Bottom of the Premier League table, things are looking particularly bleak for Swansea City. Mere months ago, the club was touted as a role model, with its unique mix of fan involvement and a distinct footballing style. Once a haven for the development of up and coming managers, with both Merseyside clubs coached by Liberty Stadium graduates in the 2013/14 season, the club has become something of a rotating door in that sense. Worse yet, the purchasing of a major stake by new American owners was done behind the back of the Supporters Trust that formed the back-bone of the club by owning 21% of it, causing frosty tension and even the possibility of a lawsuit about the nature of the sale.

How might decision makers at the club attempt to halt this descent down a slippery slope that we have seen so many other clubs topple down before?

Reinstate the Swansea Way

The defining feature of Swansea City has been, until recently, its style of football. The club enamoured hipsters all over the world, myself included, with its unique blend of possession based football from Roberto Martinez to Brendan Rodgers to Michael Laudrup. One of the most unfortunate developments of the last few years has been the loss of this identity, beginning with the appointment of club stalwart Garry Monk as manager.

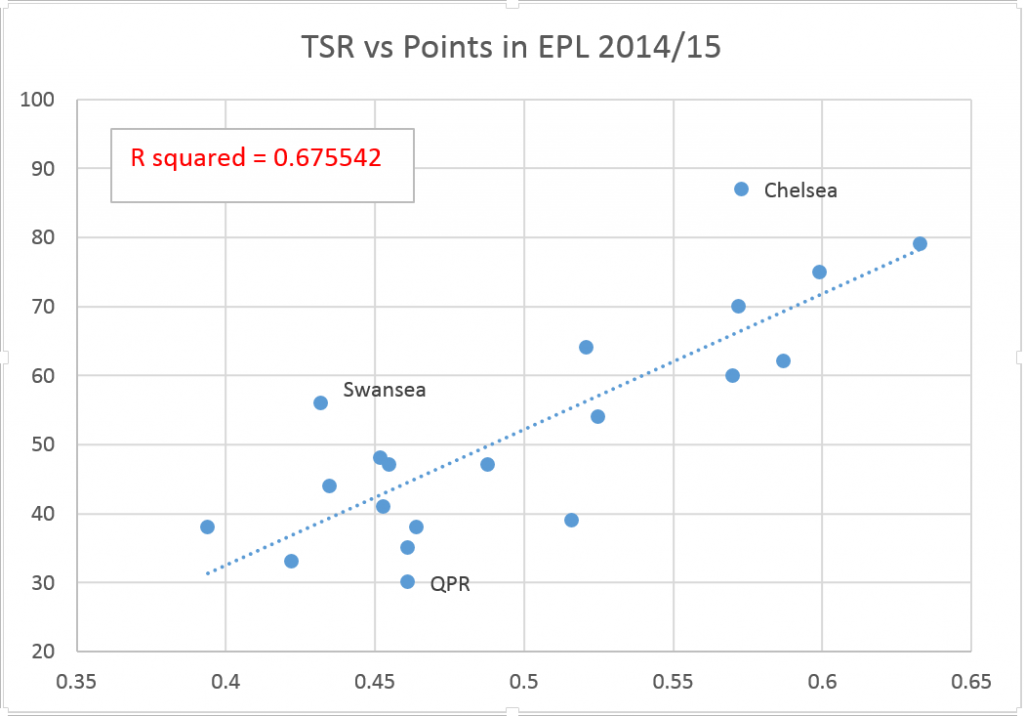

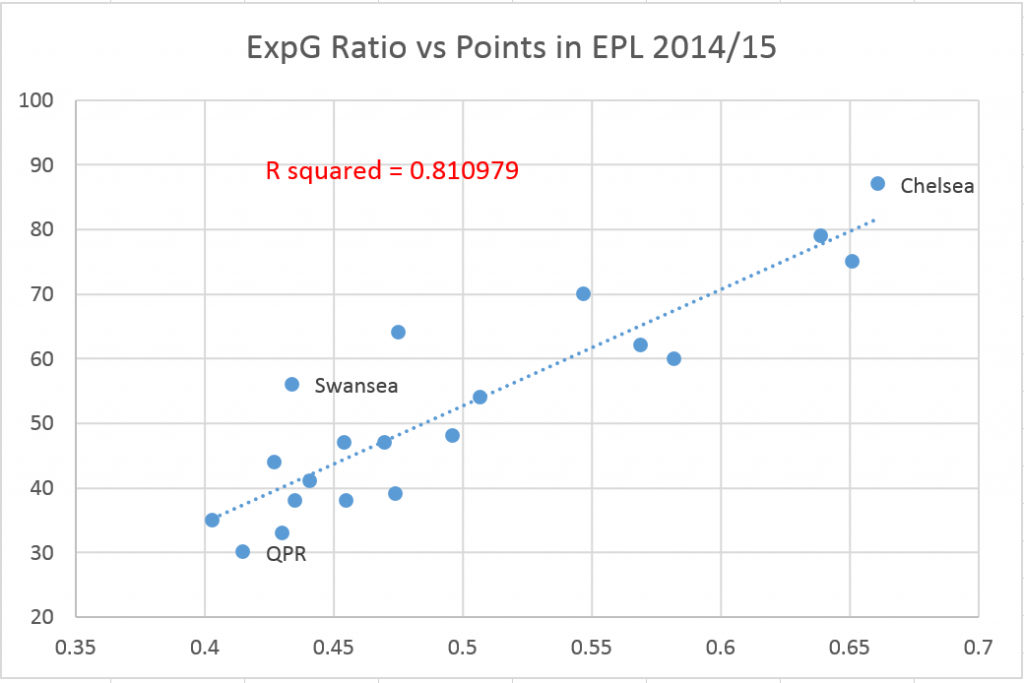

Monk led the club to a record high 8th placed finish with a slightly more pragmatic style than fans were used to. At the time, no one was complaining, but the following season’s early problems quickly complicated matters. To those of us involved in assessing underlying performance, Swansea’s regression came as no surprise. Before long, Monk was gone and replaced. His replacement, Francesco Guidolin, met the same fate and was succeeded this season by Bob Bradley. Barely a year later after Monk was sacked by the club, Bradley was also on his way out.

Having a distinct tactic is useful for a variety of reasons. It forces recruitment through an extra layer of checks, moving the question from ‘Is this player good?’ to ‘Is he good for us?’. The same check applies to managers, and, in truth, it is here that decision makers at the club have abandoned the club's distinct style.

