Around this time last year I looked at five Ligue 1 prospects outside of the four traditional big clubs in France, as a way of illustrating the deep talent pool that exists in Ligue 1. Looking back a year later and it’s interesting to see where each prospect stands. Both Nordi Mukiele and Yves Bissouma made moves to clubs outside of Ligue 1 in RB Leipzig and Brighton respectively, Jonathan Bamba was signed by Lille, while Wylan Cyprien and Ismaila Sarr stayed at their respective clubs.

With Mukiele, his sample size of 711 minutes in the Bundesliga makes it rather hard to have strong opinions on his season either way. In the case of Bissouma, it’s fair to say that Brighton haven’t gotten their full value in season one. That’s not to say that Bissouma hasn’t shown signs of the upside that he has but the totality of his season has been shaky (though there’s also something to be said about how tough it can be for new players to transition their play style into a Chris Hughton led side).

Both Cyprien and Bamba have more or less been at the same level that they were the season prior, but at least Bamba moved to a club that has a very good chance of playing in the Champions League next season. Sarr is arguably the only player to have their stock rise a year later, as he’s added more functional playmaking to complement his direct style of play and become a more well-rounded threat, setting himself up for a potential noteworthy transfer this summer.

In the spirit of last year’s iteration, this article will follow a somewhat similar format. Instead of focusing solely on Ligue 1 young talents, we’ll be looking more at Europe as a whole. None of the three players profiled currently ply their trade in one of the big clubs in their respective leagues. As well, each player is 23 or under as of March 29, 2019. It follows the same idea where we’re trying to profile players that at the very least will have several prominent years ahead of them.

Without further ado, let’s get to it:

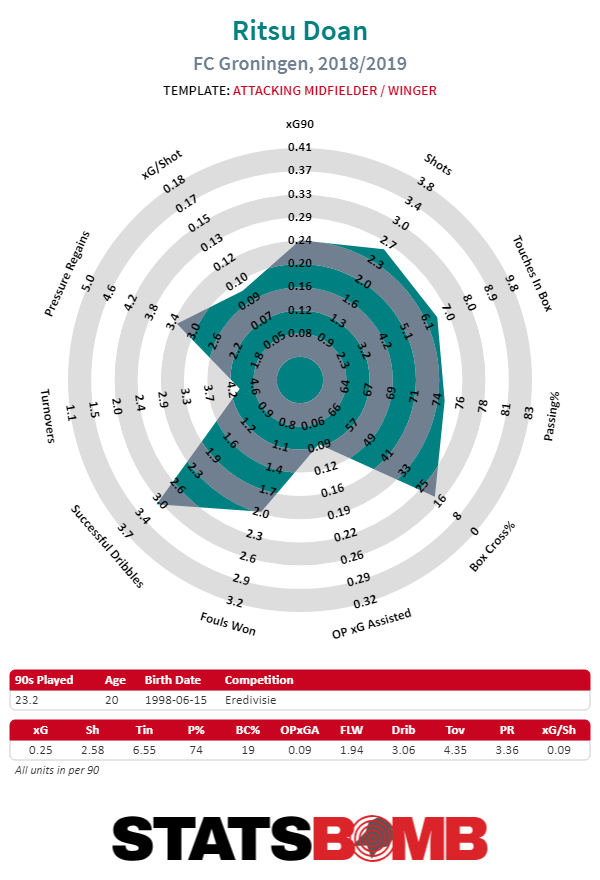

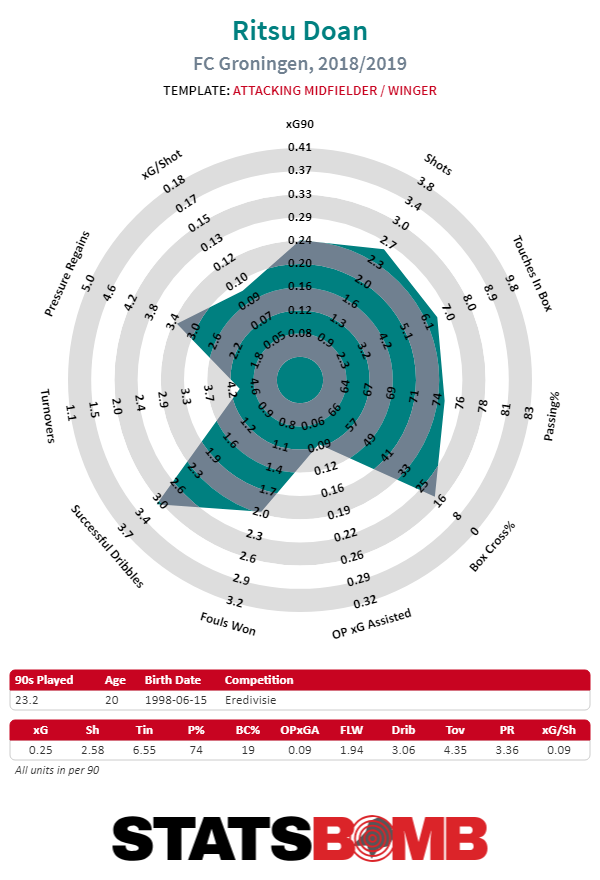

Ritsu Doan (Groningen, 20)

As the modern game has continued to evolve, it’s become more apparent that to succeed at the highest level, wide players must have a requisite level of passing skills to go along with high level athleticism.

Though it's not uniform across the board, as you’ll find wingers who don’t necessarily fit that combination and still perform at a top level, more and more of the best teams employ wingers that have that combination of on-ball skills and upper tier athletic gifts.

