One of the things I’ve been mulling over recently is how team stats are both a reflection of the players and of the man in charge. Even in this era of unprecedented player power, a team's manager still picks the team sheet, and players generally need to do what the manager wants in order to stay in the lineup.

But when it comes to managerial evaluation, more than anywhere else in football, it is incredibly hard to divorce personality from performance. Managers who are grumpy gits with no sense of humor get away with far less than the slick salesmen whose performance is never more than average wherever they land. Strong tactical, technical managers who aren't that great with the press often seem less fondly remembered than their less successful, but smoother talking counterparts.

How can analytics help with regard to manager evaluation, and better separate the good managers from the bad?

It’s All About the Money Money Money

One popular use of analytics in managerial evaluation is comparing team spend vs. manager performance. The theory here is that the league table should approximately represent the value of the various teams, and managers that over or underperform how much money has been spent on their squad are interesting. The issue I have with this type of evaluation is that it is a) slow, and b) muddy. Is one season enough to tell if a manager is doing a decent job compared to wage spend? What if they take over a squad that is horribly meshed to their preferred style and have to spend an entire year transitioning?

You can look back at past performance and create a delta variable versus how a manager was predicted to fare, but to me this analytical method just isn’t that useful.

Points Per Game

This is the other evaluation tool I see commonly used, especially when comparing across leagues. It’s useful in that managers move around during the season, and this type of evaluation removes the direct team association, so you can find out things like Dougie Freeman was really good at managing 3 different teams last year, even if the one he ended up at did not get into the playoffs.

The problem with this is that it’s basically a floating, managerial league table. I would prefer something a bit more divorced from direct team performance, since as noted above, there are a lot of muddy factors that go into that.

Even if you’ll never be able to remove manager performance from the teams they managed, maybe we can come up with something more descriptive that allows us to look at performance overall, crossed with performance in different areas of the game, to help us better highlight strengths and weaknesses.

Is the Manager At Least Better Than Average?

In this methodology, we evaluate managers much in the same way we evaluate players – by comparing them to their peers. But instead of rate and counting stats like we use with players, we can compare team performance in some key areas against long-term league averages to find out if a manager is performing better or worse than the other guys around him. Today I want to quickly investigate three key areas.

1) Shot Dominance

This is a metric we use to distill the basic battle of football – is a team generally taking more shots than their opponent? If they are, they will be posting a number over 1, and if they are dominated in this area, the number will be less than 1. Stylistically, teams that are posting numbers quite a bit over 1 are very good at doing the basic, yet extraordinarily important task of shooting more often than their opponents.

2) Shots on Target Conceded

The second metric for evaluation is to look at how well a manager coaches the defense, and we do this by looking at how frequently the team concedes shots on target versus the league average. Conceding more shots on target than expected likely means your defense has some organizational issues (and or is bad at limiting errors). Conceding fewer shots on target than expected is usually the sign of a well-coached, tightly-organized defense. Basically, this adds a quality control layer to shot dominance.

3) Shots on Target

The final metric I want to look at today is Shots on Target for the offensive end. Creating more shots on target than expected is a combination of talent and efficient offensive systems. Creating fewer shots on target than expectation is a sign that players are likely being wasteful with the ball, shooting from bad positions, or creating offense in a way that is less efficient than other teams in the league. This is a second quality control layer added to shot dominance, both of which can be highly influential in determining outcomes.

Any one of these metrics is interesting by themselves, but when combined they should provide a reasonable evaluation metric for the type of system a manager has instituted (ShotDom), how well they are coaching the defense compared to the rest of their league, as well as how efficient their offense is at creating +EV shots.

If this way of evaluating managers is decent, we should also see noted good managers at the top of the metrics, and managers who are not very good filter to the bottom. If not, all we’ll end with is a bunch of noise.

At the end of the day, numbers are boring to most people, so I’ve tried to be helpful and color code performances in each category that stand out compared to league average. Green in all three metrics is very good. Green in two out of the three categories is also very good, especially if that third category is just neutral.

Red in just one category is not great and a sign of things to be improved (or possibly systemic tradeoffs), while red in multiple categories is objectively bad. It’s a fairly clear sign that the manager needs to coach the team to do things better in multiple areas of the pitch.

A quick caveat: even the best managers are limited by the talent at hand, and good or bad talent will heavily skew some of these metrics. Managers manage groups of players, and their performance and the performance of the team is the result of what those players do – it’s impossible to completely strip out players from managerial evaluations, and teams with the most talent will also tend to be near the top of these tables.

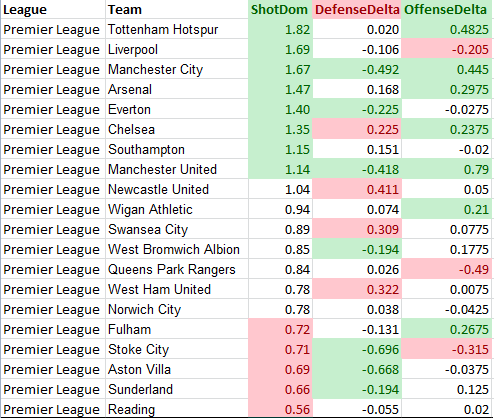

EPL

There were only two teams in England with green across the board, and both of them resided in Manchester. Spurs, Arsenal, Everton, and Chelsea show up with double greens, though it is worth noting that both Arsenal and Chelsea were bad at limiting shots on target versus expectation. This is either a sign that they need better defensive personnel starting most of their matches (Arsenal still commit a ridiculous amount of defensive errors each season), or that the defense could use better coaching. At the other end, Stoke were tremendous on the defensive side of the ball, but stylistically poor and offensively stunted. Reading were neutral at the offensive and defensive stats, but they were dominated time and again and the onslaught forced them down. QPR are interesting, because they weren’t terrible in style or in allowing too many shots on target versus expectation, but a second year in a row of absolutely terrible offensive performance saw them relegated as well. That Shots on Target number was actually an improvement on how bad it was over the Christmas holiday – maybe Remy just arrived too late.

