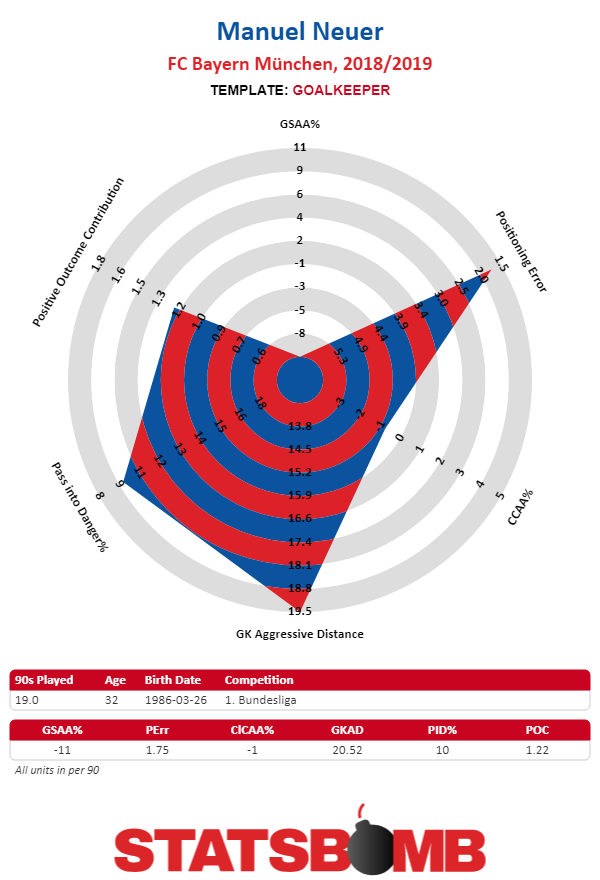

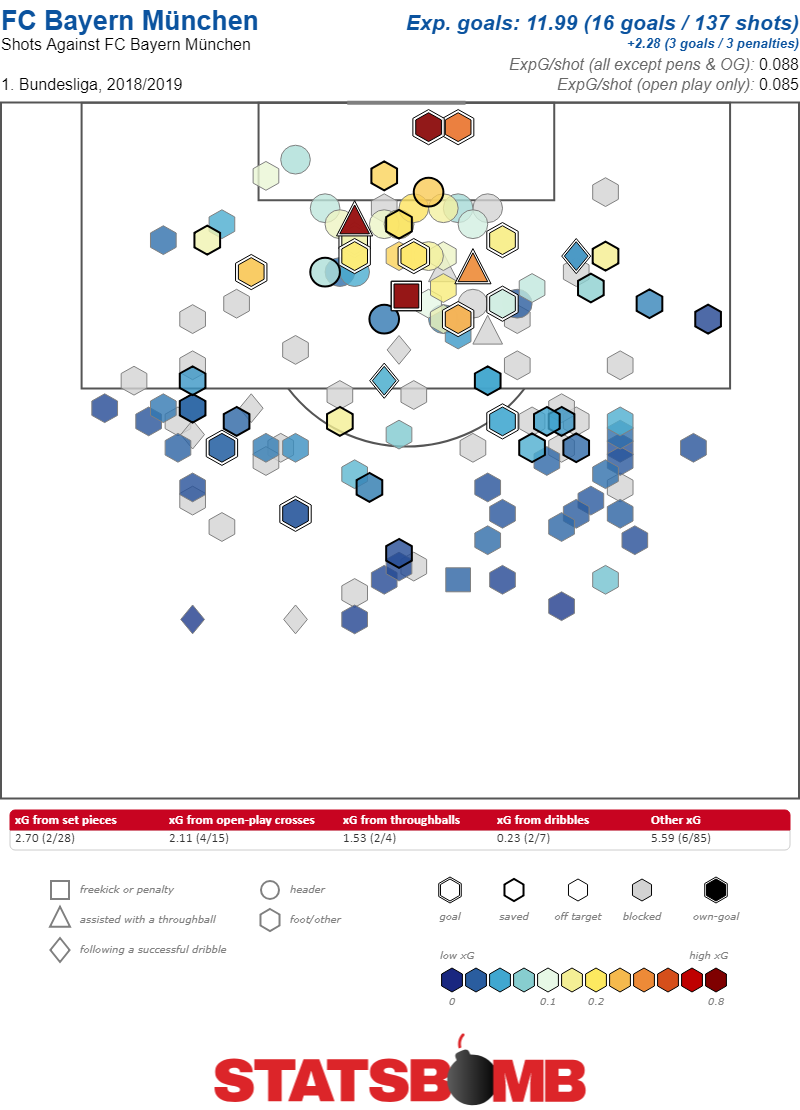

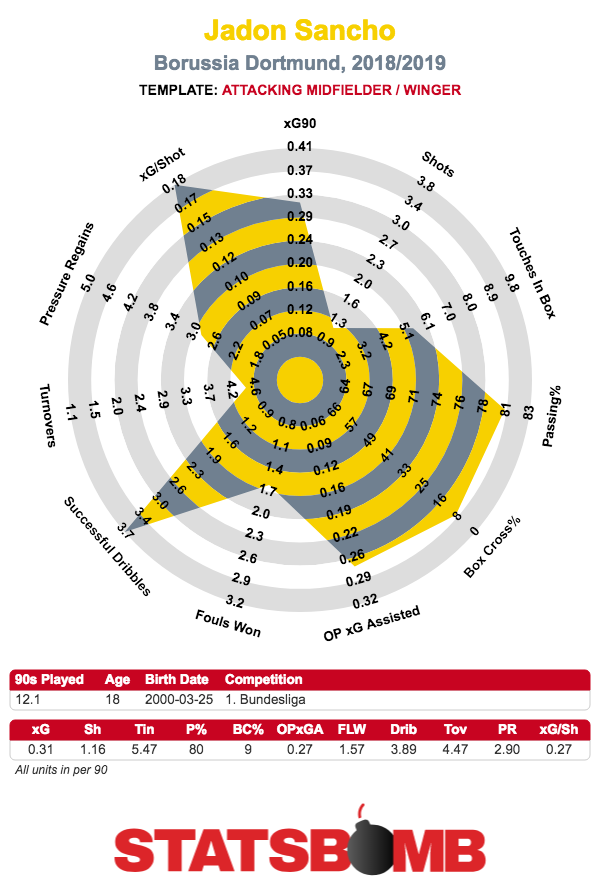

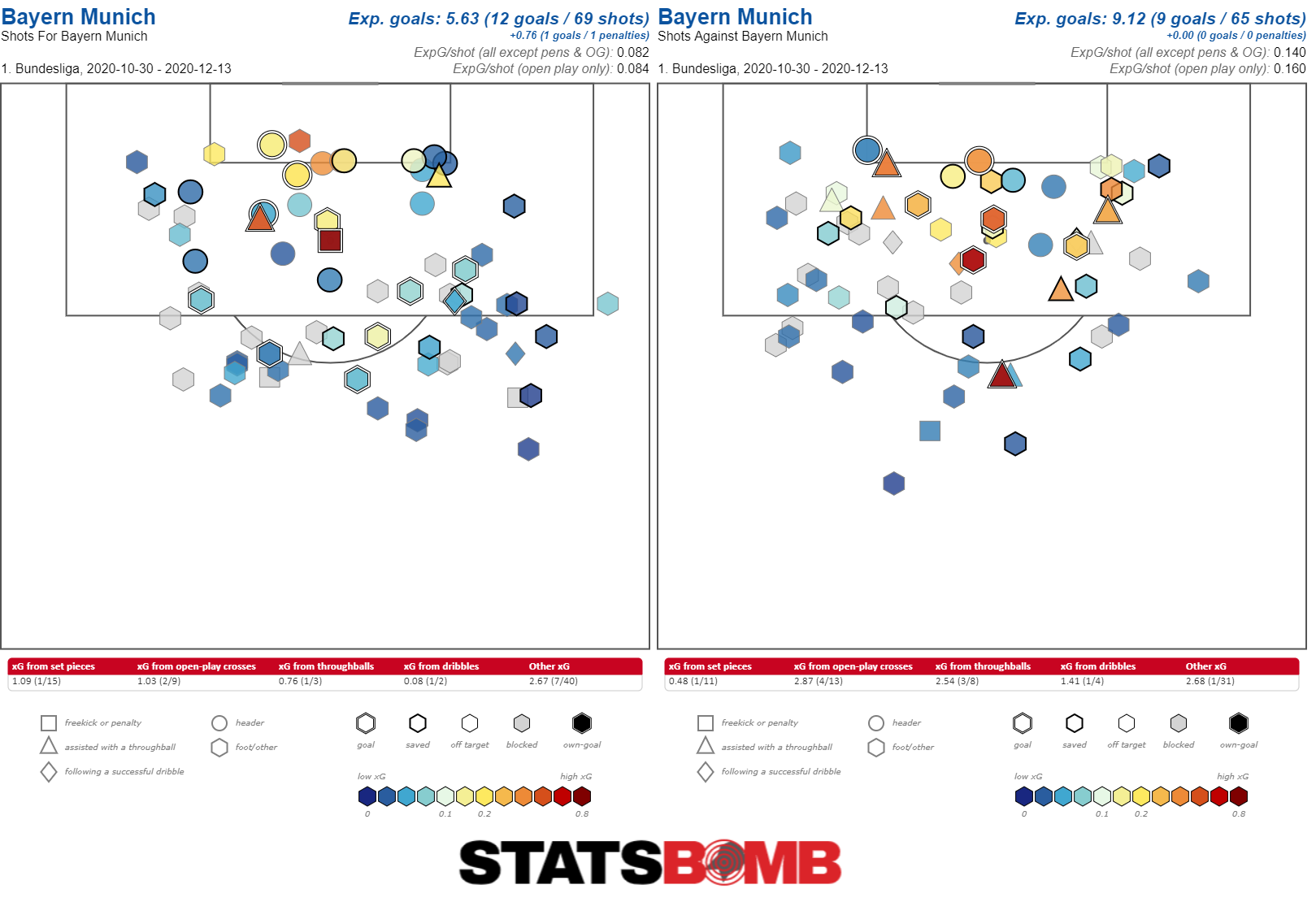

This is awkward, but we really need to talk about Manuel Neuer. He’s a legend of a keeper. For a decade he’s been a unique and special player. His ability with the ball at his feet gained him a cult following, but it was the fact that he paired that with some of the best fundamental goalkeeping ability in the world that made him truly special. He was great at the basics. And then sometimes he’d also dribble the ball around just for fun. But the basics seem to have abandoned him. Bayern’s dominance means Neuer isn’t often called into action. The team only gives up 7.61 shots per match. That’s the best number in the Bundesliga. They are incredibly good at stifling opponents’ attacks. And, even when they do ultimately give up shots, those shots tend not to be dangerous ones. Opponents, on average, take shots from 18.49 yards away from Bayern’s goal. That’s the furthest out of any side in the Bundesliga, and they’re worth 0.09 expected goals per shot, again the lowest average volume. The shots Bayern are giving up don’t seem to be bad shots. And, yet, they keep flying into the net.  It is of course possible, that Neuer has simply run into a string off awful luck. That despite having a mediocre collection of shots, strikers just keep hitting the ball outstandingly and picking out corners in ways that Neuer couldn’t hope to stop. Except that post-shot xG suggests this isn’t the case. The post-shot value of the shots Neuer has faced is almost exactly the same. The model spits out 11.0 expected goals conceded from open play. Neuer has conceded 16.

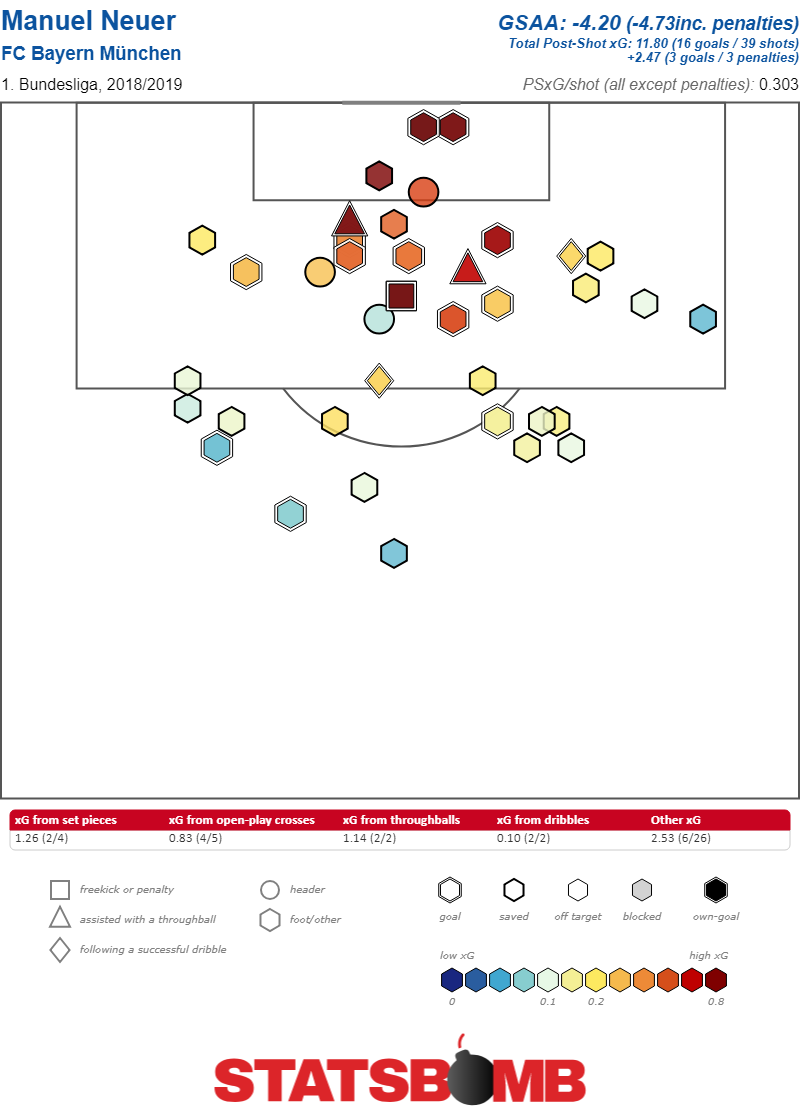

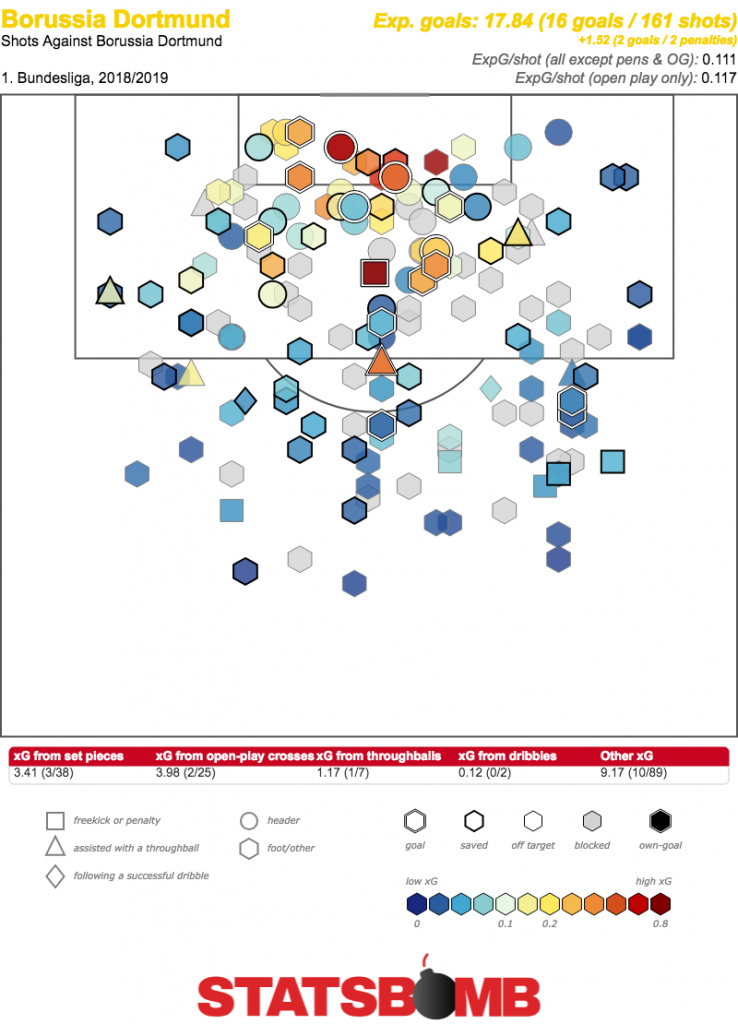

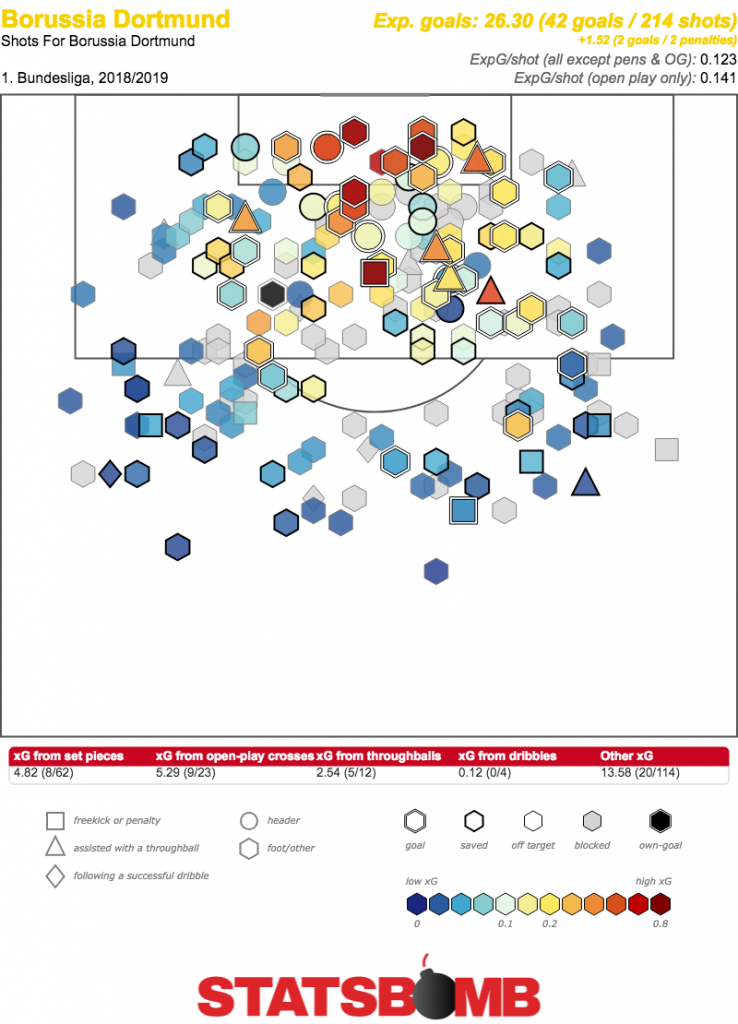

It is of course possible, that Neuer has simply run into a string off awful luck. That despite having a mediocre collection of shots, strikers just keep hitting the ball outstandingly and picking out corners in ways that Neuer couldn’t hope to stop. Except that post-shot xG suggests this isn’t the case. The post-shot value of the shots Neuer has faced is almost exactly the same. The model spits out 11.0 expected goals conceded from open play. Neuer has conceded 16.  There is one interesting statistical wrinkle here. As the two charts show, relatively few of the shots that Bayern have given up have found their way on target, and of those that have, they’ve been mostly the most dangerous shots. The result is that despite the fairly innocuous profile of shots that Bayern have given up on the whole, the ones that Neuer has ended up facing have been quite dangerous. His job has been harder than it might seem at first glance. His expected save rate is only 69.7%. That’s the seventh lowest in the league. The problem is, that even when you adjust for all of that Neuer is still failing miserably. His save percentage is only 59%. Among first choice keepers that’s the second lowest total in the league. Worse, the difference between his save percentage, and his expected save percentage, that 10.7% gap, it’s also the second worst in Germany. There’s no way to sugar coat it. Neuer has just been bad. The fact that Bayern themselves are quite good has gone a long way to masking his performance. They’ve only conceded 19 total goals. Only two teams have conceded fewer, and they’re on 18. Bayern’s defensive record is close to the best in the league, so how bad could Neuer really be anchoring it? Well, when you graph goals conceded against the goals save above average percentage it becomes clear just how large an outlier Neuer is.