That’s what makes someone like Ritsu Doan an interesting winger to profile. On the surface, Doan’s statistical production doesn’t necessarily jump off the screen as both his shot and xG contribution is rather ordinary.

Yet, when watching tape of him, it’s hard not to get intrigued. Sure, playing in the Eredivisie can make it a bit tough to judge young attackers, but given that Doan plays for a smaller Eredivisie side in Groningen, those worries get alleviated to some extent especially given that they rank below average in both shot generation and expected goals for.

In particular, Doan's awareness to attempt high value passes is cause for some optimism. He's first among Groningen players in both throughball passes created and open play passes into the box on a per 90 basis. He's got half of what you would want from a young attacking talent: when he sees an opening to try a high value pass, he's not afraid to take his shot.

As well as his passing, Doan's dribbling abilities are quite pronounced. He's able to apply his skills on the ball to a number of situations, giving himself some versatility. If he's covered in tight areas, he can maneuver himself into some open space to ponder his next action.

He can beat people off the dribble in one on one situations on the flanks, and he has the sudden explosion to pounce on an opening and put an opponent on their heels. Combine that with good balance and some shiftiness when on-ball, and you've got yourself a wide player with some dynamism.

That dribbling ability can also act as a bit of a curse for Doan, as he's prone to having tunnel vision and not picking out an open teammate while he's in full stride. As well, it's not uncommon to see him running into people when he's carrying the ball forward.

But these things are forgivable for a young wide player who isn't on a good team, given that the upside he flashes is tantalizing. Ritsu Doan seems like a good candidate for a bigger Eredivisie club to take a chance on, perhaps not quite yet for the likes of Ajax or PSV, but more so clubs on the next level.

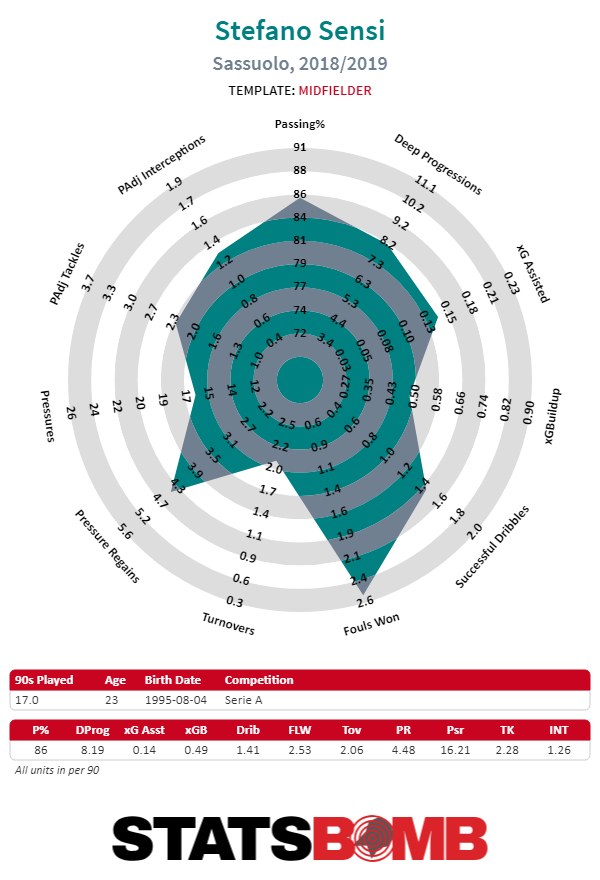

Stefano Sensi (Sassuolo, 23)

Of the three players listed, Stefano Sensi is the one most likely to make the jump to a major European club. At age 23, it makes sense given that he's close enough to his prime years that bigger clubs can envision him coming into their midfield and making an immediate impact.

Sensi is a fascinating figure within Italian football given that he's been looked at as a potential dynamic midfielder for the future. As for this season, he's been part of a Sassuolo side that's had some success playing an adventurous possession game in attack, doing a little bit of everything from the midfield and linking things together.

It isn't hard to see the appeal of Sensi's game. He has decent mobility and the shiftiness to carry the ball on occasion, especially during transition opportunities. On-ball, he's a smooth operator with an array of passes in his arsenal.

He's constantly aware of his surroundings because of his scanning, and in situations where he feels that he's going to be pressured by the opponent, he's happy to recycle the ball and continue possession via one touch passing. Sensi's scanning gets to another part of his game that's quite effective, because of his awareness, he's able to position himself during buildup play where he presents himself as an option for the CB in possession.

If the oppostion tries to take him out as a possible passing option during buildup, he'll try to shift a little bit in one direction to get himself into open space and receive a pass. When you add in the recognition and awareness to attempt difficult long passes, you have the type of midfielder that should fit well at larger Serie A clubs.

One area that will be interesting to monitor is how Sensi would fit defensively at a new club. Sassuolo have not been good on defense this season as they're 5th from the bottom in Serie A in xG conceded. Sensi's defensive output is decent when accounting for Sassuolo's defensive style.

In metrics that try to analyze how much a club presses, like passes allowed per defensive action or how far away from their own goal a team perform's defensive action, Sassuolo rank at the lower end of the table. Even within Sassuolo's defensive inadequacies, you'll see moments where Sensi's defensive awareness is present, whether it be shutting off passing lanes or making timely gambles on defensive actions.

The reported links to Milan make sense given that Milan have similar pressing metrics to Sassuolo, but they've done what Sassuolo haven't been able to in ably suppressing shot volume and location, so transitioning could be smoother there than at other clubs.

