in the counter-pressing zones where pressure is applied within five seconds is referred to as the ‘counter-pressing fraction’. In the sample of matches from the Premier League this season, a little under half (0.47) of open-play possessions come under pressure from their opponent within five seconds. At the top of the counter-pressing rankings, we see Manchester City, Tottenham Hotspur and Liverpool, which is unsurprising given the reputations of their managers. At the bottom end of the scale, we find a collection of teams that have mostly been overseen by British managers who are more-known for a deep-defensive line.

On the right-hand figure above, the strong association between counter-pressing and possession is illustrated, with the two showing a high correlation coefficient of 0.86 in this aggregated sample. Interpreting causality here is somewhat problematic given the likely circular relationship between the two parameters; teams that dominate possession may have more energy to press intensively, leading to a greater counter-pressing fraction, which would lead to them winning possession back more quickly, which will potentially increase their possession share and so on. The correlation is weaker for individual matches (0.36), which hints at some greater complexity and is something that can be returned to at a later date.

Perhaps the most interesting finding in the above figures is Burnley’s high counter-pressing fraction. The majority of analysis on Burnley has focused on their defensive structure within their own box and how that affects their defensive performance in relation to expected goals (xG). The figure illustrates that Burnley employ a relatively aggressive counter-press, especially in relation to their possession share.

Examining Burnley’s counter-pressing game in more detail reveals that they counter-press 18 possessions per game, which is above average and only slightly lower than Manchester City. However, they only actually regain possession within five seconds 2.5 times per game, which falls short of what you might expect on average and falls below their counter-pressing peers. In terms of the ratio between their counter-pressing regains and total counter-pressing possessions, they sit 17th on 14%.

Burnley’s counter-press is the fourth least-effective at limiting shots, with 13% of such possessions ending with them conceding a shot compared to the average rate of 10%. However, one thing in their favour is that these possessions are typically around the league average in terms of their length and speed of attack, which will allow Burnley to regain their vaunted defensive organisation prior to conceding such shots.

The more dominant discourse around pressing is as an attacking rather than defensive weapon, so narratives are often formed around teams that regularly win back the ball through pressing and use this to generate fast attacks e.g. Liverpool and Tottenham Hotspur. As a result, a team like Burnley who seemingly employ counter-pressing as a defence-first tactic to prevent counter-attacks and slow attacking progress may be overlooked.

Burnley’s manager, Sean Dyche, has typically been lumped-in with the tactical stylings of the perennially-employed British managers who aren’t generally associated with pressing tactics. Dyche was reportedly most impressed by the pressing game employed by Guardiola’s Barcelona and he has seemingly implemented some of these ideas at Burnley. He has instilled an approach that combines counter-pressing and a low-block with numbers behind the ball, which is a neat trick to pull-off; Diego Simeone and Atlético Madrid are perhaps the more apt comparison given such traits.

The above analysis illustrates the ability of StatsBomb’s new pressure event data to illuminate an important aspect of the modern game. Furthermore, it is able to do this in a manner that directly translates tactical principles, separating underlying process and outcome, which is a giant step-forward for analytics. It also led to an analysis discussing the similarity between Guardiola’s legendary Barcelona team and Sean Dyche’s Burnley, which was probably unexpected to say the least.

This is just a taster of what is possible with StatsBomb’s new data. There's more information in this presentation from the StatsBomb launch event and you can expect more analysis to appear over the summer and beyond.

The Dual Life of Expected Goals (Part 2)

Yesterday, in part one, we talked about how expected goals came to be. Today, we’re going to look at what StatsBomb is doing with it.

The way the world started using xG for single games, combined with the shortcomings of that usage, presents an awkward point. Given how the stat was constructed, and the way it works, we know a lot more about how it operates mechanically than we do about why.

Broadly, teams eventually score and concede roughly the number of goals they're statistically predicted to, but the day to day decision making and minutiae of managing a team, the actual process that results in goals and expected goals ending up close together is largely opaque. Hopefully, StatsBomb can start pulling back that curtain. And to do that, we need to talk about our favorite thing. It's data time (but not Lore, never Lore).

