What’s left to say about Manchester City? They’re two-time champions, coming off the best two seasons in Premier League history. They’re prohibitive favorites to once again win the title. They’ve established, through both performance and economic might, a baseline of excellence that only they can hope to meet. The only question is, will they?

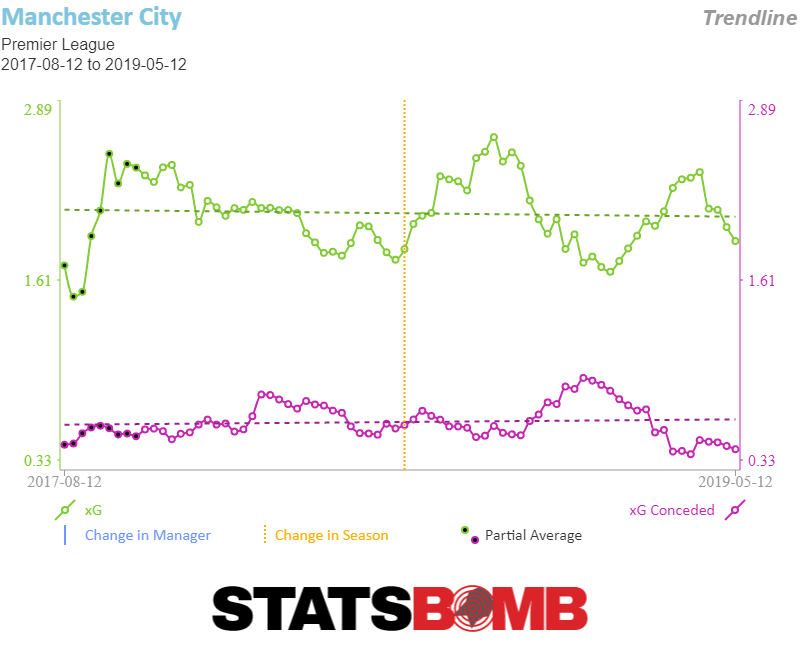

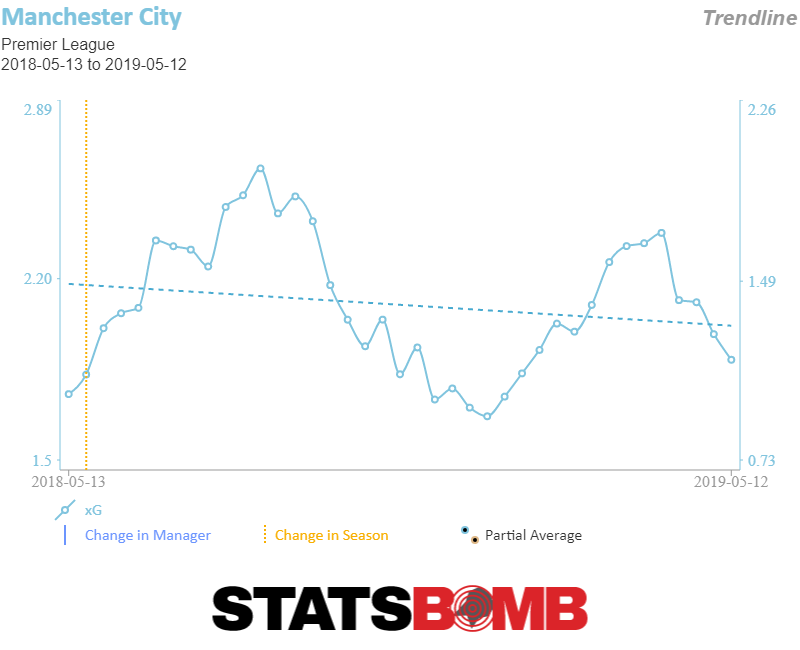

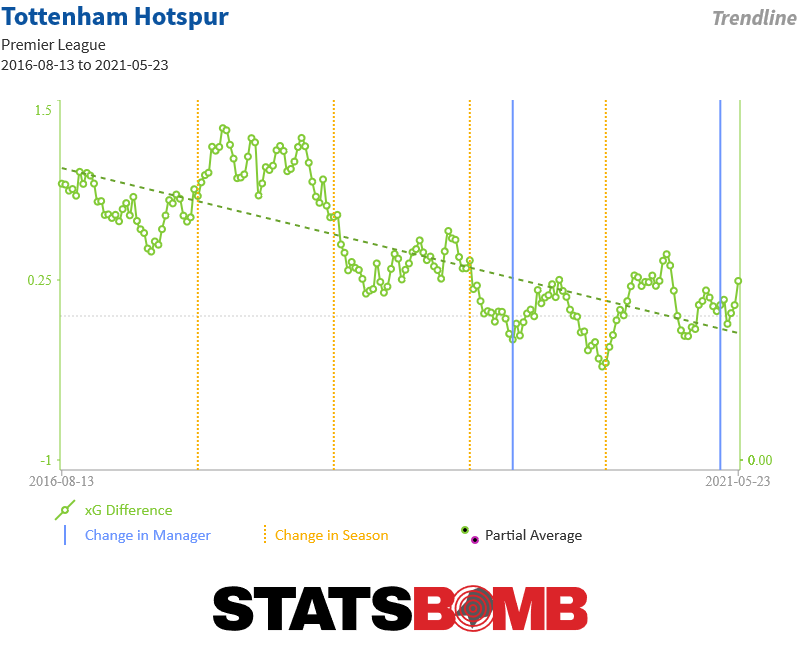

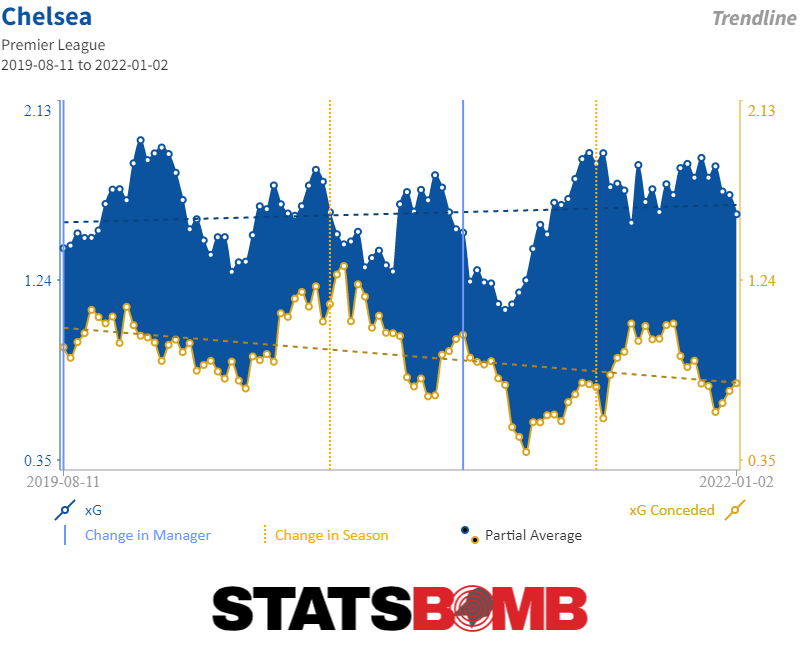

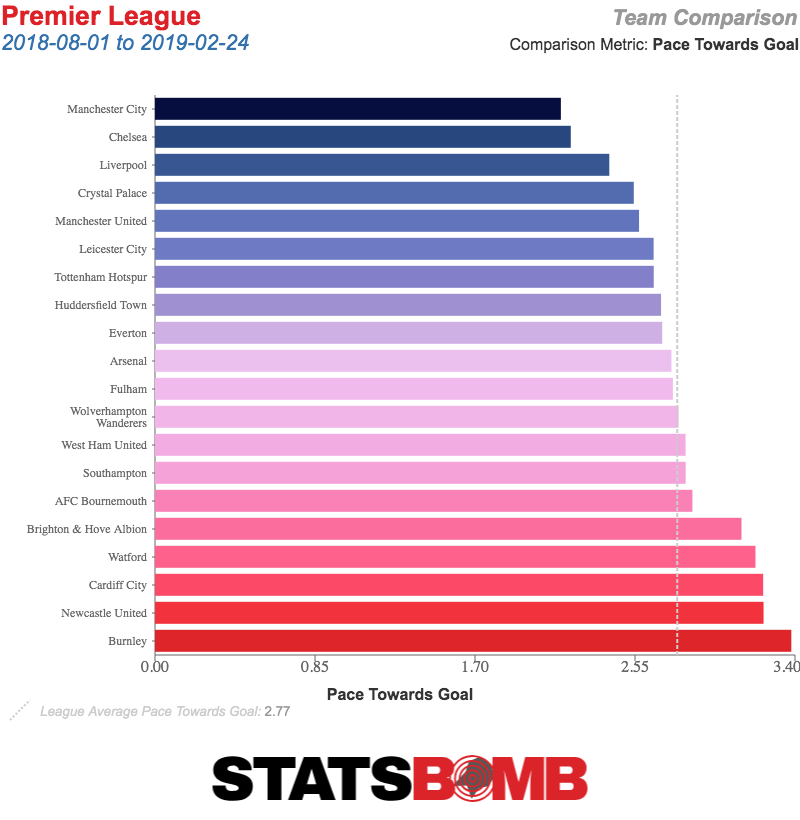

It goes without saying that City are excellent. But let’s say it anyway. StatsBomb has City’s expected goal difference from last season as 1.51. No other team was over 1.00. Liverpool was at 0.99. The only other team even half an expected goal to the good was Chelsea at 0.53. Liverpool managed to run them to the wire in the league, but it took everything going perfect for them to do so. City just kind of had an average season for City. This is two years worth of xG trend, it just doesn’t get any better than this.

