Watford’s 2018-19 season is not yet over, but it’s safe to call it a success. The questions that remain unanswered — Can the Hornets finish better than tenth? Can they win a cup final? — are the kinds that point to things having gone right.

To figure out what’s gone right, it’s worth revisiting the pre-season assessment of Watford’s prospects. This gives some structure for thinking about the team’s pre-existing strengths and the problems they have subsequently solved. Disclosure: I wrote StatsBomb’s preview. Parts of it hold up, but it also concluded “The team’s upside is not high enough to expect big things or rule out relegation, but its downside risk is limited.” The first half of that formulation guarantees that this will not be a victory lap.

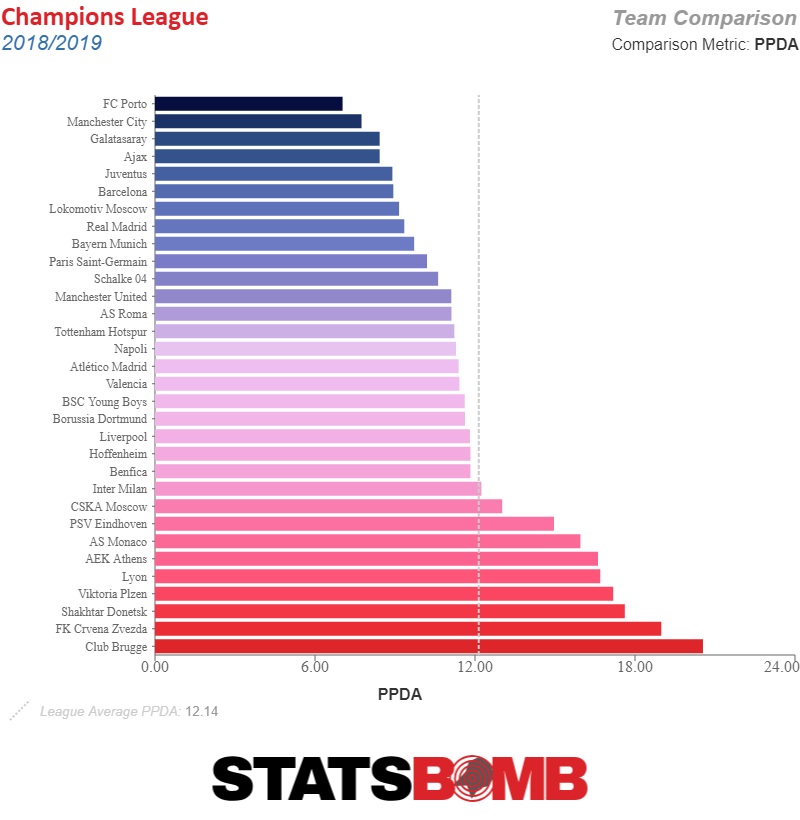

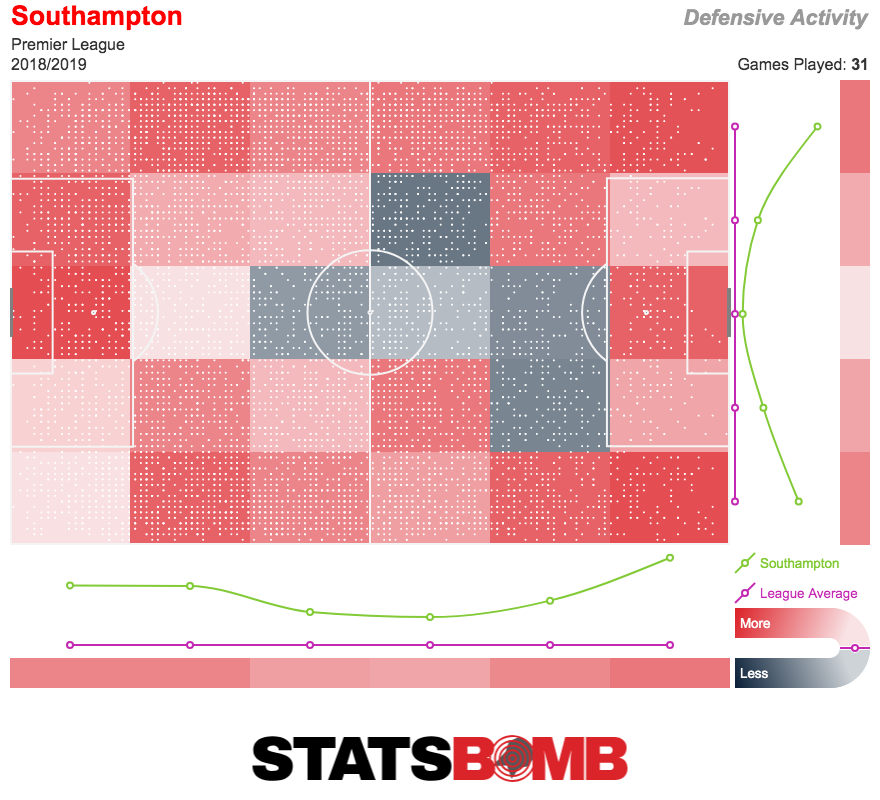

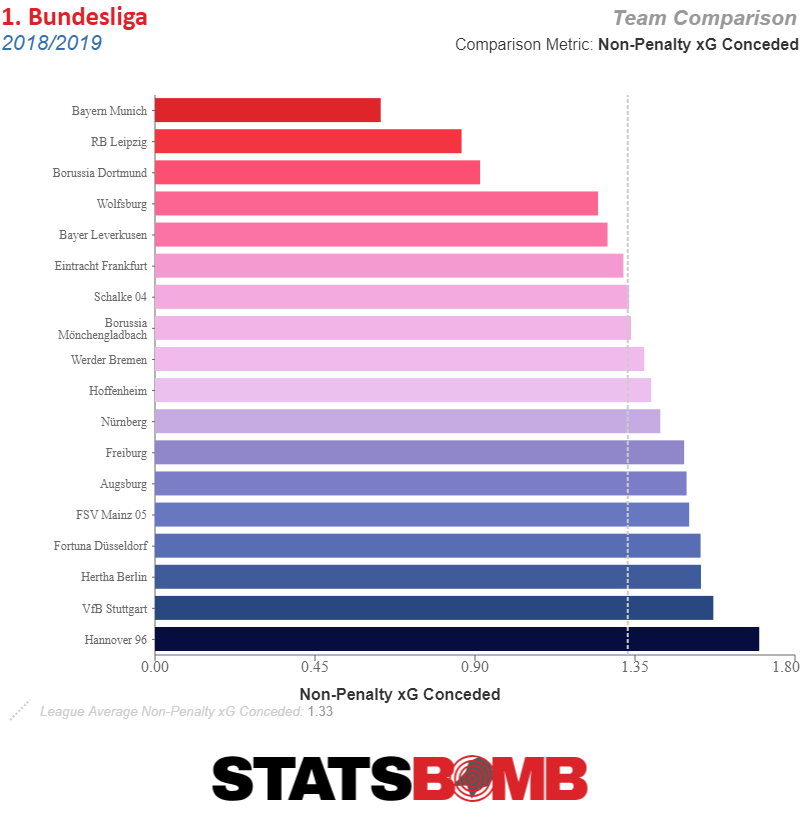

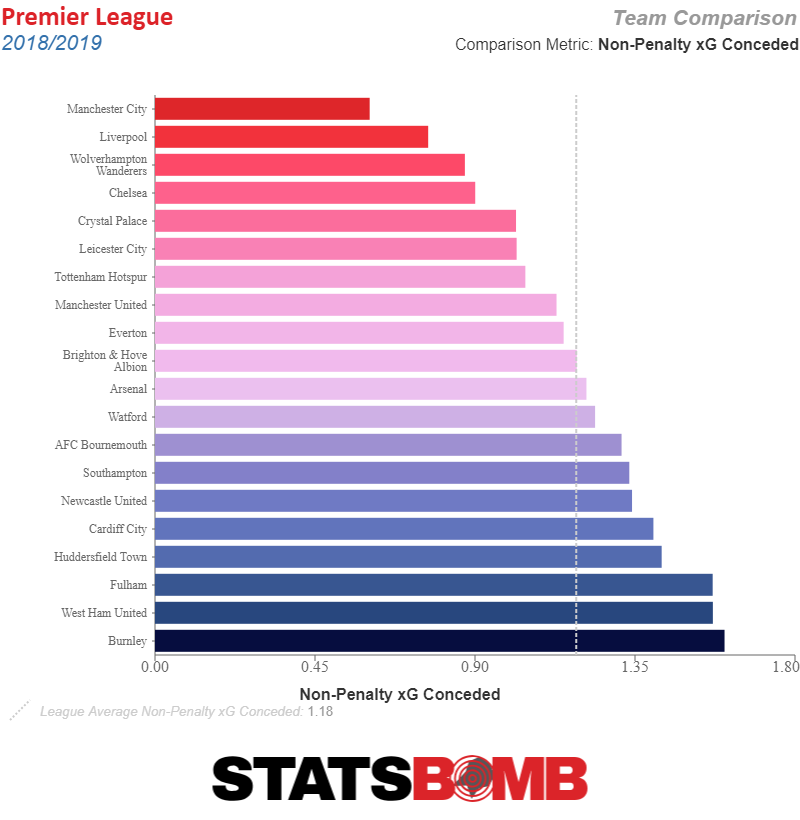

