This May will mark seven years since Manchester United last won the Premier League title. And it is unlikely they will hold up the trophy anytime soon, either.

It’s a familiar story at this point. Upon Sir Alex Ferguson’s retirement in 2013, United made a whole host of bad decisions, blowing a fortune on the wrong players and having them coached by the wrong managers. Ole Gunnar Solskjær’s gang are just the latest iteration of how they continue to relieve the same ugly chapter.

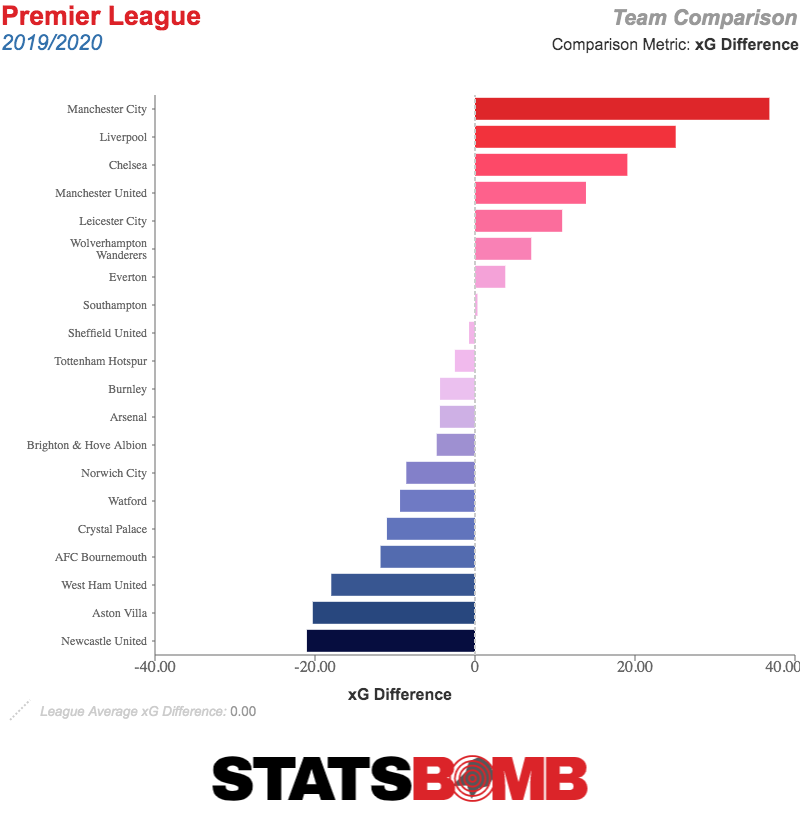

Currently fifth in the table, the underlying numbers show a modest improvement, but nothing drastic. An expected goal difference per game of +0.55 is an entirely respectable fourth-best in the division, with a fairly supercharged Leicester season keeping them out of the Champions League places.

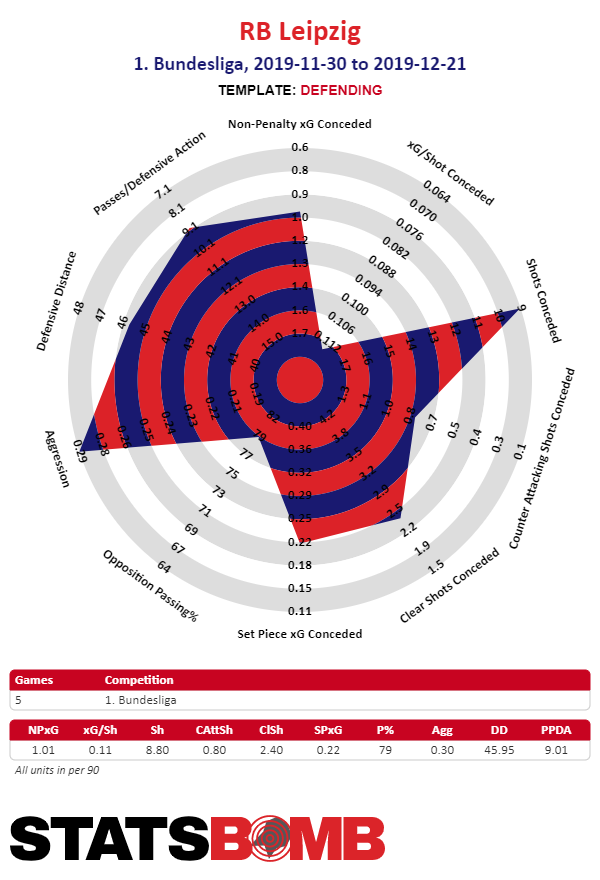

It’s on the defensive end where their real strength lies. United are a good shot suppressing side, with their 10.22 conceded per game the fourth-best in England’s top flight. They combine this with a solid xG per shot conceded of 0.10, the sixth-best in the league and better than the other top shot suppressors. United are not supremely talented at any one aspect of defending, but the strong performance across the board makes them a tough side for any opponent to break down.

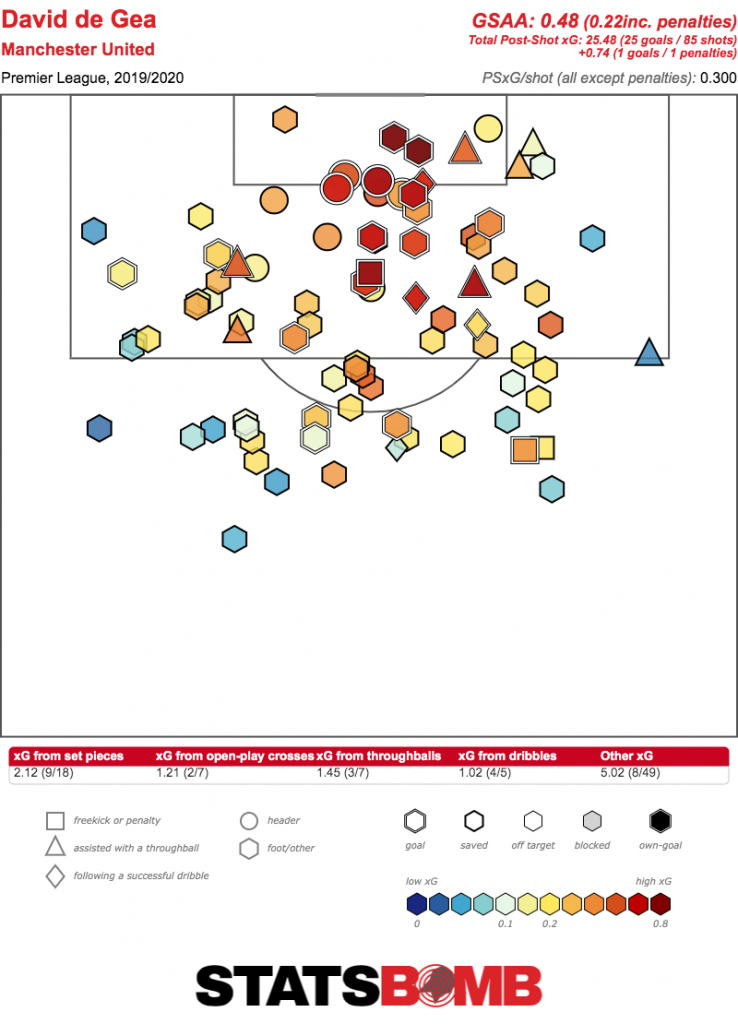

This represents a genuine improvement—and a necessary one— as United no longer have their defensive cheat code. In many of the dark post-Ferguson years, David De Gea almost single-handedly kept his team afloat. His decline has been exaggerated by some, but it’s been a while since he’s performed many heroic feats. He’s looked a smidgen above average this season, and with the difficulty in finding long-term repeatability in xG overperformance, United probably shouldn’t bank on him saving them a significant number of goals going forward.

