As far as sample sizes go, two games is minuscule. There is nothing to be found in two games worth of data that a third can’t immediately nullify. The challenge of international soccer is that while two games don’t tell us much, a full third of the 2019 World Cup field will be back on their couches after game number three. So, let’s stretch those numbers to the breaking point and see if they can tell us anything useful.

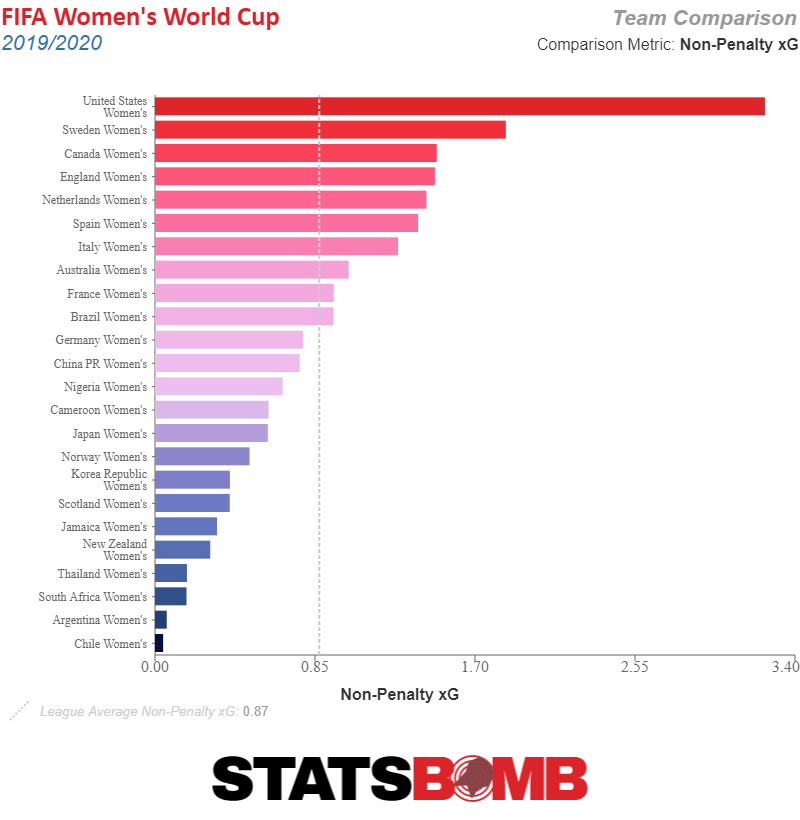

Here are all 24 teams ranked by their expected goals scored per match.

One thing this list makes crystal clear is that with only two games played, the most determinative factor is the level of opponent faced. It’s not surprising for example that the United States tops the list, but Sweden at the second spot, that’s explained more by having the good fortune of a group with Chile and Thailand in it, than any distinguishing factor the Swedes might bring to the table.

