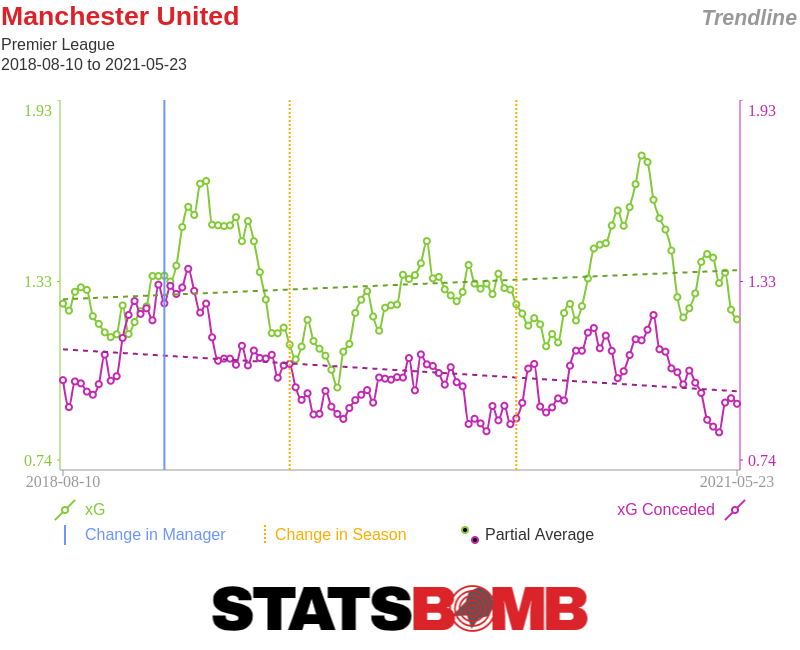

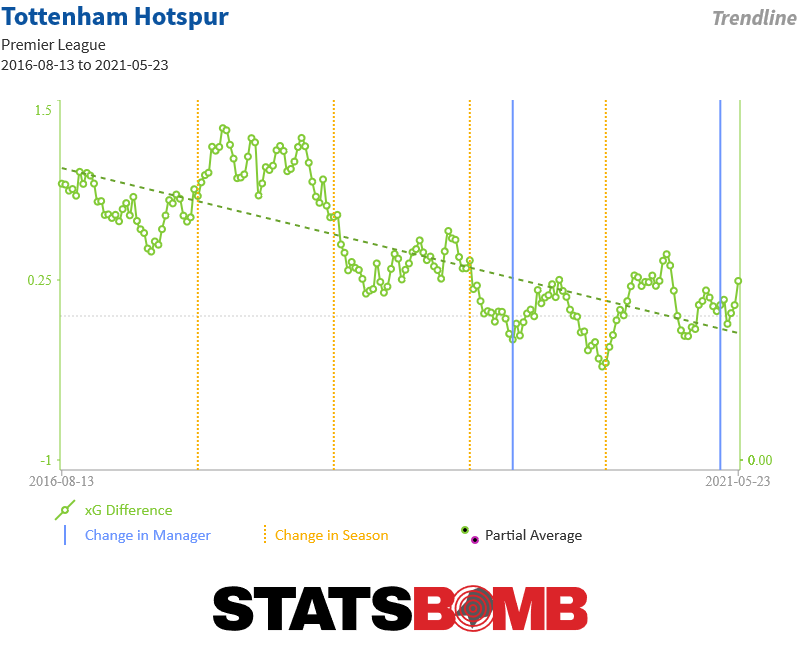

It’s nearly two years since the StatsBomb site was relaunched in its current form, and I’ve been writing about the Premier League here for most of that time. With no football until God knows when, now is the best time to take stock and look at what we’ve learnt over the past couple of seasons. Expected Goals catch up to you... eventually It’s May 2018 and Manchester United are flying high-ish. A second place finish with 81 points is comfortably the best they’ve done in the post-Sir Alex Ferguson era, even if Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City look a long way off. The usual rumblings with Jose Mourinho are going on in the background, but with the right signings there’s no reason why this positive trajectory can’t continue, right? Unfortunately for Man Utd, the rot had already set in some time ago. The 2017/18 season saw them concede nearly 14 goals fewer than expected, while scoring an extra 10. The data suggested the most likely outcome was a decline in results, and guess what? Well, you’re reading a football analytics website in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic, so you probably know Mourinho was sacked by Christmas. It’s true that the side did decline in other ways, but the xG overperformance coming to an end was paramount. United actually conceded 3.5 more goals than expected in 2018/19, and though they scored an additional 4.4, we’re not talking about hugely significant finishing gains.  The same story came true for Mauricio Pochettino at Tottenham, although it took its time. If we look at the xG trendlines, it’s pretty startling how much Spurs start to decline in both attack and defence around spring 2018 and never recover.

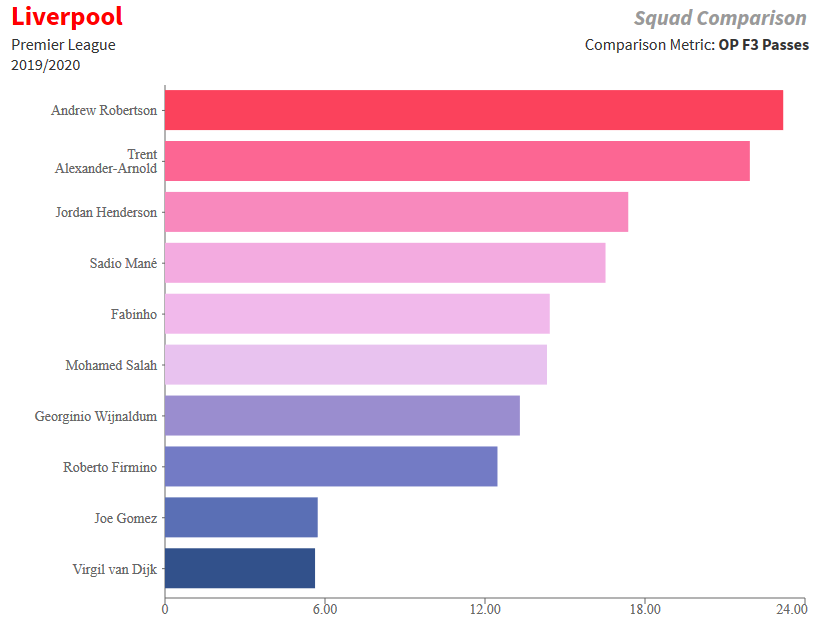

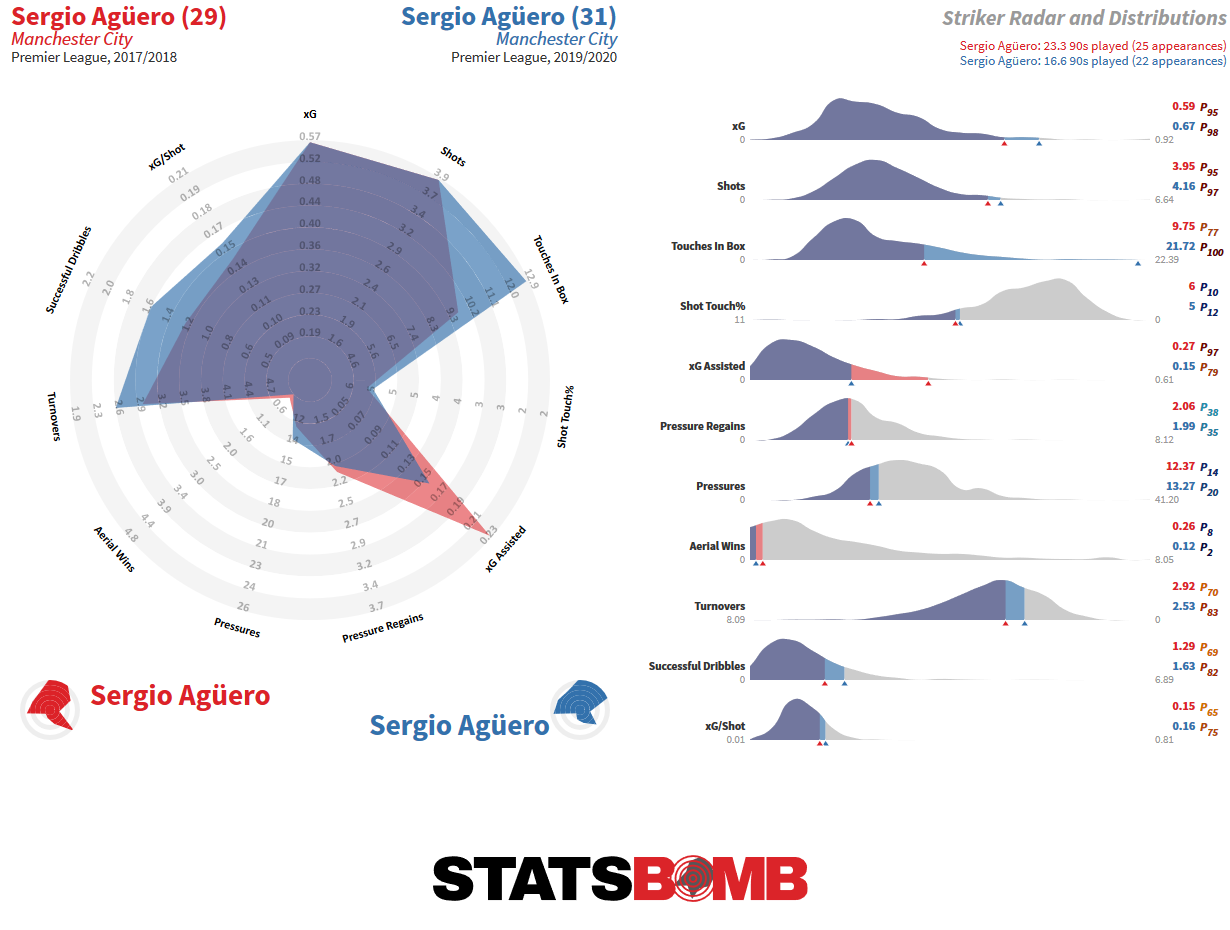

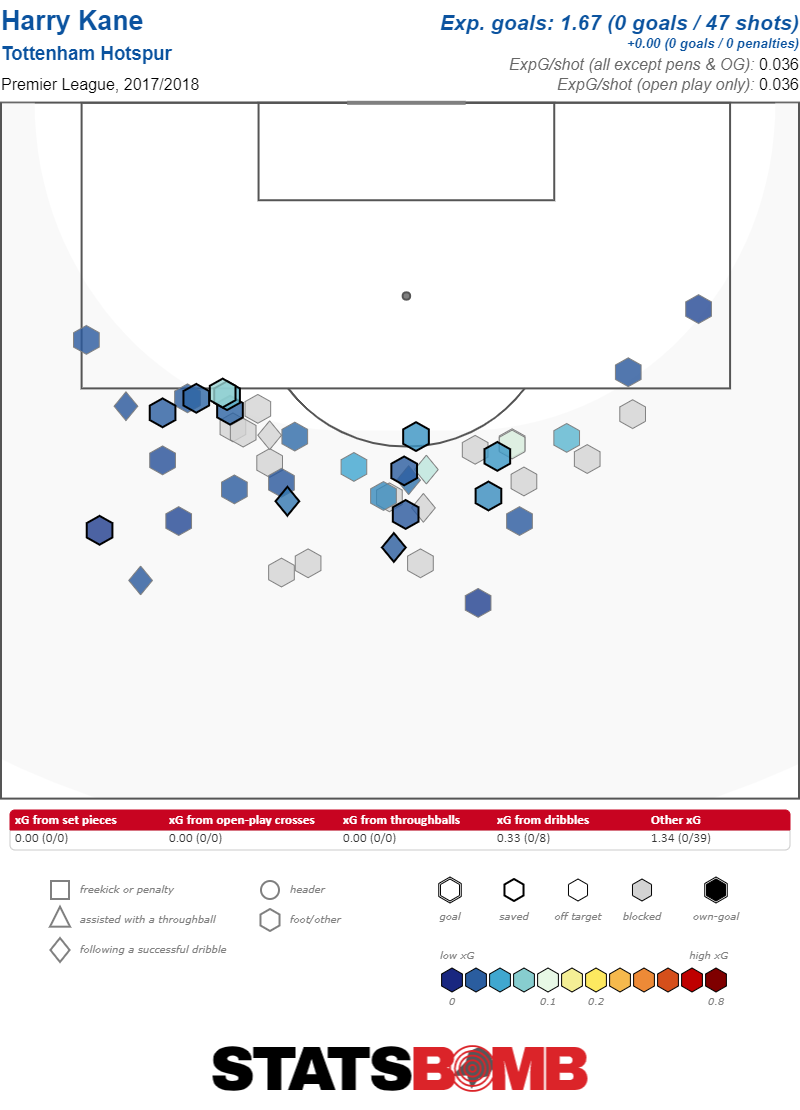

The same story came true for Mauricio Pochettino at Tottenham, although it took its time. If we look at the xG trendlines, it’s pretty startling how much Spurs start to decline in both attack and defence around spring 2018 and never recover.  Spurs spent calendar year 2018 beating xG at both ends of the pitch, scoring nearly 17 extra goals and conceding almost 9 fewer than expected. A number of reasons were put forward to explain this: good goalkeeping from Hugo Lloris, elite finishing from the likes of Harry Kane and Son Heung-min, or even Pochettino’s tactics. It’s entirely possible that some of those factors were in play, but ultimately you can’t outrun xG forever. Different ways to get it forward Liverpool are 25 points clear at the top of the Premier League table. If we ever play the rest of the season out, it will be a coronation process for the Reds. The biggest stats story with Liverpool is in how they move the ball forward. Looking at the graph below, we can see the players most used in moving the ball both into the final third (x-axis) and then into the box (y-axis) are the two full backs, Trent Alexander-Arnold and Andrew Robertson.

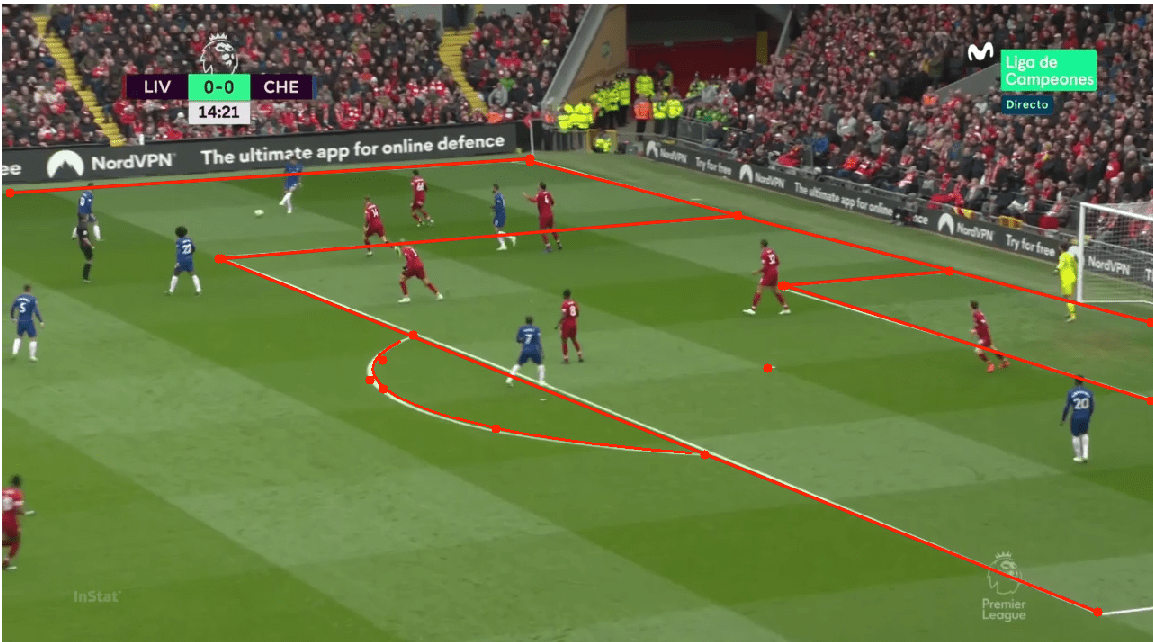

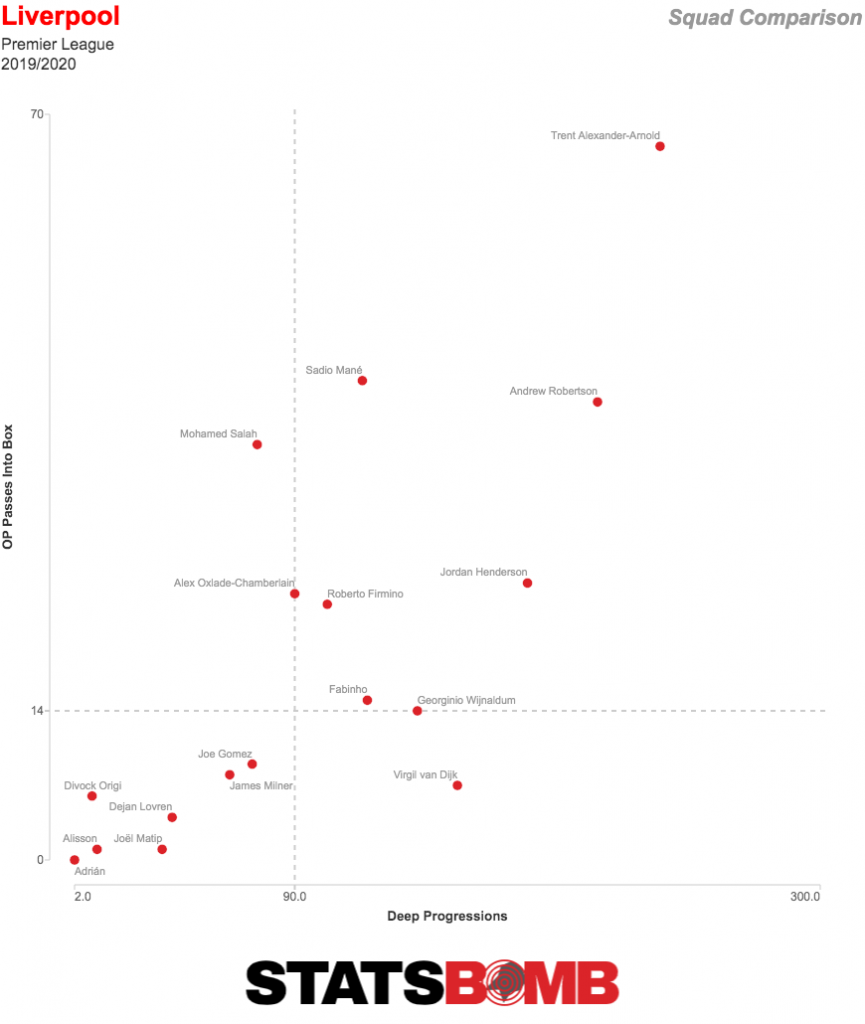

Spurs spent calendar year 2018 beating xG at both ends of the pitch, scoring nearly 17 extra goals and conceding almost 9 fewer than expected. A number of reasons were put forward to explain this: good goalkeeping from Hugo Lloris, elite finishing from the likes of Harry Kane and Son Heung-min, or even Pochettino’s tactics. It’s entirely possible that some of those factors were in play, but ultimately you can’t outrun xG forever. Different ways to get it forward Liverpool are 25 points clear at the top of the Premier League table. If we ever play the rest of the season out, it will be a coronation process for the Reds. The biggest stats story with Liverpool is in how they move the ball forward. Looking at the graph below, we can see the players most used in moving the ball both into the final third (x-axis) and then into the box (y-axis) are the two full backs, Trent Alexander-Arnold and Andrew Robertson.  But then we take a look at second placed Manchester City, and a different story emerges. It’s Kevin De Bruyne town, with the full backs a much smaller part of the picture.

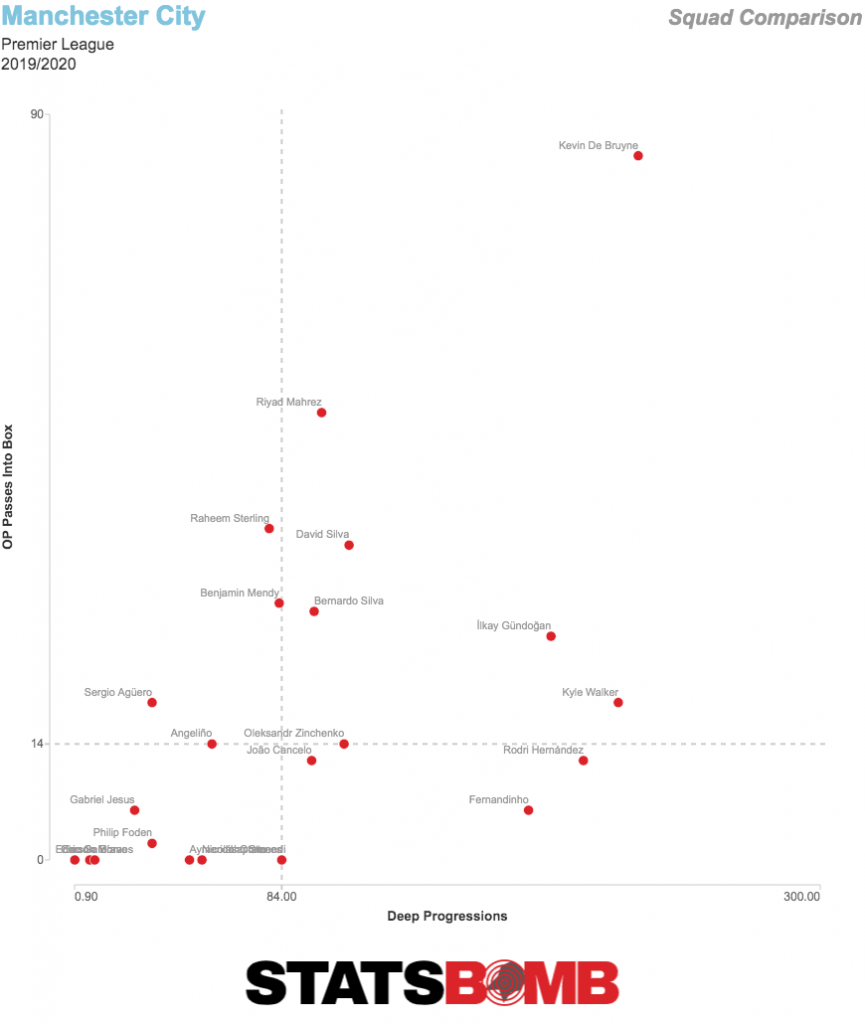

But then we take a look at second placed Manchester City, and a different story emerges. It’s Kevin De Bruyne town, with the full backs a much smaller part of the picture.  The top of the Premier League has two entirely different models for how a team should be able to get the ball forward without sacrificing solidity. There’s the Jürgen Klopp model, which takes the view that midfield should be kept as tight and ugly as possible, but then giving the full backs freedom to roam and become key players in the attack. The Pep Guardiola model, conversely, uses the full backs as facilitators in the midfield areas to make the side more solid, then allowing some of the nominal midfielders to be more involved in the final third. Both “work”, but it helps show the greater tactical variance in the league from 20, 10 or even 5 years ago. High pressing works, but there are other ways There has not historically been an obvious way of measuring "pressing", and a raw count of StatsBomb's pressure data does not instantly show a solution. When we look at the teams making the most pressures, we see a list that doesn't really correspond to most people's ideas of the Premier League's high pressing sides.

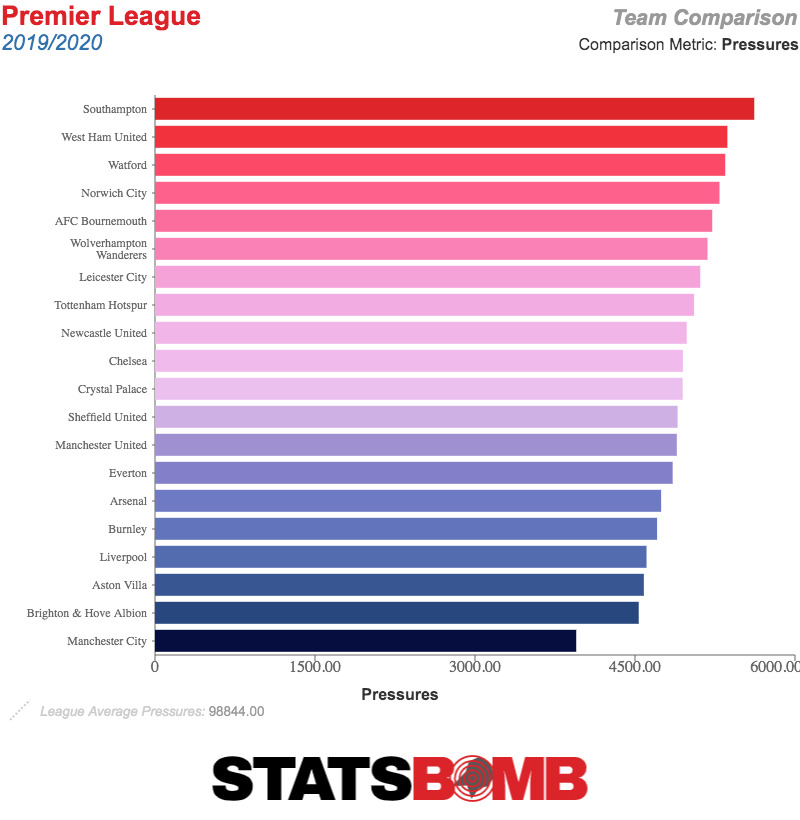

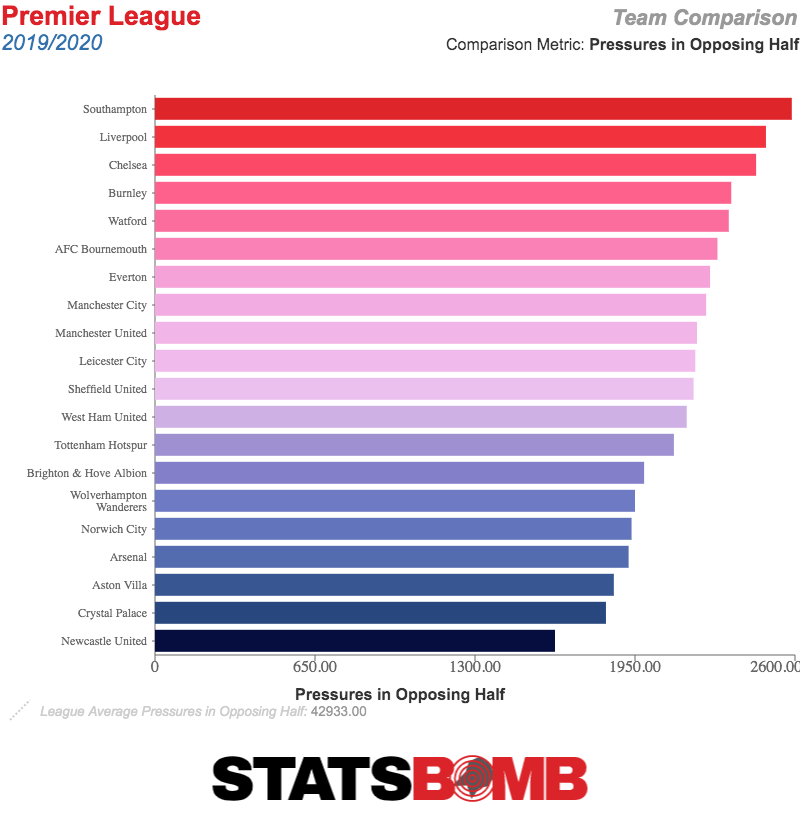

The top of the Premier League has two entirely different models for how a team should be able to get the ball forward without sacrificing solidity. There’s the Jürgen Klopp model, which takes the view that midfield should be kept as tight and ugly as possible, but then giving the full backs freedom to roam and become key players in the attack. The Pep Guardiola model, conversely, uses the full backs as facilitators in the midfield areas to make the side more solid, then allowing some of the nominal midfielders to be more involved in the final third. Both “work”, but it helps show the greater tactical variance in the league from 20, 10 or even 5 years ago. High pressing works, but there are other ways There has not historically been an obvious way of measuring "pressing", and a raw count of StatsBomb's pressure data does not instantly show a solution. When we look at the teams making the most pressures, we see a list that doesn't really correspond to most people's ideas of the Premier League's high pressing sides.  Man City at the bottom! That includes a lot of chaotic defending in teams' own third, so let's strip it down just to pressures in the opposing half. There's a little more of a pattern here.

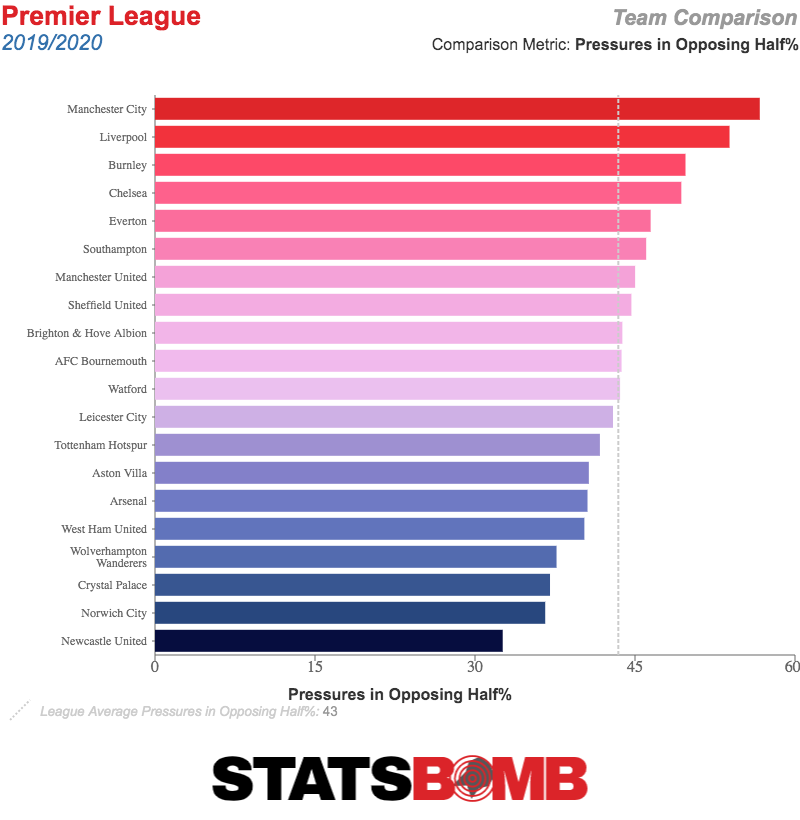

Man City at the bottom! That includes a lot of chaotic defending in teams' own third, so let's strip it down just to pressures in the opposing half. There's a little more of a pattern here.  Man City still look like a middling pressing team, which obviously isn't what most people see with their eyes. They have so much possession that they're rarely having to make many pressures, which is the issue here. Raw numbers of pressures don't seem to tell us much of note. If we just look at the percentage of all pressures made in the opposing half, then guess what? City shoot up to the top of the table.

