Downloadable on the soundcloud link and also available on iTunes, subscribe HERE RSS feed, if required, here Also available on Spotify, Stitcher

Author: admin

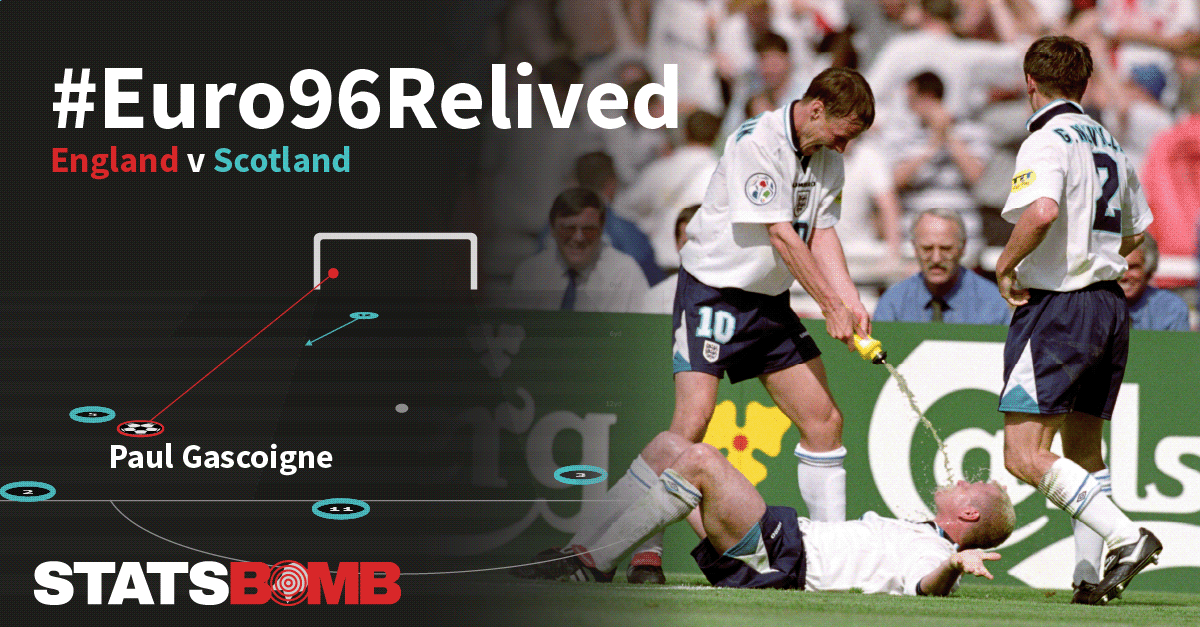

Scotland 0-2 England, Euro 1996

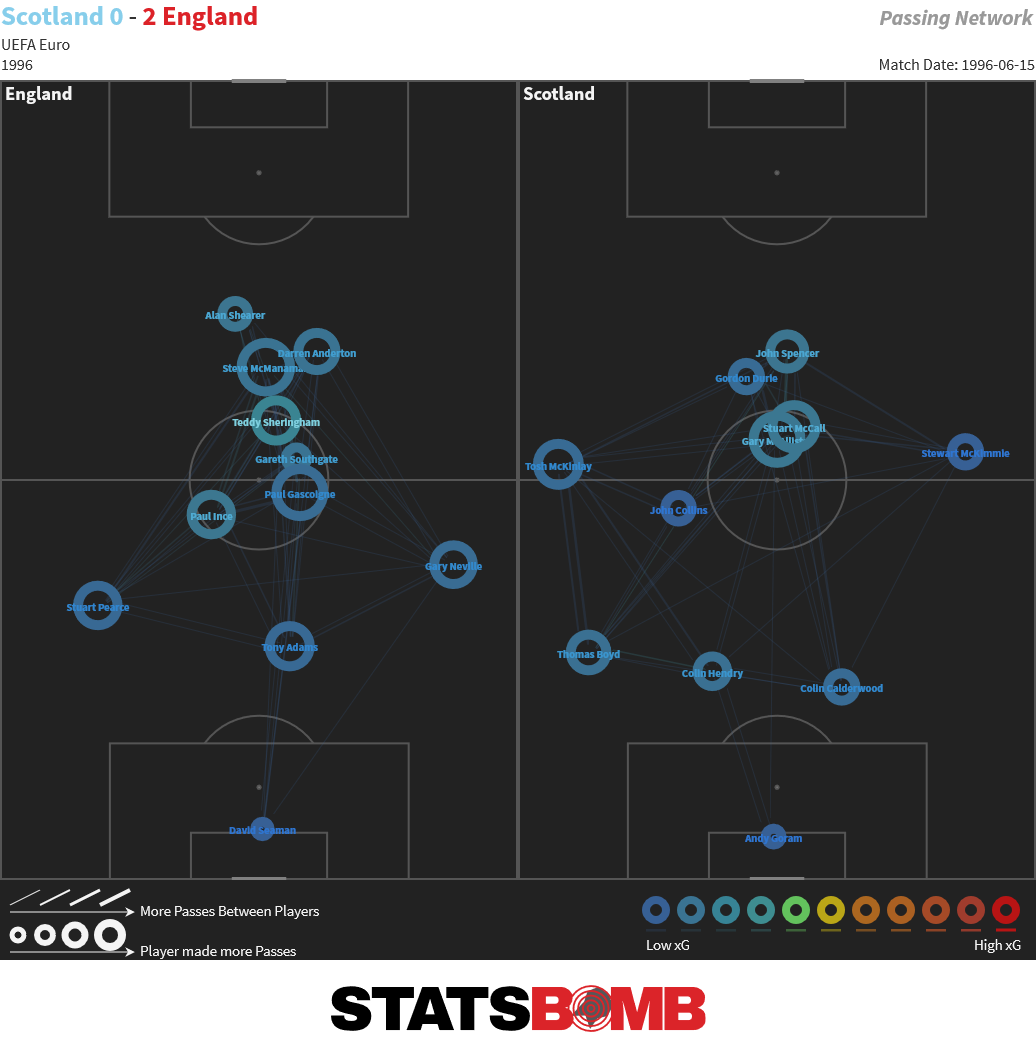

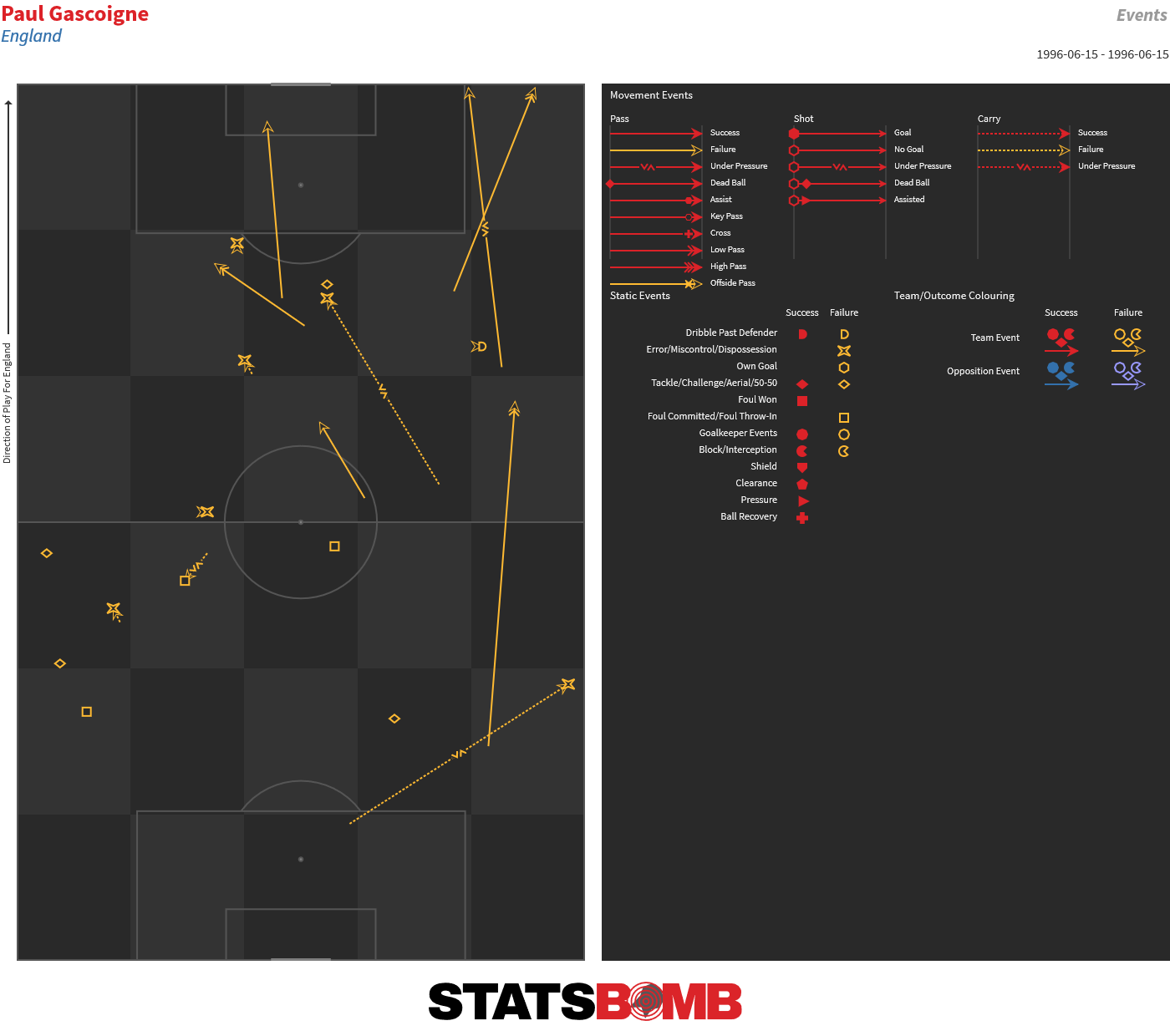

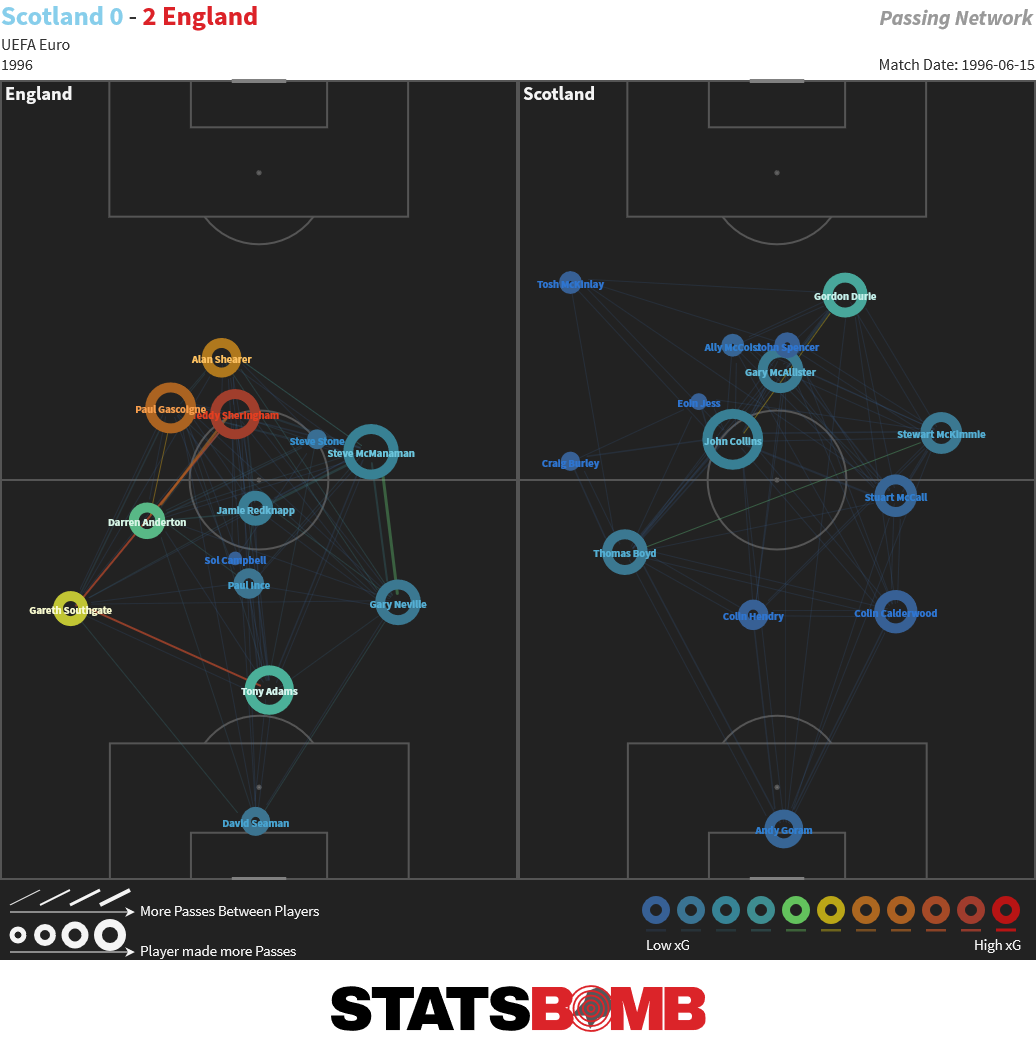

After a mediocre 1-1 draw against Switzerland, could England get back on the right track back in a familiar role as the "Auld Enemy" against Scotland? Terry Venables' 4-4-1-1 from the Switzerland game gave way to something a little different. With full backs Gary Neville and Stuart Pearce flanking Tony Adams in a back three, Gareth Southgate stepped into midfield alongside Paul Ince, with Paul Gascoigne tasked with being a central creative outlet. Teddy Sheringham continued working off Alan Shearer up front, while Darren Anderton and Steve McManaman rotated frequently between the wings. As such the first half pass networks appear congested; but this is merely a reflection of the positional flexibility the England team played with:

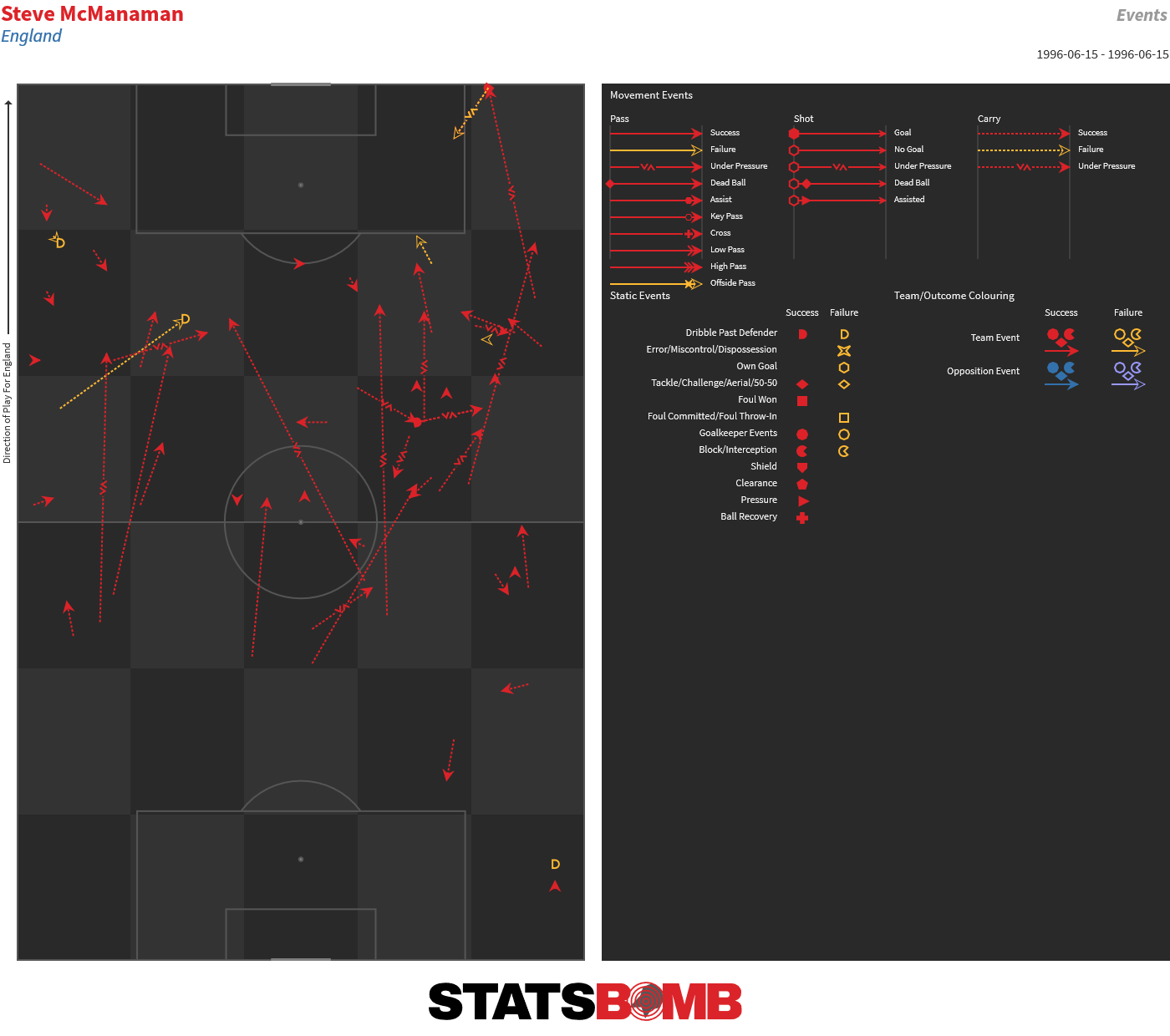

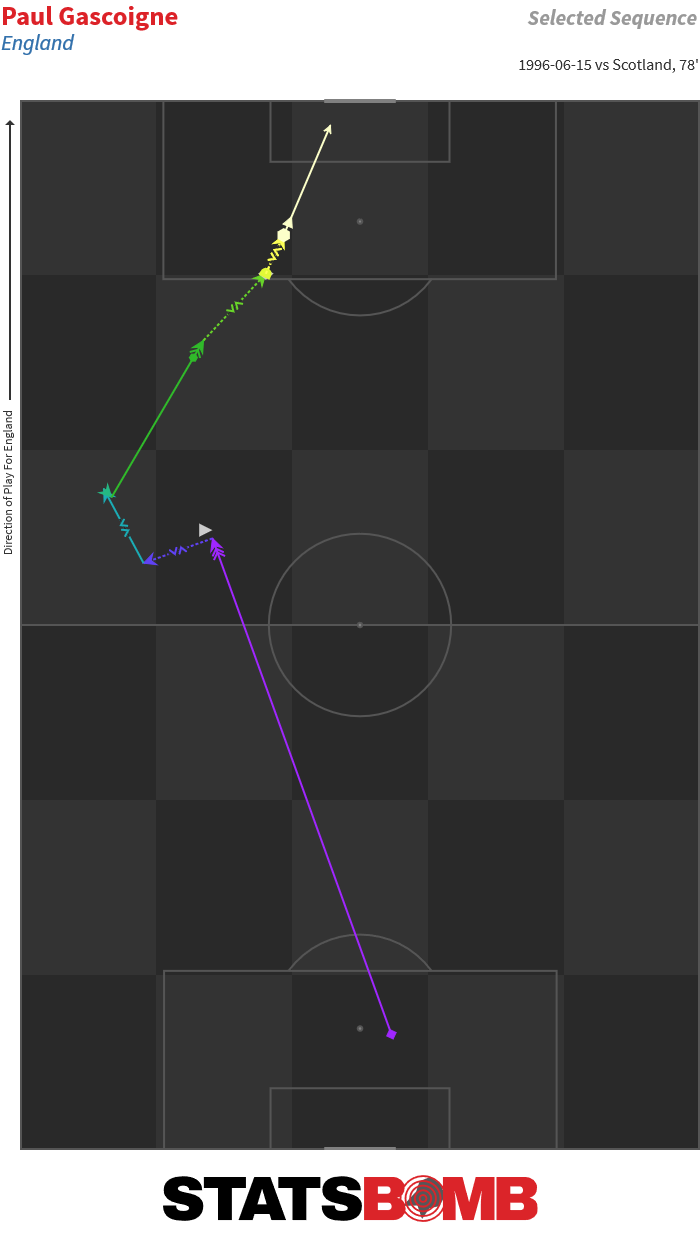

England made a key change at half-time, Jamie Redknapp came on for Stuart Pearce. This meant Southgate could move back to his more usual position in the back line, and Redknapp's passing range could allow England a little more control in the middle of the park. The opening minutes of the second half saw England come to the fore, Sheringham missed an open header deep inside the box and 2 minutes later they were rewarded when Shearer opened the scoring with a far post header from Neville's cross. However, it was Steve McManaman who set the tempo here, moments before freeing Neville to make that cross he'd advanced from halfway before whistling a left foot shot past the post. Indeed, McManaman's ball carrying was a notable plus again in this game, and he saw more of the ball (48 passes, 22 in the final third) than anyone else on the pitch with good retention (86% completion) for a wide player. Here we see how he carried the ball effectively, a series of long runs deep into Scotland's half.

