Poor unfortunate Atalanta.

The top rungs of Italian soccer are populated almost exclusively by household names. Clubs like Juventus, Napoli and crosstown rivals Inter Milan and AC Milan along with Roma and Lazio dominate the upper regions of the table. But, amongst the giants there is one side that has managed to thrive. Atalanta probably won’t qualify for the Champions League, they currently sit in a thee team tie for sixth place, six points behind fourth place Milan (albeit with a game in hand) and two behind fifth place Roma. But the table can be cruel, and despite their position, there’s a real case that Atalanta have been the third best team in Italy this season.

On a very basic level, their goal difference is the fourth best in Italy. They’ve scored 18 more times than they’ve conceded this season, only Juventus, Napoli and Inter Milan have managed a better return. It’s just that they’ve failed to turn that goal difference into points at the necessary rate, a factor which tends to be largely out of a team’s control.

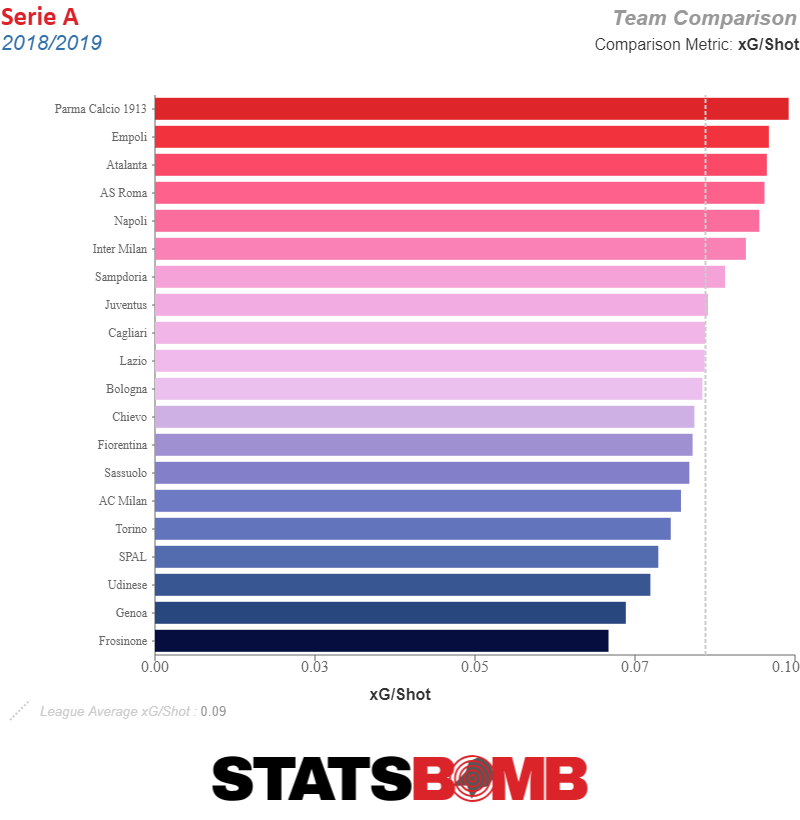

A deeper dive tells a similar story. Atalanta’s expected goal difference of 0.61 per match is bettered only by Juventus and Napoli, the two titans of Italian football. Atalanta are a world class attacking team. The sides 57 goals are second best in Serie A and only three behind Juventus for the best mark in the league, this despite having played one fewer match. Their xG scored per match of 1.58 trails only Napoli’s 1.72. They do this while taking 16.54 shots. One of the keys to the team’s success is that they take better shots, on average, than any other top team (there are two more efficient teams, though both of those bottom half of the table teams take very few shots).

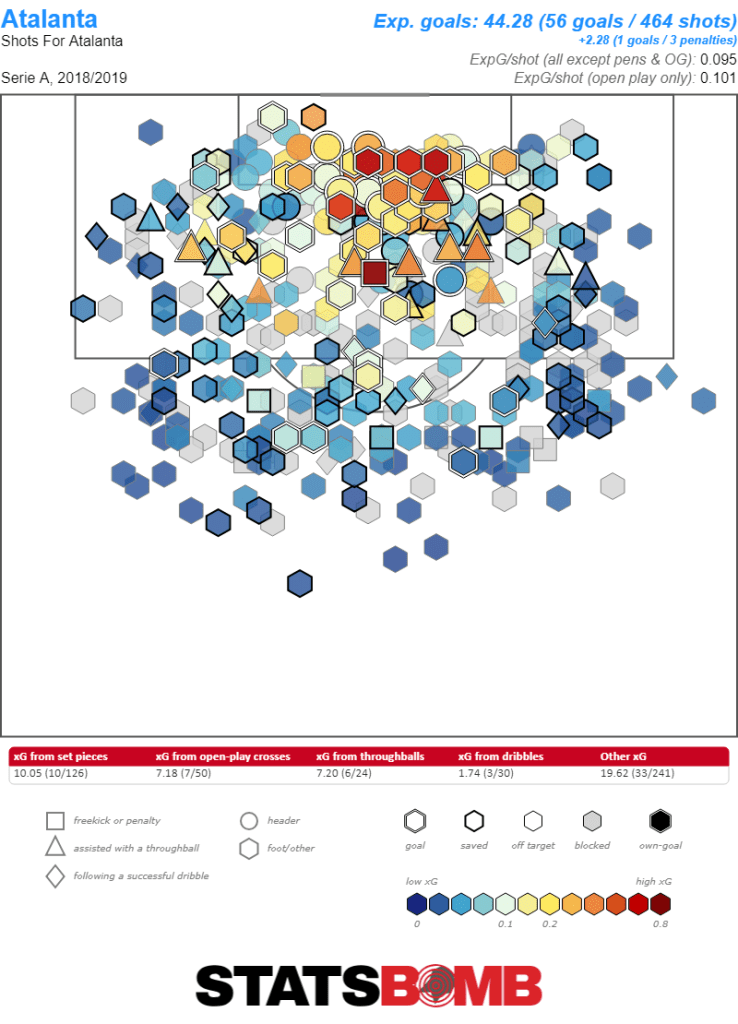

Atalanta’s shot chart makes it crystal clear that they are focused on getting the ball to feet in the most dangerous areas.

There’s nothing particularly complicated about how they approach that task. The team has three very good attacking players, all of whom are skilled at both creating for themselves and for each other. Usually Alejandro Gómez plays behind both Josip Iličić and Duván Zapata. Gómez leads Italy (among players with at least 1000 minutes played) with 0.33 xG assisted per 90 minutes. Zapata is seventh with 0.25 while also being fifth in the league in xG per 90 with 0.42. Iličić trails his strike partner slightly in both categories with 0.23 xG assisted and 0.40 xG.

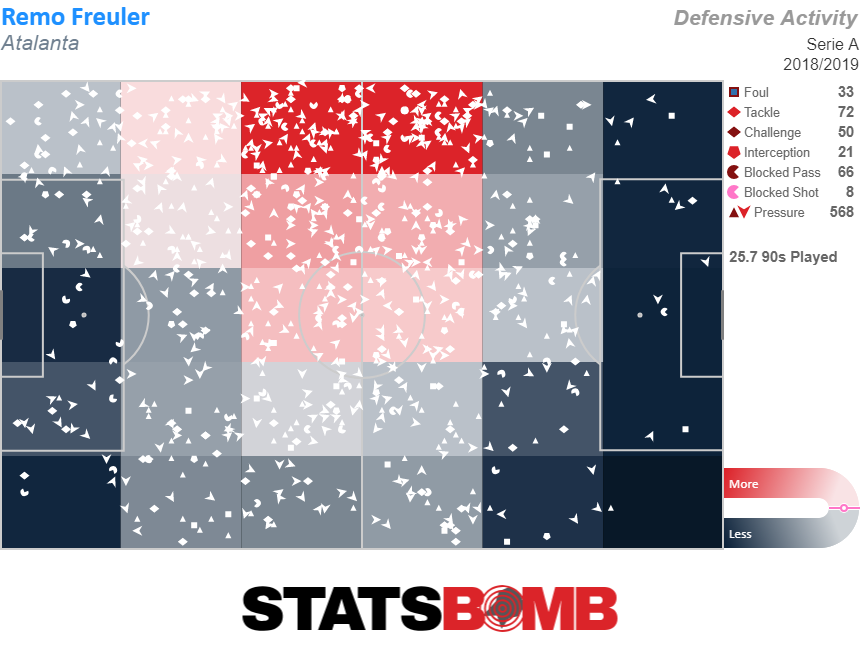

Gómez is also an integral part of how Atalanta moves the ball into the final third. His tendency to drop deeper while Atalanta is in possession means that despite playing a 3-4-3 the side always has bodies in midfield to move the ball forward. He is seventh in Serie A with 9.13 deep progressions per 90, while teammate Remo Freuler, a purer central midfielder, is fifth with 9.43. Freuler is the beating heart of Atalanta’s midfield combining his creative output with a high level of defensive contribution as well. After adjusting for possession he’s ninth in Serie A with 3.67 tackles per 90, and extremely adept at winning the ball when he pressures opponents. His 5.42 pressure regains per 90 are fifth in Serie A. His proficiency covering the left flank means that Atalanta can deploy either Robin Gosens or Timothy Castagne on the wing without fear, despite the fact that left wing back is neither of their natural position.

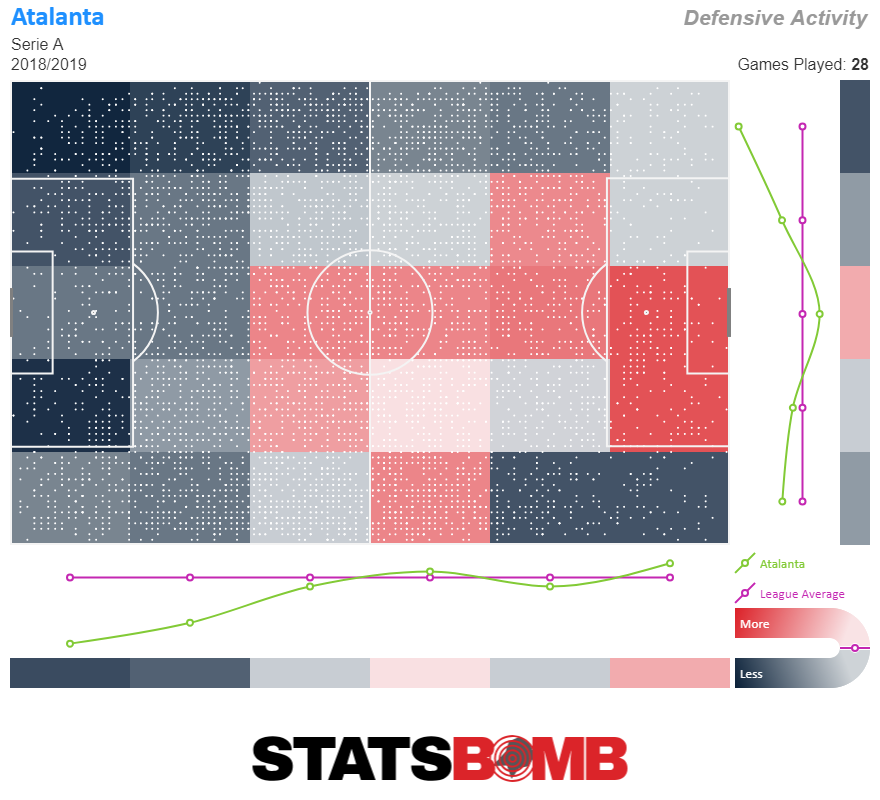

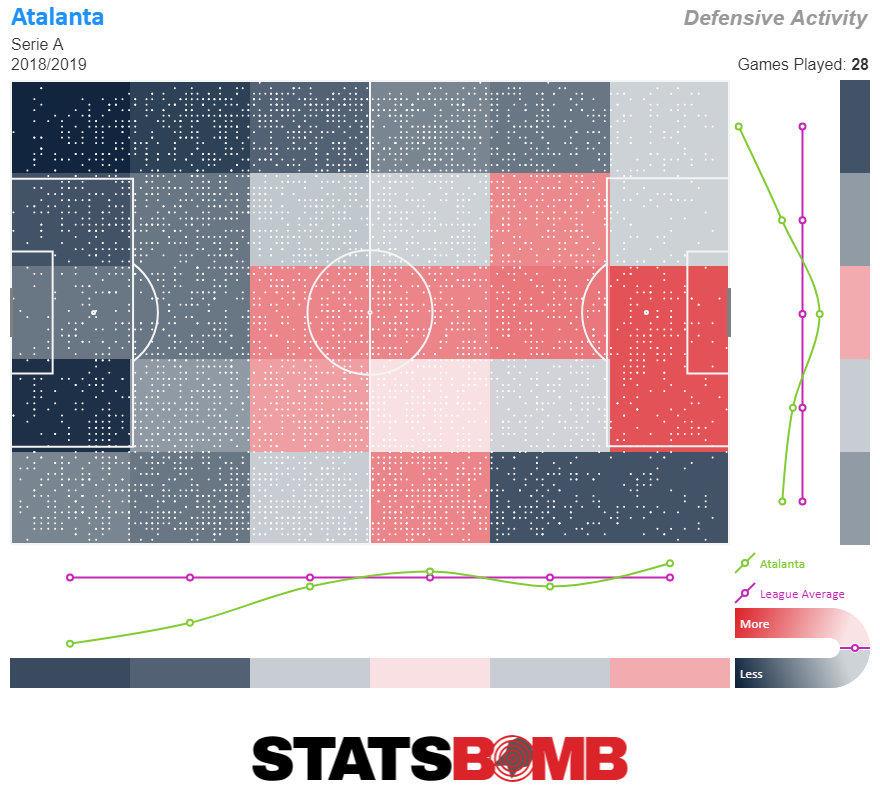

Overall, Atalanta’s defensive numbers are strong, though not as notably excellent as they are on the attacking side. They allow 0.97 xG per match, the fifth best total in the league and they do it primarily by suppressing opponent’s shooting. They allow only, 10.96 shots per match, the fewest in Serie A. Numbers like that suggest a team that press aggressively, and sure enough their defensive activity shows a team that works hard to win the ball back as far up the field as possible.

The topline number of 39 goals conceded is an ugly one, tied for only ninth best in Serie A, but under the hood things are a number of mitigating factors. Seven of those goals are of the flukier variety. They’ve conceded four penalties and put the ball in the back of their own net three additional times. Arguably their high octane, high press style could contribute to a tendency to scramble in their own box when they’re beaten, but in general even for pressing teams, penalties and own goals come and go at the whims of fate.

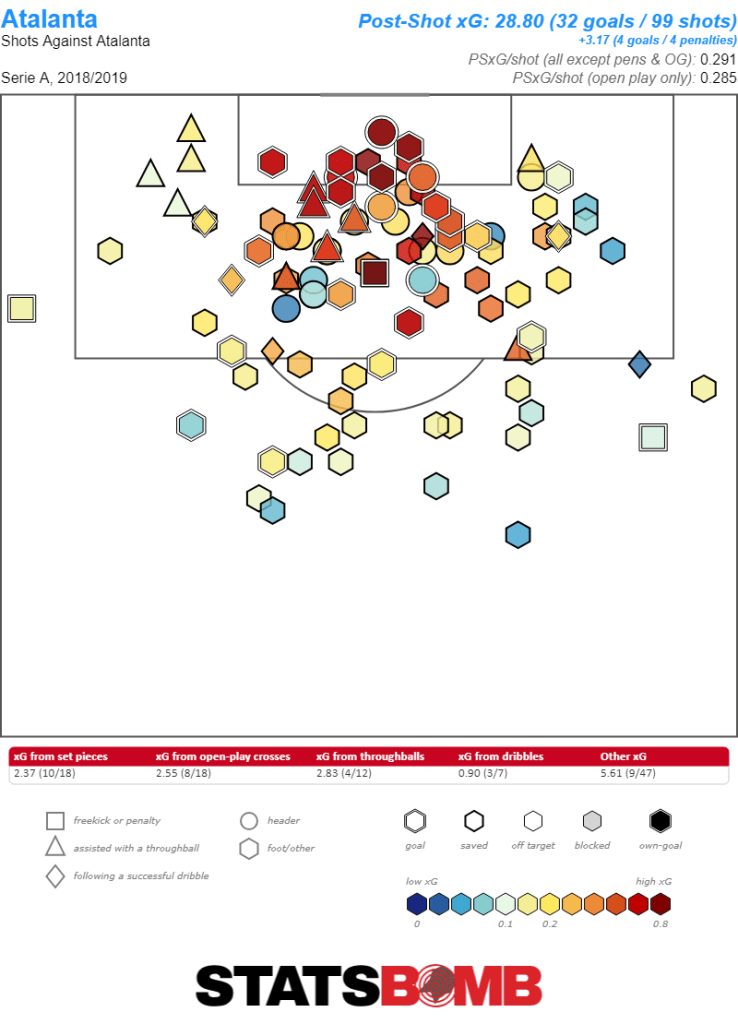

That leaves 32 goals to analyze against an xG of 27.21. That’s certainly the kind of result that could stem from nothing more than bad luck. Looking at post-shot xG tells a similar story. They’ve conceded those 32 goals from a post-shot xG of 28.80.

A slightly better keeping season from the combination of Etrit Berisha and Pierluigi Gollini (both of whom have save percentages below their expected save percentages) and this season might have had a storybook ending. That doesn’t seem likely now. They’re like too far behind, especially with away dates at Inter, Napoli, Lazio and Juventus still left to come. Atalanta are good but they probably aren’t good enough to overcome that.

Atalanta are a fun and exciting squad. They have a superstar attacking unit, a two way midfielder who can do it all and enough supporting pieces to make it all work. Sadly, what they haven’t had over the length of this season is the ability to turn consistently strong performances into enough points to leave them in position to really chase a Champions League spot. Sometimes the good plucky underdog season comes up just short through no fault of its own.