Man City still look like a middling pressing team, which obviously isn't what most people see with their eyes. They have so much possession that they're rarely having to make many pressures, which is the issue here. Raw numbers of pressures don't seem to tell us much of note. If we just look at the percentage of all pressures made in the opposing half, then guess what? City shoot up to the top of the table.  The obvious surprise towards the top here is Burnley. We all know at this point that Sean Dyche’s side do things differently, so it does make some sense to see them statistically stand out like this. At the bottom we have mostly less capable sides, but third placed Leicester sit in midtable. So do teams that defend high do a better job of it? Let’s compare this number to sides' xG conceded.

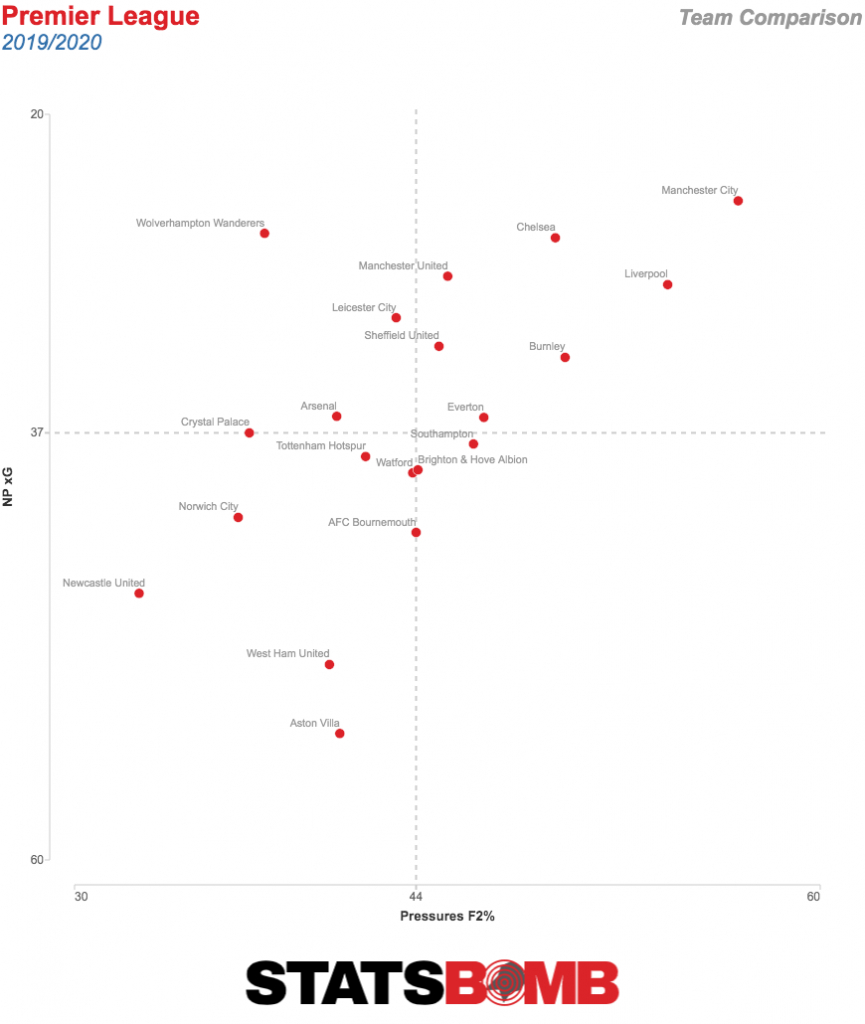

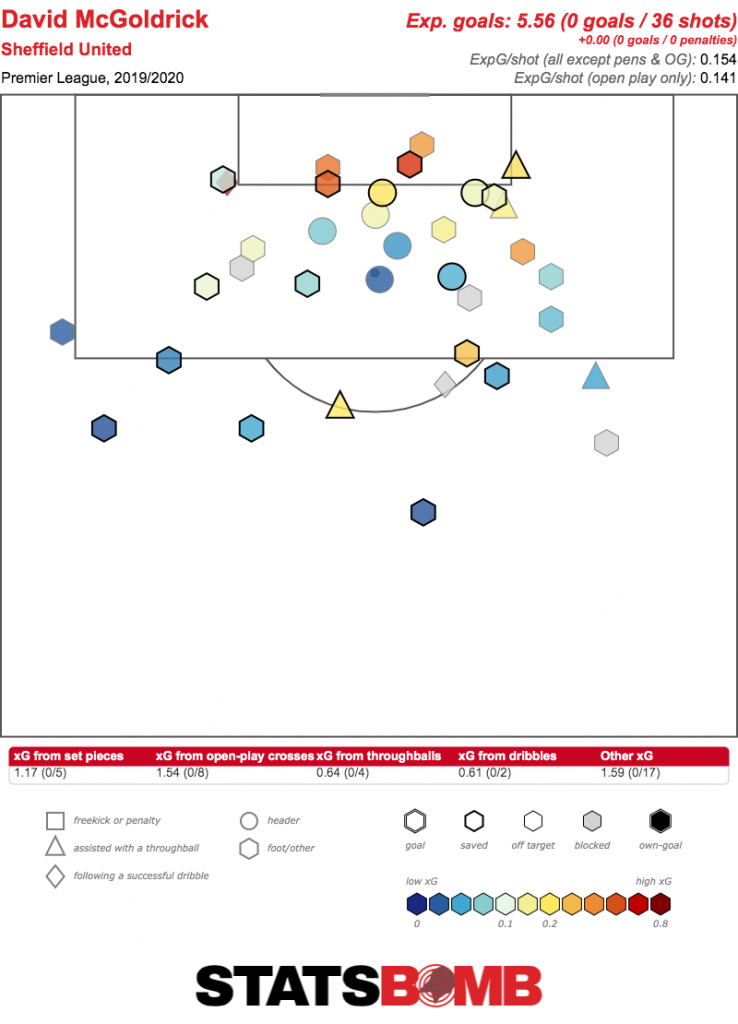

The obvious surprise towards the top here is Burnley. We all know at this point that Sean Dyche’s side do things differently, so it does make some sense to see them statistically stand out like this. At the bottom we have mostly less capable sides, but third placed Leicester sit in midtable. So do teams that defend high do a better job of it? Let’s compare this number to sides' xG conceded.  The obvious thing here is that the bottom right square is near empty. There isn't a team in the Premier League that offers an effective high press but just cannot defend at all. In terms of the sides that do actually defend well, there's a significant contrast. You have high pressers Man City and Liverpool, yes, but also a very solid Wolves outfit staying compact. The better sides do generally press more, but otherwise it isn't totally obvious that a particular pressing approach leads to better defending. David McGoldrick still can’t score goals Sorry, David. It feels mean at this point, but we can still gawk at your shot map one more time. Who knows, maybe your first attempt after football returns will go straight in the back of the net.

The obvious thing here is that the bottom right square is near empty. There isn't a team in the Premier League that offers an effective high press but just cannot defend at all. In terms of the sides that do actually defend well, there's a significant contrast. You have high pressers Man City and Liverpool, yes, but also a very solid Wolves outfit staying compact. The better sides do generally press more, but otherwise it isn't totally obvious that a particular pressing approach leads to better defending. David McGoldrick still can’t score goals Sorry, David. It feels mean at this point, but we can still gawk at your shot map one more time. Who knows, maybe your first attempt after football returns will go straight in the back of the net.  Next time, we’ll discuss some things we don’t know about the Premier League.

Next time, we’ll discuss some things we don’t know about the Premier League.

Month: April 2020

A Data History of the European Cup: 1960, Real Madrid 7-3 Eintracht Frankfurt

The brainchild of Gabriel Hanot, editor of L’Équipe, the European Cup, now known as the Champions League, very quickly established itself as the pinnacle of European club football after its introduction in 1955. Many of the sport’s greatest teams have since made concrete their legacies by lifting the famous trophy.

With the help of our data, I am going to analyse a European Cup final from each decade, from the 1960s through to the present day, looking at the trends, developments and differences over the years.

First up is Real Madrid’s 7-3 win over Eintracht Frankfurt in the 1960 final at Hampden Park in Glasgow, which remains the highest-scoring final in the history of the competition.

Real Madrid had won each of the first four editions and had lost just six times in 35 European Cup matches prior to this encounter. More than any other, they are a team defined by this competition.

Formations

This is still more or less the era of the 3-2-2-3 (WM) formation, with wingers, inside forwards and a centre-forward making up the front line. With certain variations, both teams employed that system.

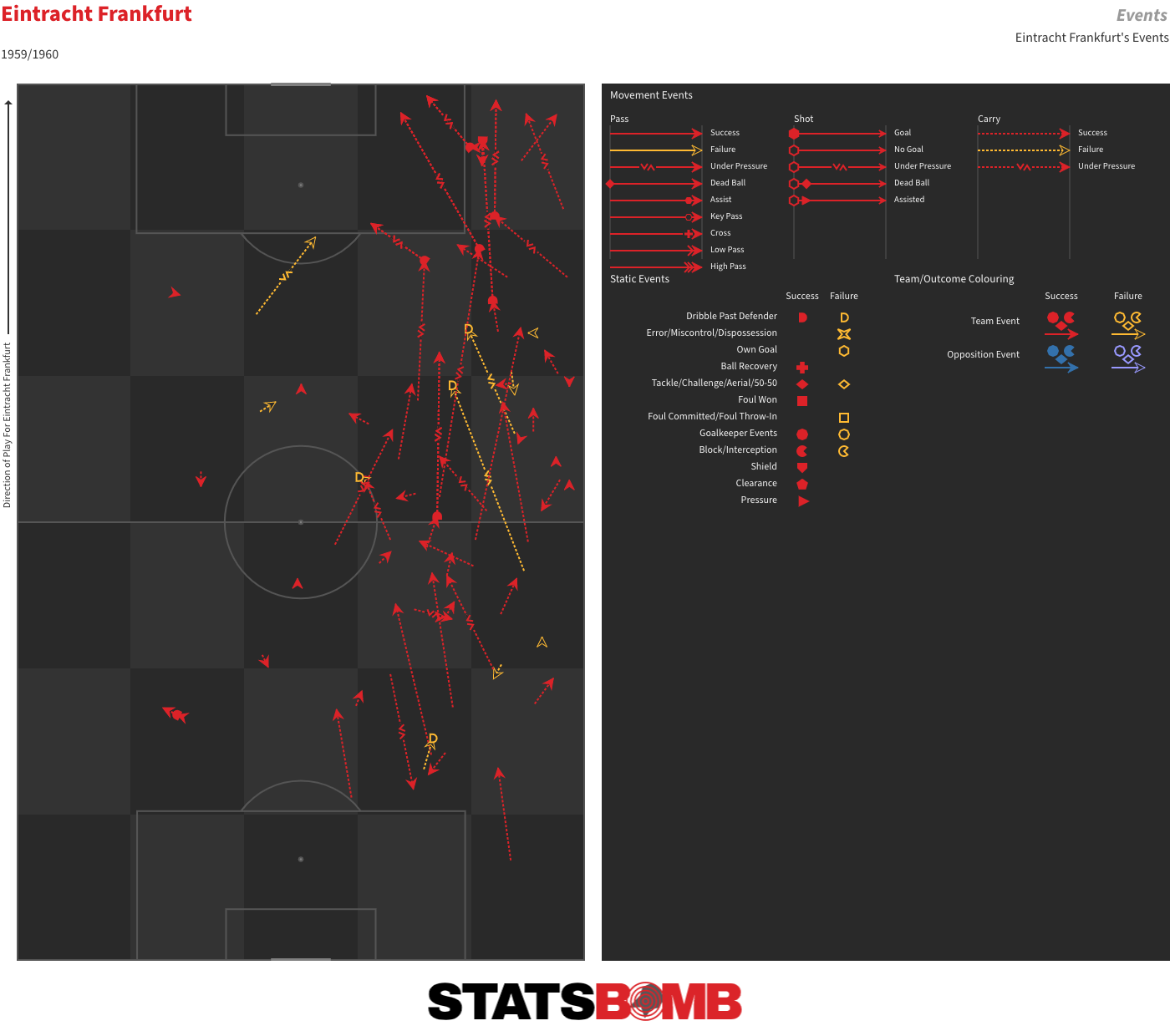

A Fast and Imprecise Game

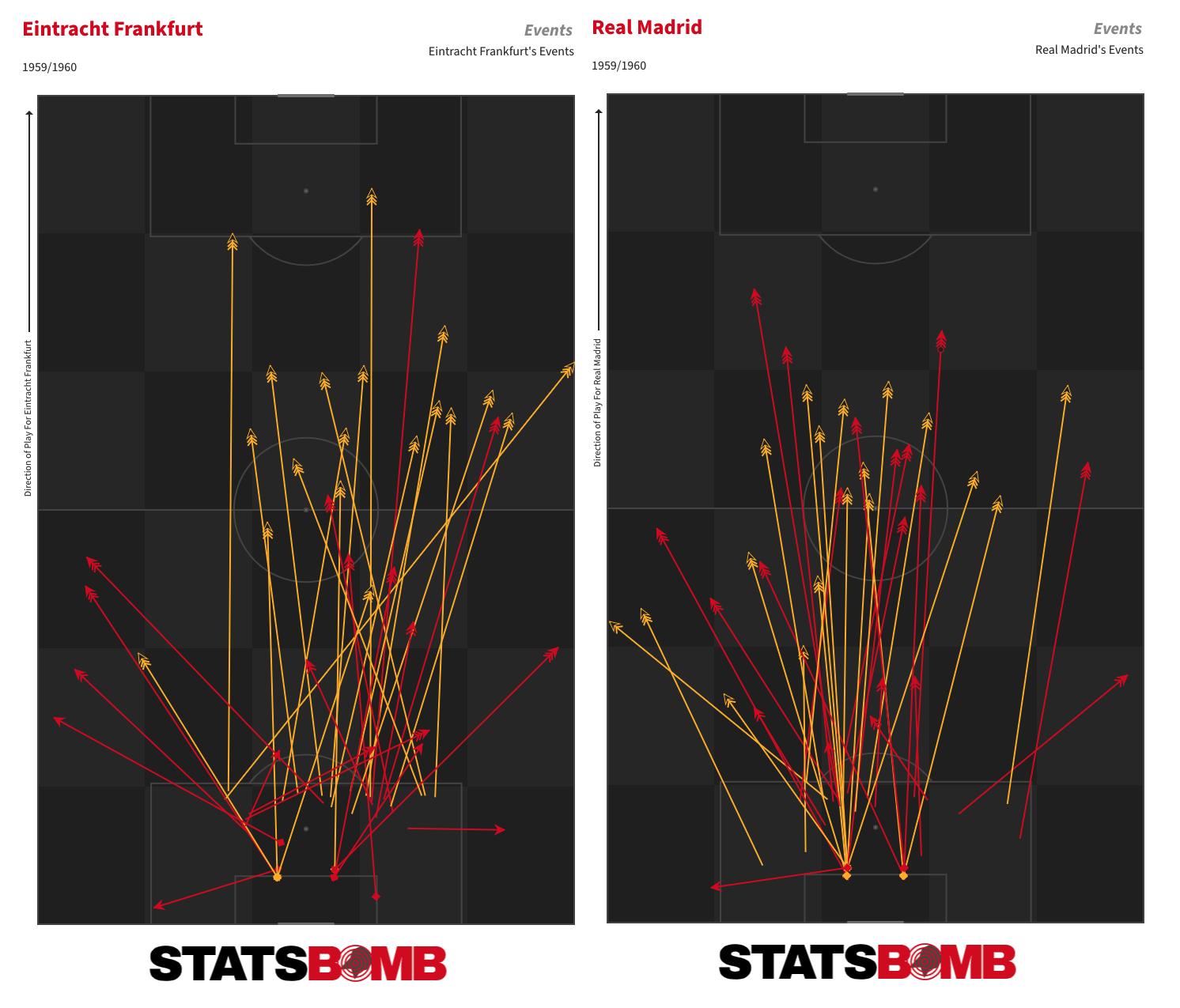

The first thing that immediately stands out is the number of times the teams turned over possession. Real Madrid completed just 69% of their passes; Frankfurt only 61%. For comparison, the average passing completion rate in last season’s Champions League was 80%. There were 483 distinct possessions in this match, compared to 374 in an average modern-day match in the competition.

In the commentary, much is made of the bumpy surface at Hampden Park. That may certainly have contributed, but those completion rates feel more like a consequence of the directness with which both teams played. This is the textbook example of a back and forth shot-fest. Upon gaining possession, both teams moved forward at a faster rate than modern-day teams, and the final shot count of 42 was 13 more than the tally in the 2018-19 final, and 15 more than last season’s competition average.

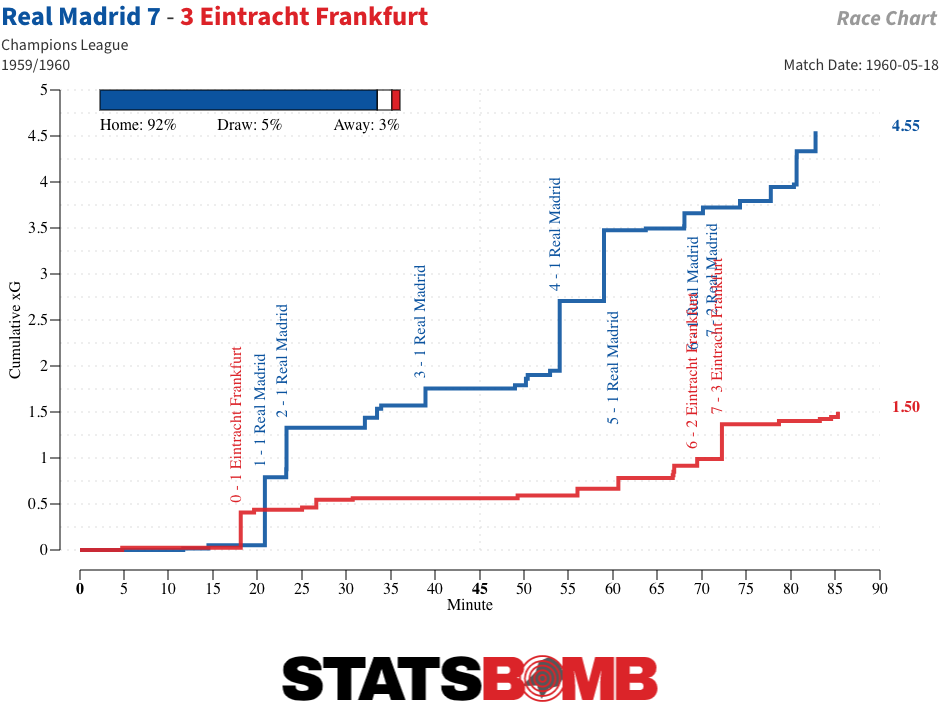

You don’t see many matches with xG sums like this these days:

This was a contest of quick passes, flick-ons and direct duels. Between them, the two teams attempted a mammoth 55 dribbles, of which 33 were completed -- itself about the average rate of attempted dribbles in last season’s competition.

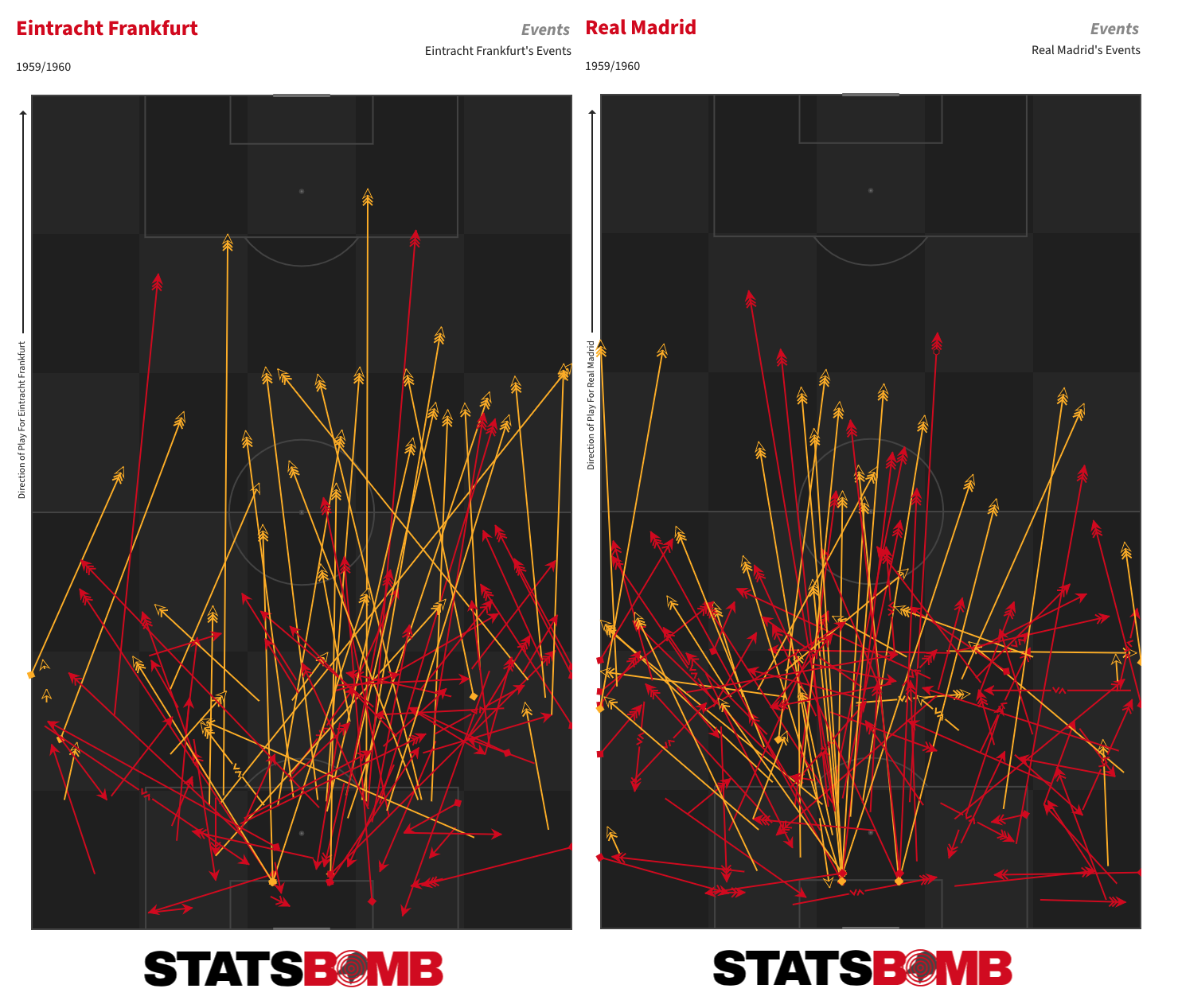

Goalkeepers Go Long

The impression I had when watching the match was that the two goalkeepers kicked long a lot more often than those of top teams in the modern game. Frankfurt’s Egon Loy got particularly impressive distance on a number of his first-half dropkicks.

The numbers bear that out. The average goalkeeper pass lengths of the large majority of teams considered viable winners of the contemporary Champions League fall within a range of about 32-40 metres. In this match, Real Madrid’s average was 48.86 metres; Frankfurt’s 50.93.

There were very few passing moves built up patiently from deeper areas. Real Madrid elaborated a little more inside their defensive third, but both teams mainly sought to quickly get the ball forward into the attacking half.

The majority of attacking moves arose from contested loose balls in the middle third of the pitch.

Alfredo Di Stéfano: All-Round Forward

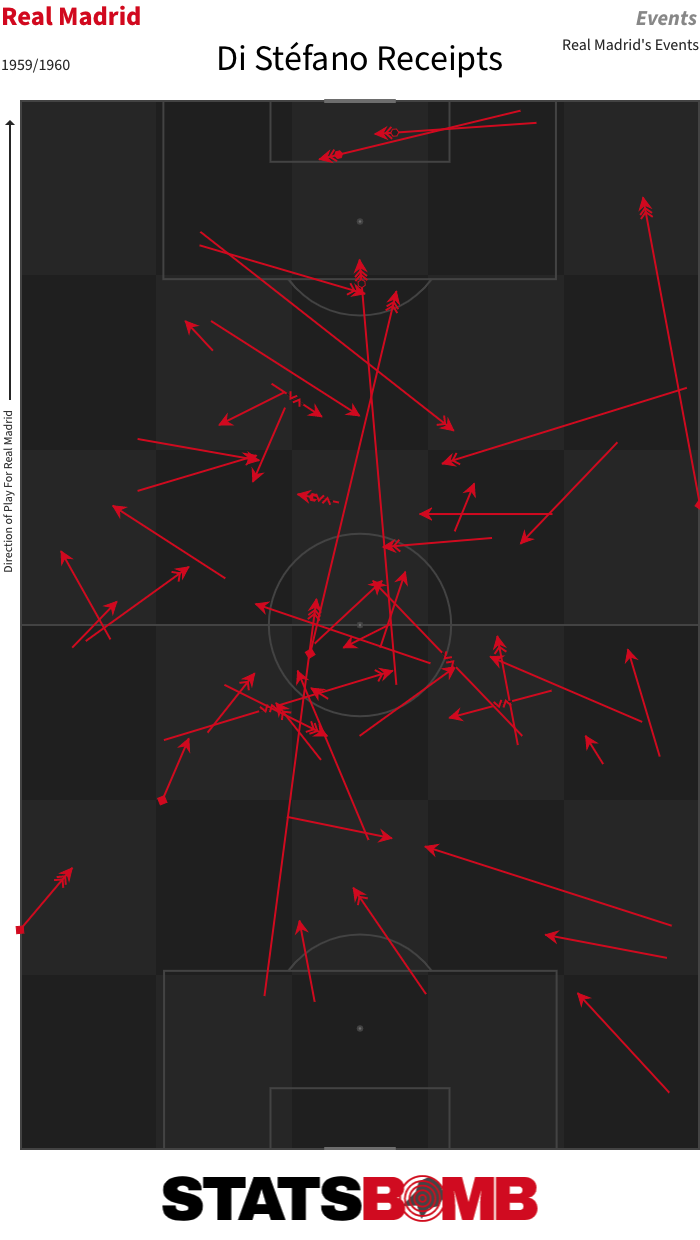

Alfredo Di Stéfano perhaps deserves a more prominent place in discussions over the best player of all time. A league-title winner in three different countries and the driving force behind Madrid’s five consecutive European Cup triumphs, he was not only a prime goalscorer but also a highly adept organiser of play.

In our recent series on Lionel Messi, I mentioned that Di Stéfano was the kind of withdrawn and roving forward that we’d probably describe as a “False Nine” in modern parlance, and that is very much played out by his role in this match.

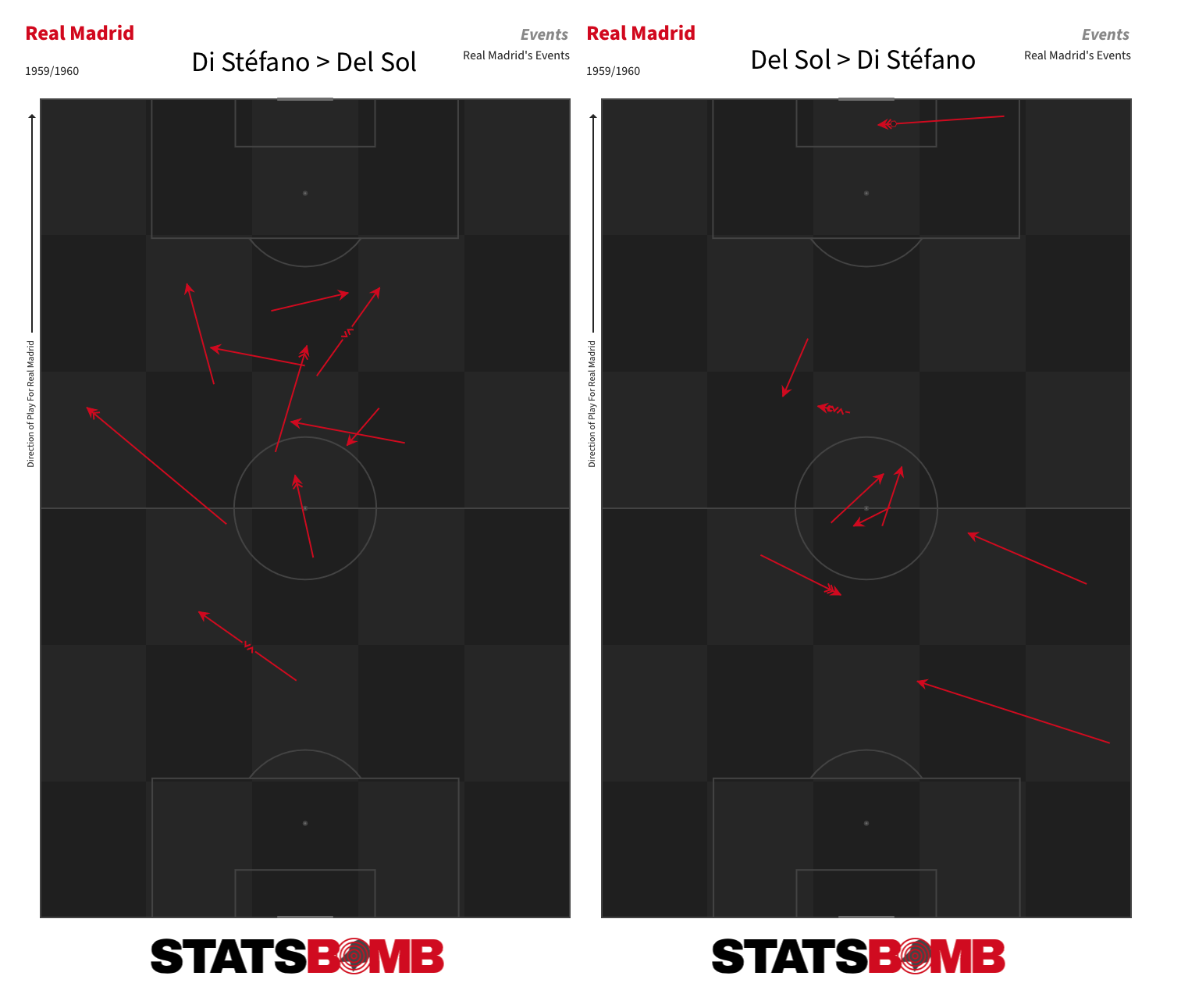

Di Stéfano’s first involvement is deep inside own half, receiving the ball from a teammate, dummying to pass and moving forward into the created space. It is a scene repeated throughout, usually accompanied by gestures of suggested movements for those around him. His receipt locations demonstrate the extent of his involvement in constructing play and bringing the ball forward.