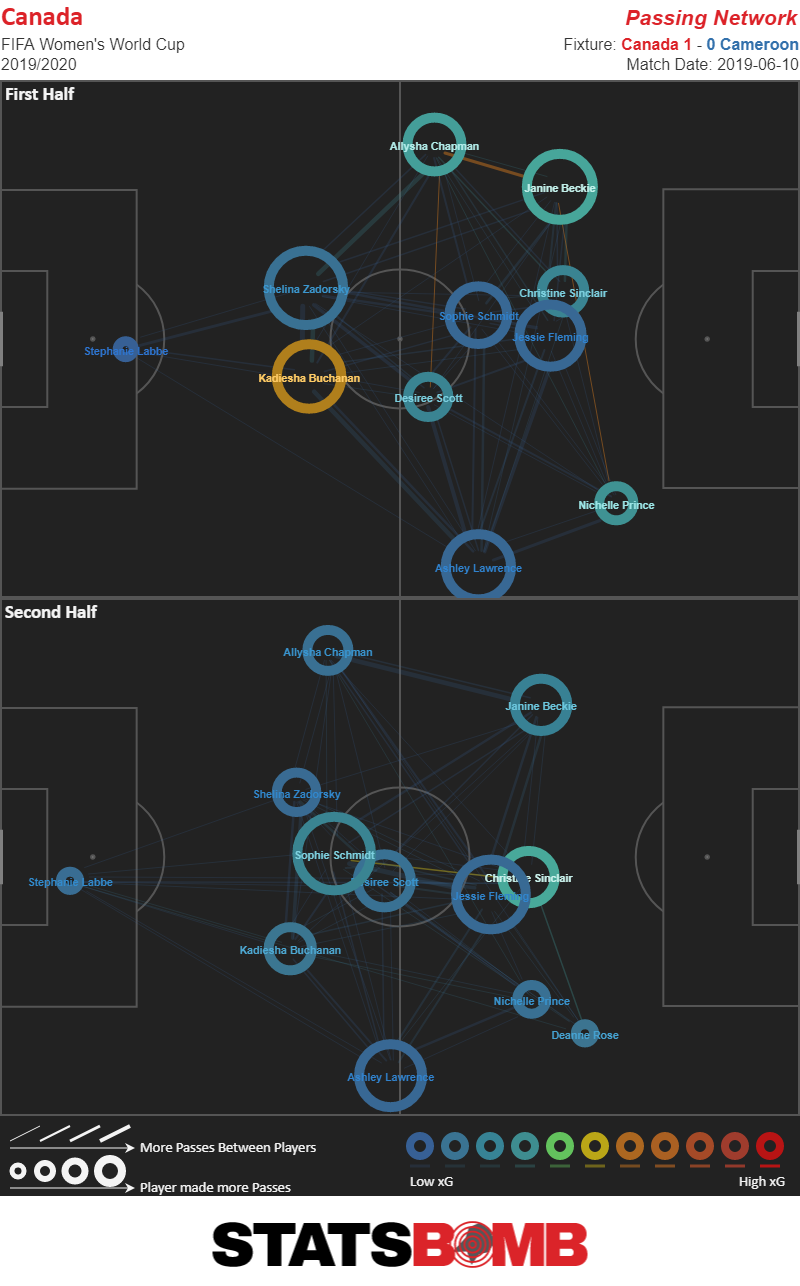

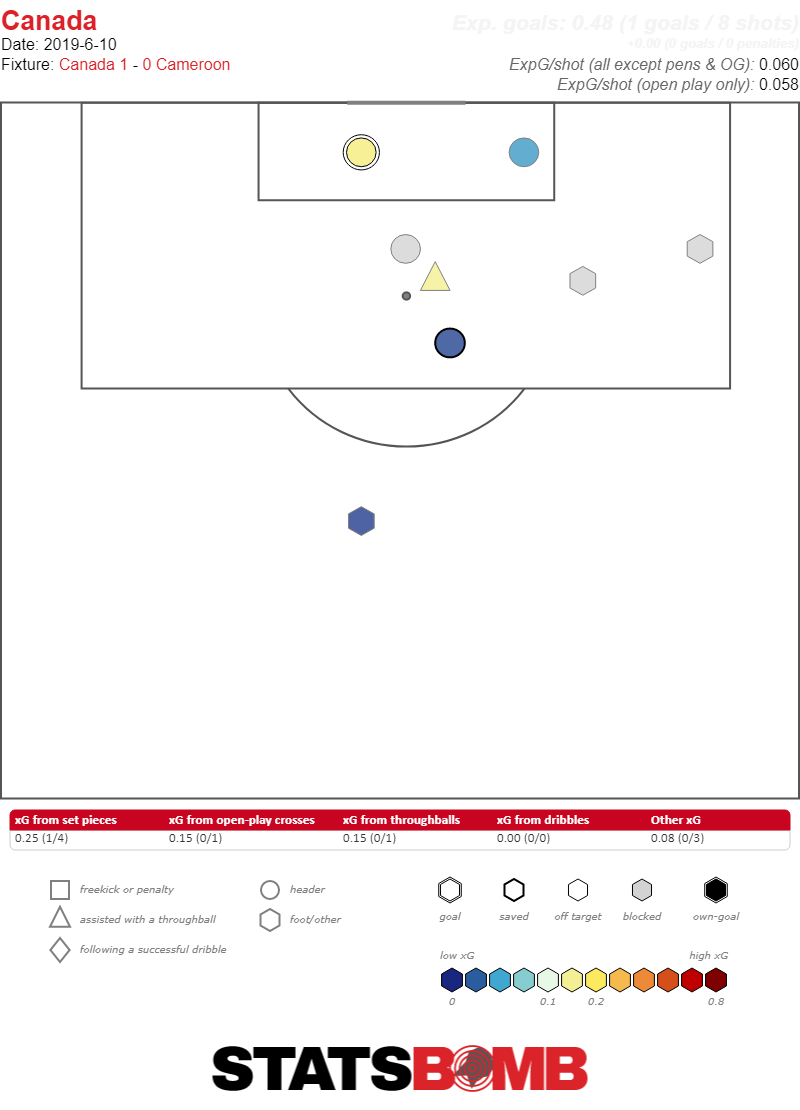

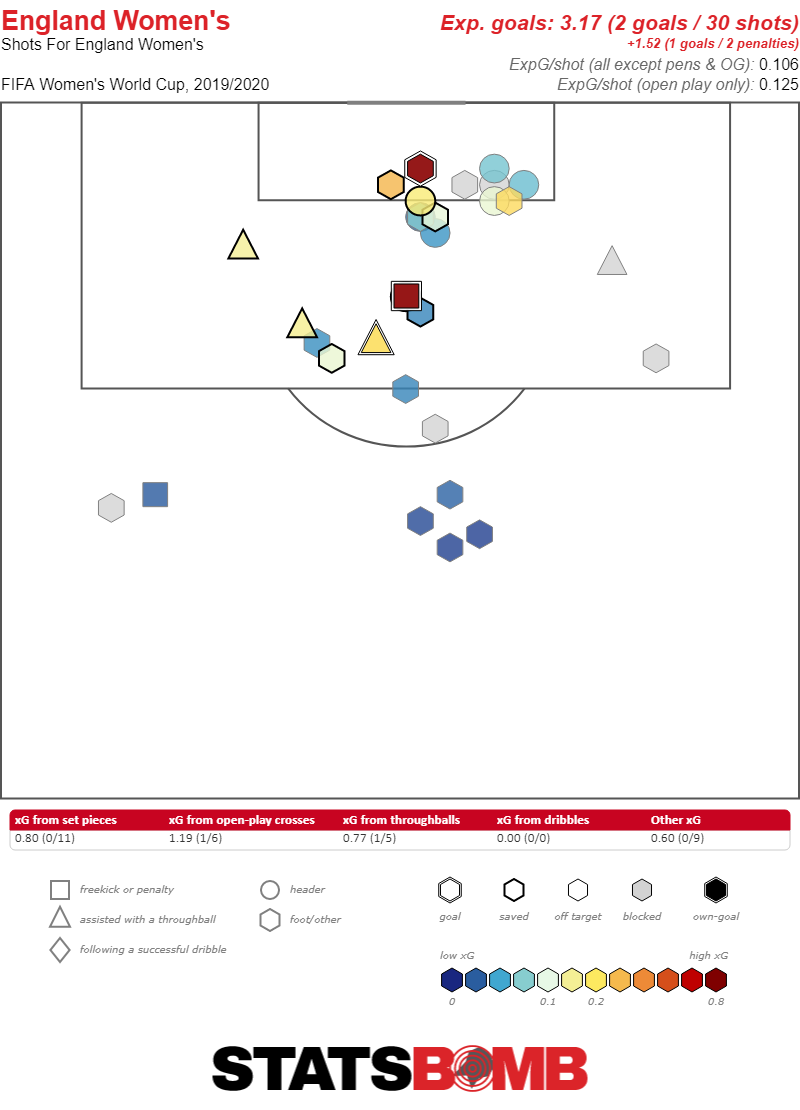

Similarly, Canada and the Netherlands in third and fifth respectively have had Cameroon and New Zealand to hammer away at. And while each of those less heralded sides have had their moments, those matches have largely consisted of the favorite throwing punches and the underdog flirting with being able to absorb them before ultimately succumbing. The same is true of England, sitting in pretty in fourth place on this list.