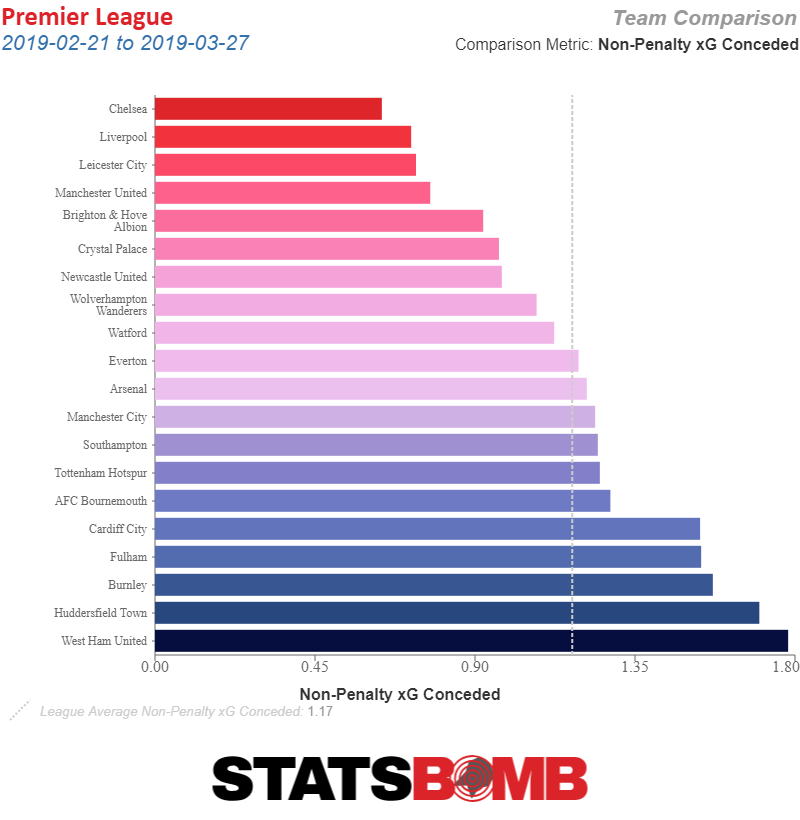

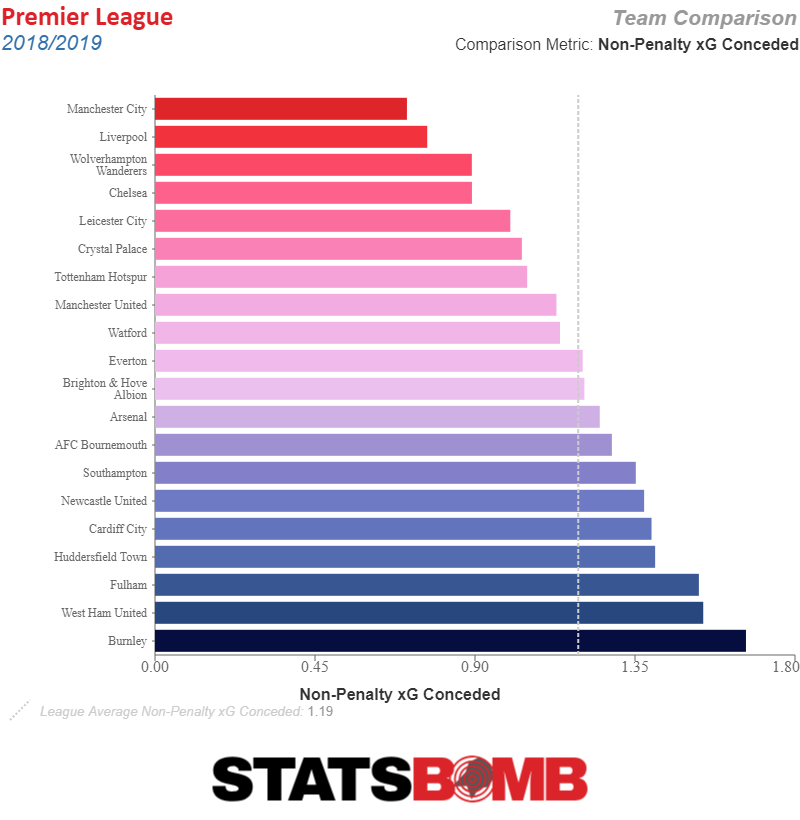

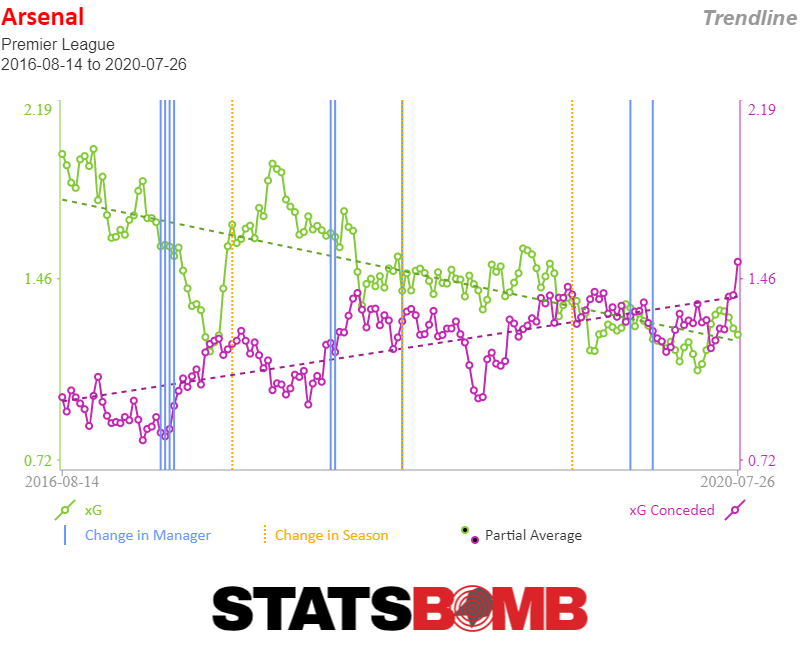

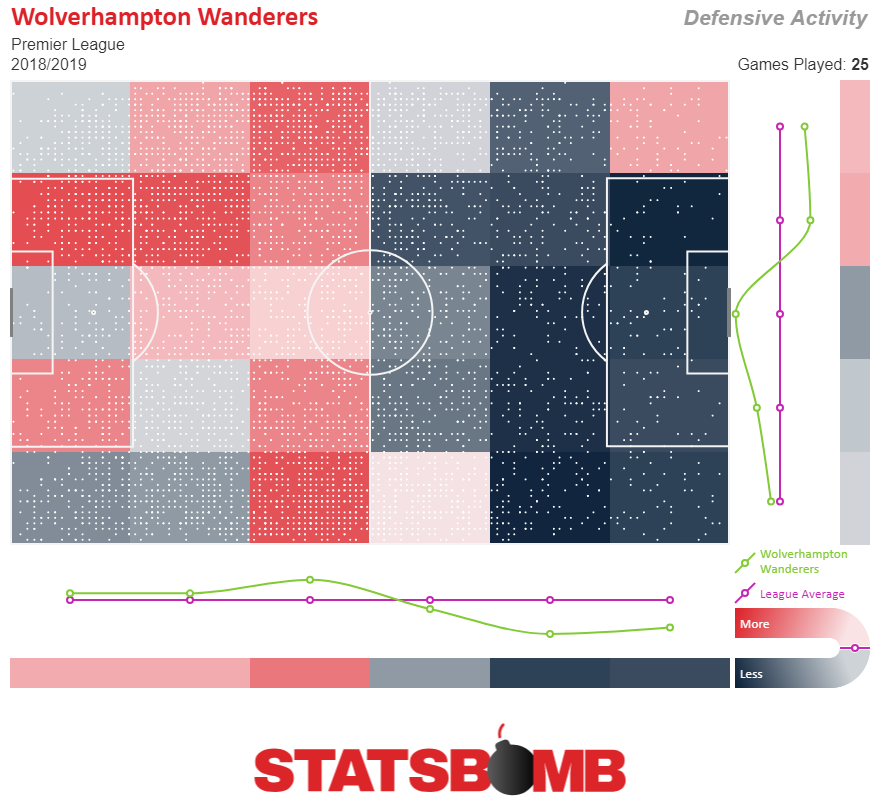

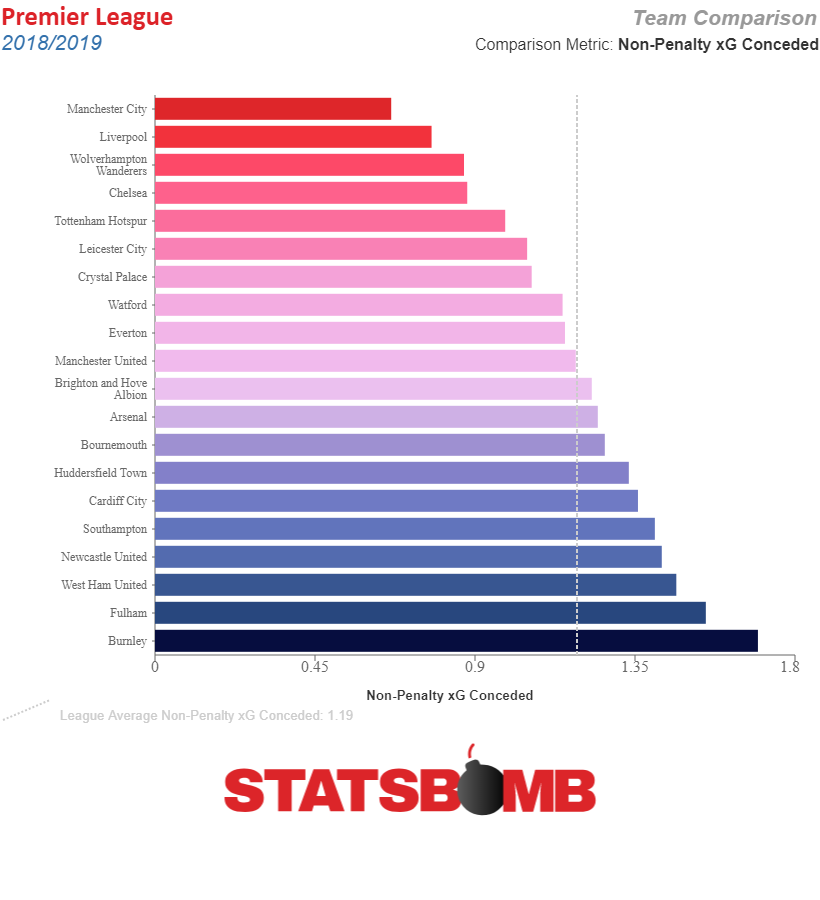

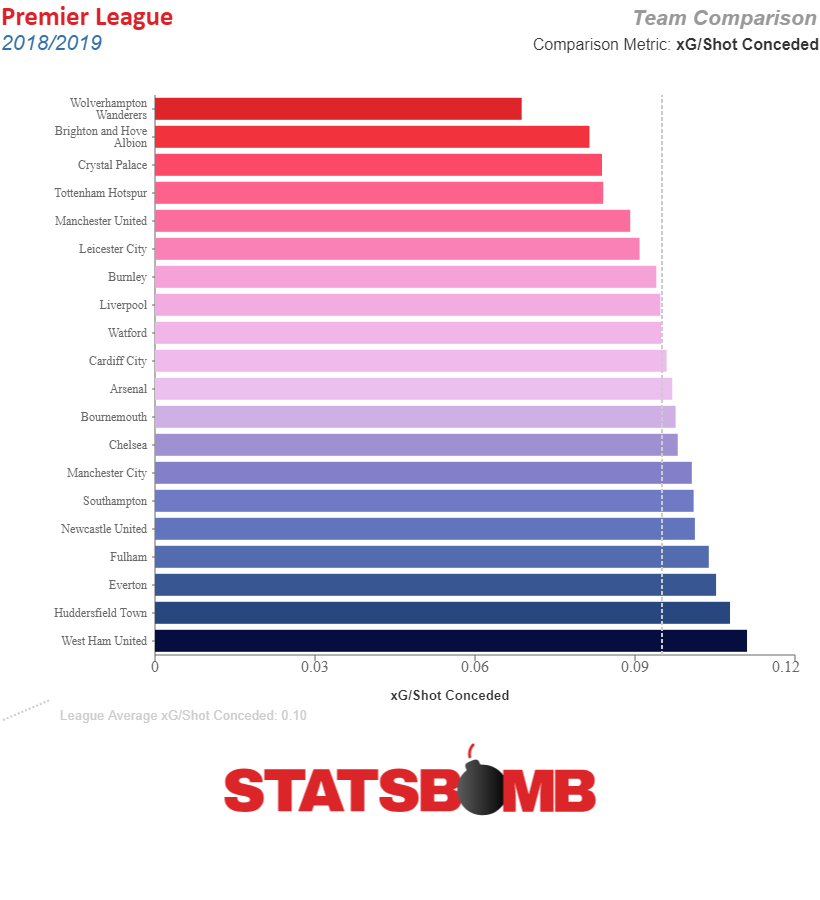

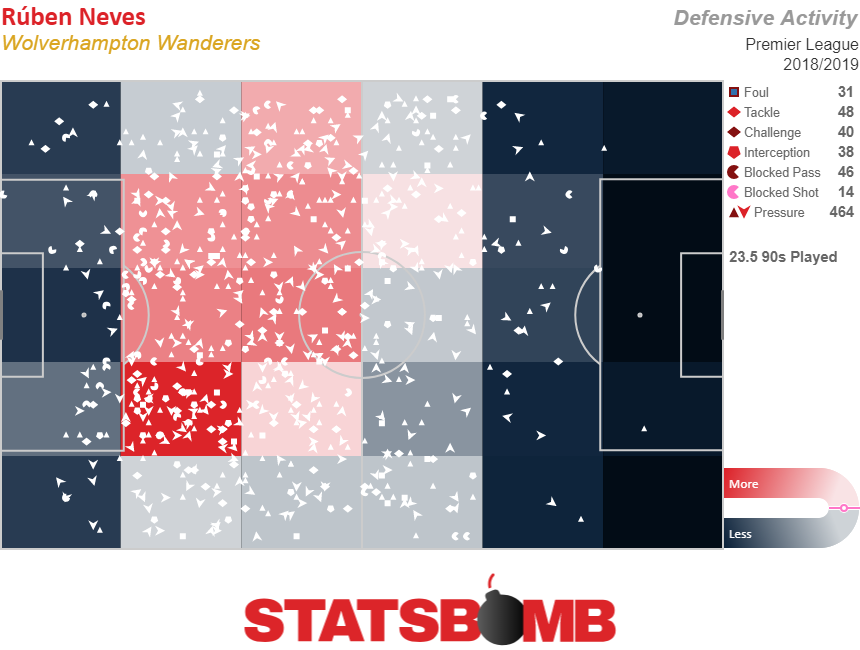

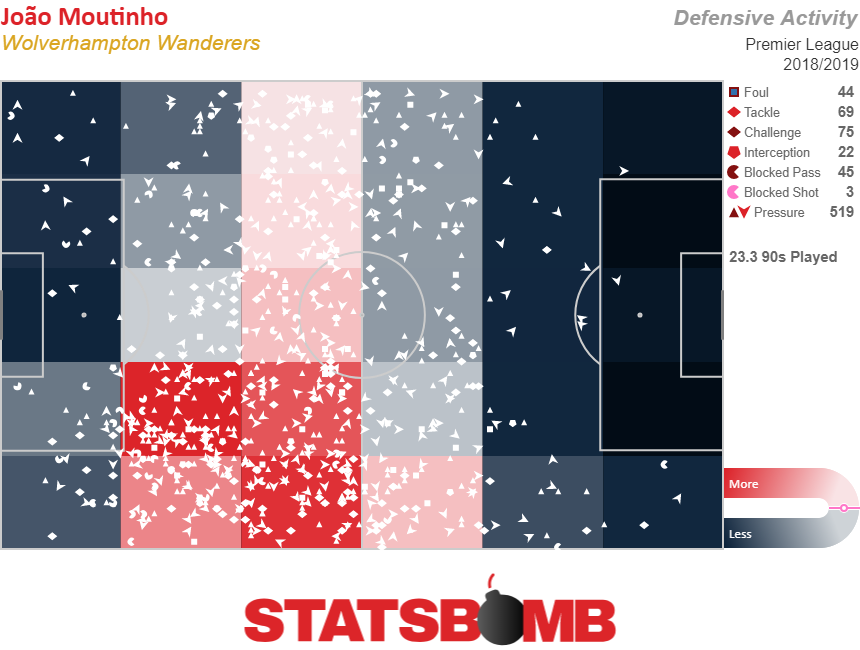

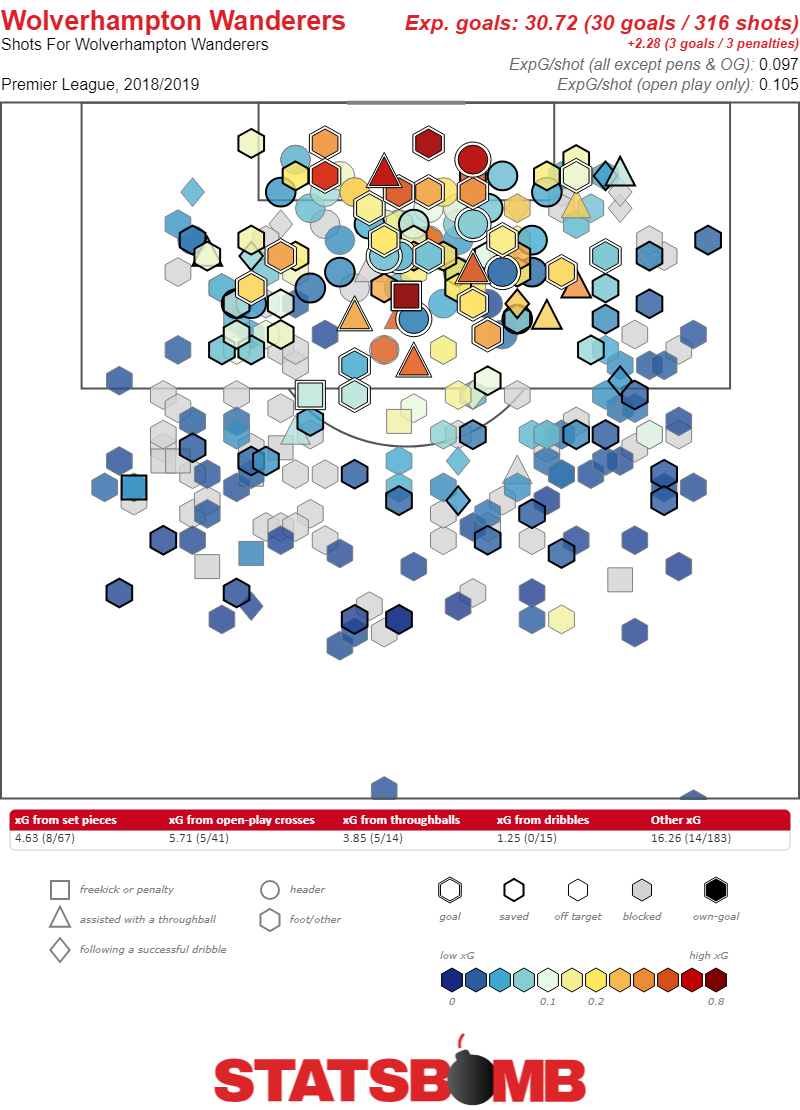

Based on the back of their defensive performance the team actually has (by a narrow margin) the fourth best xG difference in the Premier League. There are reasons to be skeptical of this of course. The story of Manchester United’s season is one of disfunction that likely spilled over into their performance, for example. Arsenal’s defensive numbers have improved over the course of the season in ways that look like they may sustain. The difference between Wolves and Spurs is so small (.03 xG differential per match) that Spurs might pull ahead next week. But still, while the table presents Wolves as clearly the best of the rest, the numbers suggest Wolves might at least be competitive with the top six. The reason that this season has presented that story is that the newly promoted side’s early season results were simply well below their performances.

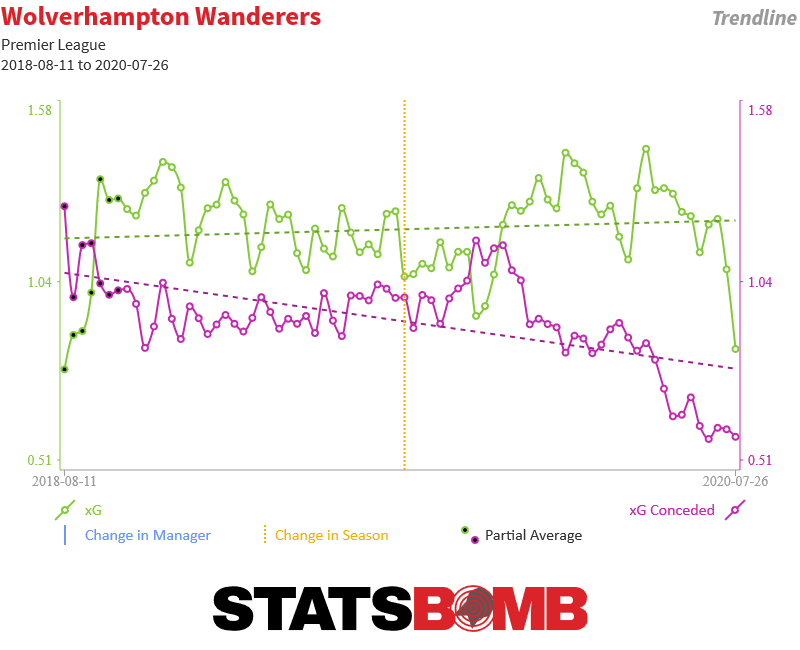

Based on the back of their defensive performance the team actually has (by a narrow margin) the fourth best xG difference in the Premier League. There are reasons to be skeptical of this of course. The story of Manchester United’s season is one of disfunction that likely spilled over into their performance, for example. Arsenal’s defensive numbers have improved over the course of the season in ways that look like they may sustain. The difference between Wolves and Spurs is so small (.03 xG differential per match) that Spurs might pull ahead next week. But still, while the table presents Wolves as clearly the best of the rest, the numbers suggest Wolves might at least be competitive with the top six. The reason that this season has presented that story is that the newly promoted side’s early season results were simply well below their performances.  Flip that season around, put the more fortunate results at the beginning and the tougher bounces at the end and Wolves season would look like a possible miracle in the making, a newly promoted team hanging around the race for the Champions League well past Christmas. So, while it’s reasonable to argue that the numbers overstate Wolves abilities, it’s also quite clear that the table is understating how good they are. As the season winds down it will be worth watching to see if either side of the equation budges. Are Wolves just the best of the rest, or are they building to something more?

