For a club that hasn’t finished with more than 50 points in a season since 2012–13, Toulouse have given minutes to some interesting young talents over the years. Serge Aurier was a highly promising defender with his combination of athleticism and ability on the ball before his move to PSG in 2014. Issa Diop was logging huge minutes as a center-back when he was only 18 years, and while there were (and still are) questions about his ability as a passer, it was clear that he was going to make a move to a bigger club sooner than later. He's now at West Ham. Alban Lafont had even more hype. He was thought of by some as a goalkeeping prodigy when he started for Toulouse at just 16 years old. The fact all three of these players plied their trade at Toulouse emphasizes Ligue 1’s greatest selling point. No matter how far down the table you go, you’re going to find young talents that peak your curiosity.

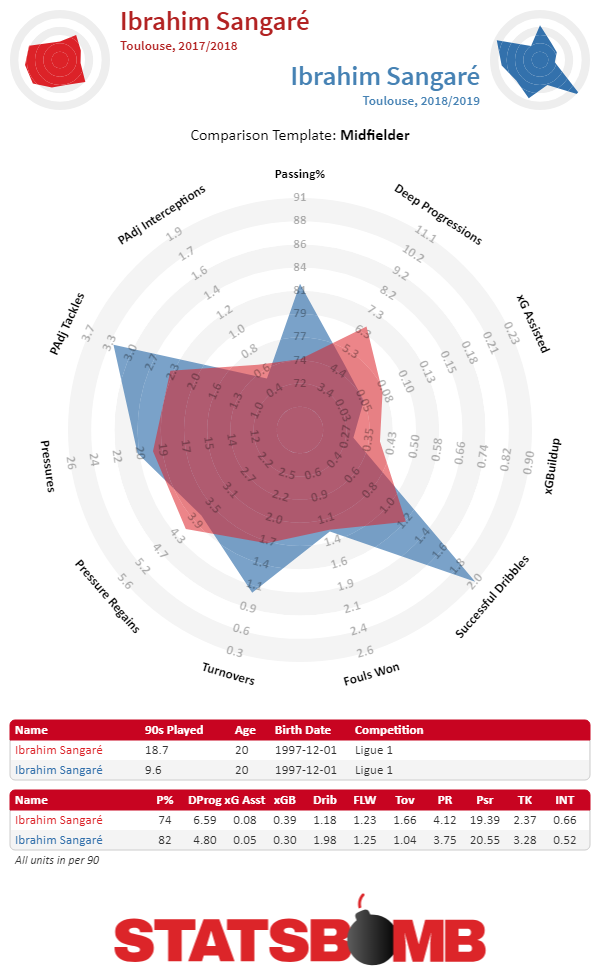

All of that brings us to Ibrahim Sangaré, who’s going to be next on the list of intriguing talents from Toulouse to make a move to a bigger club. Sangare already has a reputation as someone who could be a high upside bet from France worth targeting in the near future, and the likes of Atalanta and Brighton & Hove Albion reportedly logged transfer offers during the summer for his services. Sangare‘s improved performances this season in a deeper role (before his toe injury halted his momentum) turned him from a niche Ligue 1 prospect into one who's likely heading to greener pastures in the near future.

It should be noted that Toulouse have been one of the worst teams in Ligue 1. They’ve been out shot by nearly eight shots per match (9.5 to 17.4), no other team in Ligue 1 comes close to having such a disparity in shot share from either the positive or negative end of the spectrum. Toulouse are in the bottom three in expected goal difference per match at -0.57. The fact that this team is four points above 18th place despite being out shot and out created to such a massive degree is a bit of a minor miracle. Having an anemic attack with a defense that’s constantly on their heels means that analyzing Sangare means taking some of his numbers and properly contextualizing them. His on-ball contribution, for example, is stymied be the relatively low likelihood of racking up deep progressions for a team that rarely had the ball.

More than anything, we’re looking to see if there have been enough moments to justify a bigger club allocating resources for a potential transfer in the future. Is Sangare good enough that, if you put him on a team with a higher collective talent base, he won't take things off the table and perhaps even add some delectable dishes of his own. The biggest question is Sangare’s passing acumen. The standard of passing needed at the midfield position for good to great clubs is quite high. If Sangare’s going to truly pop as a young talent, he’ll need, at the very least, to be slightly above average as a passer and possibly significantly better than that.

The good news is that Sangare has shown enough glimpses to suggest that he's already a decent passer with room for upside in the near future. As a deeper midfielder in Toulouse's double pivot, he'll often times come and collect the ball near the center backs, even forming a back three on occasion. If there's no immediate pressure, Sangare has no qualms dribbling the ball forward until he gets approached by a marker. There are a couple of things that I appreciate about Sangare: more times than not he's going to try and attempt a pass that bypasses the defensive structure of the opponent, and that he doesn't seem to stutter with his passing when he makes his mind up. There's no proverbial hitch in Sangare's passing golf swing.

