There are multiple ways that one could analyze the failings of Manchester United over the past six to seven years. Whether it's the rotating cast of managers or the lack of direction in player recruitment, Manchester United have operated at a level that’s nowhere close to optimal efficiency given the incredible resources at their disposal.

One area that shows a lack of forethought in their planning is the number of individuals who have played minutes as a right-back during this down period for the club. That list includes Rafael, Antonio Valencia, Matteo Darmian, and Ashley Young. The lack of a very good-great RB whose could hold his own at the highest level has been one of several reasons why Manchester United have been stuck in the wilderness for the greater part of the past decade.

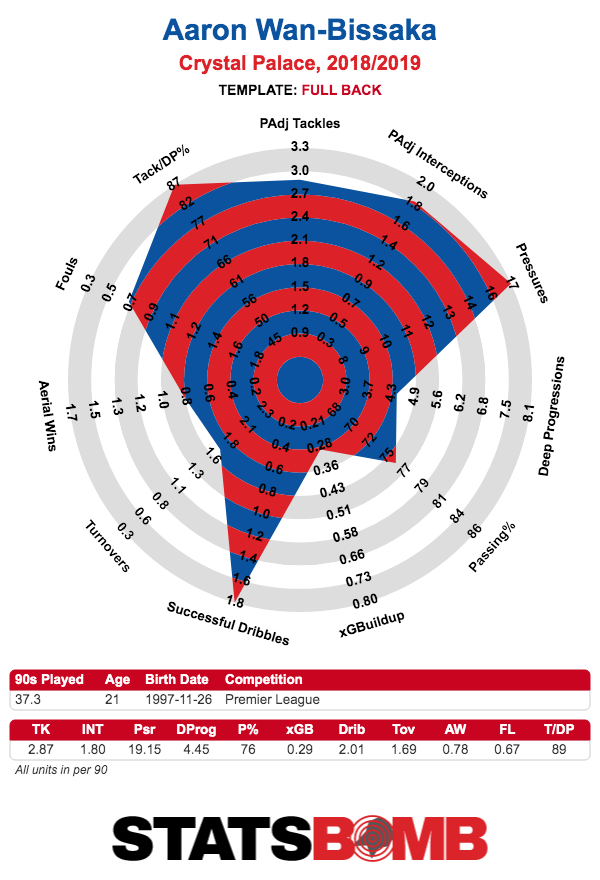

There’s little doubt that Aaron Wan-Bissaka had a great individual season and ranked as one of the best fullbacks in the Premier League. It’s very likely that he was the best defender from the fullback position, and was a major reason why Crystal Palace once again held their head comfortably above the relegation waters. Many of the plaudits he’s been given for his performances last season are deserved, and it’s mightily impressive that he did that at his age.

So it’s been no surprise to see him being heavily linked with Manchester United given their long standing hole at RB. On the face of it, it’s not hard to put two and two together to make four: Wan-Bissaka is good, United have needed a long-term right back for ages, and he’s English. Sure, the reported transfer fee that could land as high as £50 million is a large figure, but United would rationalize it by this move being one that represents both present and future value.

Well it’s not quite as straightforward as that. While Wan-Bissaka is undoubtedly a talented defender with a bright future, it’s fair to wonder whether it’s smart of United to spend so much money for his services given the questions that surround him on the attacking end. Manchester United’s end goal as a club is to get back to being a very good, maybe evengreat team, and envisioning the next good United side would involve concocting a squad that will be able to dictate play in possession with regularity. Doing so would involve have minimal weak links during ball progression. This is especially true with fullbacks given that they have a major part to play in creating chances as auxiliary wingers.

That’s the issue that surrounds Wan-Bissaka. Very few are questioning whether his defensive capabilities will translate at a bigger club, because he’s shown enough this season to suggest that’s a rather safe bet.

Rather, will he be able to exist as a functional cog in the wheel offensively?

Furthermore, just how good is Wan-Bissaka currently offensively?

Is there enough upside that he could grow into a net positive as a play-driver?

These are some of the questions to ask when evaluating Wan-Bissaka as a talent, and whether it’s a smart idea for United to allocate major resources (not just the transfer fee but wages as well) towards him. Certainly, that mystery on Wan-Bissaka's offensive ceiling is in part due to playing on a decent but unspectacular attacking side in Crystal Palace last season. They ranked 12th in expected goals from open play and 8th in shots. If he had played on a more expansive attack, perhaps we would've had more of an idea on his upside as a play-driver.

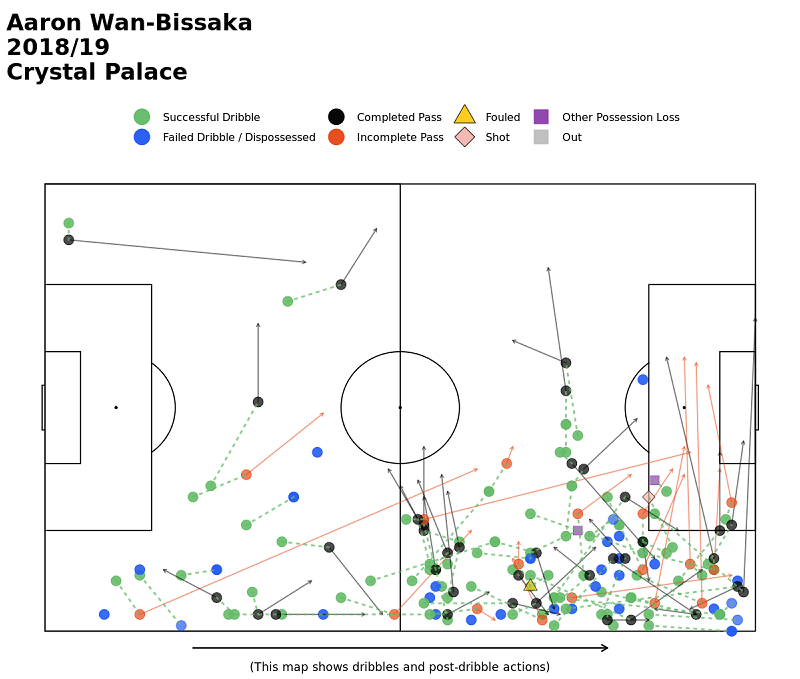

If one was to concoct an argument in favor of Wan-Bissaka's offensive ceiling, a major component would be his dribbling abilities and the luxuries it affords him that not a lot of fullbacks possess. As part of the responsibilities that modern day fullbacks have, being able to beat their marker off the dribble in the middle and final third has become much more of a necessity. Wan-Bissaka certainly has that in his skill-set, his 2.01 dribbles per 90 is nearly three times the league average rate for fullbacks in the Premier League, and his dribbling map below shows a very healthy amount of dribbles into more advanced areas along with the actions that followed.

The ease with which Wan-Bissaka can get himself out of tight situations on the flanks is quite remarkable. He could use his dribbling as an escape valve to merely continue recycling possession to a nearby teammate, or cover ground once he gains separation from his marker and progress play. As the ball is slowly moving towards his vicinity, he's great at being able to quickly shift the ball from one foot and making his marker miss. He's also able to use misdirection through body feints and quick changes of direction when he's luring his opponent into a false sense of security before hitting the afterburners. He's also quite good at general ball carrying duties.

When Wan-Bissaka is able to leverage his dribbling into more impact plays post-dribble he's at his best and displays the kind of offensive upside you would want from a high priced fullback. Though, admittedly, he's still at the beginning stages of combining high level dribbling with passing so he shows brief flashes rather than anything sustained. In terms of his passing in isolation, it would be a stretch to call him a dynamic passer or perhaps even a good one.

Rather, he's shown more to have a baseline of functionality in the passes he can make. The most complex pass he has in his repertoire are little reverse/lead passes into the right wing area near the box so teammates can then launch balls into the box, which is nice but not necessarily the most value-added type of pass to have in your arsenal given that the end result are crosses.

While I believe that there's a functional level to his passing, there are moments where Wan-Bissaka shows discomfort on-ball when trying to make decisions, especially when attempting to make dangerous passes as he doesn't quite have the touch to connect on them. There are also times when he opts for conservatism over something grander. He can look indecisive and give opponents an opportunity to seize on him telegraphing his passes and create turnovers in play. His abilities as a crosser and chance creator to this point are nothing much to write home about, though how much of it is due to system constraints and surrounding talent is up for debate. Wan-Bissaka's passing to this point is somewhere between average to below-average.

There's one play in particular that I go back to when evaluating Wan-Bissaka's ability to drive play and some of the surrounding skepticism. As Wan-Bissaka is carrying the ball towards the final third, Cheikhou Kouyate is making a looping run to his right and there's the slight opening to make a pass into the right wide area of the box. Instead, Wan-Bissaka shifts the ball to the wings, which eventually leads to a corner and represents a missed opportunity at something greater. Now, the slip pass into the right side of the box is not an easy play to pull off and there's no guarantee that a successful pass would lead to something grand, but paying £45-50 million for a fullback would come with the expectations that these opportunities to help create scoring chances would not be left on the table.

Manchester United potentially spending up to £50 million on Wan-Bissaka represents a bet on him eventually becoming one of the better fullbacks in the world two to three years from now. For that to occur, his offensive value will have to get to a high enough level through ironing out some of the kinks. Given how good he projects to be defensively over the next few years, it might be that he merely needs to be a slight net-positive offensively rather than an no-doubt stud in attack.

It's not impossible to imagine that being the case for Wan-Bissaka: his dribbling abilities are outstanding and that alone brings value. His passing isn't a lost cause, though it's not a strength yet. The hope is that his dribbling abilities continue to translate and create passing opportunities for him that it wouldn't exist for others, and with more reps in advanced areas as well as playing with talented teammates at United, he becomes a better offensive player.

That version of Wan-Bissaka would be more than worth the high price tag that United will reportedly paid for his services. The more pessimistic angle would be that Wan-Bissaka's passing never appreciably develops from its current state, and as a result, his game doesn't quite scale up to the highest level of competition and makes him less of an asset.

One question that could be asked regarding this move is whether United would've been better off going with another option. Perhaps that would've been trusting Diego Dalot with a starting position with Ashley Young and Matteo Darmian providing backup. Maybe United could've gone for a considerably cheaper option in the market instead of Wan-Bissaka and split duties between that player and Dalot.

Those are fair critiques when accounting for the holes that exist in United's midfield, especially if Paul Pogba departs this summer. Getting Aaron Wan-Bissaka at his reported price is a gamble on some level and doesn't necessarily represent the cleanest approach to squad building, but one that could still pay major dividends if he grows into an all around force once he approaches his prime.