The question then, for the second year running, isn’t, will City win, it’s what has to happen for City not to win the title? It’s not enough simply for another team like Liverpool or Tottenham to catch fire, that happened last season, and City withstood it. Instead, another team has to catch fire, and something has to go wrong, perhaps badly wrong, for Pep Guardiola’s team. What might that be?

Let’s start in attack. Manchester City has no plan B. They don’t need one because their plan A is pretty much unstoppable. They pass the ball around forever, the team’s two free eights join the front three pressing five attackers against the back line, interchanging and probing for attacking chances, eventually the defense breaks down, City plays a ball across the face and somebody gets a tap-in. It seems ridiculous to say that a team that shot the ball 17.89 times per game last season, the highest mark in the league, is patient, but City are. They also had the highest expected goal per shot total in the league at 0.12. They took the most shots and the best shots.

One way this patience showed is that when the team struggled, it manifested itself in decreased shot totals. Sometimes when committed defensive sides manage to hold a great team down, its by forcing the favorites to take an enormous number of long distance shots, and then avoiding getting unlucky. City steadfastly refuse to do that. They keep looking for that perfect pass even if it means their shot totals dip. That’s what happened during their brief dip from December to March. They kept hunting great shots, they just stopped finding them.

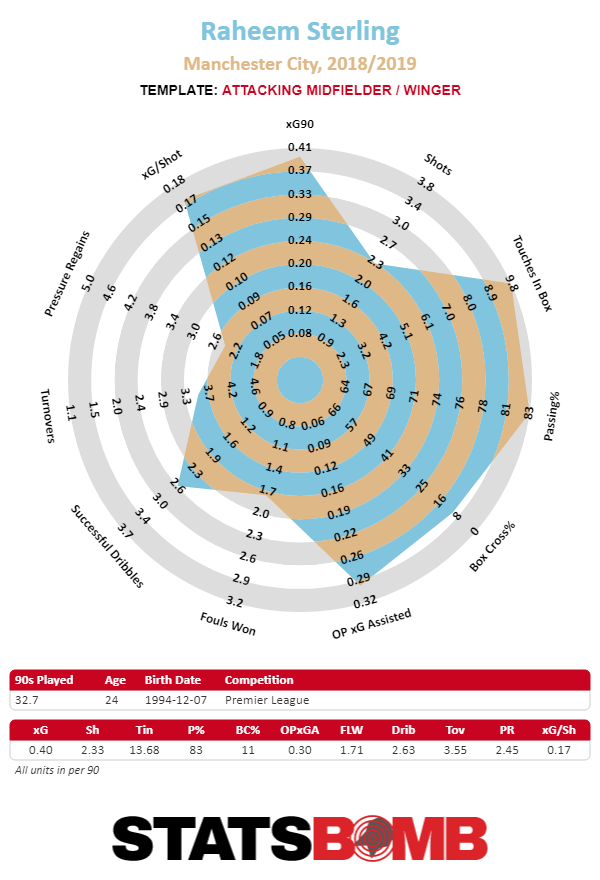

Part of the reason they’re so good at finding great shots is Guardiola’s ability to customize his attack. Raheem Sterling was deployed equally on the left side and the right side, splitting his time between the two flanks depending on the manager’s plans. He had an attacking season on par with anybody in the Premier League, but not one that involved a high volume of shots.

Bernardo Silva also provided that flexibility. He spent two thirds of his minutes in the right attacking midfield role and one third on the right wing. Over the last season he developed from a player who provided Guardiola with flexible depth off the bench to one who was almost always on the team sheet, even if where he was deployed would change. Silva started 31 games and appeared in five more as a substitute.

Those two players meant that Guardiola could deploy his other great players, who might have been slightly more limited positionally, only when he saw fit. Riyad Mahrez was deployed on the right wing only when it suited Guardiola, for slightly less than 1500 minutes. Through injury and rotation Kevin De Bruyne, exclusively an eight, played barely over 1000. Leroy Sané the team’s dedicated left winger played just under 2000 minutes.

And this is where we come to the first potential problem. Sané will miss most, if not all, of the season following an injury to his anterior cruciate ligament. It might seem at first glance that on a team of attacking superstars (we haven’t even mentions Sergio Aguero and David Silva yet) his 2000 minutes would be easily replaced. And they might be, though we shouldn't discount his tremendous level of performance last season.

But, without him, Guardiola may end up needing to simply stick Sterling on the left wing and that removes the manager's flexibility. Not only does it take Sané out of his toolbox it also means that he can no longer play the Sterling, Bernardo Silva combination on the right when he deems that his best option. It has knock-on effects to left back, where Oleg Zinchenko, a player more comfortable, and better suited to, pinching narrow was beginning to establish himself. He’s a better fit with a winger who likes to stay wide than one like Sterling on the left who wants to move inside. These are small issues to be sure, but the process of finding chinks in City’s armor is one of looking for small problems, and wondering what might happen if they become larger. Maybe these potential small tactical hurdles are a place to start.