His match against Monaco was probably the best example of Sangare's upside as a deep midfielder. Granted, Monaco haven't been good this season, so it's not as if he was playing against elite opposition, but he was totally in his element making short-ish passes that found teammates in space between the lines. None of these passes were super difficult, but the fact he was making them with regularity was noteworthy.

Sangare isn't a game-breaking caliber of passer as it stands now, which is fine considering that he's only 20 years old. He's shown flashes of being able to make really difficult passes on the move, and the fact that he has the awareness to at least attempt them means something. It's just that his hit rate on these type of passes is not quite good enough yet. Perhaps in a couple of years as he matures and gets even more game experience under his belt, he'll become better in this department, which would be a scary proposition. A man at his size that could combine athleticism with a feathery touch in the passing department would eat people alive.

It is hard to ignore that Sangare is a large human being, standing at around 6'3. That becomes even more apparent when he decides to take on players and dribble by them. For a player as tall as he is, he doesn't look clumsy when he tries to beat his man off the dribble. He has pretty good coordination on the ball even when he's pressured. There are times when Sangare bites off a little more than he can chew and loses possession in the middle third, but it's fun watching him rumble. On the play below, Sangare has the ball near the touchlines and is being pressured quickly, but a simple shift to his right and he's gone.

He's even broken some ankles with his change of direction.

It's a little harder to figure out how good of a defender Sangare is, in part because quantifying defense is hard and he plays on a team that bleeds shots and scoring chances. A lot of his defensive work, whether it's pressures or tackles and interceptions, comes in his own third while Toulouse are hemmed in. Sangare's defensive output even when adjusting for Toulouse being a sub 50% possession side is impressive, and I just come back to the fact that the guy is just an imposing figure who also happens to have really solid mobility, which should allow clubs that play possession based football options on how to best use Sangare defensively once they lose the ball. Here, he is mirroring Allan Saint-Maximin, one of the most athletically gifted wide players that Ligue 1 has seen over the years, step for step before he dispossesses the ball from him. That's no easy feat.

There are a number of things to like about Sangare's game. He's a comfortable passer from deeper areas who has at least shown the willingness to try high level passes. He's an imposing figure because of his size and functional athleticism, and he's able to carry the ball off the dribble because it's really hard to take the ball away from a 6'3 dude who isn't a stiff. There are the flaws to his game that I've already touched on, and one major one that I haven't. His positioning off the ball in attack can leave a little bit to be desired. When a teammate has the ball, he'll get into a position between the man on the ball and another teammate close to him which eliminates a potential passing angle. He could also stand to be a bit more aggressive sometimes in stepping out 5-7 yards from his original starting point to receive passes and move the ball forward when in his own third. But it's fair to point out that Toulouse's attack stinks, and that most of these tendencies could very well be eliminated if he plays on a team with better talent and coaching.