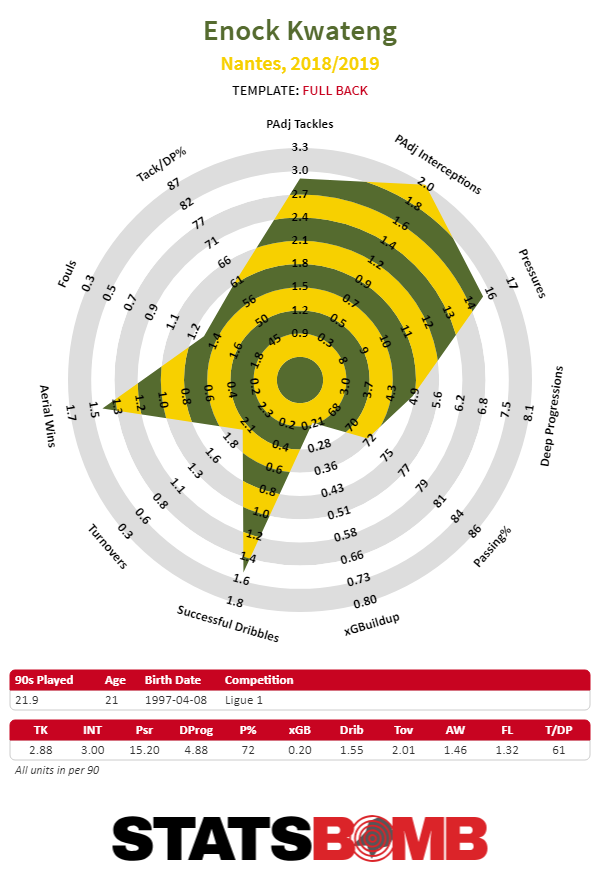

Enock Kwateng (Nantes, 21)

Ligue 1 is always fascinating to analyze when it comes to young talents, as the league offers the best balance of high upside prospects at affordable pricing. This upcoming summer will be of particular interest because there are three right-backs who don't play for major French clubs that have relatively high ceilings: Enock Kwateng, Valentin Rosier, and Youcef Atal.

Atal has the highest ceiling of the three, and it's been interesting seeing him play further up the pitch as the season has progressed, but Rosier and Kwateng aren't slouches in their own right. Kwateng in particular has had a productive season with Nantes at age 21.

The defensive output is what stands out here, but I'm more fascinated with what Kwateng can do during possession. He's a decent dribbler but I wouldn't necessarily call him a very good one as a full-back. Where he's particularly good is when he collects a loose ball and immediately makes a snap decision to try and beat the initial man before laying it off to a teammate.

When he's positioned high on the right side, he'll try to make an off-ball run behind the backline to receive the ball in space for potential crosses into the box, though his crossing to this point is fine but nothing special. Kwateng's passing outside of crosses is where I'm most intrigued. It can look a bit awkward at times, but he's shown some decent passing abilities.

If a teammate makes a run to the right wing near the box, he'll attempt lob passes to that area. He also has some comfort attempting passes into the right halfspace if someone is open.

Kwateng's defensive work is a bit of a mixed bag despite the high defensive output. His high positioning during possession means that a quick turnover in play would leave him exposed when play goes the other way. Kwateng has a penchant for gambling when trying to pressure opponents and that leads to him playing a part in unraveling the team's defensive structure.

His awareness off-ball can be lacking as there'll be times where the opposition gets on his blindside and makes runs to the edge of the box. However, his recovery speed is quite good so more times than not, he's able to compensate that with applying late pressure on the opponent to make up for earlier mistakes. When he has to defend in isolation situations on his side where he's not had to move much previously, he's disciplined in not overextending himself.

It's certainly encouraging that in his first full season in a top five league, Enock Kwateng has held his own, though that doesn't necessarily mean that he's tipped for future stardom. What makes him intriguing is that reports suggest that his contract will be expiring after this season, making him a candidate for a free transfer in the summer.

While I don't necessarily think that Kwateng has star-level upside, it's certainly reasonable to think that he can be a solid right-back for years to come. Getting young fullbacks of that caliber for cheap represents massive value for the club, especially for mid-level Premier League clubs in the market for right-backs who are trying to find value in the transfer market while the rest of Europe uses them as an ATM machine. For clubs in Europe, Kwateng represents an opportunity to secure an affordable first XI caliber fullback and reap the rewards in the future.