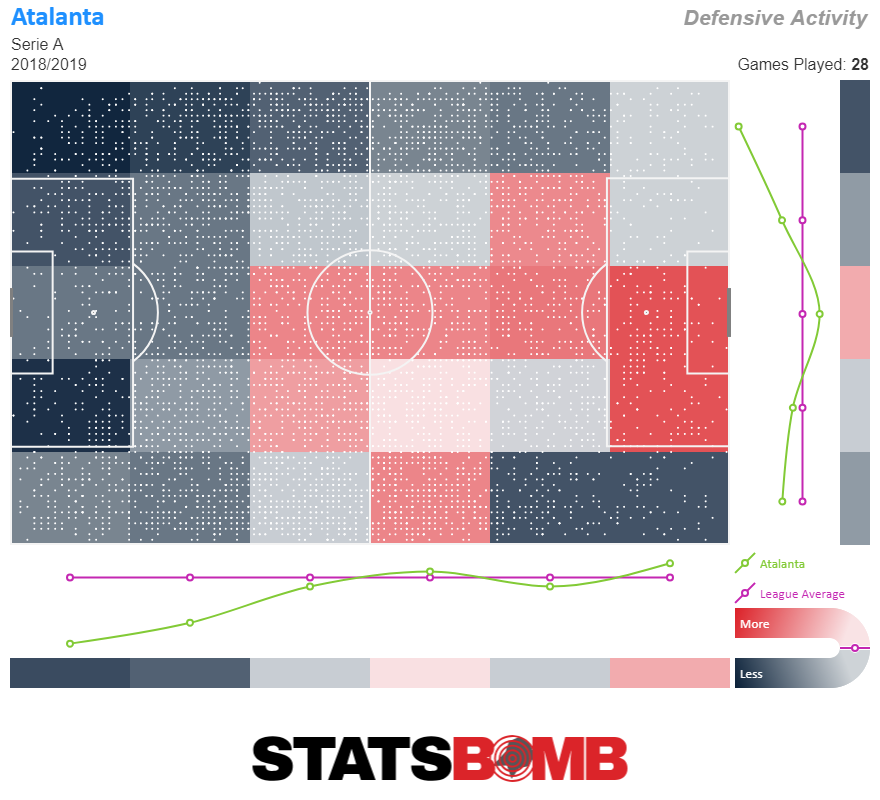

Watford is conceding 1.26 expected goals per 90 minutes this season, good for 11th in the Premier League and a slight improvement on last season’s total of 1.31. This slight improvement doesn’t really mean that the team’s approach has changed. In the first half of 2017-18, under Marco Silva, Watford pressed high and was regularly torn apart on the counter. Their defense stabilized under Javi Gracia, who maintained the team’s high press but cut out its tendency to be easily picked apart. (Watford is now a touch worse than league average in counter-attacking shots conceded.)

The Hornets press high up the pitch, but are prepared to drop back and defend in their third. The only defensive difference is that Watford’s shot suppression has regressed to league average. This has largely been counterbalanced by the expected goal value of the shots the Hornets concede — a serious issue last season — moving closer to average. With more than a year of Javi Gracia to consider, it seems clear that his defensive improvements were not a blip. His strategy is solid and produces consistent mid-table results.

The bigger questions about Watford going into this season concerned the attack. Fixing the defence without losing much of the offensive output the more gung-ho Silva had produced was Gracia’s big achievement in 2018. This season, he would have to repeat the feat without Richarlison, who accounted for 20% of Watford’s shots in 2017-18 and had been a fertile source of expected goals (if not actual ones) in Gracia’s half-season. Moreover, Abdoulaye Doucoure could hardly be expected to score more than double his expected goals total. (Reader: He has not.) Replacing all this output without sacrificing the team’s defensive solidity would be an even bigger challenge.