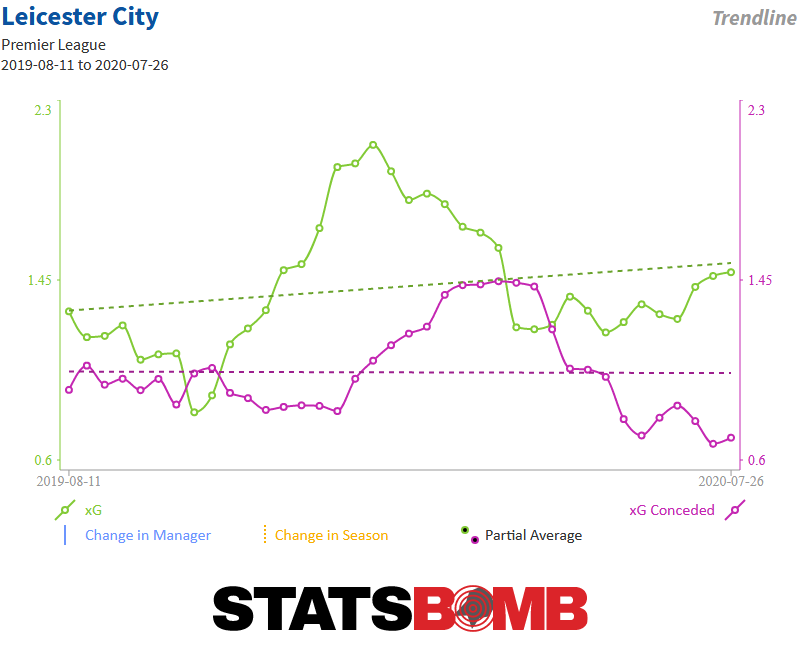

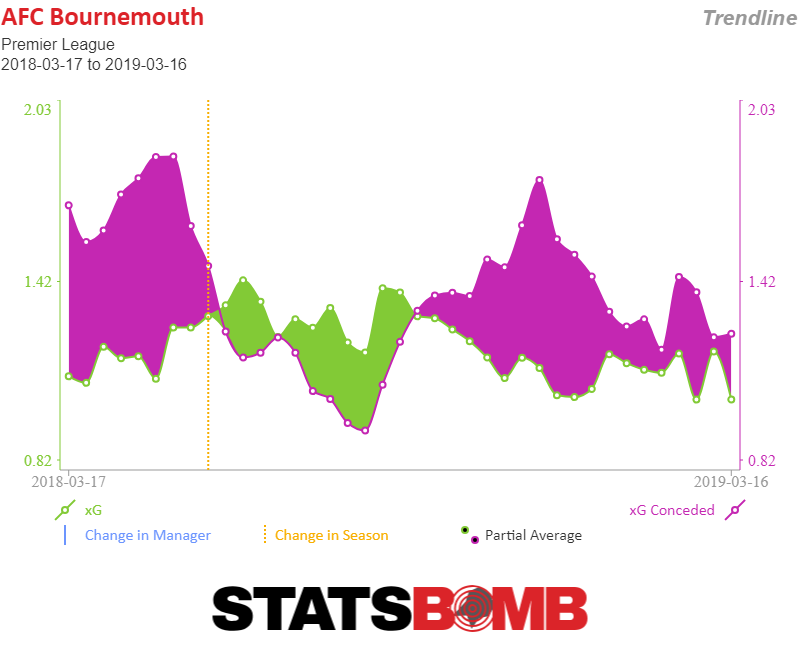

Flip that season around, put the more fortunate results at the beginning and the tougher bounces at the end and Wolves season would look like a possible miracle in the making, a newly promoted team hanging around the race for the Champions League well past Christmas. So, while it’s reasonable to argue that the numbers overstate Wolves abilities, it’s also quite clear that the table is understating how good they are. As the season winds down it will be worth watching to see if either side of the equation budges. Are Wolves just the best of the rest, or are they building to something more?  Starting in January the bottom just fell out of the teams results, even as the performances seemed to indicate that nothing much was wrong. Sometimes that can happen when there are serious problems behind the scenes. Goals and expected goals always converge eventually, but sometimes eventually means after a manager that the players hate gets fired. Other times the manager really has nothing to do with it, and it’s just the fickleness of how the ball bounces that’s messing with the natural order of things. Either way, it seems like a smart time for everybody’s favorite old new manager Brendan Rodgers to step back into the Premier League. He is now at the helm of a team that is due to stop somehow fumbling results that they play well enough to capture. He has experience from way back in his Swansea days taking over a project in midstream. And as long as he doesn’t do anything to drastically mess things up, Leicester City should be just fine. The interesting question to analyze is how much of the team’s expected improvement as the season winds down (and into next year) is actually because Puel did something wrong, something that Rodgers is correcting, and how much is simply that Leicester’s results couldn’t stay that far below expectations forever. What are Bournemouth? After a surprisingly strong start to the season, Eddie Howe’s team have trailed off badly. Neither the beginning of the season nor what came afterwards were particularly a fluke. Their results moved in concert with the levels of their performance (at least until a recent swoon).

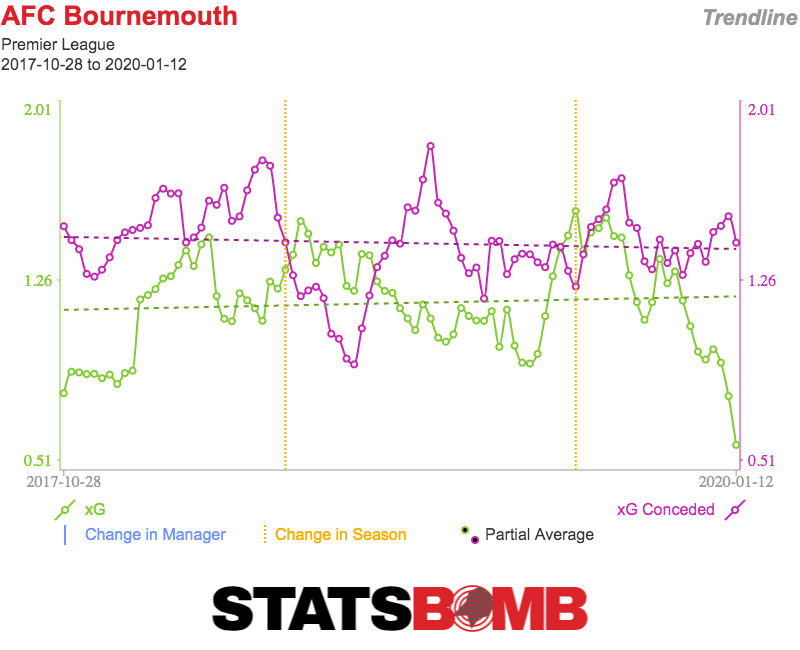

Starting in January the bottom just fell out of the teams results, even as the performances seemed to indicate that nothing much was wrong. Sometimes that can happen when there are serious problems behind the scenes. Goals and expected goals always converge eventually, but sometimes eventually means after a manager that the players hate gets fired. Other times the manager really has nothing to do with it, and it’s just the fickleness of how the ball bounces that’s messing with the natural order of things. Either way, it seems like a smart time for everybody’s favorite old new manager Brendan Rodgers to step back into the Premier League. He is now at the helm of a team that is due to stop somehow fumbling results that they play well enough to capture. He has experience from way back in his Swansea days taking over a project in midstream. And as long as he doesn’t do anything to drastically mess things up, Leicester City should be just fine. The interesting question to analyze is how much of the team’s expected improvement as the season winds down (and into next year) is actually because Puel did something wrong, something that Rodgers is correcting, and how much is simply that Leicester’s results couldn’t stay that far below expectations forever. What are Bournemouth? After a surprisingly strong start to the season, Eddie Howe’s team have trailed off badly. Neither the beginning of the season nor what came afterwards were particularly a fluke. Their results moved in concert with the levels of their performance (at least until a recent swoon).  The culprit seems to have been their defense. After a strong start to the season, Bournemouth’s ability to prevent other teams from getting shots against them has deteriorated dramatically.

The culprit seems to have been their defense. After a strong start to the season, Bournemouth’s ability to prevent other teams from getting shots against them has deteriorated dramatically.  There are several possible explanations for this. Bournemouth have had a rash of injuries up and down the squad including to Callum Wilson and David Brooks, two of their three most important attacking players. They also started with an easy stretch of schedule which may have juiced their numbers only for the cold hard light of more difficult matches to bring them back to earth. The good news for Howe and his team is that if their inconsistency has been schedule driven, then success may once again be just around the corner. The Cherries have seven matches and remaining, but only one against a top six opponent, a home match against Spurs. They also have three matches against relegation candidates, hosting both Fulham and Burnley, and traveling away to Southampton. Trips to Leicester, Brighton and Crystal Palace make up the balance. A strong close might suggest that the early days of the season weren’t a mirage, but rather a real step forward which injuries eventually derailed, albeit one that was turbocharged by the schedule. However, if Bournemouth continue to struggle right up until the closing bell, well that would end up looking more like a team that’s nothing more than a bottom half side that benefitted from the mirage of a soft opening schedule. Bournemouth may not have anything concrete left to play for besides pride, but there last seven performances will go a long way towards demonstrating where next year’s expectation levels should start. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

There are several possible explanations for this. Bournemouth have had a rash of injuries up and down the squad including to Callum Wilson and David Brooks, two of their three most important attacking players. They also started with an easy stretch of schedule which may have juiced their numbers only for the cold hard light of more difficult matches to bring them back to earth. The good news for Howe and his team is that if their inconsistency has been schedule driven, then success may once again be just around the corner. The Cherries have seven matches and remaining, but only one against a top six opponent, a home match against Spurs. They also have three matches against relegation candidates, hosting both Fulham and Burnley, and traveling away to Southampton. Trips to Leicester, Brighton and Crystal Palace make up the balance. A strong close might suggest that the early days of the season weren’t a mirage, but rather a real step forward which injuries eventually derailed, albeit one that was turbocharged by the schedule. However, if Bournemouth continue to struggle right up until the closing bell, well that would end up looking more like a team that’s nothing more than a bottom half side that benefitted from the mirage of a soft opening schedule. Bournemouth may not have anything concrete left to play for besides pride, but there last seven performances will go a long way towards demonstrating where next year’s expectation levels should start. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

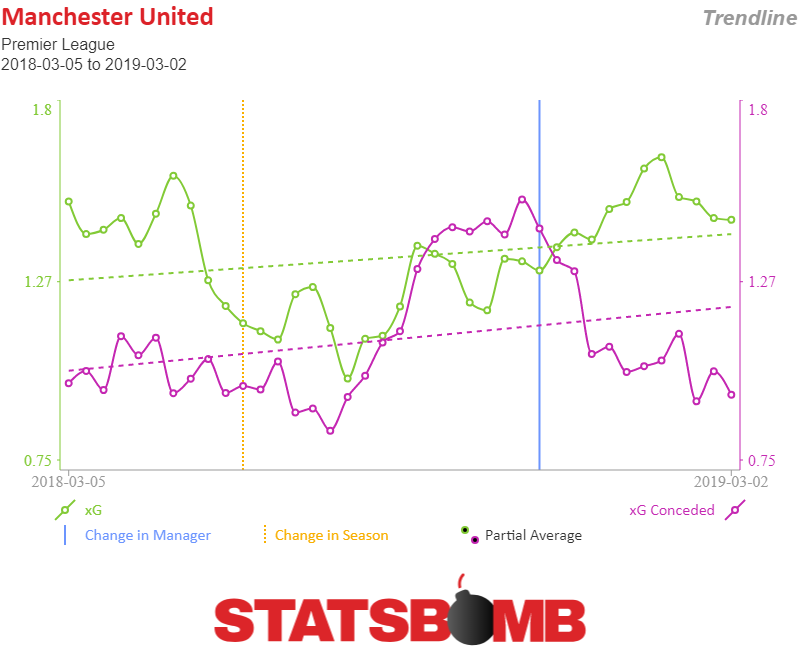

Since Solskjær came to town, the team is fourth in the Premier League in expected goals per match with 1.48 per match, and third in shots with 14.42. Under Mourinho they were sixth with 1.30 and fifth with 13.62. On the defensive side of the ball they went from seventh with 1.11 xG per match conceded and ninth with 12.54 shots conceded to fourth with 0.92 and seventh with 11.58. Those are legitimate steps in the right direction. On top of the improvement in their underlying numbers, they’ve also improved beyond them. This is the shot map of a team that’s running very very hot.

Since Solskjær came to town, the team is fourth in the Premier League in expected goals per match with 1.48 per match, and third in shots with 14.42. Under Mourinho they were sixth with 1.30 and fifth with 13.62. On the defensive side of the ball they went from seventh with 1.11 xG per match conceded and ninth with 12.54 shots conceded to fourth with 0.92 and seventh with 11.58. Those are legitimate steps in the right direction. On top of the improvement in their underlying numbers, they’ve also improved beyond them. This is the shot map of a team that’s running very very hot.  And a defense that is similarly playing above its head.

And a defense that is similarly playing above its head.  There’s nothing particularly ambiguous about what’s going on with United. They have both improved and gone on a hot streak at the same time. And here it’s important to talk about what exactly it means to get hot. From an xG perspective it simply means whatever is causing the team to score more and concede less is not accounted for in the model. Because the model works, and we know that teams over time largely converge to where the xG model predicts they will be, whatever is causing United’s hot run of form, is likely to be temporary, even as the underlying improvement proves more durable. The next question, at least as it relates to Solskjær, is how much of the temporary stuff that the team is riding is he responsible for, and how much truly is just the soccer gods. Some stuff is clearly out of his control. The fact that a referee awarded a marginal handball decision to keep United alive in the Champions League on a Wednesday night in Paris doesn’t make him a better manager. Similarly, if the ref hadn’t awarded the penalty it doesn’t make him worse. Some things, even things that massive results hinge on, are truly out of a manager’s hands. Other things are harder to judge. There’s the so-called new manager bump. It’s easy to understand how a team might respond positively to a new manager, especially after a contentious end to an old regime. Sometimes those changes are easily reflected in xG. And United’s xG has improved. To boil it down to its simplest terms. Mourinho had benched Paul Pogba. Then Mourinho got fired and Paul Pogba started playing again (and in a more free role than he ever had under the Portuguese manager) and voila, improvement. A new manager bump explained, and completely under the auspices of improvements in xG. Of course, there could be more than that going on. Maybe the sense of comradery and common purpose around the team contributed to the backup midfielders being more ready to play than one might expect on Wednesday (though conversely you might also have to wonder about the rash of injuries that led to having to play a backup midfield and what role the new manager has in causing that). Maybe there really just is a sense of magic around the squad generated by a club legend walking in and giving them free rein to play how they want to play. The beauty of methodology like xG is that you don’t have to deny that those things exist. You just have to properly situate them and understand that in the grand scheme of things they are fleeting. Which, when you think about something like a “new manager bounce,” is obvious. The whole idea of a new manager bounce is that it’s a temporary uptick in form brought about by the new voice, that fades as the new manager becomes, simply, the manager. There is tremendous amount of room for debate about why things happen in football. Nobody knows better than people immersed in analytics how truly long the long run is, and how frequently the results of a team can diverge from their underlying numbers, and for how long those divergences can persist. As the old saying goes, the market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent. And Leicester City won a Premier League title. What does that ultimately mean for United? Well, the questions surrounding them right now are interesting. How much of what’s going on right now should be laid at the feet of the manager and how much of it is simply proverbial VAR calls that he has no power to influence going the right way for this squad over and over again? What analytics adds to the table is a hard boundary on those questions. Whatever the answer, even if lots of it is down to Solskjær, it won’t continue forever. Whether it’s tomorrow, next month, or next season, the ball is going to stop flying into the top corner for United, all the penalty calls will stop going their way, and their performances will drift back to what their numbers suggest they should be. The good news is that those numbers are better than they used to be. That bad news is that those numbers suggest worse results than those that have been rolling in under Solskjær so far. Ultimately that discussion is relatively unimportant for the rest of this season. Solskjær is the manager. After seeming adrift of the top four, the team is in the thick of the race for the Champions League spots, and now, they’re in the quarterfinal of the Champions League itself. But, come this summer, when this year’s race is run, the cold reality of the numbers will again come to the fore. Manchester United will have to decide whether Solskjær deserves the job permanently. And if analytics tell us anything, it’s at that point, the numbers contain more information about what the future holds than the results do. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

There’s nothing particularly ambiguous about what’s going on with United. They have both improved and gone on a hot streak at the same time. And here it’s important to talk about what exactly it means to get hot. From an xG perspective it simply means whatever is causing the team to score more and concede less is not accounted for in the model. Because the model works, and we know that teams over time largely converge to where the xG model predicts they will be, whatever is causing United’s hot run of form, is likely to be temporary, even as the underlying improvement proves more durable. The next question, at least as it relates to Solskjær, is how much of the temporary stuff that the team is riding is he responsible for, and how much truly is just the soccer gods. Some stuff is clearly out of his control. The fact that a referee awarded a marginal handball decision to keep United alive in the Champions League on a Wednesday night in Paris doesn’t make him a better manager. Similarly, if the ref hadn’t awarded the penalty it doesn’t make him worse. Some things, even things that massive results hinge on, are truly out of a manager’s hands. Other things are harder to judge. There’s the so-called new manager bump. It’s easy to understand how a team might respond positively to a new manager, especially after a contentious end to an old regime. Sometimes those changes are easily reflected in xG. And United’s xG has improved. To boil it down to its simplest terms. Mourinho had benched Paul Pogba. Then Mourinho got fired and Paul Pogba started playing again (and in a more free role than he ever had under the Portuguese manager) and voila, improvement. A new manager bump explained, and completely under the auspices of improvements in xG. Of course, there could be more than that going on. Maybe the sense of comradery and common purpose around the team contributed to the backup midfielders being more ready to play than one might expect on Wednesday (though conversely you might also have to wonder about the rash of injuries that led to having to play a backup midfield and what role the new manager has in causing that). Maybe there really just is a sense of magic around the squad generated by a club legend walking in and giving them free rein to play how they want to play. The beauty of methodology like xG is that you don’t have to deny that those things exist. You just have to properly situate them and understand that in the grand scheme of things they are fleeting. Which, when you think about something like a “new manager bounce,” is obvious. The whole idea of a new manager bounce is that it’s a temporary uptick in form brought about by the new voice, that fades as the new manager becomes, simply, the manager. There is tremendous amount of room for debate about why things happen in football. Nobody knows better than people immersed in analytics how truly long the long run is, and how frequently the results of a team can diverge from their underlying numbers, and for how long those divergences can persist. As the old saying goes, the market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent. And Leicester City won a Premier League title. What does that ultimately mean for United? Well, the questions surrounding them right now are interesting. How much of what’s going on right now should be laid at the feet of the manager and how much of it is simply proverbial VAR calls that he has no power to influence going the right way for this squad over and over again? What analytics adds to the table is a hard boundary on those questions. Whatever the answer, even if lots of it is down to Solskjær, it won’t continue forever. Whether it’s tomorrow, next month, or next season, the ball is going to stop flying into the top corner for United, all the penalty calls will stop going their way, and their performances will drift back to what their numbers suggest they should be. The good news is that those numbers are better than they used to be. That bad news is that those numbers suggest worse results than those that have been rolling in under Solskjær so far. Ultimately that discussion is relatively unimportant for the rest of this season. Solskjær is the manager. After seeming adrift of the top four, the team is in the thick of the race for the Champions League spots, and now, they’re in the quarterfinal of the Champions League itself. But, come this summer, when this year’s race is run, the cold reality of the numbers will again come to the fore. Manchester United will have to decide whether Solskjær deserves the job permanently. And if analytics tell us anything, it’s at that point, the numbers contain more information about what the future holds than the results do. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