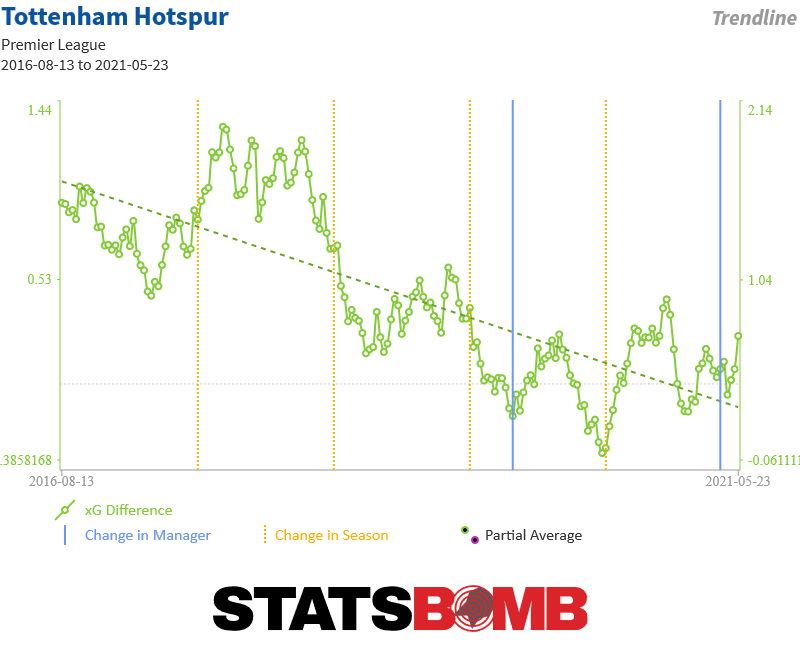

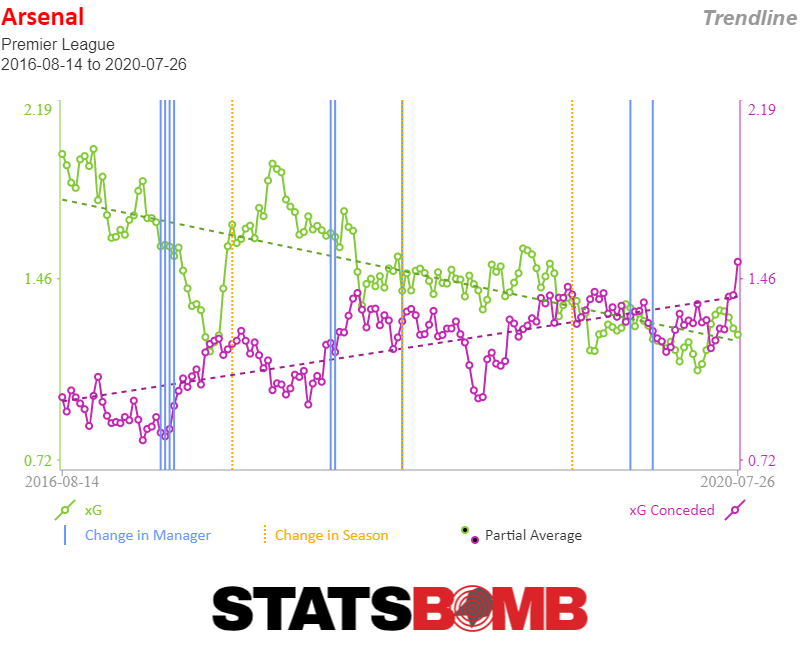

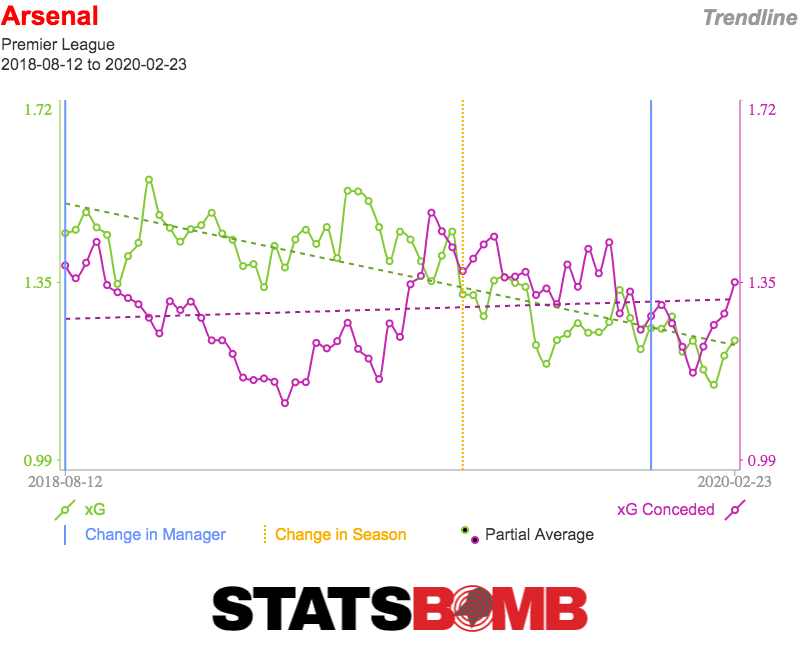

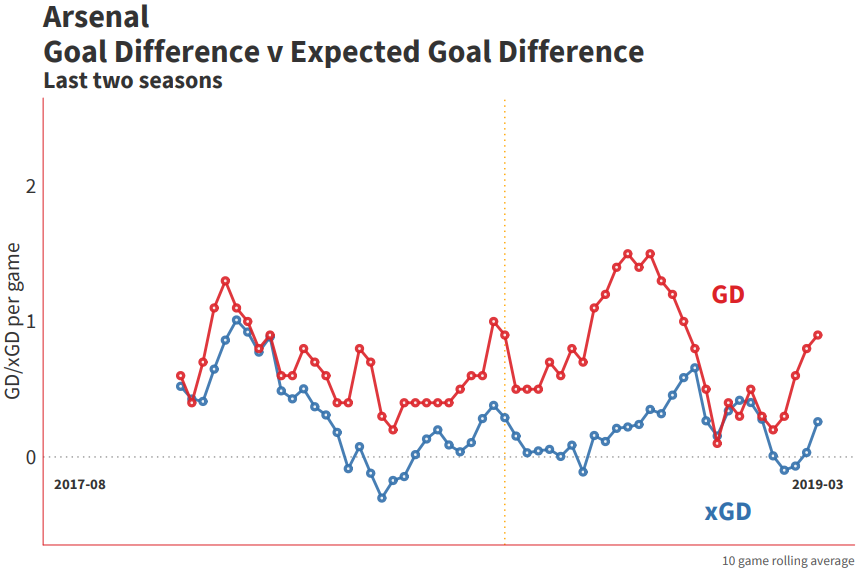

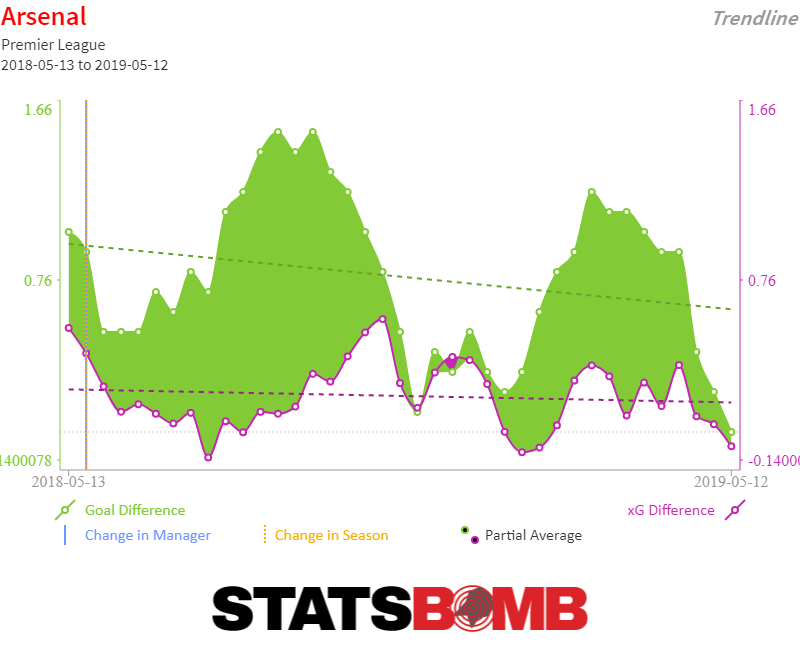

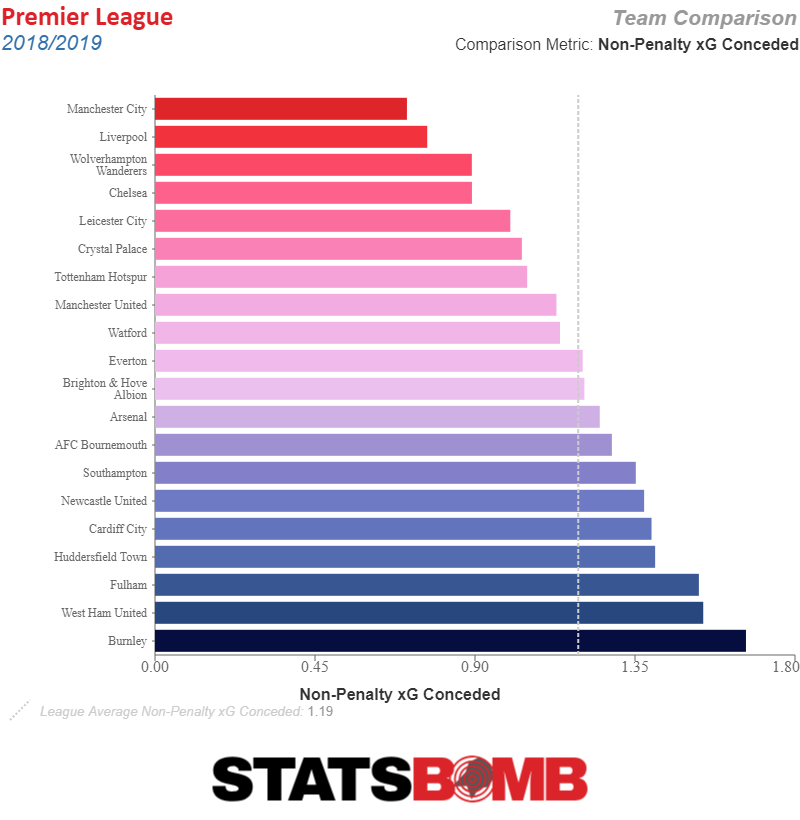

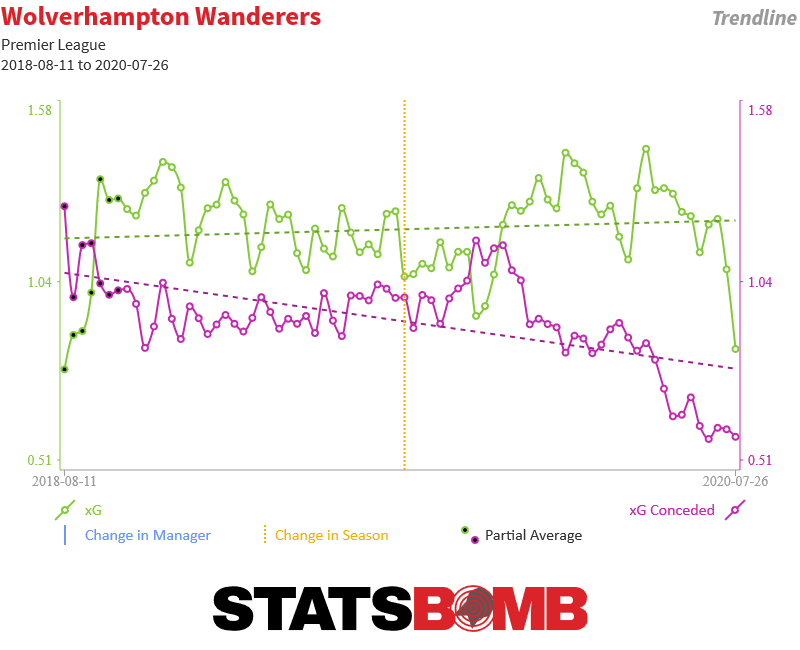

Based on the back of their defensive performance the team actually has (by a narrow margin) the fourth best xG difference in the Premier League. There are reasons to be skeptical of this of course. The story of Manchester United’s season is one of disfunction that likely spilled over into their performance, for example. Arsenal’s defensive numbers have improved over the course of the season in ways that look like they may sustain. The difference between Wolves and Spurs is so small (.03 xG differential per match) that Spurs might pull ahead next week. But still, while the table presents Wolves as clearly the best of the rest, the numbers suggest Wolves might at least be competitive with the top six. The reason that this season has presented that story is that the newly promoted side’s early season results were simply well below their performances.

Based on the back of their defensive performance the team actually has (by a narrow margin) the fourth best xG difference in the Premier League. There are reasons to be skeptical of this of course. The story of Manchester United’s season is one of disfunction that likely spilled over into their performance, for example. Arsenal’s defensive numbers have improved over the course of the season in ways that look like they may sustain. The difference between Wolves and Spurs is so small (.03 xG differential per match) that Spurs might pull ahead next week. But still, while the table presents Wolves as clearly the best of the rest, the numbers suggest Wolves might at least be competitive with the top six. The reason that this season has presented that story is that the newly promoted side’s early season results were simply well below their performances.  Flip that season around, put the more fortunate results at the beginning and the tougher bounces at the end and Wolves season would look like a possible miracle in the making, a newly promoted team hanging around the race for the Champions League well past Christmas. So, while it’s reasonable to argue that the numbers overstate Wolves abilities, it’s also quite clear that the table is understating how good they are. As the season winds down it will be worth watching to see if either side of the equation budges. Are Wolves just the best of the rest, or are they building to something more?

