Tag: Player Analysis

Messi Moments with Álex Delmás: Real Betis 1 - 4 Barcelona, March 2019

We conclude our series on the evolution of Lionel Messi with a look at the Messi of recent seasons. We once again have Álex Delmás, ex-footballer, analyst for Barça TV and author of the book Messi Táctico, alongside us to assist in analysing the trajectory of one of the best players in the history of our sport.

Thanks to our Messi Data Biography we have data for all league matches involving Messi since his debut in 2004. For this series, Álex has picked out three significant matches in Messi’s evolution as a footballer.

We’ve already analysed the first iteration of Messi in the context of the March 2007 Clásico; and the second in the context of another Clásico, the famous 6-2 Barcelona win in May 2009. In this final part of the series, we’re going to look at a 4-1 win away to Real Betis (coached by the current Barcelona head coach Quique Setién) in March 2019.

Nick Dorrington (ND) (editor of StatsBomb’s Spanish-language site): Hi Álex. Can you tell me why you picked this match?

Álex Delmás (AD): I chose this match because here we see a more rounded, mature and complete version of Messi. It was between 2009 and 2012, in the era of Pep Guardiola, that I think the synergy between the level of Messi and the collective reached its highest point. From then onwards, Messi has continued to develop as a footballer at the same time that the collective level of the team has dropped off. And this is the perfect match to help us understand Messi’s new and current status within the team.

ND: In part two of this series, we talked about the Messi of the Guardiola years, and in this part we’re going to talk about his role in Ernesto Valverde’s Barcelona. But before we do that, can you give us a quick overview of Messi’s role in the period between Guardiola’s departure and Valverde’s arrival?

AD: Before Guardiola, he was primarily a player who operated down the right flank, as we saw in the first part of this series. With Guardiola, in the 6-2 match we watched last week, his position changed to that of a false nine, and with spectacular effect.

When Luis Enrique came in, and with the signings of Neymar and Luis Suárez, a few nuances were lost that meant the team didn’t interpret play as well with Messi as a false nine. There was less balance between playing between the lines and seeking to get in behind. In large part because the team lost players who were important in maintaining that balance, such as Samuel Eto’o, Thierry Henry and Pedro. So Luis Enrique placed Messi back on the right flank to form an unstoppable front three with Neymar and Suárez that yielded the second treble in Barcelona’s history.

ND: As we noted last week, in our database only the 2008-09 team had a better expected goal (xG) difference than that 2014-15 side.

AD: But Messi wasn’t the same player as when he had previously played on the right. Now, it was just a starting point from which to move infield and combine in central areas. As the years have passed that tendency has amplified, and it reached its peak under Valverde.

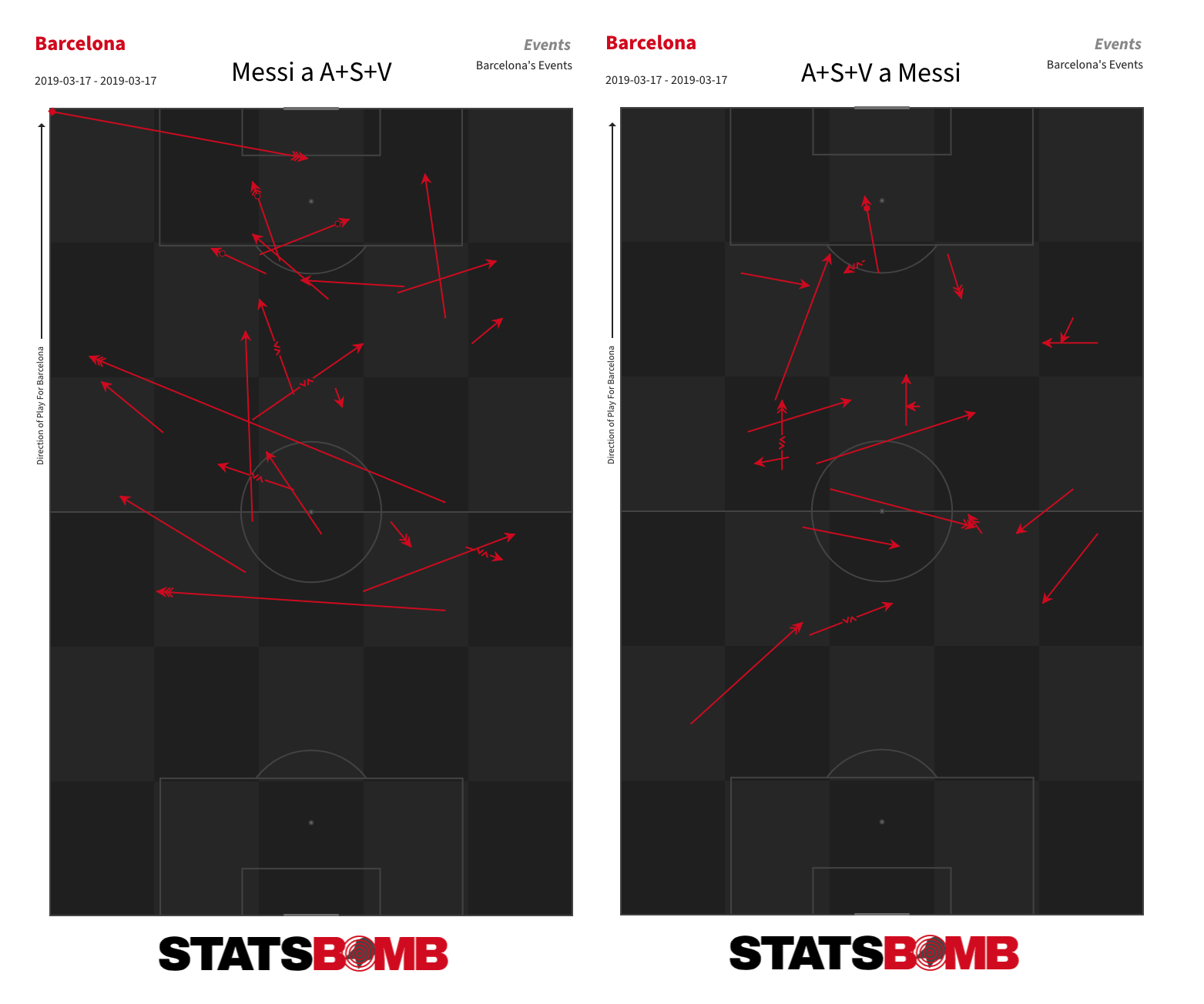

ND: We can see that in these maps of Messi’s attacking touches over the course of the last three seasons. He is now doing the majority of his offensive work in central areas and is much more involved in the construction of play in the midfield zone.

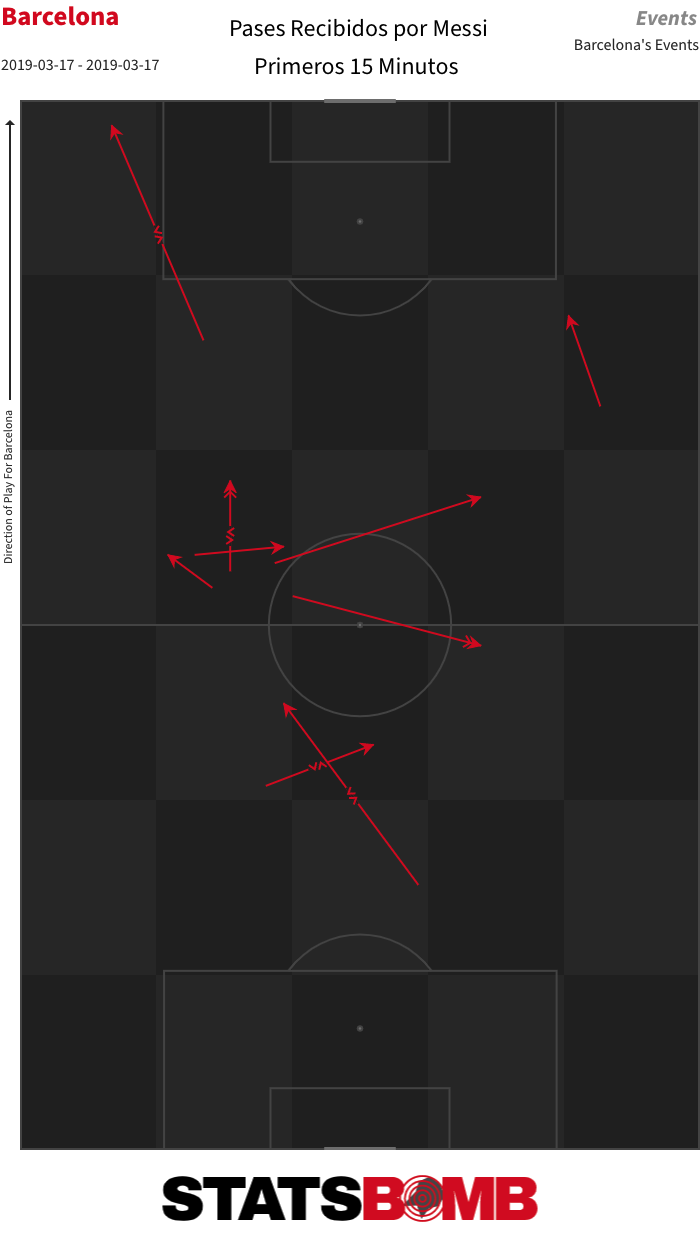

AD: Messi is increasingly more of a midfielder than a forward. He comes back to receive the ball in the centre of the pitch. In this match, Betis pressed intensely in the opening exchanges, and Barcelona needed Messi to drop back and help them advance the ball forward.

When Messi picks up the ball in deeper areas, he has a particular manoeuvre that he has developed over the years and which he also uses to give himself time to get into goalscoring positions, and that is pivoting movements with teammates further up the pitch. Suárez through the centre and Jordi Alba on the left are those with whom he has the best understanding in these movements. Also with Arturo Vidal, who makes runs ahead of him and returns one-twos.

ND: Messi scores a hat-trick in this match. After a good start from Betis, it is him who opens the scoring in the 15th minute with an exquisite freekick. As you mentioned in the first part of this series, that is an aspect of his game he has improved as the years have passed.

AD: Yes. His freekicks are one of the most evident examples of Messi’s spectacular and progressive development. In the youth teams and when he moved up to the first team, he didn’t even think about stepping up to take them.

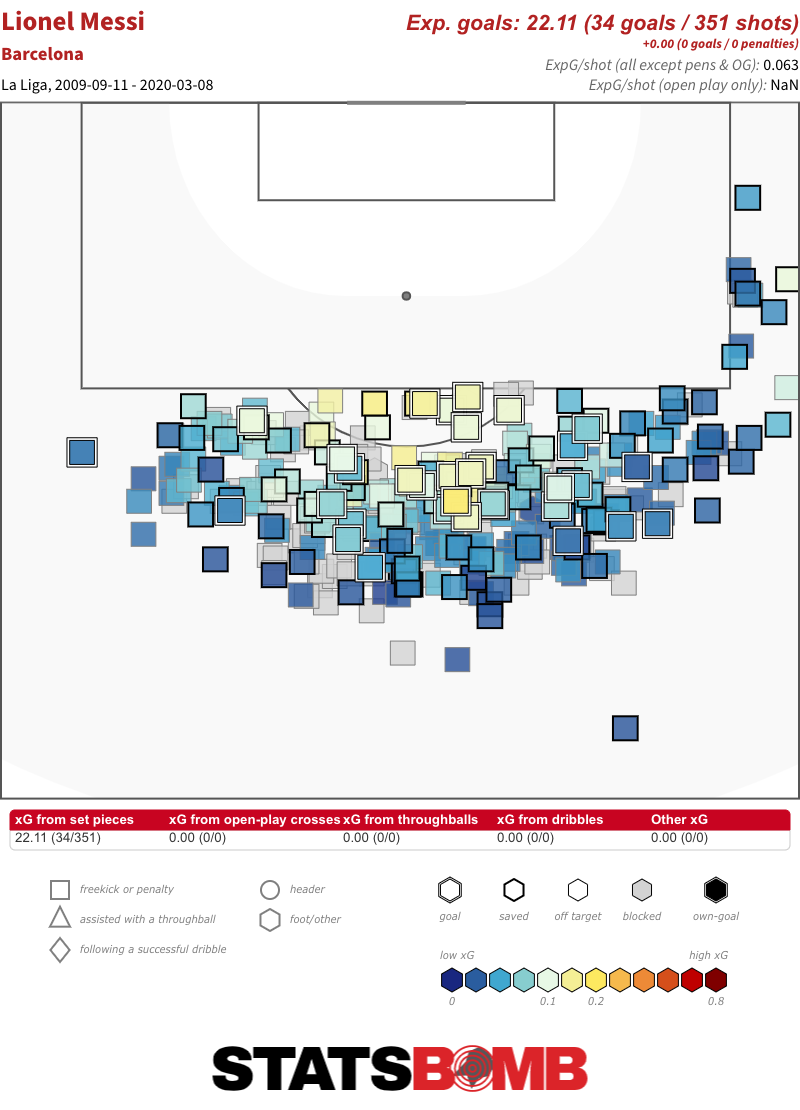

ND: Now, Messi is one of the few players for whom we have enough data to say with some confidence that he is a set-piece specialist.

To what do you attribute this development?

AD: It is said that it was Tito Vilanova, someone who had a lot of influence on Messi, who encouraged him to take and practice freekicks. Messi got to work and soon started scoring goals of all kinds and types. He has become the best freekick taker in the world. His shots are both powerful and well-placed. In time, he has been able to unite those two aspects.

He is now so good at them that opposing teams have started to put additional obstacles in his way, like players on the posts or under the wall, but he still overcomes them.

ND: In fact, in Barcelona’s last match, Real Sociedad did this:

Curious La Real setup to defend Messi free kick pic.twitter.com/whBKUilMBd

— Samuel Marsden (@samuelmarsden) March 7, 2020

Anyway, in this game against Betis, Messi scores the second goal in first-half stoppage time, and then, with the points already won, completes his hat-trick with a delicious first-time lob from the edge of the area.

AD: For me, the best goal of 2019.

ND: But he didn’t just provide the goals. He also set up more chances than any of his teammates.

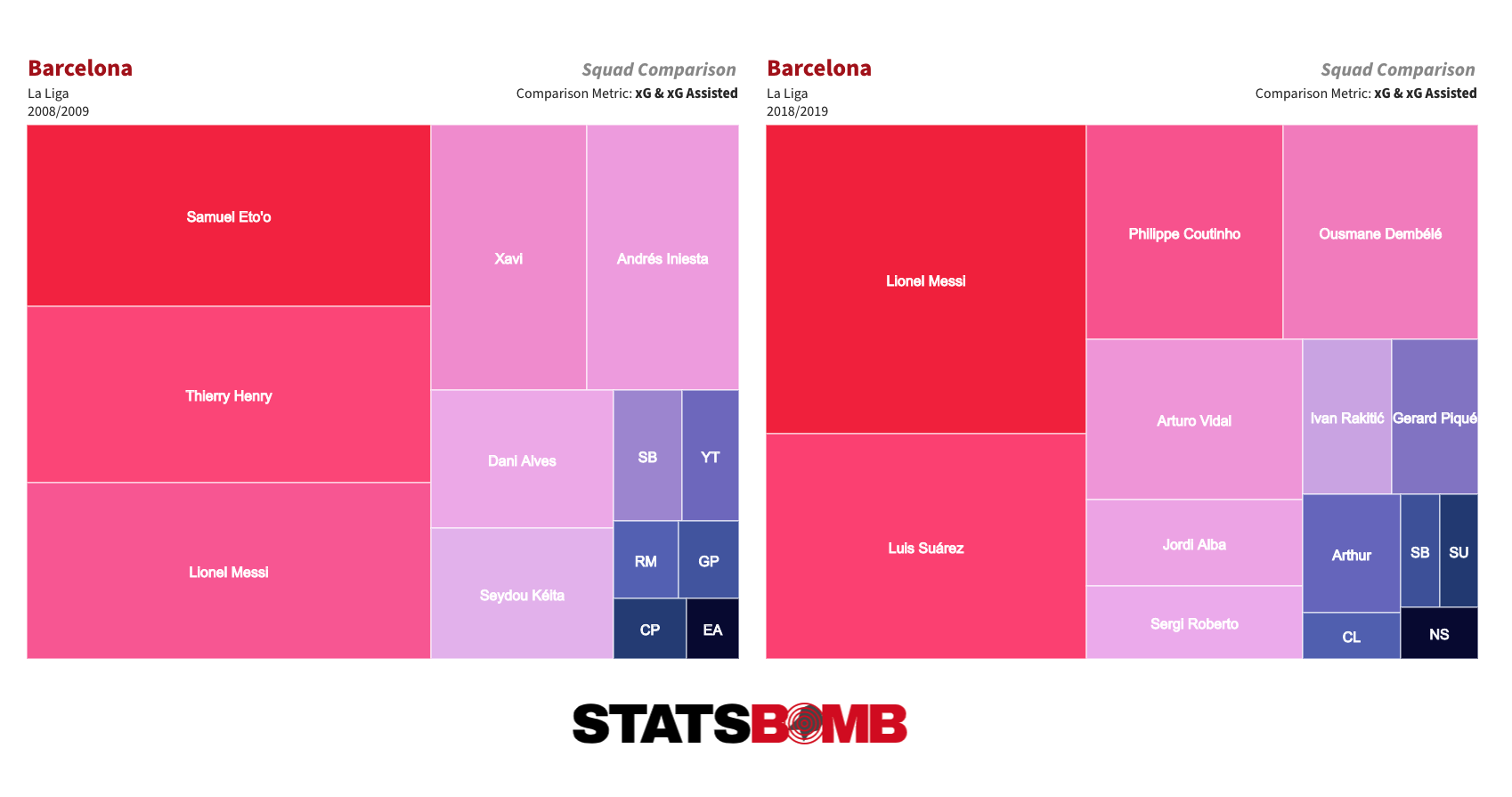

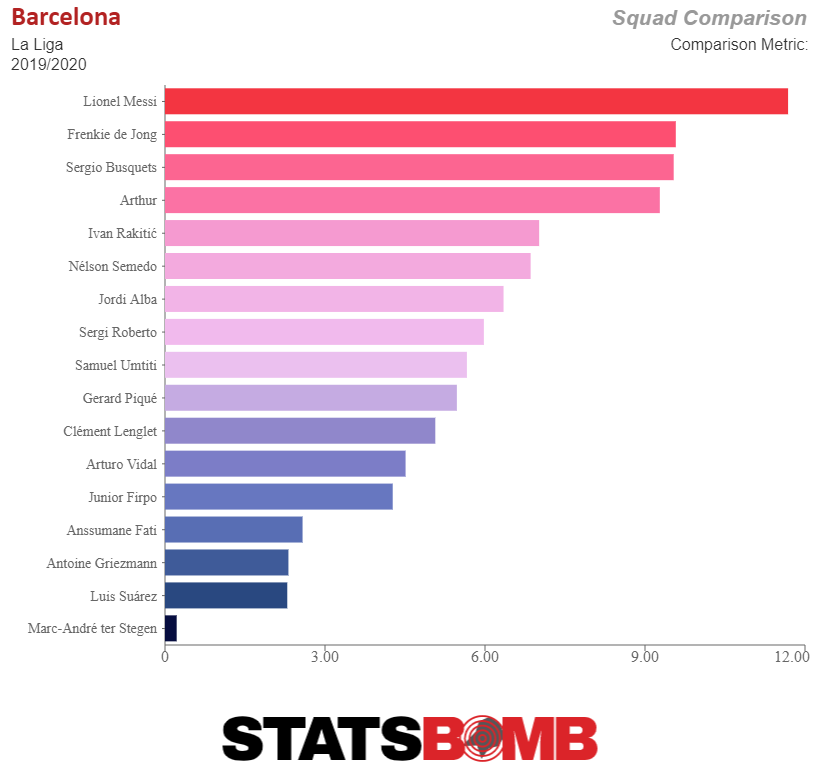

AD: Messi has become so transcendental that he carries pretty all of the team's attacking weight. Excessively so, given that all of the danger comes from him.

ND: We can see that in this graphic that shows the distribution of xG and xG assisted (xGA) between Barcelona’s squad members, first in 2008-09 and then in 2018-19, the season of this match. The distribution is a lot more even in 2008-09.

There are a number of other ways to try and measure the importance of an individual player to their team’s attack. It isn’t a perfect metric by any means, but one that does have a degree of utility is their usage rate. In basic terms, a player’s usage rate measures the percentage of their team’s attacks that end, for good or bad, at their feet.

In each of the last three seasons, including this one, Messi has led La Liga in this metric. In 2017-18, 18.8% of Barcelona’s attack ended at his feet. The figure was 21.2% last season, and has remained pretty much constant this season.

But it isn’t just in the crystallisation of attacks that Messi dominates this team. He also has a fundamental role in ball progression.

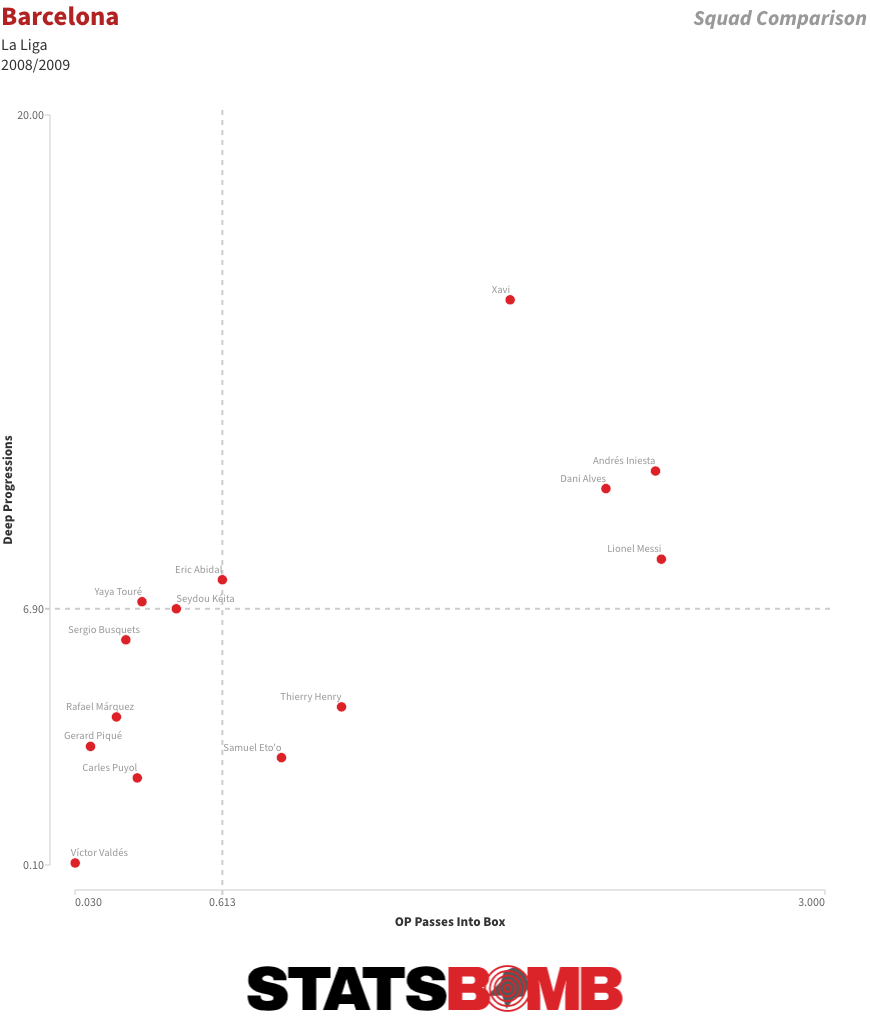

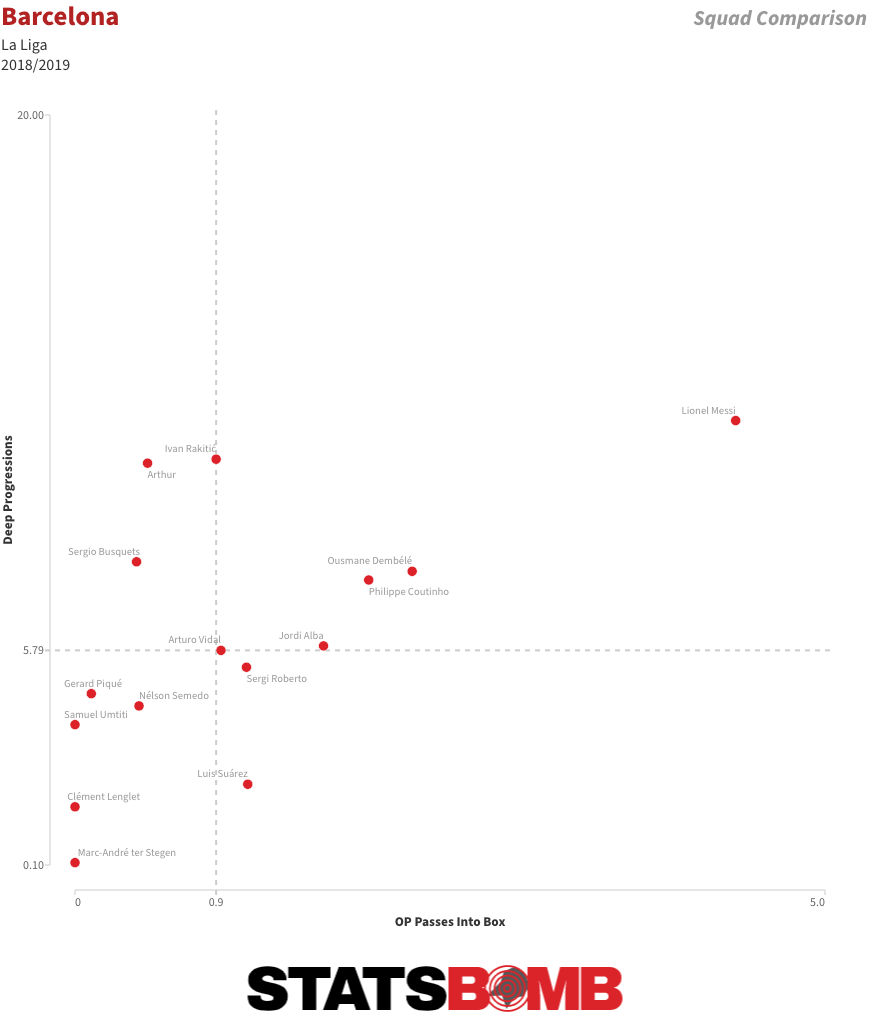

Here are two scatter graphs that plot open-play passes into the penalty area against deep progressions (carries, dribbles or passes into the final third). First, for the 2008-09 season.

In this one, we can see that Messi leads the team in passes into the penalty area but it is Xavi who carries the weight of ball progression into the final third, with Andrés Iniesta and Dani Alves also more involved in that task than Messi. Now, for the 2018-19 season.