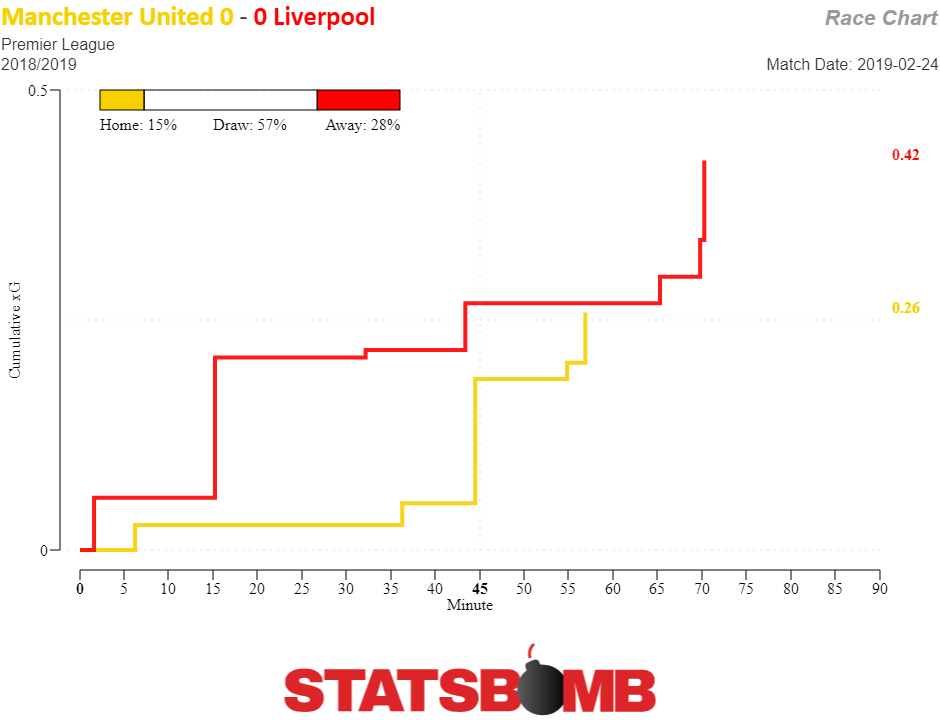

Injuries, of course, play a large story. United were forced into three first half injury substitutions, with Ander Herera, Juan Mata, and Jesse Lingard (Mata’s replacement) all forced off the field. That left the side unable to rescue Marcus Rashford from his own ankle knock. Rashford spent the bulk of the last hour of the match hobbling around at striker unable to contribute much beyond occasional grimacing link up play to United. Liverpool meanwhile lost Roberto Firmino the creative fulcrum around whom Liverpool frequently pivot between their two preferred formations. Taking all those injuries into account, it’s still eye opening that Liverpool was not able to create more against this depleted United side. United’s resurgence has been built on a more open attack featuring which has unleased Paul Pogba and freed players like Rashford, Lingard, and the also injured Anthony Martial to focus on their attacking responsibilities while trusting themselves to score enough to cover for the defense frailties they might leave exposed behind them. And here they are against Liverpool, even a Liverpool side without Firmino, stand firm and conceding nothing. What to make of that? Apportioning credit and assigning blame after a match like this is a bit like one of those logic problems where you have to figure out if a coin is slightly heavier or slightly lighter than the rest of the bunch. Was the story of this match that Liverpool played badly, thus creating the illusion of a strong United defense, or does United really have some surprising steel under the surface which Liverpool unsuspectingly ran headlong into. Or, as it usually is, is the truth somewhere in the middle. There’s also the challenge of negotiating the difference between these two team’s performance in a single match, and what it means for the rest of the season. It’s possible, for example, that United really did put in a spectacular defensive performance, even while still being only a mediocre defensive team. Alternatively, even if all that happened at Old Trafford was that Liverpool played poorly and Mohammed Salah was off his game, that doesn’t mean that Liverpool are destined to all of a sudden become an attacking struggler. Sometimes even the most potent attacks have off days. And, sure enough, soon after the match Liverpool returned to their high-octane attacking ways and thumped Watford at Anfield 5-0. That is, for comparison’s sake, a Watford side that is roughly equivalent to United in terms of expected goals allowed.

Injuries, of course, play a large story. United were forced into three first half injury substitutions, with Ander Herera, Juan Mata, and Jesse Lingard (Mata’s replacement) all forced off the field. That left the side unable to rescue Marcus Rashford from his own ankle knock. Rashford spent the bulk of the last hour of the match hobbling around at striker unable to contribute much beyond occasional grimacing link up play to United. Liverpool meanwhile lost Roberto Firmino the creative fulcrum around whom Liverpool frequently pivot between their two preferred formations. Taking all those injuries into account, it’s still eye opening that Liverpool was not able to create more against this depleted United side. United’s resurgence has been built on a more open attack featuring which has unleased Paul Pogba and freed players like Rashford, Lingard, and the also injured Anthony Martial to focus on their attacking responsibilities while trusting themselves to score enough to cover for the defense frailties they might leave exposed behind them. And here they are against Liverpool, even a Liverpool side without Firmino, stand firm and conceding nothing. What to make of that? Apportioning credit and assigning blame after a match like this is a bit like one of those logic problems where you have to figure out if a coin is slightly heavier or slightly lighter than the rest of the bunch. Was the story of this match that Liverpool played badly, thus creating the illusion of a strong United defense, or does United really have some surprising steel under the surface which Liverpool unsuspectingly ran headlong into. Or, as it usually is, is the truth somewhere in the middle. There’s also the challenge of negotiating the difference between these two team’s performance in a single match, and what it means for the rest of the season. It’s possible, for example, that United really did put in a spectacular defensive performance, even while still being only a mediocre defensive team. Alternatively, even if all that happened at Old Trafford was that Liverpool played poorly and Mohammed Salah was off his game, that doesn’t mean that Liverpool are destined to all of a sudden become an attacking struggler. Sometimes even the most potent attacks have off days. And, sure enough, soon after the match Liverpool returned to their high-octane attacking ways and thumped Watford at Anfield 5-0. That is, for comparison’s sake, a Watford side that is roughly equivalent to United in terms of expected goals allowed.  And United also reverted to form, although their form is a little harder to parse. They comfortably handled Crystal Palace, going to Selhurst Park and winning 3-1. They also gave up 17 shots in the process and despite spending most of the game with the result never truly looking in doubt, managed to be unconvincing in defense while also scoring a bunch. The earliest of early returns suggest that whatever happened between Liverpool and United at won’t actually have outsized impact on how the two teams continue to play as the season winds down. Figuring out if the coin was slightly heavier or slightly lighter at Old Trafford is an interesting and worthwhile endeavor for understanding the match, but it’s possible that it’s also one that won’t shed much light on the futures of the two teams involved. Narrowly this makes sense. Liverpool might not have been prepared to deal with losing Firmino in the moment, and his replacement, Daniel Sturridge remained largely invisible after coming on. But, given even half a week to prepare, instead of deploying Sturridge, they shifted Sadio Mane up top and started Divock Origi on the left. Meanwhile, United, outside of the context of being injured beyond belief and trying to defend and survive against a great Liverpool side, went back to their swashbuckling, if slightly vulnerable ways. Broadly this makes sense too. The search to find meaning in the Premier League’s marquee matchups is understandable but often flawed. The biggest matches of the season are often defined by two teams wrestling imperfectly to stamp their influence on a match. Results are frequently defined by which teams gets to play their preferred strategy and which team is forced to adjust. Who wins those encounters matters to an outsized degree, because in a closely contested league, every point counts, giving added importance to those moments when a squad gets to both gather points for themselves while also denying their rivals an opportunity to do the same. But, at the same time, those matches are often not the best indicators of how good a team is. The individual factors at play in an individual match between two heavyweights are often outweighed over the course of a season by how teams play against everybody else. Liverpool’s attack is great because it brings the pain week in and week out. The stutter against United isn’t bad luck, but it’s also not more important than everything else we’ve seen. The same is true of United’s defense. The concerns remain despite the performance against Liverpool. Any time Liverpool go to Old Trafford it’s a massive match. The points won and lost will frequently be consequential in the standings at the lofty end of the table. It’s important to understand why and how those games end the way they do. It’s also important to understand the limits of what they can tell us about the two teams competing in those matches. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

And United also reverted to form, although their form is a little harder to parse. They comfortably handled Crystal Palace, going to Selhurst Park and winning 3-1. They also gave up 17 shots in the process and despite spending most of the game with the result never truly looking in doubt, managed to be unconvincing in defense while also scoring a bunch. The earliest of early returns suggest that whatever happened between Liverpool and United at won’t actually have outsized impact on how the two teams continue to play as the season winds down. Figuring out if the coin was slightly heavier or slightly lighter at Old Trafford is an interesting and worthwhile endeavor for understanding the match, but it’s possible that it’s also one that won’t shed much light on the futures of the two teams involved. Narrowly this makes sense. Liverpool might not have been prepared to deal with losing Firmino in the moment, and his replacement, Daniel Sturridge remained largely invisible after coming on. But, given even half a week to prepare, instead of deploying Sturridge, they shifted Sadio Mane up top and started Divock Origi on the left. Meanwhile, United, outside of the context of being injured beyond belief and trying to defend and survive against a great Liverpool side, went back to their swashbuckling, if slightly vulnerable ways. Broadly this makes sense too. The search to find meaning in the Premier League’s marquee matchups is understandable but often flawed. The biggest matches of the season are often defined by two teams wrestling imperfectly to stamp their influence on a match. Results are frequently defined by which teams gets to play their preferred strategy and which team is forced to adjust. Who wins those encounters matters to an outsized degree, because in a closely contested league, every point counts, giving added importance to those moments when a squad gets to both gather points for themselves while also denying their rivals an opportunity to do the same. But, at the same time, those matches are often not the best indicators of how good a team is. The individual factors at play in an individual match between two heavyweights are often outweighed over the course of a season by how teams play against everybody else. Liverpool’s attack is great because it brings the pain week in and week out. The stutter against United isn’t bad luck, but it’s also not more important than everything else we’ve seen. The same is true of United’s defense. The concerns remain despite the performance against Liverpool. Any time Liverpool go to Old Trafford it’s a massive match. The points won and lost will frequently be consequential in the standings at the lofty end of the table. It’s important to understand why and how those games end the way they do. It’s also important to understand the limits of what they can tell us about the two teams competing in those matches. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