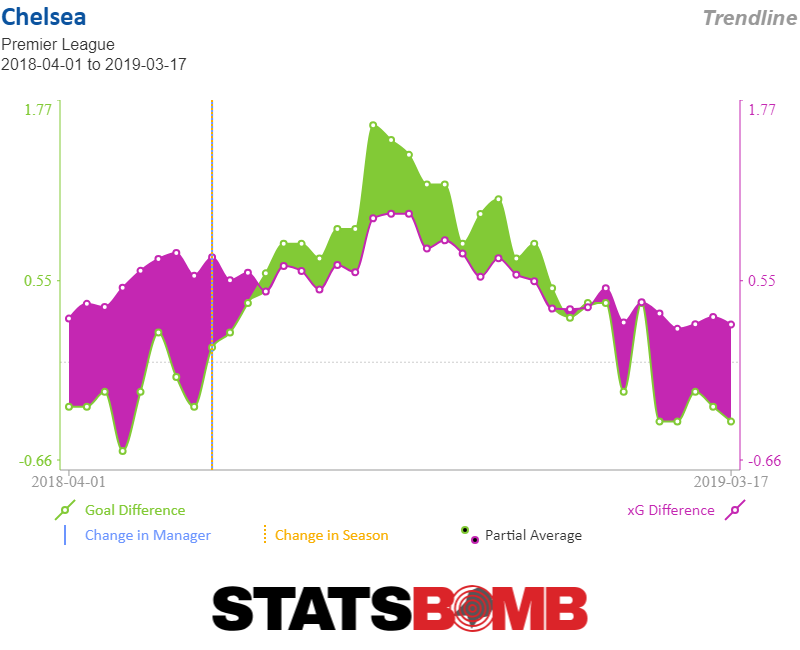

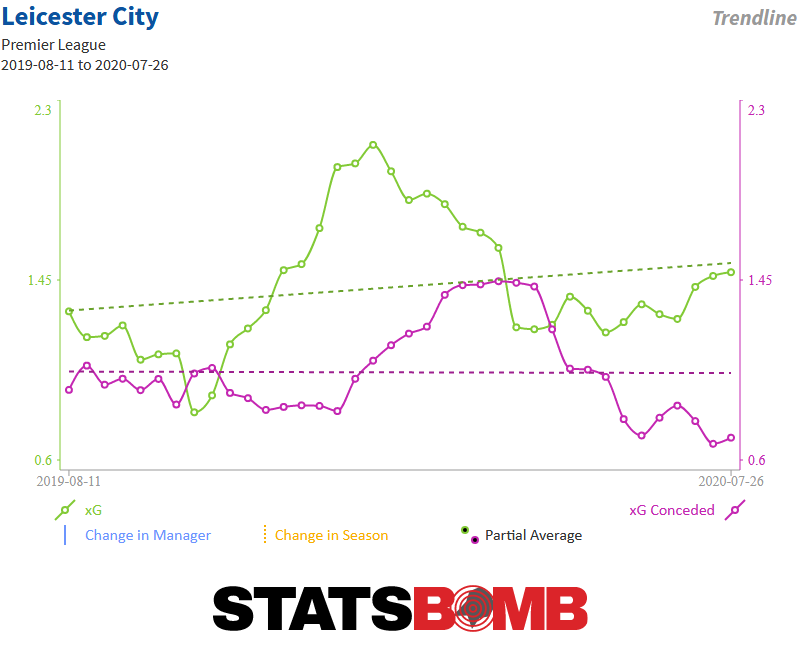

Flip that season around, put the more fortunate results at the beginning and the tougher bounces at the end and Wolves season would look like a possible miracle in the making, a newly promoted team hanging around the race for the Champions League well past Christmas. So, while it’s reasonable to argue that the numbers overstate Wolves abilities, it’s also quite clear that the table is understating how good they are. As the season winds down it will be worth watching to see if either side of the equation budges. Are Wolves just the best of the rest, or are they building to something more?  Starting in January the bottom just fell out of the teams results, even as the performances seemed to indicate that nothing much was wrong. Sometimes that can happen when there are serious problems behind the scenes. Goals and expected goals always converge eventually, but sometimes eventually means after a manager that the players hate gets fired. Other times the manager really has nothing to do with it, and it’s just the fickleness of how the ball bounces that’s messing with the natural order of things. Either way, it seems like a smart time for everybody’s favorite old new manager Brendan Rodgers to step back into the Premier League. He is now at the helm of a team that is due to stop somehow fumbling results that they play well enough to capture. He has experience from way back in his Swansea days taking over a project in midstream. And as long as he doesn’t do anything to drastically mess things up, Leicester City should be just fine. The interesting question to analyze is how much of the team’s expected improvement as the season winds down (and into next year) is actually because Puel did something wrong, something that Rodgers is correcting, and how much is simply that Leicester’s results couldn’t stay that far below expectations forever. What are Bournemouth? After a surprisingly strong start to the season, Eddie Howe’s team have trailed off badly. Neither the beginning of the season nor what came afterwards were particularly a fluke. Their results moved in concert with the levels of their performance (at least until a recent swoon).