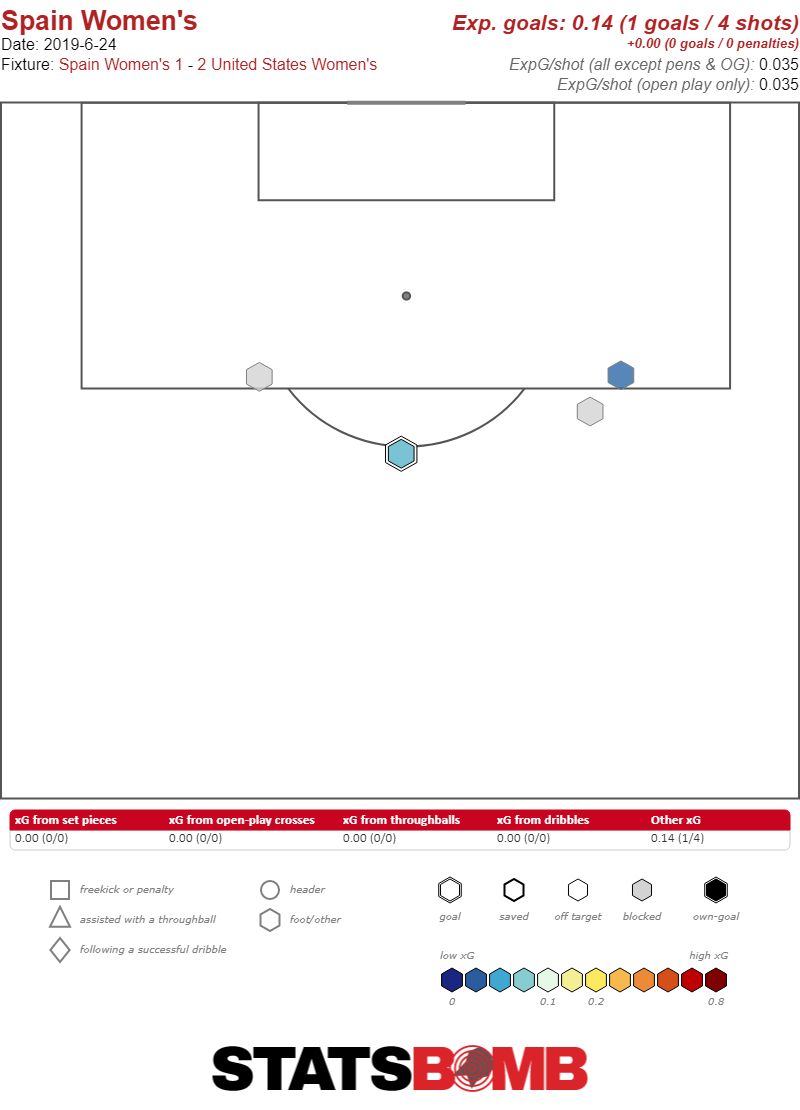

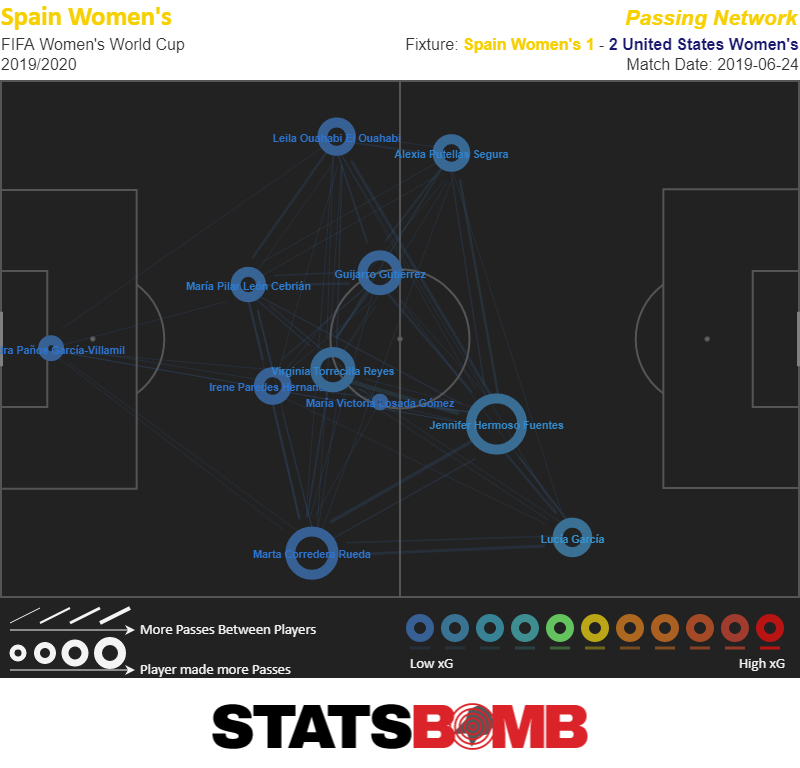

What Spain did do is cross the ball a lot. They targeted Crystal Dunn on the left side of the American defense, and worked the ball down the flank to Lucía García, who then was asked to supply service into the box. But that service never amounted to anything.

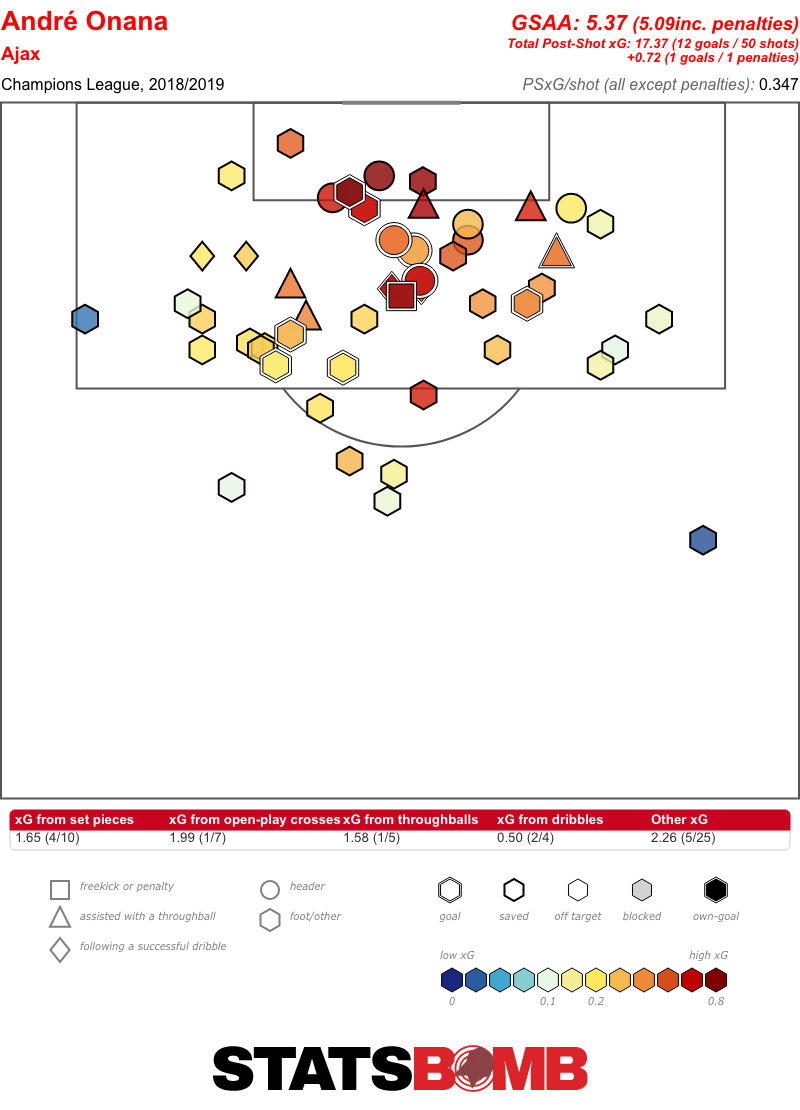

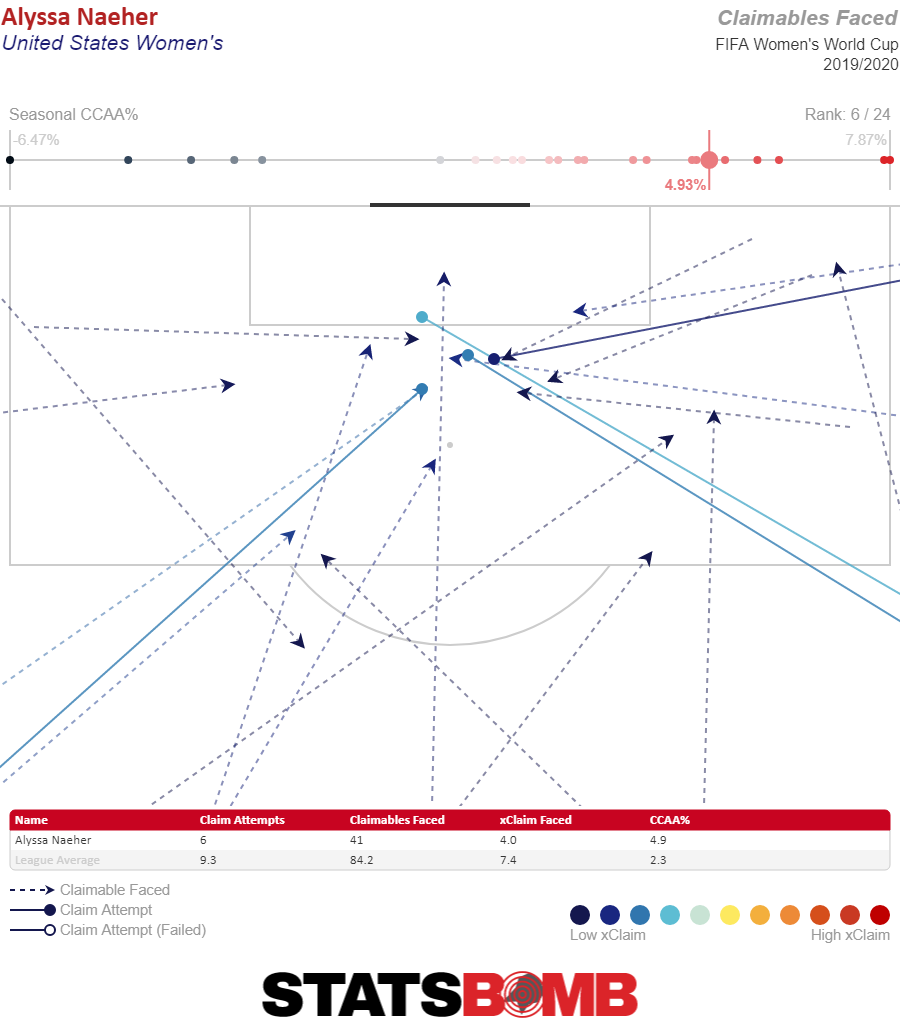

What Spain did do is cross the ball a lot. They targeted Crystal Dunn on the left side of the American defense, and worked the ball down the flank to Lucía García, who then was asked to supply service into the box. But that service never amounted to anything.  Although Dunne was unable to prevent service from coming in, the rest of the defensive line was consistently well positioned to deal with the never ending stream of crosses, and despite her reputation for shakiness, Naeher put in a strong, aggressive performance commanding her box. She claimed six of the 41 balls that were theoretically within her range, when on average a keeper might have been expected to claim only four.

