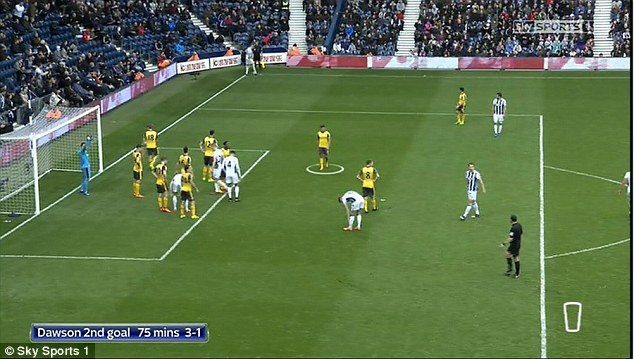

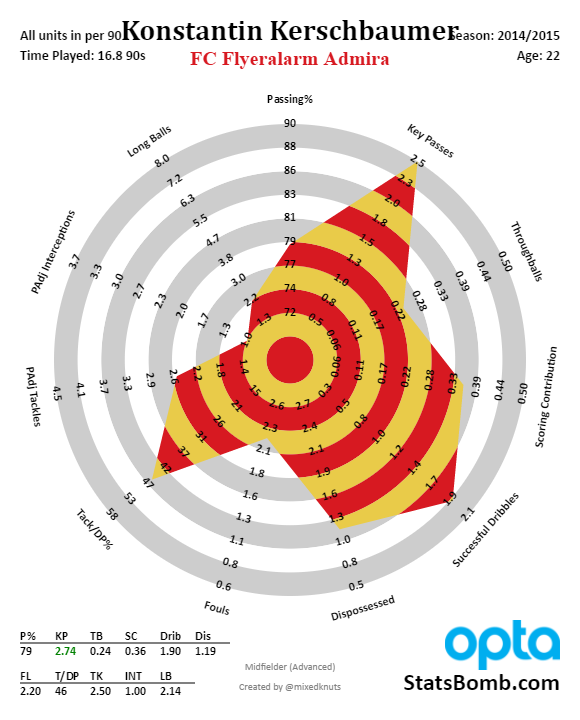

In statistics, you rarely care about the outliers. If the data set is big enough, these are naturally occurring, but generally we want information about trending in the population as a whole. Outliers are something to be discarded. In sports, outliers are everything. In summer 2015, I was lucky enough to head up recruitment for Brentford football club in West London. We had to rebuild everything that McParland and Warburton took with them, and we had to do it from scratch, which meant scouting, market knowledge, player fit, etc. It was a monumental task, but we ended up with a really good recruitment team of Ricardo Larrandart, Nikos Overheul, Mark Andrews, and Robert Rowan, and a couple of part-time scouts including tactical superstar Rene Maric. From the point we knew Warbs was leaving until the close of the summer transfer window was one of the craziest and most exciting times of my life. We were both researching and applying statistical football theory to the transfer market on the fly. How well would players from various leagues translate to the English Championship? What was the lowest price we could pay for players and still get them? Could we rebuild an ageing squad into something that could potentially challenge for a promotion place again while playing an attractive, positive style? This is one of the stories from that summer... We knew we definitely weren’t getting Alex Pritchard back on loan. After finishing in the Championship Team of the Season in 14-15, Spurs wanted to keep him in training camp and then likely loan him out another rung up the ladder. There was the briefest chance we could get Dele Alli, but that quickly dissipated as he wowed Poch in training. This left a big hole for us in the 8/10 position. Our first choice was to get Arsenal’s Jon Toral back on loan. Toral was tremendous in limited minutes for Brentford in the playoff season, and his profile was unlike anyone else we could get in our price range. I sat next to him and talked him through what I saw from the numbers and what his age corollaries were in the data set. He seemed smart and interested. Unfortunately, somehow [former head coach] Marinus dragged his feet on whether Toral was the right fit. He was slow to make up his mind or get in touch with the player. Jon apparently was guaranteed starter minutes at Birmingham, and POOF! What seemed like a great fit flew right out the window, leaving us without a first-choice AMC. Owner Matthew Benham had negotiated to bring in Andy Gogia from Bundesliga 3’s Hallescher on a free in the spring. He could fill the role, but a bit like Alan Judge, we thought he would be better as a creative passer and dribbler out wide. (We also had Judge as a potential 8 because his defensive numbers were so good, but that never quite worked out.) We could not get Pascal Gross or Ziyech, and no one else was super exciting. Faced with a ticking clock and a very low budget that we would prefer to spend elsewhere, I put this Austrian guy no one had ever heard of back into the scouting queue. The data suggested he was a solid attacking midfielder who could dribble and had the great ability to create shots for teammates. He also had reasonable tackling stats for a guy who primarily attacked, and scouting agreed that he was decent at pressing. Now this was clearly a risk. At no time did we ever think, “Yes, this guy will be great in the Championship.” Instead we thought, “For the right price and in the right role, he certainly shows enough potential to be a solid performer in England.” Everything in transfers comes down to money. Are you paying the right price for the talent and the risk involved? In Brentford's budget, half a million pounds is a big deal, and a difference of £500K in valuation will kill a deal. In a Premier League budget, half a million pounds is chump change, and you'd be an idiot for missing out on a player for that small an amount.  The numbers lined up and scouting was positive, so we needed to get in touch with his club and his agent to find out if we could afford him. That’s where the Chris Palmer story came from. [Scroll to the bottom here.] An eventual deal was sealed for low six-figures, and we had ourselves a low-cost wildcard of a 10 with potential upside. Even if Kersch was a bust, he was still probably cheaper than anyone we could have signed from League One, and for a club like Brentford, that mattered. The Real World Kerschbaumer showed up at training camp in amazing shape, and tested for the highest vO2 max in the group. Dude could run for days. It was all very exciting back then. Unfortunately, things in football go weird sometimes. Brentford went through three head coaches that season and by the end of it no one really knew he was supposed to play 10 except the recruitment guys. He basically never played at AMC until the dead end of the season in 15-16. Brentford had a horrible winter run, and things looked very grim. The club announced the closing of the academy and also the Football Analytics Team – my group – was made redundant as part of cost-cutting efforts. We had already finished most of the recruitment workload for the 16-17 season, and the perception was that the squad we had recruited was struggling mightily. Now the truth was that we intentionally built a youngish squad with the blessing of the owner because that is what we could afford, and also so that they could potentially grow and improve together. As long as your recruitment is good, this is a good plan. Then a funny thing happened. Brentford had an amazing run-in. From April 2nd at Nottingham Forest until the close of the season, they only lost one match, against eventual promoted side Hull. They also won six and drew two, most of which was without player of the season Alan Judge, who broke his leg in a nasty tackle at Ipswich. Scott Hogan finally came back from two different ACL injuries to be the hottest scorer in the league. Yoann Barbet started regularly with Harlee Dean in central defense, displaying an impressive passing range from his left boot, and a team that could not win a match from Christmas through February suddenly could not lose. Brentford finished 9th. Without the poor start from the Dijkhuizen era, they might have been right back in the playoff mix. Additionally, they did it with a massive surplus of transfer fees. Worst case scenario, performance suffered a little but the club was now making big money in the transfer market. Lost in this was Kerschbaumer’s performance. He subbed on when Judge broke his leg at Ipswich and set up Sam Saunders for the first Brentford goal. He also created an early goal for Hogan against Fulham, and two more in the final match of the season at Huddersfield. Then the summer came and seemingly Brentford once again forgot about Kerschbaumer. This wasn’t unfair – Brentford had a lot of competition for the midfielder roles, and Romaine Sawyers, Ryan Woods, Nico Yennaris, and Josh McEachran shared the bulk of the minutes. Injuries bit throughout the season though, and Kerschbaumer finally started to see more playing time, once again in the spring. Since March 18th, Brentford have lost once, drawn twice, and won five times. And once again, KK is out there racking up assists. Why the long story about a bit player in a small Championship team?

The numbers lined up and scouting was positive, so we needed to get in touch with his club and his agent to find out if we could afford him. That’s where the Chris Palmer story came from. [Scroll to the bottom here.] An eventual deal was sealed for low six-figures, and we had ourselves a low-cost wildcard of a 10 with potential upside. Even if Kersch was a bust, he was still probably cheaper than anyone we could have signed from League One, and for a club like Brentford, that mattered. The Real World Kerschbaumer showed up at training camp in amazing shape, and tested for the highest vO2 max in the group. Dude could run for days. It was all very exciting back then. Unfortunately, things in football go weird sometimes. Brentford went through three head coaches that season and by the end of it no one really knew he was supposed to play 10 except the recruitment guys. He basically never played at AMC until the dead end of the season in 15-16. Brentford had a horrible winter run, and things looked very grim. The club announced the closing of the academy and also the Football Analytics Team – my group – was made redundant as part of cost-cutting efforts. We had already finished most of the recruitment workload for the 16-17 season, and the perception was that the squad we had recruited was struggling mightily. Now the truth was that we intentionally built a youngish squad with the blessing of the owner because that is what we could afford, and also so that they could potentially grow and improve together. As long as your recruitment is good, this is a good plan. Then a funny thing happened. Brentford had an amazing run-in. From April 2nd at Nottingham Forest until the close of the season, they only lost one match, against eventual promoted side Hull. They also won six and drew two, most of which was without player of the season Alan Judge, who broke his leg in a nasty tackle at Ipswich. Scott Hogan finally came back from two different ACL injuries to be the hottest scorer in the league. Yoann Barbet started regularly with Harlee Dean in central defense, displaying an impressive passing range from his left boot, and a team that could not win a match from Christmas through February suddenly could not lose. Brentford finished 9th. Without the poor start from the Dijkhuizen era, they might have been right back in the playoff mix. Additionally, they did it with a massive surplus of transfer fees. Worst case scenario, performance suffered a little but the club was now making big money in the transfer market. Lost in this was Kerschbaumer’s performance. He subbed on when Judge broke his leg at Ipswich and set up Sam Saunders for the first Brentford goal. He also created an early goal for Hogan against Fulham, and two more in the final match of the season at Huddersfield. Then the summer came and seemingly Brentford once again forgot about Kerschbaumer. This wasn’t unfair – Brentford had a lot of competition for the midfielder roles, and Romaine Sawyers, Ryan Woods, Nico Yennaris, and Josh McEachran shared the bulk of the minutes. Injuries bit throughout the season though, and Kerschbaumer finally started to see more playing time, once again in the spring. Since March 18th, Brentford have lost once, drawn twice, and won five times. And once again, KK is out there racking up assists. Why the long story about a bit player in a small Championship team?  The answer is because Konstantin Kerschbaumer is a major outlier. Combine his minutes across two seasons and you get the following: 2320 minutes, 1 goal, 12 assists. That’s an assist rate of about .47 per 90, which is in the top 3% of footballers. Kersch also doesn’t take set pieces, meaning nearly all of his assists come from open play. To give you an idea of how unusual this is, in the last four seasons in the Championship nine players have posted 12 assists or more, all with more minutes and nearly all of them taking set pieces. Assists are really valuable – I view them basically the same as goals. Fans still have a very different perspective if a player scores half a goal a game than if he creates half an assist a game, there's a decent case to say they shouldn't. The bulk of Kerschbaumer’s minutes also came during that first year, many of which were not in his natural position. That's a tough situation to succeed in, but his numbers in this one particularly valuable area continue to be crazy. Is Kerschbaumer a success? I have no idea. It would be hard for Brentford to lose money on his transfer should he leave the club, so if that's how you grade success, I guess it's a check mark. He's also produced exactly what I thought he could when we recruited him. But... there are questions about whether he does enough on the pitch when he plays, and I can certainly see why those exist. I think he's still learning, and I hope he ends up with starter minutes next season, preferably in a system that plays him in his natural AMC spot. Like most data scientists, I want more data and preferably a lot of it. Part of me roots for the players we recruited like they are my children. I want them to succeed no matter what. There's also a part of me that is scientifically evaluating their successes and failures to see what worked, and what I need to do better the next time I have a chance to dabble in the transfer market. Anyway, the combination of Kersch's crazy assist rate in the run-in and Fabregas's continued creative skills for Chelsea made me think back to four years ago, when I first started writing about player stats. So much has changed in my approach, but remarkably, so much is still similar. I think a lot of the early ideas I latched on to as mattering ended up being very valuable. That said, I have made plenty of mistakes along the way, both inside and outside of football. Making mistakes - and learning from them - is most of the fun. Ted Knutson @mixedknuts ted@statsbombservices.com *Thanks again to Matthew Benham for the chance to do all of this while learning on the fly. Looking at the quality in the squad right now, I think we did pretty well.

