Author: Kevin Lawson

The StatsBomb Superstar Combined Five-a-Side and Basketball Team

What does a football analytics company do on slack on a Thursday afternoon when there are no games to speak of? Why talk about basketball of course. Well, not just basketball. The question that arose was who would you pick to compete in a combined basketball and five-a-side match. That is, first the teams played football, then basketball, then if they split those two matches, they'd have a shootout to as a tiebreaker to determine the overall winner. Ultimately we decided to make draft lists. So, four StatsBomb experts (I use the term extremely loosely here) made their top ten lists of who they'd like to run out on the the court/pitch for such a hypothetical competition, complete with their reasoning. So, down below you'll find the lists of CEO Ted Knutson, StatsBomb South head honcho, Ali Elfakharany, CCO, Shergul Arshad and general man about analysis town, Euan Dewar. You should feel free to find all of them on twitter and tell them why they're wrong. Also feel free to figure out your own teams and tell us why you're right. And now, without further ado, the lists. Ted Knutson

2) Giannis "The Greek Freak" Antetokounmpo I think a lot of people will have Giannis as their number 1, and it just makes sense. He's definitely in the top 5 NBA players in any particular year and he's at least had some exposure to juggling the ball. However, having seen enough clips of him interacting with a soccer ball, I'm fairly comfortable that Embiid is the better number one overall.

Ali Elfakharany Despite the fact that the tiebreak is football-related, my train of thought was to mainly pick basketball players for a couple of reasons:

- Football is more popular globally so it’s easier to find base level football skills

- Basketball is more unique physically and so it’s harder to find basketball physique!

- Big basketball players might make good goalkeepers for the shootout

- Absolute domination matters for mental purposes

- Most StatsBomb folks don’t know basketball as well as I do

Without further ado, my list: 1) Joel Embiid The Process is the perfect fit for this sport. A 7’2 foot center with the best low post moves since Hakeem, who is also a magnificent trash talker that grew up in football-crazy Cameroon? Sign me up. Jojo will dunk all over these tiny footballers, and trash-talk them so badly all their penalties will look like that famous Sergio Ramos penalty that ended up orbiting the moon. And he may foul out the entire team before we even get to the shootout. Joel is also the most entertaining guy in sports, and he’ll make sure we have no problems selling this event out. Just think of all the Spanish/Portugese he’ll learn just to mess with Cristiano and Messi. If you need visual evidence, a quick Youtube search will show his spot-kick prowess, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X27obRcPLFI and him driving poor Andre Drummond crazy with his antics. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=miN7g6iEmeo 2) Giannis Antetokounmpo The reigning NBA MVP and probable best player in the world is another obvious pick. African heritage but born and raised in Europe sounds like a football star (Zidane, Mbappe) and a quick Youtube search shows the Greek Freak has some serious football skills. Giannis will bring his trademark enthusiasm and competitiveness to the team, and will probably spend the entirety of the competition mean mugging all these soft European football players. 3) Romelu Lukaku 6’3 and heavier than Russel Westbrook – will be able to keep up physically in both sports. 4) Luka Doncic Luka’s IQ, footwork, and skill ability translate beautifully between both sports. He will reign threes on the football players all while looking very relatable athletically, and then bust out a couple of penalty saves with training from his countryman Samir Handanović 5) Pau Gasol Friends with a lot of football players 6) Zlatan Ibrahimović 6’5, a kung-fu background, supreme ball skills and the OG football trash talker. 7) Antoine Griezmann Obsessed with the NBA and seems to have a 3 point shot 8) Pique A very tall and skilful football player with connections to other sports 9) Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SPQQRwD3j9A 10) Cristiano Ronaldo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AunImole9HI Euan Dewar My assumption is that a team of all-footballers/all-basketball players would decimate any opposing team that has even one player who is not playing their preferred sport. The basketball players aren't going to suddenly all turn into Ronaldinho, the football players aren't all going to start hitting three-pointers against NBA-level defence (or even in an empty gym). If this didn't have the penalty shootout aspect I would have gone with solely NBA players. My thinking is that it's extremely hard to imagine footballers lucking in to even a few buckets against a team of NBA players, but a team of NBA players maybe nicking a goal in a 5-a-side, I think that's easier to imagine. Think of Lebron James trucking some dude off the ball and then finding Russell Westbrook with a pass who zooms down with it and scores. Not super likely, but you can see it happening right? Only there is a penalty shootout involved here, so I'm punting the basketball side and going with only football players. Penalty-taking is a relatively simplistic skill in raw terms - you have much less to consider than you do in open play. But it is still a skill where you can see differences in execution across various levels of talent. NBA players, while immensely gifted, are still miles off of elite footballers in performing football actions. Therefore I want the best footballers so we can crush them in the football match, knowingly get our arses handed to us in the basketball game, and then breeze through the shootout. The more weak links we have (i.e, NBA players) in that segment the worse off we'd be. 1) Lionel Messi Obvious choice. Ironically, he may actually be a weakness in the shootout given recent penalty history, but I am assuming that wouldn't be a huge problem in this scenario. 2) Jan Oblak To truly tighten the noose, a wall of a goalkeeper is also needed. Instead of picking a goalkeeper with a noted penalty-saving record (alhough I will do later) I'm going with probably just the best shot-stopper around. Trusting too much in penalty-saving sample sizes when selecting for this seems foolhardy. Also maybe he can get a layup, who knows. 3) Virgil van Dijk Has all you need in terms of awareness and physical traits to shore up the defense, all while being lovely in-possession too. 4) Kylian Mbappe Good luck. 5) Arturo Vidal My one fear in the football match is that a given NBA player of the requisite size could just ease smaller footballers off the ball (especially if this is FIFA Street rules). WIth that in mind, a big enforcer is needed. VvD fills a big chunk of this need. Vidal is past his prime but still has plenty of skill and, importantly, is a combative bugger with the build to back it up. 6) Josip Iličić Why not make the whole plane out of Messis? 7) Idrissa Gueye Could also absolutely tear shit apart. 8) David de Gea Slumping as of late but no reason to believe as of yet that it's a permanent drop-off. Probably still unbeatable in this environment. 9) Robert Lewandowski If I were to go with a purer-striker it'd have to Lewy. 10) Simon Mignolet Apparently he has a good penalty-saving record on a bigger sample size than most other goalkeepers. Maybe that means something. If not, well I feel he is owed some slack for all the abuse he has received over the years. Namaste.

A Beginner's Guide To Analyzing Players Using Stats

Last week Kirsten Schlewtiz and I talked about the basics of football analytics. We had so much fun that we decided to do it again this week. Specifically, we’re going to talk through what it’s like to use stats to analyze a player. What it adds, what it misses, and how best to understand what’s going on if you’ve never seen a number that didn’t give you flashbacks to failing a test at ten years old. So, take it away Kirsten.

KS: Mike, personally I had to pass AP stats to graduate high school and I’m still not sure how I did it … likely something to do with those giant TI-85 calculators and a notecard hidden inside the case. Anyway, we want a player to talk about. There’s the top two in the world, but that’d be boring; besides, Lionel Messi has been covered exhaustively on this site. We could analyze the Borussia Dortmund teens, but being a Gladbach fan, that’s too big a reach.

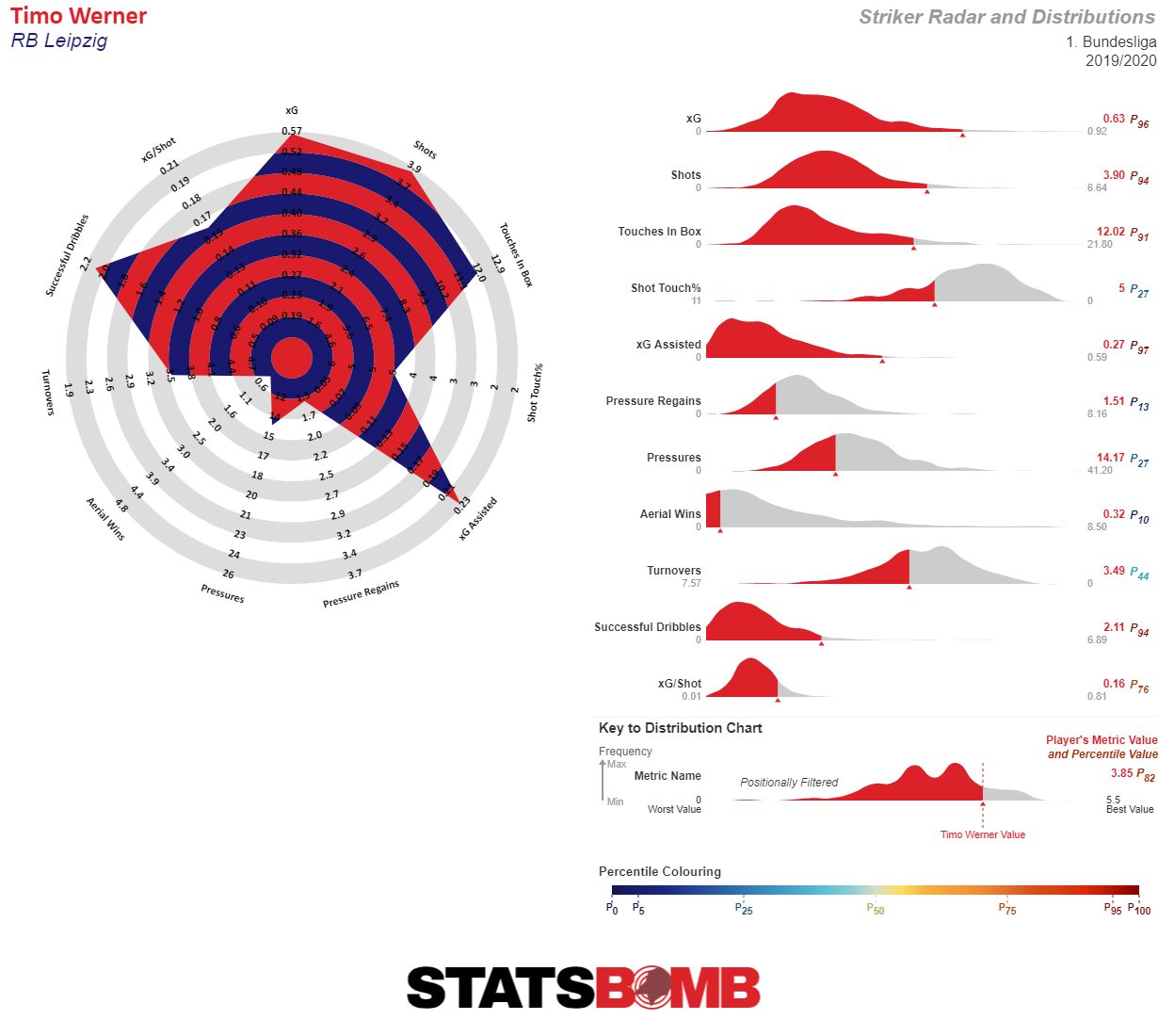

So let’s go with Timo Werner. He’s fast, he’s capable, and he’s helping light up the league with RB Leipzig. But those who have seen him with the Germany national team only likely have more disparaging words to say about the attacker. So what’s the first statistical value we can use to establish his dominance?

MG: Werner’s a great place to start. For a bunch of reasons. Our go to stat for strikers is expected goals per 90 minutes played. We do that for a few reasons. First, we want to look at expected goals and not actual goals because finishing is very noisy but getting good shots is a pretty consistent skill. That’s not to say that individual players aren’t good finishers, the best strikers in the world as a group do tend to average a little higher finishing than a model would predict, but that’s a relatively small part of the picture. The majority of what separates the best from the rest is their ability to find and take lots of good shots. Then we look at it per 90 minutes played because we want to be able to compare players based on what they do when they are on the pitch. You’d rather have a player that plays most of the game and scores a lot of goals than one who plays absolutely all the minutes but only scores a little bit more. So, on to Werner. He averages 0.59 xG per 90. That’s really good. Of players who have played over 900 minutes, only Robert Lewandowski is better, though he’s at 0.79 which is kind of a “break the game” obscenely high level. Does that all make some semblance of sense?

KS: You say we should first look at expected goals, but despite being with StatsBomb for nearly six months, and recognizing the importance of that stat, I still don’t know how you arrive at a player’s xG. I assume you don’t just have a bunch of drones watching that player and inputting their thoughts about when they should score a goal, as opposed to when they actually do. So how is it calculated?

MG: So the way the stat works is it takes tons of factors into consideration and then measures how likely any individual shot is to become a goal given those factors. Start with the location on the pitch, and see how many of the thousands of shots we have go in from there, then keep adding in factors like what part of the body the shot was taken with, what kind of pass led to the shot, was it a set play or not, where were the defenders at the time the shot was taken (a feature unique to StatsBomb data). Then do some fancy math to make it as accurate as possible and you have an xG model. The thing about these models is that they aren’t all that useful when looking at an individual shot because individual shots can vary a lot. But, when the shots start to add up you get a pretty accurate picture of how often a player or team will score.

KS: Focus, Mike — we’re leaving teams for next week. So turning back to individuals, how many shots would you need to come up with a decent estimation? I’m going to assume there are certain players you just wouldn’t have a reliable xG for, such as goalkeepers, but I’m guessing there’s a cutoff point. And Timo’s clearly made that point, as evidenced by you saying his xG is really good . . . but given you don’t mention an average xG, then we need to both take your word that there is a number of shots that should be taken, and that Timo’s number is high enough for him to be measured and come out looking quite grand.

MG: Good question! There’s two ways to look at that. If you’re asking how many shots does it take to ensure that xG is faithfully representing how many goals a player should have scored from the shots he’s taken, the answer is very few. That’s because an xG model is built on all the shots that everybody across the sport has taken. Though to give you a specific answer I’d have to point to things like confidence intervals, and such, and I don’t want to give you flashbacks to high school. The second way to interpret the question is trickier, because if you’re asking how long before we know that Timo Werner’s xG per 90 so far this season of 0.59 is what his xG will continue to be in the future, well we don’t have a good answer for that. Individual stats are contextual and lots of things can change. For example, young players get better. Werner is 24 right now and entering what we’d anticipate to be his peak performance years, but there’s a considerable amount of variability in how any individual player will develop. He’s great now but does that mean he’s done getting better or there’s more to come? And even if his skill level is done improving lots of other things can change. He could change teams, he could get injured, the division of his minutes between the wing and striker could shift dramatically. He could decide that he really likes ice cream and doesn’t like to exercise. The universe is vast and the future is unknowable. So, why use xG at all then? Because even though we can’t say with certainty what the future holds, we can say that xG is better at explaining how good Werner is now, and how good he will be in the future than actual goals scored is. It’s true that his xG might move around a lot in the years to come, but it’s simply better at predicting how good he’ll be than his actual goals scored number. To that end, he’s scored 0.88 goals per 90 this season in the Bundesliga, so we should expect that his xG is a more accurate representation of what he’ll be going forward than the goals.

KS: Actually, what I meant was how do we know that 0.59 is very good? Apparently, I need to work on writing clarity.

MG: Well that one’s easy! You know it’s good because it’s the second highest in the Bundesliga. Also, conveniently it lines up with the “goal every other game” common wisdom about strikers that has floated around forever.

KS: You mentioned his division between winger and striker. I feel like he hasn’t performed well for the German men’s national team because he’s been alone up top. I know StatsBomb has limited national team stats, but I’m sure that even without those, there’s a way to use stats to either affirm or deny my assertion that Werner just doesn’t function as well in that role. Am I right?

MG: It’s actually more difficult to parse that out than you’d think. It’s definitely true that he struggled at the World Cup in 2018 where he only averaged 0.22 xG per 90 minutes while playing two-thirds of his time as striker. Is it because of something he’s doing as a forward? Is it because of how Germany elected to play as a team? Is it because three games is a tiny sample? The answer to all those questions is maybe. But one thing it’s worth noting is that Werner is himself much more than a pure goalscorer. And even during a disastrous World Cup the other stuff he does stands out, He actually assisted almost as much xG, 0.20 per 90, as he attempted himself. And those other statistics are something that make him stand out during club play as well. In addition to being a great goal scorer he’s a great creator, a feature of his game that persisted at a national level even during periods where his goal scoring seems to have abandoned him.

KS: Ugh, Mike, you took my next question; it was meant to be about more than Werner’s goalscoring abilities, and assessing him as an all-around attacker. So let’s talk about speed. To my semi-trained eye, Timo appears quite quick on the pitch, allowing him to link up with his teammates up front. You’ve already mentioned he’s able to provide assists (although feel free to tell us the statistical term used for that, along with his numbers for RB Leipzig thus far this season), but is there any way to measure just how fast a player is?

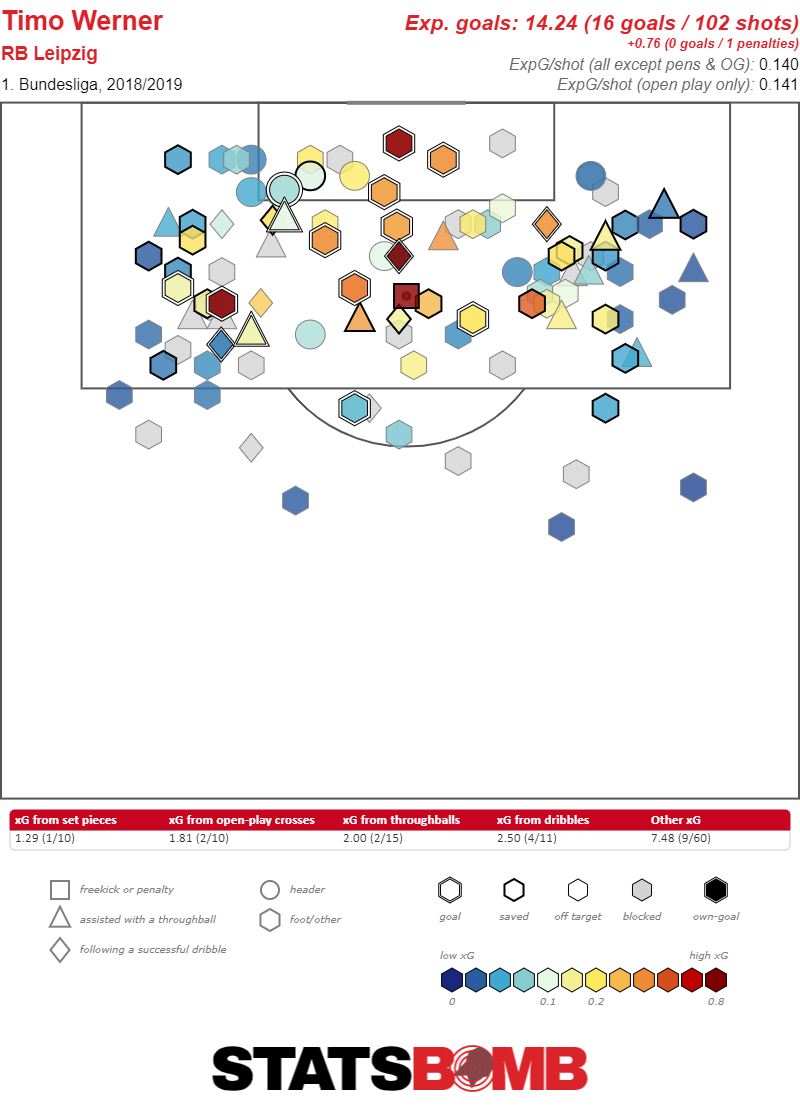

MG: So, it’s deceptively difficult to measure the actual speed a player is running at, although teams can do things like make players don wearable technology to help with that kind of thing. But, for our purposes we’re looking at the things that enable performance on the pitch. So, for example, we can look at a shot chart from Werner and look for all the shots that come as a result of him receiving a throughball (the little triangles).

Or we can look at where and how he’s receiving certain kinds of passes. Below are all the passes he received in the attacking half which originated in his team’s own half. And what we can see is that he consistently peels off to the side — usually the left — and receives balls, the pattern of a player running the channels as a speedster rather than one who is a more central physical target man.

These are all somewhat indirect ways of using the data to get at the underlying reality but they paint the picture of a player whose speed is a central part of his game.

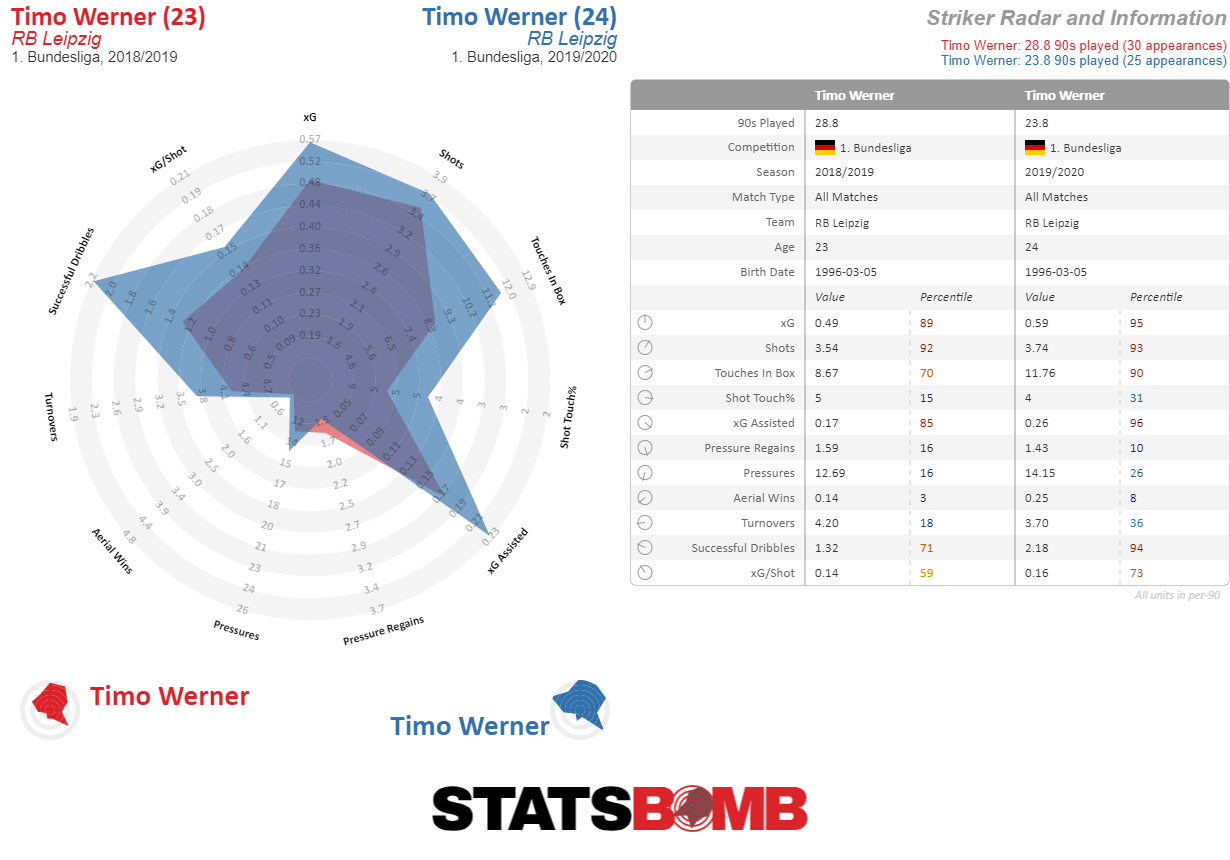

KS: Ok, I think one final question should cover both my impressions of Timo, and the use of numbers to really parse out an attacker’s abilities. Being a big Bundesliga fan, he’s been on my radar for awhile, and it feels to me that while Leipzig as a team have improved considerably in the last few years, Werner’s passing in particular has also improved. Are there any stats that back up what I think I’ve been seeing? MG: Well, RB are an interesting case as a team, since they arrived in the Bundesliga under such unusual circumstances and qualified for the Champions League their first season there. But, I’m not supposed to be talking about teams. Werner himself has certainly improved. Maybe the easiest way to show it is to just do a visual representation of his collection of stats last season vs his collection of stats this season?

The radar shows how he’s doing basically the same things this season that he did last season,.but a lot more of them. How much of that is him developing as a player, and how much of that is his team improving? That’s something that is as much art as science to diagnose. So, the answer is that he’s playing better this year than last and his team is as well, but those two facts are difficult to disentangle. That seems like a good place to leave things for now, although there’s always a lot more to cover. We haven’t even touched on xG per shot or set pieces, or any of the other ways we profile how a striker gets their xG. But that’ll just have to wait for another week.

StatsBomb Champions League Primer: RB Leipzig vs Tottenham Hotspur and Valencia vs Atalanta

The world might be upended by coronavirus but the Champions League is set to march on. So do we with our previews.

