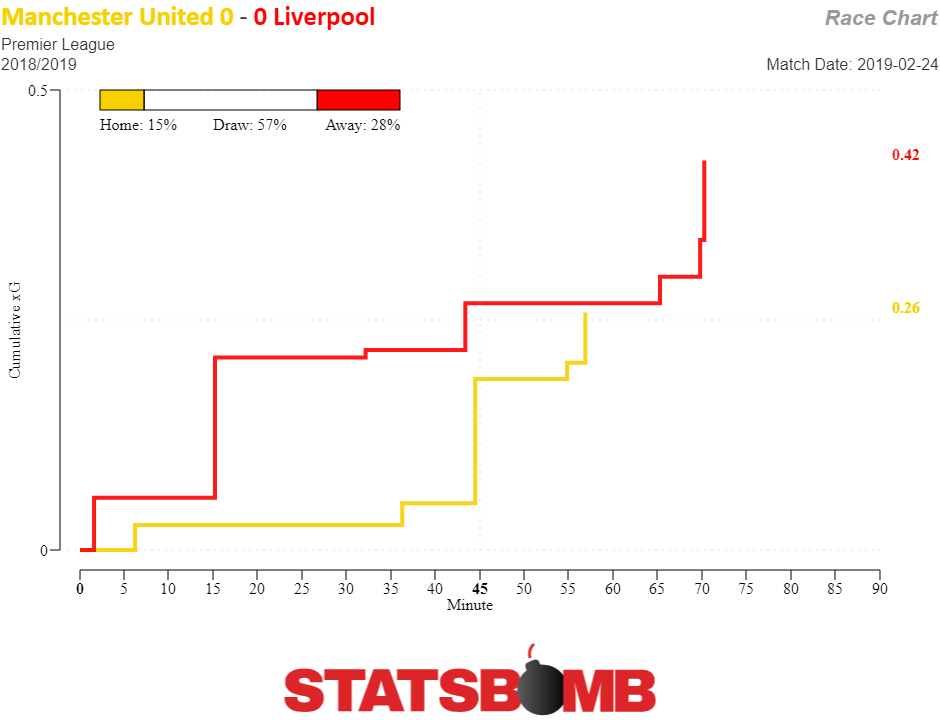

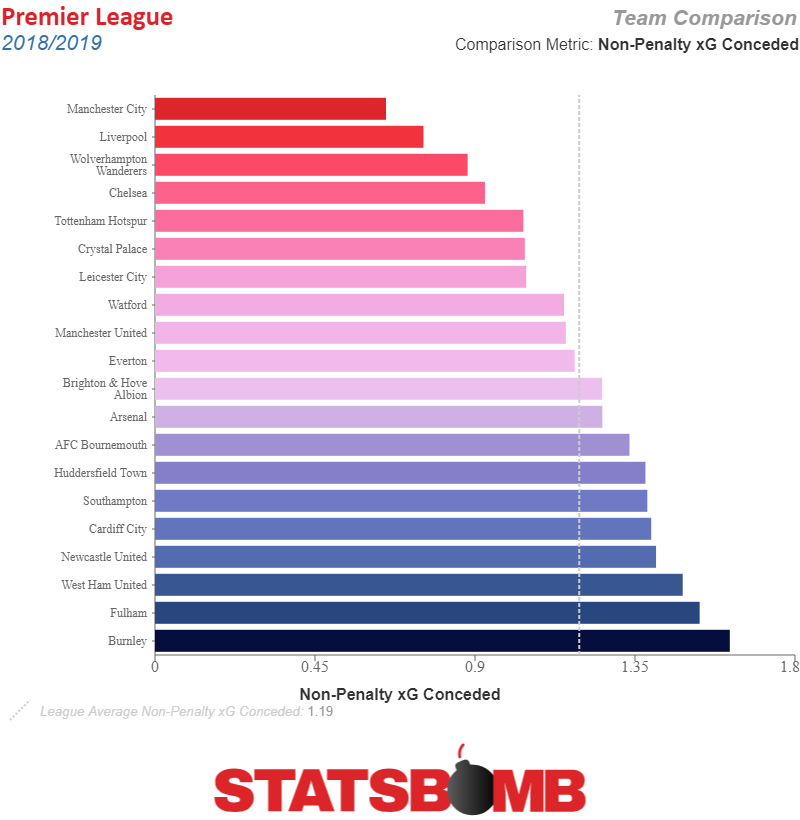

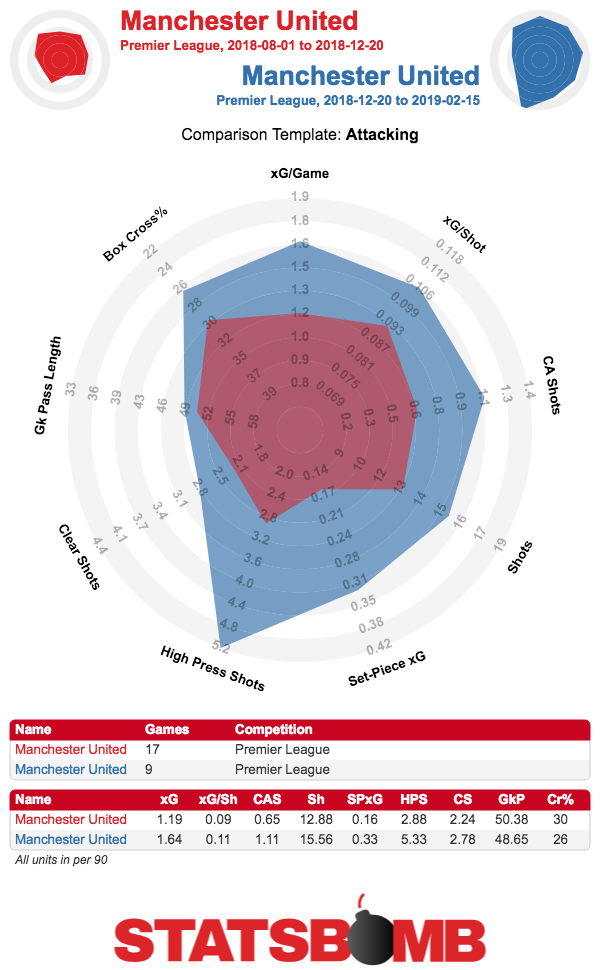

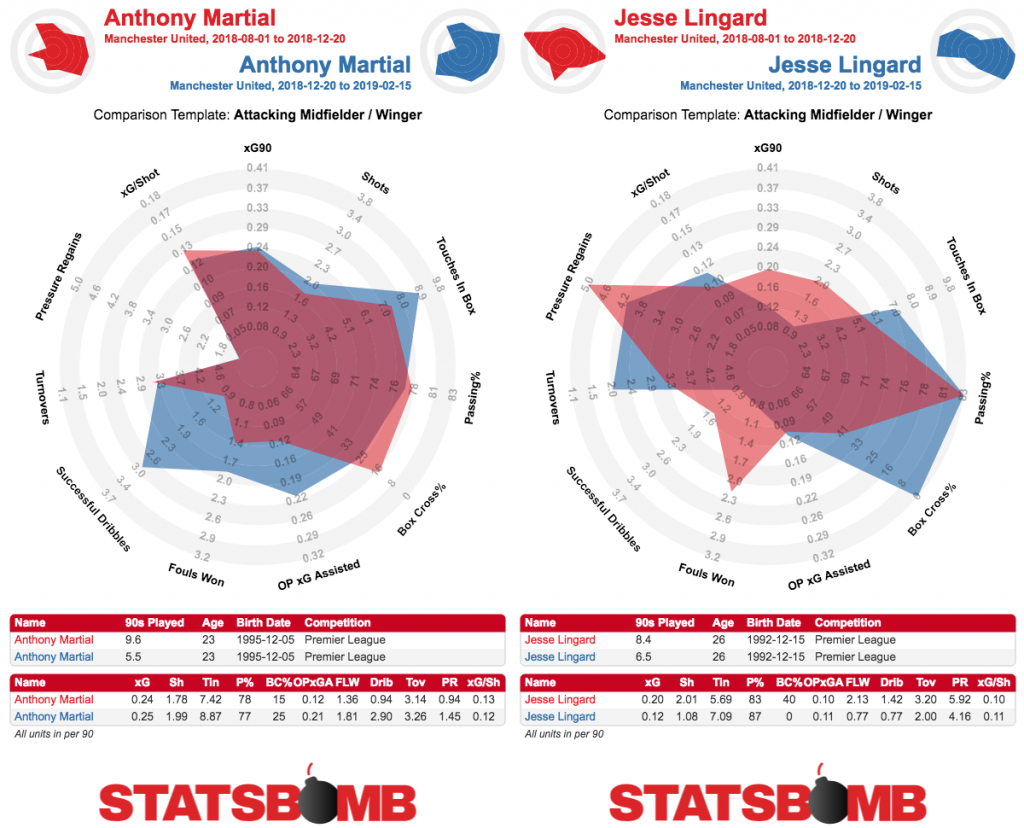

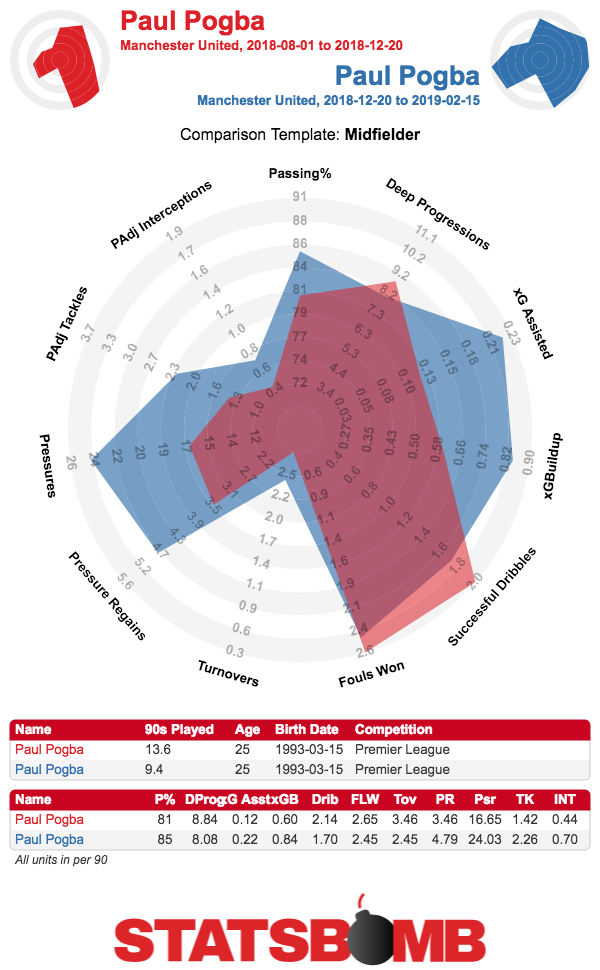

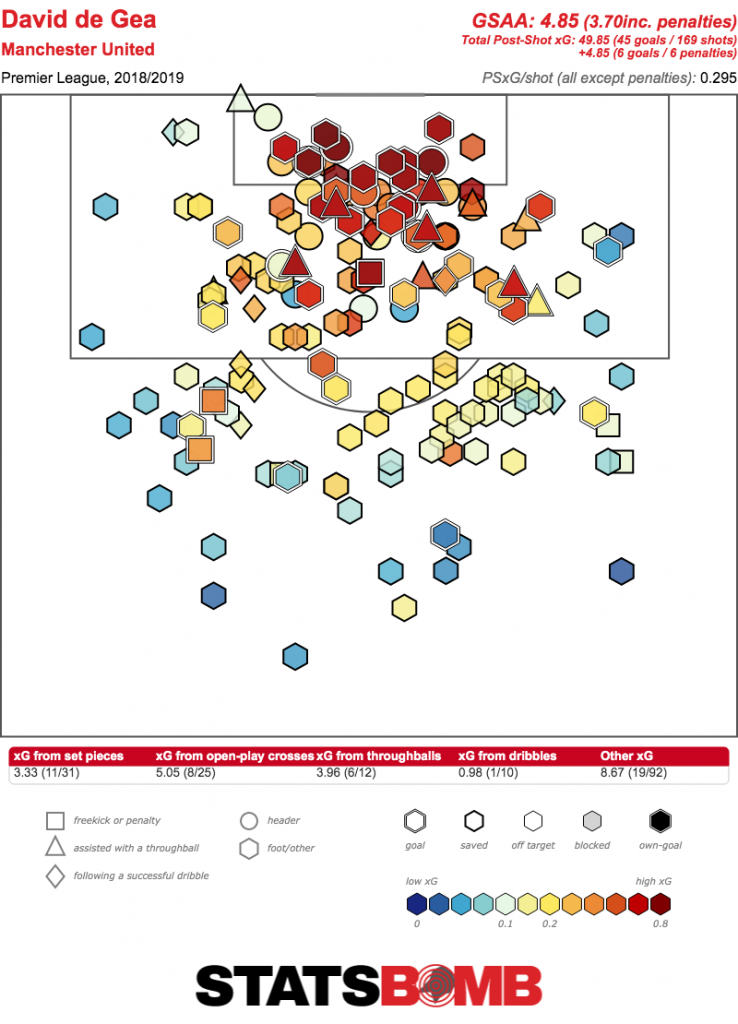

Manchester United held Liverpool to a 0-0 draw at Old Trafford last Sunday. It was a surprising result. United’s resurgence has been built more on an improving attack than a stalwart defense and Liverpool are nothing if not explosive in attack. Next comes the tricky proposition of analyzing what it means. By any standard this match was a defensive one. There were only 12 total shots, seven for Liverpool and five for United. The expected goal tally was 0.42 for Liverpool and 0.26 for United. It was truly a slog of a match.  Injuries, of course, play a large story. United were forced into three first half injury substitutions, with Ander Herera, Juan Mata, and Jesse Lingard (Mata’s replacement) all forced off the field. That left the side unable to rescue Marcus Rashford from his own ankle knock. Rashford spent the bulk of the last hour of the match hobbling around at striker unable to contribute much beyond occasional grimacing link up play to United. Liverpool meanwhile lost Roberto Firmino the creative fulcrum around whom Liverpool frequently pivot between their two preferred formations. Taking all those injuries into account, it’s still eye opening that Liverpool was not able to create more against this depleted United side. United’s resurgence has been built on a more open attack featuring which has unleased Paul Pogba and freed players like Rashford, Lingard, and the also injured Anthony Martial to focus on their attacking responsibilities while trusting themselves to score enough to cover for the defense frailties they might leave exposed behind them. And here they are against Liverpool, even a Liverpool side without Firmino, stand firm and conceding nothing. What to make of that? Apportioning credit and assigning blame after a match like this is a bit like one of those logic problems where you have to figure out if a coin is slightly heavier or slightly lighter than the rest of the bunch. Was the story of this match that Liverpool played badly, thus creating the illusion of a strong United defense, or does United really have some surprising steel under the surface which Liverpool unsuspectingly ran headlong into. Or, as it usually is, is the truth somewhere in the middle. There’s also the challenge of negotiating the difference between these two team’s performance in a single match, and what it means for the rest of the season. It’s possible, for example, that United really did put in a spectacular defensive performance, even while still being only a mediocre defensive team. Alternatively, even if all that happened at Old Trafford was that Liverpool played poorly and Mohammed Salah was off his game, that doesn’t mean that Liverpool are destined to all of a sudden become an attacking struggler. Sometimes even the most potent attacks have off days. And, sure enough, soon after the match Liverpool returned to their high-octane attacking ways and thumped Watford at Anfield 5-0. That is, for comparison’s sake, a Watford side that is roughly equivalent to United in terms of expected goals allowed.