The answer is because Konstantin Kerschbaumer is a major outlier. Combine his minutes across two seasons and you get the following: 2320 minutes, 1 goal, 12 assists. That’s an assist rate of about .47 per 90, which is in the top 3% of footballers. Kersch also doesn’t take set pieces, meaning nearly all of his assists come from open play. To give you an idea of how unusual this is, in the last four seasons in the Championship nine players have posted 12 assists or more, all with more minutes and nearly all of them taking set pieces. Assists are really valuable – I view them basically the same as goals. Fans still have a very different perspective if a player scores half a goal a game than if he creates half an assist a game, there's a decent case to say they shouldn't. The bulk of Kerschbaumer’s minutes also came during that first year, many of which were not in his natural position. That's a tough situation to succeed in, but his numbers in this one particularly valuable area continue to be crazy. Is Kerschbaumer a success? I have no idea. It would be hard for Brentford to lose money on his transfer should he leave the club, so if that's how you grade success, I guess it's a check mark. He's also produced exactly what I thought he could when we recruited him. But... there are questions about whether he does enough on the pitch when he plays, and I can certainly see why those exist. I think he's still learning, and I hope he ends up with starter minutes next season, preferably in a system that plays him in his natural AMC spot. Like most data scientists, I want more data and preferably a lot of it. Part of me roots for the players we recruited like they are my children. I want them to succeed no matter what. There's also a part of me that is scientifically evaluating their successes and failures to see what worked, and what I need to do better the next time I have a chance to dabble in the transfer market. Anyway, the combination of Kersch's crazy assist rate in the run-in and Fabregas's continued creative skills for Chelsea made me think back to four years ago, when I first started writing about player stats. So much has changed in my approach, but remarkably, so much is still similar. I think a lot of the early ideas I latched on to as mattering ended up being very valuable. That said, I have made plenty of mistakes along the way, both inside and outside of football. Making mistakes - and learning from them - is most of the fun. Ted Knutson @mixedknuts ted@statsbombservices.com *Thanks again to Matthew Benham for the chance to do all of this while learning on the fly. Looking at the quality in the squad right now, I think we did pretty well.

Author: Ted Knutson

It's NOT the Same Old Arsenal

Around football right now, we seem to be hearing that Arsenal are basically the same as every other year, but all the clubs around them have improved. Our numbers suggest that's not the case, and Arsenal's performance on both sides of the ball has fallen off this season.

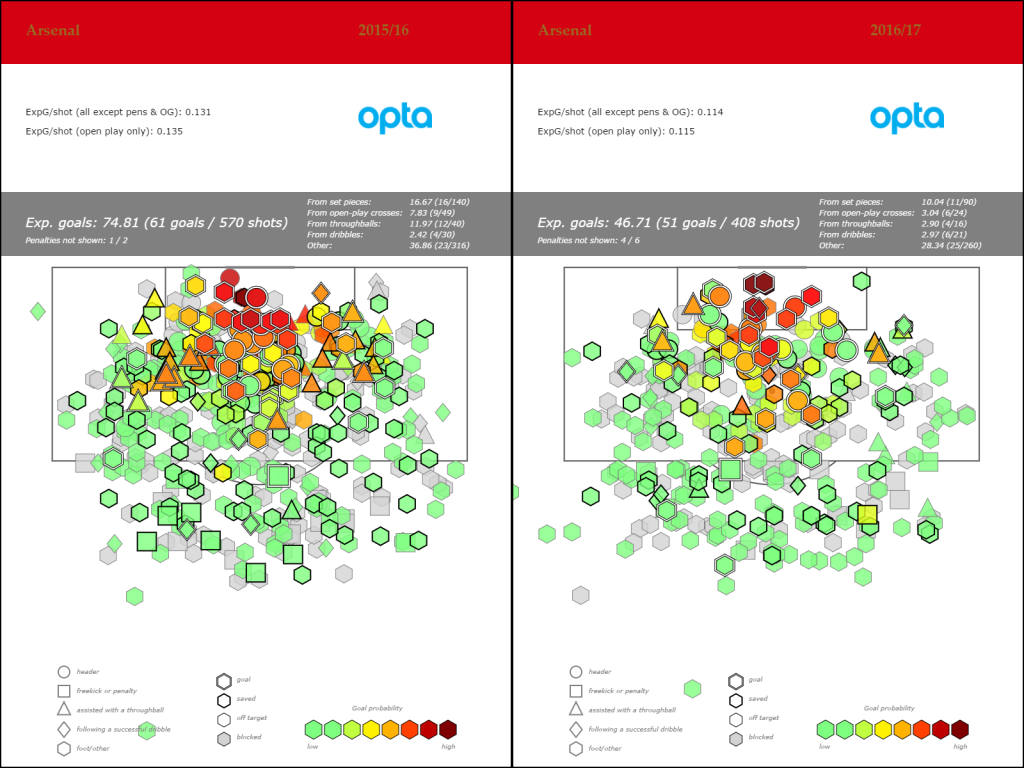

Let's start with the obvious ones, the expected goals numbers.

Attacking xG 15-16: 1.97

Attacking xG 16-17: 1.67

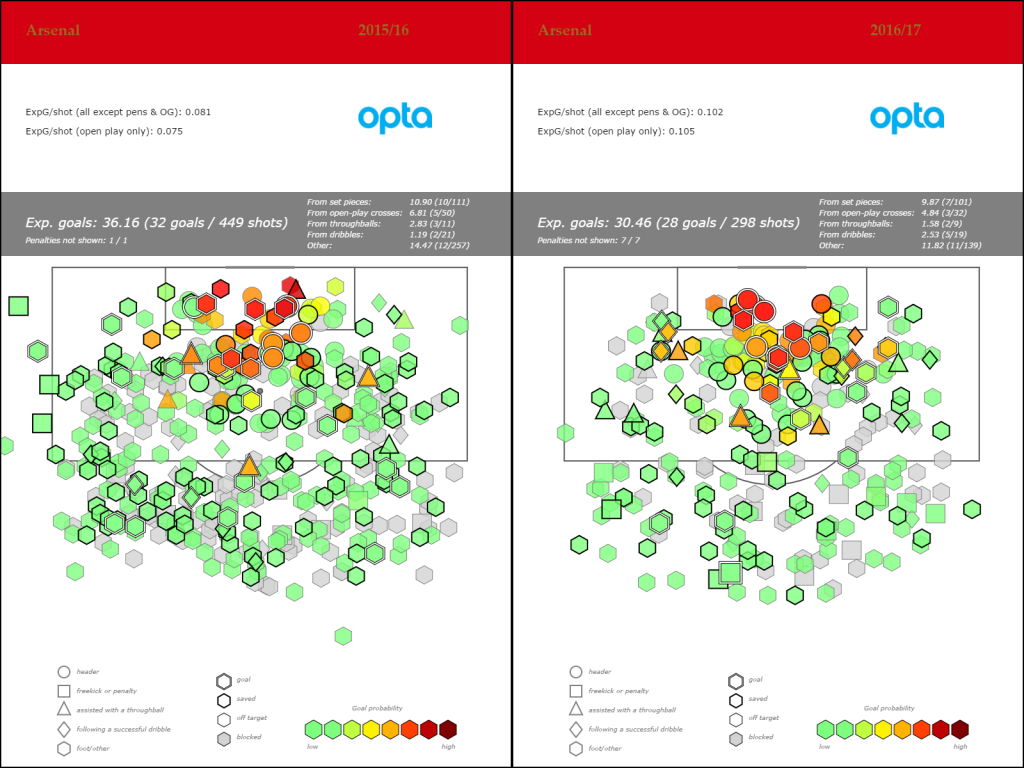

Defensive xG 15-16: .95

Defensive xG 16-17: 1.09

So the attack is generating .30 xG fewer per game, while the defense is allowing .14 xG more. Combine the two and you get -.44 in expected goal difference, which is a huge whack when it comes to performance in the league table.

Where's that coming from? Well shot generation is down a touch on the attacking side, 14.6 to 15, but open play shot quality has fallen from .135 to .115 per shot, so the drop in attacking output is almost all down to the quality of shots Arsenal are generating this season.

On the defensive side of the ball, Arsenal are actually giving up FEWER shots per game - 10.64 this season vs 11.82 last year. Again, the reason for the swing in xG Conceded is down to shot quality. In 15-16, Arsenal's average open play shot against was worth .075 xG. This season? .105.

Arsenal's opponents are generating forty percent better shots than they were last season! What happened to all the long range pot shots?

In previous seasons Arsenal have gamed xG by generating 40-50% more shots than their opponents while having a huge quality differential between the shots they take and the ones they concede. This year the quality difference is almost completely gone, which has dramatically affected their expected goals numbers at both ends of the pitch. This feels like a strategic change on the part of their opponents, but maybe I'm reading too much into it.

How Do You Fix It?

This is a massive question and one that I don't really know the answer to. Are Arsenal defending badly? Have teams solved their defense, and because of that know how to create better chances against them?

Arsenal's attack is probably the best from a personnel perspective that it has been in ages, and yet that isn't exactly firing on all cylinders. Would Cazorla's presence magically heal all wounds? He only played 15 90's last year and the Gunners were much better then, so I'm not sure his absence again this year has enough explanatory power.

Average shot quality in attack is still better than the 14-15 season, but this has always been Wenger's special sauce that he brings to teams. This year it's still good, but it's no longer among the elite, and it needs to be for them to have a shot at winning the league. This year, it's just barely good enough to give them a shot at finishing 4th. This is also true because despite generating plenty of set piece chances, Arsenal are dead average in number of goals scored from them at 9.

Most worrying has to be the change in the defensive numbers. Arsenal tend to play a more passive style of defense than most of the top teams, trading shot suppression for forcing the opposition to take worse shots. However, this year they are giving up far higher xG shots, but doing it at nearly the same rate as before and basically at league average numbers. That's not gaming xG, that's just losing more games.

The question of why this is happening has lots of moving parts that seem to add up to a big problem. Monreal is finally showing a bit of age, and is no longer the elite defender he once was. though talented, Mustafi has had some issues bedding into the Premier League. Gabriel perhaps isn't as good as Arsenal thought when they bought him, and he's been forced to play right back when Bellerin is out.

Meanwhile in midfield, the aforementioned Cazorla may never be fully fit again. It's like Defensive Midfielder Groundhog Day Part 2, except instead of starring Mikel Arteta and his hair, we now have a different diminutive Spaniard playing the lead. Welsh hero Aaron Ramsey has played about the same amount as Santi, leaving Wenger to choose the so-called Dumb and Dumber axis of Coquelin-Xhaka as a double pivot, while occasionally adding El Neny, Oxlade-Chamberlain, or Alex Iwobi into the mix.