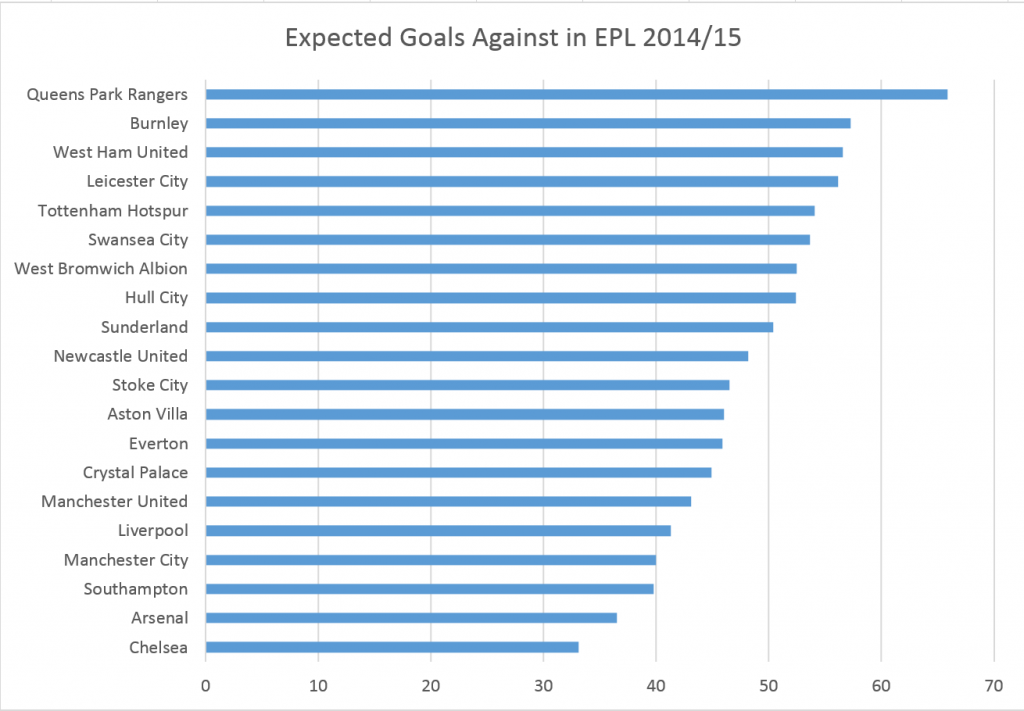

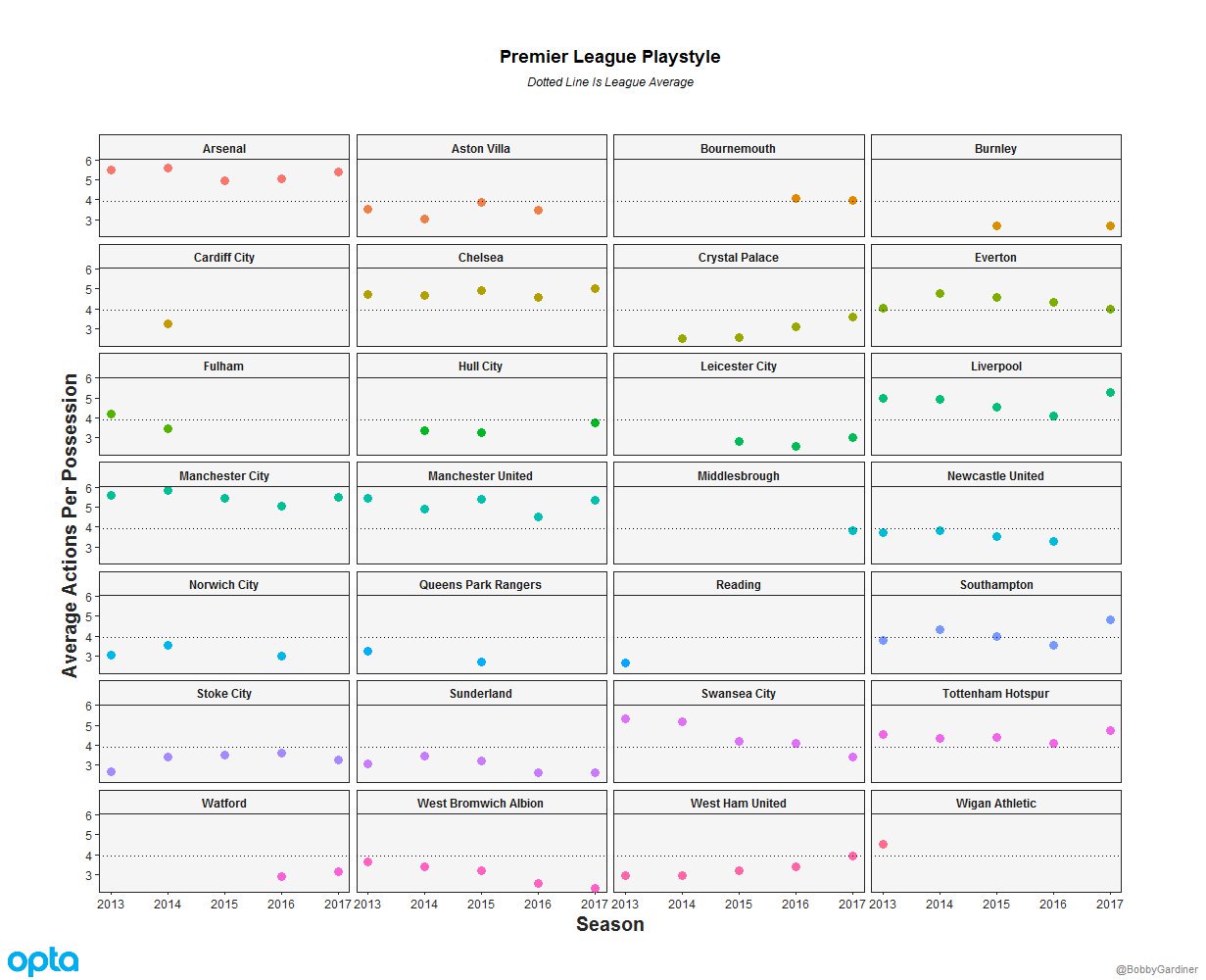

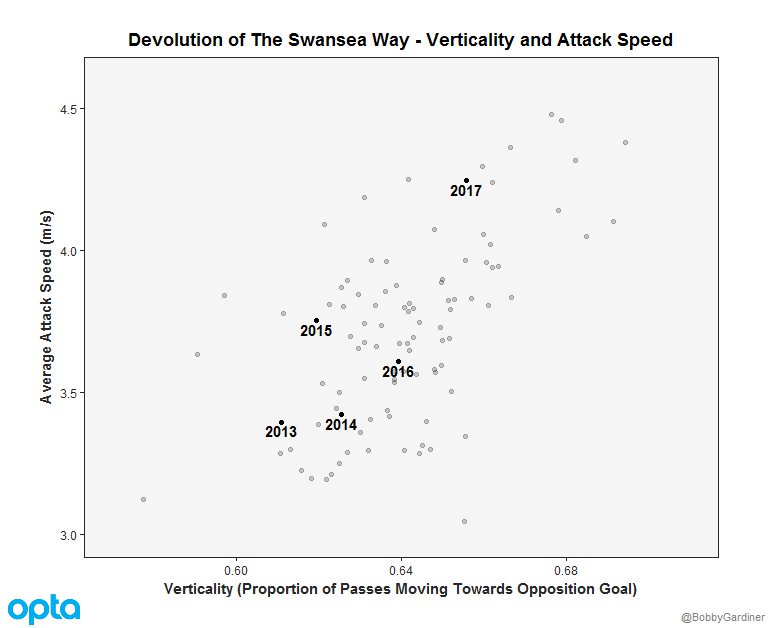

In Swansea’s case, a possession style was most useful as a defensive tool. Where big clubs with high average possession often spend most of it in their opponent’s half, Swansea would recycle the ball in their own half as a defensive tactic. This made breaking them down hard, while also making their attacks slow.

This season, Swansea’s defence has been anything but hard to break down, and their attack has been anything but slow. Considering many of the personnel in the team are the same as under Michael Laudrup, this seems a bizarre state of affairs. This is clearest in the futility of the performances of Leon Britton, whose conscientious and careful possessions of the ball are completely undermined by the team’s overall system and focus on optimistic wing play.

On the other hand, having a similar squad spine to the possession days should make it easier to reinstate the style. The most difficult part, and the most controversial of my suggestions, would be in resisting the urge to hire a manager with a different system for the sake of it.

Resist Panic Hiring

Alan Curtis is an extremely experienced member of staff, and one that has been at the club throughout its entire journey. His training methods will be familiar to the players, as will his ideas, as has been evident from his caretaker