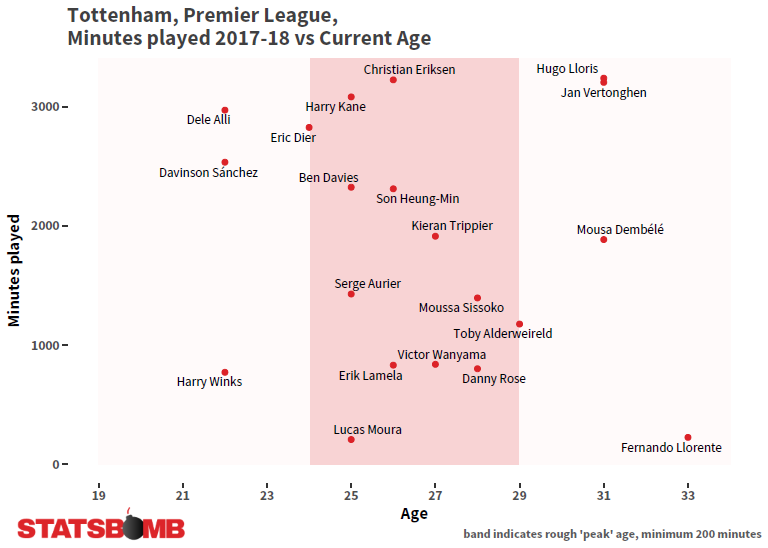

Third, second and third. Those are Tottenham’s last three league finishes yet they find themselves overlooked by the betting markets, who place them squarely as fifth favourites for this year’s Premier League. The same was true prior to last season. Despite a mighty haul of 86 points in 2016-17, Tottenham were generally seen as outsiders for a top four slot with the even bigger money clubs given preference. The 77 points they accrued last season was perhaps closer to their core talent level than the year before, but it still landed them comfortably in third, ahead of Liverpool and seven points clear of Chelsea in fifth. Why are they underrated? To understand partially why we can travel back to Spurs’ first league game after the 2015 transfer window shut, a 1-0 win at Sunderland. For season two of his tenure, Mauricio Pochettino had settled on the core of his team. That game was mildly unusual as Christian Eriksen played no part, something that has only happened for five other league games in four seasons. Mousa Dembélé didn’t feature either, but that didn’t stop it being an extremely familiar Tottenham line-up. Eight of the starting eleven that day are still part of the core first team squad today as well as another five of the substitutes. This is a team that has been together for some years. However, they were a young team then, and have now grown together towards what looks like their peak years:

