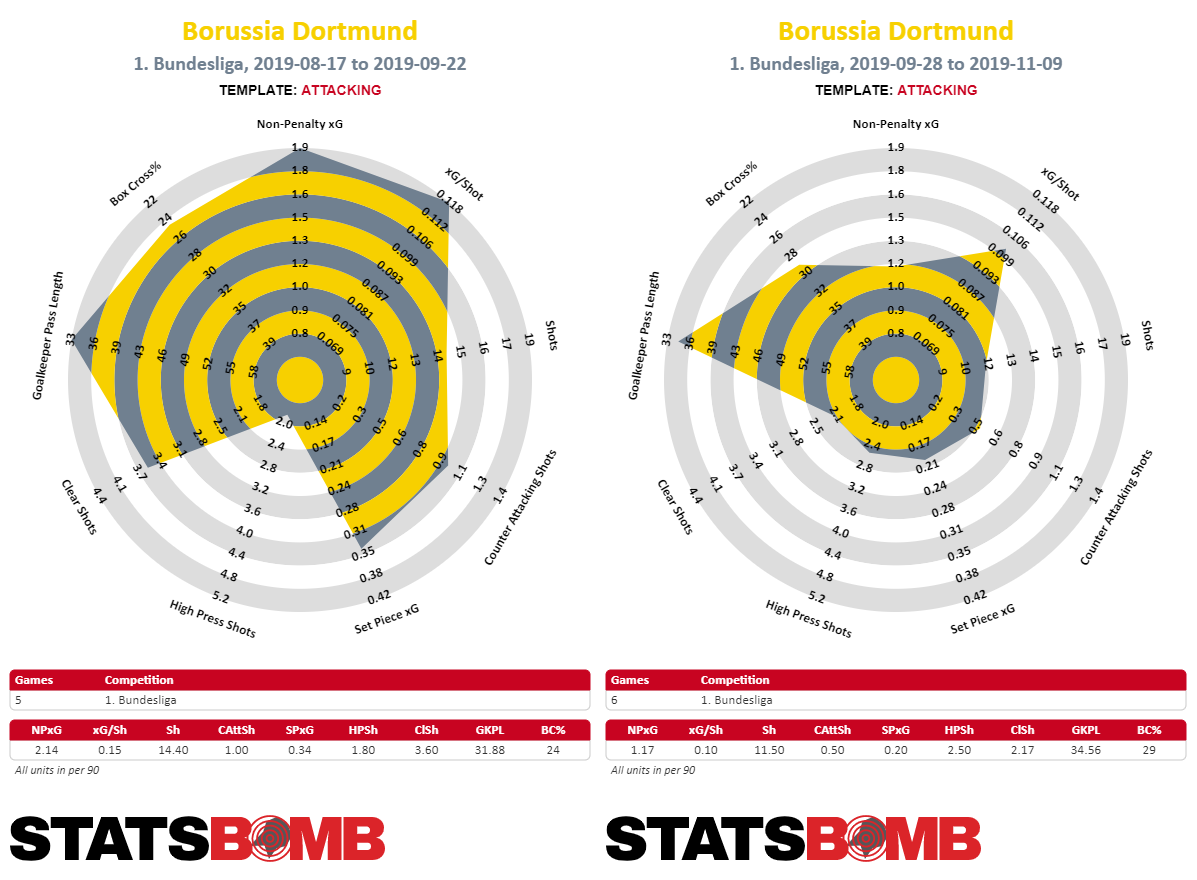

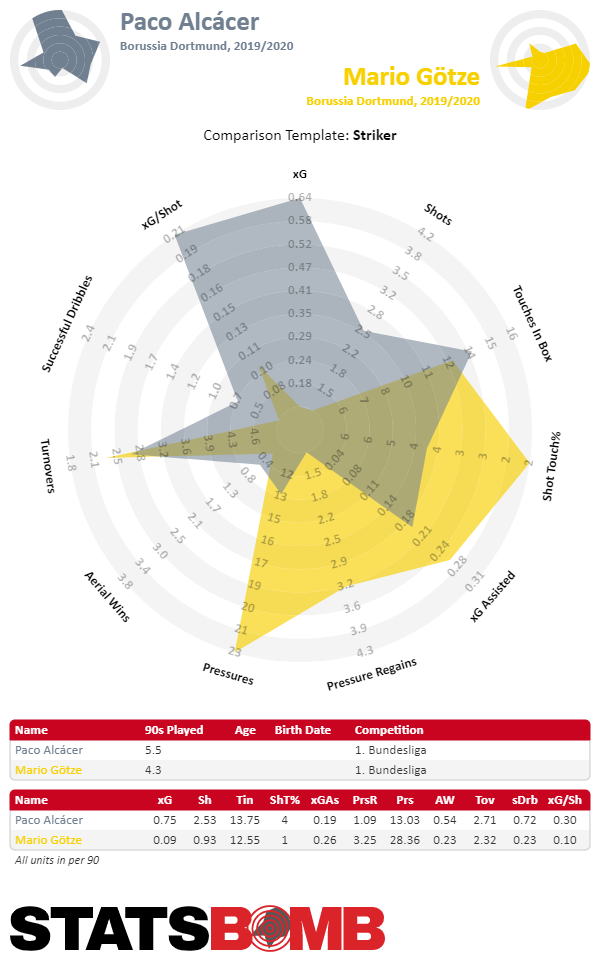

Borussia Dortmund are, in a sporting sense, in trouble. The league table fails to fully reflect the situation, but a number of performances over the last few weeks were, particularly in attack, alarmingly harmless. Before the season, questions were asked centred on the personnel situation in the striker department and whether BVB should buy another alternative to Paco Alcácer. Those questions are now more pressing than ever. Alcácer performed very well on the first five matchdays of the Bundesliga, which he spent as part of Dortmund’s starting XI. His attacking presence, contribution to shooting attempts and efficient playing style in the opponent's penalty box make him a valuable asset. His absence after the match against Werder Bremen became noticeable immediately.  Comparison of Dortmund’s values in attack until Alcácer’s absence and since. Overall, Dortmund amassed fewer shots, while at the same time being less creative in attack, which one can infer from the larger rate of crosses, for example. Obviously, the toothless attacking performances were not singularly down to the absence of Alcácer, seeing as Dortmund faced some of the powerhouses of the league in Schalke, Mönchengladbach and Bayern, who all know to be solid defensively in their own ways. Still, it became evident that Dortmund do not have an adequate replacement at hand to allow the ball progression to flow through that one important target player, particularly in the transition into the final third and even more so when playing into the box. Mario Götze adds a number of qualities, but he is often used incorrectly when played at the very front of the formation. He would be of better use in central midfield, where his footballing intelligence and compartmentalised playing style would shine through for the better of the team. For the moment, though, Götze seems to have been tabbed as Alcácer’s replacement. However, this cannot be a long-term solution for a club as ambitious as BVB, especially as Götze’s time with the club may be over in the summer.

Comparison of Dortmund’s values in attack until Alcácer’s absence and since. Overall, Dortmund amassed fewer shots, while at the same time being less creative in attack, which one can infer from the larger rate of crosses, for example. Obviously, the toothless attacking performances were not singularly down to the absence of Alcácer, seeing as Dortmund faced some of the powerhouses of the league in Schalke, Mönchengladbach and Bayern, who all know to be solid defensively in their own ways. Still, it became evident that Dortmund do not have an adequate replacement at hand to allow the ball progression to flow through that one important target player, particularly in the transition into the final third and even more so when playing into the box. Mario Götze adds a number of qualities, but he is often used incorrectly when played at the very front of the formation. He would be of better use in central midfield, where his footballing intelligence and compartmentalised playing style would shine through for the better of the team. For the moment, though, Götze seems to have been tabbed as Alcácer’s replacement. However, this cannot be a long-term solution for a club as ambitious as BVB, especially as Götze’s time with the club may be over in the summer.  Götze and Alcácer could hardly be any more different from one another—even if we dismiss the context of the games. This holds especially true for the way they integrate themselves into general play, but also for their options in counter-attacks and fast attacks.

Götze and Alcácer could hardly be any more different from one another—even if we dismiss the context of the games. This holds especially true for the way they integrate themselves into general play, but also for their options in counter-attacks and fast attacks.

What, exactly, is Alcácer?