RB Leipzig v Tottenham Hotspur

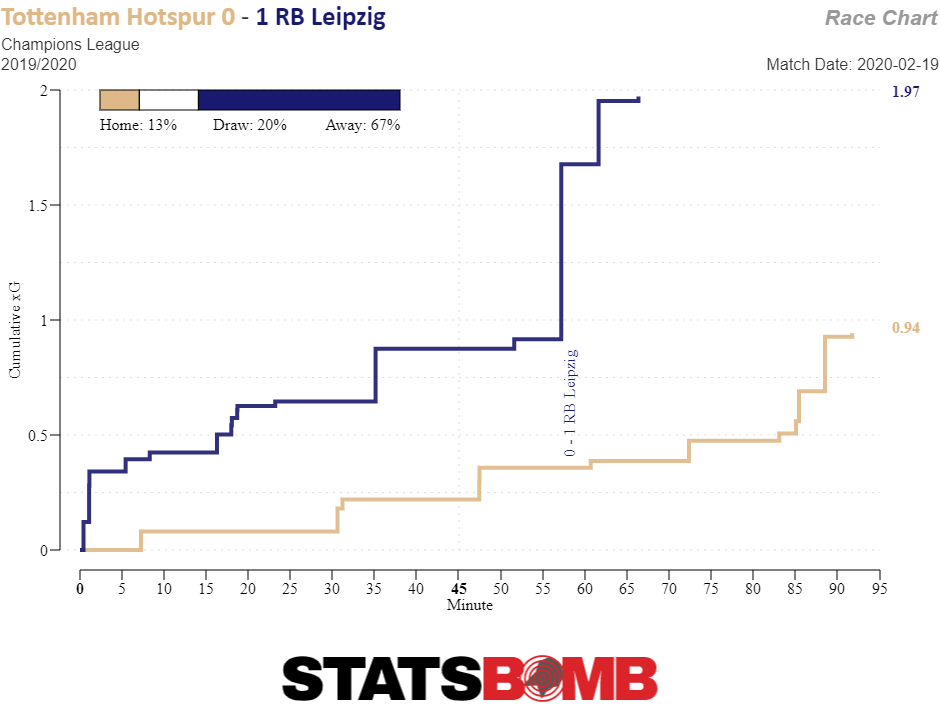

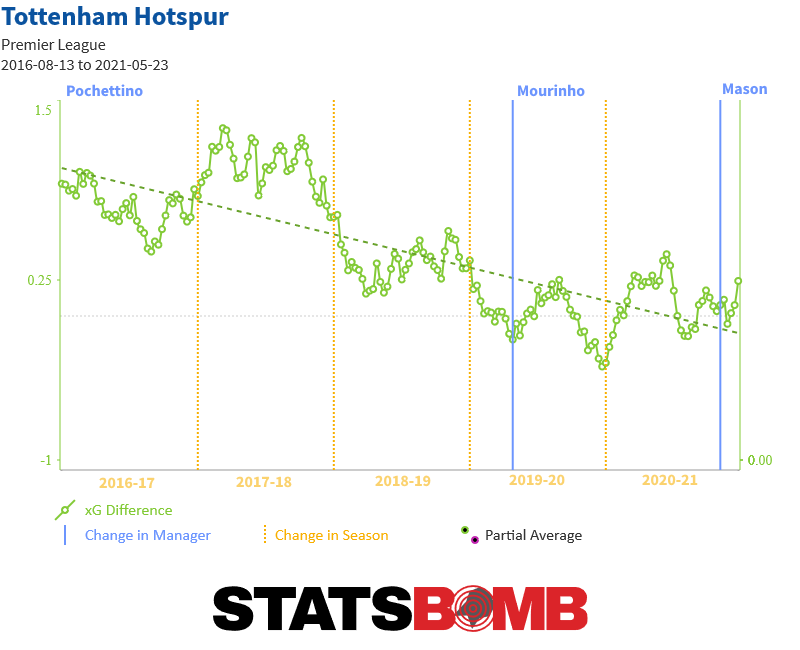

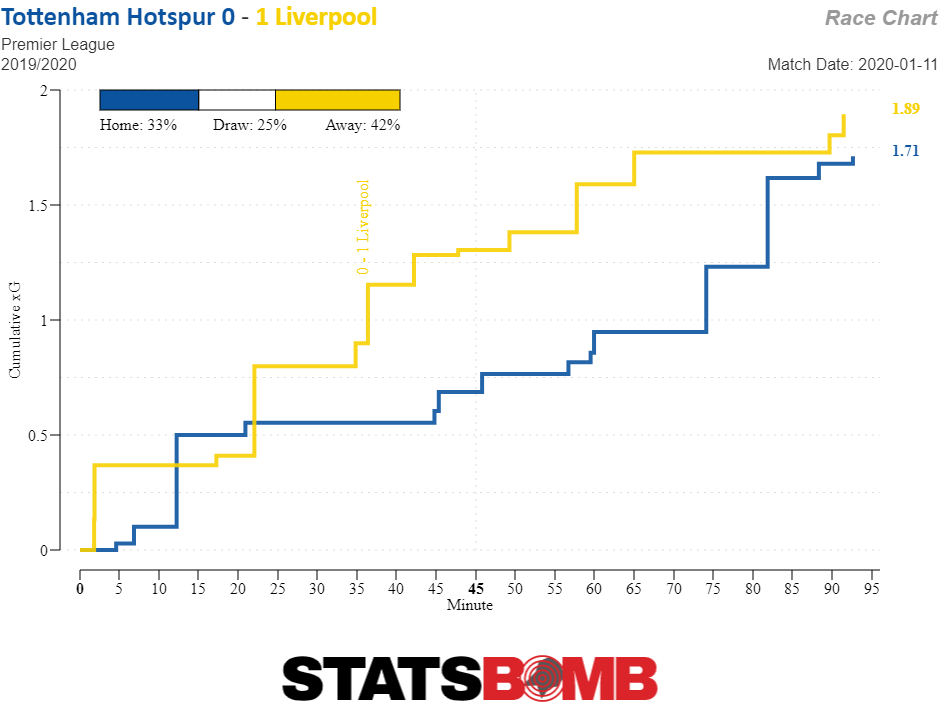

The good news for Spurs is that they’re only down a goal. The bad news is that Leipzig were very good value for the away goal they scored.  Spurs' problems have been well documented over the past month, with the side basically giving back all of the performance gains that new manager José Mourinho initially brought with him

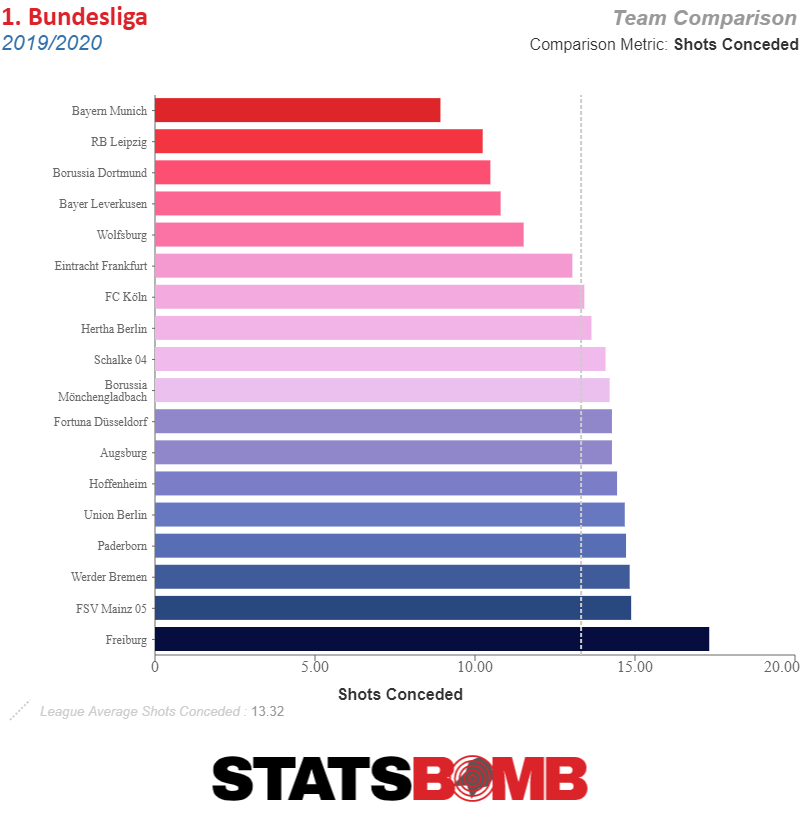

Spurs' problems have been well documented over the past month, with the side basically giving back all of the performance gains that new manager José Mourinho initially brought with him  The team's injury crisis is apparent with January signing Steven Bergwijn joining Harry Kane and Son Heung-min on the sideline. Domestically, especially against teams with less talent, there’s room for debate about whether or not Mourinho could make certain tactical choices to get the most out of his remaining squad. Against Leipzig, however, the team is in a bind. With so few healthy attackers, and no true forward to speak of, Spurs simply cannot execute Mourinho’s desired approach of bending but not breaking and then counterattacking at lightning speed. They have no one to counterattack through. Conversely, if they try to hold the ball against Leipzig, they'd have both trouble moving it up the field and a lack of presence in the box to act as a focal point. Meanwhile, they’d expose themselves to a lightning-fast and efficient counterattack from the German side. Meanwhile, for Leipzig, while it’s the team’s attack that often garners attention, their defense is what will likely be on display as they attempt to see out the tie. And the team defends very very well. They’re a classic shot-suppression side, conceding the second-fewest shots in Germany.

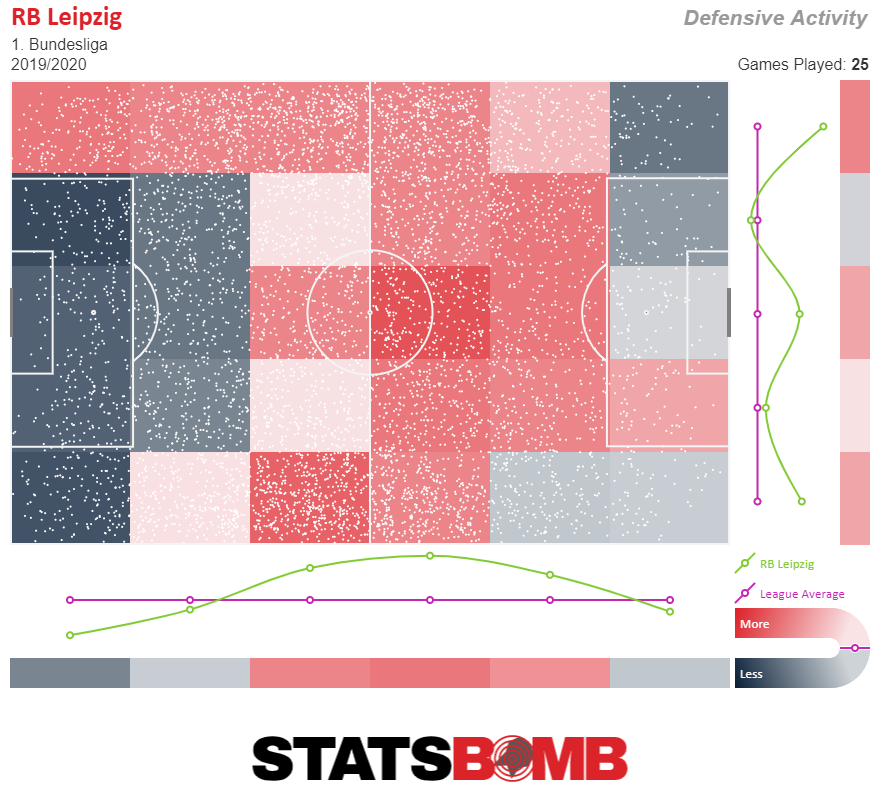

The team's injury crisis is apparent with January signing Steven Bergwijn joining Harry Kane and Son Heung-min on the sideline. Domestically, especially against teams with less talent, there’s room for debate about whether or not Mourinho could make certain tactical choices to get the most out of his remaining squad. Against Leipzig, however, the team is in a bind. With so few healthy attackers, and no true forward to speak of, Spurs simply cannot execute Mourinho’s desired approach of bending but not breaking and then counterattacking at lightning speed. They have no one to counterattack through. Conversely, if they try to hold the ball against Leipzig, they'd have both trouble moving it up the field and a lack of presence in the box to act as a focal point. Meanwhile, they’d expose themselves to a lightning-fast and efficient counterattack from the German side. Meanwhile, for Leipzig, while it’s the team’s attack that often garners attention, their defense is what will likely be on display as they attempt to see out the tie. And the team defends very very well. They’re a classic shot-suppression side, conceding the second-fewest shots in Germany.  Leipzig want to defend far from their own goal, and to force teams to beat an aggressive press to create chances.

Leipzig want to defend far from their own goal, and to force teams to beat an aggressive press to create chances.  That’s why this task is so daunting for Mourinho. He’s a manager that normally is happy to play against an aggressive pressing team. He wants to invite pressure and then beat it through the combination of a target forward and a speedy attacking winger executing fast and efficient counterattacks. Unfortunately for Spurs, their target forward and fast creative winger won’t be playing. For Tottenham to have a chance at staging a comeback they'll have to solve the exact problem that’s been hounding this side for weeks. They’re going to need to break a press without press breakers.

That’s why this task is so daunting for Mourinho. He’s a manager that normally is happy to play against an aggressive pressing team. He wants to invite pressure and then beat it through the combination of a target forward and a speedy attacking winger executing fast and efficient counterattacks. Unfortunately for Spurs, their target forward and fast creative winger won’t be playing. For Tottenham to have a chance at staging a comeback they'll have to solve the exact problem that’s been hounding this side for weeks. They’re going to need to break a press without press breakers.

Valencia v Atalanta

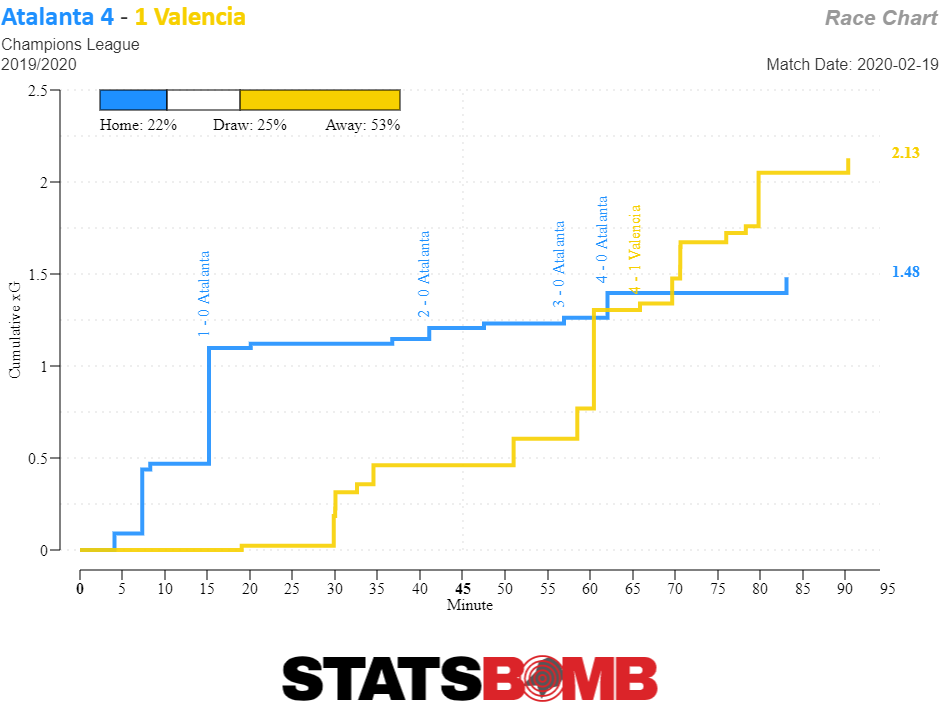

Sometimes there are more important things than sports. And for the northern Italian side this is one of those times. Amidst the coronavirus crisis, the squad has played only one match since beating Valencia 4–1 at home on February 19th, breaking apart Lecce 2–7 on the first of the month. The good sporting news for Atalanta is that they have clearly been the better side, and they travel to Valencia with quite a cushion after their 4–1 victory in the reverse fixture. Valencia do have something to hang their hopes on though, and it’s that the first leg wasn’t nearly as lopsided as it seemed. While Atalanta scored early and put the game to bed shortly after halftime, Valencia really did find a lot of attacking joy over the final half hour.  The usual pattern of a match like this would be Valencia, trailing at home, would have a ton of the ball and Atalanta would try to defend against a desperate onslaught and put the game away on the counter. A number of famous comebacks over the last few seasons have followed this pattern and resulted in the trailing team getting a needed result. But neither Valencia nor Atalanta fit that mould. Atalanta are addicted to having the ball. And Valencia are one of the deepest defending teams in the world. If Valencia do stage a major comeback it would be because Atalanta simply don’t have the capacity to play cautiously and Valencia manage to take advantage three times. The team does have the fourth-highest expected goals per shot value in La Liga, so a comeback is not out of the realm of possibility.

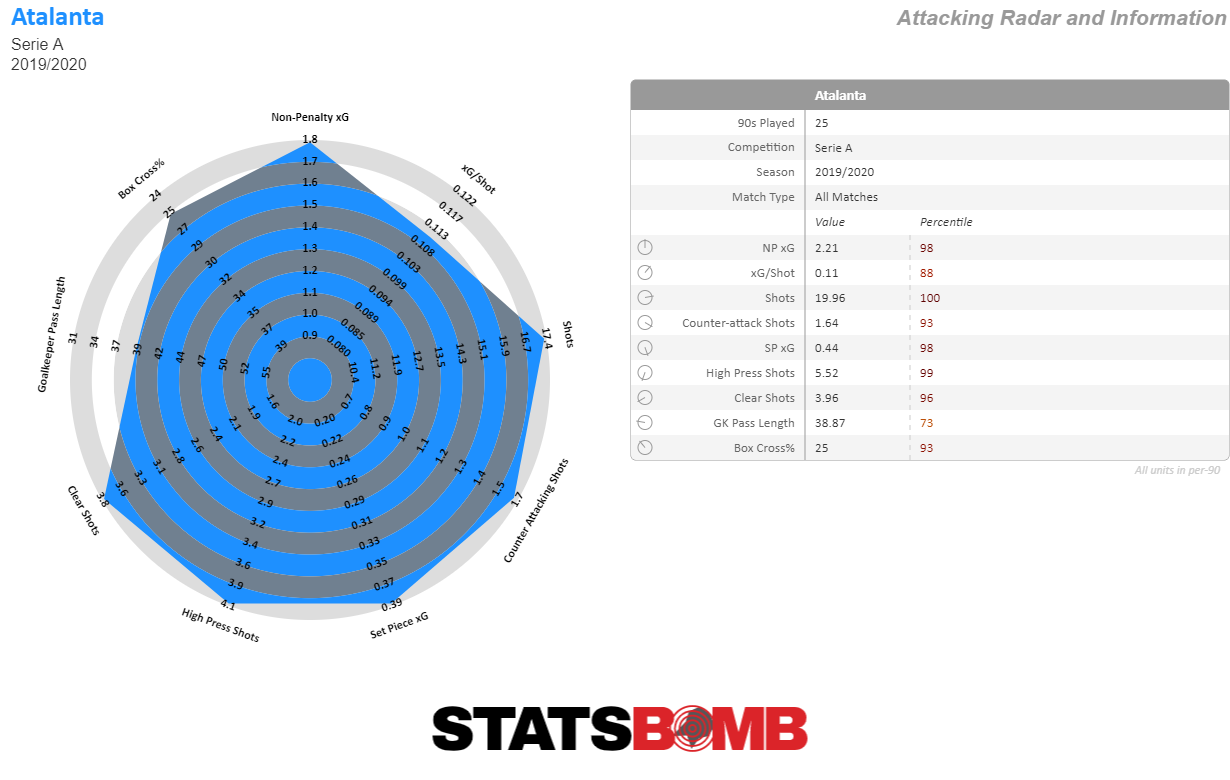

The usual pattern of a match like this would be Valencia, trailing at home, would have a ton of the ball and Atalanta would try to defend against a desperate onslaught and put the game away on the counter. A number of famous comebacks over the last few seasons have followed this pattern and resulted in the trailing team getting a needed result. But neither Valencia nor Atalanta fit that mould. Atalanta are addicted to having the ball. And Valencia are one of the deepest defending teams in the world. If Valencia do stage a major comeback it would be because Atalanta simply don’t have the capacity to play cautiously and Valencia manage to take advantage three times. The team does have the fourth-highest expected goals per shot value in La Liga, so a comeback is not out of the realm of possibility.  The most likely outcome is that Atalanta just keep on scoring and win this battle easily. The side puts up the kinds of attacking totals that any team in the world would be proud of. It’s hard to imagine they won’t put one or two past Valencia unless they end up confronted with a terrible finishing streak. Stranger things have happened, but there’s no reason to expect it.

The most likely outcome is that Atalanta just keep on scoring and win this battle easily. The side puts up the kinds of attacking totals that any team in the world would be proud of. It’s hard to imagine they won’t put one or two past Valencia unless they end up confronted with a terrible finishing streak. Stranger things have happened, but there’s no reason to expect it.  One of the challenges of analyzing this Champions League season is the fact that some teams are simply much better than their reputations. Atalanta tops that list. They’re just so beyond Valencia that it's hard to imagine them blowing this lead without a whole bunch of luck going against them.

One of the challenges of analyzing this Champions League season is the fact that some teams are simply much better than their reputations. Atalanta tops that list. They’re just so beyond Valencia that it's hard to imagine them blowing this lead without a whole bunch of luck going against them.

Why aren't Manchester City better?