Injuries, of course, play a large story. United were forced into three first half injury substitutions, with Ander Herera, Juan Mata, and Jesse Lingard (Mata’s replacement) all forced off the field. That left the side unable to rescue Marcus Rashford from his own ankle knock. Rashford spent the bulk of the last hour of the match hobbling around at striker unable to contribute much beyond occasional grimacing link up play to United. Liverpool meanwhile lost Roberto Firmino the creative fulcrum around whom Liverpool frequently pivot between their two preferred formations. Taking all those injuries into account, it’s still eye opening that Liverpool was not able to create more against this depleted United side. United’s resurgence has been built on a more open attack featuring which has unleased Paul Pogba and freed players like Rashford, Lingard, and the also injured Anthony Martial to focus on their attacking responsibilities while trusting themselves to score enough to cover for the defense frailties they might leave exposed behind them. And here they are against Liverpool, even a Liverpool side without Firmino, stand firm and conceding nothing. What to make of that? Apportioning credit and assigning blame after a match like this is a bit like one of those logic problems where you have to figure out if a coin is slightly heavier or slightly lighter than the rest of the bunch. Was the story of this match that Liverpool played badly, thus creating the illusion of a strong United defense, or does United really have some surprising steel under the surface which Liverpool unsuspectingly ran headlong into. Or, as it usually is, is the truth somewhere in the middle. There’s also the challenge of negotiating the difference between these two team’s performance in a single match, and what it means for the rest of the season. It’s possible, for example, that United really did put in a spectacular defensive performance, even while still being only a mediocre defensive team. Alternatively, even if all that happened at Old Trafford was that Liverpool played poorly and Mohammed Salah was off his game, that doesn’t mean that Liverpool are destined to all of a sudden become an attacking struggler. Sometimes even the most potent attacks have off days. And, sure enough, soon after the match Liverpool returned to their high-octane attacking ways and thumped Watford at Anfield 5-0. That is, for comparison’s sake, a Watford side that is roughly equivalent to United in terms of expected goals allowed.  And United also reverted to form, although their form is a little harder to parse. They comfortably handled Crystal Palace, going to Selhurst Park and winning 3-1. They also gave up 17 shots in the process and despite spending most of the game with the result never truly looking in doubt, managed to be unconvincing in defense while also scoring a bunch. The earliest of early returns suggest that whatever happened between Liverpool and United at won’t actually have outsized impact on how the two teams continue to play as the season winds down. Figuring out if the coin was slightly heavier or slightly lighter at Old Trafford is an interesting and worthwhile endeavor for understanding the match, but it’s possible that it’s also one that won’t shed much light on the futures of the two teams involved. Narrowly this makes sense. Liverpool might not have been prepared to deal with losing Firmino in the moment, and his replacement, Daniel Sturridge remained largely invisible after coming on. But, given even half a week to prepare, instead of deploying Sturridge, they shifted Sadio Mane up top and started Divock Origi on the left. Meanwhile, United, outside of the context of being injured beyond belief and trying to defend and survive against a great Liverpool side, went back to their swashbuckling, if slightly vulnerable ways. Broadly this makes sense too. The search to find meaning in the Premier League’s marquee matchups is understandable but often flawed. The biggest matches of the season are often defined by two teams wrestling imperfectly to stamp their influence on a match. Results are frequently defined by which teams gets to play their preferred strategy and which team is forced to adjust. Who wins those encounters matters to an outsized degree, because in a closely contested league, every point counts, giving added importance to those moments when a squad gets to both gather points for themselves while also denying their rivals an opportunity to do the same. But, at the same time, those matches are often not the best indicators of how good a team is. The individual factors at play in an individual match between two heavyweights are often outweighed over the course of a season by how teams play against everybody else. Liverpool’s attack is great because it brings the pain week in and week out. The stutter against United isn’t bad luck, but it’s also not more important than everything else we’ve seen. The same is true of United’s defense. The concerns remain despite the performance against Liverpool. Any time Liverpool go to Old Trafford it’s a massive match. The points won and lost will frequently be consequential in the standings at the lofty end of the table. It’s important to understand why and how those games end the way they do. It’s also important to understand the limits of what they can tell us about the two teams competing in those matches. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

And United also reverted to form, although their form is a little harder to parse. They comfortably handled Crystal Palace, going to Selhurst Park and winning 3-1. They also gave up 17 shots in the process and despite spending most of the game with the result never truly looking in doubt, managed to be unconvincing in defense while also scoring a bunch. The earliest of early returns suggest that whatever happened between Liverpool and United at won’t actually have outsized impact on how the two teams continue to play as the season winds down. Figuring out if the coin was slightly heavier or slightly lighter at Old Trafford is an interesting and worthwhile endeavor for understanding the match, but it’s possible that it’s also one that won’t shed much light on the futures of the two teams involved. Narrowly this makes sense. Liverpool might not have been prepared to deal with losing Firmino in the moment, and his replacement, Daniel Sturridge remained largely invisible after coming on. But, given even half a week to prepare, instead of deploying Sturridge, they shifted Sadio Mane up top and started Divock Origi on the left. Meanwhile, United, outside of the context of being injured beyond belief and trying to defend and survive against a great Liverpool side, went back to their swashbuckling, if slightly vulnerable ways. Broadly this makes sense too. The search to find meaning in the Premier League’s marquee matchups is understandable but often flawed. The biggest matches of the season are often defined by two teams wrestling imperfectly to stamp their influence on a match. Results are frequently defined by which teams gets to play their preferred strategy and which team is forced to adjust. Who wins those encounters matters to an outsized degree, because in a closely contested league, every point counts, giving added importance to those moments when a squad gets to both gather points for themselves while also denying their rivals an opportunity to do the same. But, at the same time, those matches are often not the best indicators of how good a team is. The individual factors at play in an individual match between two heavyweights are often outweighed over the course of a season by how teams play against everybody else. Liverpool’s attack is great because it brings the pain week in and week out. The stutter against United isn’t bad luck, but it’s also not more important than everything else we’ve seen. The same is true of United’s defense. The concerns remain despite the performance against Liverpool. Any time Liverpool go to Old Trafford it’s a massive match. The points won and lost will frequently be consequential in the standings at the lofty end of the table. It’s important to understand why and how those games end the way they do. It’s also important to understand the limits of what they can tell us about the two teams competing in those matches. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

Month: February 2019

League One Review: The Championship Awaits, But For Who?

Not a season goes by without the words “Premier League” and “Best League In The World” being uttered in the same sentence.

The statement does, of course, have some merit and, in terms of the quality of playing and management personnel, it’s probably true. However, look below it and you’ll find stalwarts of the EFL leagues who know that it’s rarely the most entertaining nor even the most competitive league in England, let alone the rest of the world.

This season, League One has made a strong claim to be the most compelling with a heated title and automatic promotion race and a relegation battle that at the time of writing involves pretty much the entire bottom half with just a third of the season remaining.

At the summit, there’s three places up for grabs in next season’s Championship table and as we now enter the home straight, it’s the perfect time to put the Championship elect under the microscope and see what they’re doing right – or wrong – in their attempts to ascend into the second tier.

Doncaster:

If the season started from scratch, Doncaster would be much more favoured for a top two finish than they currently are now.

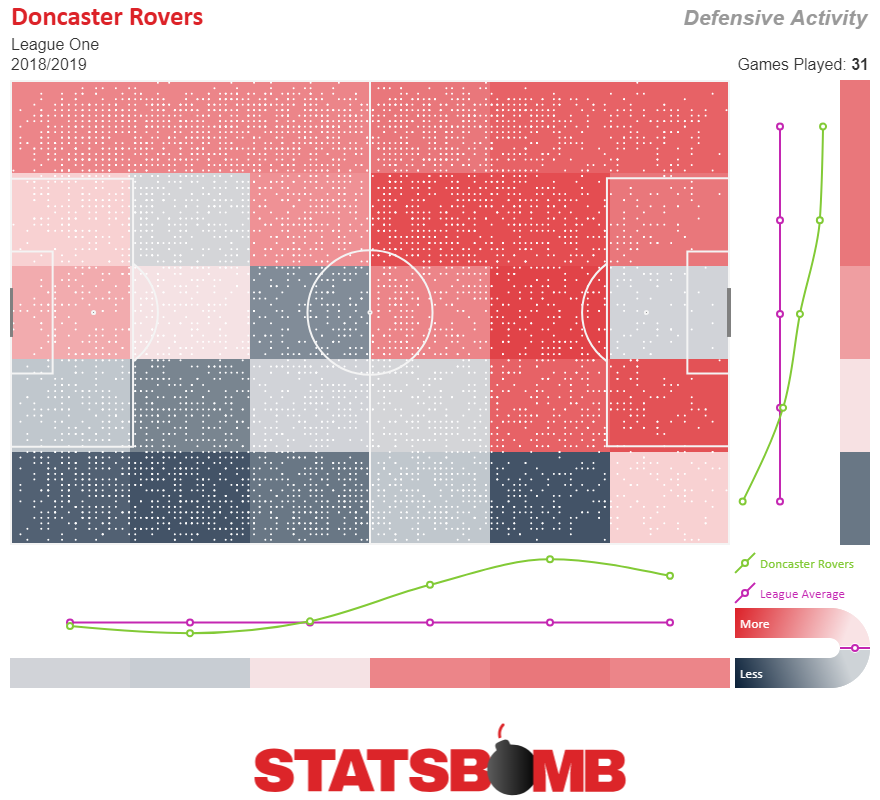

Thanks to a run of poor form pre-Christmas, Donny fell out of the top six but a recent revival has seen them angle their way back in and it’d be a major surprise if they were to fall away now. Their expected goal difference of 0.41 goals per game across the season is actually the fourth best in the league up to now and comfortably so. Doncaster will be a force in the playoffs and could even be the team to fear going into them with their press looking more restrictive than ever.

Developing the press has been a process and in fact defensive solidity has, up until recently, been Doncaster’s weakness – they’ve kept just eight clean sheets all season. Their expected goals conceded has been gradually trending downward however, a sign that the team could be starting to play to their full potential with manager Grant McCann still only in the job for eight months.

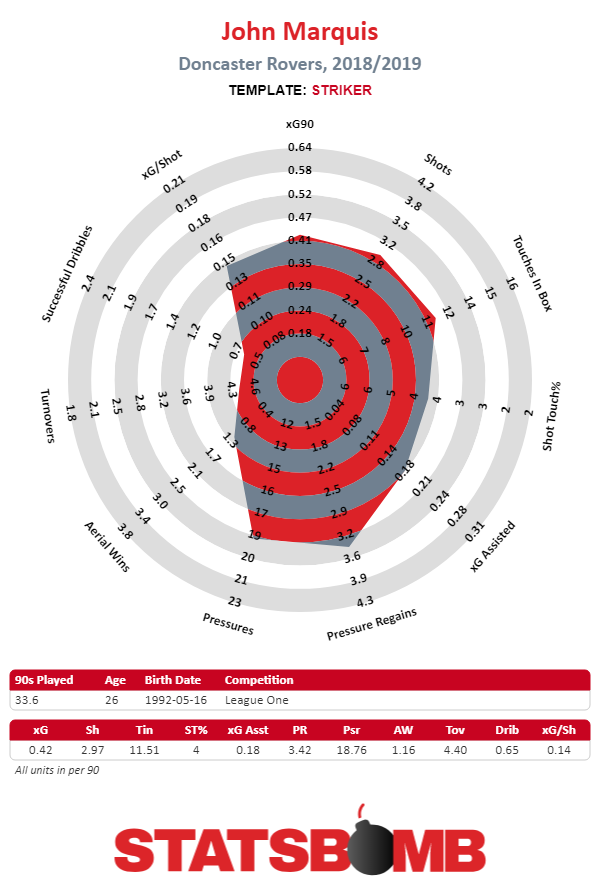

Given their early defensive struggles, it sure helped to have a striker who’s one of the best around at this level. In John Marquis they have a forward who’s comfortably the team’s biggest goal threat, but who also creates chances for others and even defends from the front as well.

Charlton:

Currently in 5th you have Charlton. In context, they’ve had a very impressive season so far after a cruel run of medium-term injuries to key players meant several academy players had to start games and there’s even been occasions where they’ve been unable to name a full subs bench.

Sadly though, their valiant run could be tailing off just as their injury problems ease. The break up of their 26-goal forward duo seems to be the main cause as Karlan Grant left strike partner Lyle Taylor and departed for the Premier League, sealing a cheap-looking £2million January move to Huddersfield.

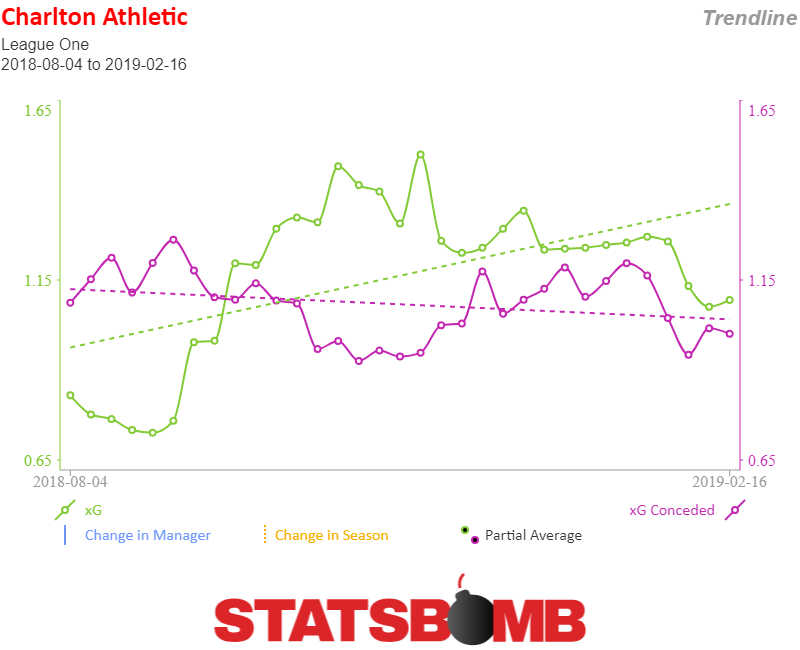

A recent three game spell immediately after Grant had left the club and whilst Taylor was serving a suspension highlighted the lack of depth Charlton have up front, with the team now looking overly reliant on Taylor to carry the goal burden he previously shared with Grant.

Charlton were already wringing every last point from their 0.14 expected goal difference per game, just about enough to put them in the “playoff contender” category in underlying numbers terms, but with Grant not being adequately replaced - Josh Parker arrived from relegation candidates Gillingham on a short-term deal - it’s fair to say Charlton won’t be the favourites heading into the playoffs if they hold onto their top six place.

Portsmouth:

At one stage, Portsmouth were comfortably champions elect after a stratospheric W14 D5 L1 record to open the season that took them six points clear at the top.

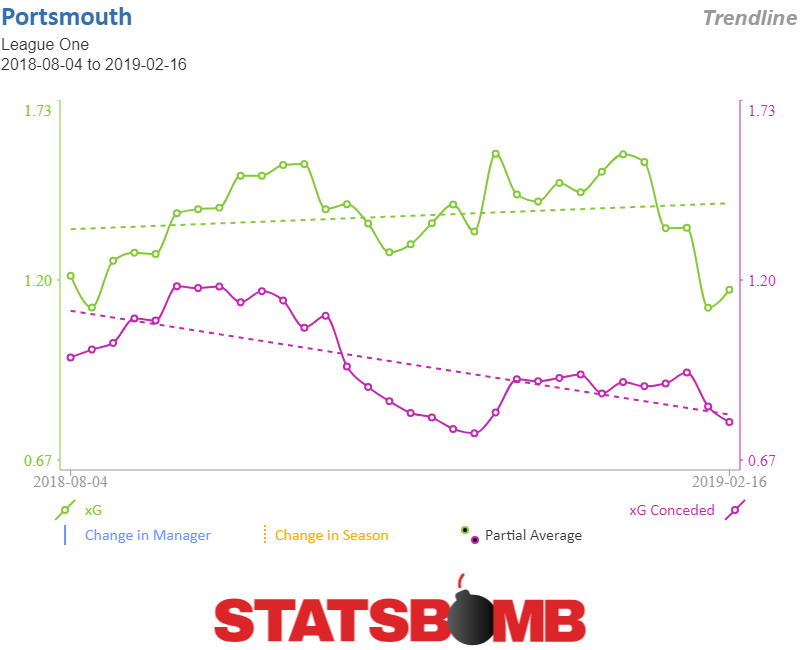

Portsmouth did (and do) actually have positive underlying numbers though and whilst a points return of that scale was always unlikely to be sustained, the drop off in the 14 games since has been unsettling for the neutral and outright horrifying for the fans, picking up just 15 points in that spell.

