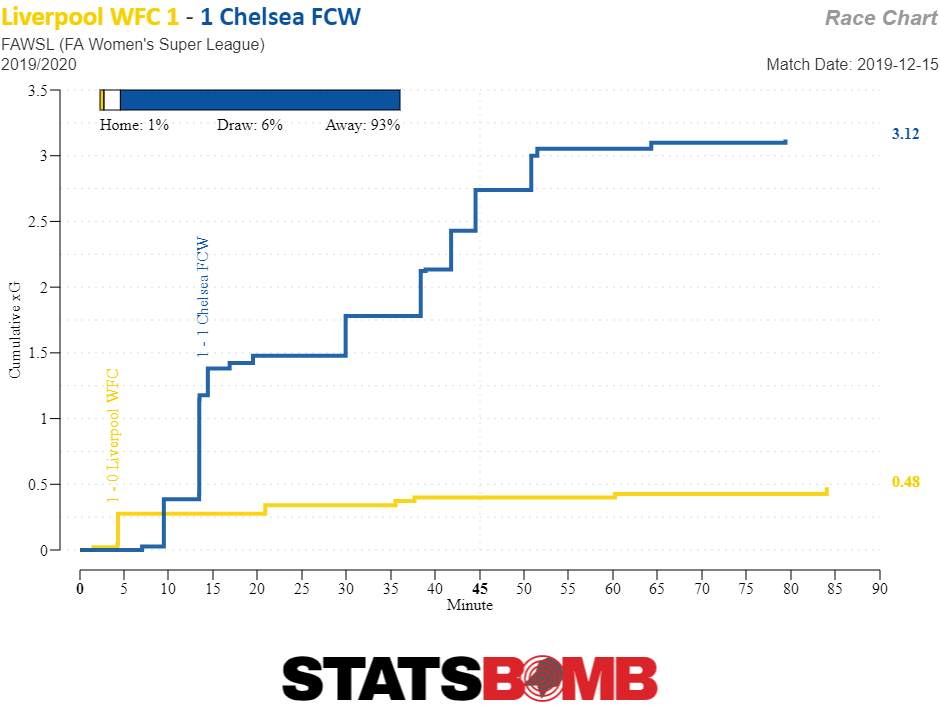

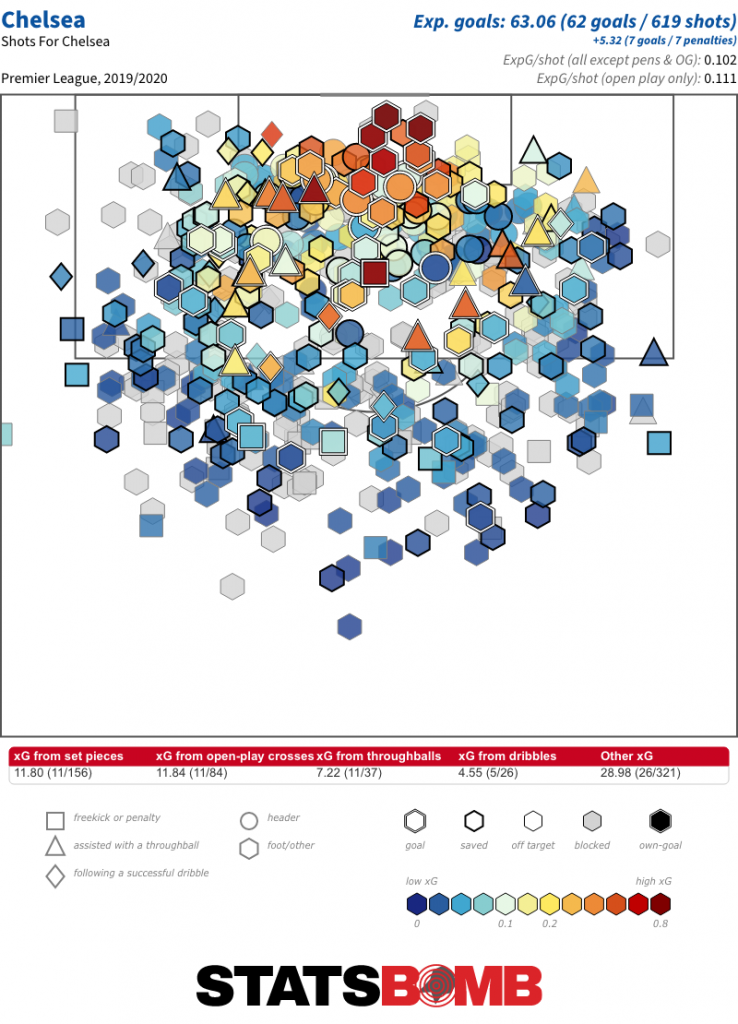

Thor is only supposed to need one hammer. Voltron never needed a second blazing sword. And Chelsea Women FC’s attack wasn’t supposed to need Sam Kerr. When Kerr was announced as a Chelsea player on November 13, the blue Londoners sat at the top of the league with zero losses, just one draw, and had also already defeated last year’s champions, Arsenal. The signing of one of the world’s best strikers at the time read more as villainy than necessity, as Chelsea was thought to have the firepower they needed to recover from a disappointing 2018–19 season. But after a brilliant first half of the season, it appears they might actually need Sam Kerr to secure a better finish. In the first half of the season, Chelsea topped the league table for months, took all three points from both of their title rivals (Arsenal and Manchester City), didn’t lose a match, and even messed around and scored the goal of the season. But heading into the winter break, thanks to first a 1-1 draw against Brighton and then, later, and identical result versus Liverpool (who sat at the bottom of the table at the time), Chelsea ended 2019 in third place. The Blues have a match with Everton to make up, but even assuming they secure those three points, Chelsea would still only reach second. Now, that draw against Liverpool wasn't exactly an accurate representation of the underlying play, but they don't give you points for playing well and not scoring. So the fact that Chelsea doubled up Liverpool on shots, 18–9 and piled on the expected goals, 3.12–0.48 doesn't award them any points.  Chelsea are the only team without a loss — Arsenal’s only loss is to Chelsea while Manchester City’s two losses are to Arsenal and Chelsea — yet two draws against lesser competition ensure they will likely have to beat both rivals again in 2020. The good news is that their performances show no signs of dipping. Their xG difference is just as strong as it's ever been.

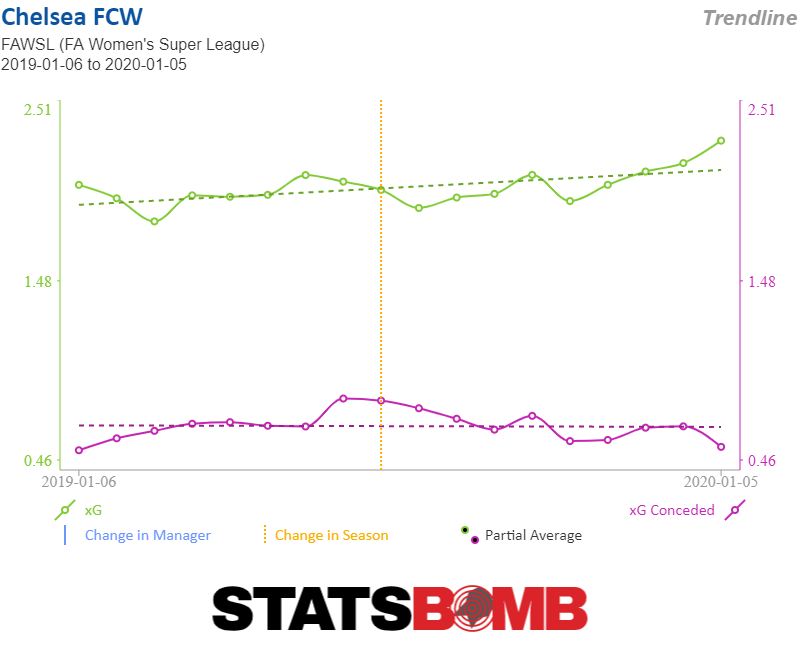

Chelsea are the only team without a loss — Arsenal’s only loss is to Chelsea while Manchester City’s two losses are to Arsenal and Chelsea — yet two draws against lesser competition ensure they will likely have to beat both rivals again in 2020. The good news is that their performances show no signs of dipping. Their xG difference is just as strong as it's ever been.  Despite Chelsea’s first-half dominance, their margin for error is already gone, and for an attack that's mostly been humming on right at expectation, the Liverpool match sure was an inopportune time to forget how to put the ball in the back of the net.

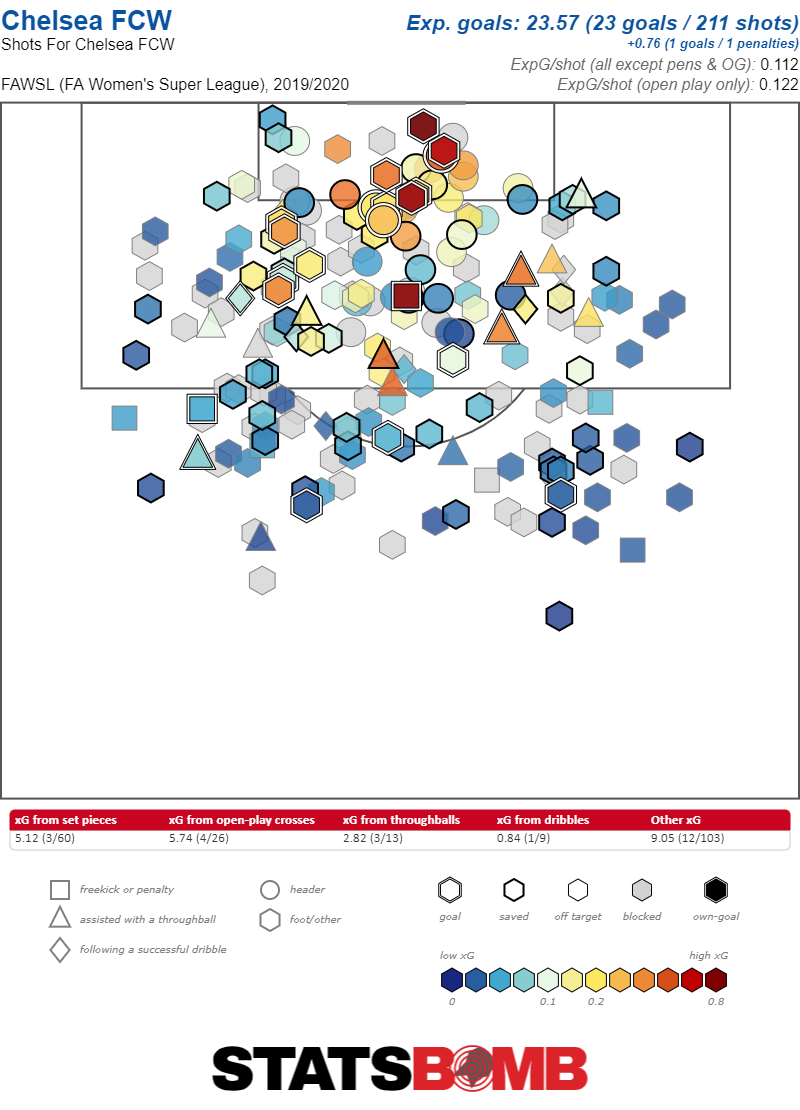

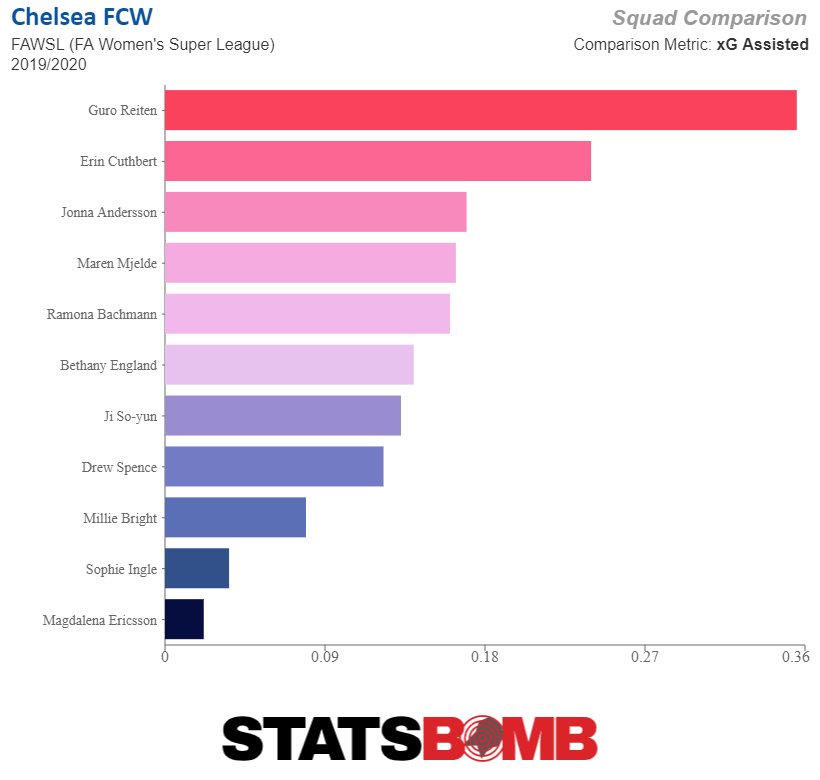

Despite Chelsea’s first-half dominance, their margin for error is already gone, and for an attack that's mostly been humming on right at expectation, the Liverpool match sure was an inopportune time to forget how to put the ball in the back of the net.  Then there's the question of whether or not being equal to their xG is good enough. At the break, Chelsea (19.6), Manchester City (19.4) and Arsenal (21.3) had the highest expected goals numbers in the league. Of the three, Chelsea had the lowest goal output at 21, while Manchester City had scored 24 and Arsenal 29. It sounds silly to state that a team should expect to significantly outperform its xG, but that’s where Chelsea are being let down. Arsenal’s 29 goals were not only eight more than Chelsea, the tally was 7.7 above the Gunners’ expected output. City are 4.6 above theirs, but Chelsea were nearly level with their xG, with only a 1.4 difference, a small difference which evaporated in their first game back after the break. The broad default assumption about xG is that all teams should, eventually, return to their expected levels. But, in a league with wide gulfs in talent, it's perfectly reasonable to suspect that the dominant teams have some wiggle room, and that being at expectation isn't good enough. By xG Chelsea have had the most potent attack, and in situations with more evenly distributed talent it would be right to assume that eventually Arsenal and City would have to come back down to earth. In this league, though, Chelsea might just have to run them down. Chelsea's biggest problem is they lack consistent goalscoring — in some cases, any goalscoring at all — from the side's star players. In the first half of the season, forward Bethany England led the team with six goals and three assists, but no other attackers came close. Midfielders Ji So-yun and Drew Spence had three, while winger Guro Reiten also had three (but two came in one match and she hadn’t scored since September). Erin Cuthbert, whose eight goals and six assists saw her named Chelsea’s Player of the Year in 2018–19, ended the first half of the season with no goals and just one assist. Ramona Bachmann — who filled in at the #10 role for the injured Fran Kirby — also has no goals and just one assist. To put it in even sharper perspective, Kirby, who has started just two matches and made two substitute appearances, was tied with Bethany England for the most assists on the team. However, at least part of that is down to bad luck on Reiten's part, as she leads the team in xG assisted per 90 minutes.