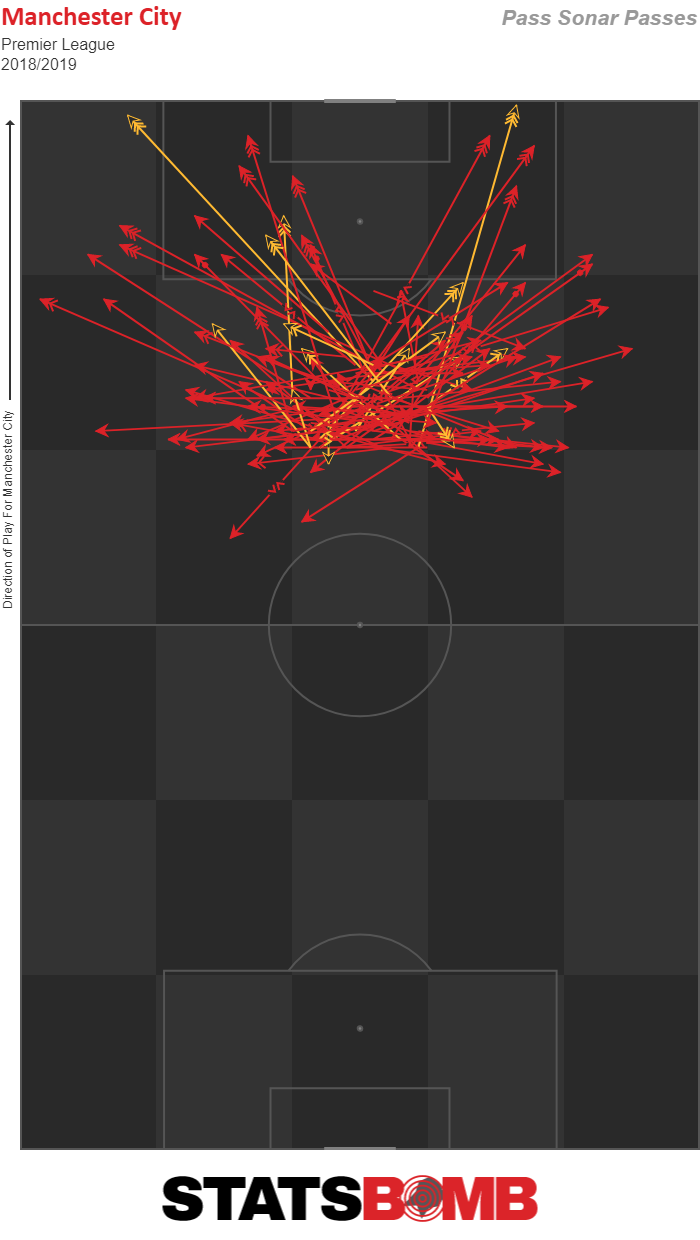

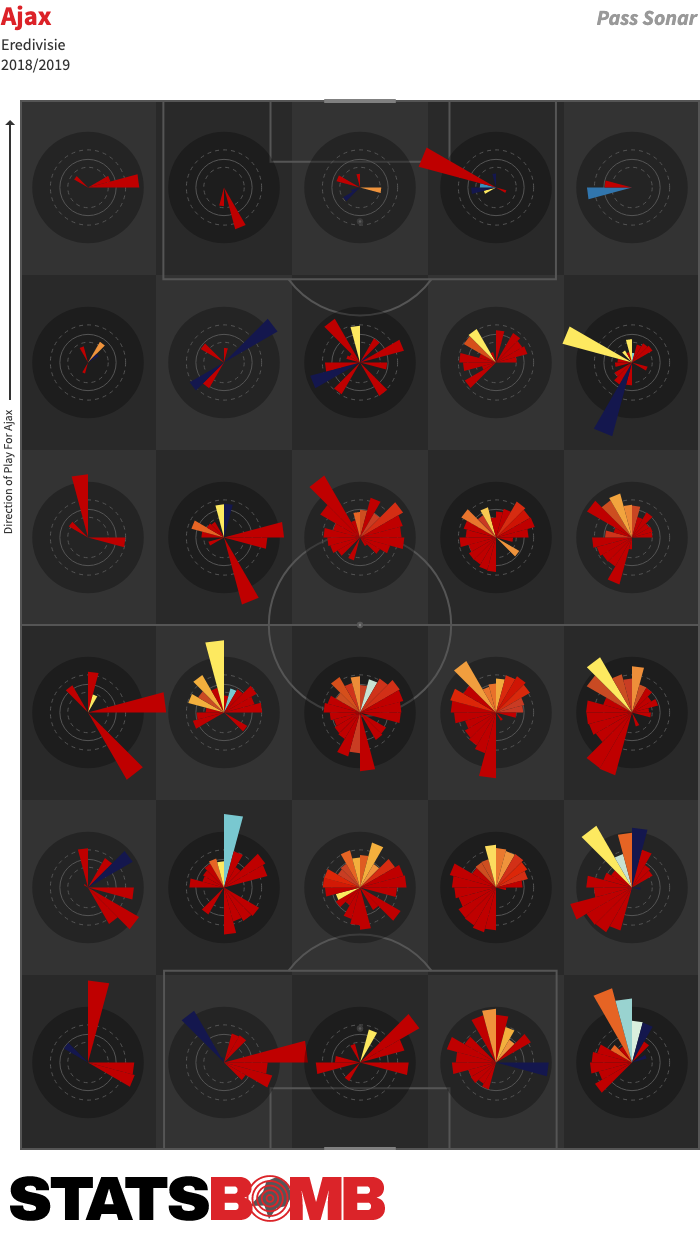

Then there’s further back the field. City’s fire breathing run the last two seasons has been powered by Fernandinho at the base of midfield. He does it all. Not only is he the first defender tasked with breaking up counterattacks, last season more of the ball progression duties fell to him as De Bruyne played a smaller role. Not only did he distribute it from deep, as his sonar shows:

But he’d often step incredibly high up the field and play a critical role in possession, either circulating the ball side to side as the team prodded for openings, or feeding balls into the box himself (red is complete and yellow is incomplete):

For years, City’s achilles heel has appeared to be that Fernandinho’s greatness was irreplaceable and his backup Ilkay Gündoğan while incredibly skilled in his own right was not enough of a defender to replace the immense contributions of the Brazilian who was closing in on his mid-30s. It never proved enough to slow City down.

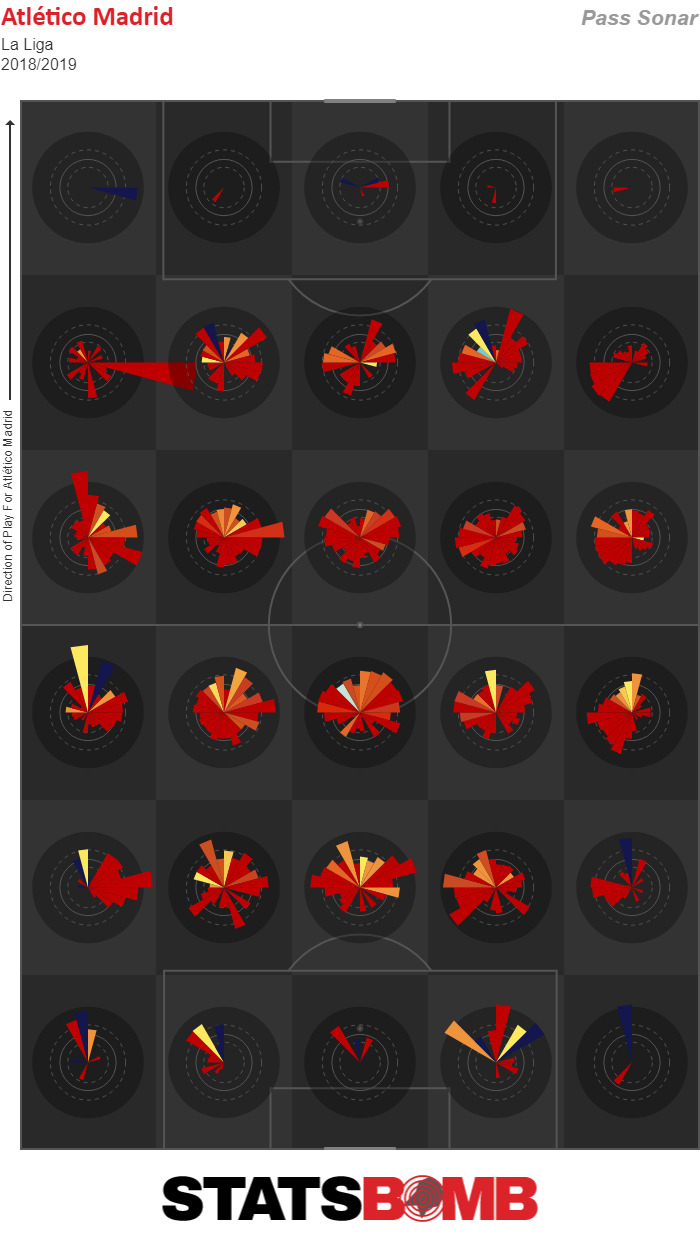

Now, there’s a succession plan in place. City acquired Rodri, who seems destined to be Fernandinho’s heir. Looking at the defensive midfielders passing sonars from last season might suggest he’d be an awkward fit. Playing in Diego Simeone’s conservative Atletico Madrid side, he played the ball side to side, and backwards a lot in midfield, rarely progressing it up the field, which will be a big part of the job at City.