The good news is that the attack has remained basically good enough. Watford’s shots are of league average in quality but slightly fewer than the average team, all of which adds up to 1.15 expected goals per 90 minutes. That attack, which ranks eighth in the league, generates goals in two ways that merit further consideration.

Watford’s first offensive option is to turn defence into attack. Last season, they went from having 2.38 high-press shots per 90 minutes under Silva to 3.21 in Gracia’s half-season. This season, they’re generating more high-press shots (3.28) per 90 minutes than league average (3.17). Generating shots off the press is the main way Gracia maintained Watford’s scoring rate while fixing its defence. The strategy also works well with the available personnel (more on them in a moment.)

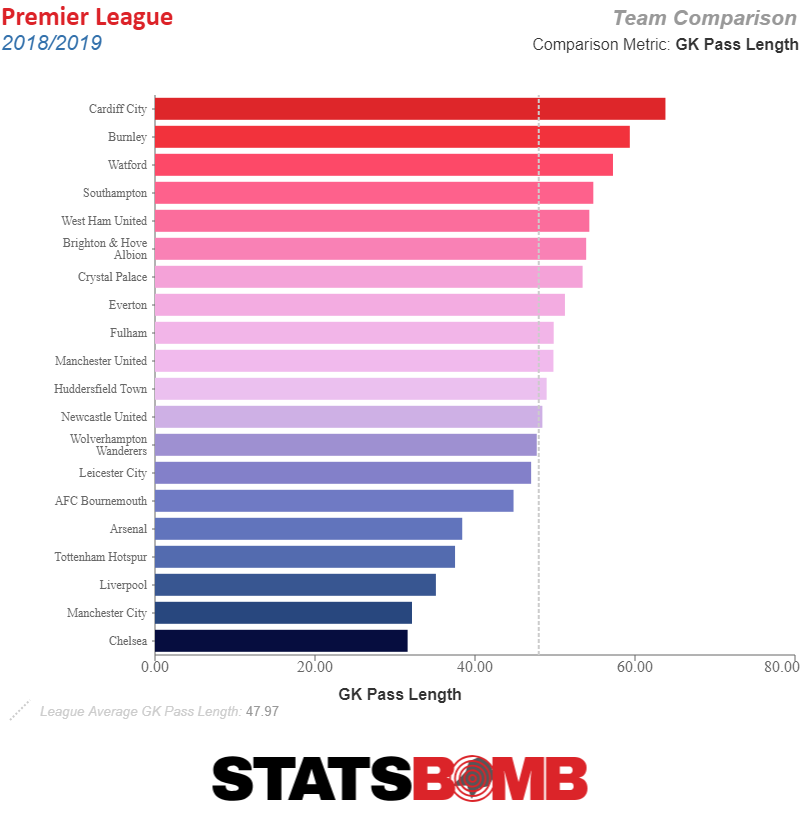

Watford’s other attacking strategy is to lump it long. Passes by the team’s goalkeepers are 20% longer than the league average.