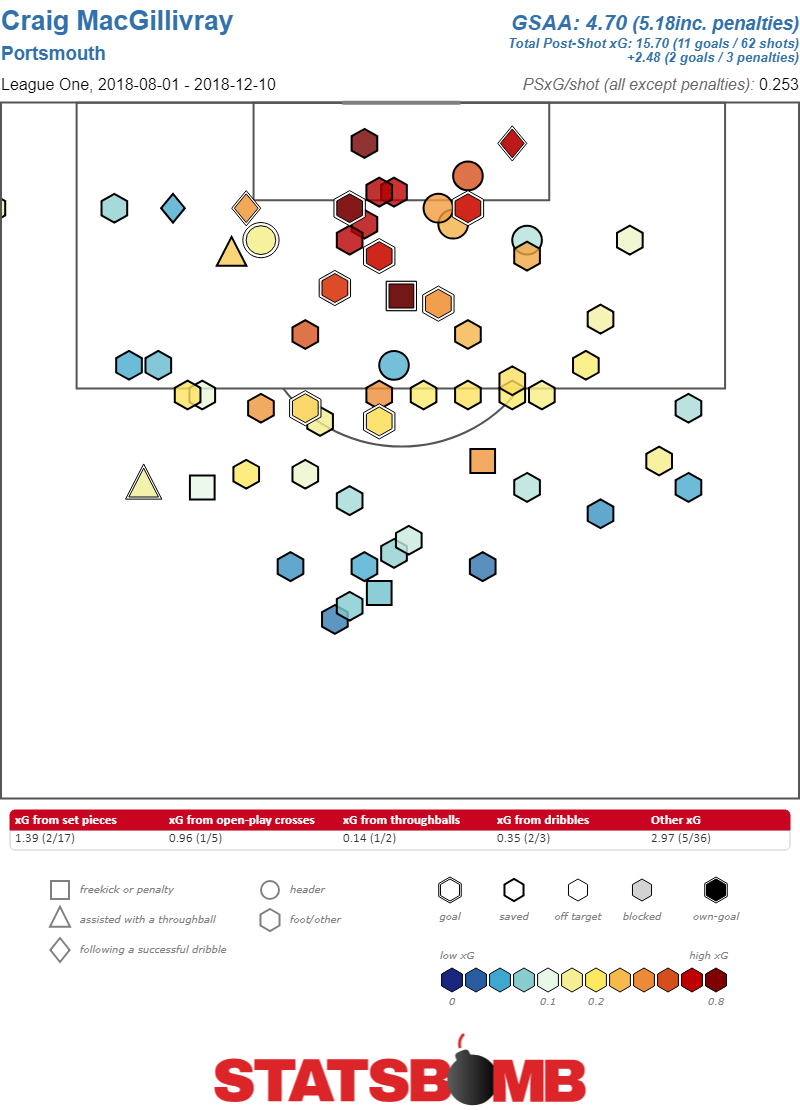

Having conceded just 15 goals in their hot start, goalkeeper Craig MacGillivray played a big part in their push to the top of the table. StatsBomb’s post-shot expected goals model believes he saved close to five goals more than Portsmouth were expected to concede from the shots their opponents were taking.

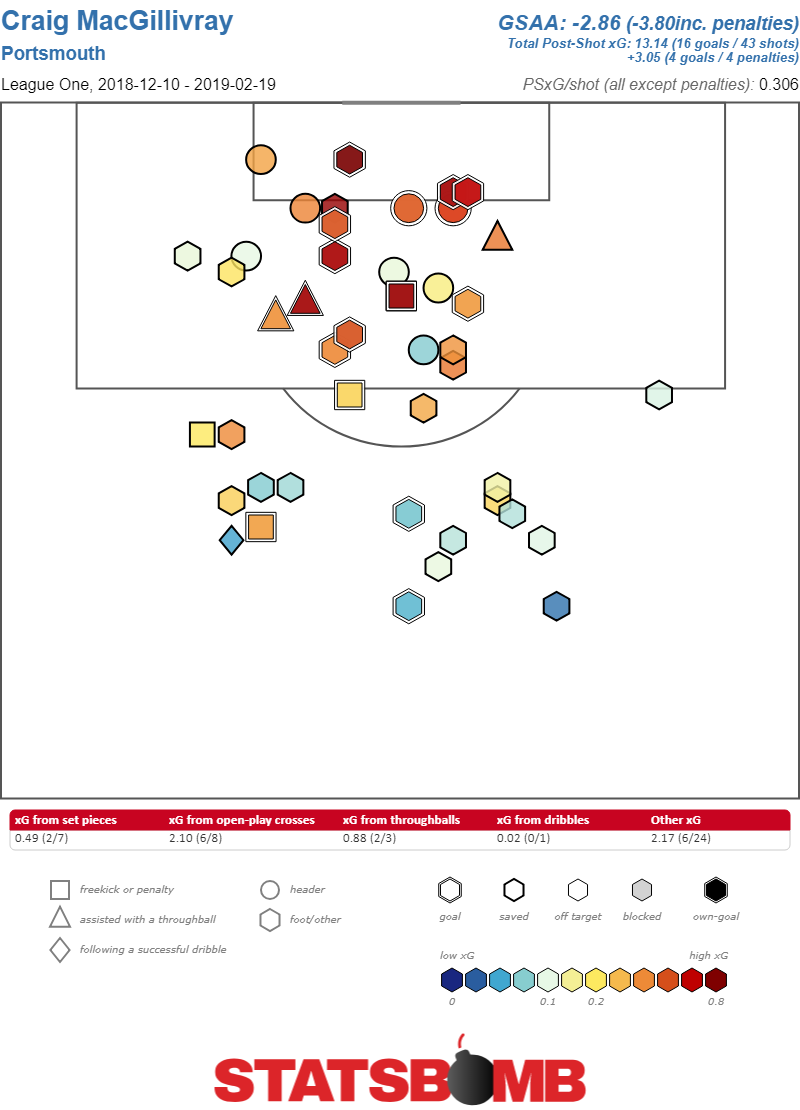

Unfortunately, he couldn’t sustain that form. In the 14 games where Portsmouth’s results have been more akin to that of a relegation struggler, MacGillivray has also been struggling and has now been saving below expectation.

Of course, it’s not all MacGillivray’s fault and in recent games there’s been a clearly visible decline in Portsmouth’s attacking output too.

With the top two looking increasingly out of reach, Portsmouth need to get their act together if they’re to recover their early season form and remain a serious contender for promotion.

Sunderland:

Recently of Match of the Day fame but nowadays seen on Netflix, Sunderland initially took very well to League One and they have some impressive performance indicators to back it up. The team has lost just two games so far and are also the only team to have scored in every single league game this season.

Trouble is, there are also some performance indicators that aren’t as impressive.

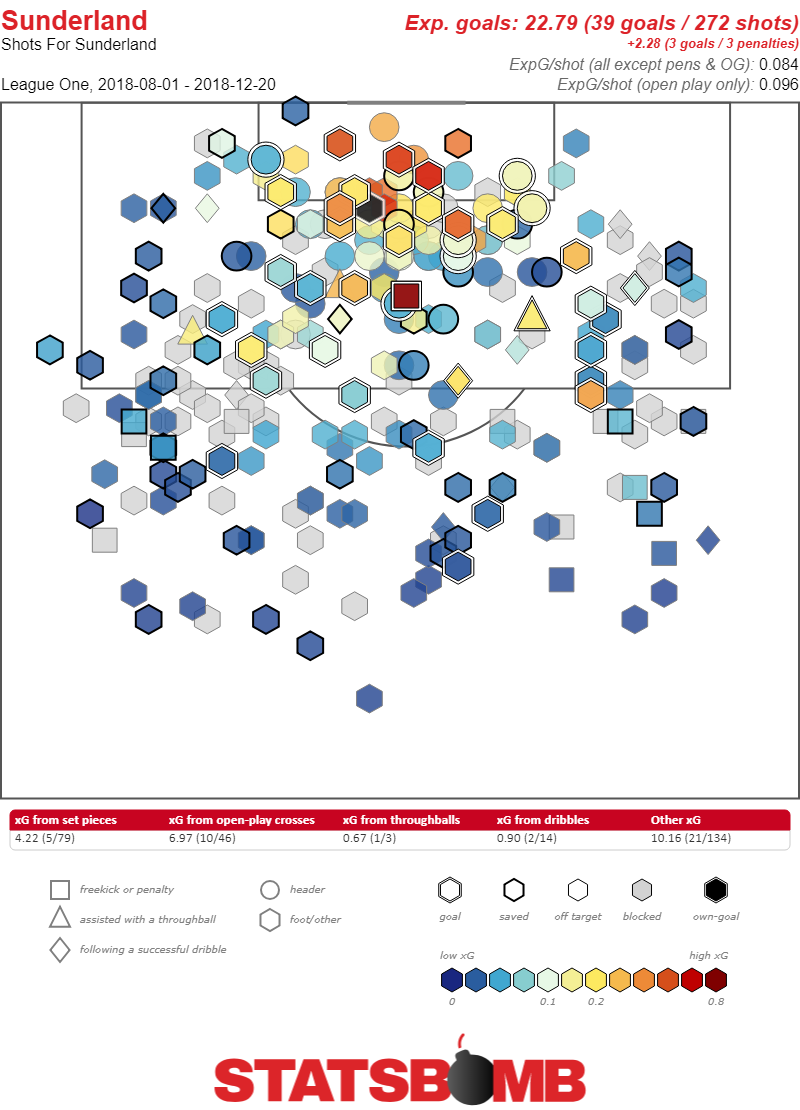

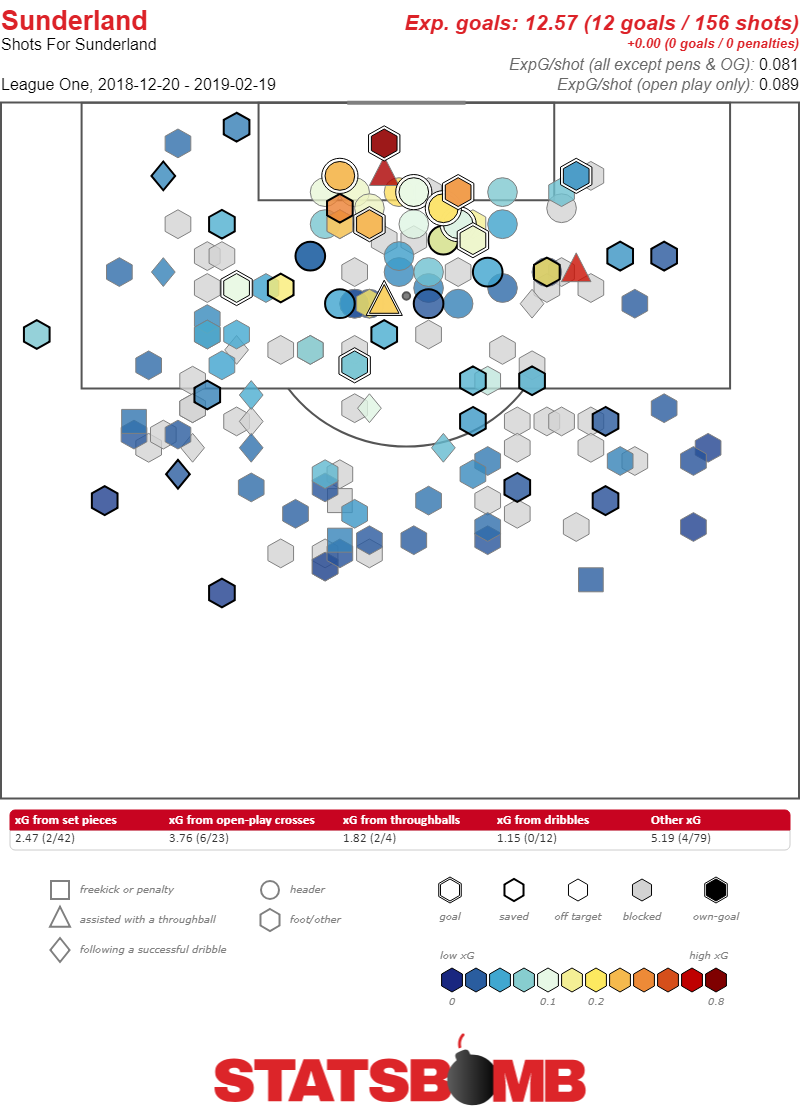

In the first 20 games of the season, Sunderland wildly overperformed their expected goals in attack, scoring at nearly double the rate they were expected to. While that made fans understandably chipper about their prospects of an instant return to the second tier, it also foreshadowed the problems that followed.

Since then, the Black Cats luck ran out, and they were recently on a barmy run of scoring exactly one goal in ten consecutive league games, a run that included six 1-1 draws and was only ended by a 2-2 draw.

As you can see below, performances haven’t necessarily gotten worse, it’s just that they’ve started scoring to expectation.

In truth, Sunderland hadn’t been playing like a side capable of automatic promotion all season but their last four games have all of a sudden seen them create a lot more chances than we’ve seen from them previously, ironically seeing them fail to get wins that they probably deserved.

For now, the Black Cats claws cling onto Barnsley’s coat tails. Who knows, maybe these shot maps will make it into Sunderland Till I Die Season Two...

Barnsley:

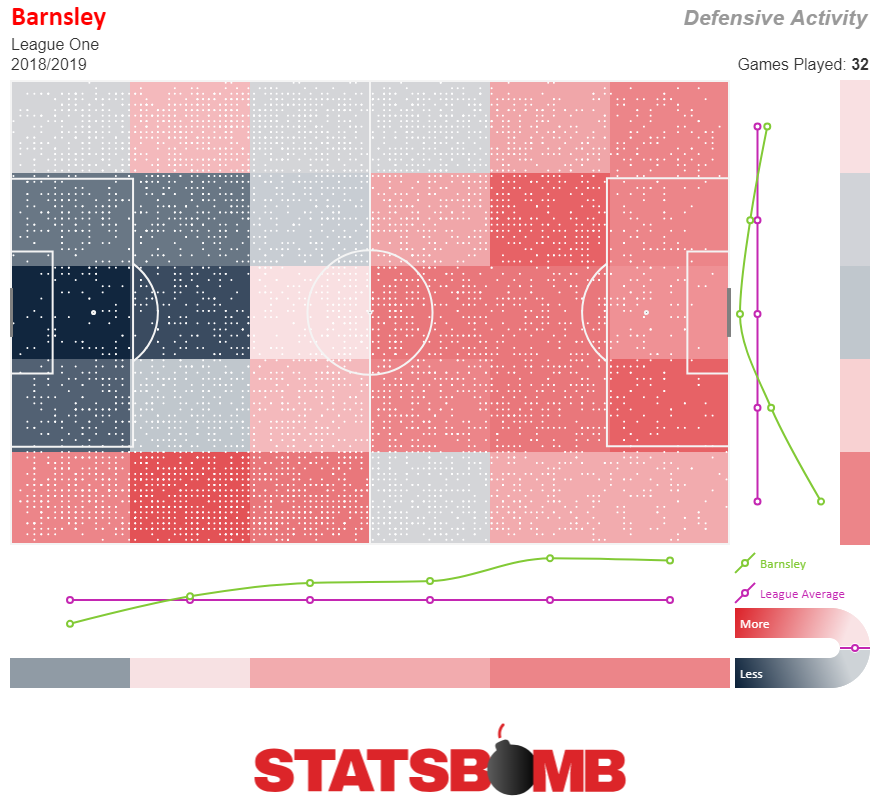

Occupying the first of two automatic promotion places, Barnsley look well set to return to the Championship at the first attempt. New boss Daniel Stendel has impressed since being imported from Germany, successfully implementing the counter-pressing style of play he promised when appointed.