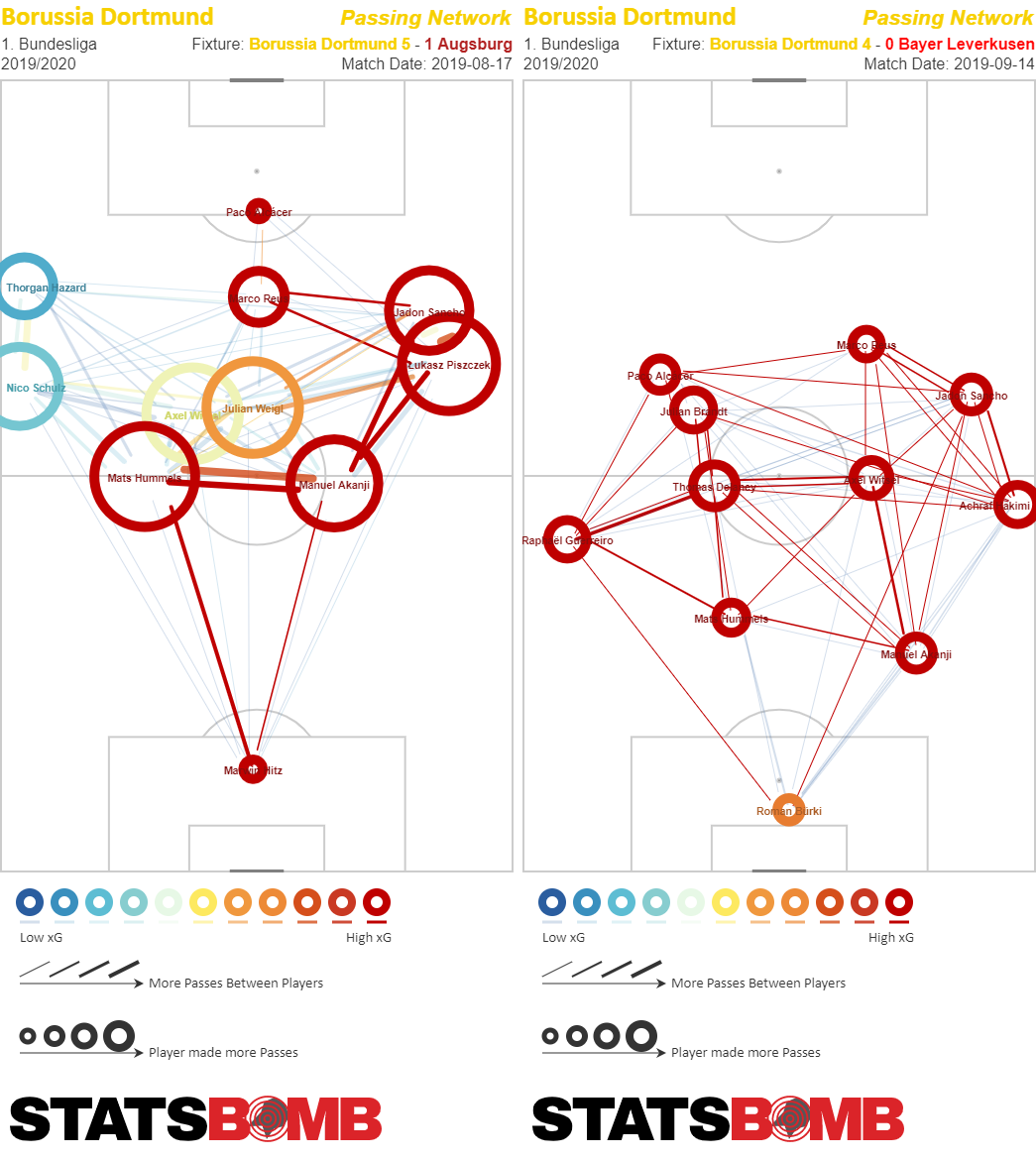

A striking thing about Alcácer is how he can adapt his playing style to respective situations in a match. When Dortmund are dominating a game, with long spells of possession, he positions himself mostly in the centre of the field of play to intuitively remain a passing option for the attacking players next to and behind him. He is present in proximity to the opponent’s defenders and occupies them, so that they cannot move up and defend more proactively or intercept inverse movements from a player such as Jadon Sancho. When Dortmund have to counter from deeper positions, though, as was the case in the first half against Bayer Leverkusen, as Bayer played a quite intensive midfield pressing, Alcácer frequently drifts to one side. In this particular game, he moved toward the left, attempted to intercept medium-high passes that came through the channels of Lars Bender and Kai Havertz and to enter sprinting contests with Jonathan Tah.  In the inaugural league match of the season, BVB played quite asymmetrically, with Alcácer as a central target player. Against Leverkusen, on the other hand, Alcácer moved toward the left side frequently, especially in a tough first half. He received passes and tried to carry on Dortmund’s counter-attacking. This is Alcácer’s big strength: He is neither a classic penalty-box striker (despite his eye for goal and intelligent positioning), nor is he a true counter-attacker (despite his quickness and evasive movement). He unites both elements very well, making him the perfect striker for BVB, seeing as they have to adapt their playing style on occasion because of their vulnerability against a high press. An Alcácer copy? This short analysis then poses the question of whether Dortmund should make an effort in the coming summer to sign a “second” Paco Alcácer. The statistical numbers from this and last season show that the Bundesliga have a few strikers that would fit that bill and have a statistical resemblance of roughly 80%. First, Kevin Volland, who has transformed into a central target player recently but can still play through the half-space given his career history. Peter Bosz has used him on the left wing five times this season, from where Volland moved inwards frequently and always attempted to create proximity to the central striker. Volland can perform similarly evasive movements in a counter-attacking scheme to those of Alcácer and carry on the attack. Another tactically flexible striker who falls in the statistical category of Alcácer is Andrej Kramarić. In the current campaign, a knee injury has limited the Croatian to only two appearances. But in recent years at Hoffenheim, he has regularly proved he can play his part in the attack both from the centre and from a position in the left half-space. He distinguishes himself from Volland insofar as he generates more high-quality shooting attempts, while at the same time playing with more risk, especially when deployed up front, losing the ball more frequently than Volland. The third striker in this equation is Alfreð Finnbogason, but he cannot be an option for Dortmund based on his age, career to this point and susceptibility to injury.

In the inaugural league match of the season, BVB played quite asymmetrically, with Alcácer as a central target player. Against Leverkusen, on the other hand, Alcácer moved toward the left side frequently, especially in a tough first half. He received passes and tried to carry on Dortmund’s counter-attacking. This is Alcácer’s big strength: He is neither a classic penalty-box striker (despite his eye for goal and intelligent positioning), nor is he a true counter-attacker (despite his quickness and evasive movement). He unites both elements very well, making him the perfect striker for BVB, seeing as they have to adapt their playing style on occasion because of their vulnerability against a high press. An Alcácer copy? This short analysis then poses the question of whether Dortmund should make an effort in the coming summer to sign a “second” Paco Alcácer. The statistical numbers from this and last season show that the Bundesliga have a few strikers that would fit that bill and have a statistical resemblance of roughly 80%. First, Kevin Volland, who has transformed into a central target player recently but can still play through the half-space given his career history. Peter Bosz has used him on the left wing five times this season, from where Volland moved inwards frequently and always attempted to create proximity to the central striker. Volland can perform similarly evasive movements in a counter-attacking scheme to those of Alcácer and carry on the attack. Another tactically flexible striker who falls in the statistical category of Alcácer is Andrej Kramarić. In the current campaign, a knee injury has limited the Croatian to only two appearances. But in recent years at Hoffenheim, he has regularly proved he can play his part in the attack both from the centre and from a position in the left half-space. He distinguishes himself from Volland insofar as he generates more high-quality shooting attempts, while at the same time playing with more risk, especially when deployed up front, losing the ball more frequently than Volland. The third striker in this equation is Alfreð Finnbogason, but he cannot be an option for Dortmund based on his age, career to this point and susceptibility to injury.