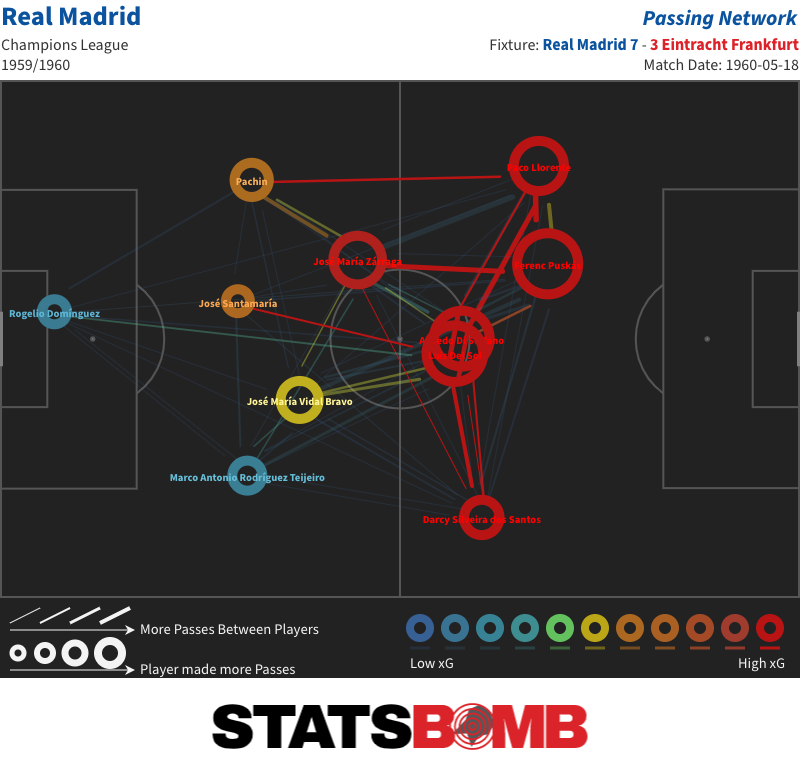

In Luis del Sol, an inside forward of energy and class, he had a key accomplice. They exchanged more passes than any other pair of players.

When Di Stéfano did appear in areas more consistent with his starting position as a centre forward, it was largely to finish from close range inside the penalty area. That was how two of his three goals arose.

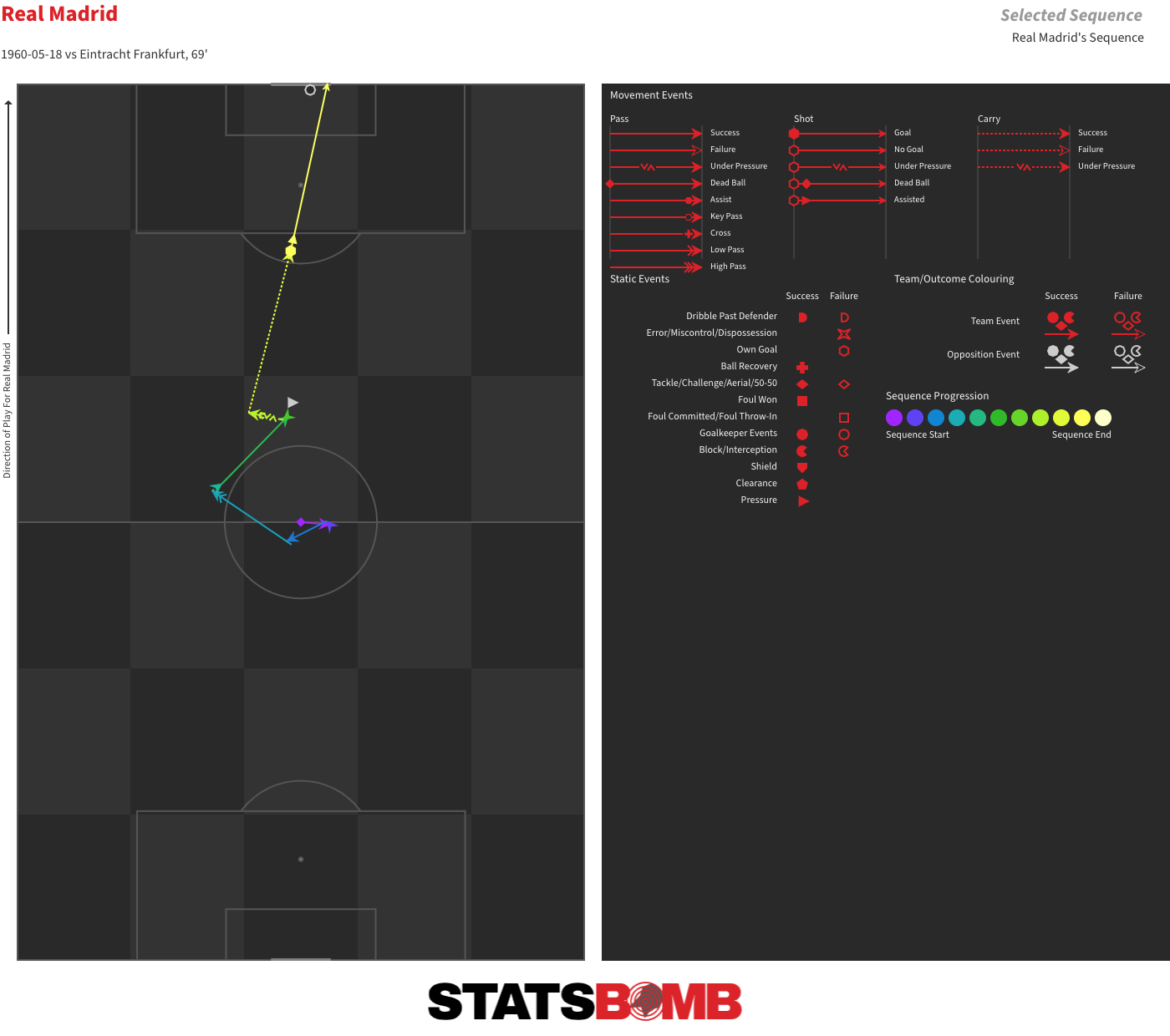

The third came from a kickoff. After exchanges with Gento and Del Sol, he accelerated through the centre of the pitch before firing home a crisp effort into the corner from outside the area. One of the great European Cup final goals.

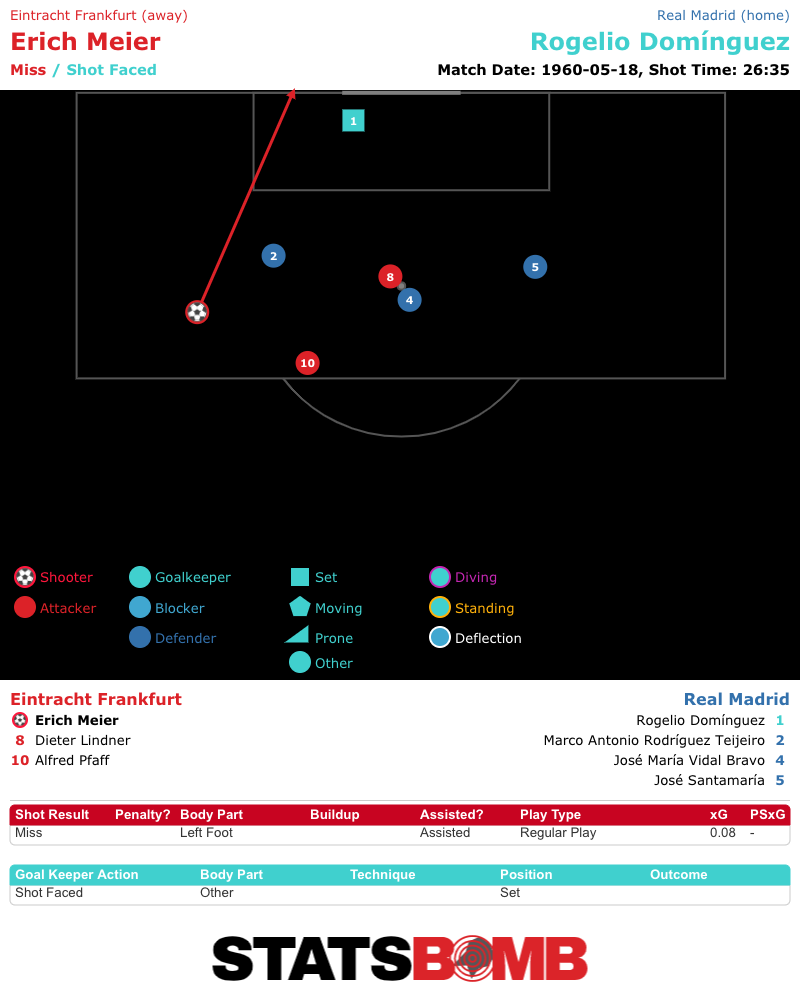

Puskás the Sharpshooter Di Stéfano may have notched a hat-trick, but he wasn’t Madrid’s top scorer on the day. That honour fell to Ferenc Puskás, nominally the inside left but more often than not Madrid’s most advanced player.

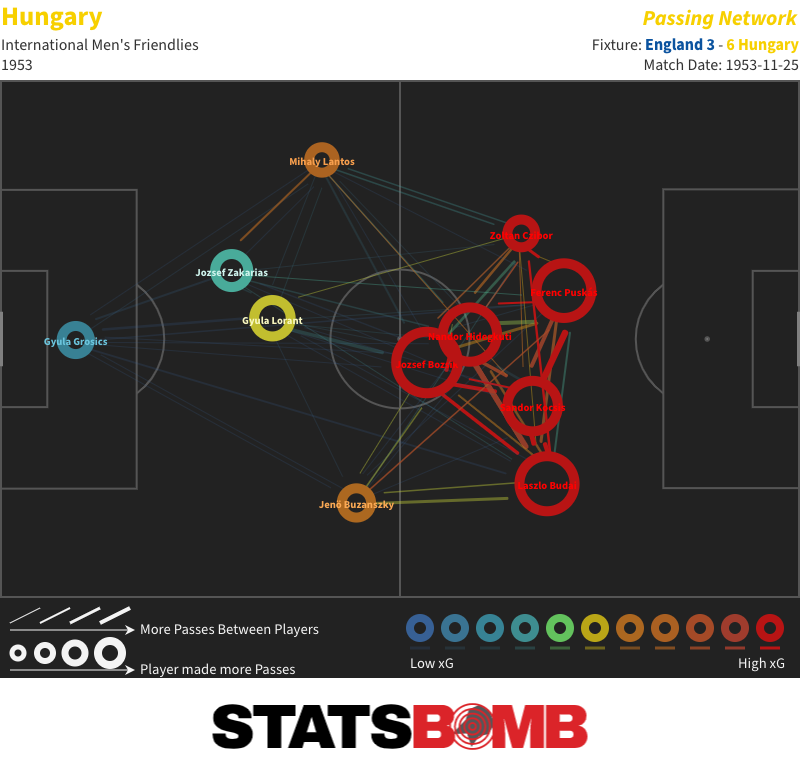

It was a role Puskás was used to performing. In the great Hungary side of the 1950s, he played alongside Nándor Hidegkuti, who, like Di Stéfano, was often more of a withdrawn playmaker than an outright centre-forward. If we look at the pass map from Hungary’s famous 6-3 win over England at Wembley in 1953, it is interesting to note just how similar the relative positioning and spacing is between Puskás and Hidegkuti there, and Puskás and Di Stéfano in this final.

Puskás was notorious for his powerful shot, and he does seem to spend a fair amount of this match casually walloping the ball goalwards whenever it comes his way. Even in a match of many shots, his total of 11 is still five more than any other player on either side.

His four goals (including one penalty) should have earned him the match ball for keeps. But the persistence of Frankfurt captain Hans Weilbächer eventually wore him down.

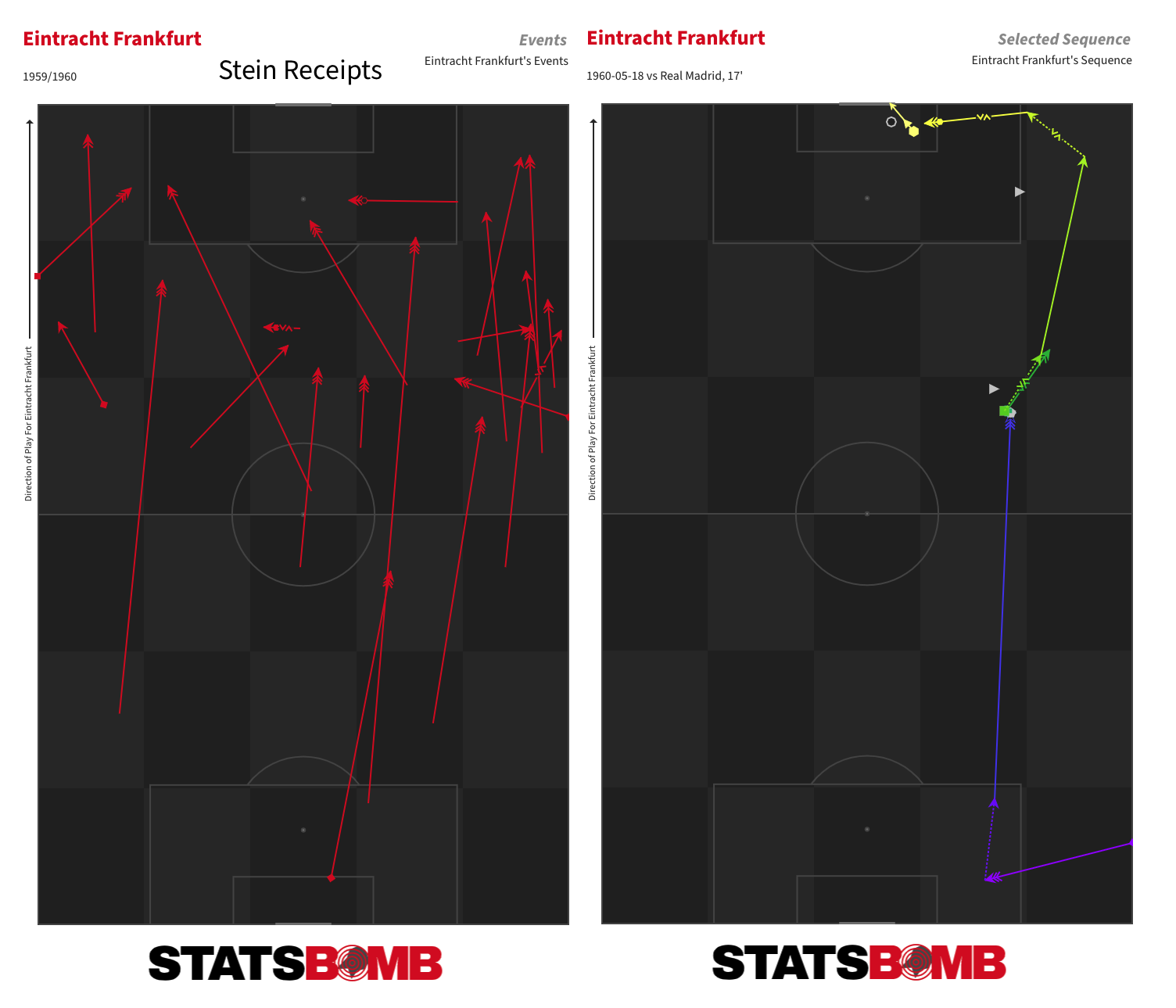

Eintracht Frankfurt’s Attack Frankfurt started the match well and even took the lead, but Madrid’s greater talent eventually began to shine through. By half-time, it already seemed likely they would be the losing side. The attacking output provided by their two inside forwards was much more limited than that of their Madrid counterparts.

The threat Frankfurt did carry came from the two wingers and centre-forward Erwin Stein. Richard Kress was a regular menace down the right, receiving and driving forward at every opportunity.

But it was Stein who caused most damage, scoring twice and assisting the other. In an era of man-marking schemes, it was interesting to note just how disruptive his peeled runs into the right channel proved for the Madrid defence. It was Frankfurt’s most reliable method for advancing into the final third and it yielded the opening goal of the match. He received a pass into that space from Dieter Lindner, drove on to the byline and crossed to the near post for Kress to finish.

Obstruction

To the modern eye, some of the fouls called in this match looked very soft indeed. The standard for what was considered an obstruction was obviously much lower at the time. Merely placing yourself somewhat across your opponent’s path was enough to be penalised. Madrid’s penalty is the very mildest of mild obstructions.

“He Should Have Scored” Watch

Our commentator, Kenneth Wolstenholme: “You can’t afford to miss chances like that and win the European Cup.”

StatsBomb LIVE Podcast: What Next For 2019/20, Romano Schmid Pro Scouting & The Wire: Season 2

The Evolution of Zinedine Zidane

Zinedine Zidane, ahead of the 2018 Champions League final. "I'm not the best coach, and I will always say that. I am not the best coach tactically... and, well, I don't need to say that because you lot always say that, anyway.” When Zidane returned to Real Madrid in March of last year, nobody knew what to expect. His first spell was a paradox, pairing historic achievements with bizarre inconsistency. The squad was incredible but also heavily reliant on individual heroics; with Cristiano Ronaldo gone and less talent at his disposal, many felt he would have to evolve. Madrid’s collective organization declined over the course of Zidane’s original tenure.

His first season was characterized by his unique strengths: convincing stars to defend and accept rotation, and starting Casemiro over more glamorous names in spite of Florentino Perez’s pressure. His final season was a tactical disaster: excessive crossing, Casemiro making runs forward, and Luka Modric defending at right back. One thing was abundantly clear then and now: Zidane’s ego doesn’t distort his evaluations, be it of players, coaches, or even himself. He is aware of his limitations, a theme going back to his own playing career. This is a man who resigned after a Champions League threepeat because he saw the writing on the wall for his burned out squad and didn’t try to defy it.

When he returned he was risking his legacy, but he seemed convinced he could again achieve success.

The Enigmatic Start To The Season

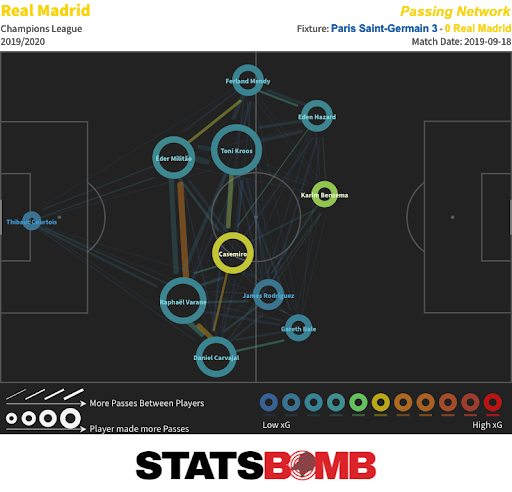

If Zidane had evolved, it was not immediately apparent. Pre-season was muddled by injuries to key players, a 7-3 loss to Atletico Madrid, and confusion over transfers. With Ronaldo long gone and the team needing goals from midfield to compensate, the squad depth seemed to lend itself to a 4-2-3-1 shape, accommodating James Rodriguez:

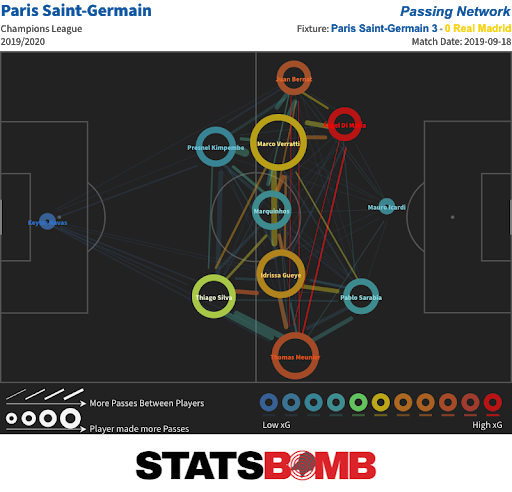

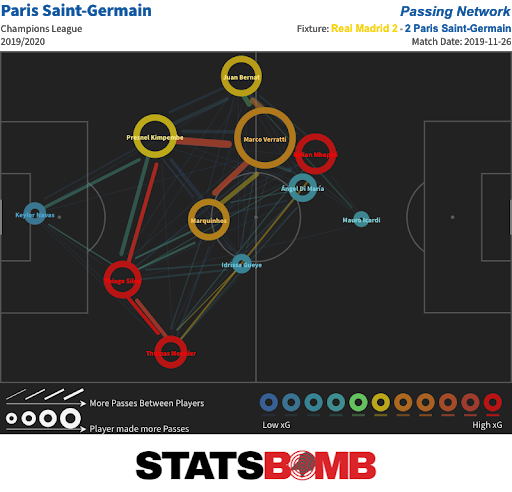

But every time Zidane played this midfield, Madrid’s buildup play suffered regardless of opposition. Without Luka Modric next to him, Casemiro took far too many risks near his own box. The defense wasn't working either, and much like Zidane’s first spell, Sergio Ramos and Raphael Varane were left to defend acres of space whenever they conceded a counterattack. This all culminated in the loss to Paris Saint-Germain. With Casemiro playing in the double pivot against Thomas Tuchel’s high pressing side, Madrid were played off the park. Casemiro’s usage and the total lack of connectivity standout:

PSG, however, managed to maintain excellent symmetric spacing. They sliced through the Madrid defense even without Neymar and Kylian Mbappe:

The aftermath of this game brought suggestions that Zidane could be sacked. Six full weeks into the season, after a huge summer outlay, the team was performing far below potential.

Revitalizing The Defense

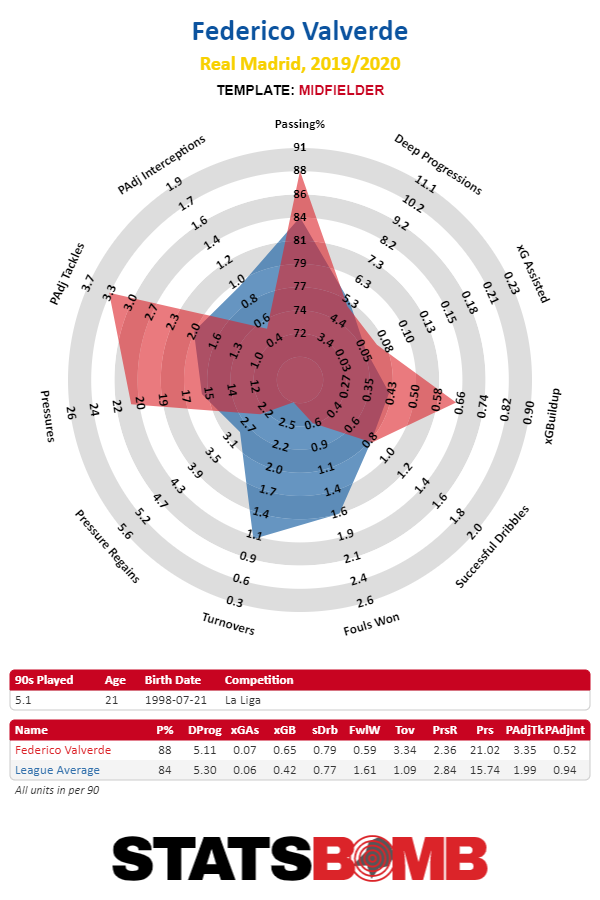

With the 4-2-3-1 experiment failing, Zidane moved back to a three-man midfield. Most importantly, he organized a stifling defense based around a more frequent press. The key to this change was the introduction of Federico Valverde as a box to box midfielder. His defensive intensity rubbed off on his teammates.

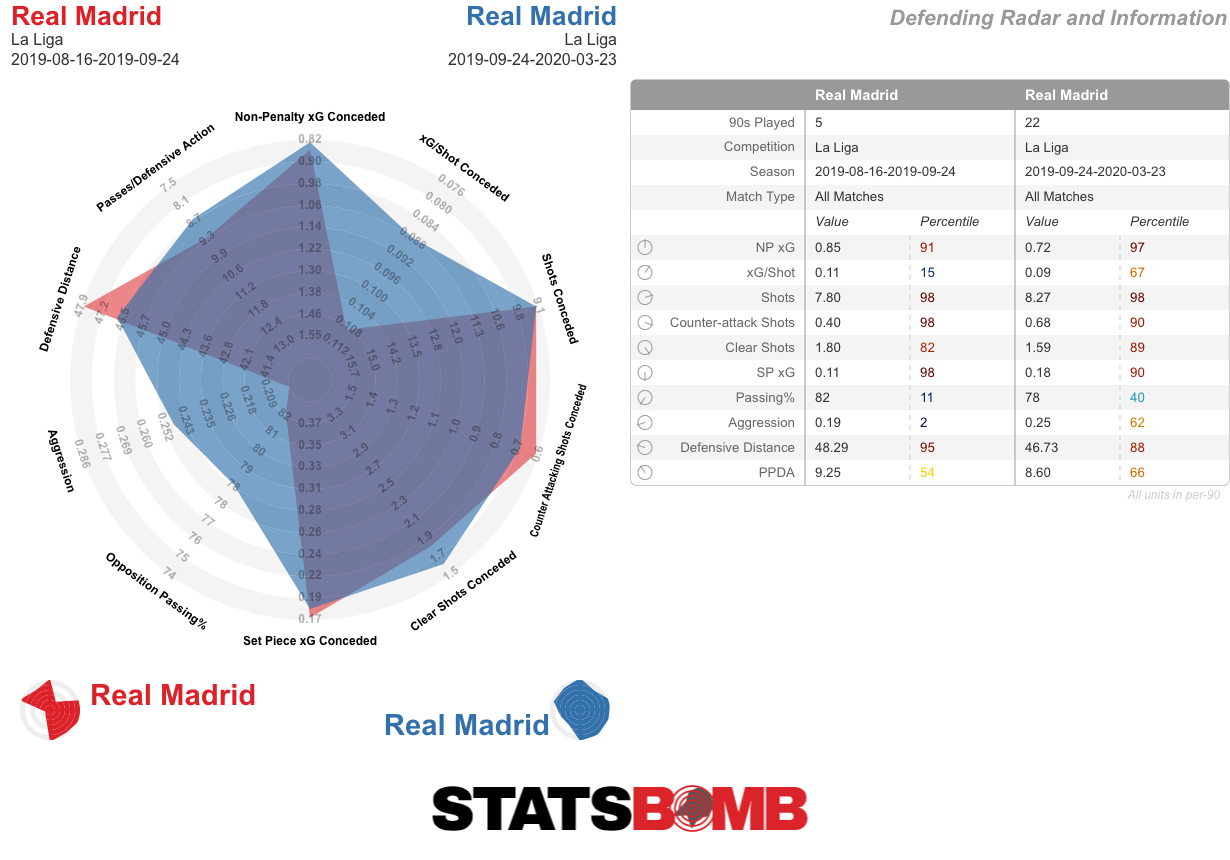

Valverde’s pace and physicality catalyzed a much more aggressive Real Madrid able to lean into their defensive identity. Opposition passing chains were more frequently contested, and opponents’ passing completion rates dropped. The shift is perhaps best illustrated by the change in the percentage of their defensive actions that we define as aggressive -- actions recorded within two seconds of the opposition receiving the ball. In the six games before Valverde’s introduction, Madrid were in the 2nd percentile of this metric. Ever since, they’ve ranked comfortably above average:

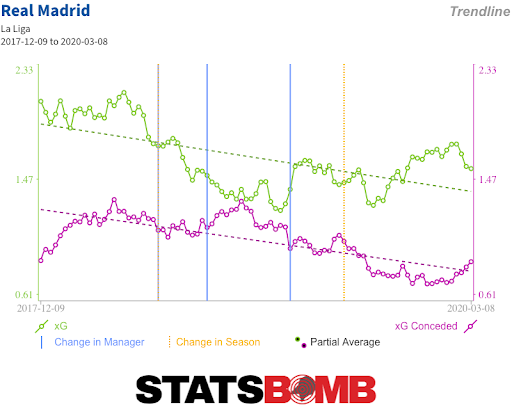

Opponents struggled to create high quality chances. This reorganized Madrid defense was among the best in Europe, and the best at the club in years. Their improvement is clearly visible in the xG trendline:

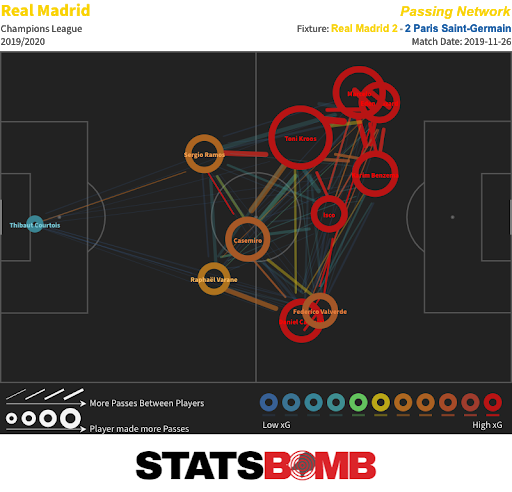

Buildup play also improved. Casemiro started taking a more passive role in buildup with Valverde available. The team was better able to reach the final third, and for a brief period when both Eden Hazard and Marcelo were healthy, they created chances at will. This is well illustrated by the reverse fixture against PSG. Madrid dictated terms with their high press, and Tuchel’s side were the ones with a disheveled passing network:

Zidane opted to play Isco in the diamond shape that won Madrid their Champions Leagues, with Hazard and Valverde replacing Ronaldo and Modric respectively. For the first hour this was one of Madrid’s most dominant performances in recent seasons.

The difference in Casemiro’s role between each game is telling. He played roughly the same number of passes in both games, even though Madrid had much more of the ball at the Bernabeu. When the team was clicking offensively, his relative usage rate was down.

Lingering issues

After a strong end to 2019, the xG trendlines correctly reflect that, for many reasons, Madrid have been relatively inconsistent. Offensively, the team has caught bad luck with injuries. Marcelo’s injuries signal the definitive end of his prime, and he isn’t even attempting one dribble per 90 anymore. His replacement, Ferland Mendy, is completing 2.5 per 90, but he is more effective with space than against a deep defense. Eden Hazard has missed most of the season due to injury.