Last year's Arsenal looked like the best team in the league in the numbers, and a club that was close to taking the next steps in regularly competing for league titles instead of fourth place. This year's Arsenal looks almost exactly like their league position - likely to miss out on the Champions League for the first time in ages.

At least we know who to complain about all of this to. Unlike almost every other club in the Premier League, Arsene Wenger has full control at Arsenal. The question is whether he understands what the causes of the problems are, and whether he's adaptable enough at age 67 to rebuild this team for future title runs.

Despite a generation of good years together, Arsenal fans no longer seem convinced he's capable of anything other than 4th place trophies and Champions League knockout rounds, but they've certainly started yearning for something different.

Men on Posts and Starting Fires

I mentioned on Twitter recently that while I try to avoid disagreements when I am in a room with traditional football people, the one thing that is most likely to set off an argument is the topic of men on posts. Today I want to explain why that is the case, while covering a variety of other topics along the way.

Men on Posts

I swear to you, this topic comes up almost every week on highlight programs and game commentary. It is perhaps a bit less prevalent than discussion about the failings of zonal marking here in England, but it's an old favourite for the back-in-my-day commentator crowd. In 99.99% of the cases, it is also nothing but dead air and might as well be replaced with any other cliche that also gets spouted by the same commentator crowd. (We need better, smarter commentators, but that was a topic for a different day.)

My perspective on men on posts is that I almost never use them for defensive set pieces. There are a lot of reasons for this, but the basic principle is that I prefer active defending to passive and this takes one or two players completely out of the play where their only job is to act as last resorts. Now this isn't to say that I would never put men on posts. There are specific teams and situations where they are beneficial, but those are fairly unusual.

However, my preference for set piece defense isn't usually what starts the argument. Once the subject is broached, the conversation usually goes like this.

Me: "How do you feel about men on posts when defending set pieces?"

Traditionalist: "Oh, I would always have a man on [near¦far] post and sometimes a man on the other one."

Me: "Why?"

Trad: "Because [reasons]."

Me: "Okay, but how do you know?"

And this is where things invariably get awkward because usually they "know" because someone taught them this was the correct way to do things. Or possibly some anecdotally negative experience like, "we didn't have men on posts in this game, and the opposition scored a goal in the corner," changed previous behavior and now they protect against that scenario.

The problem here for someone like me is that when analysing most topics in football, I start back over at base principles. How do I know something? Well, I studied it. I typically take a large amount of qualitative and/or quantitative data, break it down, and then look at the outcomes to see what's there. Then I ask follow-up questions and pick at the results some more until I am comfortable I understand what I'm seeing.

This doesn't mean I am right. It's not about being right. It's about being knowledgeable in an area that is important*. And it means I have a foundation upon which to have conversations. Conversations and arguments tend to illuminate what you do and do not know, and highlight areas for further investigation. This is important, especially in football which, if we're being totally honest, is a game that we really don't understand very well right now. This includes most of the ranks of professional coaches around the world.

*important to the performance of your football team, at least. In the greater scheme of crazy world events, understanding set piece defending matters not a nip.

It also doesn't invalidate knowledge learned from years of working on the pitch. It just means that if you believe a thing to be true, you need to explain how you came to those conclusions, and the reasons need to hold up to scrutiny. If they do, great. If not, let's study the issue and see if the accepted wisdom the you believe to be true is correct.

So yeah, when you ask questions about how someone "knows" a thing, and maybe question the validity of that knowledge, you can cause problems. But the fact of the matter is, we should be doing this constantly inside of clubs because it leads to valuable research that can change behavior and develops more effective styles of play.

A goal in the Premier League is worth something like £2M. How many of those do we leave on the table because someone's knowledge is outdated or just plain wrong? (For what it's worth, on defensive corners, my players have shit to do instead of loafing around, leaning against goal posts. We save that sort of behavior for useless analysts, as it's the footballing equivalent of mooning the queen, donchaknow?)

A Good Question?

Someone noted over the weekend that Manchester City seem to prefer outswinging corners these days to inswingers. This is notable for two reasons.

First, a few years ago under Roberto Mancini we were told that City started using only inswinging corners because someone in the team had done a study and found that inswingers were more effective at generating goals.

Second, this switch to outswingers seems a direct contradiction to research previously done by this exact same team.

Odd, no?

James Yorke started poking around the data a little bit, as we tried to figure out what data they looked at to come to whatever conclusion it was that changed their behaviour. This lead back to a far more important problem that is often overlooked:

What question were they trying to answer?

It certainly doesn't seem to be "which delivery is more likely to score goals?" since that either leaned toward inswingers or was inconclusive, depending one what data was used.

However, what James did find was that outswingers were far more likely to be completed to a teammate. So if they were trying to answer the question of "which delivery is more likely to let us keep possession?" then outswingers would make a lot of sense. Given this is a Guardiola team, maybe that's what he wanted to know, especially since he is typically far more concerned about defensive shape when attacking than corner production.

Is that a very valuable question to bother answering is another issue entirely. Given elite corner execution can produce expected values per corner of .06 to .08, while average corner values are .025 and average possession values for most teams are in a similar or even lower range, I'm not so sure.

This is where the difference in counting and percentage stats comes into play versus stats that attach value (like the xGChain passing networks from StatsBomb Services). As football analytics matures, it moves more and more toward the value end of the spectrum, since that uncovers behaviour and strategies we really care about. Failing to incorporate these elements into team research can result in suggestions that actually makes team performance worse.

I'm not sure this is what happened at City - as I said, we're guessing at literally everything while we wonder why they are doing what they do. It's just a concept to keep in mind when generating research projects and then applying them to team behaviour in the future.

English Coaching and Commentators

Circling back to the commentators we hear on Sky, BT, and BBC every week, it frustrates me that the people talking about the game now were generally players that grew up in and played a style that has been completely refuted by the modern game.

The traditional English style of play Does. Not. Win.

If it did, we'd see far more English managers present in the Premier League, and dotted around Europe's elite. What we actually see is a complete dearth of English managerial talent throughout the ranks of the football league. The Premier League gives zero fucks about this, but it is worrying to the FA and generally to the lower tiers of the football league as well.

I've asked questions about how coaches in England are supposed to learn more successful styles of play, and the only real answer seems to be to beg, borrow, and steal internships either at teams with successful foreign managers (extremely difficult to do, even with elite contacts), or learn a language and do your coaching education abroad. Good luck with that in a post-Brexit environment!

This circles back to FA coaching courses, which have been revamped (again) in the last year. I did the class days for England level 2 badges almost exactly a year ago, and while I generally liked the process they used to teach you how to think about coaching, I thought they were also lacking in certain areas. The section on pressing was largely ineffective and dismissive, where the instructors were telling us it was fad-ish and existed before. Technically this was true, BUT

- That ignores the fact that the current iterations of pressing come in many varieties and are substantially different than what you saw from the 70's through the 90's

- Pressing variations really matter for evaluating top level tactics and play, which means they really matter for top level coaching

- The instructors, who were otherwise quite good, displayed no real understand of this particular topic. Or really of shot locations and effectiveness. Which, if we're trying to train and develop better coaches and in turn better players, is probably a big deal.

Maybe this type of subject material doesn't matter at level 2, and I was expecting too much, or maybe English coaching education is still struggling dramatically to overcome decades of ineptitude to catch up with modern times. I honestly don't know.

Which finally leads me back to the current crop of commentators. Aside from Carragher and Neville, who clearly put a lot of research and work into their craft, the commentators currently discussing football on television generally don't understand modern tactics. How could they, when the tactics they were brought up playing were bad, and the coaching education failed to correct for that?

Nor do they have an analytical mindset, which would help to educate viewers on the reality of the game versus the perception. They commentate on games in 2017, but were almost exclusively trained in England, and brought up playing a style that almost doesn't exist any more at the top levels of play.

So what are they there for? The occasional interesting anecdote about mentality and what players feel like before a big game? To provide a constant stream of footballing cliches that provide no insight and are rarely relevant to the moment at hand?

We get nothing of interest from so many talking heads on television. No funny anecdotes about current players or managers. No tactical insight. No statistical insight. No points about technique and detail about what a player could or should have done better.

Half of the matches I and many other viewers watch each week have foreign commentators. I almost never feel worse off because of it. And THAT is a take away that should shake everyone involved in the production side of football, right up to the top levels of Sky and BT Sport.

Changing How the World Thinks About Set Pieces

4 Coaching Hacks to Develop Better Players

One of the things I think a lot about is player development. Part of this is because my kids are right at the beginnings of their football journey (and my son especially, is football mad), and part of it is because I think it's an exceptionally important topic to understand in building a professional football team.

The dichotomy of this is fascinating. When out with my kids, I literally see the genesis of their skill set starting from nothing. When working professionally, I review players who are many zeroes away from the Top 1% in how good they are compared to the rest of the world.

Today I am going to outline coaching hacks I believe are huge keys to developing better players. Some of these are appropriate to the very young, and others need to wait until you start imprinting tactical knowledge on players. I think some of these are fairly well understood in other countries, but I rarely see the whole package together, nor have I seen it explained at a level I was happy with.

Some caveats before we get started:

- These are not validated research on my part. Much of my work is on statistics, and I only write about things I have researched well enough to be fairly certain are correct. This ain't that. Where there is validated research I am aware of, I will link to it. However, I will freely state these are my learned opinions on what is better and why.

- Most of the material in this chapter is not unique or original to me. Unfortunately I don't know where it started, and so can't appropriately credit it either. My apologies.

- Plenty of it might not even be new to you. If so, you are likely already doing a great job at developing players.

- Finally, this isn't comprehensive. While I think dribbling skills and first touch are incredibly important to teach players, I also think those are generally well emphasized in good programs.

Balance

What happens when you take a five-year-old out to the park and have them lift up their foot to trap a ball?

They fall over.

Then as they progress to being able to trap a ball, we start asking them to strike it.

When they try to strike it hard, they fall over some more.

Everything we do in football is based on balance.

Juggling?

Balance.

Striking a dead ball?

Balance.

Dribbling?

Balance.

First touch?

More balance.

Running? Cutting? Jumping?

Balance.

This particular element of skill and strength is woven through every single motion in the sport, and might be the one overarching thing that ties it all together.

I played five different sports when I was a kid in the U.S. How many of those explicitly taught me balance by itself?

Zero.

It wasn't until I started learning MMA late in my 20's that I learned balance could be taught, and not as part of doing activities inside of a sport.

Once I learned how to balance myself and apply the strength that came along with it, I suddenly became better at every sport I did.

Funny how that works.

Now some of you might suggest that the current methodology is fine.

Learning through doing is a tried and true methodology, and in many cases it just works.

I disagree.

What happens if you teach children balance first?

The short answer is that every single thing in the game of football becomes easier for them to accomplish. The long answer is that you produce better football players, because the ones you are now working with are more able to focus on explicit techniques and adjustments without the constant fear of falling over.

How do you teach balance?

This is one area where a tradition of thousands of years has probably got it right: kung fu. There are legions of internet resources on this not to mention books and videos.

In the martial arts I learned, we worked through stance progression on both feet. The progressions are crucial because that's where you build dynamic balance between the static movements. When initially learning the technique yourself in order to be able to teach it, it's probably useful to get together with a martial arts expert to learn properly, as much of this is fairly subtle.

But it's boring!

It is, a little. However, you can get kids doing these on their own with the right video/email nudge to the parents, and it literally only takes about 15 seconds per stance plus a slow transition between them to start to see the results. If you have attentive kids (do it post-warmup, after they have been running around a bit), it can be done in about 3 minutes.