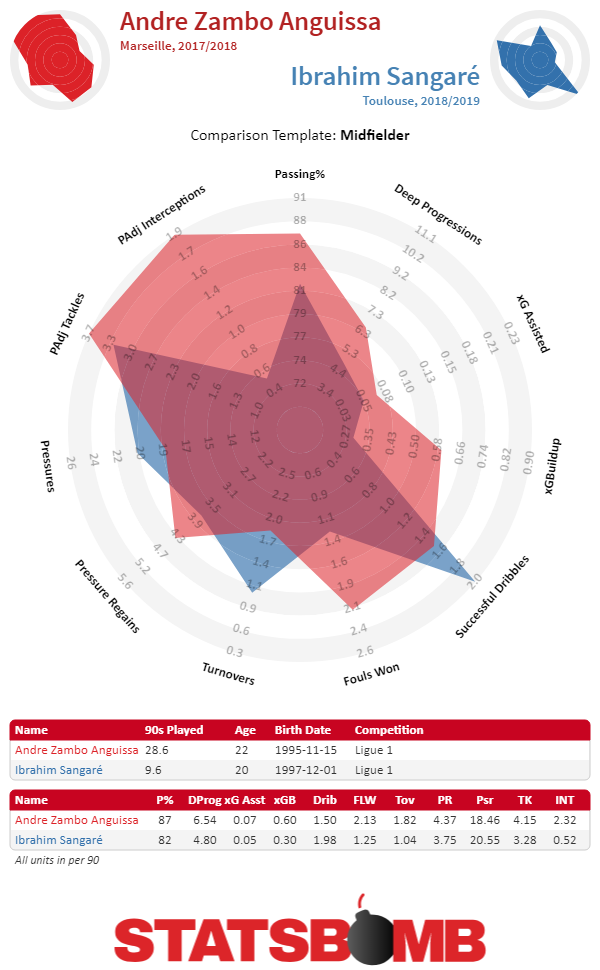

When trying to project how good Sangare can be, I came back to Andre Zambo Anguissa. Granted, Anguissa has had his rough moments at Fulham from a defensive standpoint (who hasn't on that club), but he was really good last season on a very good Marseille side. On a team with Florian Thauvin, Dimitri Payet and Morgan Sanson, Anguissa wasn't tasked with having to unlock defenses. Rather, he could just maintain the flow of possession, and make short but incisive passes to one of the attackers to work their magic. It's easy to see that Sangare could operate in a similar role when he makes the step up to a bigger club, and do what Anguissa did defensively which was putting out fires immediately off of live ball turnovers. There's even a little bit of similarities from their respective statistical outputs, which is impressive on Sangare's end considering he's on an inferior squad and is over two years younger than Anguissa.

I am on the Ibrahim Sangare bandwagon. I just think that there's legitimate untapped potential to his game that could see him go to another level. If he's able to hone in on his passing, he could play on a very good club in the next 2-3 years. Even if Sangare doesn't make an appreciable jump in performance and this is more or less what he is throughout the next 6-8 years, he's still shown enough to where I'd feel comfortable having him on decent-good teams like Marseille or RB Leipzig in a supporting role offensively. The 90th percentile outcome for Ibrahim Sangare as a player is tantalizing enough to where I am really fascinated with his development and just how many souls he can destroy on his path to potential greatness.