England made a key change at half-time, Jamie Redknapp came on for Stuart Pearce. This meant Southgate could move back to his more usual position in the back line, and Redknapp's passing range could allow England a little more control in the middle of the park. The opening minutes of the second half saw England come to the fore, Sheringham missed an open header deep inside the box and 2 minutes later they were rewarded when Shearer opened the scoring with a far post header from Neville's cross. However, it was Steve McManaman who set the tempo here, moments before freeing Neville to make that cross he'd advanced from halfway before whistling a left foot shot past the post. Indeed, McManaman's ball carrying was a notable plus again in this game, and he saw more of the ball (48 passes, 22 in the final third) than anyone else on the pitch with good retention (86% completion) for a wide player. Here we see how he carried the ball effectively, a series of long runs deep into Scotland's half.

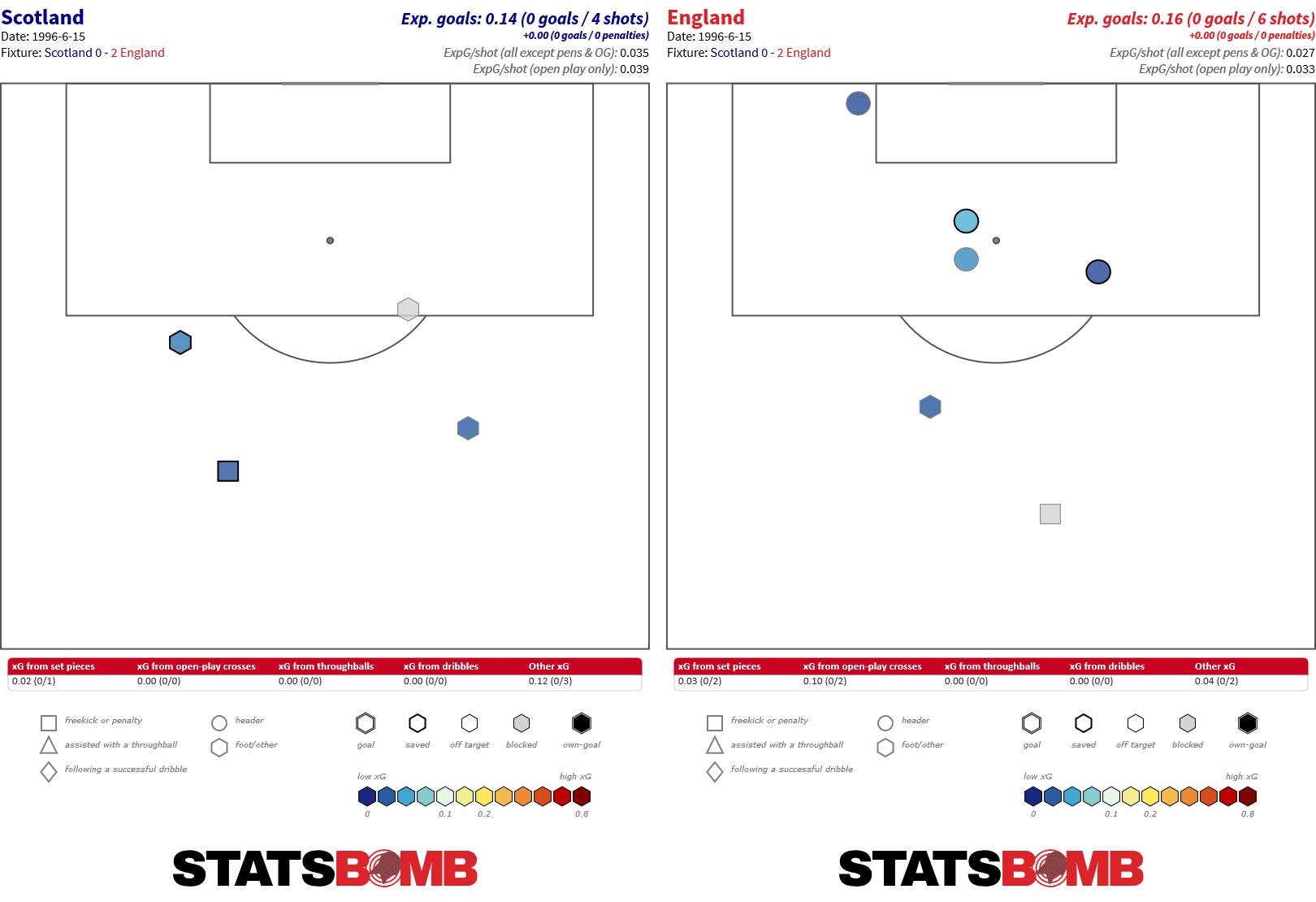

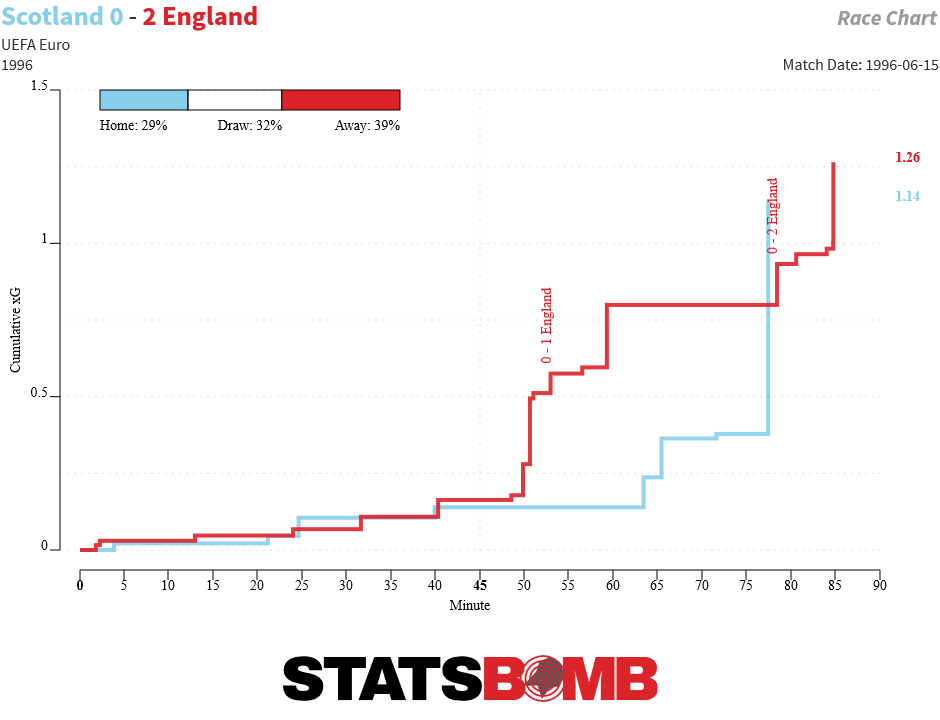

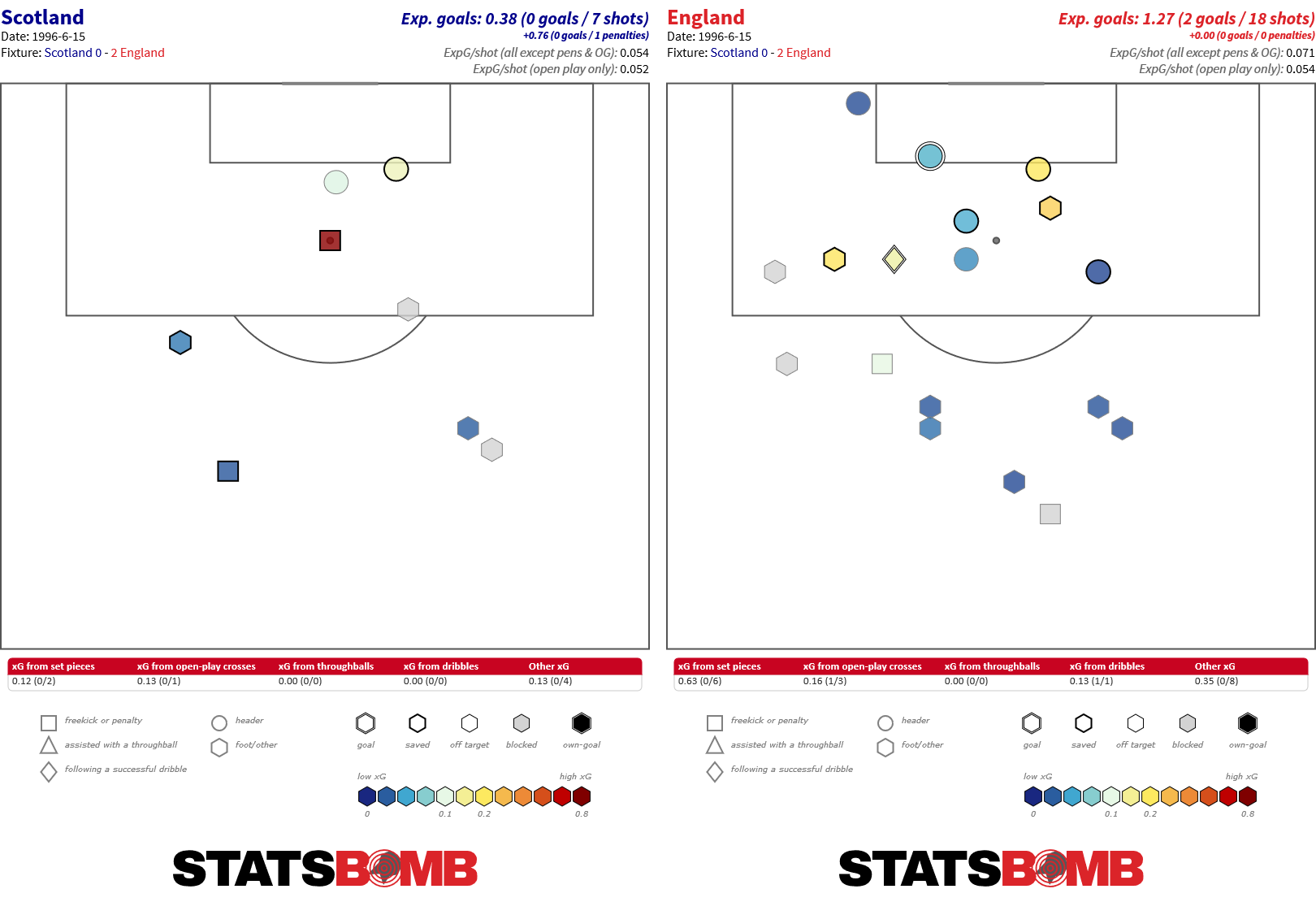

By the end of the game, England were good for their win. The penalty had been Scotland's only good quality chance in the game and England's shot count and expected goals were superior:

By the end of the game, England were good for their win. The penalty had been Scotland's only good quality chance in the game and England's shot count and expected goals were superior:

The change of personnel at half time appeared to be effective and the second half shape of the teams was more forward inclined for England than in the first half, Gascoigne especially found himself higher up the pitch and with Southgate back in the back line, the three central midfielders occupied distinct roles, while the wingers remained in more fixed roles with Anderton left and McManaman right. Scotland struggled to get real width high up the pitch:

The change of personnel at half time appeared to be effective and the second half shape of the teams was more forward inclined for England than in the first half, Gascoigne especially found himself higher up the pitch and with Southgate back in the back line, the three central midfielders occupied distinct roles, while the wingers remained in more fixed roles with Anderton left and McManaman right. Scotland struggled to get real width high up the pitch:

If you enjoyed this look at Euro 1996 through a modern lens and want to learn more about how data can evaluate and describe football, you may enjoy our Introduction to Analytics course. Suitable for everyone from interested amateur right up to football professionals, it gives an accessible, fun and informative route into the world of data and football. Sign up here!

The StatsBomb Interviews: James Yorke meets... The Anfield Wrap's Neil Atkinson

What Do We Know About the Premier League?

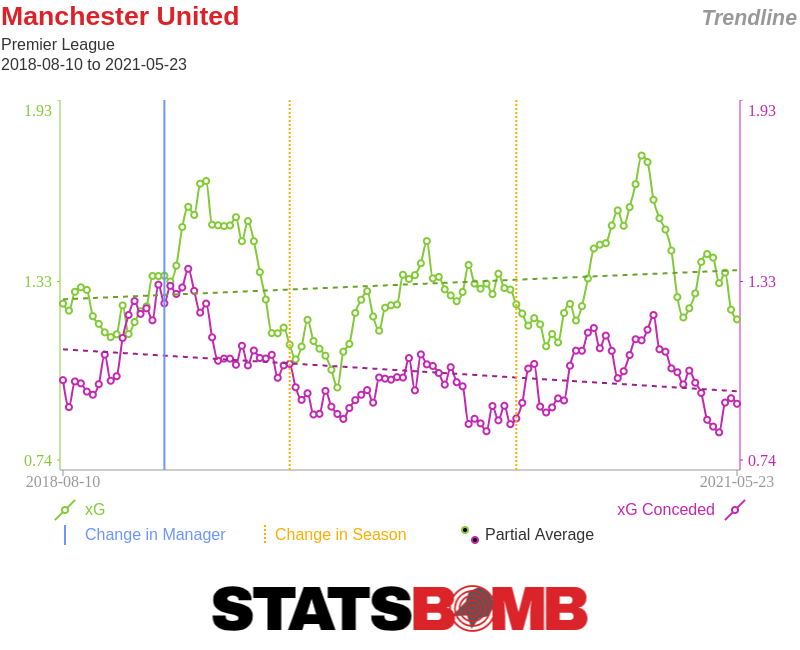

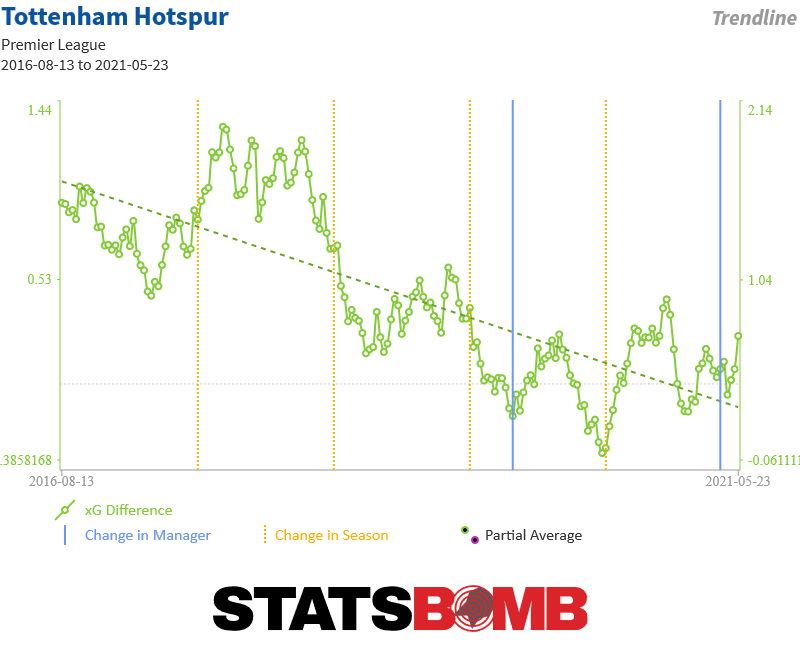

It’s nearly two years since the StatsBomb site was relaunched in its current form, and I’ve been writing about the Premier League here for most of that time. With no football until God knows when, now is the best time to take stock and look at what we’ve learnt over the past couple of seasons. Expected Goals catch up to you... eventually It’s May 2018 and Manchester United are flying high-ish. A second place finish with 81 points is comfortably the best they’ve done in the post-Sir Alex Ferguson era, even if Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City look a long way off. The usual rumblings with Jose Mourinho are going on in the background, but with the right signings there’s no reason why this positive trajectory can’t continue, right? Unfortunately for Man Utd, the rot had already set in some time ago. The 2017/18 season saw them concede nearly 14 goals fewer than expected, while scoring an extra 10. The data suggested the most likely outcome was a decline in results, and guess what? Well, you’re reading a football analytics website in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic, so you probably know Mourinho was sacked by Christmas. It’s true that the side did decline in other ways, but the xG overperformance coming to an end was paramount. United actually conceded 3.5 more goals than expected in 2018/19, and though they scored an additional 4.4, we’re not talking about hugely significant finishing gains.  The same story came true for Mauricio Pochettino at Tottenham, although it took its time. If we look at the xG trendlines, it’s pretty startling how much Spurs start to decline in both attack and defence around spring 2018 and never recover.