Then there's the question of whether or not being equal to their xG is good enough. At the break, Chelsea (19.6), Manchester City (19.4) and Arsenal (21.3) had the highest expected goals numbers in the league. Of the three, Chelsea had the lowest goal output at 21, while Manchester City had scored 24 and Arsenal 29. It sounds silly to state that a team should expect to significantly outperform its xG, but that’s where Chelsea are being let down. Arsenal’s 29 goals were not only eight more than Chelsea, the tally was 7.7 above the Gunners’ expected output. City are 4.6 above theirs, but Chelsea were nearly level with their xG, with only a 1.4 difference, a small difference which evaporated in their first game back after the break. The broad default assumption about xG is that all teams should, eventually, return to their expected levels. But, in a league with wide gulfs in talent, it's perfectly reasonable to suspect that the dominant teams have some wiggle room, and that being at expectation isn't good enough. By xG Chelsea have had the most potent attack, and in situations with more evenly distributed talent it would be right to assume that eventually Arsenal and City would have to come back down to earth. In this league, though, Chelsea might just have to run them down. Chelsea's biggest problem is they lack consistent goalscoring — in some cases, any goalscoring at all — from the side's star players. In the first half of the season, forward Bethany England led the team with six goals and three assists, but no other attackers came close. Midfielders Ji So-yun and Drew Spence had three, while winger Guro Reiten also had three (but two came in one match and she hadn’t scored since September). Erin Cuthbert, whose eight goals and six assists saw her named Chelsea’s Player of the Year in 2018–19, ended the first half of the season with no goals and just one assist. Ramona Bachmann — who filled in at the #10 role for the injured Fran Kirby — also has no goals and just one assist. To put it in even sharper perspective, Kirby, who has started just two matches and made two substitute appearances, was tied with Bethany England for the most assists on the team. However, at least part of that is down to bad luck on Reiten's part, as she leads the team in xG assisted per 90 minutes.  Adding to the frustration is that the Blues frequently dominated possession, won shot battles, led all teams in shots (20.22; Arsenal was second with 16.5) and shots on target (7.67; Manchester City second with 6.0) per 90, and kept opponents away from their net, conceding both the fewest shots, 8, and the lowest xG per match, 0.53, in the league. Looking at the top line numbers, Chelsea also only conceded five goals in the first half of the season; only City conceded fewer. Chelsea still needed someone — anyone — to start sticking the ball into the back of the net. But they didn’t just get anyone; they got Sam Kerr. Kerr was the NWSL’s leading scorer for the past three consecutive seasons and topped her best-ever output in her final season, with 18 goals in 21 games — and that’s with missing 3 games due to the World Cup (the Chicago Red Stars lost all 3). Yet, the lasting image of Kerr for her now-former team came in the championship match against the North Carolina Courage. Starved for service, the Australian forward shouted at teammate Savannah McCaskill after failing — certainly not for the first time — to feed the ball to Kerr after she’d made a run. With Chelsea, this is unlikely to be a problem. Chelsea manager Emma Hayes will have to rework the lineup to keep Beth England on the pitch along with Sam Kerr, which likely means sacrificing one of the wingers, Reiten or Cuthbert. England has been far too good to drop, and her team-leading three assists show her eye for setting up chances and her willingness to be unselfish if a teammate is in a better scoring position. England can also shoot from range, and is clever at shuttling the ball around in the final third until space to exploit opens up. The partnership between the two could be the thing Chelsea need to continue their dominance, and this time make it count. Kerr would be a monumental addition to any of Europe’s best teams, but Chelsea had misfired themselves into the precarious position of actually needing a player of her caliber. Kerr’s 76-minute debut underscores it all: drawing a red card in the first twenty minutes (not many things help your team more than the other team losing a player), assisting Beth England with a backheel, being directly involved in Reiten scoring her first league goal since September and indirectly involved in Erin Cuthbert netting her first. In the first half of the season, Chelsea did everything but find the extra goals that dominant teams find, goals that their competitors were finding. For a team that has yet to lose and has already defeated the clubs above them, the difference between further disappointment and getting what they feel they deserve might just be the signing of a player they shouldn’t need. Though you have to admit, Thor would look even more badass with two hammers. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

Adding to the frustration is that the Blues frequently dominated possession, won shot battles, led all teams in shots (20.22; Arsenal was second with 16.5) and shots on target (7.67; Manchester City second with 6.0) per 90, and kept opponents away from their net, conceding both the fewest shots, 8, and the lowest xG per match, 0.53, in the league. Looking at the top line numbers, Chelsea also only conceded five goals in the first half of the season; only City conceded fewer. Chelsea still needed someone — anyone — to start sticking the ball into the back of the net. But they didn’t just get anyone; they got Sam Kerr. Kerr was the NWSL’s leading scorer for the past three consecutive seasons and topped her best-ever output in her final season, with 18 goals in 21 games — and that’s with missing 3 games due to the World Cup (the Chicago Red Stars lost all 3). Yet, the lasting image of Kerr for her now-former team came in the championship match against the North Carolina Courage. Starved for service, the Australian forward shouted at teammate Savannah McCaskill after failing — certainly not for the first time — to feed the ball to Kerr after she’d made a run. With Chelsea, this is unlikely to be a problem. Chelsea manager Emma Hayes will have to rework the lineup to keep Beth England on the pitch along with Sam Kerr, which likely means sacrificing one of the wingers, Reiten or Cuthbert. England has been far too good to drop, and her team-leading three assists show her eye for setting up chances and her willingness to be unselfish if a teammate is in a better scoring position. England can also shoot from range, and is clever at shuttling the ball around in the final third until space to exploit opens up. The partnership between the two could be the thing Chelsea need to continue their dominance, and this time make it count. Kerr would be a monumental addition to any of Europe’s best teams, but Chelsea had misfired themselves into the precarious position of actually needing a player of her caliber. Kerr’s 76-minute debut underscores it all: drawing a red card in the first twenty minutes (not many things help your team more than the other team losing a player), assisting Beth England with a backheel, being directly involved in Reiten scoring her first league goal since September and indirectly involved in Erin Cuthbert netting her first. In the first half of the season, Chelsea did everything but find the extra goals that dominant teams find, goals that their competitors were finding. For a team that has yet to lose and has already defeated the clubs above them, the difference between further disappointment and getting what they feel they deserve might just be the signing of a player they shouldn’t need. Though you have to admit, Thor would look even more badass with two hammers. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

Month: January 2020

Keepers take center stage at the top of La Liga

Spanish football seems to be losing its hold over the rest of European football. For five years running, a La Liga club won the Champions League. Liverpool's win over Spurs severed that streak . . . in Madrid of all places. Atlético Madrid, Barcelona and Real Madrid were eliminated from the competition in a variety of embarrassing ways. Ajax humiliated Real Madrid at the Bernabéu with Sergio Ramos watching from the stands after picking up a yellow card on purpose to ‘clear the slate’ for games deeper into the competition. Atético Madrid lost 3-0 to Juventus without getting a shot on target despite taking a two-goal lead to Turin. And Barcelona were hijacked by Liverpool at Anfield in a historic collapse by the Spanish side. At the midway point to the season, these are the clubs filling the top three slots in La Liga, but not one has made a truly convincing start. Yet as their respective attacks wane, these three boast salacious amounts of talent at one position. I argue that the first, second and third best goalkeepers in the world are playing in La Liga. Aside from Allisson at Liverpool, there are rarely any other names thrown into the hat when talking about the world’s best. Marc-André ter Stegen, Thibaut Courtois and Jan Oblak are the crème de la crème of glovemen. Who’s better? Who will win the Zamora trophy — the award given to the best keeper in La Liga based on goals conceded — and how important are they to their teams? Goalkeepers don’t always rise to fulfil the best of their traits but fall to the weaknesses of their team’s defensive frailties. As the last line of defence, they are handy scapegoats when things go wrong. Interpreting a goalkeeper’s form can be like interpreting Talmudic texts but with Courtois, Oblak and ter Stegen it's easy to see these are three very effective goalkeepers.

Thibaut Courtois

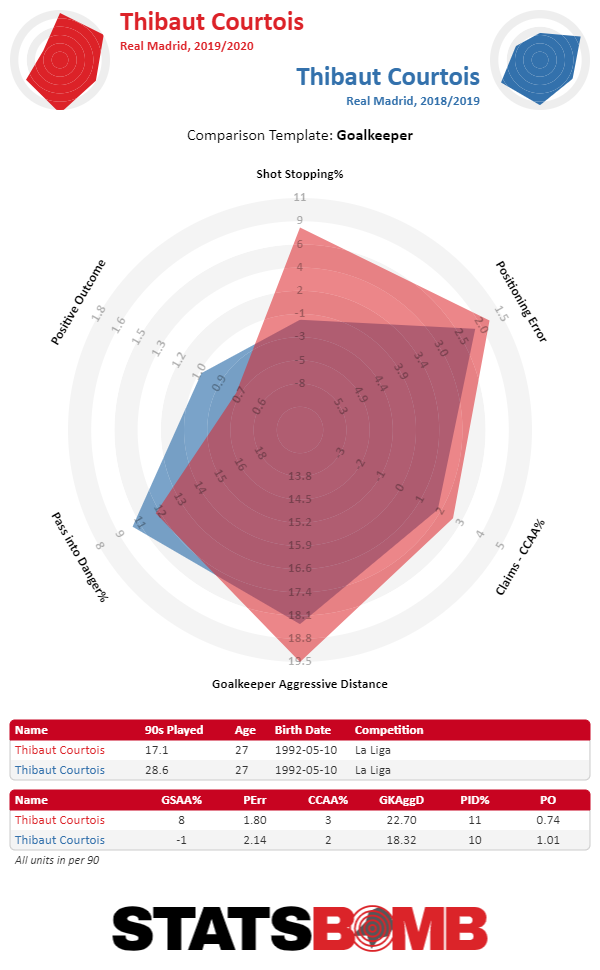

Courtois’s time at Real Madrid couldn’t have gotten off to a rockier start. There was the debacle over Keylor Navas, the three-time Champions League-winning goalkeeper, and Zinedine Zidane’s allegiance to him. There was also a supposed bout of anxiety during a game against Brugge early in the season the team explained away as stomach problems. He conceded six goals in his first four games in the league, along with three against PSG. Alphonse Areola, considered a mere placeholder, was set to take over at one point. All of that was compounded by Real Madrid’s leaky and vulnerable defence. The upswing in their form can be attributed to Fede Valverde coming into the side more regularly. The midfielder's penchant for harassing opponents with the ball likely contributed to improved performance from key defenders as did the introduction of the far more robust and conscientious defender, Ferland Mendy, at left-back. With that group in front of him, Courtois looks like the world-class goalkeeper Madrid thought they had signed. In fact, he looks even better than any previous version of himself.  Compared to last year, his shot-stopping is up, his aggression as more of a sweeper is increasing and his claims percentage is rising. One area of his game that Courtois needed to improve was his aggressiveness coming off the line, and he has. He is now the most aggressive goalkeeper in La Liga when coming off his line to perform defensive actions outside his penalty area at 22.70 metres. He’s not peak Manuel Neuer in possession or when attempting to sweep up, but he looks much better. With his confidence back, he might just become the galáctico Madrid tried to sign in 2018 and even be the difference when it comes to deciding the La Liga title this season.

Compared to last year, his shot-stopping is up, his aggression as more of a sweeper is increasing and his claims percentage is rising. One area of his game that Courtois needed to improve was his aggressiveness coming off the line, and he has. He is now the most aggressive goalkeeper in La Liga when coming off his line to perform defensive actions outside his penalty area at 22.70 metres. He’s not peak Manuel Neuer in possession or when attempting to sweep up, but he looks much better. With his confidence back, he might just become the galáctico Madrid tried to sign in 2018 and even be the difference when it comes to deciding the La Liga title this season.