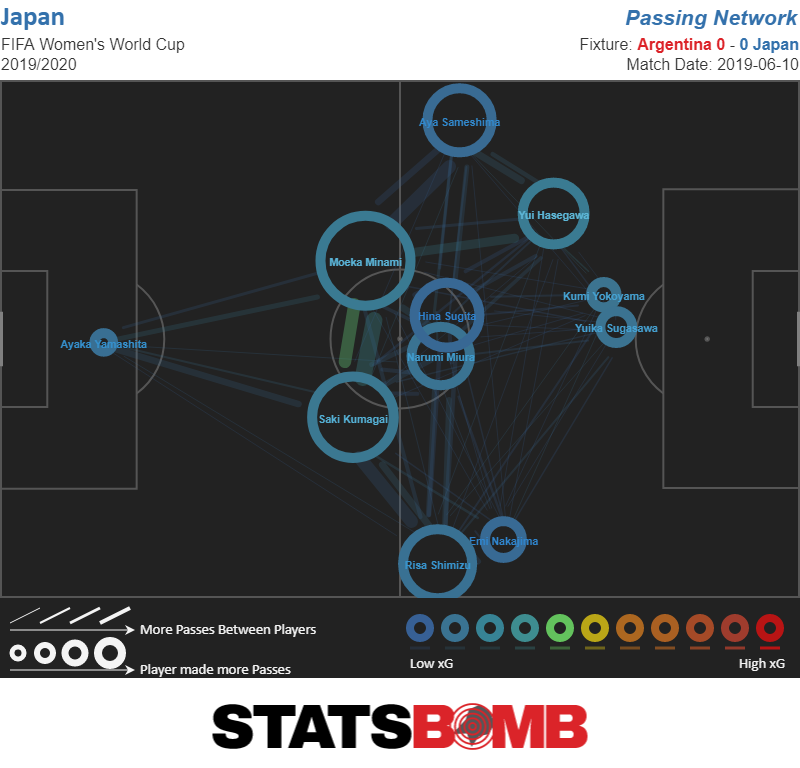

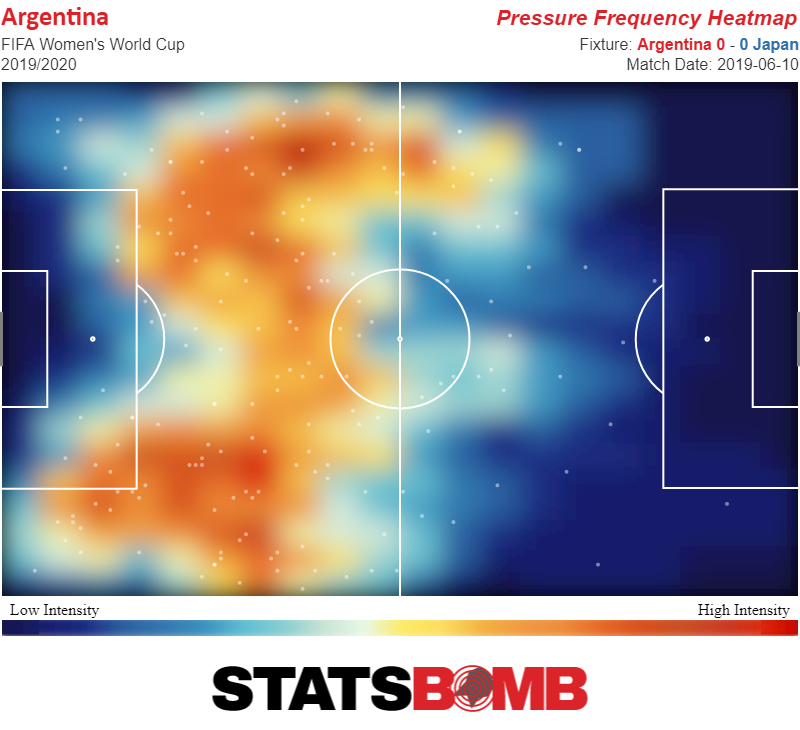

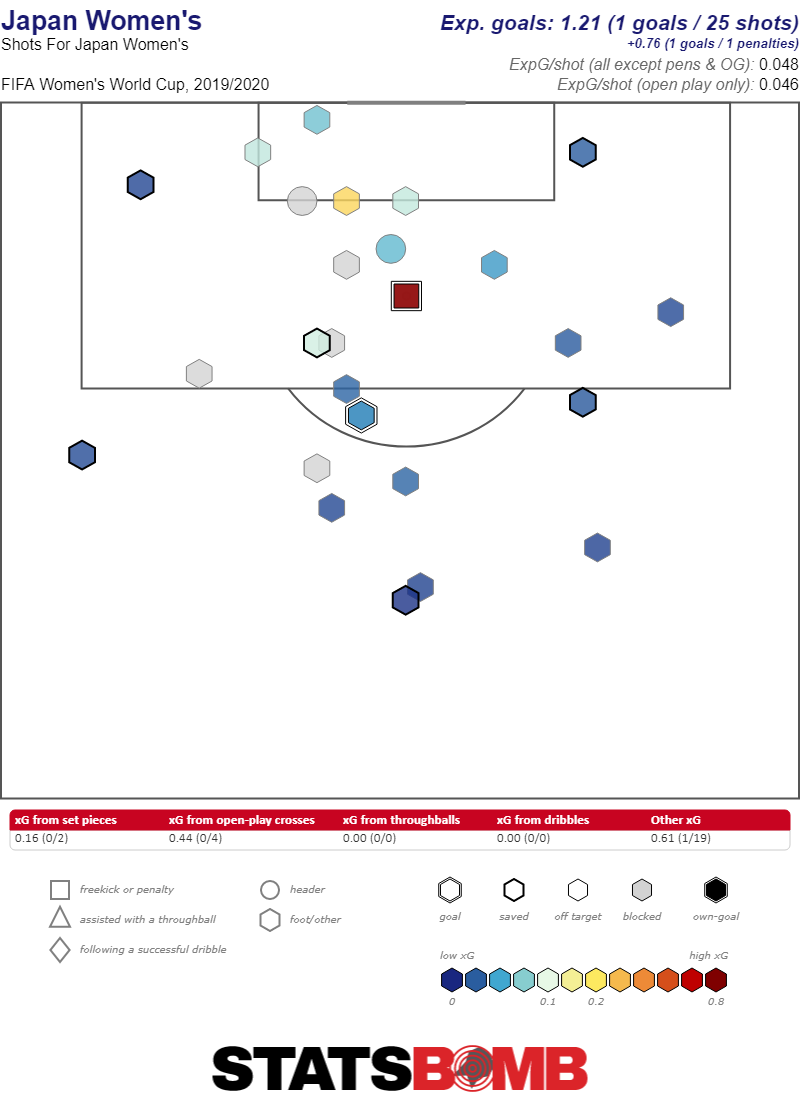

Which brings us to Japan. Despite, like England, having a relatively easy opening couple of matches against Scotland and Argentina, they are nowhere to be seen at the top of this list. They’re actually below average. Only nine teams have less xG per match than Japan’s 0.60. Given who they’ve played, that’s a really bad sign.

A major part of the problem is that they can’t generate good shots. They’ve taken 12.50 shots per match. That’s a more respectable ninth in the tournament. But they just can’t create good chances.