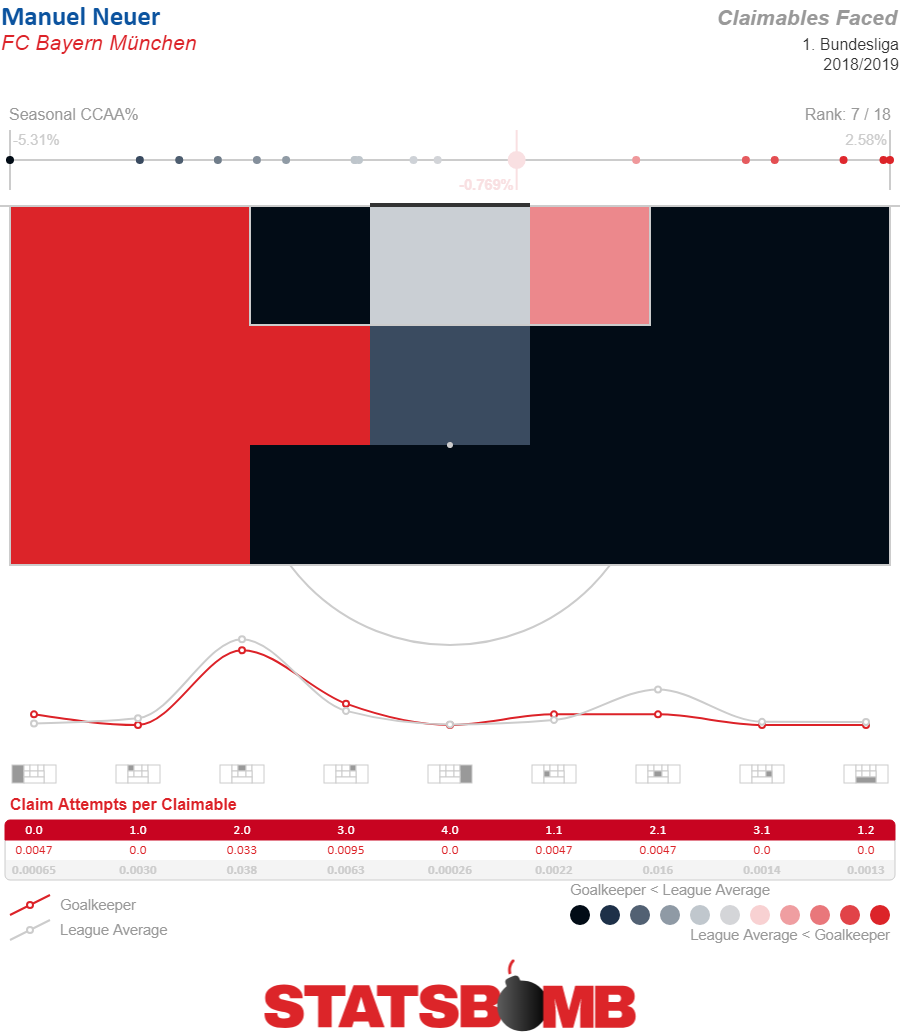

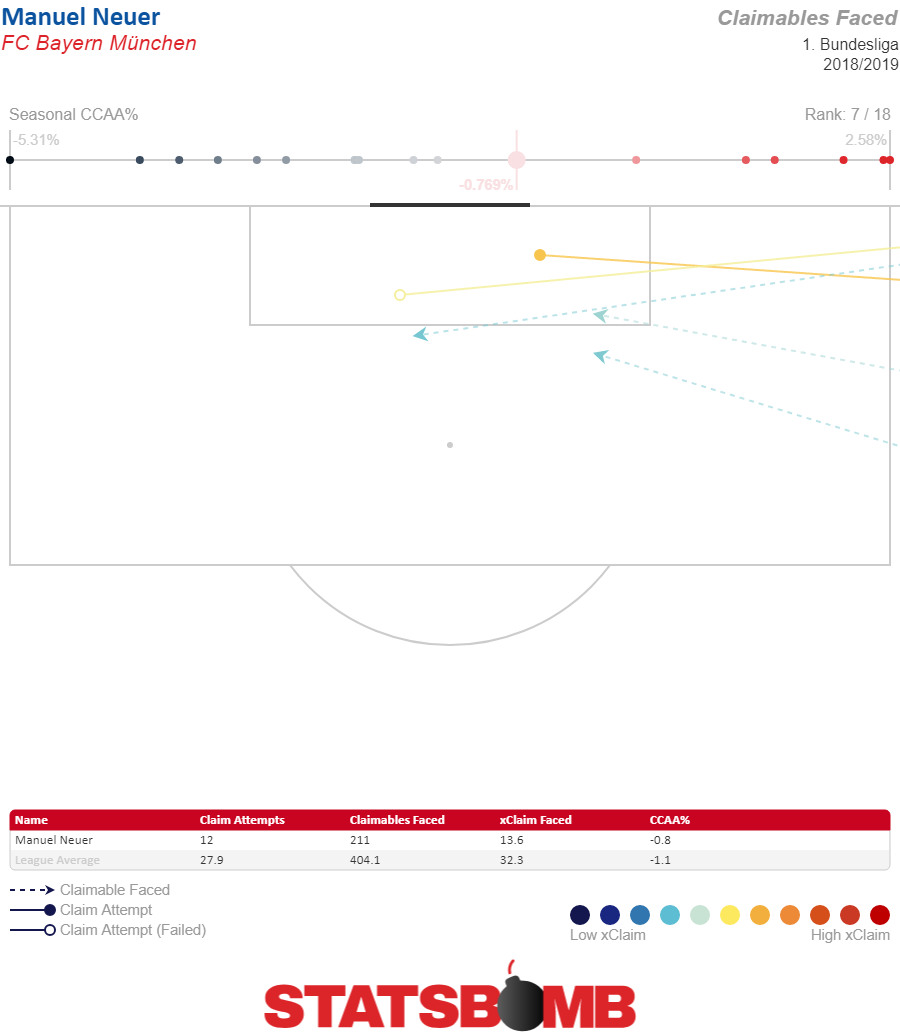

There is one interesting statistical wrinkle here. As the two charts show, relatively few of the shots that Bayern have given up have found their way on target, and of those that have, they’ve been mostly the most dangerous shots. The result is that despite the fairly innocuous profile of shots that Bayern have given up on the whole, the ones that Neuer has ended up facing have been quite dangerous. His job has been harder than it might seem at first glance. His expected save rate is only 69.7%. That’s the seventh lowest in the league. The problem is, that even when you adjust for all of that Neuer is still failing miserably. His save percentage is only 59%. Among first choice keepers that’s the second lowest total in the league. Worse, the difference between his save percentage, and his expected save percentage, that 10.7% gap, it’s also the second worst in Germany. There’s no way to sugar coat it. Neuer has just been bad. The fact that Bayern themselves are quite good has gone a long way to masking his performance. They’ve only conceded 19 total goals. Only two teams have conceded fewer, and they’re on 18. Bayern’s defensive record is close to the best in the league, so how bad could Neuer really be anchoring it? Well, when you graph goals conceded against the goals save above average percentage it becomes clear just how large an outlier Neuer is.  What this makes crystal clear is that the defense is carrying Neuer right now. He’s conceded a stingy number of goals despite the way he’s played. The defense deserves the credit for not allowing more dangerous shots for Neuer to struggle saving. It’s not like Neuer is dominating in the air when it comes to commanding his box either. Here’s the heatmap showing how likely he is to come for claimable balls in his box. He faced 212 total balls, and came for 12 of them, a little more conservative than the 13.6 our model predicts. That makes him, by our model, only the seventh most aggressive keeper in and around his penalty area in the Bundesliga.

What this makes crystal clear is that the defense is carrying Neuer right now. He’s conceded a stingy number of goals despite the way he’s played. The defense deserves the credit for not allowing more dangerous shots for Neuer to struggle saving. It’s not like Neuer is dominating in the air when it comes to commanding his box either. Here’s the heatmap showing how likely he is to come for claimable balls in his box. He faced 212 total balls, and came for 12 of them, a little more conservative than the 13.6 our model predicts. That makes him, by our model, only the seventh most aggressive keeper in and around his penalty area in the Bundesliga.  It’s also true that he’s faced very few balls that a keeper would frequently claim. Only five balls into the box all season where the type that a keeper would come for more than 30% of the time. He came for two of them (an exactly average frequency given the balls faced), but he missed one. The fact that his overall success rate on claims is 92% and fine, exists in concert with the fact that he’s only one for two on the more meaningful ones.

It’s also true that he’s faced very few balls that a keeper would frequently claim. Only five balls into the box all season where the type that a keeper would come for more than 30% of the time. He came for two of them (an exactly average frequency given the balls faced), but he missed one. The fact that his overall success rate on claims is 92% and fine, exists in concert with the fact that he’s only one for two on the more meaningful ones.  In a different context maybe these stats wouldn’t be so alarming. Players have bad stretches, even great ones. Keepers have bad years, or half years, and bounce back all the time. But, taking a step back actually makes the situation look worse, not better. Neuer isn’t young, he’ll be 33 in March. Keepers often have longer athletic lives than outfield players, but 33 is still pushing it. It’s an age where, in a vacuum you’d expect a keeper to get worse not better. Then there are the injuries. Neuer missed the vast majority of last season with foot problems. His performance still hasn’t recovered. Correlation doesn’t equal causation, but it doesn’t rule it out either. Put it all together and this is a four-alarm fire for Bayern. Neuer used to be a star, now he’s facing a life comes at you fast crisis. All of a sudden he’s become an old keeper coming off an injury who hasn’t come close to recovering his form half a season after getting back on the pitch. If Bayern don’t rally over the last half of the season and catch Borussia Dortmund, Neuer’s deterioration will be a large part of what went wrong. A year ago it would have been sacrilegious to question Neuer’s place. Now? Unless he improves dramatically over the second half of this season it’s clear Bayern will need to upgrade the keeper position going into next year. The keeper might be a legend, but eventually father time comes for legends too.

In a different context maybe these stats wouldn’t be so alarming. Players have bad stretches, even great ones. Keepers have bad years, or half years, and bounce back all the time. But, taking a step back actually makes the situation look worse, not better. Neuer isn’t young, he’ll be 33 in March. Keepers often have longer athletic lives than outfield players, but 33 is still pushing it. It’s an age where, in a vacuum you’d expect a keeper to get worse not better. Then there are the injuries. Neuer missed the vast majority of last season with foot problems. His performance still hasn’t recovered. Correlation doesn’t equal causation, but it doesn’t rule it out either. Put it all together and this is a four-alarm fire for Bayern. Neuer used to be a star, now he’s facing a life comes at you fast crisis. All of a sudden he’s become an old keeper coming off an injury who hasn’t come close to recovering his form half a season after getting back on the pitch. If Bayern don’t rally over the last half of the season and catch Borussia Dortmund, Neuer’s deterioration will be a large part of what went wrong. A year ago it would have been sacrilegious to question Neuer’s place. Now? Unless he improves dramatically over the second half of this season it’s clear Bayern will need to upgrade the keeper position going into next year. The keeper might be a legend, but eventually father time comes for legends too.

Month: January 2019

Real Madrid's Isco Conundrum

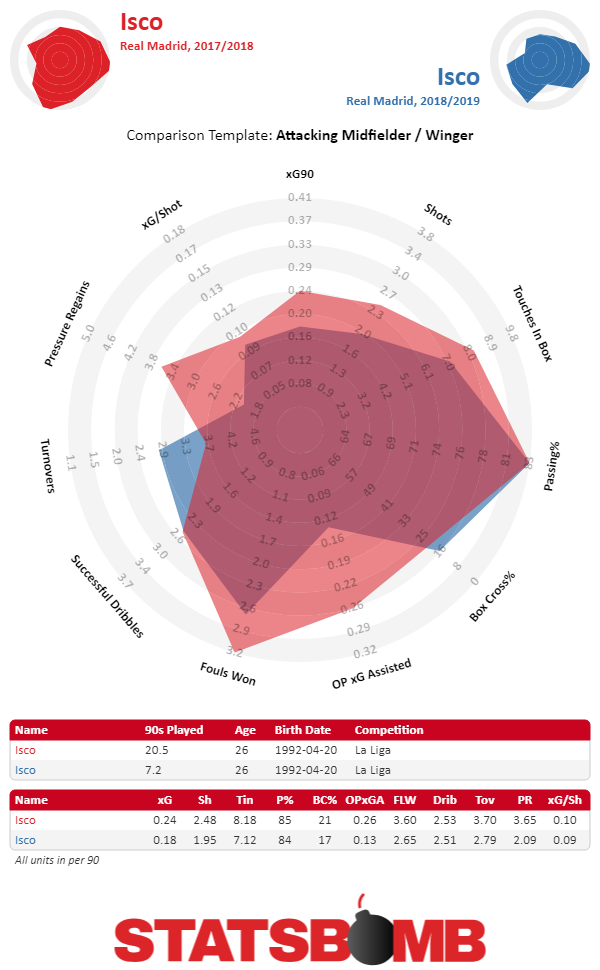

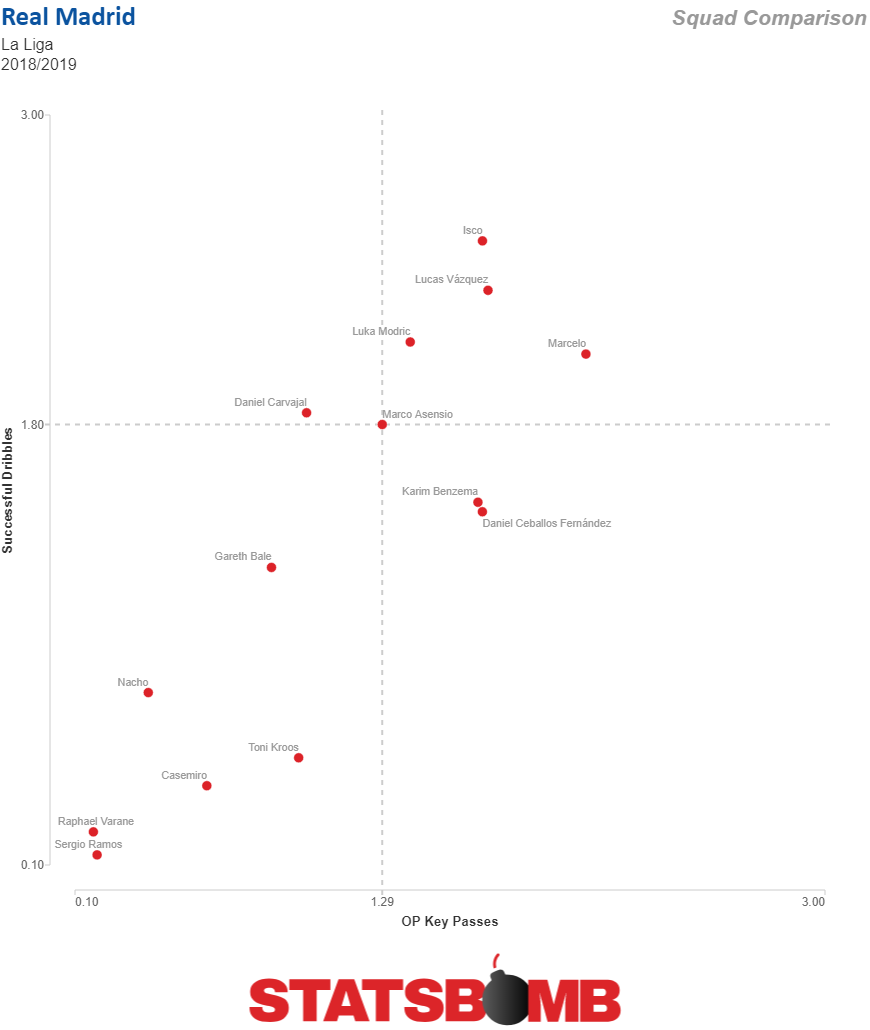

There is always something brewing behind the scenes at Real Madrid -- a team generally too deep in too many positions to satisfy every star’s playing time. Every season there are head-scratchers on the bench -- James Rodriguez, Gareth Bale -- but those absentees weren’t noticed as much with Zinedine Zidane winning as prolifically as he did. Winning masks everything. This season, with the team struggling, and Isco coming off the bench, the noise surrounding the Isco - Solari union keeps mounting. Isco plays a theoretical position in Real Madrid -- just like James did, just as Coutinho does at Barcelona, and just as Mesut Ozil does at Arsenal. These players are labelled, at mass, as a ‘10’ -- stereotypical turtles who grind the offense to a painstaking hault. They’re great at controlling tempo, but sometimes the offense needs an extra jolt. Under Lopetegui, Real Madrid had plenty of the ball, but not many clear-cut chances or goals. Solari wants to have his offense slightly more rigid positionally, which leaves less room for roaming creators. Media outlets throwing around skewed stats don’t help the narrative. Real Madrid haven’t won a good percentage of games with Isco in the team -- but that’s mostly because Isco has been coming in late off the bench when Solari’s men are chasing games against stubborn defensive schemes. Isco is not without his faults. This season, he’s struggled to show his form from the 2016/2017 campaign (or some of his great showings in the Champions League in ‘17/18). Since returning from injury, he hasn’t looked match-fit (almost reasonably, to be sure, given that appendicitis is not an easy procedure to return from). In his return against Levante earlier this season, he was dispossessed multiple times, and gave the ball away in deep areas. Against Viktoria Plzen at home, he was whistled for a selfish attempt -- when a simple square pass to Benzema would’ve resulted in a goal. When he came on at half-time for an injured Bale against Villarreal, Real Madrid’s entire tempo decelerated, as Isco dropped deeper to combine with the midfielders rather than pushing high up the pitch as an outlet in transition as the Welshman did. But the sample size with Isco in the team is hard to ignore, and his form under Zidane shouldn’t be that unrecoverable for a player who’s 26 and in the prime of his career. We’re witnessing a Real Madrid team that can’t deal with an opposing high press, nor can they find the ingenuity needed on a consistent basis to break down stubborn low-blocks. Isco fits both needs -- he is press-resistant, and like Marcelo, can find space in impossible situations.  It’s hard to decipher just what the reason is for Isco finding himself coming off the bench. There are signs from within the team that Solari’s decision is less personal, and more logical: The Spanish midfielder is still not 100% match fit, and you already know what you’re going to get from the players ahead of him. Vinicius is a gung-ho, line-breaking menace (raw, full of mistakes, and yet the biggest offensive threat Real Madrid have had of late), and Lucas Vazquez is a two-way winger with a ceaseless motor. Solari has not favoured Isco in deeper positions either, as after the Modric / Kroos tandem, the Argentine coach has opted to roll with a box-to-box, decisive player in Fede Valverde; or a frenetic, energy-filled Dani Ceballos. And energy, as intangible as it sounds, is something Real Madrid have missed badly. Dani Ceballos fuelled the team with his off-ball movement and defensive coverage against Sevilla, in what was one of the team’s best performances of the season: https://streamable.com/o97ms That was a sequence where Ceballos sprinted back to cover for Ramos, who was caught out of position after a giveaway. Ceballos then helps Reguilon dispossess Jesus Navas. On an ensuing play, he’s on the opposite flank, covering the passing lane behind Dani Carvajal: https://streamable.com/cwfc0 Neither of these plays are foreign to Isco, which makes the entire situation so bewildering. Isco is a highly intelligent defensive player, and his work rate has been exemplary in the past. Against PSG in last season’s Champions League round-of-16 first leg, Isco ran himself into the ground, pressed like a maniac, won the ball high up the pitch, and was efficient covering defensively for surging wingbacks. He can play either the left central midfield or left wing positions just fine -- and isn’t only reliant on being shoehorned as the spearhead of a diamond formation. Isco isn’t playing well now, looks a step slow, and is missing some mojo -- but the attributes that Ceballos, Valverde, Vinicius, or Vazquez have are not beyond him. Even amid one of the most forgettable seasons in Isco’s career, he remains a steady contributor. Only the great Marcelo and the ever present Lucas Vazquez sling more open play key passes per 90 (1.68) in La Liga on the team than Isco; and the Spaniard completes 2.51 dribbles per 90 -- only Vinicius Jr, in very limited minutes, has more on the team, at 2.89