The Limited Eyesight of Data

Much of the work that goes into building xG models has to do with getting around the limits of the data available. Location is recorded, so is the body part used to take a shot, the kind of pass that led to the shot, any instances where the player dribbled around a defender, and a handful of other specific events. Still, using on ball data is like trying to figure out what's in a giant warehouse with a tiny flashlight. What you see in front of you offers clues as to what you can’t. But you’re still left doing guesswork to fill in the blanks.

Did the shot come after a fast attack?

If so that means the shot ends up being a little bit better on average than after a slow one. Why? Because the speed of the attack means that the defenders were likely less set and more likely out of position. Did the player dribble by the keeper before the shot? Well then that gets a big boost because that means the goal is most likely wide open. Was it from a through ball? Great, there are probably less defenders in the way, give that shot a boost. And on and on and on.

Clues in the data let analysts extrapolate out to what they can't see. Additionally one thing that data collectors have done to help build more data sets is use some sort of signifier to indicate if a chance is an extremely good one. Recognizing that nothing in the data set will distinguish particularly good chances from similar looking but mediocre ones, data collection leaned on creating a label that let everybody know

“HEY! LOOK OVER HERE! THIS CHANCE WAS REALLY GOOD!”

Tautologically, knowing that a chance was good helps xG models determine if a chance was good. It's also a bit of outside information being slipped into recorded data. Big chances aren't a depiction of what's going on on the pitch, rather they're a tiny bit of analysis used to supplement it, a recognition, and attempt to compensate for, the necessarily incomplete data. StatsBomb isn’t doing that.

We’re Going to Need a Bigger Flashlight

Rather than use a big chance moniker, StatsBomb is trying to do a better job including more information about every single chance created. To that end, StatsBomb data, as Ted Knutson talked about in his presentation at the launch event, records all sorts of stuff. One big difference is defensive positioning. Any defender on screen when a shot gets taken gets recorded. The same is true of keeper positioning and shot velocity. All of these are additional pieces of information that help illuminate what’s going on on the pitch.

The reason to do this isn’t necessarily because it will make an xG model more predictive (though hopefully once there’s lots of data in, and the testing is done, and the smart people who do the number things are done doing their number things it will), but rather that SBxG (StatsBomb xG, get it? We're really good at naming things here.) will better describe reality. Let’s take an example. Back in March, Leicester City hosted Bournemouth.