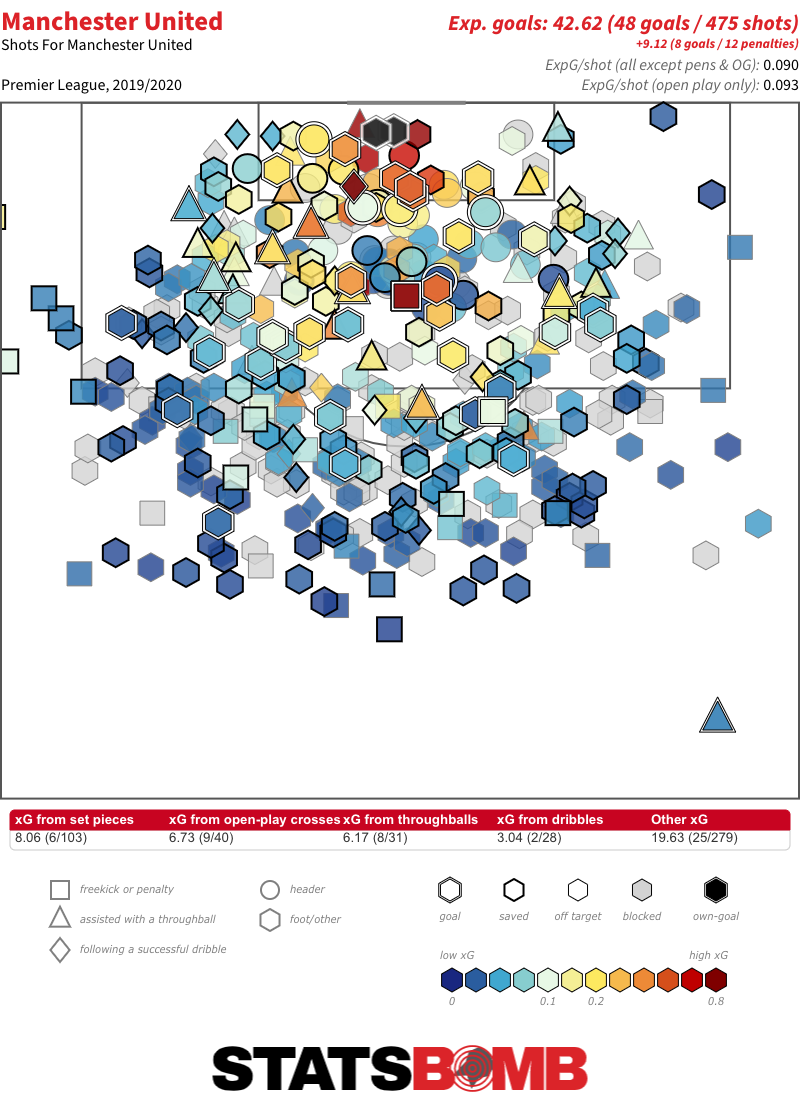

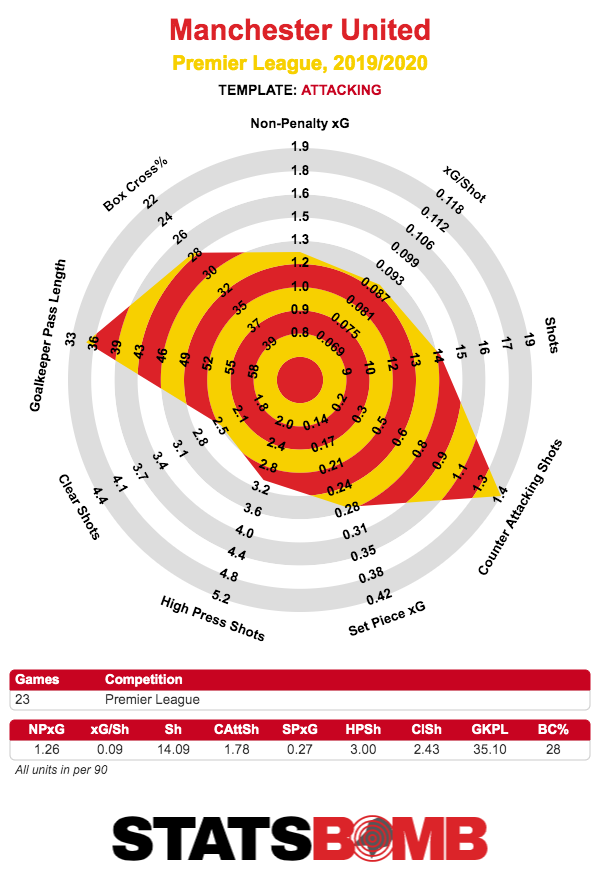

United's defensive solidity has come at the cost of the attack just kind of . . . being there. Their1.26 xG per game is almost exactly the league average. Both their shot volume and quality are fairly mediocre. It’s all very whatever.

The one area where they do clearly excel is in counter-attacking shots. This intuitively makes sense given what we see on the pitch. United’s primary attacking weapons are Marcus Rashford, Anthony Martial and Daniel James, while Jesse Lingard and Mason Greenwood have also stepped in this season. All primarily want to run into open space on the counter rather than build in possession in front of a deep block. A significant part of the side’s disappointing performances is that they don’t have obvious answers when denied the space to launch counter-attacks.

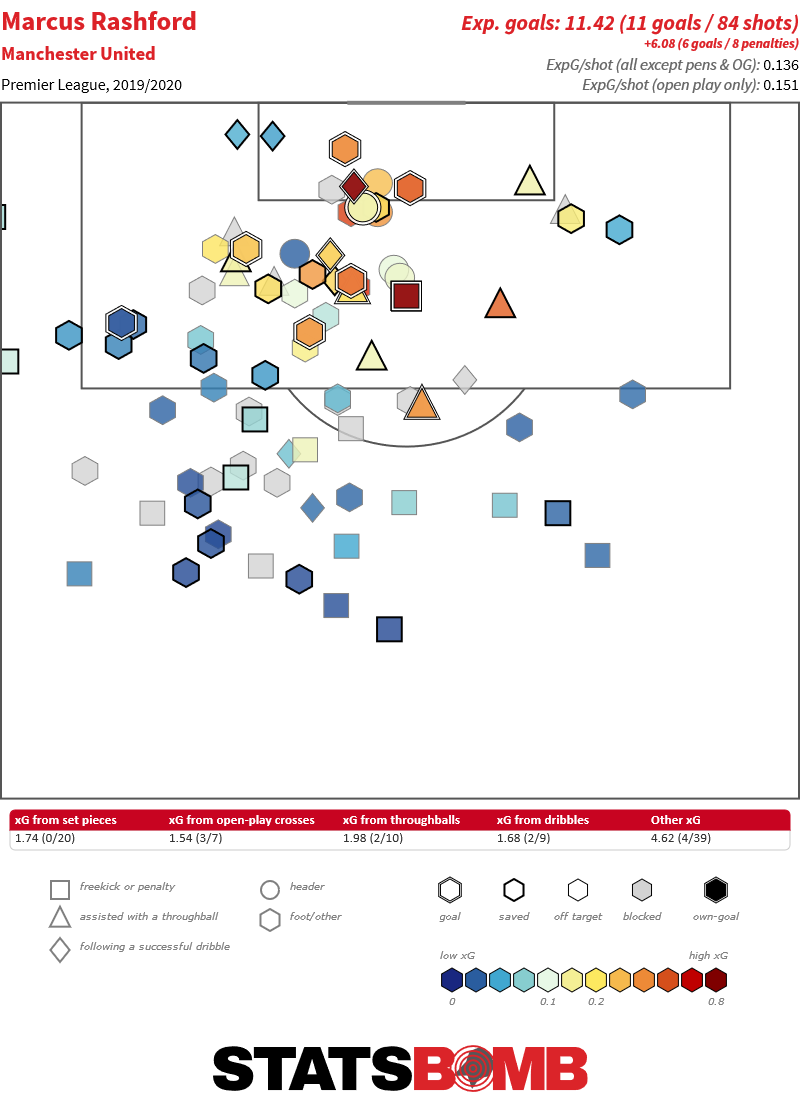

Perhaps surprisingly, Rashford is their primary creator in the final third. He leads the side in open play passes into the box per 90, well ahead of fellow attackers Martial and James, despite not being primarily thought of as a “passer”. That he’s added this to his game recently, in addition to his decent scoring and dribbling threat (as seen below), is impressive, especially given the underlying mediocrity of the team's attack. It’s so frustrating that he's now out injured, given he looks on the cusp of making the leap to being a genuine star.

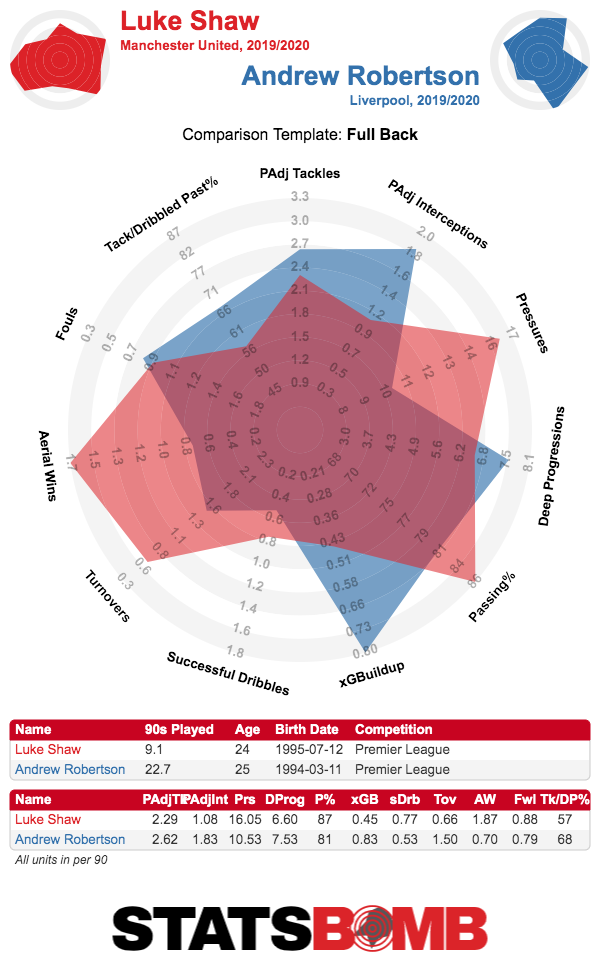

Some might point out that Liverpool also have three attackers who primarily want to counter into open space, and they would be correct. Mohamed Salah, Sadio Mané and Roberto Firmino certainly thrive in counter opportunities much more so than when forced to break down a deep block. Jurgen Klopp’s side, though, have two critical advantages over United. The first is an expertly drilled counter-pressing situation aimed at forcing such opportunities rather than waiting for them to come naturally. The other is their use of the fullbacks as additional playmakers in wide areas, stretching the play and forcing opponents out of a narrow shape with their crossing threat. At right-back, United have Aaron Wan-Bissaka, a defender with a superb ability to shut down opposition wingers but real limitations in possession. He’s better at many things than his Liverpool counterpart Trent Alexander-Arnold, but there’s a humongous gap in quality on the ball when breaking down sides. On the other side, Luke Shaw isn’t incapable, but he lacks both the athleticism and technique that Andy Robertson possesses (Brandon Williams has shown some promise, but at this point nothing more than that). Solskjær’s side do not have the option of creating for their attackers through the fullbacks.

If creating for the attackers through the fullbacks is not a viable option, the work must come from the midfield. Let’s start with the elephant in the room. Paul Pogba has not played a lot of football for United this season and it seems possible that he won’t ever again do so. This would be a great shame, as Pogba is the only midfielder at the club with genuine vision and a consistent ability to move the ball forward into dangerous areas. In his brief appearances this year, mostly early in the season, he’s shown this, unlike everyone else at the club.

After Pogba, United’s player second in deep progressions per 90 is Fred. Yes, Fred is, in Pogba’s absence, the player most responsible for moving the ball into the final third for this team. Next is Ashley Young, but he's now at Inter Milan. It is obvious to pretty much everyone that these players are not the playmakers a club needs to compete at the highest level. This club just does not have playmakers in the side. There are many ways for a team to build well in possession and create opportunities, but no coach has yet devised a system that can consistently create dangerous chances without anyone who’s good on the ball.

This is, first and formost, a squad construction problem. At the very least, no one at the club seems to be under the illusion that this is a squad capable of challenging for major titles, or will be any time soon. After a number of big-name, high-price signings brought in under David Moyes, Louis van Gaal and José Mourinho, the club seem to have accepted that targeting mostly younger players who fit their desired style of football is a much more sustainable model. While none could be dubbed a huge success so far, the summer 2019 signings James, Wan-Bissaka and Harry Maguire have all broadly done what they were bought to do, and by this club’s recent standards that’s a big success. United do have a plan, and seem intent on sticking with it. That’s a marked change from 2013–18.

Having a plan is the first step, and it’s a big one. But the next step is having the expertise to execute it. United need to target and acquire the right younger players capable of high tempo attacking football. That their summer signings consisted of the highest-profile English centre-back, the most promising young right-back in last season’s Premier League not named Alexander-Arnold, and a young winger coached at the international level by Ryan Giggs does not suggest a great reservoir of knowledge lurking within their recruitment setup. The next challenge is to take these players and coach them into a proactive style that fits into the fast-paced, Ferguson-esque mould but who is capable of breaking down the many teams who will sit deep and allow United to keep possession. Solskjær has the aforementioned squad limitations to deal with, but even in their best performances, his side have played reactive, counter-attacking football all season. There has yet to be real evidence of a plan while in possession.

There are any number of talented people working in recruitment at football clubs who would jump at the chance to transform United's process. On the manager side, Mauricio Pochettino is currently sitting at home, while almost any manager not currently in an elite job would be interested in the challenge, prestige and salary delivered by Old Trafford. It’s not that Solskjær is doing a bad job, per se. It’s just that there’s no obvious reason to think he can build the side the club need to challenge for titles again. United are currently looking like a competent side, which seems like a miracle compared to recent years, but it’s still well short of what they need to get back to the top.