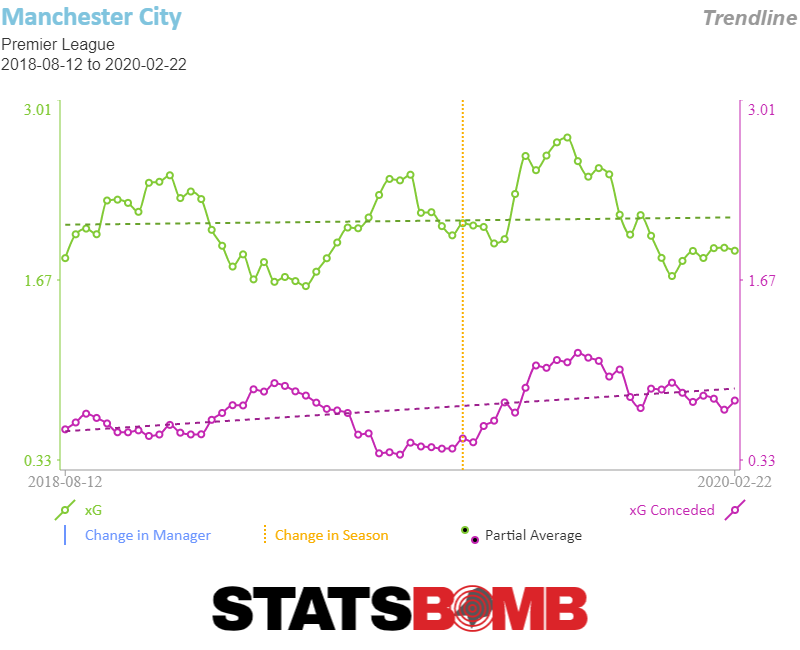

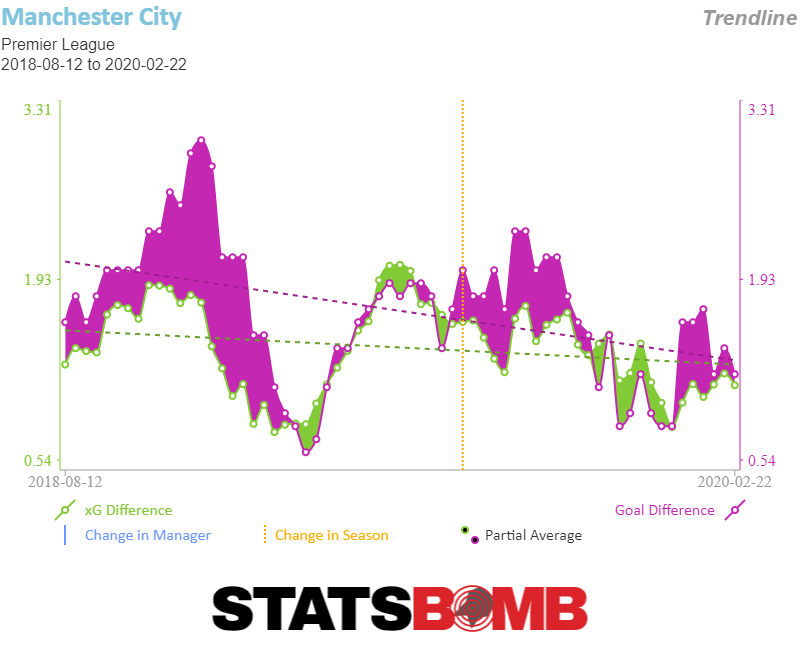

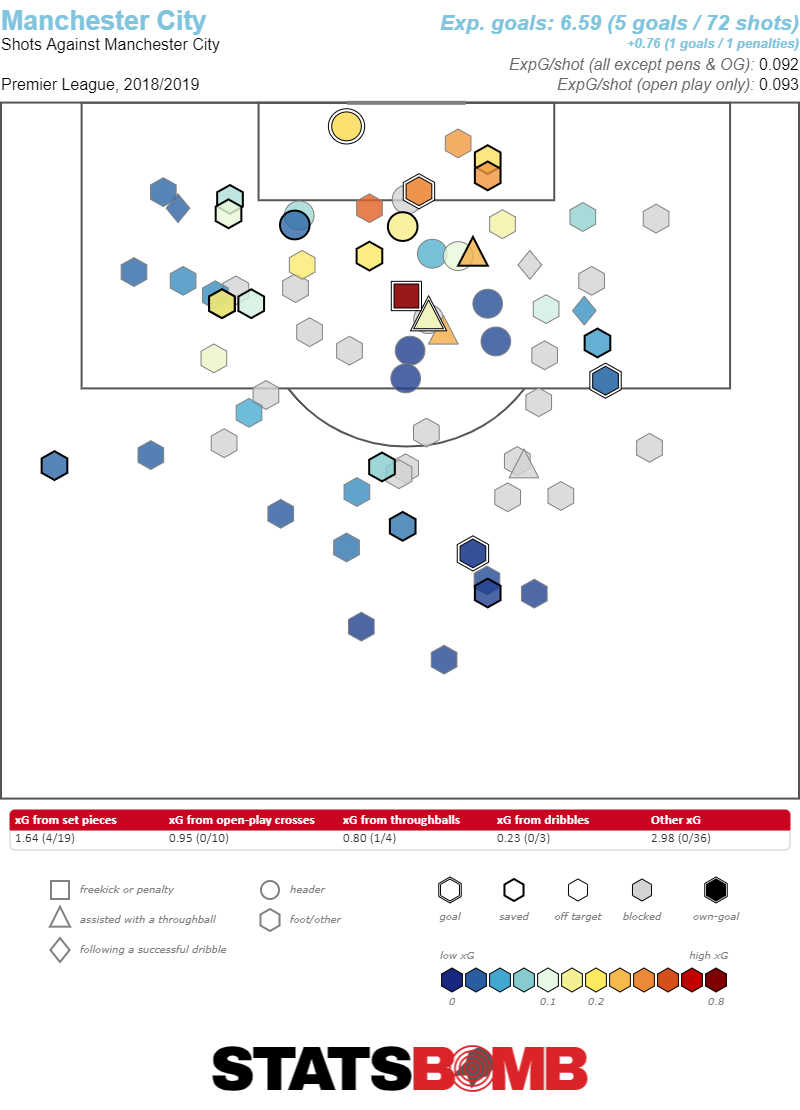

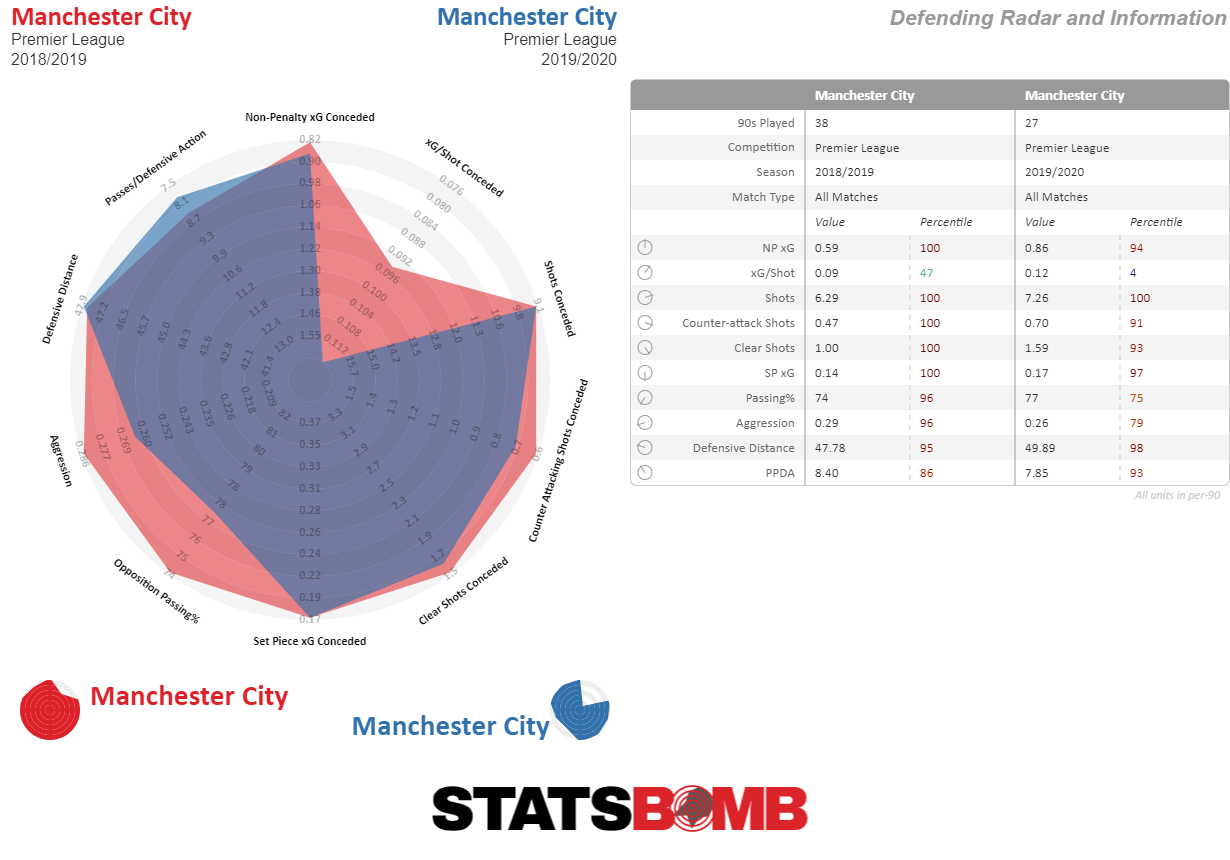

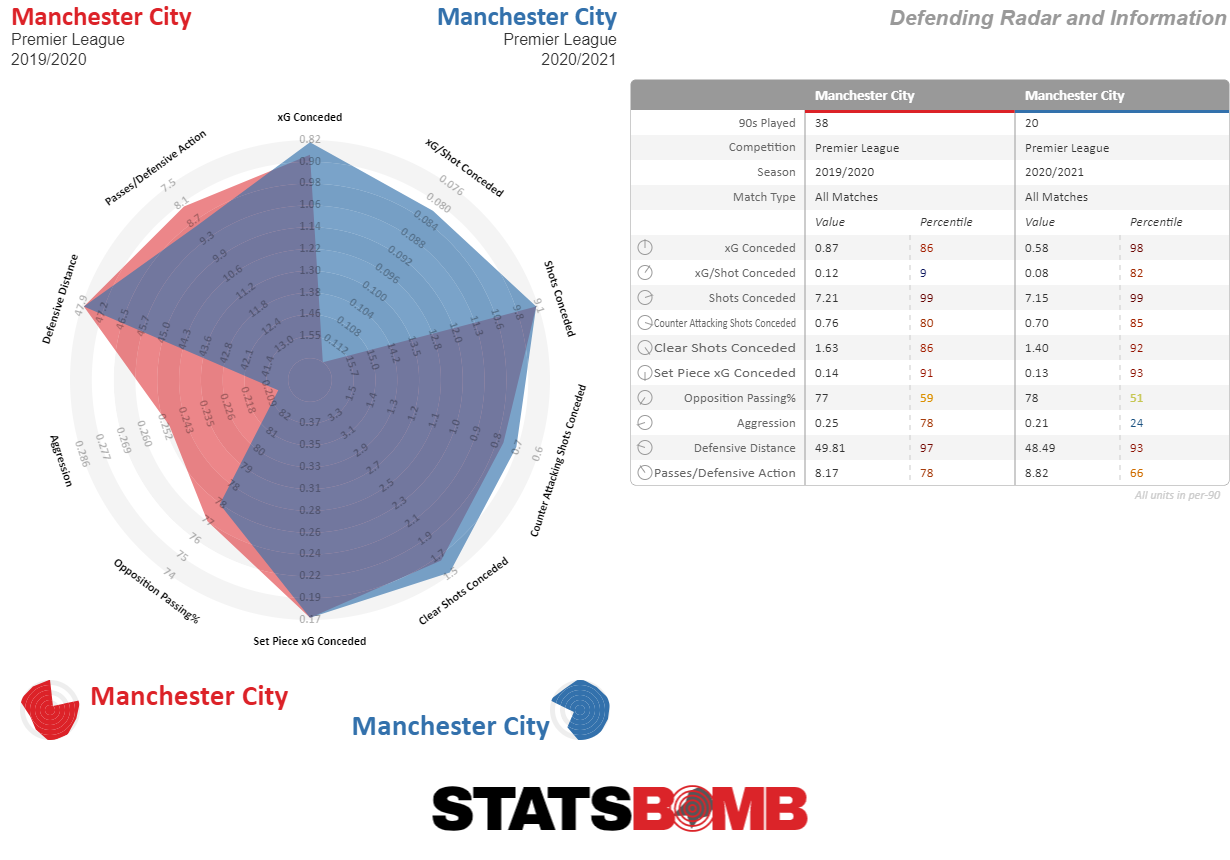

Manchester City are in second place in the Premier League. They just won the League Cup. After going to Madrid and beating Real 1-2 they’re likely on their way to the Champions League quarterfinals. But they’re only on pace for slightly over 80 points. That’s a major dip from 98 last season and 100 the year before that. Why aren’t Manchester City better? The basic underlying numbers suggest that there might be some slight deterioration over the last couple of seasons, but nothing major. City’s defense seems slightly worse than it has been, but again this seems like largely the same performance level just with massively different results.  Given that you’d expect that perhaps the side either massively overperformed their expected goals last season or were massively underperforming it this year. But, that’s not particularly true either. In fact while City have had stretches where they’ve been over xG, sometimes by quite a lot, they haven’t had very many long periods where they’ve been classic underperformers.

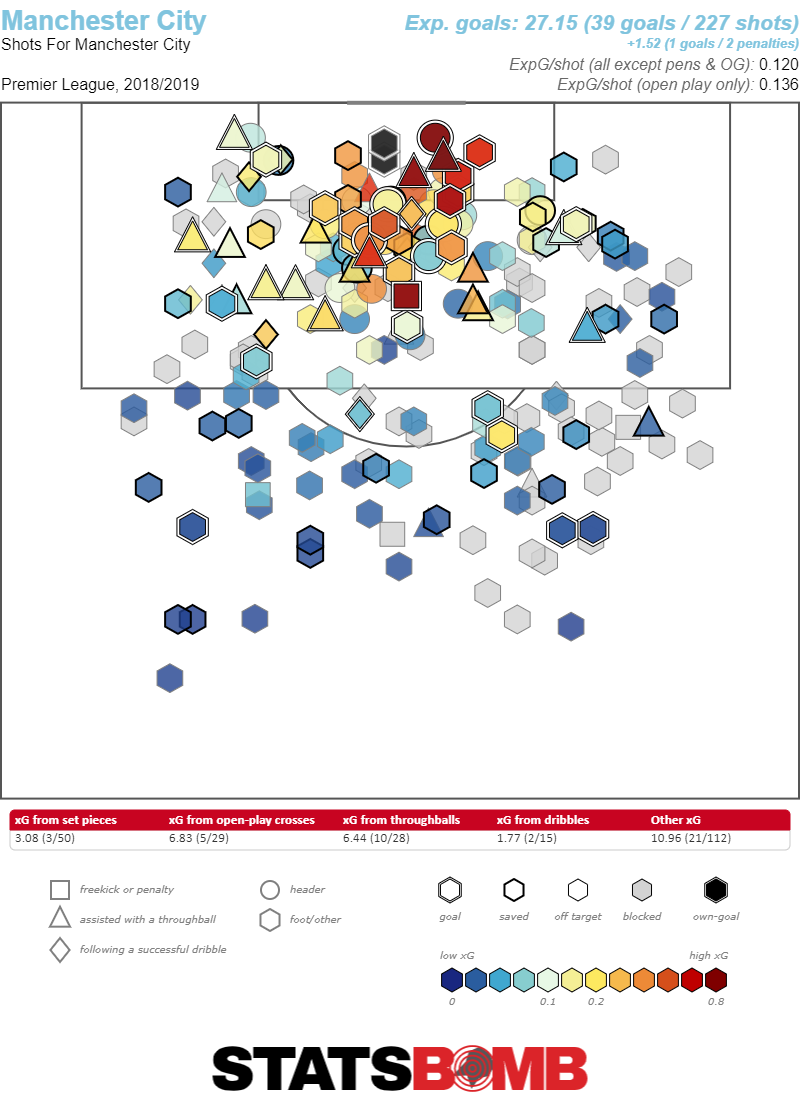

Given that you’d expect that perhaps the side either massively overperformed their expected goals last season or were massively underperforming it this year. But, that’s not particularly true either. In fact while City have had stretches where they’ve been over xG, sometimes by quite a lot, they haven’t had very many long periods where they’ve been classic underperformers.  What we can see on the chart from this season and last is that while City did run pretty hot early in the 2018-19 season, what we’ve seen is the side’s goal difference converge with it’s xG difference (which is gratifying to stats nerds since that’s exactly what’s supposed to happen), while that xG average has fluctuated around a relatively consistent level. But, just because those topline numbers are only minorly different, doesn’t mean there isn’t more to investigate under the hood. Prying apart those xG numbers show a team which has some major differences in both performance and execution year over year. During City’s great 2018-19 season they ran way over expectation when the match was tied, putting up 39 goals from 27.15 xG. It’s nice work if you can get it. Last season, City was the best team while also getting fortuitous bounces that regularly put Pep Guardiola’s side ahead.

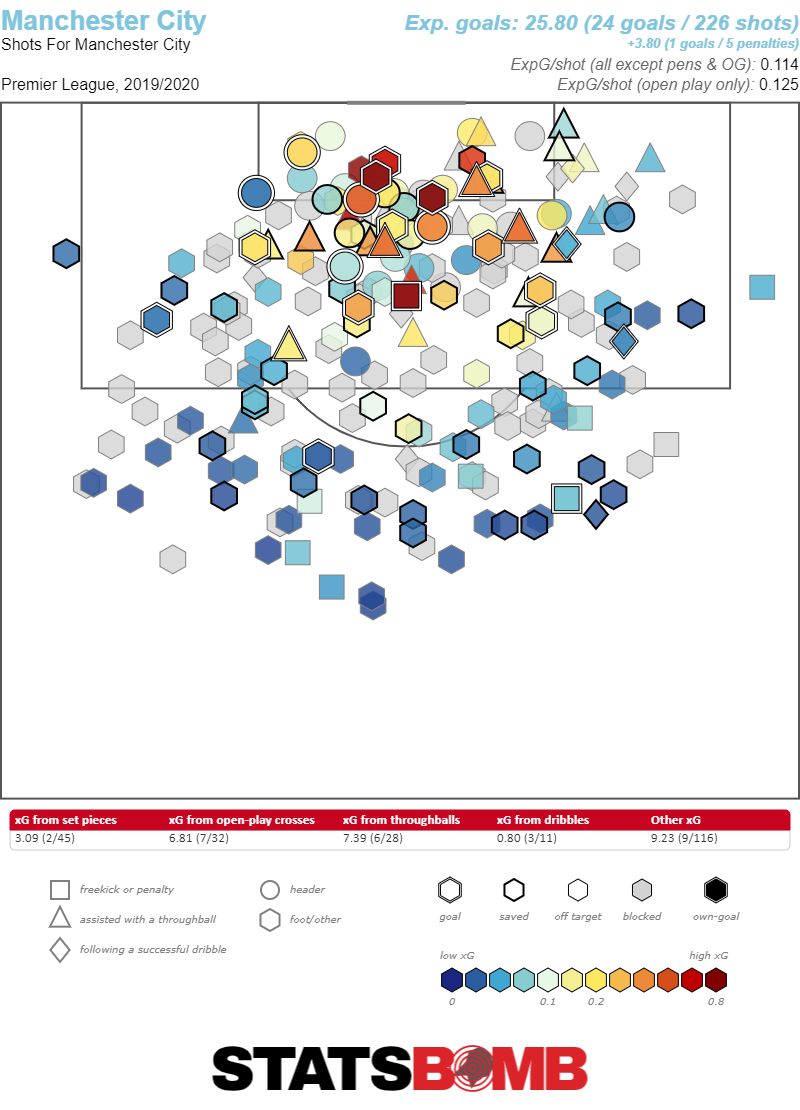

What we can see on the chart from this season and last is that while City did run pretty hot early in the 2018-19 season, what we’ve seen is the side’s goal difference converge with it’s xG difference (which is gratifying to stats nerds since that’s exactly what’s supposed to happen), while that xG average has fluctuated around a relatively consistent level. But, just because those topline numbers are only minorly different, doesn’t mean there isn’t more to investigate under the hood. Prying apart those xG numbers show a team which has some major differences in both performance and execution year over year. During City’s great 2018-19 season they ran way over expectation when the match was tied, putting up 39 goals from 27.15 xG. It’s nice work if you can get it. Last season, City was the best team while also getting fortuitous bounces that regularly put Pep Guardiola’s side ahead.  This season is a different story. City are actually slightly below their xG when drawing, 24 goals from 25.80 expected.

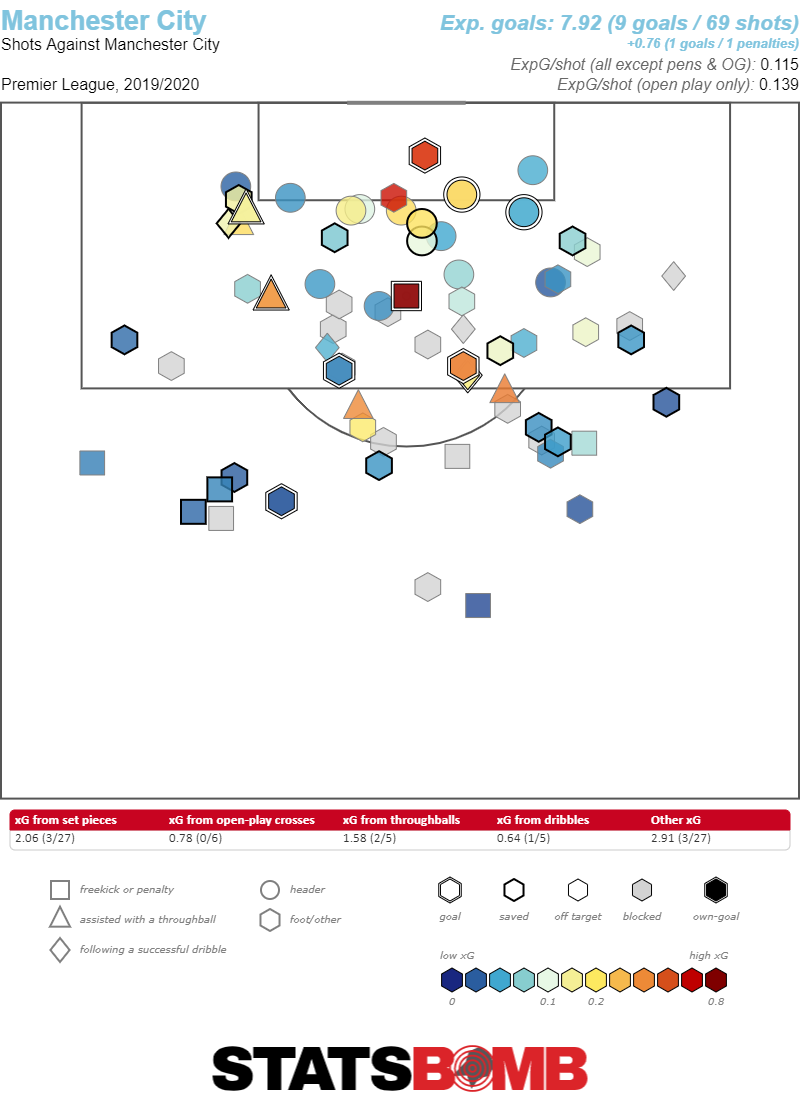

This season is a different story. City are actually slightly below their xG when drawing, 24 goals from 25.80 expected.  The natural result of these differing fortunes is that even when they do ultimately pull ahead it’s taking longer for them to do so. That means just by dint of being tied longer, they’re giving up more goal scoring opportunities and risking falling behind more than they did last season. Already this season they’ve conceded nine goals from just under eight xG.

The natural result of these differing fortunes is that even when they do ultimately pull ahead it’s taking longer for them to do so. That means just by dint of being tied longer, they’re giving up more goal scoring opportunities and risking falling behind more than they did last season. Already this season they’ve conceded nine goals from just under eight xG.  All of last season they only conceded five from just over 7 xG

All of last season they only conceded five from just over 7 xG  This is one of the ways that variance and actual performance levels are inextricably intertwined. It is absolutely fair to say that City have been a worse defensive team when they’ve been drawing this season than last. But the only reason for that is that they’ve had a harder time scoring goals, due to what appears to be a natural swing in variance. Luck, or lack thereof, in one part of the pitch leads to actual deterioration in another. There are of course other factors at play. There have been real personnel changes, with Fernandinho aging out of central midfield and injuries across the defensive line. Perhaps relatedly, the teams defensive solidity has suffered. Specifically, teams complete more passes and create somewhat more high quality shots when they break through City’s outstanding aggressive press.

This is one of the ways that variance and actual performance levels are inextricably intertwined. It is absolutely fair to say that City have been a worse defensive team when they’ve been drawing this season than last. But the only reason for that is that they’ve had a harder time scoring goals, due to what appears to be a natural swing in variance. Luck, or lack thereof, in one part of the pitch leads to actual deterioration in another. There are of course other factors at play. There have been real personnel changes, with Fernandinho aging out of central midfield and injuries across the defensive line. Perhaps relatedly, the teams defensive solidity has suffered. Specifically, teams complete more passes and create somewhat more high quality shots when they break through City’s outstanding aggressive press.  The luck factor certainly doesn’t absolve the defense. They’ve become somewhat more porous and no longer seem to have the magical ability to press aggressively while magically never getting exposed on the counterattack. But, given the rest of the data it’s possible that without the bad luck City would be doing enough in attack to entirely offset the defensive problems. The City example is one that illustrates how much art there is in the science of parsing a team’s statistics. The line between luck and skill is often a lot blurrier than a casual observation might led you to believe. Good luck in one area can impact skill in another and vice versa. In the long run the vast majority of these factors average themselves out and become indistinguishable from noise. But, over the short term, when trying to figure out discrete questions like why isn’t City better, the line between luck and skill, becomes much much harder to parse.

The luck factor certainly doesn’t absolve the defense. They’ve become somewhat more porous and no longer seem to have the magical ability to press aggressively while magically never getting exposed on the counterattack. But, given the rest of the data it’s possible that without the bad luck City would be doing enough in attack to entirely offset the defensive problems. The City example is one that illustrates how much art there is in the science of parsing a team’s statistics. The line between luck and skill is often a lot blurrier than a casual observation might led you to believe. Good luck in one area can impact skill in another and vice versa. In the long run the vast majority of these factors average themselves out and become indistinguishable from noise. But, over the short term, when trying to figure out discrete questions like why isn’t City better, the line between luck and skill, becomes much much harder to parse.

StatsBomb Champions League Primer: Lyon vs Juventus and Real Madrid vs Manchester City

Why yes, you can have a little more Champions League as a treat.

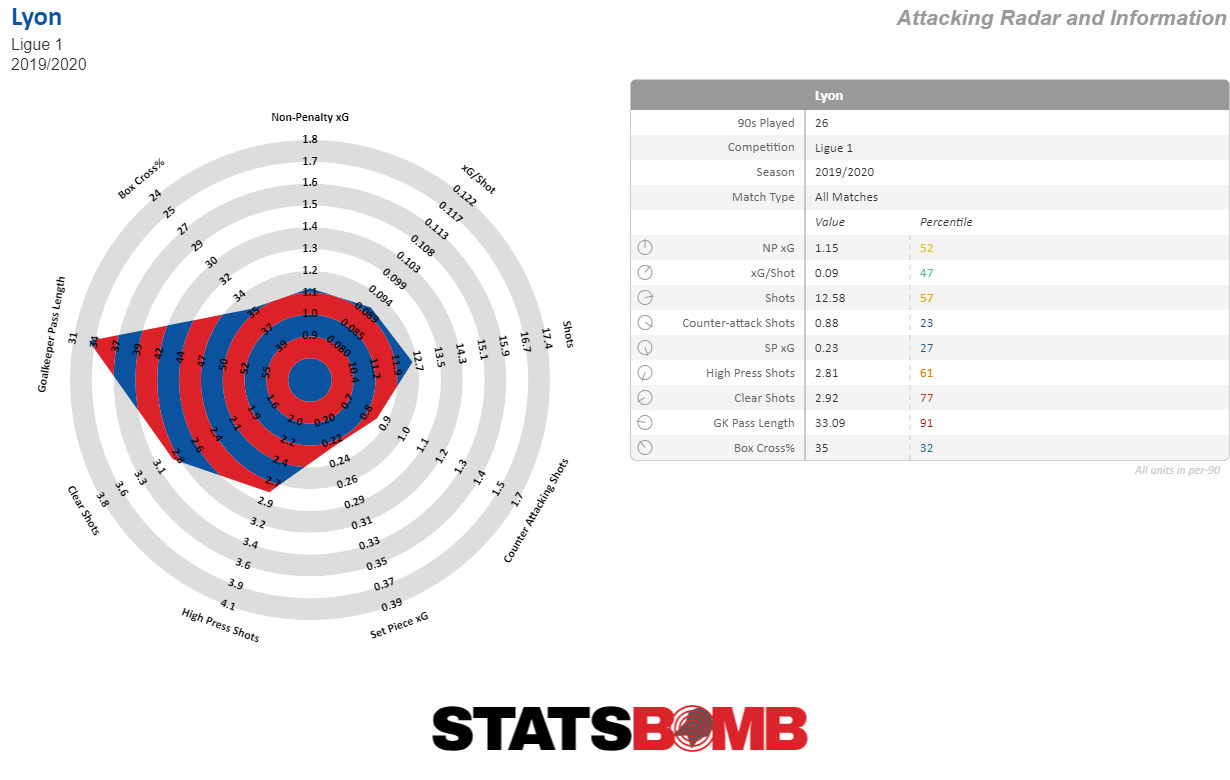

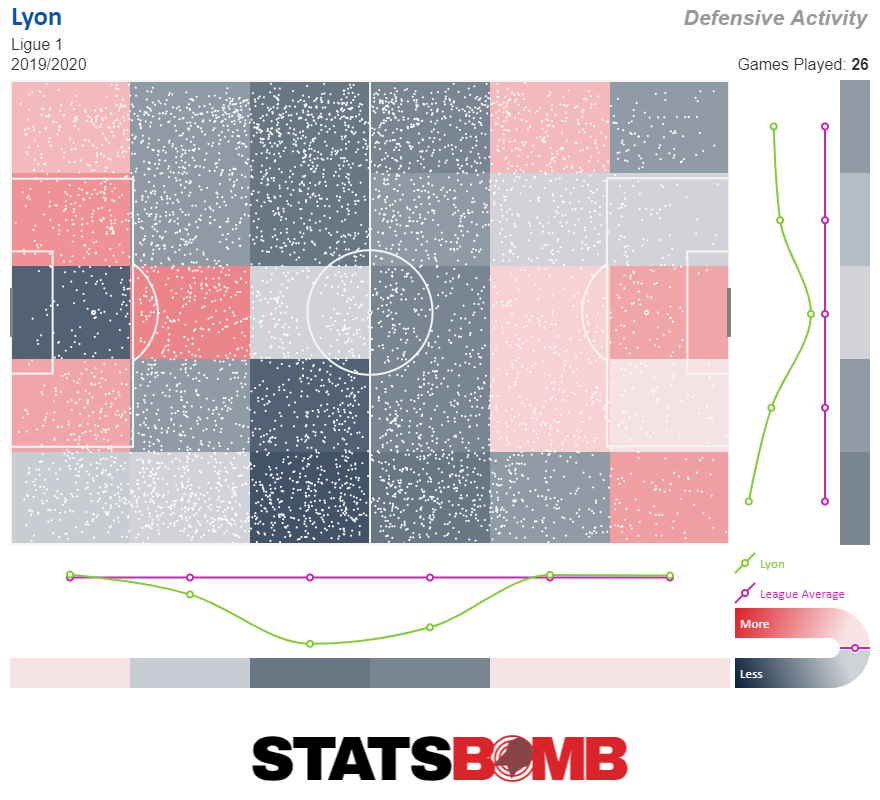

Lyon vs Juventus

There are questions about exactly how good Juventus are this season, but they won’t get answered in their Round of 16 match against Lyon. The French side are comfortably the worst team remaining in the tournament and sit in seventh place in Ligue 1. It’s true that their position slightly underrates their underlying numbers, which are the fourth-best in France, but only slightly. There’s nothing wrong with being a pretty good team in Ligue 1 having a slightly down season, but it’s not going to do much for you in the Champions League knockout stages. And it’s not only that they’re not all that good, it’s also that they aren’t all that interesting. For a team that until this year had been tremendous fun, the outgoing transfers are taking their toll. Tanguy Ndombele is no longer running the midfield. Ferland Mendy has been replaced at left back, and Nabil Fekir is gone in attack. There’s only so much attacking talent a team can lose before they start to look like, well, like this.  Defensively the side is stable and dependable. They concede only 0.88 expected goals per match, the third-best in the league. They’re admittedly very tough to break down, and they remain steady in a fairly unique way. They counterpress high when they lose the ball deep in enemy territory, and otherwise defend very deep, leaving the entire middle of the field to their opponent's control.