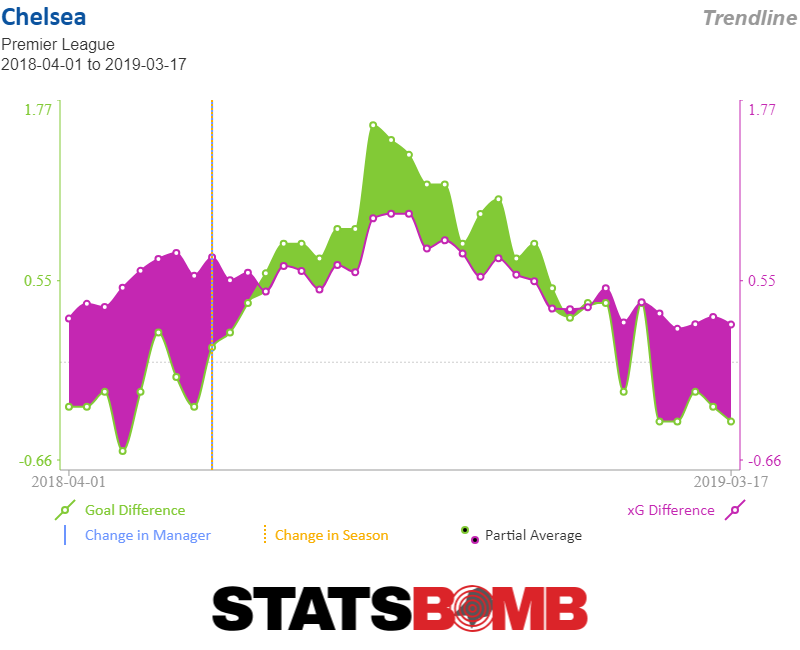

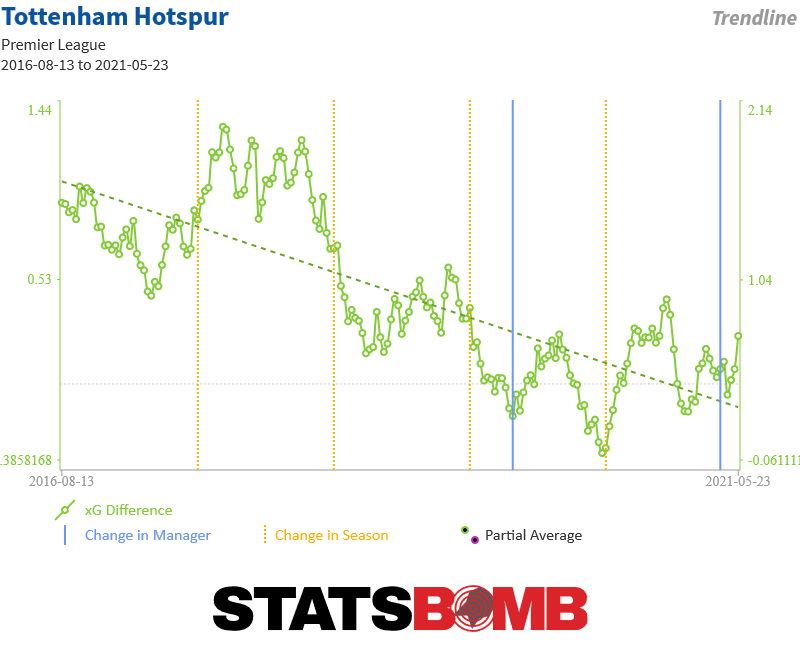

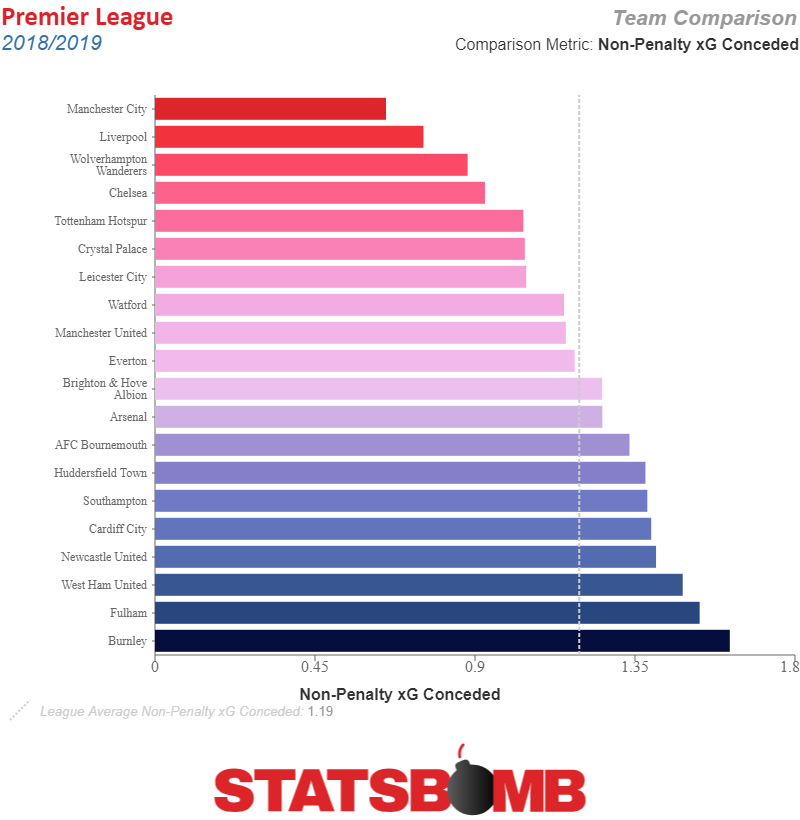

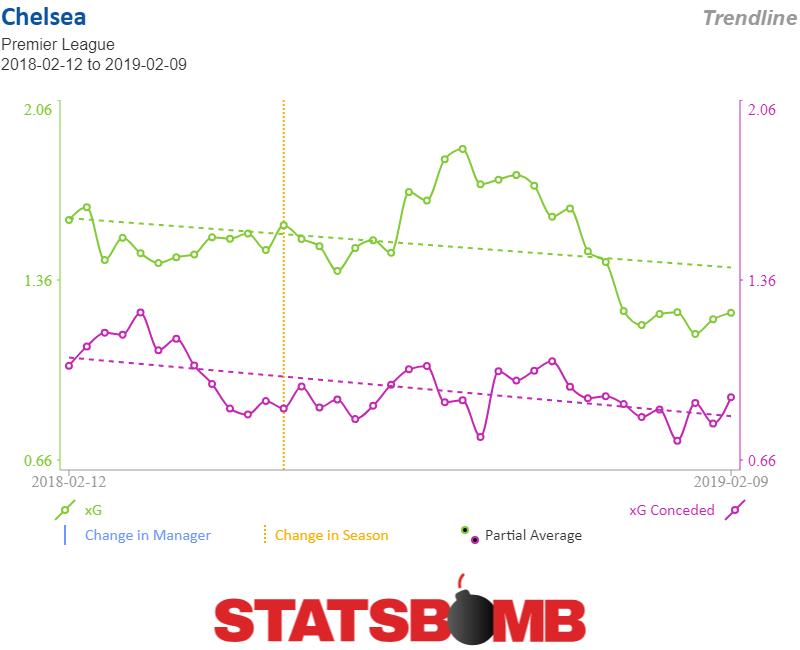

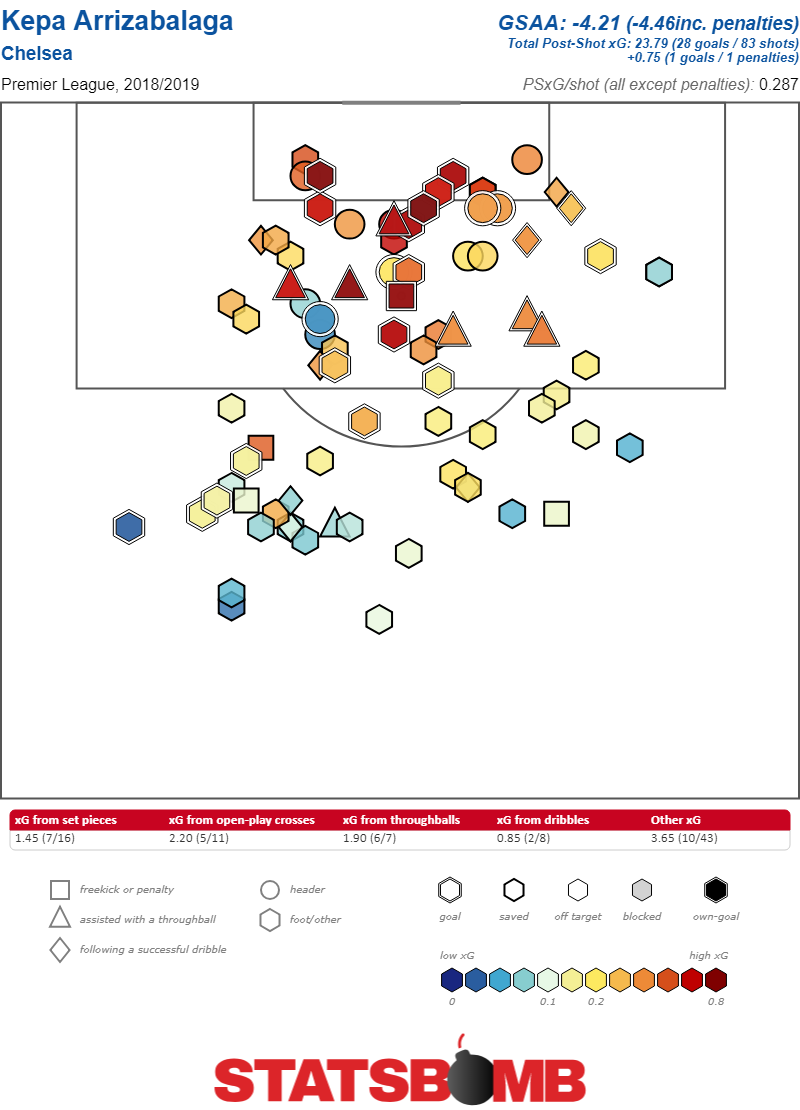

The fact that there has been a noticeable decline in the team complicates most defenses of manager Maurizio Sarri. While it was always reasonable to expect a new manager to take some time to successfully introduce a new style of play, the fact that the team is actually getting worse as the season progresses, does not suggest a side that is slowly being brought along into a new style. This isn’t the story of a team that had some growing pains adapting from Antonio Conte’s primarily off ball approach to Sarri’s possession heavy attempt. It’s rather the story of a side that is not picking up his approach effectively at all. Accordingly, the defense of Sarri has shifted. Now, it’s that the squad is simply poorly constructed for Sarri, and that a club which was built to succeed under Antonio Conte could never become a side capable of playing Sarriball without a complete overhaul first (a task which has incidentally been made harder by a transfer ban handed down by FIFA, although one which could reasonably be delayed by appeal). There are three problems with this defense. The first is historical. Sarri took over Napoli in the summer of 2015. In his first season he finished second in Serie A with 82 points. That was a massive 19-point improvement over the team’s previous fifth place season. And it’s not like he took over from a similar manager. Rafa Benitez had previously been in charge, and while Rafa has many strengths, intricate possession based football is not exactly one of them. So, the last time Sarri took over a club, he took a team that had been struggling, playing a different brand of football and immediately improved them dramatically in his first season. And while it might not have been reasonable to expect the same degree of immediate success in England, expecting demonstrable progress is a pretty low bar. It’s one that Sarri has, so far, failed to clear. But, wait, I hear you cry, didn’t Napoli remake their roster for Sarri when he showed up? The answer to that is… kind of, and it brings us to the second problem with saying that it’s important to wait for Sarri to have his players in place. The current Chelsea squad already looks very very different from the one Conte deployed last season. At Napoli, in Sarri’s first summer, the team moved on from Gokhan Inler in midfield and brought in Allan from Udinese. Quite quickly he became an integral part of Sarri’s midfield. The team also brought in two players from his old club, Empoli; Elseid Hysaj who became a regular at fullback and Mirko Valdifiori a defensive midfielder who you’ve never heard of. Chelsea, similarly did a lot of work to overhaul this squad for Sarri last summer. In order to facilitate moving from a manager who was happy not to have the ball to one who’s possession hungry, Chelsea went out and got a new midfield. They not only bought Sarri Jorginho, the midfield pivot from his old side, but also Mateo Kovačić on loan from Real Madrid. Additionally, after they assented to Thibaut Courtois’ demands to move to Real Madrid, they brought in Kepa Arrizabalaga to replace him, emphasizing the need for a keeper who can play with his feet. One problem though, Kepa has not played particularly well with his hands, and is putting up a decidedly subpar shot stopping season.

The fact that there has been a noticeable decline in the team complicates most defenses of manager Maurizio Sarri. While it was always reasonable to expect a new manager to take some time to successfully introduce a new style of play, the fact that the team is actually getting worse as the season progresses, does not suggest a side that is slowly being brought along into a new style. This isn’t the story of a team that had some growing pains adapting from Antonio Conte’s primarily off ball approach to Sarri’s possession heavy attempt. It’s rather the story of a side that is not picking up his approach effectively at all. Accordingly, the defense of Sarri has shifted. Now, it’s that the squad is simply poorly constructed for Sarri, and that a club which was built to succeed under Antonio Conte could never become a side capable of playing Sarriball without a complete overhaul first (a task which has incidentally been made harder by a transfer ban handed down by FIFA, although one which could reasonably be delayed by appeal). There are three problems with this defense. The first is historical. Sarri took over Napoli in the summer of 2015. In his first season he finished second in Serie A with 82 points. That was a massive 19-point improvement over the team’s previous fifth place season. And it’s not like he took over from a similar manager. Rafa Benitez had previously been in charge, and while Rafa has many strengths, intricate possession based football is not exactly one of them. So, the last time Sarri took over a club, he took a team that had been struggling, playing a different brand of football and immediately improved them dramatically in his first season. And while it might not have been reasonable to expect the same degree of immediate success in England, expecting demonstrable progress is a pretty low bar. It’s one that Sarri has, so far, failed to clear. But, wait, I hear you cry, didn’t Napoli remake their roster for Sarri when he showed up? The answer to that is… kind of, and it brings us to the second problem with saying that it’s important to wait for Sarri to have his players in place. The current Chelsea squad already looks very very different from the one Conte deployed last season. At Napoli, in Sarri’s first summer, the team moved on from Gokhan Inler in midfield and brought in Allan from Udinese. Quite quickly he became an integral part of Sarri’s midfield. The team also brought in two players from his old club, Empoli; Elseid Hysaj who became a regular at fullback and Mirko Valdifiori a defensive midfielder who you’ve never heard of. Chelsea, similarly did a lot of work to overhaul this squad for Sarri last summer. In order to facilitate moving from a manager who was happy not to have the ball to one who’s possession hungry, Chelsea went out and got a new midfield. They not only bought Sarri Jorginho, the midfield pivot from his old side, but also Mateo Kovačić on loan from Real Madrid. Additionally, after they assented to Thibaut Courtois’ demands to move to Real Madrid, they brought in Kepa Arrizabalaga to replace him, emphasizing the need for a keeper who can play with his feet. One problem though, Kepa has not played particularly well with his hands, and is putting up a decidedly subpar shot stopping season.  Then, as Chelsea struggled, the team once again went out and brought in an old Sarri hand, Gonzalo Higuain, to lead the line. Over a third of Chelsea’s regular starting lineup is new this season. The problem is as much that the new players, the ones bought for Sarri, aren’t performing, as much as it is that the old guard are holding the team back. It’s reasonable for a manager to struggle with a squad that doesn’t fit his needs, it’s way less so to claim that completely remaking the midfield and bringing in his old star striker isn’t enough of a makeover to expect results. But maybe that really is the problem. Maybe no matter what Chelsea did, this team could not succeed given how their winger situation is currently constituted. It’s at least worth considering that Pedro and Willian are simply an impossible match for this system. They’re both past 30 and maybe those old dogs simply ain’t about to learn any new tricks. On top of that, maybe Hazard, great as he is, isn’t particularly suited to this system that needs him to play more as a goal scorer than leading the break in transition. Even this isn’t a great defense of Sarri. After all, Sarri keeps playing them. This is the final frustrating point. What would be the point of continuing to play two wingers who are over 30 if they are simply never going to be good enough in the system Sarri wants to play, when you not only have Callum Hudson-Odoi waiting in the wings, but another young replacement in Christian Pulisic coming this summer. Sure, maybe Hudson-Odoi isn’t ready, but in that case, it would make more sense to tweak the system to get the most out of the players on the pitch (in the understanding that they won’t still be there when better fitting players come in). Both playing Willian and Pedro, and not adjusting the system to get the most out of them, while leaving Hudson-Odoi on the bench is the worst of all possible worlds. The question at hand for Chelsea is, should (assuming they can delay a transfer ban via appeal) they continue to remake this squad in Sarri’s image? It’s a big risk to put all your eggs in the Sarri basket, especially with a transfer ban looming. Before committing to that project Chelsea need to take a long hard look at why his transition with this side has been so much rougher than his transition at Napoli was. It’s certainly true that the situation at Chelsea isn’t perfect for Sarri, but the situation at Napoli wasn’t either. There, he made do. Now he’s banging square pegs into round holes, shrugging and saying, I’ll be better when I have some round pegs. It might be true, but other managers out there are better at reshaping those pegs. The situation certainly hasn’t been perfect for Sarri at Chelsea, and maybe if it was we’d see him become a roaring success. But most managers don’t get to deal with perfect situations, and it’s now time to wonder exactly how much imperfect Sarri is capable of dealing with while still getting results. If Sarri can’t point to some sort of progress after replacing a third of his starters with new acquisitions, maybe Chelsea shouldn’t be so confident that he’ll be destined to succeed if they just replace the rest of them. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

Then, as Chelsea struggled, the team once again went out and brought in an old Sarri hand, Gonzalo Higuain, to lead the line. Over a third of Chelsea’s regular starting lineup is new this season. The problem is as much that the new players, the ones bought for Sarri, aren’t performing, as much as it is that the old guard are holding the team back. It’s reasonable for a manager to struggle with a squad that doesn’t fit his needs, it’s way less so to claim that completely remaking the midfield and bringing in his old star striker isn’t enough of a makeover to expect results. But maybe that really is the problem. Maybe no matter what Chelsea did, this team could not succeed given how their winger situation is currently constituted. It’s at least worth considering that Pedro and Willian are simply an impossible match for this system. They’re both past 30 and maybe those old dogs simply ain’t about to learn any new tricks. On top of that, maybe Hazard, great as he is, isn’t particularly suited to this system that needs him to play more as a goal scorer than leading the break in transition. Even this isn’t a great defense of Sarri. After all, Sarri keeps playing them. This is the final frustrating point. What would be the point of continuing to play two wingers who are over 30 if they are simply never going to be good enough in the system Sarri wants to play, when you not only have Callum Hudson-Odoi waiting in the wings, but another young replacement in Christian Pulisic coming this summer. Sure, maybe Hudson-Odoi isn’t ready, but in that case, it would make more sense to tweak the system to get the most out of the players on the pitch (in the understanding that they won’t still be there when better fitting players come in). Both playing Willian and Pedro, and not adjusting the system to get the most out of them, while leaving Hudson-Odoi on the bench is the worst of all possible worlds. The question at hand for Chelsea is, should (assuming they can delay a transfer ban via appeal) they continue to remake this squad in Sarri’s image? It’s a big risk to put all your eggs in the Sarri basket, especially with a transfer ban looming. Before committing to that project Chelsea need to take a long hard look at why his transition with this side has been so much rougher than his transition at Napoli was. It’s certainly true that the situation at Chelsea isn’t perfect for Sarri, but the situation at Napoli wasn’t either. There, he made do. Now he’s banging square pegs into round holes, shrugging and saying, I’ll be better when I have some round pegs. It might be true, but other managers out there are better at reshaping those pegs. The situation certainly hasn’t been perfect for Sarri at Chelsea, and maybe if it was we’d see him become a roaring success. But most managers don’t get to deal with perfect situations, and it’s now time to wonder exactly how much imperfect Sarri is capable of dealing with while still getting results. If Sarri can’t point to some sort of progress after replacing a third of his starters with new acquisitions, maybe Chelsea shouldn’t be so confident that he’ll be destined to succeed if they just replace the rest of them. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

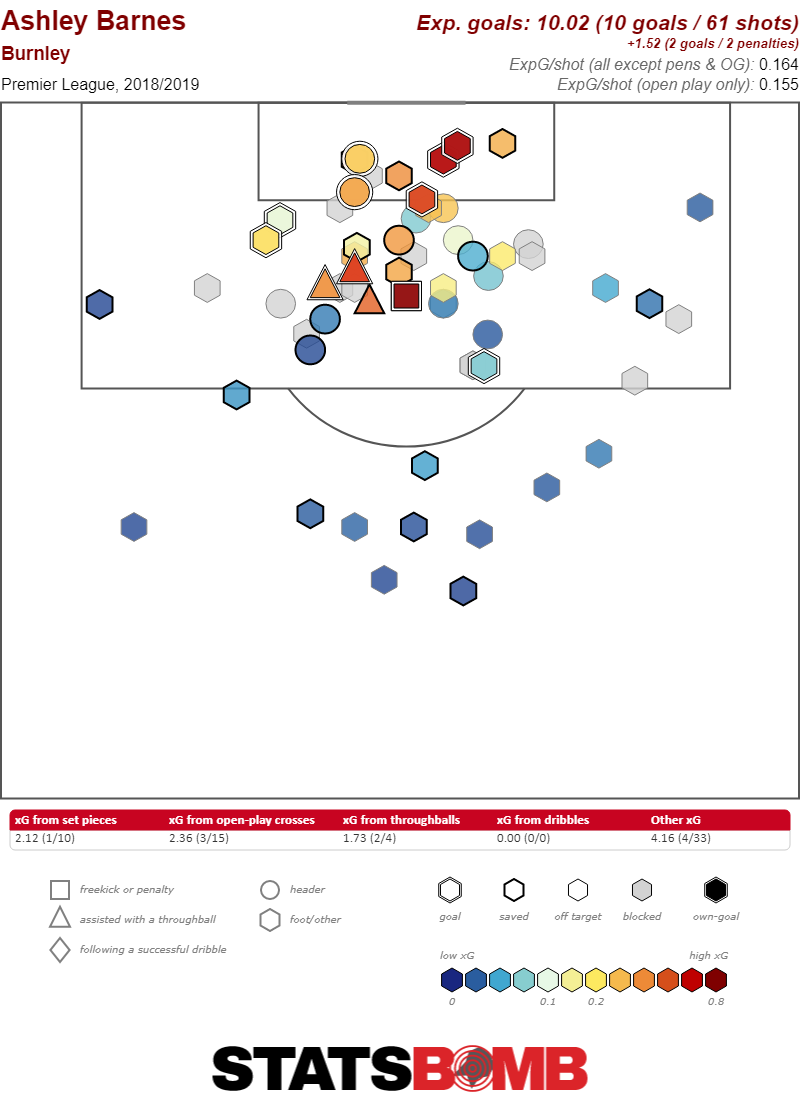

Forward – Ashley Barnes Wait what? Burnley’s Ashley Barnes? Yep. Dude has 0.43 xG per 90 this season. I don’t make the rules. I mean, I did make the rules, like less than 200 words ago, but nevertheless! Ashley Barnes.

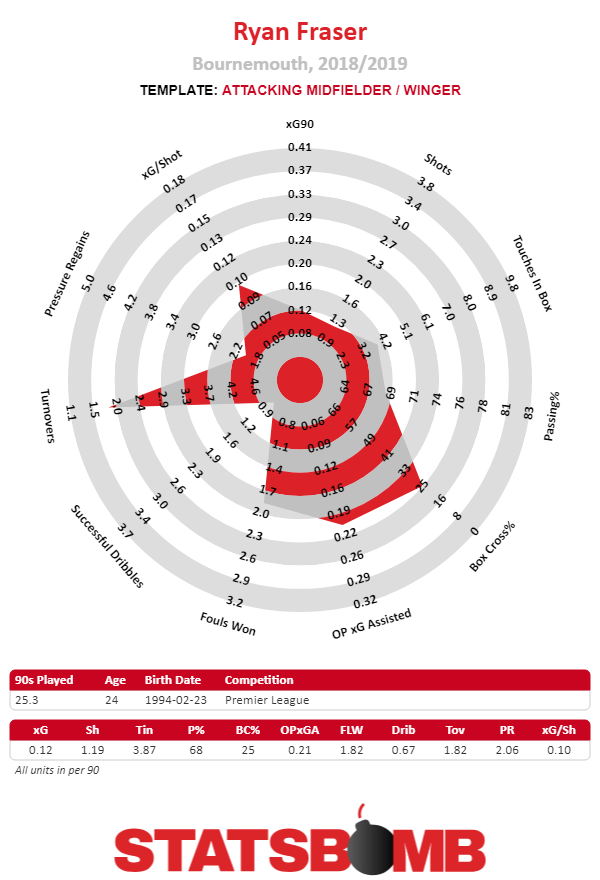

Forward – Ashley Barnes Wait what? Burnley’s Ashley Barnes? Yep. Dude has 0.43 xG per 90 this season. I don’t make the rules. I mean, I did make the rules, like less than 200 words ago, but nevertheless! Ashley Barnes.  Wingers – Felipe Anderson, Ryan Fraser Ryan Fraser is just an absolute assist machine. His 0.26 expected goals assisted is tops outside the top six and eight overall. He doesn’t do a lot of different stuff, but the thing he does do, is get into lethally good crossing and cutback positions to feed the striker. It’s a skill that is hard to find outside the top six teams.

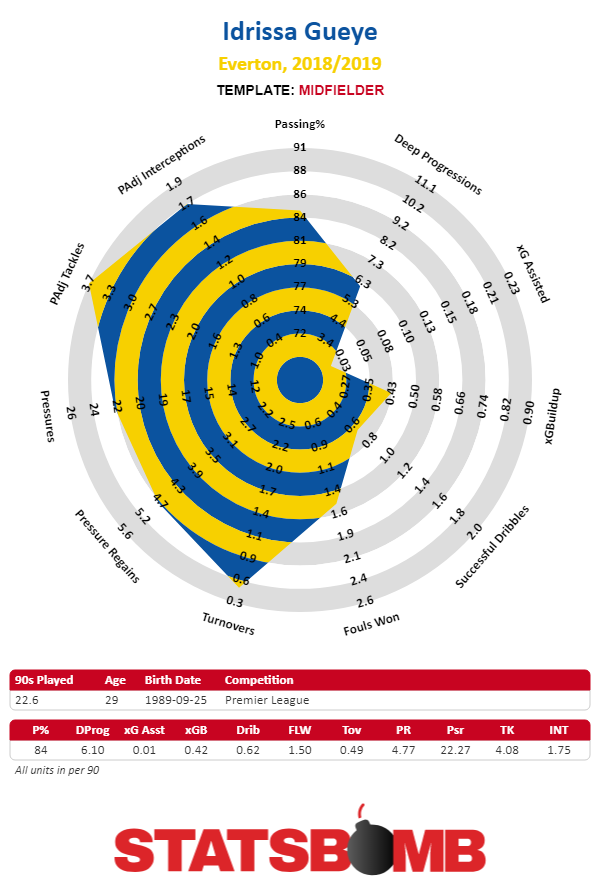

Wingers – Felipe Anderson, Ryan Fraser Ryan Fraser is just an absolute assist machine. His 0.26 expected goals assisted is tops outside the top six and eight overall. He doesn’t do a lot of different stuff, but the thing he does do, is get into lethally good crossing and cutback positions to feed the striker. It’s a skill that is hard to find outside the top six teams.  It’s cheating a little bit to put Anderson on the right and Fraser on the left when Anderson has played on the left all season, but I’m doing it anyway. Anderson plays more open play passes into the penalty area than anybody with 2.36 (including the top six only David Silva, Xherdan Shaqiri, Eden Hazard and Kieran Trippier play more). Also Anderson is going to do a little bit (or a lot) of basically everything else on the pitch to make this team good. On a team that’s built to be scrappy (and, like, we’re starting Ashley Barnes up top here, scrappy it is) Anderson’s defensive contributions will be essential. He averages over three combined tackles and interceptions per game. Midfield – Idrissa Gueye, Pascal Groß, Pierre-Emile Højbjerg This three man midfield can do it all. Gueye is the

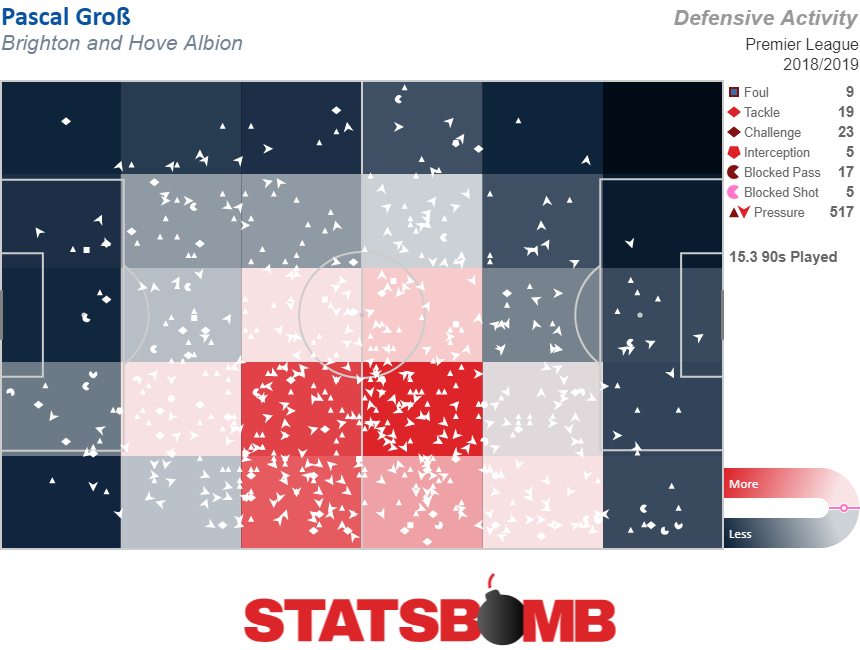

It’s cheating a little bit to put Anderson on the right and Fraser on the left when Anderson has played on the left all season, but I’m doing it anyway. Anderson plays more open play passes into the penalty area than anybody with 2.36 (including the top six only David Silva, Xherdan Shaqiri, Eden Hazard and Kieran Trippier play more). Also Anderson is going to do a little bit (or a lot) of basically everything else on the pitch to make this team good. On a team that’s built to be scrappy (and, like, we’re starting Ashley Barnes up top here, scrappy it is) Anderson’s defensive contributions will be essential. He averages over three combined tackles and interceptions per game. Midfield – Idrissa Gueye, Pascal Groß, Pierre-Emile Højbjerg This three man midfield can do it all. Gueye is the  Next to him are two players who are both very effective at applying defensive pressure in midfield and at moving the ball forward. Groß is the more active presser. He’s second in the league with 33.86 pressures per 90. A great number, but one which technically doesn’t qualify him for this team. We get to smuggle him onto the team for his crossing though (which Ashley Barnes will surely be thankful for). He completes 1.77 crosses per 90, the second most in the Premier League (only Kieran Trippier is ahead of him) and he completes them at a 54% clip which is truly impressive. Groß and Juan Mata at Manchester United are the only players completing over 0.75 crosses per 90 who maintain a completion rate of over 50%. But while the crossing is definitely a nice bonus, it’s the pressing that we’re really here for.