Jan Oblak

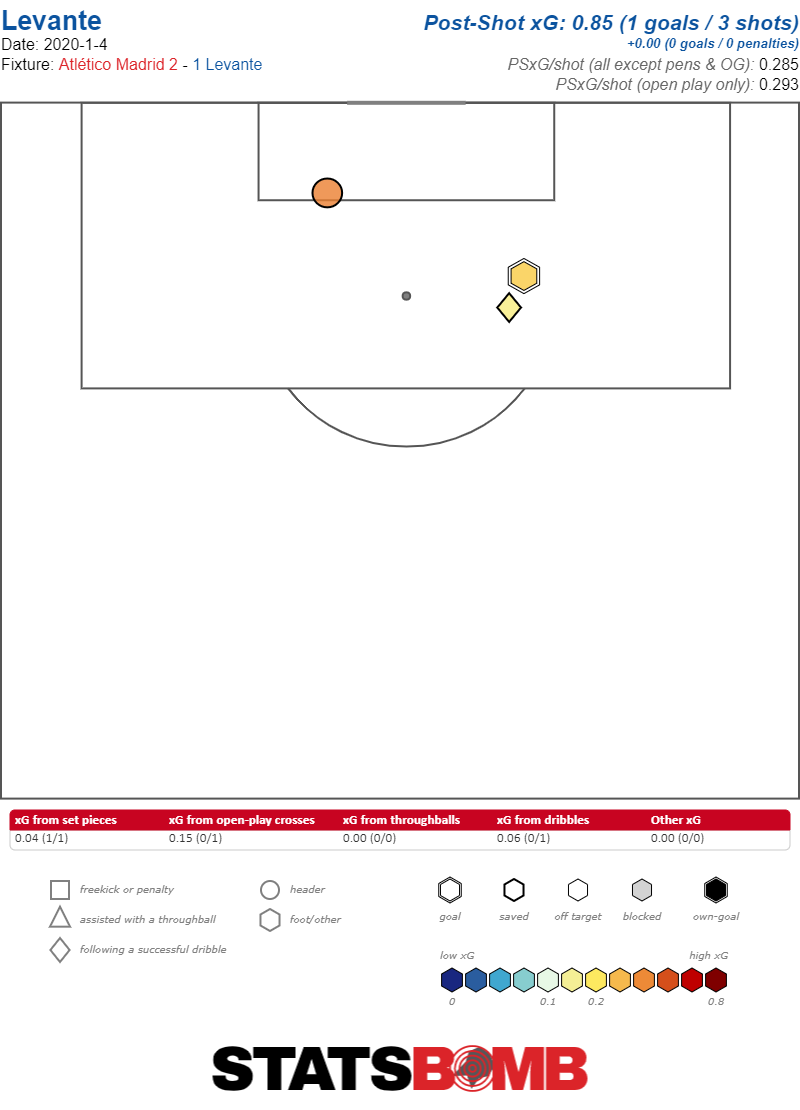

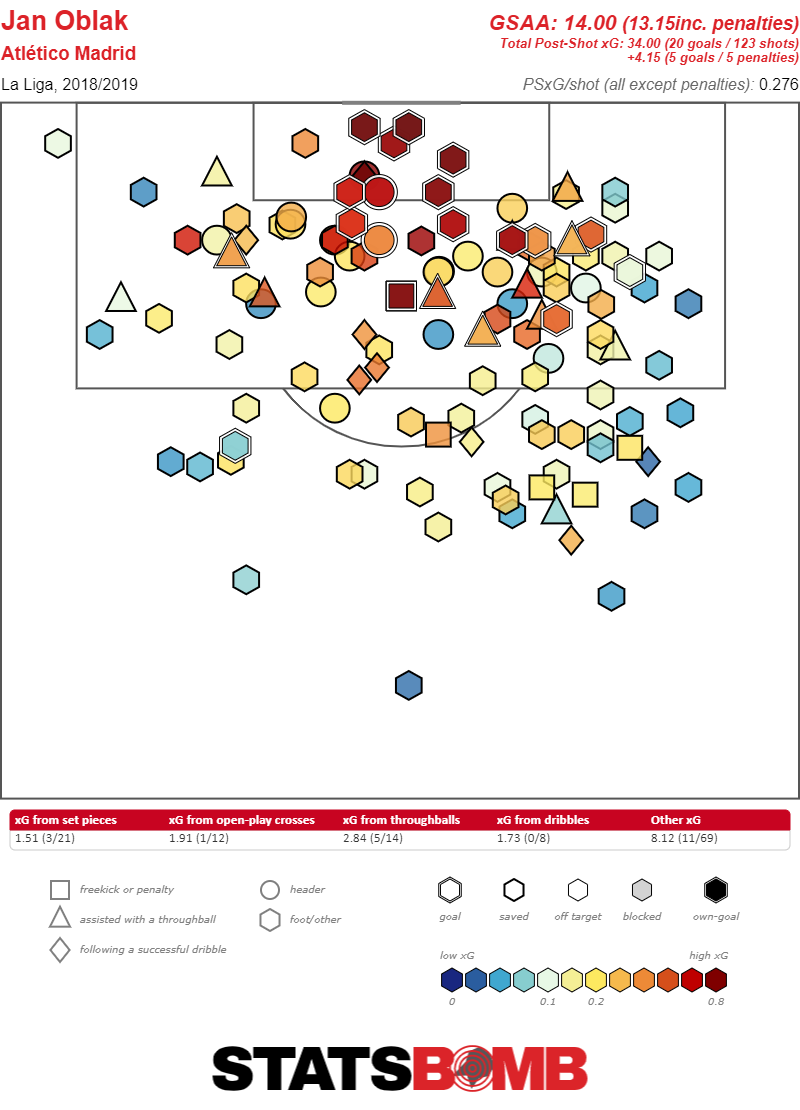

There is something mythical about Jan Oblak. He’s a cross between a man mountain and an octopus, doesn’t get as many headlines as he should and, despite his stoic exterior, pulls off the seemingly miraculous on a weekly basis. There are times when his goal seems impregnable. Compared to the other two, he appears to have a disproportionate amount of incredible saves, possibly due to an arm that seems to extend beyond the natural limits of the human body and reflexes that a cat would envy. And he seems to make these saves in clusters. Against Levante at the weekend, Paco Lopez described Oblak as “probably the best in the world” after he denied them the equalizer twice. Roger, the man he denied for the second, said “Oblak made two wonderful saves” and Simeone chimed in with “for us, he is the best in the world” while admitting Oblak saved their bacon. Interestingly, while Oblak's saves were no doubt impressive, they were not perhaps as decisive to the game as its participants felt them to be.  Atlético Madrid are in a period of transition into a more attacking side. And so Oblak’s numbers are down from his normal other-worldly self. He finished last year with 14 goals saved above average; no one else had more than 9. As such, the fact that he's currently below water with -1.82 goals scored above average more likely reflects a rough patch than a serious sign of concern. Plus, he's still conceding just 0.51 goals per 90, the best in the league for players with at least 600 minutes. His save percentage, 84, and his shot-stopping percentage, 11, remains the best in the league. All of which is to say that even in a down year, when Atleti are trying to be more attacking, Oblak still gets the benefit of playing behind a uniquely stellar defence that allows largely weak shots at goal. As Oblak has won the Zamora trophy three years in a row, his brilliance has become almost mundane in its consistency. Yet the club recognises it, signing the keeper to a new deal until 2023 with a release clause of €120 million. For as long as he is at Atletico Madrid, he will be a target for other teams and a threat to leave. Clubs have circled in the past but Simeone continues to keep them at bay. Allison was a key figure in turning Liverpool into Europe’s best team and Jan Oblak could certainly tip the scales for another club in need of help at the position. Especially if he can manage to get something even close to last season's Oblak; seriously, look at that radar.

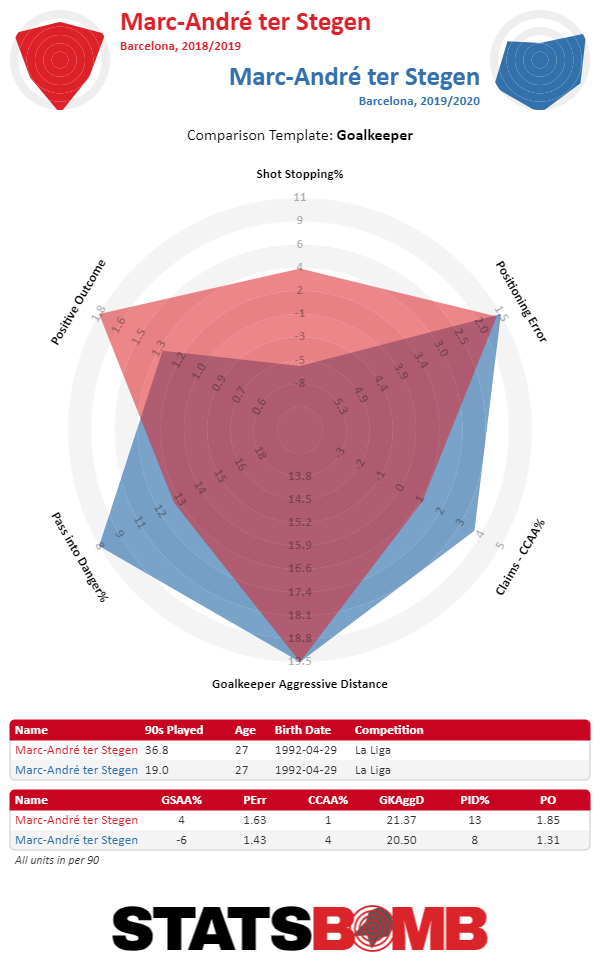

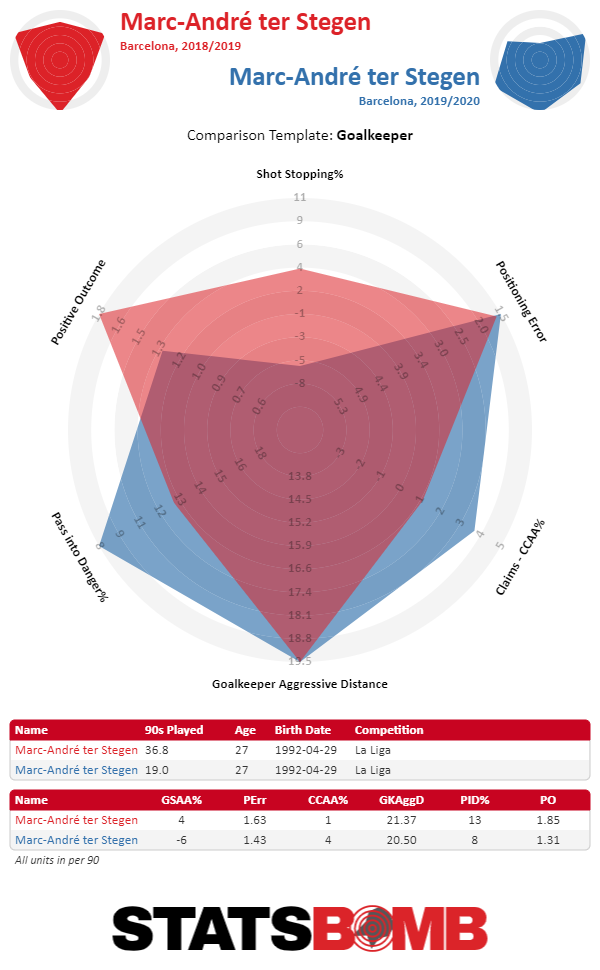

Atlético Madrid are in a period of transition into a more attacking side. And so Oblak’s numbers are down from his normal other-worldly self. He finished last year with 14 goals saved above average; no one else had more than 9. As such, the fact that he's currently below water with -1.82 goals scored above average more likely reflects a rough patch than a serious sign of concern. Plus, he's still conceding just 0.51 goals per 90, the best in the league for players with at least 600 minutes. His save percentage, 84, and his shot-stopping percentage, 11, remains the best in the league. All of which is to say that even in a down year, when Atleti are trying to be more attacking, Oblak still gets the benefit of playing behind a uniquely stellar defence that allows largely weak shots at goal. As Oblak has won the Zamora trophy three years in a row, his brilliance has become almost mundane in its consistency. Yet the club recognises it, signing the keeper to a new deal until 2023 with a release clause of €120 million. For as long as he is at Atletico Madrid, he will be a target for other teams and a threat to leave. Clubs have circled in the past but Simeone continues to keep them at bay. Allison was a key figure in turning Liverpool into Europe’s best team and Jan Oblak could certainly tip the scales for another club in need of help at the position. Especially if he can manage to get something even close to last season's Oblak; seriously, look at that radar.  Marc-André ter Stegen Ter Stegen hasn’t had the best of years but remains a world class goalkeeper. Such is his role, that of a true sweeper-keeper, there tends to be more variance in his performances. If Oblak is a wall at one end of the scale and Courtois is in the middle, excelling at claiming crosses, shot-stopping and a little bit of passing then their German colleague is at the far end of the scale – he has the body of a goalkeeper and the brain of a central midfielder.

Marc-André ter Stegen Ter Stegen hasn’t had the best of years but remains a world class goalkeeper. Such is his role, that of a true sweeper-keeper, there tends to be more variance in his performances. If Oblak is a wall at one end of the scale and Courtois is in the middle, excelling at claiming crosses, shot-stopping and a little bit of passing then their German colleague is at the far end of the scale – he has the body of a goalkeeper and the brain of a central midfielder.  Whatever Ter Stegen lacks in shot-stopping prowess, and that isn’t to suggest he lacks much, he can make up for it with his feet. He is an ice-man when it comes to inviting opponents to press him before he springs a defender and gives his side numerical superiority as they build from the back. He passes the ball to teammates in danger positions just 8% of the time, which is almost half the league average of 15%. He is unflappable and has two assists this season. Given he has the lowest launch percentage in the league, the long passes he does make tend to be laser beams. Ter Stegen’s season to date, much like his Barcelona’s teammates, has been mixed. It hasn’t been helped by the fact that Jordi Alba has spent a lot of time on the sideline through injury and his replacement, Junior Firpo, has taken time to adjust. Clement Lenglet, who swooped in and stole Samuel Umtiti’s job from him looks vulnerable and could be handing his compatriot back his role if he doesn’t improve. The number of passes Ter Stegen launches out from the back (not counting goal kicks) is the lowest in the league at 24.3, followed closely by Courtois. The German acts like another outfield player and despite his shot-stopping ability falling off this season, his worth is made up in what he offers in the passing game. His passing percentage, 86, is the best in the league for keepers too. Who is the best goalkeeper in the league? It depends on what you’re asking your keepers to do. Each keeper mentioned has different skill sets but all of them are 27, most likely have at least some of their best years ahead of them and play for three of the best teams in the world. Cristiano is gone and Lionel Messi can’t continue to set the standard forever. But they have three of the world’s best keepers to hold down the fort until the next generation of elite attackers arrives in La Liga.

Whatever Ter Stegen lacks in shot-stopping prowess, and that isn’t to suggest he lacks much, he can make up for it with his feet. He is an ice-man when it comes to inviting opponents to press him before he springs a defender and gives his side numerical superiority as they build from the back. He passes the ball to teammates in danger positions just 8% of the time, which is almost half the league average of 15%. He is unflappable and has two assists this season. Given he has the lowest launch percentage in the league, the long passes he does make tend to be laser beams. Ter Stegen’s season to date, much like his Barcelona’s teammates, has been mixed. It hasn’t been helped by the fact that Jordi Alba has spent a lot of time on the sideline through injury and his replacement, Junior Firpo, has taken time to adjust. Clement Lenglet, who swooped in and stole Samuel Umtiti’s job from him looks vulnerable and could be handing his compatriot back his role if he doesn’t improve. The number of passes Ter Stegen launches out from the back (not counting goal kicks) is the lowest in the league at 24.3, followed closely by Courtois. The German acts like another outfield player and despite his shot-stopping ability falling off this season, his worth is made up in what he offers in the passing game. His passing percentage, 86, is the best in the league for keepers too. Who is the best goalkeeper in the league? It depends on what you’re asking your keepers to do. Each keeper mentioned has different skill sets but all of them are 27, most likely have at least some of their best years ahead of them and play for three of the best teams in the world. Cristiano is gone and Lionel Messi can’t continue to set the standard forever. But they have three of the world’s best keepers to hold down the fort until the next generation of elite attackers arrives in La Liga.

Five Premier League Teams’ Transfer Needs This Month

Let’s see if we can point a few clubs in the right direction. The January transfer window is upon us, which means that at least one club is likely to do something very stupid. Recruitment is hard, and doing it well involves a lot of factors, of which statistical analysis is just one. Nonetheless, what we can do with the numbers is identify teams’ obvious weaknesses in their current squads, and point to the sorts of things they should be looking for in new signings this month. Let’s take a look at five Premier League clubs.

Manchester United: someone not named Paul Pogba who can move the ball forward

For all the noise, Manchester United are a thoroughly ok football team. Defensively, they are sound, putting up numbers all but level with Liverpool in terms of expected goals conceded per game.  It’s at the other end where things are less interesting, with their 1.26 xG per game just a hair above league average. The problem might be in the construction of the squad. The attack is built around Marcus Rashford, Anthony Martial, Daniel James and frequently Jesse Lingard. All offer speed running in behind, and United can pose great problems to teams on the break, but there is little imagination when the game is played in front of them. The midfield options of Scott McTominay, Fred, Andreas Pereira and Nemanja Matić provide a fair amount of industry but little guile. The only person in the squad who really possesses the creative passing needed to break down teams is Paul Pogba. In his limited minutes this season, Pogba leads United in both deep progressions and open play passes into the box per 90. When he’s on the pitch, he is how Ole Gunnar Solskjær’s team move the ball forward. Even if Pogba was expected to start regularly for United for the next decade, they need more creative passers. As it is, with all sorts of noise about an exit and the possibility that he just won’t play much more football at Old Trafford, they’re desperate. What's less important is who this comes from. United could bring in a classic number ten, or a deeper-lying playmaker, or a wide midfielder who can influence the game. They just need someone, anyone, who can break teams down.

It’s at the other end where things are less interesting, with their 1.26 xG per game just a hair above league average. The problem might be in the construction of the squad. The attack is built around Marcus Rashford, Anthony Martial, Daniel James and frequently Jesse Lingard. All offer speed running in behind, and United can pose great problems to teams on the break, but there is little imagination when the game is played in front of them. The midfield options of Scott McTominay, Fred, Andreas Pereira and Nemanja Matić provide a fair amount of industry but little guile. The only person in the squad who really possesses the creative passing needed to break down teams is Paul Pogba. In his limited minutes this season, Pogba leads United in both deep progressions and open play passes into the box per 90. When he’s on the pitch, he is how Ole Gunnar Solskjær’s team move the ball forward. Even if Pogba was expected to start regularly for United for the next decade, they need more creative passers. As it is, with all sorts of noise about an exit and the possibility that he just won’t play much more football at Old Trafford, they’re desperate. What's less important is who this comes from. United could bring in a classic number ten, or a deeper-lying playmaker, or a wide midfielder who can influence the game. They just need someone, anyone, who can break teams down.