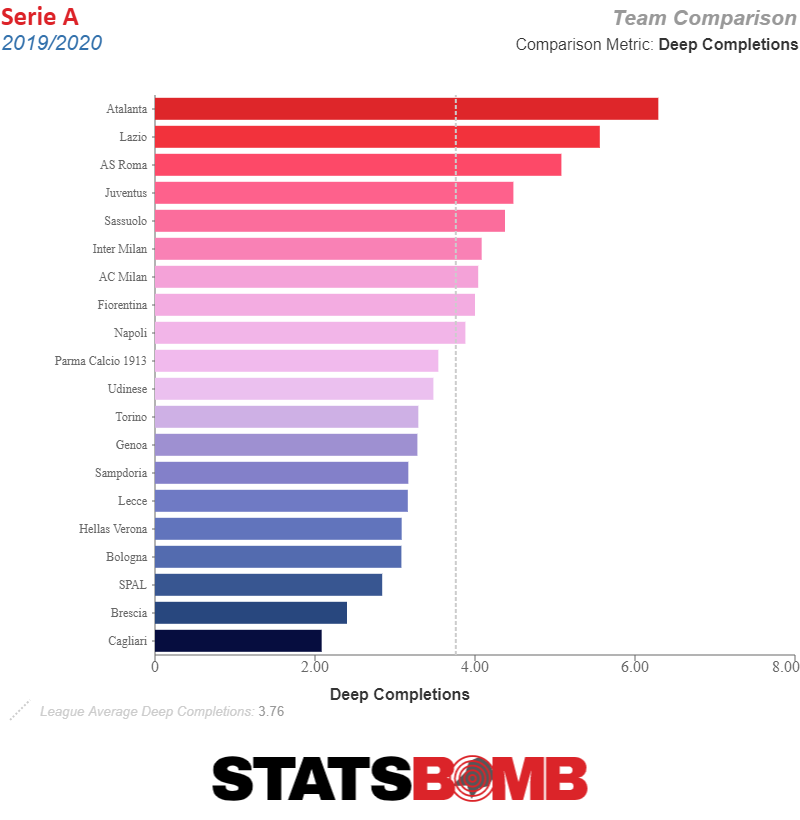

Defensively the side is stable and dependable. They concede only 0.88 expected goals per match, the third-best in the league. They’re admittedly very tough to break down, and they remain steady in a fairly unique way. They counterpress high when they lose the ball deep in enemy territory, and otherwise defend very deep, leaving the entire middle of the field to their opponent's control.  Overall there’s nothing precisely wrong with this team, it’s just that there’s nothing about them that suggests they’re going to be difficult for a team like Juventus to handle. Specifically, a team that cedes the midfield is going to be music to Maurizio Sarri’s very Italian ears. Juventus is perfectly happy to simply keep the ball. They have the highest pass percentage in Serie A at 87% and they virtually never play long; only Napoli play the ball shorter on average than Juventus’s average keeper pass length of 30.28. But, despite the fact that they're comfortable keeping the ball, they aren’t particularly aggressive at moving it into the penalty area. Six teams in Serie A play more passes into the box per match than Juventus, and Atalanta, Roma and Lazio all complete more passes per match within 20 yards of their opponent’s goal as well.

Overall there’s nothing precisely wrong with this team, it’s just that there’s nothing about them that suggests they’re going to be difficult for a team like Juventus to handle. Specifically, a team that cedes the midfield is going to be music to Maurizio Sarri’s very Italian ears. Juventus is perfectly happy to simply keep the ball. They have the highest pass percentage in Serie A at 87% and they virtually never play long; only Napoli play the ball shorter on average than Juventus’s average keeper pass length of 30.28. But, despite the fact that they're comfortable keeping the ball, they aren’t particularly aggressive at moving it into the penalty area. Six teams in Serie A play more passes into the box per match than Juventus, and Atalanta, Roma and Lazio all complete more passes per match within 20 yards of their opponent’s goal as well.  There are reasons to question whether Juventus’s approach of keeping the ball forever, taking lots of shots (their 17.36 per match is third in the league) but being relatively conservative when it comes to moving the ball into the penalty area is a solid approach against better teams. It leaves them somewhat prone to bombing away from distance with mediocre shots, and their 0.09 xG per shot in Serie A is a decidedly average eighth. But, against Lyon, who won’t bother to contest midfield or try to keep the ball, or do much of anything besides kick it long and drop back and defend, it shouldn’t be a problem.

There are reasons to question whether Juventus’s approach of keeping the ball forever, taking lots of shots (their 17.36 per match is third in the league) but being relatively conservative when it comes to moving the ball into the penalty area is a solid approach against better teams. It leaves them somewhat prone to bombing away from distance with mediocre shots, and their 0.09 xG per shot in Serie A is a decidedly average eighth. But, against Lyon, who won’t bother to contest midfield or try to keep the ball, or do much of anything besides kick it long and drop back and defend, it shouldn’t be a problem.

Real Madrid vs Manchester City

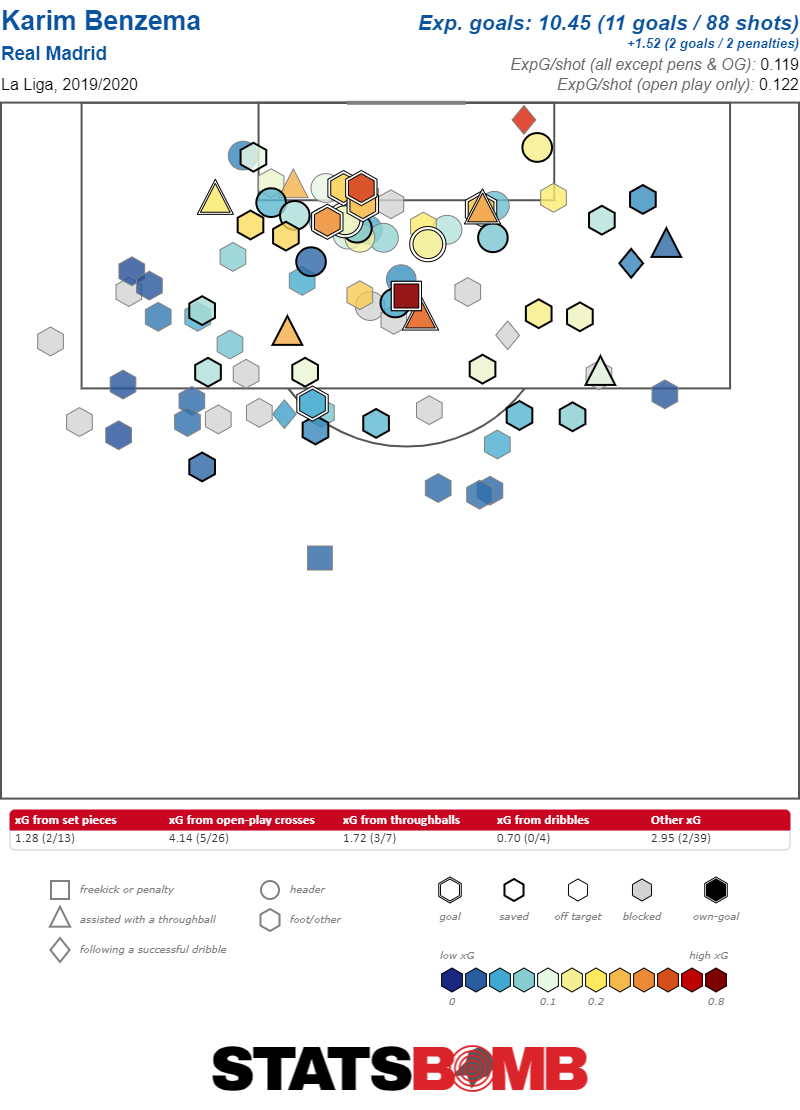

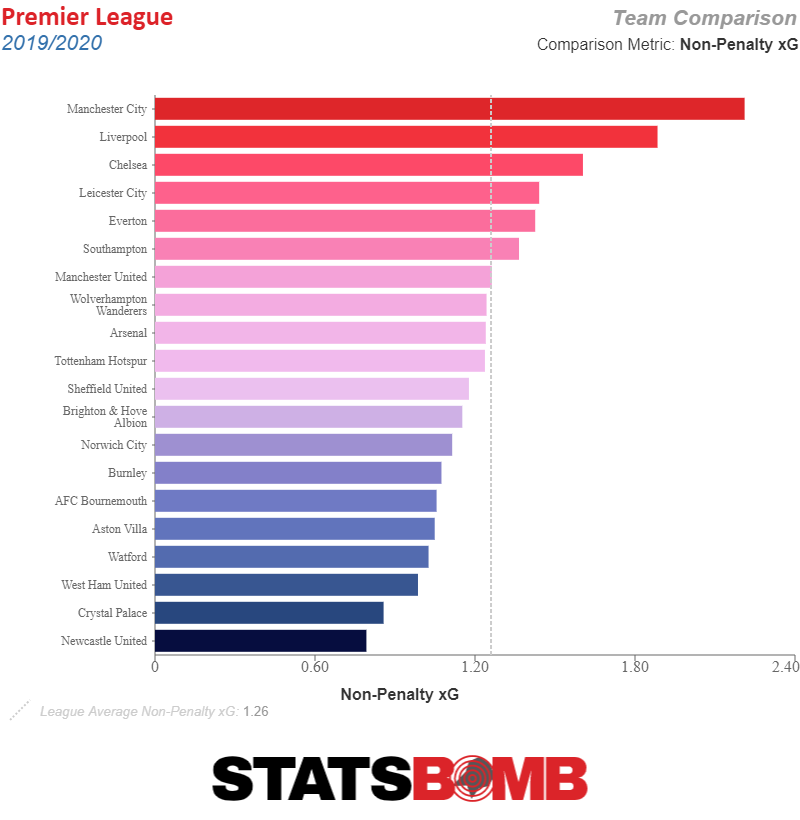

Real Madrid are good. It’s a testament to the turmoil of the last year that this is surprising. Following last season when they sold Cristiano Ronaldo and didn’t replace him, and also tried to replace Zinedine Zidane as manager and failed at that, it seemed like Madrid were going firmly in the wrong direction. But two managers and two-thirds of a season later, Zidane returned and lifted the team back to the top tier of European football. Interestingly, however, that’s not because they’ve replaced Ronaldo’s attacking production. High priced acquisitions Eden Hazard and Luka Jović have failed to make much of an impact this season. Rather Zidane has artfully mixed and matched from a deep pool of attacking wingers while featuring Karim Benzema at striker.  But the real master strike from Zidane was compensating for the ageing duo of Toni Kroos and Luka Modrić by easing the latter into a more limited role and featuring the younger and much more active Fede Valverde instead. Valverde’s inclusion in the squad means that, alongside Casemiro, there are now two more rugged midfielders in the side at any given time. This has turned Madrid into the best defensive team in La Liga with only 0.70 xG conceded per match. The question, however, is whether that defense can hold against a Manchester City side that is legitimately one of the best in the world. Lost in the historic nature of Liverpool’s season is the fact that City’s underlying numbers are actually better than the runaway presumed champions. They are an absurd attacking team. The side’s non-penalty xG of 2.21 is testing the outer limits of the possible and is almost an entire half goal better than their closes attacking competitor, Liverpool.

But the real master strike from Zidane was compensating for the ageing duo of Toni Kroos and Luka Modrić by easing the latter into a more limited role and featuring the younger and much more active Fede Valverde instead. Valverde’s inclusion in the squad means that, alongside Casemiro, there are now two more rugged midfielders in the side at any given time. This has turned Madrid into the best defensive team in La Liga with only 0.70 xG conceded per match. The question, however, is whether that defense can hold against a Manchester City side that is legitimately one of the best in the world. Lost in the historic nature of Liverpool’s season is the fact that City’s underlying numbers are actually better than the runaway presumed champions. They are an absurd attacking team. The side’s non-penalty xG of 2.21 is testing the outer limits of the possible and is almost an entire half goal better than their closes attacking competitor, Liverpool.  This isn’t to say City are perfect. They aren’t quite a vintage Guardiola team, and are vulnerable to the counterattack in a way that the best sides Guardiola has coached over the years have not been. Their defense is still very good; they simply have the ball so much, and are so aggressive at winning it back when they lose it that they concede very few shots. But when counterattacks do happen, they can be exposed.

This isn’t to say City are perfect. They aren’t quite a vintage Guardiola team, and are vulnerable to the counterattack in a way that the best sides Guardiola has coached over the years have not been. Their defense is still very good; they simply have the ball so much, and are so aggressive at winning it back when they lose it that they concede very few shots. But when counterattacks do happen, they can be exposed.  The main question of this match then is how much will Madrid cede possession. City are so high powered that going toe to toe with them is probably a losing proposition, even for a team like Madrid. But, a cagier approach, one which relies on withstanding some degree of pressure before punching back hard, well, that could conceivably work.

The main question of this match then is how much will Madrid cede possession. City are so high powered that going toe to toe with them is probably a losing proposition, even for a team like Madrid. But, a cagier approach, one which relies on withstanding some degree of pressure before punching back hard, well, that could conceivably work.

StatsBomb Champions League Primer: Napoli vs Barcelona and Chelsea vs Bayern Munich

Two more Champions League games to play today, so let’s get right to it.

Napoli vs Barcelona

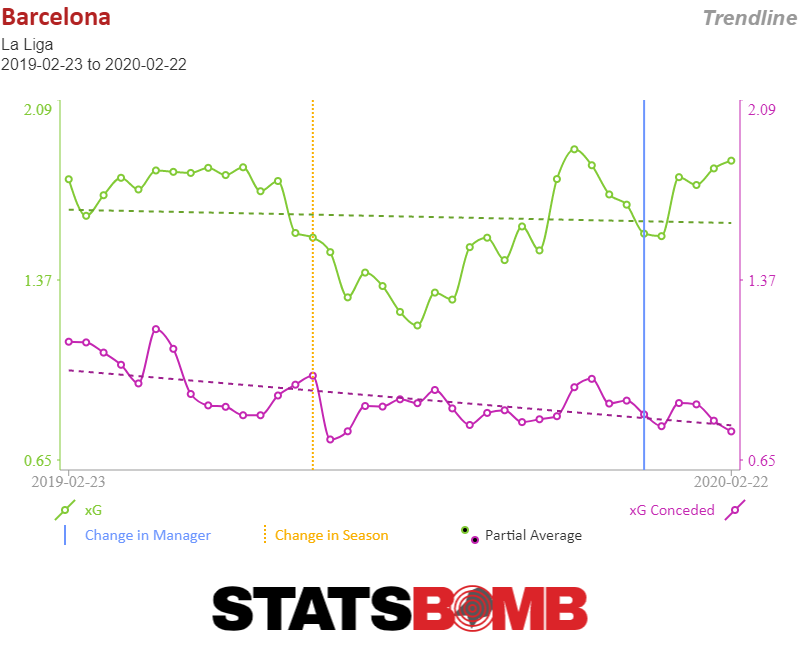

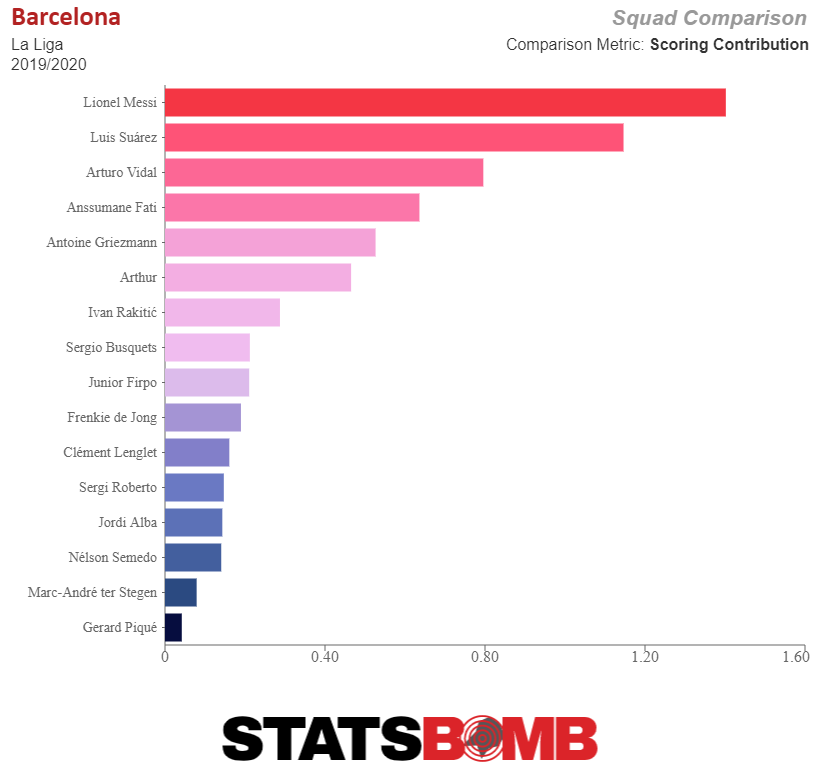

Not all struggles are created equal. Barcelona are having a difficult season. They’ve changed managers, their major attacking signing, Antoine Griezmann, has failed to settle, their attacking play looks staid and boring. Things just aren’t going nearly as well as they could be at Camp Nou. Yet they’re also leading La Liga with 55 points, two ahead of Real Madrid. They’ve got the best expected goal total per match in Spain at 1.68 and the third-best xG conceded total at 0.79. So, like, there’s bad for Barcelona, and there’s actual bad, and this season clearly falls into the first category, not the second. Barcelona are the ultimate rates and levels team. The level of their play has been so high for so long, because Lionel Messi is a supernatural artifact bestowed upon us by technologically advanced soccer-loving aliens, that any drop in form seems like the end of the world. But really, they’re still a very very good team. New manager Quique Setien has helped steady the ship. And while he’s brought a somewhat unadventurous possession style to the team, the side's attacking play immediately improved, without much in the way of increased defensive problems.  Barcelona’s main issue is still that everything runs through Messi. Five years ago their main problem was that everything ran through Messi, and the situation has only gotten more extreme since then. With Luis Suárez out, his combined goals and assists per 90 minutes are almost double anybody else’s on the team.

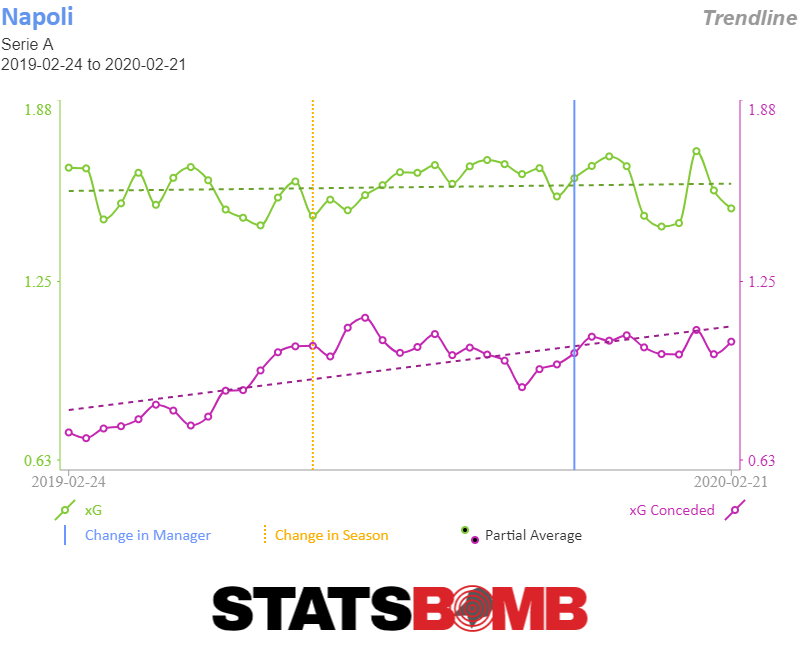

Barcelona’s main issue is still that everything runs through Messi. Five years ago their main problem was that everything ran through Messi, and the situation has only gotten more extreme since then. With Luis Suárez out, his combined goals and assists per 90 minutes are almost double anybody else’s on the team.  You’d be tempted to say it’s unsustainable, but, well, it’s Messi. Napoli’s situation is a little more complicated. On the one hand, they’re in sixth place with a goal difference of exactly four. That’s quite the drop for a team that spent years trailing only Juventus in Serie A. On the other hand, their xG difference of 0.55 is the fourth-best in the league and paints them in a considerably better light than their record and place in the table does. Put it all together and you have a Napoli team that is definitely worsening in comparison to seasons past, but not nearly as quickly as their drop down the table suggests. Specifically, from last year to this year the defense has eroded and they've gained little attacking input to compensate.

You’d be tempted to say it’s unsustainable, but, well, it’s Messi. Napoli’s situation is a little more complicated. On the one hand, they’re in sixth place with a goal difference of exactly four. That’s quite the drop for a team that spent years trailing only Juventus in Serie A. On the other hand, their xG difference of 0.55 is the fourth-best in the league and paints them in a considerably better light than their record and place in the table does. Put it all together and you have a Napoli team that is definitely worsening in comparison to seasons past, but not nearly as quickly as their drop down the table suggests. Specifically, from last year to this year the defense has eroded and they've gained little attacking input to compensate.  Nothing much has changed under new management. Carlo Ancelotti and his flexible 4-4-2 might have departed for Everton and been replaced by Gennaro Gattuso and a more traditional 4-3-3, but the basic contours of the problem remain exactly the same. Napoli are a pretty good side, but they aren’t as good as they used to be, and they certainly aren’t getting any better. Despite their struggles Barcelona are a significantly better side. When you’re a team that’s getting slowly worse it sure helps to have Lionel Messi.

Nothing much has changed under new management. Carlo Ancelotti and his flexible 4-4-2 might have departed for Everton and been replaced by Gennaro Gattuso and a more traditional 4-3-3, but the basic contours of the problem remain exactly the same. Napoli are a pretty good side, but they aren’t as good as they used to be, and they certainly aren’t getting any better. Despite their struggles Barcelona are a significantly better side. When you’re a team that’s getting slowly worse it sure helps to have Lionel Messi.

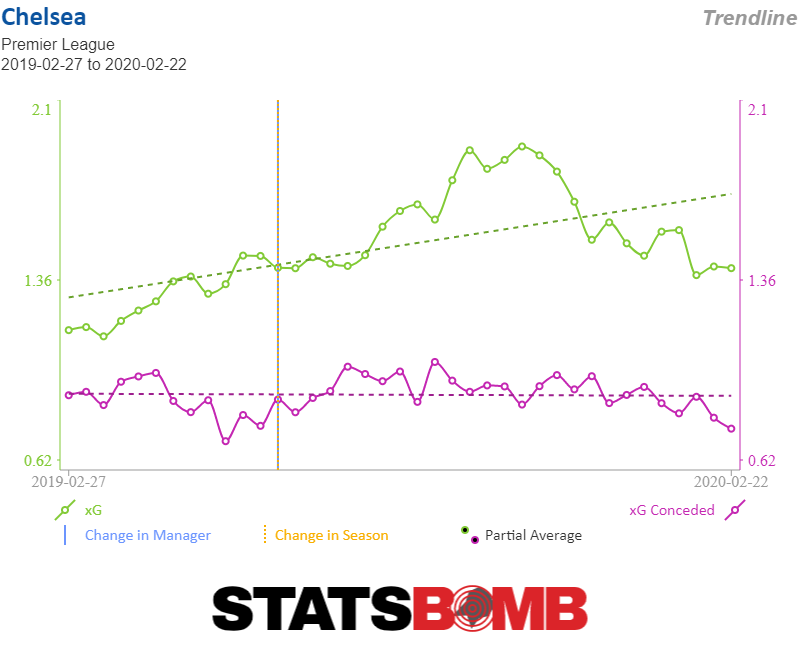

Chelsea v Bayern Munich

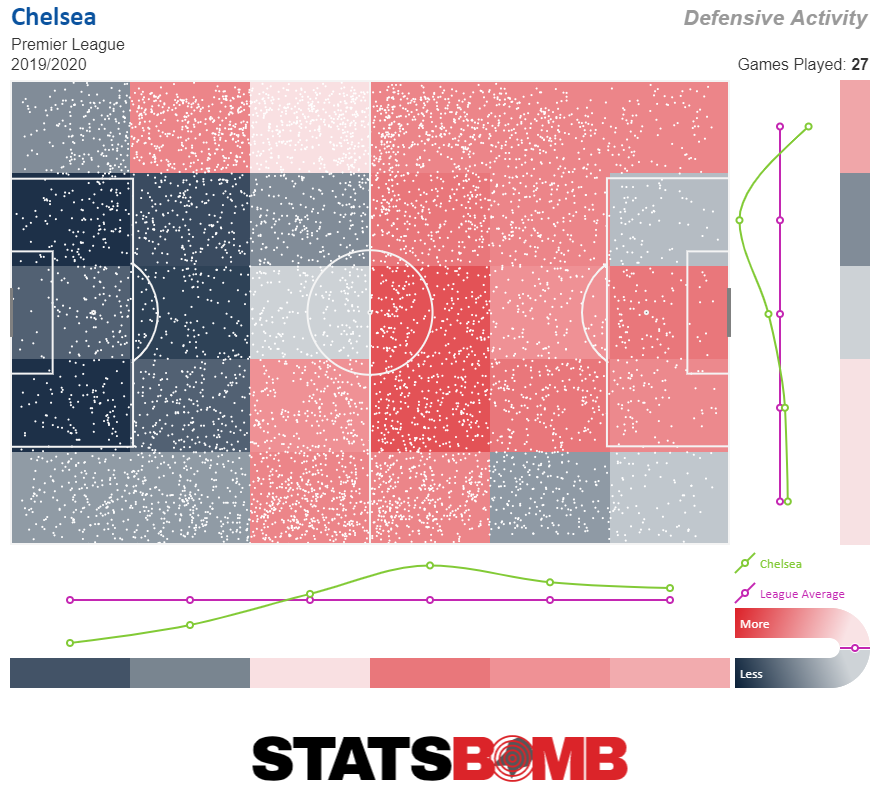

Two months ago a matchup between Chelsea and Bayern Munich might have looked like an opportunity for the English side to pull off a surprising upset. Bayern were in the midst of firing their manager while Chelsea were flying high off surprisingly strong performances from the youth movement who'd finally been given a chance. Then injuries hit Chelsea, Bayern righted the ship and now the task looks monumental for Frank Lampard’s men. Chelsea’s attack has tapered off dramatically. With Christian Pulisic out injured and Tammy Abraham injured, but not quite out, the side’s xG has really come back to earth since the turn of the year.  But, despite the attacking struggles, it’s really defensively where the Blues are likely to get exposed against Bayern. Chelsea are a very aggressive defensive side. They don’t know how to sit back and instead want to press from the front and defend in their opponent’s half. At their best they create opportunities for their attacking trio by winning the ball high up the pitch. At their worst they end up playing destabilized football, exposing themselves to opponents who are disciplined enough to hold the ball against them.