To great effect too. By StatsBomb’s numbers, Barnsley are actually the best side in the league by expected goal difference and their brief stint outside of the play off places was followed up by a return of 31 points from the next 39 available.

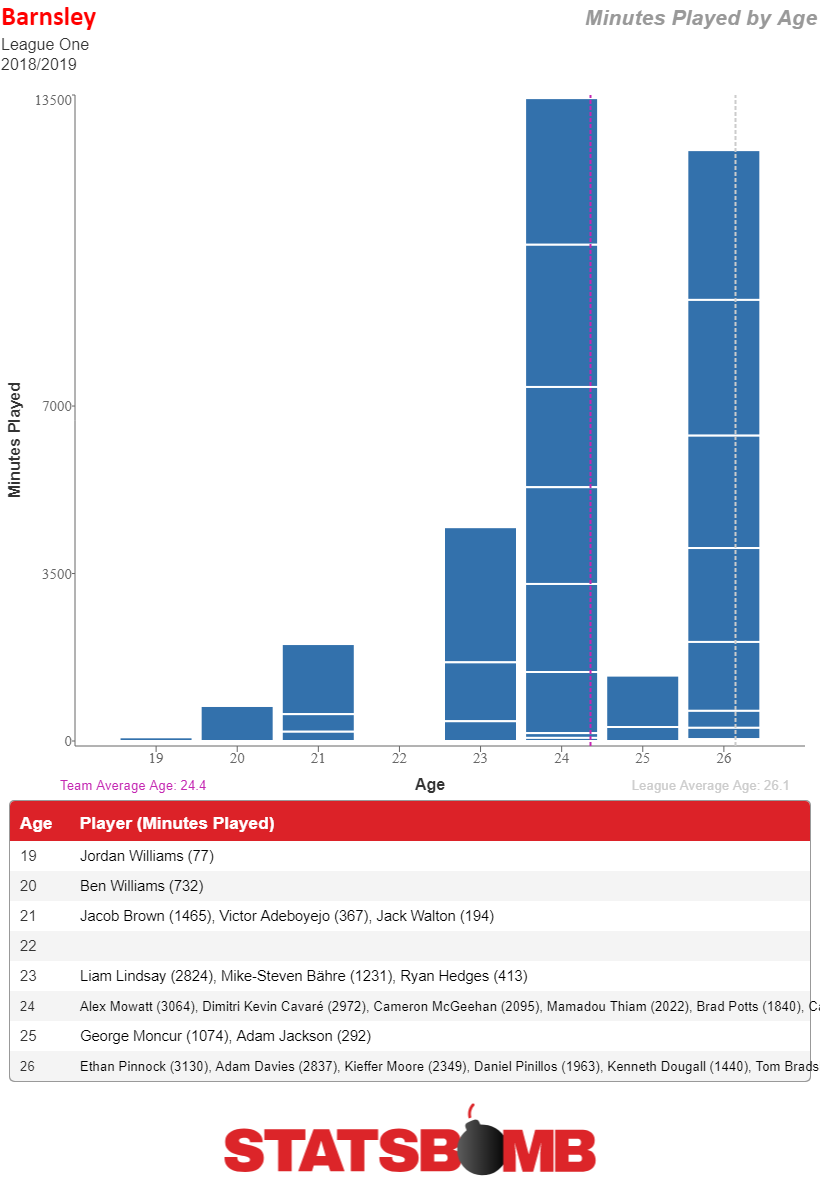

And all this without an experienced head. Someone who’s been there and done that. This is a side that hasn’t given a single minute of football to a player over 26 years of age this campaign.

Some may call it a smart strategy given what we know about the peak performance window in footballers, others may call it blatant ageism.

That’s a fight for another day. Barnsley find themselves in 2nd place and one of three remaining realistic title contenders. Luton have a not-insignificant points advantage over their rivals, but Barnsley’s top performance appears to be of a higher level than Luton’s based on the underlying numbers. So what do Barnsley have to overcome in the home straight?

Luton:

After a slightly tentative start to the season, Luton all of a sudden caught fire and have been a juggernaut ever since, knocking aside anyone who’s dared step into their path.

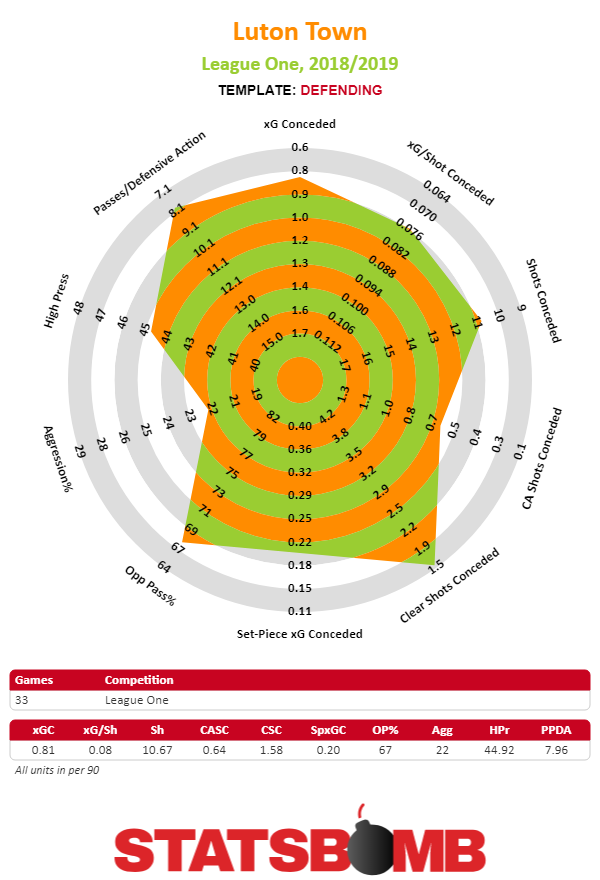

Their approach play has received a lot of praise this season – they are top scorers after all - but defensively they’ve been equally, if not more, impressive and they’ve conceded the joint-2nd fewest goals and, again bar one team, have kept the most clean sheets too.

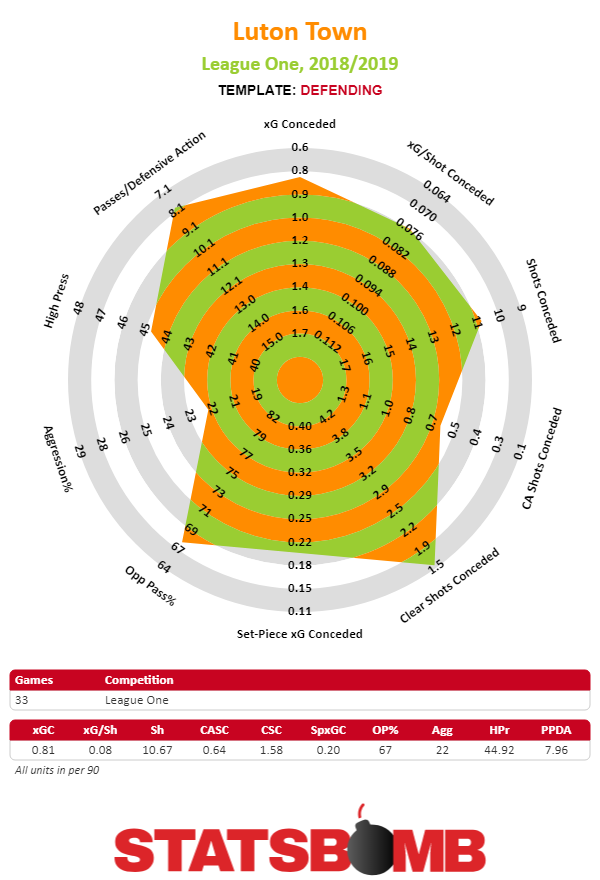

Their underlying numbers support this. By expected goals, Luton have the most solid defence in the league with just 0.81 xG conceded per game. Look at their defensive radar and you can gain a greater understanding of why that figure is so low.

Luton are just very difficult to create against. They rank 2nd in Shots Conceded per game but their xG per shot conceded is also 3rd best in the league, meaning not only are they great at limiting the quantity of shooting opportunities created against them, they’re successfully limiting the quality of those opportunities too.

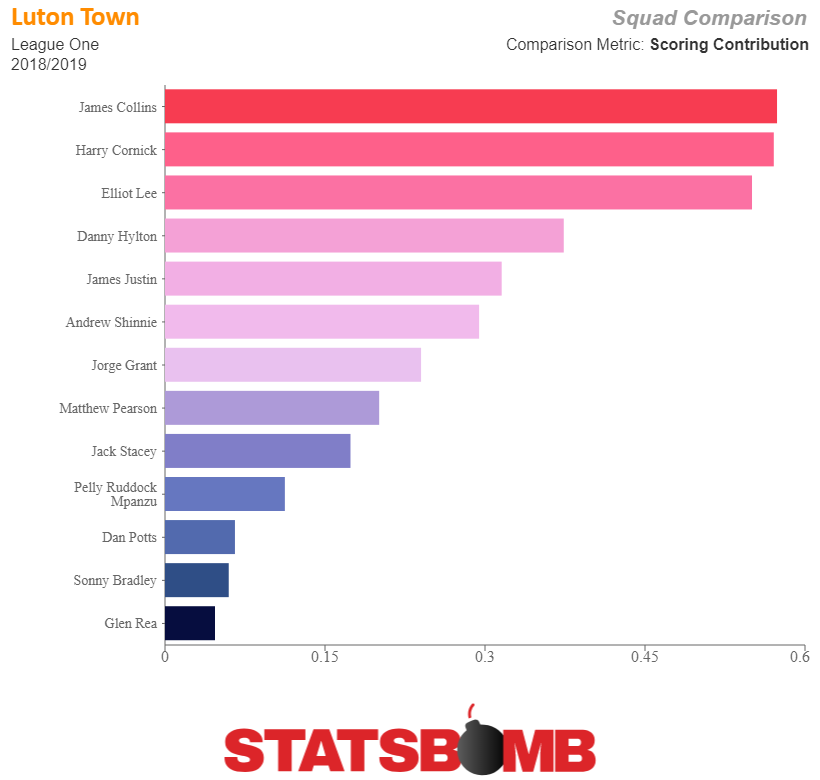

Another plus point is that whenever Luton have had an injury or suspension, the player coming into the side hasn’t hindered the quality of the side at all.

Scoring Contribution is a metric that measures non-penalty goals + assists, per 90 minutes played. Here’s how Luton’s players rank this season.

James Collins has been the only constant this season but the other attackers, Harry Cornick, Elliot Lee and Danny Hylton, have all had extended spells out of the side. As you can see, the output of all three has been very similar and the graph doesn’t even include Kazenga LuaLua (0.73 NPGoals + Assists per 90) as he doesn’t meet the minimum 600 minutes played threshold. Remove one of Luton’s limbs and they’ll just grow another one right before your eyes.

It’s Luton’s title to lose, but seemingly just two names remain on the list of challengers.

Replacing a Superstar: How Spurs (Eventually) Moved on From Gareth Bale

How do you replace a superstar footballer? Stars, by their very nature, are hard to replace; that’s why they’re stars. At any moment, there’s only a handful of Ballon d’Or-caliber players out there. Only some of them have their best years ahead of them. Even at a young age, these players tend to cluster at the world’s richest clubs. Only a subset of those clubs can afford to buy a superstar. Every time such a transaction occurs, the selling club must try to replace someone whose value stemmed from the absence of any comparable alternatives. This remains unfamiliar territory. The blockbuster transfer of a superstar, even in this era of TV deals and rising fees, remains a rarity. Good players are bought and sold in every window, but the transfer record has only been set seven times in this millenium. (The nominal fee for Hernan Crespo, the millennium's first record-setter, is about what Manchester City paid for Benjamin Mendy.) It’s still unusual for a club to lose a singular player and bring in the kind of money that allows for meaningful squad reconstruction. Spare a thought, then, for Tottenham Hotspur in the summer of 2013. The club had just sold Gareth Bale for a then-record €100.8 million. He really was that good, the closest thing to a one-man team and just entering his prime. Now what? In short, Spurs turned their Bale money and some spare cash into seven new signings, none of whom cost more than 30 percent of the Bale fee. Since nobody remembers what nine-figure fees meant in 2013, it’s helpful to think of what comparable fees netted in the Premier League that summer. Let’s remember some guys:

- Roberto Soldado and Erik Lamela, the two biggest purchases, each cost a bit less than Marouane Fellaini and a few million more than Stevan Jovetic and Alvaro Negredo.

- Paulinho’s transfer fee ranked between those paid by Chelsea for André Schurrle and Southampton for Dani Osvaldo.

- Christian Eriksen basically cost Spurs as much as Cardiff City spent on Gary Medel.

- Étienne Capoue’s acquisition was equivalent to Simon Mignolet’s move to Liverpool.

- Vlad Chriches cost Spurs about £500,000 more than Cardiff paid them for fellow center back Steven Caulker. His fee was tantamount to what Southampton spent on Dejan Lovren and Norwich spent on Ricky van Wolfswinkel.

- Nacer Chadli’s price matched what Liverpool spent on each of Tiago Ilori and Iago Aspas and Aston Villa spent on *squints at notes* Libor Kozák.