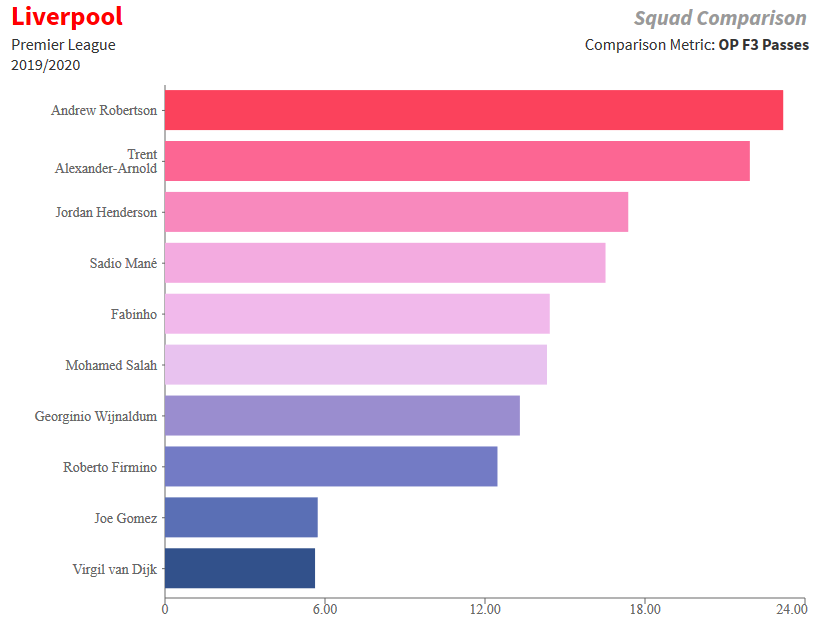

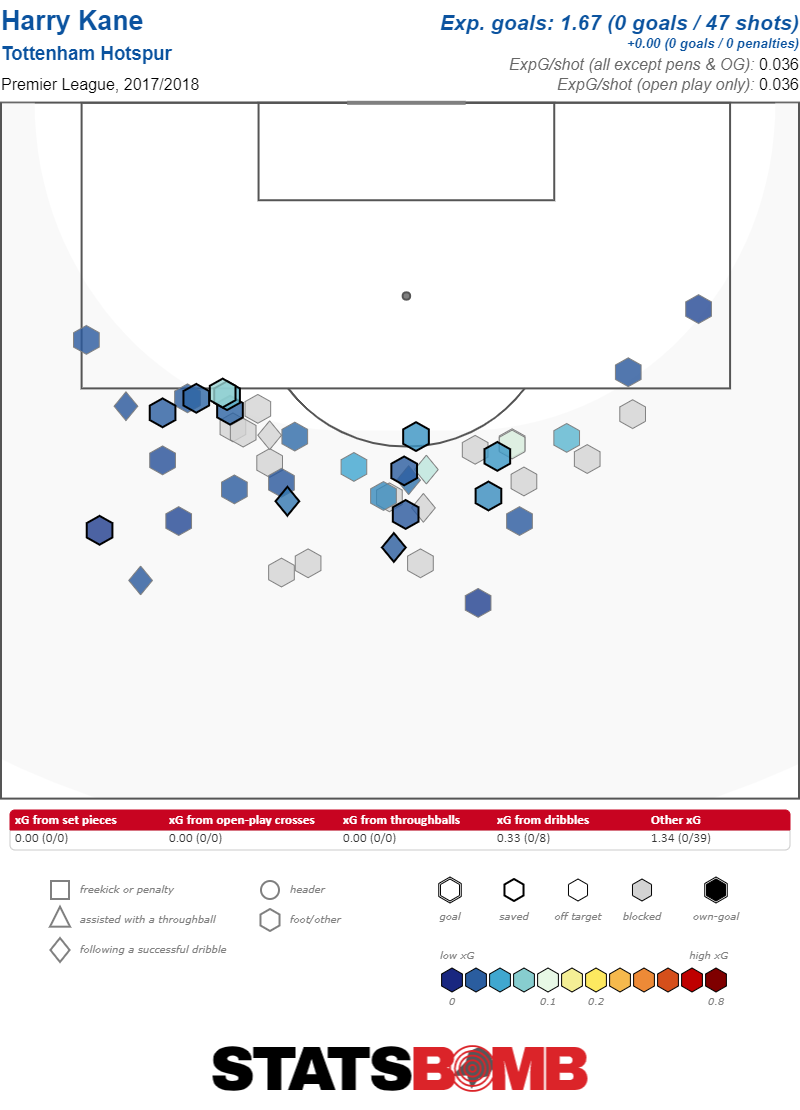

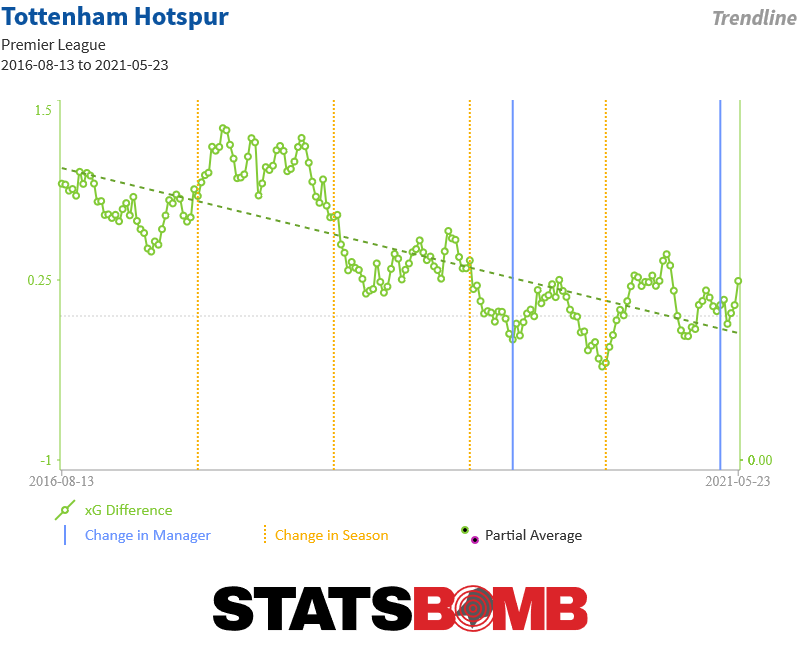

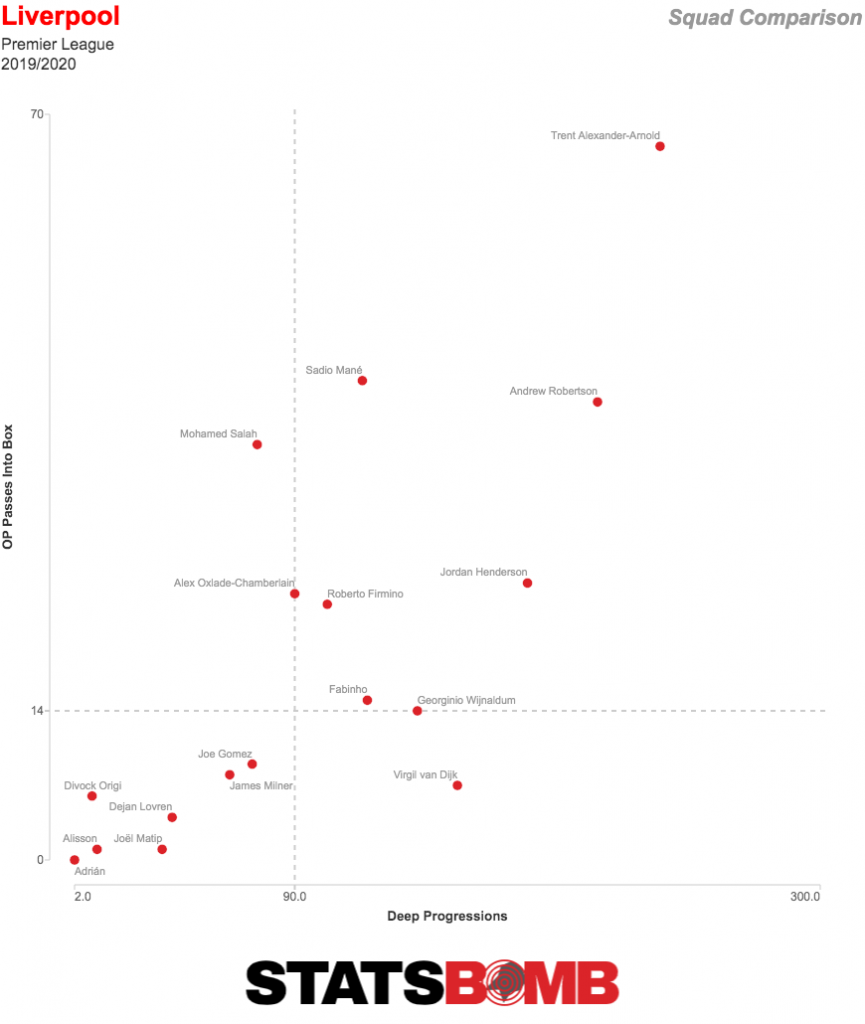

The same story came true for Mauricio Pochettino at Tottenham, although it took its time. If we look at the xG trendlines, it’s pretty startling how much Spurs start to decline in both attack and defence around spring 2018 and never recover.  Spurs spent calendar year 2018 beating xG at both ends of the pitch, scoring nearly 17 extra goals and conceding almost 9 fewer than expected. A number of reasons were put forward to explain this: good goalkeeping from Hugo Lloris, elite finishing from the likes of Harry Kane and Son Heung-min, or even Pochettino’s tactics. It’s entirely possible that some of those factors were in play, but ultimately you can’t outrun xG forever. Different ways to get it forward Liverpool are 25 points clear at the top of the Premier League table. If we ever play the rest of the season out, it will be a coronation process for the Reds. The biggest stats story with Liverpool is in how they move the ball forward. Looking at the graph below, we can see the players most used in moving the ball both into the final third (x-axis) and then into the box (y-axis) are the two full backs, Trent Alexander-Arnold and Andrew Robertson.

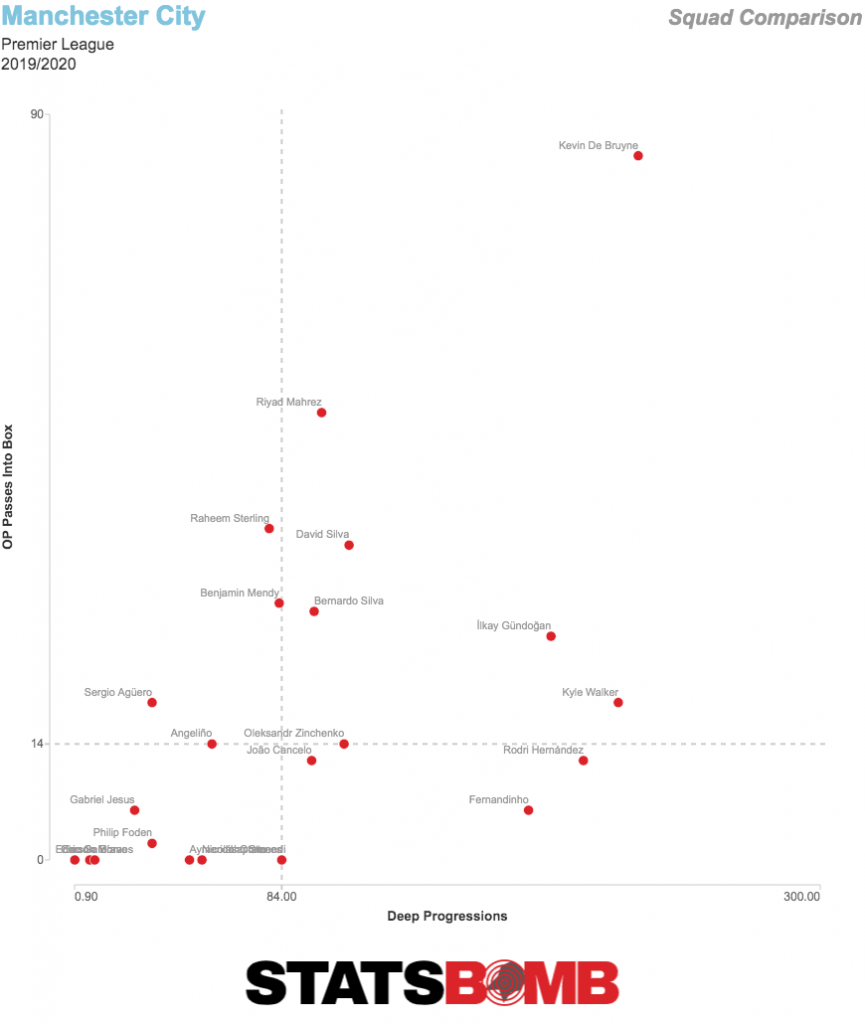

Spurs spent calendar year 2018 beating xG at both ends of the pitch, scoring nearly 17 extra goals and conceding almost 9 fewer than expected. A number of reasons were put forward to explain this: good goalkeeping from Hugo Lloris, elite finishing from the likes of Harry Kane and Son Heung-min, or even Pochettino’s tactics. It’s entirely possible that some of those factors were in play, but ultimately you can’t outrun xG forever. Different ways to get it forward Liverpool are 25 points clear at the top of the Premier League table. If we ever play the rest of the season out, it will be a coronation process for the Reds. The biggest stats story with Liverpool is in how they move the ball forward. Looking at the graph below, we can see the players most used in moving the ball both into the final third (x-axis) and then into the box (y-axis) are the two full backs, Trent Alexander-Arnold and Andrew Robertson.  But then we take a look at second placed Manchester City, and a different story emerges. It’s Kevin De Bruyne town, with the full backs a much smaller part of the picture.

But then we take a look at second placed Manchester City, and a different story emerges. It’s Kevin De Bruyne town, with the full backs a much smaller part of the picture.  The top of the Premier League has two entirely different models for how a team should be able to get the ball forward without sacrificing solidity. There’s the Jürgen Klopp model, which takes the view that midfield should be kept as tight and ugly as possible, but then giving the full backs freedom to roam and become key players in the attack. The Pep Guardiola model, conversely, uses the full backs as facilitators in the midfield areas to make the side more solid, then allowing some of the nominal midfielders to be more involved in the final third. Both “work”, but it helps show the greater tactical variance in the league from 20, 10 or even 5 years ago. High pressing works, but there are other ways There has not historically been an obvious way of measuring "pressing", and a raw count of StatsBomb's pressure data does not instantly show a solution. When we look at the teams making the most pressures, we see a list that doesn't really correspond to most people's ideas of the Premier League's high pressing sides.

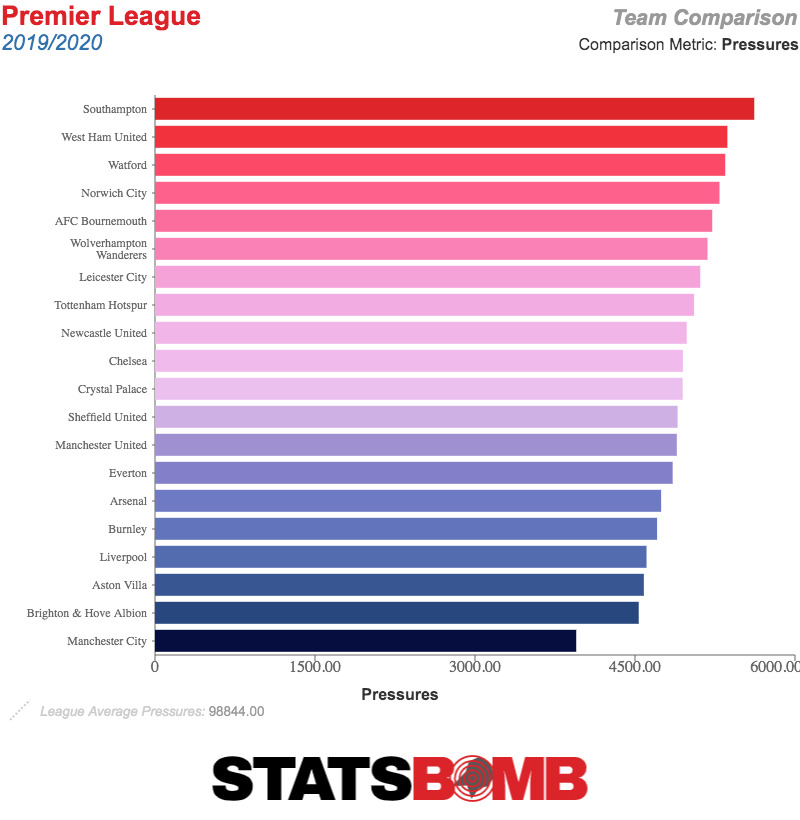

The top of the Premier League has two entirely different models for how a team should be able to get the ball forward without sacrificing solidity. There’s the Jürgen Klopp model, which takes the view that midfield should be kept as tight and ugly as possible, but then giving the full backs freedom to roam and become key players in the attack. The Pep Guardiola model, conversely, uses the full backs as facilitators in the midfield areas to make the side more solid, then allowing some of the nominal midfielders to be more involved in the final third. Both “work”, but it helps show the greater tactical variance in the league from 20, 10 or even 5 years ago. High pressing works, but there are other ways There has not historically been an obvious way of measuring "pressing", and a raw count of StatsBomb's pressure data does not instantly show a solution. When we look at the teams making the most pressures, we see a list that doesn't really correspond to most people's ideas of the Premier League's high pressing sides.  Man City at the bottom! That includes a lot of chaotic defending in teams' own third, so let's strip it down just to pressures in the opposing half. There's a little more of a pattern here.

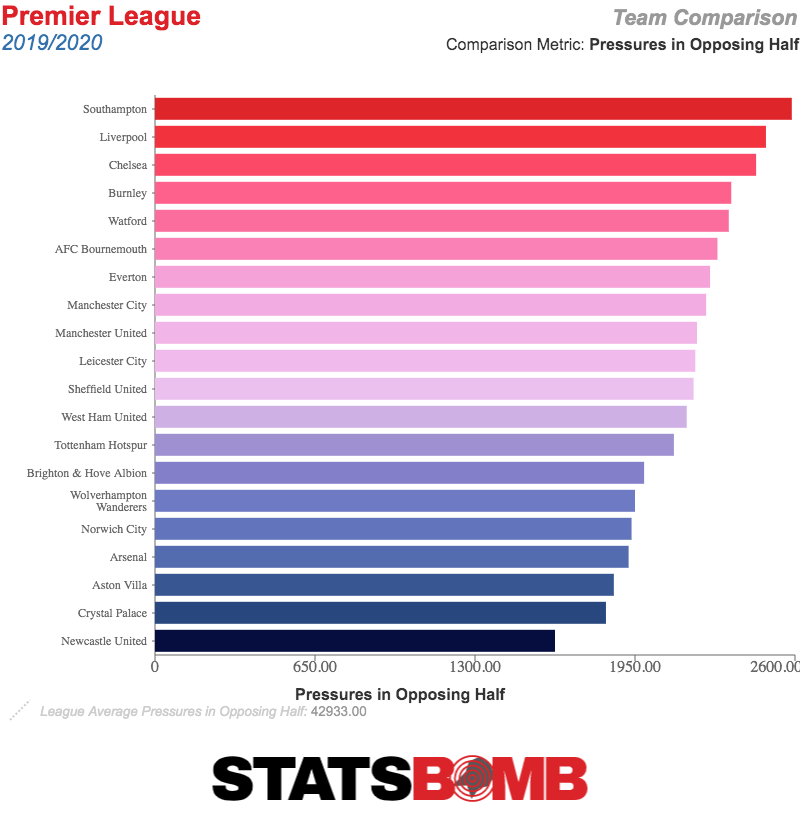

Man City at the bottom! That includes a lot of chaotic defending in teams' own third, so let's strip it down just to pressures in the opposing half. There's a little more of a pattern here.  Man City still look like a middling pressing team, which obviously isn't what most people see with their eyes. They have so much possession that they're rarely having to make many pressures, which is the issue here. Raw numbers of pressures don't seem to tell us much of note. If we just look at the percentage of all pressures made in the opposing half, then guess what? City shoot up to the top of the table.