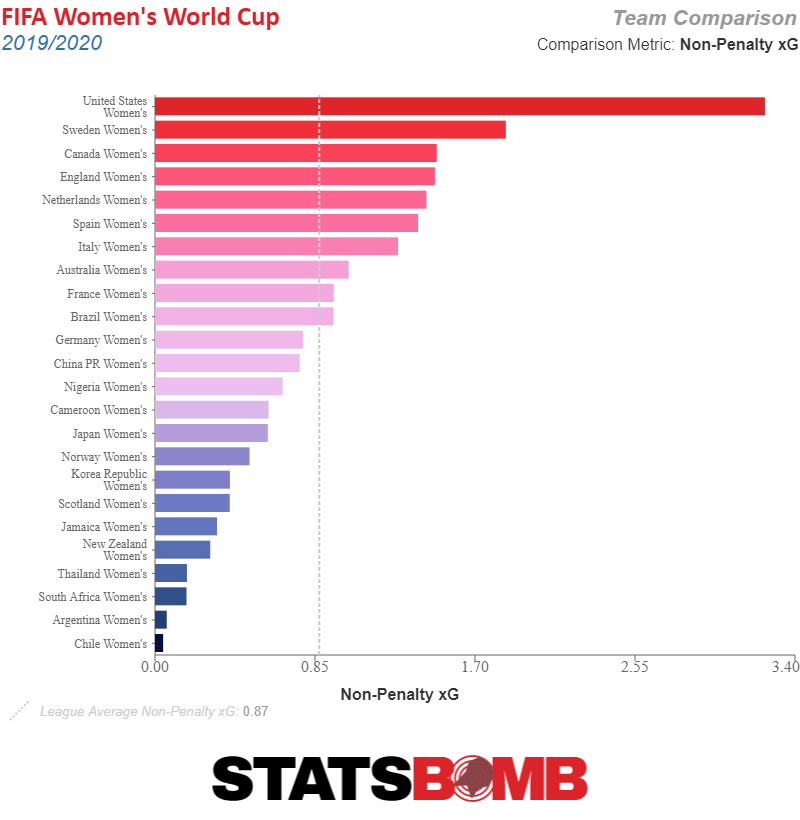

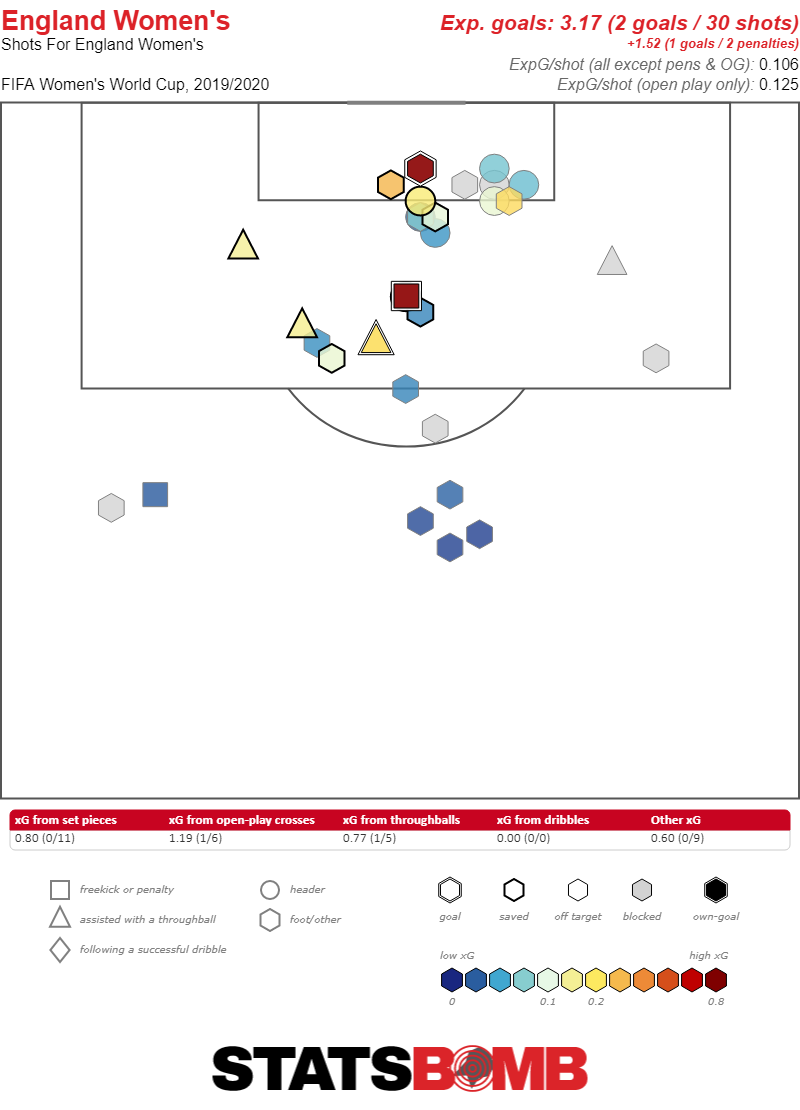

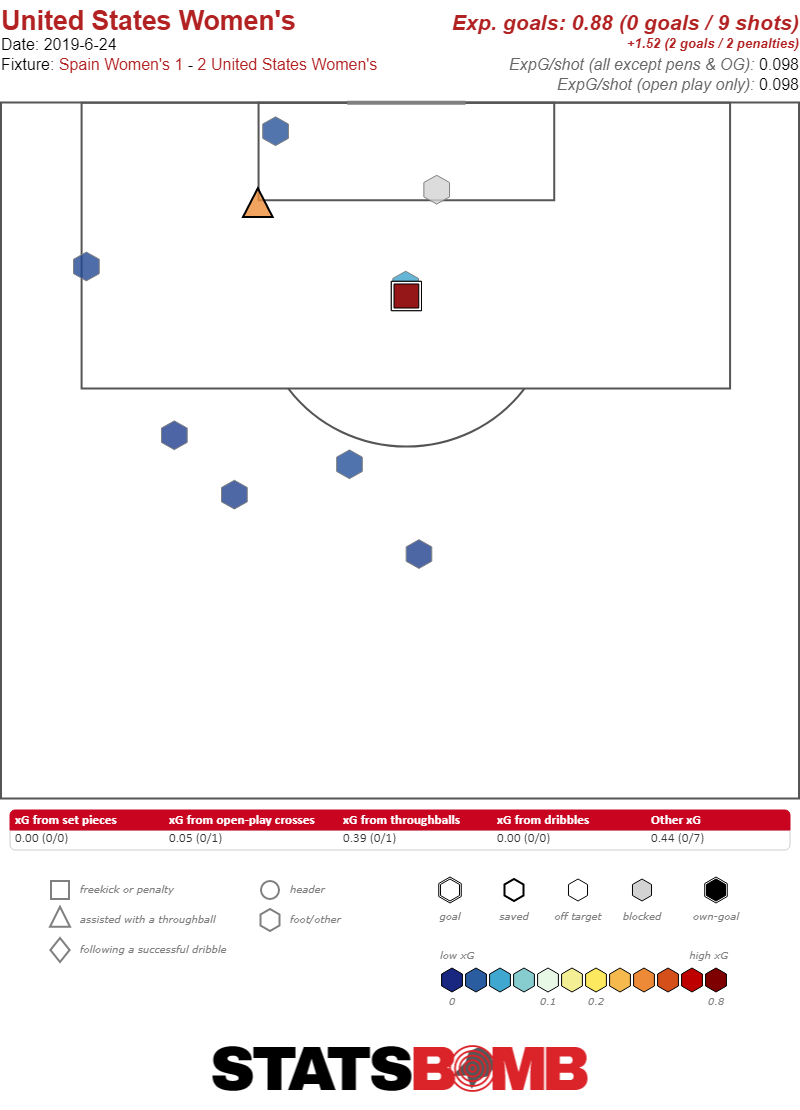

Although Dunne was unable to prevent service from coming in, the rest of the defensive line was consistently well positioned to deal with the never ending stream of crosses, and despite her reputation for shakiness, Naeher put in a strong, aggressive performance commanding her box. She claimed six of the 41 balls that were theoretically within her range, when on average a keeper might have been expected to claim only four.  Spain didn’t ask difficult questions of the American defense, and the easy ones, which they asked quite frequently, were answered with ease. The problem is that the vaunted American attack didn’t live up to their reputation. Outside of the two penalties they were awarded, the favorites took nine shots which amounted to only 0.88 expected goals