It’s hard to decipher just what the reason is for Isco finding himself coming off the bench. There are signs from within the team that Solari’s decision is less personal, and more logical: The Spanish midfielder is still not 100% match fit, and you already know what you’re going to get from the players ahead of him. Vinicius is a gung-ho, line-breaking menace (raw, full of mistakes, and yet the biggest offensive threat Real Madrid have had of late), and Lucas Vazquez is a two-way winger with a ceaseless motor. Solari has not favoured Isco in deeper positions either, as after the Modric / Kroos tandem, the Argentine coach has opted to roll with a box-to-box, decisive player in Fede Valverde; or a frenetic, energy-filled Dani Ceballos. And energy, as intangible as it sounds, is something Real Madrid have missed badly. Dani Ceballos fuelled the team with his off-ball movement and defensive coverage against Sevilla, in what was one of the team’s best performances of the season: https://streamable.com/o97ms That was a sequence where Ceballos sprinted back to cover for Ramos, who was caught out of position after a giveaway. Ceballos then helps Reguilon dispossess Jesus Navas. On an ensuing play, he’s on the opposite flank, covering the passing lane behind Dani Carvajal: https://streamable.com/cwfc0 Neither of these plays are foreign to Isco, which makes the entire situation so bewildering. Isco is a highly intelligent defensive player, and his work rate has been exemplary in the past. Against PSG in last season’s Champions League round-of-16 first leg, Isco ran himself into the ground, pressed like a maniac, won the ball high up the pitch, and was efficient covering defensively for surging wingbacks. He can play either the left central midfield or left wing positions just fine -- and isn’t only reliant on being shoehorned as the spearhead of a diamond formation. Isco isn’t playing well now, looks a step slow, and is missing some mojo -- but the attributes that Ceballos, Valverde, Vinicius, or Vazquez have are not beyond him. Even amid one of the most forgettable seasons in Isco’s career, he remains a steady contributor. Only the great Marcelo and the ever present Lucas Vazquez sling more open play key passes per 90 (1.68) in La Liga on the team than Isco; and the Spaniard completes 2.51 dribbles per 90 -- only Vinicius Jr, in very limited minutes, has more on the team, at 2.89  But Solari doesn’t pick his team based on what he knows Isco is capable of. He’s in ‘win-now’ mode, in what is perhaps a fleeting, short-term job for him. He needs players who are in top shape and ready to contribute. The Argentine has not been shy about benching players who aren’t up to speed physically -- with Marcelo taking a backseat against Sevilla; while Sergio Reguilon put in a strong defensive shift in his place. There is a directness, speed, verticality, and positional rigidity that Solari wants to play with, and other players are like-for-like puzzle pieces that can fit his scheme seamlessly. There is an expectation from coaches in general to play their best players. Egos are expected to be put aside (as they should be), and tactical flexibility should go hand-in-hand with getting the best out of your best players in order for both team and player to thrive. There is one thing that Real Madrid would want to consider: How much do they want to disgruntle Isco to the point where he desires to leave, at the hands of a transitory coach who’s likely at the helm for just a few months? It’s easy to pick your poison. Isco is one of the best players in the world, and Solari is an unproven manager whose value is not hard to replace. But looking at it that way is not that easy, even if tempting. While Solari is at Real Madrid, he should be given the reigns to make the decisions he feels are best for the team. That’s a gamble Real Madrid has to take, anyway. Trusting a caretaker doesn’t come without its perils. Leaving Isco on the bench while implementing a hyper-rigid system didn’t work out at first. The team hit rock bottom in a 3 - 0 defeat away to Eibar, when they couldn’t escape a press (while one of their most press-resistant players, Isco, wasn’t on the field). They struggled again in narrow wins over Huesca and Eibar. Trusting Solari seems to now be paying off. Of late, the team has been picking up steam. Solari seems to have found the balance between rigidity and fluidity -- there is more off-ball movement between the lines, and the now in-form Luka Modric is picking out his teammates in dangerous spots. While Solari may have issues on a personal level with Isco, there are enough tactical reasons for his decisions. But the team has to sustain this form, which is not easy, in order to fully justify not having Isco in the regular scheme. This isn’t a repeat of the Pogba - Mourinho trial, where Mourinho repeatedly threw Pogba under the bus publicly, and the tension was clear. Solari has shown respect to Isco publicly, stating that he “loves” him. Nacho has come out and said that Solari is “on Isco’s side”. Marcelo publicly stated after the 0 - 2 win away to Roma: “I’m not saying that he (Isco) is not working but when you see you have made a mistake you must improve.” Isco is not a lost cause -- his form is within reach, and the squad is on his side. He has come off the bench in most games under Solari, even if the outcome hasn’t all been successful. The team has gone through enough injuries and suspensions this season (and in the past) to assume Isco will always have a chance to claim his spot -- just as he rose in the 2016 / 2017 season amid Bale’s big injury to form a cohesive, control-based midfield alongside Toni Kroos and Luka Modric. But he didn’t crack the starting XI in any big games during this stretch with Bale and Asensio injured. Now Bale and Asensio (neither of whom are in form either) are inching their way back into the team. Marcos Llorente has also resumed training. While he’s not a comparable player positionally to Isco, his emergence on the scene this season means Solari will play either him or Casemiro as the team’s single pivot -- taking away one more starting XI spot as Toni Kroos will no longer be pushed back as a defensive midfielder, which would free up a LCM slot for Isco. Real Madrid are famously thin at the striker position, but have loaded depth in midfield, where the great Isco resides. The ideal scenario for everyone involved is for Solari to unearth the Isco from two seasons ago and get Real Madrid ticking at a fluid tempo, retaining possession high up the pitch and attacking their opponents relentlessly. But whether he can do that, when hungry players like Ceballos, Valverde and Vinicius are exiting the realm of fringe rotation, is a different question. “Competition within the squad is an essential part of football,” Solari told the media ahead of Thursday’s Copa del Rey clash with Girona. “Everyone must feel they have an opportunity and can lose their place [if they don't do well]." Image courtesy of the Press Association

But Solari doesn’t pick his team based on what he knows Isco is capable of. He’s in ‘win-now’ mode, in what is perhaps a fleeting, short-term job for him. He needs players who are in top shape and ready to contribute. The Argentine has not been shy about benching players who aren’t up to speed physically -- with Marcelo taking a backseat against Sevilla; while Sergio Reguilon put in a strong defensive shift in his place. There is a directness, speed, verticality, and positional rigidity that Solari wants to play with, and other players are like-for-like puzzle pieces that can fit his scheme seamlessly. There is an expectation from coaches in general to play their best players. Egos are expected to be put aside (as they should be), and tactical flexibility should go hand-in-hand with getting the best out of your best players in order for both team and player to thrive. There is one thing that Real Madrid would want to consider: How much do they want to disgruntle Isco to the point where he desires to leave, at the hands of a transitory coach who’s likely at the helm for just a few months? It’s easy to pick your poison. Isco is one of the best players in the world, and Solari is an unproven manager whose value is not hard to replace. But looking at it that way is not that easy, even if tempting. While Solari is at Real Madrid, he should be given the reigns to make the decisions he feels are best for the team. That’s a gamble Real Madrid has to take, anyway. Trusting a caretaker doesn’t come without its perils. Leaving Isco on the bench while implementing a hyper-rigid system didn’t work out at first. The team hit rock bottom in a 3 - 0 defeat away to Eibar, when they couldn’t escape a press (while one of their most press-resistant players, Isco, wasn’t on the field). They struggled again in narrow wins over Huesca and Eibar. Trusting Solari seems to now be paying off. Of late, the team has been picking up steam. Solari seems to have found the balance between rigidity and fluidity -- there is more off-ball movement between the lines, and the now in-form Luka Modric is picking out his teammates in dangerous spots. While Solari may have issues on a personal level with Isco, there are enough tactical reasons for his decisions. But the team has to sustain this form, which is not easy, in order to fully justify not having Isco in the regular scheme. This isn’t a repeat of the Pogba - Mourinho trial, where Mourinho repeatedly threw Pogba under the bus publicly, and the tension was clear. Solari has shown respect to Isco publicly, stating that he “loves” him. Nacho has come out and said that Solari is “on Isco’s side”. Marcelo publicly stated after the 0 - 2 win away to Roma: “I’m not saying that he (Isco) is not working but when you see you have made a mistake you must improve.” Isco is not a lost cause -- his form is within reach, and the squad is on his side. He has come off the bench in most games under Solari, even if the outcome hasn’t all been successful. The team has gone through enough injuries and suspensions this season (and in the past) to assume Isco will always have a chance to claim his spot -- just as he rose in the 2016 / 2017 season amid Bale’s big injury to form a cohesive, control-based midfield alongside Toni Kroos and Luka Modric. But he didn’t crack the starting XI in any big games during this stretch with Bale and Asensio injured. Now Bale and Asensio (neither of whom are in form either) are inching their way back into the team. Marcos Llorente has also resumed training. While he’s not a comparable player positionally to Isco, his emergence on the scene this season means Solari will play either him or Casemiro as the team’s single pivot -- taking away one more starting XI spot as Toni Kroos will no longer be pushed back as a defensive midfielder, which would free up a LCM slot for Isco. Real Madrid are famously thin at the striker position, but have loaded depth in midfield, where the great Isco resides. The ideal scenario for everyone involved is for Solari to unearth the Isco from two seasons ago and get Real Madrid ticking at a fluid tempo, retaining possession high up the pitch and attacking their opponents relentlessly. But whether he can do that, when hungry players like Ceballos, Valverde and Vinicius are exiting the realm of fringe rotation, is a different question. “Competition within the squad is an essential part of football,” Solari told the media ahead of Thursday’s Copa del Rey clash with Girona. “Everyone must feel they have an opportunity and can lose their place [if they don't do well]." Image courtesy of the Press Association

The Rise of Press-Resistant Midfielders

Will Villarreal, Celta Vigo and Athletic Club Survive La Liga's Crowded Relegation Battle?

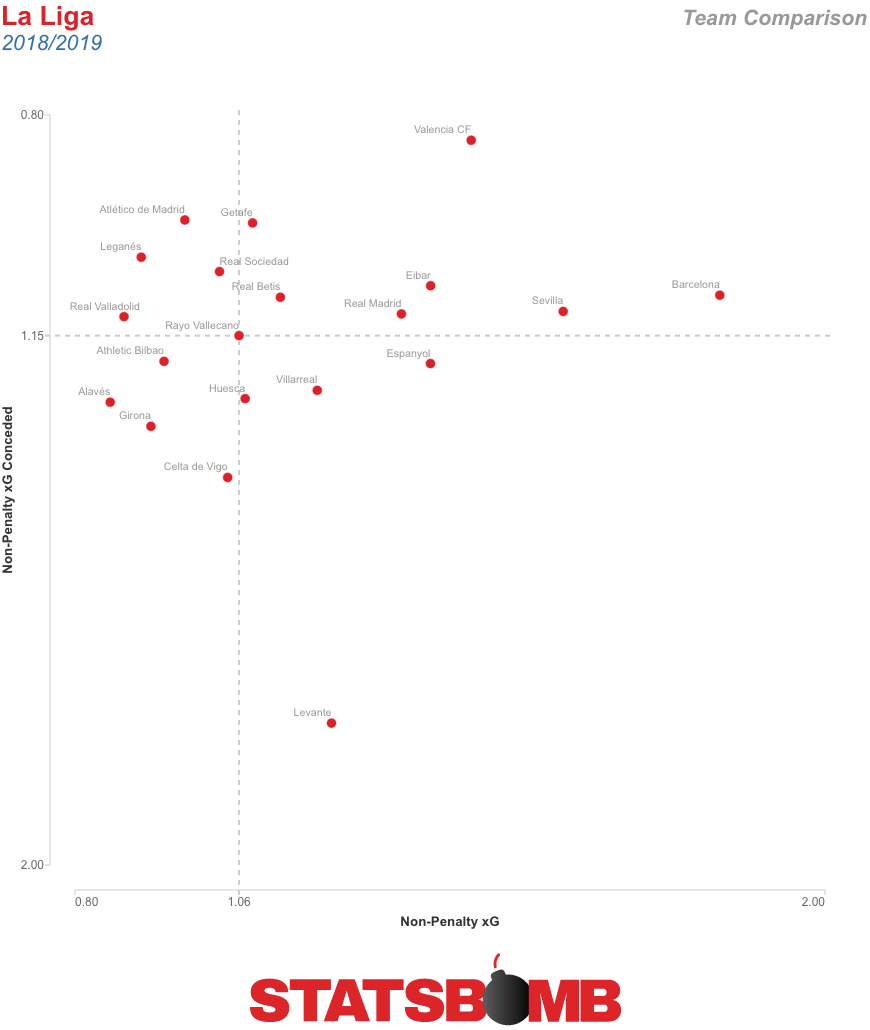

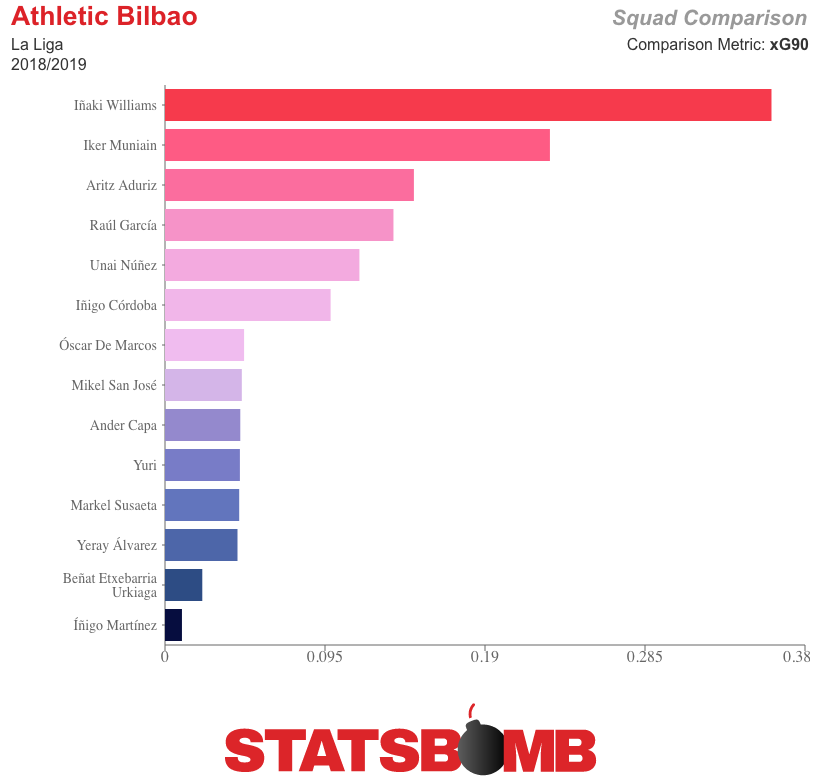

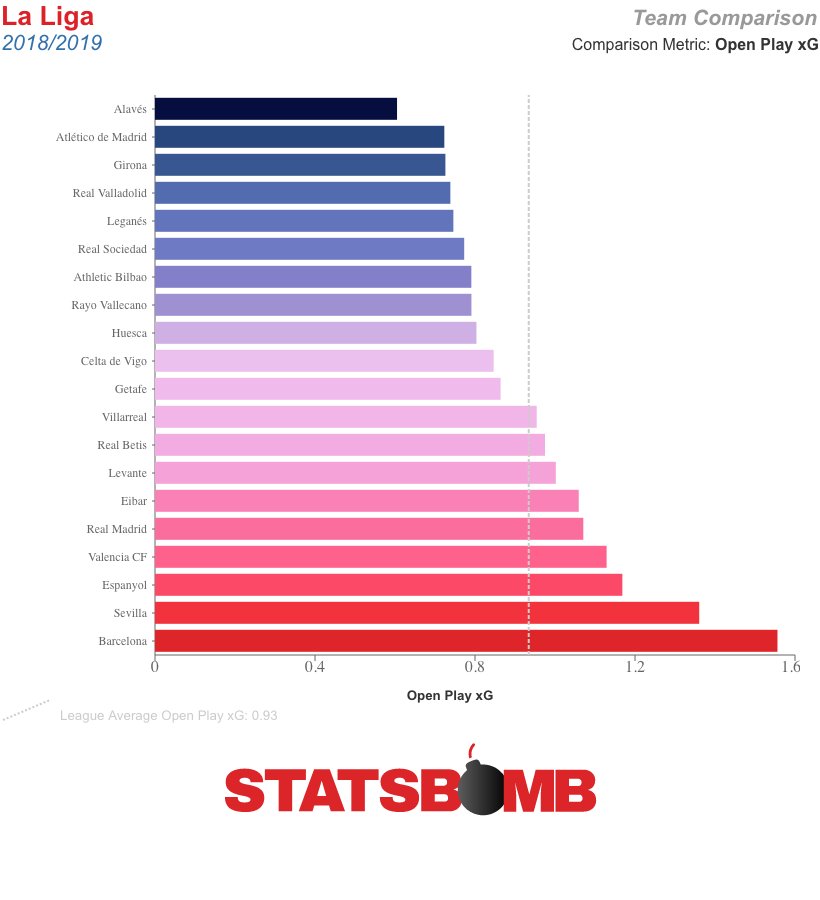

A few things are pretty much settled in La Liga. Barcelona top the pile with the league’s best underlying numbers, while Huesca are rooted firmly to the bottom, nine points from safety and with just two wins to their credit. Atlético Madrid, Real Madrid and Sevilla can be expected to fill the remaining top-four spots. But for the rest of the teams, there is still much left to play for. At the halfway point of the campaign, just nine points separated the team in seventh from the team in 19th -- comfortably less than in any of other “big five” leagues and nearly double the difference between those positions in the Premier League. One would expect Real Betis, Real Sociedad and a Valencia side whose underlying numbers have consistently been much better than results to end up comfortably in the top half, with the potential to challenge surprise sides Alavés and Getafe for fifth and sixth. Eibar and Espanyol have had their ups and downs but can also be expected to finish in mid-table. That still leaves eight teams potentially battling it out to avoid filling the two remaining relegation spots: Athletic Club, Celta Vigo, Girona, Leganés, Levante, Rayo Vallecano, Real Valladolid and Villarreal. Below is a plot of the non-penalty xG for and against for all Primera Division teams so far this season. As James and Ted noted on last week’s StatsBomb podcast, there are a few anomalies. Atlético Madrid consistently outperform xG, and are again doing this time around, sitting comfortably in second with over-performance at both ends of the pitch; Alavés have remained in the top-four race much longer than expected given underlying numbers that are among the league’s worst. But the chart does give us an idea of the strengths and weaknesses of the main relegation candidates.  The teams in the lower left quarter are those who are below average in both attack and defence: Athletic Club, Girona and Celta Vigo. Neither Athletic nor Celta Vigo would have expected to be involved in a relegation battle. With Athletic, the assumption had been that last season’s 16th place finish was the result of poor coaching rather than their underlying talent level. As for Celta Vigo, with attackers like Iago Aspas, Maxi Gómez, Pione Sisto and intriguing youngster Brais Méndez, Celta looked to have enough firepower to be closer to the top 10 than the relegation fight. Both are currently in the lower reaches of the table having already sacked the coaches with which they began the campaign. A solid run of results since Gaizka Garitano replaced Eduardo Berizzo in December has eased some of Athletic’s worries, but they are still far from safe. It is no surprise to see that three of their four best defensive performances this season in terms of xG Conceded have come under Garitano’s command. This is the coach whose Eibar side conceded just 28 times in 42 matches in gaining promotion to the top flight back in 2013-14. Sorting out the team’s defensive problems was always going to be his priority. The key question is whether Athletic will be capable of getting enough goals to secure the points they need. With Aritz Aduriz beginning to lose out in his game attempt to fight the ageing process, Iñaki Williams is bearing the brunt of their goalscoring burden.