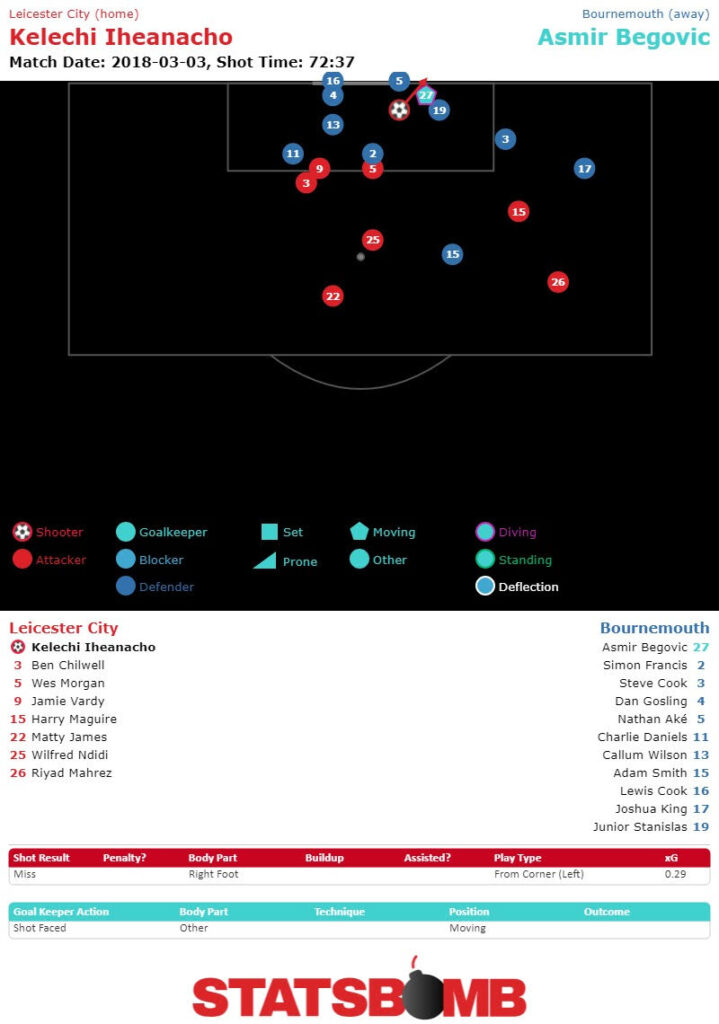

In the 73rd minute, Leicester won a corner. After the ball ricocheted around, Harry Maguire managed to pass it to Kelechi Iheanacho, who had the ball on his right foot directly in front of the goal. Somehow he managed to put it wide. This is a chance it’s easy to rate quite highly. He’s right on top of goal, he’s got it on his foot, he had the ball past to him from nearby instead of reacting to a scramble. All pretty good indicators. Here’s what the shot looks like to a typical xG model. It ranked it 0.93.

Here’s what it looks like to StatsBomb.

And here’s what the play looked like to watch.

Pretty different. Should we do another one?