Stats of Interest

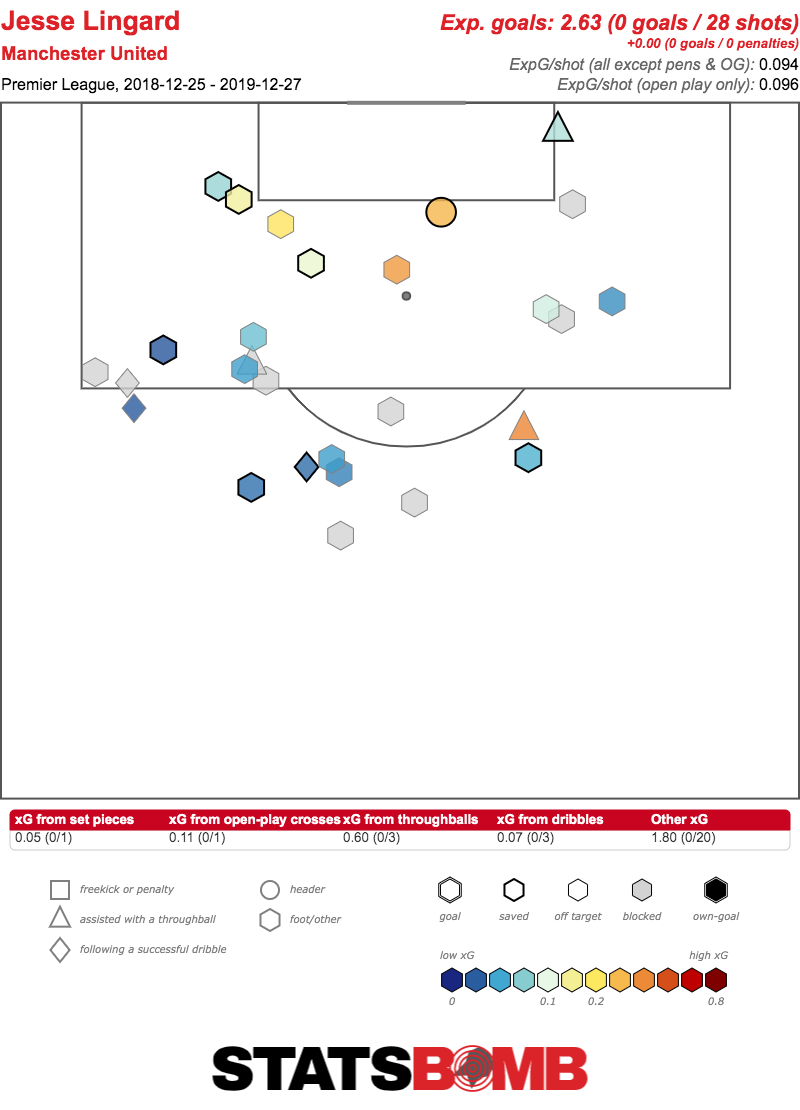

Sticking with Manchester United for a moment, it’s now been over a year since Jesse Lingard last scored a Premier League goal. Considering he did not previously have a reputation for poor finishing, this seems like a bad streak that should come to an end sooner or later.

Alisson became the first goalkeeper this season to earn an assist at the weekend, and on his first key pass of the campaign. But he’s not the most creative goalkeeper in the league. That honour falls to Nick Pope, with 4 key passes adding up to 0.55 xG assisted this season. We all knew Burnley were direct, but using the goalkeeper as an actual attacking weapon like this is quite something.

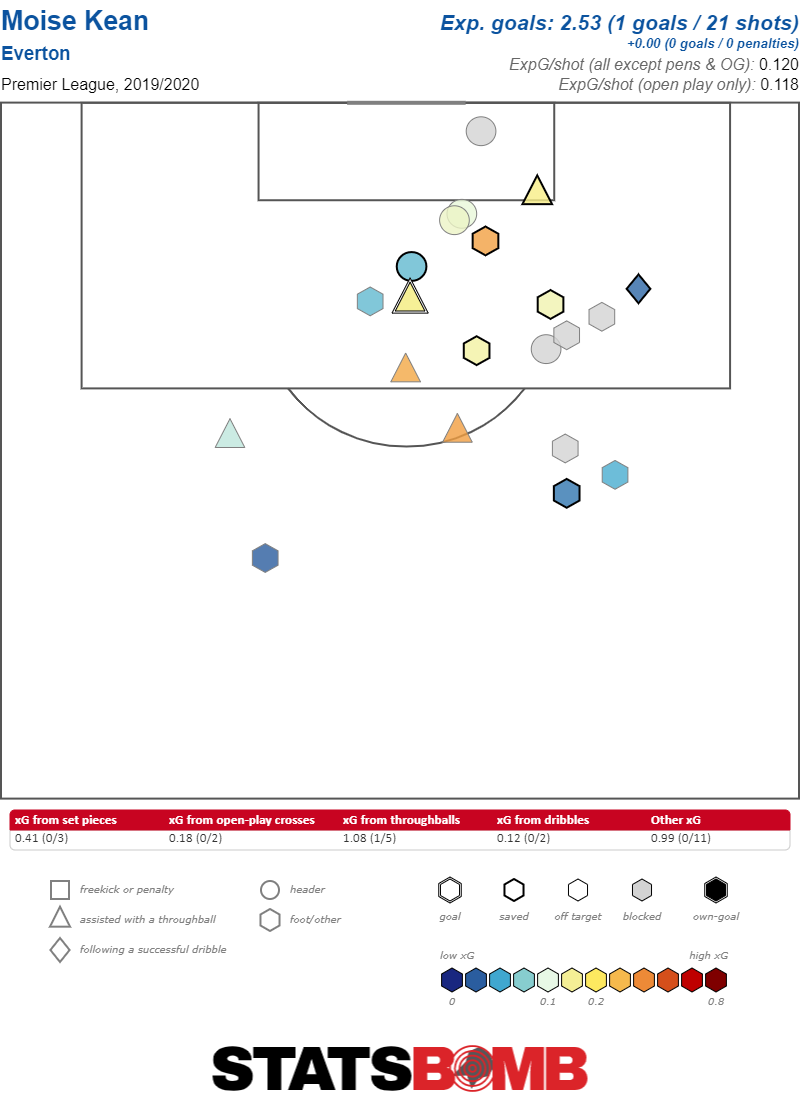

Moise Kean finally got off the mark for Everton last night. It’s been a tough start for him in England, made all the more frustrating by some poor finishing from reasonable production. The goal is overdue, but it may signal the moment when he really kicks on.