The teams in the lower left quarter are those who are below average in both attack and defence: Athletic Club, Girona and Celta Vigo. Neither Athletic nor Celta Vigo would have expected to be involved in a relegation battle. With Athletic, the assumption had been that last season’s 16th place finish was the result of poor coaching rather than their underlying talent level. As for Celta Vigo, with attackers like Iago Aspas, Maxi Gómez, Pione Sisto and intriguing youngster Brais Méndez, Celta looked to have enough firepower to be closer to the top 10 than the relegation fight. Both are currently in the lower reaches of the table having already sacked the coaches with which they began the campaign. A solid run of results since Gaizka Garitano replaced Eduardo Berizzo in December has eased some of Athletic’s worries, but they are still far from safe. It is no surprise to see that three of their four best defensive performances this season in terms of xG Conceded have come under Garitano’s command. This is the coach whose Eibar side conceded just 28 times in 42 matches in gaining promotion to the top flight back in 2013-14. Sorting out the team’s defensive problems was always going to be his priority. The key question is whether Athletic will be capable of getting enough goals to secure the points they need. With Aritz Aduriz beginning to lose out in his game attempt to fight the ageing process, Iñaki Williams is bearing the brunt of their goalscoring burden.  Iker Muniain is very important in terms of ball progression, but his xG contribution is somewhat inflated from having scored five times from inside the six-yard box. He is not a regular shooter. Raúl García and Iñigo Córdoba are, but they primarily do so from average-to-poor positions. However, January signing Ibai Gómez is a slightly more discerning shooter (and was especially so last season at Alavés) and should add enough to the Athletic attack to eventually help steer them to safety. An injury to Williams would, though, be difficult to overcome. Goals shouldn’t be a problem for Celta Vigo. Last season, they had the league’s fourth-best attack in terms of xG, at 1.30 per match. But after making a similar start to the current campaign, equalising a poor defensive unit with their attacking potency, subsequent attempts to gain better balance have simply resulted in worsening metrics at both ends of the pitch. Their xG conceded is now the second worst in the division.

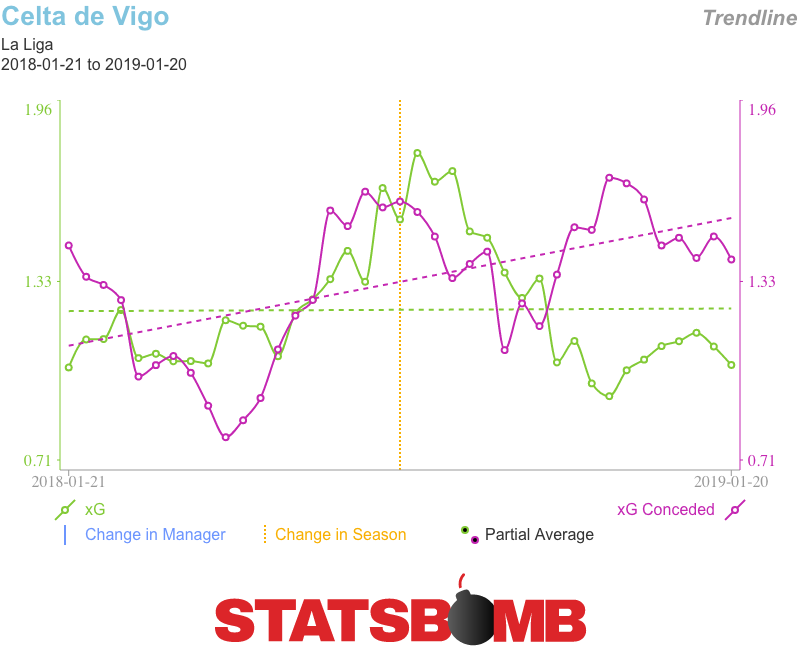

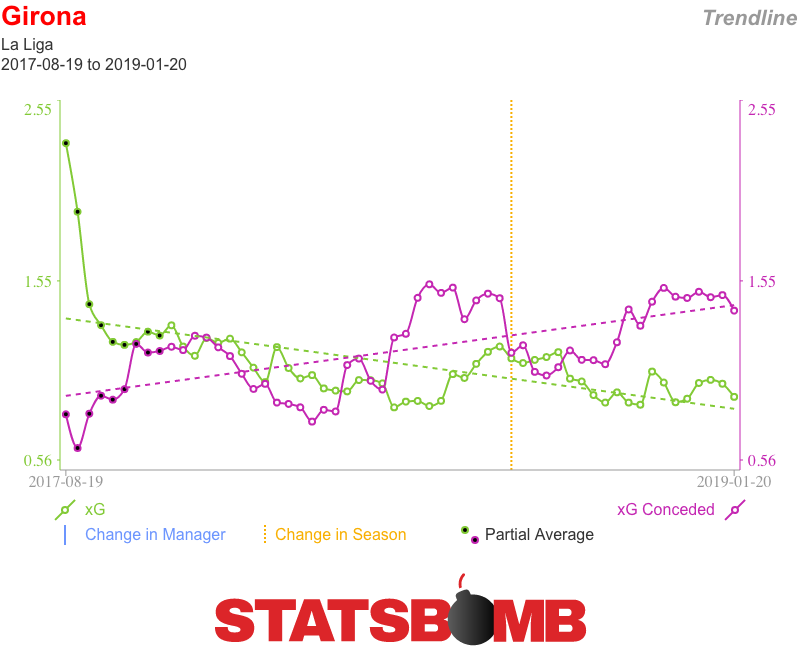

Iker Muniain is very important in terms of ball progression, but his xG contribution is somewhat inflated from having scored five times from inside the six-yard box. He is not a regular shooter. Raúl García and Iñigo Córdoba are, but they primarily do so from average-to-poor positions. However, January signing Ibai Gómez is a slightly more discerning shooter (and was especially so last season at Alavés) and should add enough to the Athletic attack to eventually help steer them to safety. An injury to Williams would, though, be difficult to overcome. Goals shouldn’t be a problem for Celta Vigo. Last season, they had the league’s fourth-best attack in terms of xG, at 1.30 per match. But after making a similar start to the current campaign, equalising a poor defensive unit with their attacking potency, subsequent attempts to gain better balance have simply resulted in worsening metrics at both ends of the pitch. Their xG conceded is now the second worst in the division.  Antonio Mohamed was sacked in mid-November, and new coach Miguel Cardoso, who did impressive work at Rio Ave in his native Portugal before bombing at Nantes, is yet to find an adequate solution. Unless he soon does so, Celta’s seven-season stretch in the top flight is in serious danger of ending. Girona secured a top-10 finish in their debut Primera Division campaign last time out, but they were much less impressive in the second half of the season. They ran a positive xG difference (xGD) of 0.20 per match through their first 19 matches but that dropped into negative territory at -0.26 per match thereafter. New coach Eusebio Sacristán has been unable to arrest that slide, and Girona’s xGD per match this season stands at -0.38.

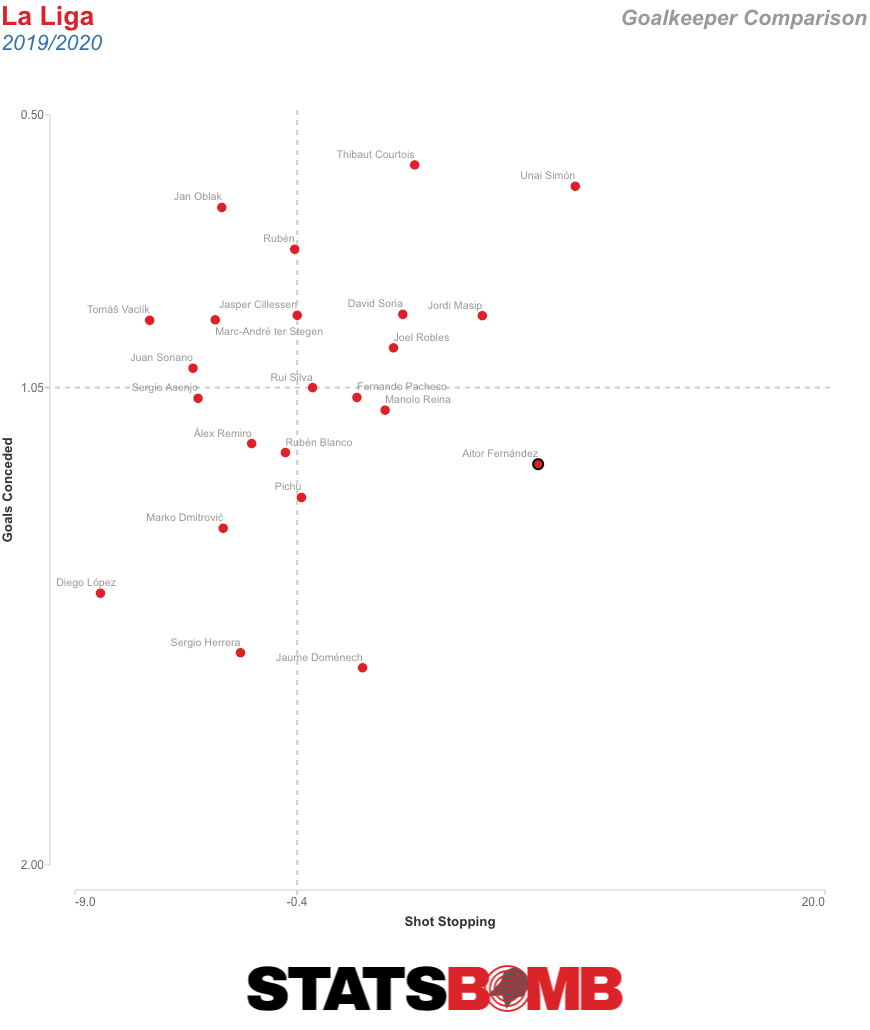

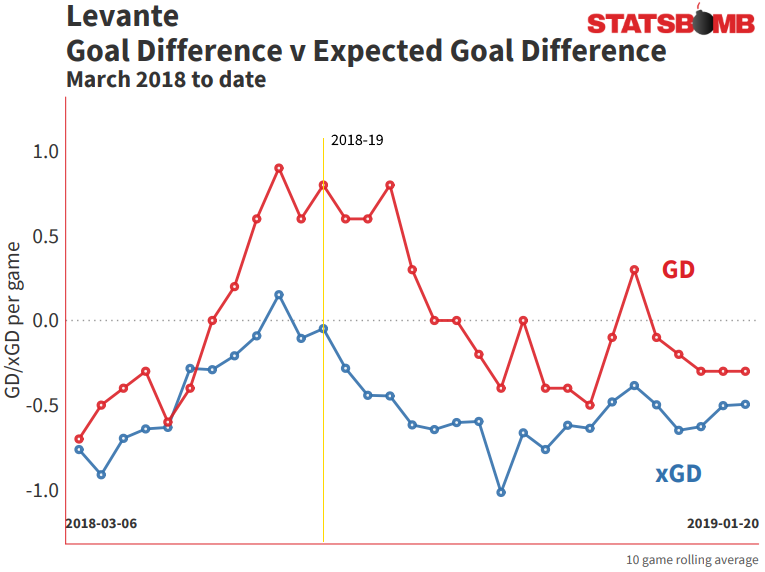

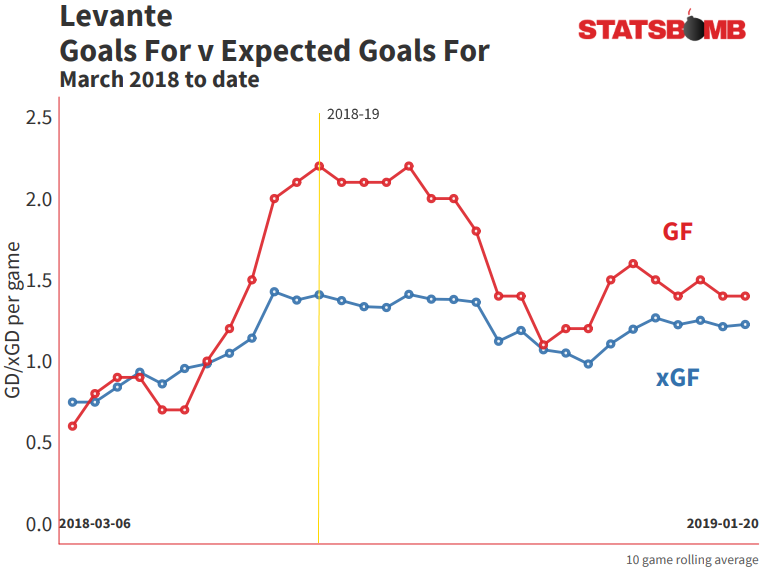

Antonio Mohamed was sacked in mid-November, and new coach Miguel Cardoso, who did impressive work at Rio Ave in his native Portugal before bombing at Nantes, is yet to find an adequate solution. Unless he soon does so, Celta’s seven-season stretch in the top flight is in serious danger of ending. Girona secured a top-10 finish in their debut Primera Division campaign last time out, but they were much less impressive in the second half of the season. They ran a positive xG difference (xGD) of 0.20 per match through their first 19 matches but that dropped into negative territory at -0.26 per match thereafter. New coach Eusebio Sacristán has been unable to arrest that slide, and Girona’s xGD per match this season stands at -0.38.  On their current trajectory, and presuming goalkeeper Yassine Bounou isn’t able to maintain his current stellar performance level of a league-second-best Goals Saved Above Average percentage (GSAA%) of 9.3%, Girona aren’t likely to be far away from the bottom three come the end of the campaign. Those in the lower right of the chart have above average attacks but below average defences: Villarreal and Levante. Villarreal have performed well below expectations. In their pre-season predictions, FiveThirtyEight had them down to finish seventh, with as good a chance (12%) of finishing in the top four as they did of being relegated. Yet here they are now are, in the bottom three, with an over 40% chance, again via FiveThirtyEight, of going down. A cursory glance at Villarreal’s numbers would suggest they should still be able to claw themselves to safety. Their xGD per match of -0.05 is the 11th best in the division, and their attack is the eighth best. But that doesn’t tell the full story. While they were probably just a bit unlucky under previous coach Javi Calleja, their numbers have got worse under his replacement Luis García. It is, admittedly, a limited sample of just five matches (at time of writing, including Real Madrid at home), but García’s attempts at tightening up their defensive unit have done more to constrict the attack than benefit the defence. Indeed, lowly Huesca posted their best xG total (2.08) of the season against them. Villarreal failed to address their lack of quality in defence during the summer transfer market, and current reports suggest they might even be minded to allow talented midfielder Pablo Fornals to leave in January in order to fund the purchase of additional defensive options. Given his importance to the team, particularly in terms of ball progression and creativity (Santi Cazorla offers a very similar skillset, but relying on him to stay fit and carry that load for the remainder of the campaign is a big risk), it is move that reeks of a team in panic mode. Levante are the only other side against whom Huesca have posted up an xG total of over two, and their current position in mid-table clashes with their underlying numbers, which are the worst in La Liga. As their position way down the chart indicates, their defence is La Liga’s worst by some distance in terms of xG conceded, at 1.77 per match -- over half a goal more than the league average. Maybe Paco López simply has the Midas touch? When he took over in March 2018, Levante were 17th in the table, just one point above the relegation zone. In their final 11 matches of the campaign, they secured a mammoth 25 points, more than any other side in La Liga. Their underlying numbers improved, but not that much. That has again carried into this campaign, with Levante performing much better than would be expected given their underlying numbers, as this plot of actual vs. expected goal difference shows. This season, their defensive performance is about par. The over-performance is being driven by their attack.

On their current trajectory, and presuming goalkeeper Yassine Bounou isn’t able to maintain his current stellar performance level of a league-second-best Goals Saved Above Average percentage (GSAA%) of 9.3%, Girona aren’t likely to be far away from the bottom three come the end of the campaign. Those in the lower right of the chart have above average attacks but below average defences: Villarreal and Levante. Villarreal have performed well below expectations. In their pre-season predictions, FiveThirtyEight had them down to finish seventh, with as good a chance (12%) of finishing in the top four as they did of being relegated. Yet here they are now are, in the bottom three, with an over 40% chance, again via FiveThirtyEight, of going down. A cursory glance at Villarreal’s numbers would suggest they should still be able to claw themselves to safety. Their xGD per match of -0.05 is the 11th best in the division, and their attack is the eighth best. But that doesn’t tell the full story. While they were probably just a bit unlucky under previous coach Javi Calleja, their numbers have got worse under his replacement Luis García. It is, admittedly, a limited sample of just five matches (at time of writing, including Real Madrid at home), but García’s attempts at tightening up their defensive unit have done more to constrict the attack than benefit the defence. Indeed, lowly Huesca posted their best xG total (2.08) of the season against them. Villarreal failed to address their lack of quality in defence during the summer transfer market, and current reports suggest they might even be minded to allow talented midfielder Pablo Fornals to leave in January in order to fund the purchase of additional defensive options. Given his importance to the team, particularly in terms of ball progression and creativity (Santi Cazorla offers a very similar skillset, but relying on him to stay fit and carry that load for the remainder of the campaign is a big risk), it is move that reeks of a team in panic mode. Levante are the only other side against whom Huesca have posted up an xG total of over two, and their current position in mid-table clashes with their underlying numbers, which are the worst in La Liga. As their position way down the chart indicates, their defence is La Liga’s worst by some distance in terms of xG conceded, at 1.77 per match -- over half a goal more than the league average. Maybe Paco López simply has the Midas touch? When he took over in March 2018, Levante were 17th in the table, just one point above the relegation zone. In their final 11 matches of the campaign, they secured a mammoth 25 points, more than any other side in La Liga. Their underlying numbers improved, but not that much. That has again carried into this campaign, with Levante performing much better than would be expected given their underlying numbers, as this plot of actual vs. expected goal difference shows. This season, their defensive performance is about par. The over-performance is being driven by their attack.