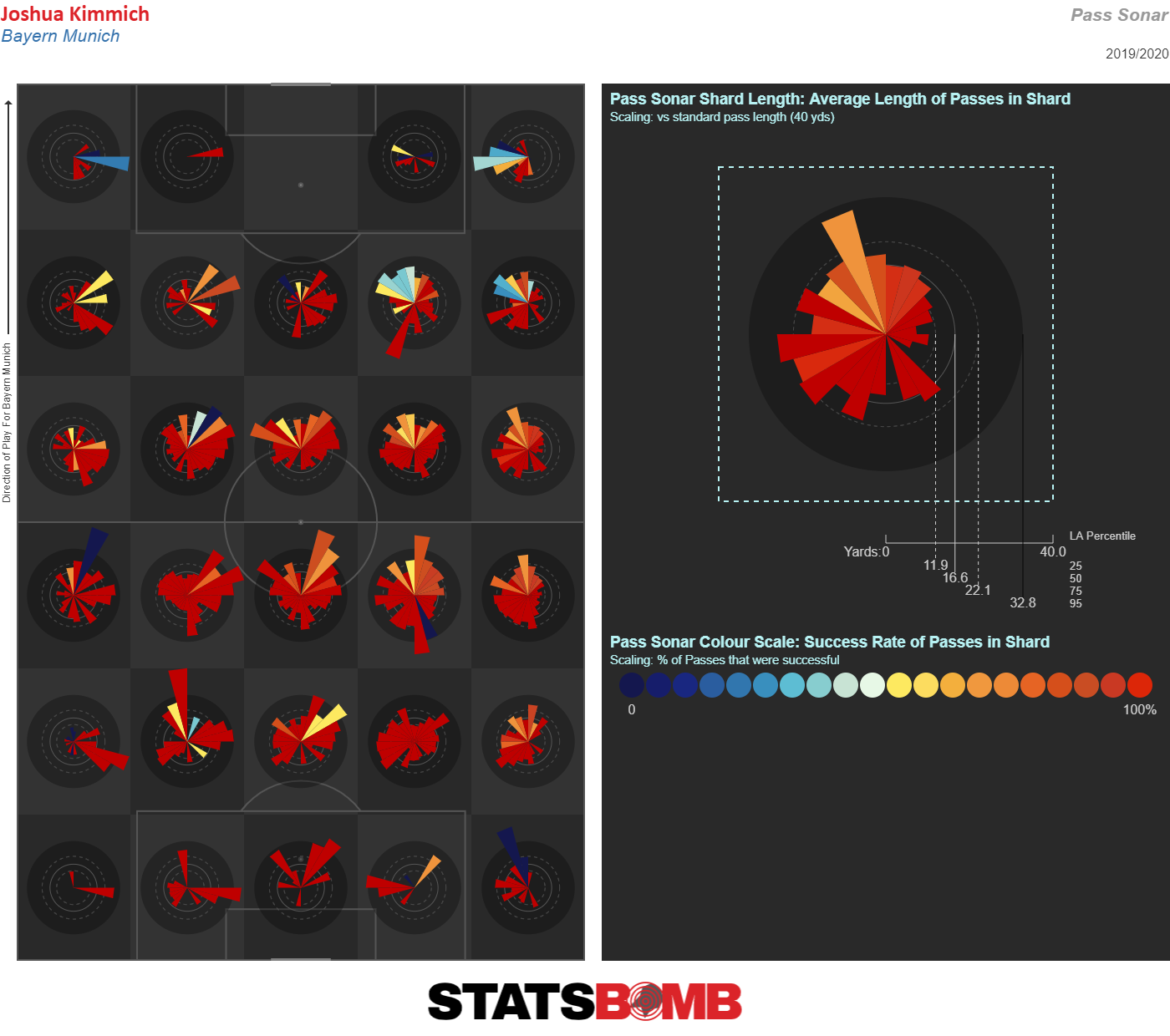

But, despite the attacking struggles, it’s really defensively where the Blues are likely to get exposed against Bayern. Chelsea are a very aggressive defensive side. They don’t know how to sit back and instead want to press from the front and defend in their opponent’s half. At their best they create opportunities for their attacking trio by winning the ball high up the pitch. At their worst they end up playing destabilized football, exposing themselves to opponents who are disciplined enough to hold the ball against them.  Bayern are clearly disciplined enough. The side's high-powered midfield often features Joshua Kimmich at the base, and he’s simply a machine at moving the ball up the field without losing possession.

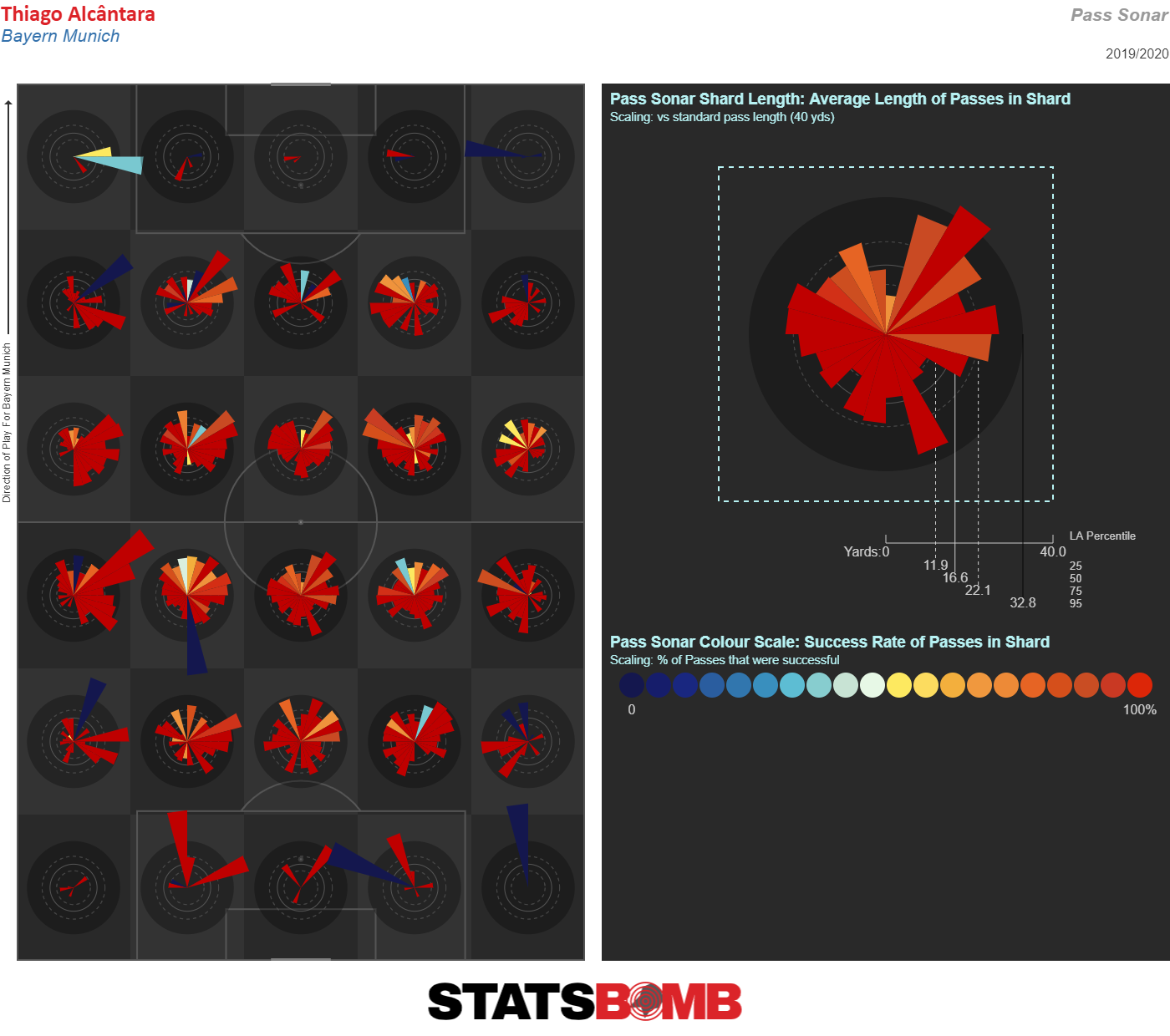

Bayern are clearly disciplined enough. The side's high-powered midfield often features Joshua Kimmich at the base, and he’s simply a machine at moving the ball up the field without losing possession.  The same is true of Thiago, who both advances the ball from deep and moves forward to help orchestrate the attack.

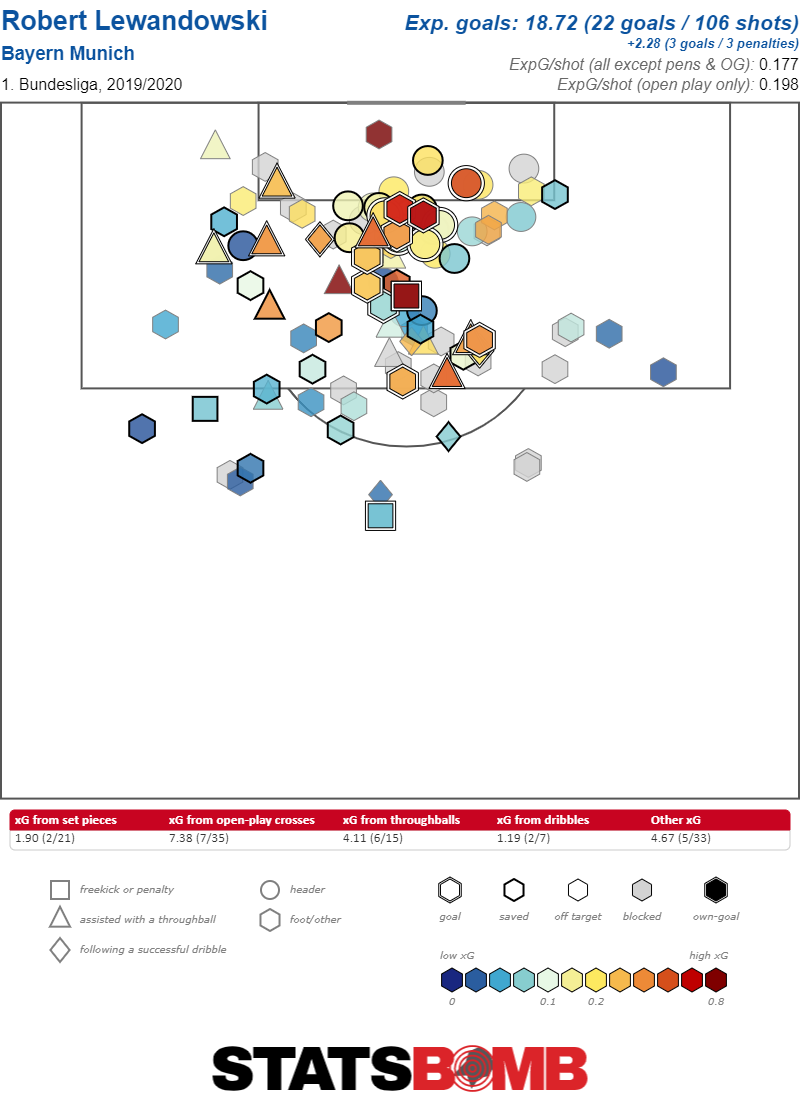

The same is true of Thiago, who both advances the ball from deep and moves forward to help orchestrate the attack.  It’s possible that a disciplined underdog might cause Bayern problems. Their attacking front line is great, and Robert Lewandowski continues to have an all-timer of a season, smashing goals from the best spots in the world.

It’s possible that a disciplined underdog might cause Bayern problems. Their attacking front line is great, and Robert Lewandowski continues to have an all-timer of a season, smashing goals from the best spots in the world.  But, maybe under the right circumstances, with a little bit of luck and a lot of deep defending an underdog could hold them and exploit the German giants on the counterattack. Chelsea under Lampard simply don’t have that club in their bag. In order to win they’re going to need Bayern’s midfield to crack under the pressure they apply. That seems exceedingly unlikely to happen.

But, maybe under the right circumstances, with a little bit of luck and a lot of deep defending an underdog could hold them and exploit the German giants on the counterattack. Chelsea under Lampard simply don’t have that club in their bag. In order to win they’re going to need Bayern’s midfield to crack under the pressure they apply. That seems exceedingly unlikely to happen.

StatsBomb Champions League Primer: Tottenham Hotspur vs RB Leipzig and Atalanta vs Valencia

The Champions League rolls on and so do our previews.

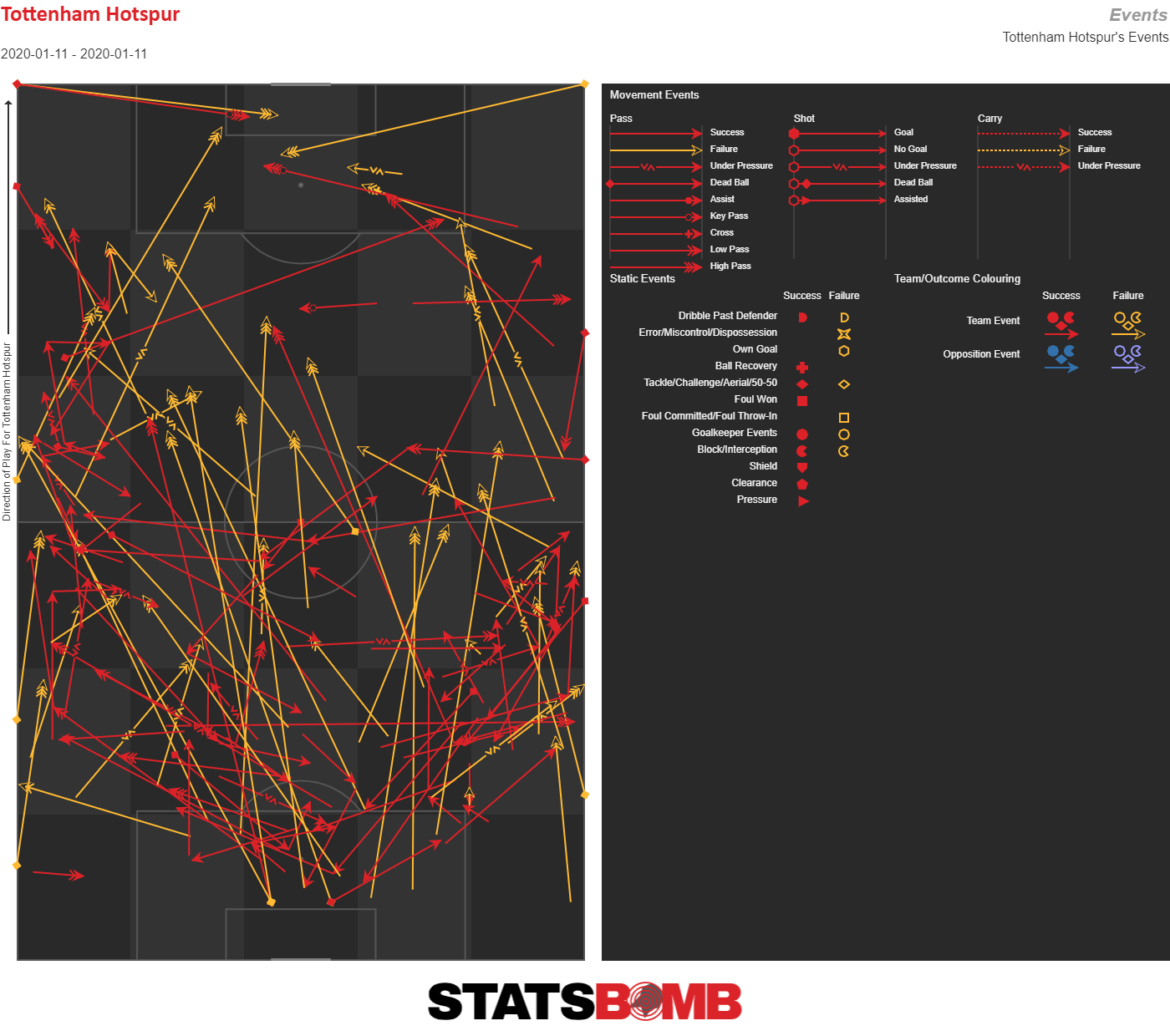

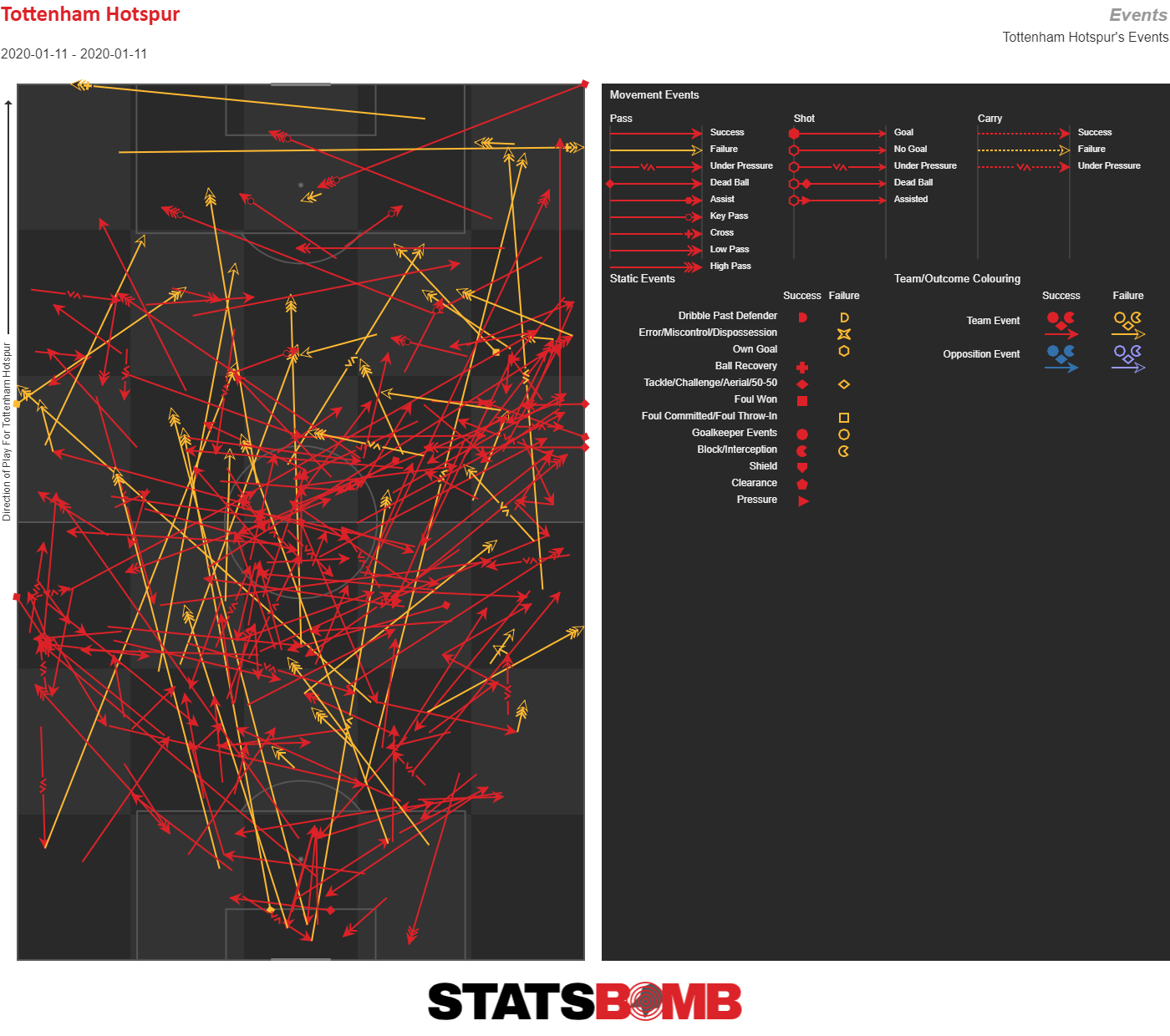

Tottenham Hotspur vs RB Leipzig

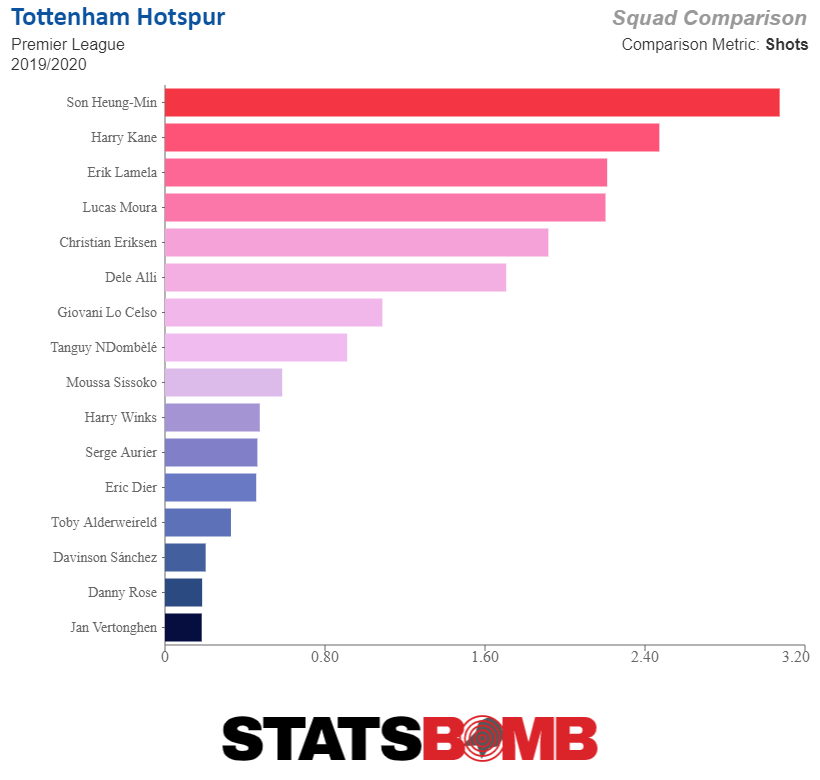

Spurs are running desperately low on shots. It’s not just Harry Kane, now Son Heung-min is also sidelined. Although José Mourinho might have some tricks up his sleeve, to us mortals his sleeve seems to hold only Lucas Moura, Dele Alli, Erik Lamela and Steven Bergwijn as natural front four players, though Ryan Sessegnon, Giovani Lo Celso or Tanguy Ndombele could theoretically be pushed up the field. Regardless, none of those players are particularly prolific shooters.  Lamela and Moura are both at the top of the list, though Lamela’s 2.21 shots per 90 minutes are from extremely limited minutes while Moura’s are simply not an impressive return for a player who has spent significant minutes functioning as a striker. Bergwijn hasn’t yet played 600 minutes for Spurs, so he doesn’t make the chart, but he was at 2.19 per 90 in the easier Eredivisie with PSV Eindhovern. It’s possible that Spurs will be ably to get by simply by spreading all the shots around, but that’s a pretty big ask against a very good RB Leipzig team. Of course, Mourinho has experience scuttling more talented teams in the Champions League. Perhaps the most relevant place to look for inspiration is the first year of his second stint with Chelsea. He reached the semifinals of the Champions League despite the fact that the only two true strikers at his disposal were a mostly washed out Samuel Eto’o and a mostly injured Fernando Torres. So, Spurs fans can take heart that stranger things have, in fact, happened. If Mourinho’s history is any guide, he will attempt to muddy up the game and nip a goal on the counter, first and foremost denying control of the midfield to Leipzig. If that fails, he'll hope his side will be able to absorb sustained pressure. For Leipzig this likely means they’ll have to find alternate avenues to get into dangerous positions. Luckily for them, they have Timo Werner.