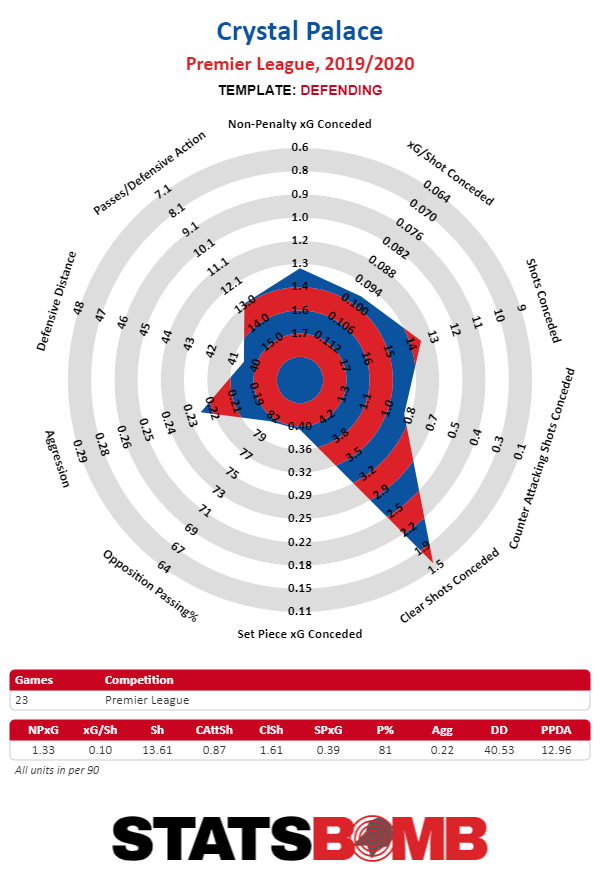

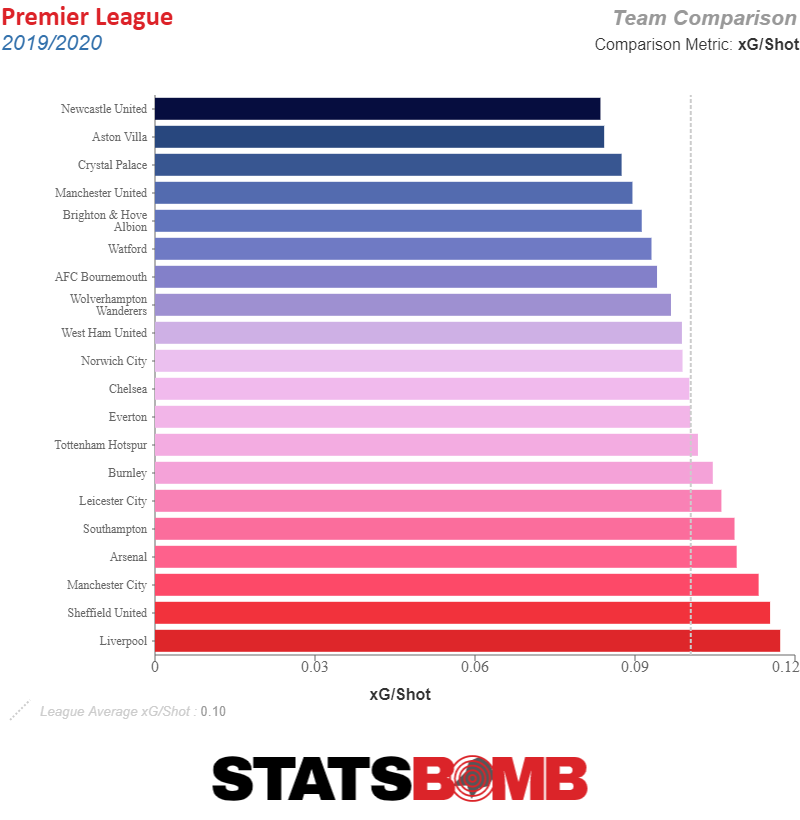

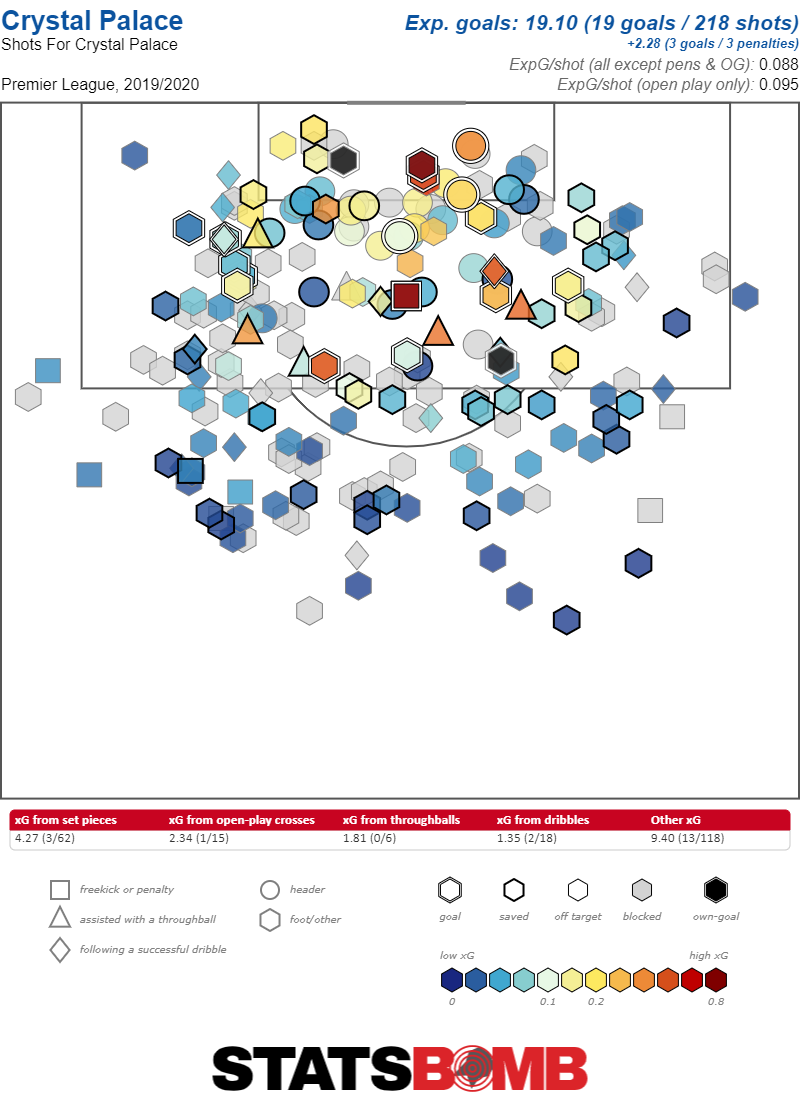

The problems are obvious. Palace only takes 9.39 shots per match, the fewest in the league. Those shots are themselves valued at only 0.09 xG per shot, the third-worst average in the league. So, to paraphrase Yogi Berra: The shots here are terrible and there are so few of them. That’s simply a recipe for attacking futility any way you slice it.

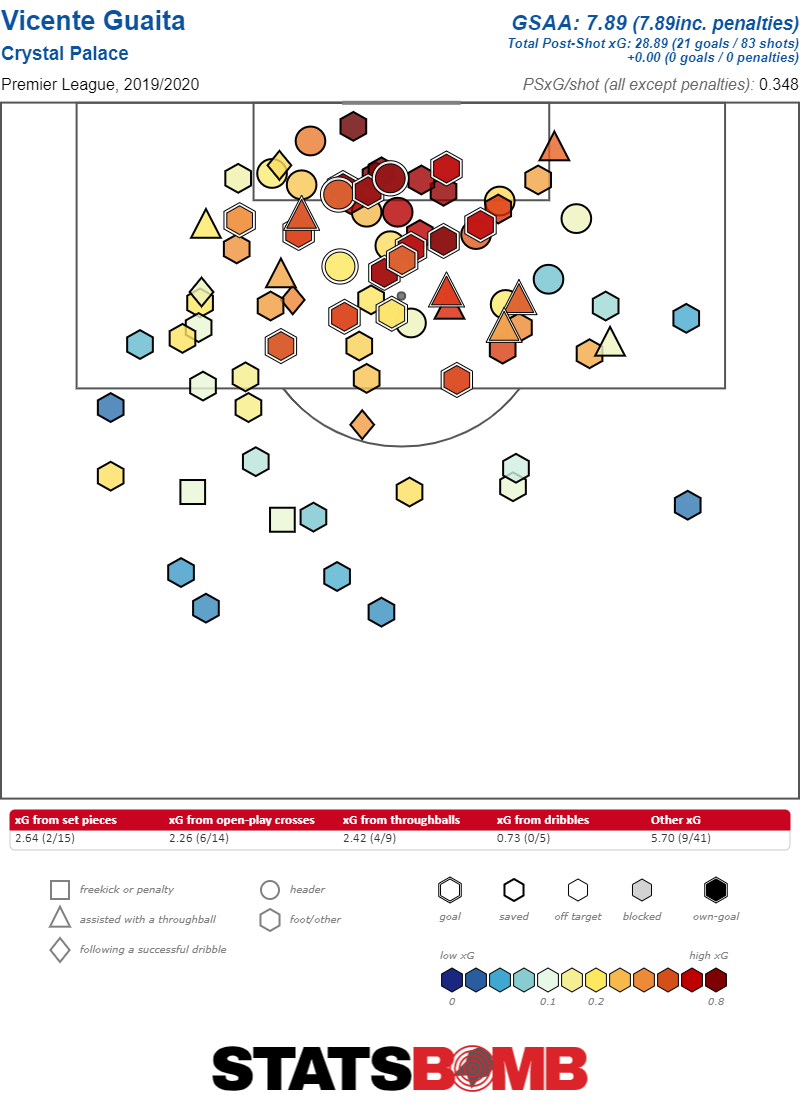

The problems are obvious. Palace only takes 9.39 shots per match, the fewest in the league. Those shots are themselves valued at only 0.09 xG per shot, the third-worst average in the league. So, to paraphrase Yogi Berra: The shots here are terrible and there are so few of them. That’s simply a recipe for attacking futility any way you slice it.  But wait, I hear you cry, surely their defense must be their calling card. Many a successful season has been built on a pathetic attack married to a stalwart, death-defying defense. And it’s true that, at least superficially, Palace is stronger on that side of the ball. They’ve only conceded 26 goals; that’s a great number. Only Liverpool, Leicester City and Sheffield United have conceded fewer. Wow! But here the advanced numbers are a little more useful. Crystal Palace give up a lot of shots. They concede 13.61 per match; only Aston Villa, Newcastle, Norwich, Arsenal and Bournemouth give up more. To their credit, those shots have been largely benign. The average xG per shot of those Palace have conceded is 0.10, a mark only bettered by Wolverhampton, Arsenal, Burnley, Tottenham Hotspur, Norwich City and Manchester United. Lots of shots conceded, but mostly bad shots can be a recipe for an acceptable defense, and that’s exactly what Palace have. Hodgson has his team playing as the 13th best defense in the Premier League with a non-penalty xG conceded per game of 1.33. Of course, that’s a far cry from having conceded the fourth-fewest goals in the Premier League. Enter Vincente Guaita. Want one weird trick for turning your somewhat below-average defensive side into the fourth-best in the league? Have your keeper play absolutely out of his gosh-darned mind. Guaita is single-handedly responsible for saving just below eight goals more than a keeper putting in an average performance might have this season. Add those goals back in and a Palace side that conceded 34 goals would be much less notable. They would, In fact, be awfully close to where xG predicts, with only five teams conceding more than them, and three others conceding the exact same amount.