Black belts in various martial arts can literally spend hours working through stances and body mastery, so the time progression here goes as far as you want it to. (But preferably at home and not during your incredibly valuable training time.)

Looking to create a little extra buy-in? Conveniently stance mastery is a key component of both jedi and ninja training. Let your kids know.

Here's another reason why I thing this topic is hugely important: Balance is absolutely crucial for smaller players.

A major problem we have in player development is that smaller players are constantly weeded out. Not for lack of skill - in fact, often they have better technical skills than their bigger counterparts - but generally for a lack of strength and "ability to compete."

Now picture the small players who are in professional football. Almost all of them have amazing balance. You often hear them described as having a "low center of gravity", which makes them difficult to knock off the ball, easier for them to tackle big players, and generally just annoying as hell to play against.

This is really just another way of saying they are short with great balance. Balance, and the strength that comes with it, is the key when it comes to enabling smaller players to compete with bigger ones. If you don't introduce this to your youngsters and give them a methodology to improve, you are failing them.

At the Pro Level

I was lucky enough to present at Science and Football this year with Grant Downie, Head of Performance at the Manchester City Academy. Grant is tremendously thoughtful, and the attention to detail he described City as paying to their academy was jaw-dropping. He told us that Manchester City have playgrounds for their academy kids, and those playgrounds intentionally feature plenty of balance-related elements. He also mentioned that their first team regularly does light wrestling, to learn to use balance when in contact with another person, which is especially useful when attacking and defending set pieces.

I was talking about this with Jim Pallotta, owner of Roma, in 2015 and he said they were doing balance tests in preseason and had a backup goalkeeper who kept falling over when asked to stand on one leg. Everyone in the room was shocked that something like this could still happen at the pro level. You know for a fact that if it is happening at Roma, it's probably happening everywhere.

Here's a blurry photo of Berndt Leno catching balls while kneeling on a balance ball as part of a warmup that I absolutely love.

Balance and core strength is hugely important for GKs because they constantly find themselves in odd positions that they have to make explosive motions out of in order to make saves. Better balance also helps you become faster at making these dynamic motions, even when something has happened to mess up your initial positioning or footwork.

Also check out some of the sand pit work (around 1:35) in this video from the Ajax academy for some funky, creative ways to continue training balance at elite levels. Forwards are constantly getting battered by other players, and being able to continue executing while withstanding that sort of assault makes a huge difference in end product.

Two-Footedness

This is probably the most obvious hack on my list, but it happens far too infrequently. I think one of the major reasons is that is has to be trained young to take full effect, and professional academies rarely have access to children at this age. Because of that, the responsibility falls to parents and community coaches.

Having two good feet completely changes how a player can approach the game. It's hard to quantify, but it opens up the other half of their body, which in turn makes vastly more options available with every touch of the ball. More good options = more opportunity to succeed and maximizes good decision making ability.

Think of it from the perspective of the defender. If I know a player only has one useful foot, I can always key on that when trying to defend. It makes my life easier. On the other hand, if a player is running at me or likely to shoot, and he or she can use either foot with equal alacrity, my job is infinitely harder.

Having a second good foot also makes life easier for a player's teammates, since they suddenly have a much larger margin of error when passing to that player. I've run into two major difficulties in my own training of U7s and U8s in this area.

- You have to make the kids aware of the need to use both feet. It's also good to attach it to a player they really like and talk about how hard they worked to make sure both feet were good. (Santi Cazorla is my son's example.)

- You have to reinforce this need constantly.

Kids want to succeed.

As their dominant foot starts to get good, working with their weak foot feels like constant failure. Thus you have to talk about it in the same way as any other skill, but you have to mention it frequently, regularly, for years.

"Use the other foot! Now try it with your left! Pass it to the right, control with a touch, then shift it to your left to pass it back. Okay, now control with your left and shift to your right for the pass."

It is a long process, but... If you stick with it, you see your kids start to gain comfort. My son, who is an able U8 player but possibly nothing special, passes and shoots with both feet regularly during his games. He doesn't think about it either.

He's probably scored five goals over the last two years with his weak foot (his left), which never ceases to make me smile. We talk about why we train both feet fairly hard so that he understands it. One of the easiest paths to understanding was showing him how he could cut central much easier for better shots if he used his left foot as well as his right.

If you want to develop better footballers, you must impart the knowledge that this is important to your players, and find subtle, constant ways to bring it into training.

At the Pro Level

I was helping Flemming Pedersen (now technical director at Nordsjaelland) set up a Brentford B session last year and watching some players warm up. One guy, who was fairly well regarded, was only warming up with his right foot. I noticed and jokingly asked how many feet he had. "Two." At that age, if he's only warming up with one, the hope that a player can use both feet equally is probably dead. Start early. Reinforce it regularly. Constantly work it into training as a nudge.

Scanning

Scanning is the act of constantly looking beside and behind oneself on a football pitch. (Some coaches call this "shoulder checking", but it's a more comprehensive activity than that.)

To me, scanning is the single biggest skill that separates average from elite players.

It has also been heavily validated, so before we go too far, check out this presentation + paper from the Sloan conference back in 2013.

"The results show a clear positive relationship between visual exploratory behaviors (scanning) that are initiated before receiving the ball and performance with the ball. The best players explore more frequently than others and there is a positive relationship between exploratory behavior frequency and pass completion. The impact of exploratory behaviors is the largest for midfielders performing forward passes."

The first place I ever saw this highlighted was a video from AllasFCB about Xavi. I still get chills thinking about it, because in my mind it was truly this HOLY SHIT moment of new knowledge.

(See also: football epiphany.)

In the video, Allas shows just how often Xavi is looking around the pitch, without the ball. It is an insane number of times, like every other second for an entire game.

However, this activity is what powers Xavi's game. He had an almost otherworldly ability to see the pitch, find open men, find his own space, escape pressure, and complete impossible passes most players would never even see.

He could see these things because he was constantly looking around. When I first watched this video, my heart stopped.

I had been watching football for 15 years at that point, why had I never seen this?

It literally changes how you can see and play the game. One of my all-time favorite examples of this came during a Bayern Munich match from last season. Watch Xabi's head look to his left just as the right back receives the ball.

As part of his scanning, he spots Costa in space with only a fullback near him. It's an amazing pass, but that pass is created because his scanning made it possible.

Here's the thing - scanning is important everywhere on the pitch. Forwards need it to see who is around them, whether they can turn, where the space is, where they should run, etc. Midfielders need it for absolutely everything, since they are surrounded by opponents at almost all times.

Defenders need it to know not only where their nearest opponent is, but where their helping teammates are, where additional runners may be, and as you see above, where their potential passing outlets are once they recover the ball.

You want to teach your players to play one step ahead of the opponent?

Teach them to scan.

How best to train scanning?

I don't know.

This was high on my list of things I wanted to learn when visiting elite academies, but I never got to make that trip. I have some ideas on how to go about it, but have done zero work on best practice.

I asked a high level English coach how he would go about training it once and got the following answer:

"I learned to look around when they threw me into training with the big boys, because if I didn't, they'd kick holes in me. Teaches you right quick, that does."

We may have some issues with pedagogy in this country. Please leave links in the comments if you have information on how to train this at different levels, and I'll review them and gradually move the best of them up here as recommendations.

Cover Shadows

In my head, this is the inverse of scanning for the defensive side of the ball. It requires scanning to do well, but understanding cover shadows will help players dramatically limit passing options for opponents. Think of the ball as a light source. Bodies of defenders are solid, and they create shadows behind themselves.

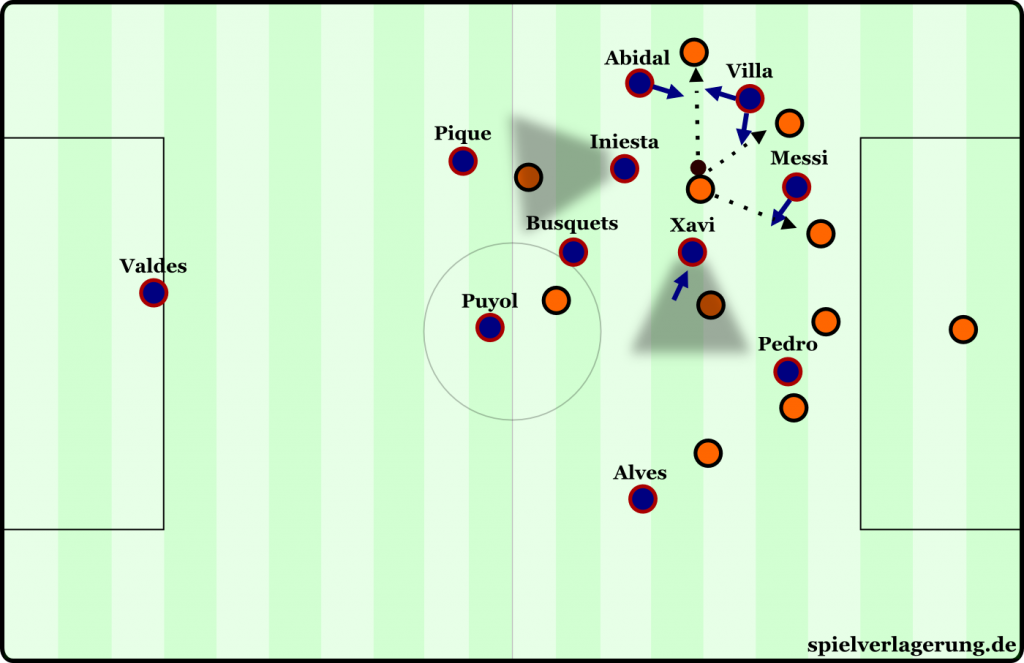

Here's an image from Rene Maric that clearly illustrates the concept, and the grey shaded area are covering shadows for Iniesta and Xavi.

Why does this matter? Because it is a key to defending, particularly to pressing defense. It allows a player to not only press the ball, but also to limit a passing option at the same time. And it is a concept your attackers need to understand in order to work through a press from their opponents. Unclear? Check this out. Watch Aubameyang's sequence of presses here and in particular, look at how he cuts off a passing angle with a curved run each time.

Then notice the creep (or sprint) on the other Dortmund defenders as they move forward and further cut off lanes like some sort of pressing python, strangling possession.

The result is a long pass into the distance, and likely Dortmund regaining the ball. I also like the explanations from Spielverlagerung about Atletico's press, which has a different flavour than Tuchel's, but the underlying concepts are similar.

That piece is crazy long, but example 1 is enough to get a sense of what I mean.

How do you train it?

It goes hand in hand with scanning and pressing. How do you train elite level pressing? What are the sessions?

What does the knowledge progression look like?

Sadly, I once again don't know.

As I mentioned in my How Coaches Learn article, coaching knowledge is very much an apprenticeship, and I have not been able to learn how to teach this to players from experts yet. That doesn't change the importance of the skill with regard to player development. It just means my ability to convey further knowledge to you is currently limited. Think of the following things slotting into place for your players:

- Scan the whole pitch in attack.

- Scan the whole pitch in defense.

- Work covering shadows aggressively.

- Form Voltron.

That's almost how it works. First you make one phase of the game far easier for yourself. Then you make the next major phase easier as well, and you make your transitions better in the process. Finally, you make attacks for the opponent far more difficult. The result should be a massive improvement on a possession by possession basis.

Wrap-up

To me, the four elements discussed above are the fundamental building blocks for developing better, smarter players. I don't know how to train the last two well, because they are specialized knowledge that I have yet to unlock, but I am absolutely certain of their value to modern footballers. Thanks for listening.