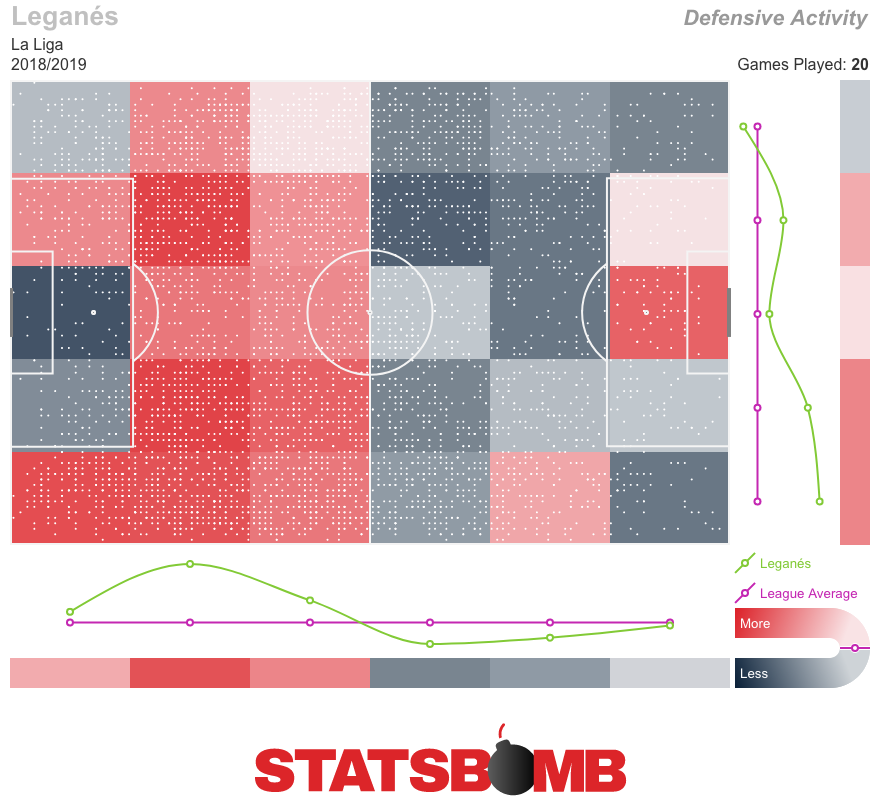

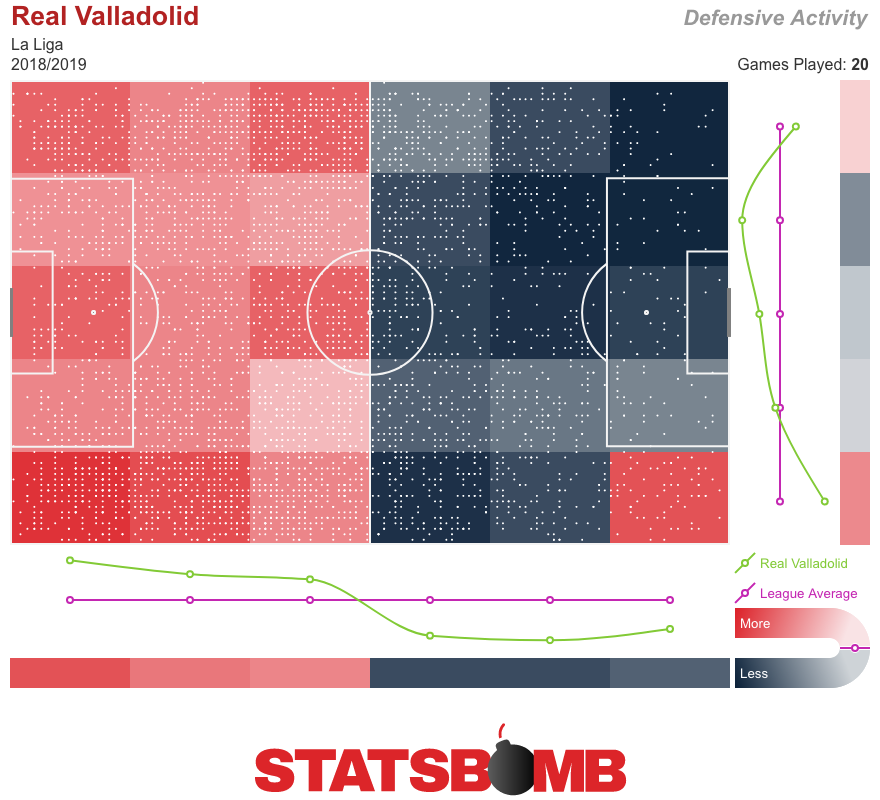

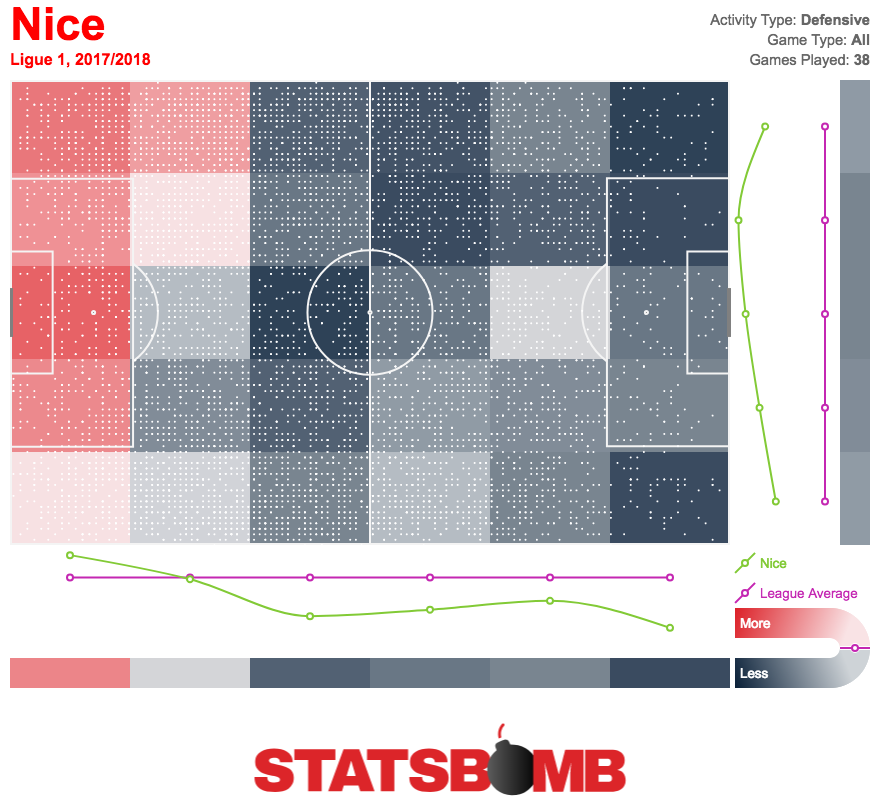

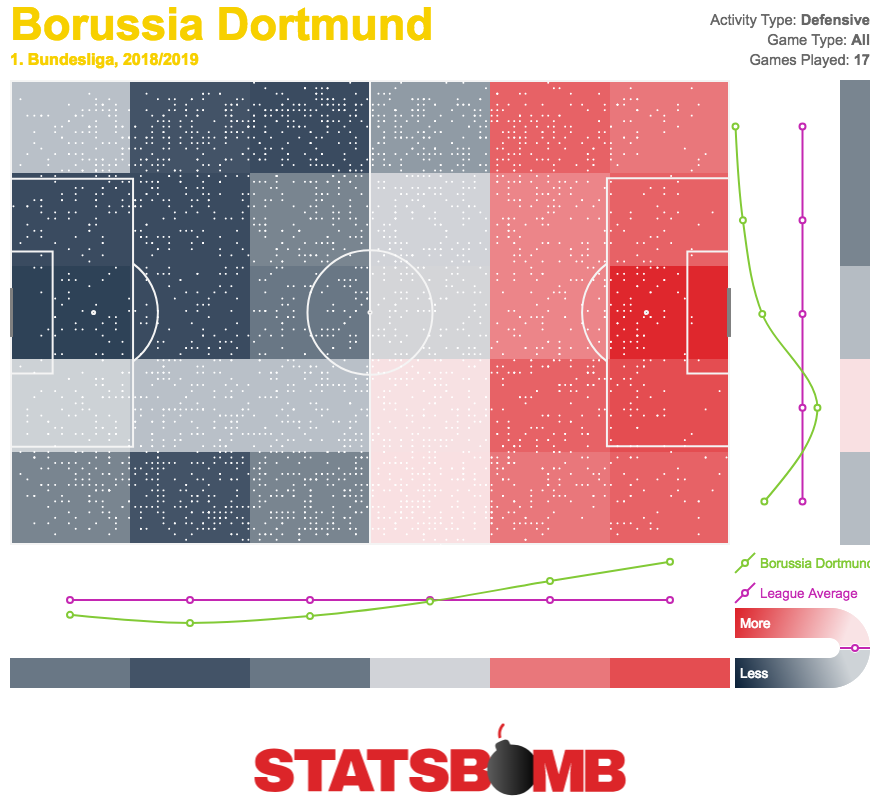

You’d still expect Levante to finish closer to the bottom three than the top 10, but it would nevertheless be a surprise if they were relegated from their current position. Those in the upper left quarter have above average defences but below average attacks: Leganés and Real Valladolid. Both teams are amongst the cagiest in the division, with only matches involving Atlético Madrid joining theirs in averaging less than 2xG. Their defensive activity maps show that they are deep-lying teams who do a lot of defending in their own halves.

You’d still expect Levante to finish closer to the bottom three than the top 10, but it would nevertheless be a surprise if they were relegated from their current position. Those in the upper left quarter have above average defences but below average attacks: Leganés and Real Valladolid. Both teams are amongst the cagiest in the division, with only matches involving Atlético Madrid joining theirs in averaging less than 2xG. Their defensive activity maps show that they are deep-lying teams who do a lot of defending in their own halves.

They are also sides who struggle to create much in open play.

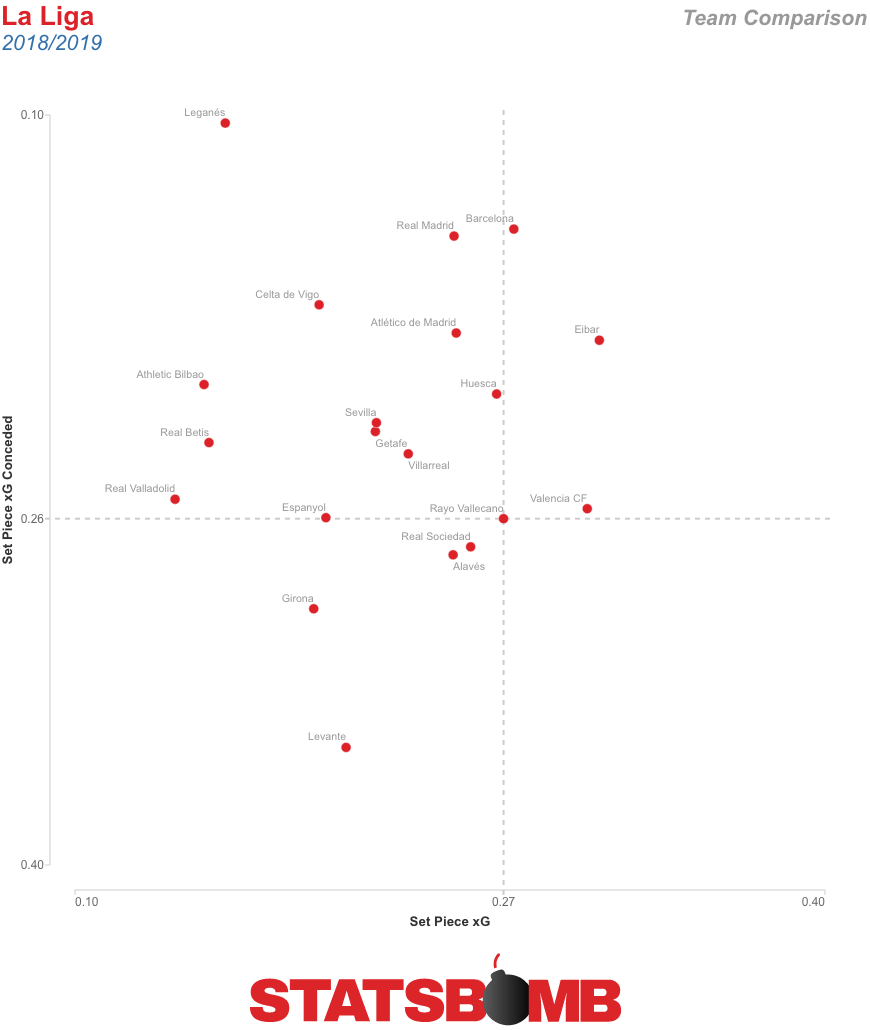

They are also sides who struggle to create much in open play.  The difference between them, and what makes Leganés the more likely of the two to survive, is how well they both attack and defend set-pieces. While Real Valladolid hold the marginal advantage in terms of Open Play xGD (-0.13 to -0.17), on set-pieces, Legánes are marginally better in attack and much better in defence.

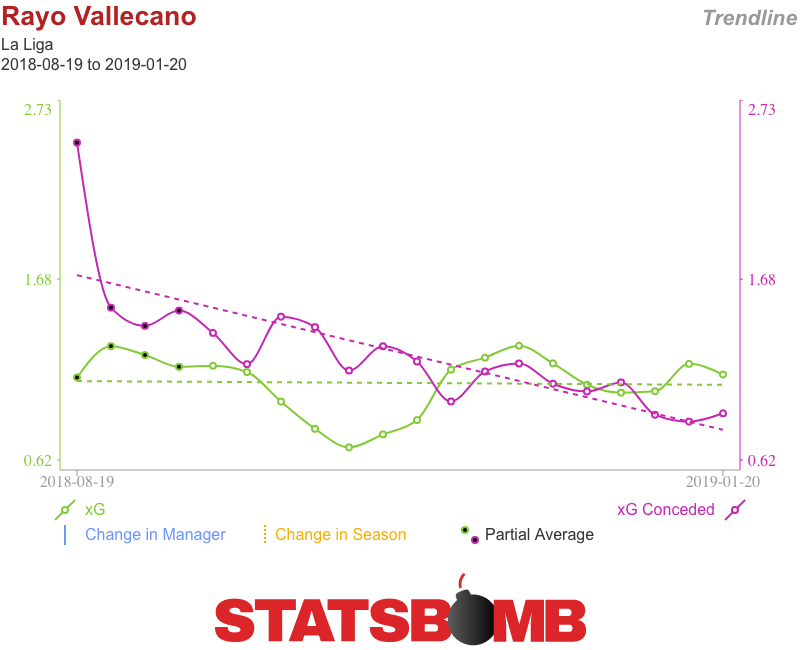

The difference between them, and what makes Leganés the more likely of the two to survive, is how well they both attack and defend set-pieces. While Real Valladolid hold the marginal advantage in terms of Open Play xGD (-0.13 to -0.17), on set-pieces, Legánes are marginally better in attack and much better in defence.  Valladolid are currently over-performing their set-piece xG at both ends (in attack, primarily off the back of three direct strikes from long-range free-kick), but Leganés are generally creating the better looks whilst giving up lower-quality opportunities to their opponents. That can be expected to play to their advantage from hereon out. Finally, we have Rayo Vallecano, perfectly straddling the average line at both ends of the pitch. After a poor start to the season, improving defensive metrics have at least given them a fighting chance of avoiding the drop. With Giannellli Imbula doing his laconic, Mousa-Dembele-without-the-defensive-numbers thing in midfield, José Ángel Pozo and Óscar Trejo linking into the final third and Raul De Tomás offering a solid goal threat -- ably supported by Adrian Embarba and Alvaro Garcia -- they now look a decent side.

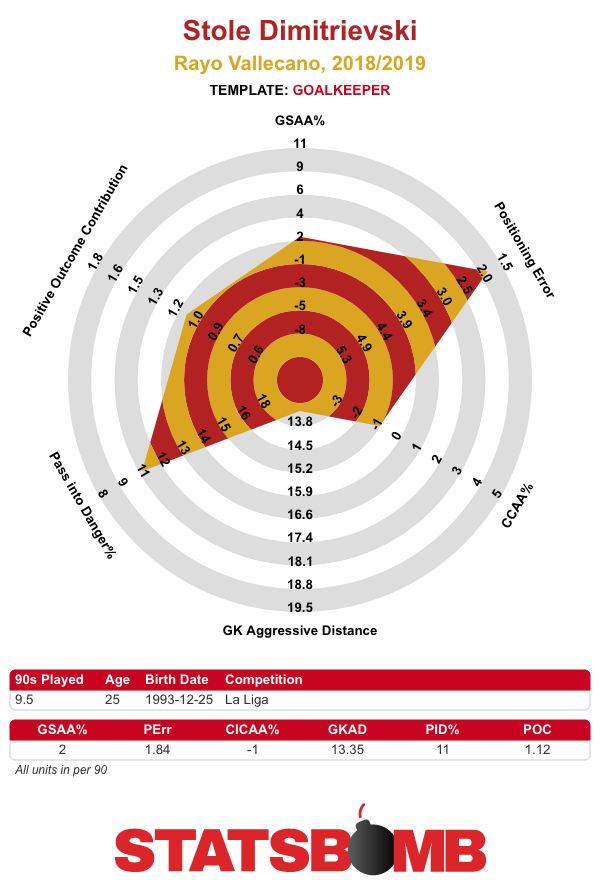

Valladolid are currently over-performing their set-piece xG at both ends (in attack, primarily off the back of three direct strikes from long-range free-kick), but Leganés are generally creating the better looks whilst giving up lower-quality opportunities to their opponents. That can be expected to play to their advantage from hereon out. Finally, we have Rayo Vallecano, perfectly straddling the average line at both ends of the pitch. After a poor start to the season, improving defensive metrics have at least given them a fighting chance of avoiding the drop. With Giannellli Imbula doing his laconic, Mousa-Dembele-without-the-defensive-numbers thing in midfield, José Ángel Pozo and Óscar Trejo linking into the final third and Raul De Tomás offering a solid goal threat -- ably supported by Adrian Embarba and Alvaro Garcia -- they now look a decent side.  Perhaps most importantly, a simple change between the sticks has yielded swift results. Early season number one Alberto García had a GSAA% of -8.1% in his 11 starts. Since taking over in mid-November, Stole Dimitrievski has proved to be a much more effective shot-stopper, posting a GSAA% of 2.1%. Garcia conceded four more goals than an average goalkeeper could be expected to; Dimitrievski has conceded one less.

Perhaps most importantly, a simple change between the sticks has yielded swift results. Early season number one Alberto García had a GSAA% of -8.1% in his 11 starts. Since taking over in mid-November, Stole Dimitrievski has proved to be a much more effective shot-stopper, posting a GSAA% of 2.1%. Garcia conceded four more goals than an average goalkeeper could be expected to; Dimitrievski has conceded one less.  Initially in danger of slipping away from the pack like Huesca behind them, Vallecano have now inserted themselves into a multi-team scrap that is only likely to be decided in the final weeks of the campaign. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

Initially in danger of slipping away from the pack like Huesca behind them, Vallecano have now inserted themselves into a multi-team scrap that is only likely to be decided in the final weeks of the campaign. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

The Tightest Title Race in England: Arsenal, Chelsea and Manchester City in a FA WSL Sprint to the Finish

Coming into this season, the FA Women’s Super League was ready for a slug-fest between Chelsea and Manchester City.

The pair had been the dominant forces in English football since 2015, when the (London) Blues won their first WSL title and the Sky Blues were fresh off the back of their first major trophy since the injection of cash into the club’s operation*.

*NB: City fans, and former players, will be keen for it to be made clear that the club has had a women’s side since the 1980s, something which wasn’t common at the time. City and football historian Dr Gary James has done, and continues to do, work documenting this, for example.

The pair were first and second in every season from 2015 to 2018, including the WSL Spring Series that took place as the league switched from a summer to winter schedule in 2017. Arsenal, the once-premier force in the women’s game (they won nine league titles in a row between 2003 and 2012), were relegated to third-place. Perennial bronze medal winners, the new-money pair even muscling into the Gunners’ stranglehold of the FA Cup, which they have won 14 times since 1992/93.

https://twitter.com/RichJLaverty/status/1087030291926011904?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw

But at the start of the 2018/19 season, everything seemed to have changed.

It took Chelsea four games to score their first league goal (granted, their opening match had been against City). Not long after, they were thrashed 5-0 by Arsenal, who were rolling over anything and everything in their path. Manchester City had had a slow start too, including a disappointing 2-2 draw to Bristol City.

With expected midtable clubs like Birmingham City and Reading enjoying good starts, Chelsea and City found themselves in a congested pack behind the Gunners.

Back to normality, and a three-horse race

Now, though, the league has shaken itself out. City are top by a point, albeit having played one game more than Arsenal who sit in second. Joe Montemurro’s team also have a game in hand over Chelsea, who are a further two points back in third.

The weird thing is that each of these three teams have their own distinct story. You have Arsenal, the behemoths rearing their head after a brief slumber, a monstrous footballing phoenix. Chelsea, the slow starters. And City, the moneyed club with a stadium of their own** and a target on their back, who’ve shown rare signs of weakness.

**All 11 teams in the WSL are affiliated with a professional men’s team in the English professional leagues, but most do not share match-day facilities with them. Many play at local(ish) stadiums of a different men’s team that is in the lower professional leagues or non-league (for example, Arsenal play at Boreham Wood’s ground; Chelsea, AFC Wimbledon’s). Manchester City play at a purpose-built stadium for City’s academy and women’s teams on the club’s ‘Etihad Campus’, a couple of minutes’ walk from the main 55,000-seater Etihad Stadium. There is an argument that playing at an unfamiliar ground to fans of the club is a factor in holding back attendances, and playing on the same site as the men’s team, accessible by the same car parks and tram stop, would appear to be an advantage in encouraging a live audience for City’s women.

Arsenal

If this wasn’t professional football, everyone would have stopped playing with Arsenal because they’re too good. They’ve made whipping posts of everyone, and their performances have matched the results.

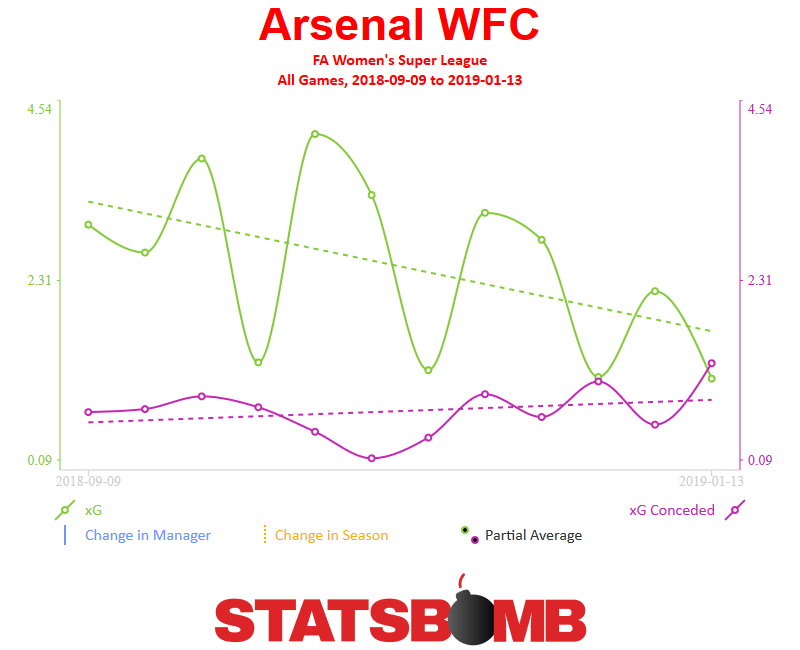

Expected goals is a stat that judges the quality of chances that teams have. The difference between Arsenal’s expected goals and their opponents’ in individual matches has given them an expected goals difference of 2.0 or more in six of their 12 league games.