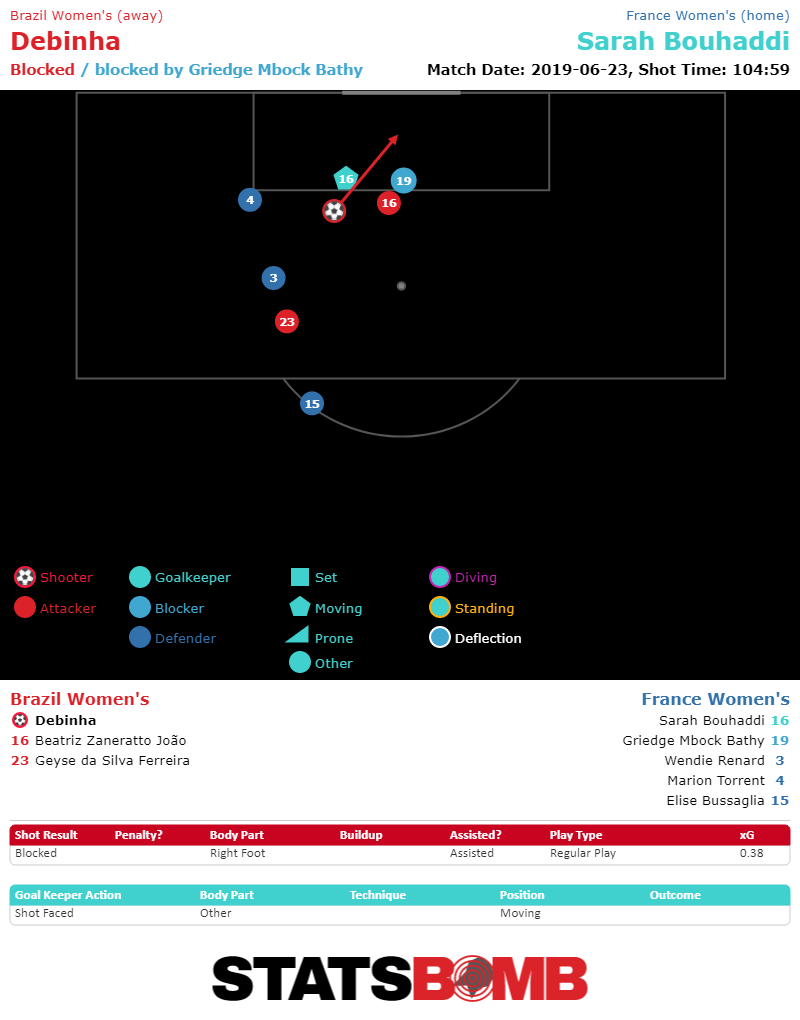

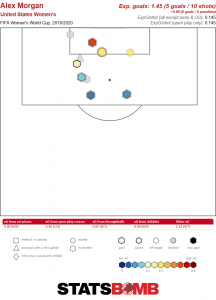

Spain didn’t ask difficult questions of the American defense, and the easy ones, which they asked quite frequently, were answered with ease. The problem is that the vaunted American attack didn’t live up to their reputation. Outside of the two penalties they were awarded, the favorites took nine shots which amounted to only 0.88 expected goals  This might be excusable if the side was protecting a lead for most of the match, but they were not. There were two minutes between when the team scored the opening penalty, and Spain’s equalizer, and then it wasn’t until the 75th minute when the second penalty was awarded. And after the 16th minute the U.S. didn’t have a single shot from open play valued at over 0.05 xG. There are reasons for that. Lindsey Horan, who might be the best all-around midfielder in the world, was held in reserve, possibly because she was carrying a yellow card. Alex Morgan, the team’s iconic center forward had a poor game, spent a lot of time picking herself up off the ground after being kicked, and is possibly carrying an injury (she was subbed off at halftime of the team’s third group stage game against Sweden). Sometimes a team just doesn’t play well. Still, the main takeaway from Spain’s surprisingly game performance is not that the U.S. is vulnerable defensively, although it’s possible to see how a better team might have turned their copious crossing opportunities into more dangerous goal scoring chances, but rather that sometimes that vaunted attack can, in fact, be slowed down. The opposite is true of France. France’s attack has been somewhat underwhelming all tournament. The side has largely relied on the impeccable set piece skills of Wendie Renaud, and doing just enough to put opponents away before playing incredibly stingy defense. That’s what made the fact that they conceded 12 shots to Brazil so surprising (even accounting for extra time). This was a side that gave up 12 shots total in the group stage. And it’s not like the group stage was a walkover. They held Norway, a fellow quarterfinalist to just five shots, and Nigeria who took eight shots against Germany in the their knockout round loss, to just two. The moment of the match, of course, came in extra time when Debinha shook free on France’s left, cut inside the penalty area, scooped her shot comfortably around on-rushing keeper Sarah Bouhaddi only to see backtracking defender Griedge Mbock Bathy make the defensive play of the tournament and block the shot before it nestled in the far side of goal.

This might be excusable if the side was protecting a lead for most of the match, but they were not. There were two minutes between when the team scored the opening penalty, and Spain’s equalizer, and then it wasn’t until the 75th minute when the second penalty was awarded. And after the 16th minute the U.S. didn’t have a single shot from open play valued at over 0.05 xG. There are reasons for that. Lindsey Horan, who might be the best all-around midfielder in the world, was held in reserve, possibly because she was carrying a yellow card. Alex Morgan, the team’s iconic center forward had a poor game, spent a lot of time picking herself up off the ground after being kicked, and is possibly carrying an injury (she was subbed off at halftime of the team’s third group stage game against Sweden). Sometimes a team just doesn’t play well. Still, the main takeaway from Spain’s surprisingly game performance is not that the U.S. is vulnerable defensively, although it’s possible to see how a better team might have turned their copious crossing opportunities into more dangerous goal scoring chances, but rather that sometimes that vaunted attack can, in fact, be slowed down. The opposite is true of France. France’s attack has been somewhat underwhelming all tournament. The side has largely relied on the impeccable set piece skills of Wendie Renaud, and doing just enough to put opponents away before playing incredibly stingy defense. That’s what made the fact that they conceded 12 shots to Brazil so surprising (even accounting for extra time). This was a side that gave up 12 shots total in the group stage. And it’s not like the group stage was a walkover. They held Norway, a fellow quarterfinalist to just five shots, and Nigeria who took eight shots against Germany in the their knockout round loss, to just two. The moment of the match, of course, came in extra time when Debinha shook free on France’s left, cut inside the penalty area, scooped her shot comfortably around on-rushing keeper Sarah Bouhaddi only to see backtracking defender Griedge Mbock Bathy make the defensive play of the tournament and block the shot before it nestled in the far side of goal.  The irony of that moment is that it’s one of only two shots that Brazil managed after the regulation 90 minutes were finished. Cristiane took an early long-range audacious effort before being forced off through injury, but other than the spectacular Debinha attempt, that was it for Brazil. France meanwhile poured on the pressure, taking eight shots (after only taking six in the first 90 minutes) including Amandine Henry’s winning header. France have an immensely talented squad but they have largely chosen to deploy that squad to win games with as little defensive risk as possible. Against Brazil that meant a conservative 90 minutes. But when regulation finished, the approach changed. They ramped up the pressure, poured on the shots, and also gave away an extremely dangerous counterattack, which, if not for a defensive miracle could have seen them shockingly sent home. On balance, they were the better team, but the France approach is supposed to insulate them from conceding exactly the kind of high value shot that Brazil put on them in extra time. There’s no doubt that France and the U.S. are the two best teams in this World Cup. They came in as favorites, and they remain so. But, if the tournament has taught us anything, it’s not that the two teams expected weaknesses can be exploited, rather it’s that both Spain and Brazil were able, for stretches of time, to make the parts of the favorites’ game that were supposed to be their strengths, appear relatively ordinary. After watching them struggle to break down Spain, France will feel better about their chances to hold the U.S. And after watching Debinha come within inches of knocking France out, the U.S. will see a defense that might be there for the taking. On Friday we’ll see if that changes either side’s plan of attack. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

The irony of that moment is that it’s one of only two shots that Brazil managed after the regulation 90 minutes were finished. Cristiane took an early long-range audacious effort before being forced off through injury, but other than the spectacular Debinha attempt, that was it for Brazil. France meanwhile poured on the pressure, taking eight shots (after only taking six in the first 90 minutes) including Amandine Henry’s winning header. France have an immensely talented squad but they have largely chosen to deploy that squad to win games with as little defensive risk as possible. Against Brazil that meant a conservative 90 minutes. But when regulation finished, the approach changed. They ramped up the pressure, poured on the shots, and also gave away an extremely dangerous counterattack, which, if not for a defensive miracle could have seen them shockingly sent home. On balance, they were the better team, but the France approach is supposed to insulate them from conceding exactly the kind of high value shot that Brazil put on them in extra time. There’s no doubt that France and the U.S. are the two best teams in this World Cup. They came in as favorites, and they remain so. But, if the tournament has taught us anything, it’s not that the two teams expected weaknesses can be exploited, rather it’s that both Spain and Brazil were able, for stretches of time, to make the parts of the favorites’ game that were supposed to be their strengths, appear relatively ordinary. After watching them struggle to break down Spain, France will feel better about their chances to hold the U.S. And after watching Debinha come within inches of knocking France out, the U.S. will see a defense that might be there for the taking. On Friday we’ll see if that changes either side’s plan of attack. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

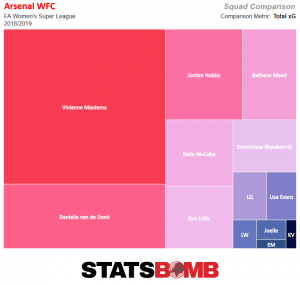

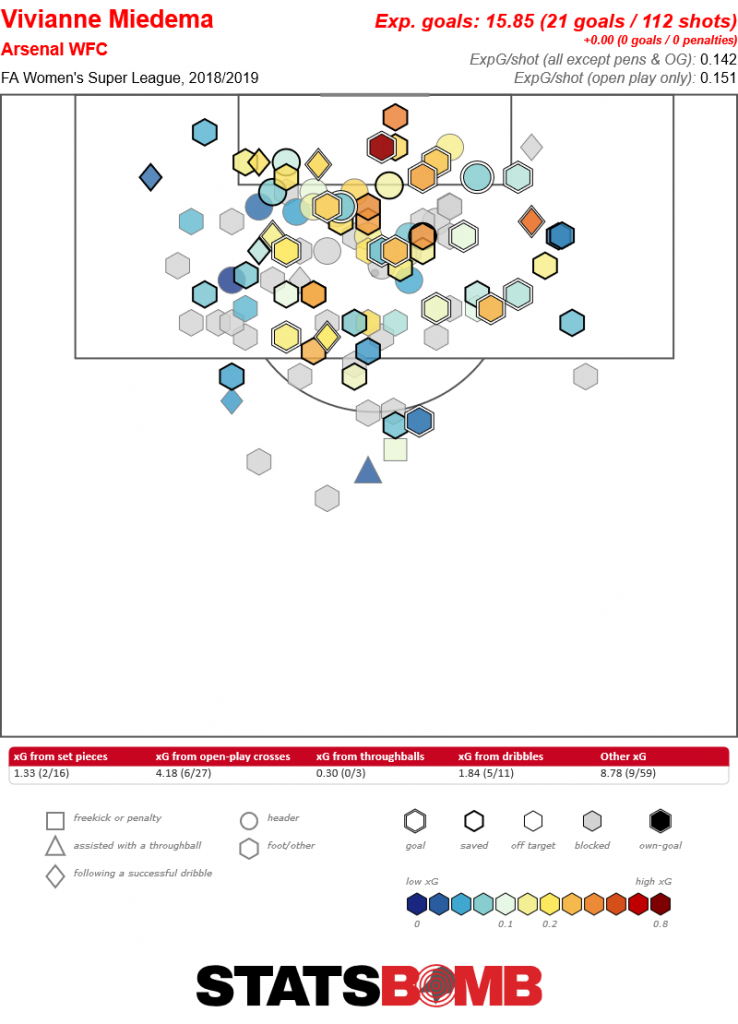

She is fast, strong, capable of creating space for herself or teammates just as well as she can be in the right place when needed. The scariest fact, however, is that this Olympic gold medallist and FIFA Women’s World Cup champion is not the only seasoned professional and winner up USA’s sleeve and the defending champions seem to be just warming up for when the really big games hit. Vivianne Miedema (Age 22, Netherlands) Anna Margaretha Marina Astrid “Vivianne” Miedema has made a name for herself in the world of football at the age of only 22. She was 17 when she played at Bayern Munich in a team that remained unbeaten in the Bundesliga and won their first title since 1976. After an injury-ridden first season with Arsenal, she scored a record 22 league goals to help Arsenal to their first league title in seven years. Miedema was a huge part of Arsenal's attack in 2018/19.