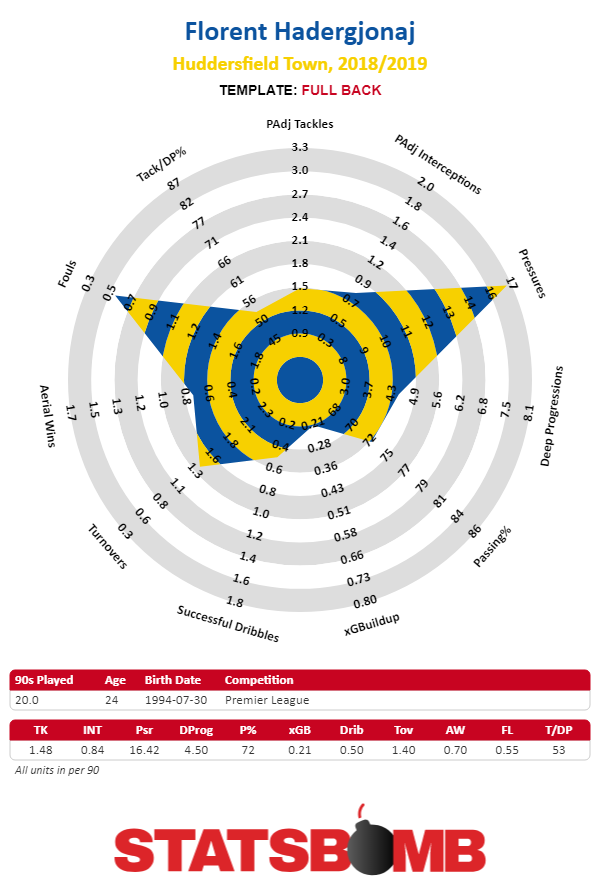

Next to him are two players who are both very effective at applying defensive pressure in midfield and at moving the ball forward. Groß is the more active presser. He’s second in the league with 33.86 pressures per 90. A great number, but one which technically doesn’t qualify him for this team. We get to smuggle him onto the team for his crossing though (which Ashley Barnes will surely be thankful for). He completes 1.77 crosses per 90, the second most in the Premier League (only Kieran Trippier is ahead of him) and he completes them at a 54% clip which is truly impressive. Groß and Juan Mata at Manchester United are the only players completing over 0.75 crosses per 90 who maintain a completion rate of over 50%. But while the crossing is definitely a nice bonus, it’s the pressing that we’re really here for.  The missing part of the puzzle is how does this team move the ball up the field. Right now it seems like Felipe Anderson is going to be all by himself picking the ball up from defense and trying to wriggle his way up the wing. But, not to fear, that’s where Højbjerg comes in. The vast majority of players who rack up a lot of deep progressions play for the top six teams. Højbjerg is the exception. He leads the non-six group and, along with Huddersfield’s Aaron Mooy is one of only two players outside the big six in the top 20 in the league at progressing the ball up the field from deep. His 8.27 deep progressions per 90, with a healthy assist from Groß who averages 6.42 should provide the team enough creativity on the ball to keep things ticking. Center backs – Michael Keane, Steve Cook Things break down really quickly when trying to do fun but ultimately pointless data experiments with defenders. So here, have Michael Keane and Steve Cook the top two players outside the top six in the league in possession adjusted clearances. They have 5.99 and 5.92 clearances apiece. Does that make them good? Probably not. Does that qualify them for this silly little team? You bet. Fullbacks – Lucas Digne, Florent Hadergjonaj As with center backs, fullbacks are simply impossible to actually evaluate statistically. So who knows if this will work at all. Lucas Digne has seemed mostly fine with Everton this season and he’s a big part of their attacking approach. He’s right behind Groß in completed crosses per 90 with 1.55 completed crosses per 90, so…yay? And speaking of crossing! A whole 73% of Florent Hadergjonaj’s passes in the final third are crosses, that’s the highest in the league, so please welcome your new right back.

The missing part of the puzzle is how does this team move the ball up the field. Right now it seems like Felipe Anderson is going to be all by himself picking the ball up from defense and trying to wriggle his way up the wing. But, not to fear, that’s where Højbjerg comes in. The vast majority of players who rack up a lot of deep progressions play for the top six teams. Højbjerg is the exception. He leads the non-six group and, along with Huddersfield’s Aaron Mooy is one of only two players outside the big six in the top 20 in the league at progressing the ball up the field from deep. His 8.27 deep progressions per 90, with a healthy assist from Groß who averages 6.42 should provide the team enough creativity on the ball to keep things ticking. Center backs – Michael Keane, Steve Cook Things break down really quickly when trying to do fun but ultimately pointless data experiments with defenders. So here, have Michael Keane and Steve Cook the top two players outside the top six in the league in possession adjusted clearances. They have 5.99 and 5.92 clearances apiece. Does that make them good? Probably not. Does that qualify them for this silly little team? You bet. Fullbacks – Lucas Digne, Florent Hadergjonaj As with center backs, fullbacks are simply impossible to actually evaluate statistically. So who knows if this will work at all. Lucas Digne has seemed mostly fine with Everton this season and he’s a big part of their attacking approach. He’s right behind Groß in completed crosses per 90 with 1.55 completed crosses per 90, so…yay? And speaking of crossing! A whole 73% of Florent Hadergjonaj’s passes in the final third are crosses, that’s the highest in the league, so please welcome your new right back.  Put it all together and what we’ve got is a starting 11 which emphasizes denying the opposition control of the midfield, moving the ball upfield quickly and then crossing smartly. Also, there are a couple of defenders. It’s all so crazy it just might work.

Put it all together and what we’ve got is a starting 11 which emphasizes denying the opposition control of the midfield, moving the ball upfield quickly and then crossing smartly. Also, there are a couple of defenders. It’s all so crazy it just might work.