These days Messi does everything, and this match is the perfect example. He was the Barcelona player who played the most successful passes, who most often moved the ball into the final third, who played the most passes into the area and who carried the ball more often and over greater distances than any of his teammates. Has there been too much dependence on Messi in recent seasons?

AD: Yes. It has often been the case that there has been too much dependence on Messi. To explain it another way, there have been moments when they haven’t been able to benefit from the extraordinary power of Messi because they’ve relaxed and let him do everything. And that has led to the team no longer applying certain automatisms.

ND: Could you explain what you mean by automatisms?

AD: An automatism is a series of coordinated movements that a team uses to gain an offensive or defensive advantage. An example would be having two wide forwards who are permanently positioned out wide, like we saw in Guardiola’s Barça. That is an automatism that helps create space infield. Or to have one of the full-backs stay back and position himself infield while the other moves forward into attack. Barça no longer apply some of these, like positioning the three central midfielders close together in a triangle shape, like the constant width from the wide forwards, like the off-ball runs of the two advanced central midfielders into the area... small details without apparent importance but that are decisive at the highest level.

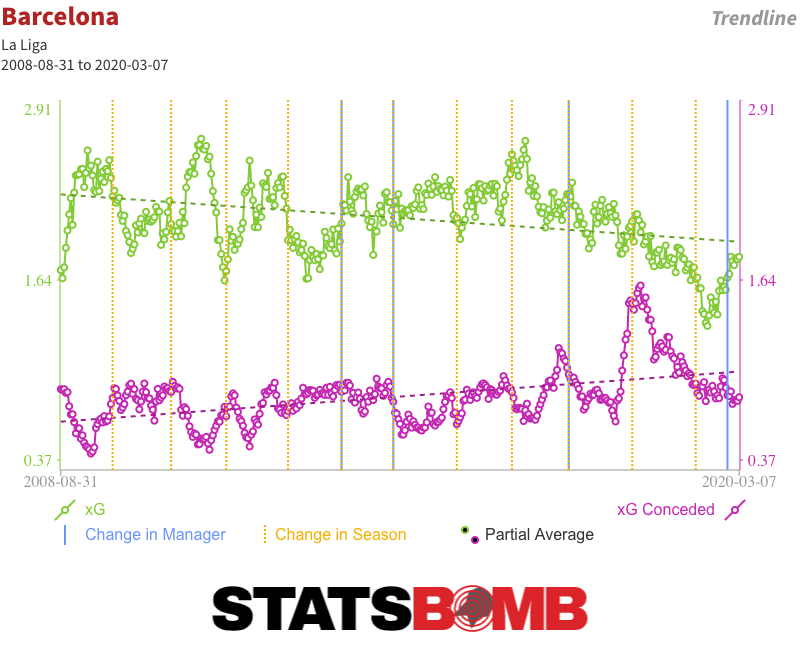

ND: This trendline of Barcelona’s xG and xG conceded (xGC) from Guardiola’s time to the present day (utilising a 15-match rolling average) shows the relative drop off in attacking output in recent years.

The club continue to enjoy success in La Liga, but they’ve discarded certain elements of their previous style and their reliance on Messi to solve everything has perhaps hurt them at a European level.

What do you think has caused this slight change in approach (I say slight because in the context of La Liga, Barça continue to have a profile that is distinct from that of the majority of teams) over the last few years? The coaches? Or is it a natural development given the departure of players like Xavi and Iniesta, two of Messi’s key accomplices?

AD: It’s true. The change is palpable even though it isn’t extraordinary given that Barça continue to be a team who have a high share of possession and who consistently seek to generate attacking football regardless of the situation or opponent. But as I said before, all factors have an influence at the highest level.

I think the change is down to various factors and they are all equally important.

One of those is the coach. Guardiola, Luis Enrique and Valverde are all great coaches but from my vantage point, Guardiola has a special gift for tactics, and especially for hitting upon offensive solutions within the framework of positional play. He is the best possible coach to apply positional play because he practiced it for almost the entirety of his playing career at Barça and also worked under Johan Cruyff.

As is logical and normal, each coach introduces their own nuances to a particular style of play. Luis Enrique exchanged some of the patience in build up play for quicker attacks. It is also worth noting, however, that with such a potent front three, he had to base his team around them. The team stopped doing certain things, like the insistence on circulating the ball, although many other positive elements were preserved.

Valverde decided to try and make the team more robust and applied certain nuances towards that aim. He pulled Ivan Rakitic back closer to Sergio Busquets and so had one less midfielder further up. The team dropped back more readily.

The second factor is the natural evolution of the squad. Over time, and bit by bit, vital players have departed. Players like Carles Puyol, Pedro, Alves, Xavi and Iniesta. In the end, football is about the players.

Finally, Guardiola’s team were the pioneers in applying pressing, attacking football. When a team are a pioneer, they are more difficult to detain. As the years have gone by, opponents were able to develop mechanisms to detain certain aspects of their play.

ND: Okay Álex. First, I want to say thank you for all of your contributions to this series. But I I also have one more question. Across these three matches, we have seen three distinct iterations of Messi. Will there be a fourth between now and the end of his career?

AD: I think so, and I think it will be the one that carries him through the final part of his career. An iteration in which he will probably be less explosive but still just as decisive. I am sure he will become a bit more of a passer and that his goalscoring numbers will drop off slightly, but I also don’t think that will be from a more withdrawn position but simply with full freedom of movement.

But Messi will never stop surprising us! And in the meantime, we can continue to enjoy the best player in the world, perhaps in history.

Thanks to you, to StatsBomb and to the readers. It has been a pleasure to participate in this series.

Messi Moments with Álex Delmás: Real Madrid 2-6 Barcelona, May 2009

Our analysis of the evolution of Lionel Messi continues with another Clásico, two years down the line from the first. We are again joined by Álex Delmás, ex-footballer, analyst for Barça TV and La Vanguardia newspaper, and the author of the book Messi Táctico. Thanks to our Messi Data Biography we have data for all league matches involving Messi since his debut in 2004.

For this series, Álex has picked out three significant matches in Messi’s evolution as a footballer. Last time out, we analysed Messi’s first iteration in the context of the March 2007 Clásico at the Camp Nou. This time around, we are at the Santiago Bernabeu for Barcelona’s famous 6-2 victory in May 2009.

Nick Dorrington (ND) (editor of StatsBomb’s Spanish-language site): Hi Alex. Can you tell me why you picked this match?

Álex Delmás (AD): It is the match that changed Messi’s footballing life. In this match, Pep Guardiola hit upon a brainwave and positioned Messi centrally as a false nine for the first time, a move that elevated Messi’s football to an unmatchable level. He went from being one of the best players in the world to the undisputed best. To top things off, the collective performance in this match is absolutely brilliant. I sincerely think that it is one of the most tactically rich matches in the history of our sport.

ND: The term false nine now seems to form part of the standard football lexicon, but for those who don’t know what it means, could you give us an overview of what a false nine is and which systems it functions best in?

AD: In the false nine role, the player initially lines up as a centre forward, a nine, but doesn’t fulfil the functions that we’d expect of a player in that position. They start off in the centre forward position, but drop back from there as play evolves to act as an attacking midfielder. The role is strongly associated with a 4-3-3 or 3-4-3 system. It has to be utilised in a system with three forwards. At least in my opinion, it is impossible to correctly implement the role of a false nine without wide forwards on each side to pin back the opposition full-backs.

ND: It is worth mentioning that the idea of a free nine, a number nine who drops back to involve himself in the construction of play, wasn’t a new one. Contemporary reports describe the play of centre forwards like Adolfo Pedernera, Nándor Hidekuti or even Alfredo di Stefano in a way that suggests that in the present day we might describe them as false nines. And didn’t Johan Cruyff’s Barcelona side, the Dream Team, often play with Michael Laudrup in a very similar role?

AD: I haven’t ever seen the others you mentioned play, but I did watch the Dream Team and it is true that Cruyff’s side often played with Laudrup as a false nine, and with good results too. In fact, in the 1992 European Cup final at Wembley, the team started with Laudrup as a false nine. Once Romario arrived that variation disappeared or was at least used very sparingly thereafter.

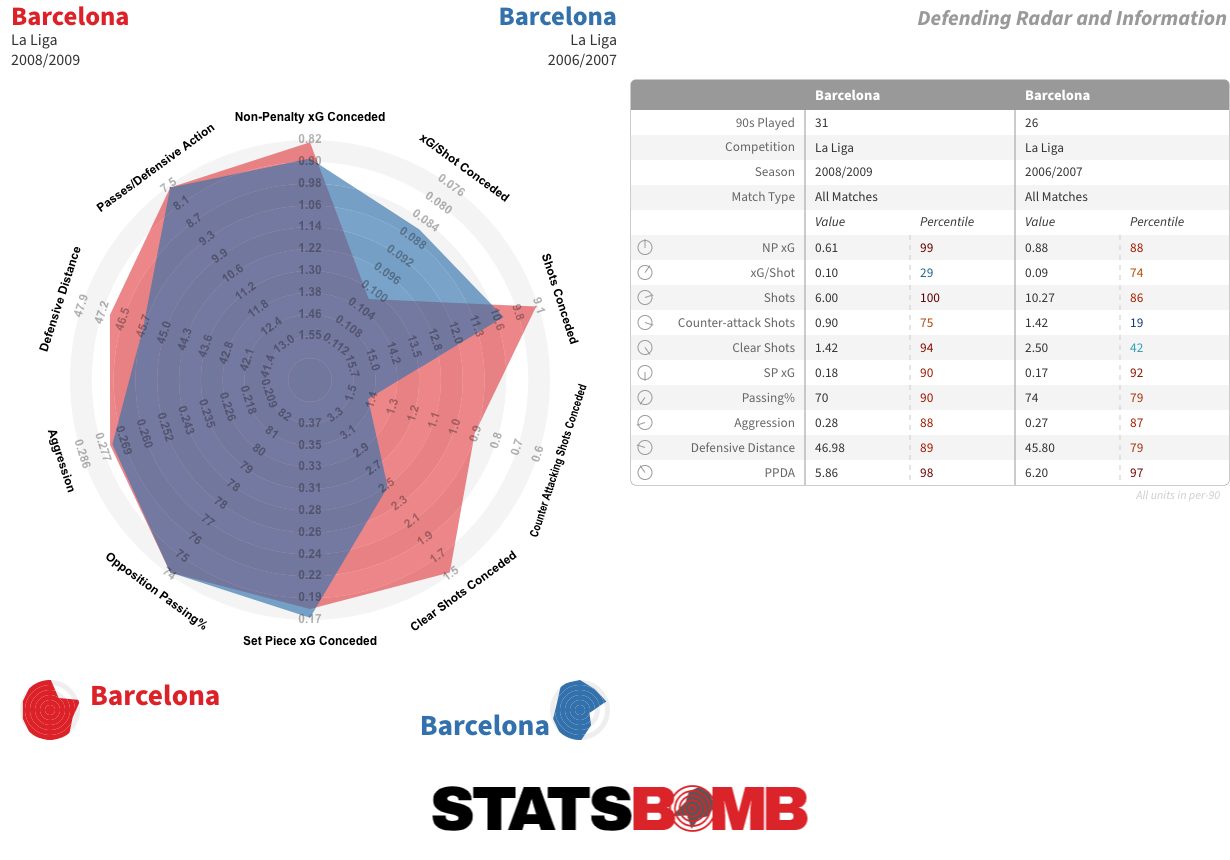

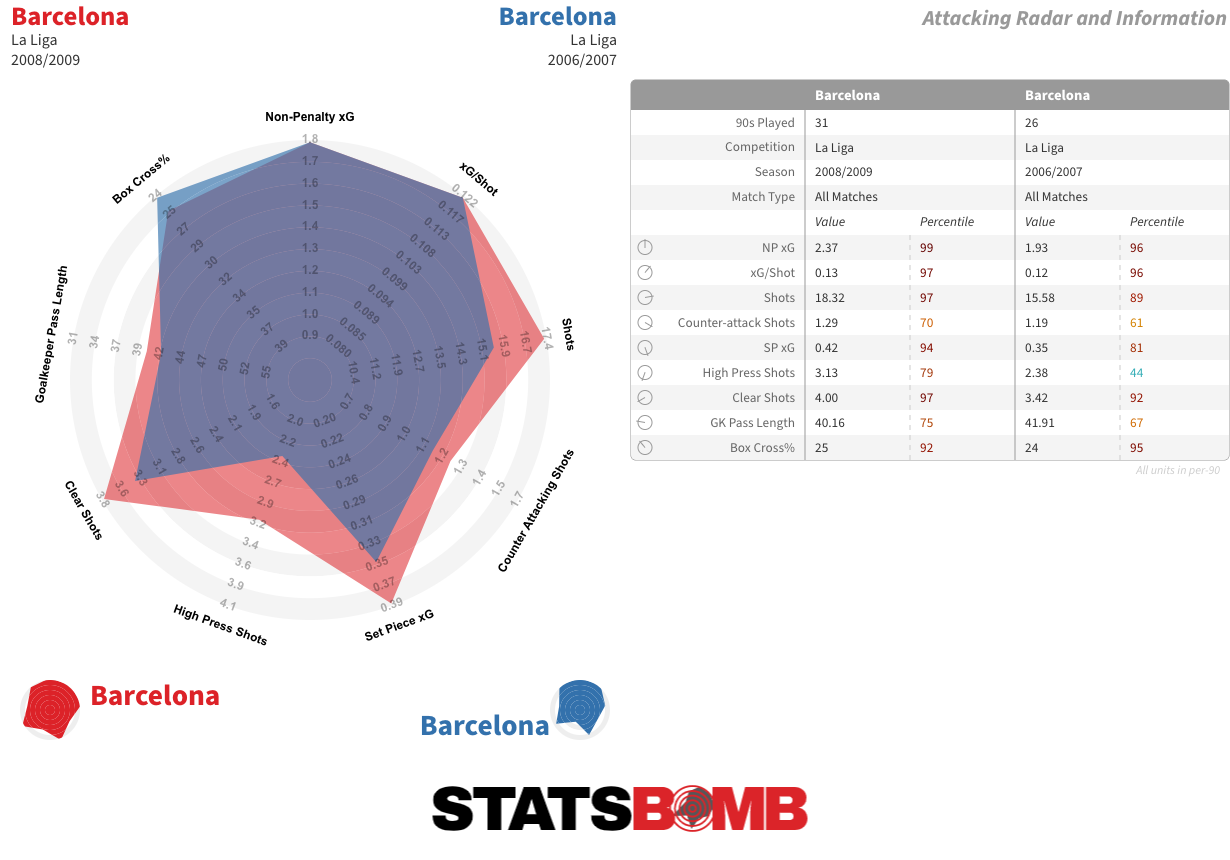

ND: Before we talk about how Messi functioned in that role, let’s first talk about the differences between the Barcelona of Frank Rijkaard that we analysed in part one of this series and this version, with Guardiola as head coach. The data tells us that this 2008-09 Barcelona side defended higher up and slightly more proactively than the 2006-07 team. Incredibly, they only gave up an average of six shots per match, four less than the 2006-07 team and less than any other Barcelona side in our database.

In attack, they took over three more shots per match than the Rijkaard team and did so from better average positions.

This Barça, who won the treble of La Liga, the Copa del Rey and the Champions League, has the best expected goal difference (xGD) of any Barcelona team in our database. Another treble-winning outfit, the 2014-15 side, stands second by that measure. Can you add anything else from a tactical standpoint?

AD: For me, they are a historic team. Of all the teams I’ve seen, they are the one who did most things well. It is true that football is for the footballers, and in this team there was such an accumulation of talent that they were nearly unstoppable. But there were also a lot of tactical details, many of them revolutionary. Guardiola implemented new ideas and perfected pre-existing ones. Perhaps the most valuable thing about this team is that they demonstrated that in football everything is related. That attacking and defending go hand in hand, and that if you attack well in an organised fashion it requires less effort to defend effectively thereafter. This Barcelona side perfectly applied the principles of positional play (juego de posición). They were a team who occupied space in a very rational manner and that made it easier for them to construct attacks.

ND: We are going a little bit off course here but could you explain, in simple terms, what positional play is and how it functions?

AD: In reality, we’d need a whole article to explain it properly! To put it in basic terms: in positional play, the positioning of every player has an effect on the team’s collective play. All of the players know exactly where they should position themselves, and they respect that positioning for the good of the team. For example, the wide forwards have to stay out wide even if they don’t receive the ball because their mere presence there widens the scope of the attack and pins down an opponent.

ND: That last point is something we clearly see in this match.

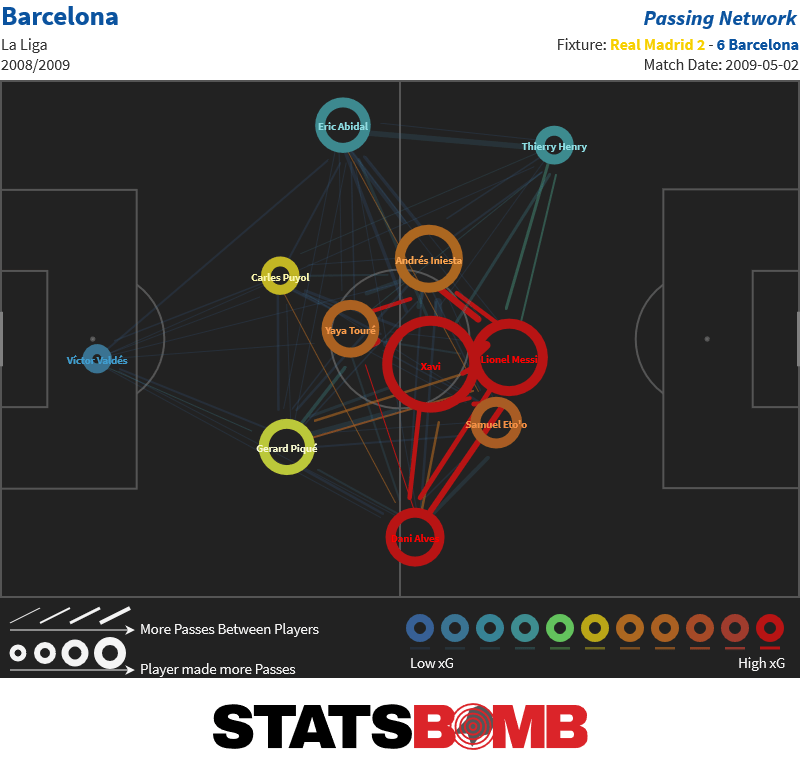

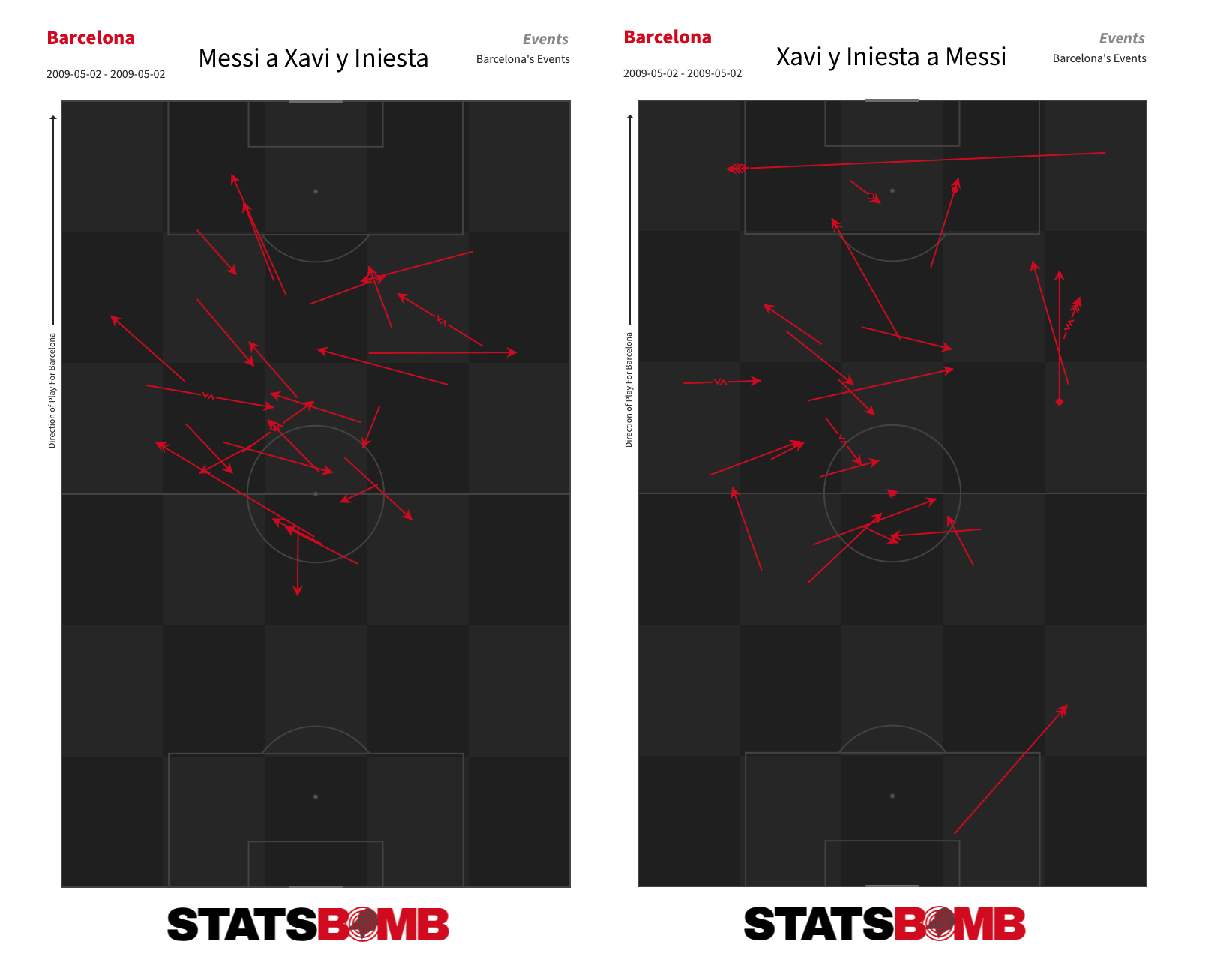

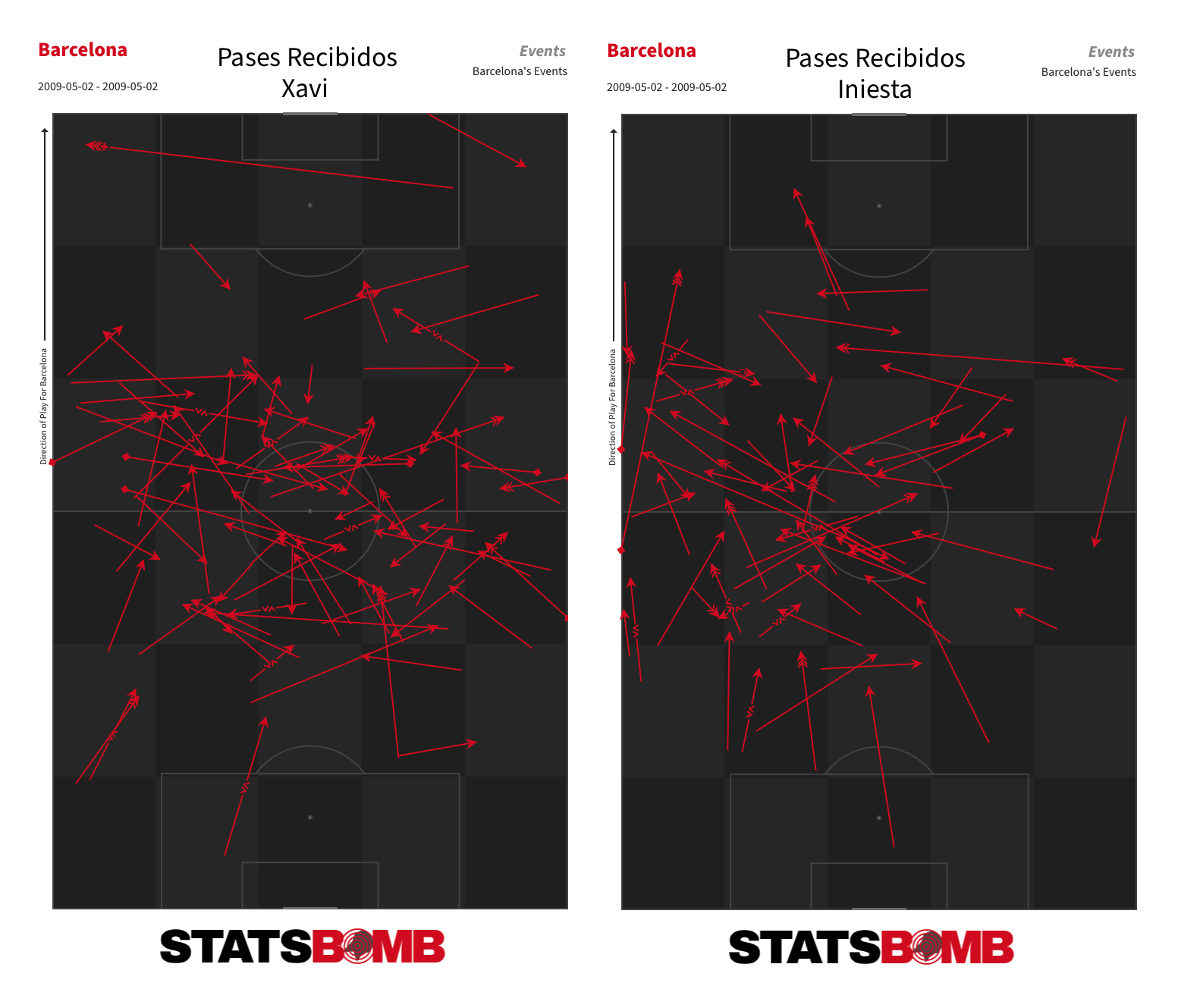

AD: Yes. Guardiola’s game plan was based around it, in fact. He positioned Messi as a false nine so that he could drop off to receive between the lines, and then instructed the two wide forwards, Thierry Henry and Samuel Eto’o, to consistently make runs in behind from the flanks. The pass map for this match shows just that. We can see that Messi is very close to Xavi and Iniesta in the centre, while Henry holds a very high and wide position on the left.

That created a problem for the Madrid defence, who couldn’t work out how to position themselves to defend Barcelona’s attacks. This map of passes from Messi to Henry and Eto’o shows this game plan in action. He played 12 passes to the pair of them: six of those were into space, four went diagonally forward and only one went backwards.