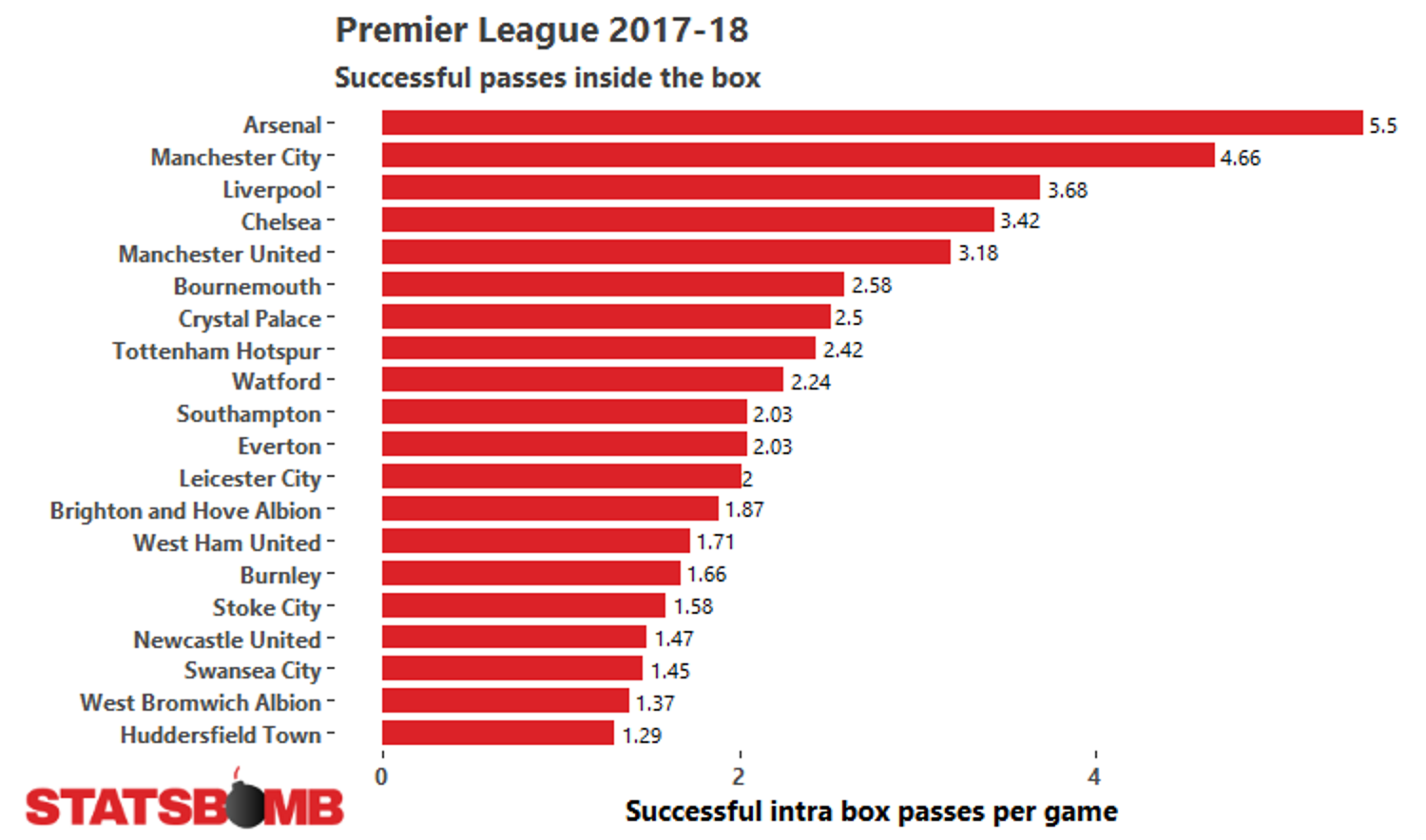

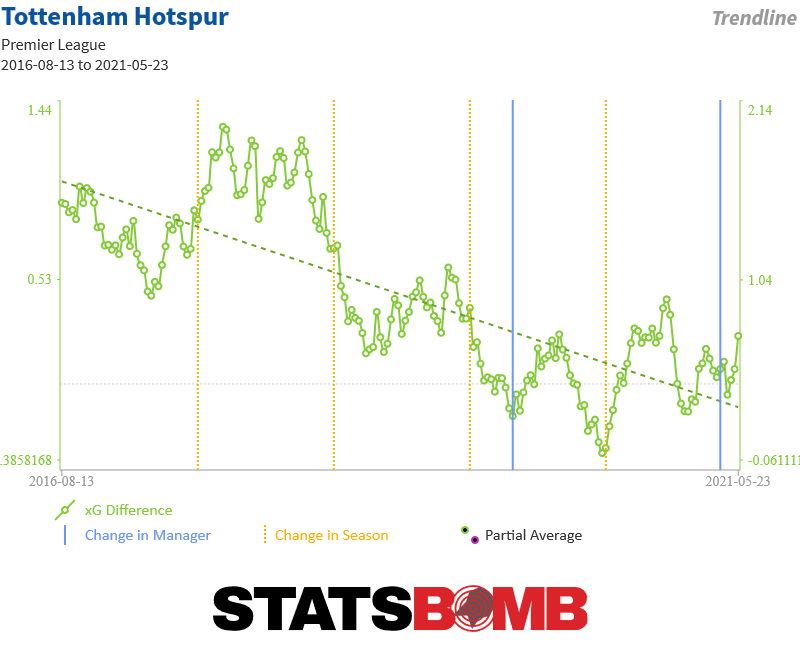

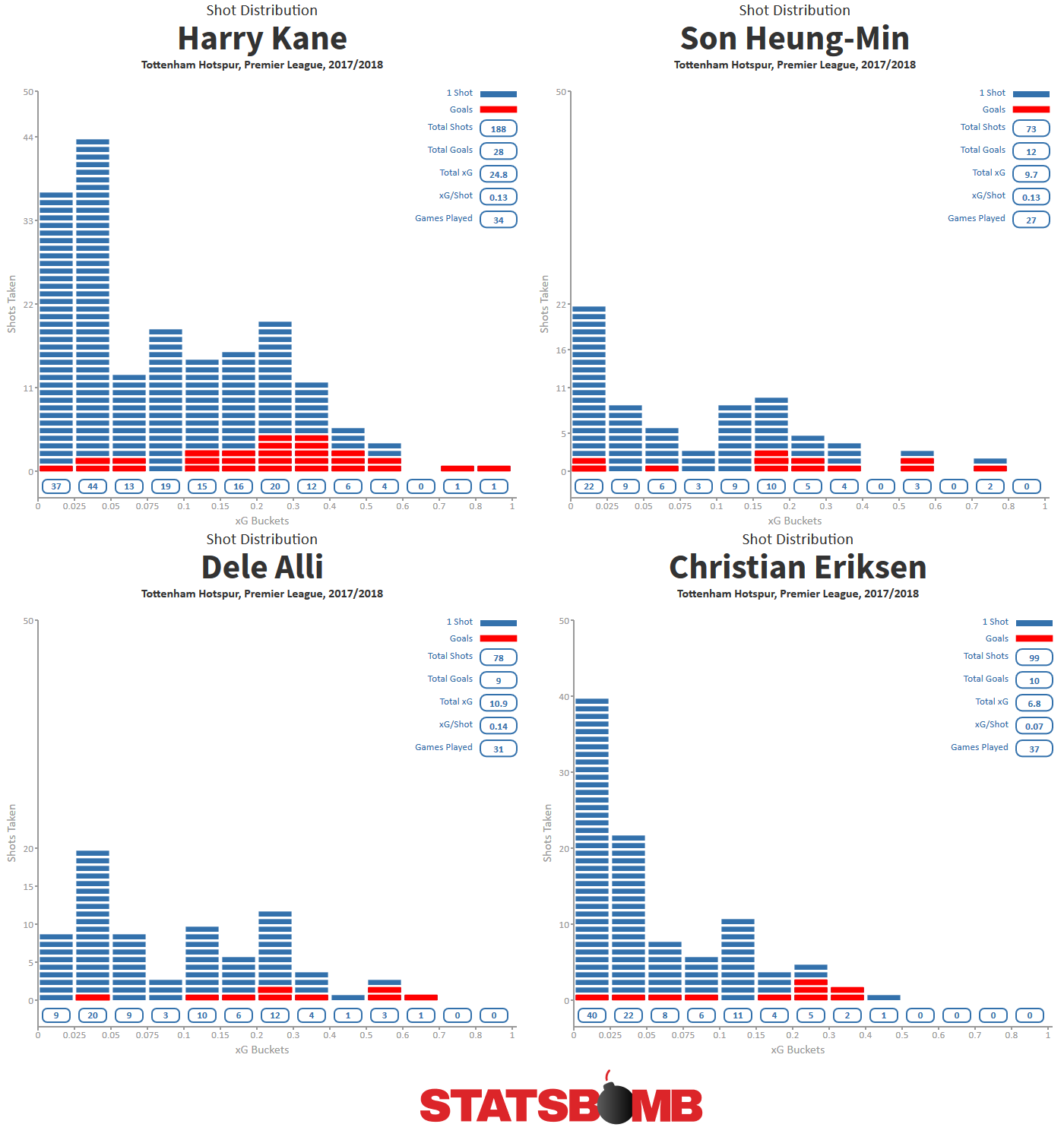

Their strategy is clearly more related to shooting when in advanced positions than looking to carve out a better chance and that chimes with what can occasionally appear like a battering ram approach, especially against teams defending deep. If there's any slight concern regarding last season, it's the way it petered out. Alongside Kane's return, the team did not perform particularly well in the last few weeks of the season:

Their strategy is clearly more related to shooting when in advanced positions than looking to carve out a better chance and that chimes with what can occasionally appear like a battering ram