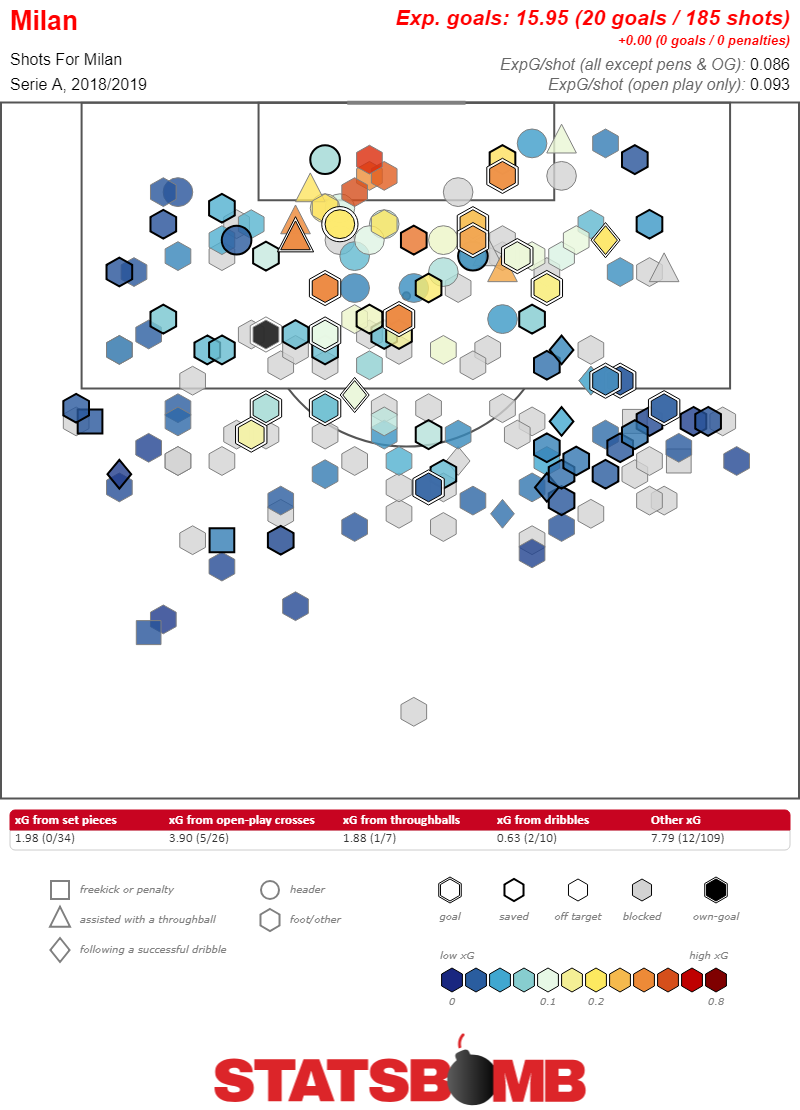

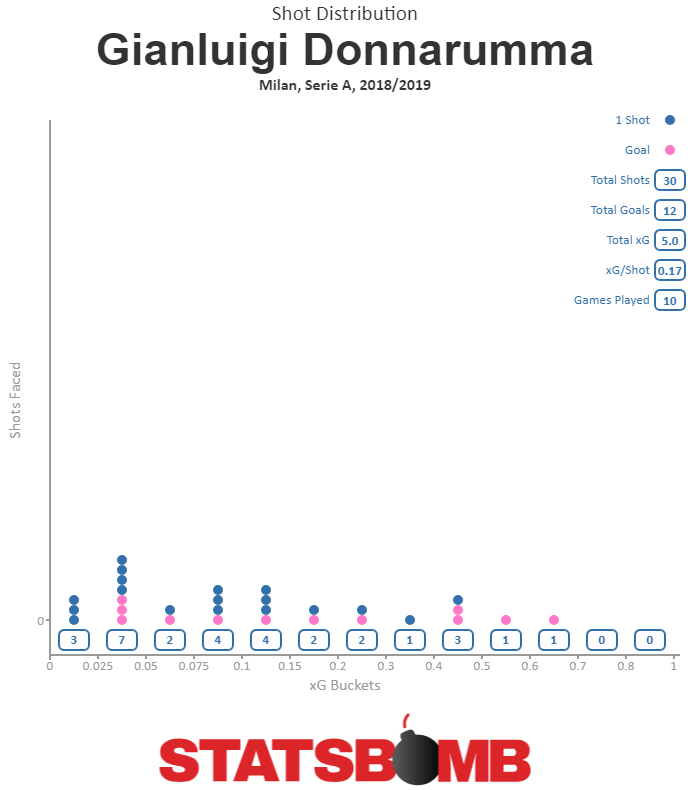

That’s an awful lot of blue. And Milan’s xG per shot really isn’t anything to write home about at 0.09. It’s smack dab in the middle of the Serie A, 10th best. But,nobody in Italy really takes great shots. Not a single team has over 0.11 xG per shot. Everybody is cranking the ball from distance, or crossing it in for the wing and hoping for the best. The teams that excel just manage to pile on the volume advantage. Milan’s shot selection may not give them an advantage, but it doesn’t particularly disadvantage them against their rivals either. It just makes them normal. Given that Milan are wracking up those shots, it doesn’t hurt to have Gonzalo Higuain leading the line. Sure Higuain is 30, and he’s not going to be the secret to Milan’s long term success. He’s also mostly a continuation of a troubling Milan trend of paying for older players rather than shelling out for contributors that still have their best days in front of them. But Higuain remains very very good. He’s ninth in Serie A with 0.46 xG per 90 minutes (and four of the eight players above him play for Napoli or Juventus). Outside of Higuain, however, the team’s lack of ability to create good shots becomes clear. The players that take the most shots like Suso and Hakan Calhanoglu are different from the ones who take the best shots, mostly just Diego Laxalt.