It’s only once been negative once, in their recent 2-1 win over Chelsea (and even then, only just, -0.17).

Chelsea

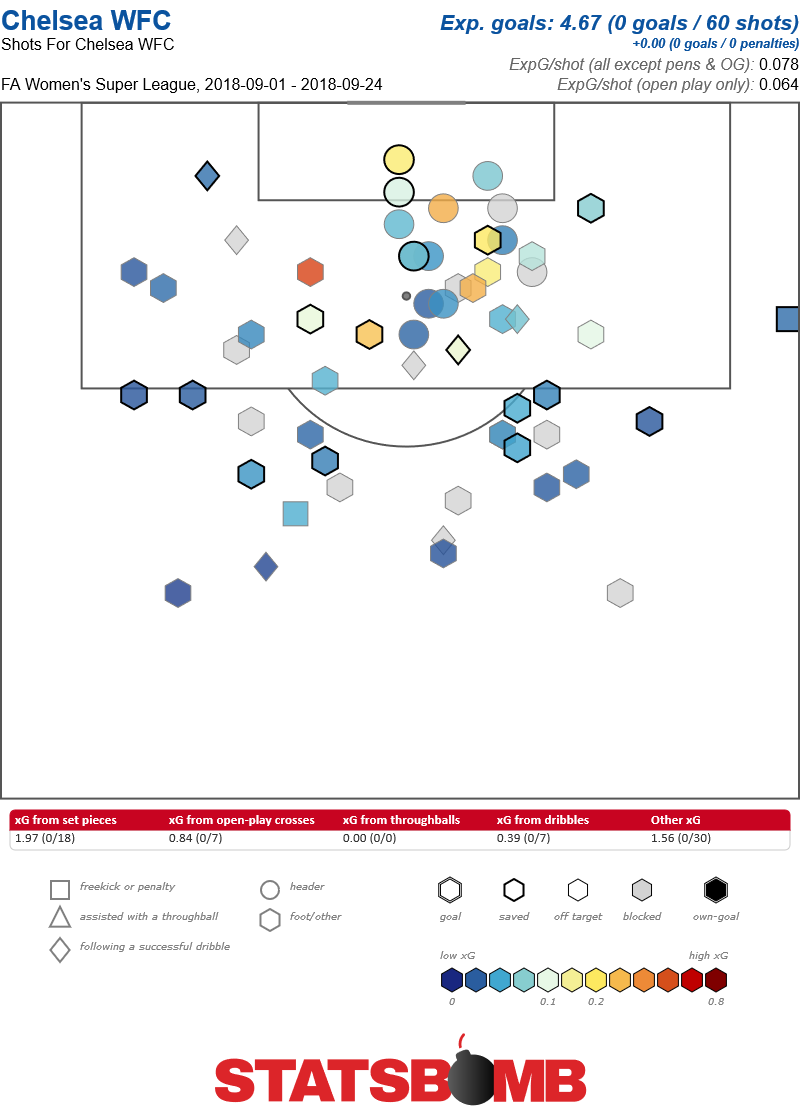

By rights, Chelsea should probably have enjoyed a similarly hot run of results to the Gunners though.

Emma Hayes’ team created chances worth 4.66 expected goals in their opening run of three goalless games.

They, like Arsenal, have had six games where their expected goals total has been over two (although four of these have come in their last five). Their only games of struggle have been against the other two of the Big Three.

Manchester City, though, have genuinely struggled against the two teams in the next tier of the league, Birmingham and Reading.

Manchester City

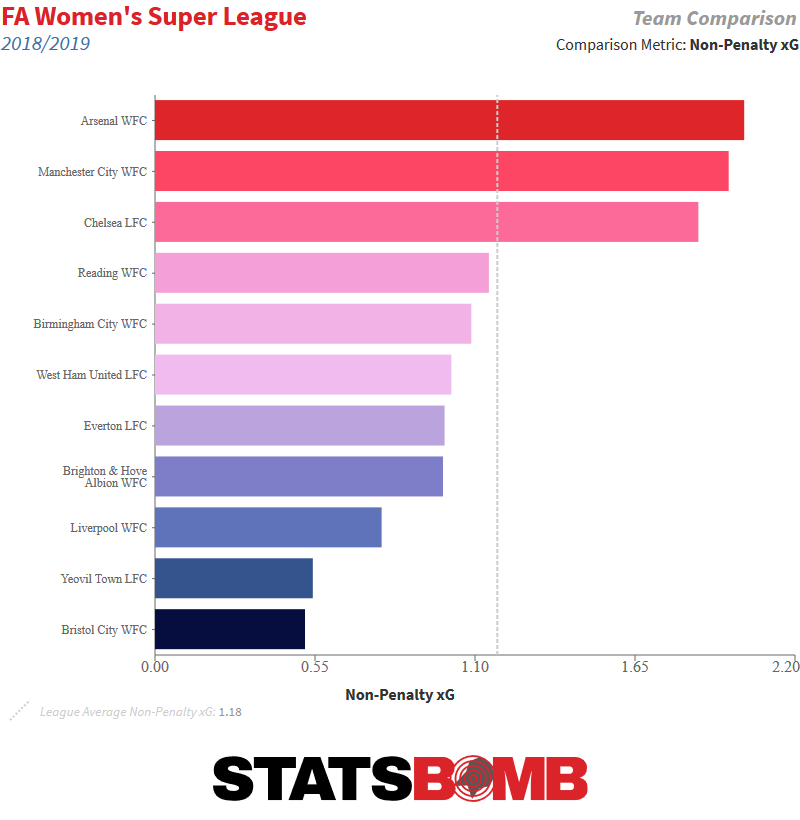

Nick Cushing’s City have now played Birmingham - who were coached by new Orlando Pride manager Marc Skinner - home and away. City’s expected goal difference across the two games against the Midlands side is just +0.45. Chelsea and Arsenal both beat that in one match.

Similarly, when City drew 1-1 against Reading, the expected goal scoreline read 1.56-1.08; in other words City created more, but only just, and a draw was a reasonable result. Meanwhile Chelsea won their only meeting with the Royals so far 1-0, though expected goals suggests the scoreline could have been much larger, and Arsenal deservedly whomped Reading 6-0. Looking at expected goals created per match against other top five teams, City has clearly one much less in attack than their two competitors for the league.

Fans of City will be bemoaning these performances, but fans of women’s football as a whole will probably be encouraged. Birmingham and Reading are proving that it’s not just the big guns, backed by copious amounts of money, who can compete (Durham, one of the few teams to halt Manchester United’s dominance of the second-tier, the FA Women’s Championship, are an encouraging example of this too).

Fans of City will be bemoaning these performances, but fans of women’s football as a whole will probably be encouraged. Birmingham and Reading are proving that it’s not just the big guns, backed by copious amounts of money, who can compete (Durham, one of the few teams to halt Manchester United’s dominance of the second-tier, the FA Women’s Championship, are an encouraging example of this too).

The title race

The three teams are clear behemoths at the top of the league and, with the table so tight, every match counts.

This weekend sees Arsenal travel to Reading and Chelsea host Birmingham (under new manager Marta Tejedor); City will be hoping that the WSL middle-class will slow their rivals down. It isn’t long until the next crunch match at the top either, with the Manchester side due to welcome Chelsea on February 10.

The final game of the top three mini-league, Arsenal vs City, is scheduled for the last day of the season. It could well be a title-decider. It could well, if the edge that the Gunners’ underlying numbers are to be believed, be Arsenal’s first league title since 2012.

The WSL is the title race you should be keeping an eye on.

Header image courtesy of the Press Association

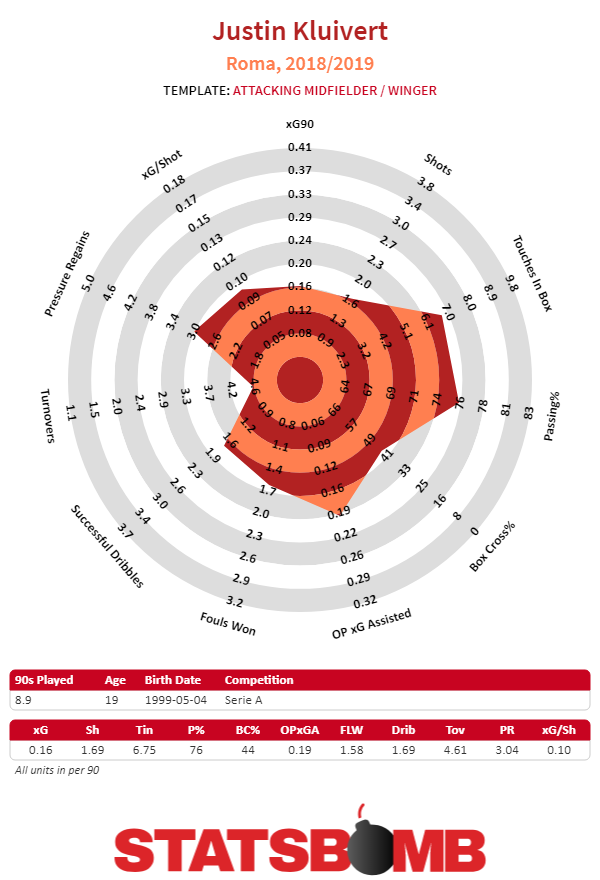

Justin Kluivert's Steady Serie A Progress

Justin Kluivert’s move from Ajax to Roma during the summer of 2018 was a fascinating deal. On finances alone the transfer wasn’t anything extraordinary, though Ajax did fairly well in recouping just over €17 million considering Kluivert had only a year left on his contract. Two things made the move interesting: Kluivert was leaving at age 19 for a Champions League level club in Serie A after just over 3000+ minutes at Ajax across two seasons, and the club he was going to in Roma had a large squad so game time might’ve been an issue during his first season. Leaving so early in his development was risky.

Kluivert was a precocious young talent at Ajax. When isolated on the left wing he was consistently able to get a step on opponents, and he displayed some acumen for left footed crosses which hinted at the possibility of having added value as a two-footed winger. Kluivert was a high end prospect, and it wasn't hard to see his appeal. It was fair to say that he wasn't quite a generational talent, but certainly someone who was on the high end of 18-21 year-old prospects in European football.

As it stands now, Kluivert is on pace to play at least 1500 Serie A minutes, which isn’t an insignificant amount of playing time for a teenager and makes the bet he took on himself look smarter in retrospect. In an alternative world where his contract wasn’t running down, getting another full season at Ajax and producing large numbers in the Eredivisie would have been good for his development, but the situation he's currently in at Roma has not proven to be a hindrance when it comes to game time. With the jump up in competition, it comes as no surprise that Kluivert’s production to this point has not been eye popping.

Initially, one would look at Kluivert’s production and be disappointed given the hype that surrounded him at Ajax. He’s basically been the equivalent of a league average attacking midfielder or winger. But context is key. Given that Kluivert went from Ajax who have such a talent advantage over everyone in the Eredivisie not named PSV, to a top level, but not necessarily elite, Serie A club in Roma, his production was likely to take some dip. Also when accounting for age, and Roma's overall weirdness this season, it's not terribly hard to explain why Kluivert hasn't hit the ground running in Italy. This isn't to say that it's great that he's having the season he's had, but there shouldn't be any immediate worries.

You'll see flashes of what made Kluivert such a highly rated prospect with his ability to beat individuals off the dribble. The disparity between his completed dribbles and turnovers is a little bit worrying because that level of discrepancy as a wide player is when you're starting to take things off the table. Kluivert hasn't found it as easy to dart his way through the opposition as he did in the Netherlands, but the moments that Kluivert have conjured up are strong enough that I tend to believe he'll increase his dribble numbers to a rate that's more acceptable for his archetype of player. He's got a special level of acceleration that not a lot of wingers are blessed with.

Kluivert's decision making has not been much of a worry to this point. He's been able to use his athleticism in a functional manner to get a step on his marker and turn it into something positive for the team. His 2.14 open play key pass per 90 rate is second among Roma players who've played at least 600 minutes, and his open play expected goals assisted per 90 rate of 0.19 is tied for third. Certainly there have been instances where Kluivert cuts inside and instead of laying it off to a teammate and going for the safe option tries something else and it doesn't end up going well, but we're starting to see more instances of him doing productive things during semi-transition opportunities.

If there's one area in Kluivert's game to monitor moving forward, it would be his crossing and how much of a threat he is as a left footed crosser. If Kluivert turns out to be a sub-elite (or better) overall crosser as a wide player, it'll raises his ceiling even higher because you could utilize him in numerous ways. He could play as a more traditional winger on the right side where he could use his burst + crossing abilities to create chances for teammates in the box, or he could be an inverted winger and give the opposing fullback worries with being able to either cut inside with speed or deliver pinpoint crosses from closer to the touchline. To this point, Kluivert has completed 1.35 crosses per 90 minutes and has a 48% success rate on crossing attempts this season, which is the highest completion rate among Roma players with 600 or more minutes. I don't expect that figure to last, if only because that's such a high success rate that the odds are more likely it goes down. I was a bit skeptical that he was this amazing left-footed crosser, but he did have confidence in attempting left-footed crosses in the Eredivisie and that's translated with Roma. Projecting confidence as a crosser overall is half the battle, and the sample size is growing that he's a quality deliverer from the wide areas.

If there's one area in Kluivert's game to monitor moving forward, it would be his crossing and how much of a threat he is as a left footed crosser. If Kluivert turns out to be a sub-elite (or better) overall crosser as a wide player, it'll raises his ceiling even higher because you could utilize him in numerous ways. He could play as a more traditional winger on the right side where he could use his burst + crossing abilities to create chances for teammates in the box, or he could be an inverted winger and give the opposing fullback worries with being able to either cut inside with speed or deliver pinpoint crosses from closer to the touchline. To this point, Kluivert has completed 1.35 crosses per 90 minutes and has a 48% success rate on crossing attempts this season, which is the highest completion rate among Roma players with 600 or more minutes. I don't expect that figure to last, if only because that's such a high success rate that the odds are more likely it goes down. I was a bit skeptical that he was this amazing left-footed crosser, but he did have confidence in attempting left-footed crosses in the Eredivisie and that's translated with Roma. Projecting confidence as a crosser overall is half the battle, and the sample size is growing that he's a quality deliverer from the wide areas.  Kluivert has also begun to use his speed and intellect to cause real danger to the opposition, whether it be for him individually or opening up a passing lane for a teammate. If there's one positive thing to take from Kluivert's season in Serie A so far, it's that going from the Eredivisie to a top 5 league has not made much of a difference with his off-ball athleticism. He was an elite athlete in Holland when it came to sprinting into open spaces, and that's translated fairly well in Italian football.

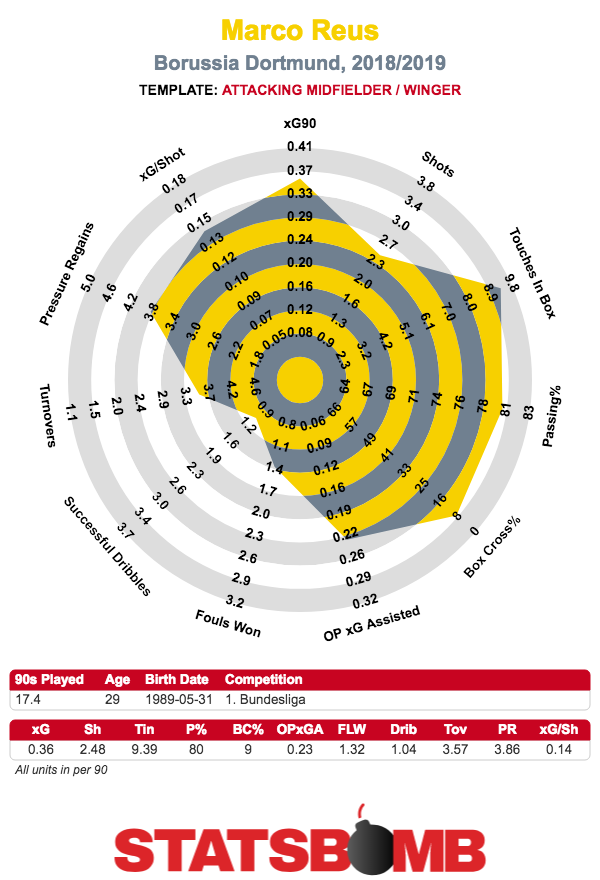

Kluivert has also begun to use his speed and intellect to cause real danger to the opposition, whether it be for him individually or opening up a passing lane for a teammate. If there's one positive thing to take from Kluivert's season in Serie A so far, it's that going from the Eredivisie to a top 5 league has not made much of a difference with his off-ball athleticism. He was an elite athlete in Holland when it came to sprinting into open spaces, and that's translated fairly well in Italian football.  On some level, it is a bit weird to be so effusive of a player who has produced okay results in league play but doesn't have numbers that jumps off the screen. Justin Kluivert hasn't hit the ground running in the same way that Jadon Sancho has at Dortmund where he's been a sensation. You can certainly nitpick at Kluivert's game: he has taken some bad shots from the left halfspace. With the current squad that Roma have, it's hard to envision Kluivert becoming a high volume shot taker so that makes it a bit harder to achieve a noteworthy xG contribution. If Kluivert doesn't turn out to be a very good-great crosser, that also chips away a bit at his overall value as well. It'll also be curious to monitor whether Kluivert turns out to be an above average shooter once there's a greater sample size of shots in Serie A, because some of his finishes in the Eredivisie made you wonder if that was his destiny But the moments Kluivert has had in Serie A play have been encouraging enough that those who were high on him coming into this season shouldn't be too worried about his progress, not to mention that he is averaging a 0.45 goals + assists per 90 rate as a 19 year old, which is nothing to sneeze at. The best thing that can be said about Justin Kluivert's season is that he hasn't look overwhelmed against Serie A competition to this point, and while he isn't light the world on fire in Italy, being a credible attacking player as a teenager is a positive sign for future stardom. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

On some level, it is a bit weird to be so effusive of a player who has produced okay results in league play but doesn't have numbers that jumps off the screen. Justin Kluivert hasn't hit the ground running in the same way that Jadon Sancho has at Dortmund where he's been a sensation. You can certainly nitpick at Kluivert's game: he has taken some bad shots from the left halfspace. With the current squad that Roma have, it's hard to envision Kluivert becoming a high volume shot taker so that makes it a bit harder to achieve a noteworthy xG contribution. If Kluivert doesn't turn out to be a very good-great crosser, that also chips away a bit at his overall value as well. It'll also be curious to monitor whether Kluivert turns out to be an above average shooter once there's a greater sample size of shots in Serie A, because some of his finishes in the Eredivisie made you wonder if that was his destiny But the moments Kluivert has had in Serie A play have been encouraging enough that those who were high on him coming into this season shouldn't be too worried about his progress, not to mention that he is averaging a 0.45 goals + assists per 90 rate as a 19 year old, which is nothing to sneeze at. The best thing that can be said about Justin Kluivert's season is that he hasn't look overwhelmed against Serie A competition to this point, and while he isn't light the world on fire in Italy, being a credible attacking player as a teenager is a positive sign for future stardom. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

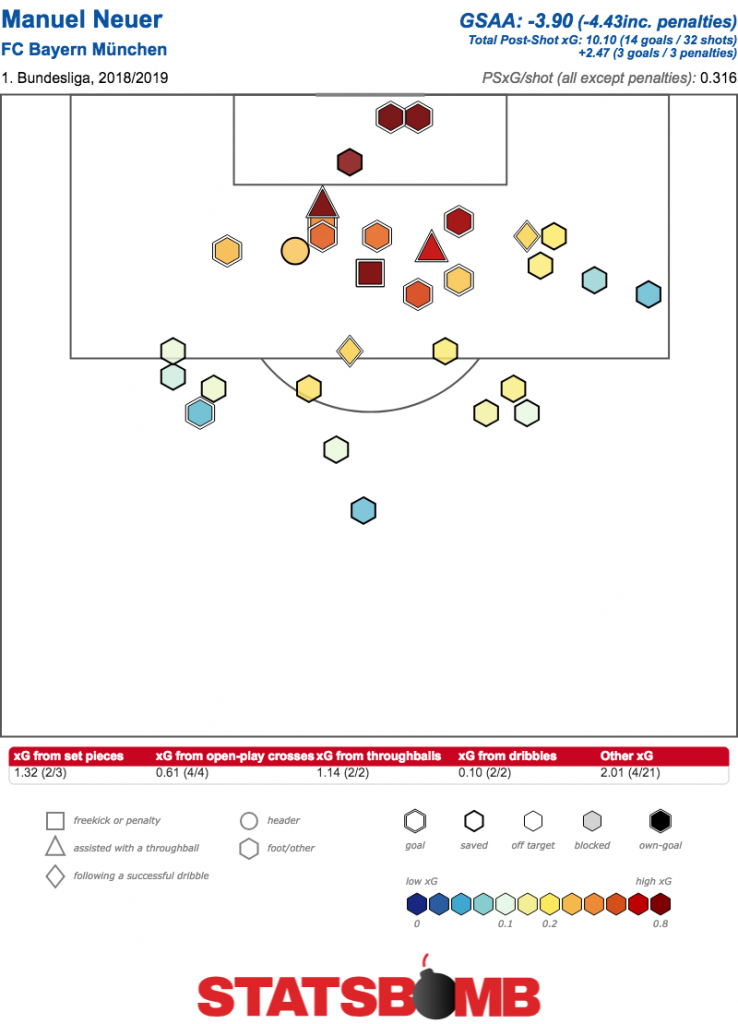

The xClaimables! Measuring Keeper Aggressiveness

The work of demystifying the keeper position never ends.