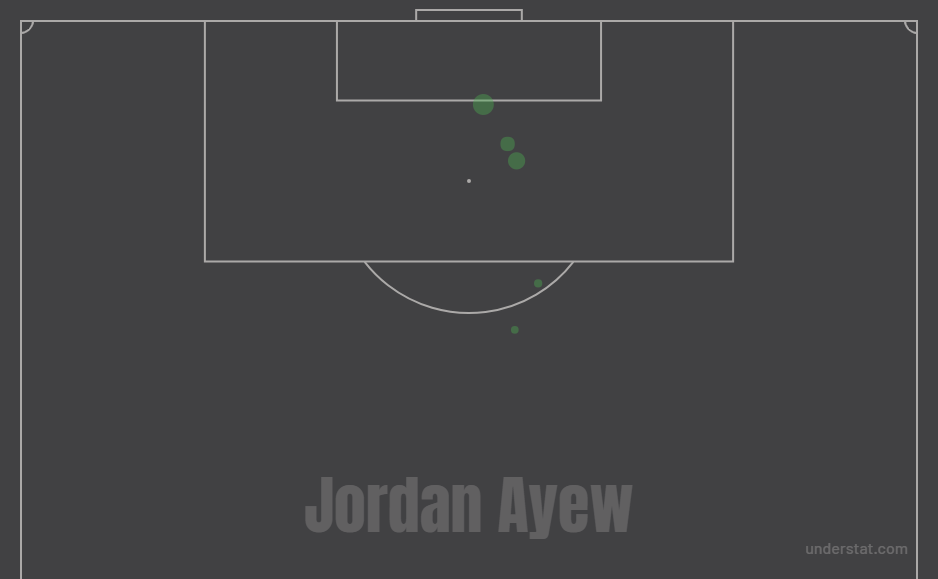

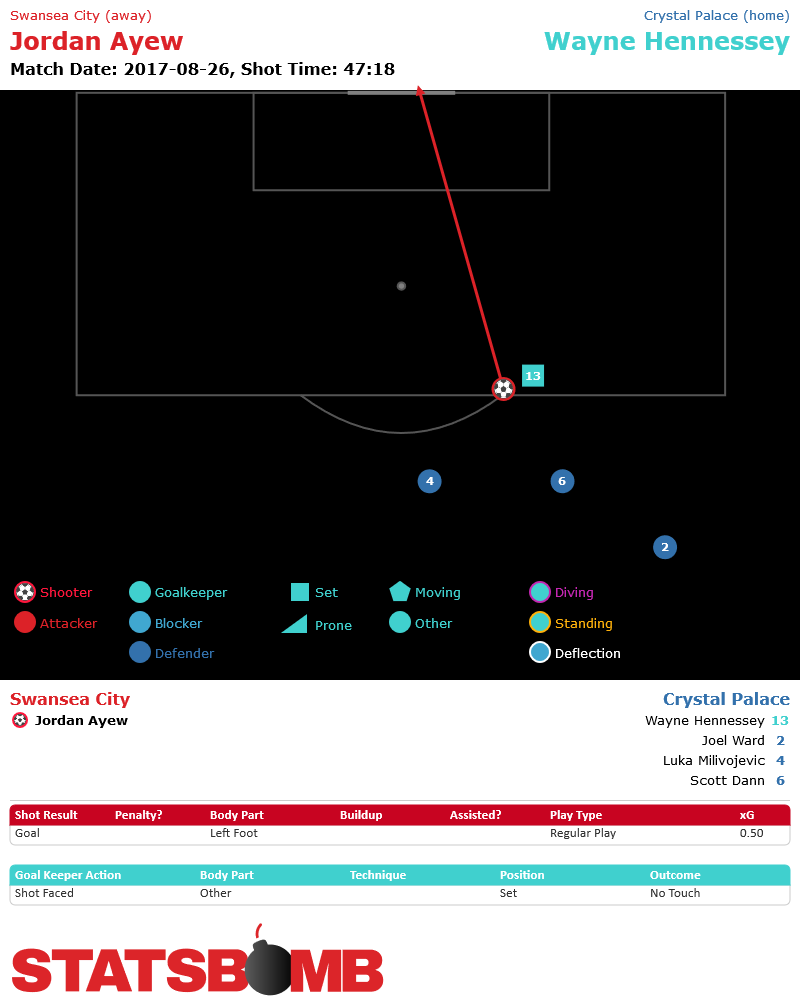

This one is from Swansea and Jordan Ayew. He scored from just outside the box away against Crystal Palace in late August. Here’s a typical xG evaluation. This particular goal is the little green dot at the top of the box. Seems like a pretty unlikely shot from distance. This xG model gives the shot a 0.06.

Now here’s the SBxG.

And here’s the video.

Seems like keeper location was pretty important for evaluating this shot.

SBxG and Cautious Optimism

Those two examples are unfair.

They’re extreme outliers, situations in which missing information, either on the keeper or on defender location are particularly damaging to a typical xG model’s ability to correctly measure a shot. In the grand scheme of things those shots are the exception, not the norm. Also, in the grand scheme of things those exceptions don’t particularly hurt xG’s ability to do the job for which it was designed. But, outliers are valuable to coaches.

They’re valuable to analysts, and they’re valuable to fans. And they're valuable to understanding small sample sizes like a single game. It’s pretty clear watching the tape that xG gets that Iheanacho shot wrong. It obviously misses the Ayew one. StatsBomb data picks up on that. Old data showed Bournemouth’s defense breaking down, and somehow avoiding conceding. Our data shows a Bournemouth defense standing strong in a difficult situation. Old data shows Ayew getting lucky from distance, scoring a low percentage shot that coaches would be happy to give up. Our data shows a dreadful defensive mistake.

This data is all new, so we’ve got a long way to go before we can actually make definitive claims about, well about anything really. But, the design is for StatsBomb data to be granular enough to describe chances as accurately as the vague moniker “big chance” while also giving a wealth of descriptive information about shots. It's impossible to say for certain what the future of using this data looks like. We simply don’t know how often examples like the ones above occur, or if they occur in measurably consistent ways. It’s possible that at the end of the day all this data doesn’t actually improve overall predictability much, but it improves precision a lot.

It’s possible it only improves precision a little, and in obvious situations like the ones above.

That is, rather than revealing something new, this data only confirms what close watchers of the game can see. That has value. It certainly has value for coaches looking to evaluate performances, or fans looking to understand what happened.

It’s also possible that as this data becomes more robust, and we have more games and seasons and leagues under our belts, patterns will start to emerge. Perhaps certain teams or players will stand out as doing something that fooled earlier xG models. Maybe the model will pick up on errors in defensive positioning more reliably, or be better able to quantify teams that pack the box. It’s impossible to know until the work gets done. The exciting thing is that now that all this new data is here, there’s finally something to do that work on. It’s too early to know exactly what goodies this data has in store for more robust xG models. But, it’s definitely time to get excited about finding out.

The Dual Life of Expected Goals (Part 1)

“Let me explain... No, there is too much. Let me sum up” --Inigo Montoya

The great thing about running a football stats website is that you get to do things like devote thousands of words entirely to a single statistic, and there’s nobody to tell you not to. So, let’s get into expected goals, what it is, where it came from, and most importantly where it’s going from here. Lots of football fans have only experienced the good ol’ xG as a single game number, either included on the bottom of a TV scroll, next to shots, fouls and assorted other stats, or on twitter as a pretty little shot map. That wasn’t what it was designed for though. Single game xG is a useful tool (and one we here at International StatsBomb Headquarters are committed to making more useful) but it was originally developed for something entirely different.