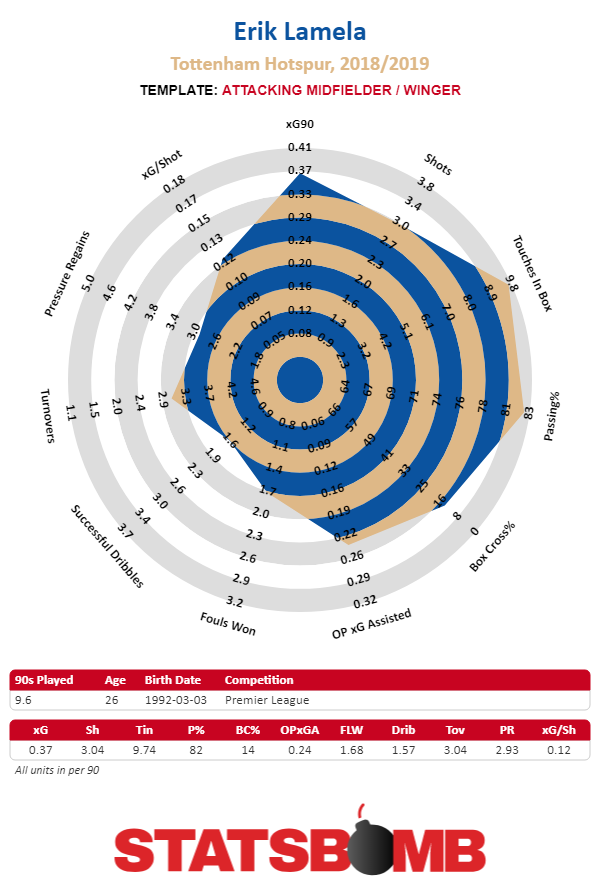

Nearly six years later, as various mega-clubs look set for serious rebuilds, it’s worth revisiting the strategies implicit in that list of names. Some of Spurs’ signings may have faded from memory or become less interesting, but their stories can help us better understand the value of capital-s Stars and the challenges of replacing them. /// Spurs immediately conceded that no available player could match Bale’s production (26 goals and 15 assists in 2012-13). The club sought to spread the responsibility between a nominal replacement (Lamela) and upgrades at other positions. Clubs often tell the press — or themselves — a version of this argument when replacing a crucial player. Spurs had tried it the year before, replacing Luka Modric and Rafael van der Vaart with the likes of Hugo Lloris, Mousa Dembélé, Jan Vertonghen, Gylfi Sigurdsson, Clint Dempsey, and Emmanuel Adebayor. Bale ironically became part of a similar argument last summer, when Real Madrid claimed its squad could replace Cristiano Ronaldo’s production. Players like 2013-vintage Gareth Bale are useful in large part because they concentrate so much production in one position. The remaining ten outfield players still contributed but they benefited from the attention paid to their star teammate. Jermain Defoe’s 2012-13 tally of 15 goals was useful to a team with Gareth Bale, but would be insufficient without him. For a team that had given more than 2,000 minutes to each of Aaron Lennon, Dempsey, Michael Dawson, Sigurdsson, Adebayor, Sandro, and Scott Parker in Bale’s final season, versions of this predicament existed at most outfield positions. Signing a superstar is expensive, but upgrading multiple positions to replace the lost production isn’t exactly cheap. Discussing players’ records in absolute terms obscured the cost of replacing all this production. Roberto Soldado arrived in London talking about scoring 20 goals. The number sounded impressive: 20 goals is a lot more than none and a lot more than what you or I could score. It is not, however, that much more than Defoe’s 15. A five-goal upgrade at striker was not going to make up for the very serious downgrade at Bale’s winger-ish position. What really mattered was the new signings production relative to the players they displaced. A club like Tottenham can buy a 10 goal player. Buying a ten-more-goals player is much harder — and Spurs needed more than one such player. It’s worth considering something approaching the best-case scenario for this strategy: Lamela contributes half of what Bale did, Soldado scores 20 goals, every signing starts and improves on an incumbent, nobody regresses. Forget for a second that most of these things did not happen. What reason was there to believe that buying two players from the part of the transfer market where title-chasing clubs purchased marginal starters and a handful of squad players would do the trick? This was akin to fielding Manchester City’s weakened team for cup ties for and expecting to compete for fourth. The players were not unusual flops. With the possible exception of Chiriches, who cost as much as Dejan Lovren (but also Ricky van Wolfswinkel), all of these signings performed about as well as comparable ones made by other clubs. They were improvements on an unimpressive squad, but that’s not all Spurs had hoped for. The strategy of spreading out production, as implemented by Spurs, could only have worked if multiple players improved in unexpected and unusual ways. In that respect, it was less of a strategy than it was an act of faith. Since the summer of 2013, teams have tended to follow the sale of a superstar with their own near-record purchases. Juventus spent the bulk of its Paul Pogba money on the bulk that is Gonzalo Higuain. Barcelona spent most of its Neymar money on Ousmane Dembélé and Coutinho. Those three replacements rank among the ten most expensive transfers in footballing history. Liverpool, in turn, spent the bulk of its Coutinho money on Virgil Van Dijk, who is also on that list. (These clubs were all richer than Spurs and had more talented squads when making these purchases.) Teams with policies of only buying young prospects have stuck to their guns, as Monaco and Borussia Dortmund did after selling Kylian Mbappé and Dembélé, respectively. Otherwise clubs have behaved as if buying one or two really good players — even if they’re at different positions — can better replace an outgoing superstar than a bevy of marginal upgrades. /// Time is rarely kind to transfers. The reality of a player — even a good one — can struggle to live up to the anticipation and techno-scored highlight clips that presaged their signing. Players age, get injured, and suddenly it’s easy to question the process that led to their acquisition. Tottenham’s post-Bale spending spree, on the other hand, has benefitted from the passage of time. What looked like a disaster in 2013 and 2014 has developed redeeming qualities. It might even be good. Christian Eriksen is the most obvious point in favour of that transfer window. Eriksen’s goodness is the least contentious part of this argument so it needn’t be belaboured. You can read StatsBomb supremo Ted Knutson’s praise of Eriksen from his first season with Spurs, which he recently told me “was SO LONG ago.” He’s still good, by the way: he leads the team in xG assisted per 90 minutes while also doing lots of central midfielder work like progressing the ball from deep and pressuring opponents. Once again, he was purchased at 21 in the same window Cardiff spent a comparable fee on 26-year-old Gary Medel. After six seasons at the club, he will either see out the rest of his prime or be sold for a princely sum. Spurs fans would obviously prefer the former, but either outcome would represent tremendous return on the original investment.  Then there’s Erik Lamela. Sometimes you buy a promising young winger — for argument’s sake, let’s call the selling club Roma — and they suddenly take the leap into Ballon d’Or contention. Other times you buy buy a promising young winger — once again let’s call the selling club Roma — and they turn out to be...pretty useful? Obviously you’d prefer the first outcome, but that doesn’t make the second one bad. Lamela has suffered from the expectation that he, of all the signings, would be Bale’s true successor and blossom into a goalscorer. That hasn’t really happened. But judged on his own term, as a tryhard who creates more than he scores while also fouling and pressing everyone in sight, he’s a good player. The caveat here is that Lamela’s per-90 statistics flatter a frequent substitute. Looking at Lamela’s unadjusted season totals, though, just drops him from being the second-best player in a variety of creative metrics to a decent fourth. (He still has the team’s second most throughballs, ranks fourth in expected goals, and a joint fourth with Dele Alli in scoring contribution.) The suboptimal outcome for a good, young player purchased for £27m, even in 2013, can still be quite good. Roberto Soldado, who showed some promise under Andre Villas Boas, was the most obvious flop. He was the oldest and most expensive player Spurs signed in 2013, never came close to scoring his promised 20 goals despite being in his prime, and lost much of his value in his two years with the club before being sold at a substantial loss. Negredo and Jovetic — the other strikers who came into the league for similar money that summer — weren’t great either, but Soldado was genuinely bad. There not being an obviously better option doesn’t change that fact. The other players at least took minutes away from some of the duds in the squad before being sold on at minor losses after a couple years. Nacer Chadli, the pick of that bunch, was a competent player who was sold on for basically the same nominal fee Spurs had spent in 2013. In the case of the more aged Paulinho, Spurs were bailed out by the existence of the Chinese Super League, but that’s what it’s there for. Chadli and Capoue went on to have useful careers lower down the Premier League table. Chiriches offers some depth at Napoli. Other than Paulinho, whose career is decidedly weird, these players appear to have found their levels. A buying club might want more Eriksen-style hits, but the “more is more” portion of the transfer list generally performed as you’d expect. Spurs, in other words, signed one of the midfield bargains of the decade in Eriksen, a promising young attacker who turned out fine, a dud of a striker, and some squad players who did squad player things before being sold on. One can credibly argue that they more than broke even on the summer’s business. And it was nowhere close to enough. Sixth place flattered Spurs in 2013-14. The new players were supposed to at least competently eat up minutes, but Nabil Bentaleb played more than 1,000 league minutes in that first post-Bale season. Both Bentaleb and Ryan Mason topped the 2,000 league minute mark in Mauricio Pochettino’s first season despite being, well, not very good at midfield things. You can, it turns out, get decent returns on your spending spree to replace a superstar and still end up much worse off. More than anything else, the lesson of Tottenham’s 2013 transfer travails may be that elite players — even the ones who bring in record fees — can be undervalued. Bale was known to make up for Tottenham’s talent deficit, but the extent of that deficit only became clear after he left. (This is likely less of an issue for other record sellers like Barcelona or Juventus, who have more talented squads.) Spurs made out okay with their Bale money, and it still took a major managerial upgrade, multiple good signings in subsequent windows, and the elevation of one of the league’s best strikers from the youth ranks for them to return to competitive relevance. A club can’t count on a grab bag of signings to replace the production of a superstar in the best of circumstances, but when those signings are purchased with a windfall that doesn’t reflect the lost star’s value the whole undertaking is basically impossible. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

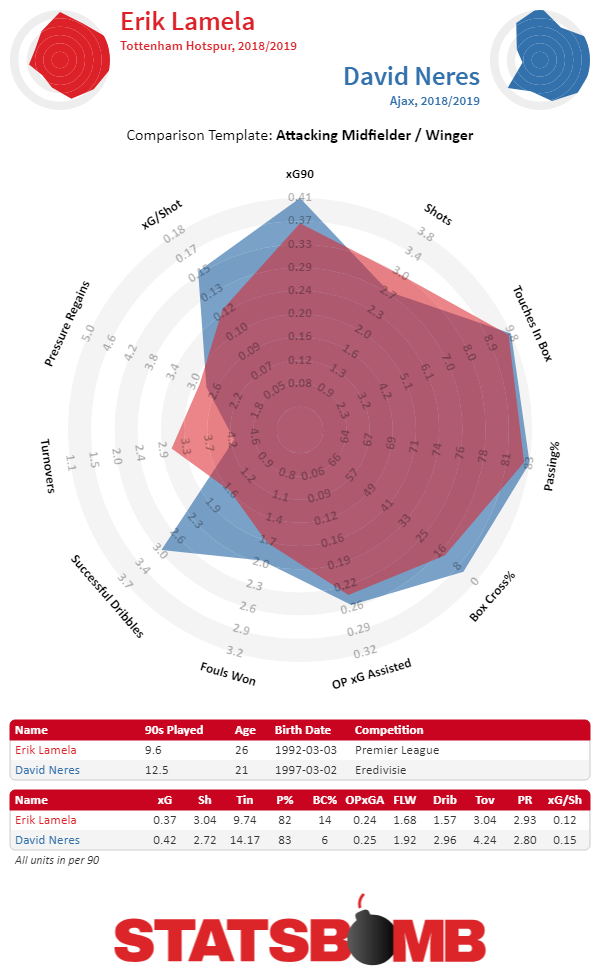

Then there’s Erik Lamela. Sometimes you buy a promising young winger — for argument’s sake, let’s call the selling club Roma — and they suddenly take the leap into Ballon d’Or contention. Other times you buy buy a promising young winger — once again let’s call the selling club Roma — and they turn out to be...pretty useful? Obviously you’d prefer the first outcome, but that doesn’t make the second one bad. Lamela has suffered from the expectation that he, of all the signings, would be Bale’s true successor and blossom into a goalscorer. That hasn’t really happened. But judged on his own term, as a tryhard who creates more than he scores while also fouling and pressing everyone in sight, he’s a good player. The caveat here is that Lamela’s per-90 statistics flatter a frequent substitute. Looking at Lamela’s unadjusted season totals, though, just drops him from being the second-best player in a variety of creative metrics to a decent fourth. (He still has the team’s second most throughballs, ranks fourth in expected goals, and a joint fourth with Dele Alli in scoring contribution.) The suboptimal outcome for a good, young player purchased for £27m, even in 2013, can still be quite good. Roberto Soldado, who showed some promise under Andre Villas Boas, was the most obvious flop. He was the oldest and most expensive player Spurs signed in 2013, never came close to scoring his promised 20 goals despite being in his prime, and lost much of his value in his two years with the club before being sold at a substantial loss. Negredo and Jovetic — the other strikers who came into the league for similar money that summer — weren’t great either, but Soldado was genuinely bad. There not being an obviously better option doesn’t change that fact. The other players at least took minutes away from some of the duds in the squad before being sold on at minor losses after a couple years. Nacer Chadli, the pick of that bunch, was a competent player who was sold on for basically the same nominal fee Spurs had spent in 2013. In the case of the more aged Paulinho, Spurs were bailed out by the existence of the Chinese Super League, but that’s what it’s there for. Chadli and Capoue went on to have useful careers lower down the Premier League table. Chiriches offers some depth at Napoli. Other than Paulinho, whose career is decidedly weird, these players appear to have found their levels. A buying club might want more Eriksen-style hits, but the “more is more” portion of the transfer list generally performed as you’d expect. Spurs, in other words, signed one of the midfield bargains of the decade in Eriksen, a promising young attacker who turned out fine, a dud of a striker, and some squad players who did squad player things before being sold on. One can credibly argue that they more than broke even on the summer’s business. And it was nowhere close to enough. Sixth place flattered Spurs in 2013-14. The new players were supposed to at least competently eat up minutes, but Nabil Bentaleb played more than 1,000 league minutes in that first post-Bale season. Both Bentaleb and Ryan Mason topped the 2,000 league minute mark in Mauricio Pochettino’s first season despite being, well, not very good at midfield things. You can, it turns out, get decent returns on your spending spree to replace a superstar and still end up much worse off. More than anything else, the lesson of Tottenham’s 2013 transfer travails may be that elite players — even the ones who bring in record fees — can be undervalued. Bale was known to make up for Tottenham’s talent deficit, but the extent of that deficit only became clear after he left. (This is likely less of an issue for other record sellers like Barcelona or Juventus, who have more talented squads.) Spurs made out okay with their Bale money, and it still took a major managerial upgrade, multiple good signings in subsequent windows, and the elevation of one of the league’s best strikers from the youth ranks for them to return to competitive relevance. A club can’t count on a grab bag of signings to replace the production of a superstar in the best of circumstances, but when those signings are purchased with a windfall that doesn’t reflect the lost star’s value the whole undertaking is basically impossible. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

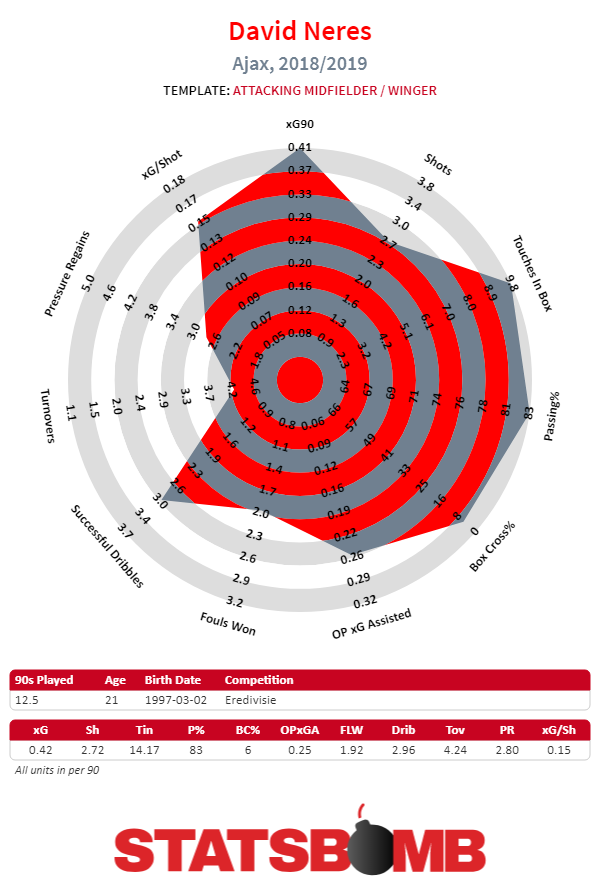

Reflections on David Neres: One Year Later

David Neres was one of the most conflicting prospects I’ve come across over the past couple of years. His ability to create goals for himself or others last season (25 combined goals an assists in less than 3000 Eredivisie minutes for a 20 year old was super impressive), along with credible shot contribution rates, made his productivity stand out in a very positive light. Even accounting for the Eredivisie being weird, and Ajax having a huge talent advantage within it, Neres passed the type of statistical benchmarks that you would hope for from a young attacker with flying colors.

But after watching film of Neres, I got scared by some of the flaws in his game, to the point that I rated Malcom as the better prospect t the time. I valued his elite athleticism and functional playmaking more than Neres’ elite coordination on-ball. Now it’s interesting to look back at that comparison 13 months later. That was probably close to the peak of where Malcom was as a young prospect, and he’s effectively lost an entire season of development at Barcelona. It’s tough to say whether this lost season will have a major effect on Malcom’s overall trajectory as a prospect, or if he’ll get a move to a club that he can get actual game time and this is just a bump on the road.

Neres hasn’t faced that same issue, despite Ajax's the acquisition of Dusan Tadic over the summer from Southampton cutting into available game time at the attacking positions. Instead of playing over 3000 minutes in both the Eredivisie and European competition like he did last season, Neres will probably end up playing closer to 2500 minutes, which is still not an insignificant number given that precocious young talents need game time to grow. Just like last season, he’s producing at a level that is comparable with almost anyone near his age.