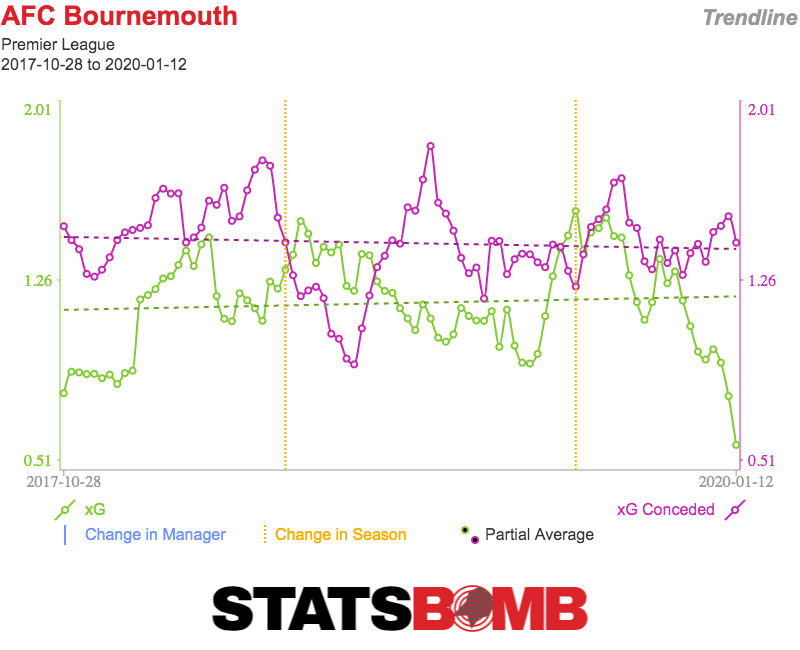

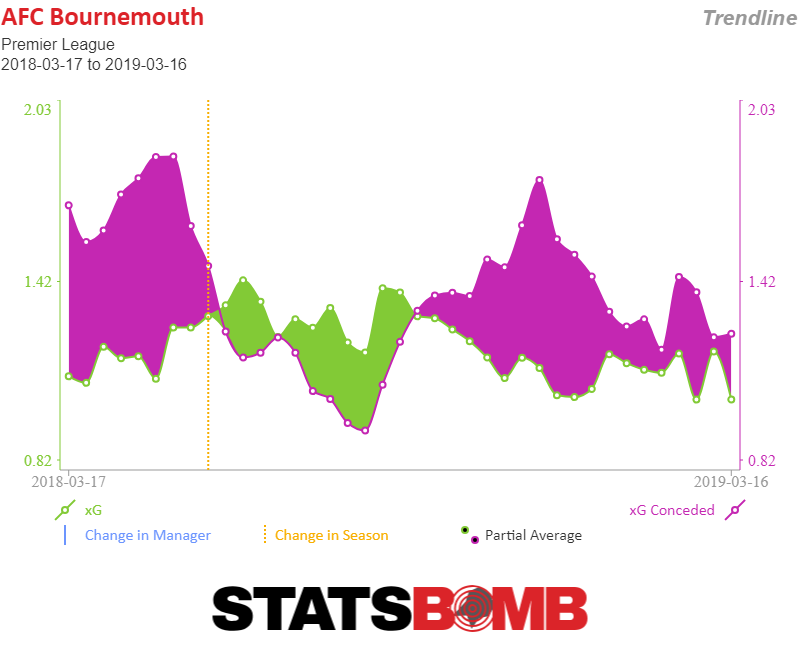

Starting in January the bottom just fell out of the teams results, even as the performances seemed to indicate that nothing much was wrong. Sometimes that can happen when there are serious problems behind the scenes. Goals and expected goals always converge eventually, but sometimes eventually means after a manager that the players hate gets fired. Other times the manager really has nothing to do with it, and it’s just the fickleness of how the ball bounces that’s messing with the natural order of things. Either way, it seems like a smart time for everybody’s favorite old new manager Brendan Rodgers to step back into the Premier League. He is now at the helm of a team that is due to stop somehow fumbling results that they play well enough to capture. He has experience from way back in his Swansea days taking over a project in midstream. And as long as he doesn’t do anything to drastically mess things up, Leicester City should be just fine. The interesting question to analyze is how much of the team’s expected improvement as the season winds down (and into next year) is actually because Puel did something wrong, something that Rodgers is correcting, and how much is simply that Leicester’s results couldn’t stay that far below expectations forever. What are Bournemouth? After a surprisingly strong start to the season, Eddie Howe’s team have trailed off badly. Neither the beginning of the season nor what came afterwards were particularly a fluke. Their results moved in concert with the levels of their performance (at least until a recent swoon).  The culprit seems to have been their defense. After a strong start to the season, Bournemouth’s ability to prevent other teams from getting shots against them has deteriorated dramatically.

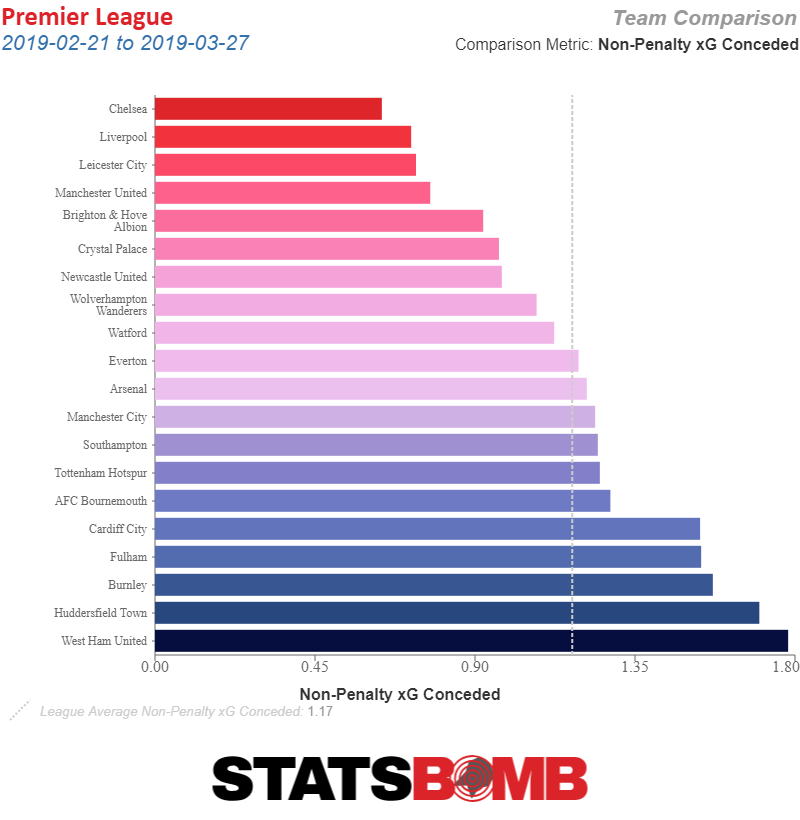

The culprit seems to have been their defense. After a strong start to the season, Bournemouth’s ability to prevent other teams from getting shots against them has deteriorated dramatically.  There are several possible explanations for this. Bournemouth have had a rash of injuries up and down the squad including to Callum Wilson and David Brooks, two of their three most important attacking players. They also started with an easy stretch of schedule which may have juiced their numbers only for the cold hard light of more difficult matches to bring them back to earth. The good news for Howe and his team is that if their inconsistency has been schedule driven, then