Goals: The Only Stat that Matters

In the beginning there were goals. Just goals. That was the only thing that was counted. Whoever had the most goals won the most games. You play to win the games. Therefore, the only thing that mattered was counting goals. There were some exceptions of course. Charles Reep notably counted passes by hand well before the rest of the world decided to do the same. But, for the most part, people watched football and counted goals, and the years went by. Eventually, somebody decided to count the passes leading to goals as well. And voila, there were assists.

At that moment, at the dawn of statistical time, a schism was born. On a team level, the statistic of goals gives you more information, than if you didn’t have it. Not only is it the way in which we keep score, but also the knowledge of a team’s goal difference helps observers determine how good they are with more accuracy than if they knew whether they had won or lost. On the other hand, knowing about a team’s assists doesn’t give an outside any more information about how good the team is. There’s a reason that goal differential is a thing and assist differential isn’t.

Statistics, at their heart, serve two purposes. The first is predictive. What do knowing these numbers tell us about the future? Knowing how many goals a team scored and conceded makes people better able to predict how likely a team is to win future games. The second is descriptive. What do these numbers tell observers about how things happened? Assists are a descriptive statistics, and a useful one, but they aren't especially predictive. If assists were zapped out of existence overnight there'd be very little impact on the world's ability to predict the outcome of football matches.

That’s a tension that has always existed, and it’s one that remains at the heart of how the football world is increasingly using xG.

Shoot Your Shots

Before getting to modern statistical times, there’s one more stop to make. One of the first things that statisticians began regularly counting was the number of shots teams were taking. It’s an obvious statistic to look at, and it turns out that it’s pretty important. You cannot score (for the most part) if you do not shoot. This is not rocket science. It’s not even bottle rocket science.

As Ted and James talked about on the last StatsBomb podcast the groundwork for looking at shots in football was laid in hockey. In hockey shots served both a clear descriptive purpose and provided predictive utility. Shots in hockey are a pretty good way of describing who has possession. Descriptively, by saying teams have a lot of shots, you can also say that teams have a lot of the puck. Predictively they also have a lot of value. In hockey the best teams reliably take a lot more shots than their opponents, but it’s very hard to control how often the shots a team takes are scored. By measuring how many more shots a hockey team takes than their opponents, it gets easier to predict which hockey teams will do well in the future.

Those findings were applicable to football, but only in a limited way. The first major problem is that descriptively comparing shots is not a particularly good way to measure possession. The relationship between possession and shooting is a lot looser in football than hockey (this will surprise nobody who has watched either sport for more than ten minutes. It’s mostly down to one sport being played with feet on grass and the other one being played with sticks on ice. Small things like that.). Using shots as a proxy for possession doesn’t really work. Broadly speaking football uses passes played to measure possession, which is better, but not perfect.

Despite that, measuring shots is still pretty good as a predictive tool. Knowing how many shots a team has taken and conceded makes you even more able to predict how they’ll do in the future than if you only knew about their goals scored and conceded. That’s great. It’s also frustrating. The gap between shots’ predictive power and descriptive power makes it impossible to turn the information we get from shot differentials into anything resembling insight.

The information those stats contains does a pretty good job of explaining what will probably happen next, and a terrible job of explaining why. If a team is scoring a particularly high percentage of their shots, or on a particularly cold run, looking at shot numbers doesn’t offer any answers as to why it’s happening. All that they have to offer is an assurance that it probably won’t continue.

One thing that’s important to note here is that just because these stats can’t provide a reason for the divergence between shooting and scoring doesn’t mean there isn’t one (or many), it just means that those reasons are incidental to predicting what comes next. That’s an answer that’s useful to only a very small group of people (mostly the ones looking to put a bet down). It doesn’t help people interested in understanding what’s going on, people like, say, coaches who have to make the hundreds of daily decisions which go into running a team.

And now, finally, we get to the good stuff.

What to Expect When You’re Expecting Goals

Using past shots to predict how will teams will do in the future is good. Further modifying that to factor in what type of shots teams are taking is even better. That’s, in effect, what xG does. Notably what xG was not developed to do is accurately describe a single shot or a single game. Rather, it was designed to take lots of information, thousands and thousands of shots, synthesize it, and use that information to represent how many goals a team might reasonably be expected to score or concede given the types of shots they’ve taken and given up.