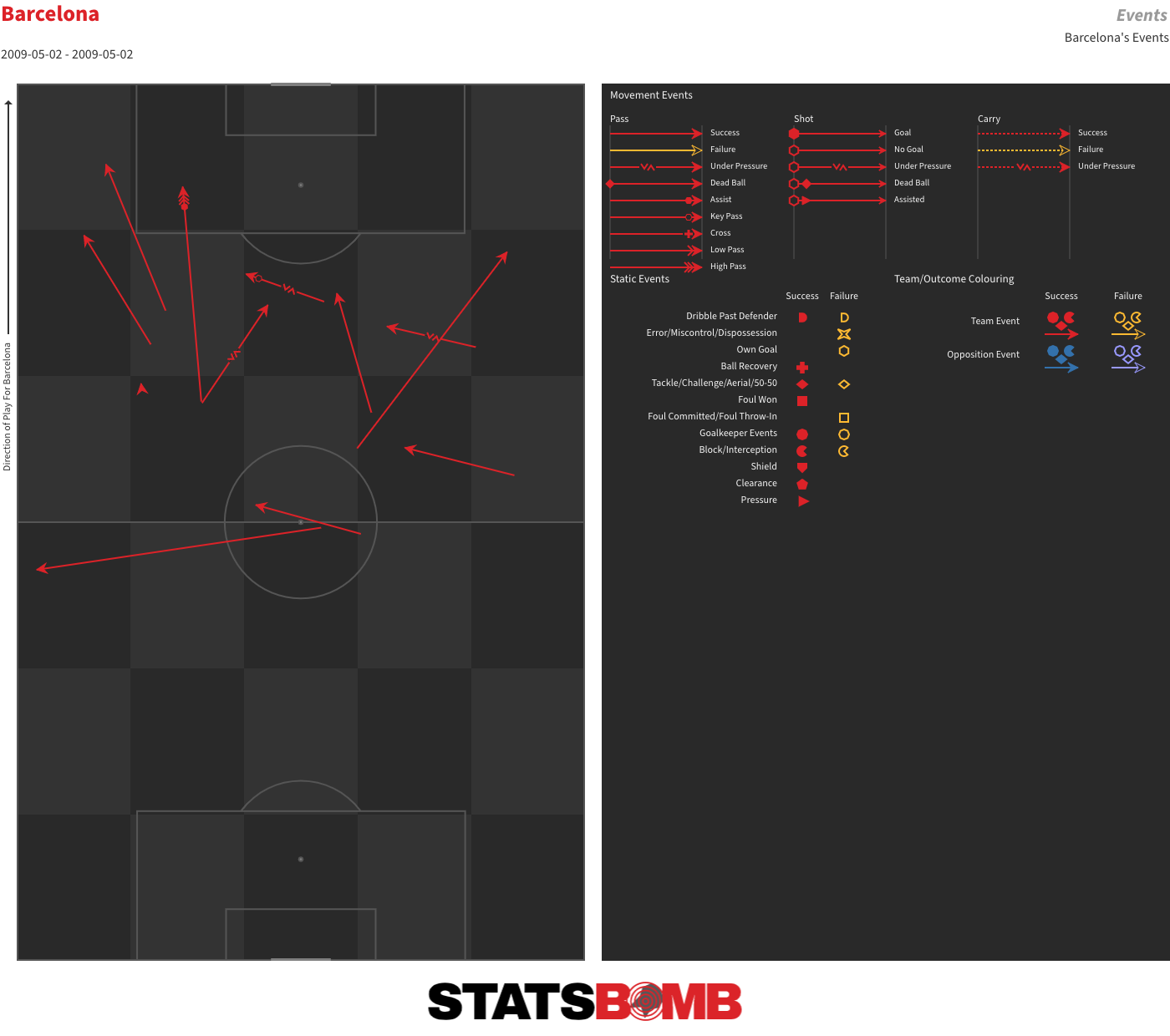

ND: Messi started the match in his normal position at that time as a wide forward on the right. But seven minutes in...

...he switched positions with Eto’o to move into the centre. A couple of minutes later, we see the first incisive move with Messi participating in central areas. Shortly thereafter, he provides the assist for the first Barcelona goal with a nice clipped pass to Henry. In addition to his connection with the two wide forwards, it is the relationship between between Messi and Xavi and Iniesta that allows this system to function at such a high level. When the three of them combined, and they did so often, Madrid just couldn’t get the ball off them. Many of Barcelona’s most dangerous attacks arose from combination play between them.

It seemed to me that there was a little bit of naivety in the way Madrid approached this match. This season, only three teams defended higher up against Barça than Madrid did in this match (José Luis Mendilibar’s Valladolid did so both home and away) and all of them attempted to break up Barça’s passing chains more frequently than Madrid did. There was insufficient pressure on the ball in midfield and a lot of space in behind their defence. With that said, what could any opposing team do when Barça positioned Xavi, Iniesta and Messi in close quarters? If you sat off them, you gave Xavi and Iniesta time and space to pick out incisive passes to the wide forwards or the full-backs; if you engaged them, they would just work the ball around to advance dangerously through the centre.

AD: That is why it was so difficult to deal with them. The best way to do so would be to prevent the ball getting to them. There are two ways of doing that. The first is to press very well high up the pitch and stop the team from moving the ball through the centre. Force them to go long. The other is to have numerical superiority in the centre of the pitch so that there is always pressure on the ball and you still have help on hand. Obviously, if any of those players receive the ball with time and space to pick their pass... Maybe the best approach is to drop back and defend your area. But even then, talent like that normally finds a way of creating chances.

ND: It is also worth mentioning the varied movements of Xavi and Iniesta. Sometimes it is Xavi who positions himself between the lines and Iniesta who drops back to receive in deeper areas. Normally, it is Xavi on the right and Iniesta on the left, but sometimes they switch.

Was this variety of movement a regular thing in Guardiola’s Barcelona?

AD: It was a regular thing because one of the basic objectives of Guardiola’s Barcelona was to constantly create passing lanes. And passing lanes are created with constant movement. Saying that, while it is true that you can find moments in which one of them is ahead of the other, the general rule was that Xavi was the one who dropped back to receive the ball, while Iniesta positioned himself higher up. Xavi was better at initiating and creating play. Although Iniesta also had the ability to create without losing the ball, one of his best qualities was his ability to break lines off the dribble, something that was more decisive in the attacking zone.

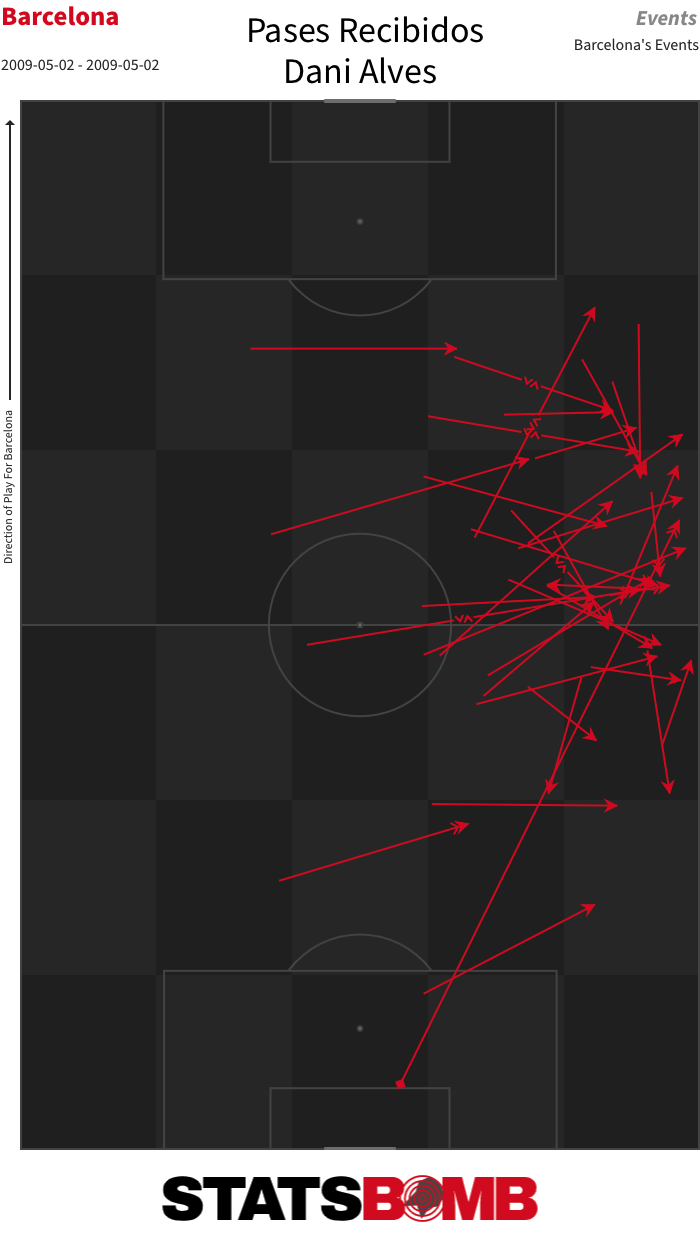

ND: Do you want to talk about the role of Dani Alves in this match? At this time, we were used to seeing him flying forward down the right to provide width as Messi moved infield. He appears in a relatively high and wide position in the majority of Barcelona’s pass maps for this season. But he has a more varied role in this match.

AD: Yes. Alves interpreted very well when and where to appear. He moved wide to spread the pitch when necessary but he also tucked in at times to provide a passing lane.

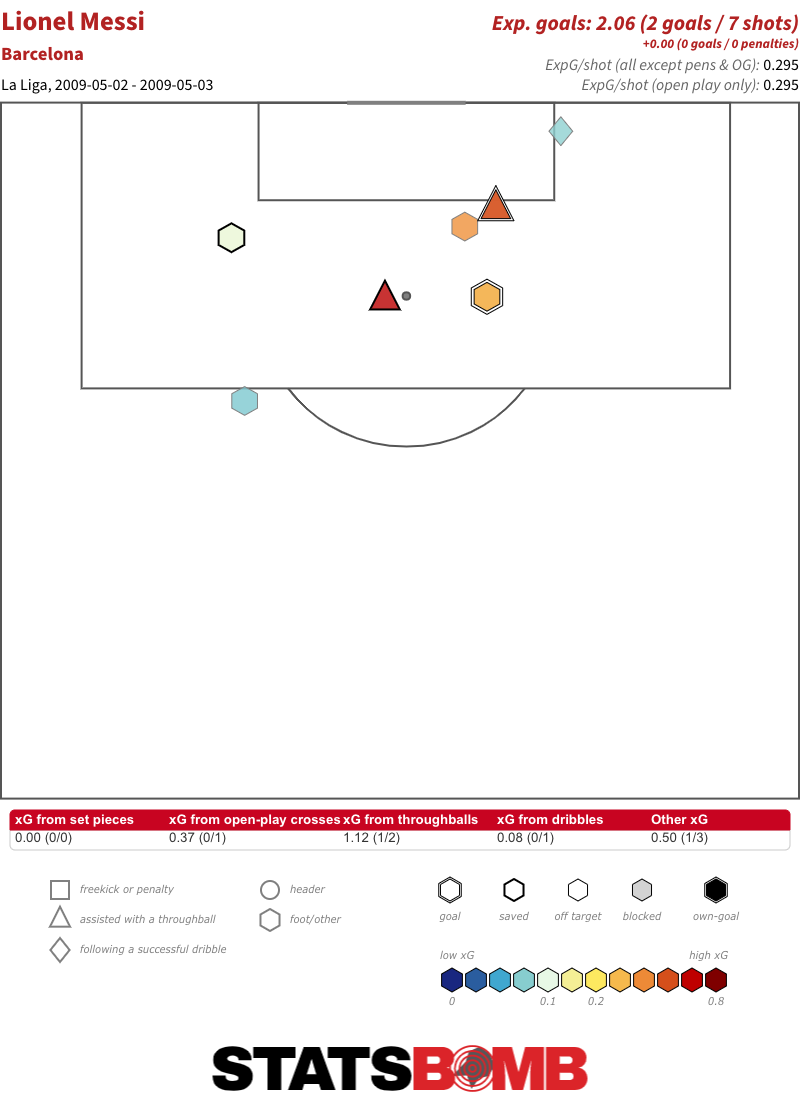

ND: Messi dominated this match. Two goals and an assist. Seven shots and three key passes, with the majority of those shots coming from central positions inside the area.

In that sense, this match functioned as a preview of the exceptional goalscorer that Messi would become in the years that followed. After 20 non-penalty goals this season, he scored 33 in 2009-10, 27 in 2010-11 and then 40 in 2011-12.

Even before this match, Messi was starting to appear in central areas with greater frequency than in the previous campaigns.

This was the first season in his career in which he averaged over a goal or assist per 90 minutes. Was a move to a more central starting position the next natural step in his development?

AD: Without a doubt. His development as a footballer was gradually pushing him towards a central position. He was becoming increasingly important to the team and showing his true self. In youth football, he was used to playing as an attacking midfielder with freedom of movement, so this was the natural evolution of that. Even still, this day changed his footballing life. Before this match, he had always had a positional responsibility related to his position on the right flank. From this day on, all of the team’s movements were centred around him. He was given total freedom. That resulted in a very evident increase in his influence over matches.

ND: During this period of Messi’s career, with Guardiola as his coach, there seemed to be a perfect balance between his almost limitless ability and the collective functioning of the team. The best player in the world playing in the world’s best team at the time. There was a synergy there that didn’t exist previously, and as we will see in the third and final part of this series, that doesn’t exist in the present day.

AD: I think this match is one that should form part of football history. I think that with time people will attach even more importance to it. It marks the point when the best footballer in the world was sublimated into a team who had completely sublimated the concepts of positional play. This match acts as a perfect manual in terms of how to form a game plan and carry it out in function of the response of your opponent. The focus is on two opposing concepts: combination play between the lines with the numerical superiority provided by Messi, and the threat in behind provided by the wide forwards. Barcelona chose one or the other in accordance with the actions of Madrid’s players. More often than not, the most productive one.

Frenkie de Jong, Barcelona's star midfielder (still) in waiting

We have reached the point in Barcelona's current crisis where everything and everyone involved in the club is being questioned. Blame is in unlimited supply and nobody is safe. The squad has lost faith in Setién according to one report. Eder Sarabia, Setién's assistant manager, is a loose cannon and needs to tone it down says another. Ter Stegen might want to leave according to a different report and Jordi Alba was forced to cover his ears against Real Sociedad to drown out the whistling fans. There are also discontented murmurs about Frenkie de Jong and his role in the team.

On a scale of 1 to 10 with 10 being Barcelona’s president being accused of hiring social media accounts used to disparage players, de Jong being played out of position is a two. But it’s important because de Jong was seen as a (almost) zero-risk signing.

De Jong was seen as a safe bet; the golden boy. He had charmed Barcelona fans with his beaming smile, golden hair, his assuredness both on and off the field and with a limitless future ahead of him. The 22-year-old doesn't say anything wrong because he hardly speaks. The only time he lifts his head is to seek a pass.

He was built in the home of Johan Cruyff and while it's not Barcelona DNA, it's a similar enough strand – a distant relative who you still look eerily similar to. Take the ball, pass the ball. It's what de Jong does best as we saw during Ajax's impossible run to the Champions League semi-final last year. We see it every time he pulls on the Oranje of Netherlands too when he seems to grow an inch in stature. That’s not how it is at Barcelona though as he seems to shrink into his role at the Camp Nou.

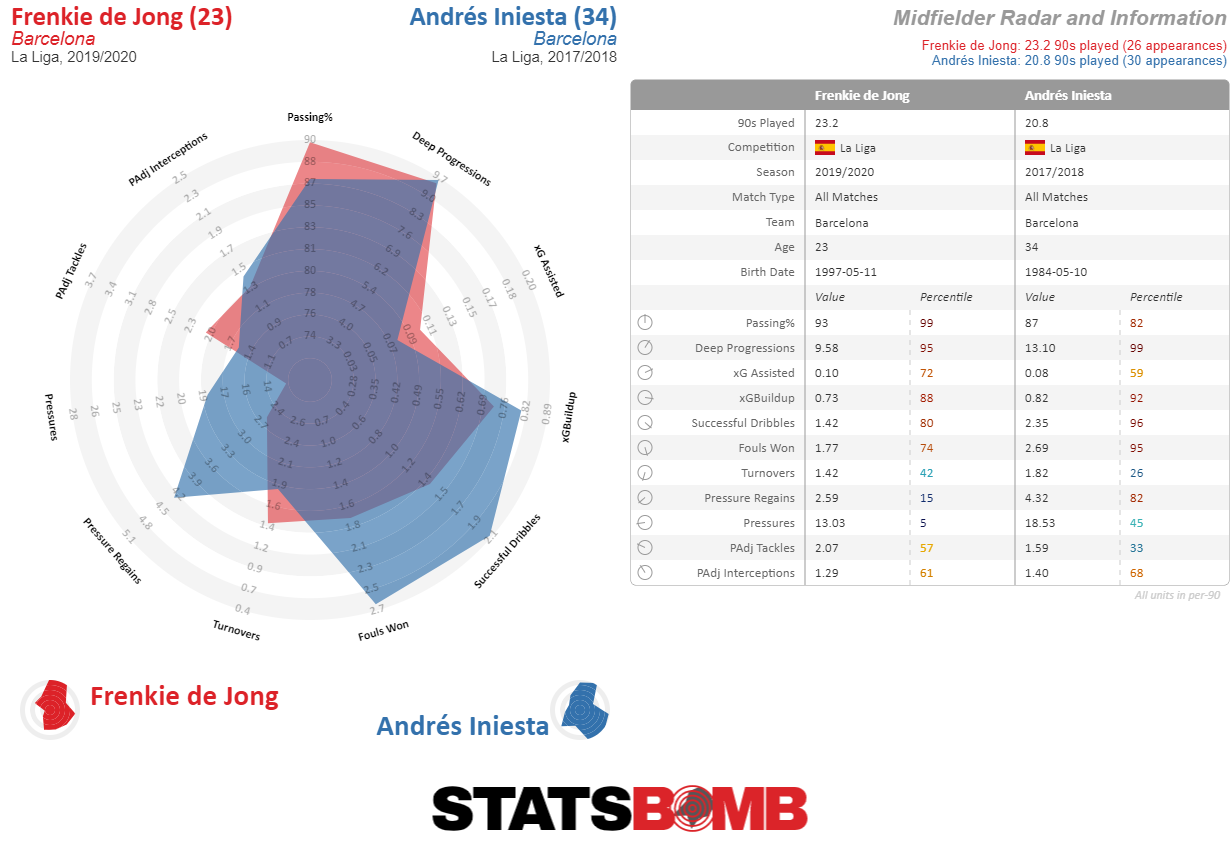

The risk was none and the expectations were high. That's possibly why the discontent has crept in because while he has performed well, he is still being played out of position. Barcelona have been searching for an Andres Iniesta replacement since he left for Japan. Andre Gomes was seen as a potential heir to the crease Iniesta had worn in the left of a midfield three at the Camp Nou but that turned out horribly for everyone before he left for Everton. Philippe Coutinho was drafted in as a more expensive and attacking solution but that went the same way.

Antoine Griezmann was touted as a player who might be able to play in the role too but has he played further forward and is entirely different to Iniesta anyway. Frenkie de Jong is being shoe-horned into the same role and has suffered in his first season because of that.

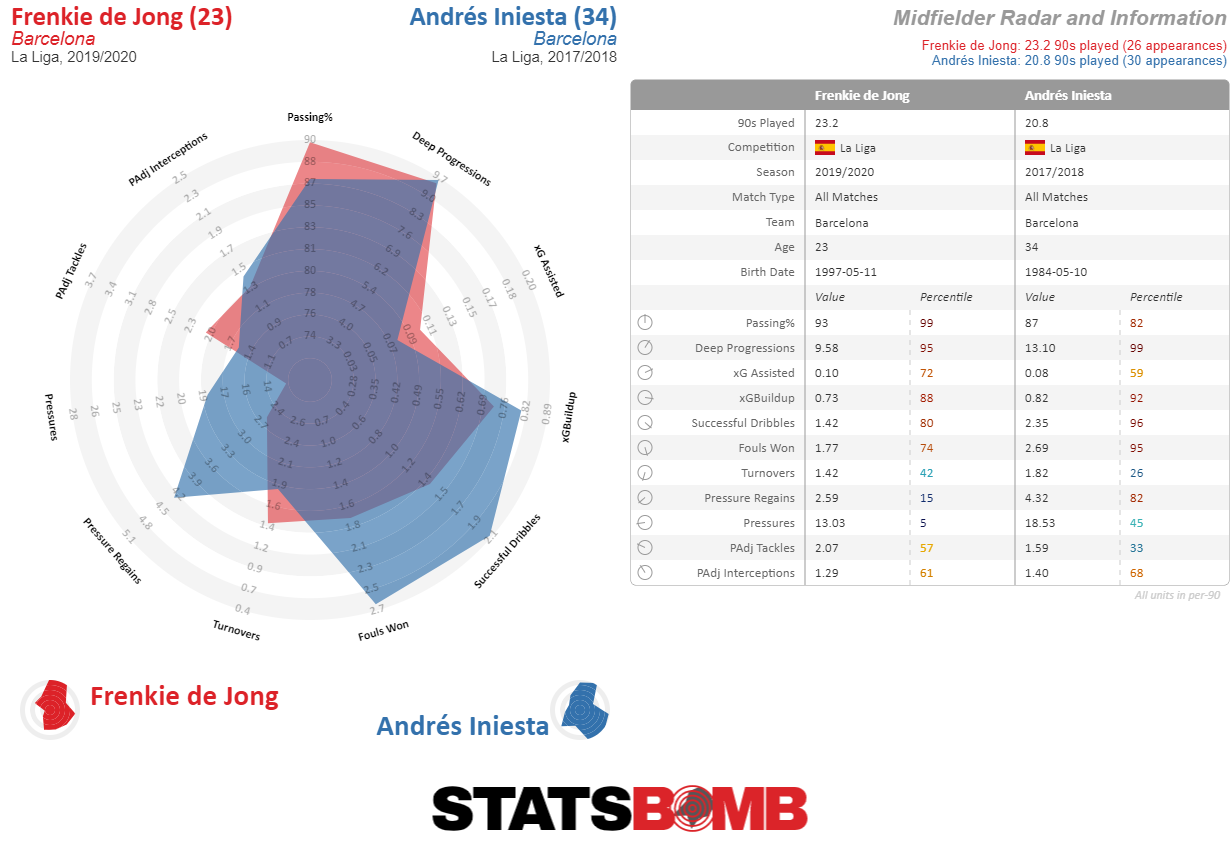

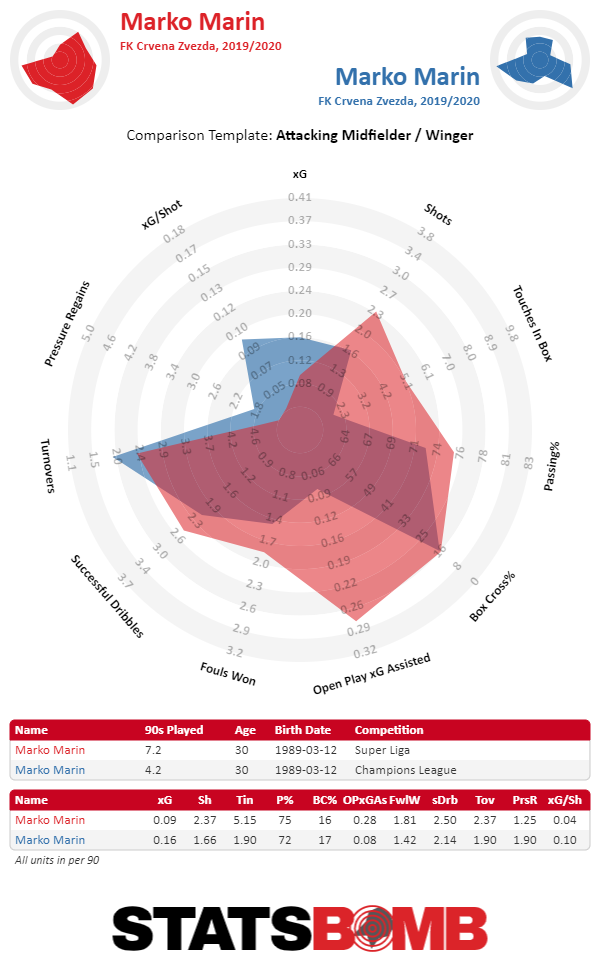

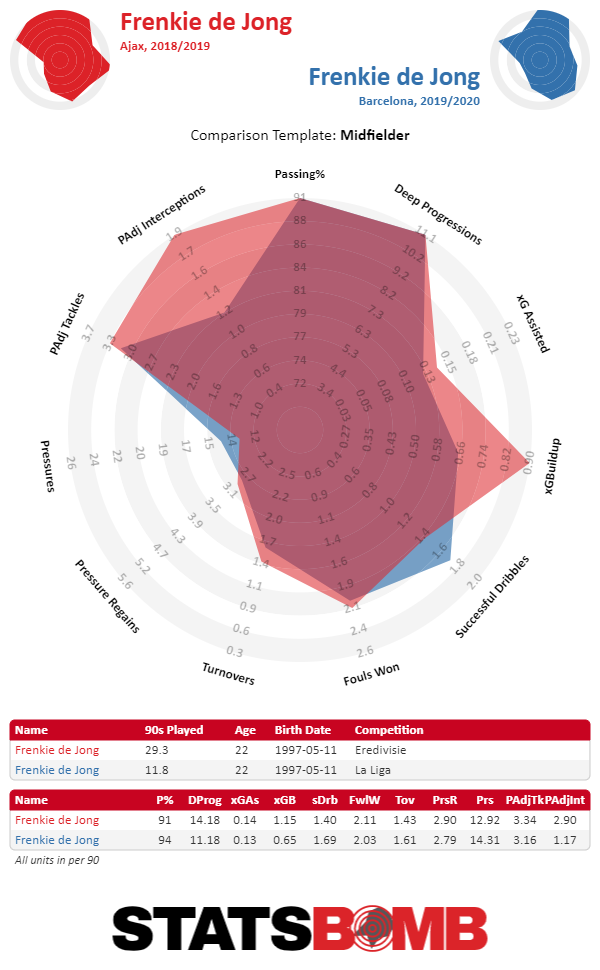

A look at Iniesta and de Jong comparisons show that the magician from Albacete was a far more accomplished attacker. Iniesta didn’t run but glide. He didn’t pass to team-mates, he caressed the ball into their path. He didn’t dribble, he skipped by defenders. Comparing de Jong's first season at Barcelona to Iniesta's last we can see that the young Dutchman is doing a reasonable, if clearly lesser imitation.