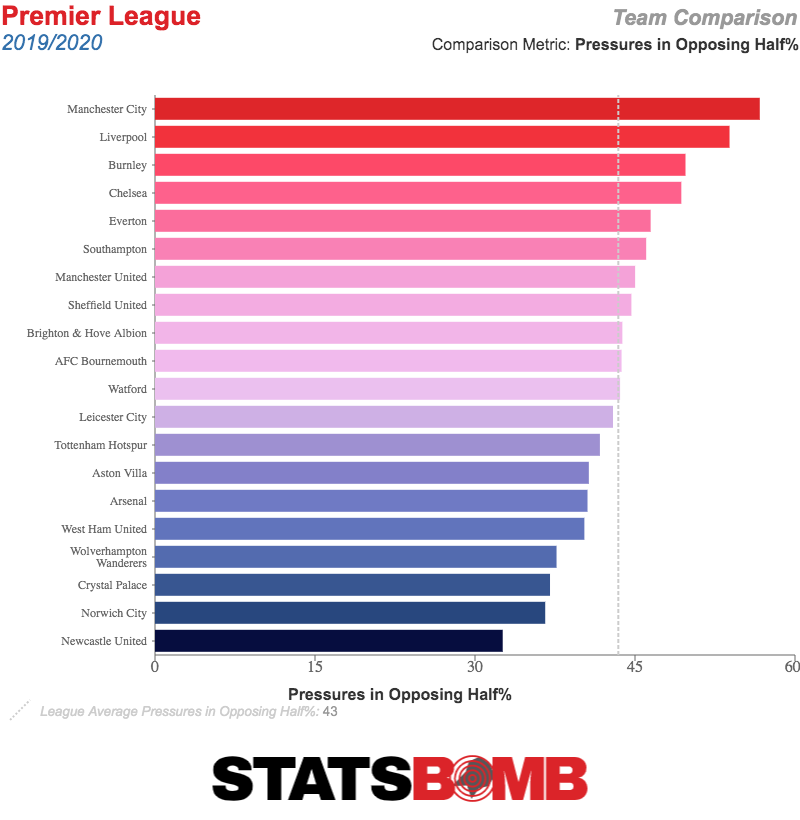

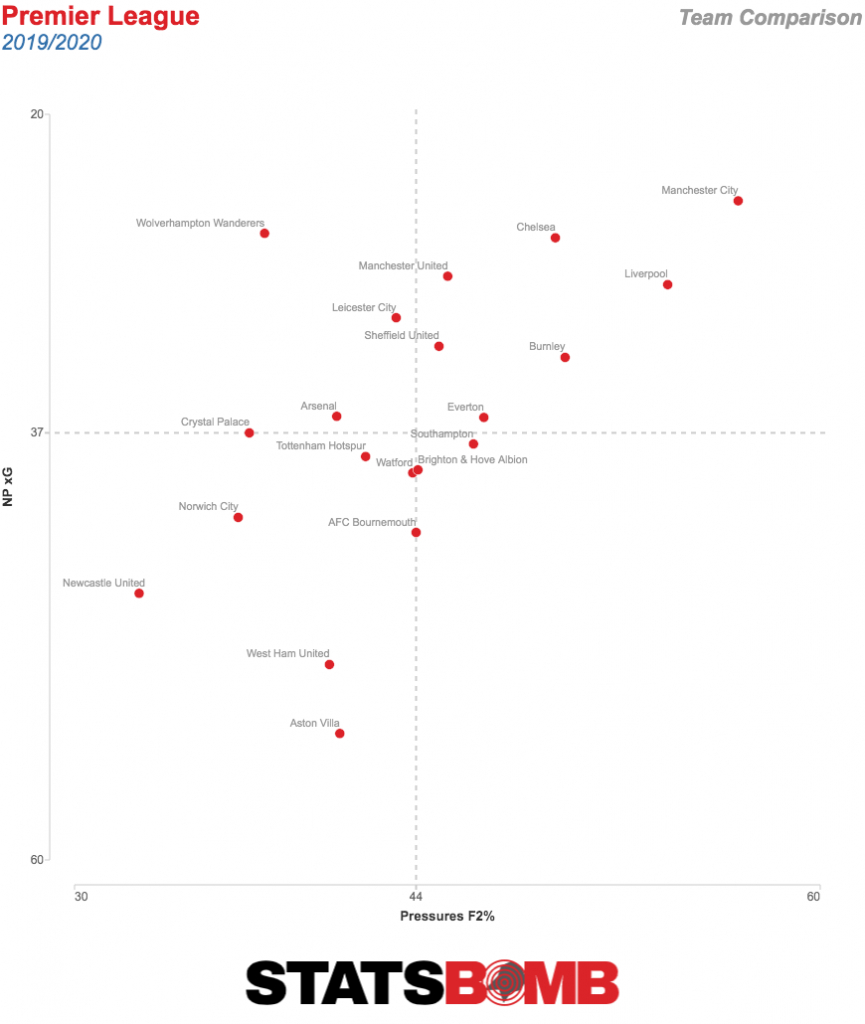

Man City still look like a middling pressing team, which obviously isn't what most people see with their eyes. They have so much possession that they're rarely having to make many pressures, which is the issue here. Raw numbers of pressures don't seem to tell us much of note. If we just look at the percentage of all pressures made in the opposing half, then guess what? City shoot up to the top of the table.  The obvious surprise towards the top here is Burnley. We all know at this point that Sean Dyche’s side do things differently, so it does make some sense to see them statistically stand out like this. At the bottom we have mostly less capable sides, but third placed Leicester sit in midtable. So do teams that defend high do a better job of it? Let’s compare this number to sides' xG conceded.

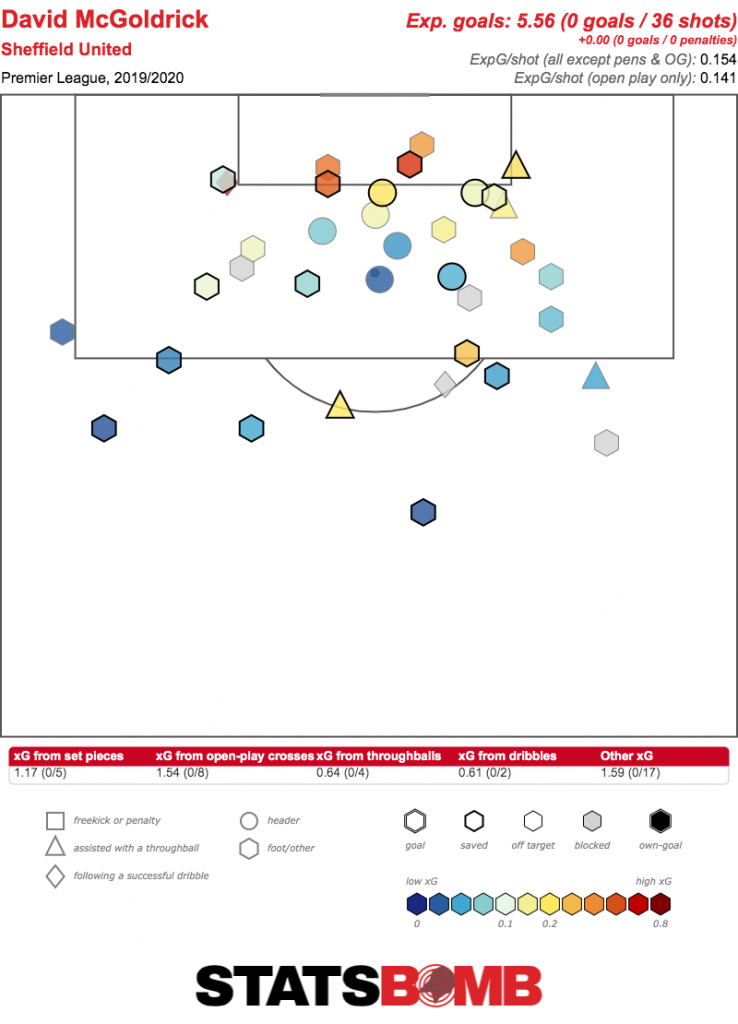

The obvious surprise towards the top here is Burnley. We all know at this point that Sean Dyche’s side do things differently, so it does make some sense to see them statistically stand out like this. At the bottom we have mostly less capable sides, but third placed Leicester sit in midtable. So do teams that defend high do a better job of it? Let’s compare this number to sides' xG conceded.  The obvious thing here is that the bottom right square is near empty. There isn't a team in the Premier League that offers an effective high press but just cannot defend at all. In terms of the sides that do actually defend well, there's a significant contrast. You have high pressers Man City and Liverpool, yes, but also a very solid Wolves outfit staying compact. The better sides do generally press more, but otherwise it isn't totally obvious that a particular pressing approach leads to better defending. David McGoldrick still can’t score goals Sorry, David. It feels mean at this point, but we can still gawk at your shot map one more time. Who knows, maybe your first attempt after football returns will go straight in the back of the net.

The obvious thing here is that the bottom right square is near empty. There isn't a team in the Premier League that offers an effective high press but just cannot defend at all. In terms of the sides that do actually defend well, there's a significant contrast. You have high pressers Man City and Liverpool, yes, but also a very solid Wolves outfit staying compact. The better sides do generally press more, but otherwise it isn't totally obvious that a particular pressing approach leads to better defending. David McGoldrick still can’t score goals Sorry, David. It feels mean at this point, but we can still gawk at your shot map one more time. Who knows, maybe your first attempt after football returns will go straight in the back of the net.  Next time, we’ll discuss some things we don’t know about the Premier League.

Next time, we’ll discuss some things we don’t know about the Premier League.

The StatsBomb Interviews: Ted Knutson Meets... Oliver Bartlett

Ted Knutson talks to Oliver Bartlett, a fitness coach who has worked with some of the biggest and best in football in a career that included Dortmund, Salzburg, Leverkusen and most recently to China.

Downloadable on the soundcloud link and also available on iTunes, subscribe HERE

RSS feed, if required, here

Also available on Spotify, Stitcher

Searching for a Replacement for Jadon Sancho

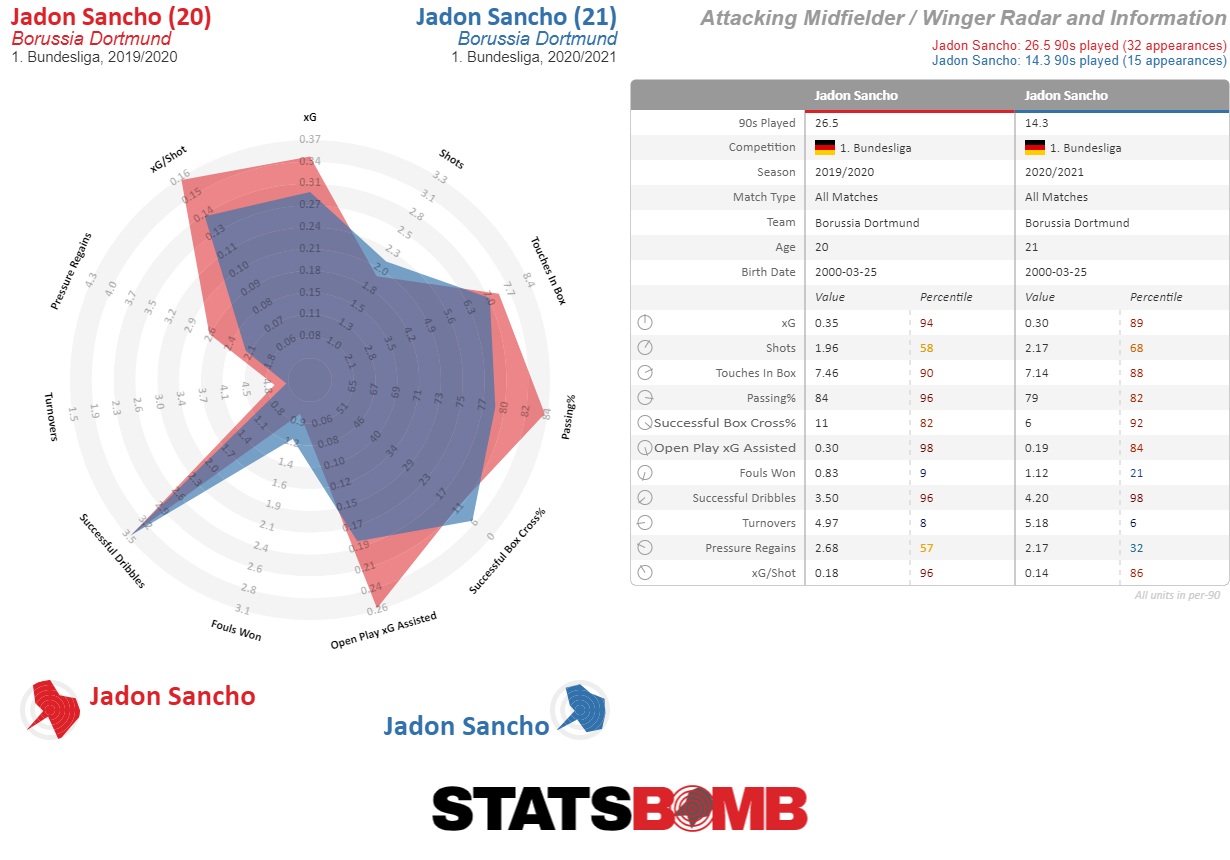

Football is in gridlock at the moment. Still, rest assured the football industry doesn't simply stop existing. Instead, clubs are already planning ahead for the time after the current standstill. Borussia Dortmund might have to do tackle that time without Jadon Sancho. The young Englishman could go back to his mother country and leave a large gap that has to be filled.

What defines Sancho?

Generally, the attributes of the 20 year old are well known. He has developed into one of the most promising wingers in Europe in short time. Sancho disposes of the classic qualities of a dribbler on the flanks: He's able to move into one-on-one-duels diagonally from the sideline, sprint toward the goal line or create gaps on the perimeter of his field of vision by moving towards the inside. Sancho is agile and skilful on the ball.

Moreover, his is a very aggressive playing style. His risk-management is oriented in such a way that he'll accept loss of possession with a view to a potential gain in attacking output. That's why he gives away the ball quite frequently, but also why he's usually taking aim from a good position for scoring opportunities. Altogether, he shows a relatively large presence in the penalty area. He doesn't just move on the flanks around the box, rather orientating his game towards getting into the dangerous zones.

In that, Sancho doesn't resemble someone like Franck Ribéry, who developed his danger on the goal mainly from the wing, rather he moves into positions in the half-space. Generally, Sancho's game from the half-space is somewhat underappreciated. From there, he usually interacts with other attacking players of Dortmund's – such as Marco Reus or Julian Brandt. He frequently looks for a short pass to Reus or, as of late, Erling Håland, in order to immediately move into a position for a flick-on or a lay-off. He moves faster than his opponents, who have to lose sight of him for only a split-second to no longer be in a position to step in.

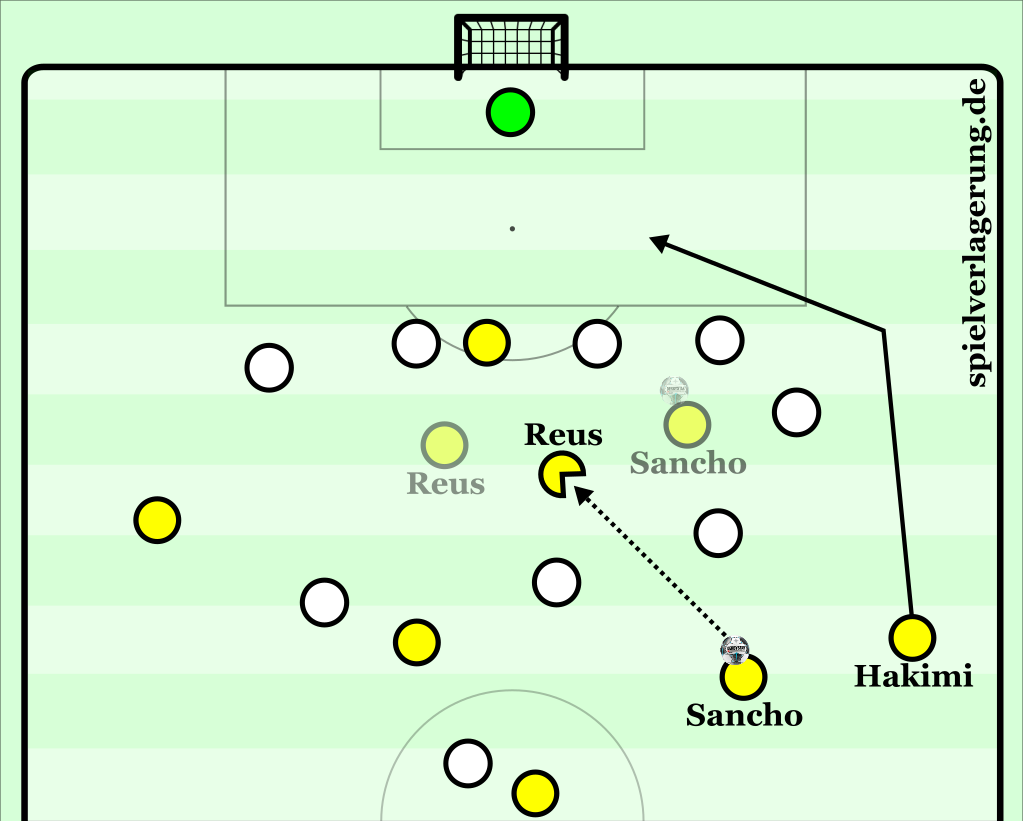

At BVB, Sancho functions so well also because he doesn't have to constantly run up and down the touchline. His work against the ball is rather sloppy and at times even clumsy. Longer runs without the option of getting to the middle diagonally are also not his strong suit. He's at his best in terms of sprinting when the team are running an open counter-attack. At Dortmund, Sancho is helped by the fact that he has flank-runners around him in Achraf Hakimi or Raphaël Guerreiro. Especially Hakimi, with his propensity to make runs behind the defensive line in the final third, fits well with Sancho's presence in the centre, since the focus will be on the Englishman, who can still serve up Hakimi through the gaps thanks to his agility.

Typical situation: Sancho attacks a defending side, that is backtracking, through the half-space. He draws the attention of the two outside defenders on his right, allowing Hakimi to make a run behind the backline.

What does the Replacement Need to Bring to the Table?

Going by the attributes discussed above, BVB should not just look for a strong dribbler on the wings. There are a few of those in the Bundesliga and other parts of Europe. But, especially in a 3-4-3, BVB don't necessarily need someone for the three-man attacking line who mostly feels at home on the flank. That's what strong runners on the wing-back positions, such as Hakimi, Guerreiro and Nico Schulz are there for. The potential signing of Thomas Meunier further highlights how Dortmund will upgrade in that regard.

For this, we can use a "Similar Player Search" tool to analyse which Bundesliga players resemble Sancho during the current campaign. In that, we'll weight which values should factor into the comparison especially strongly and receive a number of interesting names in the category of players of up to 22 years of age who have played a minimum amount of 600 minutes – each with a percentage-wise correlation to Sancho. In declining order of correlation these are: Marcus Thuram, Christopher Nkunku, Kai Havertz, Dodi Lukebakio, Moussa Diaby, Josip Brekalo, Ruben Vargas, Amine Harit, Leon Bailey, Alphonso Davies, Marco Richter, Christoph Baumgartner, Rabbi Matondo, Javairô Dilrosun and Ismail Jakobs. Naturally, a number of candidates can be discarded for obvious reasons. Or does anyone think Davies will soon lace his boots for BVB? At the same time, we can highlight three interesting players.

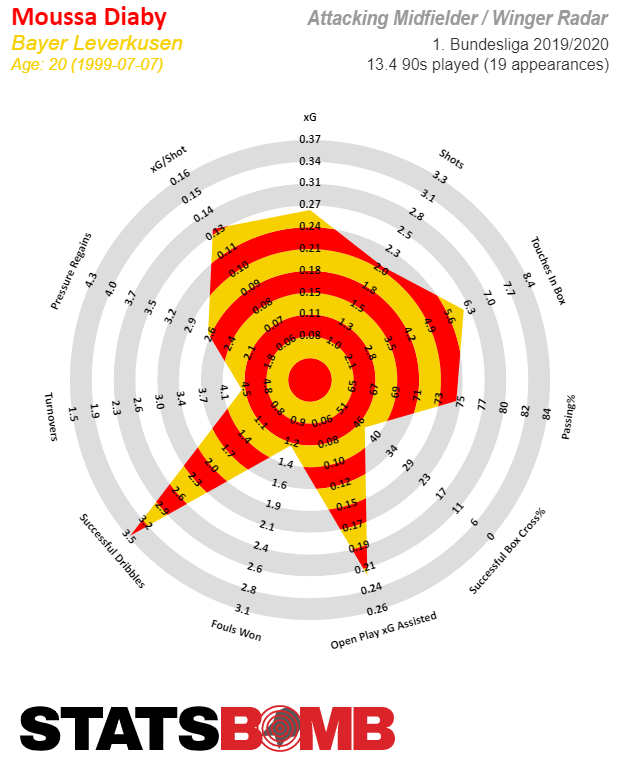

Candidate 1: Moussa Diaby

I might have suggested Diaby as a fairly obvious option without looking at stats. The Bayer Leverkusen wingman is not yet as consistently successful in his actions as Sancho – particularly in the opponent's box – but he combines agility and skill on the ball with a clear push towards the goal. An added benefit is that he's not being used as a clear-cut winger in Peter Bosz's system, rather having the freedom or even task of positioning himself in the half-space or playing into these zones. Diaby doesn't just attack defensive lines from the flank, but also penetrates them in positional gaps. With that, he could fit into Lucien Favre's system well. There shouldn't be any doubts concerning his general footballing and athletic qualities at any rate.