stints: last campaign when Guidolin was unfortunately ill, Curtis stepped in and coached the team for a couple of games. Against West Bromwich Albion, the team played closer to the Swansea Way than they had in years, and strolled nonchalantly to a 1-0 win.

Appointing him as a caretaker manager until the end of the season isn’t even a new idea – the club did it after Monk was sacked, only to back-track and appoint Guidolin shortly after. Curtis should be given the reigns until the end of the season not because there is a chance that he may be long-term manager material like Monk, but because the mid-season options for replacements are so dire.

Considering the financial might of the Premier League, these are rather uninspiring possibilities - lest we forget that Rafa Benitez is manager of Newcastle in the division below. Clement and Rowett are managers with the potential to be future candidates, but, ideally, you’d like to see them with at least another Championship club first. Premier League experience is not a necessity, but some suitable level of experience is, and it's hard to say either of them have it yet. Marcelino is another one I would be interested in, but has already been interviewed for the position before and concerns about his grasp of the language reportedly put the club off.

As much as it may initially seem risky, waiting until the summer allows the club to appoint a manager with the advantage of certainty about what competition they will be in, a much larger pool of targets, and enough time for suitable due diligence.

It seems odd to say this about a club with a recent history of managerial casualties, but the biggest obstacle for Swansea City’s survival isn’t who is manager, it is who is playing.

Recruit with focus

For a club lauded for its intelligent recruitment, particularly the time-old legend of £2m Michu, the squad has deteriorated to an almost laughable state. Wayne Routledge is starting in the Premier League in 2016. Ashley Williams, long-time captain, was replaced by Ajax bench-player Mike van der Hoorn and Barnsley's Alfie Mawson. Andre Ayew, who scored an impressive 12 Premier League goals last campaign, was replaced by Nathan Dyer returning from a loan to Leicester City.

The one area that the club did solve a problem was up-front, with the signings of Fernando Llorente and Borja Baston, the latter of which has struggled to get game time but will likely still come good. Unfortunately, the Spanish pair are forced to rely on their chances being created predominantly by the ineffectual Modou Barrow, who is a player with clear potential but with equally clear deficiencies, and Routledge, who is useless in a wing-oriented counter-attacking system at the age of 31. Jefferson Montero, by far the club’s best chance-creator, has failed to cement a place in the starting eleven so far, but will hopefully soon.