success may once again be just around the corner. The Cherries have seven matches and remaining, but only one against a top six opponent, a home match against Spurs. They also have three matches against relegation candidates, hosting both Fulham and Burnley, and traveling away to Southampton. Trips to Leicester, Brighton and Crystal Palace make up the balance. A strong close might suggest that the early days of the season weren’t a mirage, but rather a real step forward which injuries eventually derailed, albeit one that was turbocharged by the schedule. However, if Bournemouth continue to struggle right up until the closing bell, well that would end up looking more like a team that’s nothing more than a bottom half side that benefitted from the mirage of a soft opening schedule. Bournemouth may not have anything concrete left to play for besides pride, but there last seven performances will go a long way towards demonstrating where next year’s expectation levels should start. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

There are several possible explanations for this. Bournemouth have had a rash of injuries up and down the squad including to Callum Wilson and David Brooks, two of their three most important attacking players. They also started with an easy stretch of schedule which may have juiced their numbers only for the cold hard light of more difficult matches to bring them back to earth. The good news for Howe and his team is that if their inconsistency has been schedule driven, then success may once again be just around the corner. The Cherries have seven matches and remaining, but only one against a top six opponent, a home match against Spurs. They also have three matches against relegation candidates, hosting both Fulham and Burnley, and traveling away to Southampton. Trips to Leicester, Brighton and Crystal Palace make up the balance. A strong close might suggest that the early days of the season weren’t a mirage, but rather a real step forward which injuries eventually derailed, albeit one that was turbocharged by the schedule. However, if Bournemouth continue to struggle right up until the closing bell, well that would end up looking more like a team that’s nothing more than a bottom half side that benefitted from the mirage of a soft opening schedule. Bournemouth may not have anything concrete left to play for besides pride, but there last seven performances will go a long way towards demonstrating where next year’s expectation levels should start. Header image courtesy of the Press Association