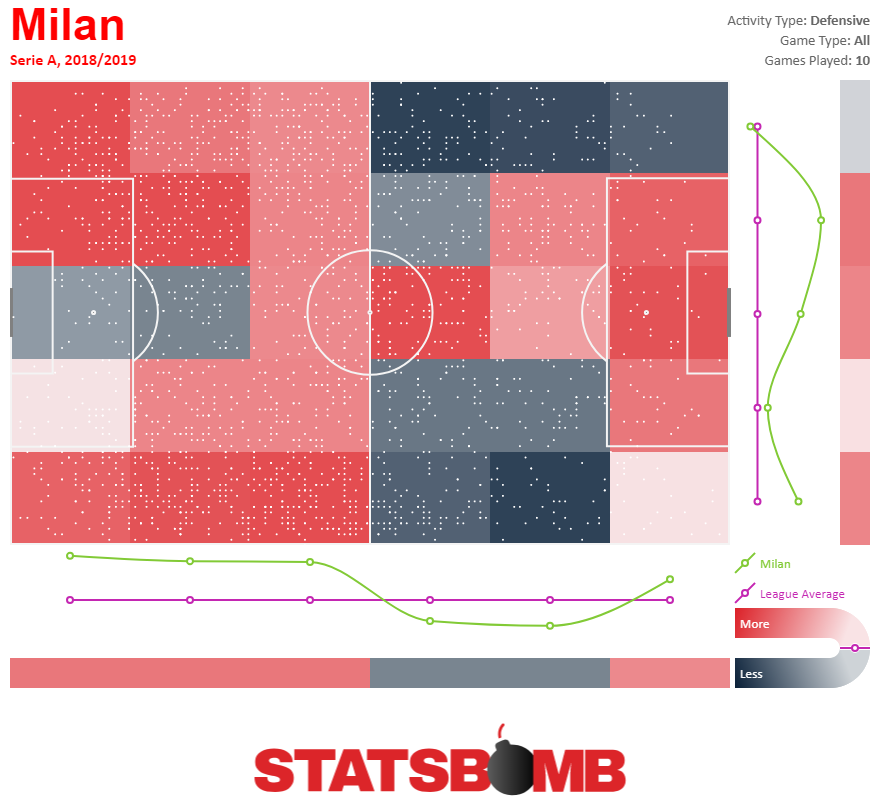

That’s an awful lot of blue. And Milan’s xG per shot really isn’t anything to write home about at 0.09. It’s smack dab in the middle of the Serie A, 10th best. But,nobody in Italy really takes great shots. Not a single team has over 0.11 xG per shot. Everybody is cranking the ball from distance, or crossing it in for the wing and hoping for the best. The teams that excel just manage to pile on the volume advantage. Milan’s shot selection may not give them an advantage, but it doesn’t particularly disadvantage them against their rivals either. It just makes them normal. Given that Milan are wracking up those shots, it doesn’t hurt to have Gonzalo Higuain leading the line. Sure Higuain is 30, and he’s not going to be the secret to Milan’s long term success. He’s also mostly a continuation of a troubling Milan trend of paying for older players rather than shelling out for contributors that still have their best days in front of them. But Higuain remains very very good. He’s ninth in Serie A with 0.46 xG per 90 minutes (and four of the eight players above him play for Napoli or Juventus). Outside of Higuain, however, the team’s lack of ability to create good shots becomes clear. The players that take the most shots like Suso and Hakan Calhanoglu are different from the ones who take the best shots, mostly just Diego Laxalt.  Defensively Milan are a very interesting side. They’re one of the most conservative teams in the league. Opponents complete 83% of their passes against Milan, only Chievo, Frosinone, and Parma, otherwise known as by far the worst two teams in Italy and Parma, are easier to pass against. The average distance from their own goal of the defensive actions they undertake is 43.16 yards, the third most conservative average in the league. Their PPDA (passes allowed per defensive action, a measure of how easy it is for opponents to complete passes in their own half) is 13.13, the sixth highest (or most permissive) in Italy. When the opposition has possession, Milan don’t worry about taking it away, they just worry about making sure they get men in the right places behind the ball to not get broken down. The one wrinkle, which their defensive action heat map makes clear, is that they do have a brief counterpress installed to muddy up the works around their opponent’s penalty area. In effect, when they lose the ball, they make sure they have enough defensive presence to stop counters before they start and give the team time to set up their own defense.

Defensively Milan are a very interesting side. They’re one of the most conservative teams in the league. Opponents complete 83% of their passes against Milan, only Chievo, Frosinone, and Parma, otherwise known as by far the worst two teams in Italy and Parma, are easier to pass against. The average distance from their own goal of the defensive actions they undertake is 43.16 yards, the third most conservative average in the league. Their PPDA (passes allowed per defensive action, a measure of how easy it is for opponents to complete passes in their own half) is 13.13, the sixth highest (or most permissive) in Italy. When the opposition has possession, Milan don’t worry about taking it away, they just worry about making sure they get men in the right places behind the ball to not get broken down. The one wrinkle, which their defensive action heat map makes clear, is that they do have a brief counterpress installed to muddy up the works around their opponent’s penalty area. In effect, when they lose the ball, they make sure they have enough defensive presence to stop counters before they start and give the team time to set up their own defense.  Assuming this all normalizes, what we’d expect to see from Milan over the rest of the season is a competent, but somewhat more boring side. They’ll likely score fewer goals, but they’ll also likely concede fewer. That’s more than enough to keep them in the race for fourth place. Given where this side has been over the previous five years that’s an invaluable step in the right direction.

Assuming this all normalizes, what we’d expect to see from Milan over the rest of the season is a competent, but somewhat more boring side. They’ll likely score fewer goals, but they’ll also likely concede fewer. That’s more than enough to keep them in the race for fourth place. Given where this side has been over the previous five years that’s an invaluable step in the right direction.