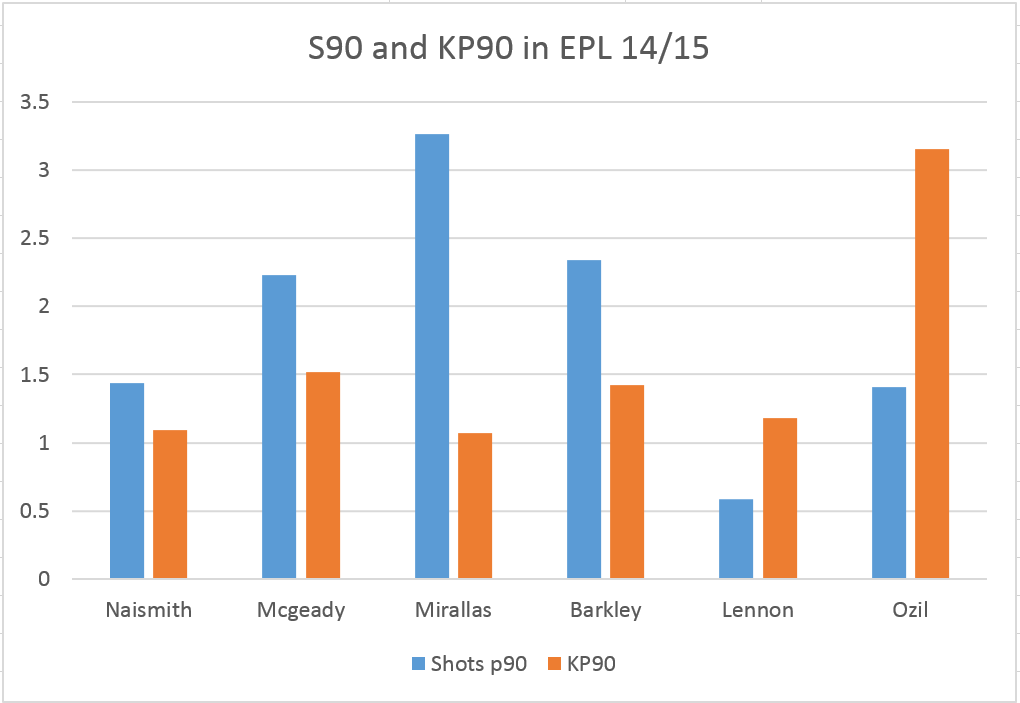

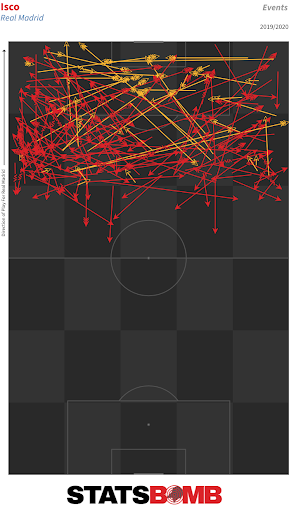

More than anything, the combination of a deterioration in squad quality and incoherent tactical style has damaged Gylfi Sigurdsson, unquestionably the club’s star player. Since Wilfried Bony was sold to Manchester City, the Icelandic talisman has been forced to carry the increasingly heavy burden of the team’s attacks on his shoulders. This can be seen most clearly in the ratio of his shots to key passes over the last few seasons, and in the number of shots from outside of the box.

The club desperately need another winger and a centre-back. They will already be working on this, and have brought in famed analytics-community pioneer Daniel Altman as a ‘transfer consultant’. However, if reports are to be believed, it could be argued that Altman’s expertise will be used at the wrong end of the recruitment process - WalesOnline reported that Altman will not suggest players to the club, but rank their separately created shortlists. Given the depth of statistical data available and the relative ease with which tactical styles can be profiled, it would surely make more sense for shortlists to be generated through statistical filters before further holistic analysis is done with more traditional methods.