Behind him, Vinicius Junior’s finishing and combination play leaves much to be desired. That he is up to 0.48 expected goals and assists per 90 minutes is encouraging in the long term, but his actual scoring contribution is only 0.28 goals and assists. This season, Madrid needed Hazard to reach their offensive ceiling. Marco Asensio, who was set to get an extended run at right wing, tore his ACL in the summer.

The domino effect played a role in both Rodriguez and Gareth Bale staying at the club. Rodriguez has struggled to stay fit and has barely contributed. Bale’s production is down to 0.43 expected goals and assists per 90 minutes, and he doesn’t appear to have the ability to seize games anymore. Arguably more than any other top coach, rotation is at the heart of Zidane’s coaching philosophy as well. He is uncompromising, and has reaped the rewards by winning the Champions League in every season he completed as head coach.

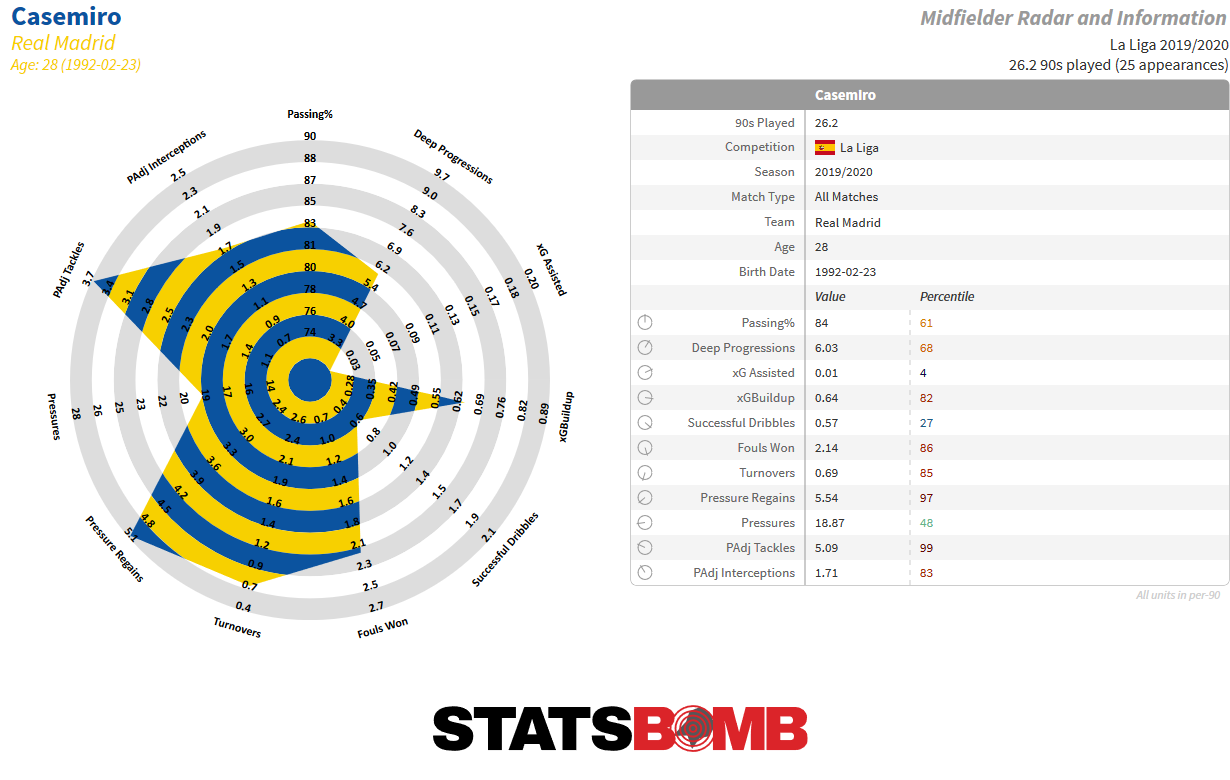

This season, however, that rotation has hurt the team’s cohesion. Defensively, there is no natural replacement for Casemiro. He sat on the bench as Madrid conceded four goals en route to a Copa Del Rey elimination against Real Sociedad. He is arguably the best destroyer in Europe. Over the past few seasons, he ranks in the 98th percentile for possession-adjusted tackles and 99th percentile in pressure regains among midfielders in the big five leagues.

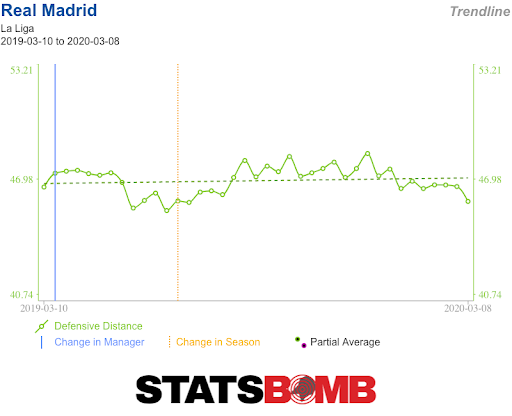

Valverde is also hard to replace. Modric was an excellent defensive presence a couple years ago, but at 34 he struggles to match Valverde’s tenacity. Starting January, Zidane began rotating the duo more heavily, and Madrid’s defensive line has moved slightly deeper as a result:

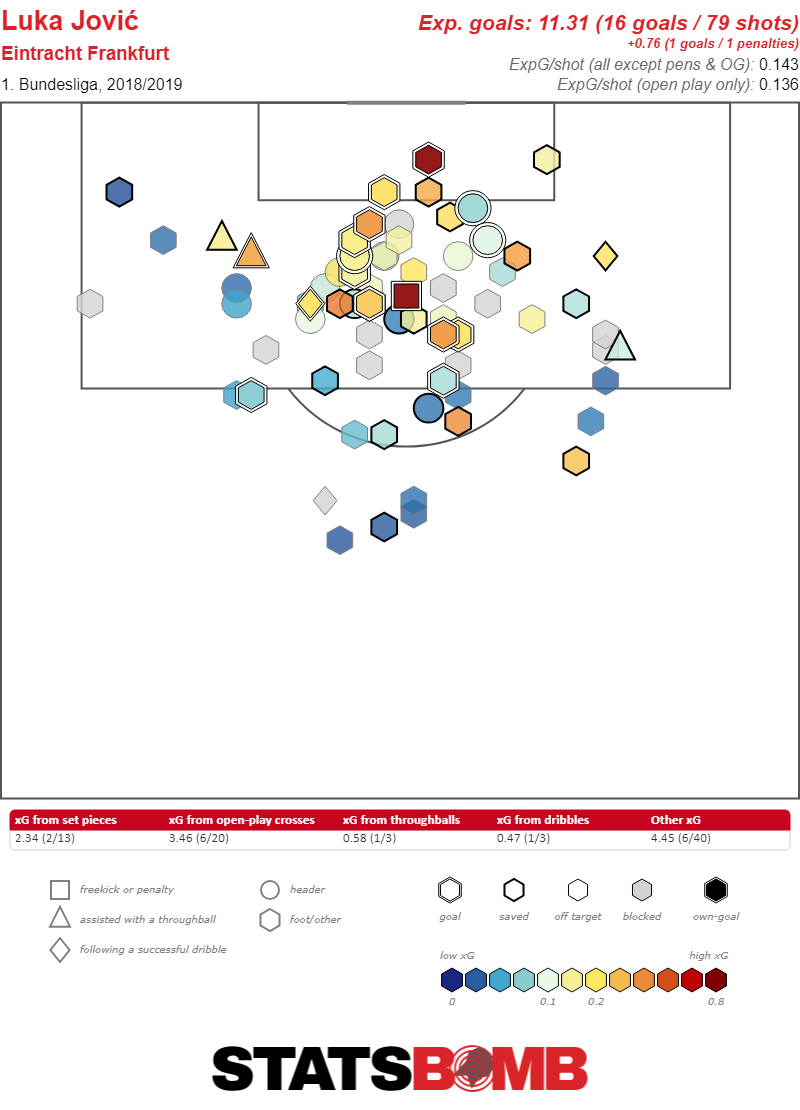

This rotation policy, combined with a limited approach in the final third, is why Zidane has struggled to integrate Luka Jovic. The Serbian was supposed to help replace Ronaldo’s production, but has only played five full games worth of minutes in La Liga. Karim Benzema has had to shoulder the scoring load, with others chipping in.

Jovic is putting up far fewer shots at Real Madrid, often looking disconnected from the unit on the pitch. This is partly fuelled by a change in role. At Frankfurt, Jovic was involved in a far more direct team, and had more space to work with. He would receive the ball in central areas and lay it off against less compact defenses. With more space, he had the license to take more risks.

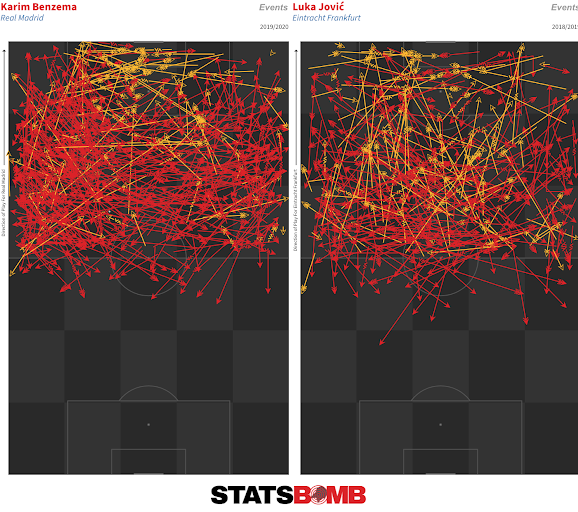

At Madrid, he often faces deep lying defenses, is often isolated up front, and rarely seeks to combine at a slow pace. It doesn’t help that he’s trying to replace Benzema, who is among the best strikers in Europe at this very role. Benzema is all about making himself available to receive the ball in the half spaces to combine with full backs. The difference in pass attempts also reflects how Jovic was used to playing faster and more vertically:

Zidane isn’t blameless here. Jovic has only started four games in the league. He often comes onto the pitch at the expense of a midfielder, when Zidane switches to a 4-4-2 while chasing the game. This leaves Casemiro exposed in a double pivot, and Madrid have subsequently lost control of the ball instead of feeding Jovic. On a team level, Madrid attempt far too many aerial crosses. This is a habit carrying over from Zidane’s first spell, when Ronaldo was a target, but is less effective with Benzema leading the line alone. Perhaps more low, cut back crosses are in order. The bulk of the improvement, however, will come with new personnel and time.

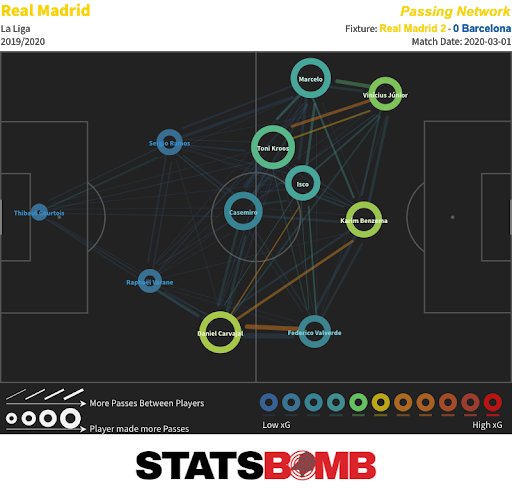

Completing The Team

To succeed with Zidane, Madrid will primarily require better offensive talent and depth. The attack also needs more symmetry; most of the team’s high usage players in each line of play operate on the left (Ramos, Toni Kroos, Isco, Hazard and Vinicius). Most passing networks resemble this:

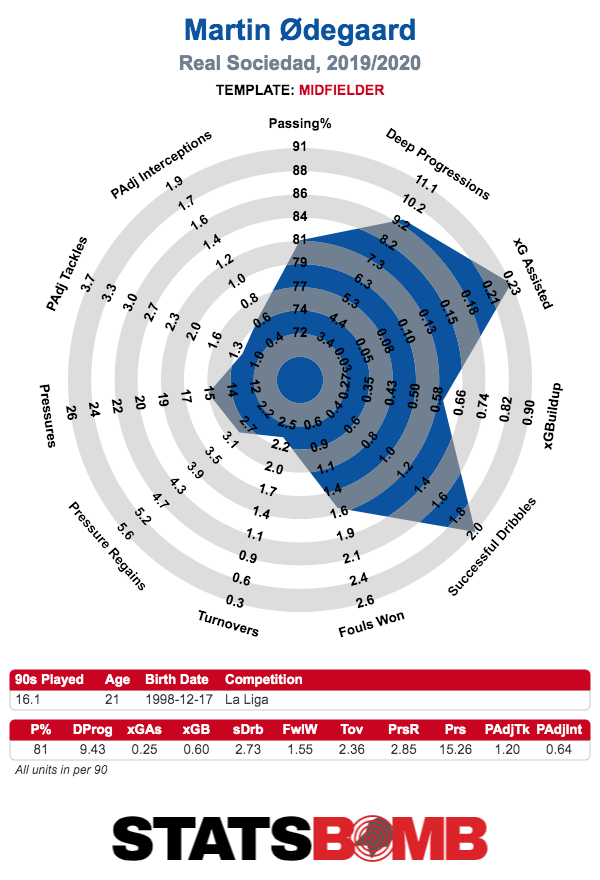

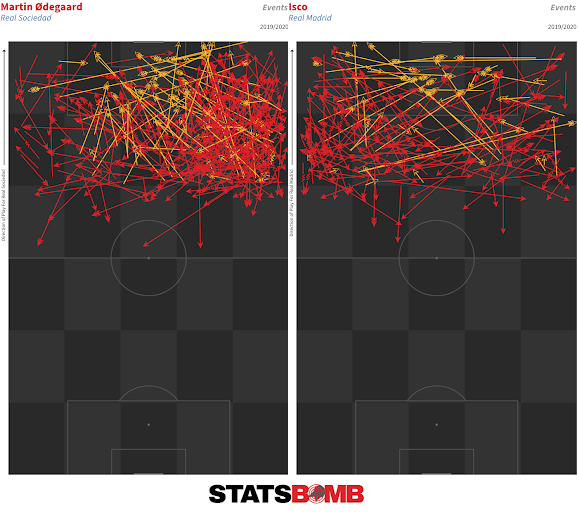

Given their needs, Madrid’s returning loanees and the players they’ve been linked with fit extremely well. For starters, Martin Ødegaard - if his loan is cut short - would be a better fit than Isco. Isco is a ball magnet. He excels at creating numerical overloads, dribbling and drawing fouls in tight spaces, but is not great at creating chances. This is why he’s been more effective for Madrid in big Champions League ties, helping Madrid control the ball and evade the high presses of Liverpool, Bayern Munich and others, than in the league, where he’s asked to break lines against deep defenses.

In contrast, Ødegaard is among the best at scanning his surroundings and breaking defensive lines. Team style shouldn’t be discounted here, but on the evidence of this season, he is a much more direct player, consistently seeking to receive the ball between the lines and completing more deep progressions. Ødegaard plays 26% of his passes forward to Isco’s 15%, and only 9% backwards to Isco’s 14%. They complete a similar number of dribbles, but the former releases the ball faster instead of drawing fouls:

Ødegaard is a high IQ passer, and would help restore some symmetry by operating on the right of the midfield zone:

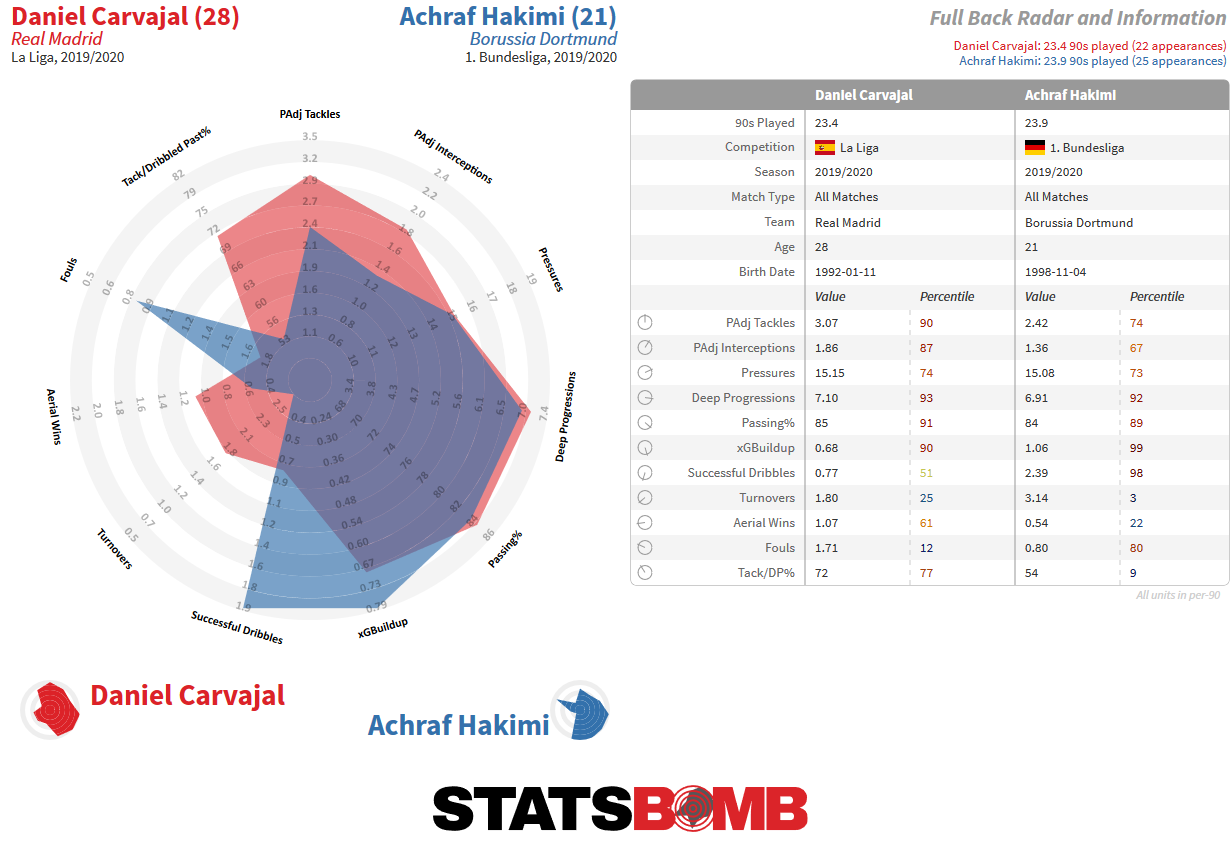

Achraf Hakimi is set to return from loan and is an excellent fit as well. Madrid need more attacking quality at full back to replace Marcelo. Carvajal sufficed in the past, but his solid aerial crossing technique has proven less useful since Ronaldo’s departure. Hakimi is by no means as diligent a defender as Carvajal. This bears out in the numbers: Carvajal is dribbled past less often, contests and wins double the aerial duels. But Hakimi is a better dribbler, carrying the ball more often and further when he does.

At 21, Hakimi is still growing. He has turned the ball over more often this season than any Real Madrid player barring Eden Hazard. He may not displace Carvajal immediately, but he does address Madrid’s offensive weakness on the right wing. On the right wing, the suspension of football gives Marco Asensio a fantastic chance to return from injury as the same player as well.

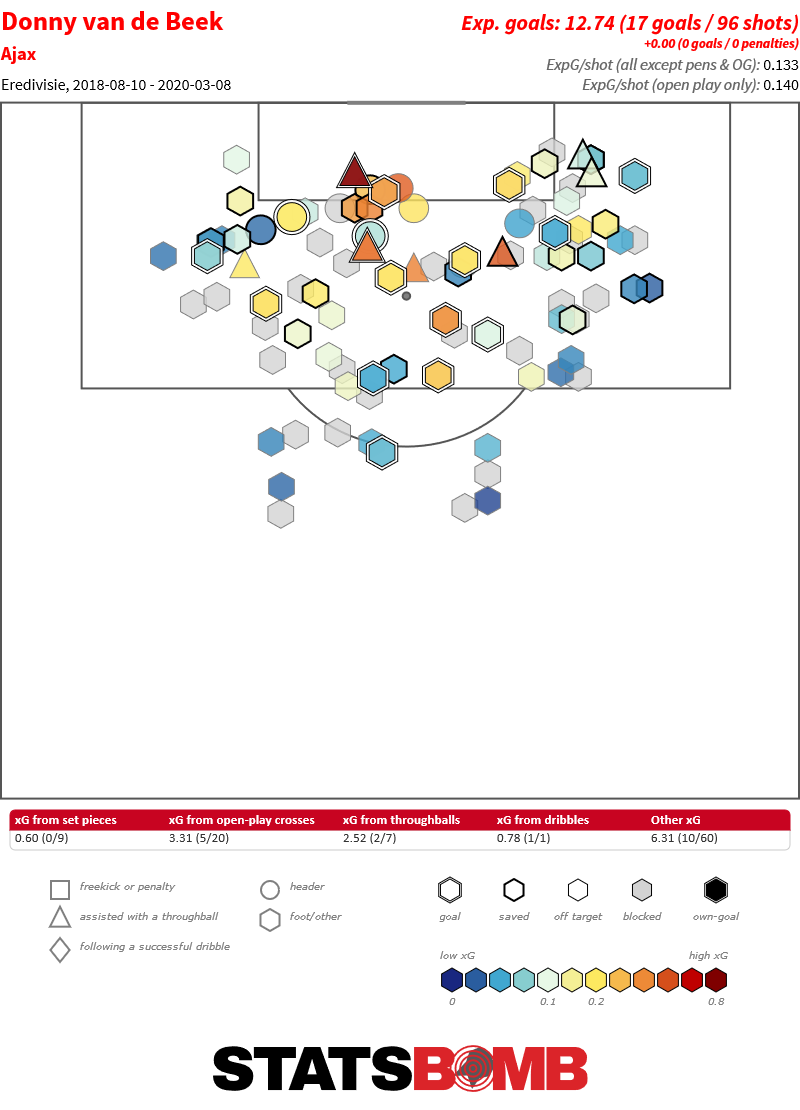

Most complications after recovering from ACL tears take place when a player is rushed back. Another name linked to Madrid is Donny van de Beek. Profiling as an offensive alternative to Valverde, he is a high volume tackler, and also excels with his late runs into the area. He shoots and gets more touches in the box than any Madrid midfielder, contributing to a goal every other game -- albeit in the Eredivisie.

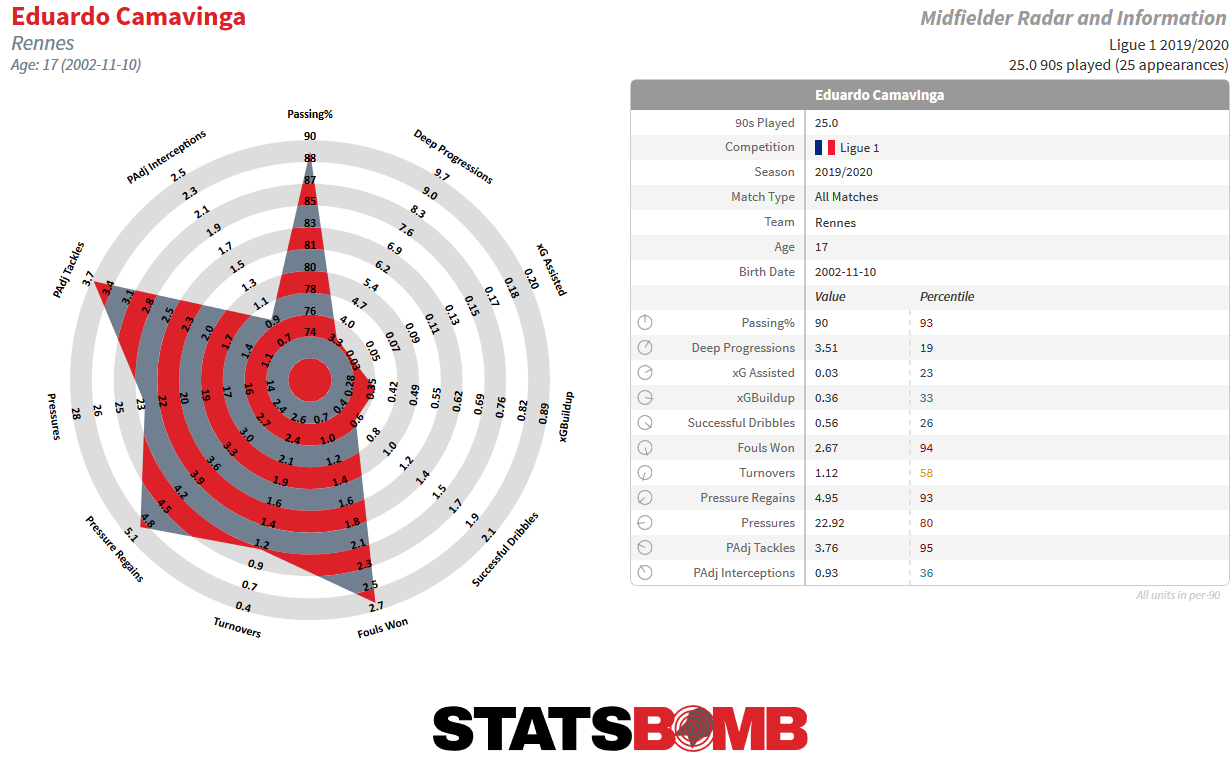

The team also needs a backup for Casemiro. Rennes’ Eduardo Camavinga profiles especially well. At just 17, he has been among the best defensive midfielders in Ligue 1. Zidane’s French connection could push the deal through:

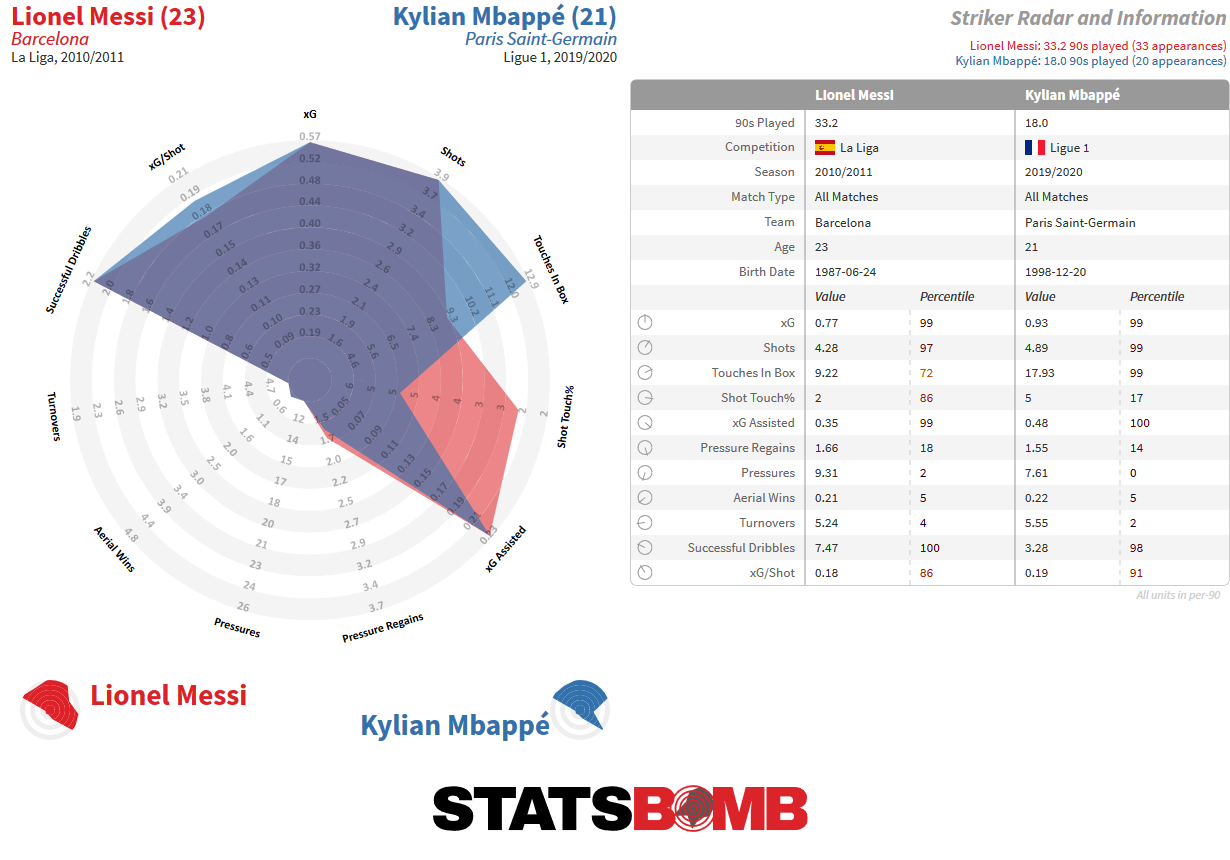

Lastly, Madrid have publicly courted Kylian Mbappe. The French superstar is now the most devastating goalscorer in the top 5 leagues. His production is historic:

Mbappe alone should shoot Real Madrid’s offense back to the levels of the Ronaldo era. That is likely Zinedine Zidane’s endgame.

The StatsBomb Interviews: Ted Knutson Meets... Oliver Bartlett

Ted Knutson talks to Oliver Bartlett, a fitness coach who has worked with some of the biggest and best in football in a career that included Dortmund, Salzburg, Leverkusen and most recently to China.

Downloadable on the soundcloud link and also available on iTunes, subscribe HERE

RSS feed, if required, here

Also available on Spotify, Stitcher

Decoding Diego: Maradona by the Numbers

The suspension of modern football has given us time to go back and collect data from some older matches. Amongst other things, it can be used to look at some the game’s greats from a different perspective. Diego Maradona certainly fits into that group. Some will no doubt consider it sacrilegious to wrestle a player who inspires such a viscerally emotional response into the realm of expected goals, deep progressions and pressure events, but here we are. What can we glean from the limited five-match sample we have in our system?