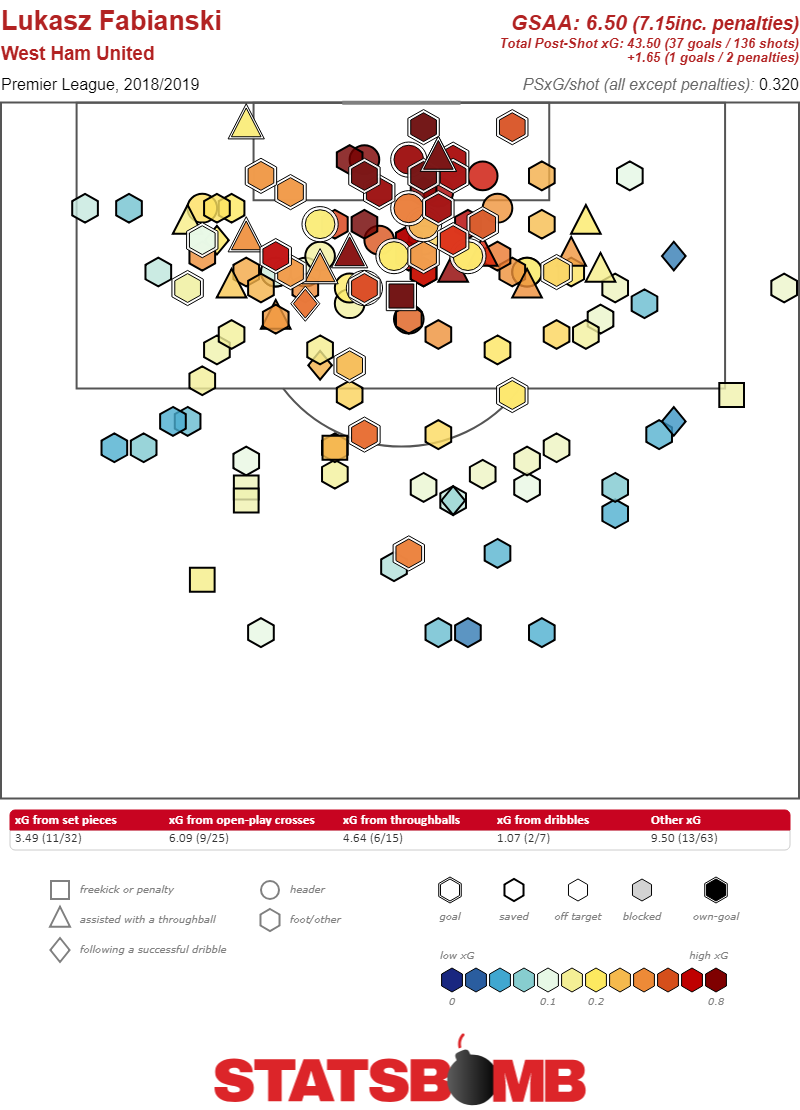

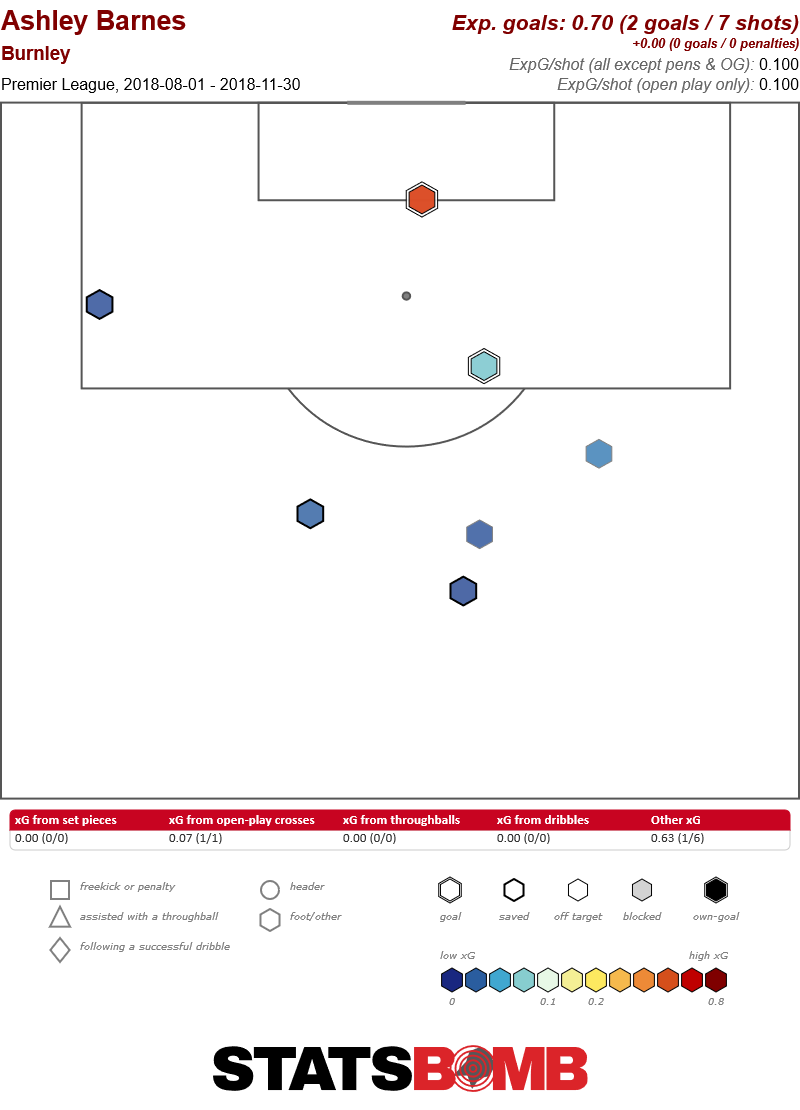

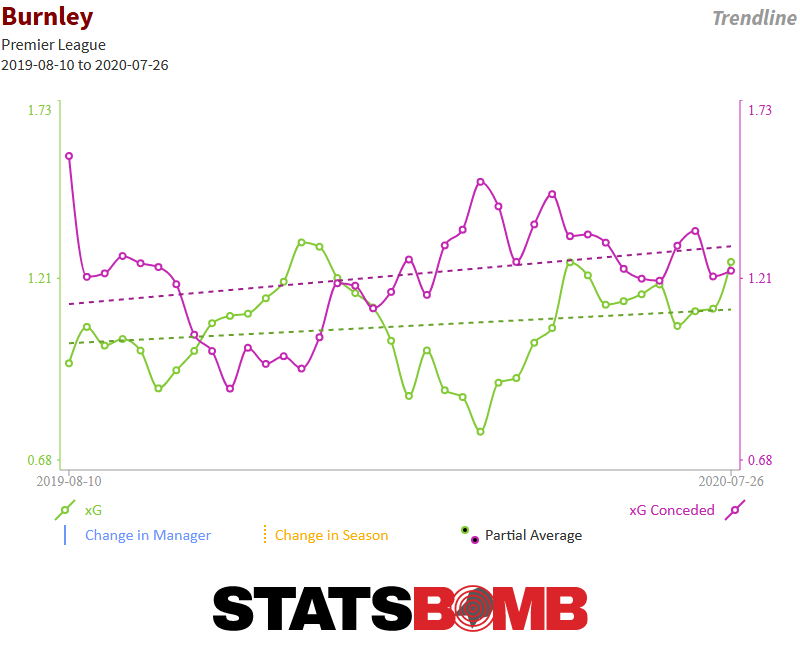

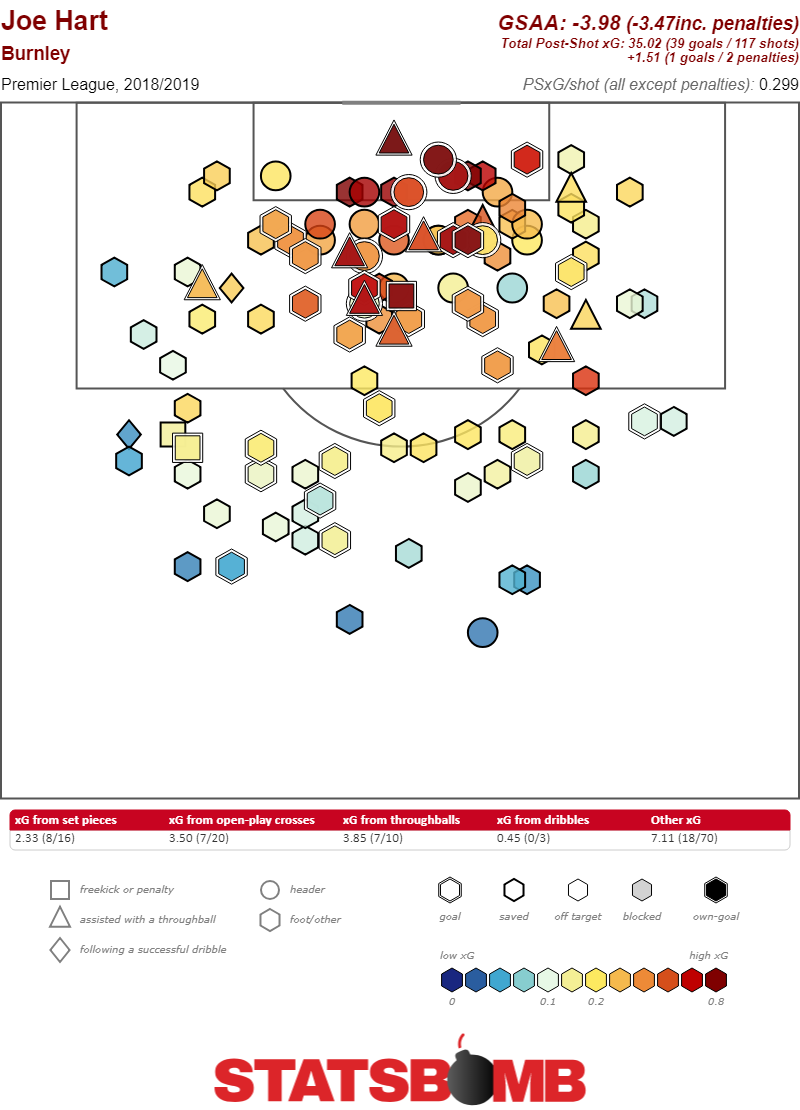

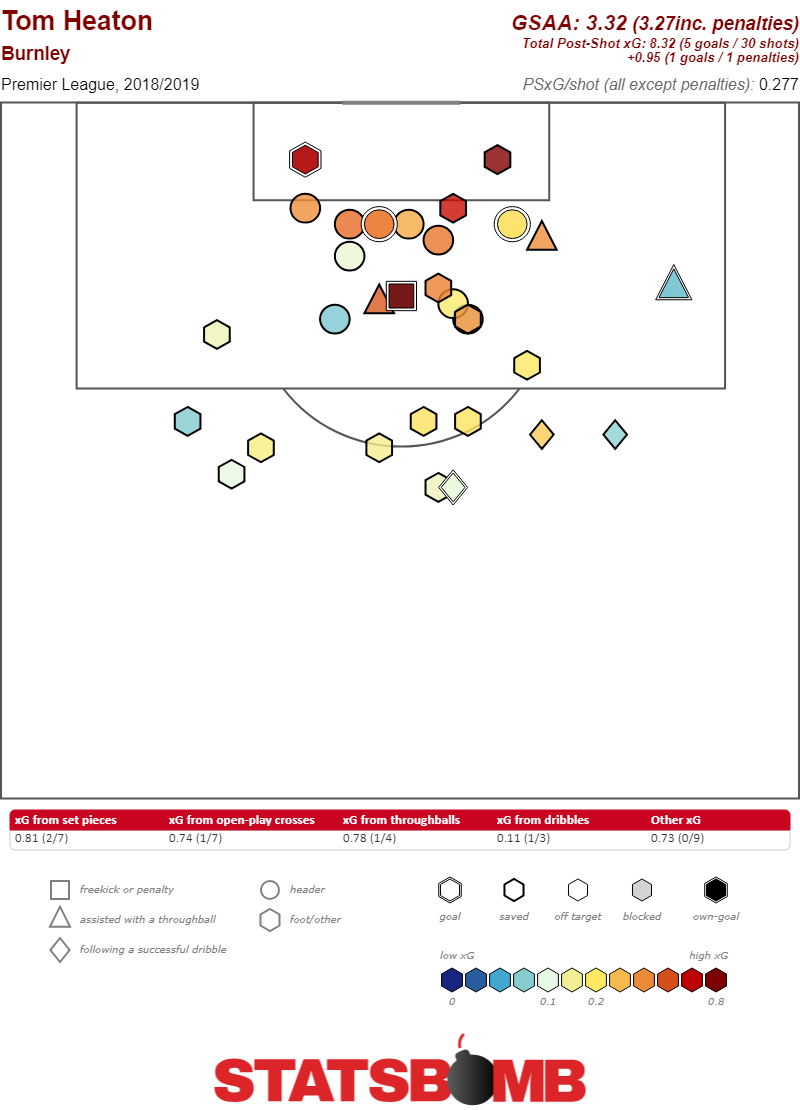

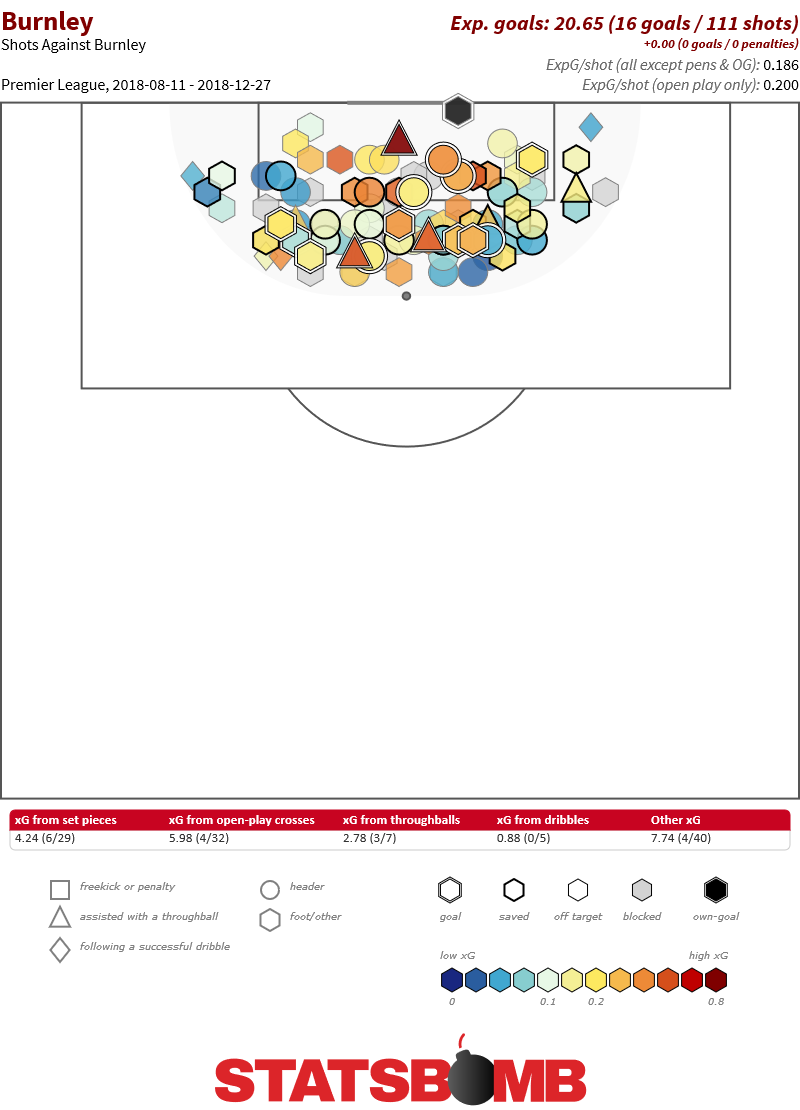

The vaunted Burnley defense had simply utterly collapsed over the first half of the year. The most plausible story of Burnley’s success (at least the most plausible won’t that wasn’t based on them being a cosmic joke instigated by the soccer gods on evil number wizards everywhere) was that Dyche’s teams did something in defense that tricked expected goals models. Somehow they turned modest defensive success into nearly unparalleled defensive solidity. Of course none of that really matters if instead of putting together defensive numbers indicative of modest success, the team is out there dumpster fire-ing every week. And that’s more or less what going on for the first half of this season. But then, something happened. Burnley changed keepers. Seven games ago Tom Heaton stepped back between the posts, and Burnley changed. The relationship between a keeper and his defense is difficult to untangle. There are things like shotstopping which are almost entirely within a keeper’s purview which we can measure, but other things get more complicated. The kinds of shots the opposition is taking for example are often a complicated mix of decisions made by attackers, defenders and defenses. So, it’s important to be cautious about making bold claims about causality. But, what’s absolutely clear is that Burnley’s defense when they play in front of Heaton looks totally different than when they play in front of Hart. Let’s start with the easiest stuff though. Heaton has been much better at stopping the shots he’s faced this season than Hart was. In 19 games this season, Hart gave up roughly four more goals than expected. Not great.

The vaunted Burnley defense had simply utterly collapsed over the first half of the year. The most plausible story of Burnley’s success (at least the most plausible won’t that wasn’t based on them being a cosmic joke instigated by the soccer gods on evil number wizards everywhere) was that Dyche’s teams did something in defense that tricked expected goals models. Somehow they turned modest defensive success into nearly unparalleled defensive solidity. Of course none of that really matters if instead of putting together defensive numbers indicative of modest success, the team is out there dumpster fire-ing every week. And that’s more or less what going on for the first half of this season. But then, something happened. Burnley changed keepers. Seven games ago Tom Heaton stepped back between the posts, and Burnley changed. The relationship between a keeper and his defense is difficult to untangle. There are things like shotstopping which are almost entirely within a keeper’s purview which we can measure, but other things get more complicated. The kinds of shots the opposition is taking for example are often a complicated mix of decisions made by attackers, defenders and defenses. So, it’s important to be cautious about making bold claims about causality. But, what’s absolutely clear is that Burnley’s defense when they play in front of Heaton looks totally different than when they play in front of Hart. Let’s start with the easiest stuff though. Heaton has been much better at stopping the shots he’s faced this season than Hart was. In 19 games this season, Hart gave up roughly four more goals than expected. Not great.  The difference between his save percentage of 66.7% and his expected save percentage of 70.1% is negative 3.4%. Of the 24 keepers who have played more than 600 minutes this year only five have a larger negative difference. Heaton, on the other hand, has been fantastic.

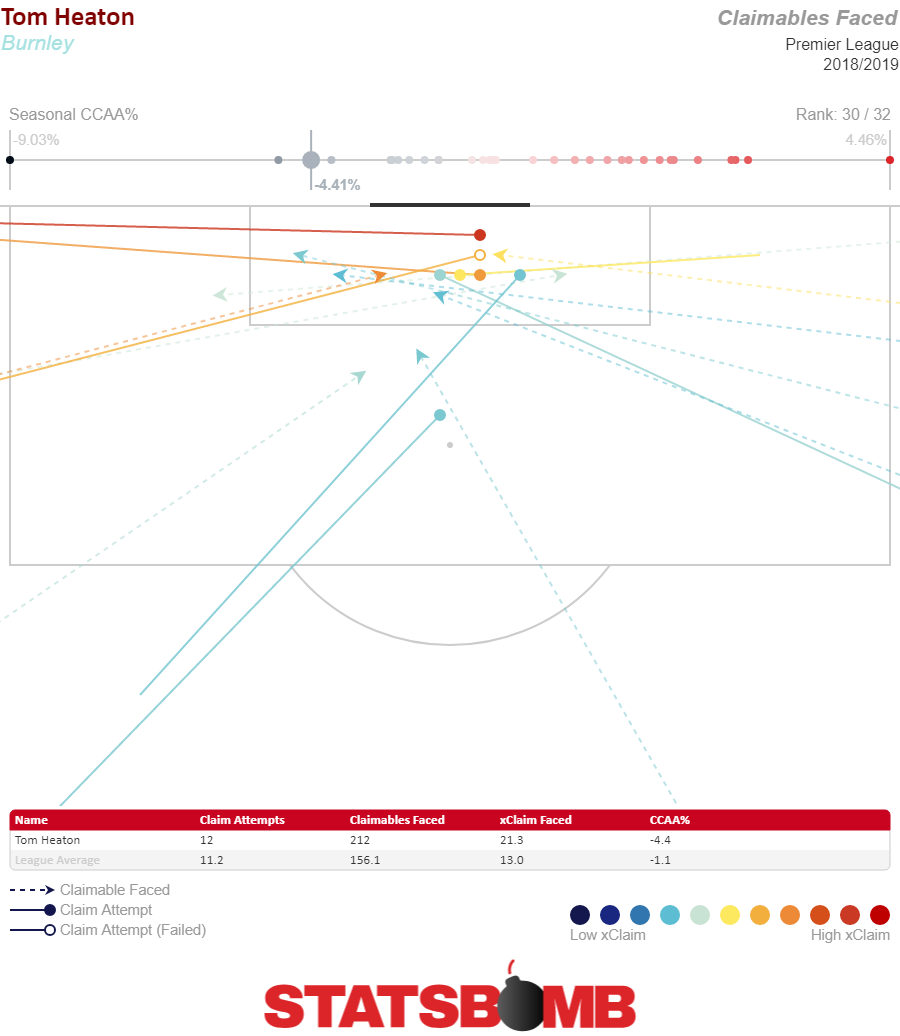

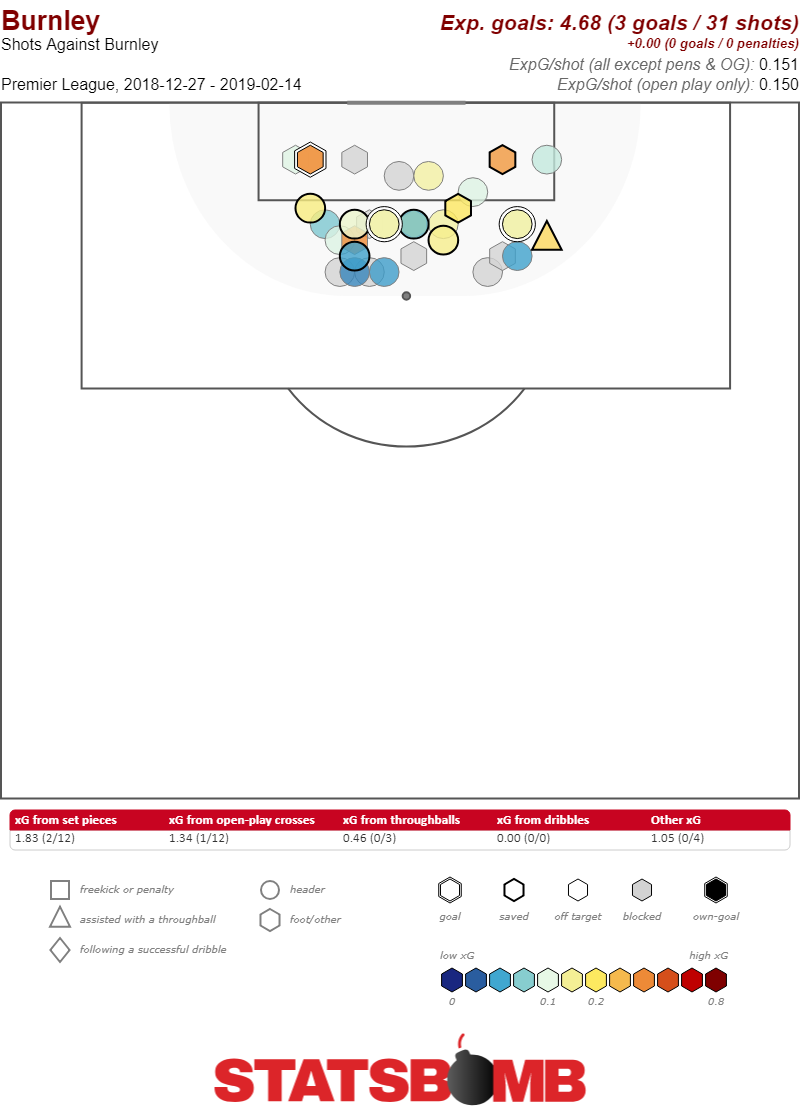

The difference between his save percentage of 66.7% and his expected save percentage of 70.1% is negative 3.4%. Of the 24 keepers who have played more than 600 minutes this year only five have a larger negative difference. Heaton, on the other hand, has been fantastic.  He’s already saved 3.32 more goals than an average keeper would. His save percentage of 83.3% is not only the highest in the league, it’s 11.1% higher than his expected save percentage. That gap is also the highest in the league. He’s been absolutely phenomenal. So, one thing that’s going on is that Heaton is just saving a lot more goals than Hart was and that makes a big difference. But, there’s more. Because Burnley’s defense is absolutely also playing better. With Hart in goal, Burnley gave up a whopping 19.58 shots per game and an xG per shot of 0.10. With Heaton those numbers have both improved. The side is currently conceding 13.57 shots per game at 0.08 xG per shot. They’ve both improved in terms of the volume and the quality they’re giving up. Some of that probably has something to do with the level of competition Burnley are facing. Their recent hot streak has come against West Ham, Huddersfield, Fulham, Watford, Manchester United, Southampton, and Brighton. There’s only one potent attacking team in that mix. But, even against that backdrop the defensive improvement is stark, and it’s worth investigating how the two keepers might be influencing it. No Burnley keeper is ever going to come across as aggressive. The conservative style the team plays means that a keeper’s job is to mostly stay at home on his line while defenders deal with things in front of him. Accordingly, Heaton has only attempted to claim 12 balls in the seven matches he’s played, when the StatsBomb model expects average keeper to come for just over 21. However, that conservatism is only evident in balls that are relatively unlikely for any keeper to claim. He’s claimed only five balls that the model suggests have a 20% chance or less of a keeper collecting, while an average keeper might collect 14. On the mode dangerous balls, the ones that keepers collect 30% of the time or more, Heaton is much closer to expectations. He’s attempted seven claims on 16 balls, right in line with what the model predicts. He’s succeeded on six of those seven attempts.

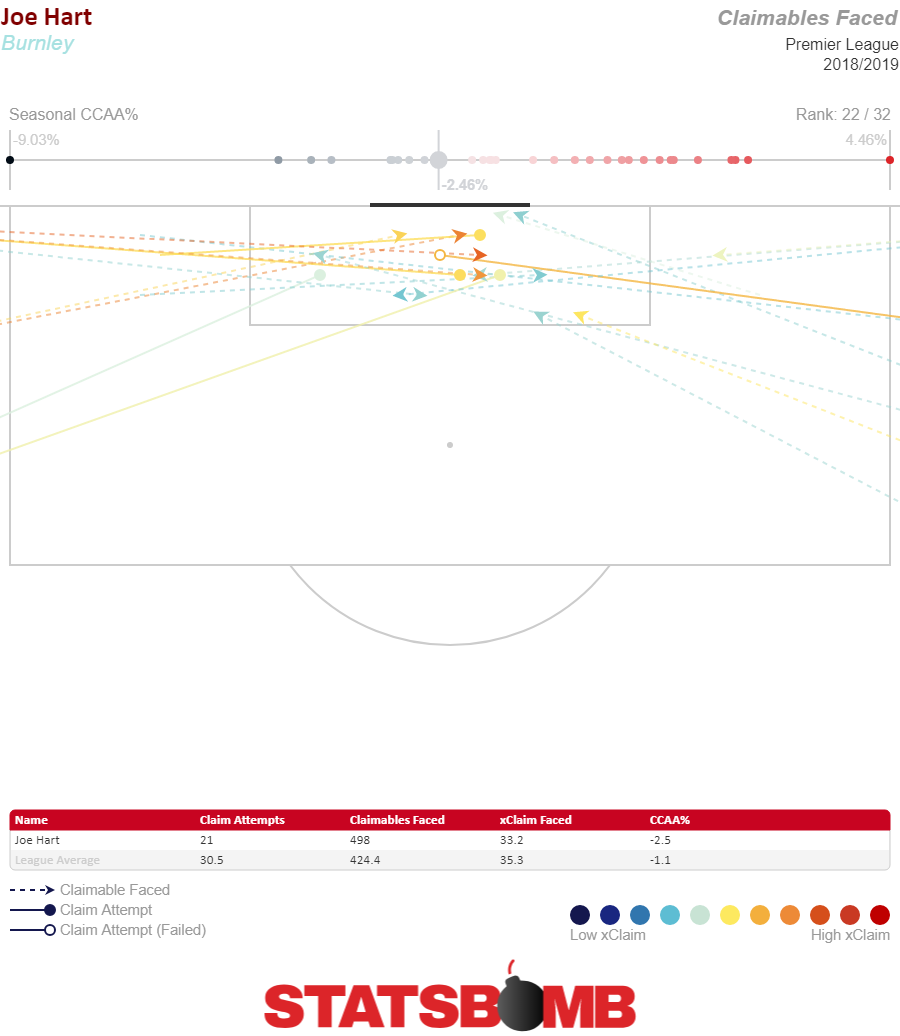

He’s already saved 3.32 more goals than an average keeper would. His save percentage of 83.3% is not only the highest in the league, it’s 11.1% higher than his expected save percentage. That gap is also the highest in the league. He’s been absolutely phenomenal. So, one thing that’s going on is that Heaton is just saving a lot more goals than Hart was and that makes a big difference. But, there’s more. Because Burnley’s defense is absolutely also playing better. With Hart in goal, Burnley gave up a whopping 19.58 shots per game and an xG per shot of 0.10. With Heaton those numbers have both improved. The side is currently conceding 13.57 shots per game at 0.08 xG per shot. They’ve both improved in terms of the volume and the quality they’re giving up. Some of that probably has something to do with the level of competition Burnley are facing. Their recent hot streak has come against West Ham, Huddersfield, Fulham, Watford, Manchester United, Southampton, and Brighton. There’s only one potent attacking team in that mix. But, even against that backdrop the defensive improvement is stark, and it’s worth investigating how the two keepers might be influencing it. No Burnley keeper is ever going to come across as aggressive. The conservative style the team plays means that a keeper’s job is to mostly stay at home on his line while defenders deal with things in front of him. Accordingly, Heaton has only attempted to claim 12 balls in the seven matches he’s played, when the StatsBomb model expects average keeper to come for just over 21. However, that conservatism is only evident in balls that are relatively unlikely for any keeper to claim. He’s claimed only five balls that the model suggests have a 20% chance or less of a keeper collecting, while an average keeper might collect 14. On the mode dangerous balls, the ones that keepers collect 30% of the time or more, Heaton is much closer to expectations. He’s attempted seven claims on 16 balls, right in line with what the model predicts. He’s succeeded on six of those seven attempts.  Hart is similarly conservative overall, attempting to claim 21 balls when the model expects he’d have gone for 33, but the distribution of his conservatism is different. In his 19 games he’s faced 20 total balls that the model expects a keeper to claim at least 30% of the time. He’s come for five of them (and was successful four out of five times), when the model predicts a keeper would come on average 9.5% of the time. Over the course of the season Hart has shown to be unable to prevent teams from putting high value crosses right on his doorstep.