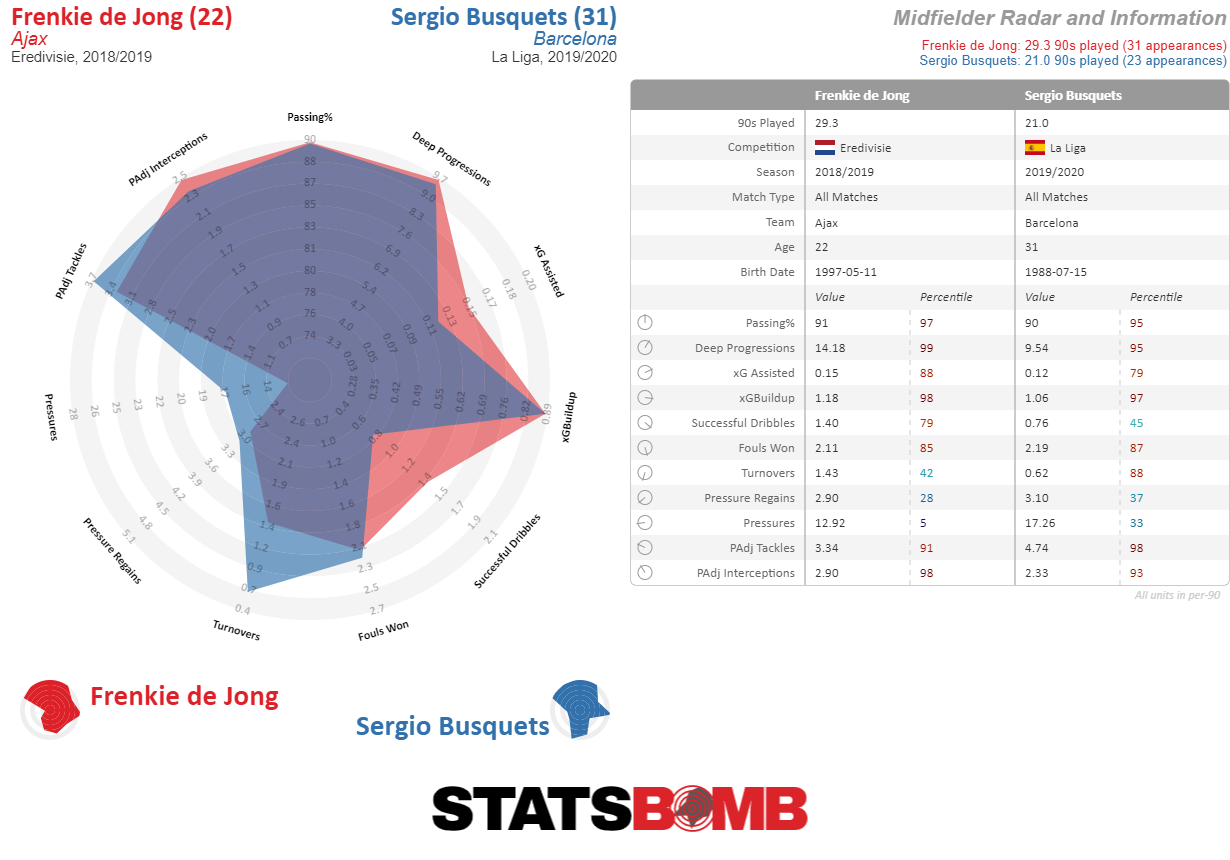

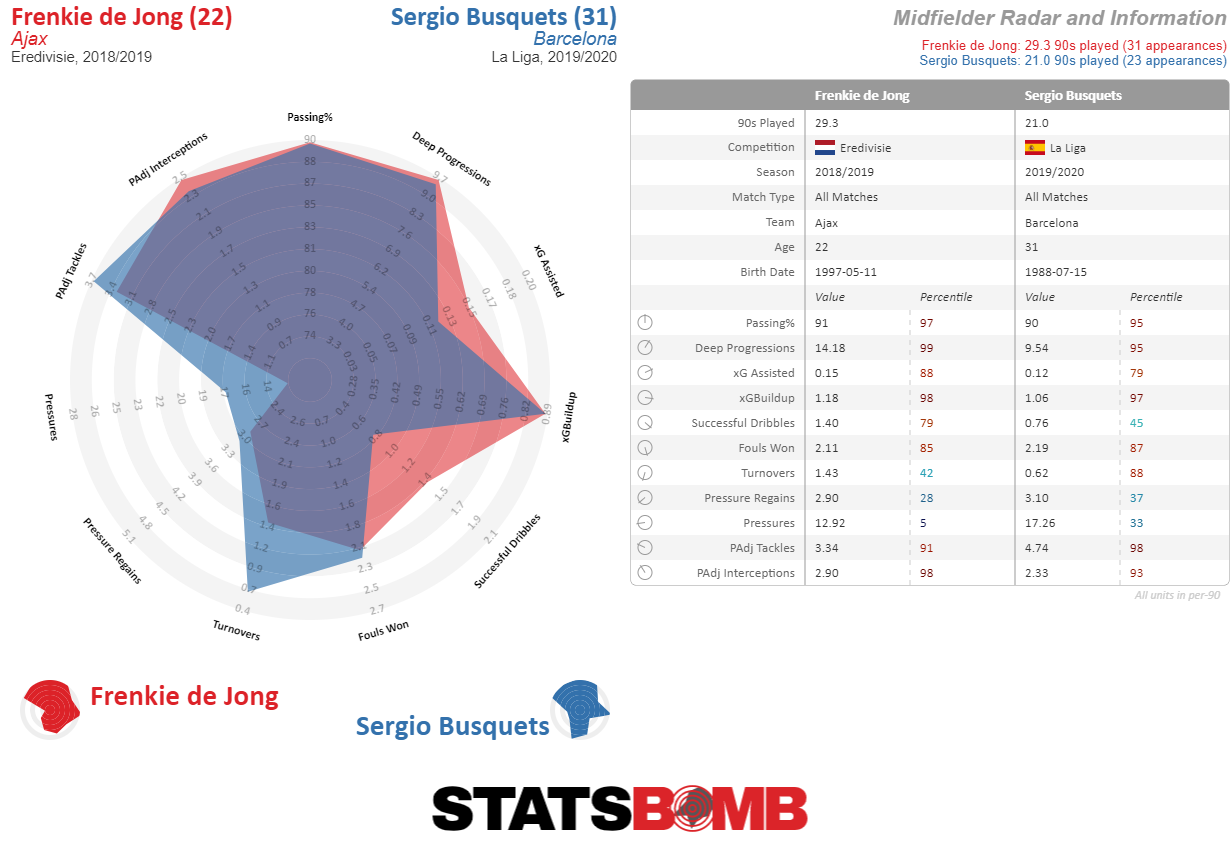

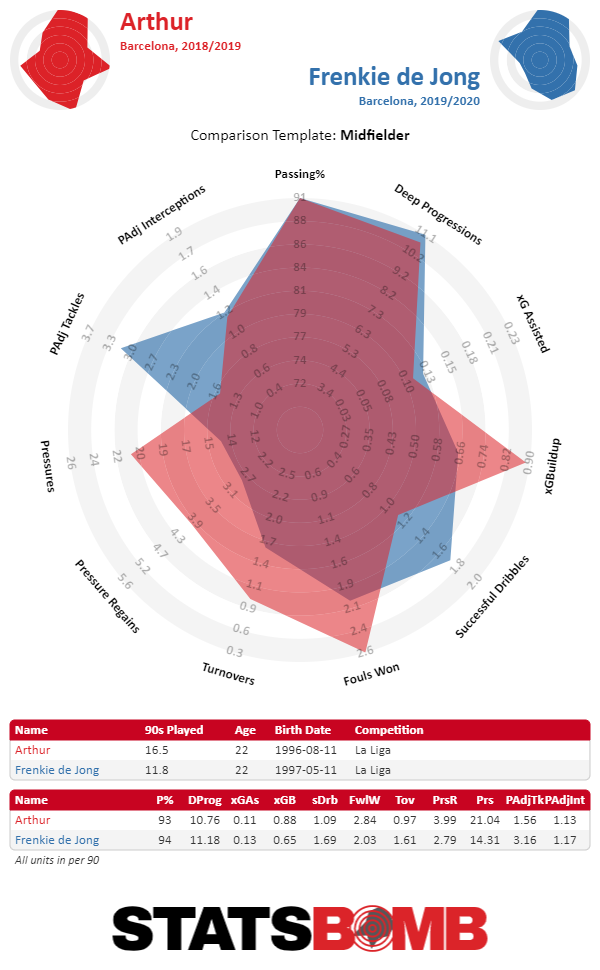

De Jong’s last year at Ajax was more similar to Sergio Busquets, which is where the problem arises. Here's his last season at Ajax and the current season for Barcelona's stalwart midfielder.

"The positive thing is that he plays a lot of games, but he's playing in a different position to what he's used to. He plays differently with me in the national team,” said Ronald Koeman as a man in a good position to know. Koeman is the coach of the Netherlands, gave de Jong his debut for his country and played for both Ajax and Barcelona during a glittering career. In every game under Koeman, he has played de Jong as the deepest midfielder in a double pivot. He is mostly positioned beside the more destructive Martin de Roon as a nice complement.

What is De Jong’s best position?

When De Jong was signed for Barcelona, Cruyff ultras rejoiced. He was set to be the pièce de résistance in Barcelona’s midfield for years to come. He was going to bring back the silky smooth passing of a bygone era and Barça could slowly ease Sergio Busquets out of the team knowing they had someone to replace him.

But that vision has not become reality.

He has played in left central midfielder and right central midfield more than he has played as a central defensive midfielder, his best position, and was even deployed as a left midfielder in a 4-4-2 against Real Madrid recently, looking suitably uncomfortable. Under Setién, De Jong is playing in left midfield in a 4-3-3. He is further ahead of Busquets with a carrousel of players coming and going in the right midfield position.

The belief seems to be that De Jong, who is so good as a progressive passer, will be more dangerous in a more attacking role – a counter-intuitive belief. He has been turned into a runner, a dribbler, a connector of midfield and attack when his best position is sitting deep, breaking up playing, starting attacks and receiving the ball from his goalkeeper and defenders. The term ‘salida de balón’ – bringing the ball out from the back, essentially – has saturated Setién’s tactics talk since he took over.

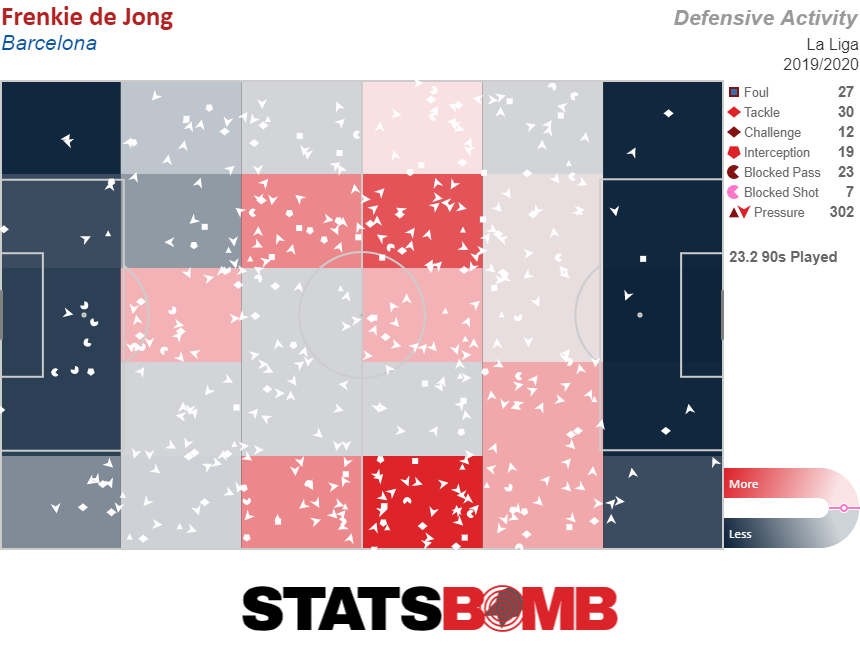

The concept is so important to him that there are times when it seems it is all he talks about. But he doesn’t have the best young player in the world at receiving the ball where he needs to be. And by having De Jong in a more attacking position and shunted to the left of midfield, he is also missing out on his best qualities as a defender.

De Jong’s Defensive input

"Of course he was the man of the match, it was well deserved," Koeman said after his performance against England in the Nations League final. "Most of the people are always looking at what he does with the ball, how calm he is, but look how well he defend and how many balls he is winning in midfield -- it's fantastic to see Frenkie play like this.”

Koeman, never shy with his opinion as is the Dutch modus operandi, was making an important point and something that has been lost since on his way to Barcelona. It’s something Barcelona are missing as Gerard Piqué and Clement Lenglet are often left fighting fires when teams attack them on the counter.

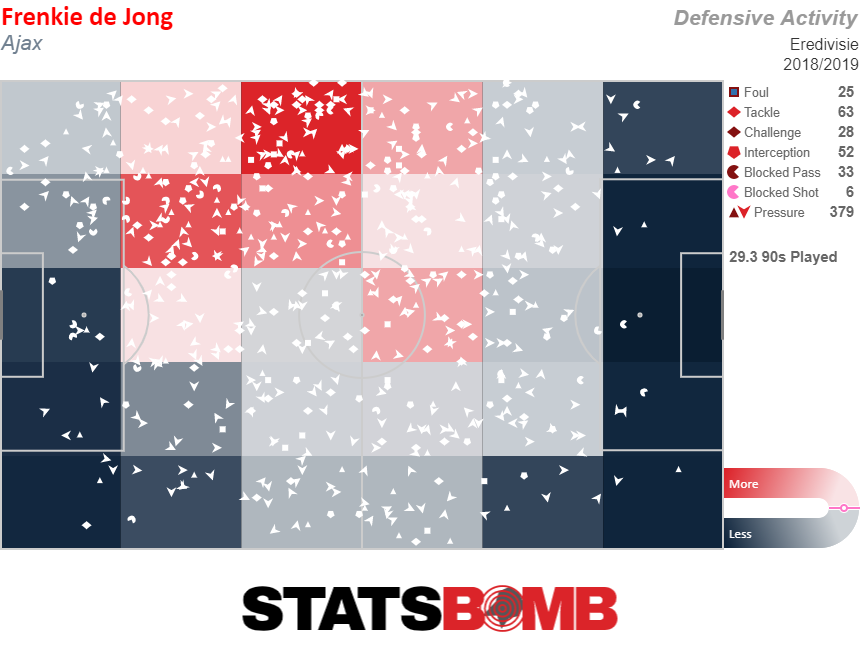

Two very interesting statistics when it comes to this is De Jong’s output for Barcelona compared to last year with Ajax. He had 63 tackles and 52 interceptions last season. He has obviously played six games less so far this season but unless he goes on a rampage in the next few games in LaLiga, he won’t catch up. He has just 19 interceptions this season with Barcelona and 30 tackles in 24 games. Adjusting for possession, and looking at the numbers on a per 90 basis, de Jong has gone from 3.34 possession adjust tackles per 90 and 2.90 possession adjusted interceptions to 2.07 and 1.09 at Barcelona respectively. That's a massive drop.

De Jong has come into a team that does a lot less pressing than what he was used to. His positioning when teams were forced to play rushed passes was impeccable as we can see with the numbers mentioned beforehand. Despite starting as the deepest midfielder, de Jong frequently stepped up the pitch at Ajax to break up play.

Now though, as we saw against Real Sociedad, he is being forced not to win the ball in transition but to try and win it against a team given time to build. De Jong is often left watching the ball pass him by as he chases opponents, while his ranginess goes to waste and he's left to patrol only the narrow areas in the channels where he's assigned.

In summary, De Jong is playing well in a position he is not comfortable in. He is further forward than he is used to and doesn’t have the chance to affect the game defensively. He is still doing all the good things he did at Ajax, and has the second-most deep progressions in the team after Messi. It’s the same thing he does so well with the Netherlands but like Koeman says, he is not as involved in the defensive side of things.

Aside from the fact that his interceptions and tackles are way down, it’s his overall involvement and how he feels in the team that is affected. We saw at the Bernabeu two weekends ago when he was running around chasing Fede Valverde and Dani Carvajal, which he did diligently, that he looked lost. The Dutchman found himself on the edge of the box ahead of the ball too many times when he is best arriving late and causing damage in his own time.

Busquets is not droppable yet because his performances haven’t merited it but it’s only a matter of time before the clamour to have De Jong deployed in his best position becomes too loud. As Barcelona trudge through this season, De Jong is a small concern but they might alleviate a lot of the symptoms of their current crisis on the field by giving him a more central role than the peripheral one he is currently occupying.

No Pulisic, no problem: checking in on the Bundesliga’s American talent

With the departure of Christian Pulisic to Chelsea, it's likely many think the American presence in the Bundesliga has waned. While the Hershey, Pennsylvania native’s move to Chelsea probably caused a headache or two in US TV executive rooms, in terms of depth, the American contingent has never been stronger. In the last few seasons, the infusion of another batch of young American talent ( including the likes of Weston McKennie, Josh Sargent and Tyler Adams) there are now a record-setting 13 Yanks in Germany, 8 of whom have completed at least ten games. With apologies to the rejuvenated Timmy Chandler and other usual suspects such as John Brooks and Alfredo Morales, here we're taking a look at four young Americans you may not have heard much about who are getting their feet wet in Germany’s top division.

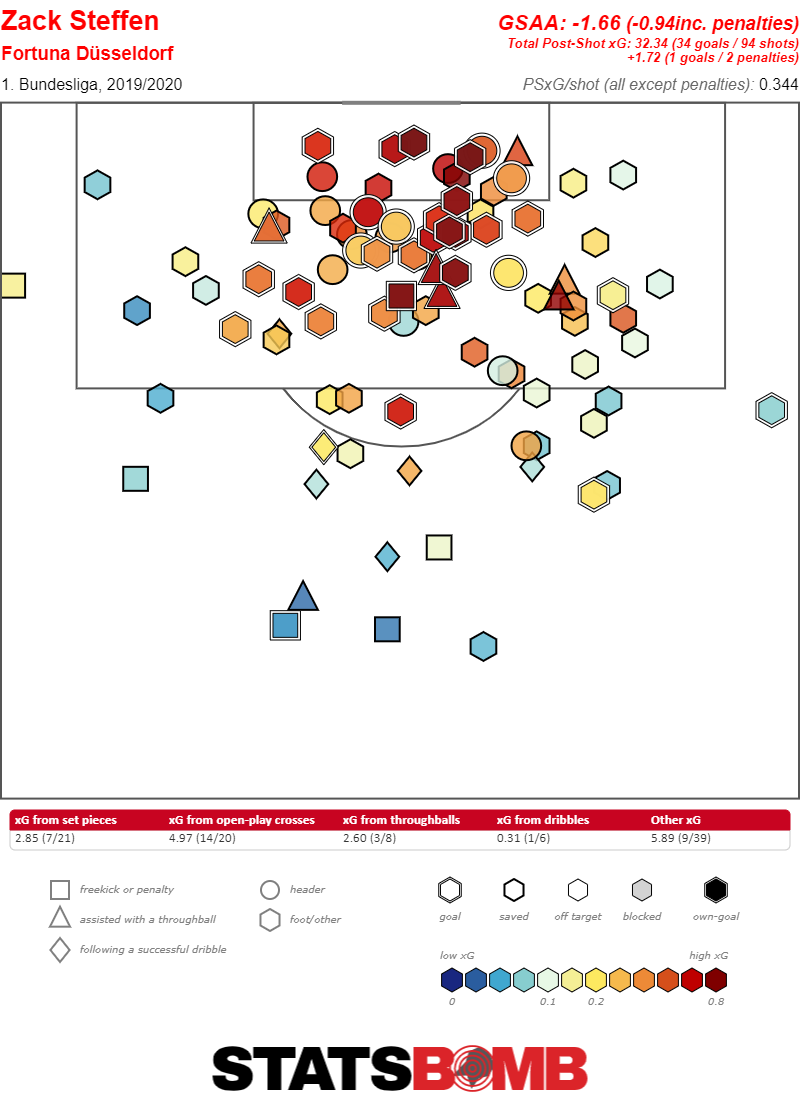

Zack Steffen

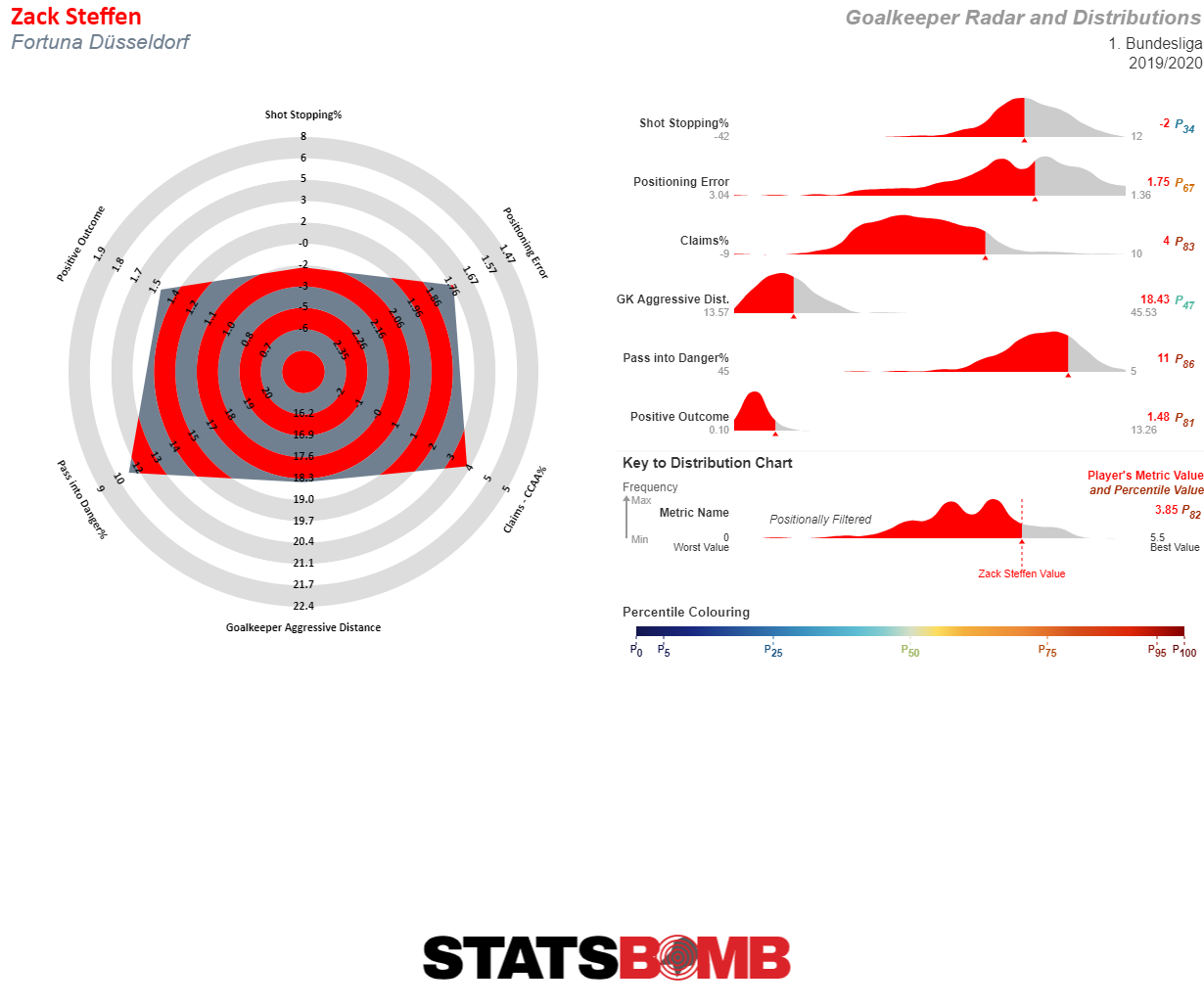

Zack Steffen, who despite missing the last three matches with a knee injury, has been a roaring success between the sticks. The 24-year-old’s Fortuna Düsseldorf season began with ten saves on his debut in a stunning win against Werder Bremen, one of the highlights of a dismal campaign. The Manchester City loanee was among the top three keepers early on in the season. Steffen regularly faced 5–6 shots on target per match and had multiple nine-save matches in the first six rounds, but like his team, his goals saved above average began to drop; it is now -1.66. That figure is in large part a byproduct of a team with a -17.6 expected goal difference, by far the worse in the Bundesliga. So while Steffen might seem to be performing slightly worse than an average keeper, he's doing it in a context where the ten players in front of him are all significantly worse than that. Looking at his map, you can see the barrage of close-range, high xG value goals conceded. The post-shot xG of the shots on target he's faced is 0.36, tied for 2nd behind poor Roman Bürki. Video review also shows a couple strange low-quality chances scored against Steffen, which drags down his shot-stopping numbers (flukes happen, but you don't get to only count the good stuff in the averages).  His distribution fills a huge need for Fortuna, who struggled mightily with Michael Rensing (also -8.4 under his xG against) on “launches”, passes over 40 yards, at just 40%. Because Fortuna, having lost Dodi Lukebakio and Benito Raman, are now a worse version of their deep-sitting, counter-attacking side, upgrading to the 47.7% of Steffen's launches is pretty valuable. That percentage is 6th in the league, close to a host of others just below 50%, with Manuel Neuer’s otherworldly 64.4% leading the pack.

His distribution fills a huge need for Fortuna, who struggled mightily with Michael Rensing (also -8.4 under his xG against) on “launches”, passes over 40 yards, at just 40%. Because Fortuna, having lost Dodi Lukebakio and Benito Raman, are now a worse version of their deep-sitting, counter-attacking side, upgrading to the 47.7% of Steffen's launches is pretty valuable. That percentage is 6th in the league, close to a host of others just below 50%, with Manuel Neuer’s otherworldly 64.4% leading the pack.  His other metrics, including claims and positional errors, are solid, while his comfort on the ball and willingness to pass into dangerous zones, makes his ceiling quite high. Overall, after a failed stint at Freiburg’s U23 a few years ago and a few USL minutes, it’s fun to see Steffen reaching his potential. We have to agree with sporting director Lutz Pfannenstiel — a man who played in goal on six continents should know, after all — that Steffen can be a top keeper at the European level.

His other metrics, including claims and positional errors, are solid, while his comfort on the ball and willingness to pass into dangerous zones, makes his ceiling quite high. Overall, after a failed stint at Freiburg’s U23 a few years ago and a few USL minutes, it’s fun to see Steffen reaching his potential. We have to agree with sporting director Lutz Pfannenstiel — a man who played in goal on six continents should know, after all — that Steffen can be a top keeper at the European level.