She is fast, strong, capable of creating space for herself or teammates just as well as she can be in the right place when needed. The scariest fact, however, is that this Olympic gold medallist and FIFA Women’s World Cup champion is not the only seasoned professional and winner up USA’s sleeve and the defending champions seem to be just warming up for when the really big games hit. Vivianne Miedema (Age 22, Netherlands) Anna Margaretha Marina Astrid “Vivianne” Miedema has made a name for herself in the world of football at the age of only 22. She was 17 when she played at Bayern Munich in a team that remained unbeaten in the Bundesliga and won their first title since 1976. After an injury-ridden first season with Arsenal, she scored a record 22 league goals to help Arsenal to their first league title in seven years. Miedema was a huge part of Arsenal's attack in 2018/19.  As a crucial part of the 2017 European Championship winners’ side, she scored the winning goal in the semi-final versus England as well as two goals in the final versus Denmark. Miedema made every “top players to watch out for” list prior to France 2019, but this one seems as ice-cool under pressure as compatriot Dennis Bergkamp even though her idol is the more impulsive Robin van Persie. After the Oranje struggled against a well-organised New Zealand, scraping through only thanks to a Jill Roord stoppage-time header, the game versus Cameroon meant a chance to make amends. Miedema headed a brilliant goal at the 41st minute only for Gabrielle Aboudi

As a crucial part of the 2017 European Championship winners’ side, she scored the winning goal in the semi-final versus England as well as two goals in the final versus Denmark. Miedema made every “top players to watch out for” list prior to France 2019, but this one seems as ice-cool under pressure as compatriot Dennis Bergkamp even though her idol is the more impulsive Robin van Persie. After the Oranje struggled against a well-organised New Zealand, scraping through only thanks to a Jill Roord stoppage-time header, the game versus Cameroon meant a chance to make amends. Miedema headed a brilliant goal at the 41st minute only for Gabrielle Aboudi  Christiane Endler (Age 27, Chile) Paris Saint-Germain goalkeeper Christiane Endler deserves to be on this list despite her team failing to qualify for the knockout stages. Considering that FIFA unranked the Chilean women’s national team back in 2016 for their own federation’s lack of desire to schedule games for them, the players have been fighting an uphill and many times losing battle. Yet, they should (and hopefully will) take heart from their co-captain’s Player of the Match performance against the champions, despite Chile losing 3-0 and being out possessed 32% to 68%. Endler, born to a German father and a Chilean mother, psyched-out Carli Lloyd enough for the veteran to miss a rare penalty, made six saves from their nine shots on target, and single-handedly restricted team USA, and particularly Christen Press. It was a performance special enough for USWNT legend Hope Solo to dub Endler “

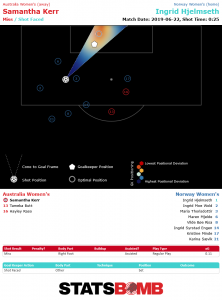

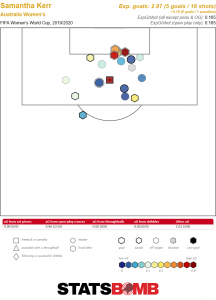

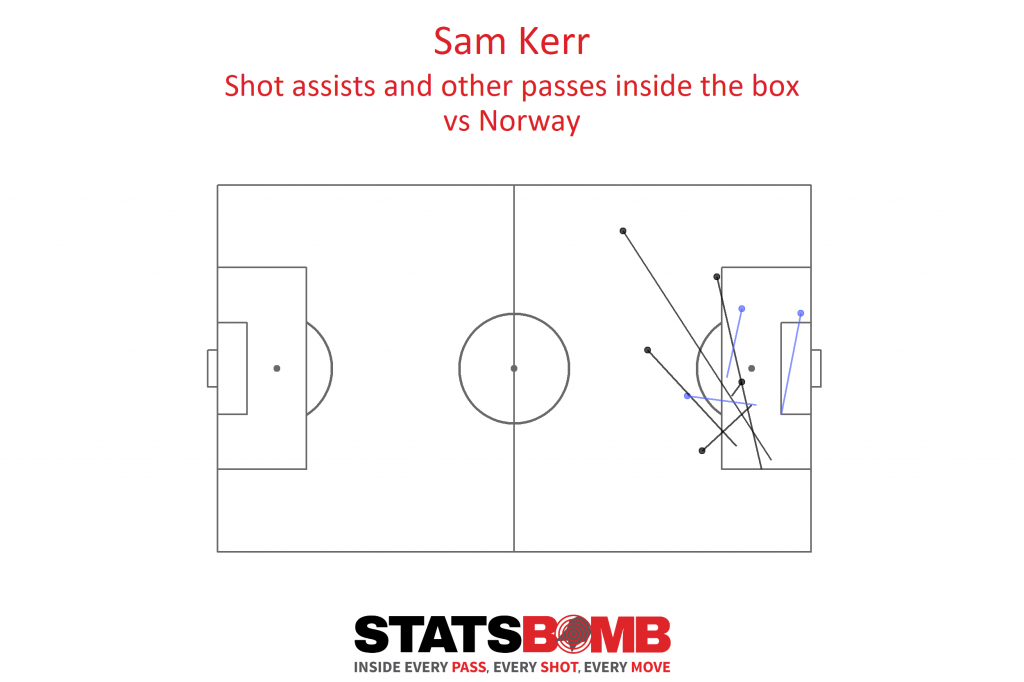

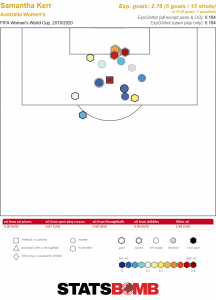

Christiane Endler (Age 27, Chile) Paris Saint-Germain goalkeeper Christiane Endler deserves to be on this list despite her team failing to qualify for the knockout stages. Considering that FIFA unranked the Chilean women’s national team back in 2016 for their own federation’s lack of desire to schedule games for them, the players have been fighting an uphill and many times losing battle. Yet, they should (and hopefully will) take heart from their co-captain’s Player of the Match performance against the champions, despite Chile losing 3-0 and being out possessed 32% to 68%. Endler, born to a German father and a Chilean mother, psyched-out Carli Lloyd enough for the veteran to miss a rare penalty, made six saves from their nine shots on target, and single-handedly restricted team USA, and particularly Christen Press. It was a performance special enough for USWNT legend Hope Solo to dub Endler “ Sam Kerr (Age 25, Australia) Chicago Red Stars and Perth Glory forward Sam Kerr has been a star player well before she was handed the captaincy in February 2019. So, it was no surprise that she stayed cool despite fluffing her penalty in the opener versus Italy and snatched her chance on the rebound. The Matildas may have gone on to lose that game, but they fought hard and were unlucky to concede in stoppage-time for the Le Azzurre comeback. In their next game, the first at France 2019 where both teams were in the top ten of the FIFA World Rankings (Australia on 6 and Brazil 10), Australia found themselves trailing 2-0 in the first half but, this time, clawed their way to their own comeback with Kerr a strong presence. With everything to play for on matchday three in this tournament’s Group of Death, it was The Sam Kerr Show versus Jamaica as she became the first Australian to score a senior World Cup hat-trick and personally guaranteed second spot in a group where goal difference decided all three knockout qualifiers. There's the Sam Kerr Show, and the edge of the six-yard box looks like the Sam Kerr Zone this World Cup.

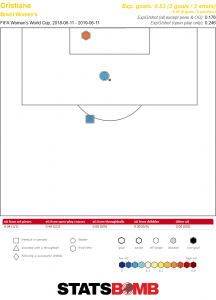

Sam Kerr (Age 25, Australia) Chicago Red Stars and Perth Glory forward Sam Kerr has been a star player well before she was handed the captaincy in February 2019. So, it was no surprise that she stayed cool despite fluffing her penalty in the opener versus Italy and snatched her chance on the rebound. The Matildas may have gone on to lose that game, but they fought hard and were unlucky to concede in stoppage-time for the Le Azzurre comeback. In their next game, the first at France 2019 where both teams were in the top ten of the FIFA World Rankings (Australia on 6 and Brazil 10), Australia found themselves trailing 2-0 in the first half but, this time, clawed their way to their own comeback with Kerr a strong presence. With everything to play for on matchday three in this tournament’s Group of Death, it was The Sam Kerr Show versus Jamaica as she became the first Australian to score a senior World Cup hat-trick and personally guaranteed second spot in a group where goal difference decided all three knockout qualifiers. There's the Sam Kerr Show, and the edge of the six-yard box looks like the Sam Kerr Zone this World Cup.  She ensured that Australia didn’t lose their grip after Havana Solaun scored Jamaica’s first-ever World Cup goal to make it 2-1 and led equally from the front as the back, tracking their players into the Aussie box, defending, harrying, and inspiring her team. Cristiane (Age 34, Brazil) Cristiane, Marta’s replacement for their opening game as the star recovered from injury, lost no time in announcing her intention. At the age of 34 years and 25 days, she beat the record for the oldest player to score a hat-trick in a World Cup, previously held by Cristiano Ronaldo.

She ensured that Australia didn’t lose their grip after Havana Solaun scored Jamaica’s first-ever World Cup goal to make it 2-1 and led equally from the front as the back, tracking their players into the Aussie box, defending, harrying, and inspiring her team. Cristiane (Age 34, Brazil) Cristiane, Marta’s replacement for their opening game as the star recovered from injury, lost no time in announcing her intention. At the age of 34 years and 25 days, she beat the record for the oldest player to score a hat-trick in a World Cup, previously held by Cristiano Ronaldo.  A header, a sliding finish at the back post, and a free-kick off the underside of the crossbar from just outside the box. Brazil 3, Jamaica 0, and just like that Brazil broke their run of losing nine games on the trot. It was harder for them versus Australia who completed an amazing comeback to win 3-2, but not before Cristiane scored her fourth goal of the tournament with a powerful header into the bottom corner. With Brazil qualifying for the next round with potential opponents France or Germany, they need all experienced players in top form. Cristiane seems raring to go, and slowly but surely, so does Marta, who, with her match-winning penalty against Italy, surpassed Miroslav Klose to be the all-time World Cup lead scorer with 17 goals and counting. Notable mention to France’s Amandine Henry and Eugenie Le Sommer, Japan captain Saki Kumagai, England’s Beth Mead, Italy’s Barbara Bonansea and Spain’s Jenni Hermoso. Anushree Nande is a published writer and editor. Hope is her superpower (unsurprisingly she's a Gooner), but sport, art, music and words are good substitutes.