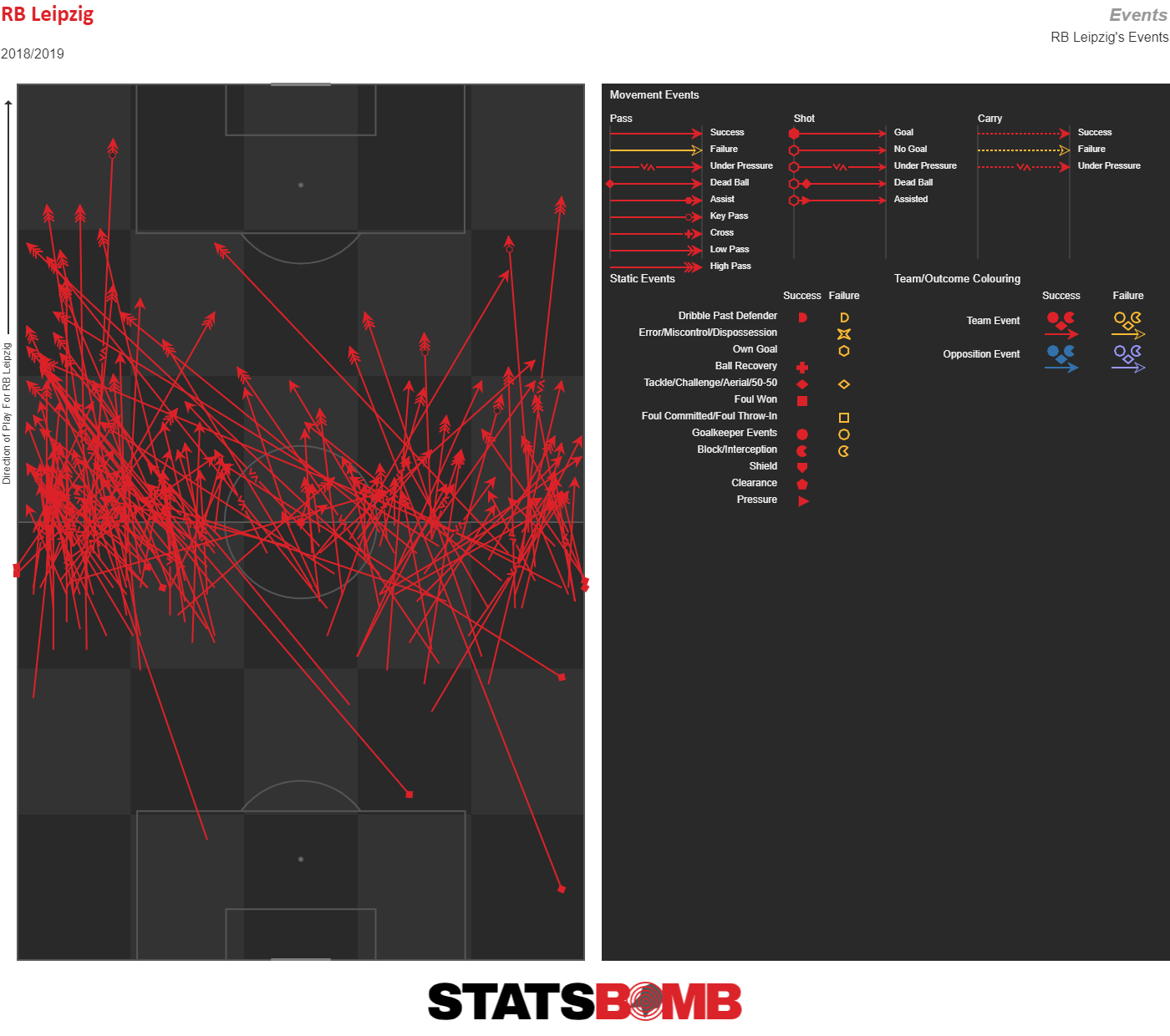

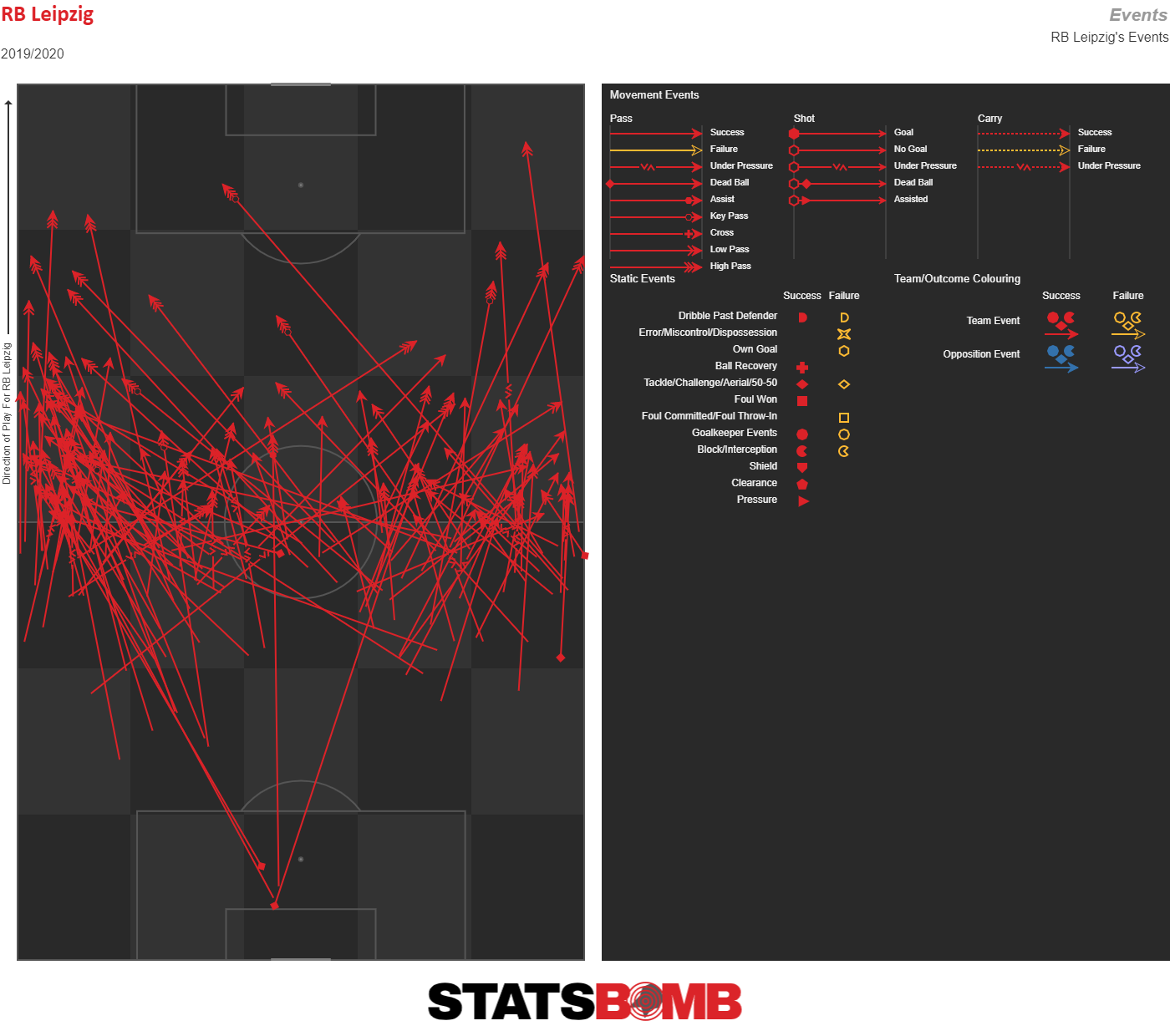

Lamela and Moura are both at the top of the list, though Lamela’s 2.21 shots per 90 minutes are from extremely limited minutes while Moura’s are simply not an impressive return for a player who has spent significant minutes functioning as a striker. Bergwijn hasn’t yet played 600 minutes for Spurs, so he doesn’t make the chart, but he was at 2.19 per 90 in the easier Eredivisie with PSV Eindhovern. It’s possible that Spurs will be ably to get by simply by spreading all the shots around, but that’s a pretty big ask against a very good RB Leipzig team. Of course, Mourinho has experience scuttling more talented teams in the Champions League. Perhaps the most relevant place to look for inspiration is the first year of his second stint with Chelsea. He reached the semifinals of the Champions League despite the fact that the only two true strikers at his disposal were a mostly washed out Samuel Eto’o and a mostly injured Fernando Torres. So, Spurs fans can take heart that stranger things have, in fact, happened. If Mourinho’s history is any guide, he will attempt to muddy up the game and nip a goal on the counter, first and foremost denying control of the midfield to Leipzig. If that fails, he'll hope his side will be able to absorb sustained pressure. For Leipzig this likely means they’ll have to find alternate avenues to get into dangerous positions. Luckily for them, they have Timo Werner.  It’s not just his obvious goal-scoring ability, but the fact that he’s equally superb at providing an outlet on the wings to receive the ball and turn and run in space. Here are all the successful passes played from Leipzig’s own half that Werner's received in the opposition half.

It’s not just his obvious goal-scoring ability, but the fact that he’s equally superb at providing an outlet on the wings to receive the ball and turn and run in space. Here are all the successful passes played from Leipzig’s own half that Werner's received in the opposition half.  Don’t be surprised if Spurs work hard to take away Leipzig’s ability to combine in midfield, forcing the German side to turn toward springing Werner over the top and in behind Spurs right back Serge Aurier. It’s nice when you can rely on a player who is both an expert goal scorer and an elite ball mover on the wing.

Don’t be surprised if Spurs work hard to take away Leipzig’s ability to combine in midfield, forcing the German side to turn toward springing Werner over the top and in behind Spurs right back Serge Aurier. It’s nice when you can rely on a player who is both an expert goal scorer and an elite ball mover on the wing.

Atalanta v Valencia

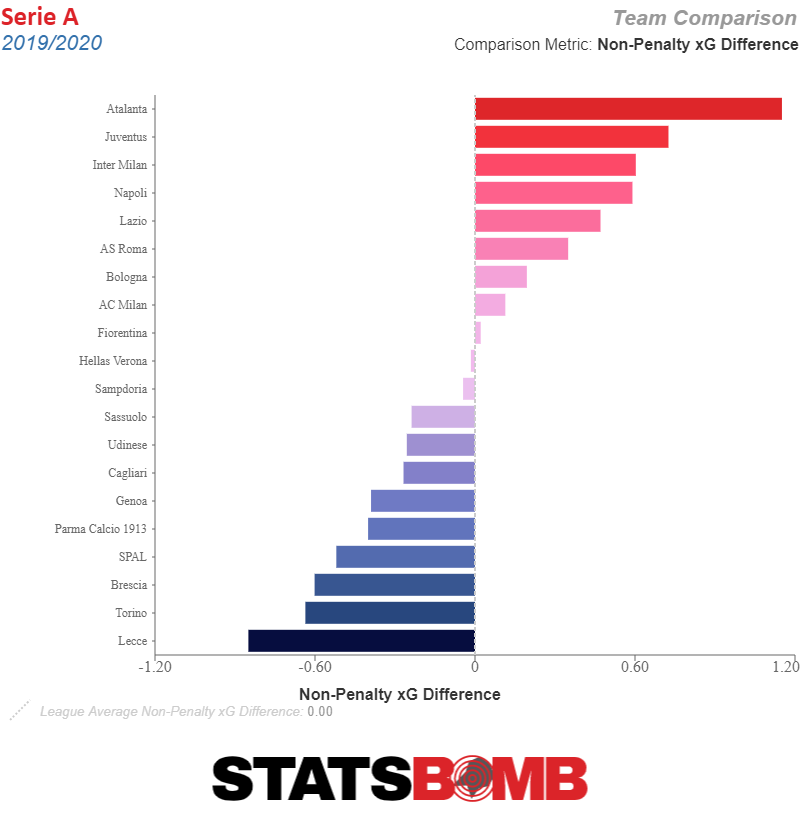

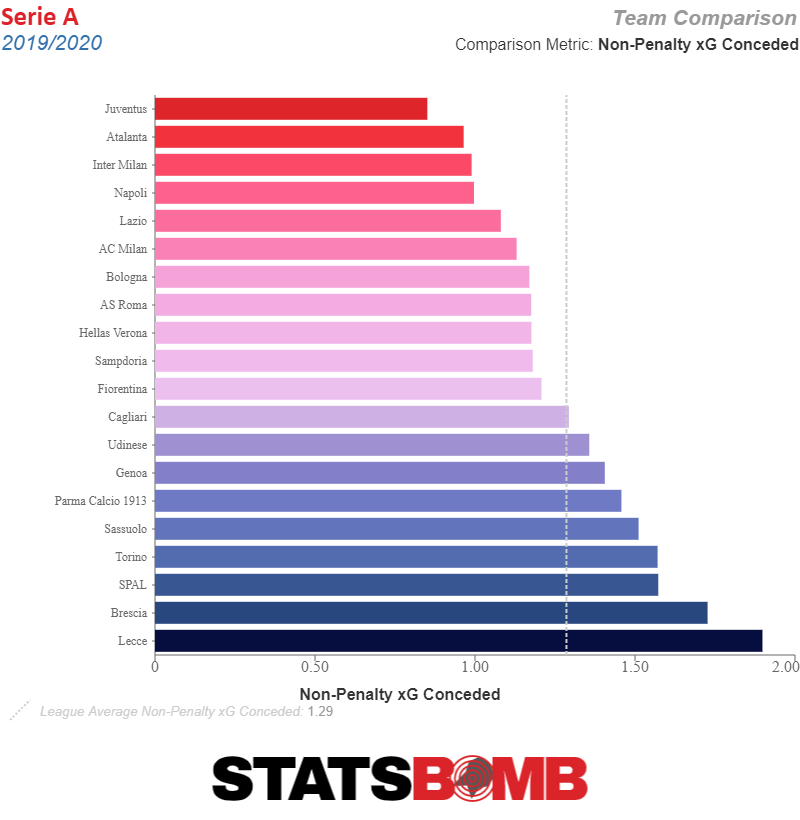

Valencia has a longer Champions League pedigree than Atalanta; they’ve been in the competition five times in the last decade (though they've only made it to the knockout rounds twice, and never past the first round). Meanwhile, this is Atalanta’s first trip down this long and treacherous road. That, however, fundamentally masks the nature of this matchup. This Atalanta team is simply much better than this Valencia side. In Serie A this season Atalanta sit comfortably in fourth. They might be significantly behind the top three, 12 points off first place Juventus and 9 behind third-place Inter Milan, but the side’s stats suggest they are good enough that in other years they’d be in contention for the Scudetto. In fact, Atalanta has by far the best non-penalty xG difference in Serie A.  Most impressively, Atalanta have added a strong defense to the attacking juggernaut that carried them to the upper reaches of the table over the past few seasons. Only Juventus have a stingier record when it comes to xG conceded.

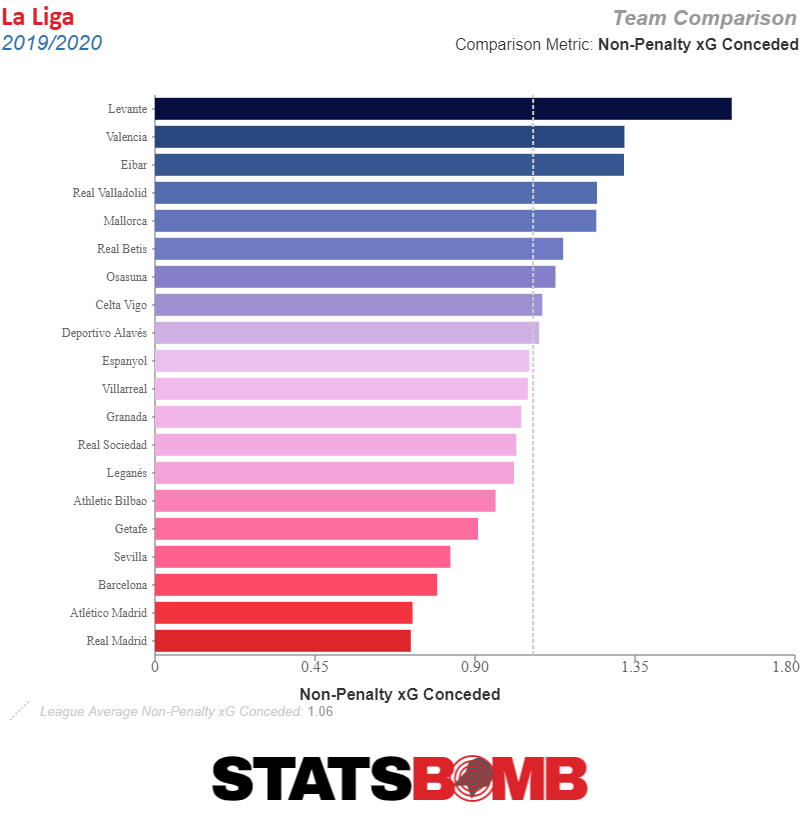

Most impressively, Atalanta have added a strong defense to the attacking juggernaut that carried them to the upper reaches of the table over the past few seasons. Only Juventus have a stingier record when it comes to xG conceded.  This isn’t the profile of a team that is just be happy to be here. Rather, Atalanta look prepared to dispatch a much weaker opponent as they gear up for stiffer challenges deeper in the tournament. In part, that’s because Valencia are simply not a good side at the moment. They sit seventh in La Liga, tied with Villarreal on 38 points, but the stats suggest that position strongly flatters them. They have one of the worst non-penalty xG differences in the league. The side’s attack is average, but on defense they are simply absolutely terrible, the second-worst team in La Liga in xG conceded.

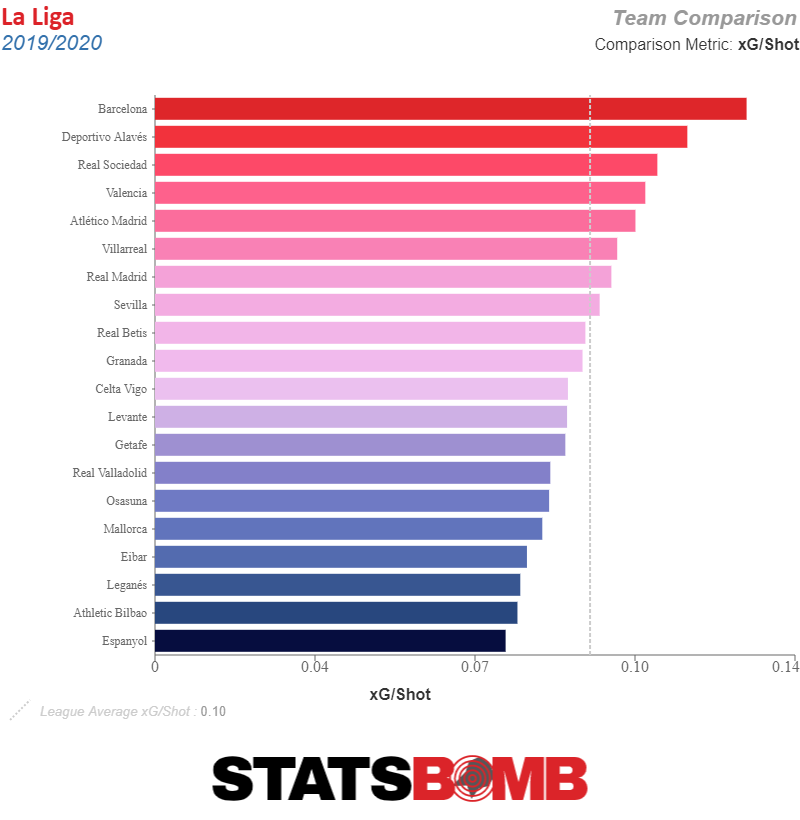

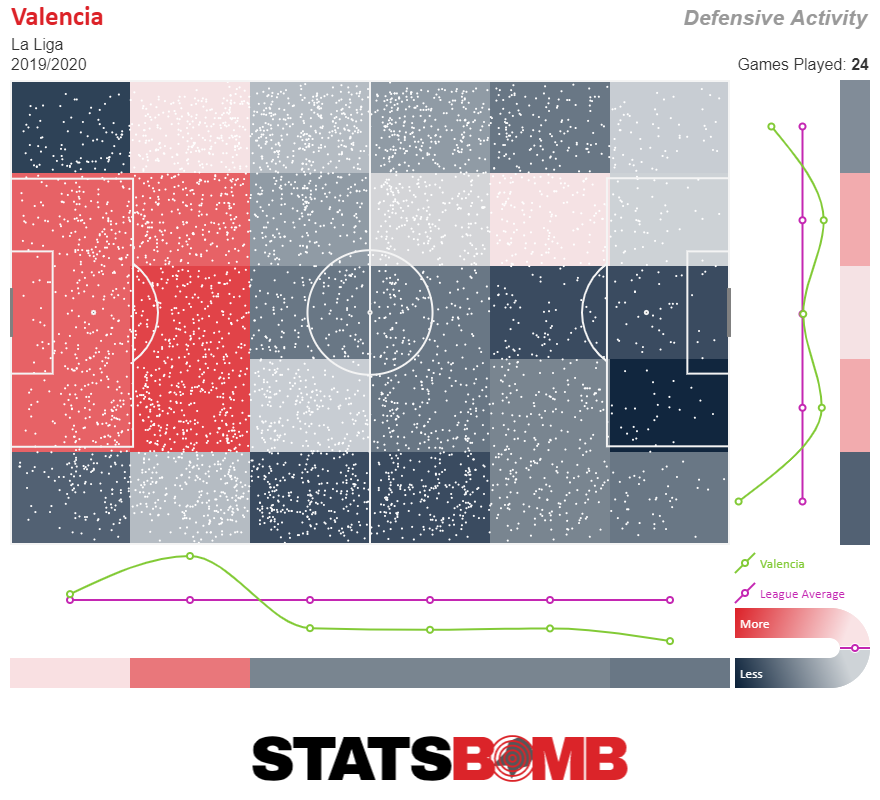

This isn’t the profile of a team that is just be happy to be here. Rather, Atalanta look prepared to dispatch a much weaker opponent as they gear up for stiffer challenges deeper in the tournament. In part, that’s because Valencia are simply not a good side at the moment. They sit seventh in La Liga, tied with Villarreal on 38 points, but the stats suggest that position strongly flatters them. They have one of the worst non-penalty xG differences in the league. The side’s attack is average, but on defense they are simply absolutely terrible, the second-worst team in La Liga in xG conceded.  This is, uh, not a sustainable defensive approach.

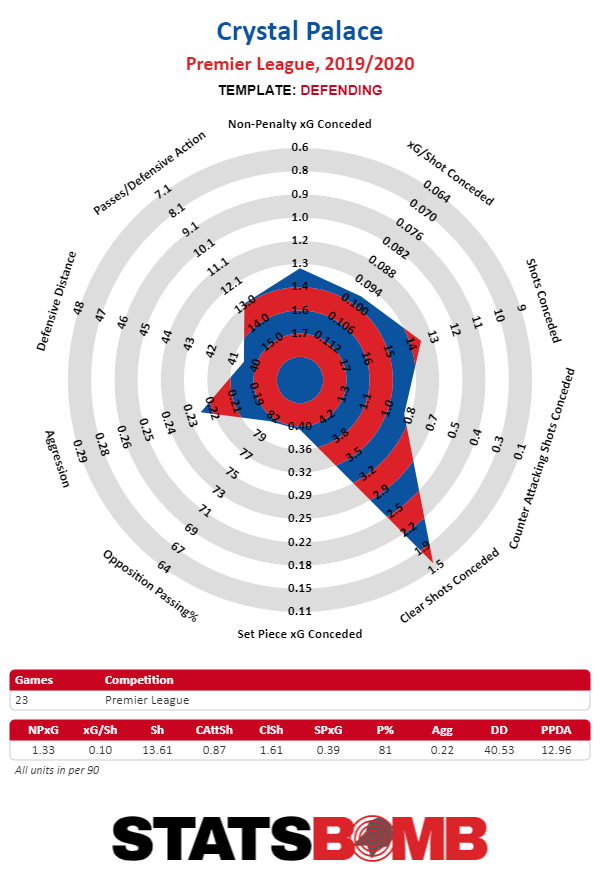

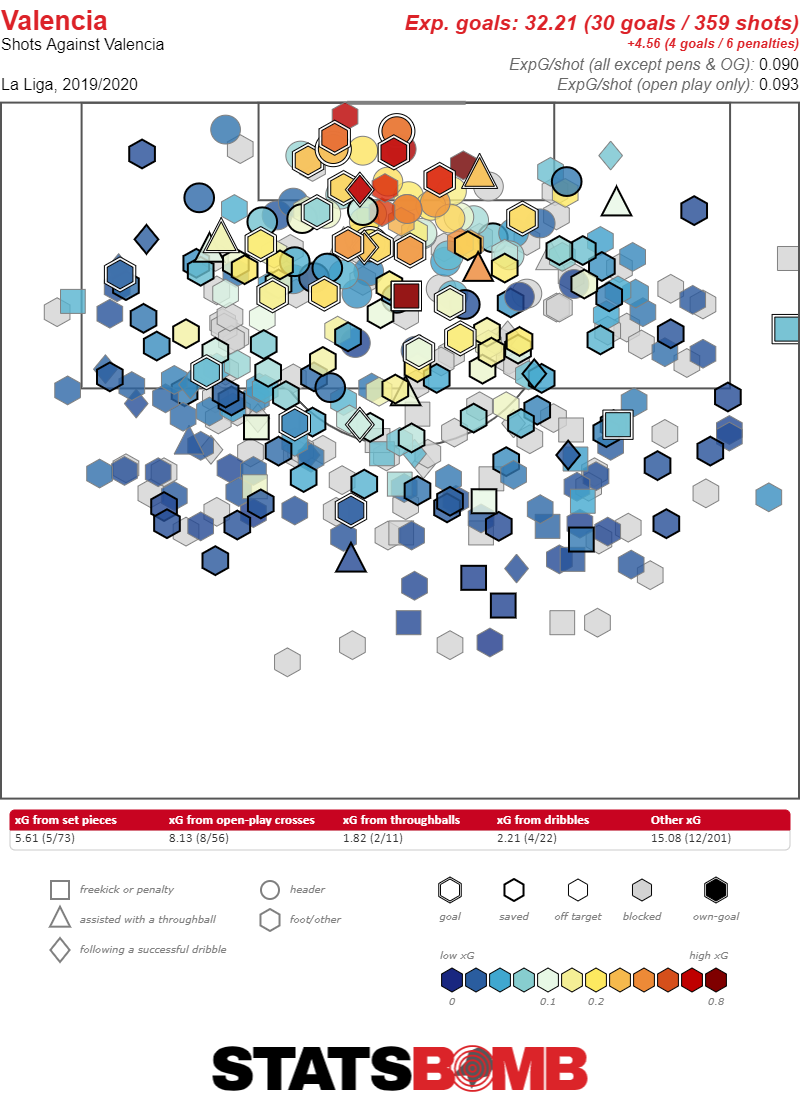

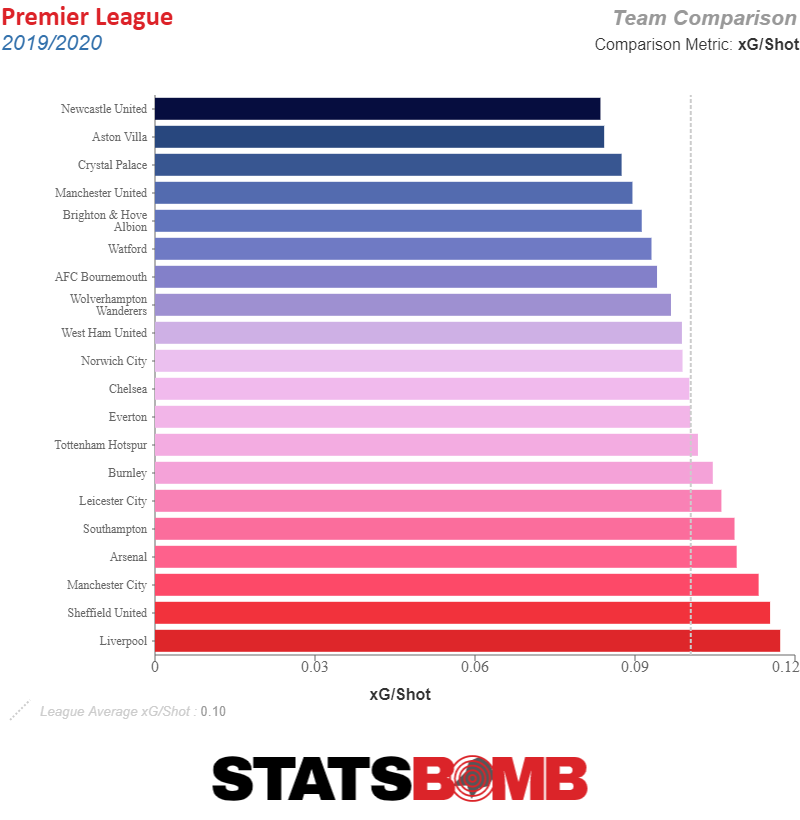

This is, uh, not a sustainable defensive approach.  Valencia take dropping deep and defending their own penalty area to extremes. They manage to not give up many truly dangerous shots, holding opponents to below 0.10 xG per shot on average.