A Physical Alternative

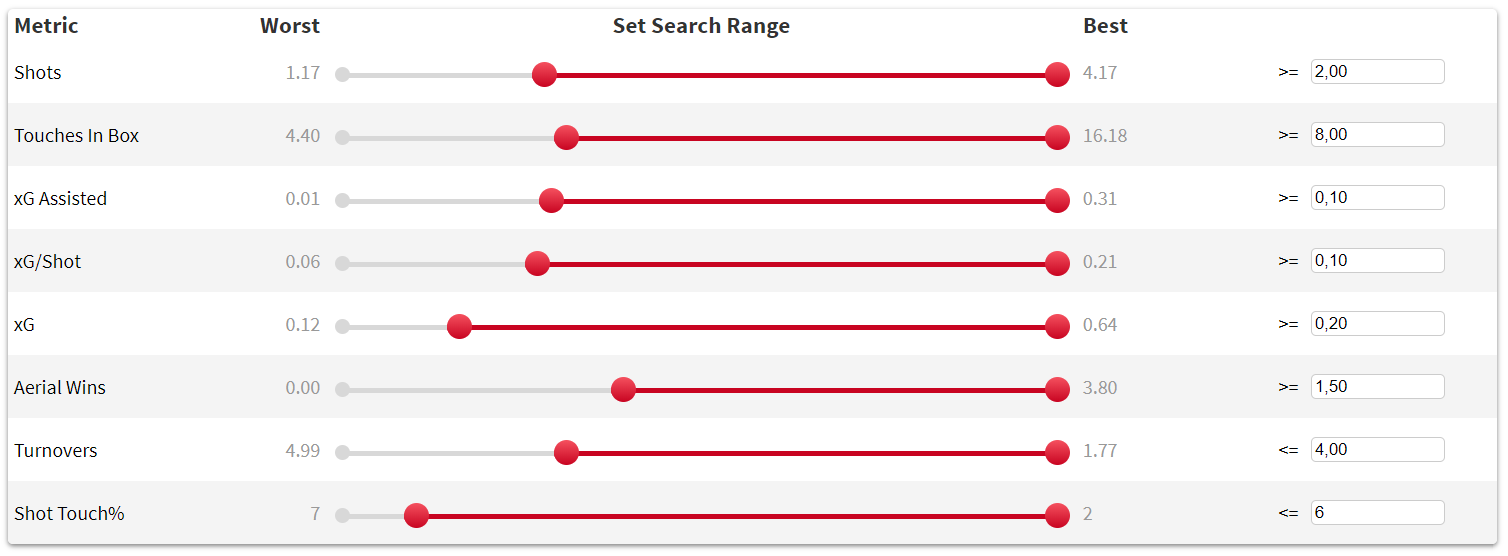

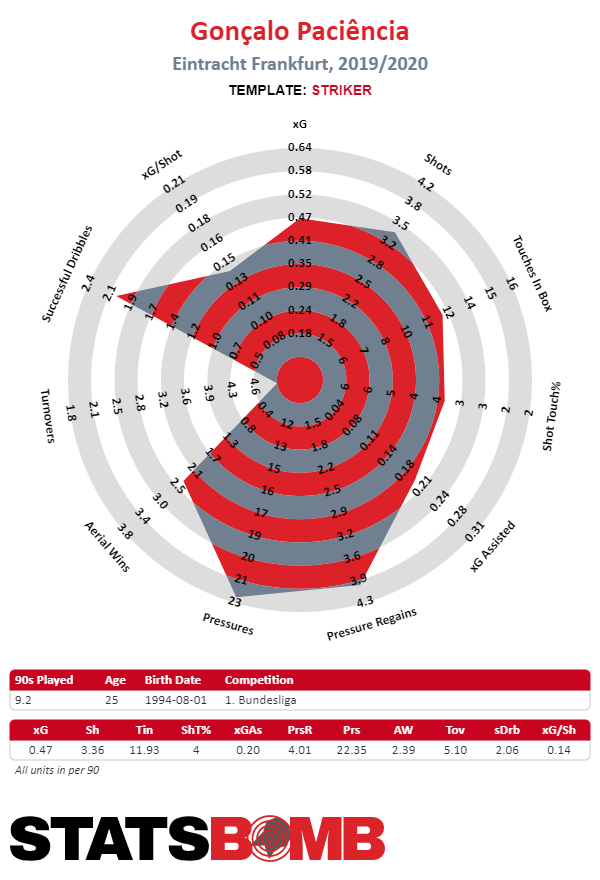

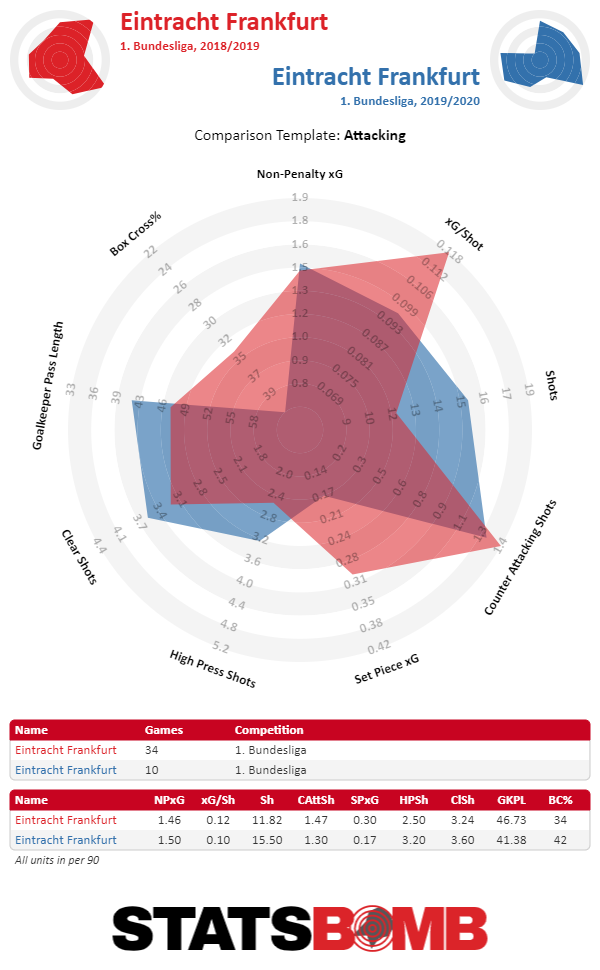

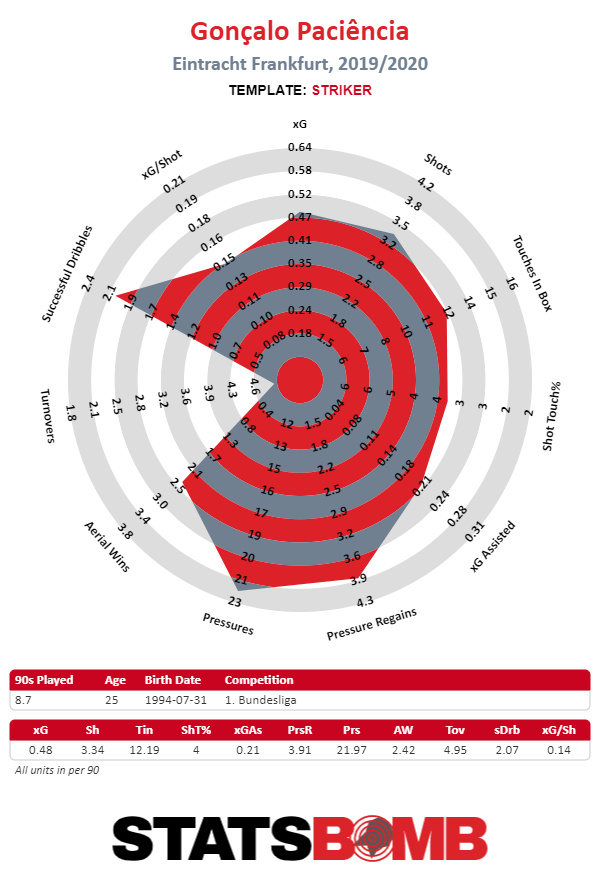

The search for an alternative to Alcácer can also be looked at from a different perspective. The cry for a physically strong striker grows louder by the day. And Lucien Favre, despite what he may have said publicly, has given chances to large target players over his career. Such a signing cannot be ruled out at the moment, anyway. Even more so since, in certain matches, BVB manage quite well to perfectly prepare breakthroughs to the touchline through a player like Achraf Hakimi. Sancho is essentially more of a half-space striker than wing-attacker. As such, one side of Dortmund's team could create assists without sending in useless crosses. Additionally, a striker competent in aerial duels could be a receiving option for Mats Hummels’ early long balls against an attacking press. To find such a striker, the search criteria for Bundesliga players must be defined accordingly: The striker still has to be reliable on the ball, able to be a part of the general attacking play and at the same time bring a significant prowess in the air.  These criteria, used for last and this season, produces four results: André Silva, Gonçalo Paciência, Lucas Alario and, naturally, Robert Lewandowski. For Paciência, the result only refers to last season, in which he played only sparingly. In the current campaign, he would fall off the radar due to too many losses of possession, but he remains an interesting alternative to Silva and Alario regardless.