approach, especially against teams defending deep. If there's any slight concern regarding last season, it's the way it petered out. Alongside Kane's return, the team did not perform particularly well in the last few weeks of the season:

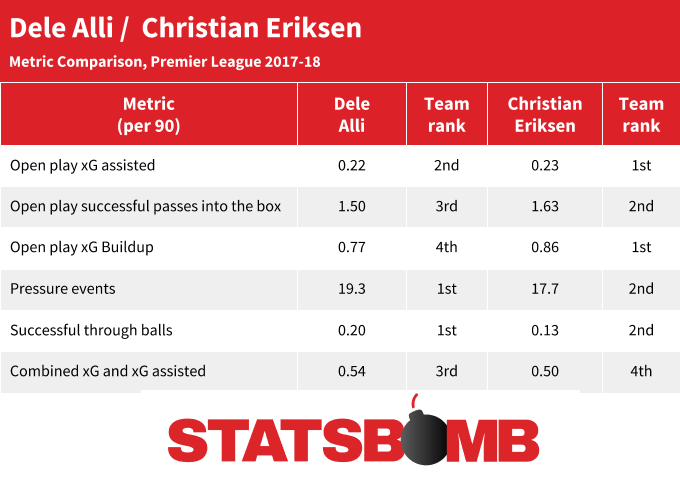

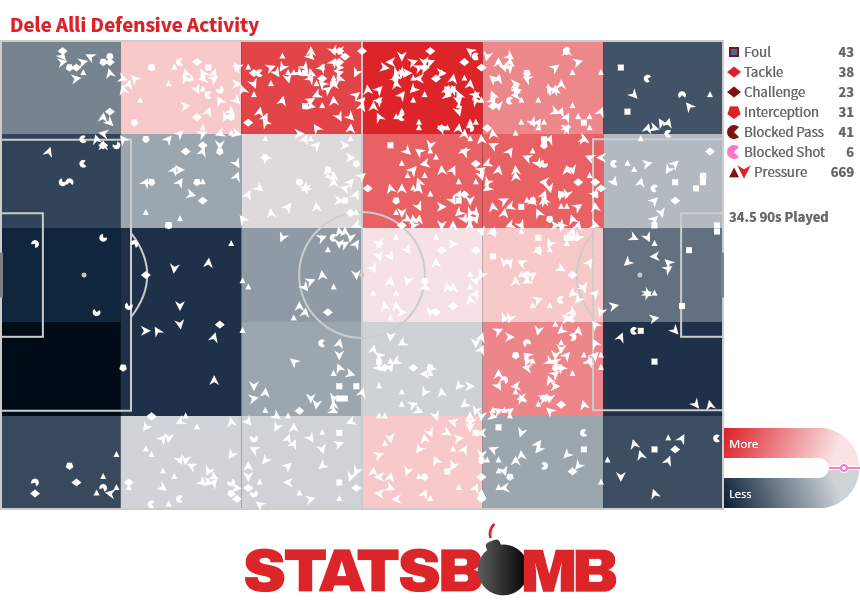

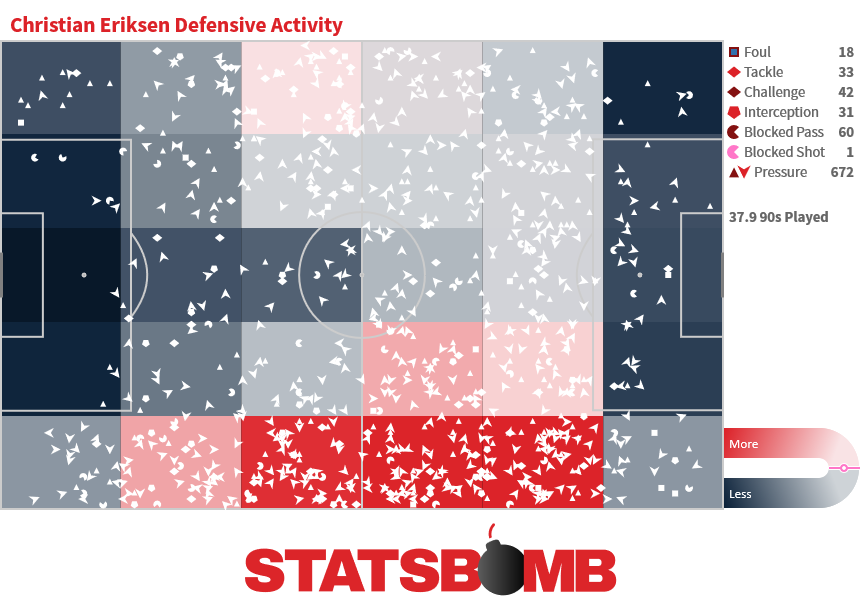

Outside of the metrics shown here Eriksen and Alli are obviously very different players (Eriksen makes a ton more passes, and though they shoot similar volumes they’re from very different parts of the pitch) but 2017-18 saw Tottenham’s upfield creativity as far more of a twin effort. That #1 and #2 rank for pressing events from your team’s chief creators is quite something too:

Outside of the metrics shown here Eriksen and Alli are obviously very different players (Eriksen makes a ton more passes, and though they shoot similar volumes they’re from very different parts of the pitch) but 2017-18 saw Tottenham’s upfield creativity as far more of a twin effort. That #1 and #2 rank for pressing events from your team’s chief creators is quite something too:

It's often thought that Erik Lamela is Pochettino's football vision realised in human form, but Alli and Eriksen perhaps represent it even more emphatically. Formation/First team choices Tottenham were one of many teams to experiment with three at the back last season, and questions around whether it was a favoured formation lasted well beyond a December switch back to Pochettino’s more familiar 4-2-3-1, with Toby Alderweireld out with a long term injury. By the time he returned to the first team squad, Davinson Sanchez and Jan Vertonghen appeared to be the clear preferred pairing. Cloudiness over Alderweireld’s future alongside Sanchez’s impressive form in his debut season at the club meant the Belgian’s inclusion in the first team was no longer a formality. For now Alderweireld remains, and that leaves a strong choice at centre back. It's long enough now since the three centre back experiment was commonplace to presume that while it remains part of Spurs' armoury, it will not be the default. The full back situation may be in a slightly better slot just by chance. Danny Rose appears to be fit after missing clumps of time last time round, and even though Ben Davies will always get hammered for the one bad game he has per season, he’s ahead in the pecking order now and reliable. On the other side, Serge Aurier still needs to cut out the exuberance at times while somehow if the World Cup did nothing else it caused Kieran Trippier to now be seen as an elite full back… kinda? Wild stuff. Central midfield is problematic with a blend of Eric Dier’s steady stoicism, and the variously injured trio of Victor Wanyama, Harry Winks and Dembélé. If they’re all fit there’s probably not too much of an issue here, albeit a lack of passing nous, but they haven’t been and a big signing in this slot would be ideal. As it is, there’s more chat about wide forwards, when the attacking midfield band is fairly deep. Eriksen, Alli, Erik Lamela, Heung-Min Son and Lucas Moura are five players for three places with plenty of bench time already for those that miss out. Moussa Sissoko remains an option. And Kane plays up front. Always. In fact so strong is the attacking midfield band, that it’s easy to argue that playing four from those five players is the answer to a non-Kane line-up, as was seen when he missed time late last season. Transfers Last summer was quiet then came to life as the end of the window closed in. The result was as follows:

It's often thought that Erik Lamela is Pochettino's football vision realised in human form, but Alli and Eriksen perhaps represent it even more emphatically. Formation/First team choices Tottenham were one of many teams to experiment with three at the back last season, and questions around whether it was a favoured formation lasted well beyond a December switch back to Pochettino’s more familiar 4-2-3-1, with Toby Alderweireld out with a long term injury. By the time he returned to the first team squad, Davinson Sanchez and Jan Vertonghen appeared to be the clear preferred pairing. Cloudiness over Alderweireld’s future alongside Sanchez’s impressive form in his debut season at the club meant the Belgian’s inclusion in the first team was no longer a formality. For now Alderweireld remains, and that leaves a strong choice at centre back. It's long enough now since the three centre back experiment was commonplace to presume that while it remains part of Spurs' armoury, it will not be the default. The full back situation may be in a slightly better slot just by chance. Danny Rose appears to be fit after missing clumps of time last time round, and even though Ben Davies will always get hammered for the one bad game he has per season, he’s ahead in the pecking order now and reliable. On the other side, Serge Aurier still needs to cut out the exuberance at times while somehow if the World Cup did nothing else it caused Kieran Trippier to now be seen as an elite full back… kinda? Wild stuff. Central midfield is problematic with a blend of Eric Dier’s steady stoicism, and the variously injured trio of Victor Wanyama, Harry Winks and Dembélé. If they’re all fit there’s probably not too much of an issue here, albeit a lack of passing nous, but they haven’t been and a big signing in this slot would be ideal. As it is, there’s more chat about wide forwards, when the attacking midfield band is fairly deep. Eriksen, Alli, Erik Lamela, Heung-Min Son and Lucas Moura are five players for three places with plenty of bench time already for those that miss out. Moussa Sissoko remains an option. And Kane plays up front. Always. In fact so strong is the attacking midfield band, that it’s easy to argue that playing four from those five players is the answer to a non-Kane line-up, as was seen when he missed time late last season. Transfers Last summer was quiet then came to life as the end of the window closed in. The result was as follows:

- Davinson Sanchez, £40m: Looked expensive and risky for a very young centre back, turned out great.

- Fernando Llorente, £12m: Looked expensive and risky for an ancient target man who didn’t fit the system, and turned out, notsogreat.

- Juan Foyth, £10m: a young centre back, who remains young and scarcely seen.

- Serge Aurier: £22m: Kyle Walker needed replacing and Aurier had the pedigree and horrible errors aside, was okay.