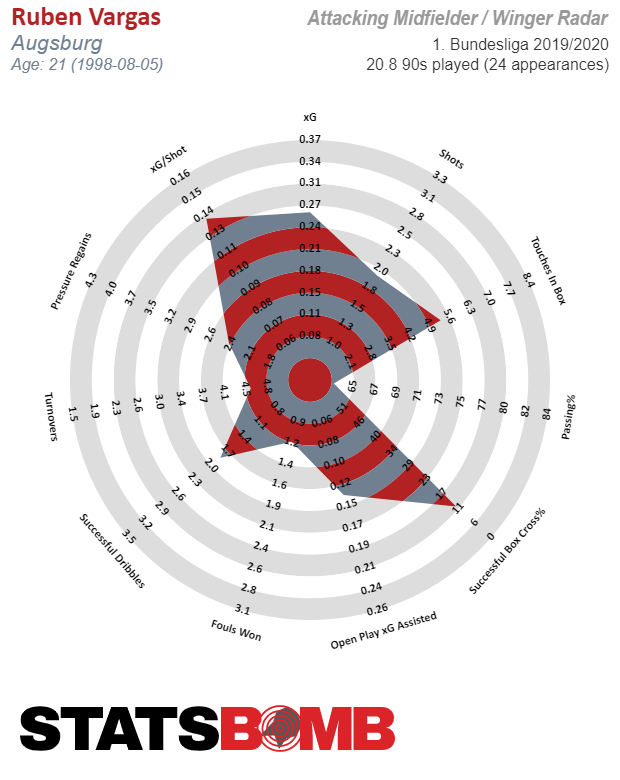

Candidate 2: Ruben Vargas

Vargas of FC Augsburg is harder to judge than Diaby seeing as he can profit from his team's playing style only to a limited extent at the moment. FCA is one of the Bundesliga teams with a small amount of attacking productivity in terms of shots on goal. Vargas can hardly change that situation by himself, but maybe he doesn't have to. For especially in the transitional game, he develops a respectable penetrating power in spite of it all, which is clear to see even in isolated situations. Because of that, the motto when talking about Vargas has to be: If someone can have so much attacking presence while playing in weaker surroundings, they surely must shine all the more with better teammates. The pitfall here is that there might be an error in reasoning. Because Vargas does also profit from Augsburg's transitional football, in that he has more freedoms and only rarely has to successfully convert detailed actions. Vargas is a candidate that makes it obvious how it's not so easy to judge a player's performances in relation to the quality of his team and in the context of a potentially different playing style in the future.

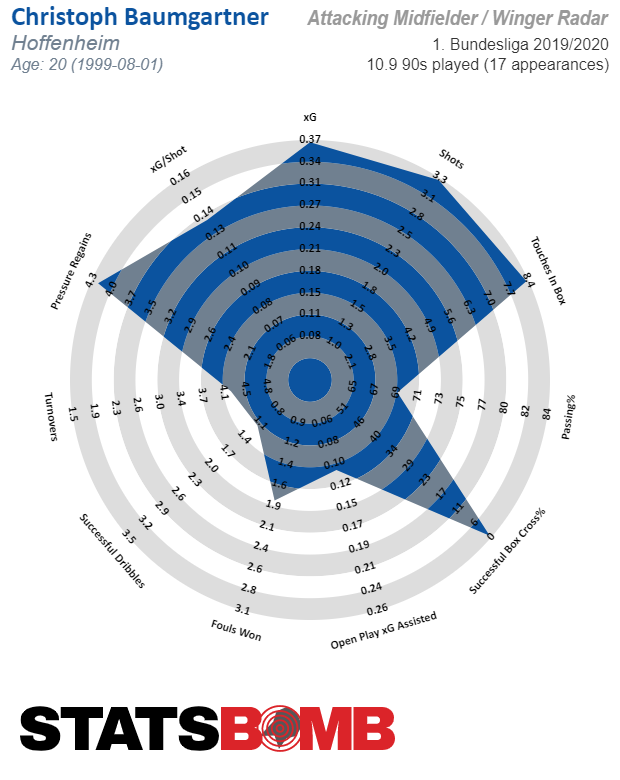

Candidate 3: Christoph Baumgartner

The mention of this 20-year-old TSG Hoffenheim player may come as somewhat of a surprise. Baumgartner is widely regarded as the biggest talent in the Bundesliga squad of the team from the Kraichgau in south-west Germany. However, he was handed round from position to position this season – very much in keeping with the style of head coach Alfred Schreuder. Between right-sided wing-back and left-sided supporting striker, he's played in almost every position already. Baumgartner, in any case, is a player who shines brightest as a No. 10 or as an attacking winger. His aggressive and at the same time agile playing style in the final third somewhat resembles Sancho's in some aspects. Of course, Baumgartner doesn't have that special something while dribbling whatsoever. Should Dortmund be looking for a young candidate, however, who can factor into the plans both as a disguised winger and a potential back-up for Reus, Baumgartner could become a possibility. Similarly to Sancho one and a half years ago, Baumgartner is still a bit inconsistent in his decision-making. Still, the appearances he's made in the Bundesliga have shown in time that he's developing rapidly.

Whoever Dortmund sign after Sancho, it won't be an equivalent replacement from day one, but rather someone with the required potential to in his way shape BVB's attack in the short- and especially medium-term. That was already the case with Sancho. And that turned out to be a lucrative model for Dortmund both in sporting and monetary terms.

StatsBomb LIVE Podcast: The 2021 Contracts. Stick or Twist?

The StatsBomb Interviews! Ted Knutson meets... Gab Marcotti

StatsBomb LIVE Podcast April 2020 #2, Data Scouting Smaller Leagues & Michael Bay

Classic Game Rewind: Tottenham Hotspur 4–1 Liverpool, October 2017

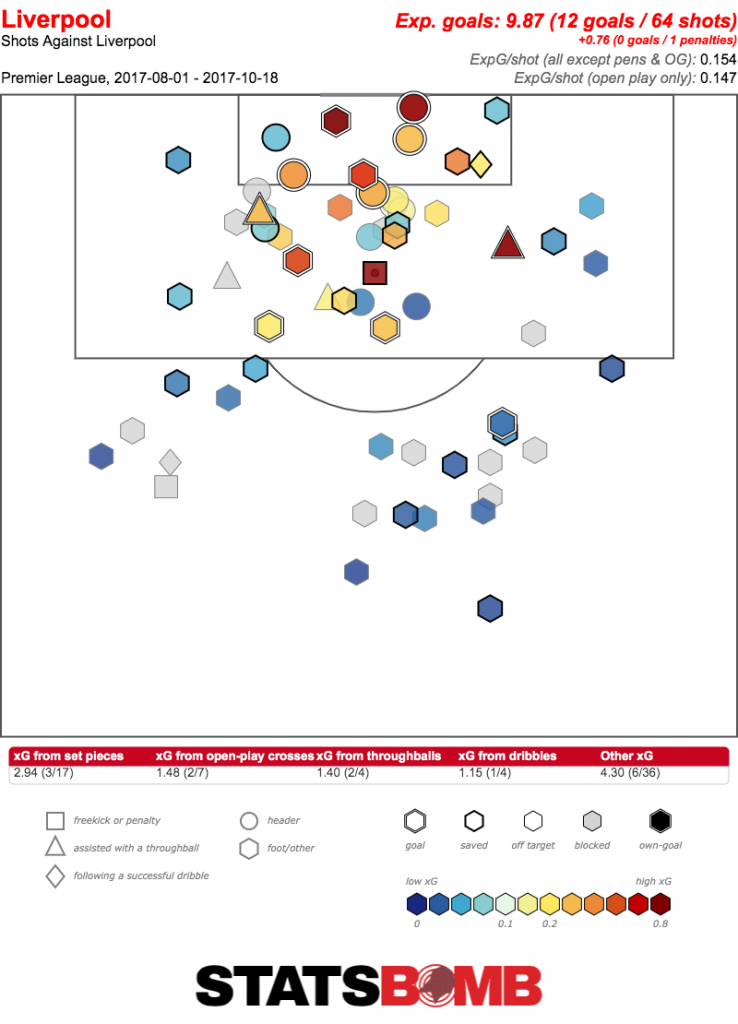

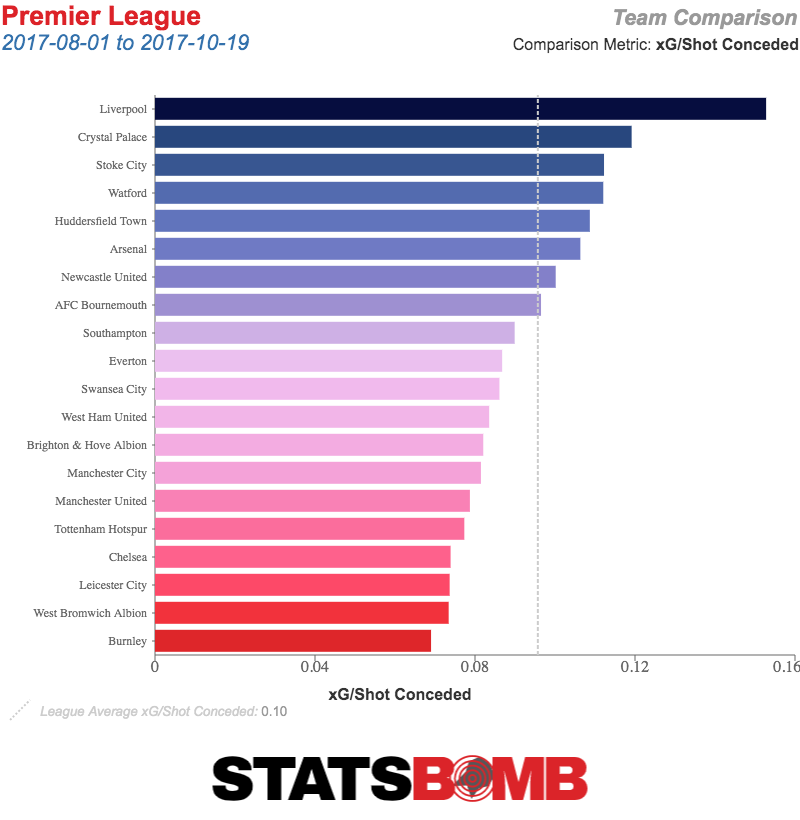

Sometimes football provides us with sliding doors moments. Sometimes it provides us with moments that change the trajectory of both clubs for years to come. Sometimes it provides us with moments that feel like they perfectly capture both teams at the time, but in later years look very strange in hindsight. When Tottenham Hostpur embarrassed Liverpool with a 4–1 win in October 2017, it only came as a mild surprise. See, back in the ancient period known as two-and-a-half years ago, Jürgen Klopp’s side were a bit flaky. The principles of the good play we’ve seen since were in place, but the Reds had an incredible talent to shoot themselves in the foot by giving up a select few high-quality chances. Liverpool would be great for most of the game, but when a team broke them open, they really broke them open. Here are the shots conceded in the eight games of the 2017–18 season they played before facing Tottenham.  If that expected goals per shot doesn’t scream danger on the surface, let’s put it into context by examining the xG conceded of the entire league at this point.

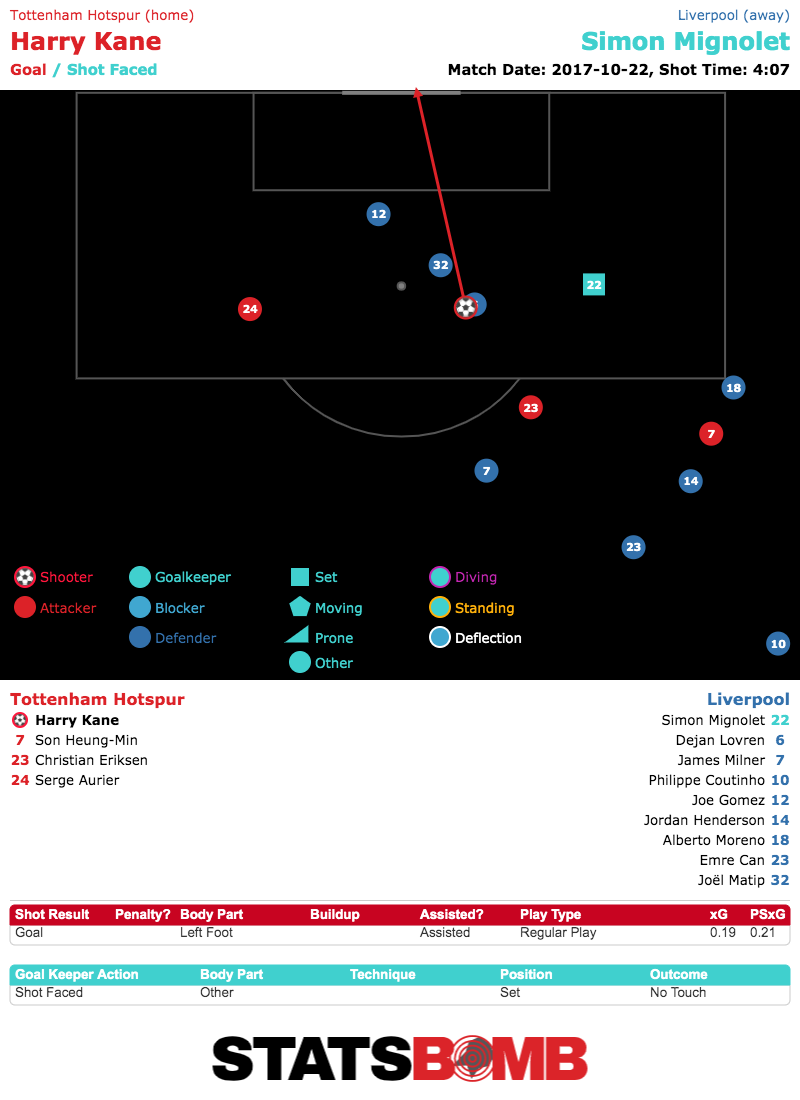

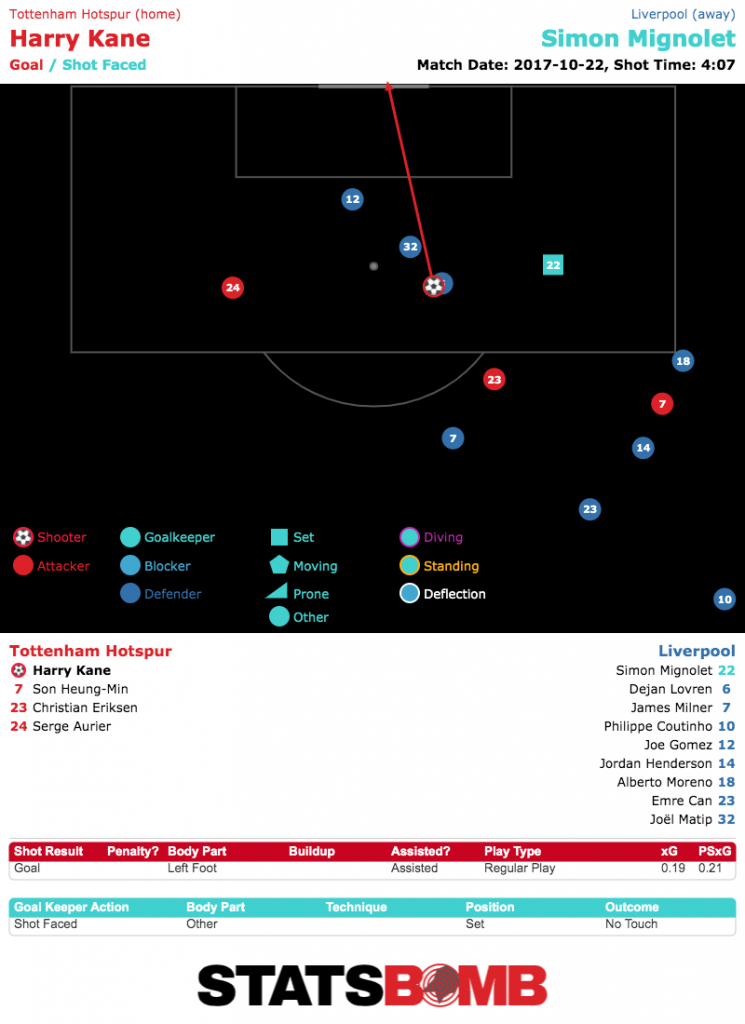

If that expected goals per shot doesn’t scream danger on the surface, let’s put it into context by examining the xG conceded of the entire league at this point.  Yeah. The average chance Liverpool conceded was — by a decent margin — worse than those faced by any other team in the league. Yikes. Thus it wasn’t a huge surprise to see Spurs carve Liverpool up and score with their first two shots. The first saw Harry Kane react much quicker than all of Liverpool’s defenders and Simon Mignolet, earning himself a pretty decent angle with the goalkeeper in no man’s land.

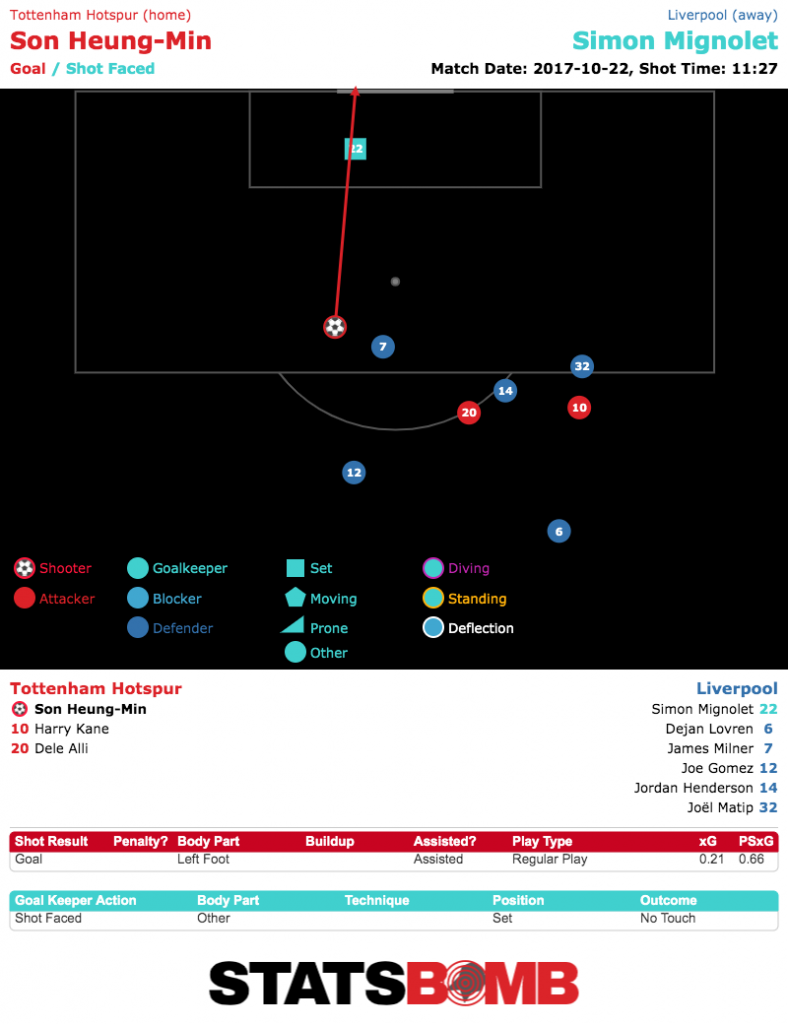

Yeah. The average chance Liverpool conceded was — by a decent margin — worse than those faced by any other team in the league. Yikes. Thus it wasn’t a huge surprise to see Spurs carve Liverpool up and score with their first two shots. The first saw Harry Kane react much quicker than all of Liverpool’s defenders and Simon Mignolet, earning himself a pretty decent angle with the goalkeeper in no man’s land.  Kane outthought Liverpool’s backline again all of seven minutes later, this time catching the side out on a counter and playing in Son Heung-min for the finish. Neither of these goals really came from Mauricio Pochettino’s plan in possession. The action developed in transition moments, with Liverpool caught totally disorganised and 2–0 down before even registering a shot.