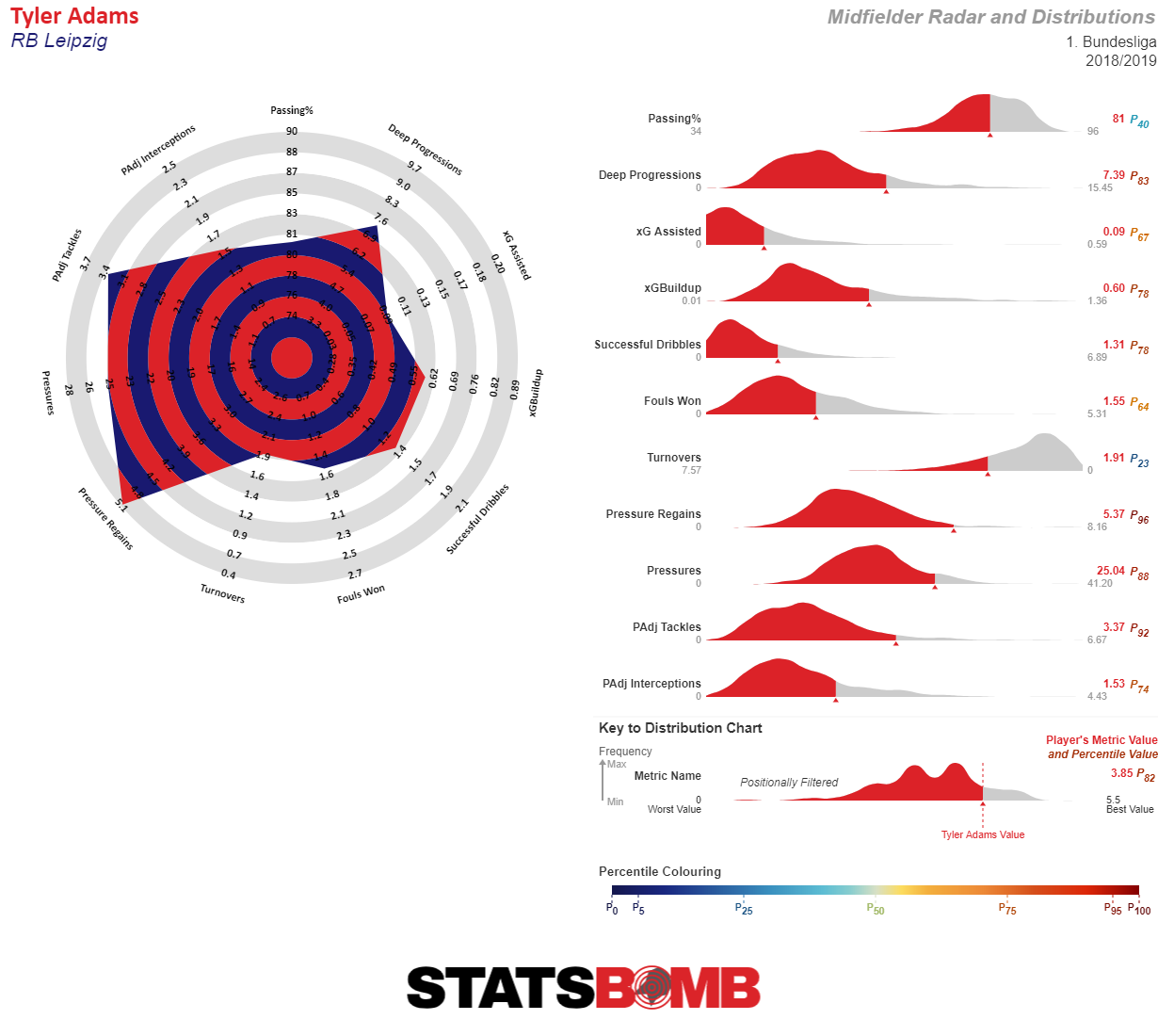

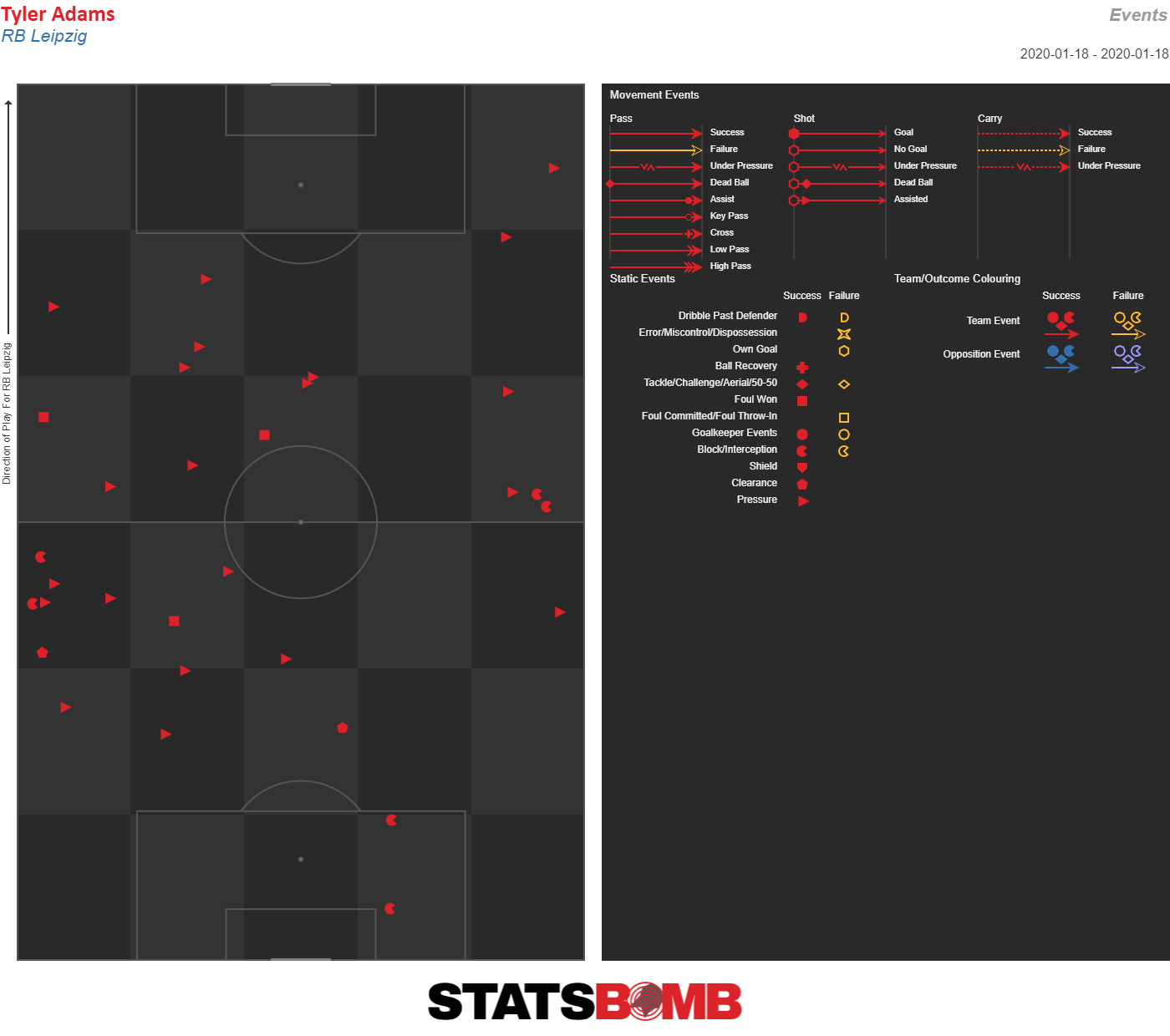

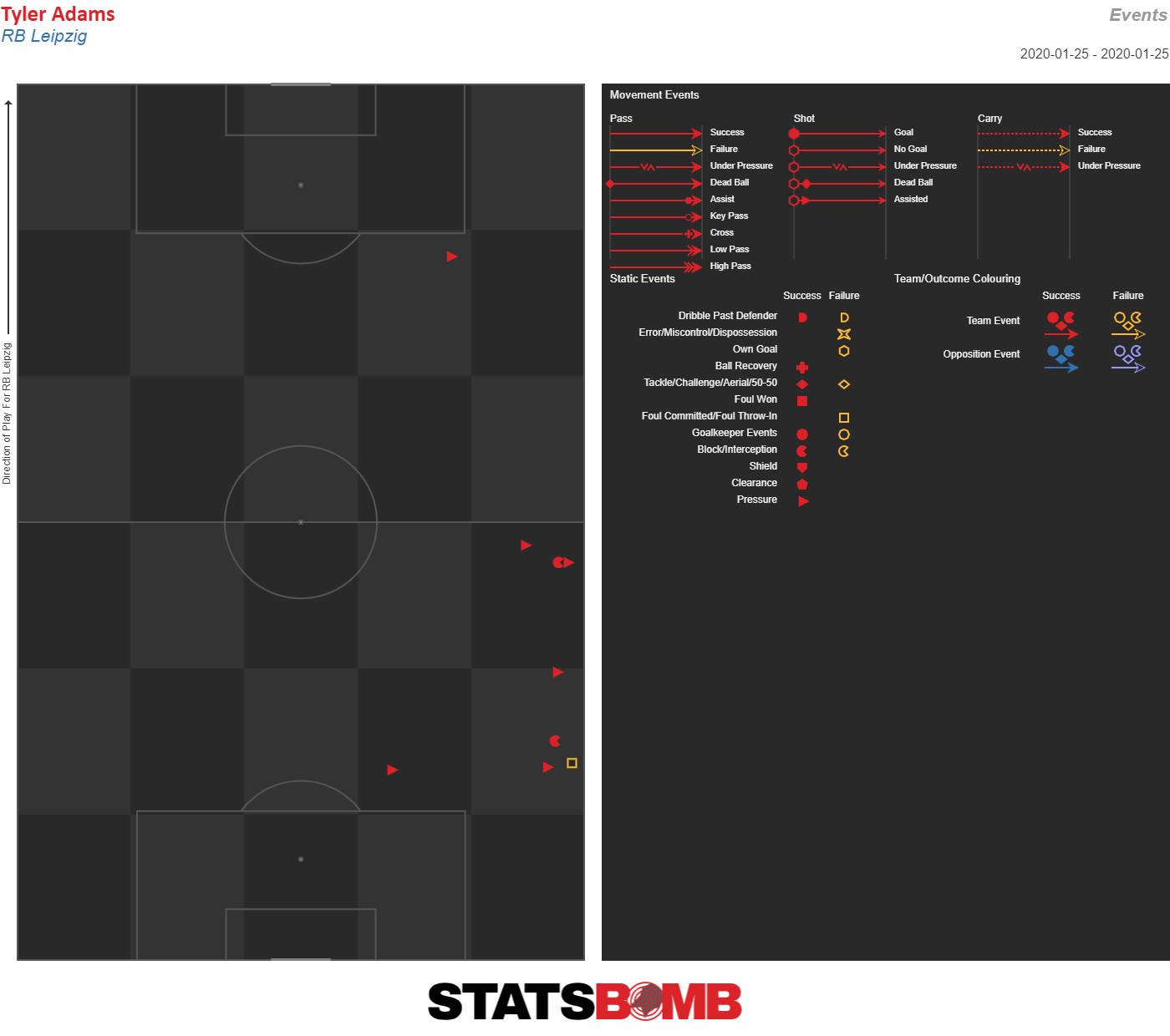

Tyler Adams

Moving into the defence/midfield we have RB Leipzig’s Tyler Adams, whose exact position is a source of great debate that has extended beyond USMNT supporters. Having made the move from New York Red Bulls to Leipzig a year ago, the 20-year-old shocked many by adapting so quickly to the switch from MLS to the Bundesliga. Adams had a string of impressive performances last spring in a defensive midfielder role until nagging adductor problems in April cost him much of 2019.  He made his return as against Augsburg in December and has since split his time at RB\RWB (even switching mid-game, like he did recently against Borussia Mönchengladbach) and defensive midfield. As a midfielder, he is a solid but somewhat unspectacular passer, who for the most part is good at maintaining and circulating possession and can progress the ball. He’s a decent but infrequent dribbler, doing so mostly to get out of pressure, although he's capable of the odd error such as the one prior to Union Berlin’s goal on matchday 18. Ranking in the 23rd percentile of turnovers with 1.91 per 90 minutes last year could become an issue down the road, though at Leipzig he’s at least protected by the out of possession-pressing madman, Konrad Laimer. Adams’ offensive contributions happen mostly in the buildup and more importantly when pressing, which is perhaps his best — but also his least obvious — skill. He has huge range, as seen in the recent Gladbach match where he was often tasked with pressuring the opposing defensive midfielder close to the box, amazing pressure regain numbers and very strong tackling metrics. He is just active.

He made his return as against Augsburg in December and has since split his time at RB\RWB (even switching mid-game, like he did recently against Borussia Mönchengladbach) and defensive midfield. As a midfielder, he is a solid but somewhat unspectacular passer, who for the most part is good at maintaining and circulating possession and can progress the ball. He’s a decent but infrequent dribbler, doing so mostly to get out of pressure, although he's capable of the odd error such as the one prior to Union Berlin’s goal on matchday 18. Ranking in the 23rd percentile of turnovers with 1.91 per 90 minutes last year could become an issue down the road, though at Leipzig he’s at least protected by the out of possession-pressing madman, Konrad Laimer. Adams’ offensive contributions happen mostly in the buildup and more importantly when pressing, which is perhaps his best — but also his least obvious — skill. He has huge range, as seen in the recent Gladbach match where he was often tasked with pressuring the opposing defensive midfielder close to the box, amazing pressure regain numbers and very strong tackling metrics. He is just active.  That explains why Nagelsmann uses him at right back, although the trickle-down effects of their centre back injuries — causing right backs Klostermann and Mukiele to have to play in the centre — obviously has quite a bit to do with that.

That explains why Nagelsmann uses him at right back, although the trickle-down effects of their centre back injuries — causing right backs Klostermann and Mukiele to have to play in the centre — obviously has quite a bit to do with that.  But as seen in his defensive activity map, his skills are perhaps not optimized out wide. At the Bundesliga level, he’s a fine option at fullback/wingback against the more limited sides. Still, Adams can struggle against physical types like Filip Kostić, which to be fair most people also do. His lack of 1v1 skills and elite athleticism are also much more obvious out wide, but he possesses the requisite game intelligence and combination play to do a good enough job, depending on matchups. Still, let’s not forget, Adams is doing all of this at an age where he’s still gotta wait ‘til Valentine’s Day to drink legally in the United States. The fact that Nagelsmann and Leipzig were content letting their vice captain and long-time servant Diego Demme go to Napoli amidst a title run, speaks volumes of the faith they have in Adams. Despite Leipzig’s slight difficulties showing this spring, Adams’ future continues to be bright. If he can solidify his spot for the rest of the spring, showcase himself in the Champions League he might not need to add another solid year next season to go onto something even bigger. Of course, there’s still three chances for him and Leipzig to win some silverware, so let’s not get ahead of ourselves….

But as seen in his defensive activity map, his skills are perhaps not optimized out wide. At the Bundesliga level, he’s a fine option at fullback/wingback against the more limited sides. Still, Adams can struggle against physical types like Filip Kostić, which to be fair most people also do. His lack of 1v1 skills and elite athleticism are also much more obvious out wide, but he possesses the requisite game intelligence and combination play to do a good enough job, depending on matchups. Still, let’s not forget, Adams is doing all of this at an age where he’s still gotta wait ‘til Valentine’s Day to drink legally in the United States. The fact that Nagelsmann and Leipzig were content letting their vice captain and long-time servant Diego Demme go to Napoli amidst a title run, speaks volumes of the faith they have in Adams. Despite Leipzig’s slight difficulties showing this spring, Adams’ future continues to be bright. If he can solidify his spot for the rest of the spring, showcase himself in the Champions League he might not need to add another solid year next season to go onto something even bigger. Of course, there’s still three chances for him and Leipzig to win some silverware, so let’s not get ahead of ourselves….

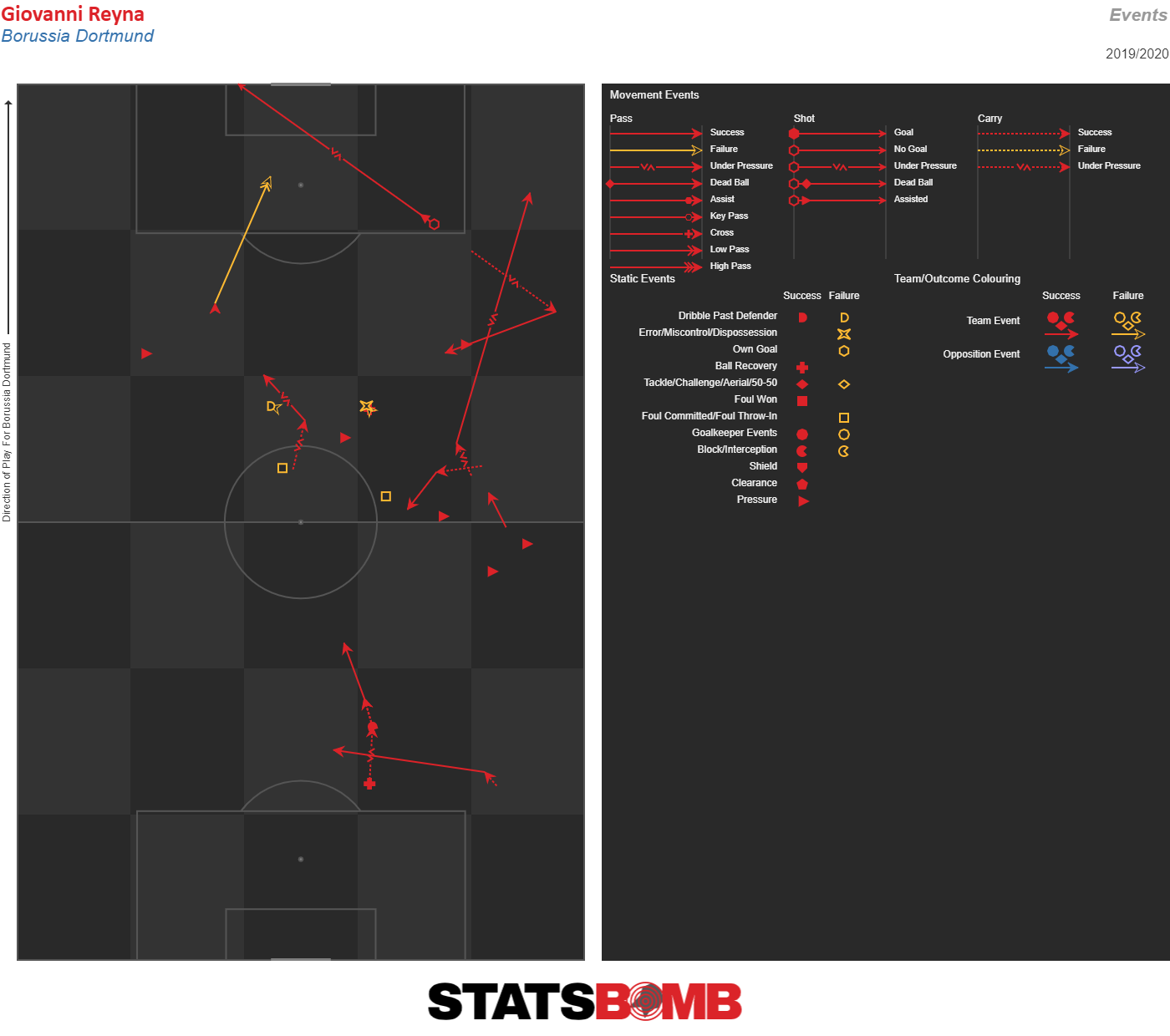

Giovanni Reyna

Speaking of not getting ahead ourselves, meet Gio Reyna, son of USMNT legend Claudio Reyna, himself with some Bundesliga pedigree with Bayer Leverkusen. Like Tyler Adams, Gio Reyna is another NY area product, who somehow was born in November of 2002. It's possible of course you were already introduced during Dortmud's cup match this week when he scored an absolute screamer of a goal in a losing effort against Werder Bremen Before he loudly announced himself on the scene, however, Reyna stole the show at Dortmund’s Marbella training camp this winter and Lucien Favre is smitten by the 17-year-old. First, he got called up to the first team squad in December, but did not take part in the 5-0 over Düsseldorf. Then in January, Reyna was promoted from the U19s to a full-fledged first team regular, and since then he’s been subbed on in all three of Dortmund’s dominant 5-goal drubbings, accounting for 32 minutes. So he’s been flying under the radar, because apparently there’s some Norwegian teenager stealing the headlines from him and Jadon Sancho’s monster season….. Understandably there is extremely limited data on his game - we’re actually going with NO RADARS on this one, but there are 11 matches at BVB U19s with 4 goals and 7 assists and 4 goals and an assist in four UEFA Youth League vs the likes of Barcelona and Inter. What we can show you is literally every single touch he's had in the Bundesliga so far this season.  From the limited footage on video sites there are a couple takeaways: his size allows him to play as a winger, but also as an attacking midfielder. Maybe he can play as an out and out striker, though the less said about the US U17’s disastrous WC last fall, the better. Typically, Reyna receives passes with open body position, has exceptional technique and possesses quick speed of thought with good recognition of when to pass and when to dribble. His tactical understanding is mature for his age, occupying the right zones and positions and releasing teammates into space with quick, precise passes. In addition, he has shown abilities to be a composed finisher in preseason, and as the second option off the BVB bench, with his first first team goal already under his belt, his first Bundesliga goal can’t be far behind. It’s extremely difficult to project his career path - young wingers who arrive from Dortmund can skyrocket like Jadon Sancho or disappear into the abyss like Emre Mor - bonus points if you know where he moved this winter. Still, playing in Europe’s most goal-laden league and for a team that for the next few months might again (sorry Thomas Tuchel) have the world’s most exciting teen footballing duo (Sancho and Haaland), is just about the perfect opportunity. There’s even a certain Chelsea-based American he can ask for the blueprint….

From the limited footage on video sites there are a couple takeaways: his size allows him to play as a winger, but also as an attacking midfielder. Maybe he can play as an out and out striker, though the less said about the US U17’s disastrous WC last fall, the better. Typically, Reyna receives passes with open body position, has exceptional technique and possesses quick speed of thought with good recognition of when to pass and when to dribble. His tactical understanding is mature for his age, occupying the right zones and positions and releasing teammates into space with quick, precise passes. In addition, he has shown abilities to be a composed finisher in preseason, and as the second option off the BVB bench, with his first first team goal already under his belt, his first Bundesliga goal can’t be far behind. It’s extremely difficult to project his career path - young wingers who arrive from Dortmund can skyrocket like Jadon Sancho or disappear into the abyss like Emre Mor - bonus points if you know where he moved this winter. Still, playing in Europe’s most goal-laden league and for a team that for the next few months might again (sorry Thomas Tuchel) have the world’s most exciting teen footballing duo (Sancho and Haaland), is just about the perfect opportunity. There’s even a certain Chelsea-based American he can ask for the blueprint….

Josh Sargent

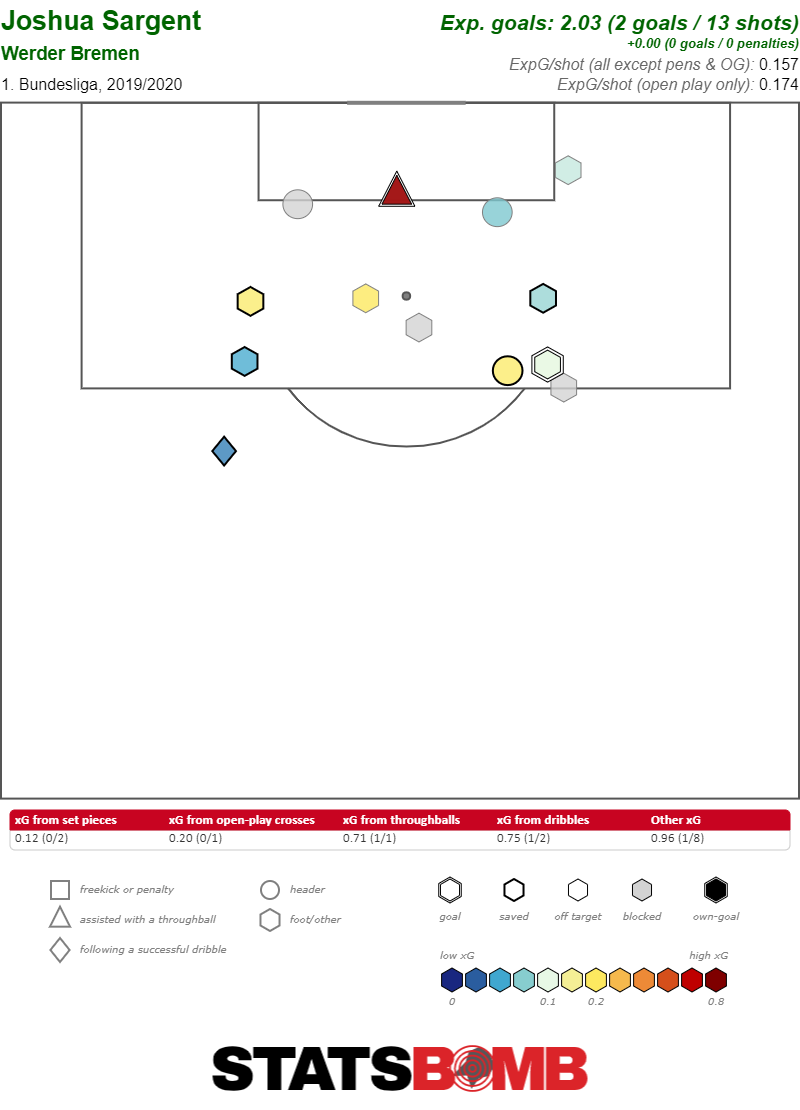

While the other players discussed have shown clear signs of promise, the signals on Sargent are more mixed, possibly due to the fact that he's with a struggling Werder Bremen side. The goodish news is that he does have two goals from two expected, with a sublime, juggling-dinking chip against Augsburg. Furthermore, Sargent’s shots are from good locations and after dribbles, or through balls, which is pretty good for an effective poacher.  Unfortunately, that’s where the positives end so far. While it’s hard to separate his season from the dreadful campaign Werder is having, it’s just not been great. On a related note, who doesn’t miss Max Kruse, last seen trying to win the Turkish version of the Voice? Below you can see the number of open play completions to Sargent in the box by his teammates for this season: a few through balls that he runs onto inside the box, nothing on the left side and a couple down the right.