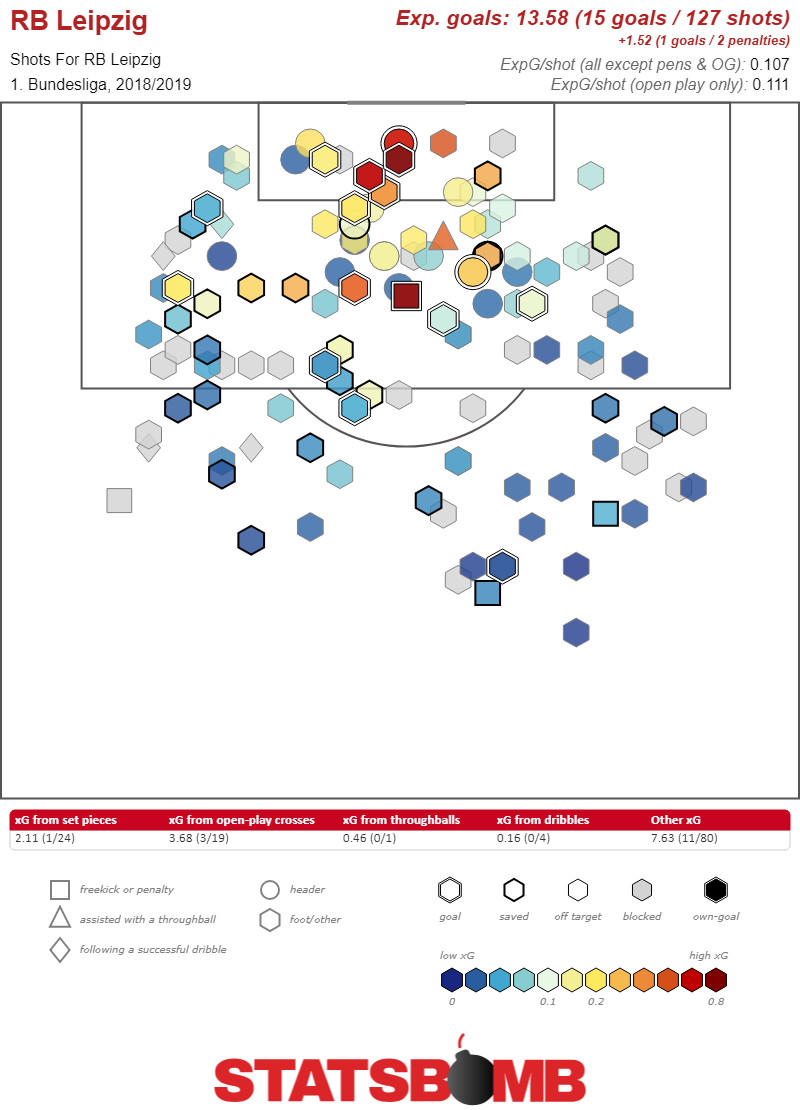

The shots they create tilt toward quantity over quality, especially in the penalty box itself where players are happy to shoot from difficult angles if given half a chance.