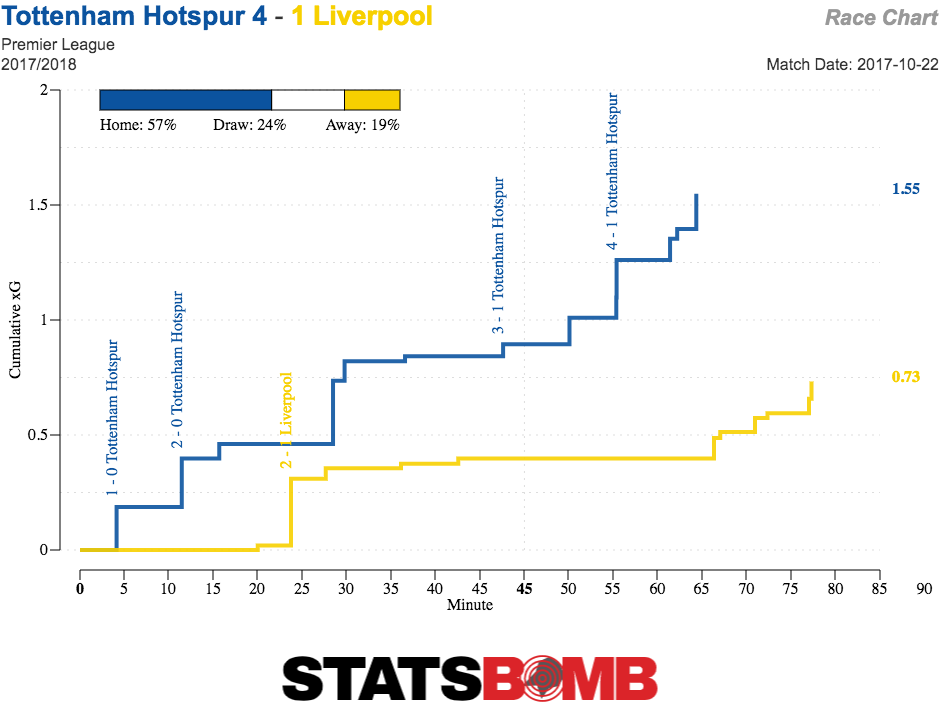

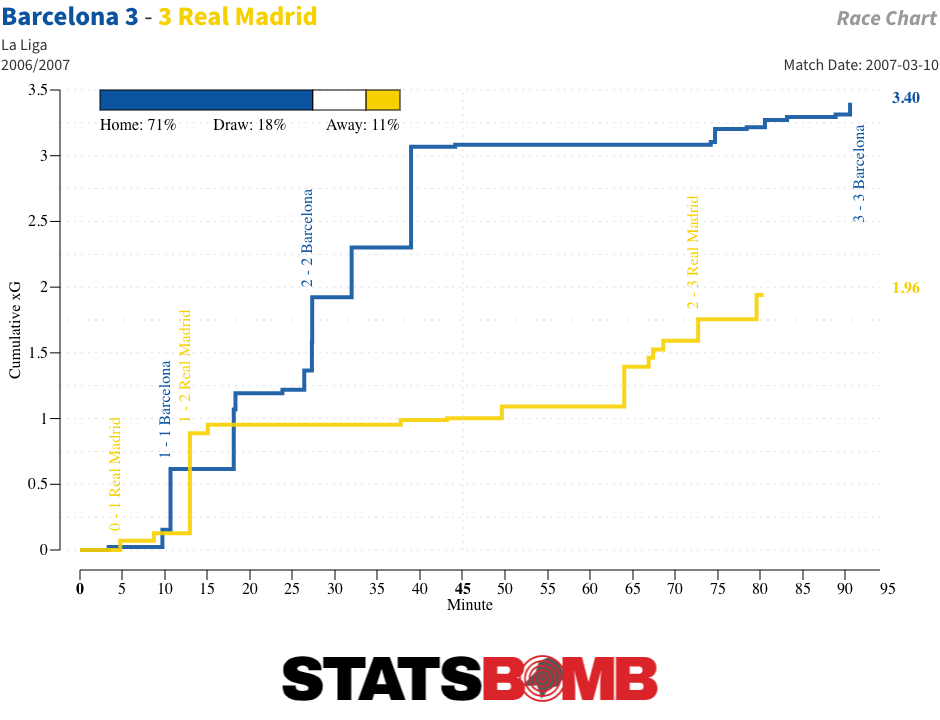

Kane outthought Liverpool’s backline again all of seven minutes later, this time catching the side out on a counter and playing in Son Heung-min for the finish. Neither of these goals really came from Mauricio Pochettino’s plan in possession. The action developed in transition moments, with Liverpool caught totally disorganised and 2–0 down before even registering a shot.  The race chart tells the story for the rest of the game. Liverpool had all of one good chance in the first half, which Mohamed Salah dutifully put away, but otherwise didn’t get going until they were already 4–1 down. Spurs came in waves, never feeling like they were dominating in terms of sustained periods but always landing the knockout punch.

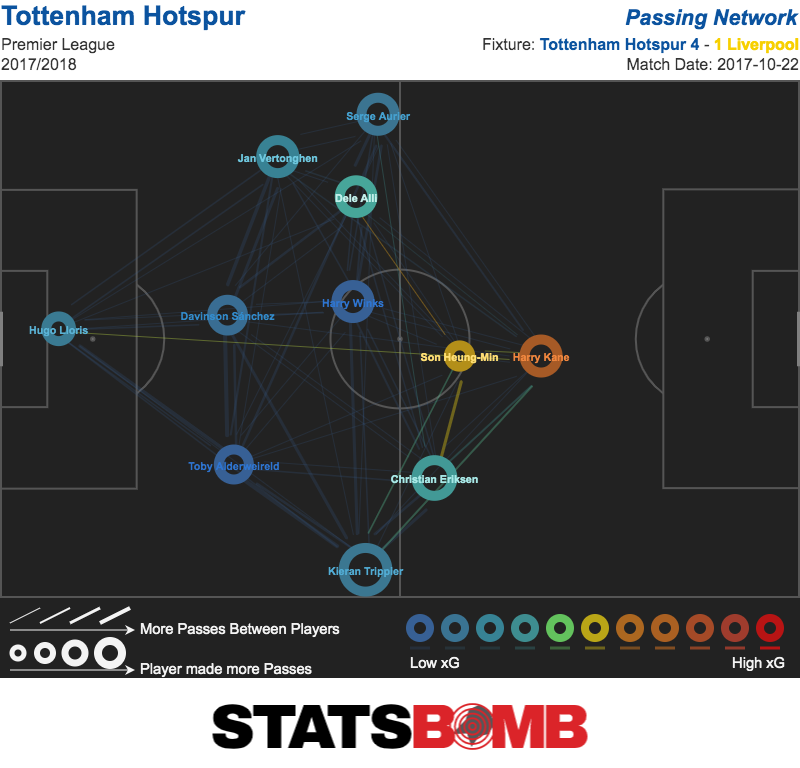

The race chart tells the story for the rest of the game. Liverpool had all of one good chance in the first half, which Mohamed Salah dutifully put away, but otherwise didn’t get going until they were already 4–1 down. Spurs came in waves, never feeling like they were dominating in terms of sustained periods but always landing the knockout punch.  Their choice to play like this might have actually been enforced. Pochettino’s football at its best was always about pressing high and working good opportunities in possession. This game didn't show that. The key selection issue was Mousa Dembélé’s injury. The Belgian's out-of-this-world ability to evade pressure while moving the ball through midfield made him irreplaceable for Spurs’ Plan A. It’s not a coincidence that Tottenham have declined since he left North London. But his absence meant that Pochettino didn’t even try to control the game with the ball. Instead, he trusted that Liverpool’s concentration lapses would be enough to move to a purely reactive game plan. Spurs were able to win the game not through tactical ideas or talented players, but simply by being more switched on in moments of transition.

Their choice to play like this might have actually been enforced. Pochettino’s football at its best was always about pressing high and working good opportunities in possession. This game didn't show that. The key selection issue was Mousa Dembélé’s injury. The Belgian's out-of-this-world ability to evade pressure while moving the ball through midfield made him irreplaceable for Spurs’ Plan A. It’s not a coincidence that Tottenham have declined since he left North London. But his absence meant that Pochettino didn’t even try to control the game with the ball. Instead, he trusted that Liverpool’s concentration lapses would be enough to move to a purely reactive game plan. Spurs were able to win the game not through tactical ideas or talented players, but simply by being more switched on in moments of transition.  I’ve not been the kindest to Kane in the past, so it’s worth highlighting just how good he was here. He was mostly playing on the shoulder of the defenders and managed to be quicker than all of them to just about everything. This would make sense for Sergio Agüero or Jamie Vardy, but Kane isn’t especially fast. He just thought quicker than Dejan Lovren, Joël Matip and Joe Gomez. They were forced to react to things he had already done a split second ago. Lovren in particular was poor enough to be substituted after half an hour for Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain. This sounds like an extreme move, but in practice it was just Gomez moving to centre back as Emre Can shuffled over to right back, with Philippe Coutinho coming into central midfield and Oxlade-Chamberlain on the left of the front three. If it sounds like chaos, it was. Clearly, after this game Liverpool became exceedingly organised. Since then, the Reds have won 75 of the 96 league matches played, with a fairly ridiculous 2.5 points per game over such a long period. Their backbone is now strong. Of the goalkeeper and back four that started against Spurs, only Joe Gomez would now be expected to start such a big game. And he now plays a different position, with Trent Alexander-Arnold established as the undroppable right back. Salah and Roberto Firmino both started in attack here, but they were joined by Philippe Coutinho rather than Sadio Mané. Coutinho’s talent is obvious, but he’s much more of an individual than Mané, making the side less tactically coherent. This was a rough sketch of a Liverpool side that has since become worth hanging in the Louvre. For Tottenham, however, the game was something of the beginning of the end. As discussed, Dembélé was unavailable here, prompting a switch in strategy. The more reactive Spurs were able to pull off a few good results in one-off games, with the run to the Champions League final likely to be remembered for a long time. But they couldn’t produce consistent league results. As seen on the xG trendlines below, both the attack and defence cratered. This can’t be put down purely to the system, as players’ personal frustration with Pochettino was also an undeniable piece of the puzzle. But this confluence of factors brought a golden era of Tottenham to a fairly abrupt end.

I’ve not been the kindest to Kane in the past, so it’s worth highlighting just how good he was here. He was mostly playing on the shoulder of the defenders and managed to be quicker than all of them to just about everything. This would make sense for Sergio Agüero or Jamie Vardy, but Kane isn’t especially fast. He just thought quicker than Dejan Lovren, Joël Matip and Joe Gomez. They were forced to react to things he had already done a split second ago. Lovren in particular was poor enough to be substituted after half an hour for Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain. This sounds like an extreme move, but in practice it was just Gomez moving to centre back as Emre Can shuffled over to right back, with Philippe Coutinho coming into central midfield and Oxlade-Chamberlain on the left of the front three. If it sounds like chaos, it was. Clearly, after this game Liverpool became exceedingly organised. Since then, the Reds have won 75 of the 96 league matches played, with a fairly ridiculous 2.5 points per game over such a long period. Their backbone is now strong. Of the goalkeeper and back four that started against Spurs, only Joe Gomez would now be expected to start such a big game. And he now plays a different position, with Trent Alexander-Arnold established as the undroppable right back. Salah and Roberto Firmino both started in attack here, but they were joined by Philippe Coutinho rather than Sadio Mané. Coutinho’s talent is obvious, but he’s much more of an individual than Mané, making the side less tactically coherent. This was a rough sketch of a Liverpool side that has since become worth hanging in the Louvre. For Tottenham, however, the game was something of the beginning of the end. As discussed, Dembélé was unavailable here, prompting a switch in strategy. The more reactive Spurs were able to pull off a few good results in one-off games, with the run to the Champions League final likely to be remembered for a long time. But they couldn’t produce consistent league results. As seen on the xG trendlines below, both the attack and defence cratered. This can’t be put down purely to the system, as players’ personal frustration with Pochettino was also an undeniable piece of the puzzle. But this confluence of factors brought a golden era of Tottenham to a fairly abrupt end.  Will Liverpool suffer the same fate in the years to come? It’s not out of the question. Most of the Reds’ key players are in their late twenties, and only a small drop off from several of them could have a snowball effect. The club’s excellent record in the transfer market in recent years could be tested to the limit as the side will have to rebuild faster than most fans likely assume. Liverpool do have a plan, and they can avoid this fate. But Spurs should be a pertinent example for what the club must avoid in order to continue to dominate.