--Ted Knutson @mixedknuts

Post Script

This is another chapter in a book I have gradually been developing over the last year. It touches on all sorts of topics, but the main purpose is to explain how I view the game of football and why I think the way that I do.

I don't approach the game from the standpoint of someone who played - that wasn't an avenue that was available to me where I grew up.

Instead I approach the game from a standpoint of examining what matters, how do we prove that, and how do we apply these lessons to teams on the pitch? Currently finished chapters are linked below (and are all free), so have a poke around if you are interested in more.

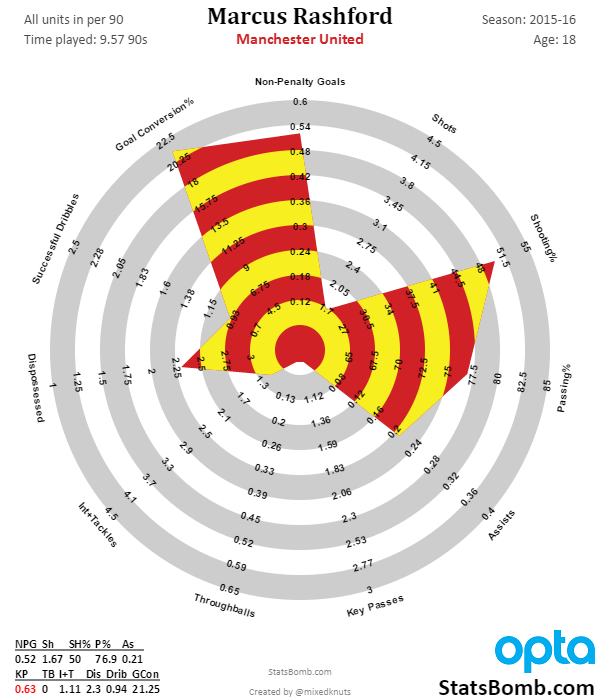

Explaining and Training Shot Quality The Future of Football How Do Coaches Learn? The Death of Traditional Scouting New Tech Marcus Rashford and Young Player Development

NEW TECH and A Little Story About Neymar, Andros, and Eden Hazard

Football Analytics has a learning curve. That's great, because learning is a fun, though occasionally painful process. This summer I did a review of my past work, and there's some cool stuff in there from the early days along with some really boneheaded mistakes. It doesn't matter how smart you are - your work is not going to be perfect when it comes to something new. The trick is simply to get over it and do better next time.

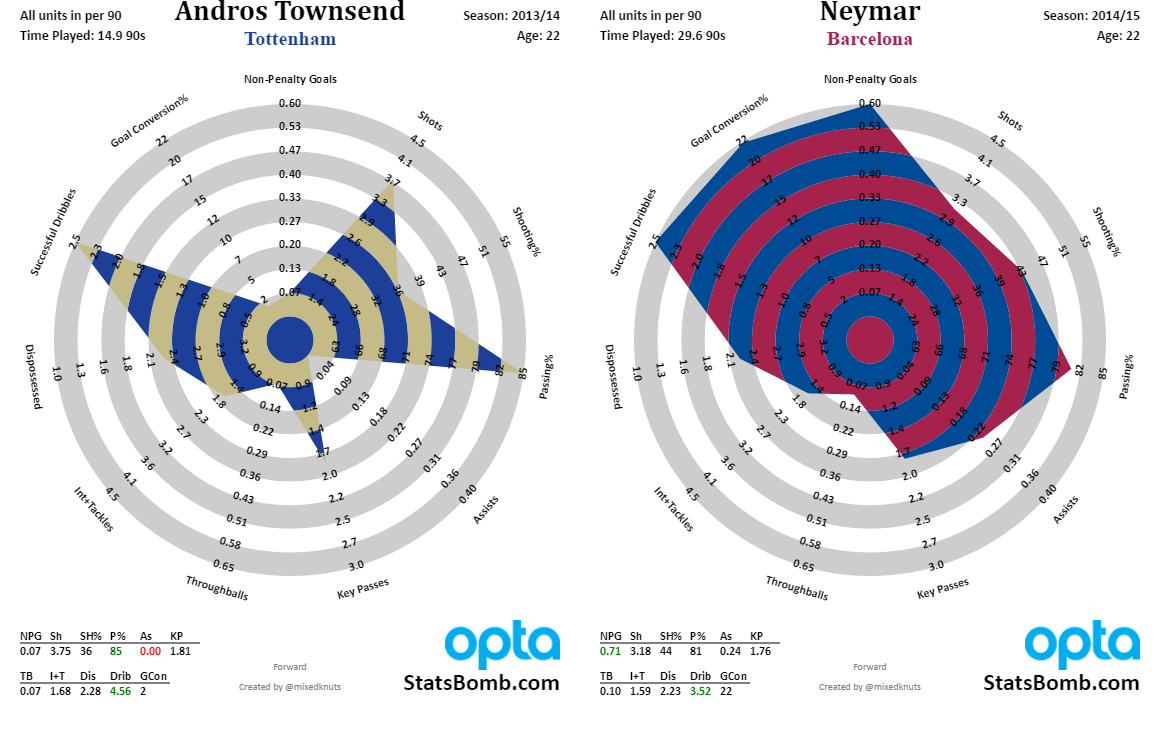

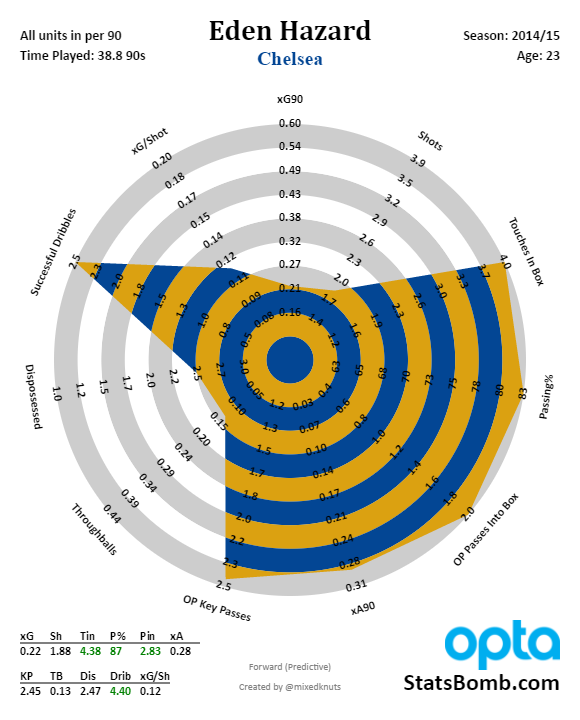

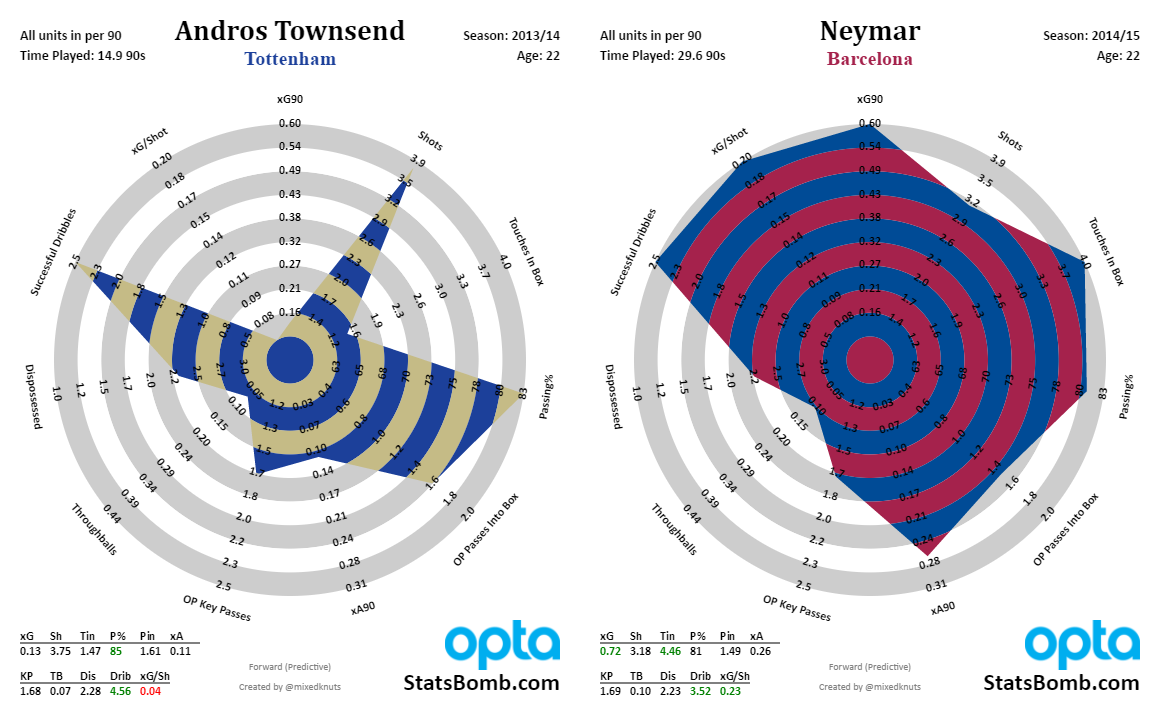

Today, I wanted to talk a little more about what I learned regarding player evaluation while going from zero knowledge in 2013 to running worldwide recruitment for two clubs in 2015. As part of that, I'll introduce the new attacker radars in print for the first time, and I'll talk about three of the most famous players in the world: Neymar, Eden Hazard, and... Andros Townsend?!?

Learning Curves

One of the first things you do when looking at a new data set is immediately boil it down to the important stuff and focus on that:

What is correlated with [important stuff?]

What causes [important stuff] to happen?

In football, we care about goals. In fact, for some pundits, that's all they care about. The only number that matters is the score.

Imagine a classroom of ten-year olds talking through the data.

Alright children, today we are going to talk about football. Match of the Day and legendary England striker Alan Shearer said we care about goals more than anything else.

So the first thing we have to ask is, what causes goals?

"Shots, shots cause goals!"

Excellent, Timmy. You're too young to remember, but Alan scored an awful lot of goals back in the day.

Now if we take a step back and say we care about "scoring", which is actually a superset of goals, what else might we care about?

"Assists! Assists are passes that created a goal. They should count too."

Great. Now we have goals and assists. And let's find one more element to look at here - what do exciting players do a lot of when they attack?

"They uh... elbow people in the head?"

I know you like Diego Costa, David, but that wasn't quite what I was going for.

"They dribble?"

Outstanding Samantha. So lets see if shots, assists, and dribbling are a great start to finding players who score more goals.

End Scene

It's a bit forced, but this is literally what most people do when they start analysing football, which is great, because it's an excellent, logical process. There's one missing step in here going from assists to key passes, which is the functional equivalent of going from goals to shots, but that's it.

Want to find interesting attackers? Look at shots, key passes, and successful dribbles. Do this and good players start to magically show up at your doorstep.