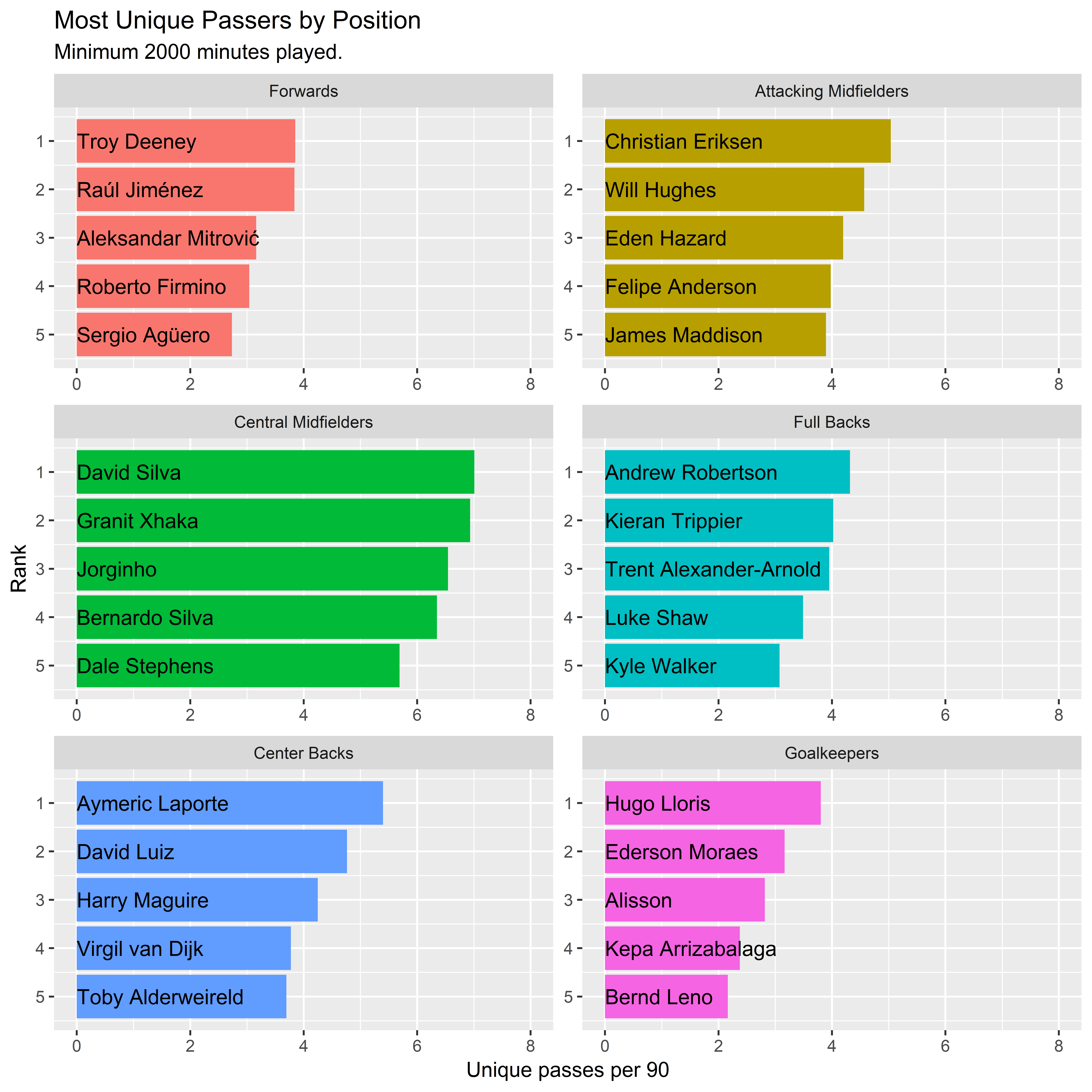

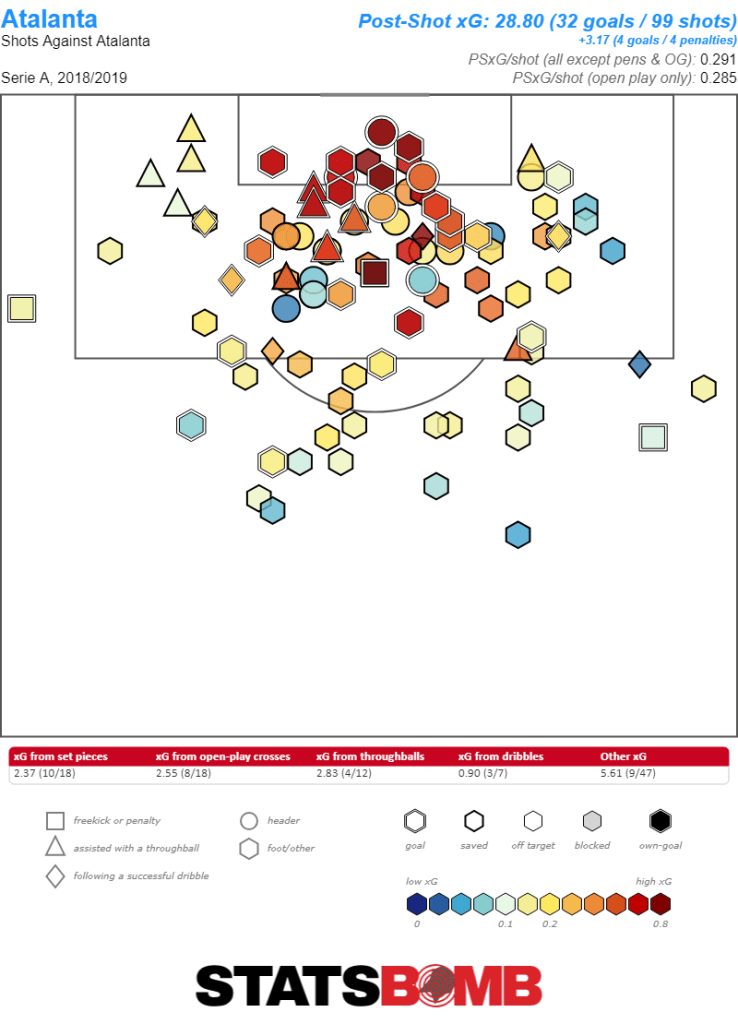

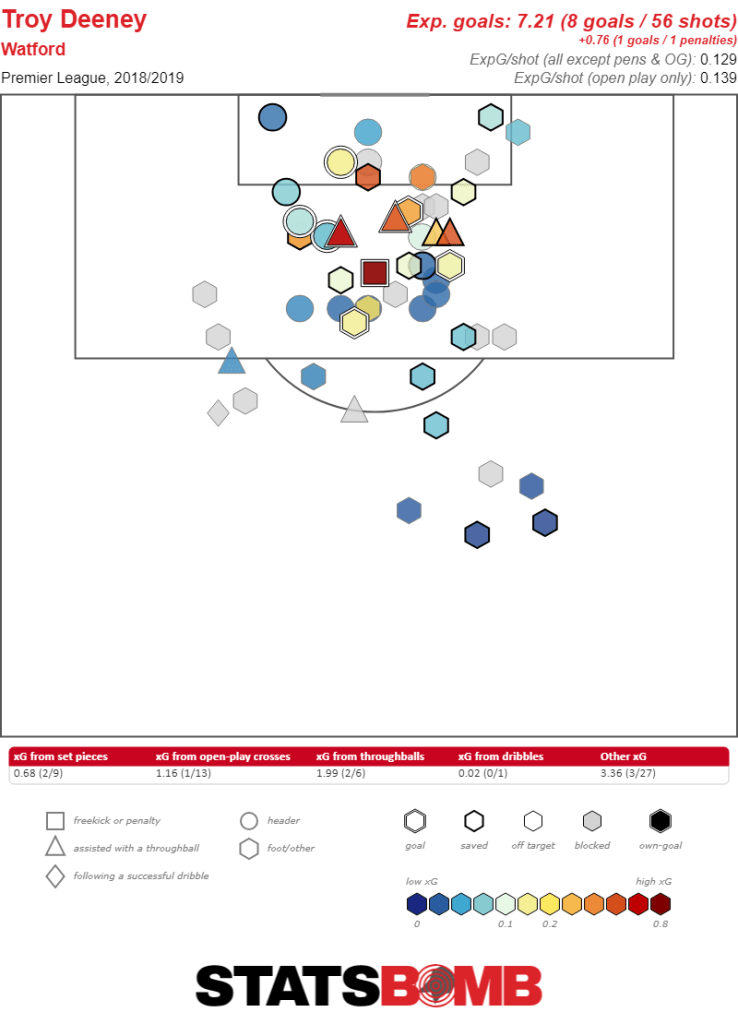

Calling Troy Deeney a fantastic aerial target actually undersells his dominance: Deeney’s amassed 5.06 aerial wins per 90 minutes this season, which is five times what the average striker produces. At the end of the 2017-18 season, it was not clear if he could combine that skill with meaningful scoring. “If a rumoured £15 million Cardiff bid for the decidedly washed up and exceedingly replaceable Troy Deeney actually materialized,” I wrote, “Watford would do well to take the money.” Oops! While not prolific, Deeney’s scored a credible 8 non-penalty goals on 7.21 expected goals so far this season.