What’s been interesting with Neres this season has been the degree of freedom with his positioning. He’s featured a lot in the left halfspace when play has progressed into the final third, where he's trying to strike up combination plays. From there, he can make runs into the box through either the wide left channel or by going through the middle of the box. If he's in the right halfspace, there's the chance for him to try and cut into the middle and either pass it to someone dangerous with his quality touch on passes or recycle the ball to a nearby teammate. While he wasn't quite restricted to only being an inverted winger from the right side last season, his freer role this season has probably helped in attempting to destabilize the opposition with his positioning.

One aspect of Neres's game that has become more apparent over the last year is his off-ball speed and the type of damage he can do with it. Neres’ ability to sense danger behind the backline is strong and he’s constantly on his toes looking to receive passes in space. His off-ball speed is elite, and given that many of his runs originate from the halfspace, it gives him a greater ability to be a threat for long passes. Given that he's playing on a squad that features high caliber passers, particularly Hakim Ziyech and his penchant for attempting high value passes with regularity, Neres is in the perfect environment to leverage his speed.

As it was last season, Neres's biggest appeal is that he has the type of coordination on-ball that you see from very few attacking talents. He's able to thread a pass between defenders and get the ball into dangerous spots with regularity. One can nitpick and say he's largely doing this against Eredivisie competition, but I'm pretty confident he'll be above average with his forward passing and overall chance creation even though the majority of them come from his left foot.

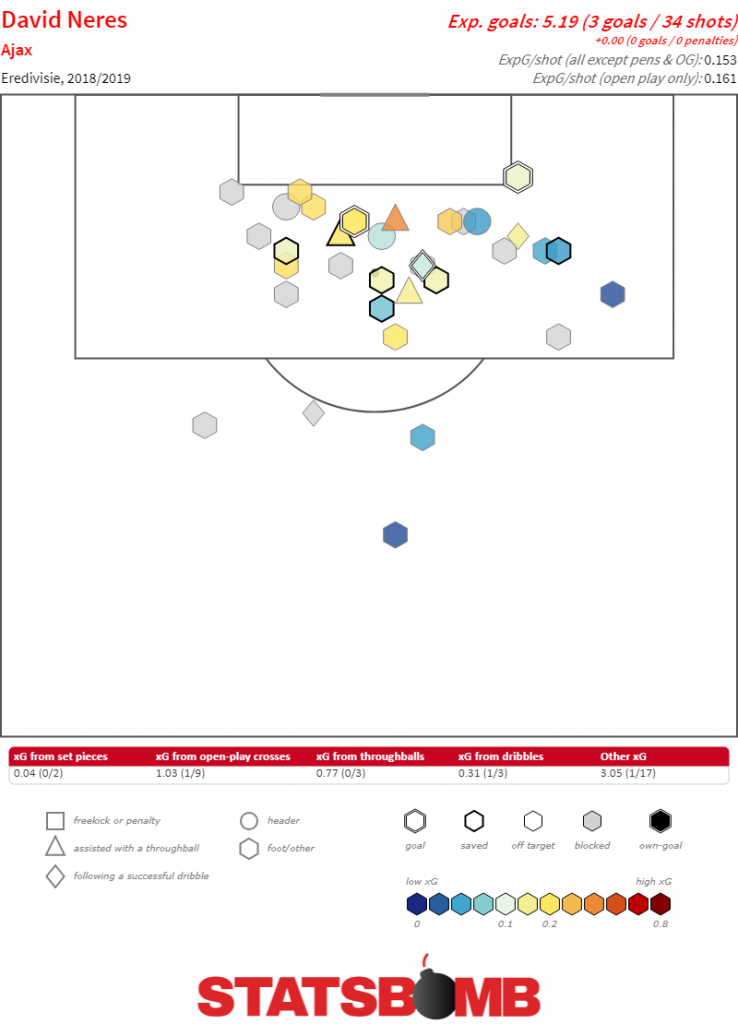

As it was last season, Neres's biggest appeal is that he has the type of coordination on-ball that you see from very few attacking talents. He's able to thread a pass between defenders and get the ball into dangerous spots with regularity. One can nitpick and say he's largely doing this against Eredivisie competition, but I'm pretty confident he'll be above average with his forward passing and overall chance creation even though the majority of them come from his left foot.  Neres is one of those young players who you don't have to worry about reigning in shot selection or wondering whether he'll waste possessions settling for low quality shots. He has about as clean a shot map as one could hope for from a young talent, and he provides value in that respect because it's not too often that you find 18-21 year old attackers who take shots at an average expected goal per shot value of 0.16. His judicious shot selection is a byproduct of a couple of things: he plays on one of the two major clubs in the Netherlands and that can skew numbers in a positive manner for players. Also, he is very hesitant to taking shots with his right foot so you end up cutting out potential shots from cutting inwards off the left wing, the type of shot that is a staple of wide attacking talents.

Neres is one of those young players who you don't have to worry about reigning in shot selection or wondering whether he'll waste possessions settling for low quality shots. He has about as clean a shot map as one could hope for from a young talent, and he provides value in that respect because it's not too often that you find 18-21 year old attackers who take shots at an average expected goal per shot value of 0.16. His judicious shot selection is a byproduct of a couple of things: he plays on one of the two major clubs in the Netherlands and that can skew numbers in a positive manner for players. Also, he is very hesitant to taking shots with his right foot so you end up cutting out potential shots from cutting inwards off the left wing, the type of shot that is a staple of wide attacking talents.  That reluctance to use his right foot is a key trait with Neres. It's not breaking ground to suggest that players are more likely to favor one foot than the other, and it's rare to find players like Ousmane Dembele who bring legitimate value by being both confident as a two-footed player and actually having the results to back it up (Justin Kluivert is an example of someone that has the confidence but more erratic results). But Neres is an extreme case and closer to being an outlier type in terms of dependence on his favored foot, even with the glimpses of decent right footed passes that you'll see from him. This isn't necessarily the worst thing in the world because he's got such a quality left foot to help compensate, but you'll see this flare up every now and then in a stark manner.

That reluctance to use his right foot is a key trait with Neres. It's not breaking ground to suggest that players are more likely to favor one foot than the other, and it's rare to find players like Ousmane Dembele who bring legitimate value by being both confident as a two-footed player and actually having the results to back it up (Justin Kluivert is an example of someone that has the confidence but more erratic results). But Neres is an extreme case and closer to being an outlier type in terms of dependence on his favored foot, even with the glimpses of decent right footed passes that you'll see from him. This isn't necessarily the worst thing in the world because he's got such a quality left foot to help compensate, but you'll see this flare up every now and then in a stark manner.  If there's one play that crystallizes both the good and bad with Neres as a young talent, it would be this one. The good is that there are a lot of players who would receive the ball in this position and then turn and take a speculative shot, which is a waste of a possession. The bad part is that there's an opportunity to carry the ball into the right side of the box for perhaps an individual shooting chance or a cutback for a teammate, the latter being a somewhat decent possibility because the team has a man advantage in the box. Someone who was a higher caliber athlete would've bet on himself to beat his man off the dribble and get to his spot. Given that he's going up against Eredivisie defenses, which aren't exactly renown for being stout, these instances help reinforce the notion that Neres will have trouble with his athleticism on-ball outside of the Ajax cocoon.

If there's one play that crystallizes both the good and bad with Neres as a young talent, it would be this one. The good is that there are a lot of players who would receive the ball in this position and then turn and take a speculative shot, which is a waste of a possession. The bad part is that there's an opportunity to carry the ball into the right side of the box for perhaps an individual shooting chance or a cutback for a teammate, the latter being a somewhat decent possibility because the team has a man advantage in the box. Someone who was a higher caliber athlete would've bet on himself to beat his man off the dribble and get to his spot. Given that he's going up against Eredivisie defenses, which aren't exactly renown for being stout, these instances help reinforce the notion that Neres will have trouble with his athleticism on-ball outside of the Ajax cocoon.  To a large extent, the conflicting feelings that I had a year ago with David Neres still persist when trying to think of his potential ceiling outcomes. You want to fall in love with him as a player because of parts of his skillset. He is an elite athlete off-ball and combines that with good timing for his runs, and this could be an x-factor for him being a huge success at his next club if utilized properly. I think he has good spatial awareness and is able to handle himself well during combination. Combine all that with very high level touch on his passing, and you've already covered a lot of what teams would want in a young wide player. And yet while he's generally good as a dribbler along with having very good shiftiness, another season has shown Neres to be overwhelmed at times when isolated against even mediocre defenders, along with being almost entirely dependent on his left foot. The good outweighs the bad with Neres and in a optimal environment, he could be a big time star, but clubs that are scouting him can't simply think of him as someone with such an overwhelming skillset that he'll be a unambiguous success in many situations. It's generally acknowledged that going to the right club is important for the developmental paths of young talents. With Neres, it's going to be especially important for him to find the perfect mix of squad and system fit given what he can and can't do. The good thing with Neres playing on Ajax and the team's success in Europe this season is that the worst club you could realistically expect for him to go to in the future would be ones who are on the outside looking in for Champions League spots (Arsenal being an example), but those clubs would have to ably replicate the setup Ajax have with their collective passing as a team to justify the high price tag that will come with a future Neres transfer. It's an interesting thought exercise to try and make player comparisons with Neres to visualize how he might fare outside of Ajax. Riyad Mahrez is an example of someone who like Neres has amazing technique with his left foot and broadly wouldn't be considered an overwhelming athlete, but along with having greater spontaneity in his dribbling, he's also better with right foot. Mahrez, during his absolute peak in 2015-16, was ruining defenders off the dribble and we've not seen that with Neres yet. Perhaps current day Erik Lamela (without the defensive value) is a better representation of how Neres is more likely to profile: being able to be an upper tier xG contributor without necessarily being an elite off the dribble threat (in the case of Lamela, that's more due to past injuries).

To a large extent, the conflicting feelings that I had a year ago with David Neres still persist when trying to think of his potential ceiling outcomes. You want to fall in love with him as a player because of parts of his skillset. He is an elite athlete off-ball and combines that with good timing for his runs, and this could be an x-factor for him being a huge success at his next club if utilized properly. I think he has good spatial awareness and is able to handle himself well during combination. Combine all that with very high level touch on his passing, and you've already covered a lot of what teams would want in a young wide player. And yet while he's generally good as a dribbler along with having very good shiftiness, another season has shown Neres to be overwhelmed at times when isolated against even mediocre defenders, along with being almost entirely dependent on his left foot. The good outweighs the bad with Neres and in a optimal environment, he could be a big time star, but clubs that are scouting him can't simply think of him as someone with such an overwhelming skillset that he'll be a unambiguous success in many situations. It's generally acknowledged that going to the right club is important for the developmental paths of young talents. With Neres, it's going to be especially important for him to find the perfect mix of squad and system fit given what he can and can't do. The good thing with Neres playing on Ajax and the team's success in Europe this season is that the worst club you could realistically expect for him to go to in the future would be ones who are on the outside looking in for Champions League spots (Arsenal being an example), but those clubs would have to ably replicate the setup Ajax have with their collective passing as a team to justify the high price tag that will come with a future Neres transfer. It's an interesting thought exercise to try and make player comparisons with Neres to visualize how he might fare outside of Ajax. Riyad Mahrez is an example of someone who like Neres has amazing technique with his left foot and broadly wouldn't be considered an overwhelming athlete, but along with having greater spontaneity in his dribbling, he's also better with right foot. Mahrez, during his absolute peak in 2015-16, was ruining defenders off the dribble and we've not seen that with Neres yet. Perhaps current day Erik Lamela (without the defensive value) is a better representation of how Neres is more likely to profile: being able to be an upper tier xG contributor without necessarily being an elite off the dribble threat (in the case of Lamela, that's more due to past injuries).  Whoever ends up being David Neres' next club after Ajax, whether that transfer occurs next summer or beyond that, will have to juggle all the factors mentioned previously along with even further extensive scouting before deciding on whether they're confident on him being a future star. Seeing as he's tied down to a contract until 2022 with Champions League money coming in this season for Ajax (not to mention a big fat Frenkie De Jong transfer fee), it would stand to reason that Neres' future fee will not come cheap. I am on the more skeptical end of the spectrum when it comes to Neres, and while I don't suspect he'll be a bust in a tougher league, I am more confident in Steven Bergwijn being a star talent outside the Eredivisie than I am with Neres. This could end up being entirely off the mark and Neres ends up being a stud, but he's the type of young Eredivisie talent where it's fair to be more skeptical of despite the gaudy statistical profile.

Whoever ends up being David Neres' next club after Ajax, whether that transfer occurs next summer or beyond that, will have to juggle all the factors mentioned previously along with even further extensive scouting before deciding on whether they're confident on him being a future star. Seeing as he's tied down to a contract until 2022 with Champions League money coming in this season for Ajax (not to mention a big fat Frenkie De Jong transfer fee), it would stand to reason that Neres' future fee will not come cheap. I am on the more skeptical end of the spectrum when it comes to Neres, and while I don't suspect he'll be a bust in a tougher league, I am more confident in Steven Bergwijn being a star talent outside the Eredivisie than I am with Neres. This could end up being entirely off the mark and Neres ends up being a stud, but he's the type of young Eredivisie talent where it's fair to be more skeptical of despite the gaudy statistical profile.