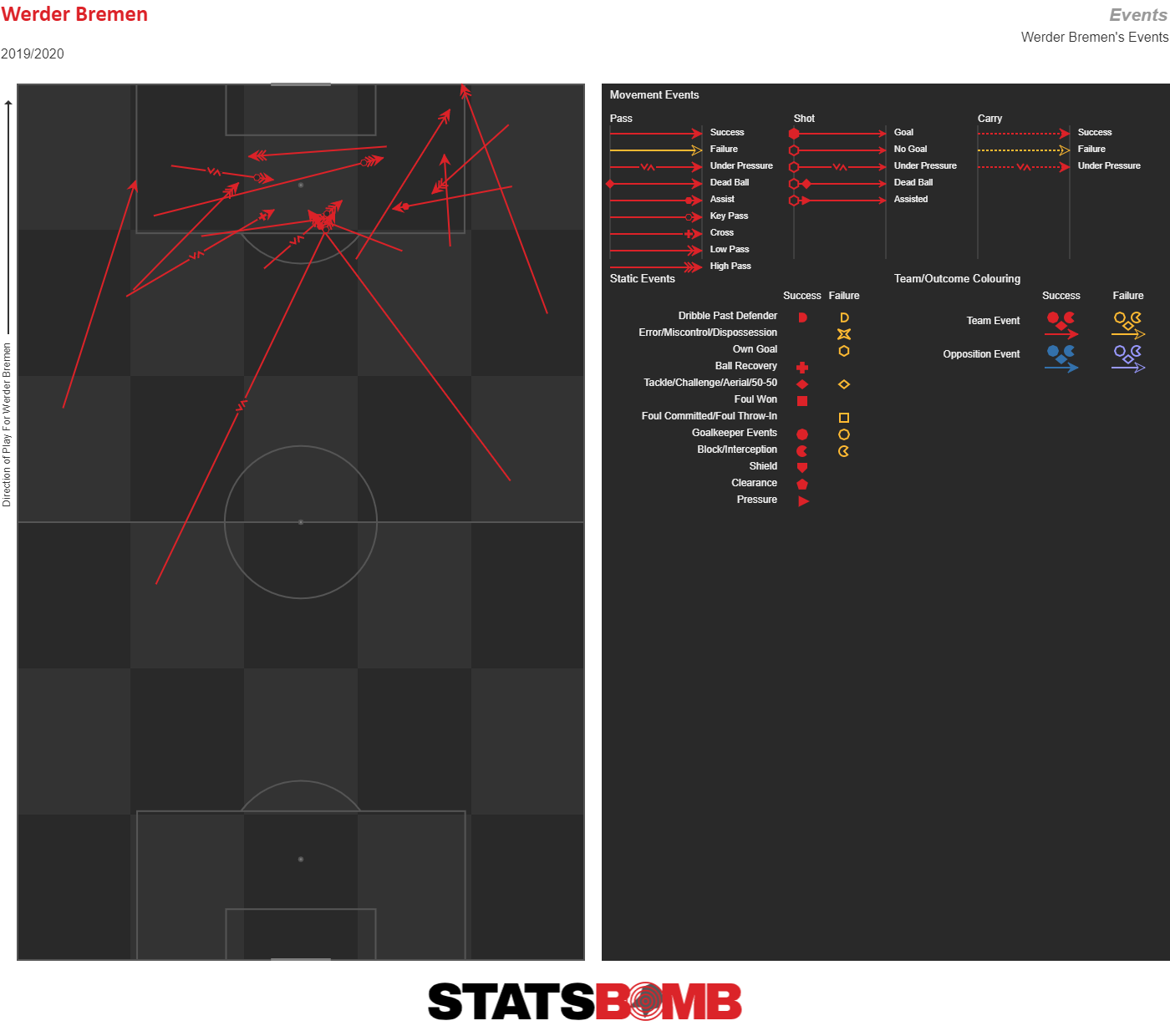

Unfortunately, that’s where the positives end so far. While it’s hard to separate his season from the dreadful campaign Werder is having, it’s just not been great. On a related note, who doesn’t miss Max Kruse, last seen trying to win the Turkish version of the Voice? Below you can see the number of open play completions to Sargent in the box by his teammates for this season: a few through balls that he runs onto inside the box, nothing on the left side and a couple down the right.  What’s interesting is the extremely few long passes that made their ways to Sargent, though as we see below, it’s not been for a lack of trying.

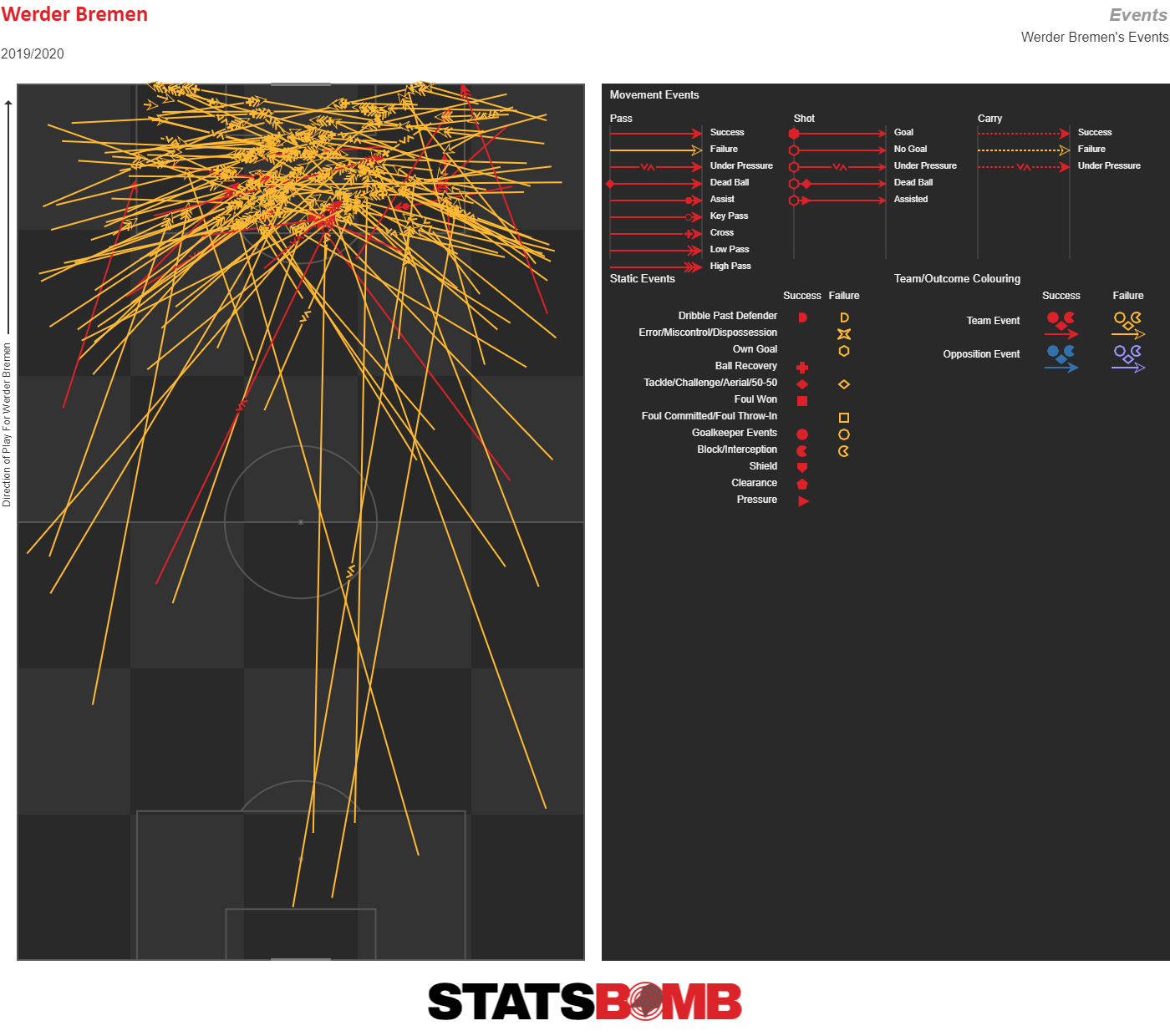

What’s interesting is the extremely few long passes that made their ways to Sargent, though as we see below, it’s not been for a lack of trying.  That’s a lot of yellow for a team like Werder whose progressive coach prioritizes possession. With a number of outstanding playmaking CBs/DMs (Sahin, Moisander and now Kevin Vogt, with Toprak and Veljkovic all in the solid category), you begin to suspect that some of the onus has been on Sargent. The most common criticism from fans, beat writers and commentators alike has been his difficulties in generating a shot on his own, an inability to hold on to the ball and struggles with his first touch and lay-off passes. From the data, the biggest issue with him is not his defensive effort, pressing or workrate which Kohfeldt has praised, but the lack of typical forward output: in the eight 90s he has logged, he takes just 1.56 per 90 and although he has 2 assists it’s on 0.03 expected goals assisted. He isn’t a dribbler, with 0.84 successful attempts per 90. And as you can see above, he’s often a poor/infrequent box presence. After a muscle injury in December, he started in Werder’s first two Rückrunde games, but his days as a sort of starter are coming to an end since on deadline day, Bremen brought Davie Selke back from Hertha. What the future holds for Sargent is very much contingent on Werder’s season unfolding, but ironically, as cruel as it may sound, a relegation personally might not be the worst idea for his development….

That’s a lot of yellow for a team like Werder whose progressive coach prioritizes possession. With a number of outstanding playmaking CBs/DMs (Sahin, Moisander and now Kevin Vogt, with Toprak and Veljkovic all in the solid category), you begin to suspect that some of the onus has been on Sargent. The most common criticism from fans, beat writers and commentators alike has been his difficulties in generating a shot on his own, an inability to hold on to the ball and struggles with his first touch and lay-off passes. From the data, the biggest issue with him is not his defensive effort, pressing or workrate which Kohfeldt has praised, but the lack of typical forward output: in the eight 90s he has logged, he takes just 1.56 per 90 and although he has 2 assists it’s on 0.03 expected goals assisted. He isn’t a dribbler, with 0.84 successful attempts per 90. And as you can see above, he’s often a poor/infrequent box presence. After a muscle injury in December, he started in Werder’s first two Rückrunde games, but his days as a sort of starter are coming to an end since on deadline day, Bremen brought Davie Selke back from Hertha. What the future holds for Sargent is very much contingent on Werder’s season unfolding, but ironically, as cruel as it may sound, a relegation personally might not be the worst idea for his development….

Is Moussa Dembélé worth a potential mega transfer fee?

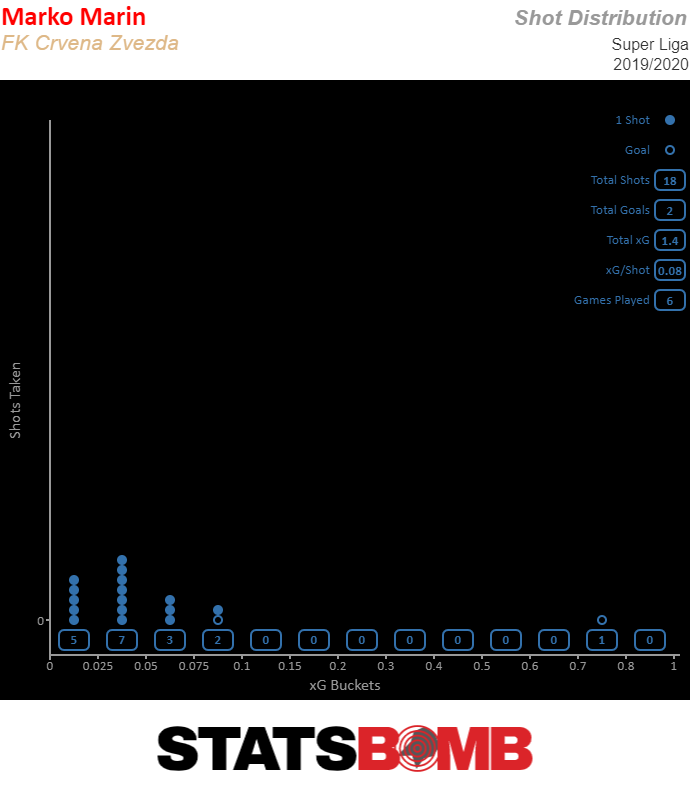

“Boy, the food at this place is really terrible,” a woman tells her friend in a Borscht Belt joke reproduced by Woody Allen (ugh, sorry) in Annie Hall. “Yeah, I know,” her interlocutor replies, “and such small portions.” Replace food with shots and you have Moussa Dembélé, reportedly a transfer target for Manchester United and Chelsea. The 23-year-old Lyon striker is having a bad year. In better times, way back in 2018–19, he took — and converted – plenty of good shots in the box. He didn’t do much else, but that was his job. He was good at it. This season, he’s doubled down on being a target man. He’s winning the ball in the air more and dribbling less. He’s still not doing much in the non-shooting department . . . but now he’s also not doing much in the shooting department. Dembélé is getting fewer shots than the average Ligue 1 striker and the quality of his chances has markedly decreased, all of which adds up to a player who contributes very little.  At the same time, Dembélé is having a hot finishing season. Going into Ligue 1’s winter break, he’s turned chances worth 4.3 expected goals into 8 non-penalty goals. Add in his scoring two of three penalties and you have a player who is tied for third in the Ligue 1 scoring table — just one goal behind Kylian Mbappé (who has played far fewer minutes). If that’s the only figure examined, Dembélé looks like a player on the rise.

At the same time, Dembélé is having a hot finishing season. Going into Ligue 1’s winter break, he’s turned chances worth 4.3 expected goals into 8 non-penalty goals. Add in his scoring two of three penalties and you have a player who is tied for third in the Ligue 1 scoring table — just one goal behind Kylian Mbappé (who has played far fewer minutes). If that’s the only figure examined, Dembélé looks like a player on the rise.  Dembélé is hardly the first player to paper over a bad season with some hot finishing. This dynamic, however, makes the transfer interest somewhat mystifying. Player transfers are wont to reflect goal totals. (See: Pépé, Nicolas.) A club that buys Dembélé will therefore be paying for one of France’s top strikers. If his production falls in line with this season’s underlying numbers, that’s a bad deal. If a club believes Dembélé will return to his 2018–19 form, they won’t be able to buy low because his current season is superficially successful. Neither of those are tremendously appealing propositions. If this season proves to be a blip, those considerations will cease to matter. Members of the public needn’t care whether a billionaire saves some money or pays the full price when buying a good player. But is it just a blip? Lyon are taking five fewer shots per 90 minutes this year than the side that led Ligue 1 by a large margin in 2018–19. While that number suggests team-wide issues, Dembélé is the only player whose shot volume has fallen off a cliff (The drop-off largely reflects Nabil Fekir, a prolific shooter, leaving the club, and Memphis Depay, who had been taking his usual bevvy of shots, being injured). Manager Rudi Garcia’s arrival as the mid-season replacement for Sylvinho hasn’t had any effect on Dembélé’s shooting. It’s not immediately clear why only Dembélé’s shots, and not those of other attackers like Maxwel Cornet or Bertrand Traore, have gone missing. The diminished quality of Dembélé’s shots, on the other hand, is consistent with the team’s other attackers. They may all be feeling the effects of crucial injuries and Fekir and Tanguy Ndombele leaving the club. One glaring example: Dembélé took 19 shots from through-balls in just under 2,200 league minutes in 2018–19; he’s already played more than 1,500 minutes this season and taken one such shot. Worsening service can’t explain away all his issues, but it helps show how his shots have become so much worse while still coming from similarly close and central locations. Bad years happen. Moussa Dembélé is young and may rebound. Insofar as his only value comes from shooting in the box, though, clubs would do well to wait and see if he’s still good at that.

Dembélé is hardly the first player to paper over a bad season with some hot finishing. This dynamic, however, makes the transfer interest somewhat mystifying. Player transfers are wont to reflect goal totals. (See: Pépé, Nicolas.) A club that buys Dembélé will therefore be paying for one of France’s top strikers. If his production falls in line with this season’s underlying numbers, that’s a bad deal. If a club believes Dembélé will return to his 2018–19 form, they won’t be able to buy low because his current season is superficially successful. Neither of those are tremendously appealing propositions. If this season proves to be a blip, those considerations will cease to matter. Members of the public needn’t care whether a billionaire saves some money or pays the full price when buying a good player. But is it just a blip? Lyon are taking five fewer shots per 90 minutes this year than the side that led Ligue 1 by a large margin in 2018–19. While that number suggests team-wide issues, Dembélé is the only player whose shot volume has fallen off a cliff (The drop-off largely reflects Nabil Fekir, a prolific shooter, leaving the club, and Memphis Depay, who had been taking his usual bevvy of shots, being injured). Manager Rudi Garcia’s arrival as the mid-season replacement for Sylvinho hasn’t had any effect on Dembélé’s shooting. It’s not immediately clear why only Dembélé’s shots, and not those of other attackers like Maxwel Cornet or Bertrand Traore, have gone missing. The diminished quality of Dembélé’s shots, on the other hand, is consistent with the team’s other attackers. They may all be feeling the effects of crucial injuries and Fekir and Tanguy Ndombele leaving the club. One glaring example: Dembélé took 19 shots from through-balls in just under 2,200 league minutes in 2018–19; he’s already played more than 1,500 minutes this season and taken one such shot. Worsening service can’t explain away all his issues, but it helps show how his shots have become so much worse while still coming from similarly close and central locations. Bad years happen. Moussa Dembélé is young and may rebound. Insofar as his only value comes from shooting in the box, though, clubs would do well to wait and see if he’s still good at that.

Olmo and Stevanović and Chalov oh my: Transfer targets you should know from Eastern Europe

Transfer season is here. While many of the headlines will focus on big rumors about big players in big leagues, there's a whole lot more soccer out there. So, here are four players from across eastern Europe who might catch a smart team's eye.

Dani Olmo, Dinamo Zagreb

What’s surprising is that Dani Olmo is on this list—although perhaps by the time you’re reading this, he’ll have signed with one of the major Spanish clubs (for example, it’s rumored that Barcelona, the team of his youth, have made a formal offer) or for Chelsea (who appear to be chasing every sweet young thing in eastern Europe).Some of us have a type, and for me, that type is an attacking midfielder who usually plays on the wing (and truth be told I prefer a left-winger, naturally). I fall more deeply in love if that winger is good with the ball at his feet

The surprise about Olmo isn’t that some would argue that Croatia is not part of “eastern” Europe, it’s that the Barça youth product hasn’t left Dinamo Zagreb already. He signed for Croatia’s most successful team when he was just 16, part of the deal that sent Alen Halilović to Barcelona, and it’s fairly obvious that it’s Dinamo that got the upper hand in that exchange. His four years in Croatia have shaped him into the best player in the domestic league by far, and he showed his skills to a wider audience in this year’s Champions League, first scoring against Shakhtar Donetsk, then recording the opening goal in the eventual 1–4 defeat to Manchester City.

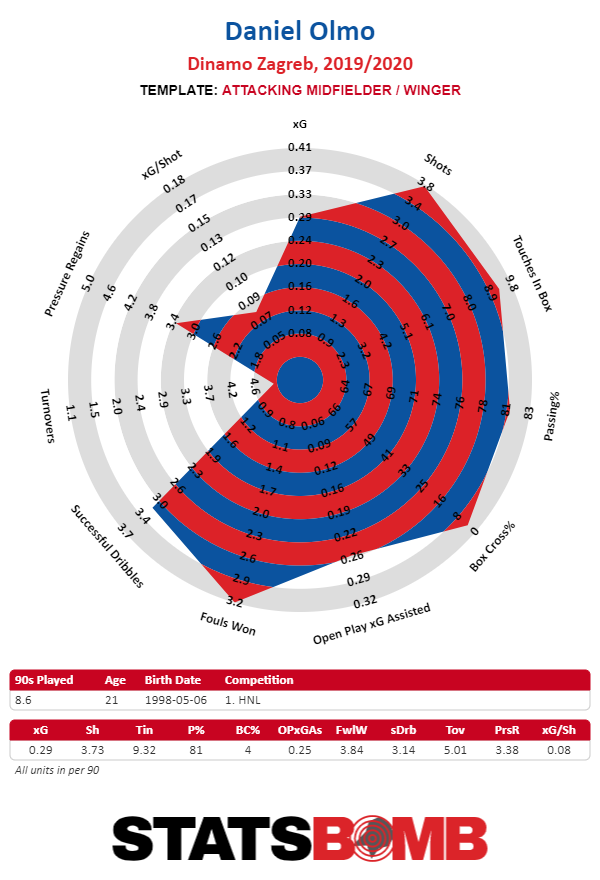

Sure, two European goals does not maketh the man, but a lot more production at home in his domestic league sure does maketh the radar.

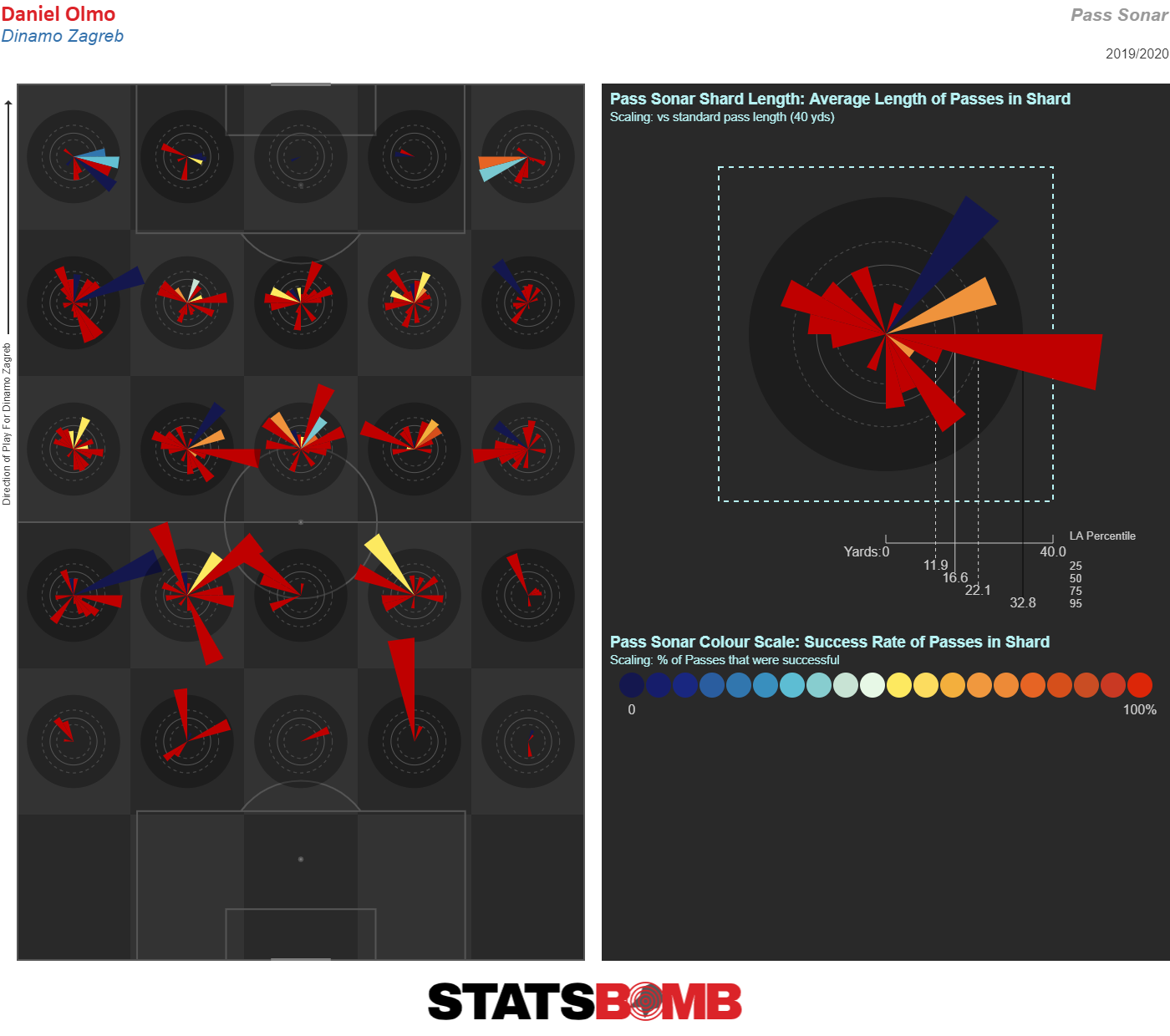

Those who paid attention to Dinamo, particularly those of us who also happen to be lovers of Atalanta who were shocked to see them knocked down 4–0 in Zagreb, will have noticed Olmo is the one who directs his side’s play. He’s an attacking midfielder/winger with an excellent dribbling technique (especially noticeable during those Champions League matches) with the ability to change his pace quickly, making it easy for him to lose his marker. This allows Olmo to boss the game all over the field; as his passing sonar shows, he’s capable of picking the ball up all over the place and progressing Dinamo up the field.

This strategy allows him to create opportunities in which Dinamo are two against one in the attacking zone. Plus, he’s on the short side—what more can one ask for in an attacker? Olmo has clearly outgrown the Croatian league, and his talents make it almost certain he’ll be snapped up in January.