A Battle in the Bernabéu

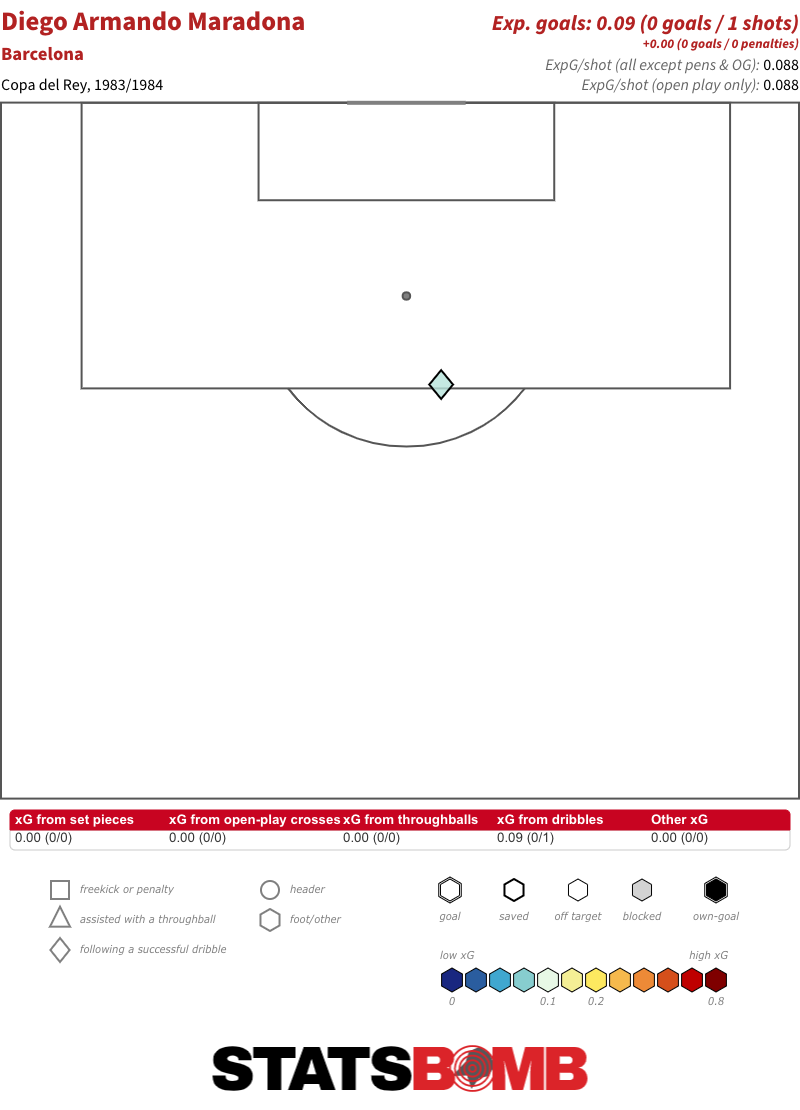

The first Maradona match we have collected is the infamous 1984 Copa del Rey final between Athletic Club and his Barcelona side. This isn’t really early stage Maradona. He was eight years into a career that had begun at 15 at Argentinos Juniors, and that had already yielded a league title at Boca Juniors, a starting role at the 1982 World Cup and a world-record move to Spain. It is, though, before what is generally considered to be his true peak.

That may partly be for reasons of circumstance. There were some highs for Maradona in his two-year spell at Barcelona. He had provided the assist for the opening goal in a lively performance in their victory over Real Madrid in the previous year’s final, and earned applause for a cheeky pause before finishing against the same opponents away in the league. But illness and injury prevented him from ever building up much rhythm.

It is no wonder he struggled with injuries when you see the punishment he endured in this match. Eight months earlier he had been on the receiving end of a brutal sliding foul from Athletic’s Andoni Goikoetxea that had kept him out of action for three months. The challenges were similarly rough in this one. Even in the context of a generally ill-tempered encounter, with 32 fouls committed by Athletic and 21 by Barcelona (as a basis of comparison, there were just 30 fouls in total when the sides met in the quarter-final of the 2019/20 competition), Maradona seemed to be singled out. He was fouled nearly three times as often as any of his teammates. Eleven times in total.

The majority of those came as he received with his back to goal, most of them courtesy of the close and aggressive marking of Iñigo Liceranzu, whose litany of fouls were all at least booking worthy in their own right by modern standards. Not to mention his other unpunished hacks as play moved on. In a way, Maradona had the misfortune of being caught in a transitory period between the even rougher defending Pelé et al often had to contend with in the 1960s and the incredible fitness and preparation advances of the modern era.

In his time, players were becoming more athletic and spaces on the pitch were reducing, but refereeing wasn’t yet as stringent as it would later become. The decision of coach and compatriot César Luis Menotti to field him as a lone central striker does him no favours. It was an idea Menotti also used at the 1982 World Cup, and which there too left Maradona at the mercy of opposing defenders when he received with his back to goal. He spends much of this match either being fouled or trying to engineer first-time layoffs to teammates as he hops up to avoid swiping legs.

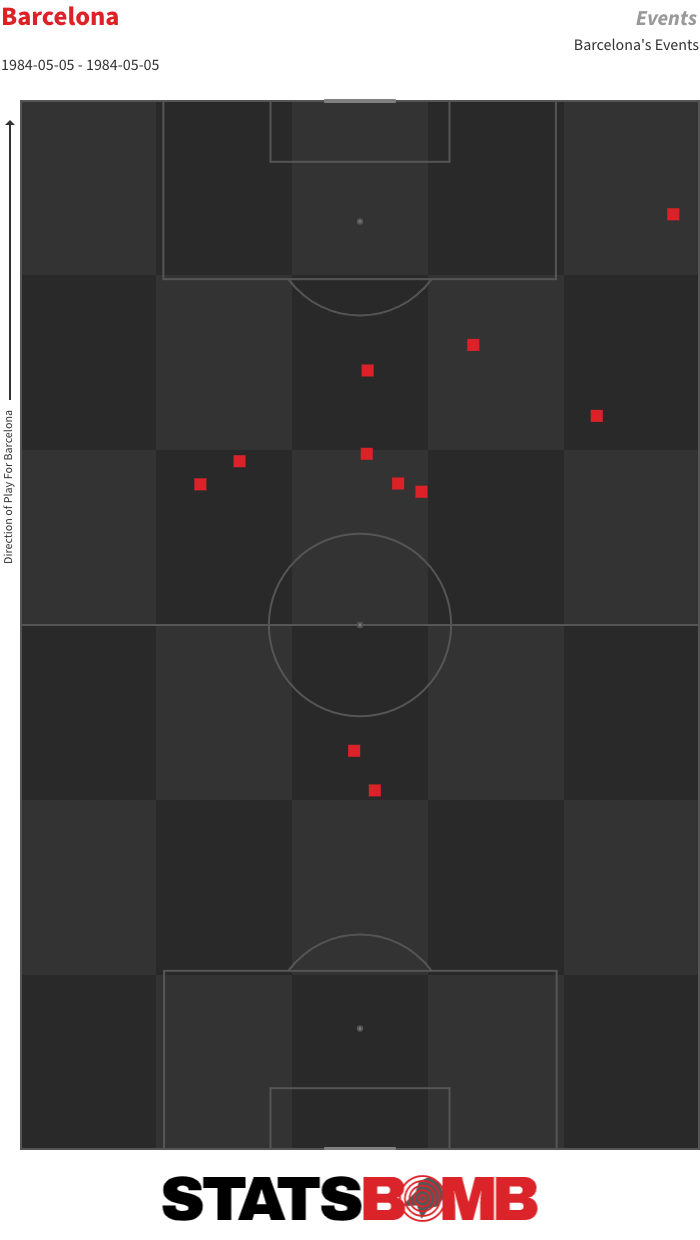

Barcelona struggle to make much attacking progress. Despite Bernd Schuster’s constant probing, including nine attempts to link directly with Maradona, they are just unable to pierce the defence of an Athletic side who won the league and cup double this season. Maradona musters just one shot and one key pass.

Bogged down by the system and circumstances, frustrated at his inability to influence the outcome, Maradona snaps at the final whistle, kicking off an ugly brawl that contributed heavily to the early termination of his relationship with Barcelona.

Peak Maradona

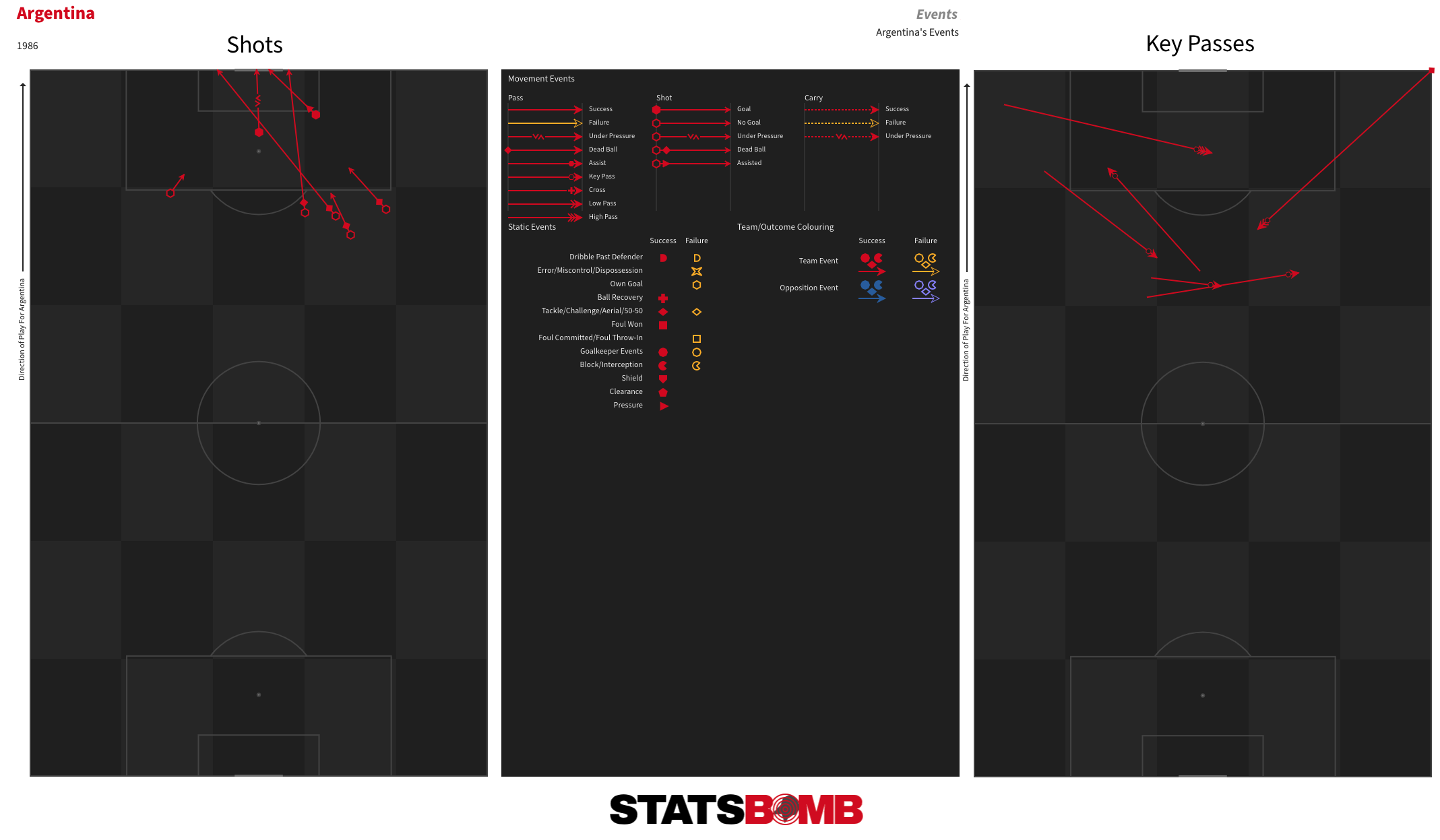

Perhaps no match epitomises peak-era Maradona more than Argentina’s 2-1 win over England in the quarter-final of the 1986 World Cup. Everything is there: the deceit, the trickery and above all, the outright brilliance. The narrative around Argentina’s triumph in this tournament has often been that Maradona dragged an otherwise ordinary team to victory. In the attacking sphere, at least, he certainly had an outsize influence. He scored or assisted nearly three-quarters of Argentina’s goals, and his dominance of their offensive output is clear in this match. Argentina had 15 shots, 13 of which were taken or assisted by Maradona.

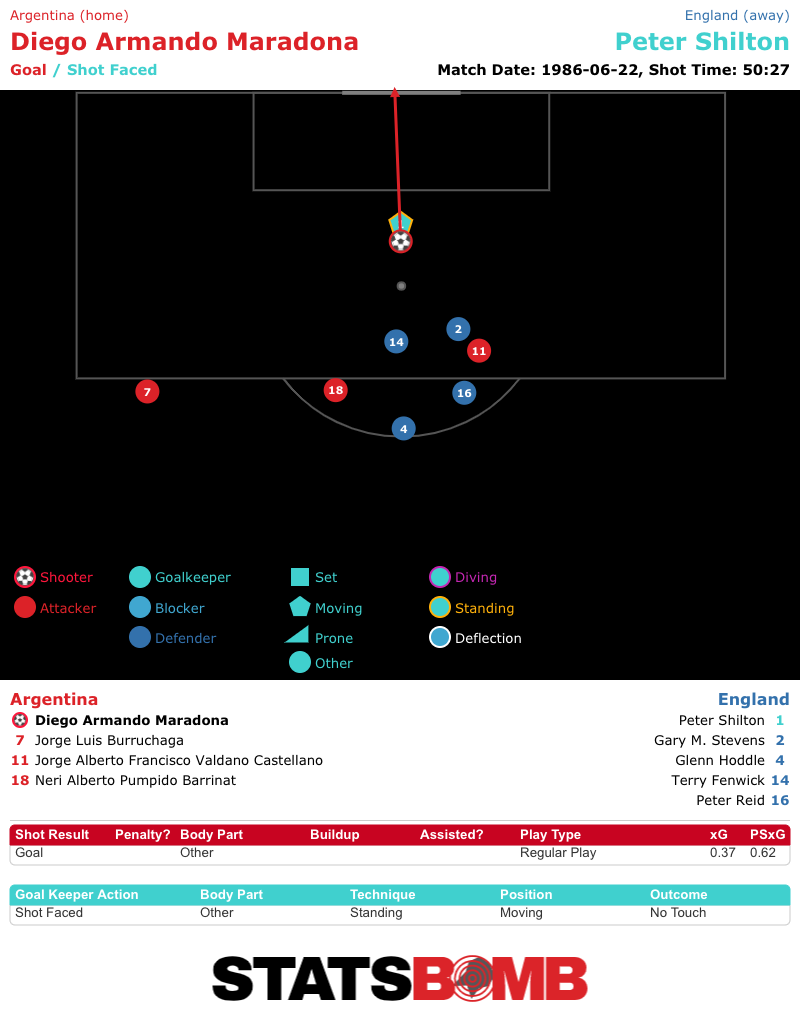

Of course, he also scored the two goals that led them to victory. The first... well, you probably know how that went down. Notice the body part: Other.

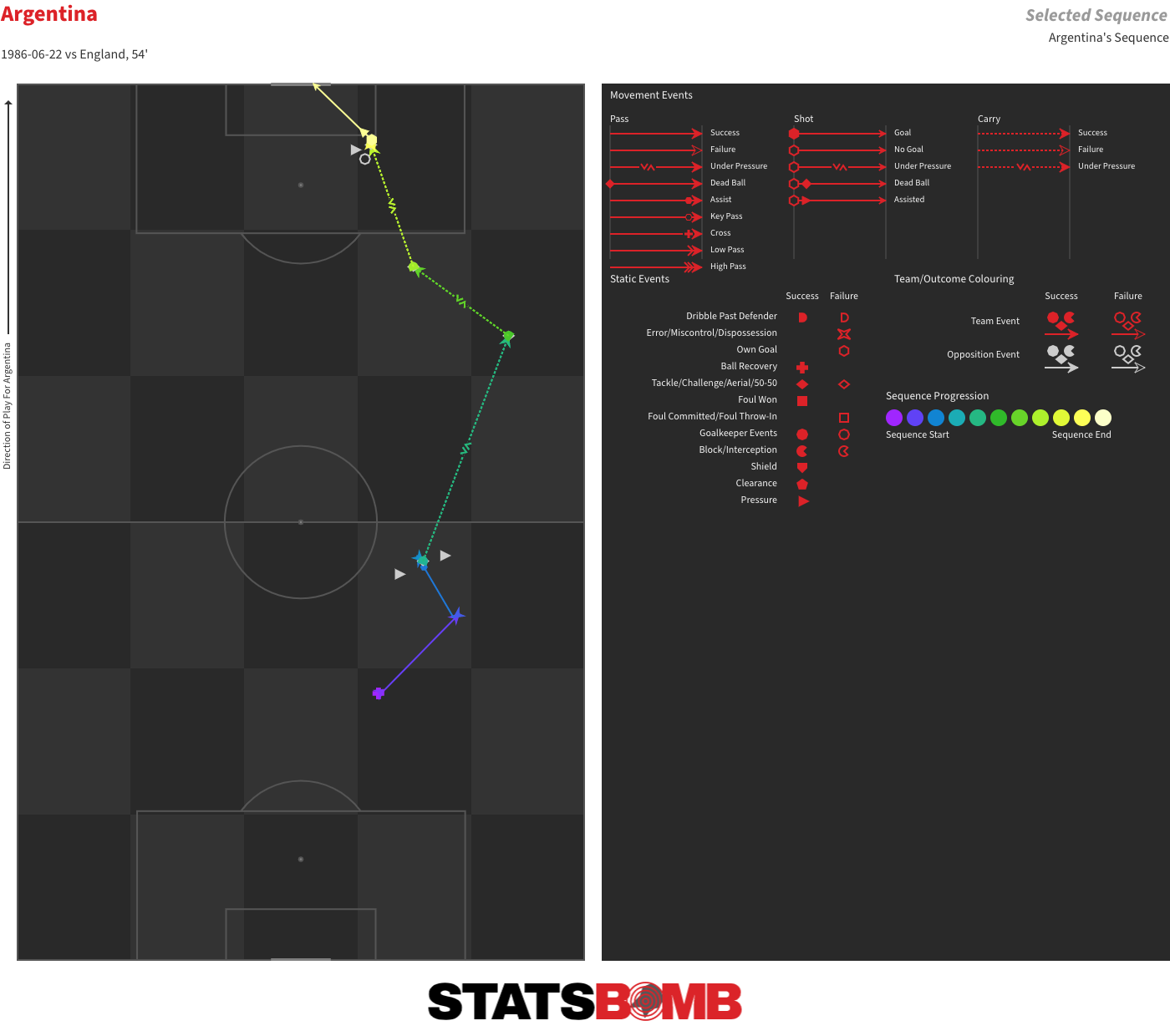

His second was one of the finest goals in the history of the sport.

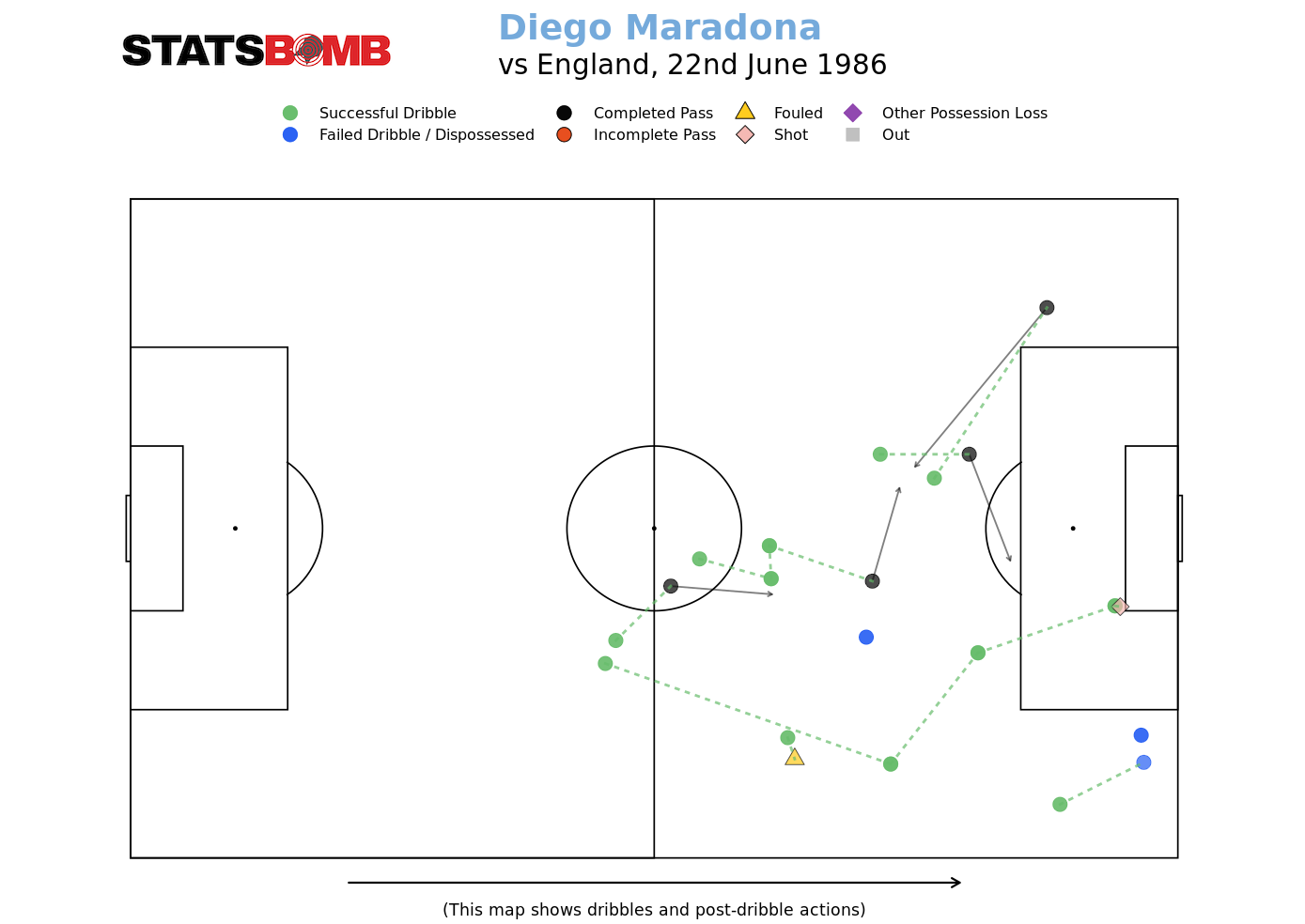

Maradona completed more successful dribbles (four) on the run leading to that goal than over 95% of current-day, big-five-league attacking midfielders and wingers do over the course of a full 90 minutes. On the day, he completed 12 of his 14 attempted dribbles. Whenever he picked up the ball and ran with it, England were unable to stop him.

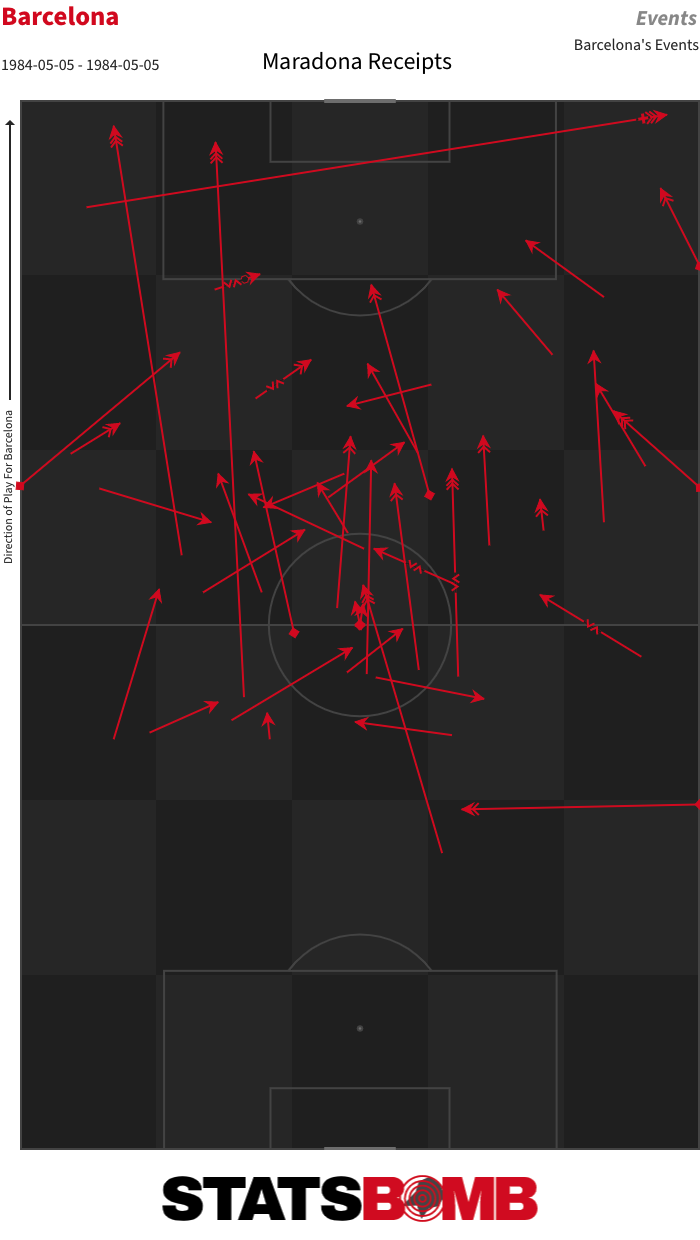

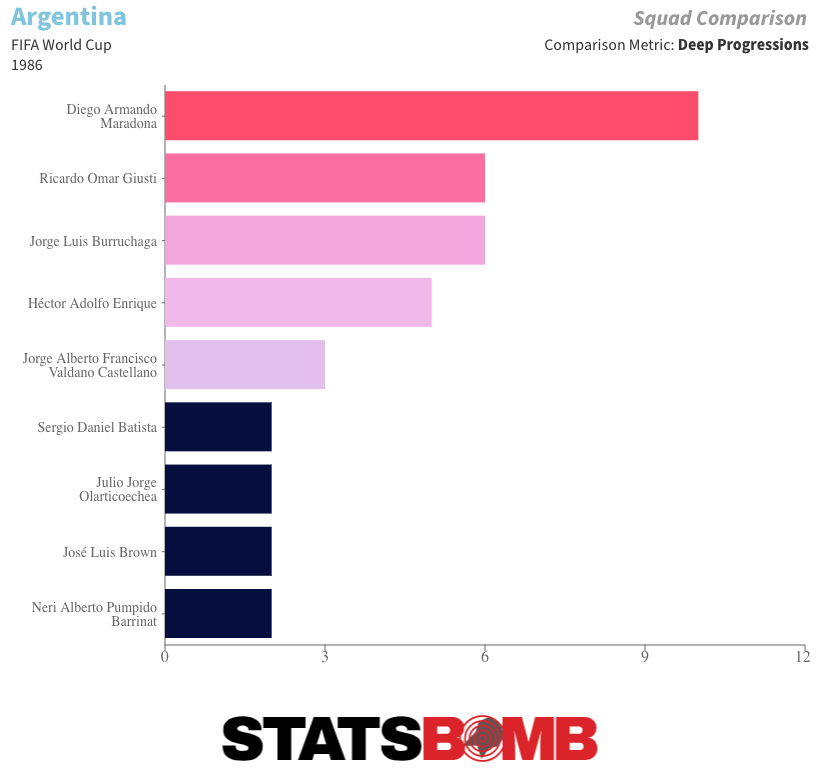

Maradona was relentlessly positive throughout, consistently seeking to move forward off the pass, dribble or carry. Not only did he provide pretty much all of Argentina’s attacking output, he was also the player who most often moved the ball into the final third.

There were some good players on this Argentina team, many of whom were successful at a continental level in South America or had already or would soon earn moves to Europe. Coach Carlos Bilardo also introduced a neat formational quirk, switching to a 3-5-1-1 shape he had previously experimented with for the final three matches of the tournament.

This will, though, always be remembered as Maradona’s World Cup. From the data we have available from this match, it is difficult to argue against the idea that he took on a greater than normal level of responsibility in this team -- a level of responsibility that is almost impossible to replicate in the hyper-active modern game. The second match in our system that falls within Maradona’s peak is the second leg of Napoli’s triumph over Atalanta in the final of the 1986/87 Coppa Italia -- one that confirmed their domestic double that season.

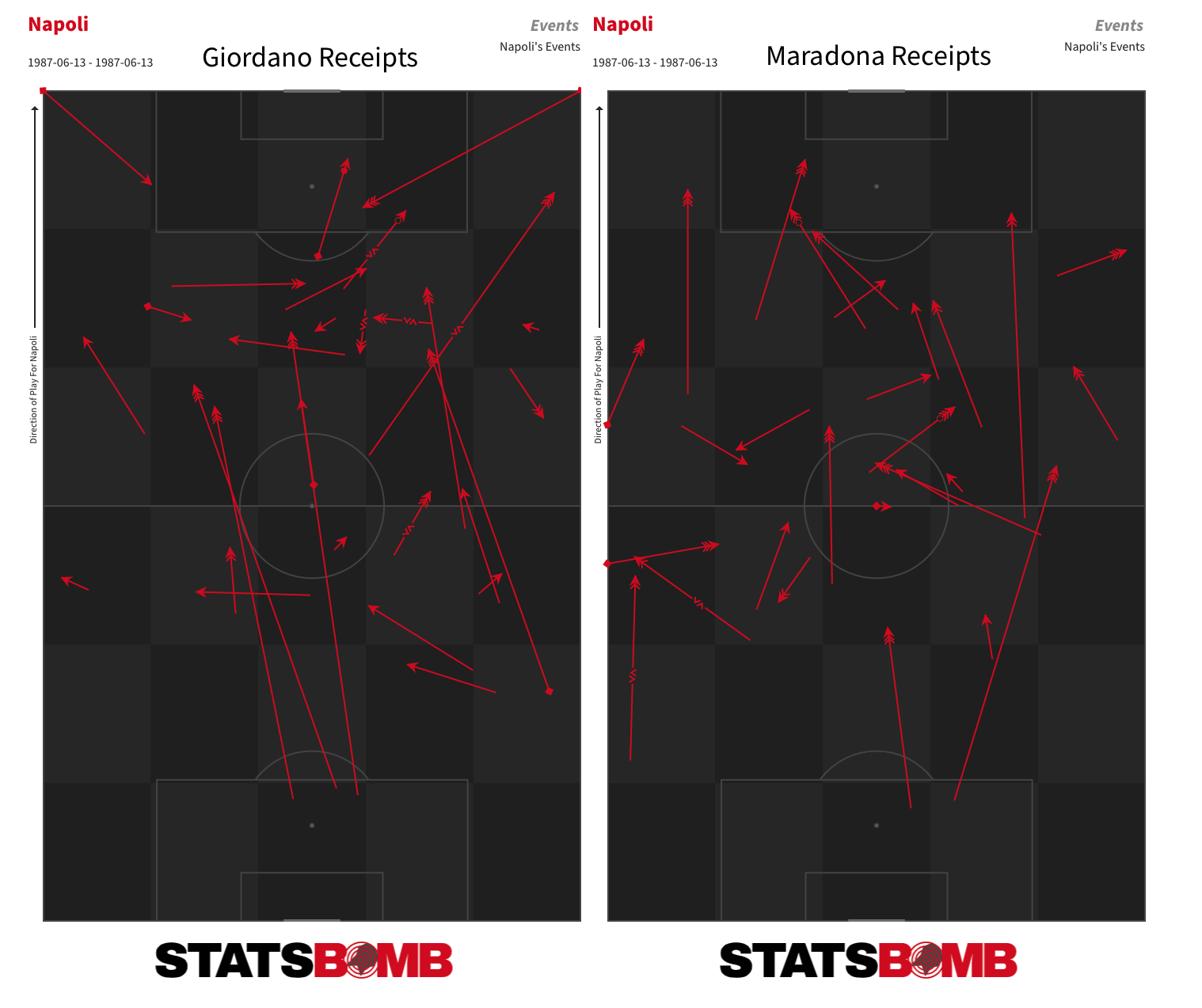

This is probably less representative than the England match. Napoli were already 3-0 up from the first leg, so there was little need for him to so aggressively carry the team on his back. Again, though, as with Jorge Valdano and Argentina, he benefits from having another forward alongside and ahead of him to act as both a primary reference point and an upfield runner. The large majority of the long central passes are aimed up to Bruno Giordano. The longer balls Maradona receives are into the channels, and he otherwise involves himself where he fancies, instead of being limited to a fixed starting point.