It didn’t feel like the most targeted bunch of signings and the varying success of them was probably reflective of that. A team is rarely going to nail all its transfers, but beyond the success of Sanchez, the outcomes felt fairly predictable. Lucas Moura’s January arrival is currently looking like Tottenham’s best signing of 2018 (he stands alone), for he only saw sporadic minutes last season, and we’re long used to Pochettino taking time to trust or reliably deploy new players, particularly in the hard to shift attacking slots. And now? The noises are that purchases will be made--almost certainly as soon as this article is printed--but so far nothing. While the first team is stable, there is never any harm in signing players with a view to them becoming starters rather than just to fill out the squad and that's something that Tottenham haven't always managed to do. It is hard to know exactly how this will all pan out. The homegrown quota is looking lean and Jack Grealish had been thought close to arrival, but a change in ownership at Aston Villa may have shifted circumstances there. It also feels unlikely that a high cost purchase such as Wilfried Zaha or Anthony Martial will fit within the general budget. For once, Tottenham have not banked a big cheque this summer, having long looked likely to perhaps move Alderweireld or Danny Rose, and none of the rest of their first teamers look to be agitating for a move. The distortion of the transfer window shutting in England well ahead of the continent looks to have altered the power dynamic, and a “sell before they buy” philosophy has been impossible to lock down. Eight years may have passed, but the eternal hope remains that a last minute Rafael Van Der Vaart type deal could fall in the club’s lap; regardless it looks certain that they will be in conversation for players until the last moment. Really though, central midfield has been crying out for an off the shelf star for some while now and the club would gain a lot of fan favour if it just went all in there. Projection Tottenham’s metrics have been rock solid for three years, and they have basically the same team as last season predominantly arriving in peak years. Their goalkeeper just won the World Cup and they are about to land in a new stadium. They have one of their most popular managers and are once more in the Champions League. The narrative about silverware will never disappear until it’s vanquished, but the knock on effect of Walker’s move to Man City and a title does not appear to have triggered unrest. The gap between the top six and the rest of the league remains huge and Tottenham are arguably structurally better off than a rebuilding Chelsea or Arsenal and the vibes out of the red side of Manchester are becoming ever weirder. It’s feasible that any or all of those three teams could hit the positive end of their variance or upspin from their already high talent level and contend with Liverpool, Tottenham and Manchester City, who look more stable with a view towards a top six bid. Each will have to though. City are a complete lock for probably a top two slot at least, Liverpool fundamentally look like they will be better and have to be in the mix for the highest places, and Spurs just keep doing Spurs, which is usually enough. Third, second, third doesn’t feel like it’s going to be added to with a first. Despite this, another second or third coupled with the stability that is brought from consistency would still mean Tottenham have landed in their new stadium with the team quality that the move was designed to help generate. They’re at the end of that long journey now, but what’s to say there aren’t more good times ahead?

Thank you for reading. More information about StatsBomb, and the rest of our season previews can be found here. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