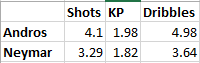

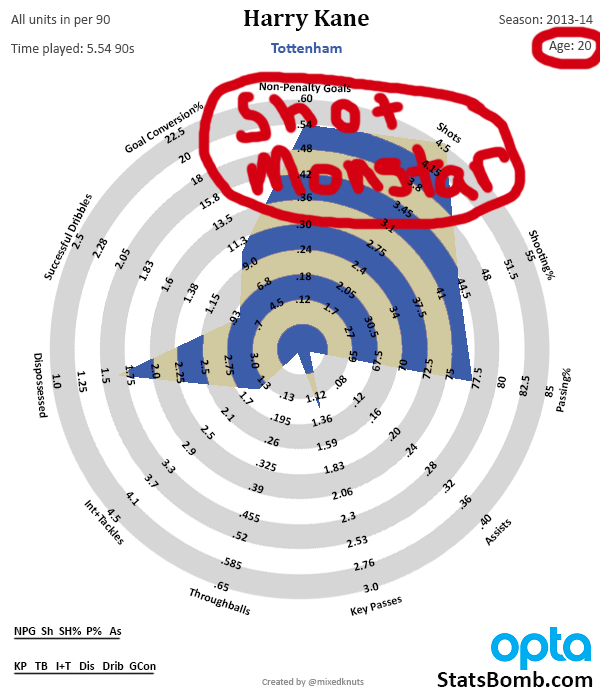

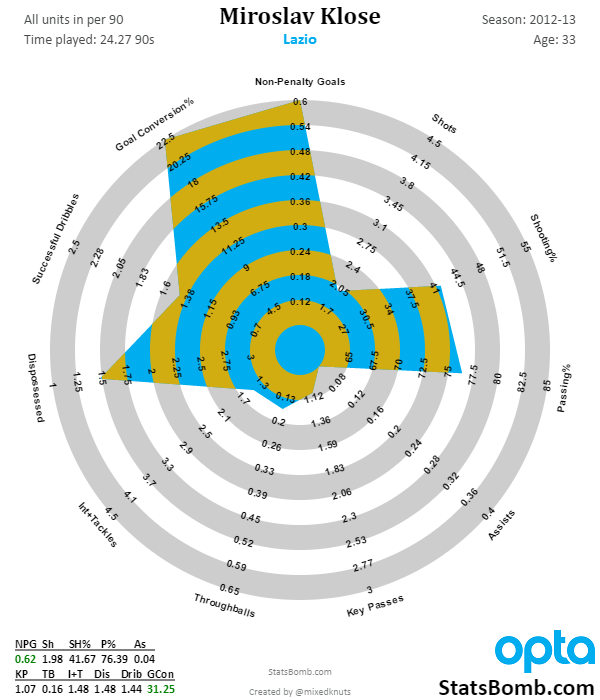

For instance, take the numbers for these two guys...

We've isolated what we care about in attackers, and these two young guys stick out like sore thumbs. They are similar ages, and even play for bigger clubs in good leagues, so there are no worries about league translation or anything like that. Indicators are that Andros might actually be a slightly better player than Neymar, but they are both very good for their age.

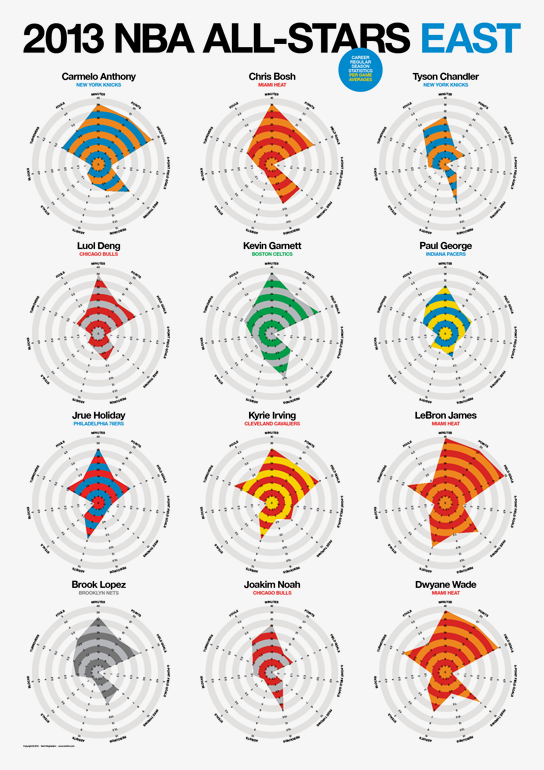

Plot them side by side on the original forward radars and you get this.

Given our earlier conclusions about certain stats driving scoring outcomes, this begs the question...

Looking at this objectively, there might be a flaw in our process. These two players have a lot of similarities in driver stats, but the thing we actually care about - scoring - is massively different. Were either of the players lucky/unlucky in their output? Is it a teammate problem? A coach problem? You can think of a million different possible reasons why scoring might be different, but guessing is unacceptable.

So we now go back to the drawing board to find more clarity. There are lots of ways to do this, but one of the simplest, most effective ways of going about it stems from one of the most important lessons you learn as a data scientist.

Always plot your data.

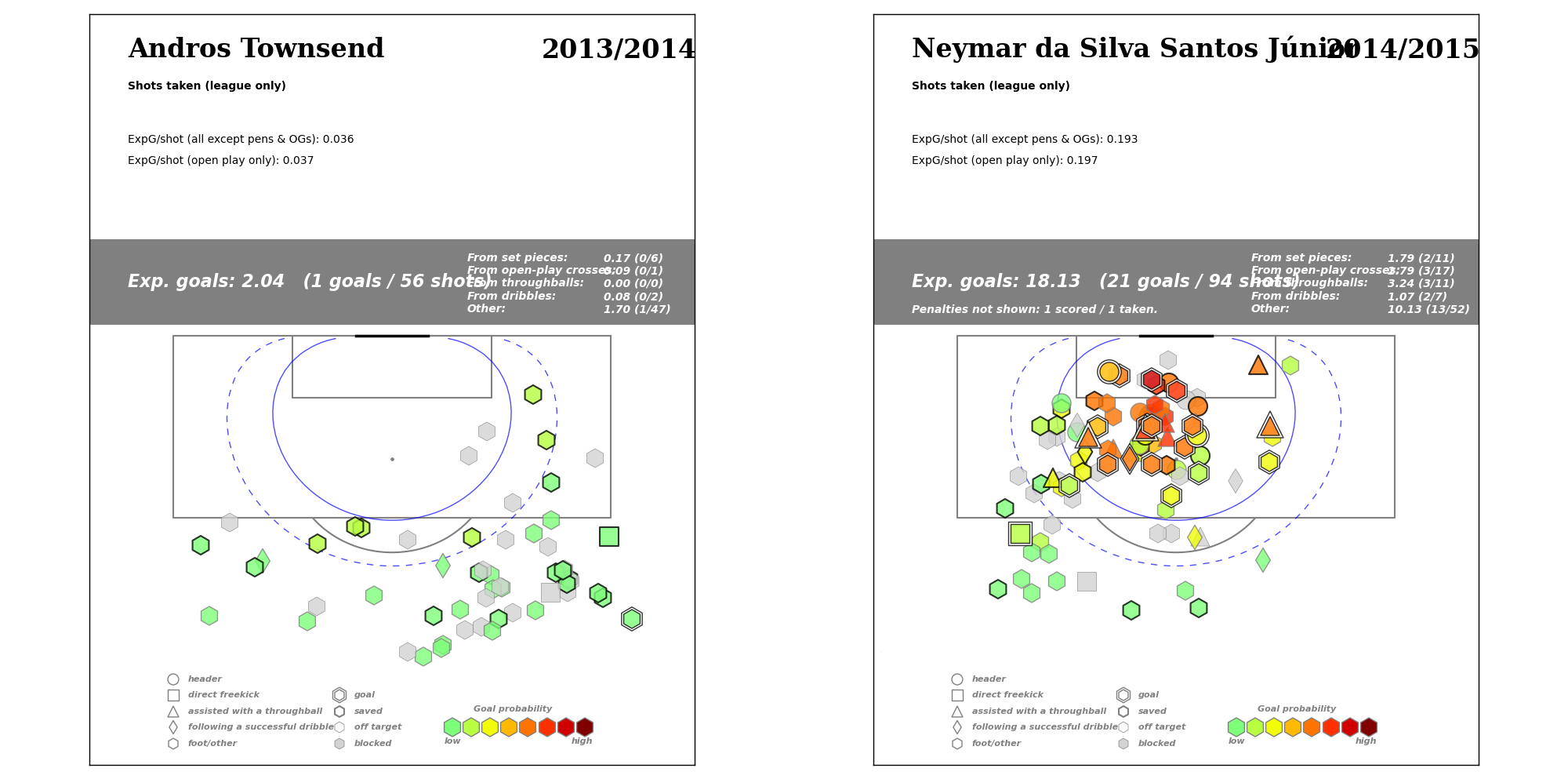

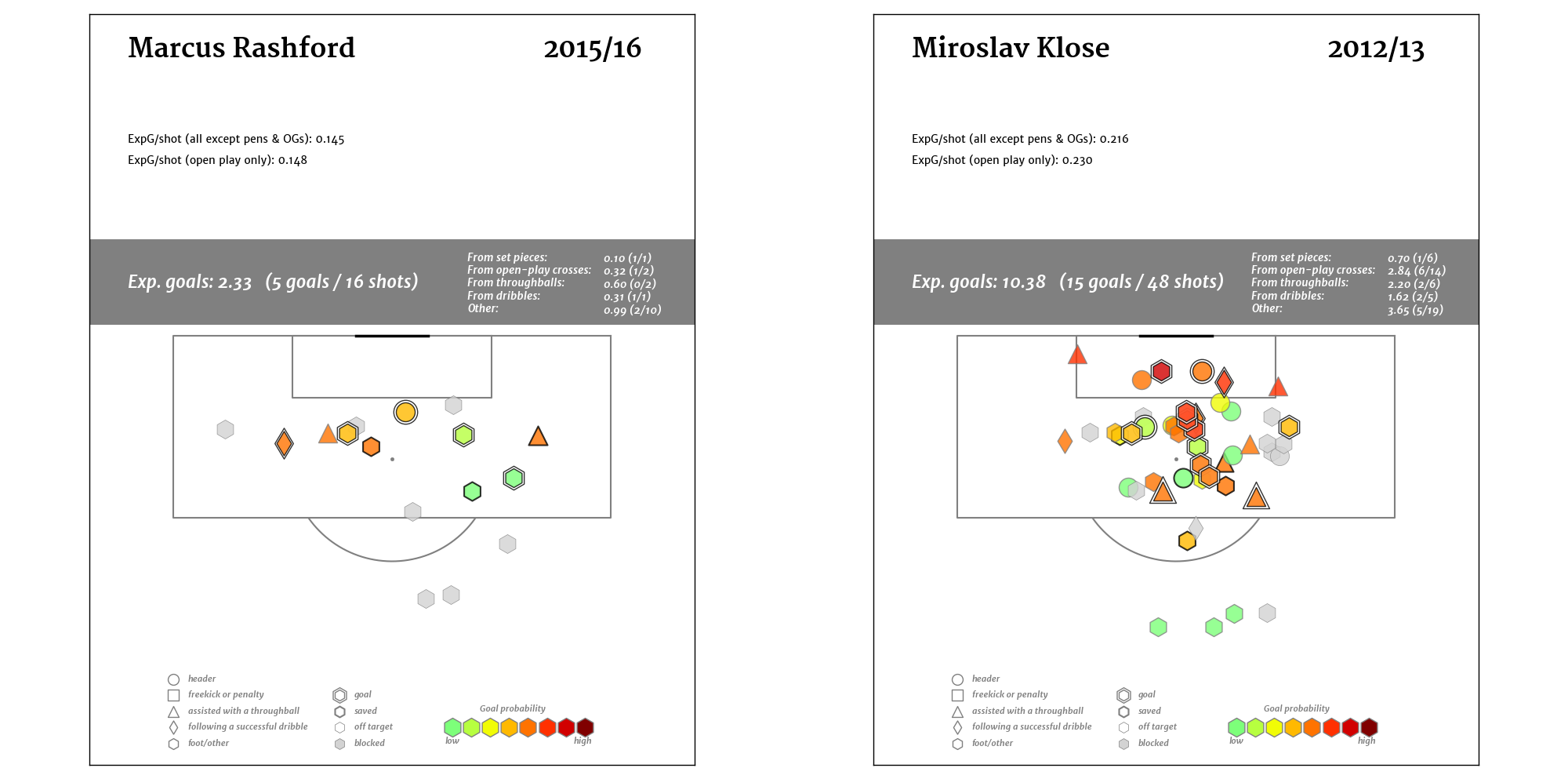

Here we take locational data for shots and add it to the MK Shot Map format... and you get this.