A header, a sliding finish at the back post, and a free-kick off the underside of the crossbar from just outside the box. Brazil 3, Jamaica 0, and just like that Brazil broke their run of losing nine games on the trot. It was harder for them versus Australia who completed an amazing comeback to win 3-2, but not before Cristiane scored her fourth goal of the tournament with a powerful header into the bottom corner. With Brazil qualifying for the next round with potential opponents France or Germany, they need all experienced players in top form. Cristiane seems raring to go, and slowly but surely, so does Marta, who, with her match-winning penalty against Italy, surpassed Miroslav Klose to be the all-time World Cup lead scorer with 17 goals and counting. Notable mention to France’s Amandine Henry and Eugenie Le Sommer, Japan captain Saki Kumagai, England’s Beth Mead, Italy’s Barbara Bonansea and Spain’s Jenni Hermoso. Anushree Nande is a published writer and editor. Hope is her superpower (unsurprisingly she's a Gooner), but sport, art, music and words are good substitutes.

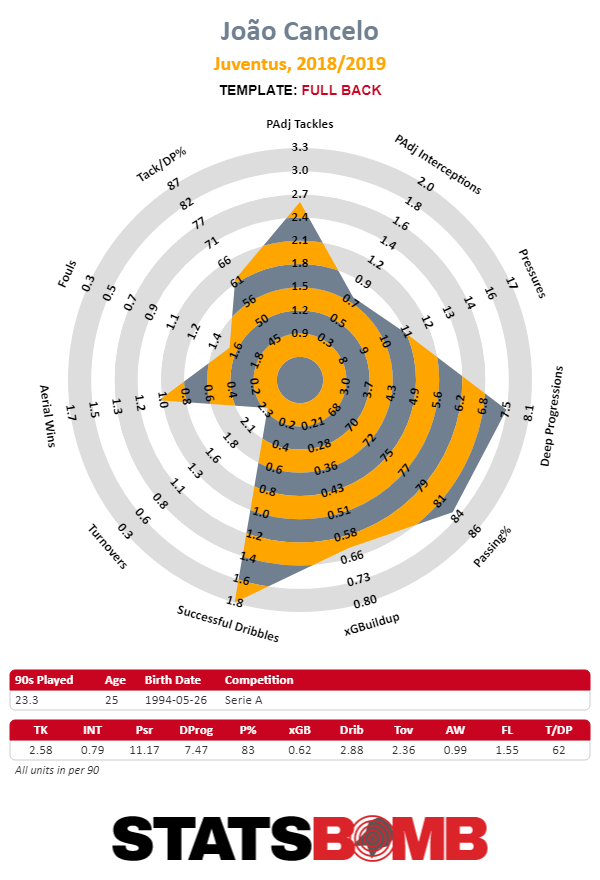

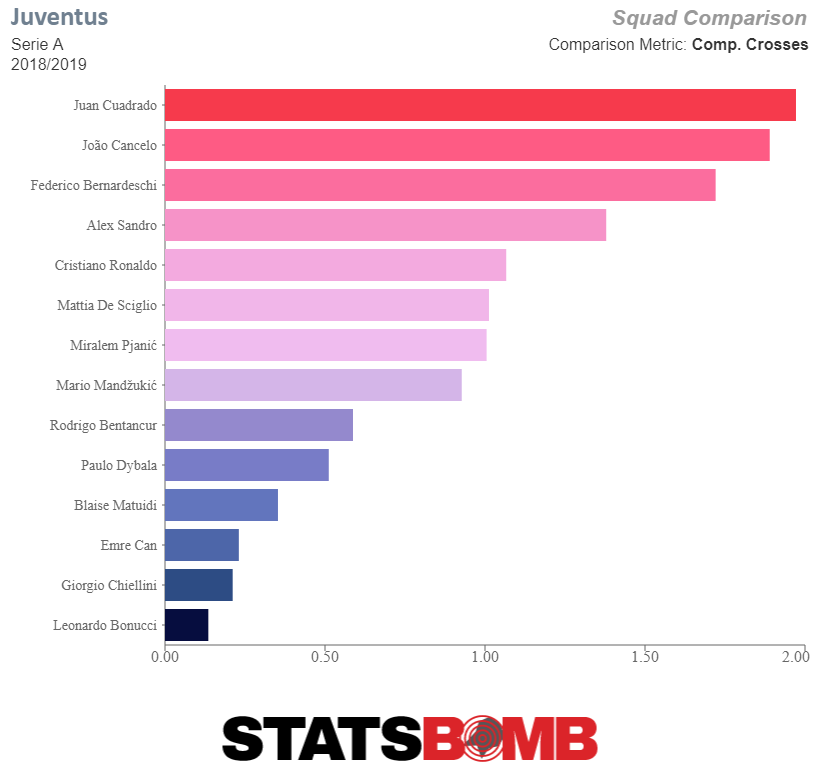

In fact, Cancelo’s service was integral to the Juventus attack. Only the attackers Fernando Bernadeschi and Cristiano Ronaldo assisted more expected goals from open play than Cancelo’s 0.12 per 90 minutes.

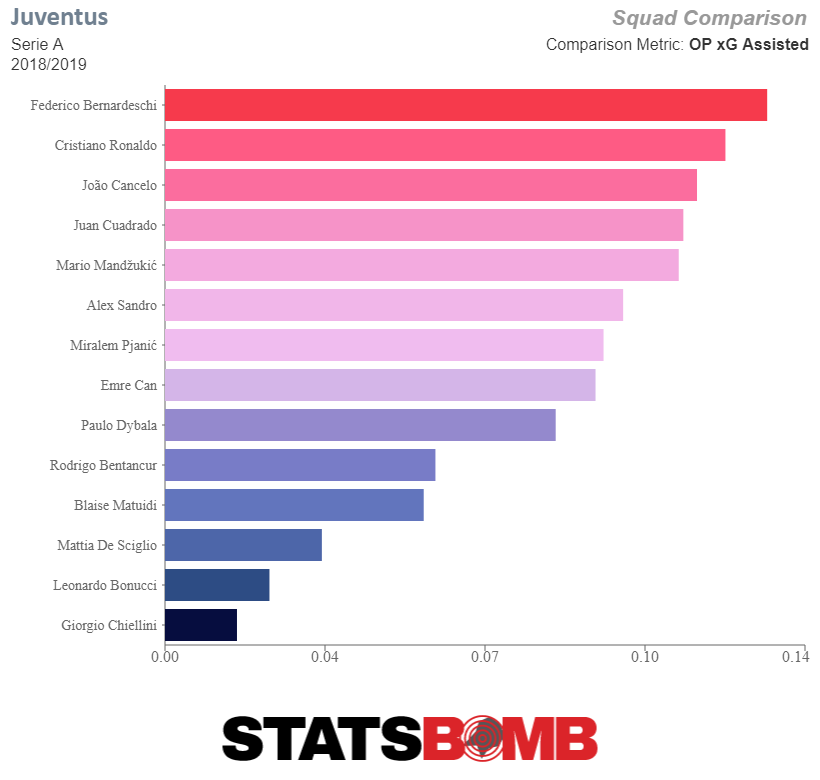

In fact, Cancelo’s service was integral to the Juventus attack. Only the attackers Fernando Bernadeschi and Cristiano Ronaldo assisted more expected goals from open play than Cancelo’s 0.12 per 90 minutes.  Where Cancelo separates himself from other fullbacks is that in addition to providing attacking width in the final third, he was a huge asset when it came to bringing the ball up the field. Only Miralem Pjanić, the team’s midfield hub, had more deep progressions of the ball per 90 minutes than Cancelo’s 7.47.