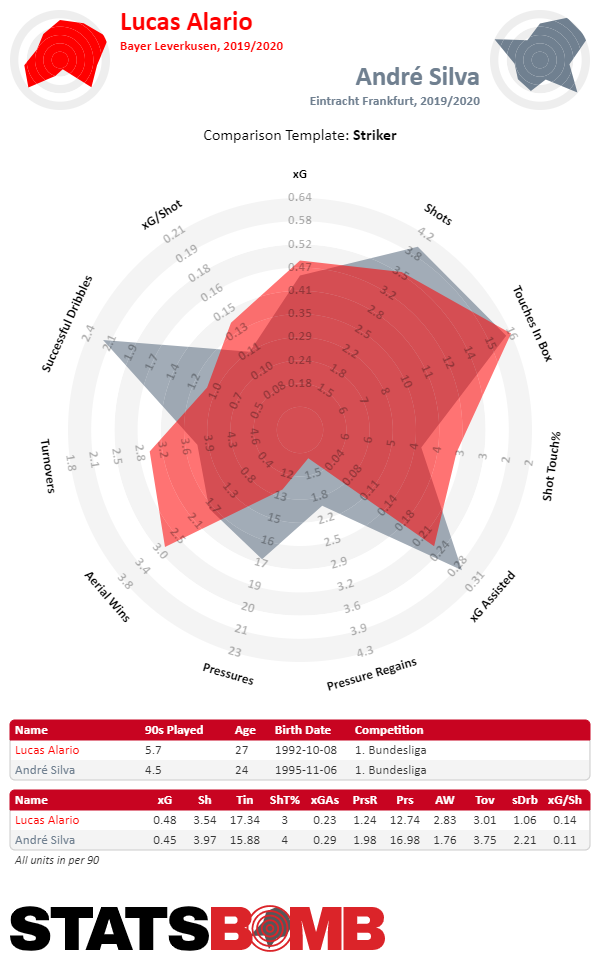

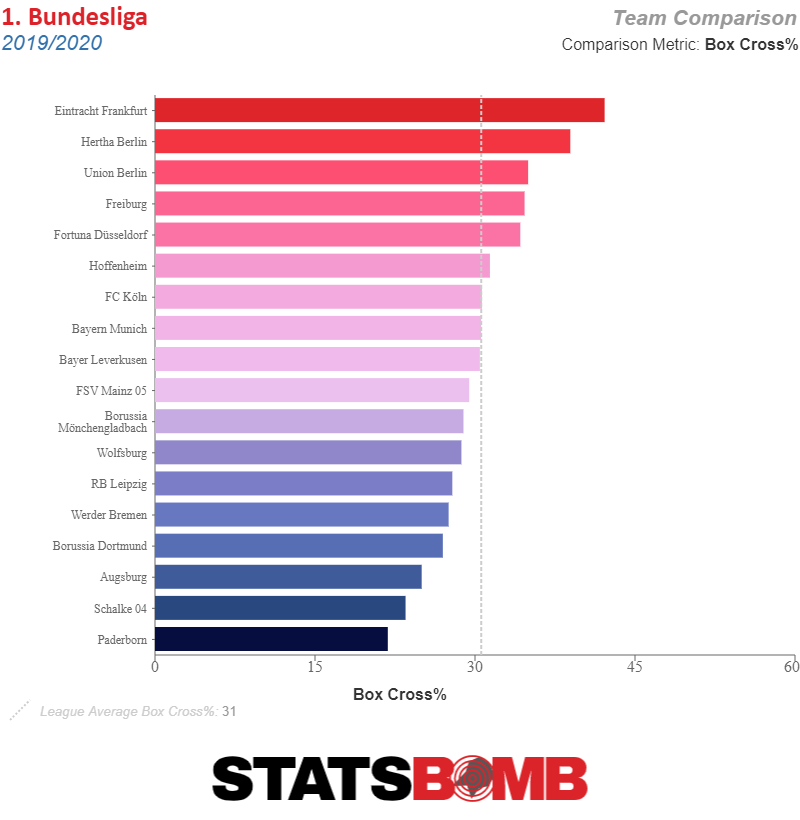

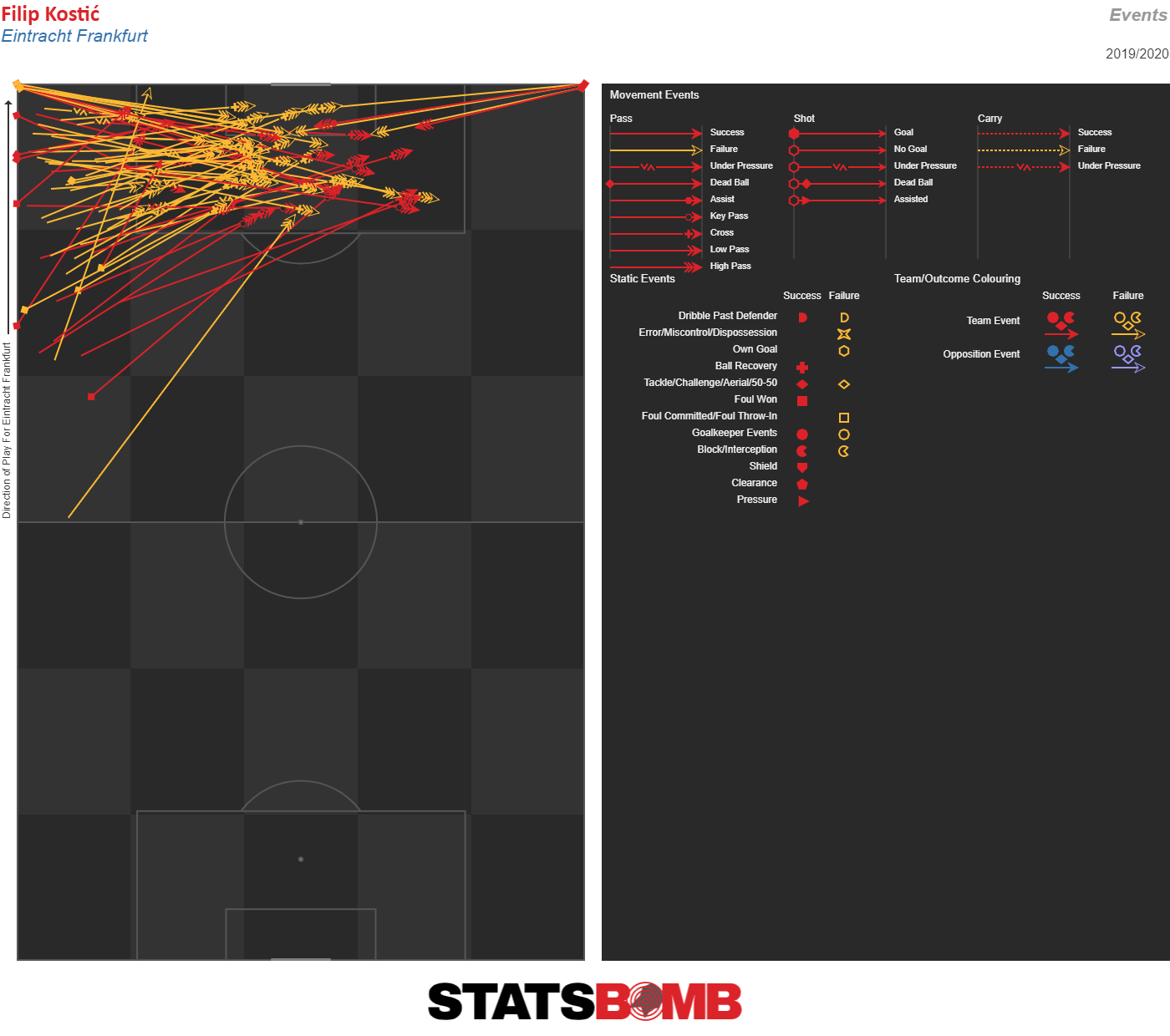

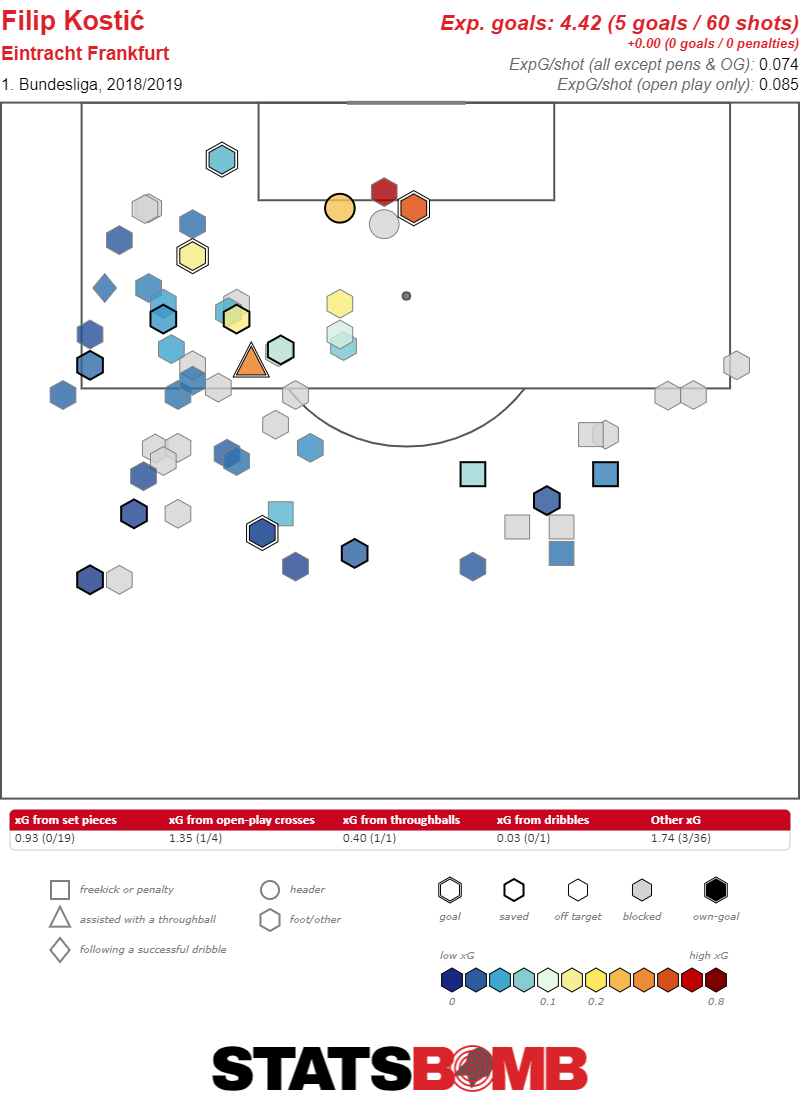

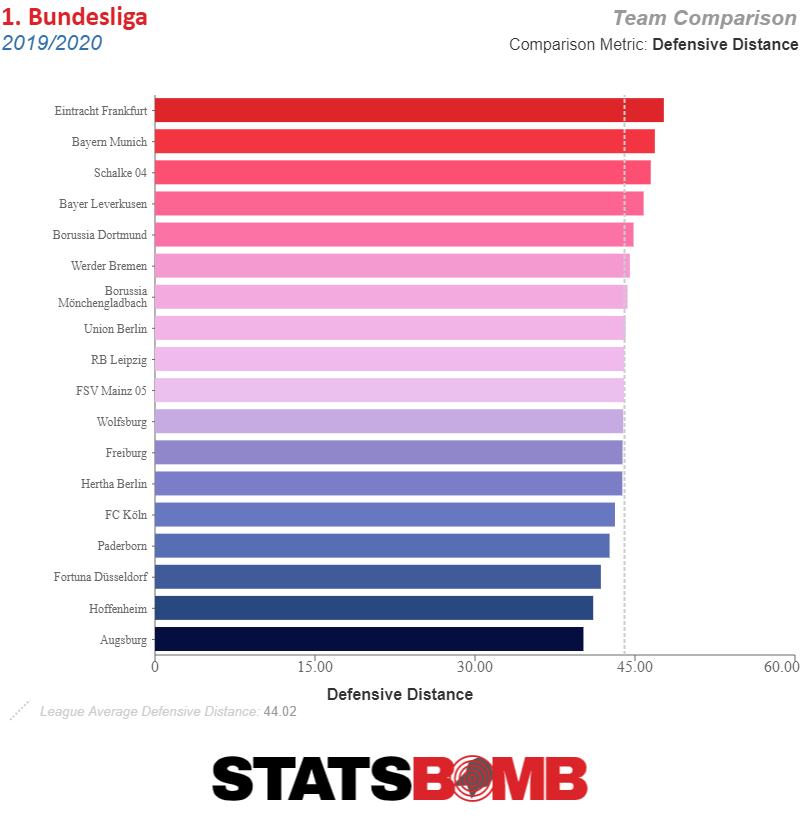

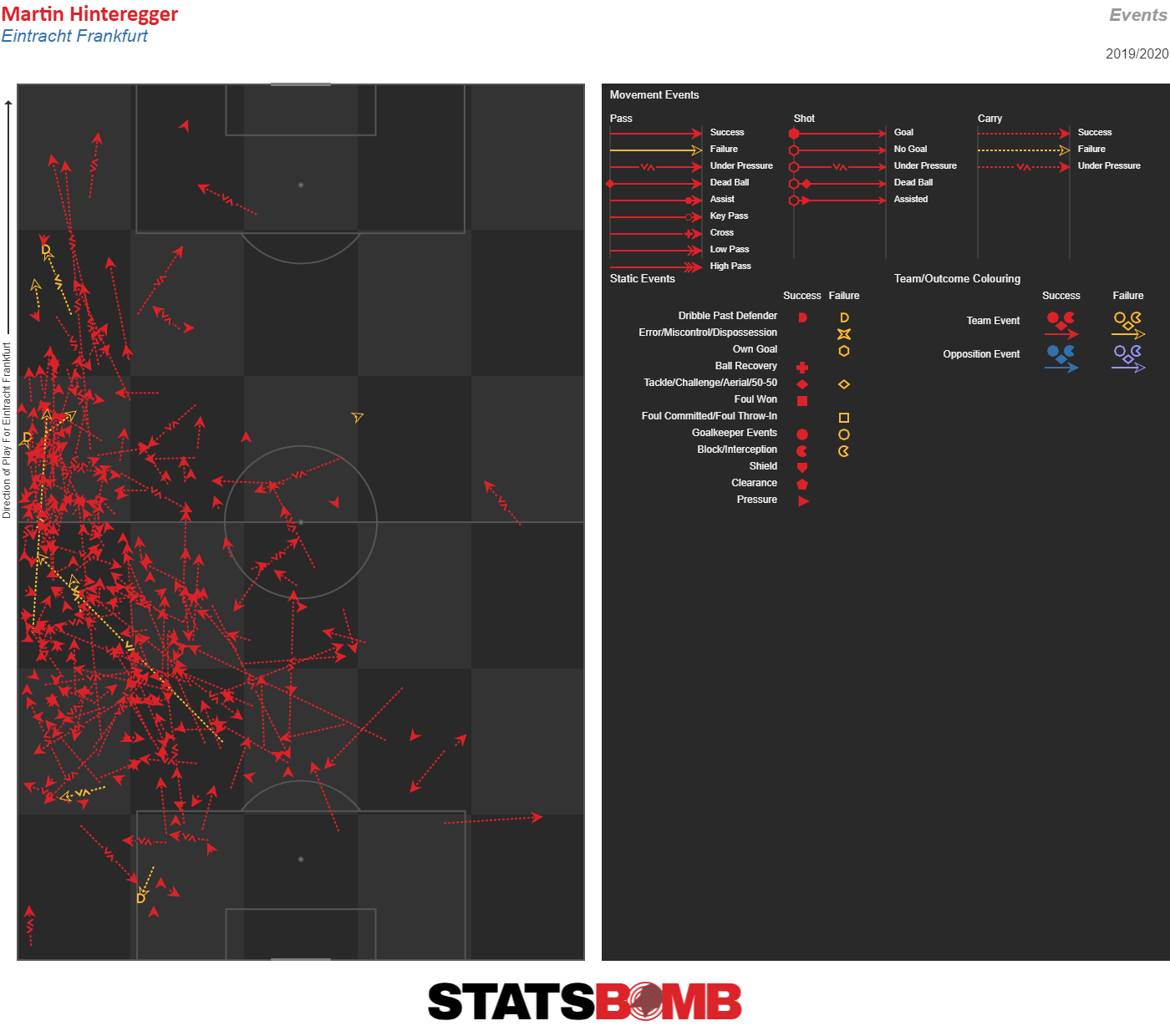

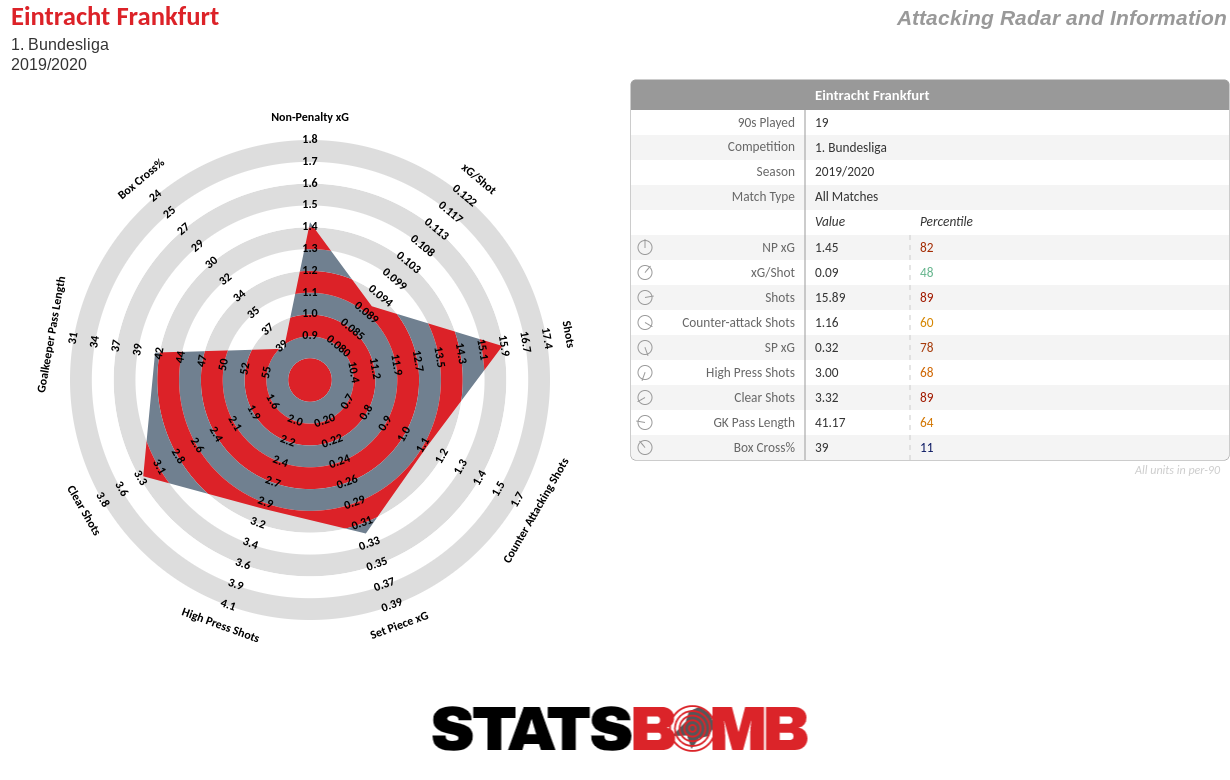

These criteria, used for last and this season, produces four results: André Silva, Gonçalo Paciência, Lucas Alario and, naturally, Robert Lewandowski. For Paciência, the result only refers to last season, in which he played only sparingly. In the current campaign, he would fall off the radar due to too many losses of possession, but he remains an interesting alternative to Silva and Alario regardless.  Those two, in turn, differ from one another in the way they participate in general play. Silva is more involved in situations in which he is not the one to look for the shooting attempt, rather setting up players from a zone ahead of the penalty box. Of course, this is also down to the playing style of Eintracht Frankfurt, in whose 3-4-1-2 or 3-5-2 the ball-near striker drops deeper during attacks along the wings. Particularly when playing over Filip Kostić, Silva drops back a bit, meaning he is not the furthest-most target player. Alario, on the other hand, constitutes a classic spearhead in the Bayer Leverkusen system, playing a role more oriented toward shooting attempts in comparison to Alcácer, which is why he is less likely to take part in the prepared combination play, bus also why he loses possession in the final third less often.

Those two, in turn, differ from one another in the way they participate in general play. Silva is more involved in situations in which he is not the one to look for the shooting attempt, rather setting up players from a zone ahead of the penalty box. Of course, this is also down to the playing style of Eintracht Frankfurt, in whose 3-4-1-2 or 3-5-2 the ball-near striker drops deeper during attacks along the wings. Particularly when playing over Filip Kostić, Silva drops back a bit, meaning he is not the furthest-most target player. Alario, on the other hand, constitutes a classic spearhead in the Bayer Leverkusen system, playing a role more oriented toward shooting attempts in comparison to Alcácer, which is why he is less likely to take part in the prepared combination play, bus also why he loses possession in the final third less often.  Silva, Alario and even Paciência offer the physical qualities needed for the proposed profile. The last two seem a tad stronger in the air, which can become apparent in pressure situations within the penalty box. Silva and Alario also have sufficient footballing qualities to not represent a steep decline from the rest of Dortmund's attack where they would only function as a last-resort target player and force BVB into attacking with nine instead of ten outfield players. The preferred option remains an attack with Alcácer. But for more tactical flexibility, for example, to increase the success rate of attacks over the wings or to play against an opponent's isolated high press, one of these strikers could help BVB.