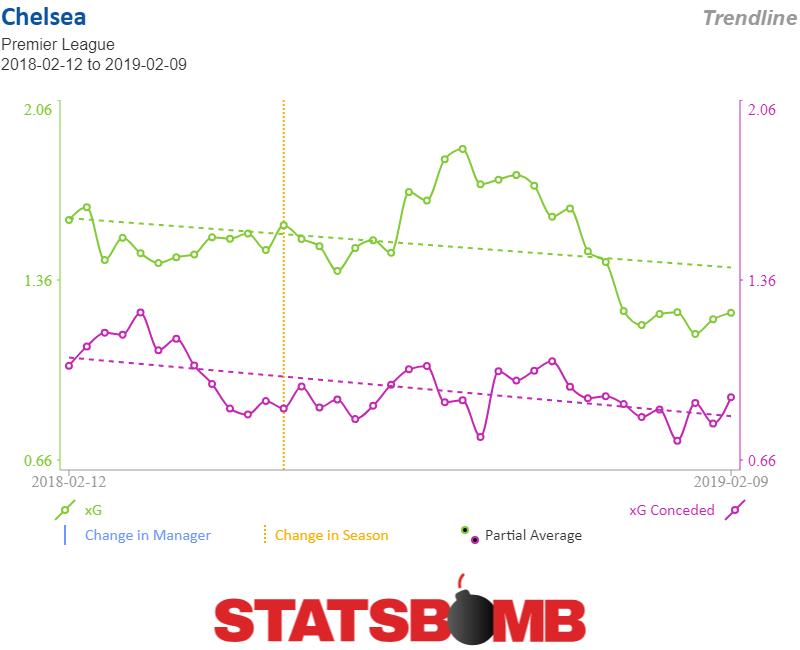

Sarri Must Show Progress Despite Chelsea's Imperfections

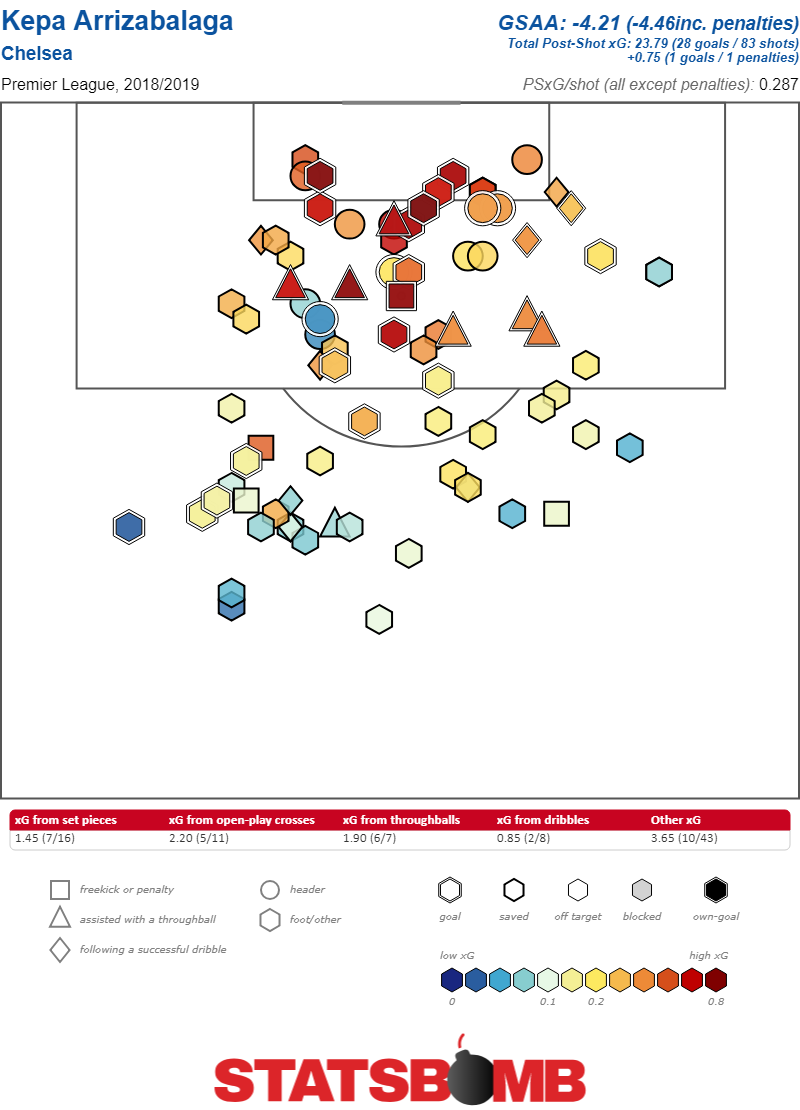

Chelsea are going the wrong direction. While the idea that they were in the title hunt might always have been fanciful, their performances, combined with their underlying numbers suggested they’d at least cruise to third while playing significantly better than the teams behind them. That hasn’t happened, and instead they find themselves in a fight for their top four lives. As Chelsea’s table position has deteriorated, so have their performances. It’s not simply that Chelsea’s results, which outstripped their level of play during the early months of the season, have returned to their underlying numbers, it’s that their underlying numbers have gotten worse.  The fact that there has been a noticeable decline in the team complicates most defenses of manager Maurizio Sarri. While it was always reasonable to expect a new manager to take some time to successfully introduce a new style of play, the fact that the team is actually getting worse as the season progresses, does not suggest a side that is slowly being brought along into a new style. This isn’t the story of a team that had some growing pains adapting from Antonio Conte’s primarily off ball approach to Sarri’s possession heavy attempt. It’s rather the story of a side that is not picking up his approach effectively at all. Accordingly, the defense of Sarri has shifted. Now, it’s that the squad is simply poorly constructed for Sarri, and that a club which was built to succeed under Antonio Conte could never become a side capable of playing Sarriball without a complete overhaul first (a task which has incidentally been made harder by a transfer ban handed down by FIFA, although one which could reasonably be delayed by appeal). There are three problems with this defense. The first is historical. Sarri took over Napoli in the summer of 2015. In his first season he finished second in Serie A with 82 points. That was a massive 19-point improvement over the team’s previous fifth place season. And it’s not like he took over from a similar manager. Rafa Benitez had previously been in charge, and while Rafa has many strengths, intricate possession based football is not exactly one of them. So, the last time Sarri took over a club, he took a team that had been struggling, playing a different brand of football and immediately improved them dramatically in his first season. And while it might not have been reasonable to expect the same degree of immediate success in England, expecting demonstrable progress is a pretty low bar. It’s one that Sarri has, so far, failed to clear. But, wait, I hear you cry, didn’t Napoli remake their roster for Sarri when he showed up? The answer to that is… kind of, and it brings us to the second problem with saying that it’s important to wait for Sarri to have his players in place. The current Chelsea squad already looks very very different from the one Conte deployed last season. At Napoli, in Sarri’s first summer, the team moved on from Gokhan Inler in midfield and brought in Allan from Udinese. Quite quickly he became an integral part of Sarri’s midfield. The team also brought in two players from his old club, Empoli; Elseid Hysaj who became a regular at fullback and Mirko Valdifiori a defensive midfielder who you’ve never heard of. Chelsea, similarly did a lot of work to overhaul this squad for Sarri last summer. In order to facilitate moving from a manager who was happy not to have the ball to one who’s possession hungry, Chelsea went out and got a new midfield. They not only bought Sarri Jorginho, the midfield pivot from his old side, but also Mateo Kovačić on loan from Real Madrid. Additionally, after they assented to Thibaut Courtois’ demands to move to Real Madrid, they brought in Kepa Arrizabalaga to replace him, emphasizing the need for a keeper who can play with his feet. One problem though, Kepa has not played particularly well with his hands, and is putting up a decidedly subpar shot stopping season.

The fact that there has been a noticeable decline in the team complicates most defenses of manager Maurizio Sarri. While it was always reasonable to expect a new manager to take some time to successfully introduce a new style of play, the fact that the team is actually getting worse as the season progresses, does not suggest a side that is slowly being brought along into a new style. This isn’t the story of a team that had some growing pains adapting from Antonio Conte’s primarily off ball approach to Sarri’s possession heavy attempt. It’s rather the story of a side that is not picking up his approach effectively at all. Accordingly, the defense of Sarri has shifted. Now, it’s that the squad is simply poorly constructed for Sarri, and that a club which was built to succeed under Antonio Conte could never become a side capable of playing Sarriball without a complete overhaul first (a task which has incidentally been made harder by a transfer ban handed down by FIFA, although one which could reasonably be delayed by appeal). There are three problems with this defense. The first is historical. Sarri took over Napoli in the summer of 2015. In his first season he finished second in Serie A with 82 points. That was a massive 19-point improvement over the team’s previous fifth place season. And it’s not like he took over from a similar manager. Rafa Benitez had previously been in charge, and while Rafa has many strengths, intricate possession based football is not exactly one of them. So, the last time Sarri took over a club, he took a team that had been struggling, playing a different brand of football and immediately improved them dramatically in his first season. And while it might not have been reasonable to expect the same degree of immediate success in England, expecting demonstrable progress is a pretty low bar. It’s one that Sarri has, so far, failed to clear. But, wait, I hear you cry, didn’t Napoli remake their roster for Sarri when he showed up? The answer to that is… kind of, and it brings us to the second problem with saying that it’s important to wait for Sarri to have his players in place. The current Chelsea squad already looks very very different from the one Conte deployed last season. At Napoli, in Sarri’s first summer, the team moved on from Gokhan Inler in midfield and brought in Allan from Udinese. Quite quickly he became an integral part of Sarri’s midfield. The team also brought in two players from his old club, Empoli; Elseid Hysaj who became a regular at fullback and Mirko Valdifiori a defensive midfielder who you’ve never heard of. Chelsea, similarly did a lot of work to overhaul this squad for Sarri last summer. In order to facilitate moving from a manager who was happy not to have the ball to one who’s possession hungry, Chelsea went out and got a new midfield. They not only bought Sarri Jorginho, the midfield pivot from his old side, but also Mateo Kovačić on loan from Real Madrid. Additionally, after they assented to Thibaut Courtois’ demands to move to Real Madrid, they brought in Kepa Arrizabalaga to replace him, emphasizing the need for a keeper who can play with his feet. One problem though, Kepa has not played particularly well with his hands, and is putting up a decidedly subpar shot stopping season.  Then, as Chelsea struggled, the team once again went out and brought in an old Sarri hand, Gonzalo Higuain, to lead the line. Over a third of Chelsea’s regular starting lineup is new this season. The problem is as much that the new players, the ones bought for Sarri, aren’t performing, as much as it is that the old guard are holding the team back. It’s reasonable for a manager to struggle with a squad that doesn’t fit his needs, it’s way less so to claim that completely remaking the midfield and bringing in his old star striker isn’t enough of a makeover to expect results. But maybe that really is the problem. Maybe no matter what Chelsea did, this team could not succeed given how their winger situation is currently constituted. It’s at least worth considering that Pedro and Willian are simply an impossible match for this system. They’re both past 30 and maybe those old dogs simply ain’t about to learn any new tricks. On top of that, maybe Hazard, great as he is, isn’t particularly suited to this system that needs him to play more as a goal scorer than leading the break in transition. Even this isn’t a great defense of Sarri. After all, Sarri keeps playing them. This is the final frustrating point. What would be the point of continuing to play two wingers who are over 30 if they are simply never going to be good enough in the system Sarri wants to play, when you not only have Callum Hudson-Odoi waiting in the wings, but another young replacement in Christian Pulisic coming this summer. Sure, maybe Hudson-Odoi isn’t ready, but in that case, it would make more sense to tweak the system to get the most out of the players on the pitch (in the understanding that they won’t still be there when better fitting players come in). Both playing Willian and Pedro, and not adjusting the system to get the most out of them, while leaving Hudson-Odoi on the bench is the worst of all possible worlds. The question at hand for Chelsea is, should (assuming they can delay a transfer ban via appeal) they continue to remake this squad in Sarri’s image? It’s a big risk to put all your eggs in the Sarri basket, especially with a transfer ban looming. Before committing to that project Chelsea need to take a long hard look at why his transition with this side has been so much rougher than his transition at Napoli was. It’s certainly true that the situation at Chelsea isn’t perfect for Sarri, but the situation at Napoli wasn’t either. There, he made do. Now he’s banging square pegs into round holes, shrugging and saying, I’ll be better when I have some round pegs. It might be true, but other managers out there are better at reshaping those pegs. The situation certainly hasn’t been perfect for Sarri at Chelsea, and maybe if it was we’d see him become a roaring success. But most managers don’t get to deal with perfect situations, and it’s now time to wonder exactly how much imperfect Sarri is capable of dealing with while still getting results. If Sarri can’t point to some sort of progress after replacing a third of his starters with new acquisitions, maybe Chelsea shouldn’t be so confident that he’ll be destined to succeed if they just replace the rest of them. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

Then, as Chelsea struggled, the team once again went out and brought in an old Sarri hand, Gonzalo Higuain, to lead the line. Over a third of Chelsea’s regular starting lineup is new this season. The problem is as much that the new players, the ones bought for Sarri, aren’t performing, as much as it is that the old guard are holding the team back. It’s reasonable for a manager to struggle with a squad that doesn’t fit his needs, it’s way less so to claim that completely remaking the midfield and bringing in his old star striker isn’t enough of a makeover to expect results. But maybe that really is the problem. Maybe no matter what Chelsea did, this team could not succeed given how their winger situation is currently constituted. It’s at least worth considering that Pedro and Willian are simply an impossible match for this system. They’re both past 30 and maybe those old dogs simply ain’t about to learn any new tricks. On top of that, maybe Hazard, great as he is, isn’t particularly suited to this system that needs him to play more as a goal scorer than leading the break in transition. Even this isn’t a great defense of Sarri. After all, Sarri keeps playing them. This is the final frustrating point. What would be the point of continuing to play two wingers who are over 30 if they are simply never going to be good enough in the system Sarri wants to play, when you not only have Callum Hudson-Odoi waiting in the wings, but another young replacement in Christian Pulisic coming this summer. Sure, maybe Hudson-Odoi isn’t ready, but in that case, it would make more sense to tweak the system to get the most out of the players on the pitch (in the understanding that they won’t still be there when better fitting players come in). Both playing Willian and Pedro, and not adjusting the system to get the most out of them, while leaving Hudson-Odoi on the bench is the worst of all possible worlds. The question at hand for Chelsea is, should (assuming they can delay a transfer ban via appeal) they continue to remake this squad in Sarri’s image? It’s a big risk to put all your eggs in the Sarri basket, especially with a transfer ban looming. Before committing to that project Chelsea need to take a long hard look at why his transition with this side has been so much rougher than his transition at Napoli was. It’s certainly true that the situation at Chelsea isn’t perfect for Sarri, but the situation at Napoli wasn’t either. There, he made do. Now he’s banging square pegs into round holes, shrugging and saying, I’ll be better when I have some round pegs. It might be true, but other managers out there are better at reshaping those pegs. The situation certainly hasn’t been perfect for Sarri at Chelsea, and maybe if it was we’d see him become a roaring success. But most managers don’t get to deal with perfect situations, and it’s now time to wonder exactly how much imperfect Sarri is capable of dealing with while still getting results. If Sarri can’t point to some sort of progress after replacing a third of his starters with new acquisitions, maybe Chelsea shouldn’t be so confident that he’ll be destined to succeed if they just replace the rest of them. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

Can Barcelona Find a Potential Jordi Alba Replacement?

Barcelona have got themselves into a bit of pickle with Jordi Alba’s contract. By failing to put an adequate succession line for the left-back in place, they have backed themselves into a corner whereby they could well end up spending significant money to extend for five years the contract of a player who turns 30 in March.

Alba’s current deal expires at end of the 2019-20 season, and he and his representatives are reported to be seeking a contract that brings him up to the wage bracket of those other mainstays of recent triumphs, Gerard Pique and Sergio Busquets. Barcelona’s opening offer was rejected at first sight. No further progress has been made.

His position has been strengthened by an excellent campaign that has yielded a career-high 13 assists in all competitions and seen him do pretty much all the things you’d want of a attack-minded full-back on a title-challenging team.

The key question is how long he can continue to produce that kind of output in one of the most physically demanding positions in the game. Even if he is able to do so for a couple more seasons, would it really be a smart move for a club who is already presiding over the highest wage bill in Europe, with the highest wages to turnover ratio of any of the richest clubs, to commit to a big-money five-year deal?

Without an experienced direct replacement in the current squad - central defenders, right-backs and 19-year-old, B-team left-back Juan Miranda have all filled in - their options look fairly limited. Poor results in Alba’s absence this season suggest that regardless of whether they eventually reach an agreement with him, they will still need another left-back next season to avoid the drop-off in performances when he is rested or otherwise unavailable.

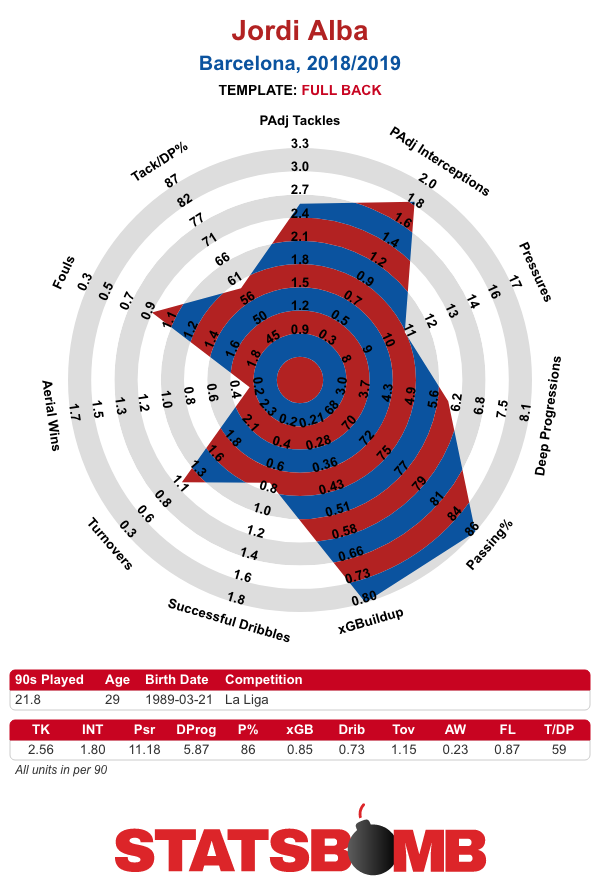

The club’s scouting department presumably already have a list of names they’ve been monitoring, but here we are going to use some of our data to identify players with similar statistical profiles and attacking output to Alba.