Valencia take dropping deep and defending their own penalty area to extremes. They manage to not give up many truly dangerous shots, holding opponents to below 0.10 xG per shot on average.  However, they simply give up one too many attempts — even if those attempts are mediocre — conceding almost 15 shots a game on average, the second-most in La Liga. Giving an elite attacking side like Atalanta carte blanche to attack the penalty area is not likely going to end well for this Valencia team. Sports are awesome and unsure and no result is guaranteed, but what is overwhelmingly likely is that Atalanta are going to take the game to Valencia, and Valencia will have to hold on for dear life and hope for an unlikely chance to steal some points against the run of play.

However, they simply give up one too many attempts — even if those attempts are mediocre — conceding almost 15 shots a game on average, the second-most in La Liga. Giving an elite attacking side like Atalanta carte blanche to attack the penalty area is not likely going to end well for this Valencia team. Sports are awesome and unsure and no result is guaranteed, but what is overwhelmingly likely is that Atalanta are going to take the game to Valencia, and Valencia will have to hold on for dear life and hope for an unlikely chance to steal some points against the run of play.

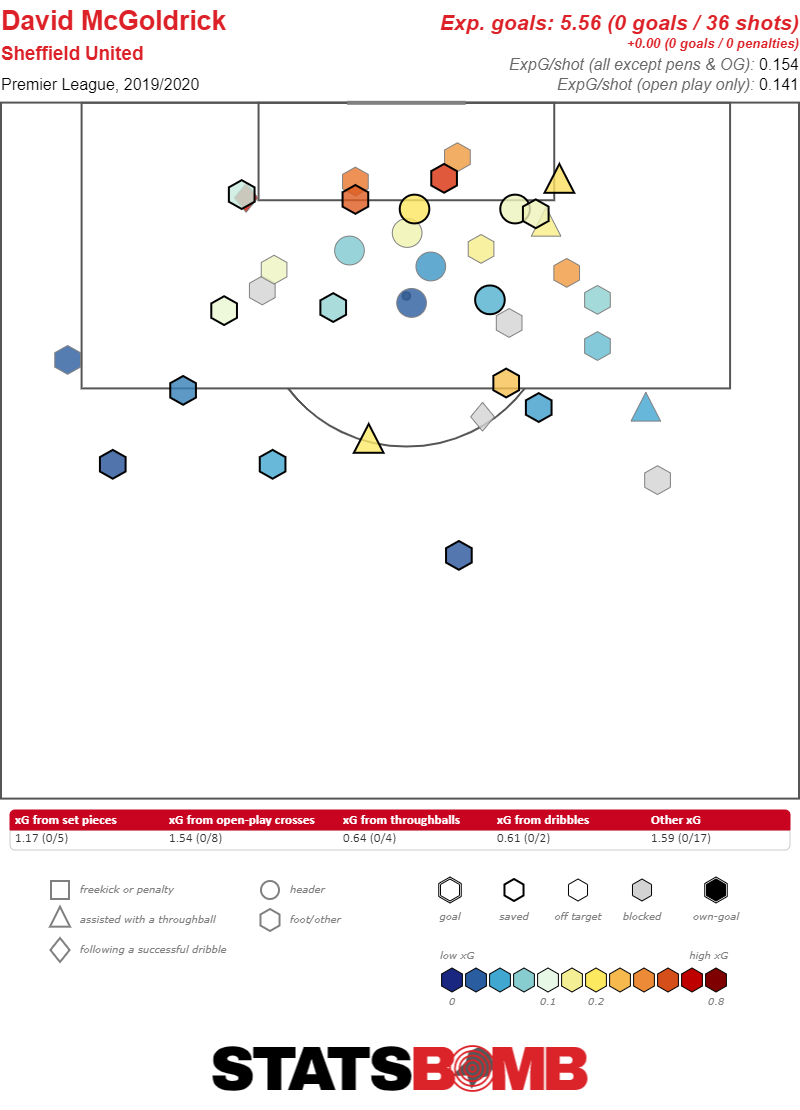

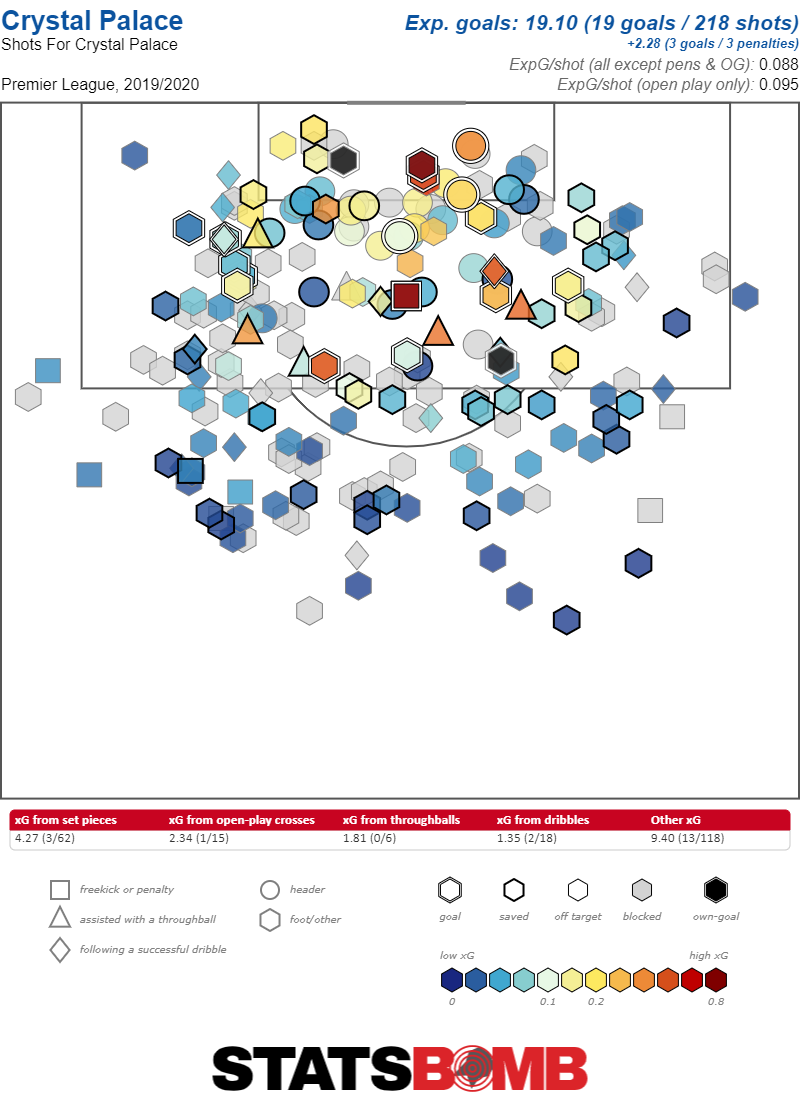

The shooting woes of Sheffield United's David McGoldrick, a StatsBomb investigation

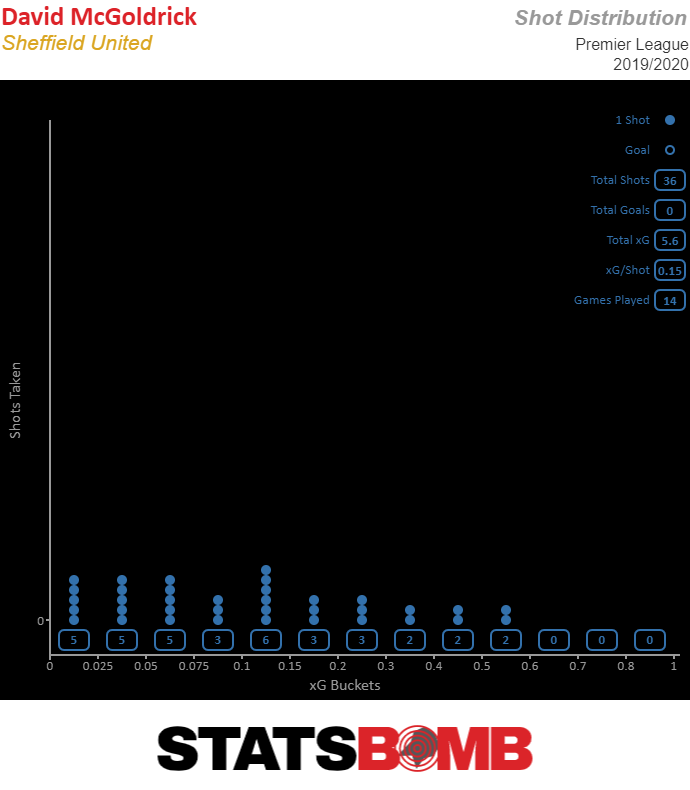

One of the most useful things an analyst can do with a statistic like expected goals is find good attacking players who aren’t yet showing up on the score sheet. Players that either take high-quality shots themselves, or create them for their teammates, see those opportunities turn into goals eventually. Then there’s poor David McGoldrick of Sheffield United. Nobody is further behind their expected goal contribution per 90 minutes, defined as combined expected goals and expected goals assisted, than McGoldrick (among players who have played more than 600 minutes). McGoldrick’s futility is even more impressive when you take into account that he has actually assisted more goals than xG predicts. The struggling striker has two assists while he has assisted shots worth 1.26 xG. So, the entirety of McGoldrick’s league-leading struggles at scoring come from shooting. It’s ugly. Couldn’t hit the broad side of a barn with a beachball ugly.  Sometimes, when a player is on a cold streak, it’s clear that the culprit is bad luck. Players that take a lot of long-range shots, for example, will often see dramatic swings in their performance against xG, pinging all around their expected level thanks to the nature of the shots they’re taking. A player who feasts on low percentage shots will occasionally see one go in, which boosts his performance against xG dramatically while also going long stretches missing all the hopeful punts he sends in the general direction of opposing keepers. That’s not happening here though. McGoldrick is actually quite savvy when it comes to shot selection. He averages 0.15 xG per shot, which is a fairly robust number. Among players who have taken more than 20 shots this season, he’s 17th in xG per shot. It’s clear from his shot distribution that he’s not piling on low expectation efforts from distance, he’s just getting lots of pretty good shots and missing every. single. one.

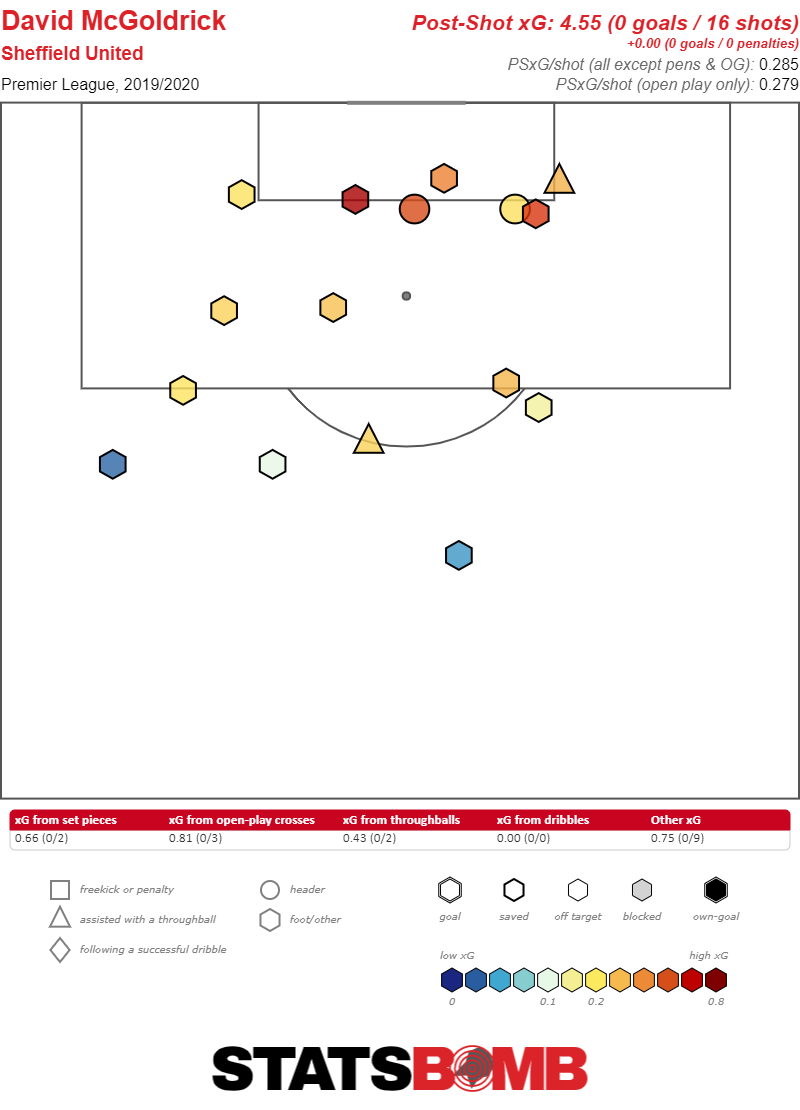

Sometimes, when a player is on a cold streak, it’s clear that the culprit is bad luck. Players that take a lot of long-range shots, for example, will often see dramatic swings in their performance against xG, pinging all around their expected level thanks to the nature of the shots they’re taking. A player who feasts on low percentage shots will occasionally see one go in, which boosts his performance against xG dramatically while also going long stretches missing all the hopeful punts he sends in the general direction of opposing keepers. That’s not happening here though. McGoldrick is actually quite savvy when it comes to shot selection. He averages 0.15 xG per shot, which is a fairly robust number. Among players who have taken more than 20 shots this season, he’s 17th in xG per shot. It’s clear from his shot distribution that he’s not piling on low expectation efforts from distance, he’s just getting lots of pretty good shots and missing every. single. one.  How exactly is McGoldrick managing to pull off this trick? Well, if we pry apart his shooting numbers we see some interesting stuff (still no goals though). How exactly is he missing? One thing that appears to be happening is that goalkeepers are playing absolutely out of their minds against him. The post-shot xG value of McGoldtrick’s shots is 4.55 from 16 on-target shots.

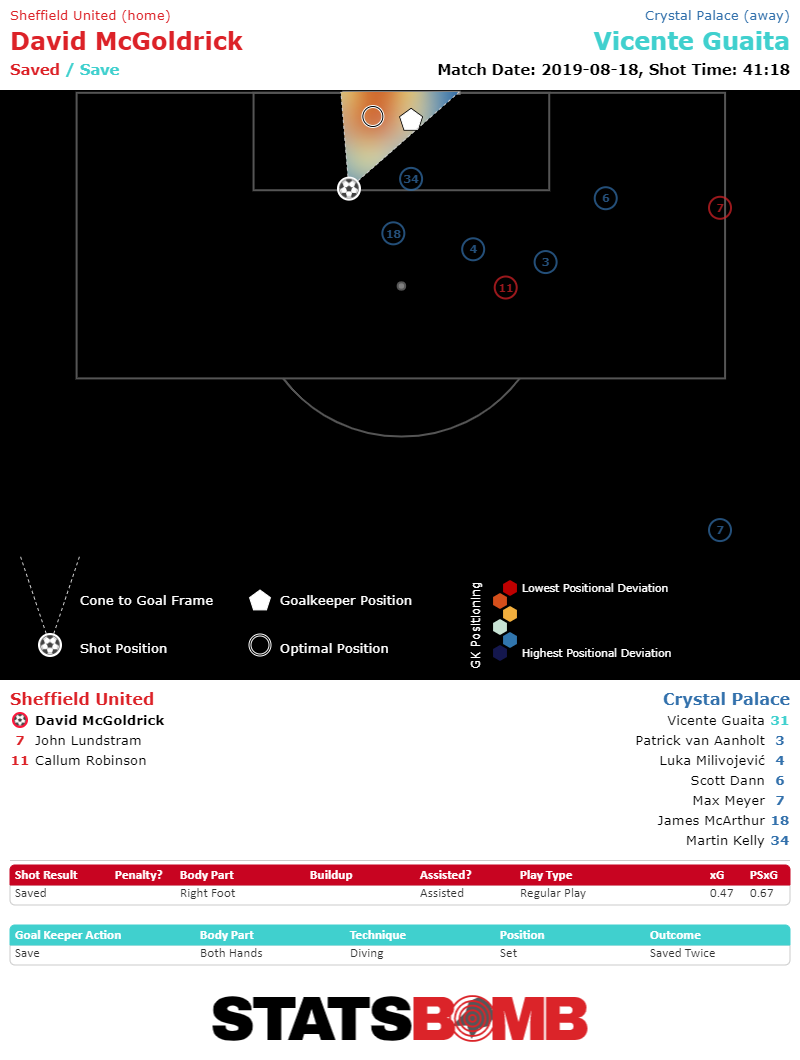

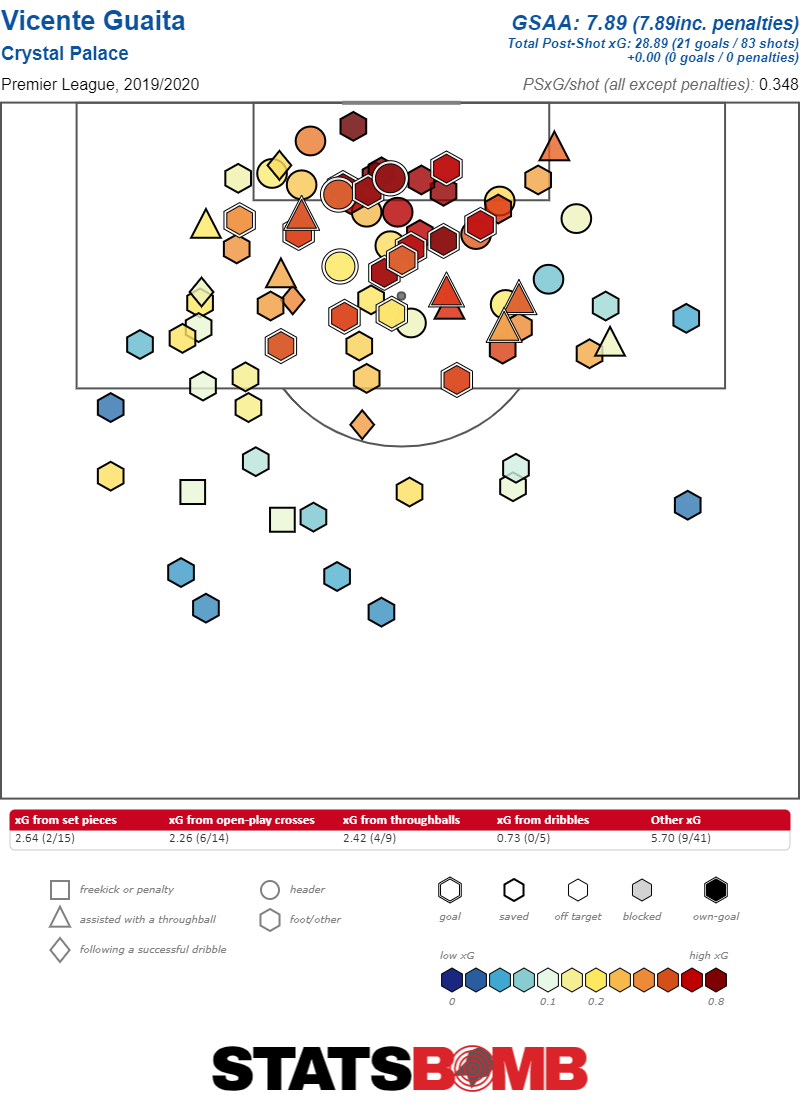

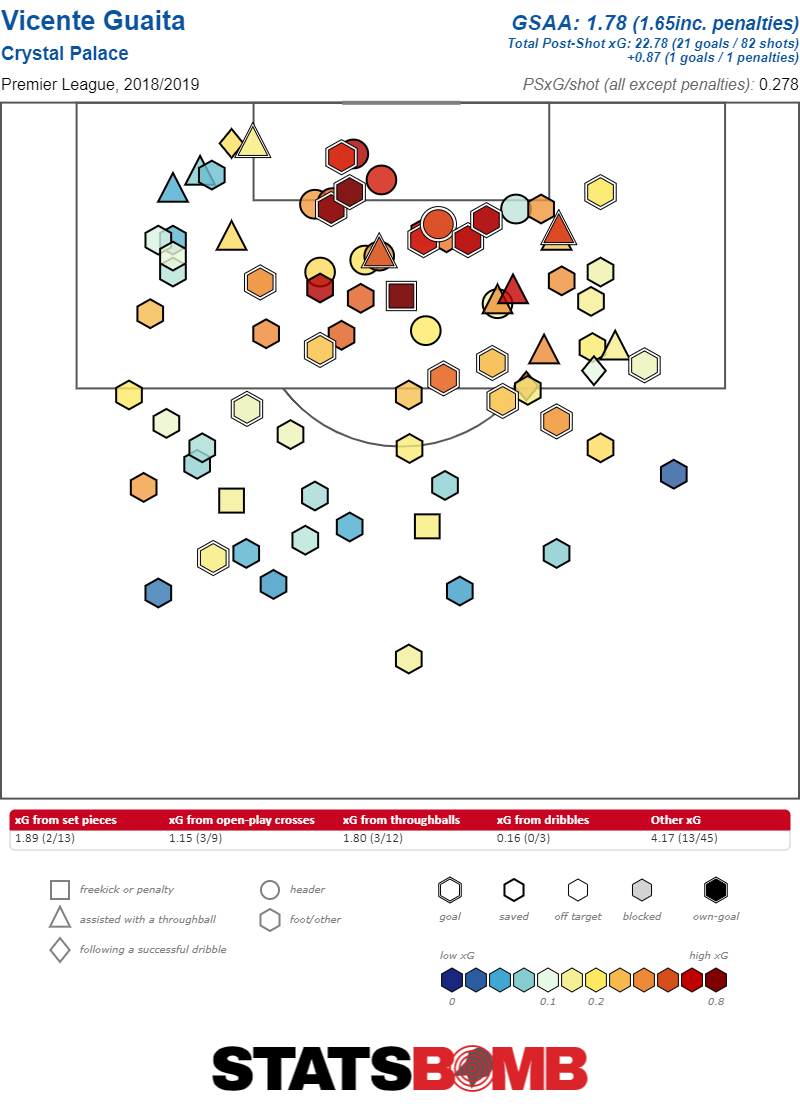

How exactly is McGoldrick managing to pull off this trick? Well, if we pry apart his shooting numbers we see some interesting stuff (still no goals though). How exactly is he missing? One thing that appears to be happening is that goalkeepers are playing absolutely out of their minds against him. The post-shot xG value of McGoldtrick’s shots is 4.55 from 16 on-target shots.  A brief nerdy stats note here. Post-shot xG doesn’t tell us very much that’s meaningful about the quality of McGoldrick’s shooting. A shot that fizzes just wide gets a value of zero and one that’s lollipopped softly into the keeper's arms will have a non-zero value, while the former may very well be a better attempt than the latter. So, the fact that the post-shot xG here is lower than regular xG doesn’t prove much about McGoldrick’s attempts. What it does show is that keepers seem to turn into gigantic multi-armed monsters against him, saving over four more shots than expected. When we get this granular, of course, there is always going to be some debate about who deserves credit for a great save, and who gets blamed for perhaps making the keeper's life easier than the numbers can detect. Those issues get averaged out with large numbers of shots, but when we’re looking at something like McGoldrick prodding a ball in the general direction of a gaping net, and Crystal Palace’s Vincente Guaita recovering to make a save, the question of sorting out exactly who gets credits and demerits for what remains an open one.

A brief nerdy stats note here. Post-shot xG doesn’t tell us very much that’s meaningful about the quality of McGoldrick’s shooting. A shot that fizzes just wide gets a value of zero and one that’s lollipopped softly into the keeper's arms will have a non-zero value, while the former may very well be a better attempt than the latter. So, the fact that the post-shot xG here is lower than regular xG doesn’t prove much about McGoldrick’s attempts. What it does show is that keepers seem to turn into gigantic multi-armed monsters against him, saving over four more shots than expected. When we get this granular, of course, there is always going to be some debate about who deserves credit for a great save, and who gets blamed for perhaps making the keeper's life easier than the numbers can detect. Those issues get averaged out with large numbers of shots, but when we’re looking at something like McGoldrick prodding a ball in the general direction of a gaping net, and Crystal Palace’s Vincente Guaita recovering to make a save, the question of sorting out exactly who gets credits and demerits for what remains an open one.  Individual shots get missed all the time, for all sorts of reasons. It’s just that McGoldrick has missed so darn many of them this season. Four separate times he’s managed to kick the ball towards goal from inside the six-yard box, only to see two of them get saved, and two of them miss the target entirely. The good news for McGoldrick is that he’s almost certainly getting unlucky. Whenever something this unlikely happens, it’s at least partially down to dumb luck. The problem for him is that it’s also probably not just luck. McGoldrick is 32 years old. He’s played his entire career in the lower divisions of English football and never been a consistent goal scorer. While he scored 12 non-penalty goals last season from 15.20 xG (and an additional three penalties), he has not had a prolific goal-scoring career. Before last season he had only reached double digits in goals three times, in 2013–14 with 14 goals for Ipswich Town in the Championship, 2012–13 with 16 goals for Coventry City in League One, and way back in 2008–09 with Southampton in the Championship. All things being equal, we expect players to eventually perform to the xG. But, sometimes everything else is not equal. McGoldrick is a longtime journeyman of a striker. Suddenly at age 32, he finds himself playing at the highest level of his career. He plays for an extraordinarily well-coached team in Sheffield United, one that is exceptional at working together to create great shots. McGoldrick keeps missing those great shots. The simplest explanation is not that McGoldrick is facing exceptionally, historically bad luck (although we shouldn’t rule that possibility out entirely) but rather that he’s a player who just isn’t quite good enough for this level. Sheffield United manager Chris Wilder excels at getting the most out of his squad. That includes finding an aging striker with a preternatural instinct for getting on the end of his team’s highly choreographed creative attacking moves to create really good chances. When you’re Wilder and Sheffield United, however, you’re also shopping in the bargain bin, and that means perhaps the player you’ve found to do that just isn’t quite up to snuff when it comes to actually putting the ball into the back of the net. So, the bad news is that McGoldrick’s finishing struggles might not just be bad luck. The good news is that Sheffield United are succeeding this season anyway. The really good news is that this means there’s room for them to become even better. Just imagine what this team might do if one of their strikers wasn’t chronically unable to finish.