Silva, Alario and even Paciência offer the physical qualities needed for the proposed profile. The last two seem a tad stronger in the air, which can become apparent in pressure situations within the penalty box. Silva and Alario also have sufficient footballing qualities to not represent a steep decline from the rest of Dortmund's attack where they would only function as a last-resort target player and force BVB into attacking with nine instead of ten outfield players. The preferred option remains an attack with Alcácer. But for more tactical flexibility, for example, to increase the success rate of attacks over the wings or to play against an opponent's isolated high press, one of these strikers could help BVB.

Appendix: A Foreign Alternative?

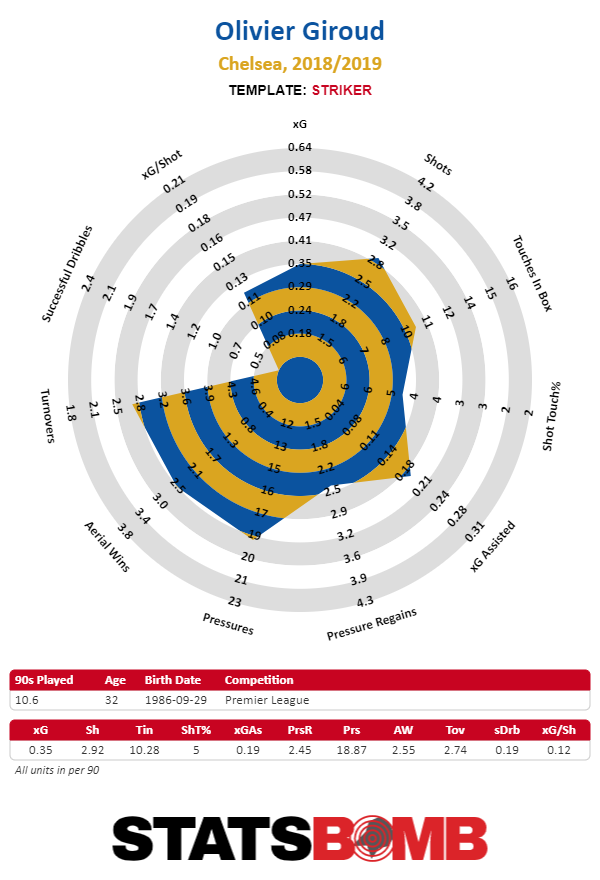

The current rumour mill concerning a new central striker for Dortmund mostly focuses on players from outside the Bundesliga. An interesting candidate who would also fill the postulated criteria is Olivier Giroud. Due to his age, the Frenchman cannot be considered a long-term alternative, but perhaps an alternative to Alcácer for a few seasons. Giroud naturally distinguishes himself with his physical play, but likewise with a footballing quality that would not make him an alien element in Dortmund's attack. The 33-year-old receives the ball in the penalty box often enough, but at the same time can involve himself in the general play from the outside and play layoffs in deeper counter-attacks. His numbers suggest as much.  Another name, and one that would fit the category of “Fantasy Manager”, is Erling Håland of Salzburg, arguably the most wanted young striker in Europe. His fit at BVB is not an obvious one, however. While Håland is outstanding in terms of offensive productivity, a few smaller technical mistakes in his ball-handling abilities leave some question marks. Salzburg's playing style is predicated on a certain verticality and openness to risk, so a few losses of possession at the top of the formation are not a big problem. However, Håland does not seem to be overly stable in sophisticated combinations. Additionally, he has to prove how far he can develop other components of his finishing game given his height and physicality — especially in the air. Right now he is probably not a realistic option for BVB, even though they have a strong need for a big talent and have the ambition to attract this kind of player. You can also find this article in German on Spielverlagerung.de. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

Another name, and one that would fit the category of “Fantasy Manager”, is Erling Håland of Salzburg, arguably the most wanted young striker in Europe. His fit at BVB is not an obvious one, however. While Håland is outstanding in terms of offensive productivity, a few smaller technical mistakes in his ball-handling abilities leave some question marks. Salzburg's playing style is predicated on a certain verticality and openness to risk, so a few losses of possession at the top of the formation are not a big problem. However, Håland does not seem to be overly stable in sophisticated combinations. Additionally, he has to prove how far he can develop other components of his finishing game given his height and physicality — especially in the air. Right now he is probably not a realistic option for BVB, even though they have a strong need for a big talent and have the ambition to attract this kind of player. You can also find this article in German on Spielverlagerung.de. Header image courtesy of the Press Association

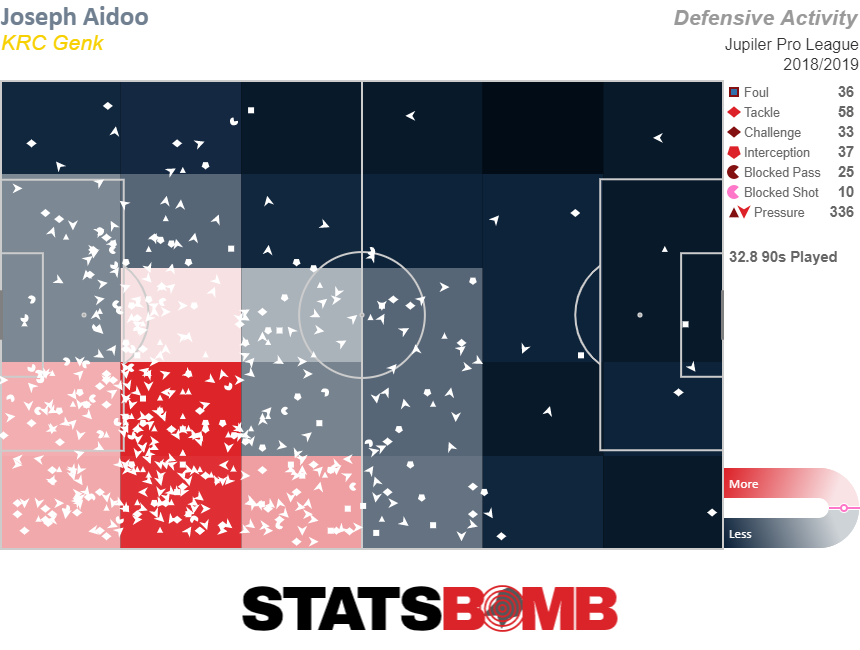

It was a job well done, but it was still surprising when the club elected to hand him a two-year contract. He was a