Filip Stevanović, Partizan Belgrade

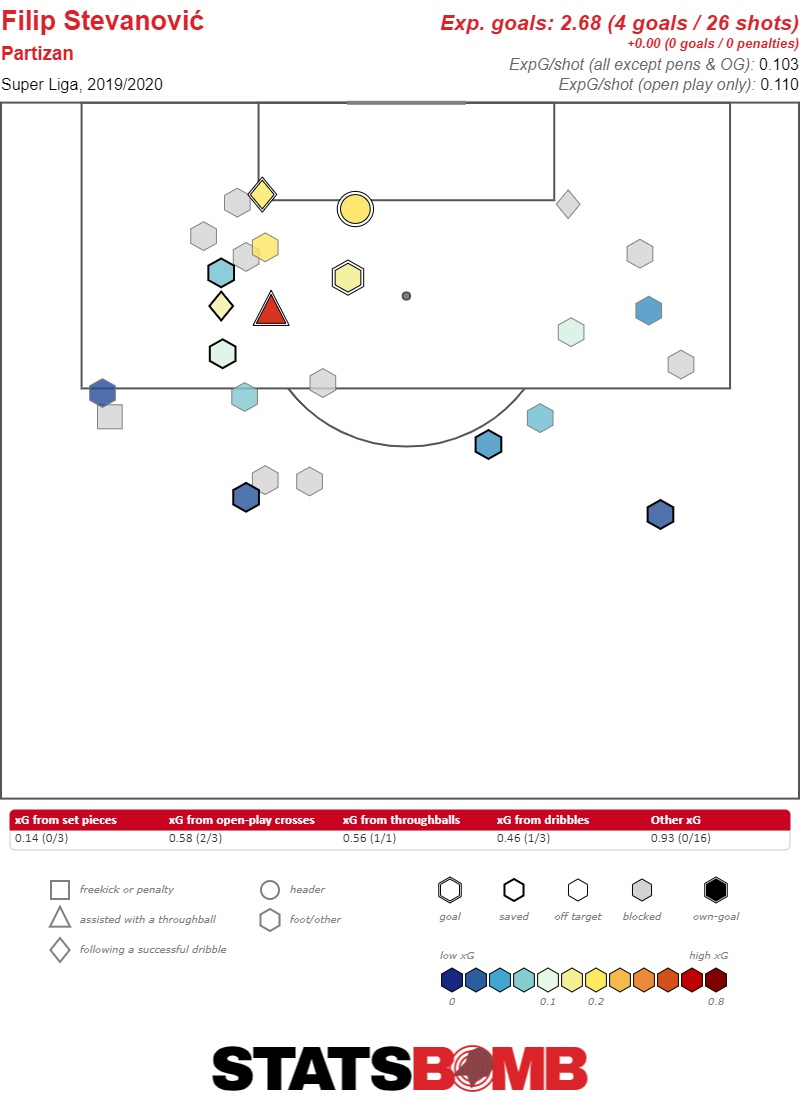

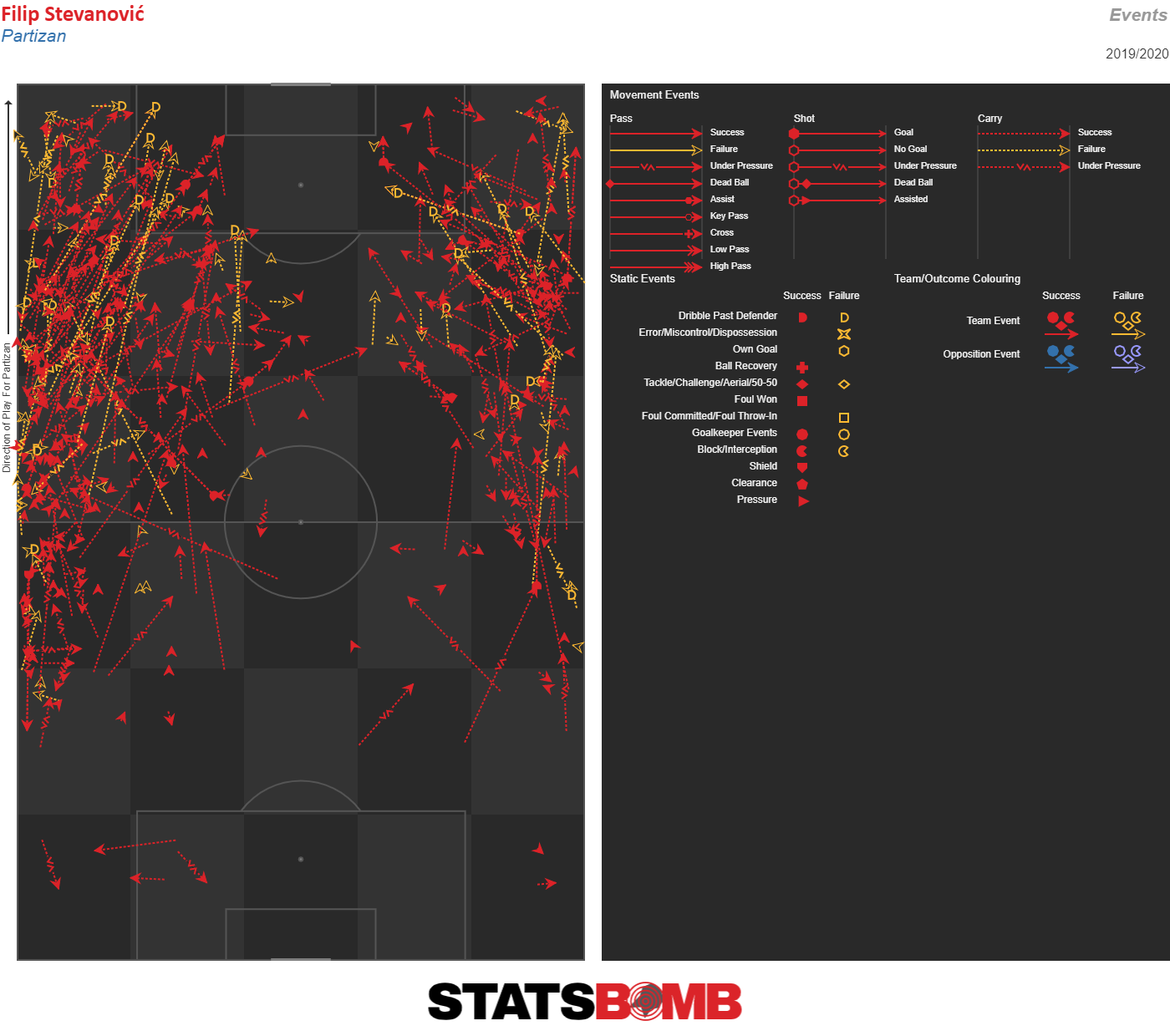

The latest product of Partizan’s famous youth academy made his senior debut last season, when he was just 16—just like Luka Jović did for crosstown rivals Red Star six years ago. And while Stevanović is no imposing central forward (he is, surprisingly, another small attacking winger), it’s not hard to imagine he’ll end up at a club like Real Madrid someday. But, like his fellow Serbian U-21 player, it’s likely he’ll need to jump through a few hoops to get there, given that he’s barely 17, and still isn’t starting in every Partizan match. Then again, the Grobari employed a bit of a rotation system at the beginning of the season, attempting to battle it out for a spot in the next round of the Europa League while closing the 11-point gap between themselves and Red Star at the top of the table. They’ve not succeeded, but it’s not for any lack of talent on Stevanović’s part. The left winger has scored 4 in 14 this season, and tacked on his first European goal against Wales’ Connah's Quay Nomads, way back in the second round of Europa League qualification. There might be a little bit of good fortune in those shooting numbers, but given his age even the 2.68 expected goals he’s totaled is darn impressive. Clearly, Stevanović is never one to shy away from taking a shot from distance and while that might be something that eventually needs to get drilled out of him, he is, again, only 17 years old.

Truly, though, what’s attractive about the youngster is that he’s simply fun to watch. In addition to his fine technique, he possesses fantastic speed. His quickness makes it almost impossible for defenders to track him, plus he loves implementing a good trick to get past an opponent. Sometimes he goes for the more attractive move, rather than the pragmatic one, but that’s likely to improve as his youthful arrogance decreases (and he is faced with more challenging opposition). Good thing, too, because his love for having the ball at his feet often places him further away from the opponent’s goal than he should be—but all those flicks, tricks, and skills means he’s relentlessly attacking the edges of the penalty area.

Given his bursts of speed and developing skill with the ball at his feet, a mid-sized club from one of the top leagues should seriously consider stepping in and snatching him up for a low price, then molding him into the player his talent suggests he could be.

Fyodor Chalov (Fedor), CSKA Moscow

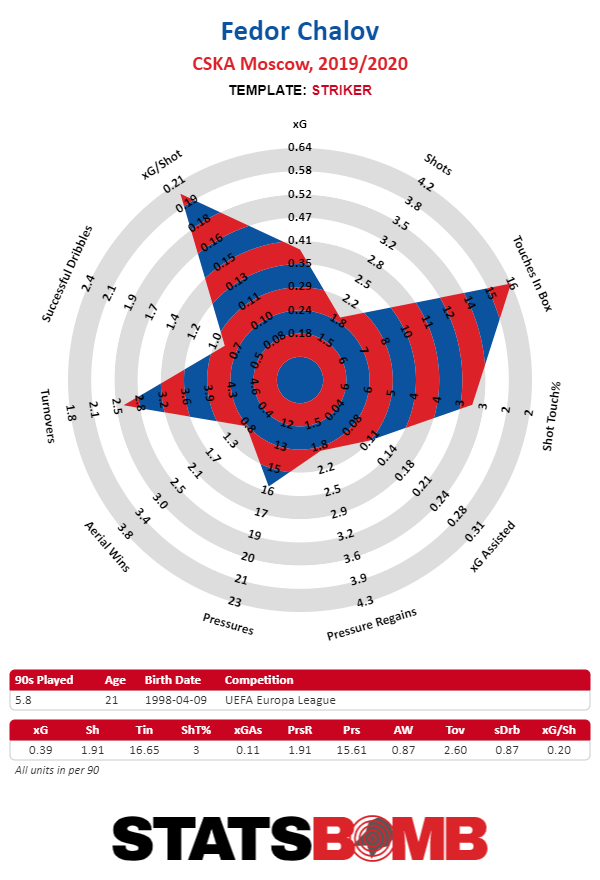

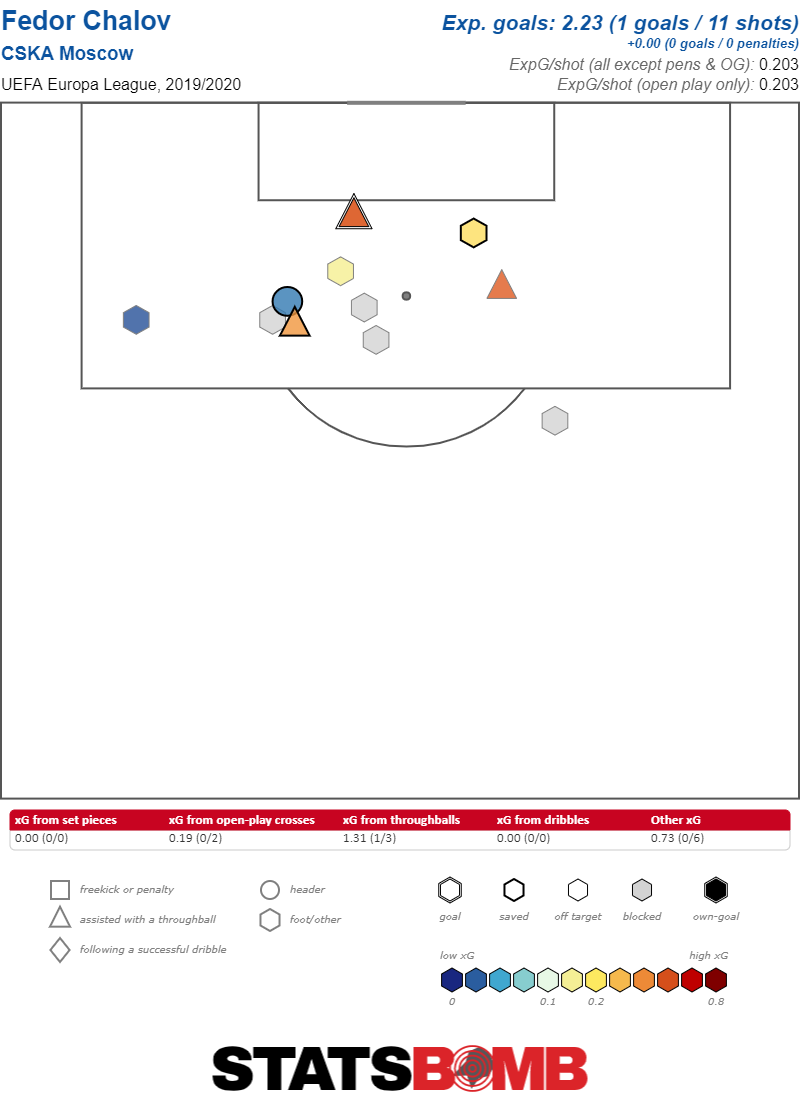

Fyodor Chalov is perhaps one of the most interesting players to come out of Russia since . . . Andrei Arshavin? We can only hope that if he gets snatched up by the likes of West Ham or Chelsea, he’ll give the same sort of bonkers responses that Arshavin used to come out with. But this is an article on football prowess, not my obsession with Andrei, so back to Chalov. Alas, the 21-year-old is not having the best of seasons, having scored only 5 goals in 19 games thus far. Yet if August is silly season, January is absurdity season, and clubs needing a forward may come forth with large wads of cash for a man who scored 15 goals and provided 7 assists last season. And, while the sample size might be small, it’s hard to argue with these Europa League numbers.

It helps that Chalov is a modern forward, one with a nose for goal yet willing to participate in the buildup. He’ll make his own chances happen, and if left any space in any part of the penalty area, he’ll take a shot, being equally adept with both feet. His profile in Europe is one of a player who doesn’t shoot often, but is careful to pounce on the best goalscoring opportunities.

The lack of shot volume might be a concern if he wasn't capable of creating chances for his teammates through his credible passing play. Perhaps his biggest downside is his physique; he is by no means weak, but ball protection and aerial duels can sometimes be a problem. He operates better when he has space to outrun his opponents, and even more so when he has teammates who are also able to threaten the defense, which may be why he’s faltering now—his only real help is coming from midfielder Nikola Vlašić, who’s scoring his own goals. It may be he needs to part of a squad that provides a larger number of credible threats, drawing defenders away from Chalov. Personally, this Aston Villa fan would be fine with him stepping in to compensate for Wesley, who’ll be out for the rest of the season.

Dennis Man, Fotbal Club FCSB [Steaua]

Dennis Man, a 21-year-old attacker described as “one to watch,” may already be on your radar screen if you watch a lot of Romanian football, paid close attention during the 2019 U21 Euros, or enjoy watching Malta get beaten in their attempts to qualify for world competition (having earned his first senior cap in 2018, he first scored for the Romanian national team in their 4–0 victory last June). Man, currently playing for the club once known as Steaua Bucharest and now referred to as FCSB, is expected to leave Romania this summer at the latest, but he could be snatched up by a club eager to turn their fortunes around midseason. In fact, Steaua reportedly rejected a €15m bid from Manchester United in 2018, saying the price was too low. Given his buyout clause is €100 million, that’s not terribly surprising. It’s hard to say whether Man is worth that much, but we’ve seen desperate clubs pay ridiculous prices for far less before.

Man has a tendency to dribble past anyone who gets in his way. Usually I prefer my favs to be a bit on the short side, but even at 6’0”, he isn’t physically imposing. Instead, his strength lies in his fantastic technique and his orchestration of play. He tends to cut in from the right, getting into promising positions that help create goals for Steaua—or the opportunity to net one himself. His numbers are about what you’d expect from an attacking midfielder, with 10 scored last season, and 4 after 15 league games. But the thing is, he doesn’t take too many shots, so when he does fire one off, it’s likely to go in. It’s little wonder, then, that Sevilla are rumored to be after him, particularly as his technical qualities seem particularly suited to La Liga.

Harry Kane and the death of a shot monster

"Harry Kane is Broken" fever is sweeping the soccer Twitter world. And that was before Harry Kane actually limped off the pitch against Southampton on Wednesday with an apparent hamstring injury. Nearly a year ago, Ted Knutson first mentioned on the StatsBomb podcast that Kane might be Fernando Torres-ing. I was resistant. I thought some time off this summer, time he did not have in 2018, would finally give him some rest and let his ankles heal, helping him to regain the proprioception that allowed him to Moneyball his way to becoming a shot monster despite his relatively limited athleticism.

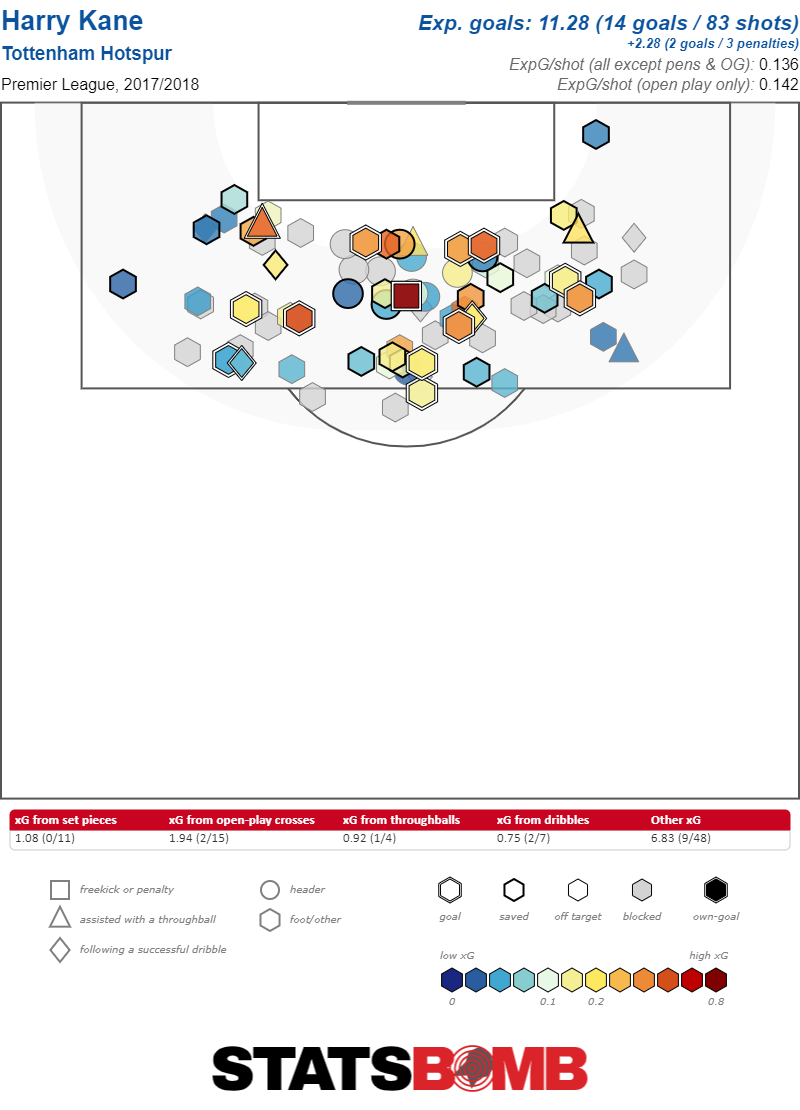

That's certainly not happened. He’s declined markedly in terms of shot generation and has not made up for it by improving elsewhere. However, Kane has managed to maintain his elite finishing ability. Over his career, he has outperformed his non-penalty expected goals by around 20%. When he kicks the ball, he still hits it hard and to the right places.

The problem is that he does not shoot anymore. When Nabil Bentaleb and Ryan Mason were Spurs’ midfield in 2014–15, Harry Kane took 4 shots per match. At his best, in 2017–18 (before the ankle injury that truly derailed his career), he took nearly 6 shots per 90 minutes. Now, Harry Kane attempts under three shots per 90, and his xG per shot has decreased. His non-penalty xG per 90 is a paltry 0.3. Relatedly, in 2017–18 Tottenham had 1.8 xG per match but have dipped to 1.3 xG per match, even as Son Heung-Min remains excellent. It’s bad, folks.

Throughout the Tottenham fan sphere, debates rage over whether Kane himself is just bad, or the team is bad and so he's not getting service. It seems mostly the former, but if Kane can learn to age more gracefully, the team's other weaknesses will be more evident. To recover some of his greatness, Kane really needs to stop trying so hard to make things happen.

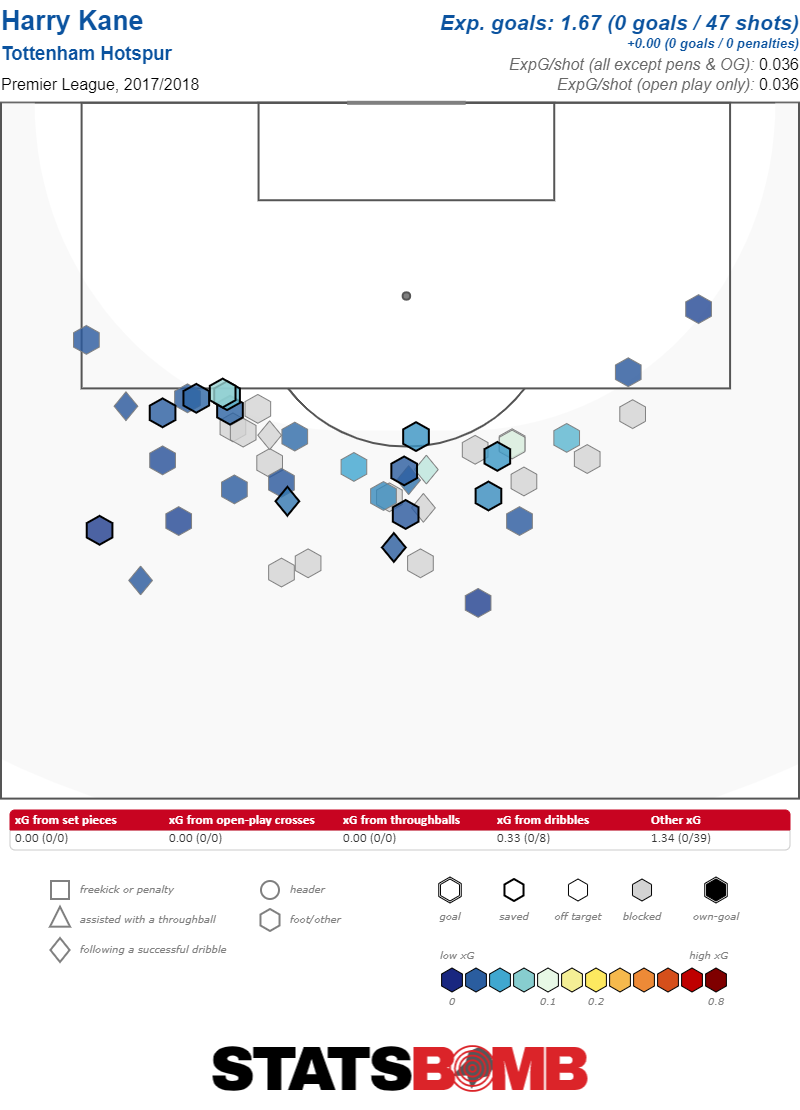

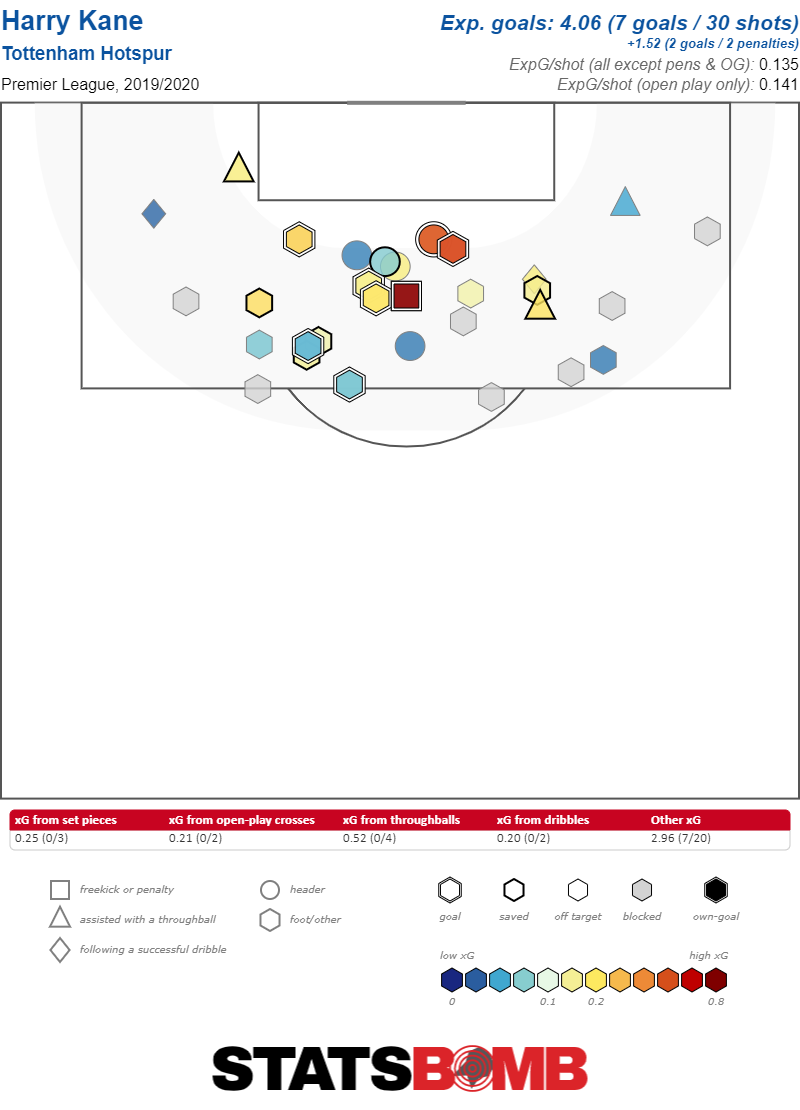

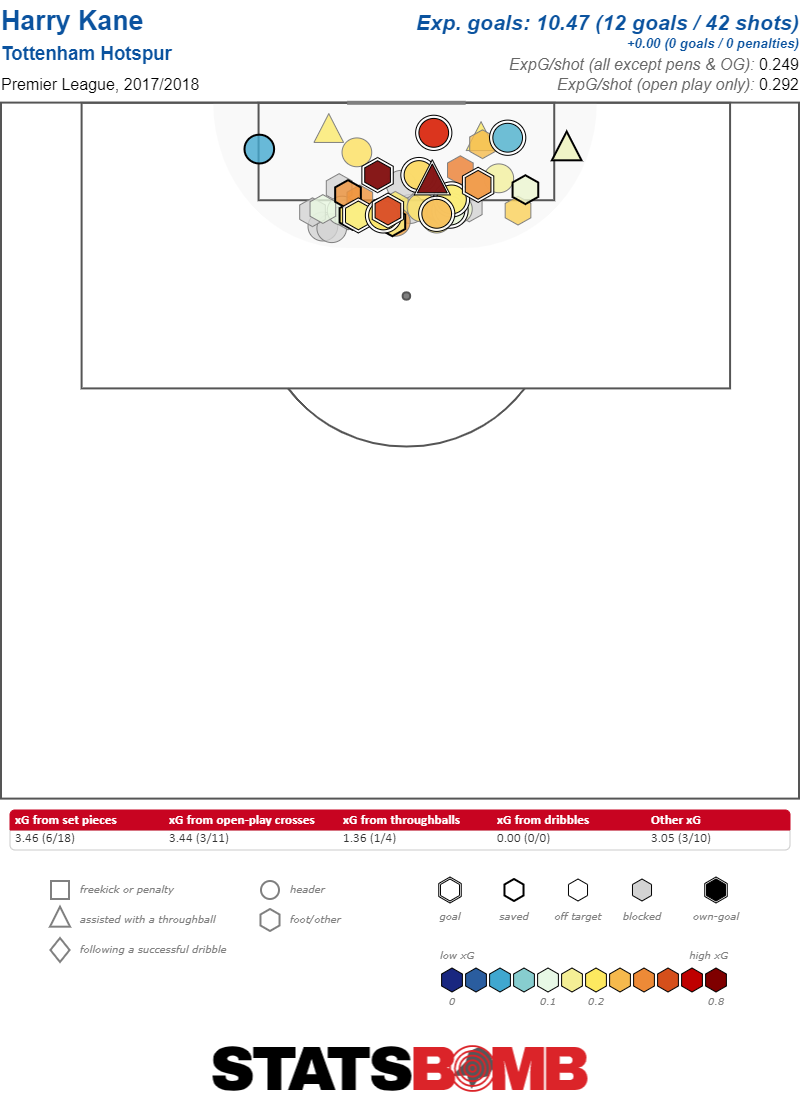

Kane used to be exceptional at letting off shots close to the goal. Using StatsBomb’s shooting charts, I divided Kane’s 2017–18 and 2019–20 shot maps into three areas: within 9 yards of the center of the goal, between 9 and 21 yards of the center of the goal, and 21 yards or more from the center of the goal.