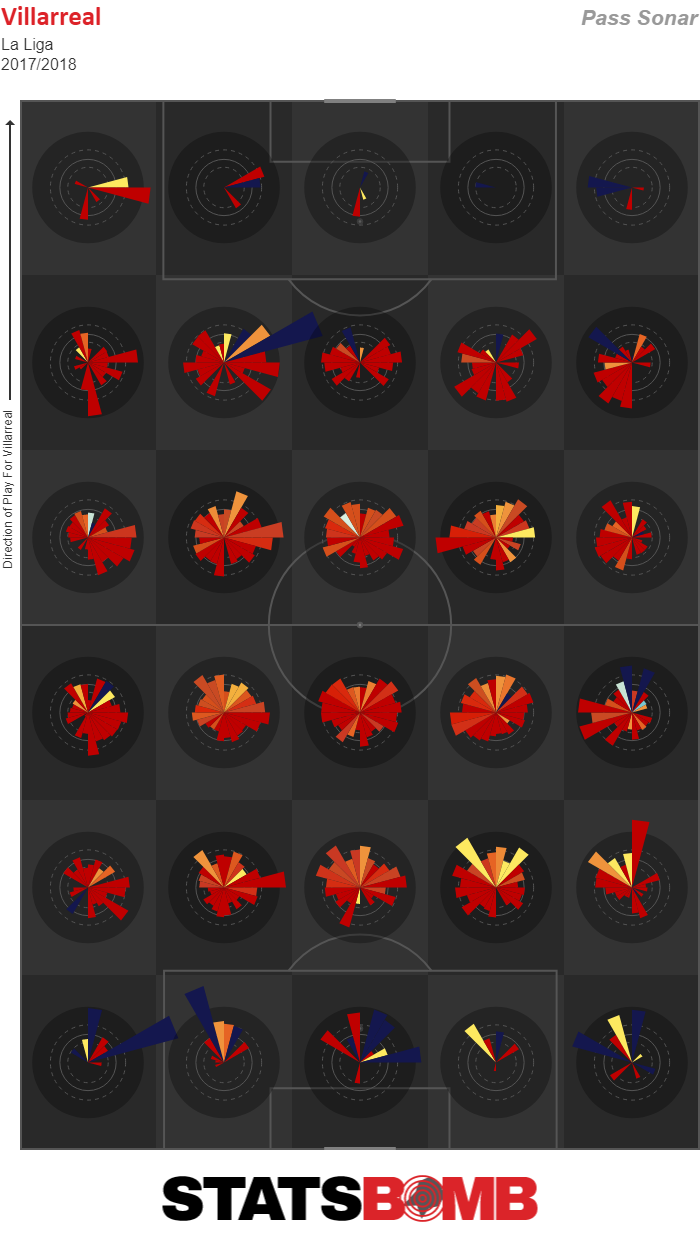

But, go back a season further, to his time at Villarreal and the appeal becomes much clearer. There his passing is more expansive, more forward oriented and more like what will be expected of him as he inherits the keys to City’s midfield.

Of course, just because Rodri makes sense on sonar doesn’t mean he will be able to handle the job in real life. It’s both a massive set of responsibilities and a herculean task. He’ll likely be eased into the role with Fernandinho still playing midfield minutes, but the result of it all is that while in past years the risk for City was that they had no capable replacement for an old defensive midfielder, now the risk is that the transition which they have planned won’t come off. City recognized where they were exposed and moved to address the issue with their chosen transfer target, but not all transfers work. Not having a plan in place for covering Fernandinho was an avoidable risk, they’ve now avoided it, and are left with only the unavoidable, smaller possibility that Rodri doesn’t make the cut.

Then there’s the defense. Vincent Kompany is gone and no center back has come to take his place. Instead Danilo, who provided fullback depth has been swapped for João Cancelo a gifted attacking fullback from Juventus. This suggests that the Fernandinho plan also involves him stepping into the back line some, as he did towards the end of last season. Guardiola often plays a system in which no matter whether he starts with a back three or four, when the team has the ball three players are left doing defending work, one of whom has license to step into midfield. Usually that role was played by Kyle Walker from right back, but Fernandinho was occasionally deployed in the middle to do it, and Aymeric Laporte also sometimes had the job when he started at left back.

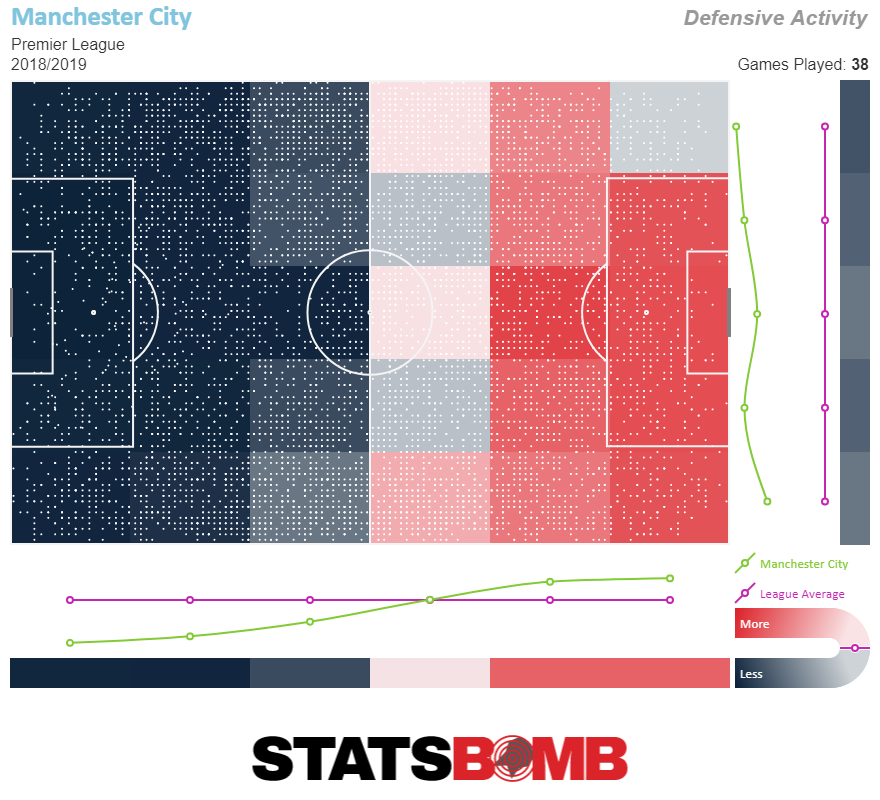

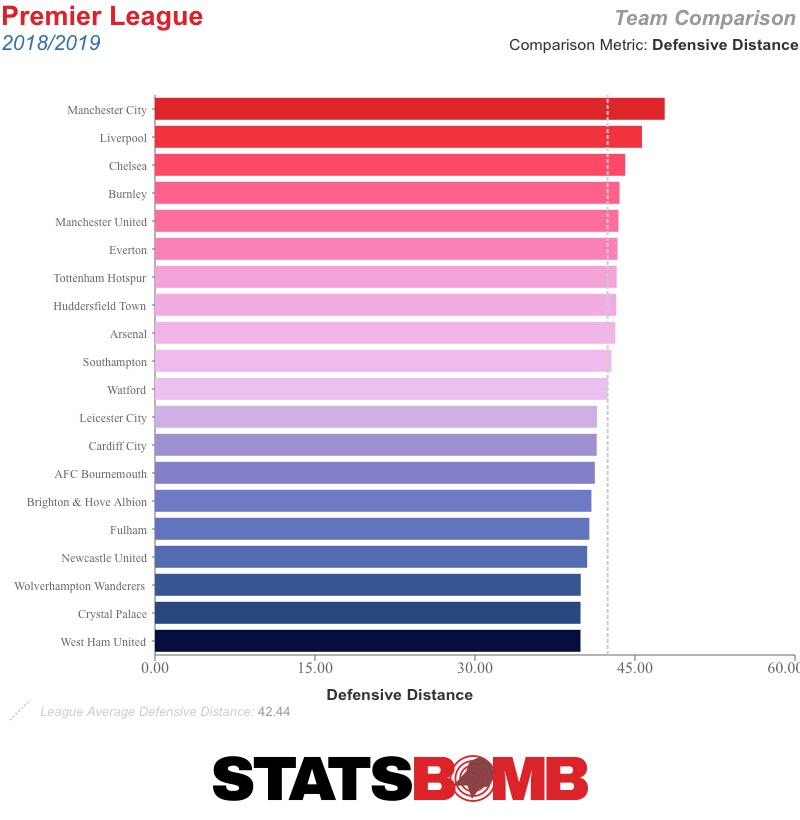

The reality is that City do the vast majority of their defending well away from their own goal. The responsibility of the 2.5 left minding the back line is to snuff out any hopeful long balls that come pinging their way, to deny the escape valve from this suffocation.