Individual shots get missed all the time, for all sorts of reasons. It’s just that McGoldrick has missed so darn many of them this season. Four separate times he’s managed to kick the ball towards goal from inside the six-yard box, only to see two of them get saved, and two of them miss the target entirely. The good news for McGoldrick is that he’s almost certainly getting unlucky. Whenever something this unlikely happens, it’s at least partially down to dumb luck. The problem for him is that it’s also probably not just luck. McGoldrick is 32 years old. He’s played his entire career in the lower divisions of English football and never been a consistent goal scorer. While he scored 12 non-penalty goals last season from 15.20 xG (and an additional three penalties), he has not had a prolific goal-scoring career. Before last season he had only reached double digits in goals three times, in 2013–14 with 14 goals for Ipswich Town in the Championship, 2012–13 with 16 goals for Coventry City in League One, and way back in 2008–09 with Southampton in the Championship. All things being equal, we expect players to eventually perform to the xG. But, sometimes everything else is not equal. McGoldrick is a longtime journeyman of a striker. Suddenly at age 32, he finds himself playing at the highest level of his career. He plays for an extraordinarily well-coached team in Sheffield United, one that is exceptional at working together to create great shots. McGoldrick keeps missing those great shots. The simplest explanation is not that McGoldrick is facing exceptionally, historically bad luck (although we shouldn’t rule that possibility out entirely) but rather that he’s a player who just isn’t quite good enough for this level. Sheffield United manager Chris Wilder excels at getting the most out of his squad. That includes finding an aging striker with a preternatural instinct for getting on the end of his team’s highly choreographed creative attacking moves to create really good chances. When you’re Wilder and Sheffield United, however, you’re also shopping in the bargain bin, and that means perhaps the player you’ve found to do that just isn’t quite up to snuff when it comes to actually putting the ball into the back of the net. So, the bad news is that McGoldrick’s finishing struggles might not just be bad luck. The good news is that Sheffield United are succeeding this season anyway. The really good news is that this means there’s room for them to become even better. Just imagine what this team might do if one of their strikers wasn’t chronically unable to finish.

The Premier League has a golden generation of young talent

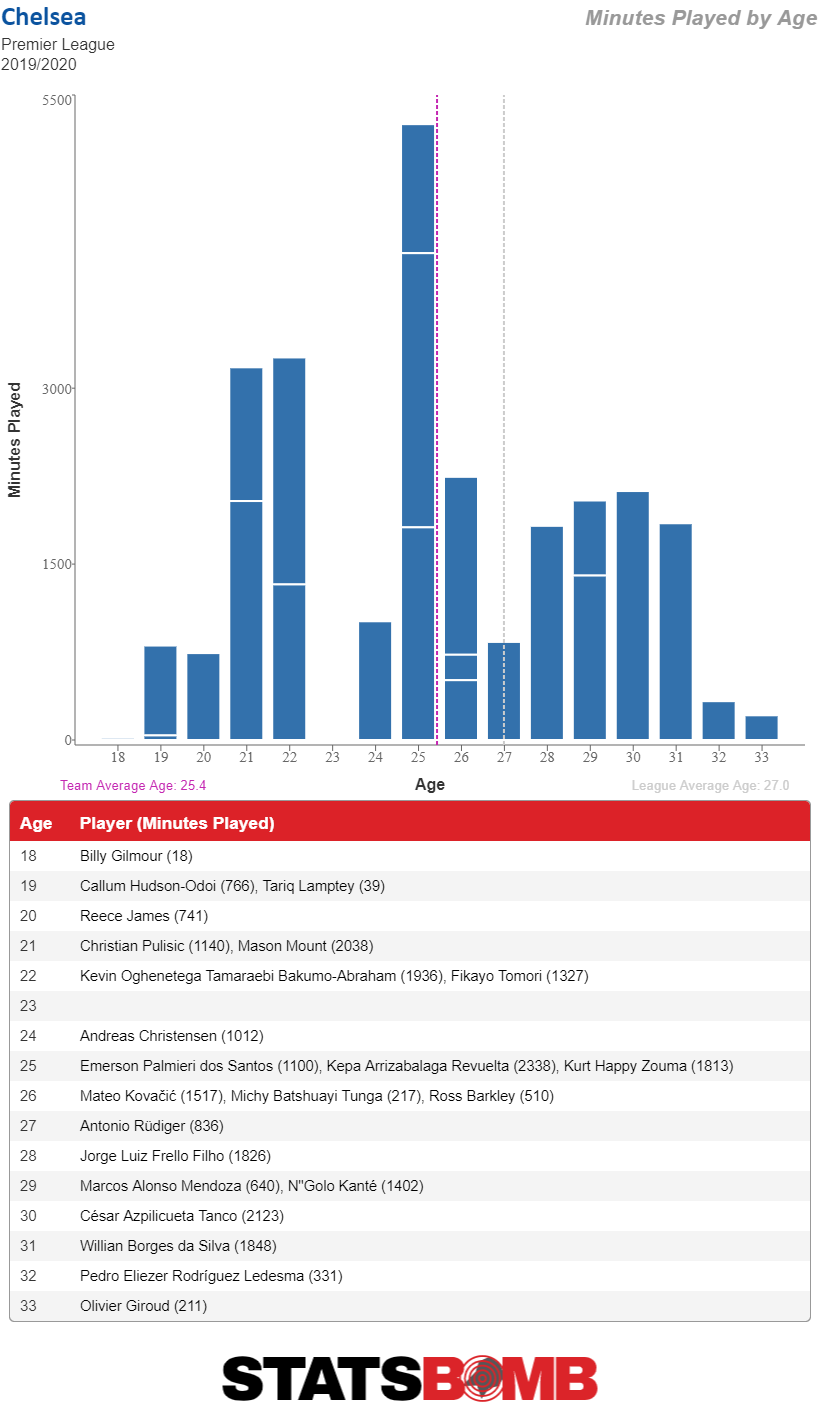

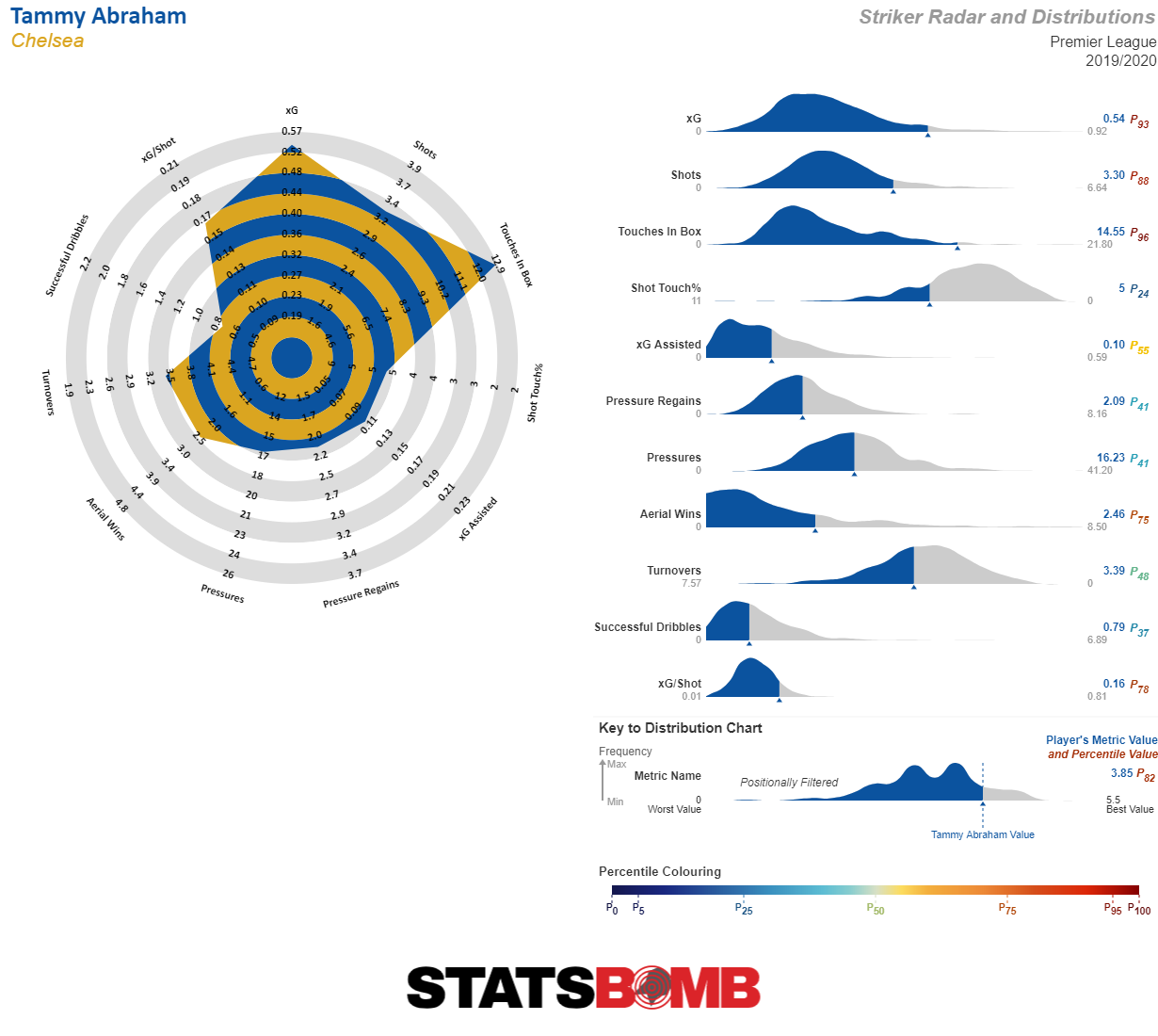

The Premier League is currently enjoying a golden era of young attacking talent. Up and down the table, on teams large and small, young players are staking their claims as some of the brightest stars in England. A unique confluence of circumstances has led to teams of all stripes giving the kids a chance, and those kids are performing. This season there are a whopping nine players aged 22 or younger who have played 600 minutes (a filter used for all stats in the piece) and average over 0.40 combined expected goals and expected assists. Relax the criteria to 0.30 combined xG and xG assisted and that number springs to 17. Last season, there were only 4 players over 0.40 combined and 12 with over 0.30. Two seasons ago those numbers stood at 7 and 11. So, what exactly is going on in the Premier League this season? One major factor in the young success bump is that Chelsea and Manchester United, for different reasons, handed the keys over to young stars in the attack. Chelsea sold Eden Hazard and bought Christian Pulisic, but also accepted a transfer ban, instead opting to rely on Pulisic, Tammy Abraham, Callum Hudson-Odoi and Mason Mount. All four of those players have cleared the 0.30 threshold, and all but Mount are over 0.40. Chelsea took a good squad, rolled the dice on playing the kids and were richly rewarded.  Abraham in particular has turned into one of the best pure strikers in the league. He’s fourth in the Premier League in xG per 90 with 0.54, thanks to a classic striker mix of taking a lot of shots (his 3.30 is fifth in the league) and keeping those shots high quality. Of the 20 highest volume shooters in the league, only Danny Ings of Southampton and Gabriel Jesus at Manchester City have a better xG per shot than Abraham’s 0.16. He’s just really really good.

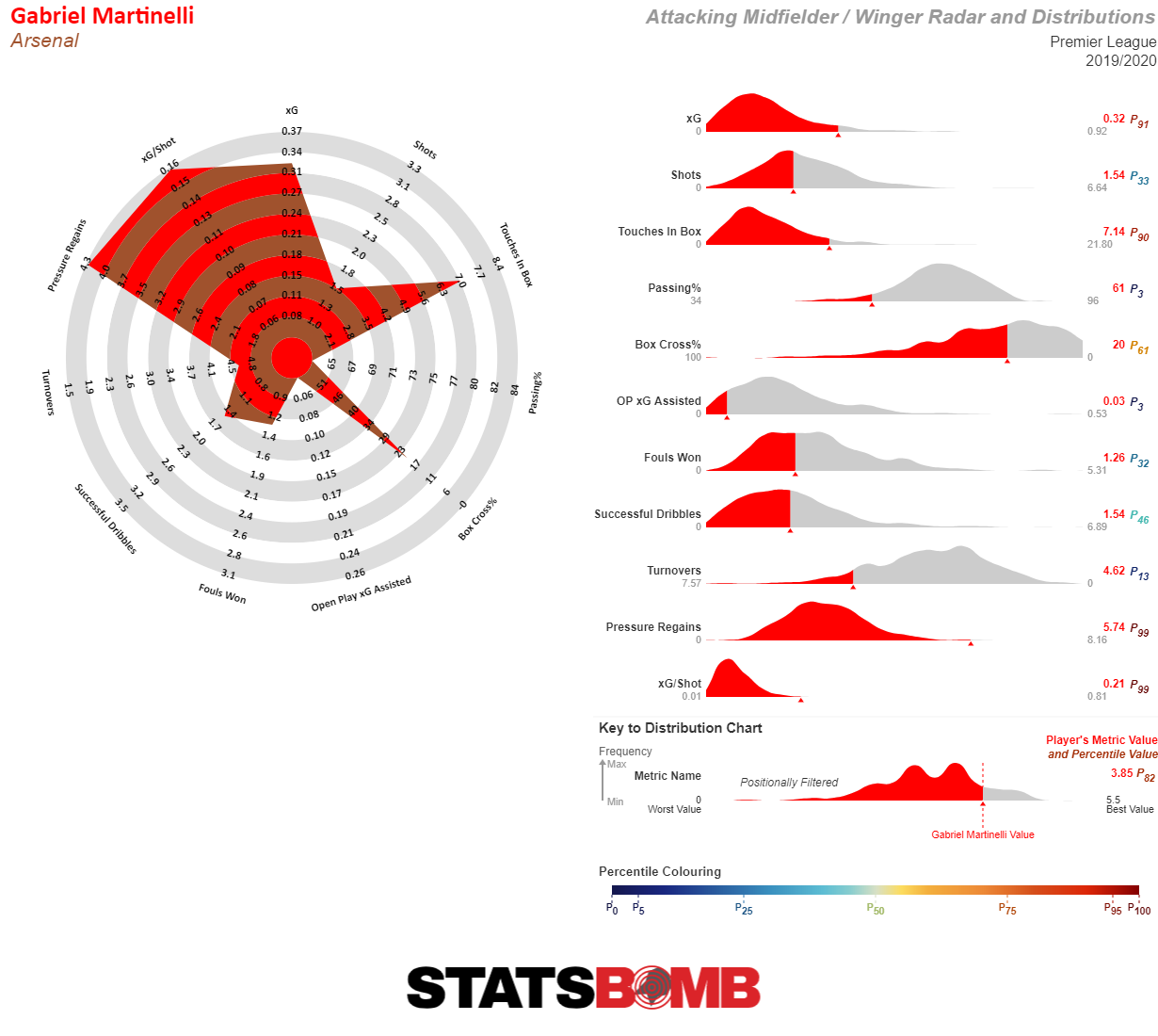

Abraham in particular has turned into one of the best pure strikers in the league. He’s fourth in the Premier League in xG per 90 with 0.54, thanks to a classic striker mix of taking a lot of shots (his 3.30 is fifth in the league) and keeping those shots high quality. Of the 20 highest volume shooters in the league, only Danny Ings of Southampton and Gabriel Jesus at Manchester City have a better xG per shot than Abraham’s 0.16. He’s just really really good.  Manchester United and Arsenal are similarly undergoing their own forms of youth movements, although for reasons somewhat less clear than Chelsea’s transfer ban. United spent large on defenders last summer, bringing in Harry Maguire and Aaron Wan-Bissaka while letting go of Romelu Lukaku and Alexis Sánchez (though, granted, the two are at very different points in their careers and have had very different fates at Inter Milan). Of their young players, only Marcus Rashford makes the 0.30 cutoff, with a 0.49 combined xG and xG assisted a respectable fourth among the kids, behind only Gabriel Jesus, Abraham, a surprise player who we’ll get to in a second, and Pulisic. Daniel James just about sneaks on at the very end of this list at 0.31 combined stats. It’s also worth noting that Mason Greenwood just misses the minutes cutoff, or else he would join James at 0.31, so if he continues to produce in the minutes he’s given expect him on the list if it's revisited at the end of the season. For Arsenal, it’s Gabriel Martinelli who appears on the list although he barely makes the minutes cut. Still, at only 18 years old, his 0.35 combined numbers are a bright sign, placing him eighth on the list. It’s also understandable that Arsenal, despite playing their kids, have just one player on this list and it's an attacker with limited minutes. They do still have Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang, Alexandre Lacazette and Mesut Özil on the books after all. Most of their kids are, to one degree or another, midfielders.

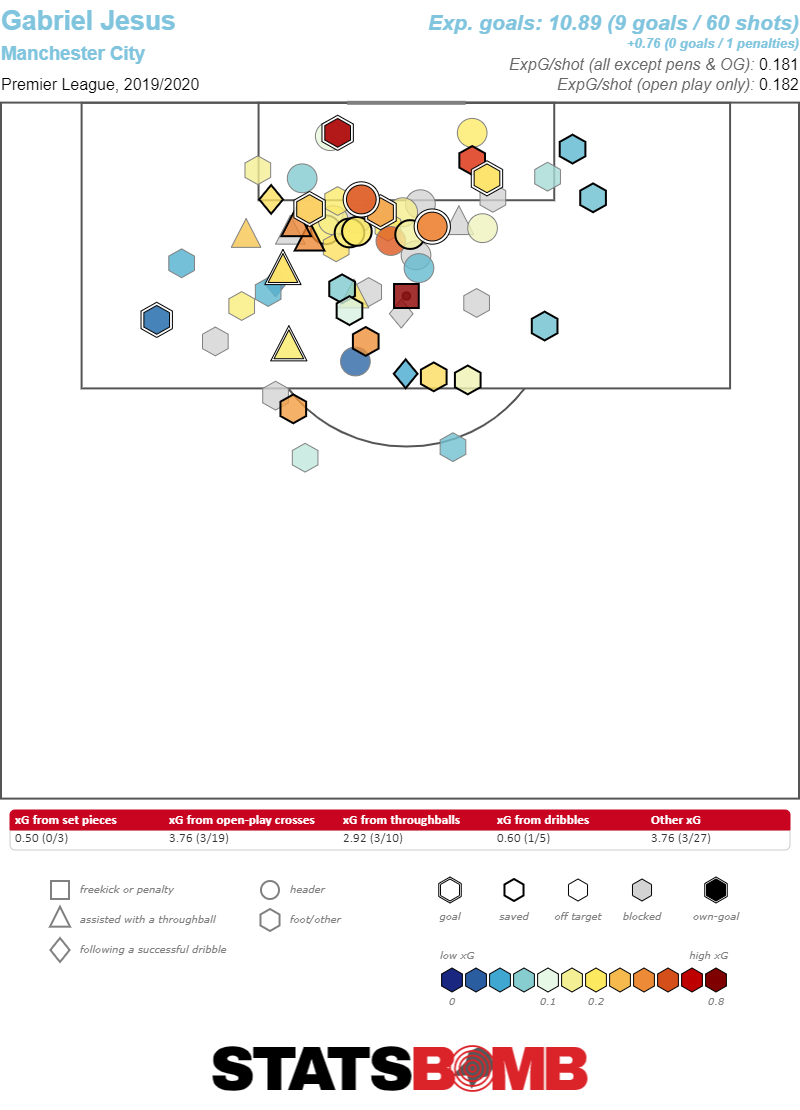

Manchester United and Arsenal are similarly undergoing their own forms of youth movements, although for reasons somewhat less clear than Chelsea’s transfer ban. United spent large on defenders last summer, bringing in Harry Maguire and Aaron Wan-Bissaka while letting go of Romelu Lukaku and Alexis Sánchez (though, granted, the two are at very different points in their careers and have had very different fates at Inter Milan). Of their young players, only Marcus Rashford makes the 0.30 cutoff, with a 0.49 combined xG and xG assisted a respectable fourth among the kids, behind only Gabriel Jesus, Abraham, a surprise player who we’ll get to in a second, and Pulisic. Daniel James just about sneaks on at the very end of this list at 0.31 combined stats. It’s also worth noting that Mason Greenwood just misses the minutes cutoff, or else he would join James at 0.31, so if he continues to produce in the minutes he’s given expect him on the list if it's revisited at the end of the season. For Arsenal, it’s Gabriel Martinelli who appears on the list although he barely makes the minutes cut. Still, at only 18 years old, his 0.35 combined numbers are a bright sign, placing him eighth on the list. It’s also understandable that Arsenal, despite playing their kids, have just one player on this list and it's an attacker with limited minutes. They do still have Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang, Alexandre Lacazette and Mesut Özil on the books after all. Most of their kids are, to one degree or another, midfielders.  Rounding out the top portion of the table, there’s Jesus at Manchester City who sits atop the list. He's putting up monster stats, as he always does, 0.86 combined xG and xG assisted while also missing tons of shots. The distribution of his numbers is fairly comical with him missing more than expected, averaging (a still obscenely high) 0.63 goals per 90 and an even obscenely higher 0.73 xG per 90 but making up for it by scoring 0.28 assists per 90 despite assisting only 0.09 xG per 90.

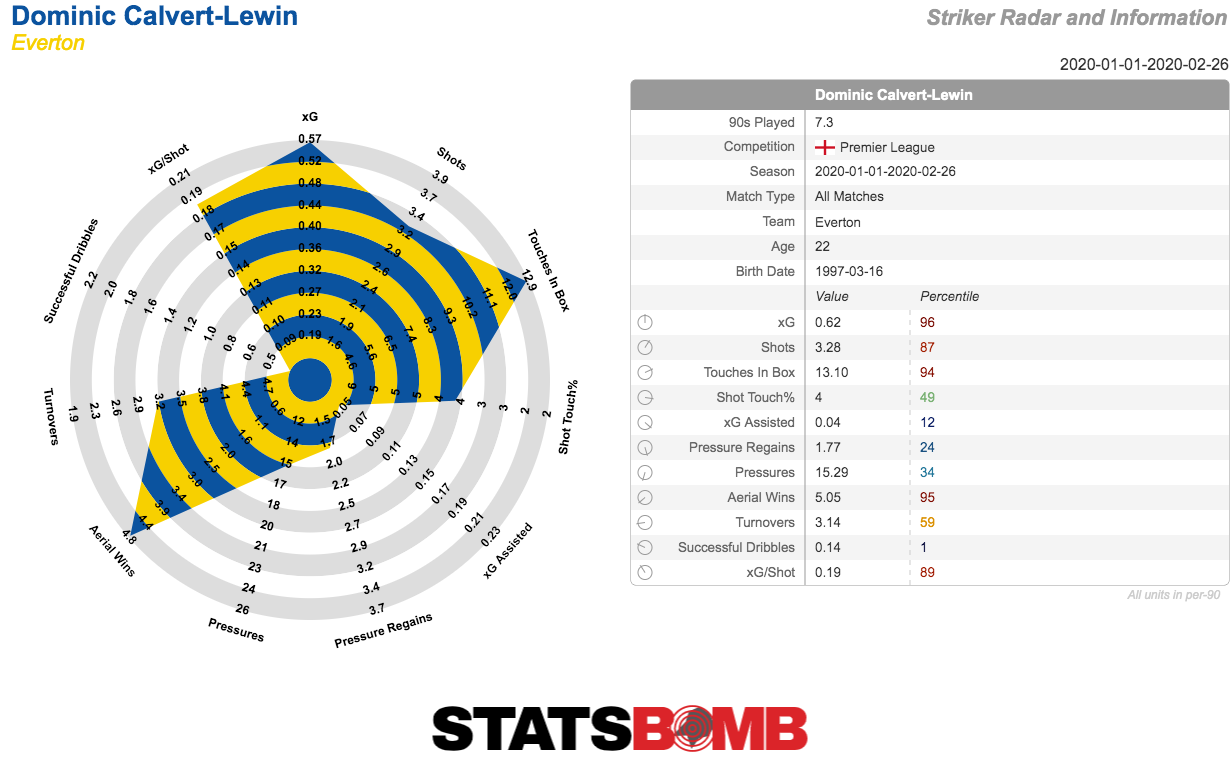

Rounding out the top portion of the table, there’s Jesus at Manchester City who sits atop the list. He's putting up monster stats, as he always does, 0.86 combined xG and xG assisted while also missing tons of shots. The distribution of his numbers is fairly comical with him missing more than expected, averaging (a still obscenely high) 0.63 goals per 90 and an even obscenely higher 0.73 xG per 90 but making up for it by scoring 0.28 assists per 90 despite assisting only 0.09 xG per 90.  Meanwhile, in the kind of age distribution you might expect from an upstart, Leicester City have Harvey Barnes sitting seventh on the list with a robust 0.48, Wolves have Pedro Neto in limited minutes on 0.40 in ninth and then in 11th there’s Liverpool’s assist machine, Trent Alexander-Arnold, with 0.37. But, part of what makes this season so special is that the super talented kids are not restricted to the top of the table (not even when I generously include midtable big six club Arsenal as an honorary member of the top of the table list). Everton, in fact, have three separate attackers on the list, second to only Chelsea. The standout is our mystery player from earlier in the piece, Dominic Calvert-Lewin, who has quietly turned himself into one of the better pure strikers in the Premier League. Not only is he fourth among young players in combined xG and xG assisted with 0.53, but his xG per 90 of 0.48 places him seventh overall. That puts him ahead of players like Jamie Vardy, Marcus Rashford, and Harry Kane, just to name a few players not selected at random at all.