Outside of 21 yards, Kane had 49 shots (not including free kicks) and 1.8 xG in 3000 minutes in 2017–18.

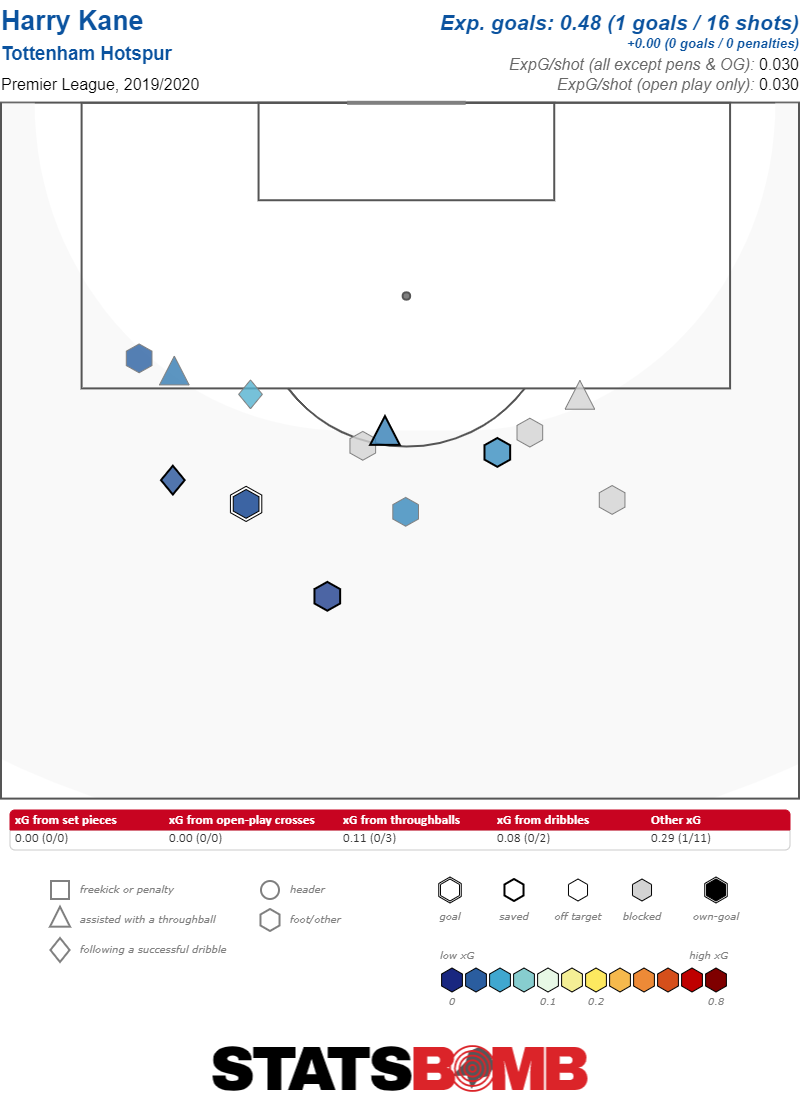

This season it’s 16 shots and 0.48 xG in 1800 minutes. Frankly, it was wasteful to have so many shots from outside the box, so reducing that volume from 1.5 per game to 0.8 per game is actually good.

Since 2017–18, Kane's production from 9 yards to 21 yards from the center of the goal has decreased. This is the area where Kane would create shots inside small amounts of space and let them rip. In 2017–18 he had 83 shots and 11.3 xG in that zone.

This year, 30 shots and 4.06 xG. He's lost another 0.75 shots per match and a tenth of an expected goal per match. That might seem almost insignificant, but over the course of a season it adds up to almost four goals, a large difference in any strikers' total. Little differences add up.

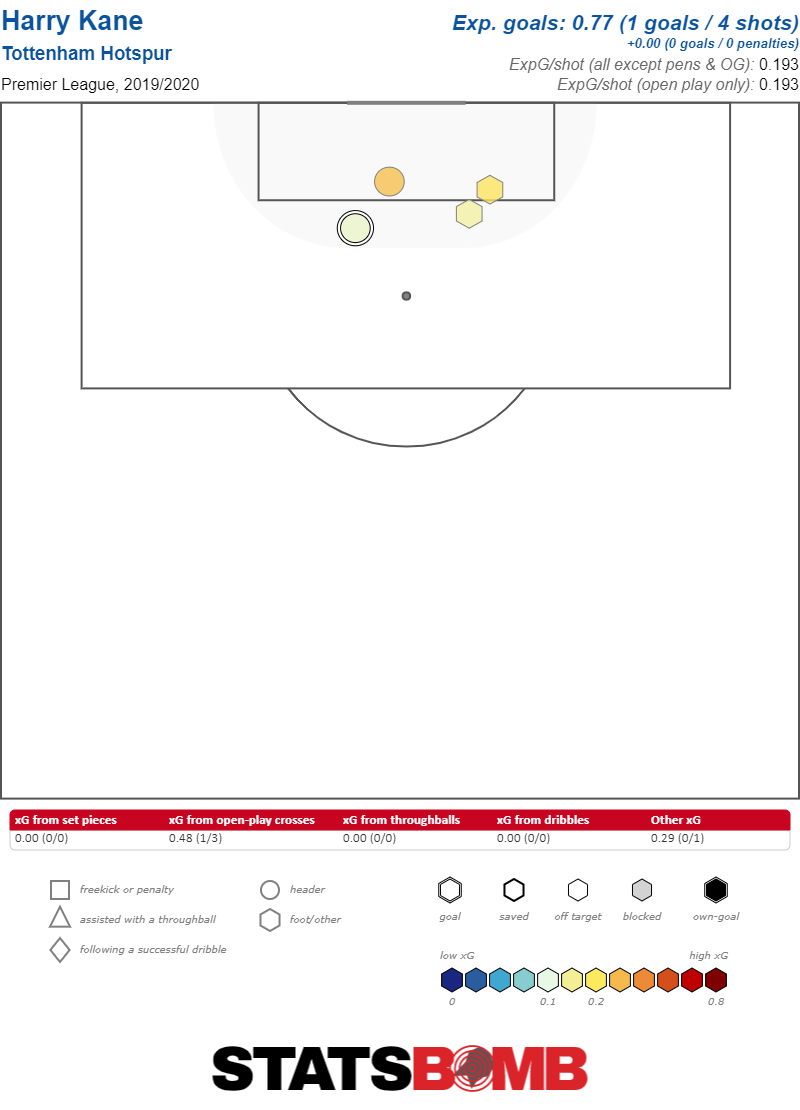

And then it gets worse. Within 9 yards of goal? Utter collapse. In 2017–18, Kane took 42 shots from within 9 yards of goal and had 10.5 xG.

This season, he's at 4 shots and 0.77 xG. In 2017–18 he managed nearly 0.33 xG per 90 in the area around the goal. His numbers have dropped dramatically to 0.05 per 90. If a tenth of an expected goal per match adds up to real differences, a quarter of an expected goal per match lost is enough to cause a career to implode.

Harry Kane was never just a tap-in merchant, but he was great at it, and considering it requires a ton of skill, this made him extremely valuable. He could get into great positions and fire off a shot, or stick a leg out. He was just there, ready to shoot.

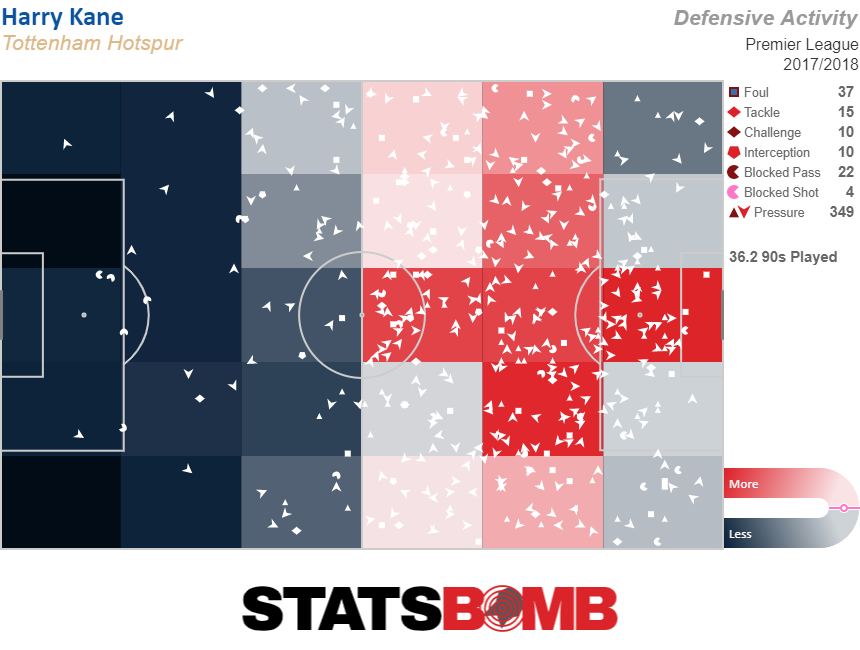

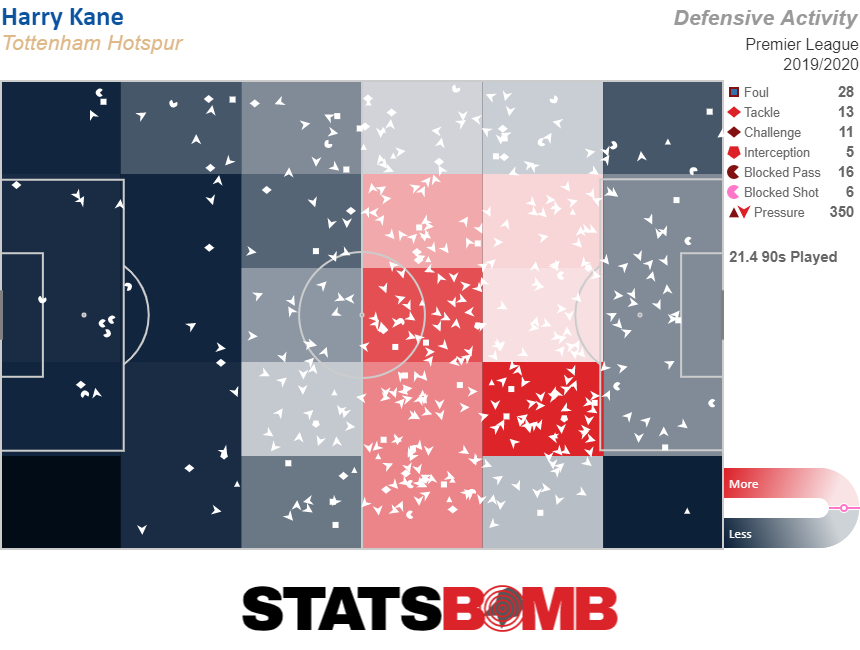

Now? Now he’s everywhere else, and it’s bad. Harry Kane’s defensive activity map from that 2017–18 season reveals a literal red cross in the center of the attacking area. He had 9.63 pressures per 90 that season.

And then there's Harry Kane’s defensive activity map for this season. He has 16.32 pressures per 90 this season, yet the penalty box is gray. His activity is deeper and more dispersed across the pitch. His athleticism has decreased, but he's also running more—and everywhere—this year. These stats totally confounded me, as my impression watching Spurs was that he wasn’t making runs, but now I think he is, just during the wrong stage of play.

He is, verifiably, one of the greater kickers of a soccer ball in the world. He should kick more, and run less, when Spurs are out of possession, saving his energy for bursts in the box. When José Mourinho came to Spurs there was hope Kane would be told to sit in the box and wait for the ball, then kick the ball or head the ball. He has not. Kane is constantly receiving passes in the channels and trying to cut inside, something he should do far less. It’s not just a numbers thing. Every match makes it evident Kane out of position to do the thing he was put on this Earth to do, kick the ball hard at the corner of a football goal. He isn’t lurking off a defender's back shoulder and making runs to a post, leading to a shockingly small number of shots in the six-yard box. Instead, he’s lingering at the edges of the box, trying link up play and DO STUFF.

It almost seems like a bad habit, picked up from too many matches in which Moussa Sissoko and Harry Winks were unable to control possession in midfield. That midfield has been a mess for nearly two seasons now. Kane seems to feel some responsibility to help out, to chase the ball and to defend. In fact, he appears desperate to do so, perhaps thinking that if Spurs don’t have the ball, then he can’t get it and score. And in a sense he's right. But this is why Spurs’ inability to control the midfield has exacerbated Kane's health issues. Yet it’s not what he’s put on a soccer field to do. He was always solid at leading a press on the tip of the spear, arcing his runs in pressure, triggering Mauricio Pochettino’s press. But he has never been fast, nor has he been a great defensive forward.

When Kane was younger and healthier, he could do it all: run hard, get into channels, and still have the energy to make constant runs to the posts. He doesn’t have that anymore. He needs to accept it. When he returns from his latest injury, Tottenham need to create a system in which they win the ball back better without his help, and then maybe he can get back to doing what he does best: get ball, find space, kick ball hard.

Header image courtesy of the Press Association

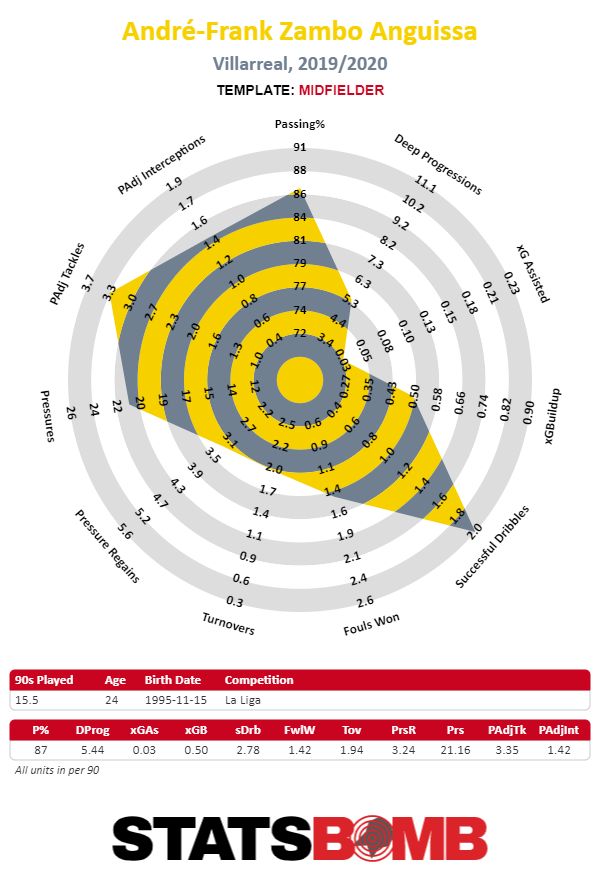

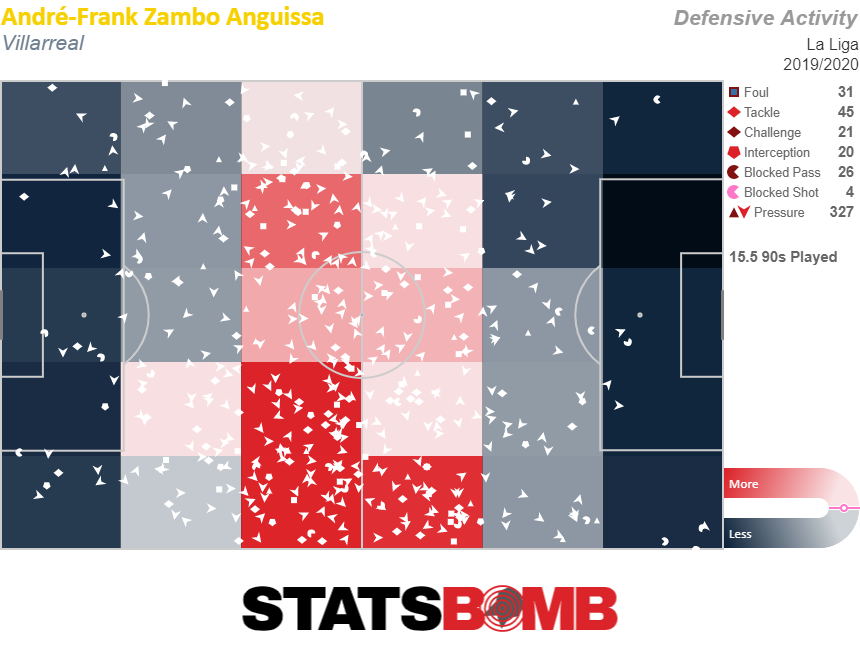

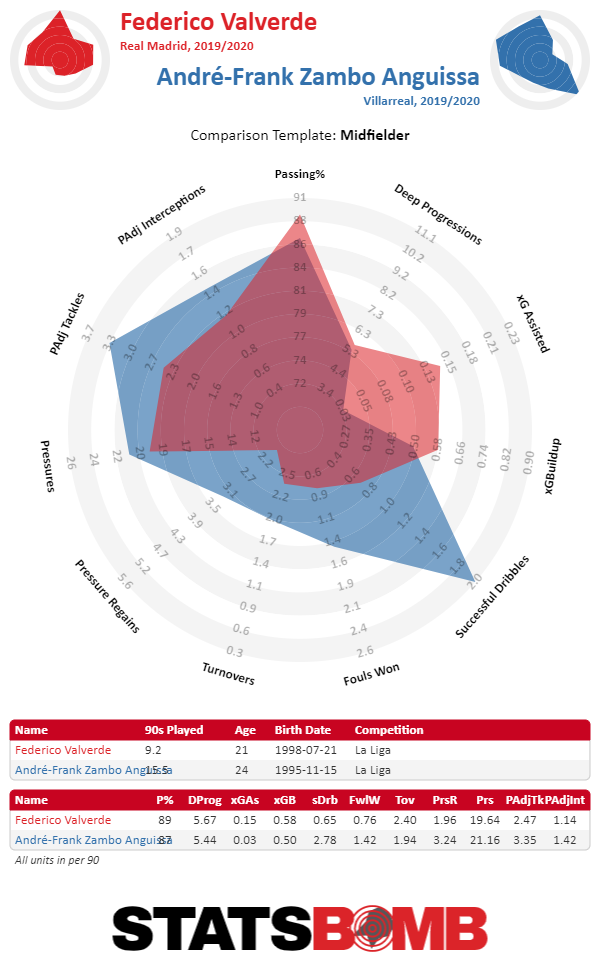

André-Frank Zambo Anguissa is tearing it up for Villarreal

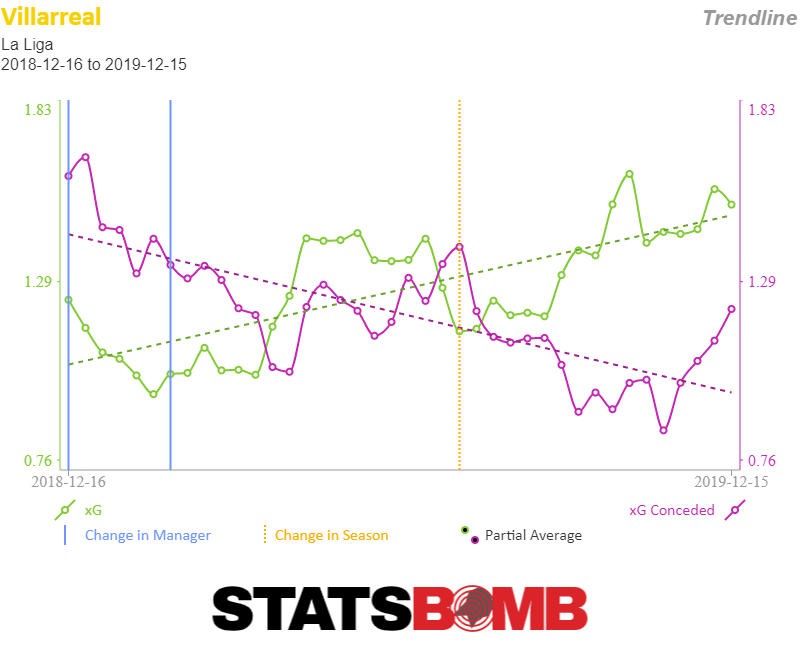

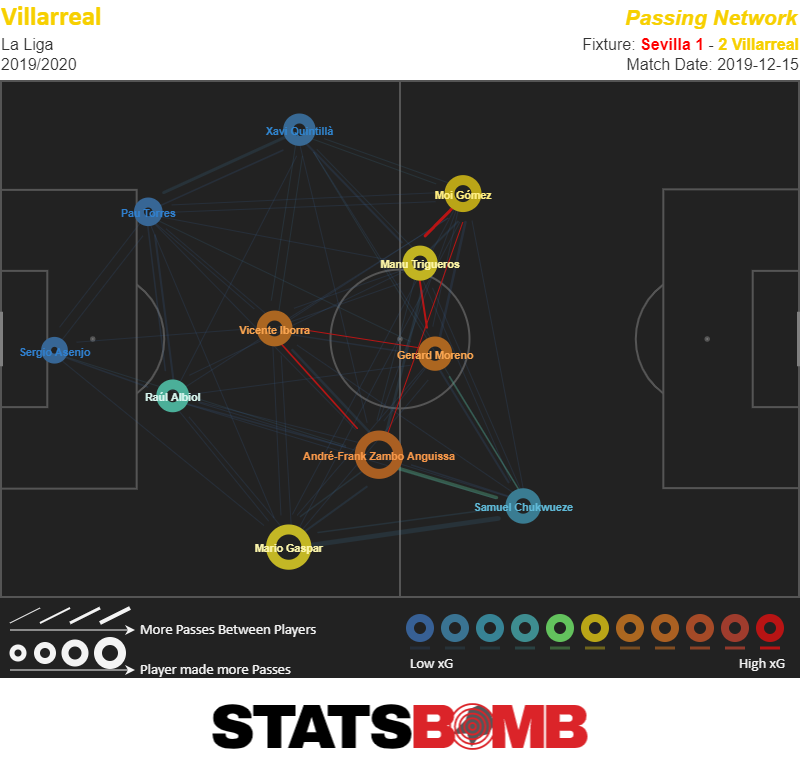

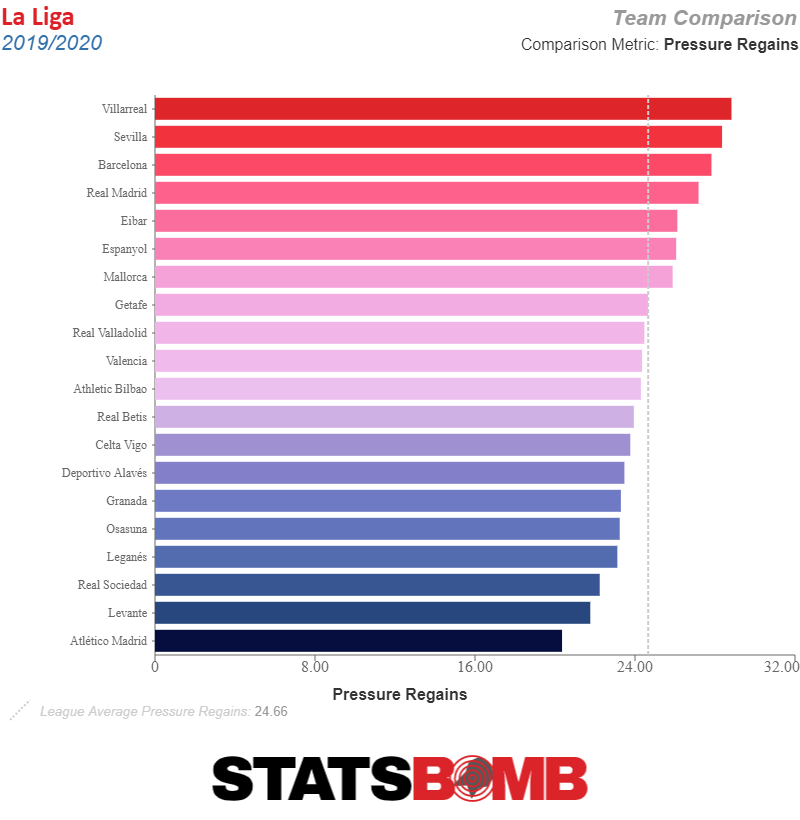

There is quite a bit of variance in Villarreal’s expected goals difference. At least there was. Javi Calleja took back his old job last season and while there has been turbulence, the Yellow Submarine are now floating above the clouds and trending toward a more steady second half to their season.  Calleja was sacked in December 2018 after 15 months in the job and replaced by Luis García, who lasted less than two months before the club brought back Calleja. The returning coach guided them to safety in La Liga and then went about replacing some key losses during the summer. Pablo Fornals, one of Spain’s most exciting talents, went to West Ham in the Premier League, and both Nicola Sansone and Roberto Soriano left for Bologna. They overhauled their defence with players like Raúl Albiol and Alberto Moreno. Perhaps most significantly, they took advantage of Fulham’s relegation from England’s top flight to bring in a player who, since signing on loan, has been sensational. André-Frank Zambo Anguissa arrived at Craven Cottage in August 2018 and never settled at the club, being played out of position and never receiving a decent run of games to showcase his ability. There were glimpses but there were also complaints that he wasn’t good enough. Or that he wasn’t worth the money spent on him (close to €25 million). The problem was Fulham's complete lack of vision upon their return to the Premier League unless, of course, you consider buying lots of expensive and exciting players and throwing them on the field together a "vision". At Villarreal, Anguissa has a role. He's started all but two of the team's games in La Liga this season, including the last 14 straight. Around Anguissa, Villarreal have some of the most exciting footballers in Spain, and Calleja has them playing a thrilling style of football. Santi Cazorla remains brilliant. Gerard Moreno is playing like an elite attacker, Ekambi is constantly dangerous and the whole of the latter’s partnership might even be greater than the sum of its parts. They also have a high-functioning and energetic midfield with players like summer recruit Moi Gómez and the precocious Samu Chuckwueze, but Anguissa might be the most important. On Sunday, during a surprising win over Sevilla at the Ramón Sánchez Pizjuán, Anguissa played as the right central midfielder in a 4-1-4-1, protecting Vicente Iborra and picking up the pesky and intelligent mover, Franco Vázquez, as he dropped between lines. He was forced to be more reactive than usual, creeping silently into dangerous spaces, but was also proactive in chasing Éver Banega in an attempt to prevent him from influencing the game. But it wasn't just his defensive work that stood out. When Villarreal beat the odds to take all three points from Sevilla at home, they did it despite being subjected to intense pressure and precise passing all night, causing them to struggle for very long patches of the game. Their best moments of the attack, however, often came thanks to Anguissa serving as perhaps their most promising attacking outlet, as the passing map shows.