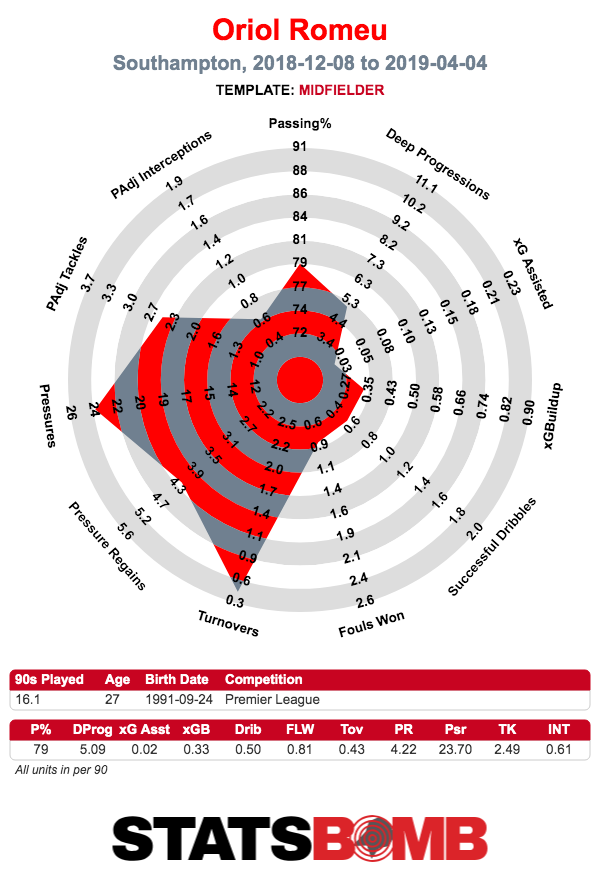

If all of this sounds like a roundabout way of saying Watford’s midfield doesn’t offer much build-up play, that’s because it is. (One could say this article, in homage to Watford, bypassed the midfield.) Abdoulaye Doucouré leads Watford midfielders in open-play expected goals assisted with 3.22 over the entire season. That is not to say the midfield is without value; it defends and presses and chips in a few goals here and there. Doucoure, Etienne Capoue, Roberto Pereyra and WIll Hughes are the sorts of useful-but-limited players who thrive in these roles. “None of this screams “Shock Title Winner!,’” I wrote before the season, “but you can see something functional being pieced together with this squad.” That is largely what has come to pass.

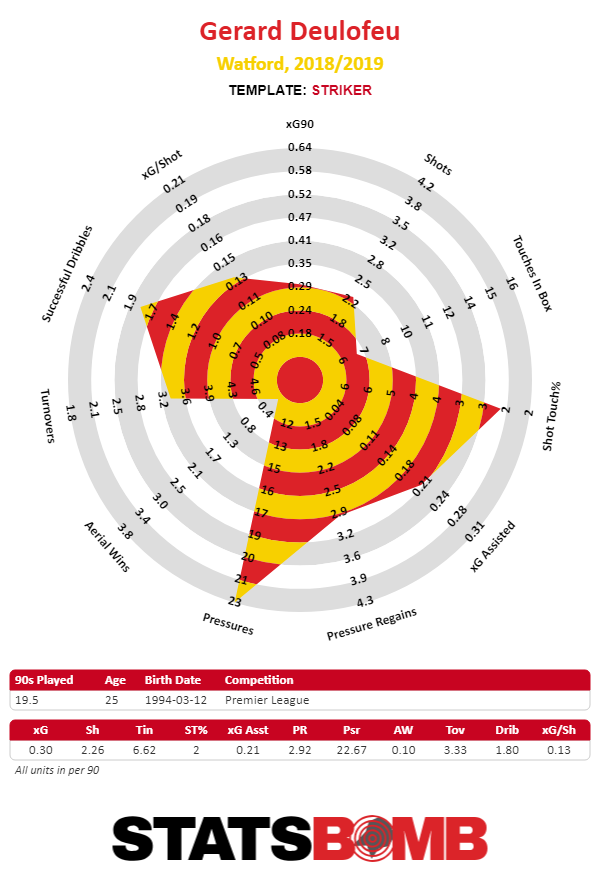

That prediction may have held up, but here’s one that didn’t: “In 2018, one can safely say Gerard Deulofeu is not the answer.” Oops again?

A subset of Watford fans, from whom I will surely and deservedly be hearing, took umbrage at this description of a very talented player. My riposte was that Deulofeu, while talented, rarely translated his skills into extended periods of production. He also had a tendency of falling out of favour at clubs after a hot start — only he hadn’t even conjured a hot start at Watford as a loanee in 2017-18. To Watford and Deulofeu’s credit, both of those problems appear to have been addressed.