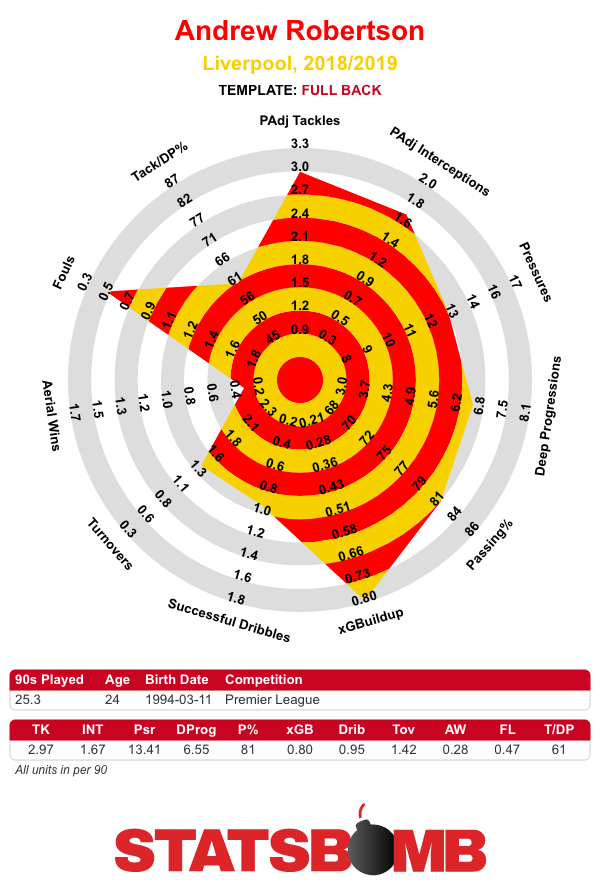

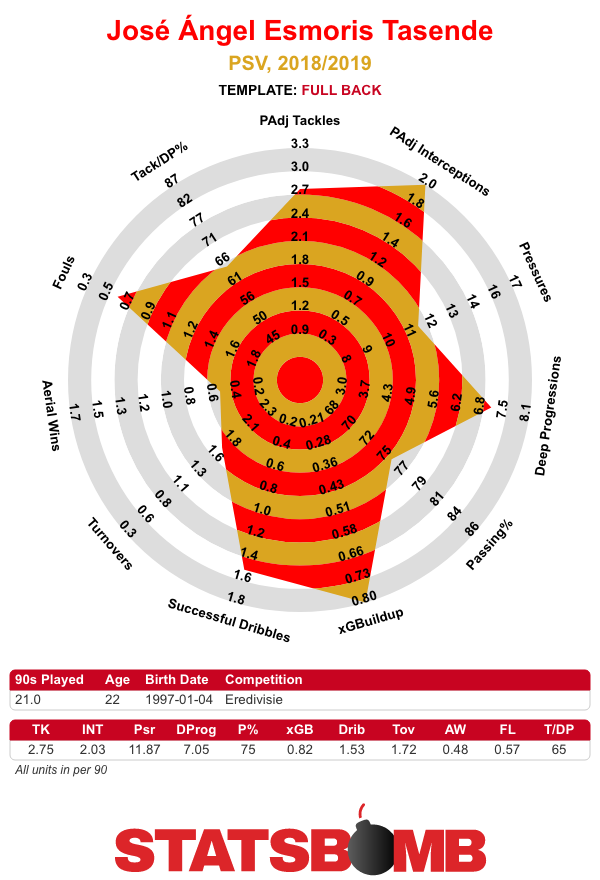

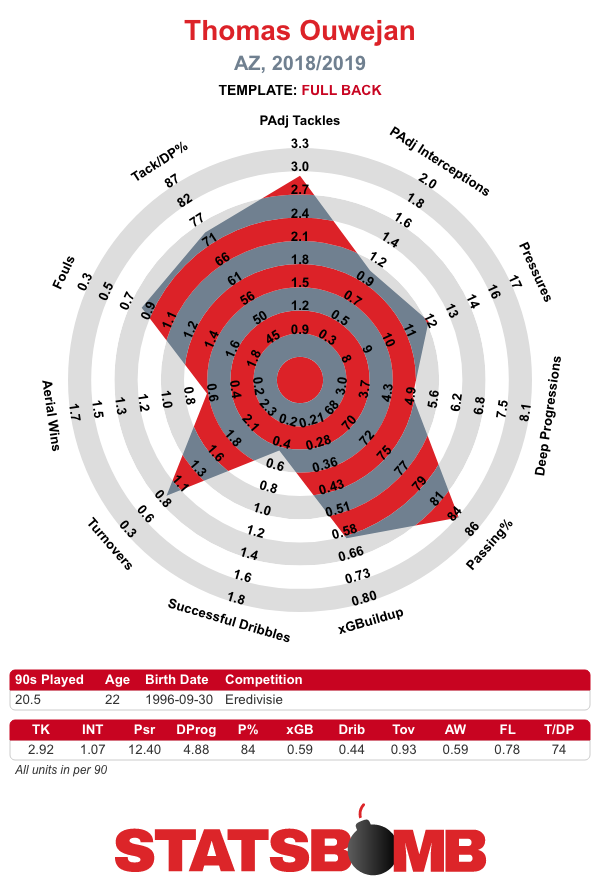

Using the StatsBomb IQ similarity tool, here are the players who have played the majority of their minutes at left-back or left wing-back, aged 25 or under at the end of this season, in the top five European leagues, Portugal and the Netherlands, over the last couple of seasons, who have 80% or higher similarity to Alba, ranked from the best match downwards: Andrew Robertson (2018-19), Thomas Ouwejan, Luke Shaw, Benjamin Mendy, Kenneth Paal, Ludwig Angustinsson, Alejandro Grimaldo, Angeliño and Andrew Robertson (2017-18).

That provides a good starting point, and we’ll return to one of those names later on. But we need to refine that list further by seeking out players capable of providing a similar assist output to Alba. His seven assists in league play are buttressed by an open play xG assisted per 90 figure of 0.22 -- fifth amongst all left-backs in the top-five leagues this season.

Here are the players who, using the same age, positional and league criteria as before, have provided 0.15 or more open play xG assisted per 90 in either of the last two seasons: Angeliño, Andrew Robertson, Alfonso Pedraza, Benjamin Mendy, Konstantinos Tsimikas, Robin Gosens and Thomas Ouwejan. That leaves four players who tripped both of the filters: Andrew Robertson, Angeliño, Benjamin Mendy and Thomas Ouwejan. Mendy’s injury record rules him out as a viable option, leaving three to investigate further: Robertson, Angeliño and Ouwejan.

Andrew Robertson

By this point, the virtues of Andrew Robertson hardly require further enumeration. At Liverpool, the player whose spiky attacking output at Hull drew interest from bigger clubs has developed into one of the most complete players in his position in Europe.

The 24-year-old was the only player to meet the similarity score requirement in each of the two most recent seasons, while his open play xG assisted of 0.20 per 90 this season also ranks him towards the top of that list. Like Alba, he has provided seven assists in league play. It would certainly not be an inexpensive operation, but Barcelona would be getting the prime years of an ideal, like-for-like replacement for Alba, with experience at the top end of both domestic and European competition.

Angeliño

It should perhaps come as no surprise that Angeliño appears amongst the results given that he is a player who has been on Barcelona’s radar for some time. They were interested in him when he was a youth prospect at Deportivo La Coruña, before he moved to Manchester City, and they also considered him last summer, before his transfer to PSV Eindhoven. “He is a very good footballer,” a club source told El País in November. “He’s got speed, dribbling ability, and he gets forward well.” That much is evident in both his open play xG assisted figure of 0.23 per 90 and his overall statistical profile.

The 22-year-old has the sort of skill set that would be well-suited to Barcelona. He is able to get forward to the byline on the overlap or the dribble to deliver into the area. Having done so, he usually gets his head up to try and pick out a specific option.

And he is also able to find teammates with direct balls down the line or cuter passes infield. He ranks third for PSV in deep progressions, with just over seven per 90.

Unsurprisingly, his numbers were significantly worse in the Champions League. PSV were outclassed in a group alongside Barcelona, Tottenham Hotspur and Inter Milan, and his attributes were not as well-matched to the open, back-and-forth encounters that those matches became. He is not a long-striding, powerful full-back capable of regularly carrying the ball forward into attacking territory from deeper areas. But neither is that necessarily what Barcelona would be looking for. The primary point of concern would be Angeliño’s defensive capabilities. Particularly in relatively set defensive situations, he gives the impression of constantly being a step or two behind, reacting rather than anticipating. He also has a bad habit of setting himself a bit too square to his opponents, making it hard for him to adjust and prevent them getting past.

While his defensive work could be expected to improve with age, his weaknesses there may initially be even more noticeable against a higher average level of attacker, such as he would find in La Liga. But overall, with a further campaign of good numbers behind him, Angeliño represents a safer bet for Barcelona now than he would have been last summer. There would be a learning curve, for sure, but he looks as good a potential long-term successor for Alba as there is in the current market.

Thomas Ouwejan

Thomas Ouwejan triggered both of the filters, but did so in different seasons. His similarity score was based on his 2017-18 campaign, while his 0.15 open play xG assisted per 90 this time around saw him just sneak in under that criteria. His radar for this season at AZ Alkmaar displays a slightly different profile and one that squares with watching him in action.

The 22-year-old is generally a sensible, stay-on-his-feet defender, who concentrates on making himself difficult to get past. Going forward, he is a simple but efficient passer, and mainly progresses into advanced positions with overlapping runs past the skilled wide forward Oussama Idrissi. He is taller and more upright in his gait that Alba (and Robertson and Angeliño) and consequently less supple in changing direction in both offensive and defensive situations. He doesn’t possess a decisive change of pace. While Ouwejan is certainly someone that top-half clubs in the bigger leagues should be looking at, he isn’t someone who looks capable of replacing what Alba provides to Barcelona.

Other Options

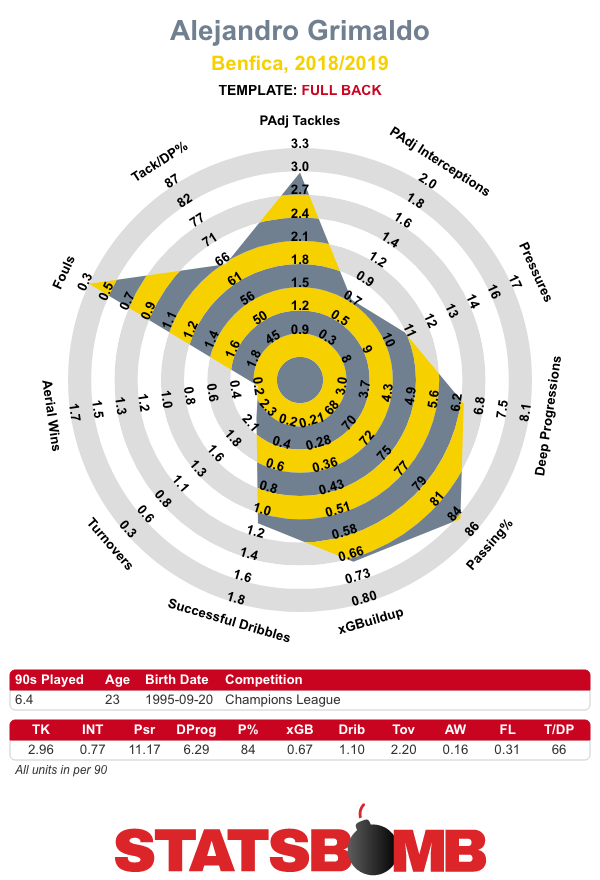

If Barcelona are able to extend Alba for a lesser time period or even just retain him as a starter through the final season of his current contract, there are a couple of potentially cheaper options who would represent solid backups with room for further development. Alejandro Grimaldo featured on the similarity filter, but failed to make the cut on his attacking output, with just 0.06 open play xG assisted per 90 in his outings for Benfica in the Portuguese league. There are, though, a couple of things in his favour: firstly, he came through the Barcelona youth system and they are due a percentage of any future sale, which could be leveraged for a good deal; secondly, in an admittedly smaller sample, his numbers in the Champions League this season were very solid. The 23-year-old again profiled similarly to Alba (80%), while his open play xG assisted figure of 0.13 per 90 was much closer to the 0.15 per 90 cutoff we put in place.

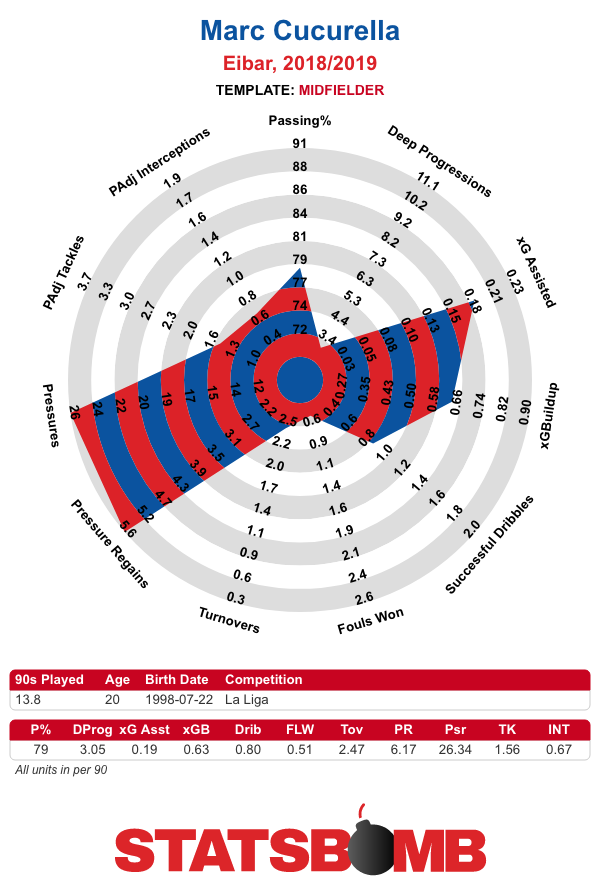

Barcelona also currently have Marc Cucurella out on loan at Eibar. Largely a left-back in the Barcelona youth system, at Eibar he has mainly been employed on the left of midfield. An assist and standout performance in a 3-0 win over Real Madrid in November was the high point of a solid yet infrequently as spectacular campaign.

The 20-year-old has, though, showed himself capable of competing at a top-flight level and is unlikely struggle to find a place for himself in a Primera Division squad next season. What is much less certain is whether he has shown enough to convince Barcelona of his suitability for a place in theirs.

Attacking Contributions: Markov Models for Football

Messi or Ronaldo? Kroos or Modric? Mbappe or Neymar? Every football fan loves to argue over who they think is a better player. Depending on where your loyalties lie, arguments can range from simple statistics; like the number of goals they’ve scored or the trophies they have won, to advanced metrics like expected goal values from ghosting. To the layman football fan, the former argument is almost certainly more digestible. But for the rest of us, we often want a metric that’s more objective, more extendable, and more rigorous, while still being able to understand it and explain it to your counterpart to assert your football dominance.

The evolution of football analytics - how we got to non-shot expected goals models.

Every football analytics nerd understands the (slow) evolution of football statistics. The story begins with football’s notorious and frustratingly difficult objective of scoring goals, the historic hindrance for American spectating. Analyzing goals scored and goals conceded appeased few and people quickly realized the value of shot volume for depicting a team’s performance and ability. The obvious pitfall in comparing shot volume was the quality of a shot can vary drastically. This led to everyone under the sun defining their own expected goals (xG) model to objectify chance quality and aggregate goal likelihood as a better metric for attacking production. xG is now omnipresent in football analytics as a tool for attackers’ and teams’ performance. Most recently in the sports analytics community, people have extended the concept of expected goals to allocate ball progression contributions throughout a team’s possession of the ball.