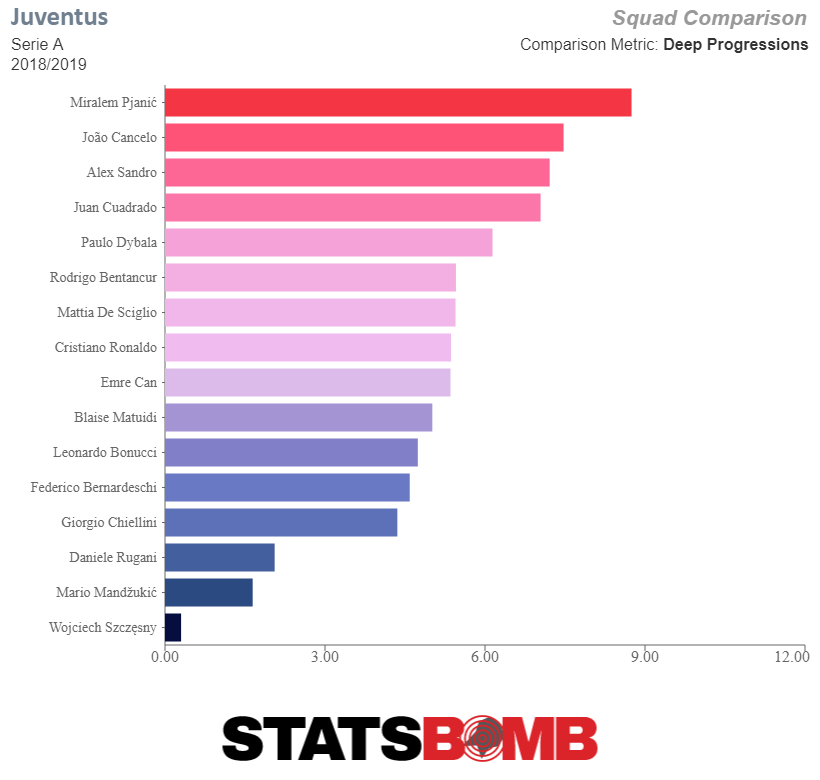

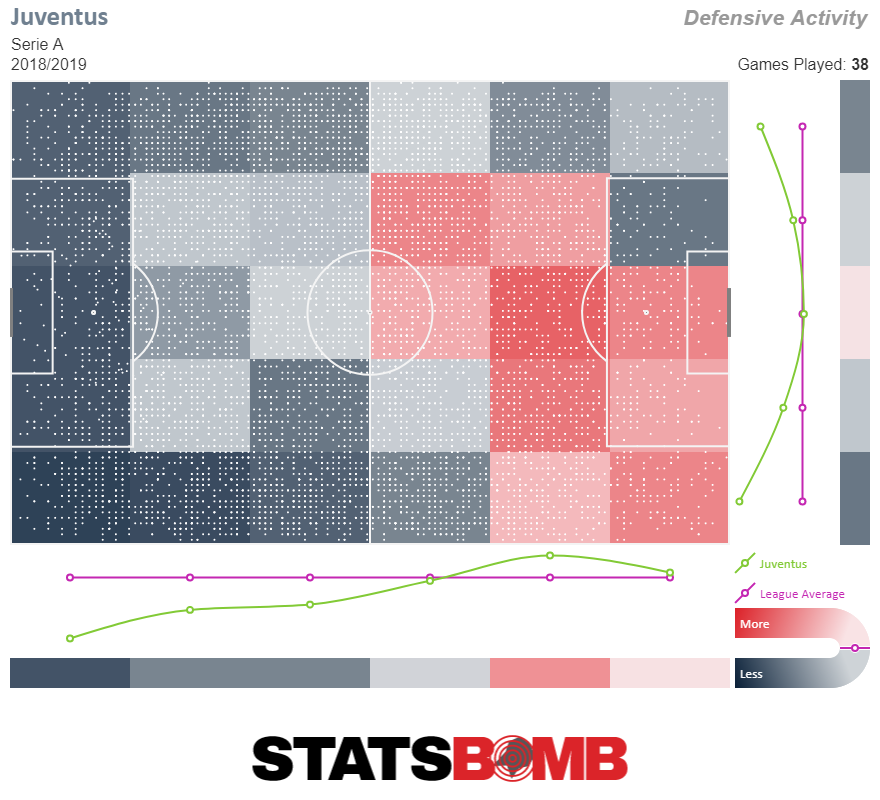

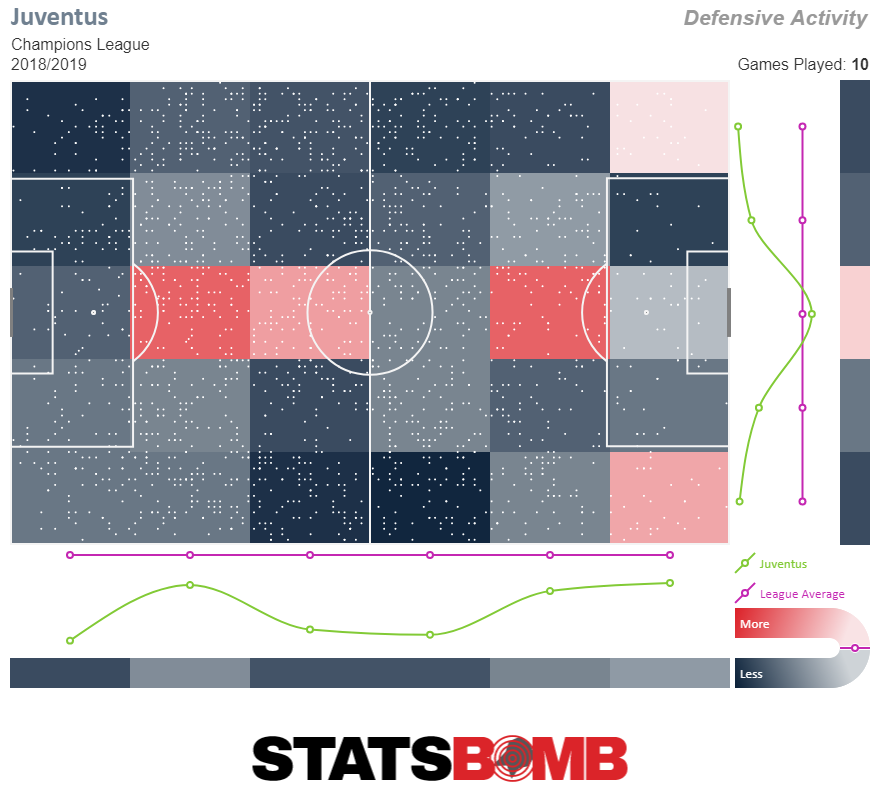

Where Cancelo separates himself from other fullbacks is that in addition to providing attacking width in the final third, he was a huge asset when it came to bringing the ball up the field. Only Miralem Pjanić, the team’s midfield hub, had more deep progressions of the ball per 90 minutes than Cancelo’s 7.47.  When teams looked to shutdown Pjanić’s passing, it was Cancelo who would step into the gap and transition Juventus into the attacking third of the field. Of course, some of this ability is system driven. On the opposite flank, Alex Sandro was third in deep progressions, and Cuadrado (who despite nominally being a winger largely played the same role as Cancelo), was fourth. But, at the same time, systems are often driven by talent. Juventus couldn’t have succeeded while playing a style that demanded their fullbacks bring the ball up the field if the fullbacks were not, themselves, special talents who were up to the task. So, it seems notable that backup fullback Matteo De Sciglio was not able to replicate those numbers in his minutes, and had a full two fewer deep progressions per 90 when he was on the field. The system empowered the fullbacks but Cancelo (and Sandro) had the ability to take advantage of it. The knock on Cancelo, from Juventus’s perspective was his defending. Over the course of the season he was often overlooked in big matches. This is probably a fair concern, especially for a team that was happy to play extremely defensively in big matches, especially with a one goal lead. And, not only to play defensively, but to defend without the ball. When they were dominating teams they were happy for midfielders to step up and win the ball, as their Serie A defensive heatmap shows.

When teams looked to shutdown Pjanić’s passing, it was Cancelo who would step into the gap and transition Juventus into the attacking third of the field. Of course, some of this ability is system driven. On the opposite flank, Alex Sandro was third in deep progressions, and Cuadrado (who despite nominally being a winger largely played the same role as Cancelo), was fourth. But, at the same time, systems are often driven by talent. Juventus couldn’t have succeeded while playing a style that demanded their fullbacks bring the ball up the field if the fullbacks were not, themselves, special talents who were up to the task. So, it seems notable that backup fullback Matteo De Sciglio was not able to replicate those numbers in his minutes, and had a full two fewer deep progressions per 90 when he was on the field. The system empowered the fullbacks but Cancelo (and Sandro) had the ability to take advantage of it. The knock on Cancelo, from Juventus’s perspective was his defending. Over the course of the season he was often overlooked in big matches. This is probably a fair concern, especially for a team that was happy to play extremely defensively in big matches, especially with a one goal lead. And, not only to play defensively, but to defend without the ball. When they were dominating teams they were happy for midfielders to step up and win the ball, as their Serie A defensive heatmap shows.  But, the difference becomes clear when looking at the Champions League, where the side’s defensive pressure is non-existent.

But, the difference becomes clear when looking at the Champions League, where the side’s defensive pressure is non-existent.  Within that framework, Cancelo is expected to be a perfect positional defender. He needs to move in concert with his teammates, covering runners, maintaining a defensive line, closing off passing lanes, and never make a mistake. In the same way that Allegri’s attacking approach empowered Cancelo, the manager’s defensive choices made his life difficult. Sometimes the defensive needs of the team ended up outweighing his attacking contribution and he found himself riding the pine. There’s a reason he barely topped 2000 league minutes last season. At Manchester City it’s easy to see how Cancelo’s attacking talents might be used. As Kyle Walker has aged he’s gracefully transformed from the speedster controlling the entire flank he once was into a more positionally oriented fullback, often supporting the midfield in attack and playing as almost a third central defender (the role he actually occupied for England at last summer’s men’s World Cup). Having the option to play Cancelo there would give Guardiola the option of playing a fullback who provided more traditional final third contributions (much like Benjamin Mendy does when healthy on the left side). Crucially though, Cancelo brings that ability while also bringing the passing ability in the middle of the field that Guardiola craves from his fullbacks. He’d most likely spend more time in the final third than Walker, while also moving the ball up the field just as much. The interactions between City’s fullbacks and wingers are a key to their success. Guardiola uses different combinations of personnel to accomplish different tactical aims. Sometimes wingers are asked to cut inside and attack the penalty area while fullbacks provide width, sometimes the wingers stay wide and the fullback is held in reserve, while the midfielder attacks the holes that spacing creates. And sometimes the fullback is the one who gets to attack the box aided by wingers positioned wide to stretch the defense. Cancelo can, in theory, fill all of those roles should he be called upon to do so (he can also, its worth noting, fill in on the left if necessary). The major question then is whether Cancelo can pull his weight defensively, an area that Walker has excelled in. The answer is, we have absolutely no idea. He’s never been asked to play in a system like Guardiola’s. At Juventus his problem wasn’t that he got caught up field, it was that while he was defending behind the ball, his awareness wasn’t sharp enough, at least for the exacting standards of Juventus. But, he won’t be asked to defend that way for Manchester City. While it’s unclear exactly how he will be deployed, one thing is certain, City don’t ever want to defend without the ball. Sometimes the fullback is asked to engage high up the field, as part of a traditional counter-press. Other times they might be held in reserve, forming a makeshift back three with the center backs, behind the frontline press of the midfielders and forwards. These were situations he just never has to deal with when manning the right side for Juventus. Maybe he’ll be spectacular, maybe he’ll have a hard time adjusting, there’s not a lot either way to hang a prediction on. But that question, whether Cancelo is good enough defensively for what may very well be the best team in the world, is one that simply differentiates whether Cancelo will be a useful piece, or is the heir apparent to Walker as an every week starter. Cancelo’s attacking numbers are so strong, and so well rounded that there’s no doubt he’ll be an extremely useful contributor for City. But, if he adds to that, and he develops into a solid defensive option in a pressing system, then he has the potential to become truly great. He’d become just another superstar player bought at superstar prices to fill a supporting role for the two time defending Premier League champions.