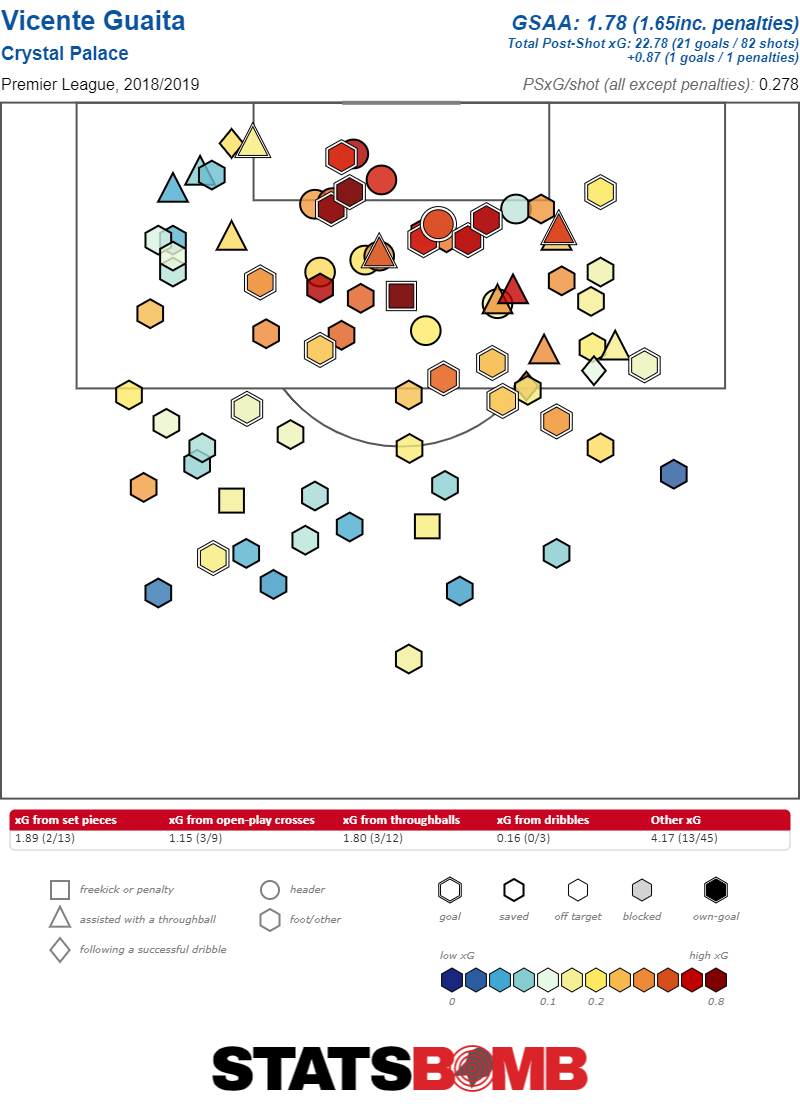

But wait, I hear you cry, surely their defense must be their calling card. Many a successful season has been built on a pathetic attack married to a stalwart, death-defying defense. And it’s true that, at least superficially, Palace is stronger on that side of the ball. They’ve only conceded 26 goals; that’s a great number. Only Liverpool, Leicester City and Sheffield United have conceded fewer. Wow! But here the advanced numbers are a little more useful. Crystal Palace give up a lot of shots. They concede 13.61 per match; only Aston Villa, Newcastle, Norwich, Arsenal and Bournemouth give up more. To their credit, those shots have been largely benign. The average xG per shot of those Palace have conceded is 0.10, a mark only bettered by Wolverhampton, Arsenal, Burnley, Tottenham Hotspur, Norwich City and Manchester United. Lots of shots conceded, but mostly bad shots can be a recipe for an acceptable defense, and that’s exactly what Palace have. Hodgson has his team playing as the 13th best defense in the Premier League with a non-penalty xG conceded per game of 1.33. Of course, that’s a far cry from having conceded the fourth-fewest goals in the Premier League. Enter Vincente Guaita. Want one weird trick for turning your somewhat below-average defensive side into the fourth-best in the league? Have your keeper play absolutely out of his gosh-darned mind. Guaita is single-handedly responsible for saving just below eight goals more than a keeper putting in an average performance might have this season. Add those goals back in and a Palace side that conceded 34 goals would be much less notable. They would, In fact, be awfully close to where xG predicts, with only five teams conceding more than them, and three others conceding the exact same amount.  Clearly you don’t need advanced stats to understand how good Guaita’s been. He plays for Palace and Palace have been the fourth-stingiest team in the league defensively, which alone is a pretty wonderful advert for him. But those fancy numbers make it even clearer. Guaita’s save percentage isn’t all that impressive. At 74.7%, there are five other keepers ahead of him, so he's good but not exceptional. What really makes him pop, though, is that he’s faced an exceptionally difficult caliber of shot. In fact, given the shots he’s faced, an average keeper would only be expected to save 65.2% of them. He’s faced the third-hardest set of shots in the league, which puts the fact that he has the sixth-highest save percentage in an entirely different light. There is nobody in the Premier League with a larger difference between their save percentage and expected save percentage than Guaita. That’s the purest measure of how good a shot stopper a keeper has been. The 9.5% difference puts him ever so slightly ahead of Liverpool’s Alisson as the keeper who has been the best this year at keeping the ball out of the net relative to expectations. The problem for Crystal Palace is that there’s nothing that suggests Guaita’s remarkable season will continue. At 33 years old, the Spaniard has had a solid career, first with Valencia, then over four years with Getafe, before landing in London, but nothing that suggests the spectacular. Last year, his first with Crystal Palace, he was fine. Ironically, he had a very similar save percentage, 74.4%, but shots he faced were considerably easier, and had an expected save percentage of 72.2%. So, he was 2.2% better than expected in his time on the field—nothing to sneeze at, but a far cry from 9.5%.

Clearly you don’t need advanced stats to understand how good Guaita’s been. He plays for Palace and Palace have been the fourth-stingiest team in the league defensively, which alone is a pretty wonderful advert for him. But those fancy numbers make it even clearer. Guaita’s save percentage isn’t all that impressive. At 74.7%, there are five other keepers ahead of him, so he's good but not exceptional. What really makes him pop, though, is that he’s faced an exceptionally difficult caliber of shot. In fact, given the shots he’s faced, an average keeper would only be expected to save 65.2% of them. He’s faced the third-hardest set of shots in the league, which puts the fact that he has the sixth-highest save percentage in an entirely different light. There is nobody in the Premier League with a larger difference between their save percentage and expected save percentage than Guaita. That’s the purest measure of how good a shot stopper a keeper has been. The 9.5% difference puts him ever so slightly ahead of Liverpool’s Alisson as the keeper who has been the best this year at keeping the ball out of the net relative to expectations. The problem for Crystal Palace is that there’s nothing that suggests Guaita’s remarkable season will continue. At 33 years old, the Spaniard has had a solid career, first with Valencia, then over four years with Getafe, before landing in London, but nothing that suggests the spectacular. Last year, his first with Crystal Palace, he was fine. Ironically, he had a very similar save percentage, 74.4%, but shots he faced were considerably easier, and had an expected save percentage of 72.2%. So, he was 2.2% better than expected in his time on the field—nothing to sneeze at, but a far cry from 9.5%.  All of which is to say that the miracle of Crystal Palace stems primarily from their keeper, and their keeper, despite a long history of being pretty good, does not have a history of being miraculous. Sometimes it’s hard to pinpoint where and how the soccer gods are sprinkling their dust. Other times they just straight-up inhabit the body of a journeyman 33-year-old keeper. None of this should be particularly encouraging for Crystal Palace supporters, however. It’s great that Guaita sprouted tree trunk arms for twenty games, which was almost single-handedly enough to push them from relegation battlers to the top half of the Premier League table. Barring an absolutely astounding collapse they’ll remain in the top division to fight another season. But this doesn’t bode well for their long-term health. When those fickle gods alight upon somebody else’s body, Crystal Palace will be left with an anemic attack and a defense that isn’t nearly as strong as Guaita’s form has made it seem. That may not matter this season, but if they don’t figure out how to get better before the next, a relegation battle awaits. And there, but for the soccer gods, will go Crystal Palace.

All of which is to say that the miracle of Crystal Palace stems primarily from their keeper, and their keeper, despite a long history of being pretty good, does not have a history of being miraculous. Sometimes it’s hard to pinpoint where and how the soccer gods are sprinkling their dust. Other times they just straight-up inhabit the body of a journeyman 33-year-old keeper. None of this should be particularly encouraging for Crystal Palace supporters, however. It’s great that Guaita sprouted tree trunk arms for twenty games, which was almost single-handedly enough to push them from relegation battlers to the top half of the Premier League table. Barring an absolutely astounding collapse they’ll remain in the top division to fight another season. But this doesn’t bode well for their long-term health. When those fickle gods alight upon somebody else’s body, Crystal Palace will be left with an anemic attack and a defense that isn’t nearly as strong as Guaita’s form has made it seem. That may not matter this season, but if they don’t figure out how to get better before the next, a relegation battle awaits. And there, but for the soccer gods, will go Crystal Palace.

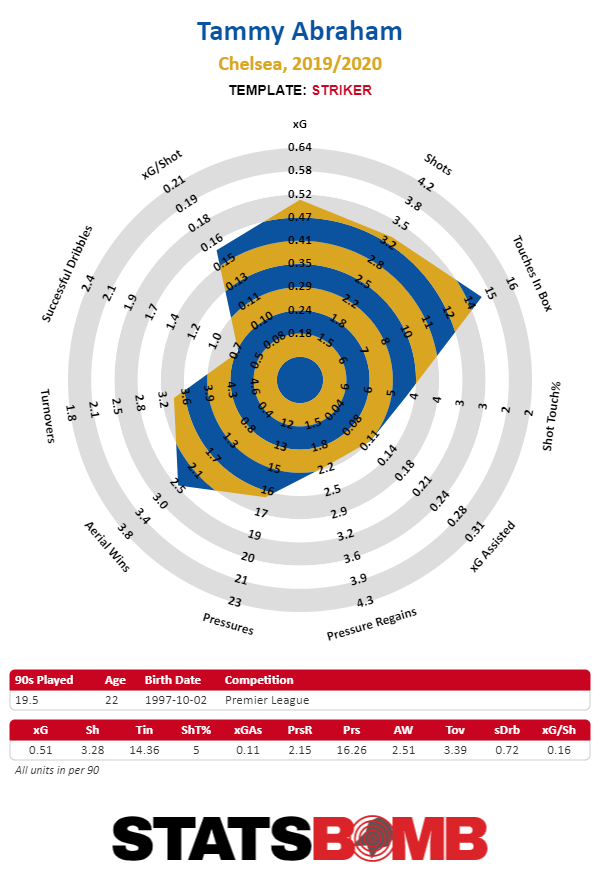

“Compare that [€45m] to the business Brighton did earlier in the summer for German deadball specialist Pascal Gross at €4m” --August 2017 Tammy Abraham

“Compare that [€45m] to the business Brighton did earlier in the summer for German deadball specialist Pascal Gross at €4m” --August 2017 Tammy Abraham