Earlier this year StatsBomb released it’s post-shot expected goal model.

The idea was to use our keeper and defensive positioning to help build a model that accurately reflected the shots keepers were facing. Next we’ve one lots of work codifying distribution, trying to measure how and where keepers pass the ball. And finally, we’ve begun work on the third major area of a keeper’s game, command of his box. What we aim to do is bring the same level of context to keeper claims as we’ve done to shots and passing.

Let’s dig in.

Our basic conceptual approach was to look at balls that keepers have the opportunity to claim, similarly to how we might look at shots. Figure out how likely any given ball is to be claimed by the keeper and then, in light of that, evaluate how often keepers are coming to claim the balls they face against an average keeper. The idea here is to go beyond just looking at how often a keeper claims balls into his area and take into account how difficult those balls are to claim in the first place. That way we can avoid looking at a keeper who faces only easy crosses and thinking their dominant, while overlooking a keeper who manages to come for, and claim, a lot of more difficult balls. Look at the claimable balls a keeper faces, figure out how many of those balls a keeper would come for on average, and then evaluate an individual keeper against that average.

As always, with new data, some important caveats exist.

We don’t know how this data will act over the long term. We don’t know how much variance there is, what’s signal and what’s noise.

What it can do right now is help us better understand what keepers have done over the games that have been recorded. Saying “a keeper has been very aggressive coming for the ball” is a very different statement than saying “he is an aggressive keeper.” The data can tell us the first thing, it can’t, on its own tell us the second (at least not yet). Ok, enough preamble, here are some actual numbers and pictures and things you need to know. Keepers simply don’t, or can’t, claim the vast majority of balls. In our numbers, there have been over 10,200 claimable balls in the Premier League this season.

We’d expect, on average, keeper to attempt to claim only 788. They’ve actually attempted to claim 752. They’ve had an 88% success rate. Keeping is an inherently conservative business, one in which mistakes get punished by goals.

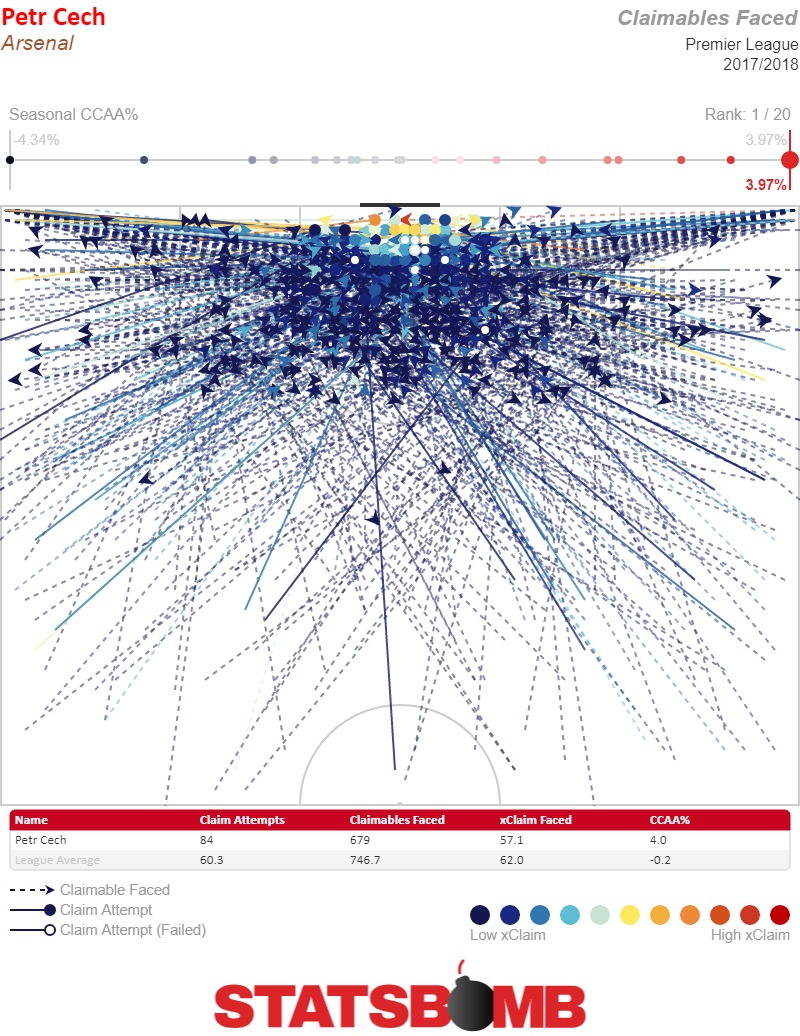

There is a general belief that you shouldn’t come unless you know you can get there. The data reflects that, by and large, that’s how keepers approach the game. This makes for a challenge when it comes to making fun pictures and charts, though. Putting all the balls that a keeper is very unlikely to go and get onto a visualization just makes things really ugly really fast. For example, here’s Petr Cech from last season, with every single claimable ball that came his way.

Yikes.

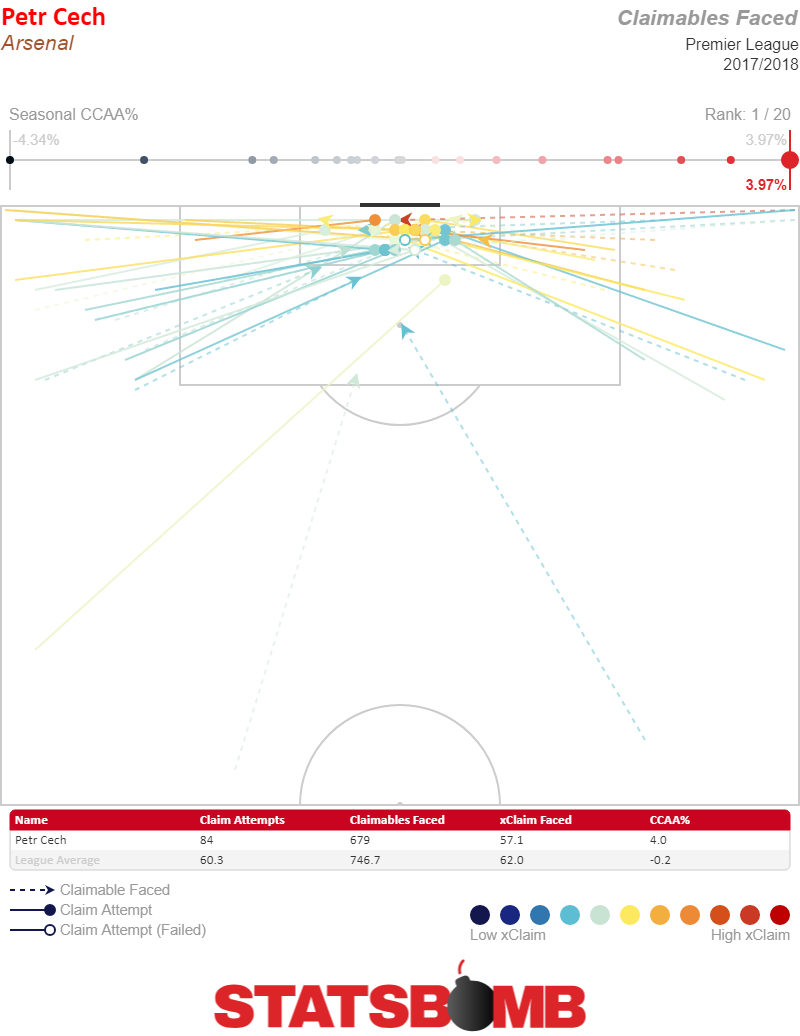

Filtering it down to only the higher likelihood balls makes everybody’s lives a little easier. Here’s how Cech faired that year on balls that had an expected claim value of 0.3 or higher (and look you can use the data however you want but I make sure to shout EUREKA!! In my head every single time I look at an xClaim value).

Voila!

Readability.

It’s a heck of a lot easier to look at the 47 possible balls there than it was to look at the initial map which had 679 claimable balls on it. Looking at that we can actually start to see some individual results from crosses, including a handful of the dreaded “claim attempt (failed)” variety. There’s no question though that there is a tradeoff here between granularity and completeness. On the flip side, if we’re not concerned with granularity we can just use heatmaps.

Hurray!

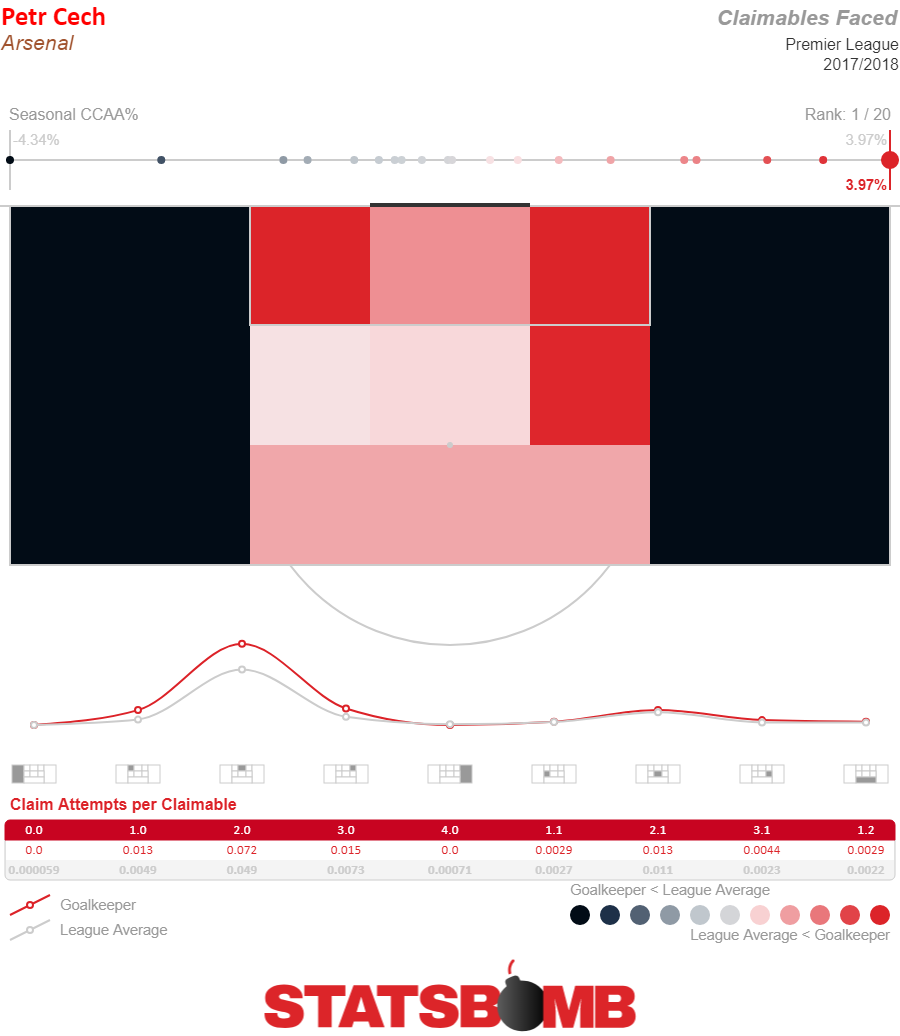

Want to know how aggressive Cech was at coming for balls as compared to the rest of the league. We now have a heatmap for that.

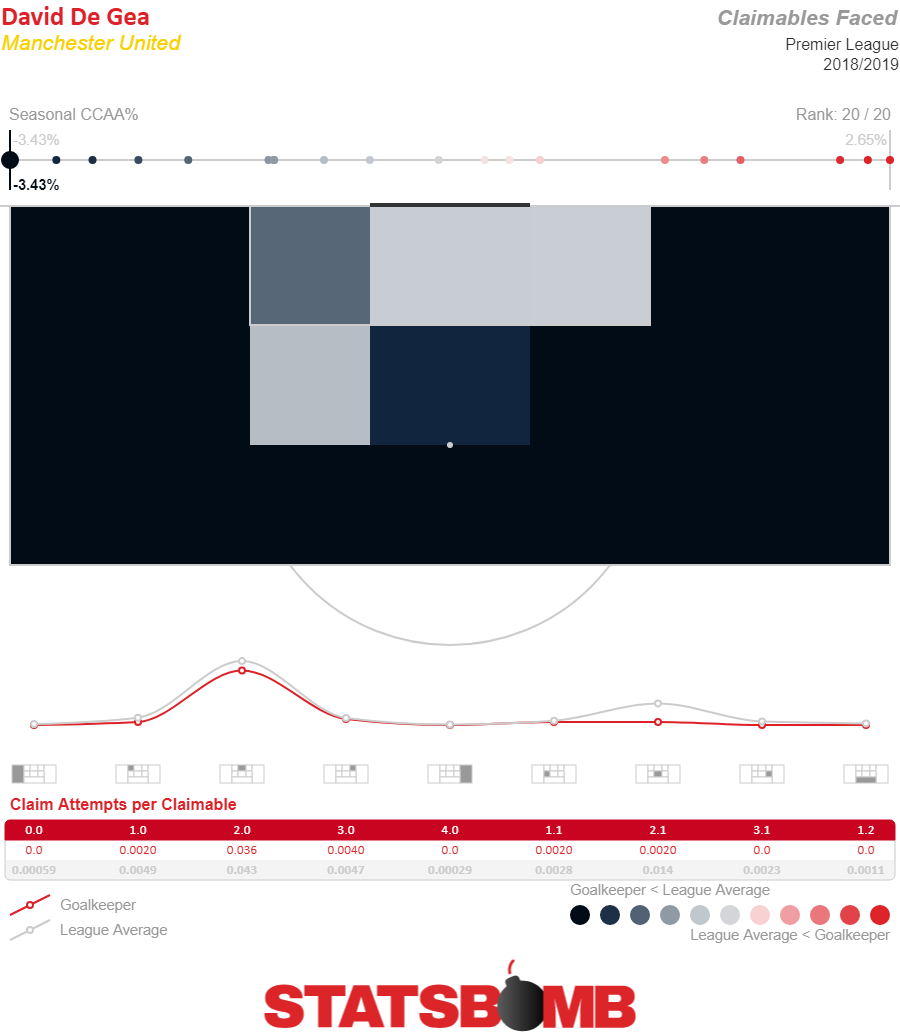

Cech, in keeping with his reputation, comes for a lot of balls. Now, here’s David De Gea from 2017-18 for comparison’s sake.

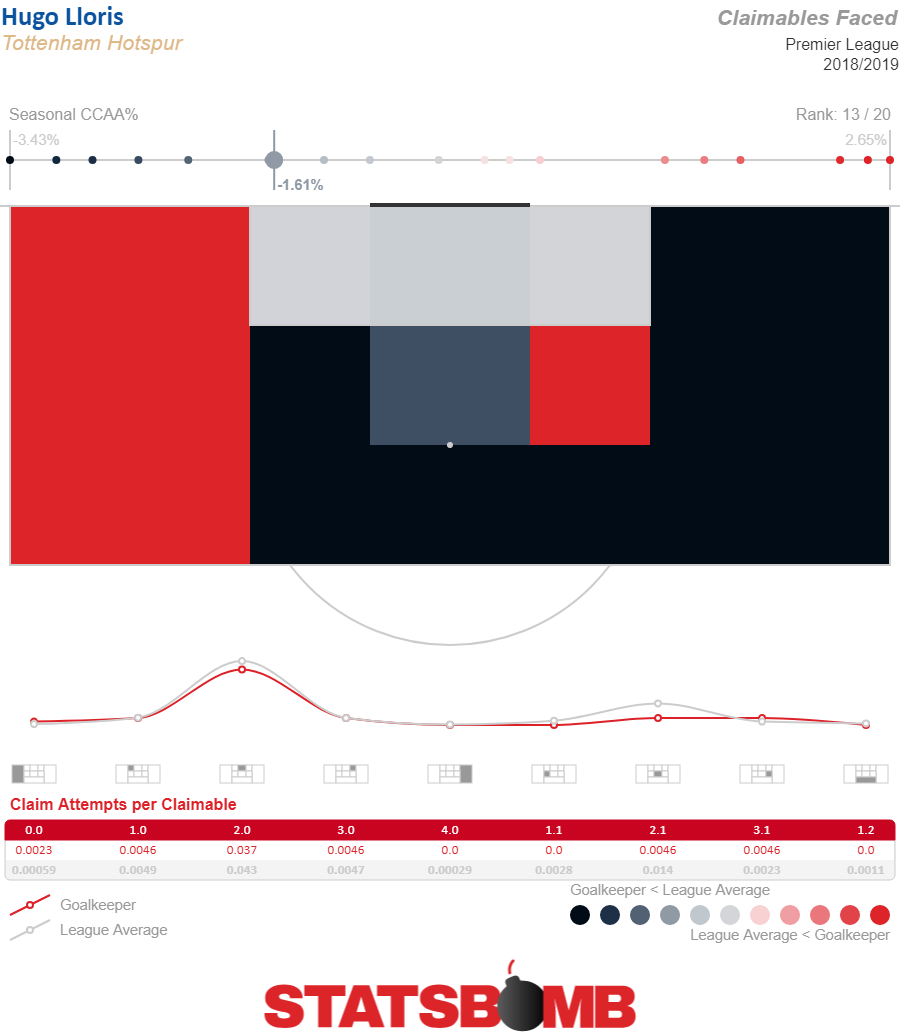

Well that certainly tracks. De Gea has a reputation for not coming off his line a lot and it turns out the data shows…he doesn’t come off his line a lot. Well done data. Ok, with the basics out of the way, how can we start using this data. One way is to help better nail down what players are doing well and poorly. A few weeks ago I wrote about how Hugo Lloris was having a great season. This is broadly true. Spurs defense has been pretty meh, they give up a bunch of shots, but they don’t concede a lot of goals.

It’s all there in the piece, and it all still applies. But a lot of people reacted with incredulity. It sure felt to watchers that Lloris was very error prone. Well, turns out claimables can shed some light on that. Here’s the Lloris heatmap. He’s not particularly aggressive. He comes for 1.61% fewer balls than xClaims would predict. That’s 13th most aggressive in the league.