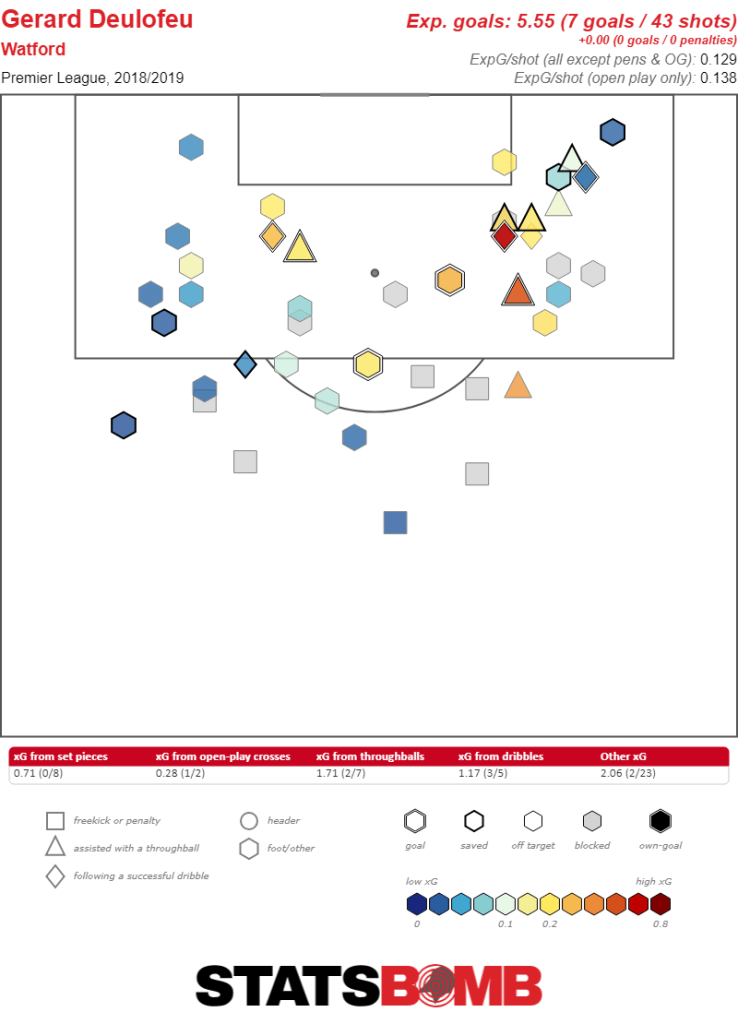

There are two ways of thinking about what’s happened this year. Some of the change has been tactical. As a loanee, Deulofeu took — and failed to convert — low-value shots from distance or wide angles. This season, he’s been deployed as more of a second striker, with the effect that he takes more shots and takes them from more productive positions. Free kicks notwithstanding, he’s taking nearly 80% of his shots inside the box. The new role, where he starts wide but moves centrally, combines his winger-ish dribbling and pressing abilities with a decent scoring return.

Deulofeu’s change has also been temperamental. For whatever reason, he’s tended to start brightly at clubs and then fall out of favour. That has not happened at Watford. Last season, it looked like they weren’t even getting his new club grace period. Now we must consider the possibility that Deulofeu, like Marko Arnautovic a few years ago, is simply a flighty player stabilizing in his mid-20s. If Gracia has unlocked Deulofeu’s potential, both tactically and temperamentally, Watford is in good shape going forward.

There are still reasons for caution with Deulofeu. He’s scored 1.5 more goals than expected. Moreover, he could still have yet another falling out; the sample size is not yet large enough to outweigh his priors. But the signs are promising, and Deulofeu has helped fill in for Richarlison’s lost production.

Deulofeu fills out a squad has plenty of useful-if-not-great players. (Maybe one day the promising-on-paper Andre Gray will be more than a super-sub.) Javi Gracia is a good manager who can deploy those players to considerable effect. In that respect, the Watford story is an object lesson in what it means to be “league average” in the current Premier League. The club is about league average in a wide range of measures, but that puts it in a position to finish between 10th and 7th. Mean and median aren’t the same thing. The superclubs pull up the averages, Fulham and Huddersfield drag it down, and when the dust settles, a smart club that is “average” can be in the top half with a chance of winning a cup. Watford’s floor never appeared to be low. This season, the club has made the case for having a modestly high ceiling.

Header image courtesy of the Press Association