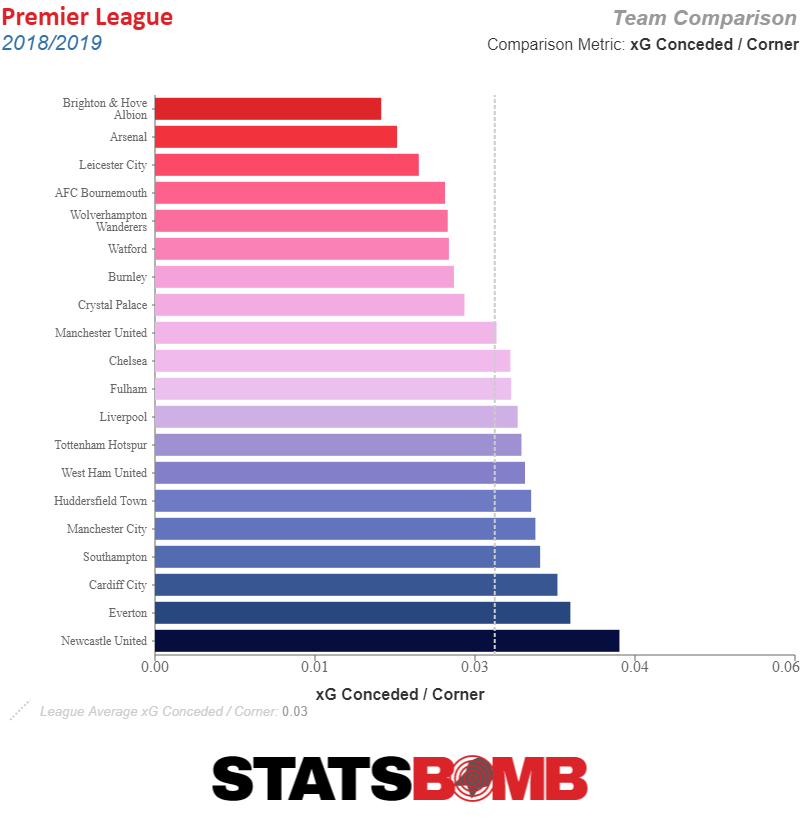

It’s not an easy job, but it’s not a typical defensive one either. The challenge for Guardiola is finding players who can do it, while also being able to do the traditional jobs of defending set pieces and physically controlling the penalty box when called upon to do so. It’s exceedingly difficult to find something that City don’t excel at but dig deep enough, and you see that they’re actually fairly average when it comes to xG per corner conceded (although the margins between everybody are fairly small)

It’s a completely worthwhile tradeoff to make, of course, being slightly average when you give up a corner kick in order to have defenders who can contribute to entirely pinning opposition in their own half. But it is a tradeoff. And it's one the team looks likely to lean even further into this season.

The distribution of minutes across City’s back line remains a question mark. Laporte always plays (and seems to already be on his way back to the lineup after an injury scare), but the only two other true center backs on the roster are his most likely partner John Stones, and then Nikolas Otamendi who isn’t exactly a rock. The rest of the minutes are anybody’s guess. Maybe Fernandinho just migrates there permanently, or Walker moves inside with Cancelo starting to his right. Maybe we start to see some truly wild alignments, back threes that have both Walker and Fernandinho in them as Guardiola attempts to keep pushing the tactical envelope. Will it work? Probably. Is there a chance it goes haywire? There's at least a small one.

This entire exercise though has just been a testament to how hard it is to come up with a narrative where City don’t win the title. There are of course the usual ravages of fate. A devastating string of injuries could befall them, or the fates could decide that Sergio Aguero will fall down every time he kicks a ball for the rest of his life. But, within the normal bounds of luck what we’re looking at is trying to find the tiniest of fissures and extrapolating outward into how they might become actual problems. Maybe Sané’s injury handcuffs Guardiola enough tactically to start the ball rolling, maybe the slightly imperfect attacking alignment in front of him causes Rodri to have a harder time adjusting to the more physical Premier League, and maybe that allows opponents to get at a creatively rethought back line more potently. It’s certainly not likely, but given the last two seasons, nothing is. The rest of the league will have to take solace in the fact that it’s not impossible.

Header image courtesy of the Press Association

Header image courtesy of the Press Association

Header image courtesy of the Press Association

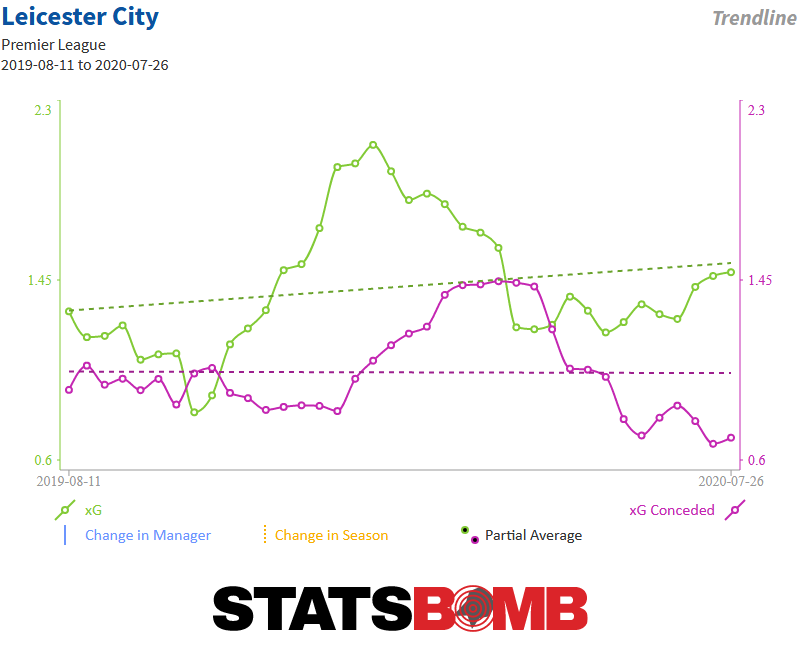

Another difference, albeit a slighter one, between Puel and Rodgers was how the team defended and their ability to turn defense into offense. Under Rodgers, Leicester were around league average in how high up the pitch they made defensive actions, and above league average in passes per defensive action. Leicester were similarly solid but unspectacular in generating transition opportunities, ranking ninth in shots coming via a defensive action in the opposition half in five or less seconds and eighth in counter attacking shots. No one would confuse them with being an incredible pressing side that turned turnovers into scoring chances at will, but they were able to do it at a greater frequency than during the earlier parts of the season. Now, there are ways to poke holes at Leicester's promising performance during the final 2.5 months of the season. For one, we only have 10 games of evidence with Rodgers at the helm and those games came at the end of the season. While playing well in a 10 game sample size isn't something to turn your nose up at, it's still a small enough number that various factors could play a role in that success. Their schedule was also rather weird. While Leicester did perform admirably against Arsenal, Manchester City and Chelsea to end the season; they also got to play the likes of Fulham, West Ham, Huddersfield, Watford when they were on their second half slide, and Bournemouth.

Another difference, albeit a slighter one, between Puel and Rodgers was how the team defended and their ability to turn defense into offense. Under Rodgers, Leicester were around league average in how high up the pitch they made defensive actions, and above league average in passes per defensive action. Leicester were similarly solid but unspectacular in generating transition opportunities, ranking ninth in shots coming via a defensive action in the opposition half in five or less seconds and eighth in counter attacking shots. No one would confuse them with being an incredible pressing side that turned turnovers into scoring chances at will, but they were able to do it at a greater frequency than during the earlier parts of the season. Now, there are ways to poke holes at Leicester's promising performance during the final 2.5 months of the season. For one, we only have 10 games of evidence with Rodgers at the helm and those games came at the end of the season. While playing well in a 10 game sample size isn't something to turn your nose up at, it's still a small enough number that various factors could play a role in that success. Their schedule was also rather weird. While Leicester did perform admirably against Arsenal, Manchester City and Chelsea to end the season; they also got to play the likes of Fulham, West Ham, Huddersfield, Watford when they were on their second half slide, and Bournemouth.