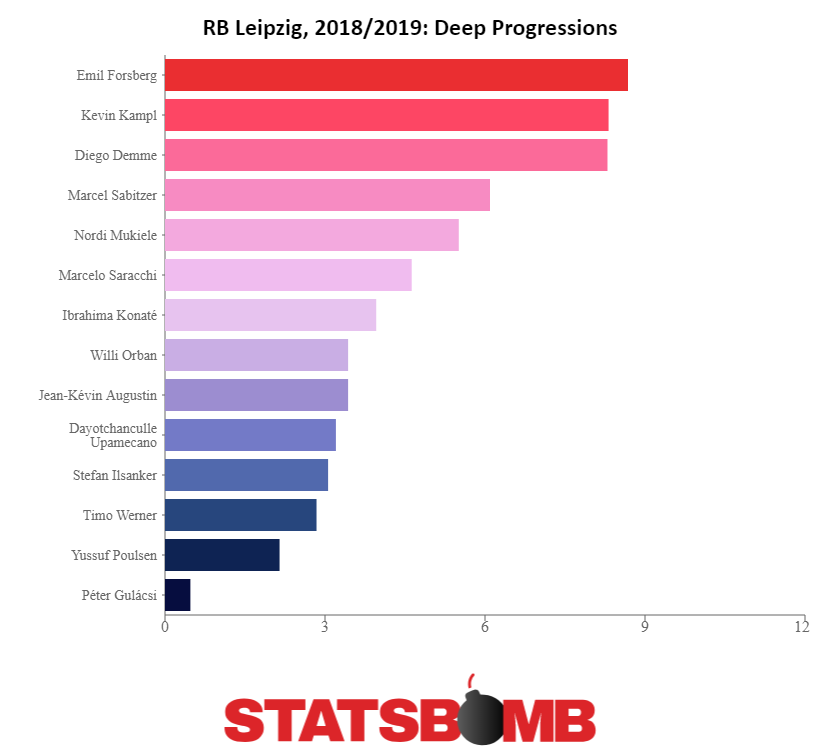

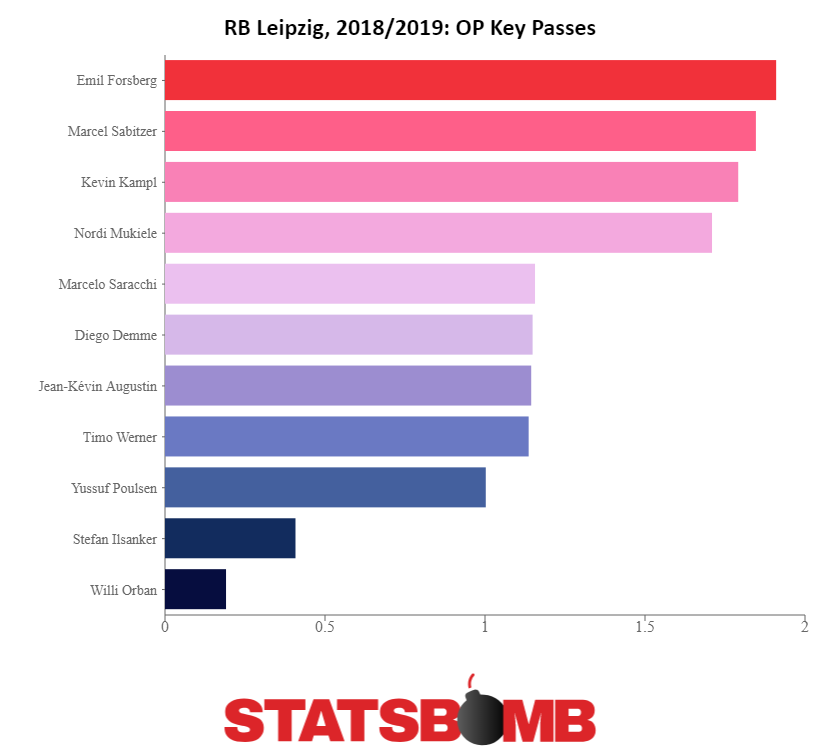

The shots they create tilt toward quantity over quality, especially in the penalty box itself where players are happy to shoot from difficult angles if given half a chance.  It’s fairly ironic that Leipzig are currently succeeding by playing a somewhat more normal style. Rangnick is one of a small handful of people who can credibly claim to be responsible for ushering in the era of manic defending. It was Rangnick who brought Roger Schmidt to Salzburg in 2012. Schmidt took the high octane counterpressing style that was developing in Germany as Jurgen Klopp turned Dortmund into a juggernaut and turbocharged it at Salzburg. It was an ethos that Rangnick also instituted at Leipzig. Contest the ball as soon as you lose it. Step forward. Win the ball in midfield, play a killer pass or three and then do it all over again. When Leipzig reached the top division the team had immediate success as a defensive juggernaut. They pressed high, they pressed well and they made themselves impenetrable. In a league where everybody pressed, Leipzig stood out. They were one of the top three teams in terms of Passes Per Defensive Action (a metric which measures how many defensive actions a team takes per completed pass they allow in the opposition’s half, one way to measure pressing). That’s not to say that the current iteration of Leipzig doesn’t press. They do. This is a very aggressive defensive heatmap, one that shows a team chasing the ball all over the field. But the team’s numbers have still dropped off notably in this department. Leipzig are only the fifth most aggressive team by PPDA.