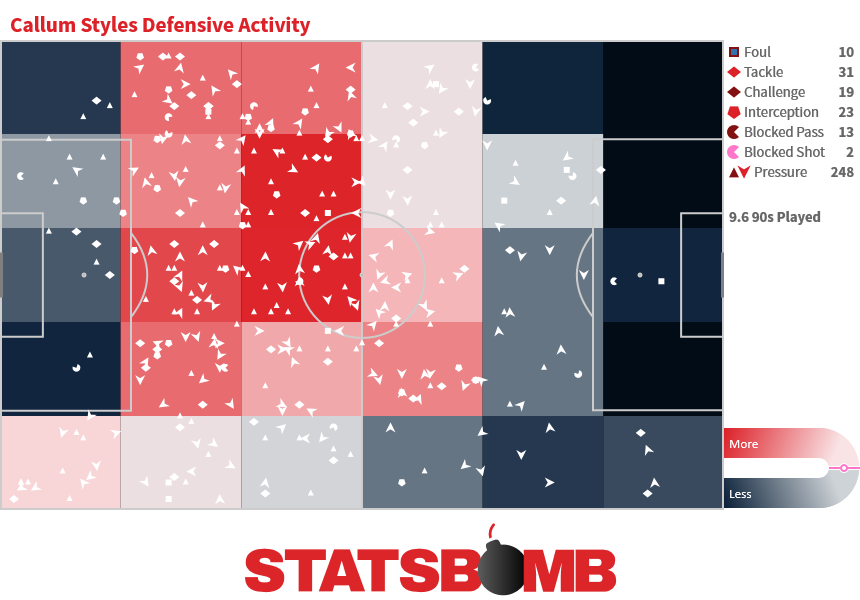

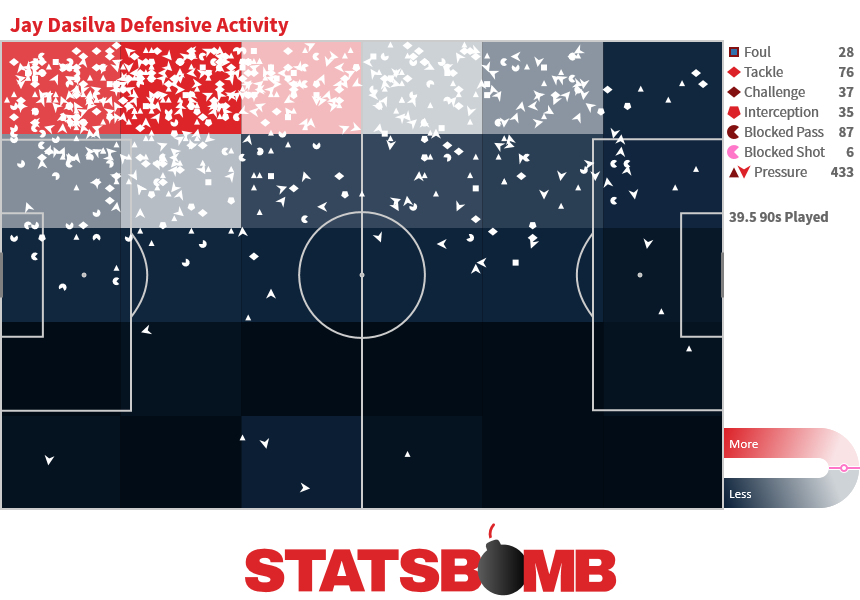

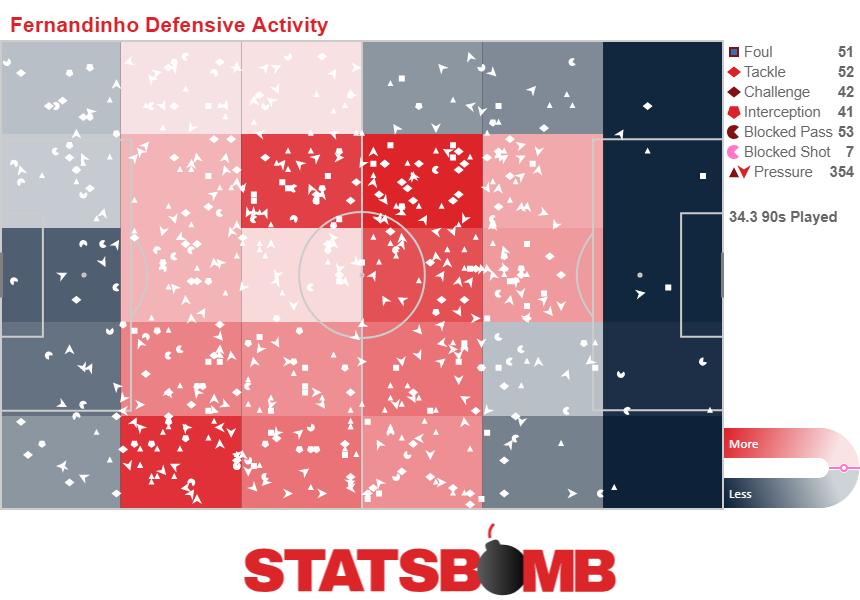

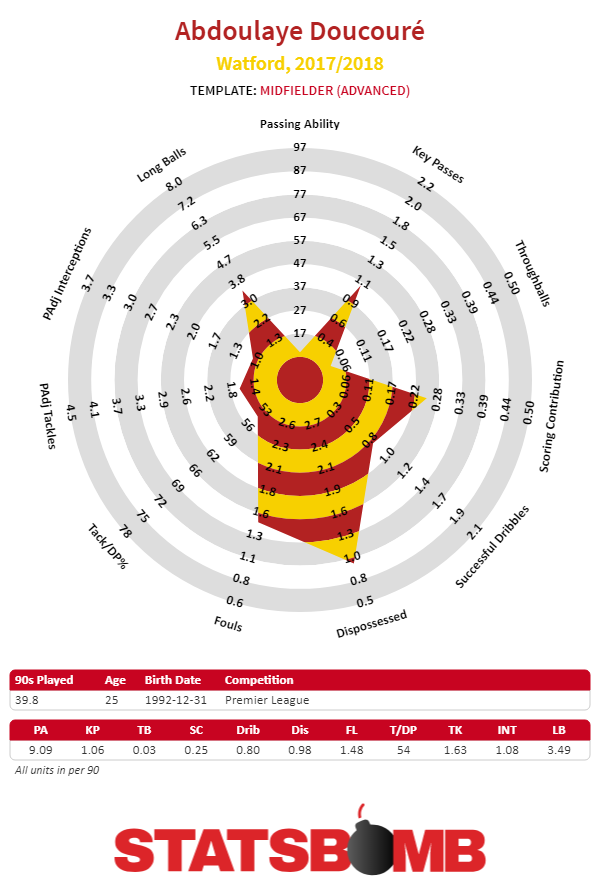

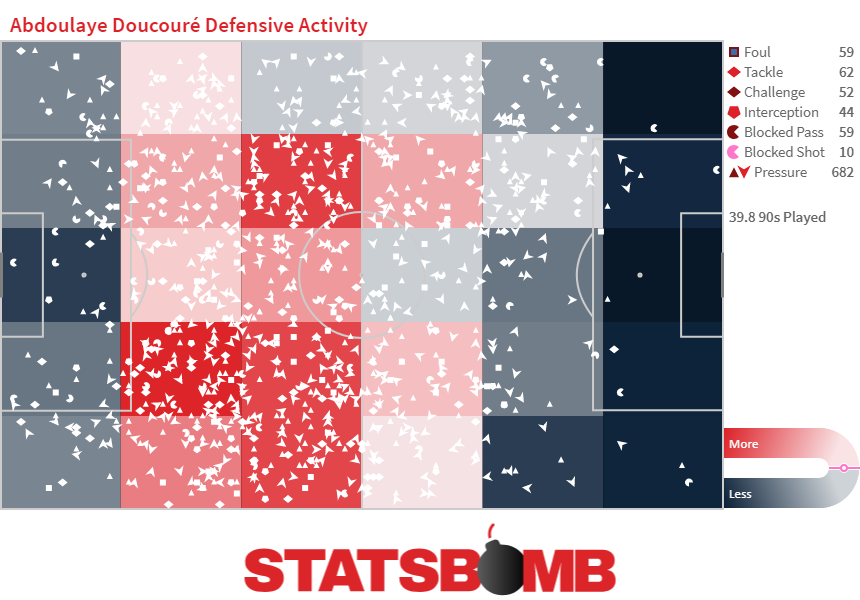

Doucoure's game ability to use his mobility to pressure opponents is something that would likely translate to a bigger club.