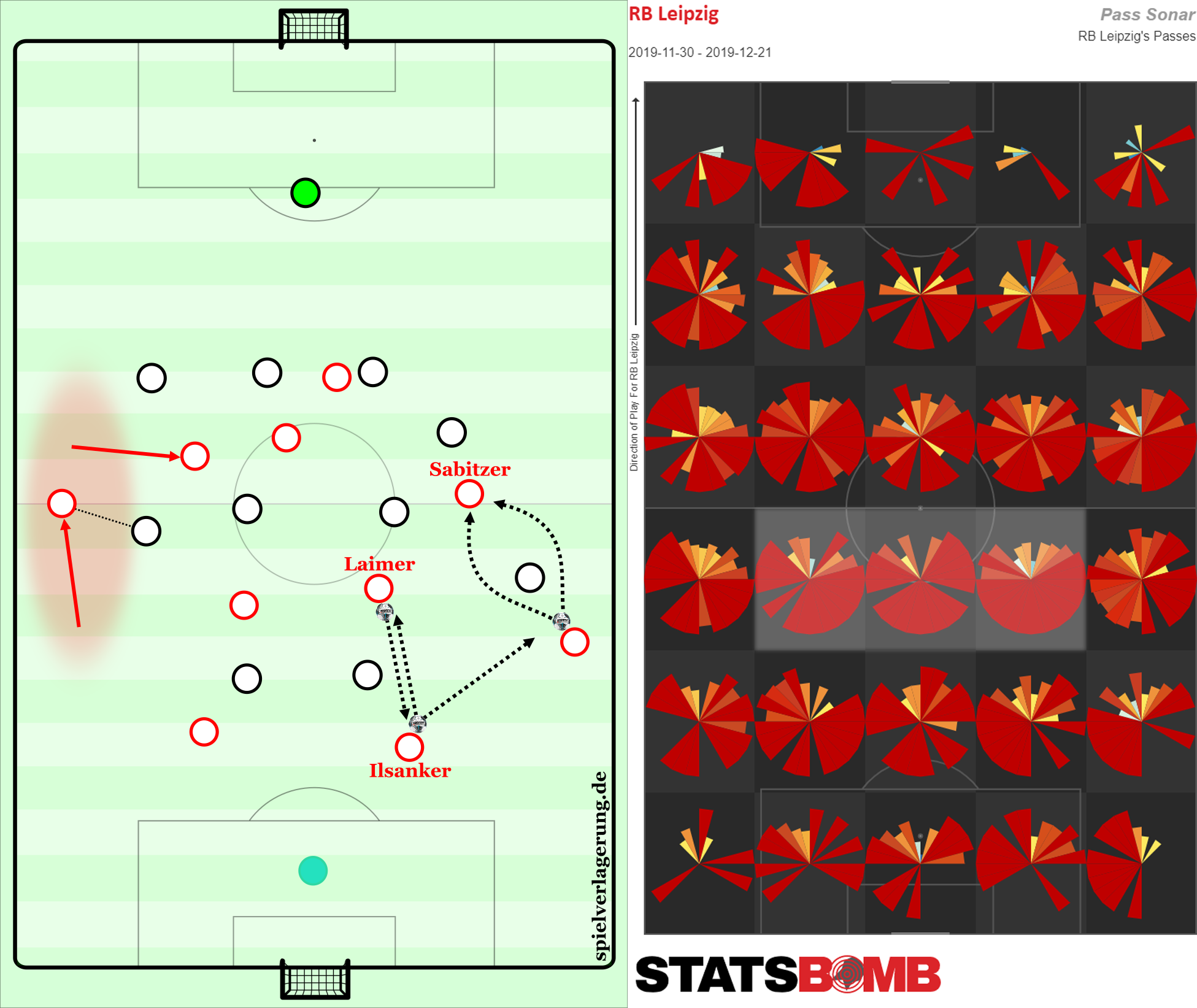

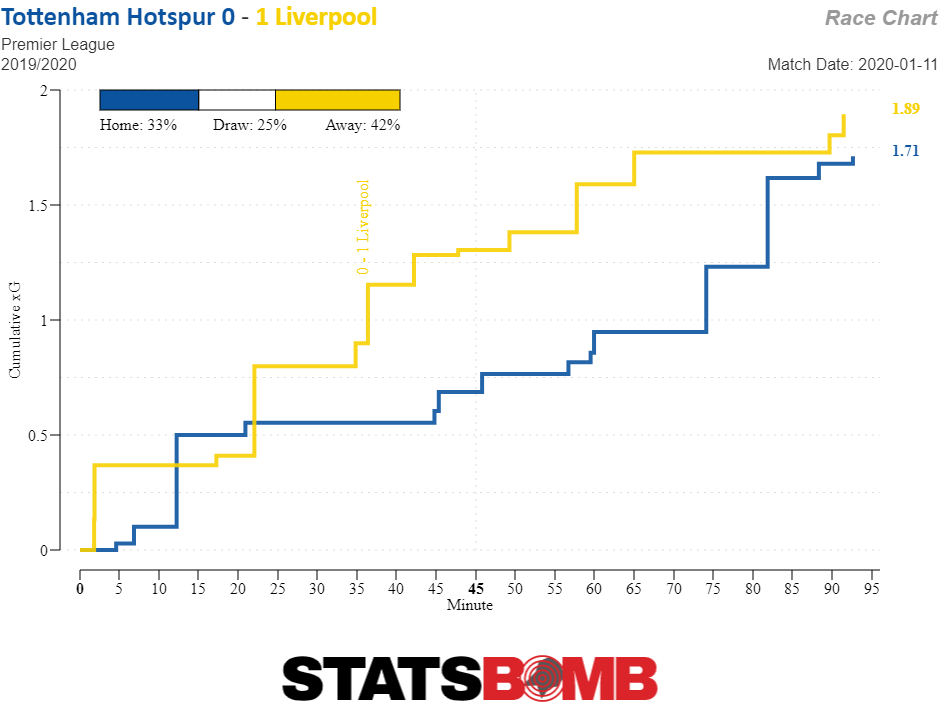

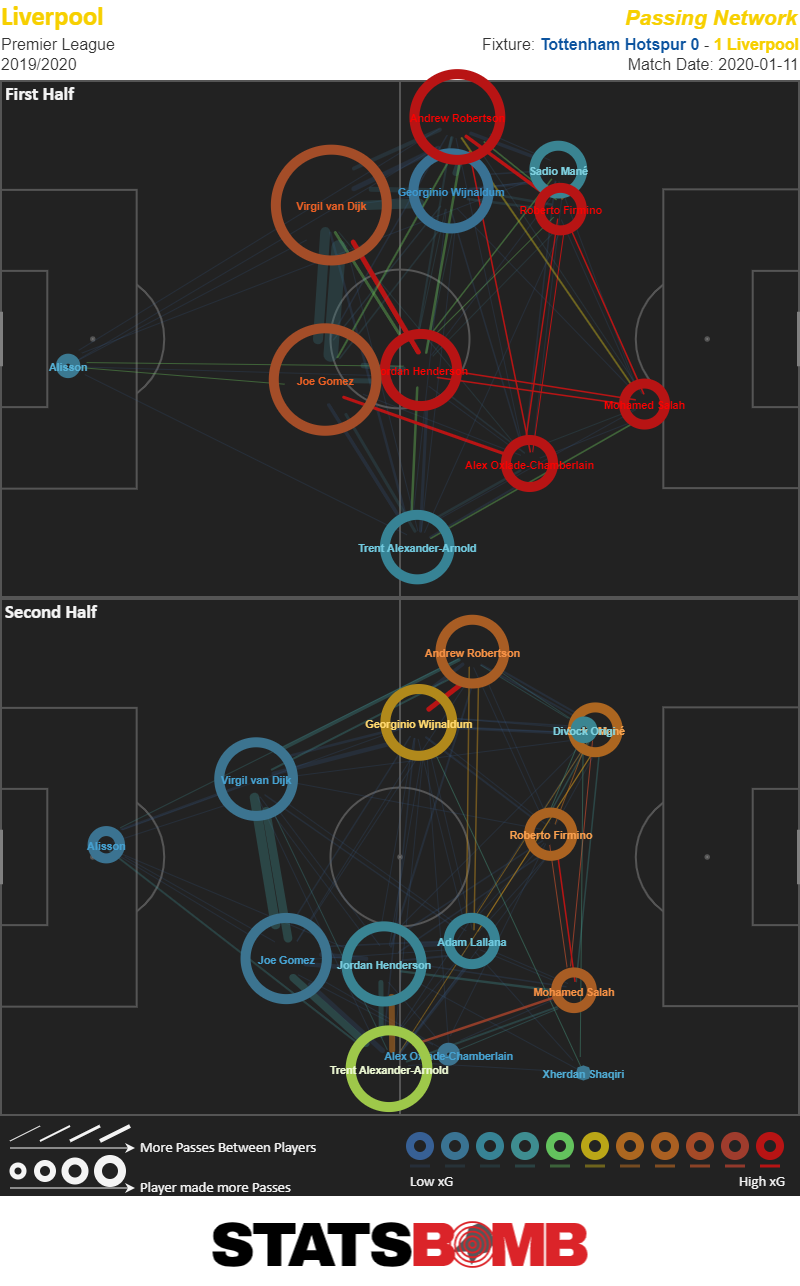

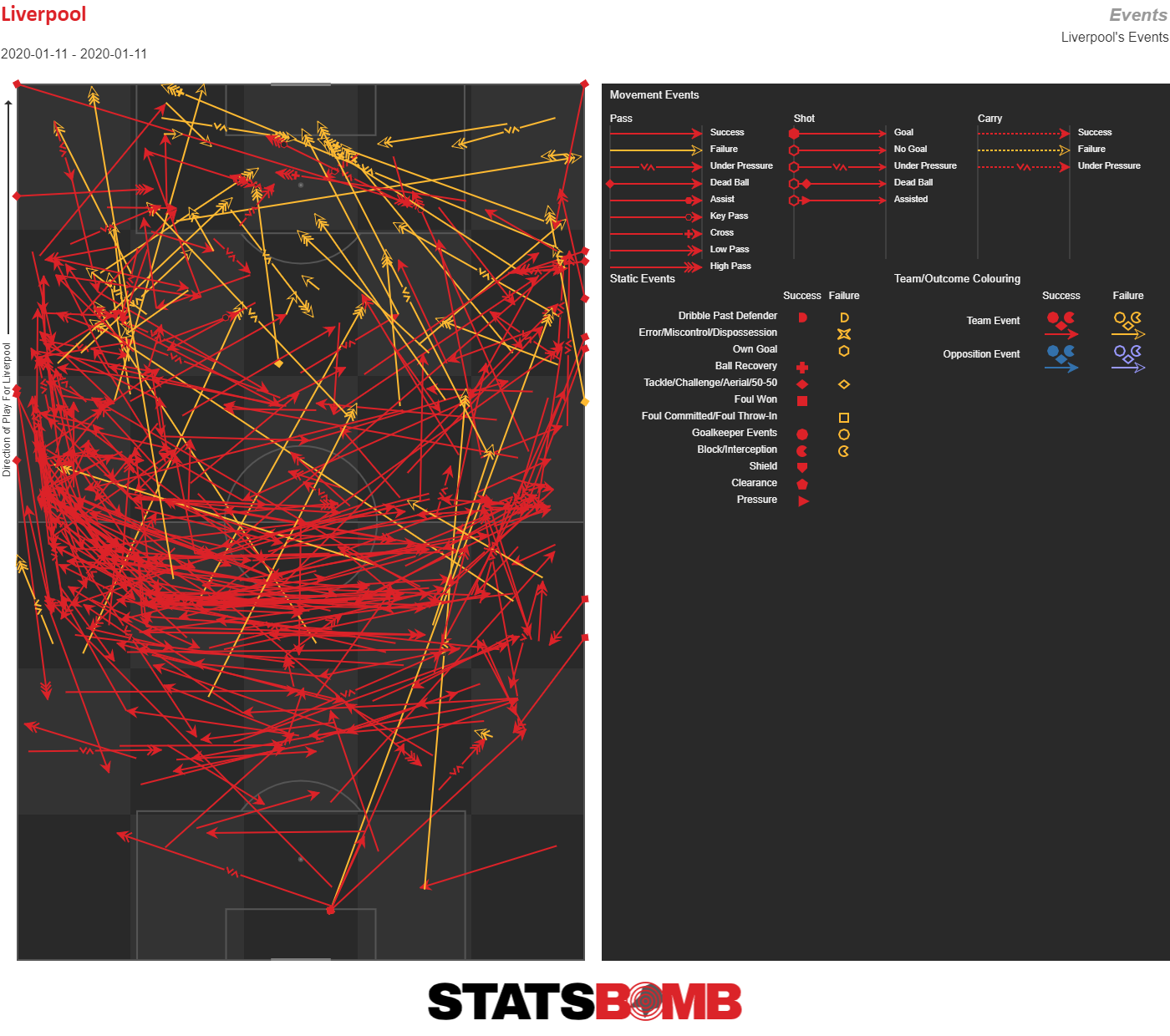

So, what changed? It’s often easy to understand when the rhythm of a match shifts, one team’s attacks seem more dangerous, the other’s stop happening altogether. It’s easy to see the end result of those shifts as well. In this case we can see that Spurs started creating more, and Liverpool’s chances dried up. Jurgen Klopp’s men had exactly one chance between the 59th and 90th minute. But what is it that’s actually changing pass to pass, decision to decision that creates those shifts. Let’s dig into those number. A good first place to start is the basic passing maps. Do they show any major differences between the halves for the two teams. Here’s Liverpool’s first half compared to their second.