Mature Maradona

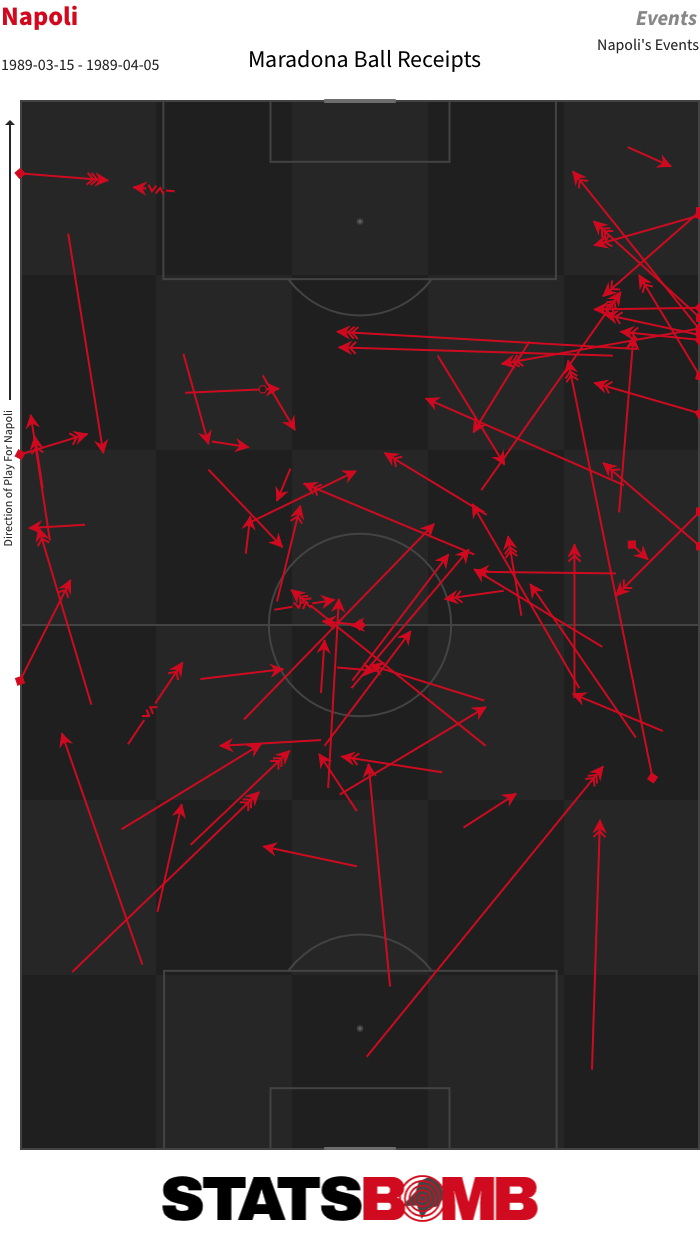

The final two matches we have recorded are both from Napoli’s successful campaign in the 1989 UEFA Cup: the 3-0 win over Juventus in the second leg of their quarter-final and the 2-0 victory over Bayern Munich in the first of their semi-final. Maradona is only 28 at this point but arguably just 18 or so months away from the end of his serious top-level career.

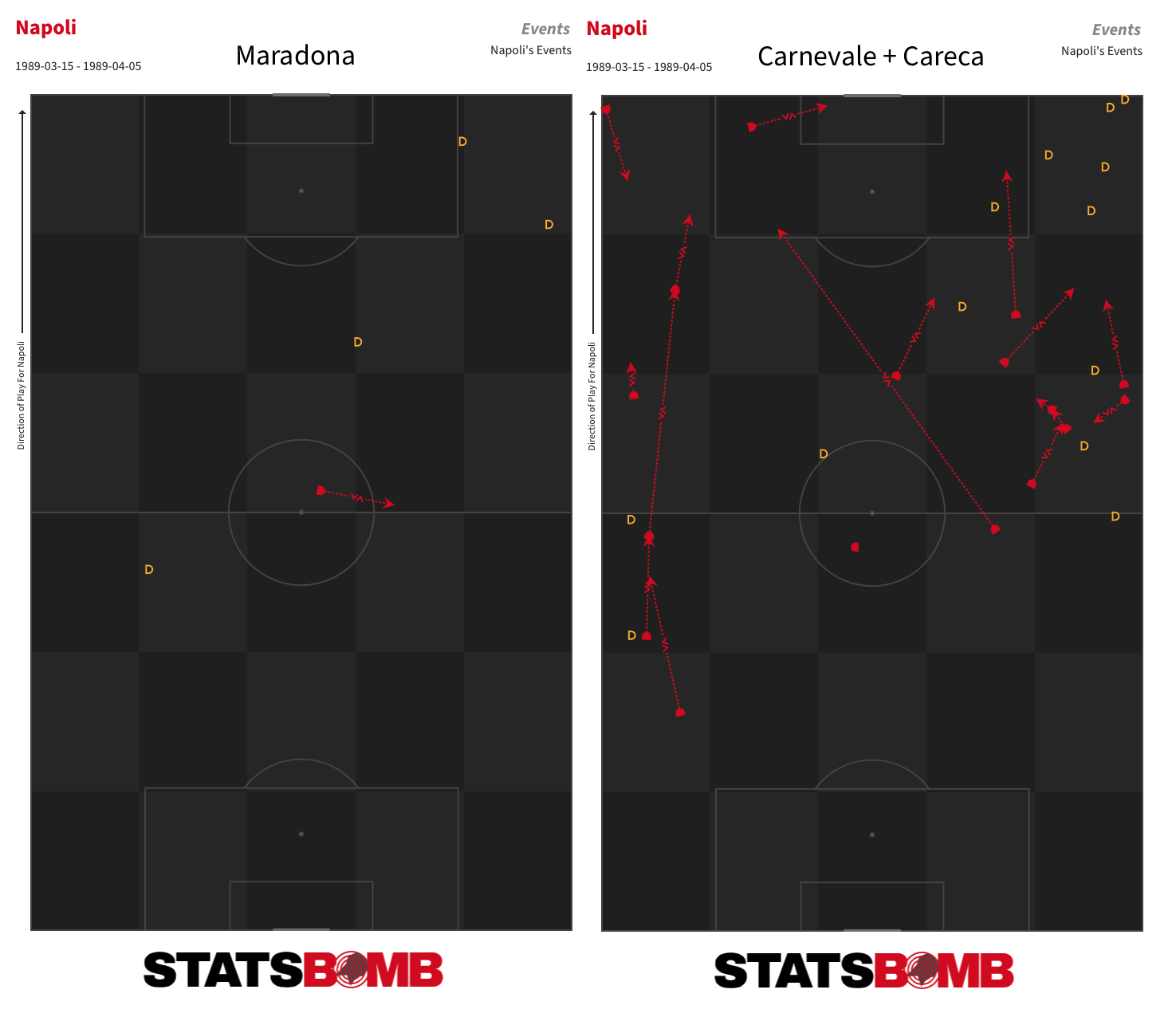

They display a Maradona who is still decisive but in a different way. He is much less reliant on his dribbling. After 12 attempted dribbles and seven successful ones for Barcelona against Athletic in 1984 and his bumper load against England two years later, he attempts only five dribbles and completes just one in these two matches in 1989. Andrea Carnevale and Careca do the majority of the dribbling on this Napoli side.

That isn’t to say that Maradona wasn’t still capable of game-changing dribbles, as his solo run to set up Claudio Cannigia for Argentina’s late winner against Brazil in the last 16 of the following year’s World Cup would attest, but he had certainly begun to ration them.

This later stage Maradona is much more likely to combine with teammates to advance upfield. Across 1984 and 1986 his ratio of passes to dribbles and carries fell in a range between 32 and 34%; across these two 1989 matches, it has increased significantly to 51.03%. He receives the ball more frequently in deeper areas.

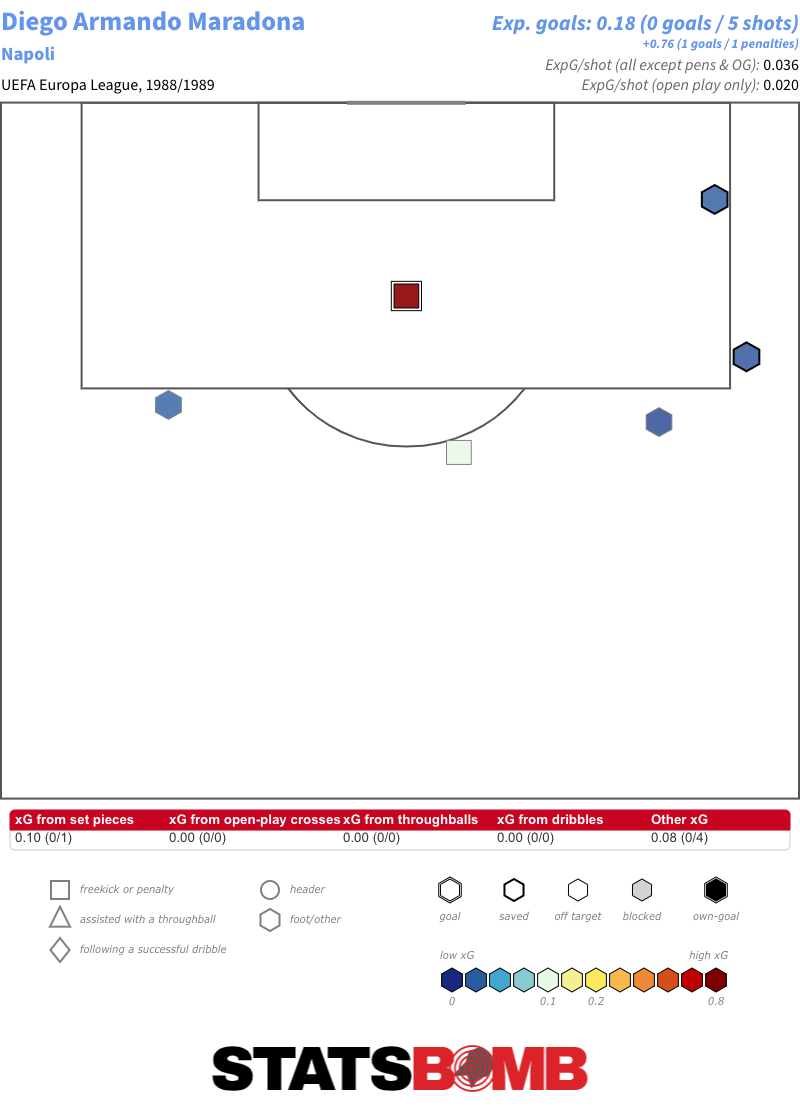

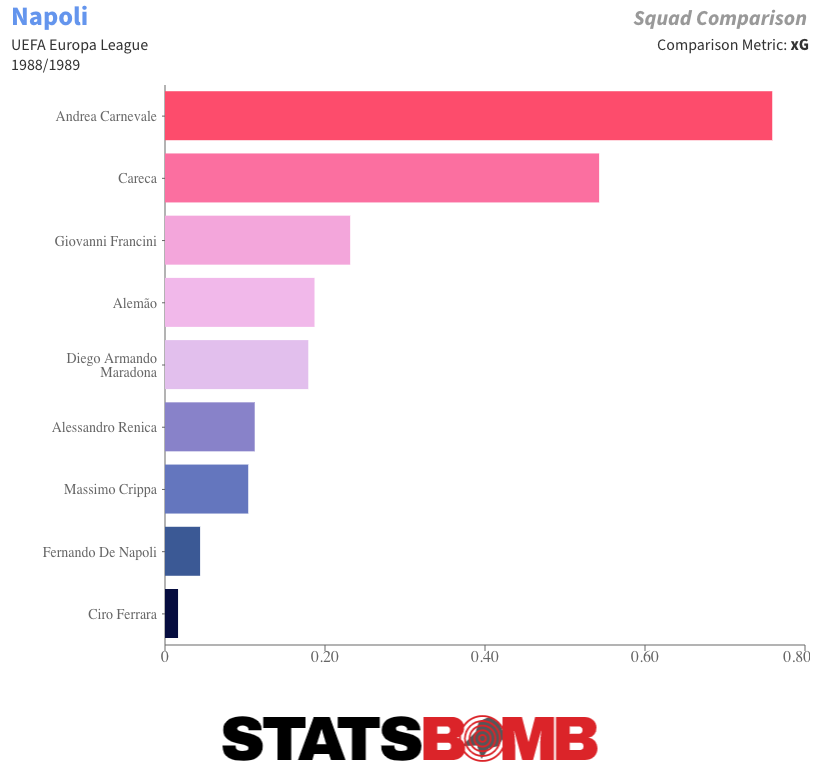

We see a Maradona whose output has tilted towards ball progression and chance creation. No one moves the ball into the final third more often or creates more chances for teammates than he does over these two matches. While he does take five non-penalty shots, joint second on the team, they are all from speculative positions, and he only twice touches the ball inside the penalty area over the course of the two matches.

Careca and Carnevale both accumulate far higher expected goals (xG) totals.

Maradona had been the club’s top scorer in each of his first four seasons at Napoli. In this campaign, Careca took that honour, with more than double Maradona’s total, while Carnevale also scored four more than Maradona’s sum of nine. It is, though, worth mentioning that the following season, in which Napoli claimed their second and last league title with Maradona, he returned to the top of the scoring charts.

Classic Games: Ronaldo at his peak, Inter against Lazio, 1998 UEFA Cup Final

Throughout the 1990s, the UEFA Cup was a favourite hunting ground of Italian teams, who took home 8 out of 11 trophies, and accumulated 14 total appearances in the final of the competition.

The 1998 UEFA Cup final between Inter and Lazio was the fourth - and so far the last - occasion in which two Italian teams competed for the trophy, a worthy epilogue to a season that has marked, even in controversy, the history of the two clubs and of all Italian football. At the beginning of that campaign, Massimo Moratti, in his third season as Inter's president, bought Ronaldo from Barcelona for the record sum of 50 billion lire. The previous season, Ronaldo had been Pichici with 34 goals and had scored a total of 47 goals in 49 games (or, if you prefer, 0.91 goals for 90, penalties excluded). The number nine of Moratti's dreams finally signed for a team, which could also count on a young Javiér Zanetti, Youri Djorkaeff and striker Iván Zamorano, among others.

Defender Taribo West, midfielders Diego Simeone and Benoît Cauet and winger Francesco Moriero also became Nerazzurri players that summer too. And finally, Moratti purchased also a 21-year-old Uruguayan fantasista with chubby cheeks and bowl-shaped hair, who made his debut 20 minutes before the final whistle of the first game of the season against Brescia, and overshadowed Ronaldo with two goals from a remarkable distance and bewitched his president with an irrational love. He was El Chino Álvaro Recoba.

For the managerial role, now left vacant by Roy Hodgson, Inter appointed Luigi Simoni, known as Gigi, unemployed after the end of a difficult relationship with Napoli president Corrado Ferlaino. He was a coach who still believed in rigid man marking and the use of the libero.

The Nerazzurri started off with 3 wins in the league and took the lone lead in Serie A, keeping it until match-day 17, when they were overtaken by Juventus, perhaps the strongest team in Europe at the time and not surprisingly a Champions League finalist.

The head-to-head with the Bianconeri continued until the direct clash at the Delle Alpi on April 26th, decided by a goal by Alessandro Del Piero, but, inevitably, also by a controversial body check between Mark Iuliano and Ronaldo, an event that became perhaps the most debated refereeing decision in the history of Italian football.

Moratti and Ronaldo's Scudetto dreams vanished with the final whistle and Inter were left to concentrate on the UEFA Cup, where they had reached the final, after a semifinal with Spartak Moscow, decided by two 2-1 wins and above all by Ronaldo's double in Russia.

The other finalists were Lazio; a team that had thrashed the Nerazzurri 3-0 at the end of February and who had held title aspirations of their own deep into the season before, before a very bad final run of results, which saw the Biancocelesti lose at the Olimpico to Juventus and collect just one point in the last six games, eventually dropping to the 7th place in the standings.

Like Inter, Lazio had strengthened considerably behind the will of their owner Sergio Cragnotti, who had entrusted the team to Swedish coach Sven-Göran Eriksson. The former Sampdoria coach brought number 10 Roberto Mancini from Genoa, while the club snatched Vladimir Jugović and the prodigal son Alen Boksić from Juventus. The midfield was renewed with the arrival of Matías Almeyda, while the defence was bolstered with full-back Giuseppe Pancaro.

Among its ranks, Lazio also included the elegant 21-year-old defender Alessandro Nesta (whom Eriksson called the strongest player he trained at Lazio) and a 24-year-old Pavel Nedved, who was their top-scorer in all competitions--alongside Boksić--with 15 goals.

Though the league challenge was derailed, Eriksson retained the faith of Cragnotti and president Dino Zoff by winning the Coppa Italia against AC Milan, and laid the foundations for Lazio's 1999/2000 Scudetto. Their path to the UEFA Cup final was relatively straightforward and they arrived unbeaten and with just 3 goals conceded and 16 scored throughout the competition, beating Atlético Madrid in the semifinal.

By coincidence the day of the final, 6th May 1998 was also the date on which the club became the first Italian team to be listed on the stock exchange.

The game was held at the Parc des Princes in Paris, and was particularly important as a dress rehearsal of the 1998 World Cup that was just around the corner.

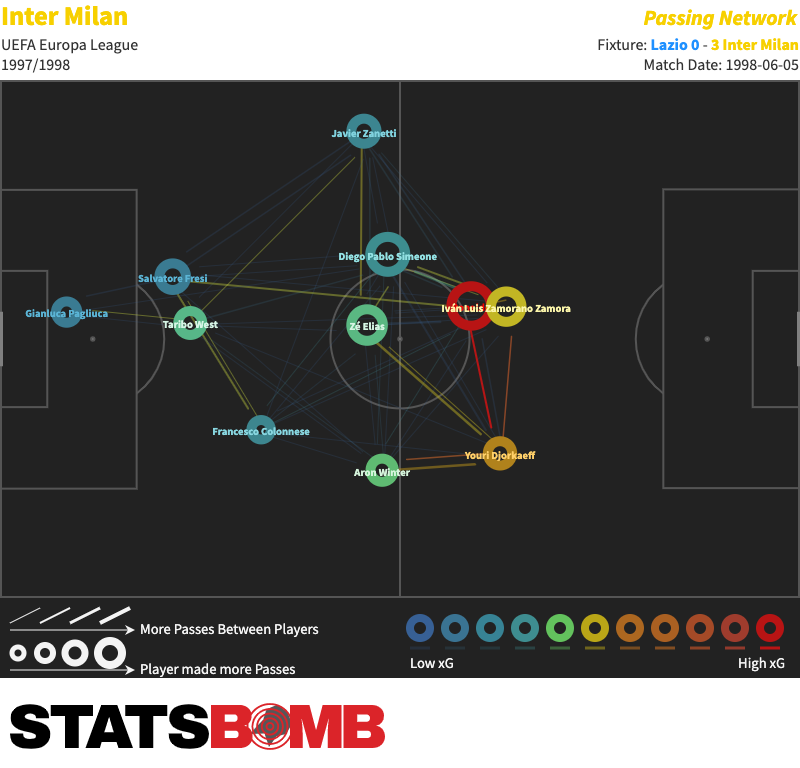

Simoni was forced to do without captain Giuseppe Bergomi and chose Salvatore Fresi for the role of the libero. West, Francesco Colonnese and Zanetti completed the defense in front of Gianluca Pagliuca’s goal. The four midfielders were arranged in a sort of diamond, with Zé Elias as the playmaker, Aron Winter and Simeone on his sides and Djorkaeff as the offensive midfielder. In attack, Ronaldo was paired with Ivan Zamorano.

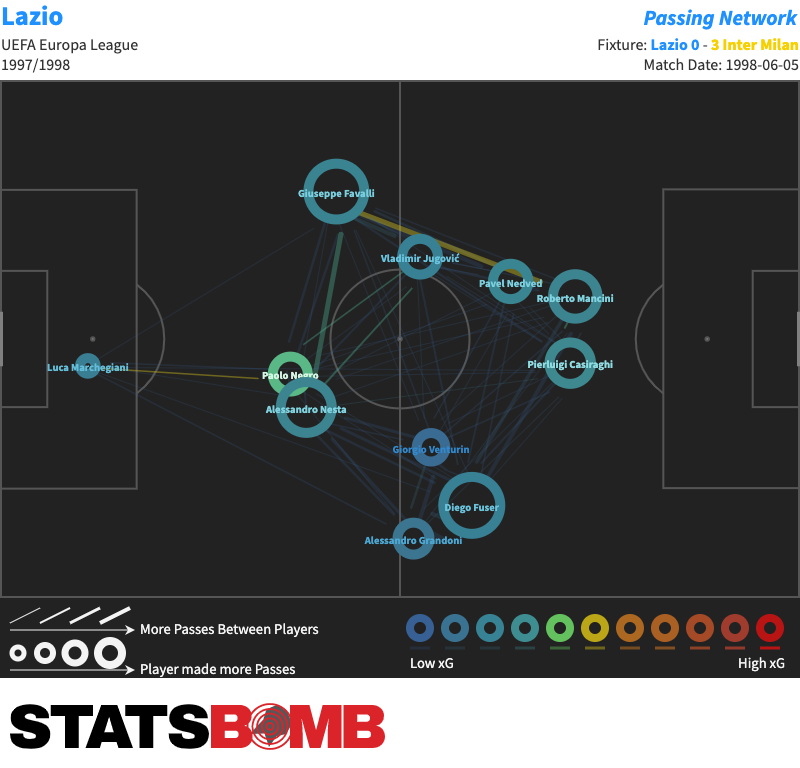

Eriksson was unable to call upon Boksić (who also missed the World Cup with a knee injury), and replaced him with Pierluigi Casiraghi. Alessandro Grandoni came in for Pancaro at right full-back. With Marchegiani in goal, the first line of the 4-4-2 was formed from right to left by the then Italy Under-21 right back, Nesta, Paolo Negro and Giuseppe Favalli. Giorgio Venturin and Jugović were the two central midfielders, with captain Diego Fuser wide on the right and Nedved on the left wing. Mancini acted as second striker behind Casiraghi.

The deadlock was quickly broken. Simeone, left without pressure by Lazio, delivered a long ball behind the defense to Zamorano for the first goal of the game. The mistake of Erikisson’s defense was quite clear, as defenders were neither positioned to set an offside trap, nor were they running backwards as would have been advised by the situation.

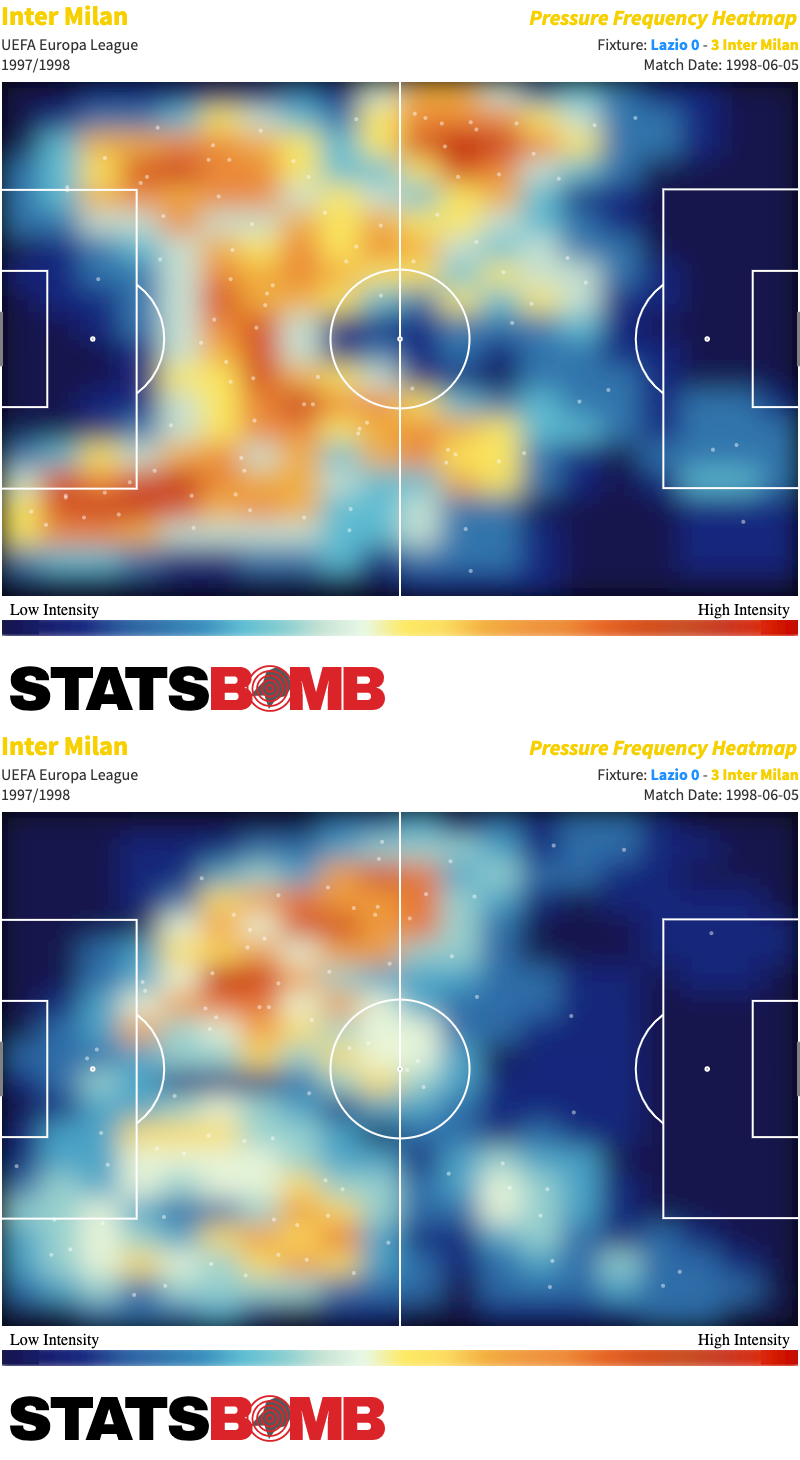

Both Inter and Lazio were two teams that were at their best when on the counter and after the 1-0 Simoni was very happy to leave the ball possession (63% to 37%) to his opponents. From the very beginning, however, the difference between the two coaches' defensive approach was also emblematic. Simoni's system of play was still strongly influenced by the mixed zone: in addition to the use of the libero, the man-marking applied by his team was rigid, so much so that the formation of Inter in the defensive phase was determined exclusively by the positions of the opposing players.

Without the ball, Fresi positioned himself behind the defensive line, with West marking Casiraghi and Colonnese with Mancini. Zanetti engaged a personal duel with Fuser right from the start, both defensively and offensively, while Nedved was marked by Winter, leaving Simeone and Zé Elias in numerical parity with Lazio's midfielders. Even in the defensive phase, Inter's formation was peculiar: Winter - who perhaps could have been a fullback today - offered a wide pass line, while Djorkaeff dropped on the right halfspace to balance their occupation of the field.

Eriksson, on the other hand, used a 4-4-2 with a zone defense, using a medium-low block in the defensive phase and without exerting particularly aggressive pressure on the opponent's ball carrier. There were moments in which Lazio compacted the two lines of 4 to reduce the space available on the side of the ball, but also those in which the Swedish coach decided to raise the pressing. In these situations, one attacker pressed the opponent's defender in possession and the other marked the closest pass option, while the midfield prepared to block passing lanes, with the aim of forcing a risky pass or a long ball.

During the offensive phase, Lazio used to rely heavily on its center forward, in this case Casiraghi, but Inter was also repeatedly looking for Zamorano. Reviewing the amount of long passes towards the two teams’ target men makes a certain effect and gives a clear idea of how much having a striker good in the air was important for almost all the coaches of the time, as well as how much football has changed since then.

Both Zamorano and Casiraghi probably had good strength in their aerial game and a trademark move in the header. However, the confrontation between the two was clearly in favor of the Chilean, who won 6 out of 10 aerial duels and assisted Zanetti’s goal with an headed pass, while Casiraghi came out as the winner only 3 times (33%), limited by West’s dominance on high balls (7 aerial duels won, 78% of the total).

If Casiraghi acted as the offensive focal point, Mancini would roam across the attacking front, looking for the combination with Fuser or Nedved, or alternatively to create dangers through dribbling or a first touch pass towards a running teammate. Even at 34 years of age, Mancini was still a useful player, but although he was second only to Nesta for touches in the game, during the match he was often neutralized by an excellent marking by Colonnese, whose performance was one of the keys to Inter's victory.

Although they had to overturn the result and thus control game with the ball, Lazio was a team built to play vertically. Nesta (134 touches) and Negro (92), rather than Venturin, were the players who controlled the rhythm of the game starting from the defense, deciding whether to accelerate with a play towards the strikers or to distribute the ball along the flanks. On the right side most of the responsibility for the progression of the game depended on Fuser, the Lazio player with the most dribbles (4) and passes in the last third (23), an throughout he did ran the inside channel, waiting for the overlap of Grandoni.

During the 2nd half the right back was also replaced by Eriksson with the more offensive Gottardi, perhaps to try to get to the touchline and cross with more consistency, as Fuser's movements on the inside attracted his marker Zanetti and left the left side of Inter's defense unprotected, where Fresi had to be the one to leave position intervene. On a couple of occasions Grandoni even had the time to receive the ball behind the defense, forcing the libero to save the situation with a desperate tackle. Nedved started wide on the left, but gradually moved inside the field, in part because of Winter's marking in the defensive phase, which saw him practically acting as the right wing back. Across the field, Jugović made similar movements.