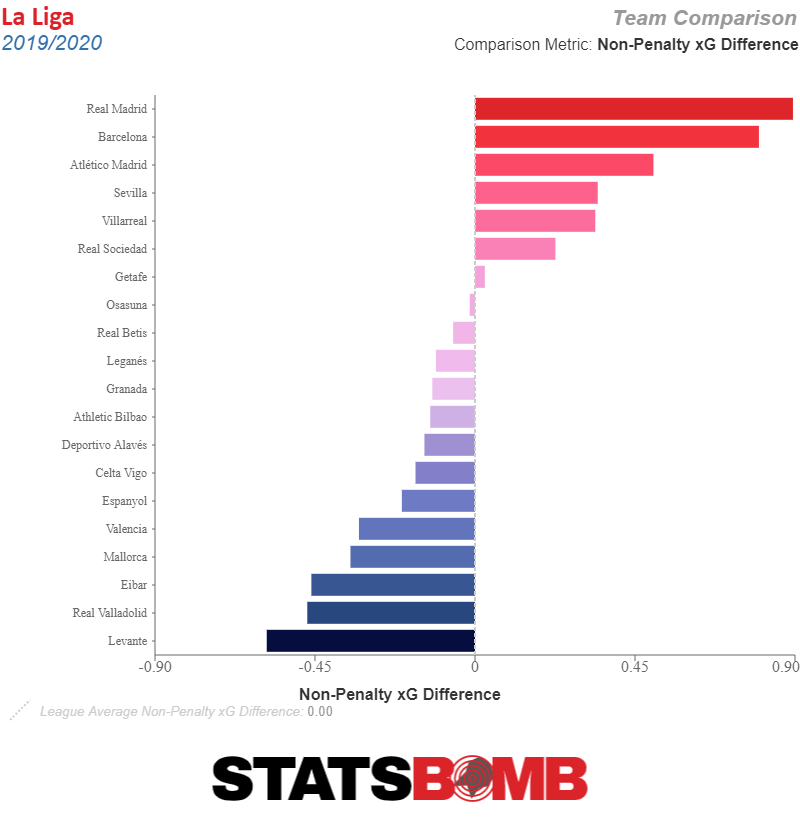

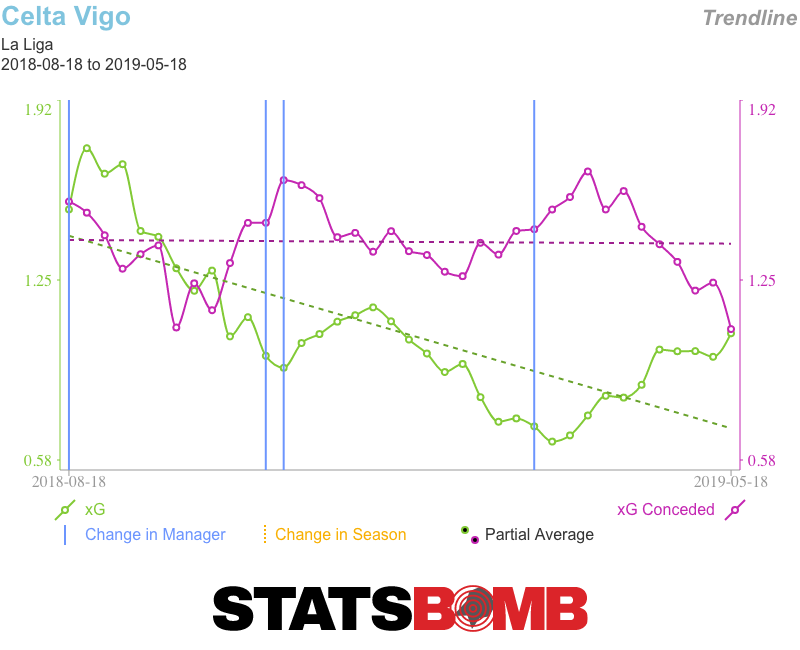

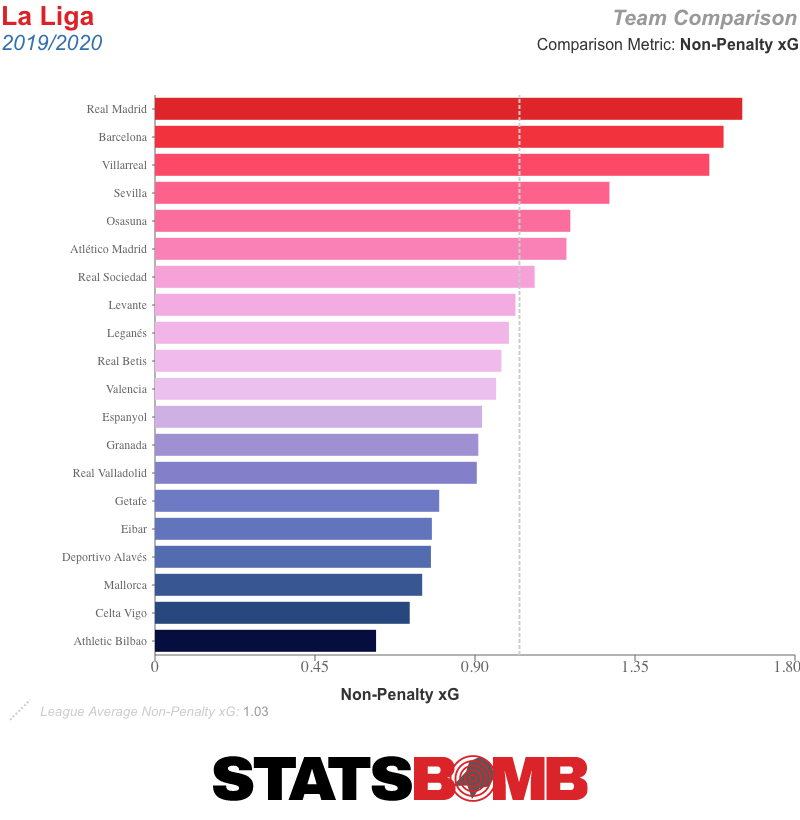

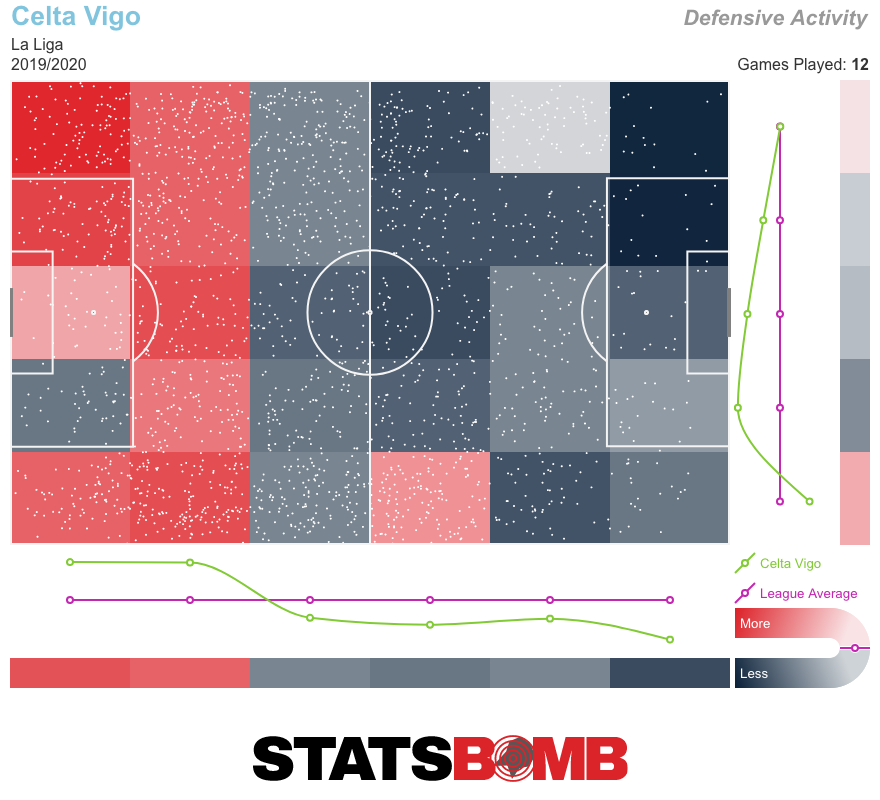

It was a job well done, but it was still surprising when the club elected to hand him a two-year contract. He was a  Celta have taken fewer shots (8.67) than all but Alavés, and their average shot quality (0.08 xG/Shot) is one of the lowest in the league. While under Escribá last season they were hardly an attacking powerhouse, even with the summer reinforcements, their numbers are even worse. They are creating less from pretty much everywhere: set pieces, counter attacks, high press situations. And it’s not even as if they’ve enjoyed a lot of attacking territory without quite managing to get off shots (a theory

Celta have taken fewer shots (8.67) than all but Alavés, and their average shot quality (0.08 xG/Shot) is one of the lowest in the league. While under Escribá last season they were hardly an attacking powerhouse, even with the summer reinforcements, their numbers are even worse. They are creating less from pretty much everywhere: set pieces, counter attacks, high press situations. And it’s not even as if they’ve enjoyed a lot of attacking territory without quite managing to get off shots (a theory  In contrast, at Celta he is part of one of the deepest defensive teams in La Liga.