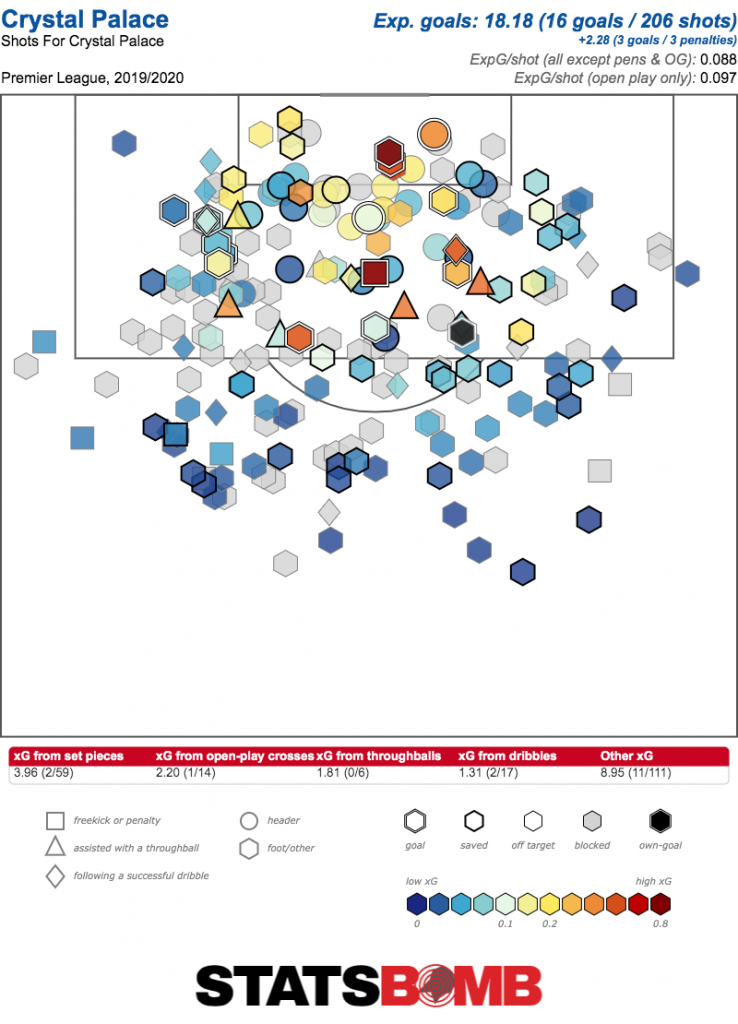

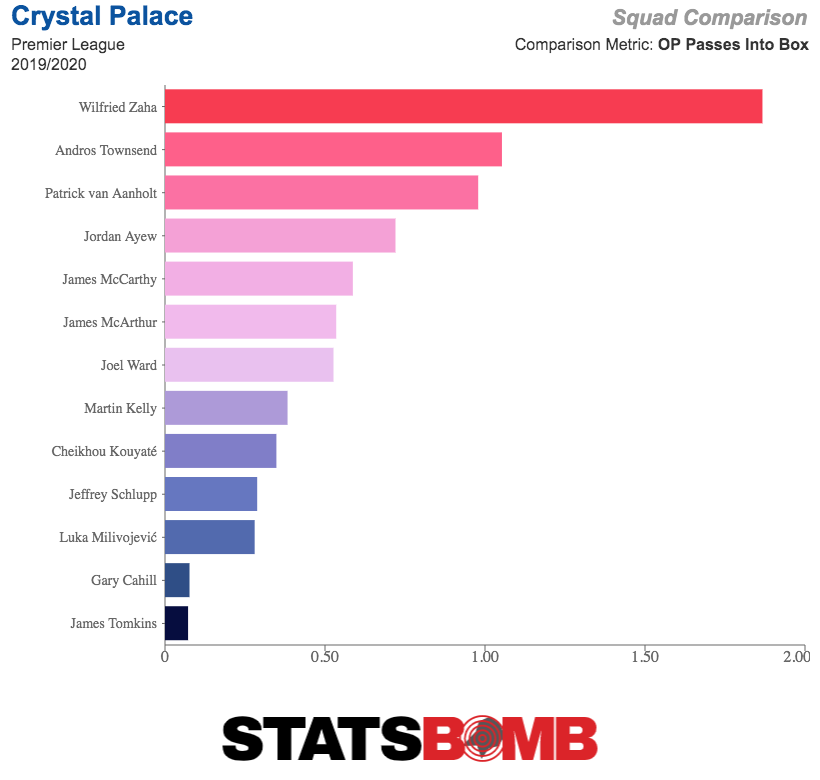

Crystal Palace: someone not named Wilfried Zaha who can move the ball forward

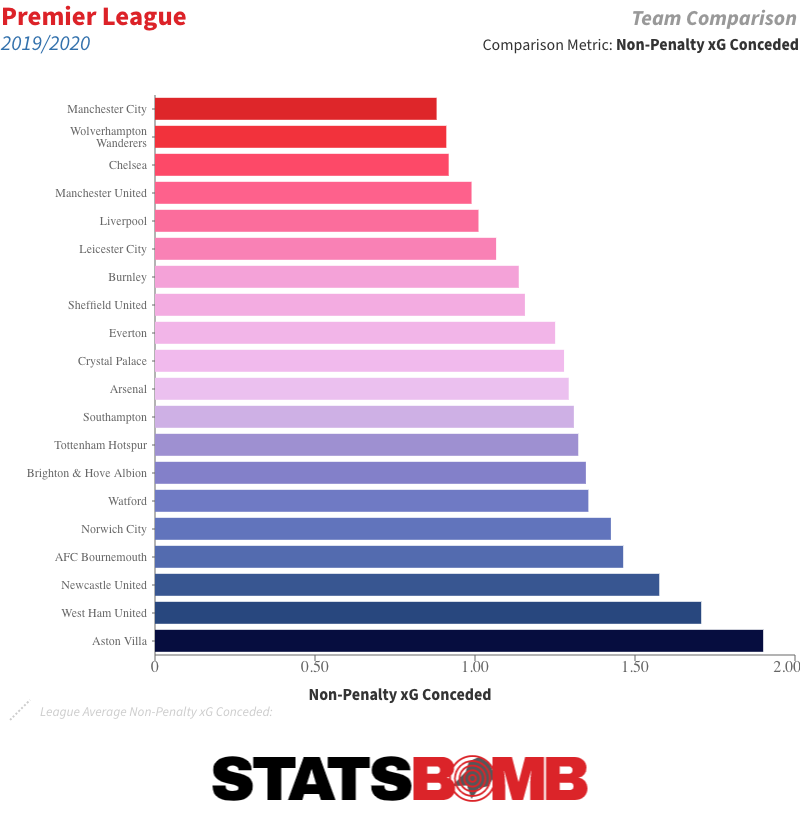

Crystal Palace have much of the same problem at a lower level. It sometimes seems like Roy Hodgson is physically incapable of turning out a side that doesn’t get the basics of defending right, and they’re putting up midtable numbers on that side of the ball. It’s the attack, though, where things look horrible. Palace’s 19 goals scored is the second-fewest in the top flight, and xG does them no favours, suggesting they’re right around where they should be.  There’s a real case to be made that Jordan Ayew isn’t good enough to be Palace’s first-choice striker. But I’d argue the bigger concern is that Palace don’t have anyone other than Wilfried Zaha to work the ball into dangerous areas. The Ivory Coast international is outdoing even Adama Traore in successful dribbles per 90, while leading Palace by a lot in open play passes into the box. Hodgson has done well teaching this side to keep a compact shape, making sure the spaces between the full-backs and centre-backs and all that good stuff is right, but in possession they have just one idea: give it to Wilf. Zaha might be forgiven for his few goals and assists when he has so much else to do.

There’s a real case to be made that Jordan Ayew isn’t good enough to be Palace’s first-choice striker. But I’d argue the bigger concern is that Palace don’t have anyone other than Wilfried Zaha to work the ball into dangerous areas. The Ivory Coast international is outdoing even Adama Traore in successful dribbles per 90, while leading Palace by a lot in open play passes into the box. Hodgson has done well teaching this side to keep a compact shape, making sure the spaces between the full-backs and centre-backs and all that good stuff is right, but in possession they have just one idea: give it to Wilf. Zaha might be forgiven for his few goals and assists when he has so much else to do.  Palace need to find a way to share the ball progression without breaking down Hodgson’s shape. Max Meyer could’ve fit the bill, but has been a big disappointment playing on the left of the midfield. As it is, the last time Palace really had this sort of option was during Ruben Loftus-Cheek’s loan in 2017–18. If someone of roughly his mould could be found, it should help Palace significantly in moving the ball into dangerous areas.

Palace need to find a way to share the ball progression without breaking down Hodgson’s shape. Max Meyer could’ve fit the bill, but has been a big disappointment playing on the left of the midfield. As it is, the last time Palace really had this sort of option was during Ruben Loftus-Cheek’s loan in 2017–18. If someone of roughly his mould could be found, it should help Palace significantly in moving the ball into dangerous areas.

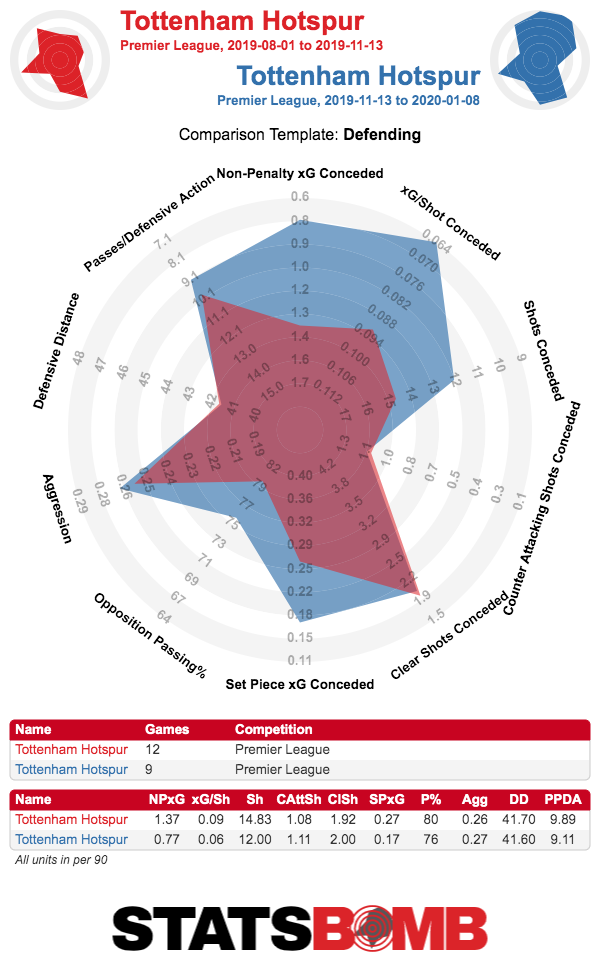

Tottenham Hotspur: a defensive midfielder

Perhaps the most surprising thing in the numbers about José Mourinho’s time at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium so far is that he seems to have built a solid defensive shell. They’ve managed to concede 11 non-penalty goals from 6.98 xG, but other than that, the numbers at that end are a stark improvement compared to the end of Mauricio Pochettino’s reign.  Mourinho has been able to do this without much of a functional midfield. Tensions between the two aside, Tanguy Ndombele has looked an exciting forward passer when on the pitch, and Mourinho has found roles for such players in the past. Of course, this has typically been alongside a robust holding midfielder, such as Matić partnering Cesc Fàbregas. With the current candidates for the number six role consisting of Harry Winks, who offers calm passing and little presence in front of the back four, and Eric Dier, whose physical limitations seem increasingly insurmountable, Mourinho can’t field Ndombele with proper protection. This leads Spurs to play a lot of pretty dreadful stuff, muddying up the game to keep things ticking along. (I’m sure you’re all shocked that Mourinho would do this.) So bringing in a high-quality holding midfielder would improve the defence and the attack, giving the side a more secure base from which Ndombele and others could really do their thing and dominate football matches.

Mourinho has been able to do this without much of a functional midfield. Tensions between the two aside, Tanguy Ndombele has looked an exciting forward passer when on the pitch, and Mourinho has found roles for such players in the past. Of course, this has typically been alongside a robust holding midfielder, such as Matić partnering Cesc Fàbregas. With the current candidates for the number six role consisting of Harry Winks, who offers calm passing and little presence in front of the back four, and Eric Dier, whose physical limitations seem increasingly insurmountable, Mourinho can’t field Ndombele with proper protection. This leads Spurs to play a lot of pretty dreadful stuff, muddying up the game to keep things ticking along. (I’m sure you’re all shocked that Mourinho would do this.) So bringing in a high-quality holding midfielder would improve the defence and the attack, giving the side a more secure base from which Ndombele and others could really do their thing and dominate football matches.

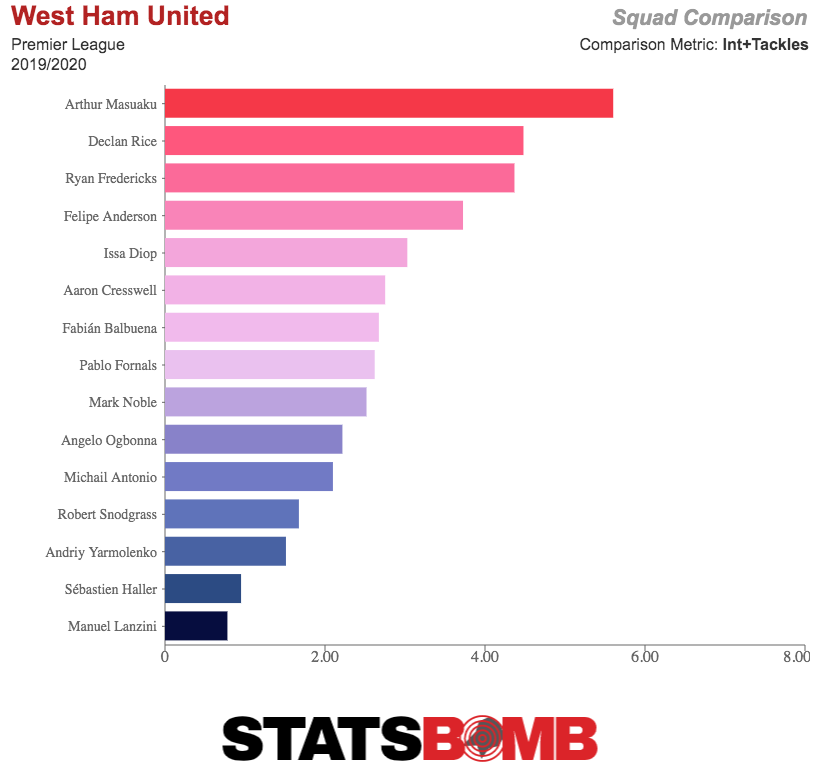

West Ham: a defensive midfielder

Famous team in London, shiny new stadium, no midfield control. There’s no way around the fact that West Ham are a bad football team. They’re not great in attack and terrible in defence, conceding an alarming 1.66 xG per game. David Moyes has obviously been hired to tighten the Hammers up, and he’ll likely take the same tack as fellow traveller José Mourinho and make them unwatchable in the process. He’d be wise to realize the biggest reason why Manuel Pellegrini failed was the lack of midfield control that enabled him to assert his attacking style on teams. If you want your midfield double pivot to win the ball back, Declan Rice and Mark Noble don’t really do that. When looking at West Ham players’ tackles and interceptions per 90, Rice is a reasonable but not exceptional contributor while Noble falls below more attacking players Pablo Fornals and Felipe Anderson. It’s just not enough.  Moyes has failed in previous clubs due to an overreliance on experienced British pros. The same mistake must not be made here with Mark Noble; instead, an adequate replacement should be at the top of his shopping list.

Moyes has failed in previous clubs due to an overreliance on experienced British pros. The same mistake must not be made here with Mark Noble; instead, an adequate replacement should be at the top of his shopping list.

Chelsea: don’t do anything stupid

Frank Lampard made a flying start to life back at Stamford Bridge before enduring a difficult winter. The numbers show Chelsea to be a really good side, third-best in xG difference per game, yet they've suffered a fairly brutal number of goals from the shots they’ve conceded.  Some of this can be blamed on Kepa Arrizabalaga and his long-term below average shot-stopping numbers, but the model estimates he has only conceded 2.26 goals more than expected this season. The rest of his underperformance can be blamed on other factors. Predicting future xG under- and over-performance is always a crapshoot, but the most likely scenario is that it gets at least a bit better. Chelsea are good and should trust in themselves. Which is why it makes it all the stranger that the rumours are of them going big this month. Resigning Nathan Aké would be a reasonable move, with centre-back options often looking thin given Antonio Rüdiger’s frequent injury problems. Emerson Palmieri and Marcos Alonso both look prone to errors at times, so a long-term solution at left-back is entirely justifiable. But making further radical changes to the attack is not. Talk of Zaha and Moussa Dembélé abounds, with both seeming like outright downgrades on what Lampard already while requiring serious cash. Jadon Sancho is certainly a big talent, but the cost of extracting him from Dortmund is gut-clenching when the club already have good young talents in the wide positions in Christian Pulisic and Callum Hudson-Odoi. Chelsea have really promising talents that have shined through the transfer ban. Don’t mess it all up just because you can.