(click to embiggen. Made with Opta data)

Oh.

Oh my.

That's...

I mean...

It's as if someone put a force field around the danger zone shooting ring for Townsend, and he's not allowed to have the ball in that area. Meanwhile, almost every shot Neymar takes is from prime real estate.

The reason for potential problem we flagged up earlier immediately becomes clear.

So using numbers and visualizations, we have gone through a three-step advancement in the player evaluation process.

Step 1: These are numbers we care about. Let's look at those and see what happens.

Step 2: Visualizing them on the radar charts while normalizing them for the population shows that we might have a hole in our basic process. Was Townsend unlucky not to score from all those shots? How do we get more clarity on this?

Step 3: Visualizing the data on shot maps makes the problem crystal clear. Neymar takes great shots. Andros takes terrible shots. In fact, Neymar's expectation of scoring on an average shot is more than five times greater than Townsend's. This in turn has an absolutely massive impact on their probability of scoring a goal from any particular shot.

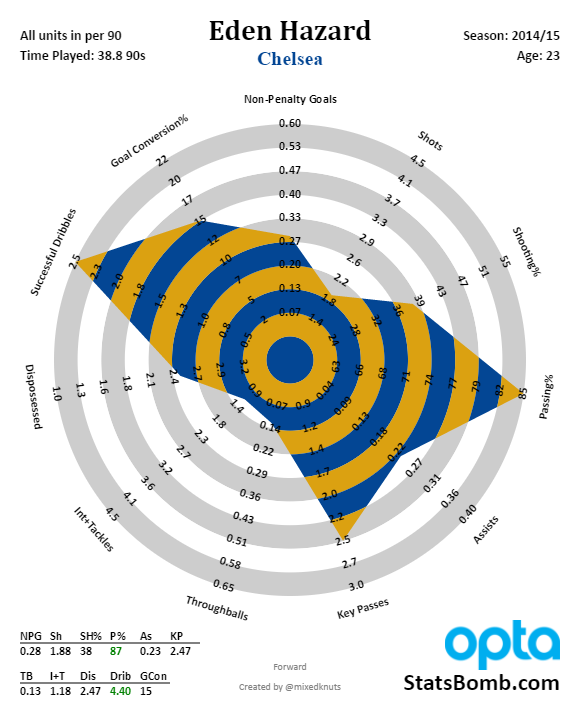

Other Holes in the Process - The Eden Hazard Problem

Obviously with attackers we care about scoring, but what about players we know from watching have a huge impact on the game, but for whatever reason don't show up very well in traditional scoring stats?

To put it another way, how do you find players like Eden Hazard? Hazard might have been the best attacker in the Premier League in 14-15, but his scoring stats weren't close to overwhelming.

What can we do to tease out more data and find elite players who don't always directly contribute to goals or assists?

For me, the answer was to take another step back in the process. We look at key passes and shots and they matter, but what about the ability to generate successful touches inside the box? And since football is fundamentally a passing game, what about players who are able to make successful passes into the penalty box, which might be one of the rarest skills in the game? So I created two new metrics:

- PINTO = Successful passes in TO the box

- TINDA = Successful touches inside 'DA box.

It turns out when you start to isolate players by this particular combination of skills, you get a useful additional perspective on players who contribute to scoring, both directly and indirectly.

Thus a new format of attacker radars was born.

I called the new template "predictive" because at this point in my head, I was thinking of the old template as "narrative." The new template took a step back from narrative stats about what happened (goals, assists, goal conversion, etc), and started to use a few of the advanced, more predictive measures we'd developed since I created the early versions.

The new format more clearly illustrates what a monstrously talented creative player Eden Hazard was that season compared to the population of attackers.

(Note: OP stands for 'Open Play' which I get asked constantly on Twitter)

Finally, circling back to our initial comparison, this is what those Townsend and Neymar seasons look like on the new template.

Conclusion

Learning how to use football data better is a process, but it's a worthwhile and rewarding one. The new radar format came about from continually asking questions on how to analyse the data better. Can we iterate and improve on old metrics?

The old format was good as a starting point, but the new format shows player value much more clearly. It also contains years of work and improved understanding about how both the data and the game operate.

It's also worth noting that even this "new" tech is 18 months old. If you are a club and interested in seeing some of the new stuff we've developed in the intervening months, drop me an email at mixedknuts@gmail.com.

The latest tech is both cool and extremely useful in helping your club make better decisions, both on the pitch and off.

--Ted Knutson

@mixedknuts

July Mailbag - Gotze and Nolito Analysis plus Discount Center Forward Shopping

Some football experiments do not work out. The Mario Gotze/Pep Guardiola experiment is definitely one of those failures. It reminds me a bit of the feedback from fans when Pep bought Cesc Fabregas and then tried to shoehorn him into the false 9 role at Barcelona. Fabregas actually did admirably in a completely new role for him, but no one is Lionel Messi, and that was a perception problem more than a performance one.

Gotze is probably at his best as a pressing 10 who can occasionally fill in as a creative wide forward when needed. What he is not is a center forward, and at this point it’s probably fair to say that trying to make him one has made Mario miserable, and given him perhaps the worst two seasons of his career.

I don’t think he was bad last season – 3 goals and 4 assists in about 1000 minutes is a solid return, and he’s still an outstanding passer and dribbler. On the other hand, everyone at Munich seems to want him to go, and he’s allegedly pissed off and being stubborn about leaving.

It’s clear to me he needs to get the fuck out of Dodge. My only concern is that he needs to go somewhere he wants to be, with a team and a head coach that will support him. Klopp might be the best option, but at a club level Liverpool is certainly a step down from mighty Bayern (don't @ me).

From the perspective of a buying club, you know he’ll be on big wages and has been a disappointment this move, so you’d negotiate aggressively for a lower fee while telling the player how much you want him. I think he’s a good buy if you can get the fee down to say £20-25M, provided he’s excited to come to your club. If he ends up at a port of last resort…

Probably £10 million, but it still depends on club. Arsenal could make a lot of £10M gambles and only wince a little when none of them pay off. A club like Burnley can only make maybe one before it really starts to create problems if they bust.

I was talking to another analyst recently, and we theorized that it might be impossible for Premier League clubs to get player deals with any "value" in them any more, strictly due to the fact that selling teams will hold out for much larger fees since they know everyone has money. Thus an objective value deal in real world terms becomes hard to find, but you can still find heavy "value" relative to the rest of the league, especially if you sell them to bigger PL teams down the road.

With that squad, I would probably not sign Nolito. People forget that money (in terms of fees and wages) is not the only scarce resource at a football club, so are minutes. I quite liked Nolito for the past couple of seasons at Celta, but City are O-L-D.

Aguero? 28. Bony? 27. Navas? 31 in November. Nasri? 29. Silva is 30. That’s just in attack and most of those guys have had injury issues in recent years. Kelechi, Sterling are young, KDB is peak, but as it’s composed right now, the majority of team minutes will come from players who are 28 or older. It’s tough to do that in the Premier League with CL and Cup commitments and succeed.

On the other hand, City just don’t care about the funds spent and if Pep wanted him, the price is low enough to just splash the cash and assume he’ll deal with any other issues. Nolito is a clever player and should end up as an outstanding super sub for the next couple of years, regardless of whether he’s good enough/young enough to spend a lot of time in a starting role.

I expect to see a staggering amount of money spent by the time City are done buying this summer. Pep’s worth it, but this would have been a lot easier if more forethought and planning had gone into squad composition in the previous 3 seasons.

Andre Gray was bought last season for a base of £6.25M (with good add-ons) and he’s probably PL quality. The new TV deal will inflate prices paid, but up until last summer, you could probably find players dotted around Europe who could play striker for you at £5-6M and expect reasonable success. Now that figure £8-10M, and there will be fewer undiscovered gems.

Recruitment is hard. Every team has similar needs and a lot of money now. This is why it pays to invest in being smarter about it instead of simply throwing more money at the problem and hoping you succeed.

This is quite difficult, and most clubs are naturally risk averse in this situation. If you don’t see the player play in a similar system to the one your club plays, the natural instinct is to assume they can’t do it, especially at the back. It’s a safe assumption, and I completely understand the choice, but it’s not always the best one.

Some clubs will break this assumption for special players or when their options are dwindling and they are forced to make sub-optimal choices. The point here - like I mentioned above - is that this is hard, and it actually makes sense to be cautious because if certain players fail tactically, the whole system can fly apart.

I started doing this work back in summer of 2013 with Manager Fingerprints because I wanted to start profiling managers in a similar way to what I was working on for players. Since then, the process and KPIs have been improved dramatically, to the point that we can identify tactical style, strengths, and weaknesses in the data for each manager/head coach and give some advice on whether they will succeed.

Manager failures are EXPENSIVE. Not only do you need to worry about paying out the rest of their contract, you also have to pay off all the staff that each new manager brings with them. Doing as much objective due diligence as possible before each hire just makes sense.

At the very least, this information highlights some very interesting interview questions you would want to ask every coach as part of your hiring process.

I asked a couple of follow-up questions to Bobby to give me more information on this one. He says we’re probably looking at a possession-based 4-2-3-1 with Gylfi playing behind the striker, so ideally you want someone with some pace, who can hold up the ball and pass reasonably well, and who won’t get destroyed by PL centerbacks. Tricky stuff, especially trying to fill two positions for only £25M, but we’ll see what we can come up with.

Two guys that I would have included, but whose price tags skyrocketed recently are Vincent Janssen (off to Spurs for 22M Euros) and Manolo Gabbiadini (West Ham allegedly in for him at £20M). Money still matters for at least part of the Premier League.

Most of the ones that I propose below are low risk type buys. There are others that are higher risk, but a) they are less known and b) your scouting department would have to be really happy with them before you make the leap.

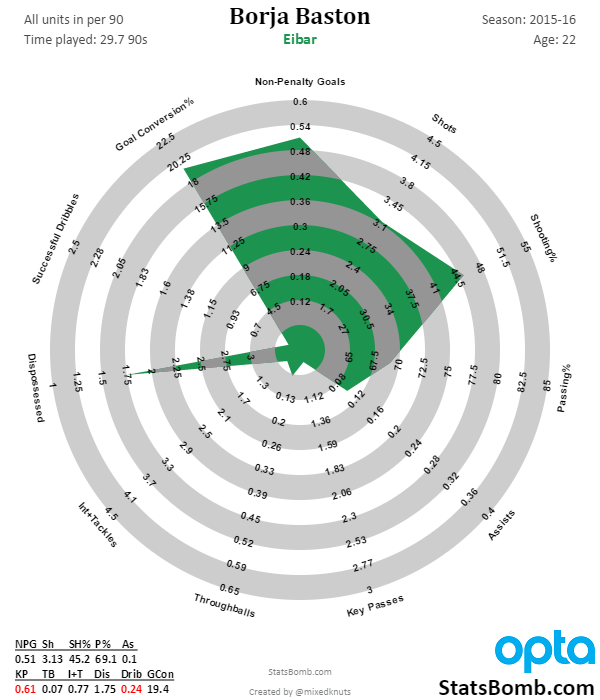

Option 1 – Borja Baston

Current Owner: Atletico Madrid

Age: 23

Estimated Price: £12-15M

I spotted him in Segunda last summer, but the price tag was north of 5M Euros, which was not a fee my previous employer was willing to pay, and he wanted to play in a top league anyway. He did that last season on loan at Eibar in La Liga, banging home goals exactly like he did a league below. La Liga is the toughest league in the world right now - if you score there, you are definitely talented.