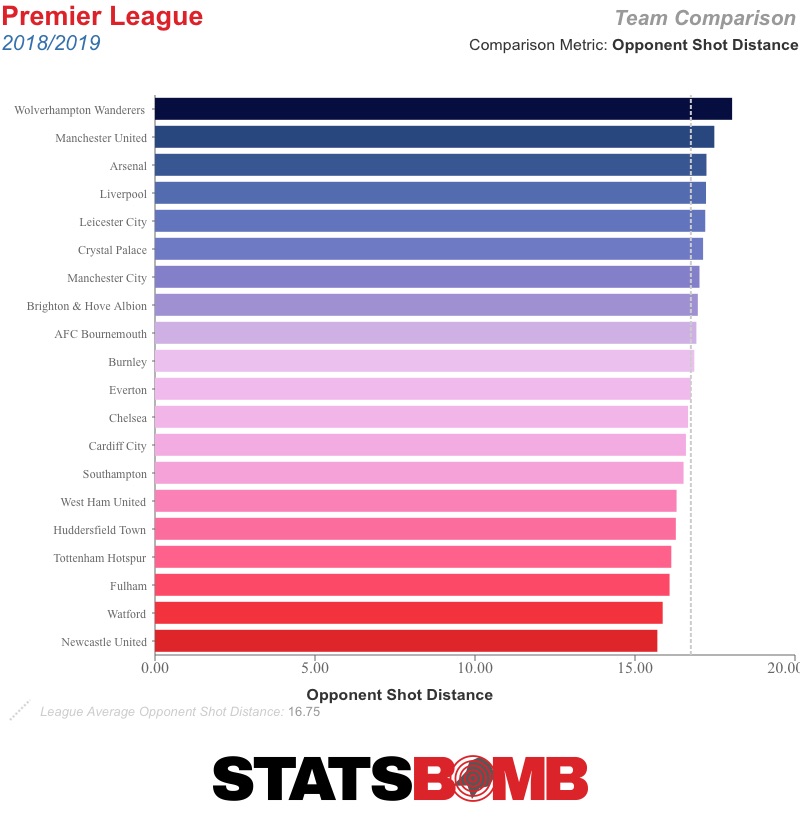

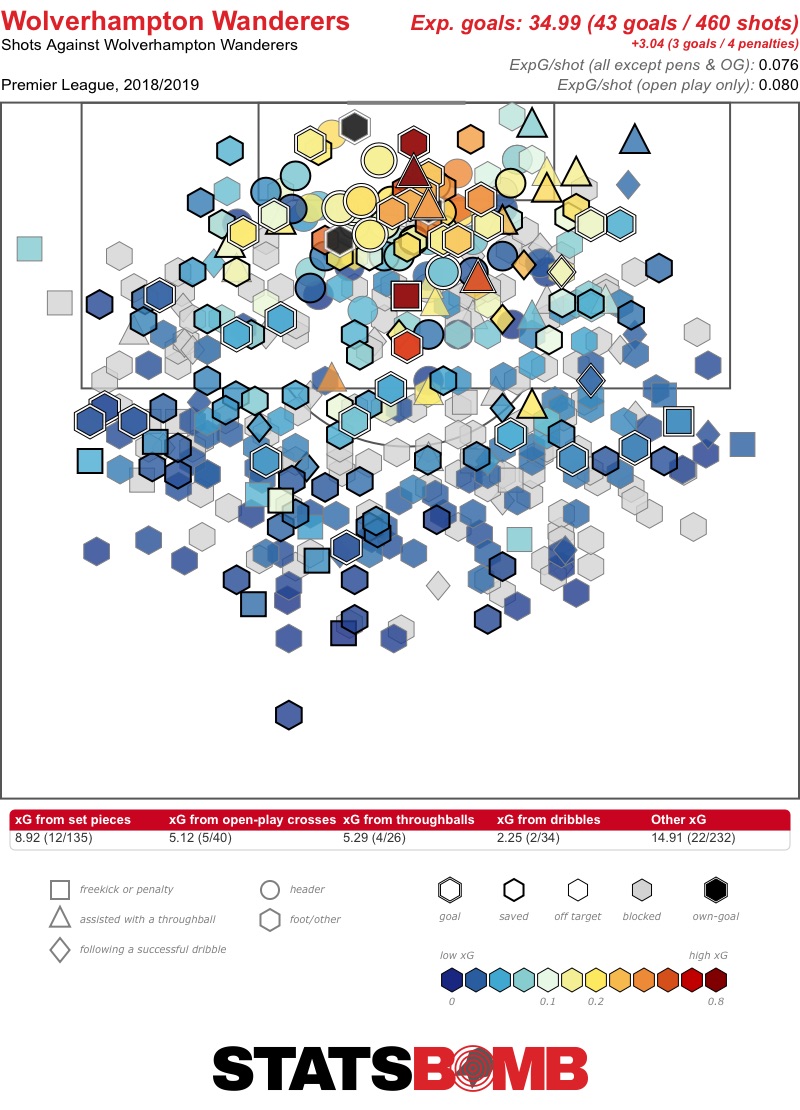

Wolves conceded slightly fewer shots than the average team, and what shots they did concede were long and with bodies in the way (read: low quality.) Those are all markers of a team that doesn’t concede many expected goals. Wolves actually conceded the fourth fewest expected goals (0.91/90 minutes) in the Premier League. They fared slightly worse in practice, conceding 8 more goals than expected. This doesn’t appear to have been a case of a goalkeeper letting down an excellent defence; Rui Patricio was basically a league-average stopper. Despite some bad luck, Wolves still tied for the fifth-best defence in the Premier League last season.

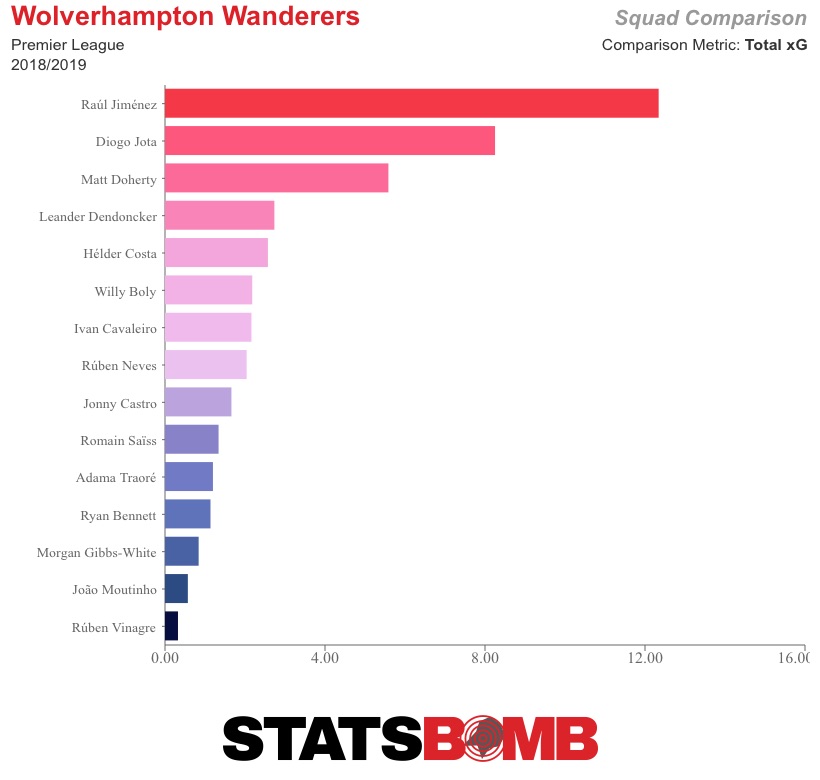

Wolves conceded slightly fewer shots than the average team, and what shots they did concede were long and with bodies in the way (read: low quality.) Those are all markers of a team that doesn’t concede many expected goals. Wolves actually conceded the fourth fewest expected goals (0.91/90 minutes) in the Premier League. They fared slightly worse in practice, conceding 8 more goals than expected. This doesn’t appear to have been a case of a goalkeeper letting down an excellent defence; Rui Patricio was basically a league-average stopper. Despite some bad luck, Wolves still tied for the fifth-best defence in the Premier League last season.  Nuno’s defensive blueprint — a back 5, midfielders who sit in front of the penalty box, refusing to overcommit in attack — dictated how his team attacked. Forwards Raúl Jiménez and Diogo Jota did the lion’s share of the team’s attacking work. For the first half of the season, Nuno deployed Hélder Costa as a third forward alongside Jota and Jiménez. Midfielder Leander Dendoncker replaced him in January as Wolves switched to more of a midfield three and contributed about as much in attack. In either configuration, fullback Matt Doherty served as an auxiliary forward when Wolves moved up the pitch and was their third goalscoring threat.

Nuno’s defensive blueprint — a back 5, midfielders who sit in front of the penalty box, refusing to overcommit in attack — dictated how his team attacked. Forwards Raúl Jiménez and Diogo Jota did the lion’s share of the team’s attacking work. For the first half of the season, Nuno deployed Hélder Costa as a third forward alongside Jota and Jiménez. Midfielder Leander Dendoncker replaced him in January as Wolves switched to more of a midfield three and contributed about as much in attack. In either configuration, fullback Matt Doherty served as an auxiliary forward when Wolves moved up the pitch and was their third goalscoring threat.  This may not sound like an inspiring attacking plan, but it worked well enough. Despite indifferent finishing, Jiménez scored 11 goals and created a bevy of chances for his teammates. At 32, Joao Moutinho was still able to provide assists from midfield. Wolves generated the seventh-most expected goals in the Premier League while playing cautiously. By just about any metric, they were a league-average attacking team. (There is no tension between those statements; the greatness of Man City and Liverpool skewed the average.) Between this wholly adequate attack and Nuno’s stifling defence, Wolves had the fourth-best expected goals difference in the league last season. Ahead of the 2019-20 season, Wolves are a sneaky pick to deliver on last year’s top-four promise. A repeat of last year’s performances, the theory goes, could be enough — especially with Chelsea, Manchester United, and Arsenal in varying states of disarray. Would that it were so simple. Even if other teams stagnate, this scenario presupposes that Nuno will get the same performances out of his squad and then somehow avoid any of the losses to smaller clubs that kept his team out of last year’s top six.