Some of this can be blamed on Kepa Arrizabalaga and his long-term below average shot-stopping numbers, but the model estimates he has only conceded 2.26 goals more than expected this season. The rest of his underperformance can be blamed on other factors. Predicting future xG under- and over-performance is always a crapshoot, but the most likely scenario is that it gets at least a bit better. Chelsea are good and should trust in themselves. Which is why it makes it all the stranger that the rumours are of them going big this month. Resigning Nathan Aké would be a reasonable move, with centre-back options often looking thin given Antonio Rüdiger’s frequent injury problems. Emerson Palmieri and Marcos Alonso both look prone to errors at times, so a long-term solution at left-back is entirely justifiable. But making further radical changes to the attack is not. Talk of Zaha and Moussa Dembélé abounds, with both seeming like outright downgrades on what Lampard already while requiring serious cash. Jadon Sancho is certainly a big talent, but the cost of extracting him from Dortmund is gut-clenching when the club already have good young talents in the wide positions in Christian Pulisic and Callum Hudson-Odoi. Chelsea have really promising talents that have shined through the transfer ban. Don’t mess it all up just because you can.

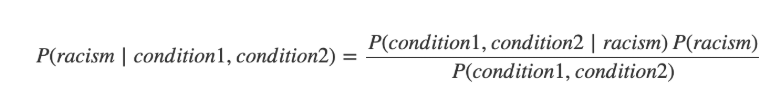

UEFA avoiding racism at the 2020 Euros? Bayes-ically impossible

If we were to draw a Venn diagram of everything that statistics can provide a useful framework to examine (along with narrative, context, and case studies, of course, because we’re not heathens here), everything that is political, and sports, we’d have one very large circle. And what better way to ring in the new decade than taking a moment to come full circle on that circle and use statistics to examine politics in sports? Late last year, UEFA issued an incredibly bold statement about the upcoming Euros: Despite us encountering at least one incident of racism in Europe every week for as long as we can remember, the powers-that-be seem confident that the power of football at the continental scale will overcome any bigotry that national associations have failed to stamp out. "In our experience, the Euro has always been a very festive event, at least within the stadiums," UEFA Vice President, Giorgio Marchetti, said in a press conference. "We are confident that this particular atmosphere will take priority over stupid and sometimes criminal things that unfortunately from time to time happen in football, and we never want to see in our sport." These “stupid and sometimes criminal things” Marchetti dares not speak the name of are prevalent in every single league and in every single fanbase. National and international media and the leaders of several UEFA countries definitely aren’t helping the matter. But still, perhaps Marchetti and UEFA are right. To know for certain, let’s use statistics to infer whether or not racist incidents are likely to occur during the 2020 Euros. Because we’re working with a smaller dataset, because I have a lot of questions about UEFA’s priors, and because there’s never a bad time to use the method, we’ll be taking a Bayesian approach to this problem (my sincerest apologies to Thomas). Specifically, we’ll rely on prior information about racist incidents in European football to guide our inferences about whether UEFA’s claim will hold true. Let’s start with the hypothesis put forward by UEFA and Marchetti: The festive atmosphere of the Euros (condition 1) combined with fans only resorting to bigotry when they have nothing better to do (condition 2) will help ensure that racism doesn’t mar the tournament. To test this hypothesis, we implement the following Bayesian formula:  Or to put it another way, the probability of racism occurring during the Euros (the “posterior”, if you want the Bayesian term for it) is equal to the probability of our “priors” (the conditions laid out by Marchetti), multiplied by the “evidence” (the probability of racism occurring at a sporting event)), divided by the probability of the Euros having a festive atmosphere and fans that have better things to do than be racist. To properly solve this formula, we’d need to pick a prior distribution, talk about posterior distributions, and dig deeper into likelihood functions. This author would have to spend days of their life collecting data on every racist event at a football game in the last decade or so, which sounds like the worst possible way to ring in the new year. Instead, let’s focus on the highlights that provide our considerable prior knowledge:

Or to put it another way, the probability of racism occurring during the Euros (the “posterior”, if you want the Bayesian term for it) is equal to the probability of our “priors” (the conditions laid out by Marchetti), multiplied by the “evidence” (the probability of racism occurring at a sporting event)), divided by the probability of the Euros having a festive atmosphere and fans that have better things to do than be racist. To properly solve this formula, we’d need to pick a prior distribution, talk about posterior distributions, and dig deeper into likelihood functions. This author would have to spend days of their life collecting data on every racist event at a football game in the last decade or so, which sounds like the worst possible way to ring in the new year. Instead, let’s focus on the highlights that provide our considerable prior knowledge:

Condition 1

From what we know about Euros in the past, UEFA is definitely on to something when they assume there’ll be a festive atmosphere surrounding the competition. In general, major tournaments tend to see far more festivity than regular games. Will the festive atmosphere be diluted by the competition being spread out over 12 different countries? Perhaps! But we have no data to adjust our Festivity Quotient here, so we’ll assume it has no effect.

Condition 2

This is where UEFA loses us. It’s very rare to hear an argument that putting something mildly entertaining in front of people will mitigate their desire to dehumanise people who don’t look like them. It also goes without saying that if people could be distracted from acts of racism (and other forms of bigotry) by festive events, marginalised people wouldn’t ever stop throwing parties. Nor does UEFA seem to believe that the magical restorative powers of international soccer atmosphere apply to other forms of social discord. They have, for example, taken steps to prevent certain nations involved in political or military disputes from facing each other in a tournament setting, rather than relying on the festive atmosphere to do its thing.

Condition 1 and Condition 2

Of course, Marchetti believes it’s a combination of conditions 1 and 2 that will mitigate any racism during the Euros. Which is especially perplexing as pretty much every racist incident inside a football stadium seems to occur while football is actively being played. To take this point to its logical conclusion, UEFA is claiming that the festive atmosphere (condition 1) is somehow both separate from, and more entertaining than, the actual sport all these fans are paying to watch. And that somehow, the combination of these two variables is all that’s necessary to combat racism. Thinking about this for more than a second gave this author a headache, but that doesn’t necessarily mean UEFA haven’t thought their conditions through. Basic common sense and overwhelming evidence that distracting festivity doesn’t mitigate racism, however, does support that idea that UEFA may be wrong here.

Evidence

The lack of data collection involved in this entire exercise means our evidence is purely anecdotal. However, we can definitely conclude that racist incidents are occurring with depressing regularity in leagues across Europe. We could also probably make a conjecture that fans involved in these incidents are emboldened by the political atmosphere in many European countries at this point. In Bayesian statistics, there’s absolutely no issue with choosing uninformative priors: a prior that acknowledges that we do not have a lot of data or experience with a particular problem. What Marchetti and UEFA have here, however, is more of a wilfully uninformed prior, having made several incredibly bold claims with absolutely no regard for the data around them. And they’re using these priors to make a prediction that absolves them from any kind of planning or pre-tournament work that might protect players and fans of colour from any potential racist abuse during the Euros. Given that the political atmosphere in Europe is clearly seeping into most stadiums, UEFA might want to consider re-examining their priors here so they can arrive at a more realistic prediction of whether or not it’s likely that we’ll see racist events and behaviour during the 2020 Euros. Of course, if we look at our priors on how well they’ve dealt with racist behaviour in the past, the likelihood of that happening seems pretty low. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

Is Moussa Dembélé worth a potential mega transfer fee?

“Boy, the food at this place is really terrible,” a woman tells her friend in a Borscht Belt joke reproduced by Woody Allen (ugh, sorry) in Annie Hall. “Yeah, I know,” her interlocutor replies, “and such small portions.” Replace food with shots and you have Moussa Dembélé, reportedly a transfer target for Manchester United and Chelsea. The 23-year-old Lyon striker is having a bad year. In better times, way back in 2018–19, he took — and converted – plenty of good shots in the box. He didn’t do much else, but that was his job. He was good at it. This season, he’s doubled down on being a target man. He’s winning the ball in the air more and dribbling less. He’s still not doing much in the non-shooting department . . . but now he’s also not doing much in the shooting department. Dembélé is getting fewer shots than the average Ligue 1 striker and the quality of his chances has markedly decreased, all of which adds up to a player who contributes very little.  At the same time, Dembélé is having a hot finishing season. Going into Ligue 1’s winter break, he’s turned chances worth 4.3 expected goals into 8 non-penalty goals. Add in his scoring two of three penalties and you have a player who is tied for third in the Ligue 1 scoring table — just one goal behind Kylian Mbappé (who has played far fewer minutes). If that’s the only figure examined, Dembélé looks like a player on the rise.

At the same time, Dembélé is having a hot finishing season. Going into Ligue 1’s winter break, he’s turned chances worth 4.3 expected goals into 8 non-penalty goals. Add in his scoring two of three penalties and you have a player who is tied for third in the Ligue 1 scoring table — just one goal behind Kylian Mbappé (who has played far fewer minutes). If that’s the only figure examined, Dembélé looks like a player on the rise.  Dembélé is hardly the first player to paper over a bad season with some hot finishing. This dynamic, however, makes the transfer interest somewhat mystifying. Player transfers are wont to reflect goal totals. (See: Pépé, Nicolas.) A club that buys Dembélé will therefore be paying for one of France’s top strikers. If his production falls in line with this season’s underlying numbers, that’s a bad deal. If a club believes Dembélé will return to his 2018–19 form, they won’t be able to buy low because his current season is superficially successful. Neither of those are tremendously appealing propositions. If this season proves to be a blip, those considerations will cease to matter. Members of the public needn’t care whether a billionaire saves some money or pays the full price when buying a good player. But is it just a blip? Lyon are taking five fewer shots per 90 minutes this year than the side that led Ligue 1 by a large margin in 2018–19. While that number suggests team-wide issues, Dembélé is the only player whose shot volume has fallen off a cliff (The drop-off largely reflects Nabil Fekir, a prolific shooter, leaving the club, and Memphis Depay, who had been taking his usual bevvy of shots, being injured). Manager Rudi Garcia’s arrival as the mid-season replacement for Sylvinho hasn’t had any effect on Dembélé’s shooting. It’s not immediately clear why only Dembélé’s shots, and not those of other attackers like Maxwel Cornet or Bertrand Traore, have gone missing. The diminished quality of Dembélé’s shots, on the other hand, is consistent with the team’s other attackers. They may all be feeling the effects of crucial injuries and Fekir and Tanguy Ndombele leaving the club. One glaring example: Dembélé took 19 shots from through-balls in just under 2,200 league minutes in 2018–19; he’s already played more than 1,500 minutes this season and taken one such shot. Worsening service can’t explain away all his issues, but it helps show how his shots have become so much worse while still coming from similarly close and central locations. Bad years happen. Moussa Dembélé is young and may rebound. Insofar as his only value comes from shooting in the box, though, clubs would do well to wait and see if he’s still good at that.

Dembélé is hardly the first player to paper over a bad season with some hot finishing. This dynamic, however, makes the transfer interest somewhat mystifying. Player transfers are wont to reflect goal totals. (See: Pépé, Nicolas.) A club that buys Dembélé will therefore be paying for one of France’s top strikers. If his production falls in line with this season’s underlying numbers, that’s a bad deal. If a club believes Dembélé will return to his 2018–19 form, they won’t be able to buy low because his current season is superficially successful. Neither of those are tremendously appealing propositions. If this season proves to be a blip, those considerations will cease to matter. Members of the public needn’t care whether a billionaire saves some money or pays the full price when buying a good player. But is it just a blip? Lyon are taking five fewer shots per 90 minutes this year than the side that led Ligue 1 by a large margin in 2018–19. While that number suggests team-wide issues, Dembélé is the only player whose shot volume has fallen off a cliff (The drop-off largely reflects Nabil Fekir, a prolific shooter, leaving the club, and Memphis Depay, who had been taking his usual bevvy of shots, being injured). Manager Rudi Garcia’s arrival as the mid-season replacement for Sylvinho hasn’t had any effect on Dembélé’s shooting. It’s not immediately clear why only Dembélé’s shots, and not those of other attackers like Maxwel Cornet or Bertrand Traore, have gone missing. The diminished quality of Dembélé’s shots, on the other hand, is consistent with the team’s other attackers. They may all be feeling the effects of crucial injuries and Fekir and Tanguy Ndombele leaving the club. One glaring example: Dembélé took 19 shots from through-balls in just under 2,200 league minutes in 2018–19; he’s already played more than 1,500 minutes this season and taken one such shot. Worsening service can’t explain away all his issues, but it helps show how his shots have become so much worse while still coming from similarly close and central locations. Bad years happen. Moussa Dembélé is young and may rebound. Insofar as his only value comes from shooting in the box, though, clubs would do well to wait and see if he’s still good at that.

Olmo and Stevanović and Chalov oh my: Transfer targets you should know from Eastern Europe

Transfer season is here. While many of the headlines will focus on big rumors about big players in big leagues, there's a whole lot more soccer out there. So, here are four players from across eastern Europe who might catch a smart team's eye.

Dani Olmo, Dinamo Zagreb

What’s surprising is that Dani Olmo is on this list—although perhaps by the time you’re reading this, he’ll have signed with one of the major Spanish clubs (for example, it’s rumored that Barcelona, the team of his youth, have made a formal offer) or for Chelsea (who appear to be chasing every sweet young thing in eastern Europe).Some of us have a type, and for me, that type is an attacking midfielder who usually plays on the wing (and truth be told I prefer a left-winger, naturally). I fall more deeply in love if that winger is good with the ball at his feet

The surprise about Olmo isn’t that some would argue that Croatia is not part of “eastern” Europe, it’s that the Barça youth product hasn’t left Dinamo Zagreb already. He signed for Croatia’s most successful team when he was just 16, part of the deal that sent Alen Halilović to Barcelona, and it’s fairly obvious that it’s Dinamo that got the upper hand in that exchange. His four years in Croatia have shaped him into the best player in the domestic league by far, and he showed his skills to a wider audience in this year’s Champions League, first scoring against Shakhtar Donetsk, then recording the opening goal in the eventual 1–4 defeat to Manchester City.

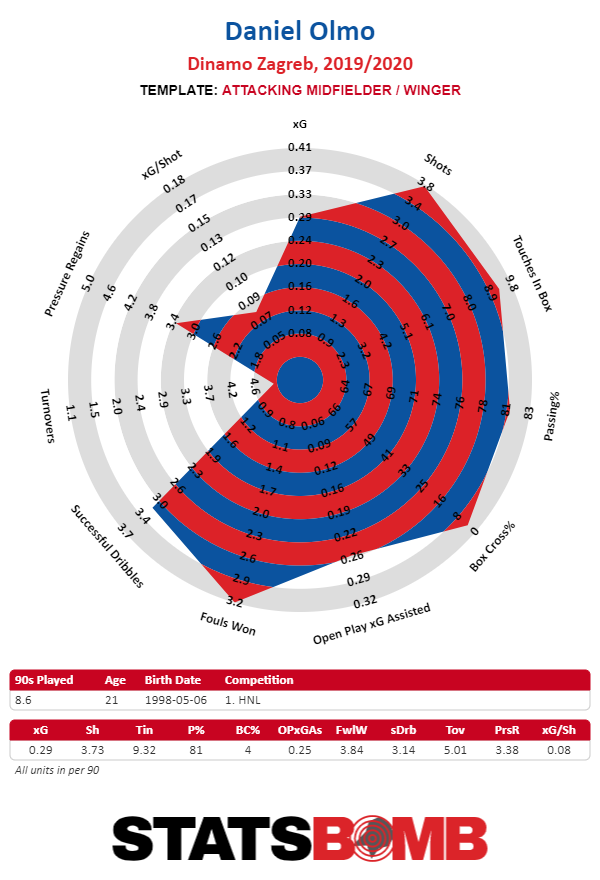

Sure, two European goals does not maketh the man, but a lot more production at home in his domestic league sure does maketh the radar.