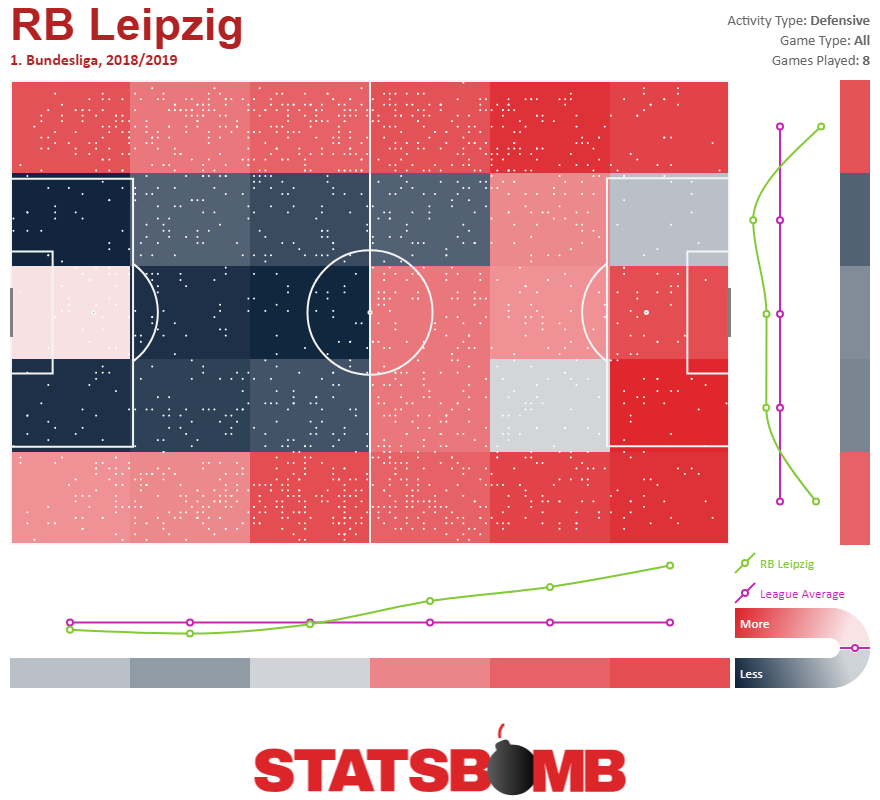

It’s fairly ironic that Leipzig are currently succeeding by playing a somewhat more normal style. Rangnick is one of a small handful of people who can credibly claim to be responsible for ushering in the era of manic defending. It was Rangnick who brought Roger Schmidt to Salzburg in 2012. Schmidt took the high octane counterpressing style that was developing in Germany as Jurgen Klopp turned Dortmund into a juggernaut and turbocharged it at Salzburg. It was an ethos that Rangnick also instituted at Leipzig. Contest the ball as soon as you lose it. Step forward. Win the ball in midfield, play a killer pass or three and then do it all over again. When Leipzig reached the top division the team had immediate success as a defensive juggernaut. They pressed high, they pressed well and they made themselves impenetrable. In a league where everybody pressed, Leipzig stood out. They were one of the top three teams in terms of Passes Per Defensive Action (a metric which measures how many defensive actions a team takes per completed pass they allow in the opposition’s half, one way to measure pressing). That’s not to say that the current iteration of Leipzig doesn’t press. They do. This is a very aggressive defensive heatmap, one that shows a team chasing the ball all over the field. But the team’s numbers have still dropped off notably in this department. Leipzig are only the fifth most aggressive team by PPDA.  Part of what’s going on here may simply be the effects of a German game which has begun to dramatically slow down over the last couple of seasons. Germany has lost a number of coaches that prioritized playing at breakneck defensive speed. Klopp, Schmidt, Thomas Tuchel and Pep Guardiola all built sides that were designed to defend largely in their opponent’s half and aggressively win the ball back. All of those managers are gone. A number of German teams have achieved success recently playing much more conservatively in defense. Last year’s second place finisher, Schalke played an extremely effective negative style (and despite languishing in 15th place right now have the third best xG against tally in the league and a positive xG differential and will likely improve). This year’s Dortmund team under Lucien Favre play a more conservative style, using possession to create chances rather than using an aggressive defense as the primary creative force. A few years ago the Bundesliga was a counterpressing arms race. Everybody was trying to out press and out scramble everybody else. Eventually there were diminishing returns. It became increasingly difficult to both press more aggressively than the team you were facing and maintain tactical balance so as not to get exploited. Now that trend is reversing itself. A slower Bundesliga means that Rangnick and Marsch have been able to come in, rein in the extreme aggressiveness the team had deployed over its first two seasons, and still manage to be near the top of the league as a pressing defense. The changing Bundesliga suits Leipzig just fine. It’s meant they can decrease their defensive aggressiveness to more stable levels while remaining more aggressive than most of their opponents. In turn, their increased stability has meant attackers can find more shots, and the team as a whole can operate with an effective rhythm of taking the ball, progressing it and shooting it, rather than getting drawn into helter-skelter midfield battles of attrition. Rangnick and Marsch have taken advantage of a changing league and turned a year of transition into one where they are arguably the second or third best team in the league. Not bad for an interim coaching squad.

Part of what’s going on here may simply be the effects of a German game which has begun to dramatically slow down over the last couple of seasons. Germany has lost a number of coaches that prioritized playing at breakneck defensive speed. Klopp, Schmidt, Thomas Tuchel and Pep Guardiola all built sides that were designed to defend largely in their opponent’s half and aggressively win the ball back. All of those managers are gone. A number of German teams have achieved success recently playing much more conservatively in defense. Last year’s second place finisher, Schalke played an extremely effective negative style (and despite languishing in 15th place right now have the third best xG against tally in the league and a positive xG differential and will likely improve). This year’s Dortmund team under Lucien Favre play a more conservative style, using possession to create chances rather than using an aggressive defense as the primary creative force. A few years ago the Bundesliga was a counterpressing arms race. Everybody was trying to out press and out scramble everybody else. Eventually there were diminishing returns. It became increasingly difficult to both press more aggressively than the team you were facing and maintain tactical balance so as not to get exploited. Now that trend is reversing itself. A slower Bundesliga means that Rangnick and Marsch have been able to come in, rein in the extreme aggressiveness the team had deployed over its first two seasons, and still manage to be near the top of the league as a pressing defense. The changing Bundesliga suits Leipzig just fine. It’s meant they can decrease their defensive aggressiveness to more stable levels while remaining more aggressive than most of their opponents. In turn, their increased stability has meant attackers can find more shots, and the team as a whole can operate with an effective rhythm of taking the ball, progressing it and shooting it, rather than getting drawn into helter-skelter midfield battles of attrition. Rangnick and Marsch have taken advantage of a changing league and turned a year of transition into one where they are arguably the second or third best team in the league. Not bad for an interim coaching squad.