Age is right, production is right, body style is right. I suspect the only real question is whether Atletico want to keep him in the fold for next season.

Option 2 – Sebastien Haller

Current Owner: Utrecht

Age: Just Turned 22

Estimated Price: £8-10M

A bit less heralded than Vincent Janssen, he played on a slower-paced team than AZ, but still put up impressive goal and assist numbers the last two seasons in the Eredivisie. Pace is solid for a big man, and I love his ability to pass around the box. He had two assists late in 14-15 that were jawdropping. The usual stats might not look amazing this year, but I have pretty strong reasons I can't explain for why I am still high on the player. His highlight reel is exceptional.

Option 3 – Andrej Kramaric

Current Owner: Leicester City

Age: 25

Estimated Price: £12M?

An elite scorer in Croatia, Leicester snapped him up for somewhere around £7.5M in January 2015. Kramaric did quite well at Hoffenheim on loan last season after struggling a bit at Leicester. I think they pulled the trigger on him too quickly though and…

What do you mean already Leicester SOLD him to Hoffenheim for a tiny profit on what they paid?

Goooooddammit.

NEXT!

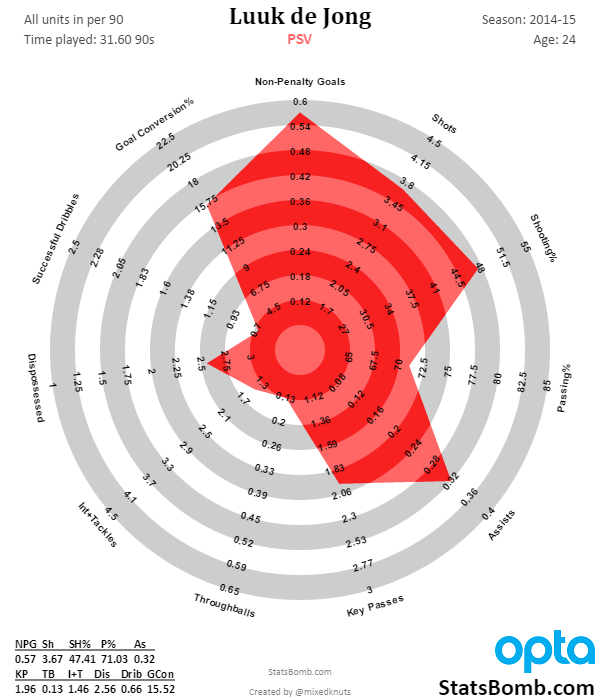

Option 3.1 - Luuk de Jong

Current Owner: PSV Eindhoven

Age: 25

Estimated Price: ???

“Didn’t he fail at Newcastle and Gladbach?”

Sort of… hear me out.

Newcastle have been highly dysfunctional behind the scenes for years. They seem to destroy good forwards on a yearly basis, meaning they either have huge flaws in their recruitment process OR the club itself has systemic issues. Seeing as how they have been relegated again this past season, I’m going to go with the theory that it’s more Newcastle and less Luuk.

Meanwhile he has been fucking great at PSV, winning back to back titles and making the knockout rounds of the Champions League. He’s averaged 23 goals and 9 assists the last two years and totally deserves another shot if you can negotiate a reasonable price for him.

Maybe he’s happy in Holland, but I think he’s good enough to play in a better league, on a stable, more supportive team.

Wissam Ben Yedder

Current Owner: Toulouse

Age: 25

Estimated Price: ?? Figuring out what Toulouse will sell anyone at is difficult and I have zero guidance on this aside from saying he only has 1 year left on his contract. Definitely less than £10M.

Ben Yedder was on the original list of attackers I reviewed way back in summer of 2013 and he’s been a great little value forward ever since. Goal scoring is consistently decent to good in a team that has been almost relegated two seasons in a row. One of the things I love is that he averages about .2 expected assists a season, which means he probably won’t screw up a possession game around the box.

If you are looking for a solid performer, especially as a PL backup, I think you could do a lot worse than Ben Yedder.

How Do Coaches Learn?

How do we learn a thing? If you are in any normal pursuit, you probably read a book, or take a course. Maybe you check out some peer-reviewed journal articles, should you have access to materials at a university. Possibly, what you want to learn has some expert sites on the internet, so you trawl through their material to get up to speed. In a few rare cases, maybe you are lucky enough to have access to a subject matter expert and you ask them for information.

That’s for normal subjects, which covers the vast spectrum of all things humans need to know.

Now… how do you learn if you are a coach?

This is a question that has fascinated me since I started working inside of football, not least because I needed to figure out the best ways for me to impart my knowledge to coaches for them to use. So I started studying the problem inside of our clubs, and also took the English FA Level 2 Coaching Course to see how new coaches learn from a personal point of view.

What I figured out is this:

How coaches learn is

- an unbelievably important thing for people who work high up in football to know.

- horribly misunderstood by almost every decision maker I have encountered.

It’s not really anyone’s fault – it’s just that picking up coaching knowledge is so different than how humans learn almost anything else, it’s easy to make assumptions that seem natural, but are quite clearly wrong.

The issue here is that unlike almost every modern profession in the world, coaching is really an apprenticeship. Instead of learning via reading or attending lectures, the vast majority of knowledge you need to do the job comes via observing and doing. Theory is still important, but the practical element is dominant.

Before we carry on, let’s break the job down further – what do coaches actually do?

Choose a style of play for their team.

All the potential styles of play under the sun are possible, both in attack and defense.

Design training sessions to impart knowledge to their players about the style of play and specific tactics.

Once you have chosen how you want your team to play, you need to teach that to the players through training.

Teach. Communicate.

These elements are huge. If you can’t teach and communicate your ideas in a clear and effective manner, then you aren’t likely to be a good coach. And the subjects you need to teach to players are potentially vast and hugely different, but cover all areas of technique, tactics, phases of the game, and dynamic situation analysis of yourself, your teammates, and the opposition.

Football is complicated. That’s one of the things that makes it so captivating.

Interventions.

So much of what a coach actually does in training is correcting things that are not quite right, or teaching players about the options they had available. A teachable moment occurs, the coach stops training, rewinds to what they want to discuss, and then corrects actions to how they want it done in the future.

Conduct meetings.

These meetings can cover a variety of topics including reviewing training, reviewing games, what to expect from upcoming opponents, teaching new tactics, etc. You only get so much time on the pitch each week as a coach, and then everything else you need to give your players comes outside that area, typically through video review. That means meetings, and at the professional level, potentially lots of them.

These are just the basic elements of the job, but there are plenty additional responsibilities I have skipped over for the sake of brevity.

Right, so now we know what coaches do – the next step is learning how to do it.

In order to teach the material to players at an elite level, you have to master the material yourself. Where does that mastery come from?

- Playing the game. It’s possible you picked up some coaching basics via osmosis when your brain and body were busy learning how to play.

- Learning from past coaches you played under. Most of these will not be role models for the modern game, especially if you played in England.

- Coaches you apprentice under as a lower level, or assistant coach. Most new coaches land at their early jobs not based on what those jobs can teach them, but based on the fact that those were the jobs they could get. How many of those will be great learning environments?

- Coaching courses and licenses. In many cases, you are required to go on these to maintain your licenses. Like many courses in other pursuits, some are useful, some are not.

- Internet resources. Useful, but a mixed bag of material and rarely comprehensive.

- Watching other teams play? With regard to this one, how do you go about seeing tactics in game situations and turning them into training sessions for players?

Without belabouring the point too much, coaching is a knowledge-based profession that is also a practical apprenticeship, and it’s incredibly hard to find a good place to learn how to do it well.

Let’s step away from coaching as a whole, and make this simpler... Say I want to learn how to train a single tactical element from top to bottom, and do that well. Pick one item from the following list:

- Defensive pressure like Jurgen Klopp

- Generate great shots like Arsenal

- Execute set pieces like Atletico Madrid

Awesome, we have a topic… now what?

Uh… I don’t know?

You can’t exactly walk up to The Jurgen Klopp School of Football Coaching and get a degree in Rock and Roll Gegenpressen.

And as far as I am aware, there is no Arsene Wenger MBA of Elite Attacking on offer at any university in England, nor Cholo Simeone’s Science of Set Pieces anywhere at all.

This is unfortunate, because as a student of the game and someone who actually needs to know a lot of this stuff to be better at his job, I would enroll in this as an Executive MBA program in a heartbeat.

It sounds like I am joking, but this is serious stuff – if you are a young British coach that wants your team to learn German-style defensive pressure, how do you do it? Where do you do it?

The basic unit of coaching is a training session. Where can I find 10 or 20 or 30 training sessions strictly on imparting the knowledge of zonal defensive pressure and gegenpressing, explained in detail?

And more importantly, where can I find the video of those training sessions, so that I can learn what right and wrong look like in training, and be able to make crucial interventions? Because that is what you need to have in order to learn the material well enough to teach it to players who are unfamiliar with the concepts. You need example after example of what is right and wrong, and an expert pointing these things out and explaining the difference.

This isn’t just a personal lament – I’m writing about it because it explains one of the incredible oddities of the football world:

coaches almost never change styles.

This is weird, right? Coaches are typically smart, and football is a dynamic game that changes tactically on a regular basis. So why do so few coaches go on to incorporate other styles or develop new ones over the course of their career?

- As noted above, it’s hard to learn a new style in the first place.

- Where and when are they going to test out that style while learning it?

Successful learning environments are low pressure, where students can make and learn from mistakes while getting feedback. Making mistakes (and reviewing them) is fine because that is how we learn, especially in a hands-on, process-oriented job like coaching.

All first team coaching jobs in pretty much every professional league in the world are high pressure environments. You’re a first team coach – your job is to win matches. If you don’t win matches, you will be replaced. Period.

These two things are wholly incompatible. Being a first team coach means you exist in a terrible learning environment.

Additionally, when pressure increases, we tend to revert back to what we know and think works best. Which in coaching terms will be the tactics you are most familiar with from your historic learning journey.

Thus is it any wonder that we rarely see professional football coaches learn new things? For most of them, their job makes for an environment totally inhospitable to experimentation, which is crucial in the pursuit and mastery of new knowledge.

THIS IS A HUGE PROBLEM!

Say you want to hire a new head coach because your old one was too successful and has been poached by a bigger club. You find a new coach whose personality works, who seems open to new things, but his past teams have only exhibited two of the four crucial components to your club’s style of play. What do you do?

“Well, [new coach] can learn what they don’t already know.”

Maybe. Probably not.

Definitely not if this change is happening in-season, or if the job is a high pressure job – as pretty much all of them are. Even if they want to increase their knowledge, it might not be possible because the learning environment is toxic.

At the end of the day, understanding the problem fundamentally changes how we address it.

Instead of “[new coach] can learn what they don’t already know” decision makers need to ask the following: “How do we enable [new coach] to learn what we want them to know?”

New coaches are what they are. Do not expect them to fundamentally change on their own – we have an overwhelming amount of evidence that indicates that doesn’t happen. Instead you need to think about empowering them to learn and provide subject matter experts to bolster their knowledge.

So How Can a Coach Learn New Things?