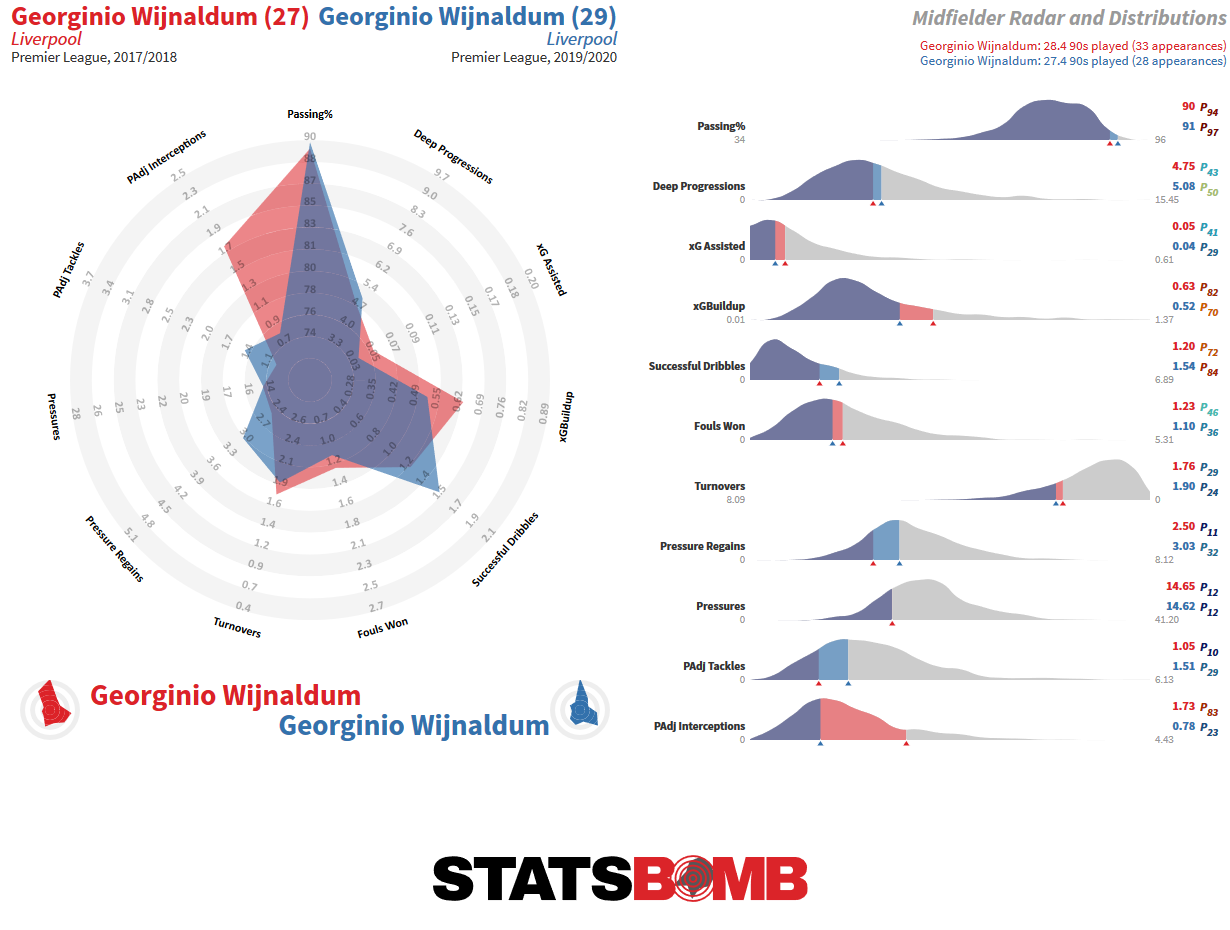

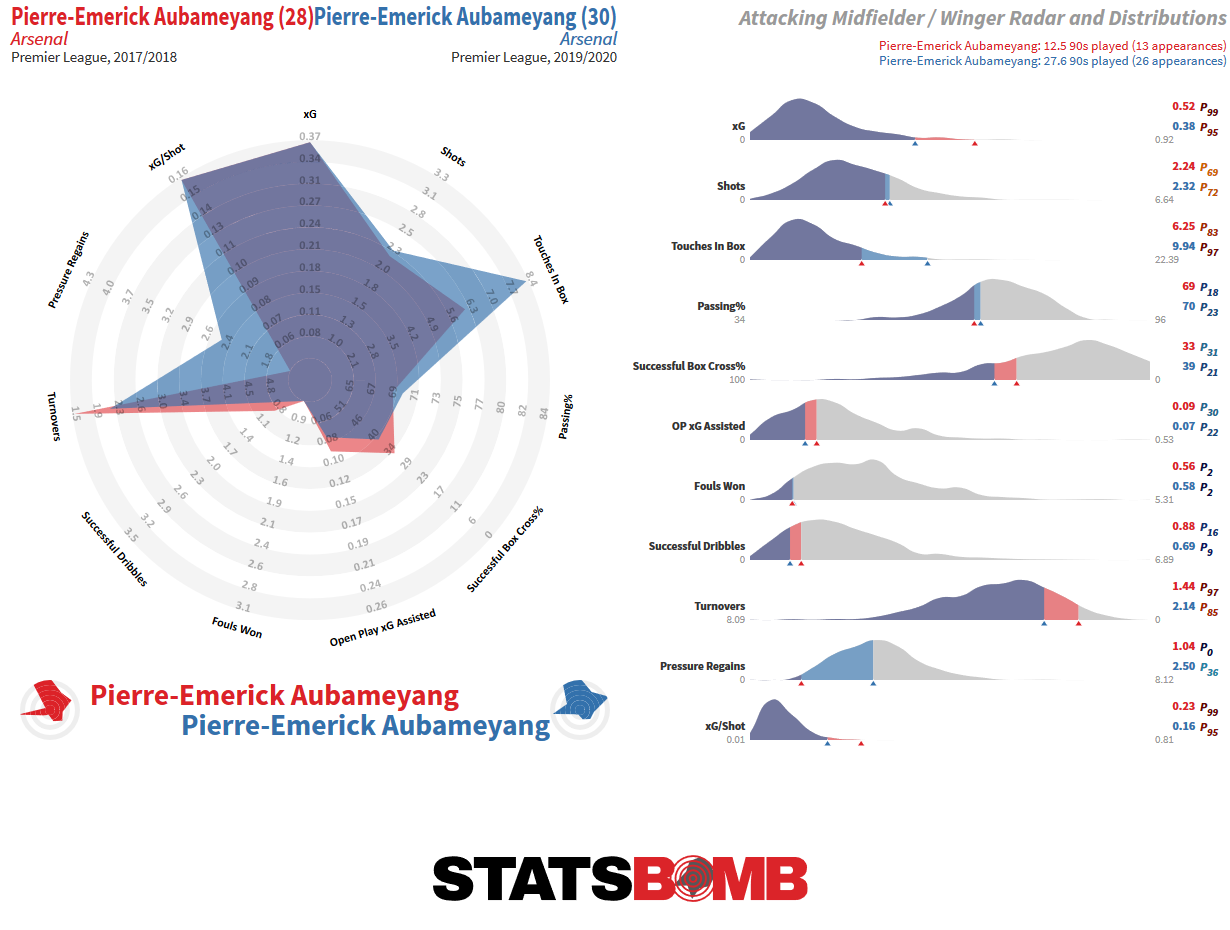

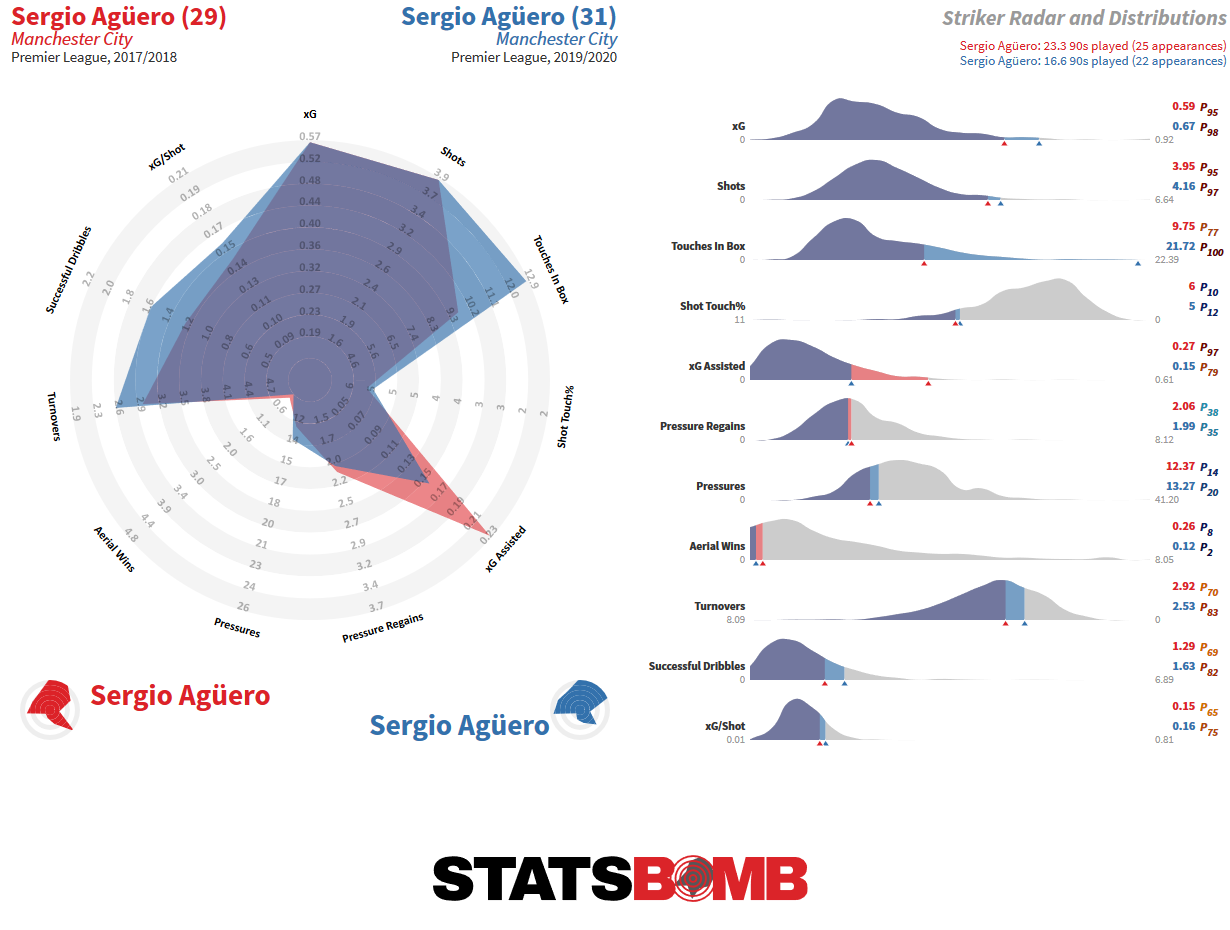

Will Liverpool suffer the same fate in the years to come? It’s not out of the question. Most of the Reds’ key players are in their late twenties, and only a small drop off from several of them could have a snowball effect. The club’s excellent record in the transfer market in recent years could be tested to the limit as the side will have to rebuild faster than most fans likely assume. Liverpool do have a plan, and they can avoid this fate. But Spurs should be a pertinent example for what the club must avoid in order to continue to dominate.

StatsBomb LIVE Podcast April 2020 #1: Q & A

Messi Moments with Álex Delmás: Barcelona 3-3 Real Madrid, March 2007

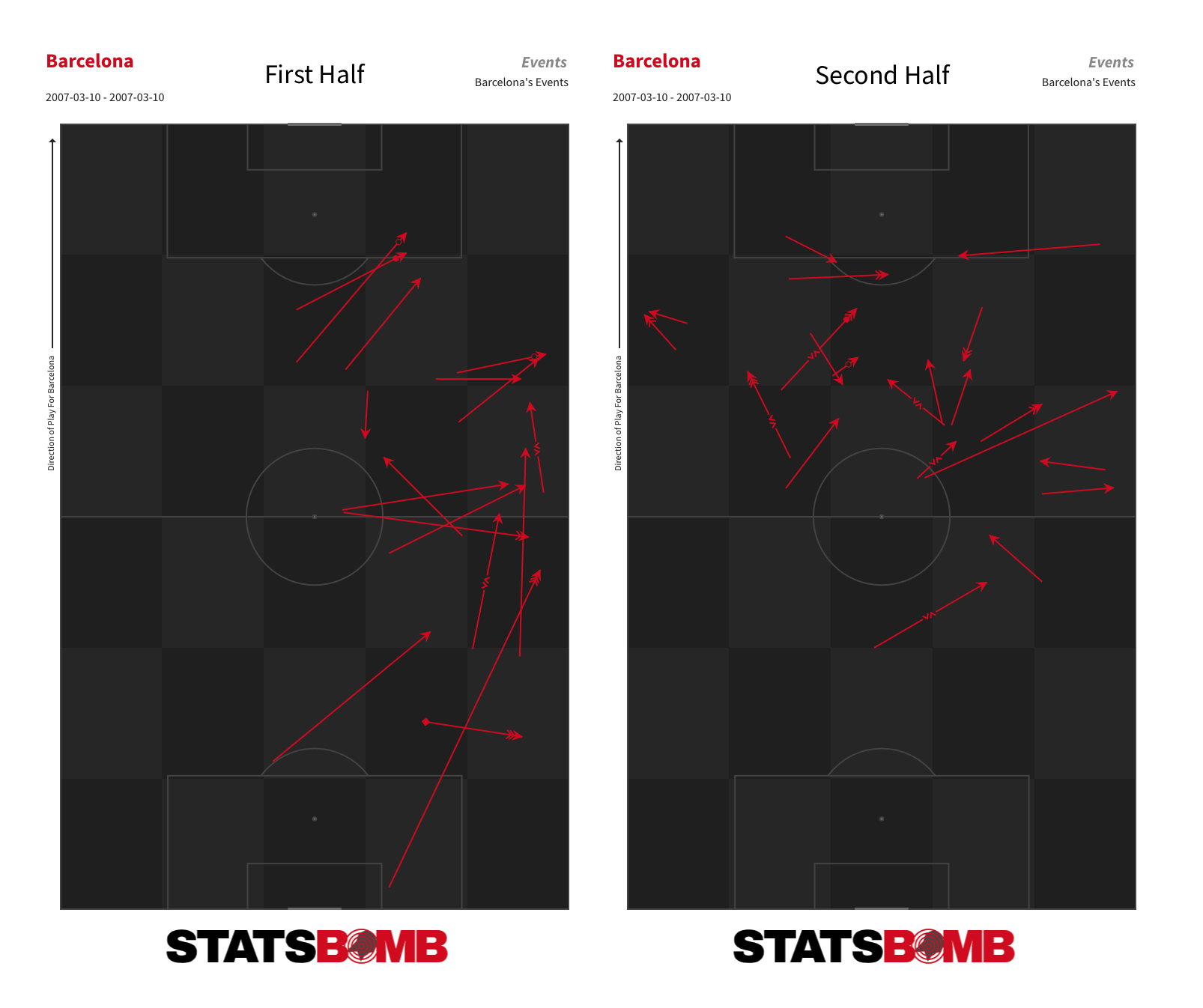

With football at a standstill, we’re going to take advantage of the pause to analyse the evolution of one of the best players in the history of our sport: Lionel Messi. And who better to assist us in that task than Álex Delmás, ex-footballer, analyst for Barça TV and La Vanguardia newspaper, and author of the book Messi Táctico. Thanks to our Messi Data Biography we have data for all league matches involving Messi since his debut in 2004. For this series, Álex has picked three significant matches in Messi’s evolution as a footballer. We start with a Clásico: the 3–3 between Barcelona and Real Madrid in March 2007. Nick Dorrington (ND) (editor of StatsBomb's Spanish-language site): Hi Álex. For those who don’t already know you, it’s worth mentioning that you haven’t just followed Messi’s career from afar. I understand that you once shared a pitch with him? Álex Delmás (AD): That’s right. I’m an ex-footballer. I played in Segunda B with Sabadell and Premiá, and ended my career as the captain of CE Europa, the third club in Barcelona. I developed at Granollers, a Barça affiliate, and I spent a short time in the juvenil age group at Barça. I came up against Messi there, and then in 2004, I received an award alongside him. I was voted the best player in the Tercera División, and he was voted the most promising young player. From then on, I took a close interest in his career. ND: Okay, we’re going to start with this Clásico, a 3–3 draw at the Camp Nou. This is Messi’s second full season in the first team, one in which he more than doubled his number of minutes from the previous campaign. Why have you chosen this match? AD: There have been various iterations of Messi. In this match, he was clearly in his first iteration, and that is why I chose it. It's his first great performance, his first hat-trick and a match that in a sense marked the beginning of his shift from being just one more player to Barça’s most decisive performer. In this first iteration, he was more of a moments player than one who was consistently involved. He was thrilling every time he got on the ball, but he was a bit more timid and held his position more than the Messi we would see later on. ND: Before focusing specifically on Messi, let’s talk a bit about the match itself and Barcelona’s approach. Madrid utilised a pretty narrow 4-2-3-1 formation. How did Barça line up? AD: Barça surprised with a very aggressive 3-4-3 that included a defence made up of two central defenders and a full-back: Oleguer, Lilian Thuram and Carles Puyol. ND: It really was a surprise. At least in the matches that Messi took part in, Barça had only used that formation once before, in a 1–0 loss away to Real Zaragoza, and they never used it again, as we can see from this animation of their pass maps for the season.

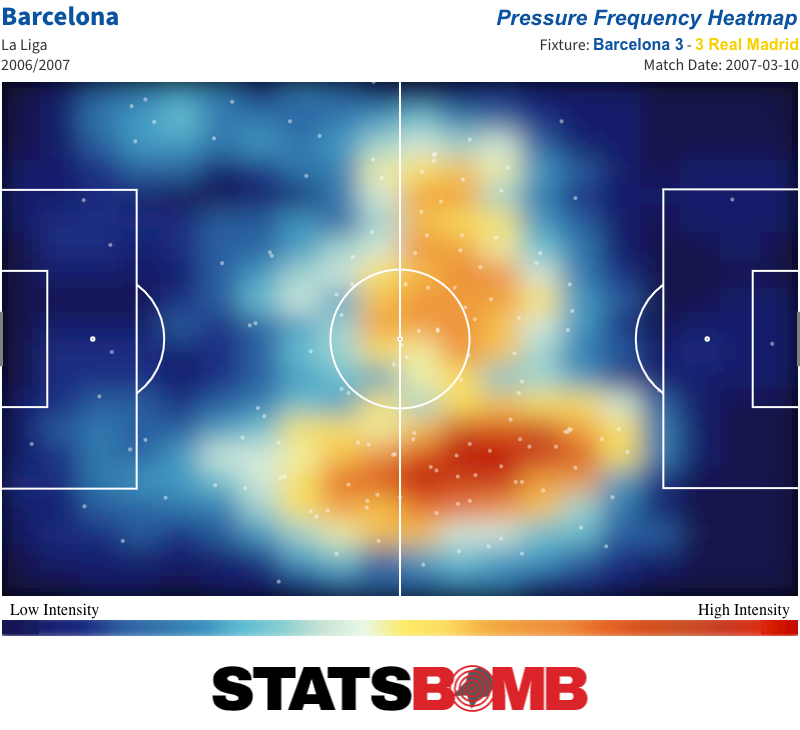

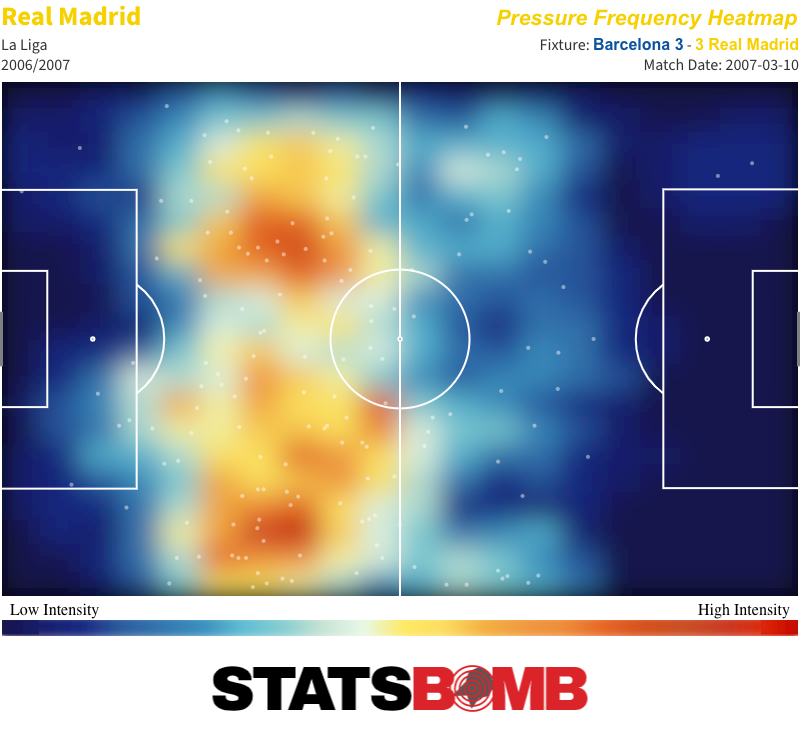

AD: It’s true. It was a very open match . . . a lot of back and forth, in part because neither of the teams pressed well. Barcelona had more players high up the pitch, but Madrid were able to find routes forward down the flanks in the midfield zone, just behind Barça’s wingers. Madrid also tried to get Ruud van Nistelrooy in behind a lot. Mainly off the back of Thuram. It’s also worth noting that Barça were left with 10 men after the dismissal of Oleguer. Their search for an equaliser opened things up even more in the second half. ND: We can clearly see that difference in how high the two teams pressed in their pressure maps from this match.

AD: It’s true. It was a very open match . . . a lot of back and forth, in part because neither of the teams pressed well. Barcelona had more players high up the pitch, but Madrid were able to find routes forward down the flanks in the midfield zone, just behind Barça’s wingers. Madrid also tried to get Ruud van Nistelrooy in behind a lot. Mainly off the back of Thuram. It’s also worth noting that Barça were left with 10 men after the dismissal of Oleguer. Their search for an equaliser opened things up even more in the second half. ND: We can clearly see that difference in how high the two teams pressed in their pressure maps from this match.

As you mentioned before, at this stage of his career Messi played very wide on the right, and in this match Barcelona's attack was quite asymmetrical. There were a lot of players toward the left and only really Messi holding width on the right. It was surprising to see the amount of space that Messi had to receive in behind Madrid’s left-back Miguel Torres, both on the first goal and on other occasions during the first half. Do you think it was an approach designed to exploit a certain weakness in the Madrid defence or was it just the result of the natural game of Deco, Iniesta, Ronaldinho and Samuel Eto’o, all of whom preferred to receive towards the left? AD: Ronaldinho started on the left, with Eto’o in the centre, but they quickly started to interchange positions. There were moments when Ronaldinho played as the #9 and Eto’o went wide on the left. The central midfielders did tend to drift towards the left. I don’t think it was an approach put in place specifically for this match but just a product of the magnetism of Ronaldinho. At that time Ronnie was the star of the team and the primary creator. It was the first stage of Messi’s career, when he was still much more of a winger than a second striker. One of the secrets of Messi’s goals in this match was that he understood the need to hold a wide position. In doing so, he created passing lanes for a number of dangerous attacks. ND: That was how the first of Messi’s three goals arrived. He received a crisp pass from Eto’o and fired home his first goal in a Clásico. His second came from a rebound inside the area, again with him as the most far right of all attacking players. But then Oleguer’s dismissal, after a second yellow card for a needless foul on Fernando Gago, right at the end of the first half, provoked a change both in Barça’s shape and Messi’s position within it. AD: Yes, the sending off completely changed things for the second half. Barça brought on Sylvinho for Eto’o and settled into a 3-4-2, with Messi and Ronaldinho together up front. Messi started to receive the ball much more often in central areas. ND: We can see that by looking at the positions in which Messi received the ball in the first half compared to the second.