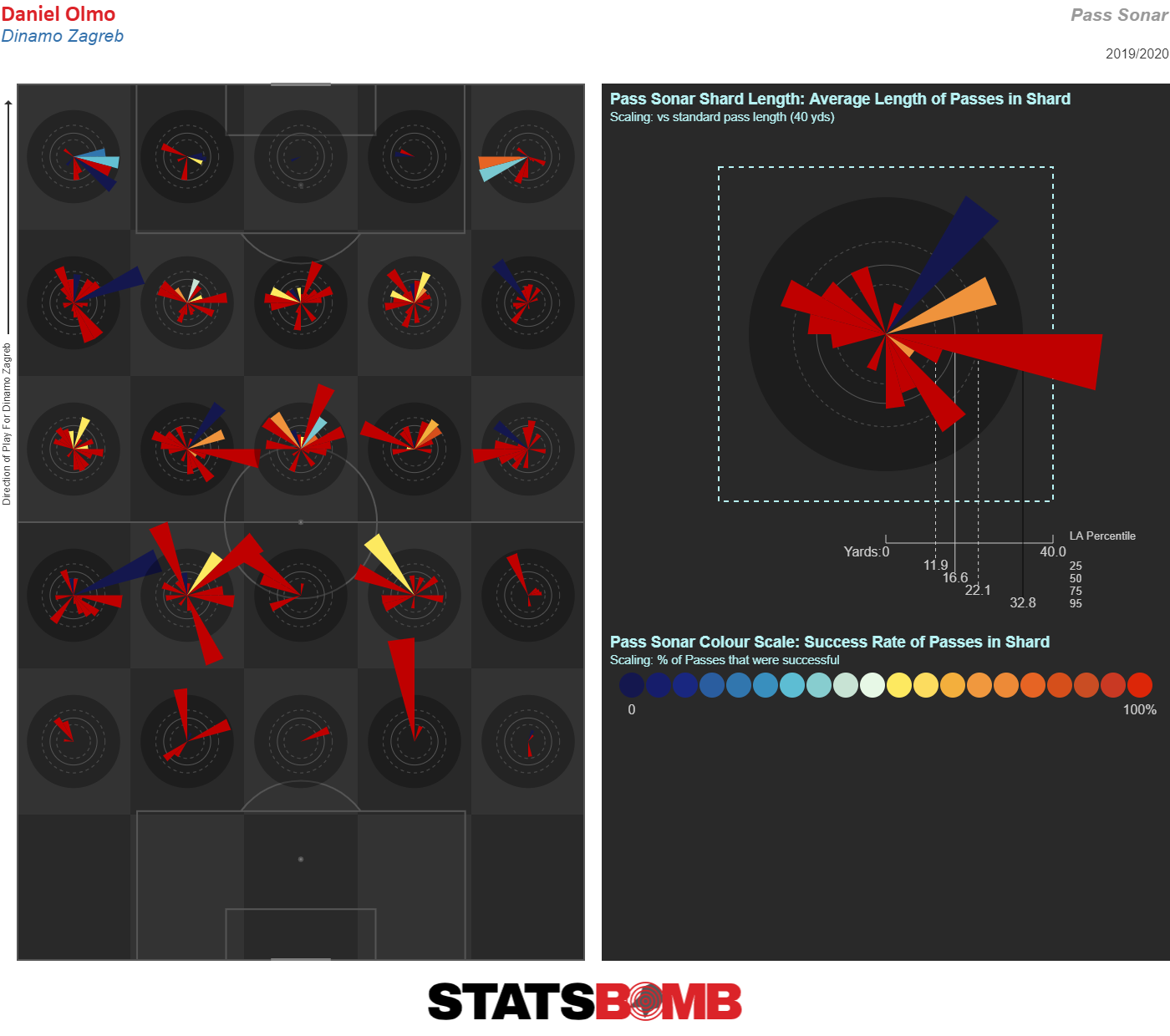

Those who paid attention to Dinamo, particularly those of us who also happen to be lovers of Atalanta who were shocked to see them knocked down 4–0 in Zagreb, will have noticed Olmo is the one who directs his side’s play. He’s an attacking midfielder/winger with an excellent dribbling technique (especially noticeable during those Champions League matches) with the ability to change his pace quickly, making it easy for him to lose his marker. This allows Olmo to boss the game all over the field; as his passing sonar shows, he’s capable of picking the ball up all over the place and progressing Dinamo up the field.

This strategy allows him to create opportunities in which Dinamo are two against one in the attacking zone. Plus, he’s on the short side—what more can one ask for in an attacker? Olmo has clearly outgrown the Croatian league, and his talents make it almost certain he’ll be snapped up in January.

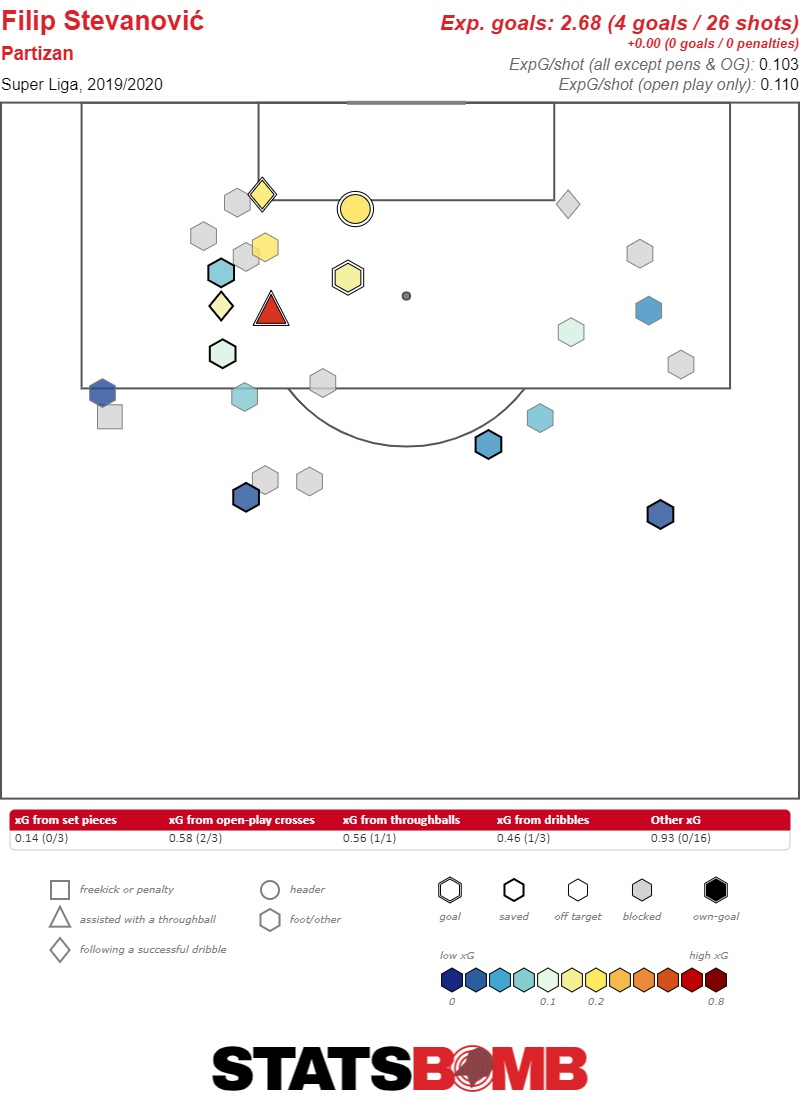

Filip Stevanović, Partizan Belgrade

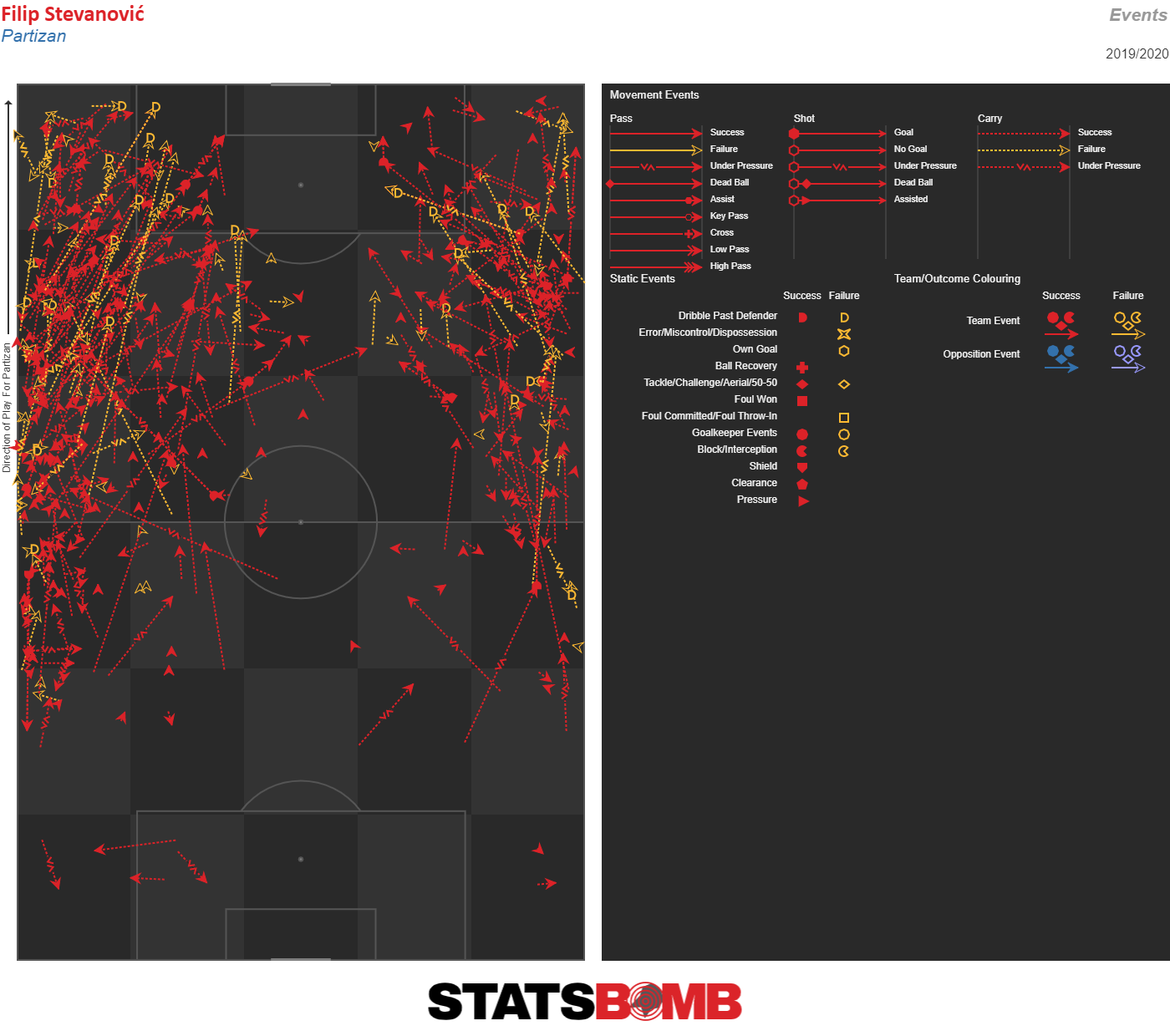

The latest product of Partizan’s famous youth academy made his senior debut last season, when he was just 16—just like Luka Jović did for crosstown rivals Red Star six years ago. And while Stevanović is no imposing central forward (he is, surprisingly, another small attacking winger), it’s not hard to imagine he’ll end up at a club like Real Madrid someday. But, like his fellow Serbian U-21 player, it’s likely he’ll need to jump through a few hoops to get there, given that he’s barely 17, and still isn’t starting in every Partizan match. Then again, the Grobari employed a bit of a rotation system at the beginning of the season, attempting to battle it out for a spot in the next round of the Europa League while closing the 11-point gap between themselves and Red Star at the top of the table. They’ve not succeeded, but it’s not for any lack of talent on Stevanović’s part. The left winger has scored 4 in 14 this season, and tacked on his first European goal against Wales’ Connah's Quay Nomads, way back in the second round of Europa League qualification. There might be a little bit of good fortune in those shooting numbers, but given his age even the 2.68 expected goals he’s totaled is darn impressive. Clearly, Stevanović is never one to shy away from taking a shot from distance and while that might be something that eventually needs to get drilled out of him, he is, again, only 17 years old.

Truly, though, what’s attractive about the youngster is that he’s simply fun to watch. In addition to his fine technique, he possesses fantastic speed. His quickness makes it almost impossible for defenders to track him, plus he loves implementing a good trick to get past an opponent. Sometimes he goes for the more attractive move, rather than the pragmatic one, but that’s likely to improve as his youthful arrogance decreases (and he is faced with more challenging opposition). Good thing, too, because his love for having the ball at his feet often places him further away from the opponent’s goal than he should be—but all those flicks, tricks, and skills means he’s relentlessly attacking the edges of the penalty area.

Given his bursts of speed and developing skill with the ball at his feet, a mid-sized club from one of the top leagues should seriously consider stepping in and snatching him up for a low price, then molding him into the player his talent suggests he could be.