Inter’s pressure heatmap in the 1st half (top) and the 2nd half (bottom)

Lazio came close to a draw in the first half, but Inter's defensive scheme, which bargained almost entirely on their superiority in individual duels, proved to be decidedly solid and more reliable than Eriksson's zone defense. Zamorano found another chance shortly after the start of the second half having beatne the offside trap, but it was a rare goal by Zanetti, perhaps the most beautiful and important of his career (alongside one in 2007/2008 against Roma) to double the Nerazzurri’s lead: a volley with the ball bouncing in his direction, which ended its trajectory on the top corner of the goal.

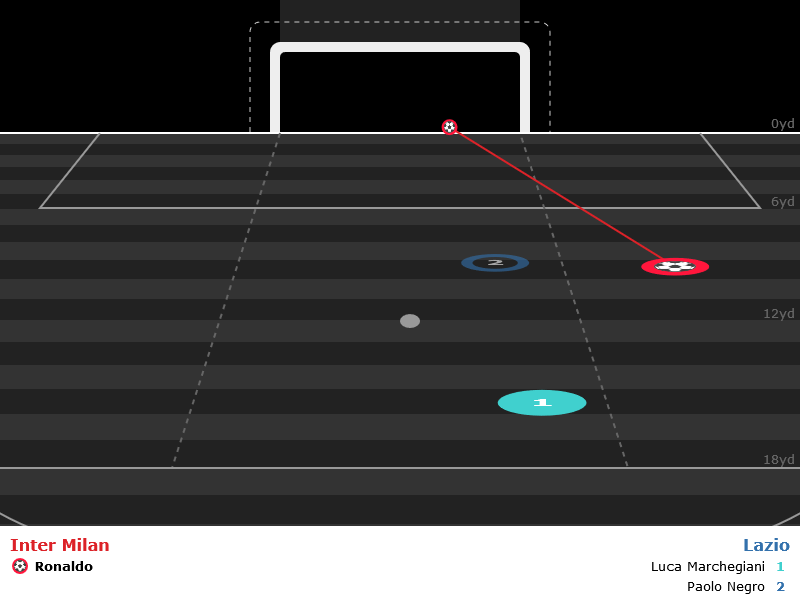

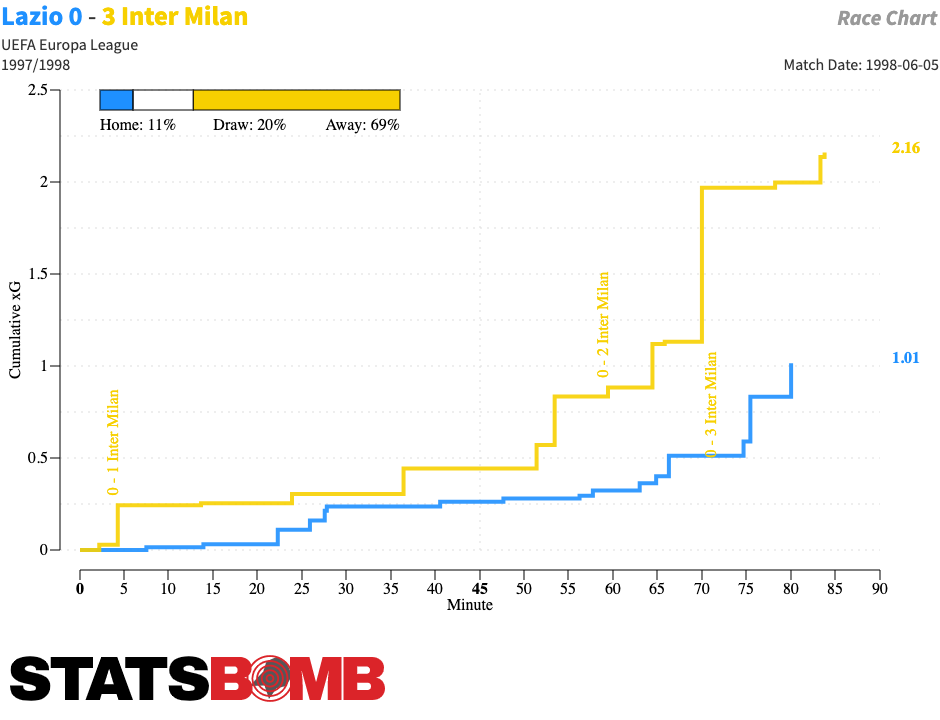

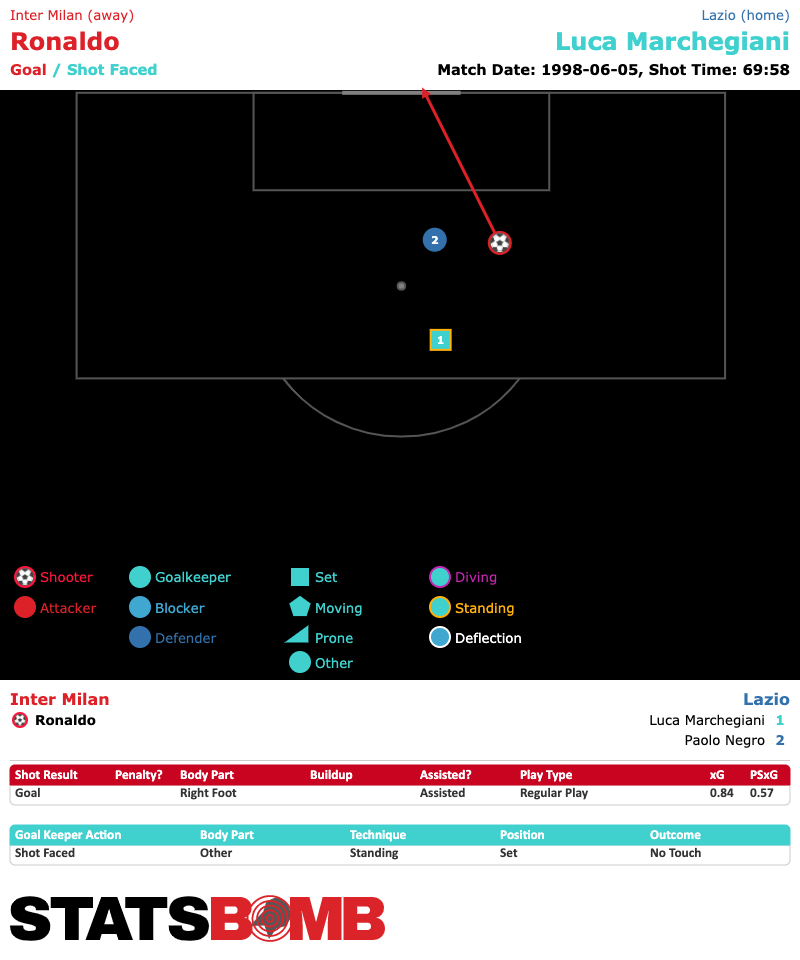

By now, the UEFA Cup was virtually on its way to Milan. All that was missing at that point was the Fenomeno’s signature on the trophy. And Ronaldo’s goal naturally arrived, when in the 70th minute he was served by Moriero, beat a close offside decision and scored to make it 3-0. An iconic run that ended with him dribbling past even Marchegiani.

The 90 minutes in Paris are illustrative of how Ronaldo was a unicorn before unicorns, a complete forward with a pioneering quickness that made him literally unplayable even in Italy, where the attention to the defensive phase – and it’s not a cliché - was much more accentuated than in the Eredivisie or La Liga. In 1998 Ronaldo was the future of football and his talents were timeless, he would be similarly feted today. We remember him as one of the best number nines of all time, but on that occasion, wearing the number 10, he played as a second striker, supporting Zamorano and helped the team in all areas of the pitch, despite having a talent several orders of magnitude greater than any of his teammates. The amazing aspect of this performance, which perhaps wasn't even the best in the competition compared to the semi-final against Spartak, was the magnetism he emitted.

Ronaldo eluded Gottardi twice and on the second occasion he sat him down with an “elastico” in one of the 5 dribbles completed in the final.

Ronaldo was Inter's mainstay in that match, being not by chance the player with the most touches or the most decisive player in chance creation. With only 3 shots, he accumulated 0.91 xG but if we examine his overall involvement with xG chain (xGc), a metric that measures the xG of all the actions in open play in which a player is involved, the figure rises even to 1.71 xGc (out of 2.16 xG overall).

If the 0.91 xG shows his ability to be in the right place at the right time, the remaining part of the metric is an indirect measure of the gravitational attraction that Ronaldo exerted on his opponents. The Brazilian was the "Phenomenon" but also the great facilitator of Simoni's Inter, able to generate superiority and consequently to open spaces and to create opportunities for his companions either directly or otherwise. This was an unique feature, which can only lead to an immediate comparison with Lionel Messi, perhaps the only other player able to attract opponents as if he were a celestial body.

We could dismiss the Paris final as the last triumph of an obsolete and reactionary football, almost a revamp of the mixed zone, on pure zonal defense and Eriksson's modern 4-4-2. But it would be a superficial assessment that would overlook how Simoni's Inter system, regardless of its ideological roots, was built to maximize Ronaldo's futuristic talent, without leading to tactical imbalances or bad moods in the locker room. A concept that transcends footballing eras and remains very relevant even in the age of "super teams" and "unicorns". And that explains how the gentleman coach of Crevalcore has remained one of the most beloved managers in the history of Inter, also for his undoubted bond with Ronaldo. That evening, in addition to the UEFA Cup, the Brazilian also won the bet to cut his coach's hair, shaving him with an electric razor.

Searching for a Replacement for Jadon Sancho

Football is in gridlock at the moment. Still, rest assured the football industry doesn't simply stop existing. Instead, clubs are already planning ahead for the time after the current standstill. Borussia Dortmund might have to do tackle that time without Jadon Sancho. The young Englishman could go back to his mother country and leave a large gap that has to be filled.

What defines Sancho?

Generally, the attributes of the 20 year old are well known. He has developed into one of the most promising wingers in Europe in short time. Sancho disposes of the classic qualities of a dribbler on the flanks: He's able to move into one-on-one-duels diagonally from the sideline, sprint toward the goal line or create gaps on the perimeter of his field of vision by moving towards the inside. Sancho is agile and skilful on the ball.

Moreover, his is a very aggressive playing style. His risk-management is oriented in such a way that he'll accept loss of possession with a view to a potential gain in attacking output. That's why he gives away the ball quite frequently, but also why he's usually taking aim from a good position for scoring opportunities. Altogether, he shows a relatively large presence in the penalty area. He doesn't just move on the flanks around the box, rather orientating his game towards getting into the dangerous zones.

In that, Sancho doesn't resemble someone like Franck Ribéry, who developed his danger on the goal mainly from the wing, rather he moves into positions in the half-space. Generally, Sancho's game from the half-space is somewhat underappreciated. From there, he usually interacts with other attacking players of Dortmund's – such as Marco Reus or Julian Brandt. He frequently looks for a short pass to Reus or, as of late, Erling Håland, in order to immediately move into a position for a flick-on or a lay-off. He moves faster than his opponents, who have to lose sight of him for only a split-second to no longer be in a position to step in.

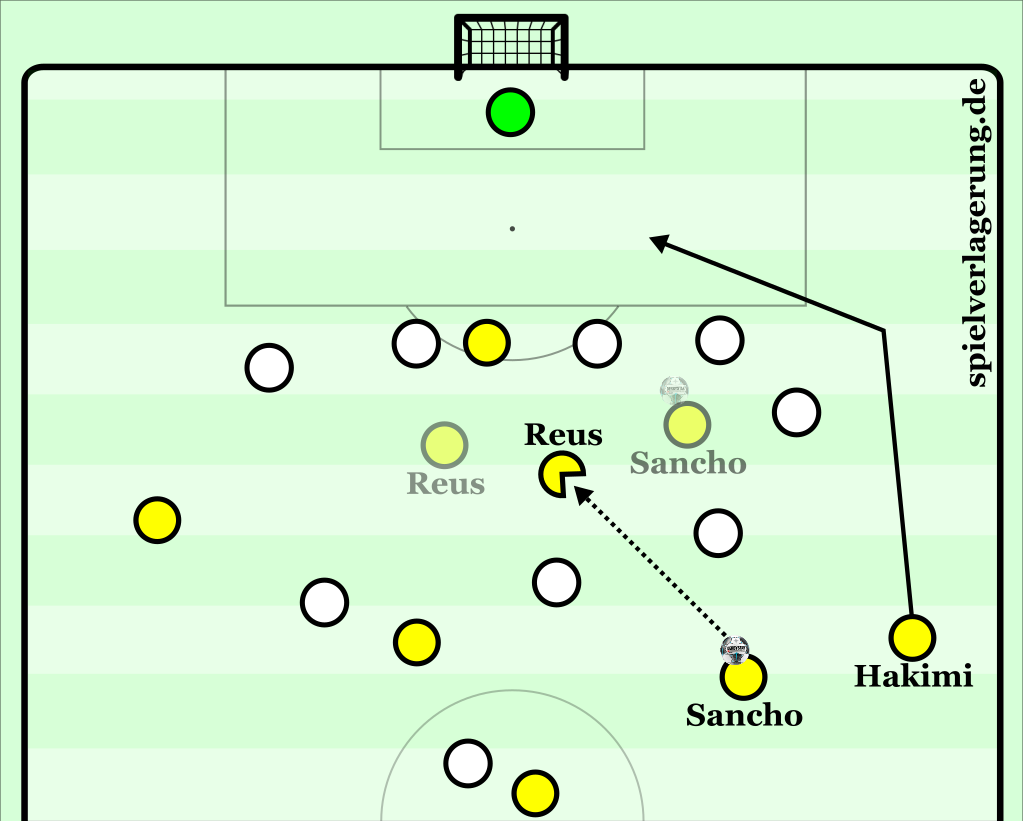

At BVB, Sancho functions so well also because he doesn't have to constantly run up and down the touchline. His work against the ball is rather sloppy and at times even clumsy. Longer runs without the option of getting to the middle diagonally are also not his strong suit. He's at his best in terms of sprinting when the team are running an open counter-attack. At Dortmund, Sancho is helped by the fact that he has flank-runners around him in Achraf Hakimi or Raphaël Guerreiro. Especially Hakimi, with his propensity to make runs behind the defensive line in the final third, fits well with Sancho's presence in the centre, since the focus will be on the Englishman, who can still serve up Hakimi through the gaps thanks to his agility.

Typical situation: Sancho attacks a defending side, that is backtracking, through the half-space. He draws the attention of the two outside defenders on his right, allowing Hakimi to make a run behind the backline.

What does the Replacement Need to Bring to the Table?

Going by the attributes discussed above, BVB should not just look for a strong dribbler on the wings. There are a few of those in the Bundesliga and other parts of Europe. But, especially in a 3-4-3, BVB don't necessarily need someone for the three-man attacking line who mostly feels at home on the flank. That's what strong runners on the wing-back positions, such as Hakimi, Guerreiro and Nico Schulz are there for. The potential signing of Thomas Meunier further highlights how Dortmund will upgrade in that regard.

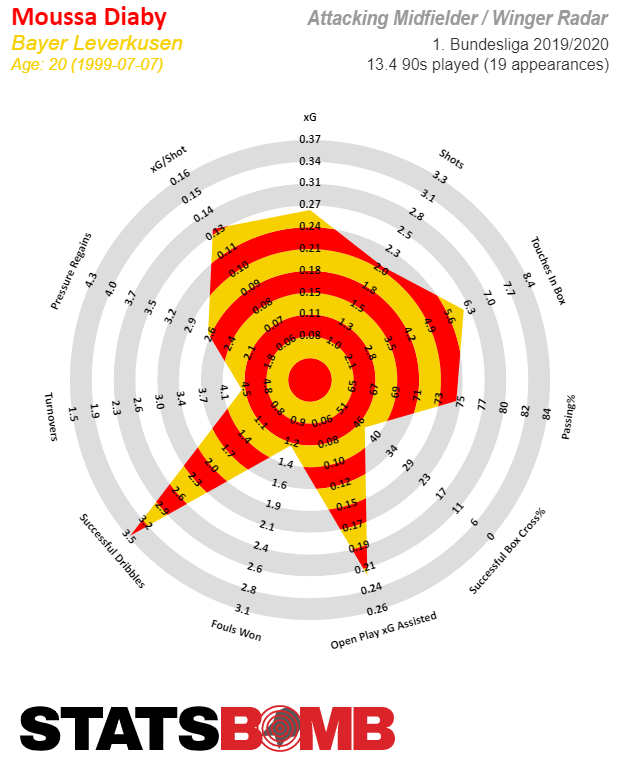

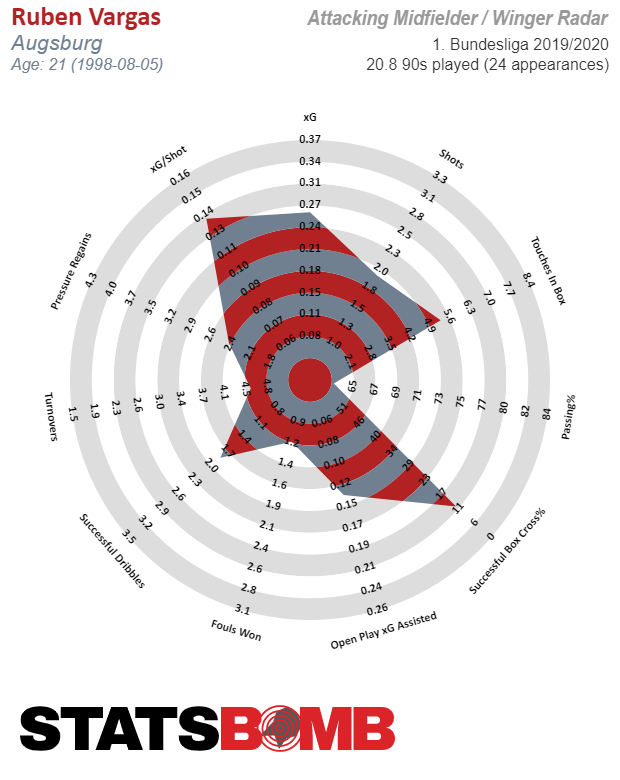

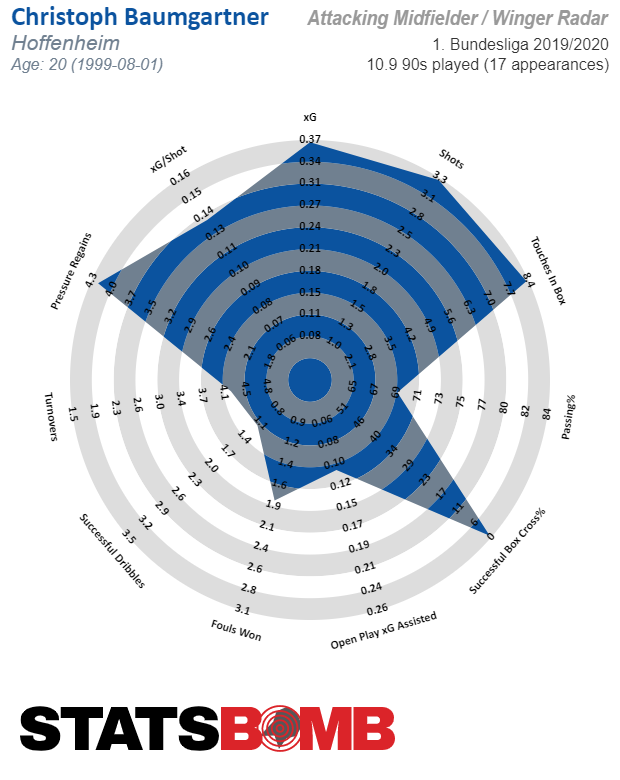

For this, we can use a "Similar Player Search" tool to analyse which Bundesliga players resemble Sancho during the current campaign. In that, we'll weight which values should factor into the comparison especially strongly and receive a number of interesting names in the category of players of up to 22 years of age who have played a minimum amount of 600 minutes – each with a percentage-wise correlation to Sancho. In declining order of correlation these are: Marcus Thuram, Christopher Nkunku, Kai Havertz, Dodi Lukebakio, Moussa Diaby, Josip Brekalo, Ruben Vargas, Amine Harit, Leon Bailey, Alphonso Davies, Marco Richter, Christoph Baumgartner, Rabbi Matondo, Javairô Dilrosun and Ismail Jakobs. Naturally, a number of candidates can be discarded for obvious reasons. Or does anyone think Davies will soon lace his boots for BVB? At the same time, we can highlight three interesting players.

Candidate 1: Moussa Diaby

I might have suggested Diaby as a fairly obvious option without looking at stats. The Bayer Leverkusen wingman is not yet as consistently successful in his actions as Sancho – particularly in the opponent's box – but he combines agility and skill on the ball with a clear push towards the goal. An added benefit is that he's not being used as a clear-cut winger in Peter Bosz's system, rather having the freedom or even task of positioning himself in the half-space or playing into these zones. Diaby doesn't just attack defensive lines from the flank, but also penetrates them in positional gaps. With that, he could fit into Lucien Favre's system well. There shouldn't be any doubts concerning his general footballing and athletic qualities at any rate.

Candidate 2: Ruben Vargas

Vargas of FC Augsburg is harder to judge than Diaby seeing as he can profit from his team's playing style only to a limited extent at the moment. FCA is one of the Bundesliga teams with a small amount of attacking productivity in terms of shots on goal. Vargas can hardly change that situation by himself, but maybe he doesn't have to. For especially in the transitional game, he develops a respectable penetrating power in spite of it all, which is clear to see even in isolated situations. Because of that, the motto when talking about Vargas has to be: If someone can have so much attacking presence while playing in weaker surroundings, they surely must shine all the more with better teammates. The pitfall here is that there might be an error in reasoning. Because Vargas does also profit from Augsburg's transitional football, in that he has more freedoms and only rarely has to successfully convert detailed actions. Vargas is a candidate that makes it obvious how it's not so easy to judge a player's performances in relation to the quality of his team and in the context of a potentially different playing style in the future.

Candidate 3: Christoph Baumgartner

The mention of this 20-year-old TSG Hoffenheim player may come as somewhat of a surprise. Baumgartner is widely regarded as the biggest talent in the Bundesliga squad of the team from the Kraichgau in south-west Germany. However, he was handed round from position to position this season – very much in keeping with the style of head coach Alfred Schreuder. Between right-sided wing-back and left-sided supporting striker, he's played in almost every position already. Baumgartner, in any case, is a player who shines brightest as a No. 10 or as an attacking winger. His aggressive and at the same time agile playing style in the final third somewhat resembles Sancho's in some aspects. Of course, Baumgartner doesn't have that special something while dribbling whatsoever. Should Dortmund be looking for a young candidate, however, who can factor into the plans both as a disguised winger and a potential back-up for Reus, Baumgartner could become a possibility. Similarly to Sancho one and a half years ago, Baumgartner is still a bit inconsistent in his decision-making. Still, the appearances he's made in the Bundesliga have shown in time that he's developing rapidly.

Whoever Dortmund sign after Sancho, it won't be an equivalent replacement from day one, but rather someone with the required potential to in his way shape BVB's attack in the short- and especially medium-term. That was already the case with Sancho. And that turned out to be a lucrative model for Dortmund both in sporting and monetary terms.

StatsBomb LIVE Podcast: The 2021 Contracts. Stick or Twist?

SB Labs: Camera Calibration

This article is written by the CV team at StatsBomb. In it, we will cover the technical details of the camera calibration algorithm that we have developed to collect the location of players directly from televised footage

Introduction

Camera calibration is a fundamental step for multiple computer vision applications in the field of sports analytics. By determining the camera pose one can accurately locate both players and events in the game at any time point. Furthermore, increasing the accuracy of the camera calibration will in turn increase the accuracy of any advanced metric derived from the collected data.

One of the applications where camera calibration is essential is player tracking. In order to tackle this problem some companies have developed a multi-camera system that records the entire football pitch. This approach has the clear advantage of allowing for accurate location of all the players in the field. However, the deployment and maintenance of these systems can be quite expensive and its applicability is limited to stadiums where the customized cameras were installed, thus requiring specific agreements with clubs.

An alternative, much more scalable, approach consists of collecting data from broadcast video, which is widely available. However, from a technical point of view this is a much more challenging problem since we cannot rely on stationary cameras. Instead, it is necessary to perform a registration between the playing surface in the video and a template model.

In the remainder of this document we present how StatsBomb is approaching the problem of camera calibration from broadcast video. We describe the methodology we are following and the results that we’ve had.

Data Preparation

Our objective is to fully automate the camera calibration. For that purpose, we have deployed a system to collect data from which we can create a training dataset composed of frames at different locations and their ground-truth camera pose. The aim is to collect a wide range of camera poses that cover all locations within the pitch. This has been achieved through the following steps:

(1). Mechanical Turk

In order to rapidly collect data to train our models, we have created a platform that allows us to manually label pitch markings from multiple pitch locations. Camera calibration usually relies only on paired points between the images to register, requiring a minimum of four pairs of points. The corners of the penalty box are examples of easily recognizable points. However, depending on the camera angle, there might not be enough recognizable points present in the frame to retrieve the camera pose. In order to overcome this limitation, the application we have developed allows our collection team to manually outline and label all pitch lines present in the frame.

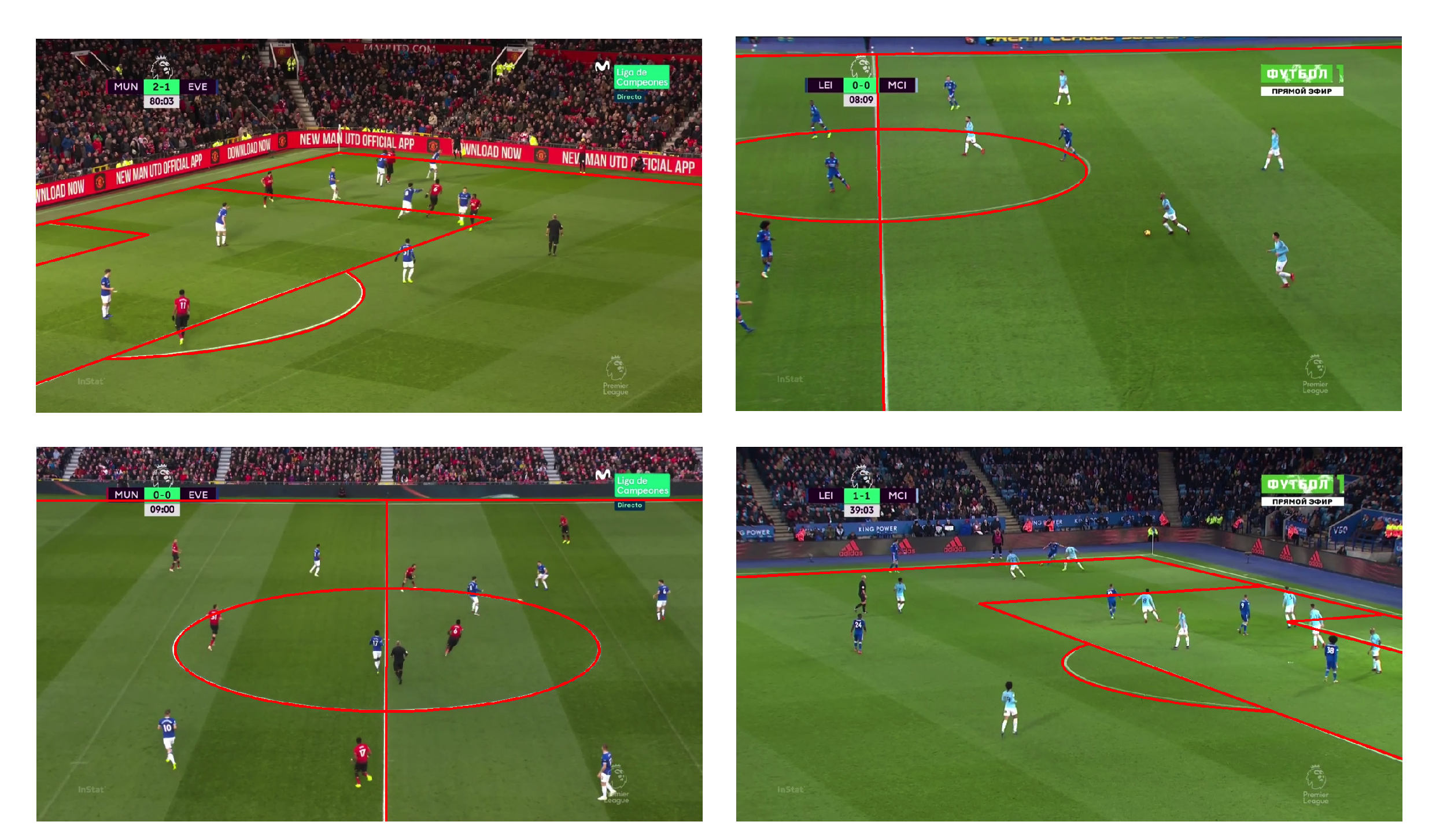

Figure 1. Four different camera angles covering different locations of the pitch. The labelled information marked by our collection team is displayed, including straight lines, circles, and special keypoints, such as the penalty spot. You can see that the labels are not perfect, but don’t worry since this will be fixed in the next step. Also, this data is just for training our machine learning models, and any imperfections here will not impact the quality of the data we give to customers.

(2) Homography estimation from manually labelled data

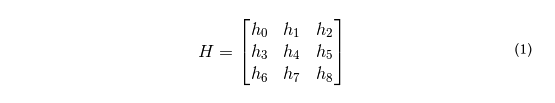

In projective geometry, a homography is defined as a transformation between two images of the same planar surface (1). Assuming the cameras used to record football games are well characterized by the camera-pinhole model, retrieving the camera pose is equivalent to determining the homography between the observed pitch within the frame and a template. Mathematically, the homography is described by a 3x3 matrix:

Luckily, although matrix H has 9 elements, there are only 8 degrees of freedom, and we make some assumptions about the camera to reduce the number of degrees of freedom even further. Then, we use our labelled data to estimate the homography for each image.

Figure 2. Four different camera angles covering different locations of the pitch. The projected pitch template using the estimated homography is displayed. These images and lines may look nearly identical to figure 1, but they come from the computer understanding where the camera is relative to the field, rather than just lines drawn on an image. Note that the slight imperfections in the types of images from figure 1 have been corrected after this stage.