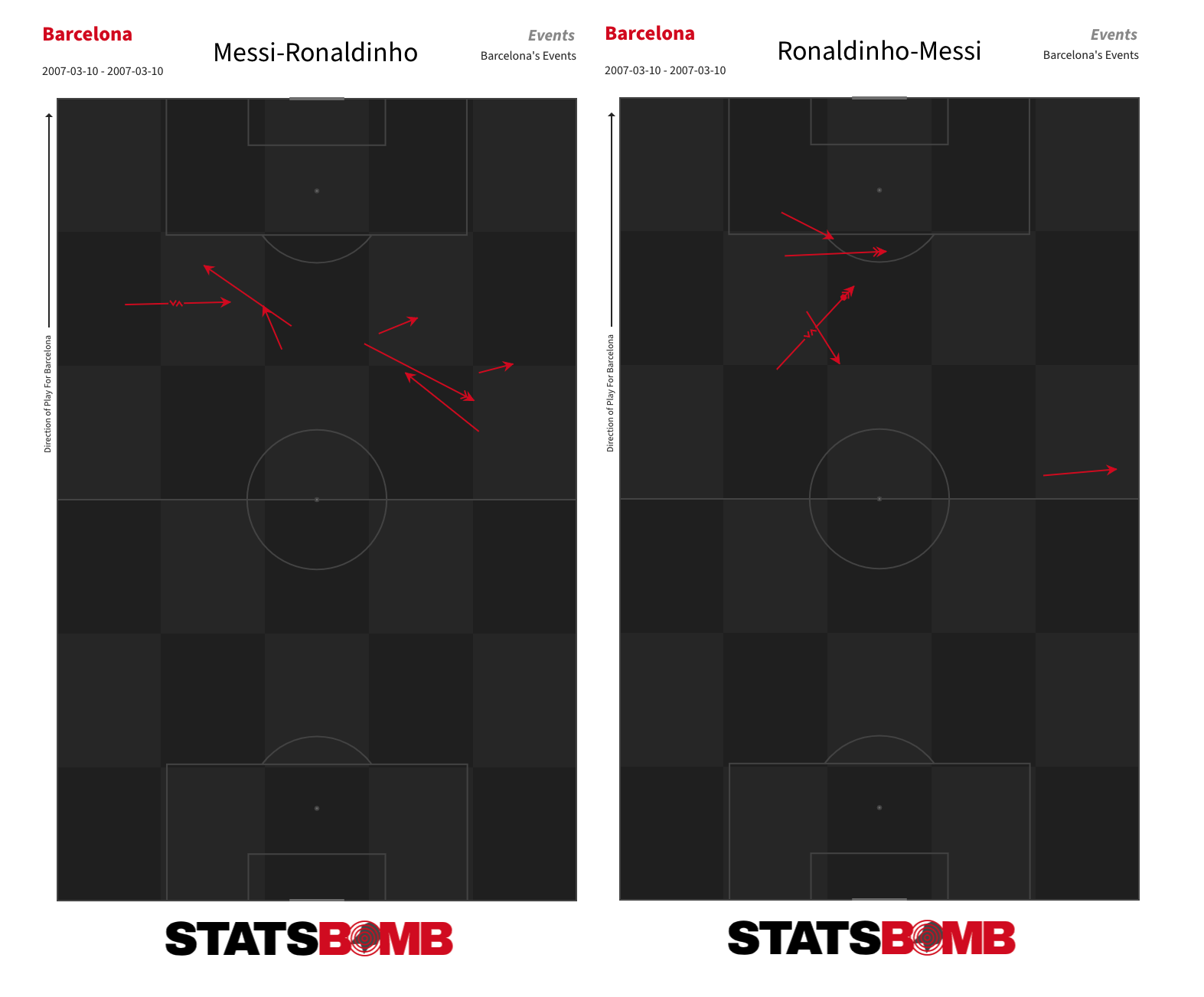

As you mentioned before, at this stage of his career Messi played very wide on the right, and in this match Barcelona's attack was quite asymmetrical. There were a lot of players toward the left and only really Messi holding width on the right. It was surprising to see the amount of space that Messi had to receive in behind Madrid’s left-back Miguel Torres, both on the first goal and on other occasions during the first half. Do you think it was an approach designed to exploit a certain weakness in the Madrid defence or was it just the result of the natural game of Deco, Iniesta, Ronaldinho and Samuel Eto’o, all of whom preferred to receive towards the left? AD: Ronaldinho started on the left, with Eto’o in the centre, but they quickly started to interchange positions. There were moments when Ronaldinho played as the #9 and Eto’o went wide on the left. The central midfielders did tend to drift towards the left. I don’t think it was an approach put in place specifically for this match but just a product of the magnetism of Ronaldinho. At that time Ronnie was the star of the team and the primary creator. It was the first stage of Messi’s career, when he was still much more of a winger than a second striker. One of the secrets of Messi’s goals in this match was that he understood the need to hold a wide position. In doing so, he created passing lanes for a number of dangerous attacks. ND: That was how the first of Messi’s three goals arrived. He received a crisp pass from Eto’o and fired home his first goal in a Clásico. His second came from a rebound inside the area, again with him as the most far right of all attacking players. But then Oleguer’s dismissal, after a second yellow card for a needless foul on Fernando Gago, right at the end of the first half, provoked a change both in Barça’s shape and Messi’s position within it. AD: Yes, the sending off completely changed things for the second half. Barça brought on Sylvinho for Eto’o and settled into a 3-4-2, with Messi and Ronaldinho together up front. Messi started to receive the ball much more often in central areas. ND: We can see that by looking at the positions in which Messi received the ball in the first half compared to the second.  AD: He and Ronaldinho carried the team on their backs. It was an exchange between them that led to the decisive 3–3 goal. ND: In the first half, they only exchanged six passes. In the second, they combined far more frequently, as seen below.

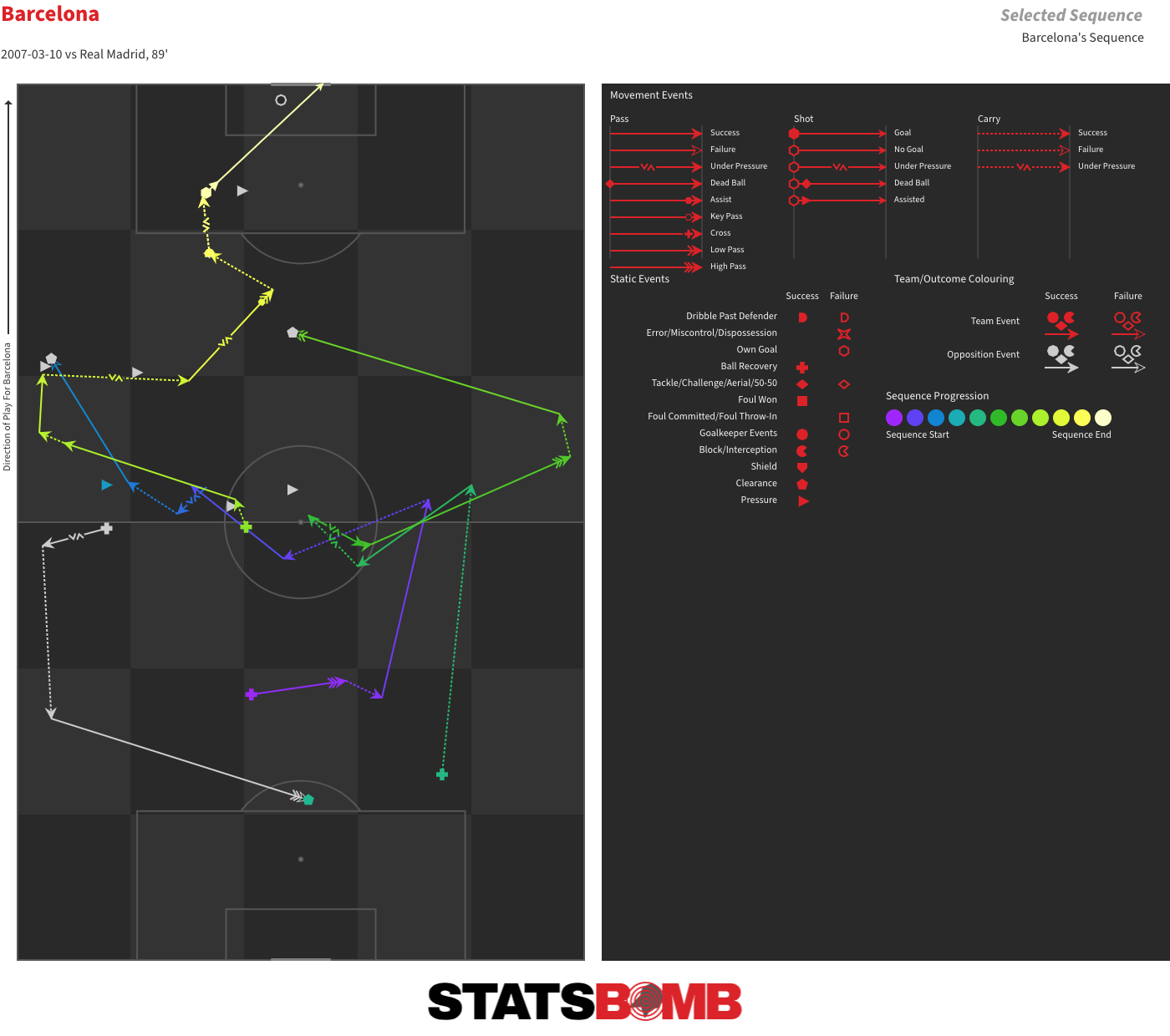

AD: He and Ronaldinho carried the team on their backs. It was an exchange between them that led to the decisive 3–3 goal. ND: In the first half, they only exchanged six passes. In the second, they combined far more frequently, as seen below.  And as you said, they combined for the equalising goal just a minute from full time.

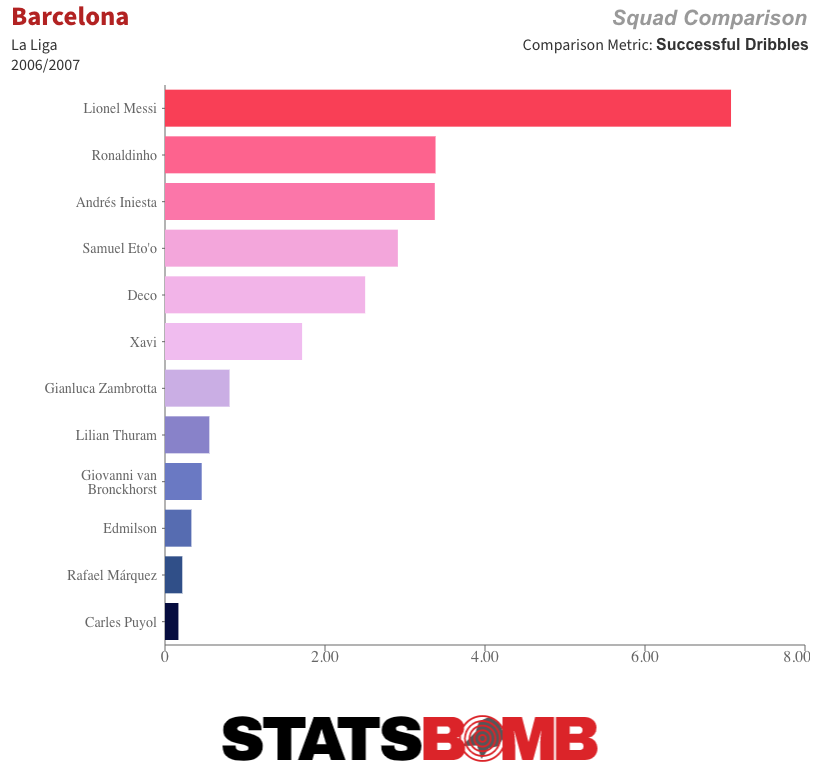

And as you said, they combined for the equalising goal just a minute from full time.  I’d like to ask you a couple of things related to that goal. The first is about Ronaldinho and his ability to play with his back to goal. On the goal, he received the ball like that, held off the pressuring defender and slipped a nice pass into Messi. For me, that's one of his underrated attributes, something that allowed him to interchange with Eto’o and play in central zones with relative ease. AD: Yes. Ronaldinho was a very complete attacking player. He could pass, shoot, dribble and as you say, he was strong and could protect the ball very well. At least when he was up for it . . . because a lot of it depended on his form. It is also fair to say that playing centrally neutered a number of his attributes. Eto’o also didn’t provide as much from wide. ND: The second question is about Messi and that initial burst of acceleration that was frequently decisive. On the goal, he received the ball perfectly on the half-turn, zipped past Iván Helguera and fired past Iker Casillas. Did he always have that burst, even in the youth teams? AD: He did. That burst of acceleration made him unstoppable at the youth level and for a great deal of his senior career. Once he got going, there was no way of stopping him. He’s still very quick today but he was electric back then. ND: When Messi appeared on the scene, the first thing that stood out about him was his dribbling ability. Over the course of his first three full seasons (2005–06 to 2007–08) in the first team, he completed an average of between 7.08 and 8.64 per 90 minutes. In this season, 2006–07, he completed over twice as many dribbles as any of his teammates.

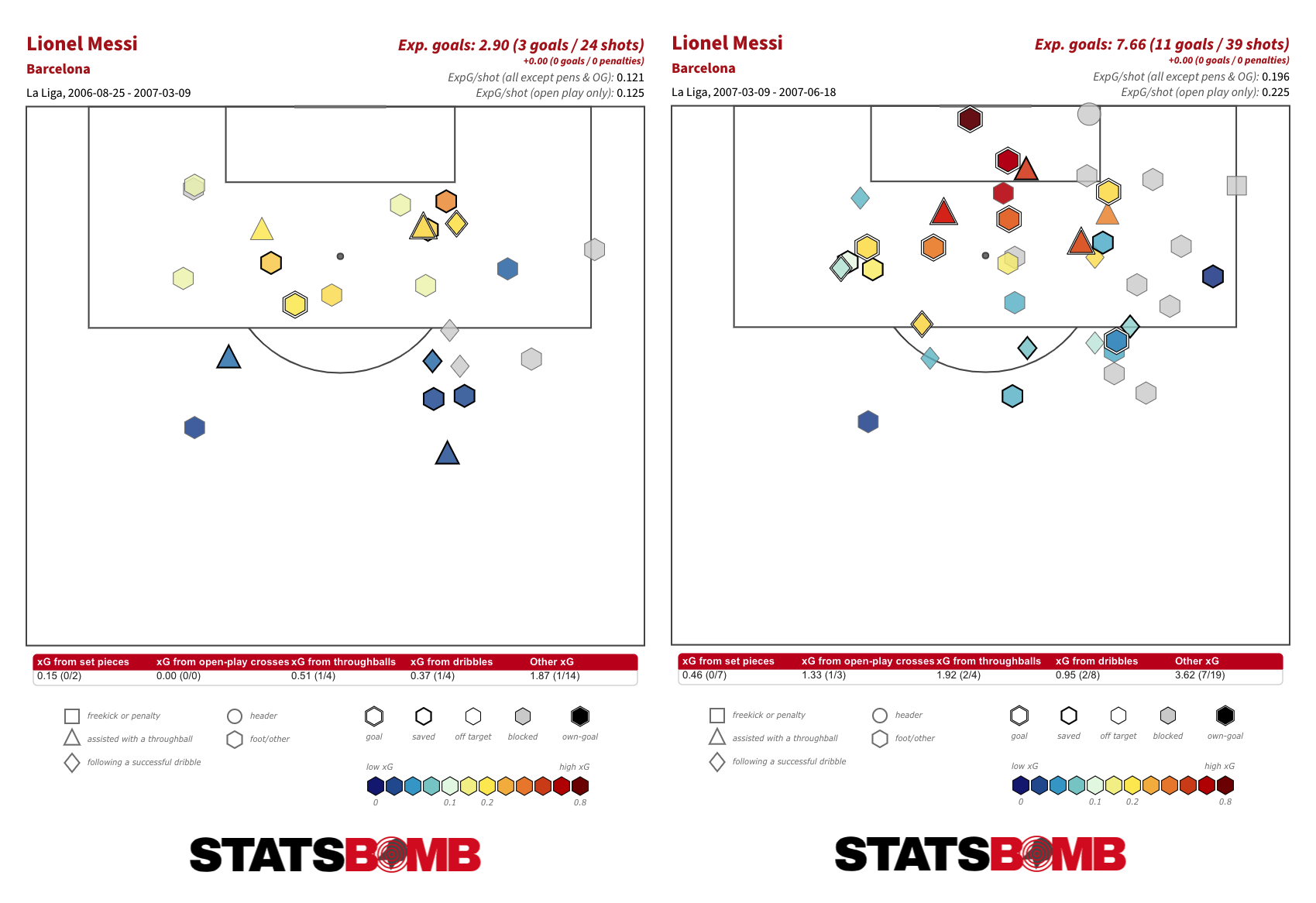

I’d like to ask you a couple of things related to that goal. The first is about Ronaldinho and his ability to play with his back to goal. On the goal, he received the ball like that, held off the pressuring defender and slipped a nice pass into Messi. For me, that's one of his underrated attributes, something that allowed him to interchange with Eto’o and play in central zones with relative ease. AD: Yes. Ronaldinho was a very complete attacking player. He could pass, shoot, dribble and as you say, he was strong and could protect the ball very well. At least when he was up for it . . . because a lot of it depended on his form. It is also fair to say that playing centrally neutered a number of his attributes. Eto’o also didn’t provide as much from wide. ND: The second question is about Messi and that initial burst of acceleration that was frequently decisive. On the goal, he received the ball perfectly on the half-turn, zipped past Iván Helguera and fired past Iker Casillas. Did he always have that burst, even in the youth teams? AD: He did. That burst of acceleration made him unstoppable at the youth level and for a great deal of his senior career. Once he got going, there was no way of stopping him. He’s still very quick today but he was electric back then. ND: When Messi appeared on the scene, the first thing that stood out about him was his dribbling ability. Over the course of his first three full seasons (2005–06 to 2007–08) in the first team, he completed an average of between 7.08 and 8.64 per 90 minutes. In this season, 2006–07, he completed over twice as many dribbles as any of his teammates.  But he always provided production in front of goal as well. In 2005–06, his first full season, he averaged 3.60 shots and 0.52 xG per 90. This match marked the start of an impressive run during the final three months of the 2006–07 season in which he registered 11 of his 14 goals for the year. He started to get into the area more often and take more shots from better positions.

But he always provided production in front of goal as well. In 2005–06, his first full season, he averaged 3.60 shots and 0.52 xG per 90. This match marked the start of an impressive run during the final three months of the 2006–07 season in which he registered 11 of his 14 goals for the year. He started to get into the area more often and take more shots from better positions.  Did that sudden eruption of goals surprise you? AD: He was progressing rapidly. That uptick in shots is somewhat linked to his growing status within the team and an increase in the amount of freedom he was given positionally. It was logical that his output would increase, but it was still a bit surprising. He had already made his goalscoring ability clear in the youth teams but one wouldn’t have imagined him becoming quite as a prolific scorer as he did. ND: It was Messi’s dribbling and shooting that first stood out, but his creative output also increased steadily over the course of his first few seasons. [table id=75 /] In this match, he produced a lovely reverse pass to get Ronaldinho into the area during the first half. Would you say that is the normal course for a talented young forward? That gradual shift from impact player to a more well-rounded and influential performer? AD: Yes, it is certainly linked to his maturation as a footballer. But such a startling degree of improvement in all areas can be explained by a few things. The first is that we are talking about a genius, the second is the normal development curve and the third his ambition to be the best. Messi embodies the fact that even the best can still improve. The clearest example is his free-kicks. Messi didn’t take free-kicks in the youth teams and neither did he in his first seasons as a professional. Now, he is the best free-kick taker in the world. ND: We will see the end result of all that improvement in the next part of the series. I think the second half of this match provided us with a nice preview of what is to come. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

Did that sudden eruption of goals surprise you? AD: He was progressing rapidly. That uptick in shots is somewhat linked to his growing status within the team and an increase in the amount of freedom he was given positionally. It was logical that his output would increase, but it was still a bit surprising. He had already made his goalscoring ability clear in the youth teams but one wouldn’t have imagined him becoming quite as a prolific scorer as he did. ND: It was Messi’s dribbling and shooting that first stood out, but his creative output also increased steadily over the course of his first few seasons. [table id=75 /] In this match, he produced a lovely reverse pass to get Ronaldinho into the area during the first half. Would you say that is the normal course for a talented young forward? That gradual shift from impact player to a more well-rounded and influential performer? AD: Yes, it is certainly linked to his maturation as a footballer. But such a startling degree of improvement in all areas can be explained by a few things. The first is that we are talking about a genius, the second is the normal development curve and the third his ambition to be the best. Messi embodies the fact that even the best can still improve. The clearest example is his free-kicks. Messi didn’t take free-kicks in the youth teams and neither did he in his first seasons as a professional. Now, he is the best free-kick taker in the world. ND: We will see the end result of all that improvement in the next part of the series. I think the second half of this match provided us with a nice preview of what is to come. Header image courtesy of the Press Association