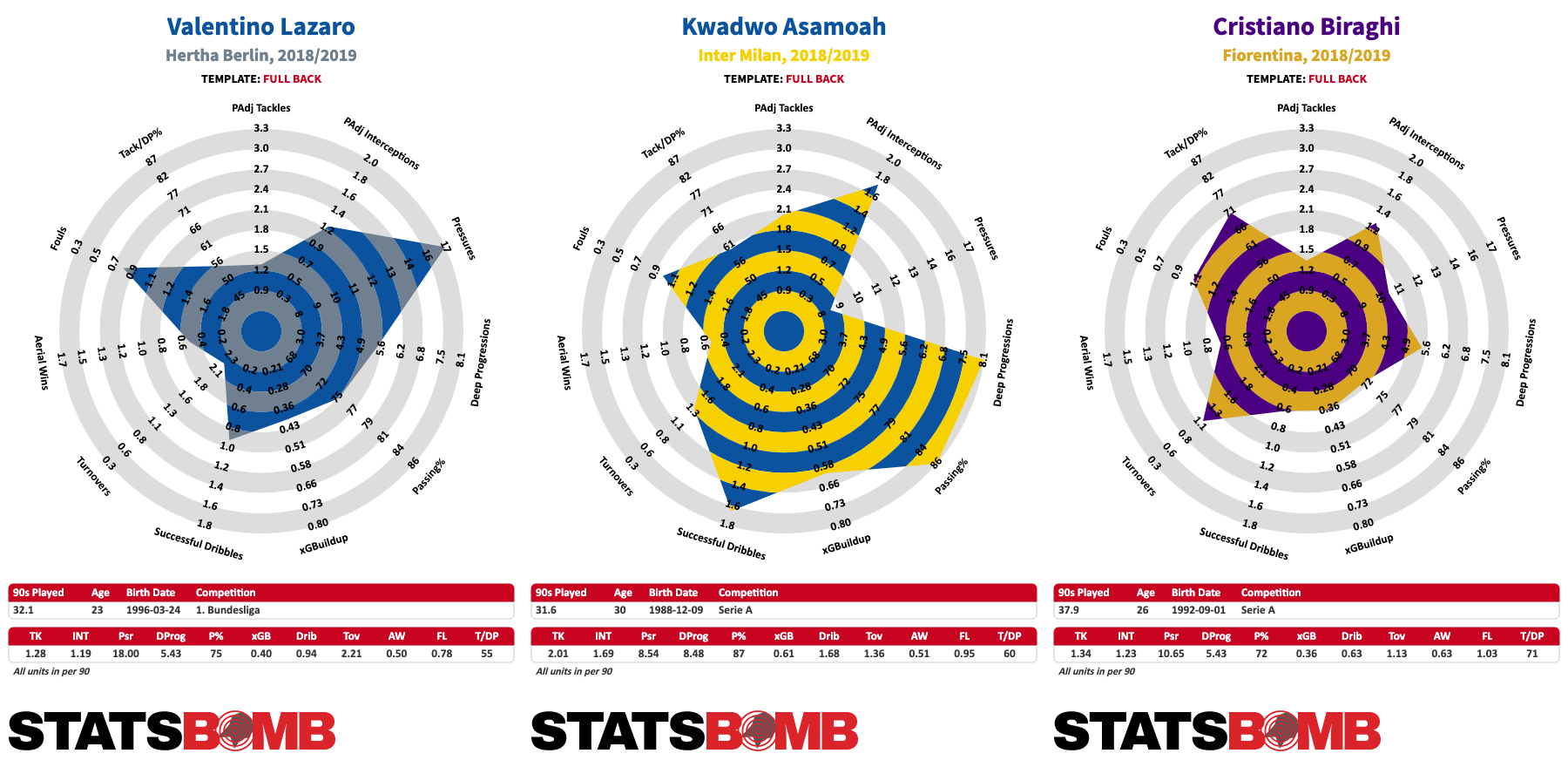

Regardless of the process, the focus of January's recruitment should be honed on the specific qualities needed from new players. Ideally, the initial check would be whether or not they are suited to a possession-based tactical system, but this would depend on that style being revived. Recent reports have linked Swansea to Luciano Narsingh, PSV's speedster winger, but I would argue that the team needs more of a Dusan Tadic style wide player - one that can join in comfortably with build-up, like Andre Ayew did last season and Wayne Routledge used to be able to. Centre-backs are particularly difficult to recruit, so before doing so the club should figure out who it is that he is likely to be playing with: Jordi Amat or Federico Fernandez? Each have different individual weaknesses that should be complemented by their new partner.