Fyodor Chalov (Fedor), CSKA Moscow

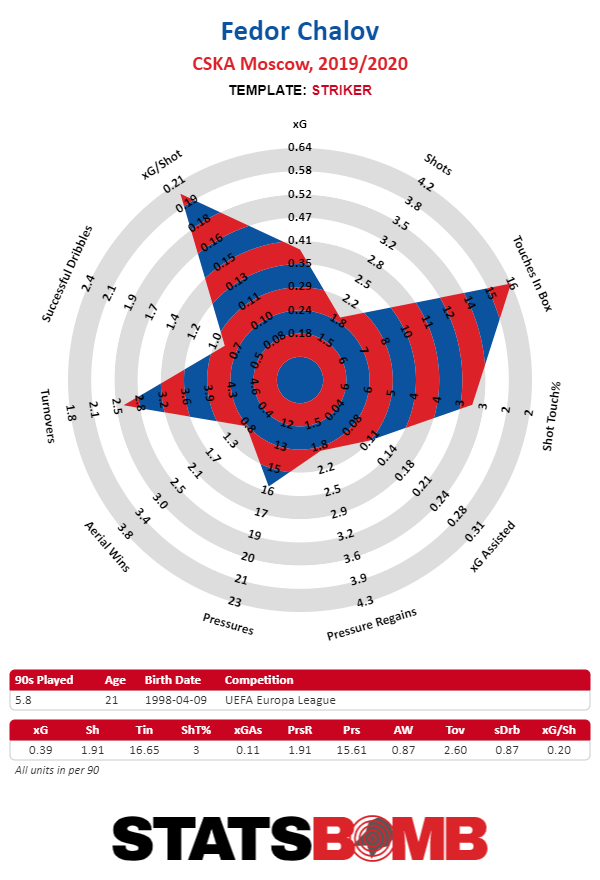

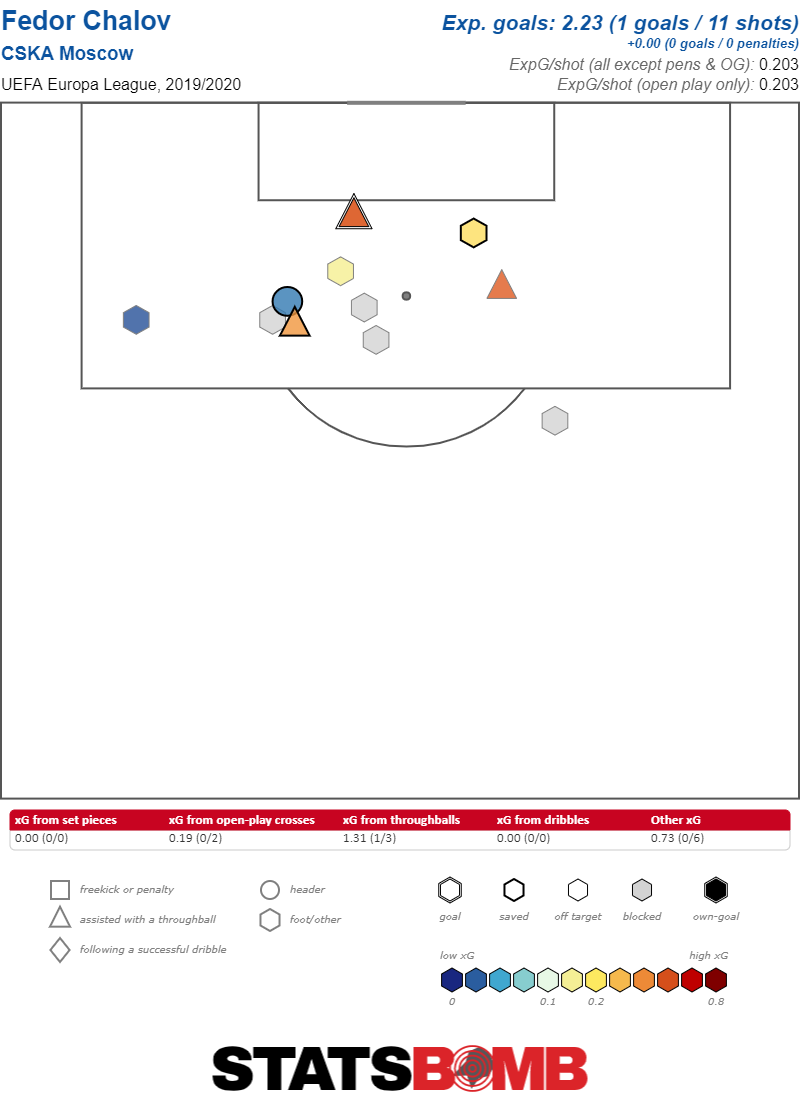

Fyodor Chalov is perhaps one of the most interesting players to come out of Russia since . . . Andrei Arshavin? We can only hope that if he gets snatched up by the likes of West Ham or Chelsea, he’ll give the same sort of bonkers responses that Arshavin used to come out with. But this is an article on football prowess, not my obsession with Andrei, so back to Chalov. Alas, the 21-year-old is not having the best of seasons, having scored only 5 goals in 19 games thus far. Yet if August is silly season, January is absurdity season, and clubs needing a forward may come forth with large wads of cash for a man who scored 15 goals and provided 7 assists last season. And, while the sample size might be small, it’s hard to argue with these Europa League numbers.

It helps that Chalov is a modern forward, one with a nose for goal yet willing to participate in the buildup. He’ll make his own chances happen, and if left any space in any part of the penalty area, he’ll take a shot, being equally adept with both feet. His profile in Europe is one of a player who doesn’t shoot often, but is careful to pounce on the best goalscoring opportunities.

The lack of shot volume might be a concern if he wasn't capable of creating chances for his teammates through his credible passing play. Perhaps his biggest downside is his physique; he is by no means weak, but ball protection and aerial duels can sometimes be a problem. He operates better when he has space to outrun his opponents, and even more so when he has teammates who are also able to threaten the defense, which may be why he’s faltering now—his only real help is coming from midfielder Nikola Vlašić, who’s scoring his own goals. It may be he needs to part of a squad that provides a larger number of credible threats, drawing defenders away from Chalov. Personally, this Aston Villa fan would be fine with him stepping in to compensate for Wesley, who’ll be out for the rest of the season.

Dennis Man, Fotbal Club FCSB [Steaua]

Dennis Man, a 21-year-old attacker described as “one to watch,” may already be on your radar screen if you watch a lot of Romanian football, paid close attention during the 2019 U21 Euros, or enjoy watching Malta get beaten in their attempts to qualify for world competition (having earned his first senior cap in 2018, he first scored for the Romanian national team in their 4–0 victory last June). Man, currently playing for the club once known as Steaua Bucharest and now referred to as FCSB, is expected to leave Romania this summer at the latest, but he could be snatched up by a club eager to turn their fortunes around midseason. In fact, Steaua reportedly rejected a €15m bid from Manchester United in 2018, saying the price was too low. Given his buyout clause is €100 million, that’s not terribly surprising. It’s hard to say whether Man is worth that much, but we’ve seen desperate clubs pay ridiculous prices for far less before.

Man has a tendency to dribble past anyone who gets in his way. Usually I prefer my favs to be a bit on the short side, but even at 6’0”, he isn’t physically imposing. Instead, his strength lies in his fantastic technique and his orchestration of play. He tends to cut in from the right, getting into promising positions that help create goals for Steaua—or the opportunity to net one himself. His numbers are about what you’d expect from an attacking midfielder, with 10 scored last season, and 4 after 15 league games. But the thing is, he doesn’t take too many shots, so when he does fire one off, it’s likely to go in. It’s little wonder, then, that Sevilla are rumored to be after him, particularly as his technical qualities seem particularly suited to La Liga.

Harry Kane and the death of a shot monster

"Harry Kane is Broken" fever is sweeping the soccer Twitter world. And that was before Harry Kane actually limped off the pitch against Southampton on Wednesday with an apparent hamstring injury. Nearly a year ago, Ted Knutson first mentioned on the StatsBomb podcast that Kane might be Fernando Torres-ing. I was resistant. I thought some time off this summer, time he did not have in 2018, would finally give him some rest and let his ankles heal, helping him to regain the proprioception that allowed him to Moneyball his way to becoming a shot monster despite his relatively limited athleticism.

That's certainly not happened. He’s declined markedly in terms of shot generation and has not made up for it by improving elsewhere. However, Kane has managed to maintain his elite finishing ability. Over his career, he has outperformed his non-penalty expected goals by around 20%. When he kicks the ball, he still hits it hard and to the right places.

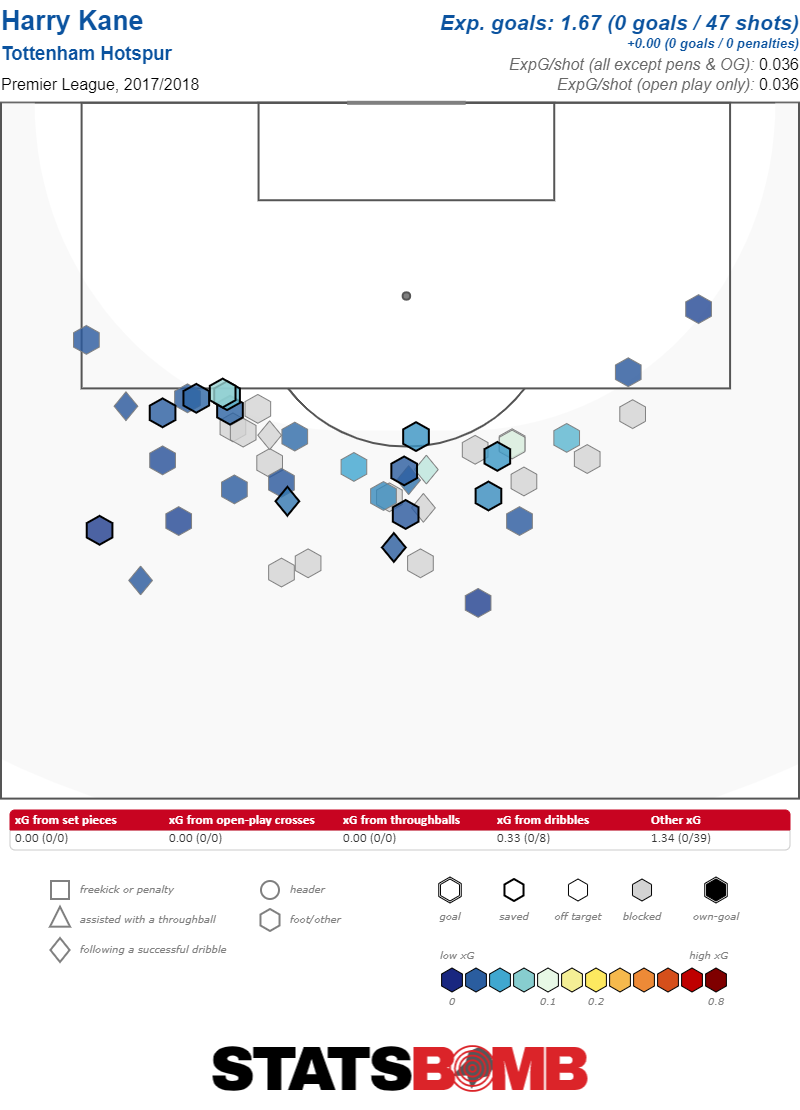

The problem is that he does not shoot anymore. When Nabil Bentaleb and Ryan Mason were Spurs’ midfield in 2014–15, Harry Kane took 4 shots per match. At his best, in 2017–18 (before the ankle injury that truly derailed his career), he took nearly 6 shots per 90 minutes. Now, Harry Kane attempts under three shots per 90, and his xG per shot has decreased. His non-penalty xG per 90 is a paltry 0.3. Relatedly, in 2017–18 Tottenham had 1.8 xG per match but have dipped to 1.3 xG per match, even as Son Heung-Min remains excellent. It’s bad, folks.

Throughout the Tottenham fan sphere, debates rage over whether Kane himself is just bad, or the team is bad and so he's not getting service. It seems mostly the former, but if Kane can learn to age more gracefully, the team's other weaknesses will be more evident. To recover some of his greatness, Kane really needs to stop trying so hard to make things happen.