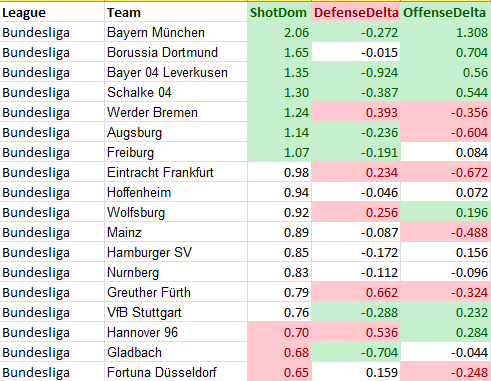

Bundesliga

There were three full green clubs in the Bundesliga last season, with Munich obviously leading the way. Dortmund were defensively neutral in SOTCON, but they gave up under 10 shots a game, so there’s no doubt Klopp is amazing as well. Unheralded Freiburg were double green + neutral on offense, while Stuttgart were double green + neutral as well, but their shot dominance number is right at the cusp of being red. They need to play a more dynamic, positive style to get a better performance overall in the league.

Werder Bremen can officially be dubbed a hot mess. They are doing the systemic thing surprisingly well, but there are flaws in execution hidden at both the offensive and defensive ends.

At the other end, Greuther and Fortuna are nearly both triple red, and it’s no surprise they were relegated. What does come as a surprise is how well Frankfurt and Hannover fared, when these metrics would figure they should be much further down the table. I would expect significant regression this season if those two teams perform the same across the board.

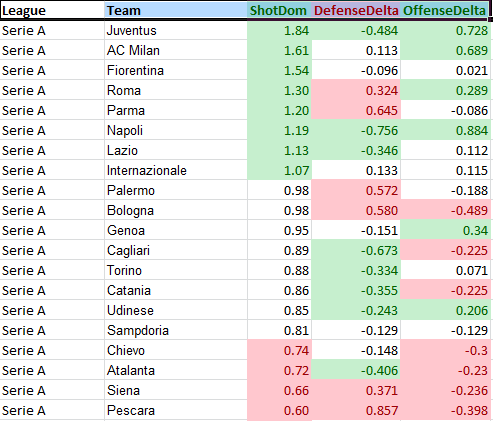

Serie A

Juve and Napoli are both greened up. Considering Mazzari jumped from Napoli to inter this summer, that should mean good things for the Nerrazzuri, whose Shot Dom was basically neutral and whose defense teetered on bad last year. Even if their talent were the same, I’d expect Inter to be a lot better this coming year due strictly to managerial benefits.

Milan, Roma, Lazio, and Udinese are double green in Serie A, but Roma has the expected defensive problem that comes with Zeman, while Udinese lost the shots battle pretty regularly.

At the other end, Siena and Pescara are both red washouts and were unsurprisingly relegated. The other relegated team was Palermo, who actually did okay in shots dominance, but were awful in defense, and anemic in offense (their offensive number is right on the edge of the red cut off). Atalanta, Chievo, and Bologna sit deep in the double red zone for next season, and need to make significant changes to avoid another relegation fight.

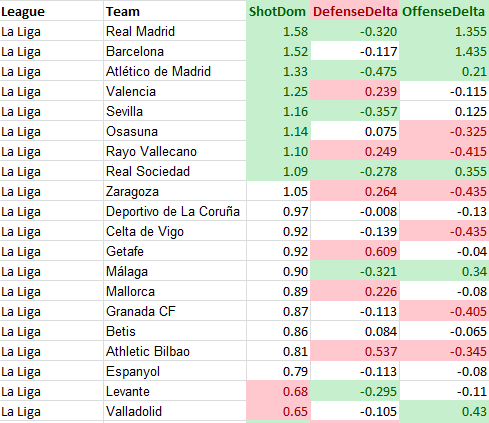

La Liga

Finally we come to Spain. Both Madrid teams are fully green, Barcelona is nearly so, and scrappy Champions League qualifiers Real Sociedad join them. Except Sociedad’s manager never quite got along with the board at Sociedad, and jumped ship to Rennes this offseason. I have no idea how they will perform this year, as their new manager is a former youth and assistant manager who was promoted from within the club. That should make for a fun analytical experiment though.

Sitting in positive double green territory were Sevilla and Malaga, the former of which switched managers during the season, and the latter of which lost Pellegrini to Manchester City this year. Hrm.

Much like Werder Bremen in Germany, Rayo are also a hot mess.

La Liga didn’t have any red washouts, but Bilbao were close, while Zaragoza had a positive style, but were below league average on both the offensive and defensive metrics. Bilbao’s goal differential was actually fourth worst in the league, but they managed to finish a comfortable 12th despite that. Spain’s other two relegated teams were Deportivo La Coruna (a rare all white relegation), and Mallorca (bad defensively, negative in offense as well, but fairly neutral in the shots battle.

Conclusion

Obviously people will make their own judgments, but I find this method of evaluating manager performance far more interesting and descriptive than either performance vs wage spend or the basic points per game evaluation. To me it gives you a much clearer idea of managerial strengths at weaknesses (especially when measured across multiple seasons), as well as some suggestions about style of play folded in.

Feel free to let me know what you think on Twitter or in the comments though. This is just a first crack at a different way of looking at whether your manager is any good or not, and who you should probably be buying if you have a vacancy to fill.

--TK