Conclusion The task of saving Swansea City is a huge but not impossible one. It takes investment from the new owners, conscientious decision making, and the ability to hold nerve when panic alarms are ringing all around. To maximise the club's chances of survival and also build a stable foundation for rebounding back from relegation, three recommendations should be adopted: reinstate the Swansea Way, resist panic hiring, and recruit with focus.

Appendix: Post Clement Update

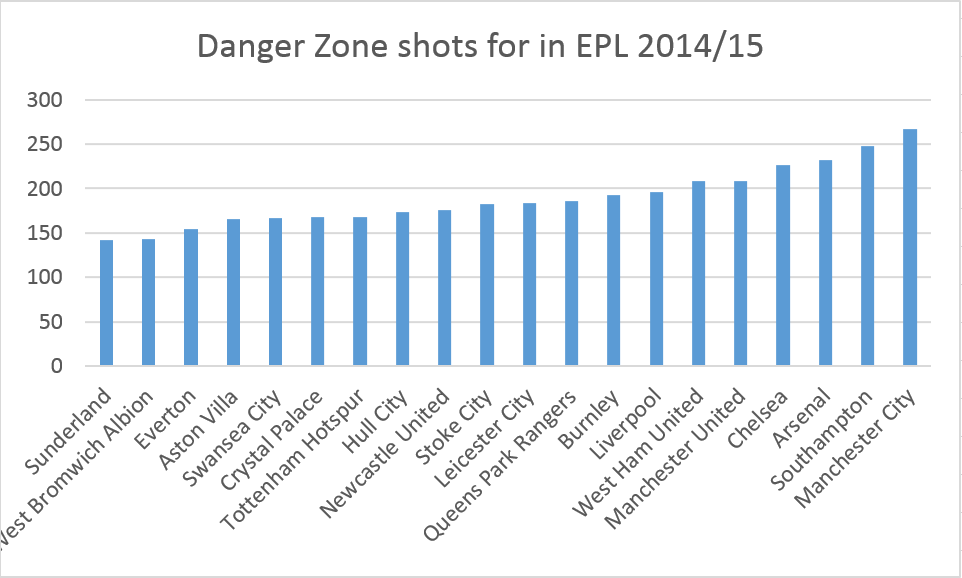

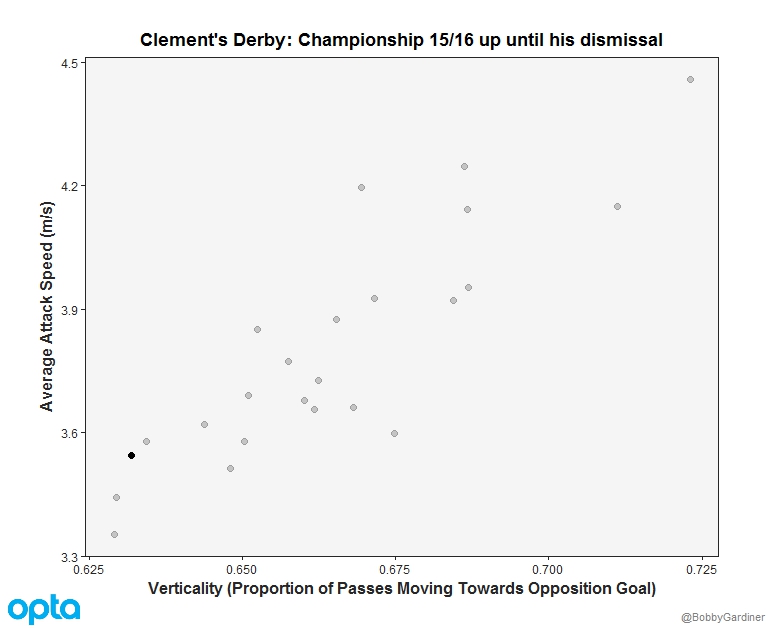

Since this piece was posted, Paul Clement has been appointed as the manager of Swansea. Of all the candidates available, he is the one I would have complained about least. There are some obvious caveats, like his limited experience as a first team manager, but to what extent you can criticise him for that is difficult to say given that his sacking at Derby was confusing (to say the least). Stylistically, Clement's Derby were reminiscent of the Swansea of yesteryear, attacking slowly and indirectly:

This is a promising finding for those who, like myself, are keen for the Swansea Way to return. Although I may have waited until the summer myself, the Clement appointment can hardly be accused of being made in a panic and, hopefully, signals a return to the style of football that the club became known for. Let's see how the January transfer window plays out - over to you, Altman.