Camera Calibration

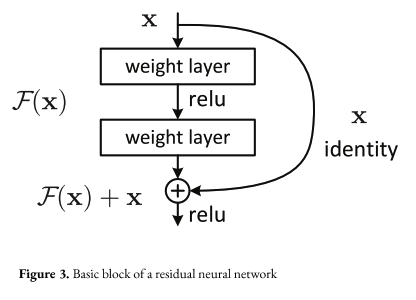

Having the aforementioned data, we can now use supervised learning techniques to train a model that allows us to retrieve the camera pose from a given frame. The model we use is based on a ResNet architecture (2) that is often used for recognizing objects in images. However, it is necessary to train the network to find football pitches instead of dogs and cats. We do this using back-propagation and the Adam optimizer (3).

Figure 4. Sample of the camera calibration method developed at StatsBomb. The pitch template is projected in red using the estimated camera pose.

Conclusions

Thus far we have only deployed our model for shots. We have focused on shots to continue improving the quality of the data that goes into our xG model. By more accurately locating the shooter as well as the goalkeeper, defenders, and other attackers, we continue to have the best data in the industry. By the start of next season we will have rolled out a model to accurately calibrate the camera for all events. This could unlock the ability to have freeze frames for all events, player tracking, and more. The timeline for these features is still in progress and is dependent on customer demand, so let us know what you’re interested in! In this report we have presented how we have tackled the problem of camera calibration at StatsBomb, providing details about our approaches to both data collection and model training. We continue to explore ideas aiming at expanding the scope of our models and improving the current results.

References

(1) Hartley and Zisserman, “Multiple View Geometry in Computer Vision”, 2003, Cambridge.

(2) He et. al., “Deep residual learning for image recognition”, 2015, arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/1512.03385.

(3) Kingma et. al., “Adam: A Method for stochastic optimization”, 2017, arXiv: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1412.6980.pdf.

The StatsBomb Interviews! Ted Knutson meets... Gab Marcotti

Messi Moments with Álex Delmás: Real Betis 1 - 4 Barcelona, March 2019

We conclude our series on the evolution of Lionel Messi with a look at the Messi of recent seasons. We once again have Álex Delmás, ex-footballer, analyst for Barça TV and author of the book Messi Táctico, alongside us to assist in analysing the trajectory of one of the best players in the history of our sport.

Thanks to our Messi Data Biography we have data for all league matches involving Messi since his debut in 2004. For this series, Álex has picked out three significant matches in Messi’s evolution as a footballer.

We’ve already analysed the first iteration of Messi in the context of the March 2007 Clásico; and the second in the context of another Clásico, the famous 6-2 Barcelona win in May 2009. In this final part of the series, we’re going to look at a 4-1 win away to Real Betis (coached by the current Barcelona head coach Quique Setién) in March 2019.

Nick Dorrington (ND) (editor of StatsBomb’s Spanish-language site): Hi Álex. Can you tell me why you picked this match?

Álex Delmás (AD): I chose this match because here we see a more rounded, mature and complete version of Messi. It was between 2009 and 2012, in the era of Pep Guardiola, that I think the synergy between the level of Messi and the collective reached its highest point. From then onwards, Messi has continued to develop as a footballer at the same time that the collective level of the team has dropped off. And this is the perfect match to help us understand Messi’s new and current status within the team.

ND: In part two of this series, we talked about the Messi of the Guardiola years, and in this part we’re going to talk about his role in Ernesto Valverde’s Barcelona. But before we do that, can you give us a quick overview of Messi’s role in the period between Guardiola’s departure and Valverde’s arrival?

AD: Before Guardiola, he was primarily a player who operated down the right flank, as we saw in the first part of this series. With Guardiola, in the 6-2 match we watched last week, his position changed to that of a false nine, and with spectacular effect.

When Luis Enrique came in, and with the signings of Neymar and Luis Suárez, a few nuances were lost that meant the team didn’t interpret play as well with Messi as a false nine. There was less balance between playing between the lines and seeking to get in behind. In large part because the team lost players who were important in maintaining that balance, such as Samuel Eto’o, Thierry Henry and Pedro. So Luis Enrique placed Messi back on the right flank to form an unstoppable front three with Neymar and Suárez that yielded the second treble in Barcelona’s history.

ND: As we noted last week, in our database only the 2008-09 team had a better expected goal (xG) difference than that 2014-15 side.

AD: But Messi wasn’t the same player as when he had previously played on the right. Now, it was just a starting point from which to move infield and combine in central areas. As the years have passed that tendency has amplified, and it reached its peak under Valverde.

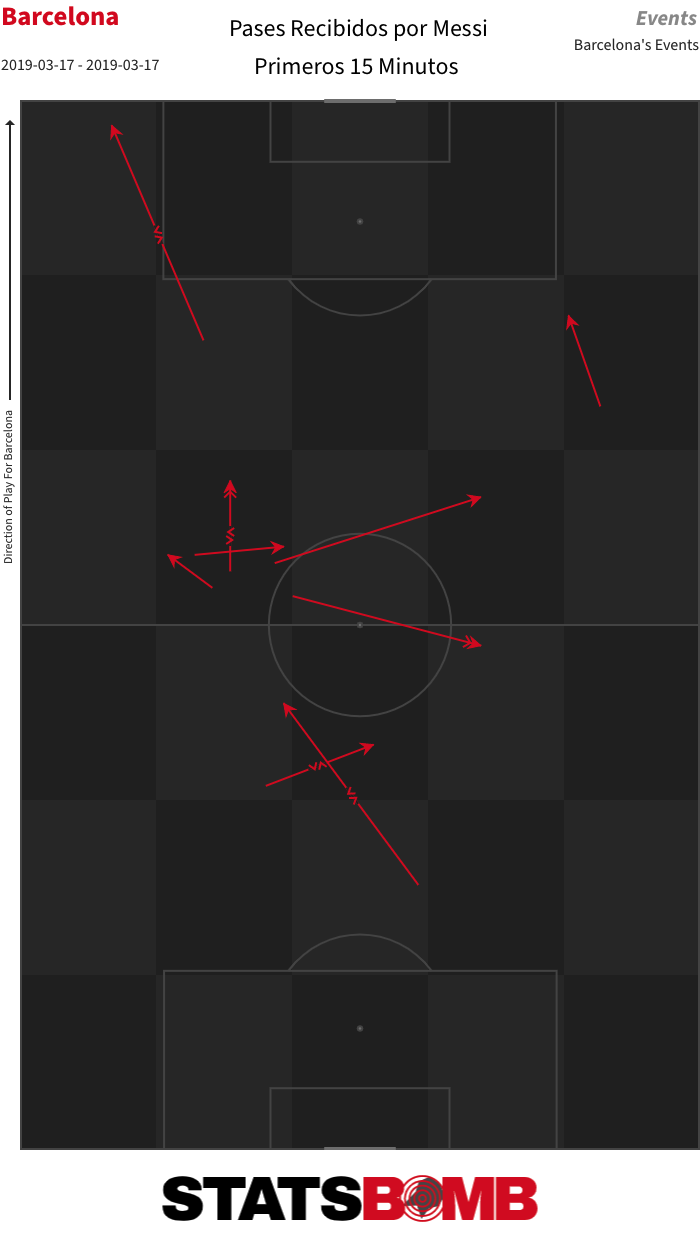

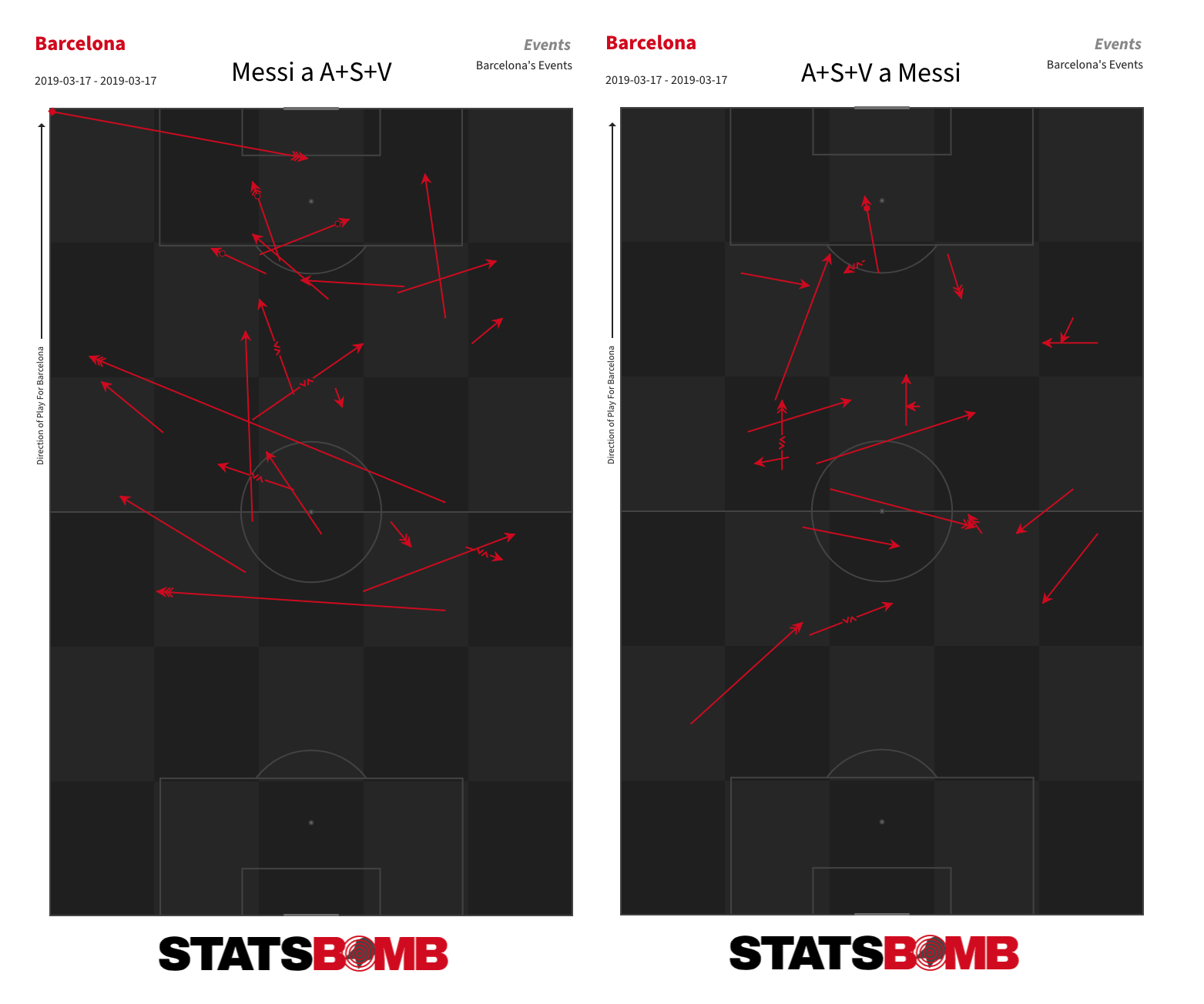

ND: We can see that in these maps of Messi’s attacking touches over the course of the last three seasons. He is now doing the majority of his offensive work in central areas and is much more involved in the construction of play in the midfield zone.

AD: Messi is increasingly more of a midfielder than a forward. He comes back to receive the ball in the centre of the pitch. In this match, Betis pressed intensely in the opening exchanges, and Barcelona needed Messi to drop back and help them advance the ball forward.

When Messi picks up the ball in deeper areas, he has a particular manoeuvre that he has developed over the years and which he also uses to give himself time to get into goalscoring positions, and that is pivoting movements with teammates further up the pitch. Suárez through the centre and Jordi Alba on the left are those with whom he has the best understanding in these movements. Also with Arturo Vidal, who makes runs ahead of him and returns one-twos.

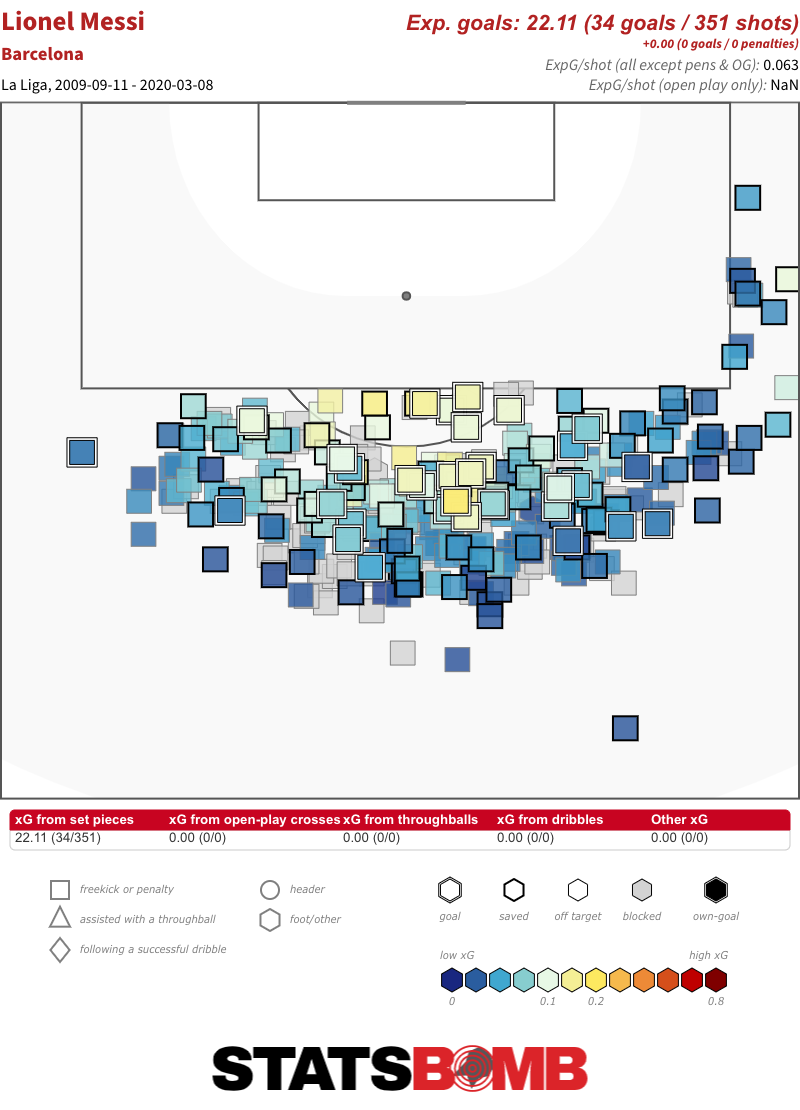

ND: Messi scores a hat-trick in this match. After a good start from Betis, it is him who opens the scoring in the 15th minute with an exquisite freekick. As you mentioned in the first part of this series, that is an aspect of his game he has improved as the years have passed.

AD: Yes. His freekicks are one of the most evident examples of Messi’s spectacular and progressive development. In the youth teams and when he moved up to the first team, he didn’t even think about stepping up to take them.

ND: Now, Messi is one of the few players for whom we have enough data to say with some confidence that he is a set-piece specialist.

To what do you attribute this development?

AD: It is said that it was Tito Vilanova, someone who had a lot of influence on Messi, who encouraged him to take and practice freekicks. Messi got to work and soon started scoring goals of all kinds and types. He has become the best freekick taker in the world. His shots are both powerful and well-placed. In time, he has been able to unite those two aspects.

He is now so good at them that opposing teams have started to put additional obstacles in his way, like players on the posts or under the wall, but he still overcomes them.

ND: In fact, in Barcelona’s last match, Real Sociedad did this:

Curious La Real setup to defend Messi free kick pic.twitter.com/whBKUilMBd

— Samuel Marsden (@samuelmarsden) March 7, 2020

Anyway, in this game against Betis, Messi scores the second goal in first-half stoppage time, and then, with the points already won, completes his hat-trick with a delicious first-time lob from the edge of the area.

AD: For me, the best goal of 2019.

ND: But he didn’t just provide the goals. He also set up more chances than any of his teammates.

AD: Messi has become so transcendental that he carries pretty all of the team's attacking weight. Excessively so, given that all of the danger comes from him.

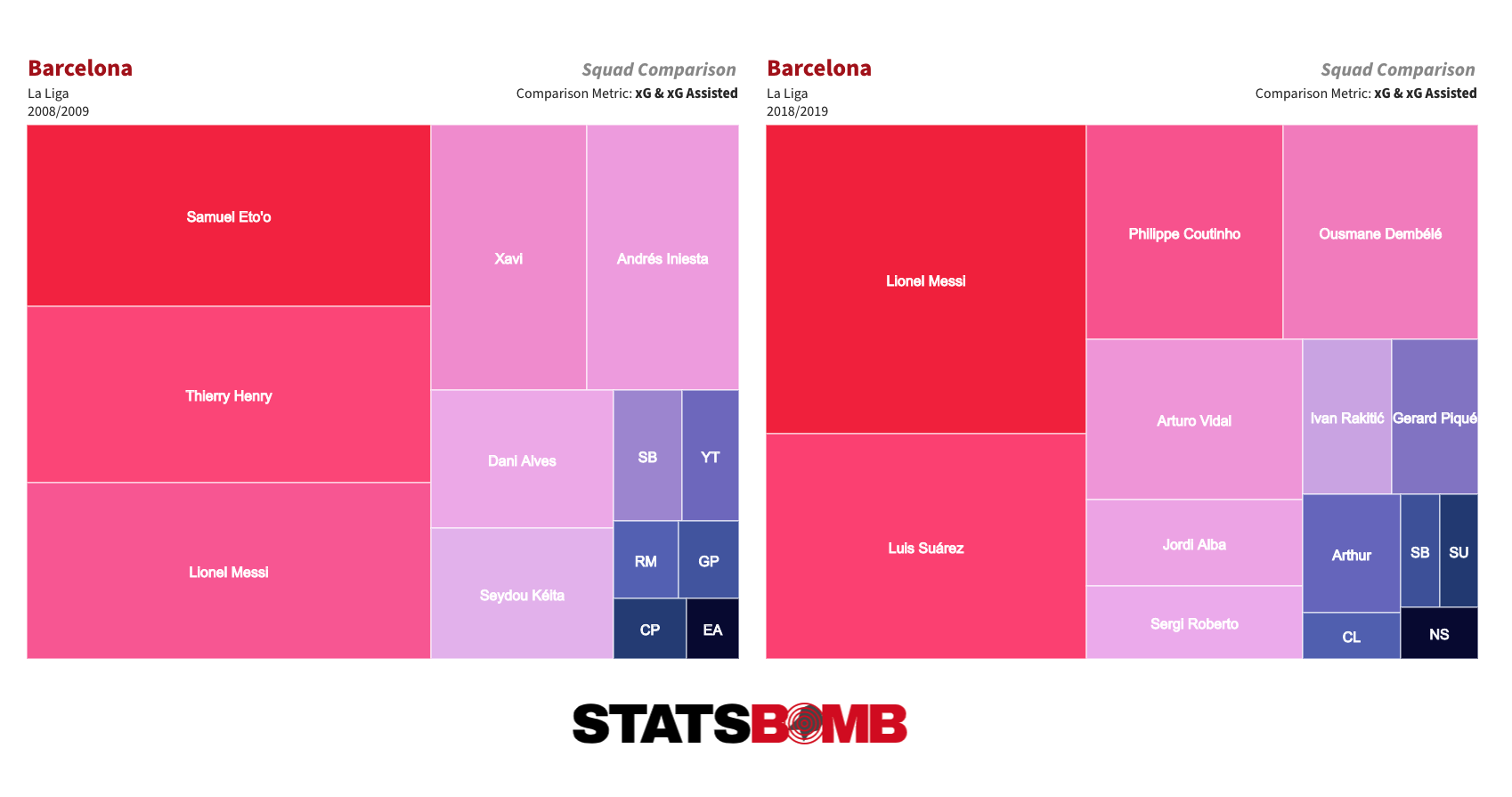

ND: We can see that in this graphic that shows the distribution of xG and xG assisted (xGA) between Barcelona’s squad members, first in 2008-09 and then in 2018-19, the season of this match. The distribution is a lot more even in 2008-09.

There are a number of other ways to try and measure the importance of an individual player to their team’s attack. It isn’t a perfect metric by any means, but one that does have a degree of utility is their usage rate. In basic terms, a player’s usage rate measures the percentage of their team’s attacks that end, for good or bad, at their feet.

In each of the last three seasons, including this one, Messi has led La Liga in this metric. In 2017-18, 18.8% of Barcelona’s attack ended at his feet. The figure was 21.2% last season, and has remained pretty much constant this season.

But it isn’t just in the crystallisation of attacks that Messi dominates this team. He also has a fundamental role in ball progression.

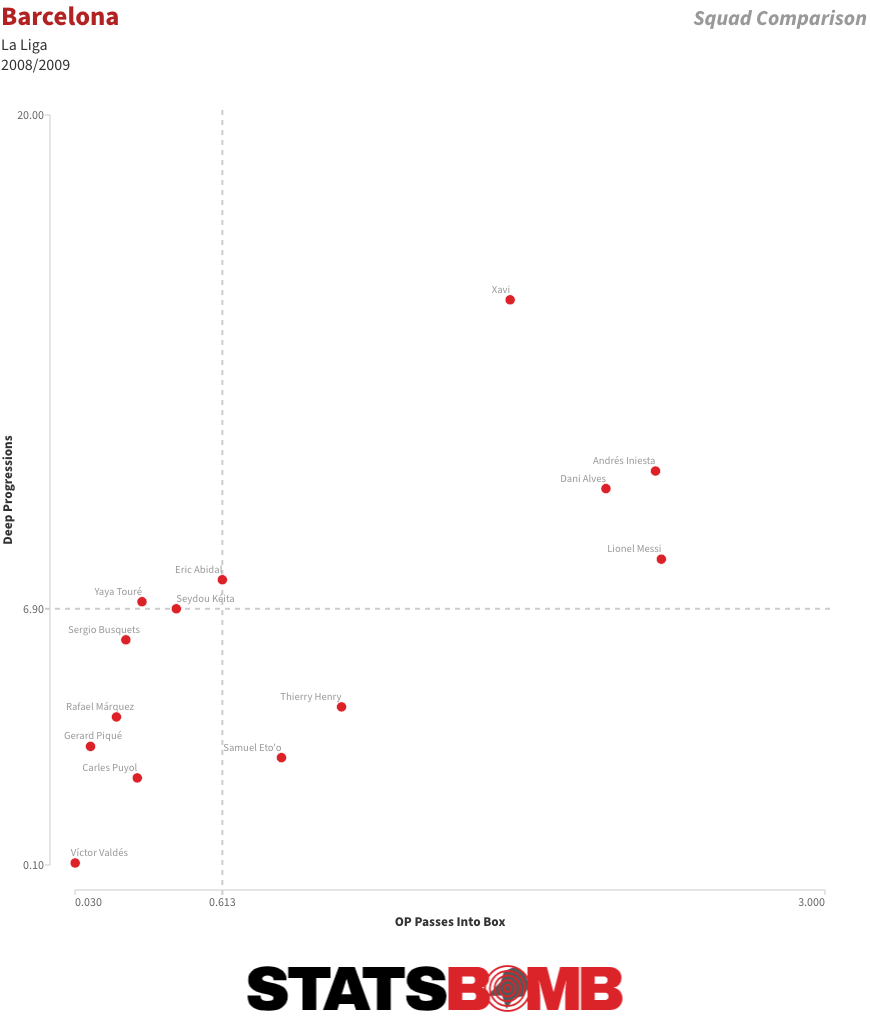

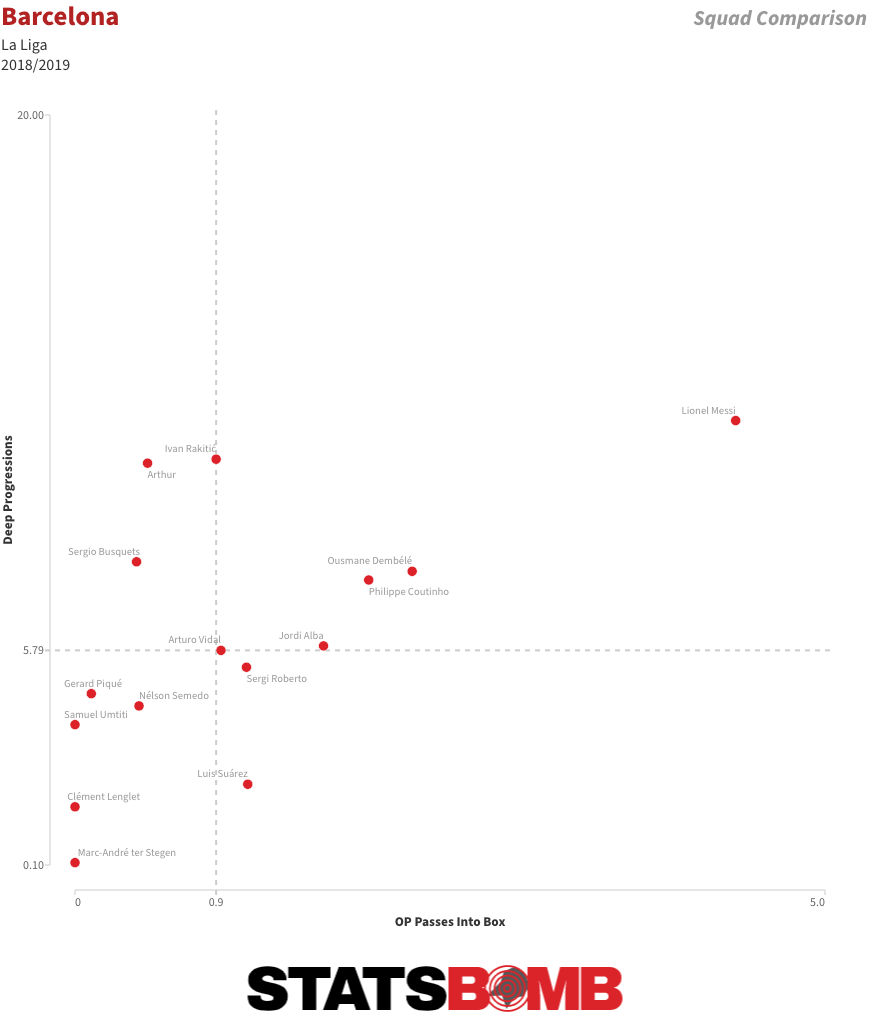

Here are two scatter graphs that plot open-play passes into the penalty area against deep progressions (carries, dribbles or passes into the final third). First, for the 2008-09 season.

In this one, we can see that Messi leads the team in passes into the penalty area but it is Xavi who carries the weight of ball progression into the final third, with Andrés Iniesta and Dani Alves also more involved in that task than Messi. Now, for the 2018-19 season.

These days Messi does everything, and this match is the perfect example. He was the Barcelona player who played the most successful passes, who most often moved the ball into the final third, who played the most passes into the area and who carried the ball more often and over greater distances than any of his teammates. Has there been too much dependence on Messi in recent seasons?

AD: Yes. It has often been the case that there has been too much dependence on Messi. To explain it another way, there have been moments when they haven’t been able to benefit from the extraordinary power of Messi because they’ve relaxed and let him do everything. And that has led to the team no longer applying certain automatisms.

ND: Could you explain what you mean by automatisms?

AD: An automatism is a series of coordinated movements that a team uses to gain an offensive or defensive advantage. An example would be having two wide forwards who are permanently positioned out wide, like we saw in Guardiola’s Barça. That is an automatism that helps create space infield. Or to have one of the full-backs stay back and position himself infield while the other moves forward into attack. Barça no longer apply some of these, like positioning the three central midfielders close together in a triangle shape, like the constant width from the wide forwards, like the off-ball runs of the two advanced central midfielders into the area... small details without apparent importance but that are decisive at the highest level.

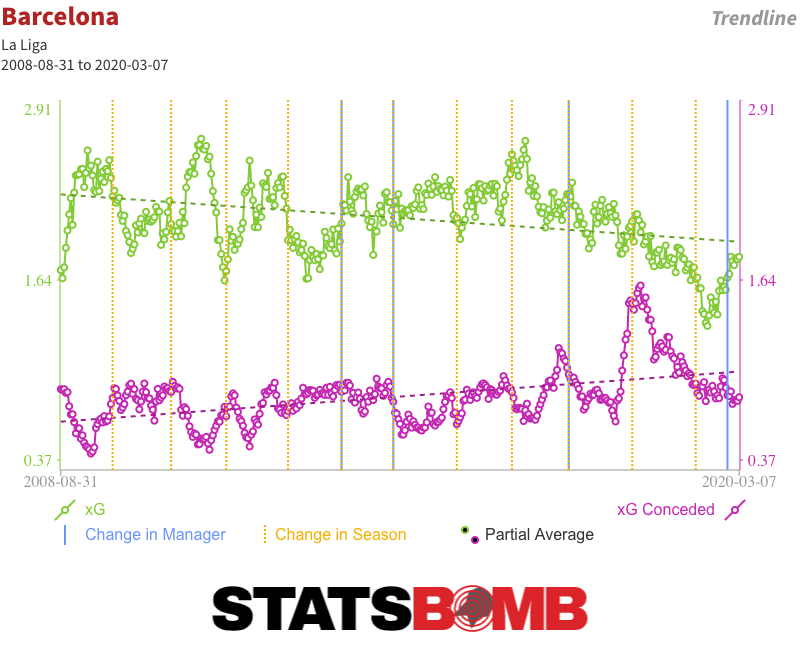

ND: This trendline of Barcelona’s xG and xG conceded (xGC) from Guardiola’s time to the present day (utilising a 15-match rolling average) shows the relative drop off in attacking output in recent years.

The club continue to enjoy success in La Liga, but they’ve discarded certain elements of their previous style and their reliance on Messi to solve everything has perhaps hurt them at a European level.

What do you think has caused this slight change in approach (I say slight because in the context of La Liga, Barça continue to have a profile that is distinct from that of the majority of teams) over the last few years? The coaches? Or is it a natural development given the departure of players like Xavi and Iniesta, two of Messi’s key accomplices?

AD: It’s true. The change is palpable even though it isn’t extraordinary given that Barça continue to be a team who have a high share of possession and who consistently seek to generate attacking football regardless of the situation or opponent. But as I said before, all factors have an influence at the highest level.

I think the change is down to various factors and they are all equally important.

One of those is the coach. Guardiola, Luis Enrique and Valverde are all great coaches but from my vantage point, Guardiola has a special gift for tactics, and especially for hitting upon offensive solutions within the framework of positional play. He is the best possible coach to apply positional play because he practiced it for almost the entirety of his playing career at Barça and also worked under Johan Cruyff.

As is logical and normal, each coach introduces their own nuances to a particular style of play. Luis Enrique exchanged some of the patience in build up play for quicker attacks. It is also worth noting, however, that with such a potent front three, he had to base his team around them. The team stopped doing certain things, like the insistence on circulating the ball, although many other positive elements were preserved.