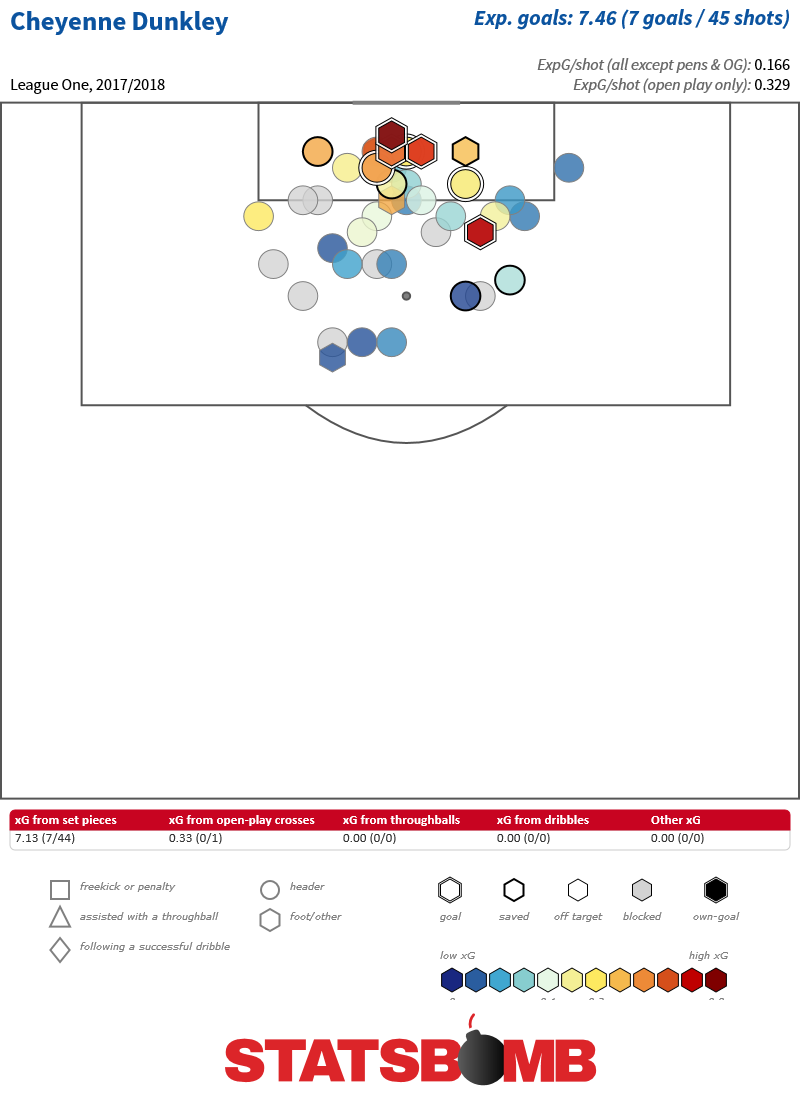

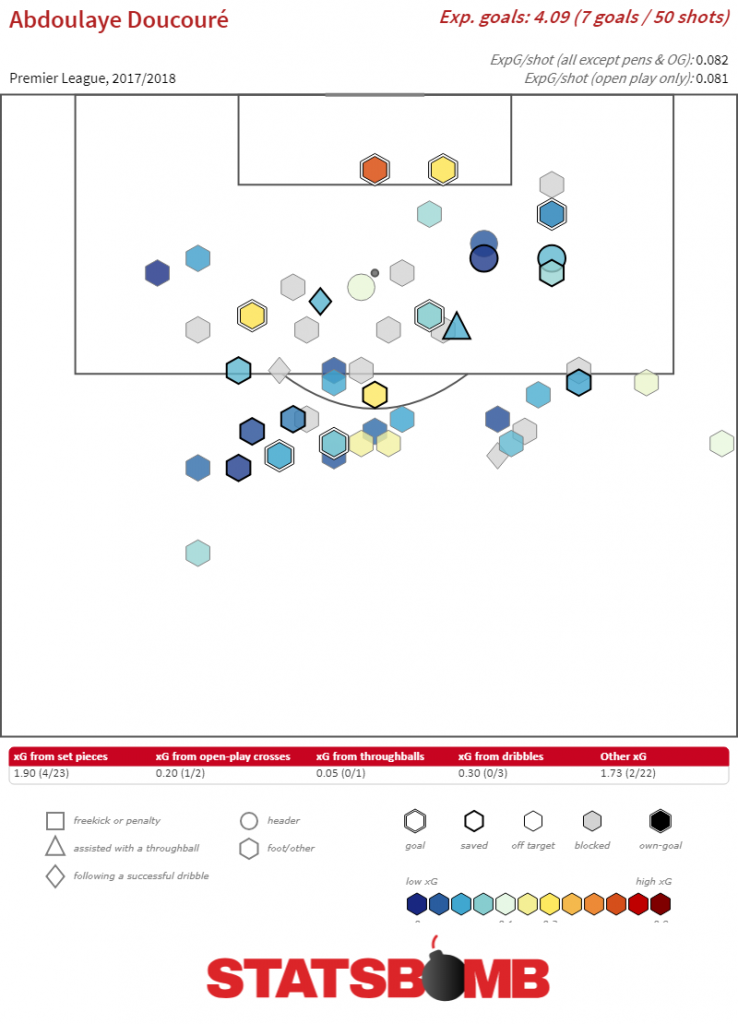

Doucoure's game ability to use his mobility to pressure opponents is something that would likely translate to a bigger club.  The other eye-catching feature of Doucoure's season for Watford was that he contributed 10 non penalty goals this season, which is not an insignificant figure for a player that nominally plays as a defensive midfielder. Being someone who can play that position and can contribute goals is valuable. In particular, Doucoure does a good job of making himself another player that has to be accounted for inside the penalty area with his runs into the box. He also generated the type of shots that one would expect from a deep midfielder, running into the open space near the penalty area that’s been vacated by the defense.