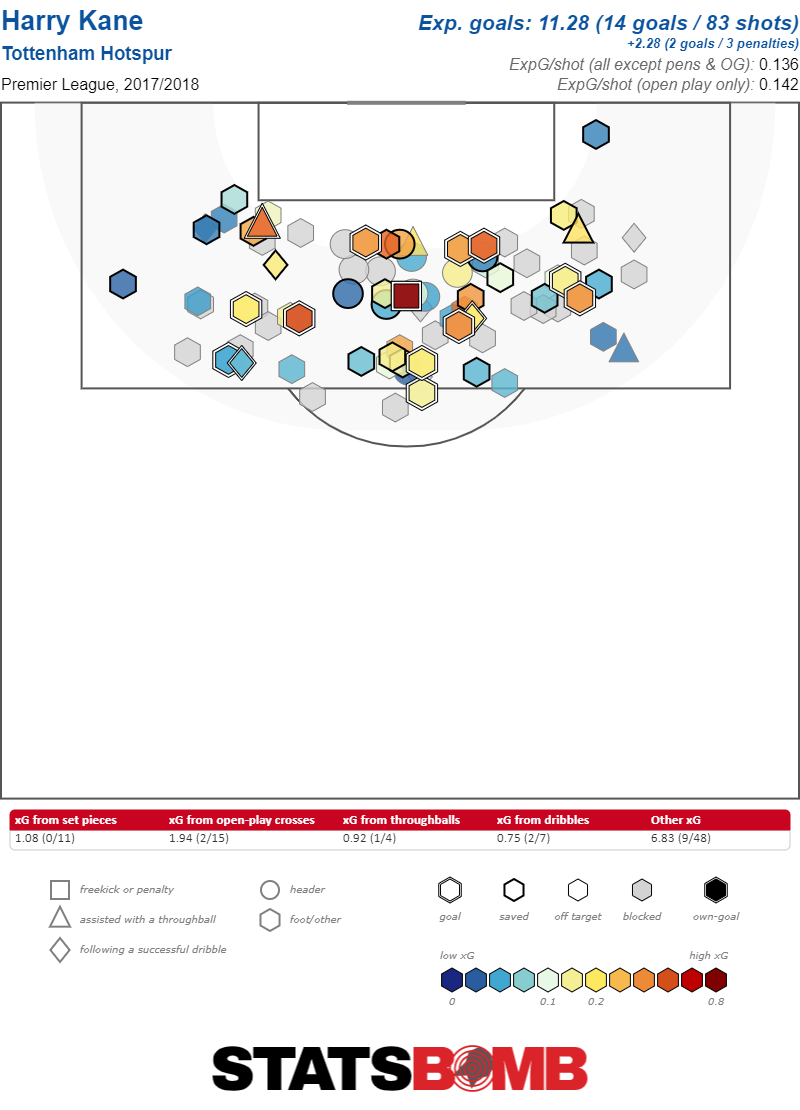

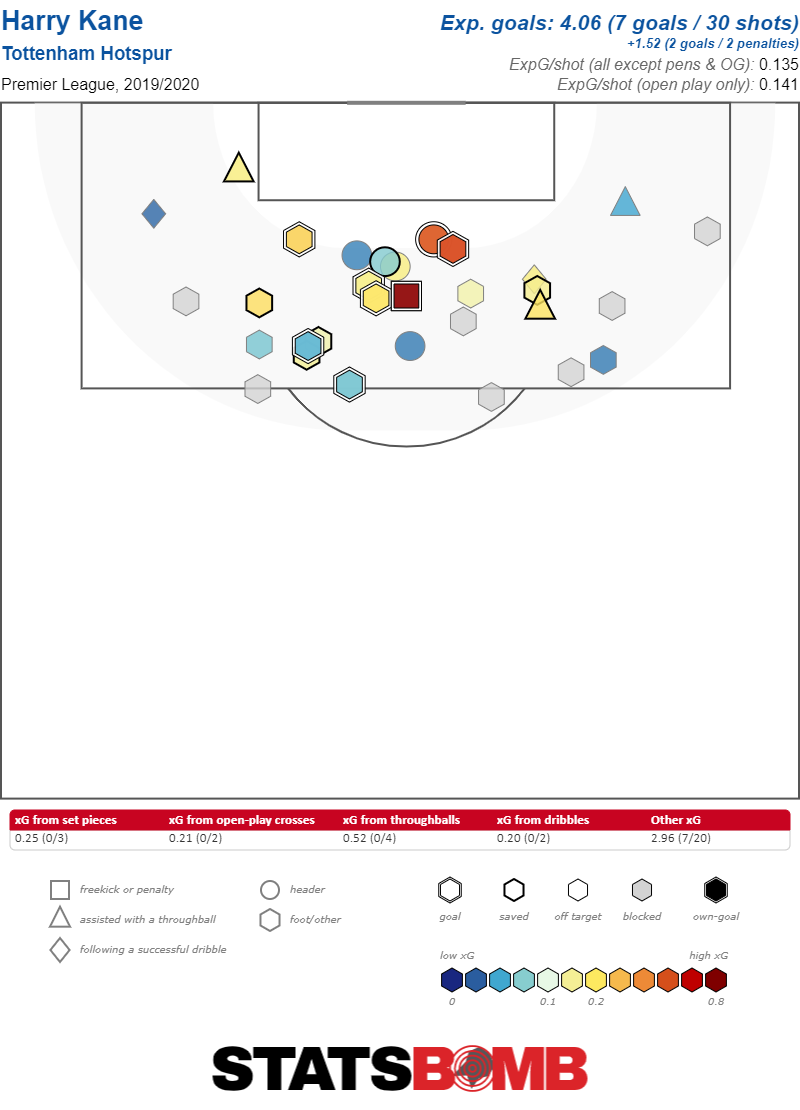

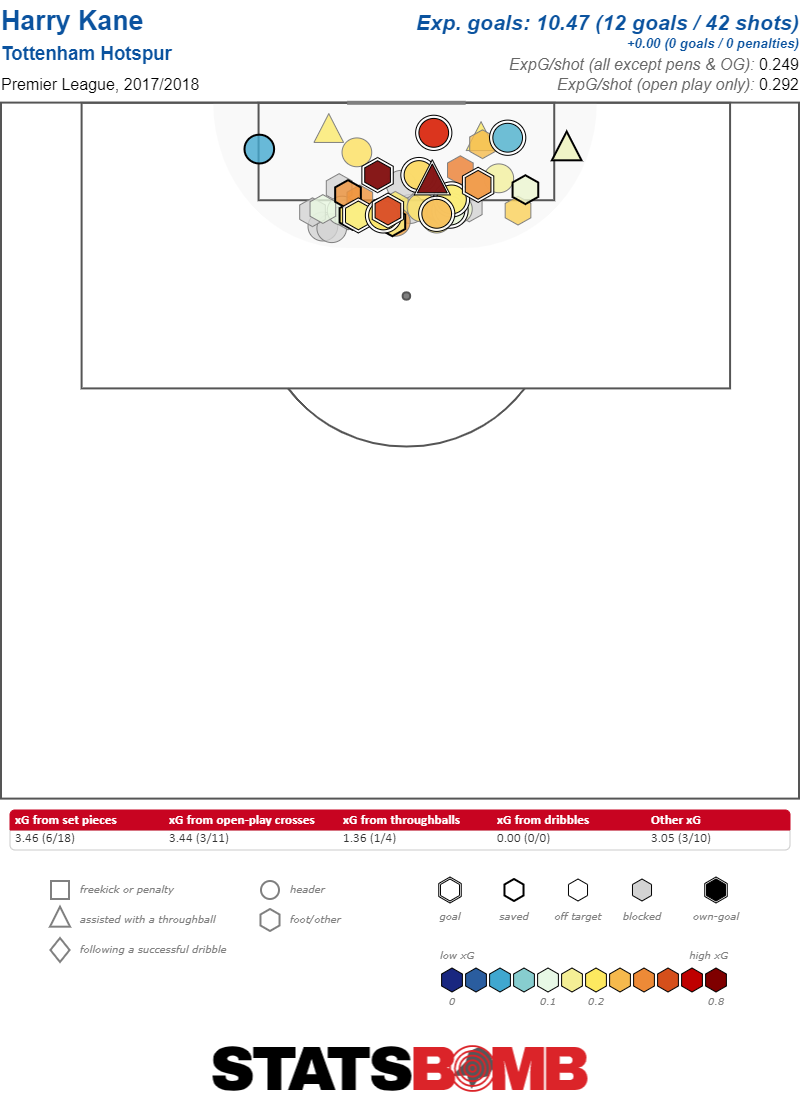

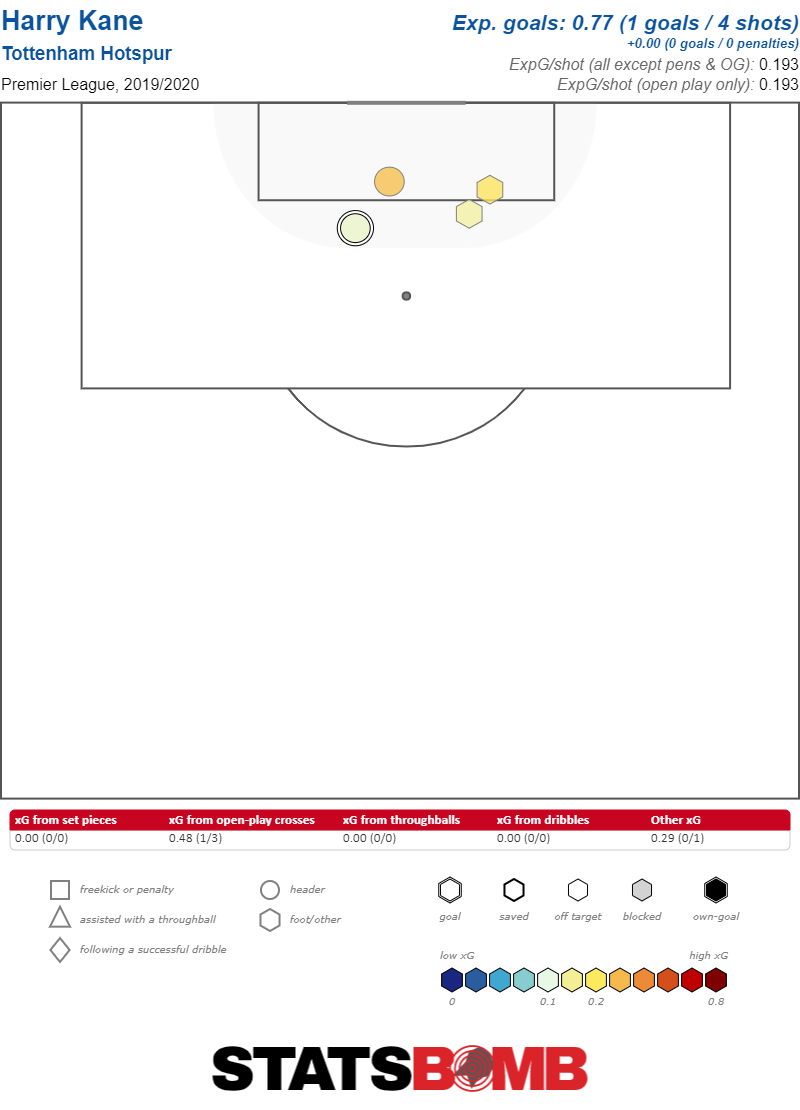

Kane used to be exceptional at letting off shots close to the goal. Using StatsBomb’s shooting charts, I divided Kane’s 2017–18 and 2019–20 shot maps into three areas: within 9 yards of the center of the goal, between 9 and 21 yards of the center of the goal, and 21 yards or more from the center of the goal.

Outside of 21 yards, Kane had 49 shots (not including free kicks) and 1.8 xG in 3000 minutes in 2017–18.

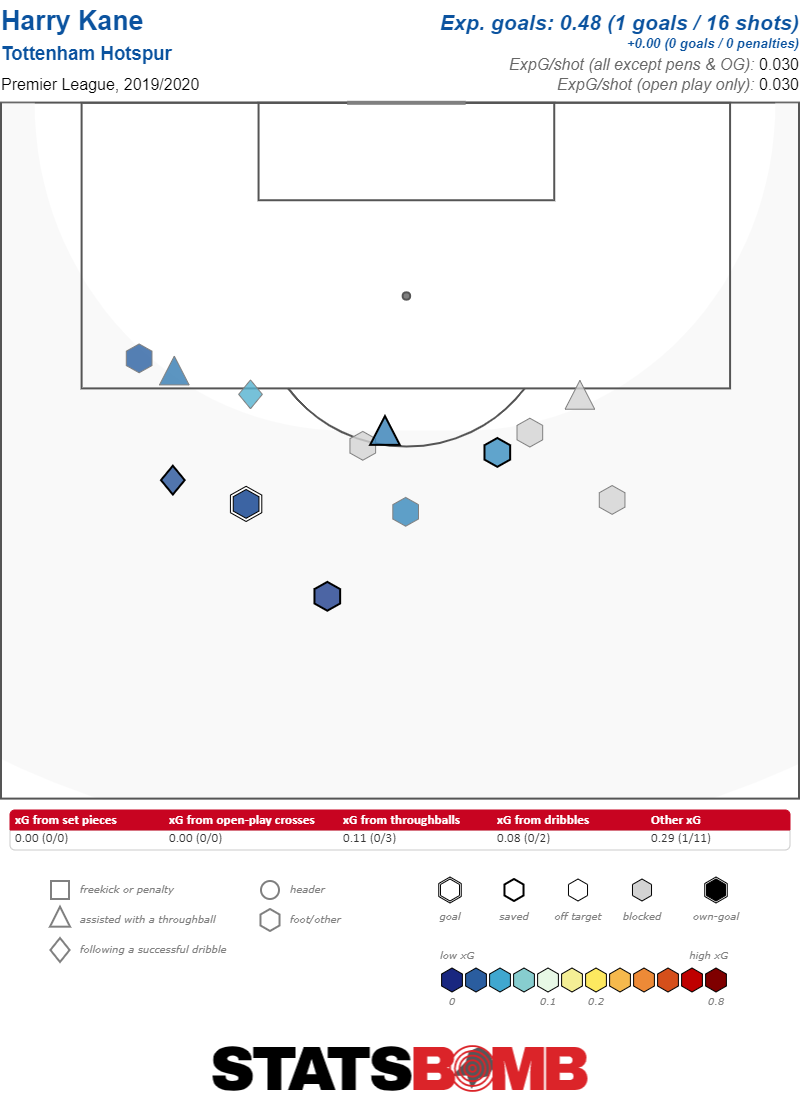

This season it’s 16 shots and 0.48 xG in 1800 minutes. Frankly, it was wasteful to have so many shots from outside the box, so reducing that volume from 1.5 per game to 0.8 per game is actually good.

Since 2017–18, Kane's production from 9 yards to 21 yards from the center of the goal has decreased. This is the area where Kane would create shots inside small amounts of space and let them rip. In 2017–18 he had 83 shots and 11.3 xG in that zone.

This year, 30 shots and 4.06 xG. He's lost another 0.75 shots per match and a tenth of an expected goal per match. That might seem almost insignificant, but over the course of a season it adds up to almost four goals, a large difference in any strikers' total. Little differences add up.

And then it gets worse. Within 9 yards of goal? Utter collapse. In 2017–18, Kane took 42 shots from within 9 yards of goal and had 10.5 xG.

This season, he's at 4 shots and 0.77 xG. In 2017–18 he managed nearly 0.33 xG per 90 in the area around the goal. His numbers have dropped dramatically to 0.05 per 90. If a tenth of an expected goal per match adds up to real differences, a quarter of an expected goal per match lost is enough to cause a career to implode.

Harry Kane was never just a tap-in merchant, but he was great at it, and considering it requires a ton of skill, this made him extremely valuable. He could get into great positions and fire off a shot, or stick a leg out. He was just there, ready to shoot.

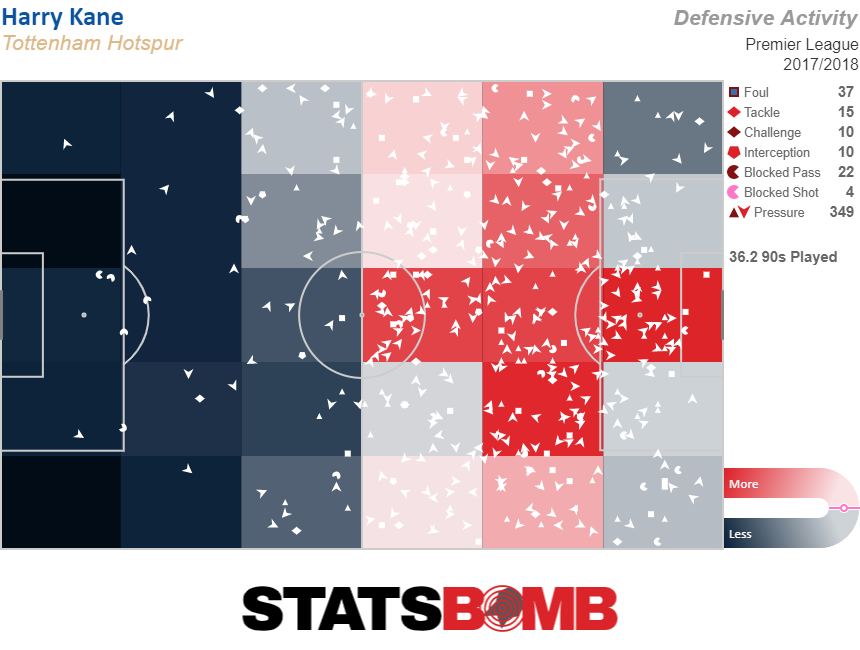

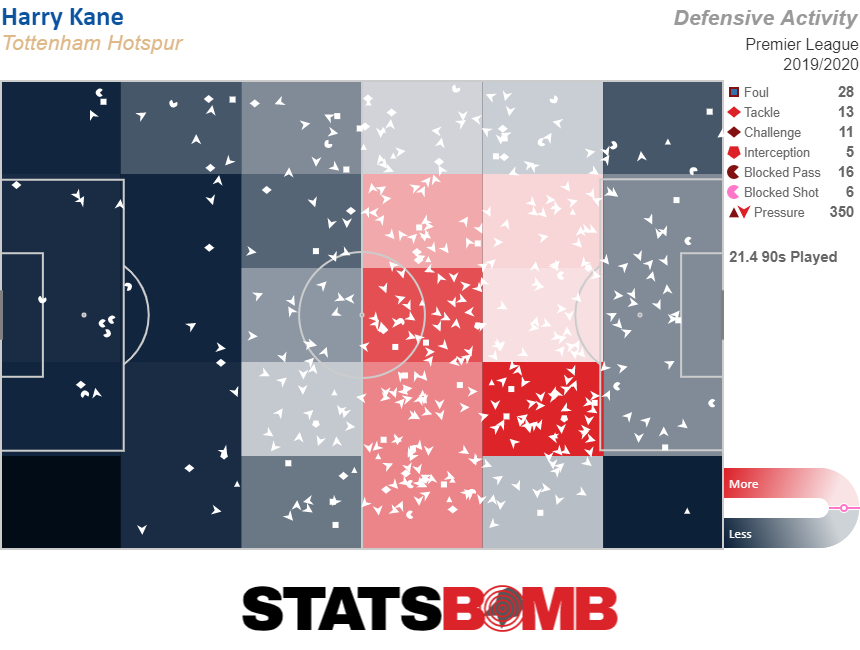

Now? Now he’s everywhere else, and it’s bad. Harry Kane’s defensive activity map from that 2017–18 season reveals a literal red cross in the center of the attacking area. He had 9.63 pressures per 90 that season.

And then there's Harry Kane’s defensive activity map for this season. He has 16.32 pressures per 90 this season, yet the penalty box is gray. His activity is deeper and more dispersed across the pitch. His athleticism has decreased, but he's also running more—and everywhere—this year. These stats totally confounded me, as my impression watching Spurs was that he wasn’t making runs, but now I think he is, just during the wrong stage of play.

He is, verifiably, one of the greater kickers of a soccer ball in the world. He should kick more, and run less, when Spurs are out of possession, saving his energy for bursts in the box. When José Mourinho came to Spurs there was hope Kane would be told to sit in the box and wait for the ball, then kick the ball or head the ball. He has not. Kane is constantly receiving passes in the channels and trying to cut inside, something he should do far less. It’s not just a numbers thing. Every match makes it evident Kane out of position to do the thing he was put on this Earth to do, kick the ball hard at the corner of a football goal. He isn’t lurking off a defender's back shoulder and making runs to a post, leading to a shockingly small number of shots in the six-yard box. Instead, he’s lingering at the edges of the box, trying link up play and DO STUFF.

It almost seems like a bad habit, picked up from too many matches in which Moussa Sissoko and Harry Winks were unable to control possession in midfield. That midfield has been a mess for nearly two seasons now. Kane seems to feel some responsibility to help out, to chase the ball and to defend. In fact, he appears desperate to do so, perhaps thinking that if Spurs don’t have the ball, then he can’t get it and score. And in a sense he's right. But this is why Spurs’ inability to control the midfield has exacerbated Kane's health issues. Yet it’s not what he’s put on a soccer field to do. He was always solid at leading a press on the tip of the spear, arcing his runs in pressure, triggering Mauricio Pochettino’s press. But he has never been fast, nor has he been a great defensive forward.

When Kane was younger and healthier, he could do it all: run hard, get into channels, and still have the energy to make constant runs to the posts. He doesn’t have that anymore. He needs to accept it. When he returns from his latest injury, Tottenham need to create a system in which they win the ball back better without his help, and then maybe he can get back to doing what he does best: get ball, find space, kick ball hard.

Header image courtesy of the Press Association