Hart is similarly conservative overall, attempting to claim 21 balls when the model expects he’d have gone for 33, but the distribution of his conservatism is different. In his 19 games he’s faced 20 total balls that the model expects a keeper to claim at least 30% of the time. He’s come for five of them (and was successful four out of five times), when the model predicts a keeper would come on average 9.5% of the time. Over the course of the season Hart has shown to be unable to prevent teams from putting high value crosses right on his doorstep.  Now, let’s zoom out to the team level again, equipped with the knowledge that Hart has a tendency not to come for balls played into areas where many keepers attempt to collect them. Here are all the shots Burnley gave up within 12 yards of the goal with Hart as keeper.

Now, let’s zoom out to the team level again, equipped with the knowledge that Hart has a tendency not to come for balls played into areas where many keepers attempt to collect them. Here are all the shots Burnley gave up within 12 yards of the goal with Hart as keeper.  That works out to 5.84 shots per match at a 0.19 xG per shot. Now, let’s look at Heaton.

That works out to 5.84 shots per match at a 0.19 xG per shot. Now, let’s look at Heaton.  That works out to 4.42 shots per match and an xG per shot of 0.15. That’s a pretty huge difference, like half an expected goal per match difference. Even if we allow that the difference is probably fairly exaggerated by the level of competition it seems quite clear that when Heaton came back into the side it all of a sudden became harder for Burnley’s opponents to generate shots closer to goal. All this keeper data is new, and because of that it’s always worth remembering that using it is a bit of a high wire act. It’s possible that all this Heaton performance is just dumb luck and he’s come plummeting back to earth. It’s possible that we should look at Hart’s failure to come for crosses as not necessarily indicative of his abilities. It’s possible that Burnley will go back to conceding shots close to goal against tomorrow. None of this is proof. What it is is circumstantial evidence. And boy is there a lot of it. Burnley’s performances suddenly turned around when they removed Hart from goal and replaced him with Heaton. Their defense suddenly stopped conceding as many chances close to their keeper. Their keepers have dramatically different records both when it comes to stopping shots and when it comes to claiming balls in their area. Put it all together and it makes a powerful case that the reason Burnley’s season has turned around is that Joe Hart is bad and Tom Heaton is good. Keepers, it turns out, might just be important.

That works out to 4.42 shots per match and an xG per shot of 0.15. That’s a pretty huge difference, like half an expected goal per match difference. Even if we allow that the difference is probably fairly exaggerated by the level of competition it seems quite clear that when Heaton came back into the side it all of a sudden became harder for Burnley’s opponents to generate shots closer to goal. All this keeper data is new, and because of that it’s always worth remembering that using it is a bit of a high wire act. It’s possible that all this Heaton performance is just dumb luck and he’s come plummeting back to earth. It’s possible that we should look at Hart’s failure to come for crosses as not necessarily indicative of his abilities. It’s possible that Burnley will go back to conceding shots close to goal against tomorrow. None of this is proof. What it is is circumstantial evidence. And boy is there a lot of it. Burnley’s performances suddenly turned around when they removed Hart from goal and replaced him with Heaton. Their defense suddenly stopped conceding as many chances close to their keeper. Their keepers have dramatically different records both when it comes to stopping shots and when it comes to claiming balls in their area. Put it all together and it makes a powerful case that the reason Burnley’s season has turned around is that Joe Hart is bad and Tom Heaton is good. Keepers, it turns out, might just be important.

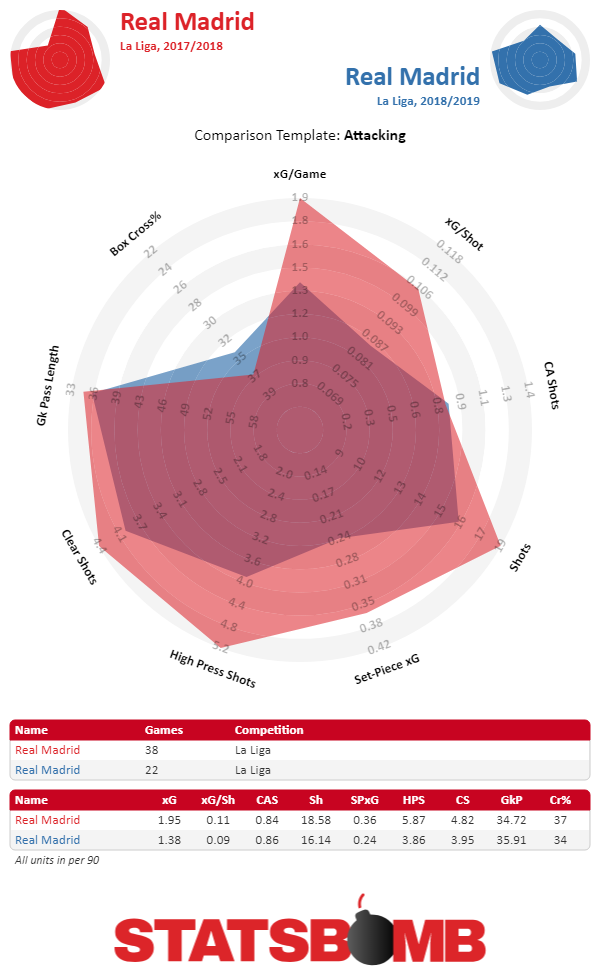

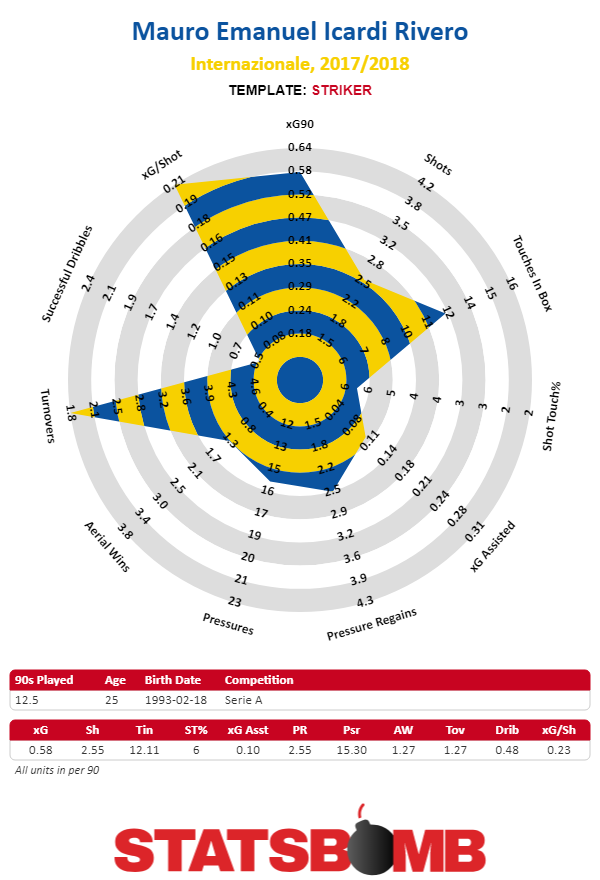

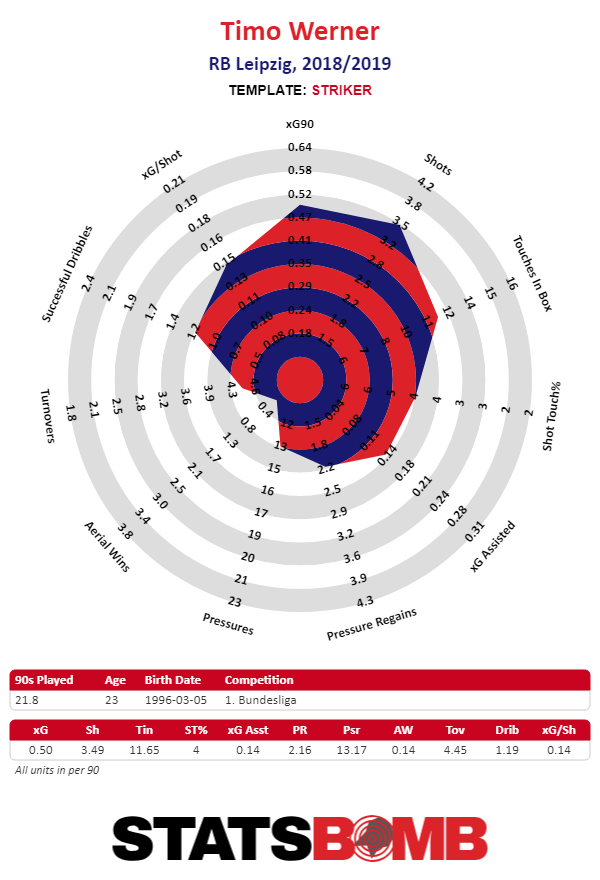

The case for Icardi is that while Benzema is proving himself unable to provide quite enough thrust as the main option, Icardi’s whole career has been about him being the central scorer for his team. There’s a real chance Icardi’s production in the box would increase dramatically as he played for a Madrid side with superstars feeding him the ball on a regular basis as opposed to working in Inter’s heavily cross based system. The concern of course is that while Benzema’s scoring comes with really good creative work, Icardi’s does not. But, Real Madrid don’t need a center forward who can facilitate somebody else, they need one who can score goals. If Icardi’s shooting volume goes up as he gets a higher level of service, he could end up as a mainstay of Madrid’s attack for the next five years. But, let’s say that Madrid are wary of Icardi’s relatively low shot totals. They don’t want to pay a hefty price for a forward that might not give them more goal scoring than the one they’ve got. Sure Icardi looks likely to thrive in front of Madrid’s midfield but it’s not a sure thing. Well, there are plenty of other options. Timo Werner stars for RB Leipzig. He’s taken 3.57 shots per 90 and averages 0.52 xG per 90. He’s much closer to a traditional shot machine. Icardi has tendencies to lurk around and then pop up for a great shot. Werner just shoots a lot.

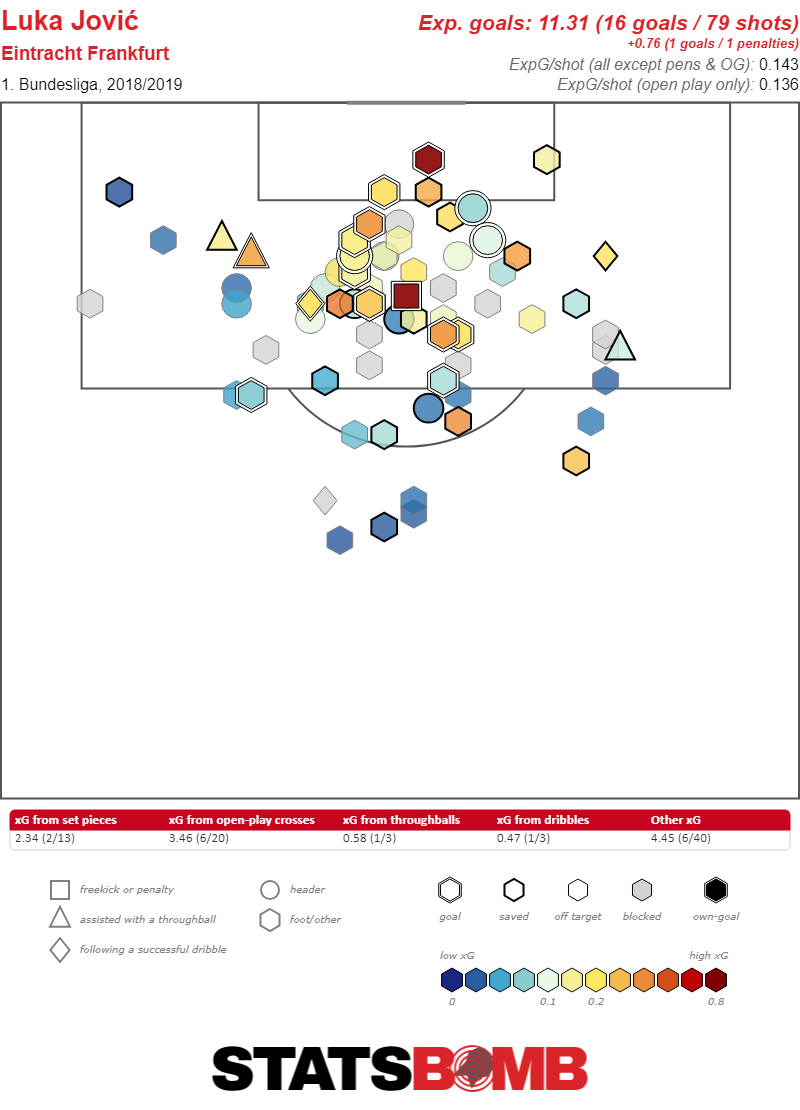

The case for Icardi is that while Benzema is proving himself unable to provide quite enough thrust as the main option, Icardi’s whole career has been about him being the central scorer for his team. There’s a real chance Icardi’s production in the box would increase dramatically as he played for a Madrid side with superstars feeding him the ball on a regular basis as opposed to working in Inter’s heavily cross based system. The concern of course is that while Benzema’s scoring comes with really good creative work, Icardi’s does not. But, Real Madrid don’t need a center forward who can facilitate somebody else, they need one who can score goals. If Icardi’s shooting volume goes up as he gets a higher level of service, he could end up as a mainstay of Madrid’s attack for the next five years. But, let’s say that Madrid are wary of Icardi’s relatively low shot totals. They don’t want to pay a hefty price for a forward that might not give them more goal scoring than the one they’ve got. Sure Icardi looks likely to thrive in front of Madrid’s midfield but it’s not a sure thing. Well, there are plenty of other options. Timo Werner stars for RB Leipzig. He’s taken 3.57 shots per 90 and averages 0.52 xG per 90. He’s much closer to a traditional shot machine. Icardi has tendencies to lurk around and then pop up for a great shot. Werner just shoots a lot.  It’s not the best shot map. He lets fly from odd angles and doesn’t necessarily camp out in the center of the box, although Leipzig play a style that is more about getting Werner the ball in space than creating opportunities to pop up in the box after sustained possession. But you can’t knock the production. But, maybe the difference in styles spooks Madrid. They’d want to be confident that his game could adjust to a situation where he was playing in front of a team with lots of possession, rather than one looking to break all the time, Sure he’s only 22 and puts up huge numbers, but Bayern Munich are also likely to want him. Who wants to get into a bidding war over a striker that may not even be a stylistic fit. Not to worry there are still plenty more options. If Madrid wanted to take an ambitious swing there’s always Luka Jovic. At 21 he’s even younger than Werner. At Eintracht Frankfurt he plays on a worse team than Werner, but he puts up numbers that are just as big. Dude literally does nothing but sit in the box and score goals.

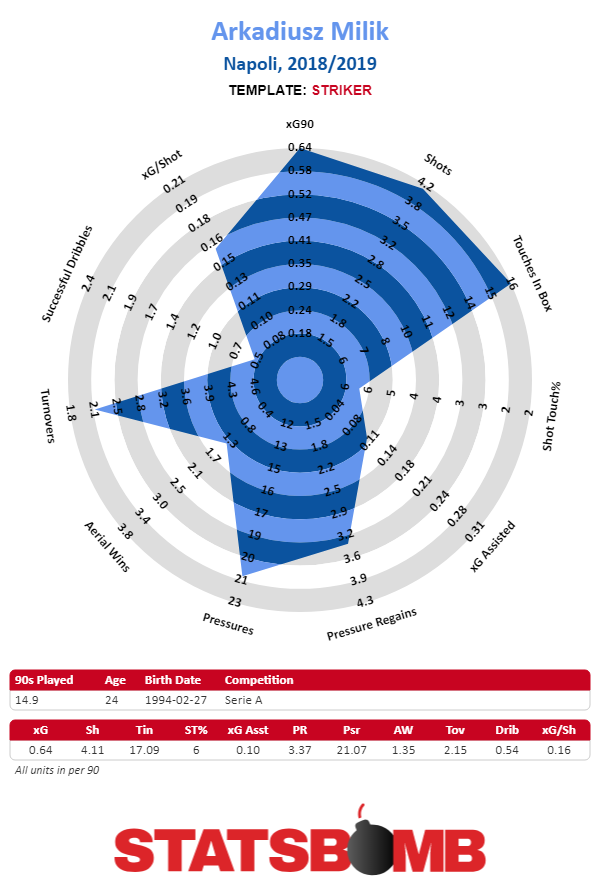

It’s not the best shot map. He lets fly from odd angles and doesn’t necessarily camp out in the center of the box, although Leipzig play a style that is more about getting Werner the ball in space than creating opportunities to pop up in the box after sustained possession. But you can’t knock the production. But, maybe the difference in styles spooks Madrid. They’d want to be confident that his game could adjust to a situation where he was playing in front of a team with lots of possession, rather than one looking to break all the time, Sure he’s only 22 and puts up huge numbers, but Bayern Munich are also likely to want him. Who wants to get into a bidding war over a striker that may not even be a stylistic fit. Not to worry there are still plenty more options. If Madrid wanted to take an ambitious swing there’s always Luka Jovic. At 21 he’s even younger than Werner. At Eintracht Frankfurt he plays on a worse team than Werner, but he puts up numbers that are just as big. Dude literally does nothing but sit in the box and score goals.  While Werner creates for himself with the ball at his feet, Jovic does not. Jovic gets himself into the middle of the box, sees ball, thwaps ball. Rinse, repeat. There are some teams where that might be a concern. Some teams might struggle to get Jovic the ball enough to take advantage of his skills in the box. Madrid certainly aren’t one of those teams. Stylistically he certainly seems like he’d be a fit for a team like Madrid. The concern here is that going from Frankfurt to Madrid is a major jump. Madrid would be gambling that he’d be able to perform not only week in and week out in the league but also that he’d be able to lead the line in the Champions League, that he’d be good enough to go toe to toe with the best defenders in the world and provide enough attacking thrust to come out ahead. It’s reasonable to think that he has that ability, but playing at Frankfurt he certainly hasn’t had the ability to show it yet. If Madrid don’t want to take any of those risks they could always look for a slightly better bargain in Arkadiusz Milik. Milik is only 24 and already has one catastrophic knee injury in his past. He’s also absolutely killing it this season for Napoli.

While Werner creates for himself with the ball at his feet, Jovic does not. Jovic gets himself into the middle of the box, sees ball, thwaps ball. Rinse, repeat. There are some teams where that might be a concern. Some teams might struggle to get Jovic the ball enough to take advantage of his skills in the box. Madrid certainly aren’t one of those teams. Stylistically he certainly seems like he’d be a fit for a team like Madrid. The concern here is that going from Frankfurt to Madrid is a major jump. Madrid would be gambling that he’d be able to perform not only week in and week out in the league but also that he’d be able to lead the line in the Champions League, that he’d be good enough to go toe to toe with the best defenders in the world and provide enough attacking thrust to come out ahead. It’s reasonable to think that he has that ability, but playing at Frankfurt he certainly hasn’t had the ability to show it yet. If Madrid don’t want to take any of those risks they could always look for a slightly better bargain in Arkadiusz Milik. Milik is only 24 and already has one catastrophic knee injury in his past. He’s also absolutely killing it this season for Napoli.  A 24 year-old player putting up these numbers without Milik’s history of tissue-paper knees would command a gigantic fee. The list for players who take four shots per 90 and also average over 0.15 xG per shot is exceedingly small. Across the big five leagues this season it’s Sergio Aguero, Kylian Mbappe, Milik, and Paco Alcazar. That’s it, that’s the list. Milik will likely come cheaper than his numbers this season indicate, which is justified because knees are important, and his may not exist. But, Real Madrid have the luxury of not necessarily needing Milik to be healthy forever. If they can buy him and get three good years out of him, and then he’s shot at 27, that’s a scenario that works out just fine to a team that has the resources to go replace him. When you’re operating at Madrid’s level there are very few perfect transfers. But, slightly below the can’t miss superstar level there are endless options that have different kinds of risks associated with them. Madrid’s focus should be on evaluating those risks and choosing which one makes the most sense. Instead, if Eden Hazard is to be believed (and who knows if he should be) they’re just avoiding trying to fix their main problem altogether.