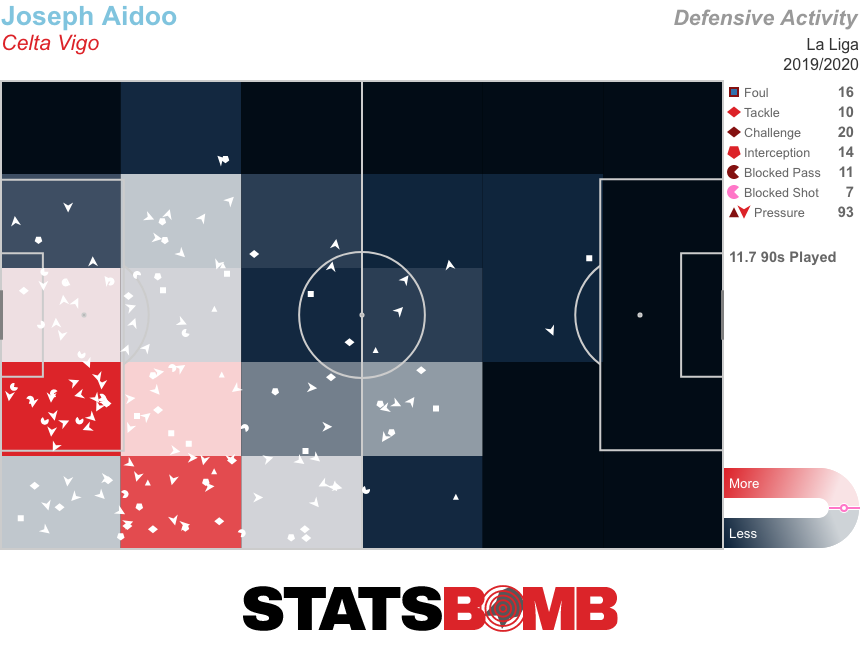

In contrast, at Celta he is part of one of the deepest defensive teams in La Liga.  He's performing the majority of his defensive work inside his own penalty area. He is involved in more aerial duels than before and is frequently losing out on the ground.

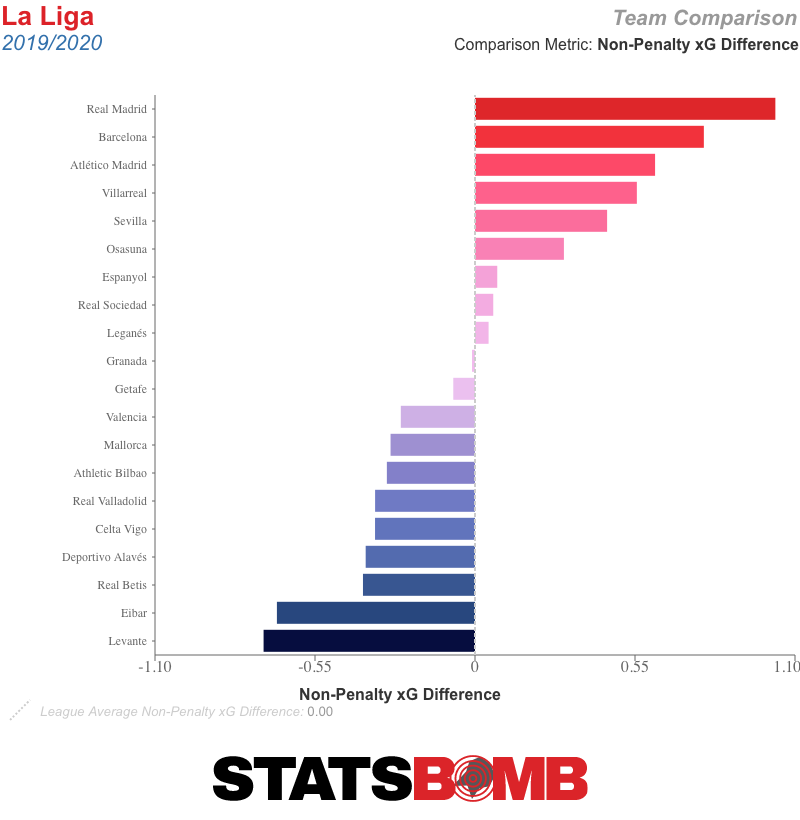

He's performing the majority of his defensive work inside his own penalty area. He is involved in more aerial duels than before and is frequently losing out on the ground.  Celta’s underlying defensive numbers are the seventh-worst in the league. Not only are they in the bottom three with the third-worst goal difference in the division, but they are also in the bottom five in xG difference. By that measure, they have been worse this season (-0.34 xG difference per match versus -0.21) than during Escribá’s 12-match stretch down the back end of last.

Celta’s underlying defensive numbers are the seventh-worst in the league. Not only are they in the bottom three with the third-worst goal difference in the division, but they are also in the bottom five in xG difference. By that measure, they have been worse this season (-0.34 xG difference per match versus -0.21) than during Escribá’s 12-match stretch down the back end of last.  In the face of those top-line and underlying numbers, Celta had little choice but to remove Escribá from a position for which he was never really suited. After a series of unsuccessful and short-lived coaches, surely they would next seek stability in a proven operator like Abelardo or Quique Setién, the latter of whom seems tailor-made for their squad. Instead, they turned to Óscar García, the antonym of stability. Across seven previous coaching jobs, the longest the 46-year-old has ever remained in a position is his season and a half at Red Bull Salzburg. The others have lasted one season or less. His last two, at Saint-Étienne in France and Olympiacos in Greece, ended within 14 matches of taking charge. García’s possession-based approach certainly looks more apt for a squad that features midfield talents such as Stanislav Lobotka and Fran Beltrán, and apparently Celta have considered him before. But it is hard to get over the impression that he is still riding his earlier associations with Barcelona (where he acted as a youth coach), Johan Cruyff (whom he played under at Barcelona and worked with as an assistant during sporadic Catalonia national team matches) and Salzburg. To say that the jury’s out on him would almost be a generous appraisal. Celta had to do something. Simply removing the restrictions created by their previous system should nudge their attacking output up to an acceptable level. But this is also an appointment that could go very wrong indeed. The plan Celta once clung to so firmly appears to have gusted off into the Atlantic Ocean.

In the face of those top-line and underlying numbers, Celta had little choice but to remove Escribá from a position for which he was never really suited. After a series of unsuccessful and short-lived coaches, surely they would next seek stability in a proven operator like Abelardo or Quique Setién, the latter of whom seems tailor-made for their squad. Instead, they turned to Óscar García, the antonym of stability. Across seven previous coaching jobs, the longest the 46-year-old has ever remained in a position is his season and a half at Red Bull Salzburg. The others have lasted one season or less. His last two, at Saint-Étienne in France and Olympiacos in Greece, ended within 14 matches of taking charge. García’s possession-based approach certainly looks more apt for a squad that features midfield talents such as Stanislav Lobotka and Fran Beltrán, and apparently Celta have considered him before. But it is hard to get over the impression that he is still riding his earlier associations with Barcelona (where he acted as a youth coach), Johan Cruyff (whom he played under at Barcelona and worked with as an assistant during sporadic Catalonia national team matches) and Salzburg. To say that the jury’s out on him would almost be a generous appraisal. Celta had to do something. Simply removing the restrictions created by their previous system should nudge their attacking output up to an acceptable level. But this is also an appointment that could go very wrong indeed. The plan Celta once clung to so firmly appears to have gusted off into the Atlantic Ocean.  For some reason, La Liga defenders just can’t stop fouling Nabil Fekir. He has won 5.49 fouls per 90 minutes so far this season, over two more than Dani Parejo, the second-most fouled. He is tripped wherever he treads.

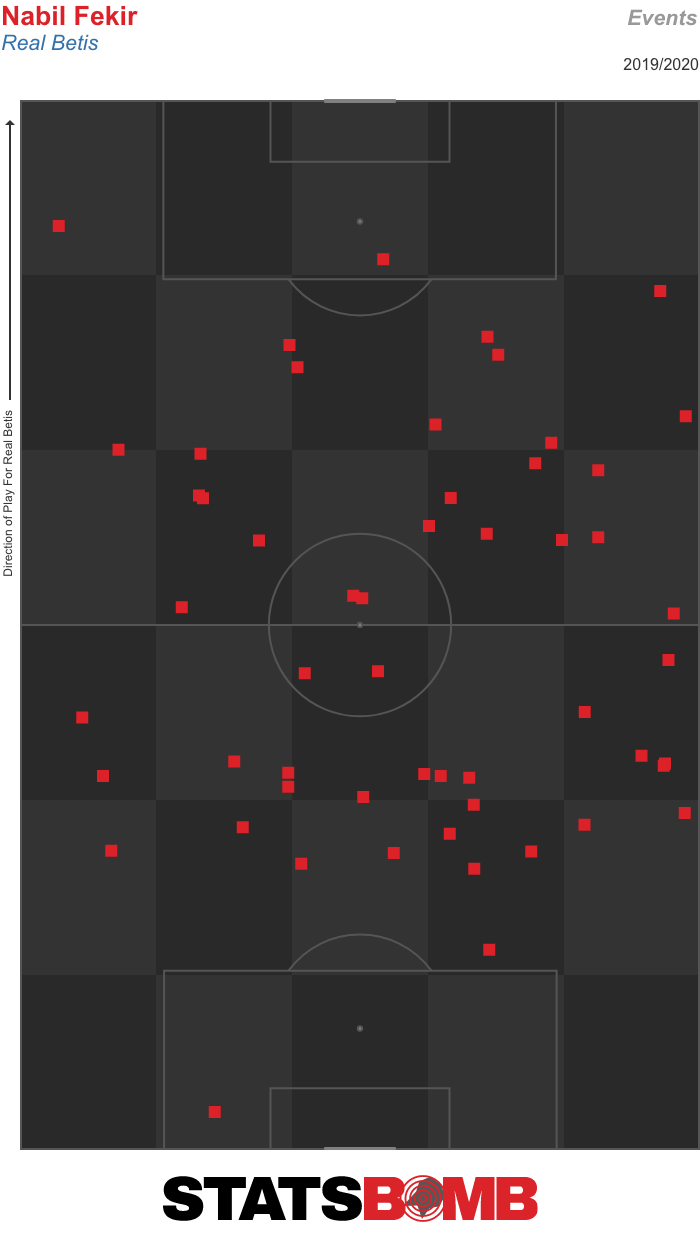

For some reason, La Liga defenders just can’t stop fouling Nabil Fekir. He has won 5.49 fouls per 90 minutes so far this season, over two more than Dani Parejo, the second-most fouled. He is tripped wherever he treads.