So, what changed? It’s often easy to understand when the rhythm of a match shifts, one team’s attacks seem more dangerous, the other’s stop happening altogether. It’s easy to see the end result of those shifts as well. In this case we can see that Spurs started creating more, and Liverpool’s chances dried up. Jurgen Klopp’s men had exactly one chance between the 59th and 90th minute. But what is it that’s actually changing pass to pass, decision to decision that creates those shifts. Let’s dig into those number. A good first place to start is the basic passing maps. Do they show any major differences between the halves for the two teams. Here’s Liverpool’s first half compared to their second.  There are some minor differences between the halves for sure. Notably the connection between Virgil van Dijk and Jordan Henderson is severed and buildup play is consequently forced wider on all accounts. But still, the basic shape remains the same, it’s the color that’s changed. In other words the same shape is producing less in terms of xG. That doesn’t tell us much that we didn’t know before. Now, let’s look at the Spurs side.

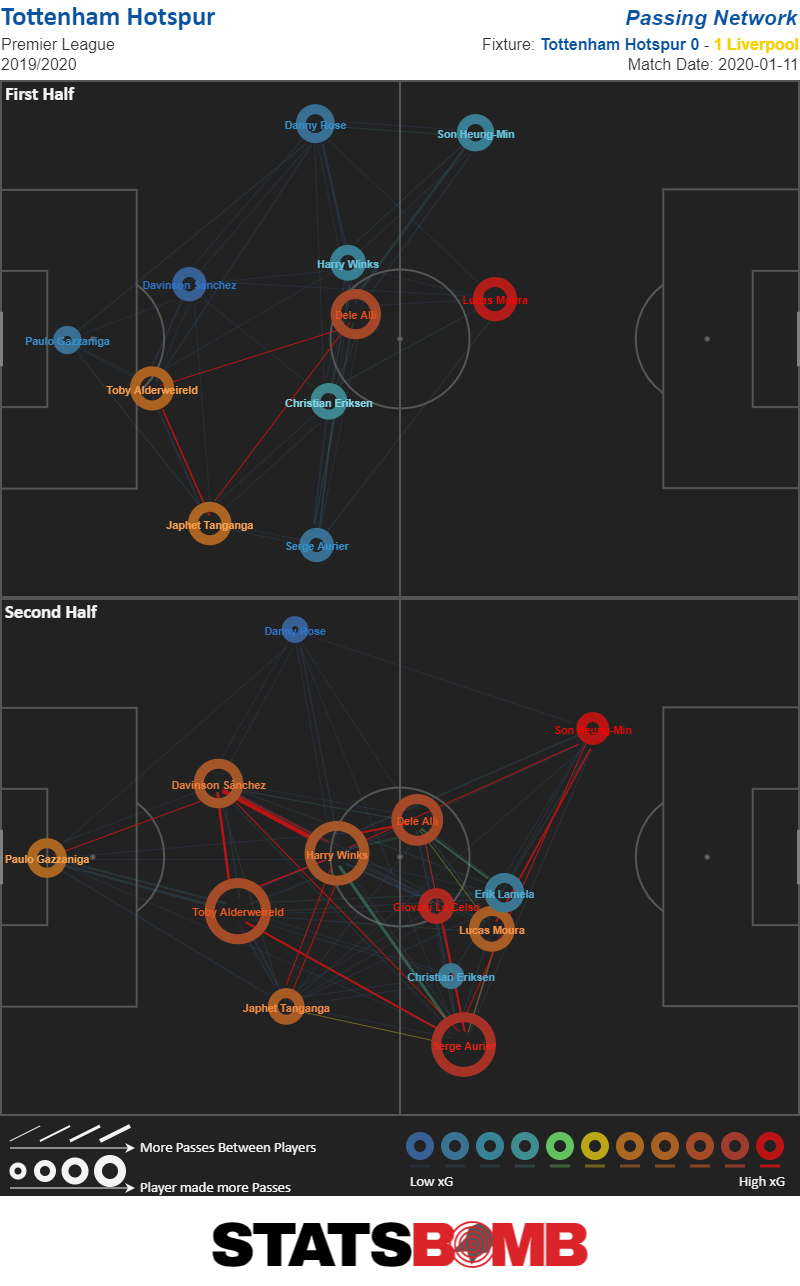

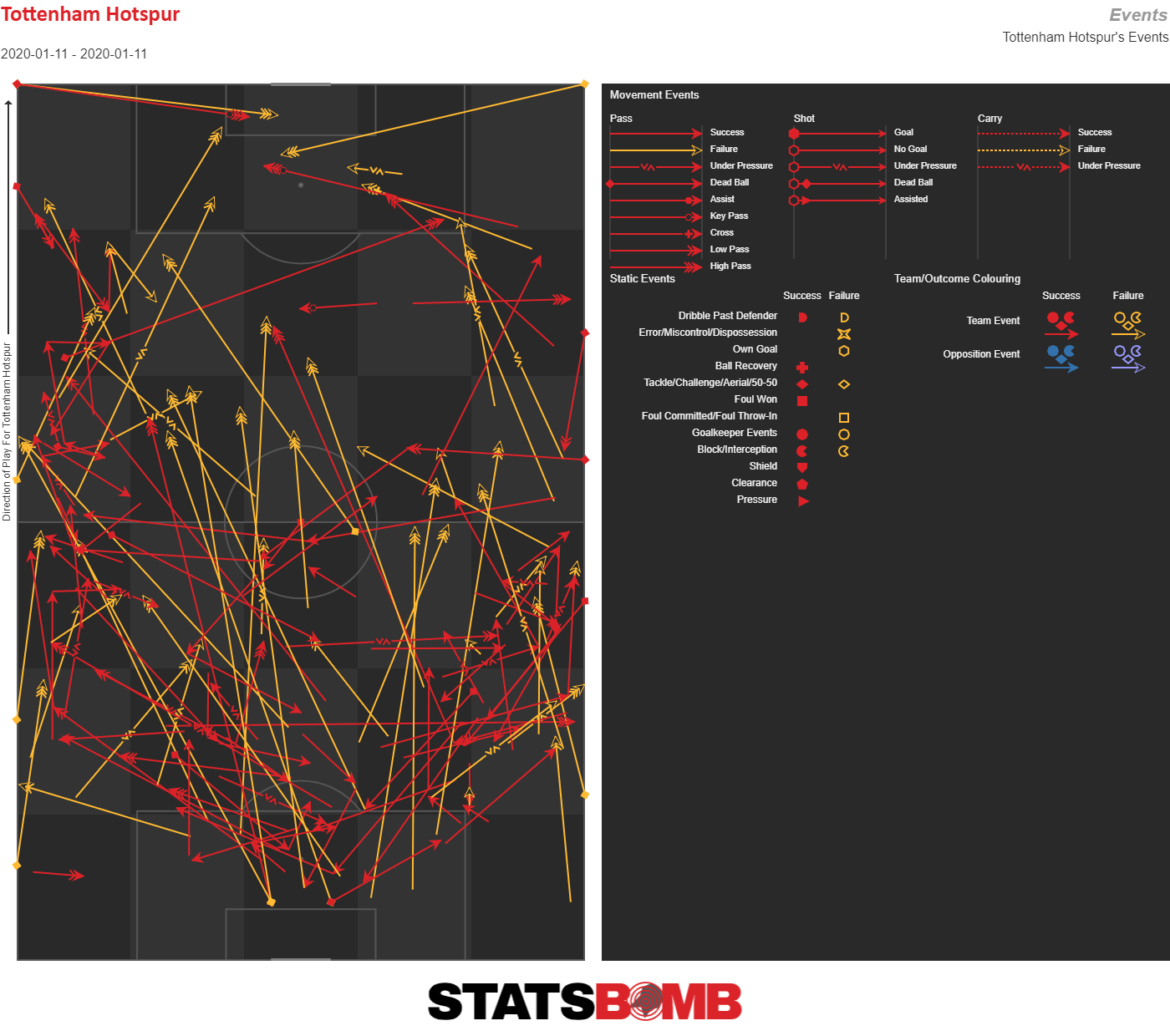

There are some minor differences between the halves for sure. Notably the connection between Virgil van Dijk and Jordan Henderson is severed and buildup play is consequently forced wider on all accounts. But still, the basic shape remains the same, it’s the color that’s changed. In other words the same shape is producing less in terms of xG. That doesn’t tell us much that we didn’t know before. Now, let’s look at the Spurs side.  Now this is a little different. In the first half Dele Alli and Harry Winks are both getting the ball off the center backs. In the second half that responsibility seems to become solely Winks’s. In the first half Son is almost exclusively receiving the ball from the midfielders, and getting it much deeper, while in the second half he’s getting it from other forwards and as a consequence seems to be a much more dangerous threat. There’s another way to visualize this as well. In an individual match we can just look at all the passes a team played and see if splitting them up half to half shows us anything. Here we see Liverpool’s passing in the first half (red for complete, yellow for incomplete). Looking at Liverpool’s first half we see more or less what we’d expect from this side. The team is works the ball from side to side, moves it up the flanks and enters the box.