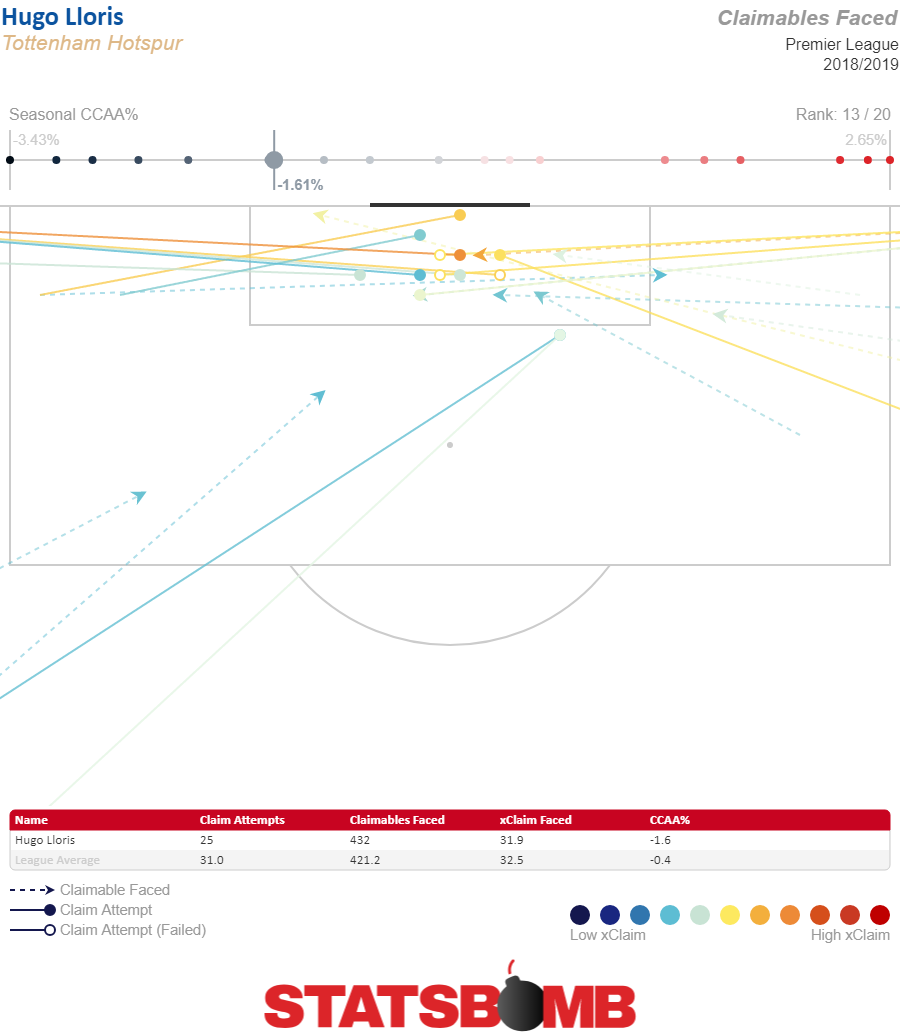

But now, let’s look at them more granularly. Here are the claimable balls with an over 0.3 xClaim value.

Of the 432 balls he’s faced, only 23 have cleared that bar, and he’s come for 13 of them, while xClaims suggests an average keeper would come for only 10. But, as you can see, right smack dab there in the middle, he’s missed three fat chances.

In fact, he’s only claimed 77% of these higher probability balls. We’re slicing things extremely narrowly here, so maybe it’s not great for drawing conclusions about overall performance, but Lloris flapping at three balls which are very gettable, and keepers come for between 30% and 60% of the time is certainly going to stick in the brain as not great.

There are lots of unknowns about that assessment of course. Obviously unsuccessful claims are a bad thing. But, exactly how bad they are is a complicated question. Clearly those errors haven’t really hurt Spurs this season. Are they lucky that’s the case, or is that normal. Rigorously translating keeper’s failing to claim balls that they come for into an actual relationship with goals and therefore results is a problem that’s beyond the scope of what claimables does (at least right now).

It’s a relief, however, to discover in the data an explanation for why Lloris has seemed to be error prone, even as we say with high confidence that error-prone vibe hasn’t impacted how good he is at keeping the ball out of the net. So, that’s your new keeper news. StatsBomb has a fun new tool to examine how aggressive keepers are. Keep it in your thoughts the next time the data request line is open.

Header image courtesy of the Press Association

Do Statistics Explain Kevin-Prince Boateng's Barcelona Transfer?

Kevin-Prince Boateng? That Kevin-Prince Boateng? Are you sure? For real? Why?

It’s been a long and winding road for Boateng. While his younger brother settled down in Bayern Munich’s defense, Kevin-Prince has spent the better part of his career bouncing around Europe. The former Hertha, Tottenham Hotspur, Borussia Dortmund, Portsmouth, Milan, Schalke, Milan again, Las Palmas, Eintracht Frankfurt, and now Sassuolo player has finally made it though. At almost 32 years old he’s been loaned to the big time. He’s going (somehow) to Barcelona.

This isn’t Boateng’s first time playing for an elite team. He was, if not integral, at least involved with Milan the last time they were a true world power. He started 18 matches during the team’s 2010-11 Serie A title winning season, and then 15 matches over each of the next two years as they finished second and third. But that was a soccer playing lifetime ago. Since then he’s remade himself, shifting from an all action midfielder to an unconventional striker. He has played the bulk of his minutes for Sassuoulo in that role.

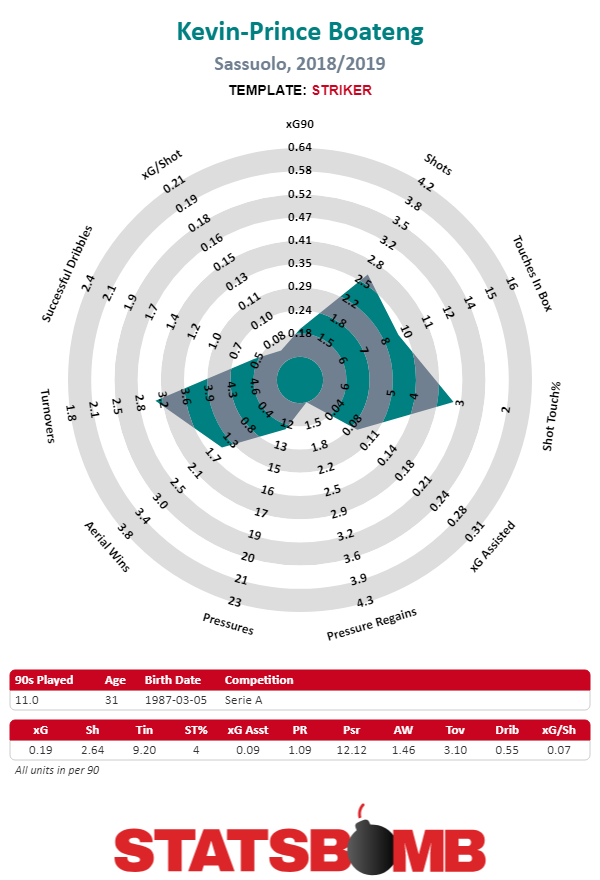

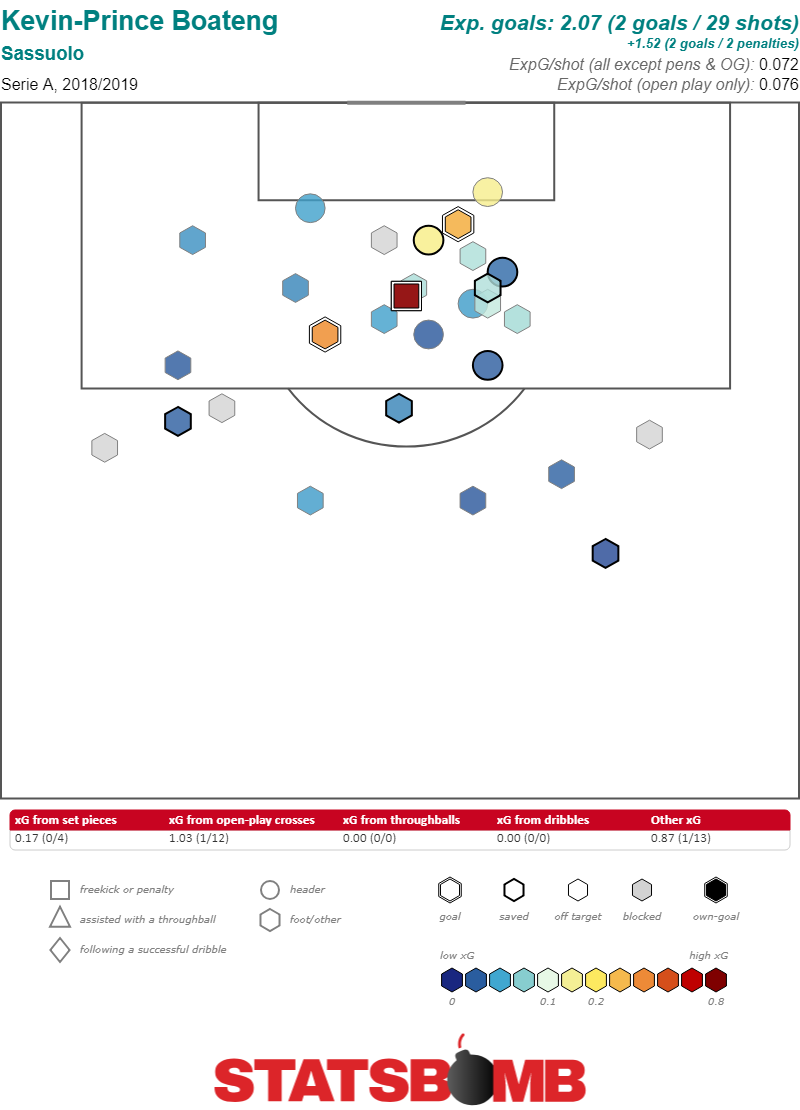

His baseline stats don’t really suggest there’s much to write home about though.

He doesn’t take very many shots, 2.64 per game is extremely mediocre for a forward. And the shots that he does take are terrible. His 0.07 xG per shot is literally off the charts bad for our radars. There’s no worse combination of outcomes for a striker than only being able to manage taking a small number of really unlikely shots.

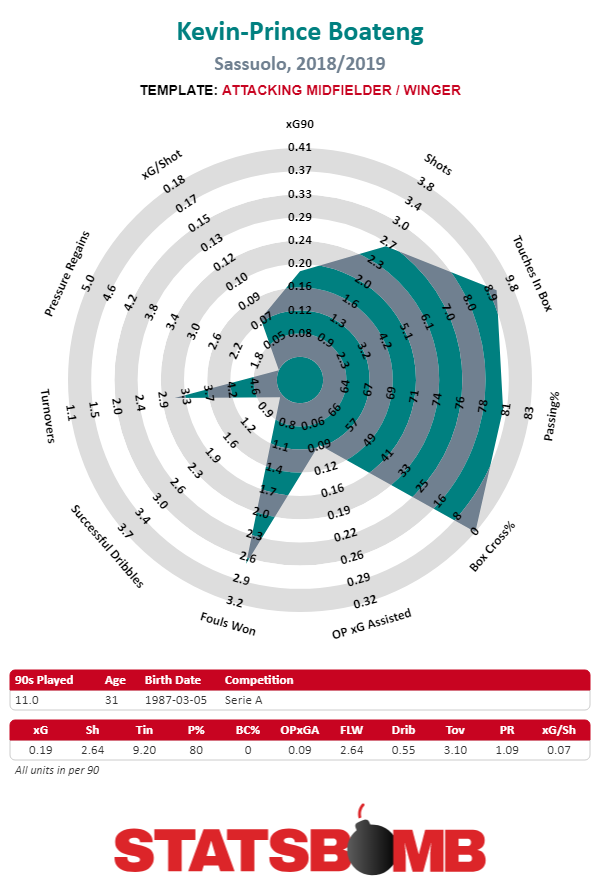

Perhaps there’s something else to his contributions though? Given that he is a former midfielder and an unconventional striker at best, maybe there are some distributional aspects to his play that the numbers fail to account for. Perhaps he’s dropping deeper and creating chances for runners in behind him, or he’s an integral part of an aggressive pressing team, where he defends from the front? If that’s the case it also doesn’t show up in the numbers. Here’s how he appears on the attacking midfield radar.

It’s a slightly larger blob, but it’s not actually more impressive. His average number of touches in the box for a striker shows up impressively on the attacking midfielder template, and his pass completion percentage is pretty high. But that’s about it. There’s nothing here that suggests he’s creating a lot of opportunity for others. His expected goals assisted from open play per 90 is an exceedingly low 0.09. If he’s doing something creative with the ball, it’s not showing up in the shots he’s creating for his teammates.

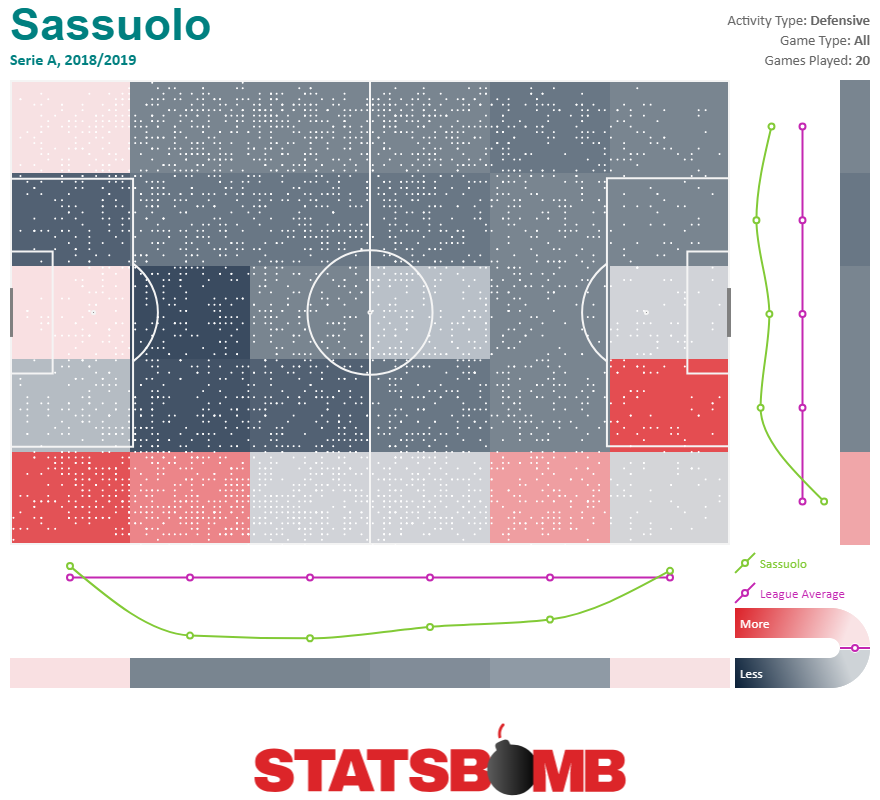

In Boateng’s defense, Sassuolo play the game at a very slow pace. They’re actually slightly more invested in possession that you might expect from Serie A’s 12th place club. They play 533 passes a game, tied with Roma for the sixth most in the league and allow only 442, the sixth fewest. They’re happy to have the ball and not do a ton with it, as long as their opponent doesn’t have a chance to get the ball and attack them. It’s a necessary strategy because when they do give up the ball, they’re completely unable to stop opponents from attacking them.

Despite giving up only 13.30 shots per match, the ninth most in the league, a respectable total, the expected goals they’ve allowed from those shots is a mind blowing, 1.43, tied for the fourth worst in the league. A brief look at their defensive activity map might serve to explain why.

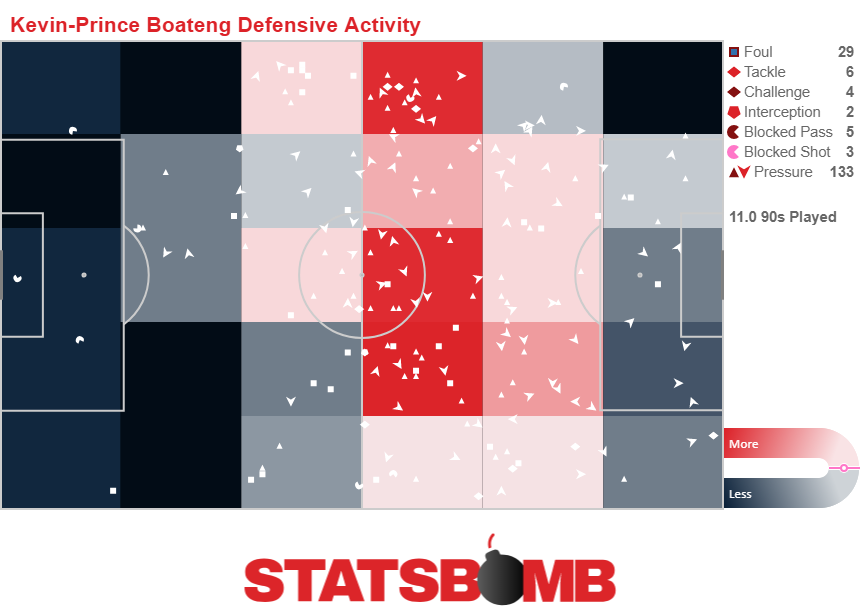

Against that backdrop, Boateng’s defensive contributions from the top look pretty decent. He’s committed to harrying the ball around the halfway line even if the team behind him consists entirely of, well, not much of anything.

Squint and you can almost see the stylistic appeal for Barcelona. Boateng plays up front for a midtable team that plays slowly and methodically. They insist on working the ball out of the back and are extremely patient in possession. That’s sort of Barcelona-ish. And while they turn all that possession into a mediocre number of terrible shots (a process which Boateng is an integral and negative part of) presumably when surrounded by superstar teammates that won’t be nearly as large a problem.

And defensively you can definitely see a role for Boateng as a closer. If Barcelona have a lead, bringing in Boateng for somebody like Ousmane Dembele or even Luis Suarez to shift that emphasis from attacking to defending makes some sense. Boateng can do that, the trade off will be that he’ll add much much (much much much) less on the attacking end, so much less that the trade off may not be worth it.

The question remains though. Why? It’s true that if you torture the numbers, and the scouting just right you can gin up a narrowly define role that Boateng makes sense in for Barcelona, but he’s not the only player that would make sense in that role. It’s not hard to find players that will willingly defend from the front in a substitute role. It’s especially not hard to find ones that are under 30. And while getting Boateng assures that you’re finding an unconventional attacker who is used to playing in a possession oriented system, it also assures that you’re getting an attacker who doesn’t give you much output in that system.

The benefit of being Barcelona is that there’s a lot of wiggle room to make mistakes at the margins. Going and getting Boateng on loan, whatever the reason, won’t hurt this squad overall. They’ve acquired better players for more money than Boateng who have flopped at providing frontline depth while not slowing the super team down (whither art thou Arda Turan). The main cost though is the opportunity cost. Bringing in Boateng to fill this role means not bringing in somebody younger and potentially better to fill that role.

Slice the numbers just right and it’s possible to make an argument that explains what role Boateng will fill at Barcelona. That’s fine, as far as it goes. But no matter how long you look you’ll never find a good reason for Barcelona going and getting a mediocre 32 year old to be the one to fill that role. That decision will remain a mystery

Header image courtesy of the Press Association

Callum Hudson-Odoi and the Challenges of Developing Possible Stars

Jadon Sancho is blowing the doors off the Bundesliga. Callum Hudson-Odoi is sitting on the bench in the Premier League. The juxtaposition of the two has set off the latest round of an ongoing discussion about player development. How often should young prospects play? What is the best way to get them to fulfill their full potential? In short, how should development work? It’s useful to ground this conversation in an awkward, but little talked about, fact. Most footballing prospects will simply never be good enough to play for a top European club. It doesn’t matter what magic sauce you sprinkle on them, how you mold, which kinds of tender loving care, or game time or training clubs devote to them. Pay them a lot early on, or pay them nothing, in the end for most prospects it doesn’t matter. Most prospects simply don’t have what it takes. This isn’t surprising, but it can get subsumed by the visibility of the exceptions to that rule. The Class of ’92, the famed La Masia generation, players like Harry Kane, they may not quite be unicorns, but they are at the very least Sumatran Rhinos. The reality is that no matter how well a team develops their own in house talent it will always be easier, though not cheaper, to simply wait for everybody else to do the developing, and then pick the best of the crop. Against that backdrop clubs are, in effect, trying to answer two questions at the same time. First, how good is this player right now, and second, both more importantly, and more difficultly, how good will this player become in the future? In effect, the answers to those two questions determine how a team should proceed.

Not Good Enough Now, Not Good Enough in the Future