The other eye-catching feature of Doucoure's season for Watford was that he contributed 10 non penalty goals this season, which is not an insignificant figure for a player that nominally plays as a defensive midfielder. Being someone who can play that position and can contribute goals is valuable. In particular, Doucoure does a good job of making himself another player that has to be accounted for inside the penalty area with his runs into the box. He also generated the type of shots that one would expect from a deep midfielder, running into the open space near the penalty area that’s been vacated by the defense.

That's the good you get with Doucoure, and it's not as if these aren't valuable traits to have. Having a midfielder with an ability to make runs into the penalty box along with being an active member defensively is something noteworthy. But, the deficiencies of Doucoure's game make his strengths not pop as much as perhaps they could. While Doucoure does have the ability to make incisive runs into the penalty box, his positioning further back during buildup play can leave a lot to be desired. In particular, one thing that was odd when watching Doucoure is that he loves to run back to receive the ball. This in of itself isn't a major problem, and it does partly explain why his xG buildup rate of 0.502 ranks among the 10 best rates for players not in a top six side. But, his penchant for always moving backwards and at times even being parallel to the teammate in possession of the ball does himself a disservice. Just moving five to 10 yards forward to make it easier on himself and his teammates to receive the ball with space to attack the defense would improve his buildup play. Even though Doucoure may not be an amazing dribbler, he certainly can be enough of a threat and provoke the defense to close him down, which could lead to a disorganized defense. Here's an example from the very beginning of Watford vs Burnley; the ball is passed back to one of the Watford center backs and they have a three against one advantage. There is a lot of space in front of Doucoure and the potential for a third man run to occur and provoke the defense, but he doesn't move forward and it results in a failed long ball and turnover of possession.

That's the good you get with Doucoure, and it's not as if these aren't valuable traits to have. Having a midfielder with an ability to make runs into the penalty box along with being an active member defensively is something noteworthy. But, the deficiencies of Doucoure's game make his strengths not pop as much as perhaps they could. While Doucoure does have the ability to make incisive runs into the penalty box, his positioning further back during buildup play can leave a lot to be desired. In particular, one thing that was odd when watching Doucoure is that he loves to run back to receive the ball. This in of itself isn't a major problem, and it does partly explain why his xG buildup rate of 0.502 ranks among the 10 best rates for players not in a top six side. But, his penchant for always moving backwards and at times even being parallel to the teammate in possession of the ball does himself a disservice. Just moving five to 10 yards forward to make it easier on himself and his teammates to receive the ball with space to attack the defense would improve his buildup play. Even though Doucoure may not be an amazing dribbler, he certainly can be enough of a threat and provoke the defense to close him down, which could lead to a disorganized defense. Here's an example from the very beginning of Watford vs Burnley; the ball is passed back to one of the Watford center backs and they have a three against one advantage. There is a lot of space in front of Doucoure and the potential for a third man run to occur and provoke the defense, but he doesn't move forward and it results in a failed long ball and turnover of possession.  Perhaps at other clubs he'll be told to be more aggressive with his positioning, and if that's the case, then this is becomes a moot point, but he could be better in this department. What is undeniably true is that Doucoure profiles as both a conservative passer and one that isn't good when trying to make high level passes, which should be enough of a red flag to warrant skepticism of his worth as a player. He'll show glimpses here and there of decent passing and getting the ball forward to his teammate in stride, but it's just glimpses. At his worst, watching Doucoure pass can be like watching a golfer hacking helplessly from a bunker. It just doesn't look smooth seeing him trying to get the ball out of his feet.

Perhaps at other clubs he'll be told to be more aggressive with his positioning, and if that's the case, then this is becomes a moot point, but he could be better in this department. What is undeniably true is that Doucoure profiles as both a conservative passer and one that isn't good when trying to make high level passes, which should be enough of a red flag to warrant skepticism of his worth as a player. He'll show glimpses here and there of decent passing and getting the ball forward to his teammate in stride, but it's just glimpses. At his worst, watching Doucoure pass can be like watching a golfer hacking helplessly from a bunker. It just doesn't look smooth seeing him trying to get the ball out of his feet.  Given the flaws to his game, it's fair to wonder how much could Doucoure help bigger sides if given a prominent role on the first team. With his suspect passing and positional awareness, he doesn’t really fit for where football is at the highest level in both the PL and in European football. One player that I thought of that could serve as a comparison would be Paulinho, someone who performed fairly well at Barcelona last year. With the limitations that Paulinho had in possession, he was used best as someone who could wreak havoc and provide stability with his movements into the penalty box. That's how he ended up producing ridiculously

Given the flaws to his game, it's fair to wonder how much could Doucoure help bigger sides if given a prominent role on the first team. With his suspect passing and positional awareness, he doesn’t really fit for where football is at the highest level in both the PL and in European football. One player that I thought of that could serve as a comparison would be Paulinho, someone who performed fairly well at Barcelona last year. With the limitations that Paulinho had in possession, he was used best as someone who could wreak havoc and provide stability with his movements into the penalty box. That's how he ended up producing ridiculously