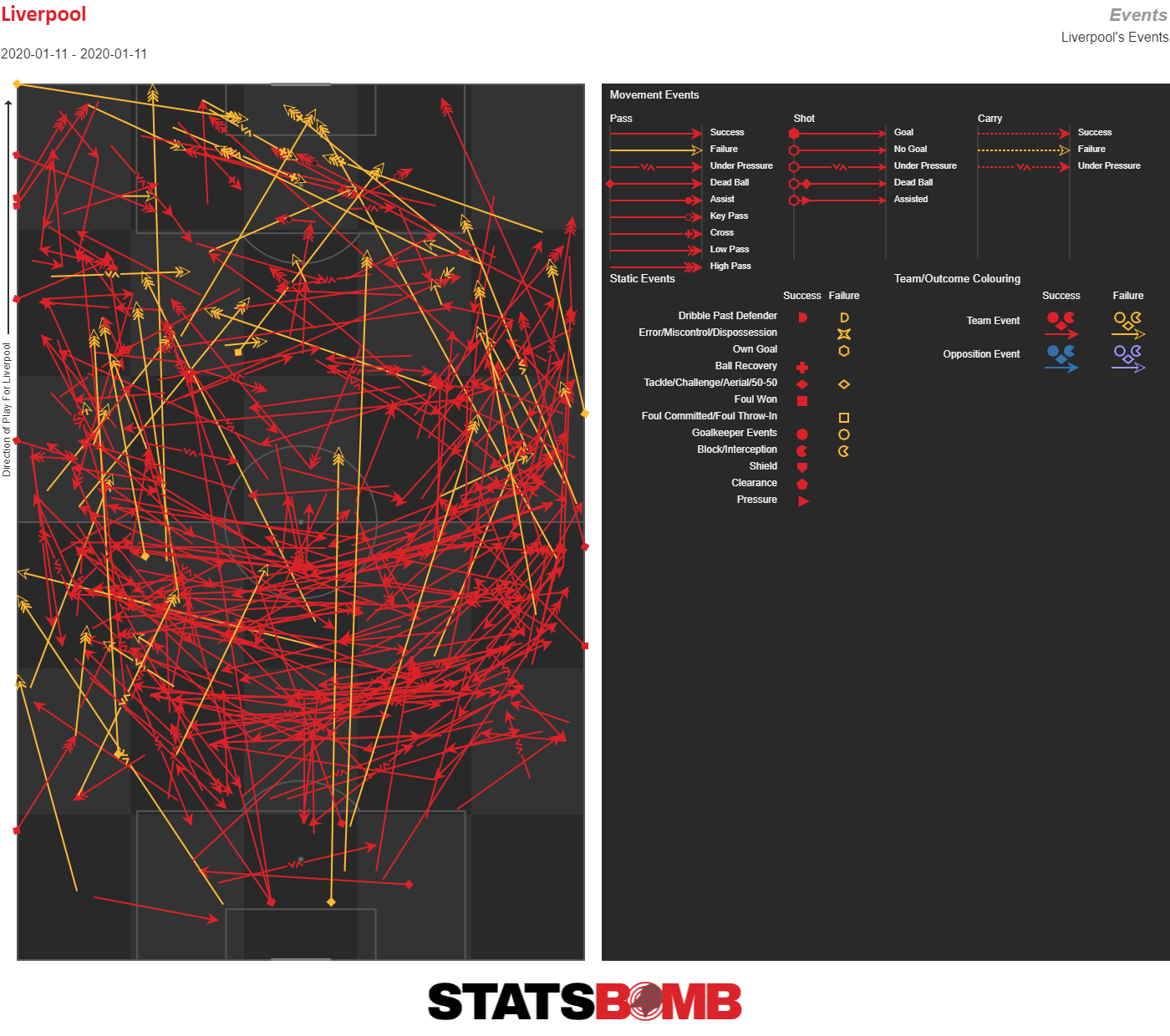

Now this is a little different. In the first half Dele Alli and Harry Winks are both getting the ball off the center backs. In the second half that responsibility seems to become solely Winks’s. In the first half Son is almost exclusively receiving the ball from the midfielders, and getting it much deeper, while in the second half he’s getting it from other forwards and as a consequence seems to be a much more dangerous threat. There’s another way to visualize this as well. In an individual match we can just look at all the passes a team played and see if splitting them up half to half shows us anything. Here we see Liverpool’s passing in the first half (red for complete, yellow for incomplete). Looking at Liverpool’s first half we see more or less what we’d expect from this side. The team is works the ball from side to side, moves it up the flanks and enters the box.  And we see basically the same trend in the second half. This is how Liverpool play. This leaves us still looking for answers about why exactly it is that their attack dried up. The team, broadly, tried to do the same things, it just didn’t work as well.

And we see basically the same trend in the second half. This is how Liverpool play. This leaves us still looking for answers about why exactly it is that their attack dried up. The team, broadly, tried to do the same things, it just didn’t work as well.  Spurs on the other hand, show a remarkably different pattern of play in the first and second half. Here, in the first half we see a team that is just totally unable to get out of their own half. They show a slight preference for launching the ball long and up the left side, presumably trying to get Son in behind, but mostly this is just futility.

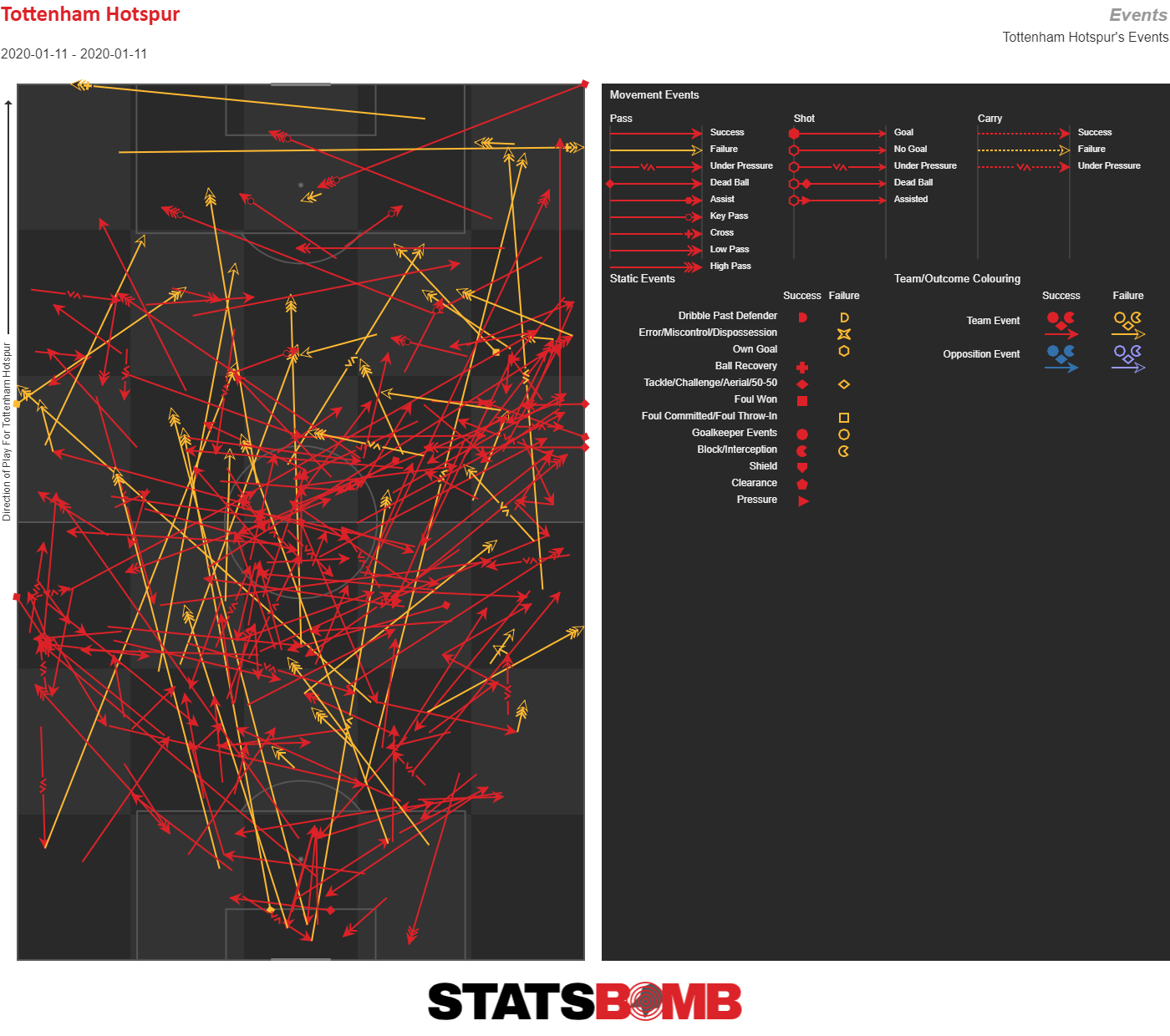

Spurs on the other hand, show a remarkably different pattern of play in the first and second half. Here, in the first half we see a team that is just totally unable to get out of their own half. They show a slight preference for launching the ball long and up the left side, presumably trying to get Son in behind, but mostly this is just futility.  The second half is simply a different story. Instead of attacking the left, Spurs seem to find joy attacking on the right side. Somewhat paradoxically this brought Son into the game. Rather than receiving the ball wide on the flank in relatively isolated positions, like he did in the first half, he was able to received the ball in areas across the pitch, and deeper in Liverpool territory. It’s also worth noting that during the second half Giovanni Lo Celso came onto the pitch for Christian Ericksen and his presence, largely starting from the right side of midfield also likely made an impact.

The second half is simply a different story. Instead of attacking the left, Spurs seem to find joy attacking on the right side. Somewhat paradoxically this brought Son into the game. Rather than receiving the ball wide on the flank in relatively isolated positions, like he did in the first half, he was able to received the ball in areas across the pitch, and deeper in Liverpool territory. It’s also worth noting that during the second half Giovanni Lo Celso came onto the pitch for Christian Ericksen and his presence, largely starting from the right side of midfield also likely made an impact.  So that’s one mystery solved. Spurs attacked differently in the second half and it worked better. But that still leaves the Liverpool mystery. What was it exactly that resulted in their attack dropping from eight shots to five shots and 1.34 xG to 0.59? The answer, unsatisfying as it may be, is not a whole heck of a lot. The shot maps look the same, the passing numbers look the same, all of the open play figures you can find look the same. And that’s because for all intents and purposes, from open play Liverpool’s attack was almost exactly the same in the first half as it was in the second half. In the first half the team had six open play shots for 0.70 xG, or an xG per shot of 0.116. In the second half, the team had five open play shots for 0.59 xG, or an xG per shot of 0.118. One shot of difference is not exactly a tale of two halves. The major difference is that in the first half Liverpool created two set pieces shots worth a combined 0.64 xG. There was, of course, the goal which came from a passage of play that started with a throw-in and then then a Van Dijk header. That’s it, that’s the list. The match between Liverpool and Spurs encapsulates the challenges of understanding the ebbs and flows of a football match. Sometimes what seems like a tale of two halves really is. Spurs attack really did change from the first half to the second half, and that in turn changed the match in tangible ways. But, on the other side of the ball, there wasn’t much difference half to half. Liverpool played the same way, had roughly the same amount of success moving the ball, and simply happened to create both of their strong set piece chances in the first half. There wasn’t anything systemic about it. Sometimes the narrative is real, and sometimes it’s a figment of the randomness of the universe. And sometimes it’s both in the same game. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

So that’s one mystery solved. Spurs attacked differently in the second half and it worked better. But that still leaves the Liverpool mystery. What was it exactly that resulted in their attack dropping from eight shots to five shots and 1.34 xG to 0.59? The answer, unsatisfying as it may be, is not a whole heck of a lot. The shot maps look the same, the passing numbers look the same, all of the open play figures you can find look the same. And that’s because for all intents and purposes, from open play Liverpool’s attack was almost exactly the same in the first half as it was in the second half. In the first half the team had six open play shots for 0.70 xG, or an xG per shot of 0.116. In the second half, the team had five open play shots for 0.59 xG, or an xG per shot of 0.118. One shot of difference is not exactly a tale of two halves. The major difference is that in the first half Liverpool created two set pieces shots worth a combined 0.64 xG. There was, of course, the goal which came from a passage of play that started with a throw-in and then then a Van Dijk header. That’s it, that’s the list. The match between Liverpool and Spurs encapsulates the challenges of understanding the ebbs and flows of a football match. Sometimes what seems like a tale of two halves really is. Spurs attack really did change from the first half to the second half, and that in turn changed the match in tangible ways. But, on the other side of the ball, there wasn’t much difference half to half. Liverpool played the same way, had roughly the same amount of success moving the ball, and simply happened to create both of their strong set piece chances in the first half. There wasn’t anything systemic about it. Sometimes the narrative is real, and sometimes it’s a figment of the randomness of the universe. And sometimes it’s both in the same game. Header image courtesy of the Press Association