This is good and useful information. There are ample studies showing how this process is better at predicting how a team will do in the future than pretty much anything else out there. It takes the old information, based purely on the volume of shots and improves it. It turns out that sometimes when a team is shooting better or worse than average it’s because on average they’re taking better or worse shots.

There are two problems with xG as currently constituted. The first is that just like with a basic shot based metric teams frequently spend stretches of time doing better or worse than where the metric thinks they’ll end up. And, just like with shots, xG doesn’t offer many answers other than the (quite good) prediction that eventually that will stop. It explains part of what shots miss, but there’s still plenty of room left blank.

The problem of what xG might be missing in the short term is encapsulated by how it’s used for single games. It’s important to start off by saying, that xG maps contain more information than pretty much any other form of quick glance game recap. But it’s not what it was designed for. The total goals a team score will often differ wildly from what xG predicts. Frequently this is by design. If a player misses a sitter, xG and actual goals should differ. That’s the point. The model is crediting the team for creating the chance, understanding that in the future creating those chances will lead to goals.

So, there’s a way in which single game xG totals differing from the result is a direct sign that the model is working. But, there’s another reason they can differ as well. The value that an xG model assigns to any given specific shot is based on an average of past similar shots. So, it takes into account things like location, whether or not it’s a header, the kind of pass that led to the shot, etc etc, mixes them all together and spits out a value.

The problem with averages is that they’re averages. Any single chance can differ significantly from that average. Because we know that xG works, and is quite predictive, we know that over the long run the ways those individual shots differentiate from average more or less cancel each other out. But, during a single game, that definitely doesn’t happen. A team with a high xG total but no goals might have missed a bunch of good chances, or the chances they had might have been harder than the model predicts. Single game xG totals don't differentiate between the two.

Luckily StatsBomb can help with that problem. To find out how, stay tuned for part two.

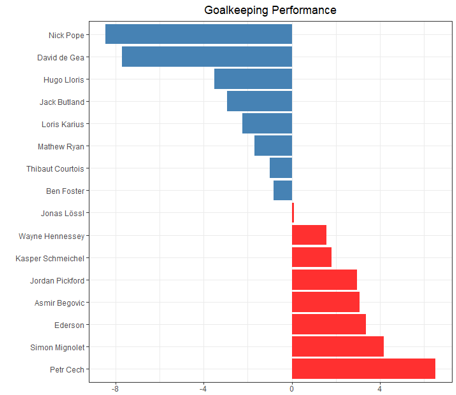

StatsBomb Data Launch - Finding Better Goalkeepers

Embedded below is the second of our presentations from the StatsBomb Data Launch event. The presentation is given by data scientist Derrick Yam and is called Beyond Save Percentage, to pair with my presentation called Beyond xG. However, Derrick's ambition here is actually much greater. He asks:

- Can we use the new information in StatsBomb Data to help find the best GK in the world?

- At the same time, can we start to find up and coming GK to keep an eye on?

- Can we help quantify GK value through data?

- and Can we build a better framework for data analysis of GK to help do all of this?

Check it out...

Is Nabil Fekir Good Enough for Liverpool?

Nabil Fekir. You've probably heard of him.

Over the last two or three summers transfer rumors swirled around Fekir at Olympique Lyonnais. Recent reports suggest that this year might actually be the year they come to fruition. Not only will the club not stand in the way of a potential transfer, but that move could involve Liverpool splashing somewhere in the region of €70 million. Initially, it seems a bit odd that Liverpool would shell out that amount of money on an attacker, especially when other holes exist in the squad. It’s not that Liverpool don't need depth behind their fabulous front three, but it's possible that spending that much money on that position isn’t the smartest idea.

Conversely, if Fekir is a legitimate star talent, then a team should do almost everything it can to acquire him. He has about as a high a level of coordination on the ball as you'll find in an attacking midfielder, whether with his ball striking, or how he handles himself in tight spaces. He might be one of the few players out there who can beat out post-shot expected goal models on a consistent basis. There’s a lot to like about Fekir, but there are also risks involved. Not just his injury history, but also how adaptable his style of play would be for a club like Liverpool, and whether he will continue to convert at a higher rate than what his shot quality on average would dictate.

Fekir's clearly good, the question is how good of a fit would he be for Liverpool?