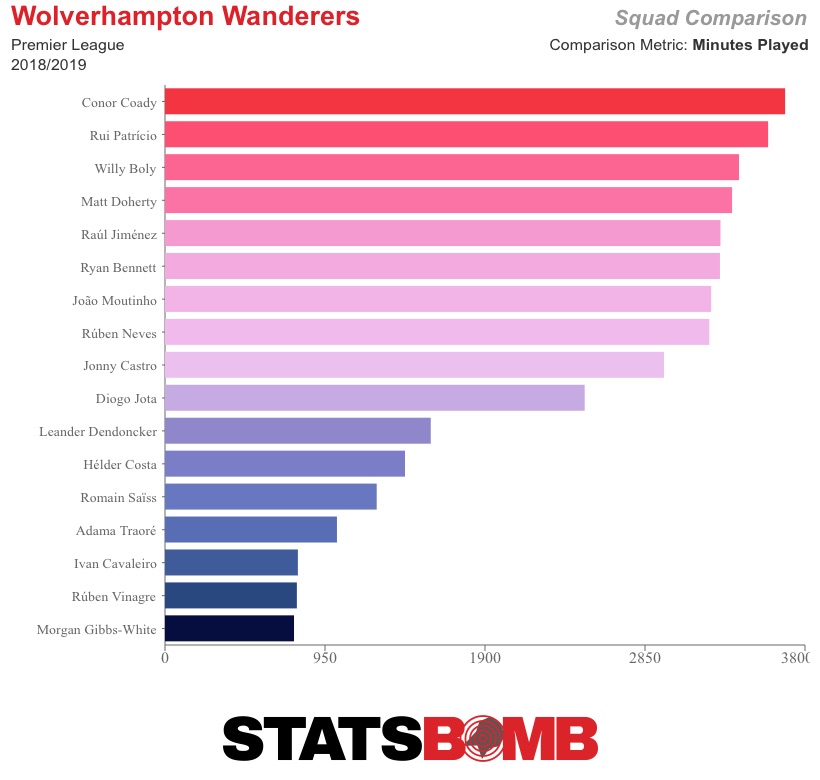

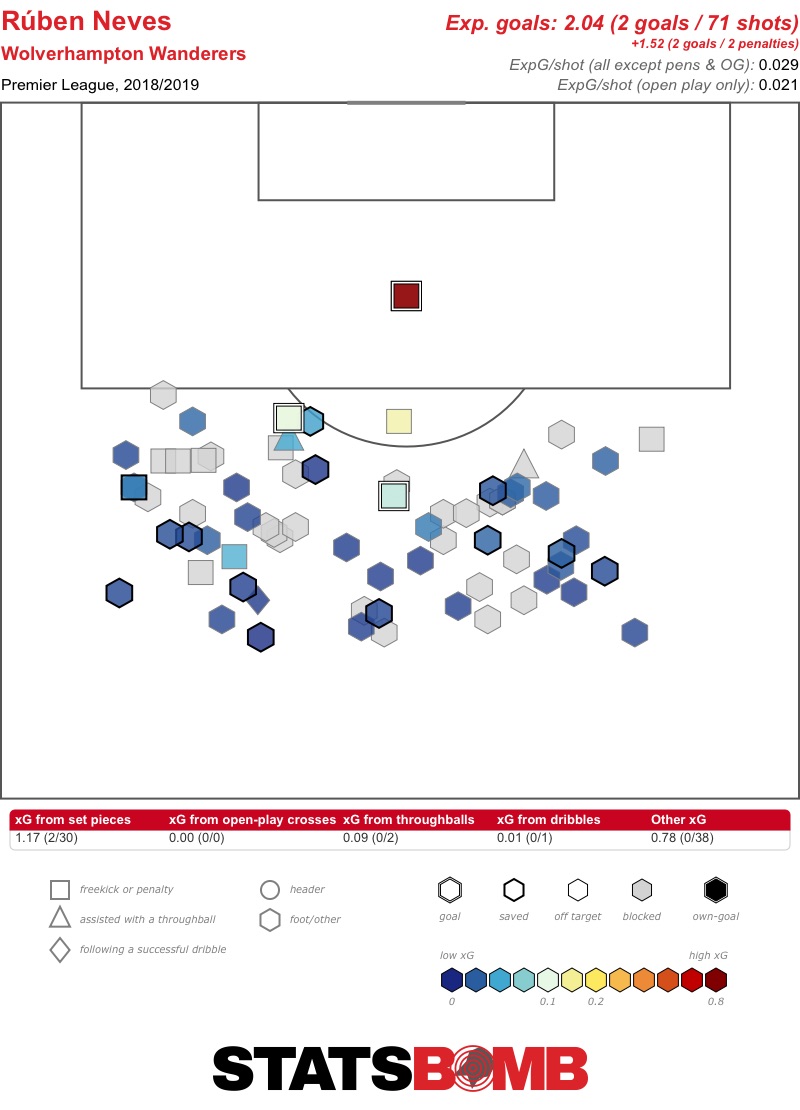

This may not sound like an inspiring attacking plan, but it worked well enough. Despite indifferent finishing, Jiménez scored 11 goals and created a bevy of chances for his teammates. At 32, Joao Moutinho was still able to provide assists from midfield. Wolves generated the seventh-most expected goals in the Premier League while playing cautiously. By just about any metric, they were a league-average attacking team. (There is no tension between those statements; the greatness of Man City and Liverpool skewed the average.) Between this wholly adequate attack and Nuno’s stifling defence, Wolves had the fourth-best expected goals difference in the league last season. Ahead of the 2019-20 season, Wolves are a sneaky pick to deliver on last year’s top-four promise. A repeat of last year’s performances, the theory goes, could be enough — especially with Chelsea, Manchester United, and Arsenal in varying states of disarray. Would that it were so simple. Even if other teams stagnate, this scenario presupposes that Nuno will get the same performances out of his squad and then somehow avoid any of the losses to smaller clubs that kept his team out of last year’s top six.  Nuno was able to use the same starters in almost every match last season. Eight outfield players logged more than 3,000 minutes in the Premier League. Diogo Jota, who suffered a mid-season ankle injury, was still played for 2,492 minutes. Costa and Dendoncker, his replacement in the lineup, provided a combined 3,003 minutes in the final outfield spot. Wolves had interesting players on the bench — Morgan Gibbs-White and Ruben Vinagre are promising youngsters; Adama Traoré is still close to that designation — but they were never overextended. What are the odds of Wolves not suffering an injury worse than Jota’s five-match ankle absence in consecutive seasons? Teams can be considered healthy without getting that lucky. With a Europa League campaign beginning in late July, there will be more demands on Nuno’s deliberately small squad this season. Even if Gibbs-White and Vinagre contribute more in their second Premier League seasons, Nuno will likely have to give more minutes to lesser players. Converting Jiménez and Dendoncker’s loans into permanent transfers, as Wolves have done, doesn’t address these limitations. Patrick Cutrone, signed for £16m from Milan, should provide forward depth where there previously was none. He provided an interesting combination of shot quality and pressing work as a 20 year old in 2017-18, but is coming off a campaign where everything but the pressing disappeared. Cutrone, who is still young and spent last year on a distinctly weird Milan team, has a decent chance of bouncing back. Wolves surely expect as much. If Nuno can get Cutrone to reach or exceed the shot volume of a league-average striker — something he has never done — he could prove to be quite the bargain. It’s been an otherwise quiet summer for Wolves. Portuguese youngsters Bruno Jordão and Pedro Neto, a central midfielder and Jorge Mendes-represented winger, respectively, were signed from Lazio. The 20-year-old Jordão played 1,168 minutes in the Portuguese second division in 2016-17. Beyond that, neither he nor the 19-year-old Neto have much of a track record. 22-year-old Real Madrid defender and Jorge Mendes client Jesús Vallejo has also arrived on loan. The club has an excellent history with these kinds of moves: Diogo Jota, centreback Willy Boly, and leftback Jonny all arrived on loan before making permanent transfers. (What could explain this? Truly, it’s a mystery!) Other players, perhaps of the Portuguese-agented variety may be signed in the coming days, but none of these moves suggest serious change is afoot at Molineux Stadium this season. “Last year’s Wolves with minor upgrades” still has a certain appeal. While Wolves were fortunate with injuries last season, they had some bad luck in conceding more goals than expected and were superior in losses to Cardiff, Huddersfield, and Brighton as well as draws with Fulham and Newcastle. Those kinds of matches going the other way this season could be enough to finish between fourth and sixth. Moreover, Wolves’ squad has a promising age profile. Moutinho is the only outfield player on the wrong side of 30. Diogo Jota and midfielder Rúben Neves are just 22, Dendoncker is 24, and Jonny is 25. These players improving, which would not be unexpected, could make up for the team’s other problems. But were Wolves simply unlucky against weaker sides last season? While clubs generally fare well when generating more expected goals than their opponents, losing when you’ve produced 0.38 or 0.24 more expected goals — as Wolves did against Cardiff and Burnley, respectively — is not that unusual. Nuno’s focus on keeping matches close didn’t just lessen the gap between Wolves and superior teams; it also made life easier for weaker sides. Defeating Arsenal and Chelsea and drawing with both Mancunian sides does little for your league finish if you keep dropping points against relegation candidates. Wolves were a more interesting best-of-the-rest team than the Evertonian sides of yore, which simply beat up on minnows, but it’s not such a surprise that they ended up in the same place. Even if Nuno decides to attack weaker sides, it’s not clear he has the team for such a two-track approach. Wolves’ midfield is not a green light away from racking up goals. Moutinho has scored 10 league goals since leaving Portugal...six years ago. Neves’ 71 shots last season were the second-most on the team. His two non-penalty goals came from potshots from distance and the only two shots he took inside the penalty box were penalties, both of which he converted.