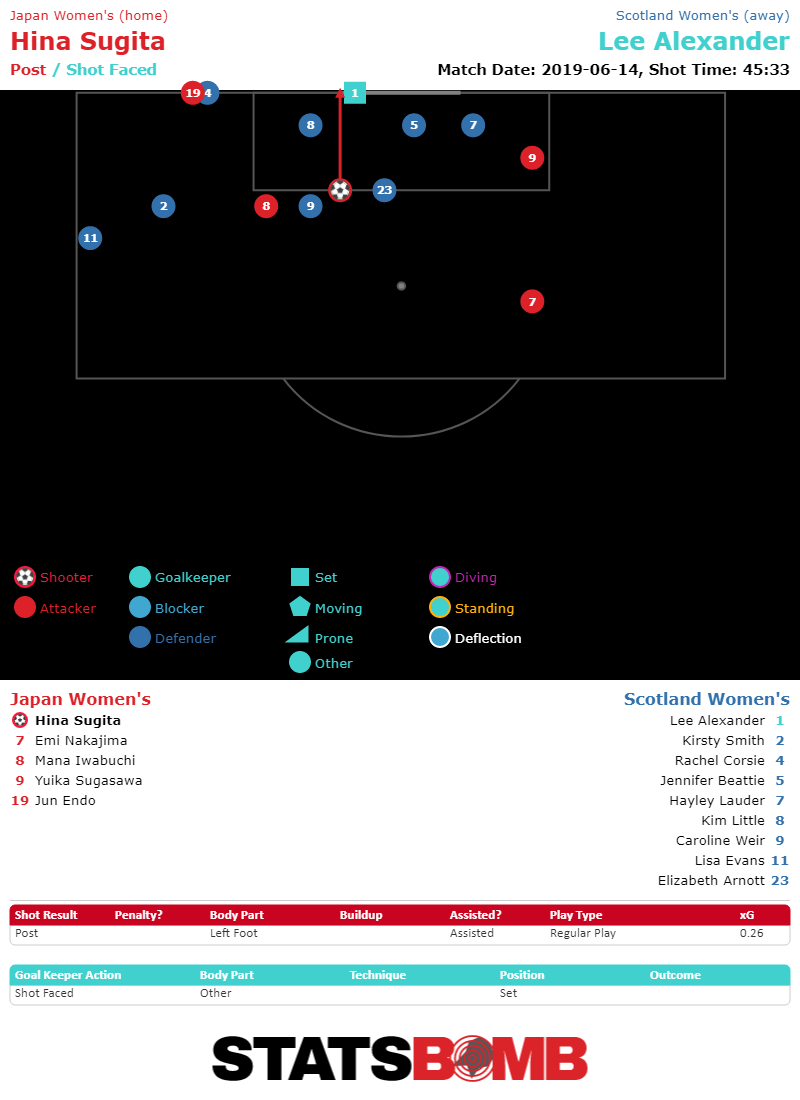

Mana Iwabuchi scored a banger from outside the box but other than one (soft) penalty, only Hina Sugita’s clang off the post in first half stoppage time against Scotland really moved the xG needle.

If Japan had put in these attacking performances against strong sides, it wouldn’t merit concern. But they didn’t, they put them in against two of the weaker teams in the tournament, the same two teams that England did this to.

Japan’s four points will see them through to the knockouts, but they certainly seem to be limping there. Tournaments are short and all it takes is a game or two to shift things dramatically, but right now 2015’s finalists are heading into the latter stages looking much more like an easy out for a strong side to put out of their misery rather than a contender looking to make a real run at winning the thing.

Australia, on the other hand might be better than their numbers indicate, and their numbers are quite respectable. Down 2-0 to Brazil after an opening match loss to Italy, they were staring down their World Cup mortality before scoring three to complete a stunning comeback victory. Australia’s numbers this tournament are mediocre. They’re eighth in non-penalty xG which is respectable. On the defensive side of the ball, long thought to be their weakness (and where they’ve conceded five goals) they are also eighth.

But, unlike Japan, Australia haven’t had the benefit of playing the cupcakier end of the field. Italy have been the tournaments biggest surprise, following up their surprise opening match win against Australia with a dominating 5-0 performance against Jamaica, one of the tournaments weaker teams. Italy wasn’t tested in that match, but 5-0 is the kind of summary execution of subpar opponent that meets expectations for a top international team. We don’t yet know how good Italy is, but they might be a legitimate unexpected force.

Then there’s Brazil. Brazil aren’t at their best. Marta is coming off injury. Formiga is 41. Their “young” dynamic stars, Debinha and Andressa are 28 and 27. But, they’re still Brazil. They’ve still been above average both in attack and defense. With their own win over Jamaica under their belt they will likely make it to the knockout rounds. Australia’s win against them doesn’t say as much about them as it might once have, but it’s more impressive than some of the wins that the tournament favorites have put up.

And Argentina still have Jamaica left to play in the group. If they put up the same kind of giant numbers against one of the worst teams in the tournament that Italy and Brazil did, Jamaica’s negative eight goal difference is the second worst in the tournament, then their numbers will put them near the top of the pack, despite their shaky start.

The reason these comparisons are useful is that by comparing teams within groups it’s possible to grasp towards some understanding of how the numbers might be misreading their accomplishments. This stands in opposition to groups that have clear divides between the two haves and the two have nots. Group E and Group F have very little for analysts to sink their teeth into. Canada and the Netherlands are obviously better than Cameroon and New Zealand and the United States and Sweden are obviously better than Chile and Thailand.

The order of events has served to further obscure meaningful differences. The top teams have each gotten to beat up on both minnows first. That means that all four teams have already clearly punched their ticket to the knockouts. Their third group stage match, where, for the first time in the tournament, they square off against capable competition is now as much about managing minutes, squad rotation and preparation as it is about getting three points. Happenstance means that we won’t learn much about these four sides until the knockouts start and the margin for error decreases dramatically.

Finding interesting nuggets in the statistics early in a tournament is more of an art than a science. Sometimes the numbers point to something obvious, like Japan not being very good this time around. Sometimes, they point to something contingent, suggesting that given a certain set of assumptions, Italy are good, and Brazil are fine, then the conclusion that Australia is good is justified. And sometimes, like with Canada, the Netherlands, the United States and Sweden, all you an do is shrug and wait for more information.

Header image courtesy of the Press Association