Within that framework, Cancelo is expected to be a perfect positional defender. He needs to move in concert with his teammates, covering runners, maintaining a defensive line, closing off passing lanes, and never make a mistake. In the same way that Allegri’s attacking approach empowered Cancelo, the manager’s defensive choices made his life difficult. Sometimes the defensive needs of the team ended up outweighing his attacking contribution and he found himself riding the pine. There’s a reason he barely topped 2000 league minutes last season. At Manchester City it’s easy to see how Cancelo’s attacking talents might be used. As Kyle Walker has aged he’s gracefully transformed from the speedster controlling the entire flank he once was into a more positionally oriented fullback, often supporting the midfield in attack and playing as almost a third central defender (the role he actually occupied for England at last summer’s men’s World Cup). Having the option to play Cancelo there would give Guardiola the option of playing a fullback who provided more traditional final third contributions (much like Benjamin Mendy does when healthy on the left side). Crucially though, Cancelo brings that ability while also bringing the passing ability in the middle of the field that Guardiola craves from his fullbacks. He’d most likely spend more time in the final third than Walker, while also moving the ball up the field just as much. The interactions between City’s fullbacks and wingers are a key to their success. Guardiola uses different combinations of personnel to accomplish different tactical aims. Sometimes wingers are asked to cut inside and attack the penalty area while fullbacks provide width, sometimes the wingers stay wide and the fullback is held in reserve, while the midfielder attacks the holes that spacing creates. And sometimes the fullback is the one who gets to attack the box aided by wingers positioned wide to stretch the defense. Cancelo can, in theory, fill all of those roles should he be called upon to do so (he can also, its worth noting, fill in on the left if necessary). The major question then is whether Cancelo can pull his weight defensively, an area that Walker has excelled in. The answer is, we have absolutely no idea. He’s never been asked to play in a system like Guardiola’s. At Juventus his problem wasn’t that he got caught up field, it was that while he was defending behind the ball, his awareness wasn’t sharp enough, at least for the exacting standards of Juventus. But, he won’t be asked to defend that way for Manchester City. While it’s unclear exactly how he will be deployed, one thing is certain, City don’t ever want to defend without the ball. Sometimes the fullback is asked to engage high up the field, as part of a traditional counter-press. Other times they might be held in reserve, forming a makeshift back three with the center backs, behind the frontline press of the midfielders and forwards. These were situations he just never has to deal with when manning the right side for Juventus. Maybe he’ll be spectacular, maybe he’ll have a hard time adjusting, there’s not a lot either way to hang a prediction on. But that question, whether Cancelo is good enough defensively for what may very well be the best team in the world, is one that simply differentiates whether Cancelo will be a useful piece, or is the heir apparent to Walker as an every week starter. Cancelo’s attacking numbers are so strong, and so well rounded that there’s no doubt he’ll be an extremely useful contributor for City. But, if he adds to that, and he develops into a solid defensive option in a pressing system, then he has the potential to become truly great. He’d become just another superstar player bought at superstar prices to fill a supporting role for the two time defending Premier League champions.

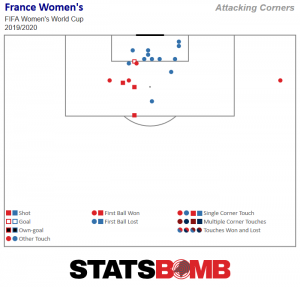

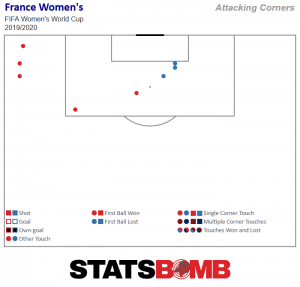

But from the left-hand side, France are much more prone to take the corner short (and also have fewer of them, a symbol of a bit of a right-sided skew in their attack).

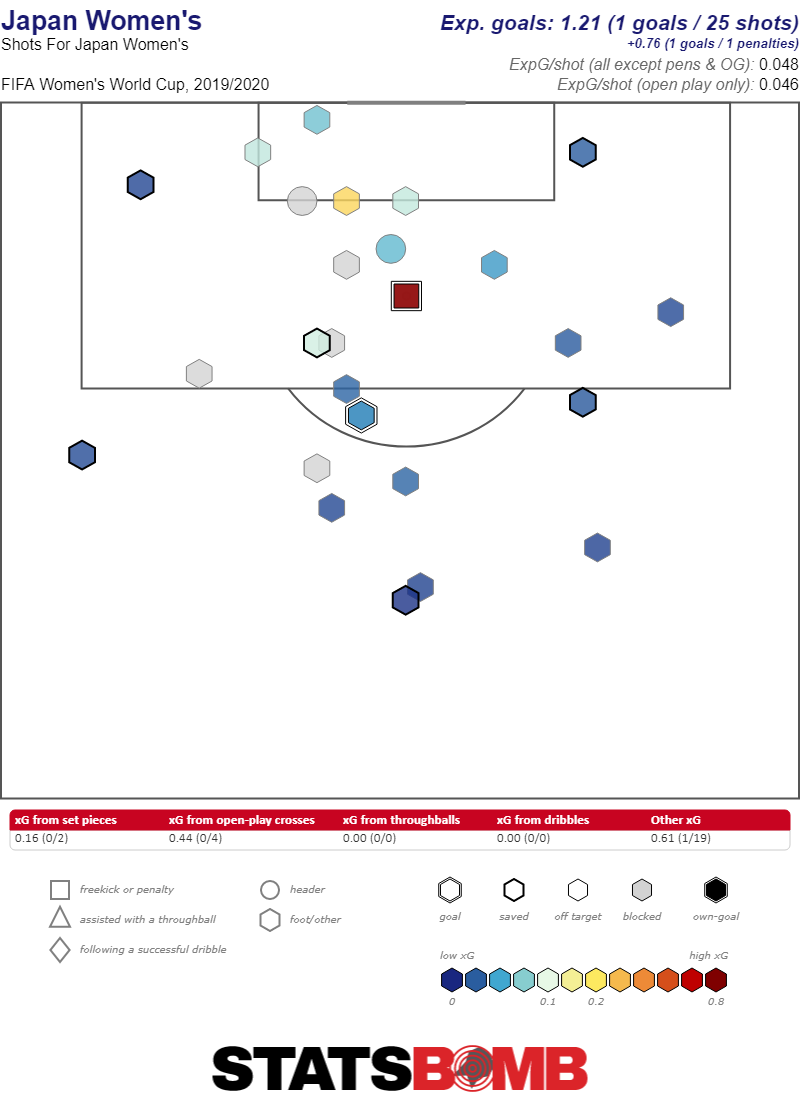

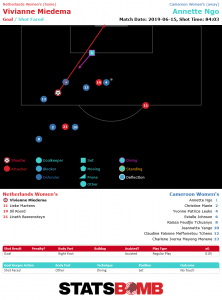

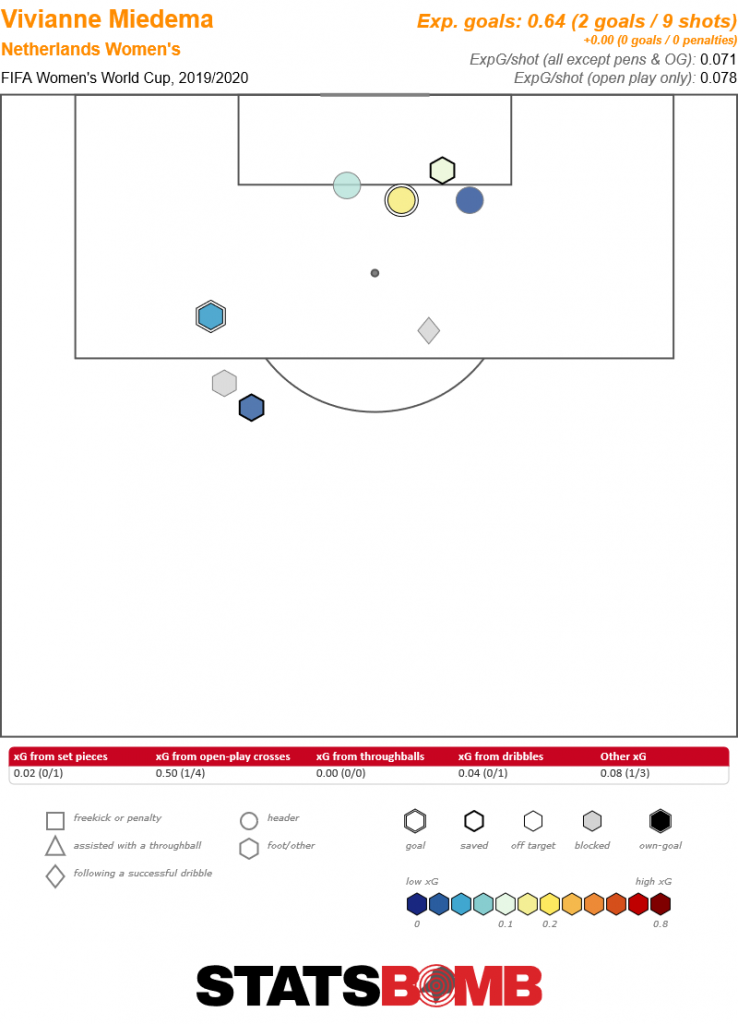

But from the left-hand side, France are much more prone to take the corner short (and also have fewer of them, a symbol of a bit of a right-sided skew in their attack).  Whether France are varying their routines or Renard is just less of a threat than first thought, she's been less active in the second two rounds of Group B action. After her two goals against Korea, she's taken just one further headed shot. A possible lack, or drying up, of service is something that the Netherlands might have on their minds. After two comfortable enough victories against Cameroon and New Zealand it won't be a major concern, but despite becoming the nation's leading scorer, Vivanne Miedema hasn't gotten the chances that she did in the league this season. Part of this may just be the change in levels between Arsenal's strength relative to the rest of the FA Women's Super League and the Netherlands relative to their World Cup opposition, but the difference in their shot maps is stark. Barring one chance, all of her World Cup shots close to goal have been headers and the average expected goals value of her shots has halved.

Whether France are varying their routines or Renard is just less of a threat than first thought, she's been less active in the second two rounds of Group B action. After her two goals against Korea, she's taken just one further headed shot. A possible lack, or drying up, of service is something that the Netherlands might have on their minds. After two comfortable enough victories against Cameroon and New Zealand it won't be a major concern, but despite becoming the nation's leading scorer, Vivanne Miedema hasn't gotten the chances that she did in the league this season. Part of this may just be the change in levels between Arsenal's strength relative to the rest of the FA Women's Super League and the Netherlands relative to their World Cup opposition, but the difference in their shot maps is stark. Barring one chance, all of her World Cup shots close to goal have been headers and the average expected goals value of her shots has halved.

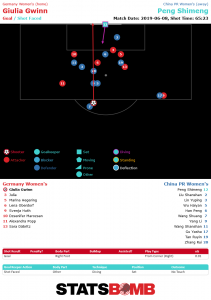

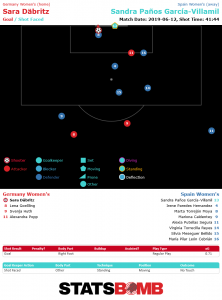

Looks can be deceiving though. Take a look at Germany. Although they've gotten through Group B as group winners on nine points, in their two games against Spain and China their expected goals didn't even break even (0.79 vs 0.83 expected goals per game). Using expected goals over such a small sample has its limitations, but it also doesn't fill one with confidence. They won each of those games 1-0, with the goals coming from one worldie (well, ish) and one tap-in rebound.

Looks can be deceiving though. Take a look at Germany. Although they've gotten through Group B as group winners on nine points, in their two games against Spain and China their expected goals didn't even break even (0.79 vs 0.83 expected goals per game). Using expected goals over such a small sample has its limitations, but it also doesn't fill one with confidence. They won each of those games 1-0, with the goals coming from one worldie (well, ish) and one tap-in rebound.