Nuno was able to use the same starters in almost every match last season. Eight outfield players logged more than 3,000 minutes in the Premier League. Diogo Jota, who suffered a mid-season ankle injury, was still played for 2,492 minutes. Costa and Dendoncker, his replacement in the lineup, provided a combined 3,003 minutes in the final outfield spot. Wolves had interesting players on the bench — Morgan Gibbs-White and Ruben Vinagre are promising youngsters; Adama Traoré is still close to that designation — but they were never overextended. What are the odds of Wolves not suffering an injury worse than Jota’s five-match ankle absence in consecutive seasons? Teams can be considered healthy without getting that lucky. With a Europa League campaign beginning in late July, there will be more demands on Nuno’s deliberately small squad this season. Even if Gibbs-White and Vinagre contribute more in their second Premier League seasons, Nuno will likely have to give more minutes to lesser players. Converting Jiménez and Dendoncker’s loans into permanent transfers, as Wolves have done, doesn’t address these limitations. Patrick Cutrone, signed for £16m from Milan, should provide forward depth where there previously was none. He provided an interesting combination of shot quality and pressing work as a 20 year old in 2017-18, but is coming off a campaign where everything but the pressing disappeared. Cutrone, who is still young and spent last year on a distinctly weird Milan team, has a decent chance of bouncing back. Wolves surely expect as much. If Nuno can get Cutrone to reach or exceed the shot volume of a league-average striker — something he has never done — he could prove to be quite the bargain. It’s been an otherwise quiet summer for Wolves. Portuguese youngsters Bruno Jordão and Pedro Neto, a central midfielder and Jorge Mendes-represented winger, respectively, were signed from Lazio. The 20-year-old Jordão played 1,168 minutes in the Portuguese second division in 2016-17. Beyond that, neither he nor the 19-year-old Neto have much of a track record. 22-year-old Real Madrid defender and Jorge Mendes client Jesús Vallejo has also arrived on loan. The club has an excellent history with these kinds of moves: Diogo Jota, centreback Willy Boly, and leftback Jonny all arrived on loan before making permanent transfers. (What could explain this? Truly, it’s a mystery!) Other players, perhaps of the Portuguese-agented variety may be signed in the coming days, but none of these moves suggest serious change is afoot at Molineux Stadium this season. “Last year’s Wolves with minor upgrades” still has a certain appeal. While Wolves were fortunate with injuries last season, they had some bad luck in conceding more goals than expected and were superior in losses to Cardiff, Huddersfield, and Brighton as well as draws with Fulham and Newcastle. Those kinds of matches going the other way this season could be enough to finish between fourth and sixth. Moreover, Wolves’ squad has a promising age profile. Moutinho is the only outfield player on the wrong side of 30. Diogo Jota and midfielder Rúben Neves are just 22, Dendoncker is 24, and Jonny is 25. These players improving, which would not be unexpected, could make up for the team’s other problems. But were Wolves simply unlucky against weaker sides last season? While clubs generally fare well when generating more expected goals than their opponents, losing when you’ve produced 0.38 or 0.24 more expected goals — as Wolves did against Cardiff and Burnley, respectively — is not that unusual. Nuno’s focus on keeping matches close didn’t just lessen the gap between Wolves and superior teams; it also made life easier for weaker sides. Defeating Arsenal and Chelsea and drawing with both Mancunian sides does little for your league finish if you keep dropping points against relegation candidates. Wolves were a more interesting best-of-the-rest team than the Evertonian sides of yore, which simply beat up on minnows, but it’s not such a surprise that they ended up in the same place. Even if Nuno decides to attack weaker sides, it’s not clear he has the team for such a two-track approach. Wolves’ midfield is not a green light away from racking up goals. Moutinho has scored 10 league goals since leaving Portugal...six years ago. Neves’ 71 shots last season were the second-most on the team. His two non-penalty goals came from potshots from distance and the only two shots he took inside the penalty box were penalties, both of which he converted.  Dendocker, who scored two goals (2.6xG) in his half-season, is a defensive midfielder. He has never scored more than three goals in a league season. Like N’Golo Kanté under Maurizio Sarri, he was tasked with being an additional body running into the box. Willing midfielders can score a few goals in that role, but that doesn’t make them Marek Hamsik. Nuno telling his players to attack the likes of Newcastle might be enough to solve last year’s problems, but it won’t be pretty. Nuno may soon understand why Jay Fai wanted to return her Michelin star. Last season, when Wolves were a newly-promoted team, an underdog if you didn’t think too hard about their ownership and funding, it didn’t matter that they were occasionally confounding. This season, as the reigning best-of-the-rest and a top-six contender, those traits may read differently. A repeat of last season’s struggles against limited sides, even if it isn’t tremendously consequential, won’t be as easily shrugged off. Recognition will do that to you. Predictions about Wolves, even more than most clubs, are largely an indicator of how one feels about their Premier League rivals. Nuno’s plan is clear; his rivals remain in flux. If everything goes right, if Wolves are as healthy as last year, win all their close games and perform in line with their expected goals, the final Champions League spot should be theirs. The likelier — and more boring — scenario is that Wolves will enjoy slightly better luck against minnows, pick up fewer points against top-six rivals, and suffer a few more injuries. All of this would average out to a similar point total, but a less captivating season. Wolves could easily wind up in seventh in that scenario. With all the issues at Chelsea, Arsenal, and Manchester United, though, it’s tempting to think they’ll break into the top six. They’re good at a few very specific things, and we’re about to see how far that can take them. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

Dendocker, who scored two goals (2.6xG) in his half-season, is a defensive midfielder. He has never scored more than three goals in a league season. Like N’Golo Kanté under Maurizio Sarri, he was tasked with being an additional body running into the box. Willing midfielders can score a few goals in that role, but that doesn’t make them Marek Hamsik. Nuno telling his players to attack the likes of Newcastle might be enough to solve last year’s problems, but it won’t be pretty. Nuno may soon understand why Jay Fai wanted to return her Michelin star. Last season, when Wolves were a newly-promoted team, an underdog if you didn’t think too hard about their ownership and funding, it didn’t matter that they were occasionally confounding. This season, as the reigning best-of-the-rest and a top-six contender, those traits may read differently. A repeat of last season’s struggles against limited sides, even if it isn’t tremendously consequential, won’t be as easily shrugged off. Recognition will do that to you. Predictions about Wolves, even more than most clubs, are largely an indicator of how one feels about their Premier League rivals. Nuno’s plan is clear; his rivals remain in flux. If everything goes right, if Wolves are as healthy as last year, win all their close games and perform in line with their expected goals, the final Champions League spot should be theirs. The likelier — and more boring — scenario is that Wolves will enjoy slightly better luck against minnows, pick up fewer points against top-six rivals, and suffer a few more injuries. All of this would average out to a similar point total, but a less captivating season. Wolves could easily wind up in seventh in that scenario. With all the issues at Chelsea, Arsenal, and Manchester United, though, it’s tempting to think they’ll break into the top six. They’re good at a few very specific things, and we’re about to see how far that can take them. Header image courtesy of the Press Association