Manchester City won the 2013-2014 Premier League with a diverse and international (and very expensive) squad. Of the players who made 20 or more league appearances, a full eight different nationalities were represented (nine if you count their Chilean manager, Manuel Pellegrini). Only one first choice squad player, goalkeeper Joe Hart, was English.

In many ways Manchester City is representative of what many see as the future of European football, one in which hyper cross-pollination of playing styles and tactics renders our old heuristics (Spain = tiki-taka, Italy = catenaccio , etc.) useless. In this future world of European football, then, we might expect the distribution of formations/tactics to be fairly consistent across different leagues. Of course that is not the case now, and quite possibly will never be.

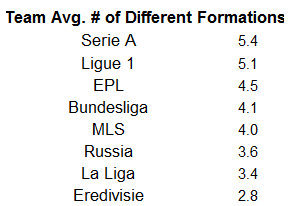

In the complex world of game theory and football formations, sometimes it behooves a manager to stick with an unsuccessful setup for no better reason than it is what everyone else in the league is doing; many people do not like to take risks, especially if their job is on the line. Conversely, in a league like Serie A where using different formations/tactics from game to game is almost an obsession, an adherence to one formation might be frowned upon.

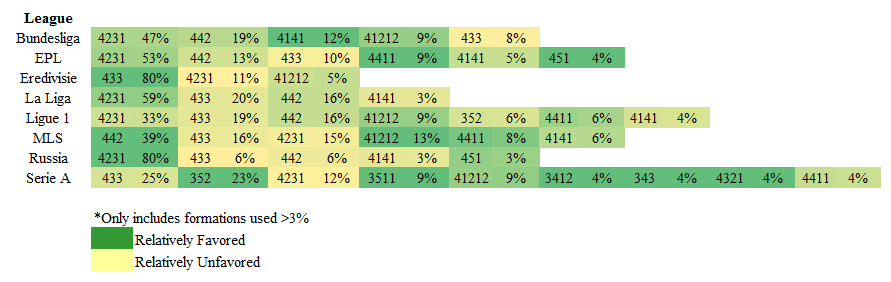

It should be stated that while this piece is about "tactical" variance our only measurement tool is "formation" variance. Formations and tactics are not necessarily the same thing. For example, a 3-5-2 might in practice more resemble a 5-3-2 and any formation can exist in an attack-minded or defensive form. However, to the extent we are measuring tactical heterogeneity/homogeneity it seems self-evident that measuring formation variance is probably as good of a proxy as any. Formation information comes from Opta, whose analysts watch every game for each team they are assigned. Also noteworthy is this data does not include any in-game changes and is merely how each team lined up at the start of the game. Information is from the last completed season ('13-'14) and includes only formations used more than 3%. Formations are listed from left (most used) to right (least used).

A couple things stand out here:

1. The Eredivisie loves the 433 and Russia loves the 4231, almost to the exclusion of any other formation.

2. Serie A demonstrates a tactical diversity not seen in other leagues (see below).

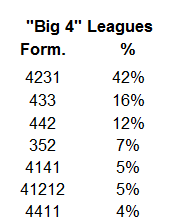

The "favored" and "unfavored" formations are partially a symptom of the fairly eclectic mix of leagues included in the analysis. If we just aggregated all the teams from the "Big 4" leagues (Bundesliga, EPL, La Liga, Serie A) this is what the results look like:

The 4231 is certainly the fancied approach at the moment, but things can change. For example, MLS has seen a rise in the use of the "diamond" 41212 in 2014. Unfortunately, this analysis does not include any data from previous seasons. Will the homogeneity in the Dutch approach and heterogeneity in the Italian approach hold in the face football globalization? It will certainly be worth watching.