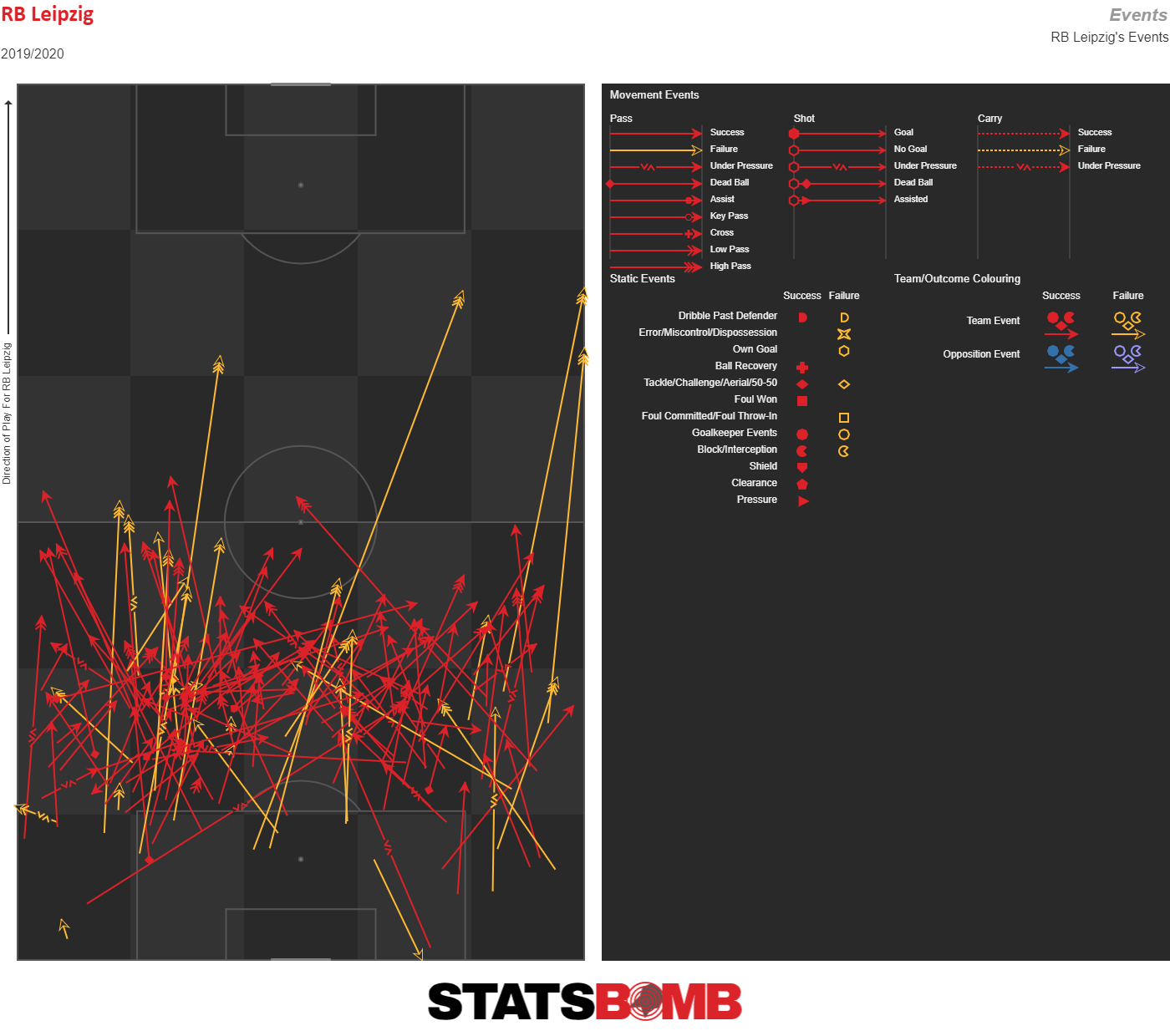

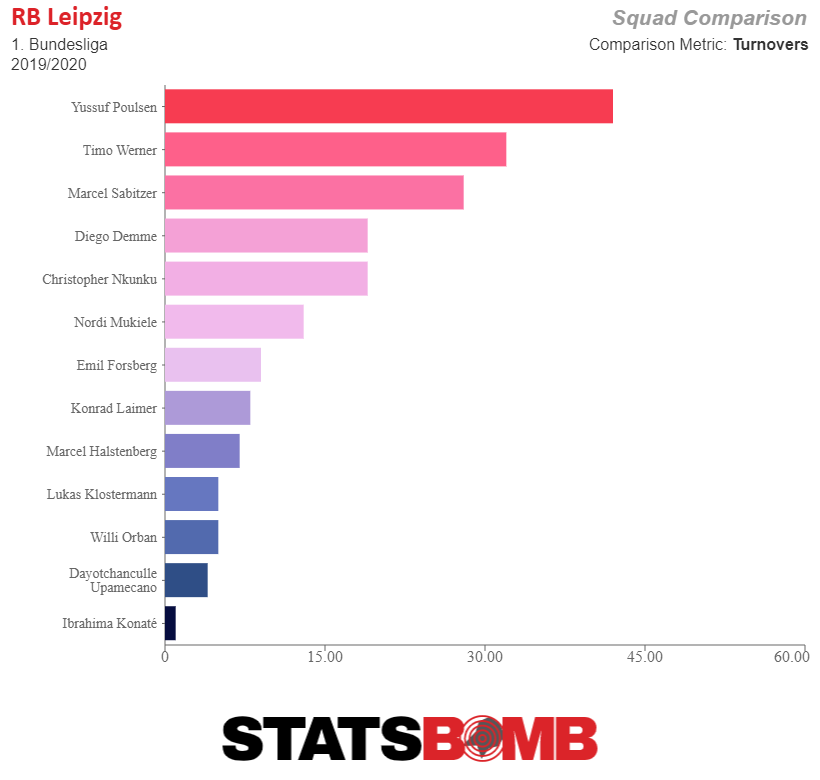

The side primarily uses the up-back-and-through strategy, which sees a forward player receive with their back to goal, only to lay it off to the goal-facing player deep of them, who will then launch it further forwards to a runner beyond the initial receiver. In their games against Union and Lyon, in particular, Leipzig attempted to do this by having the centre backs play it into Marcel Sabitzer’s feet, where the near-sided holding midfielder would – and in the case of the Union game, shift his position wider to be in line with the Austrian – receive goal-facing before they could then feed Lukas Klostermann’s runs beyond them.

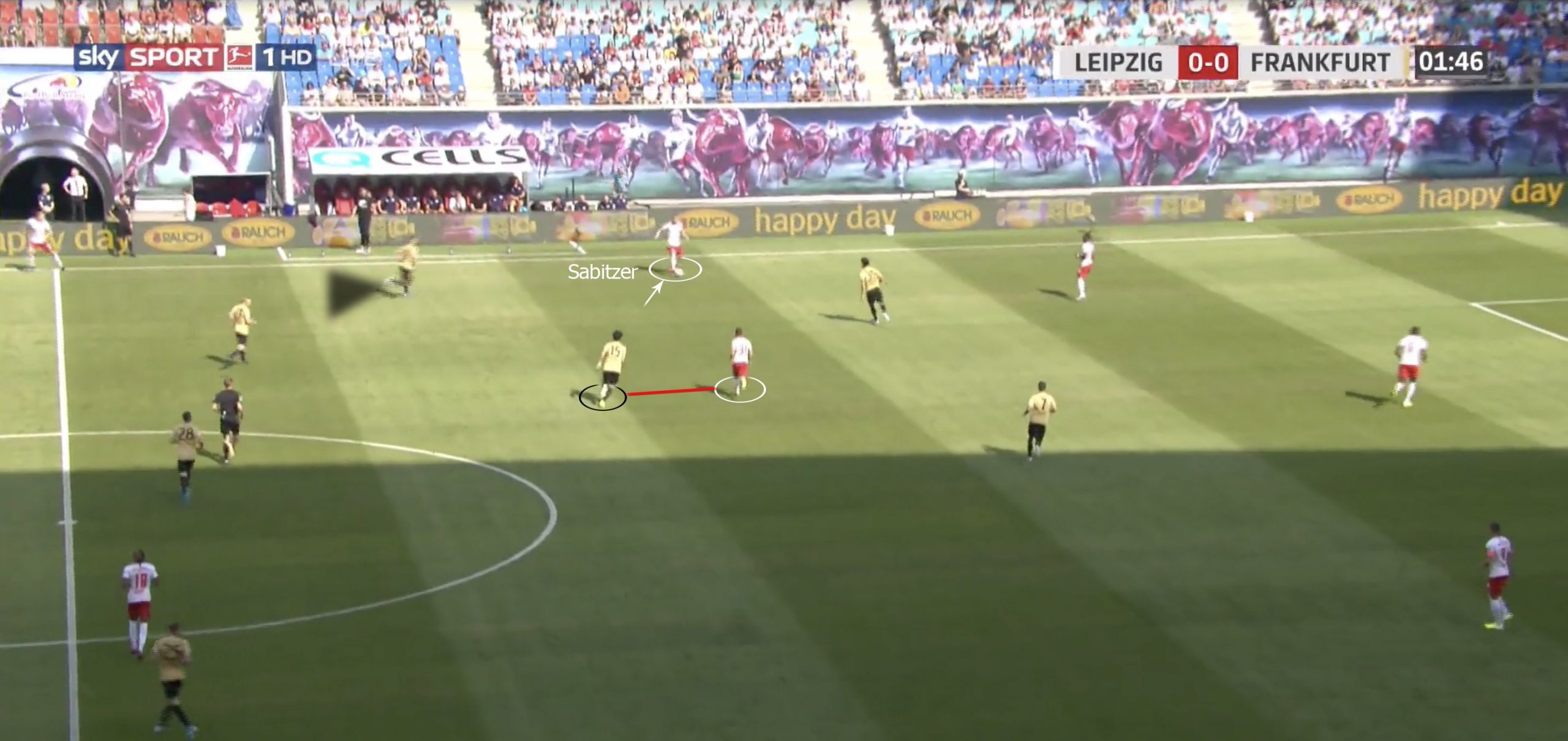

The side primarily uses the up-back-and-through strategy, which sees a forward player receive with their back to goal, only to lay it off to the goal-facing player deep of them, who will then launch it further forwards to a runner beyond the initial receiver. In their games against Union and Lyon, in particular, Leipzig attempted to do this by having the centre backs play it into Marcel Sabitzer’s feet, where the near-sided holding midfielder would – and in the case of the Union game, shift his position wider to be in line with the Austrian – receive goal-facing before they could then feed Lukas Klostermann’s runs beyond them.  Where Leipzig have struggled altogether in buildup has been in the two aforementioned games, against Frankfurt and Werder Bremen, where they fielded 3-5-1-1 setups in attack. The offensive shape is often a consequence of how Nagelsmann wishes to defend against opponents, which is, particularly at this early stage, potentially limiting given how unfamiliar the attackers are playing in certain systems. In the former, the main tactic was to have the near-sided wide forward move out to the wing to receive free of pressure, but when they did, they had no option to play into next. Here, Sabitzer drops wide, free of any marker, but has no options once he receives the ball there.

Where Leipzig have struggled altogether in buildup has been in the two aforementioned games, against Frankfurt and Werder Bremen, where they fielded 3-5-1-1 setups in attack. The offensive shape is often a consequence of how Nagelsmann wishes to defend against opponents, which is, particularly at this early stage, potentially limiting given how unfamiliar the attackers are playing in certain systems. In the former, the main tactic was to have the near-sided wide forward move out to the wing to receive free of pressure, but when they did, they had no option to play into next. Here, Sabitzer drops wide, free of any marker, but has no options once he receives the ball there.

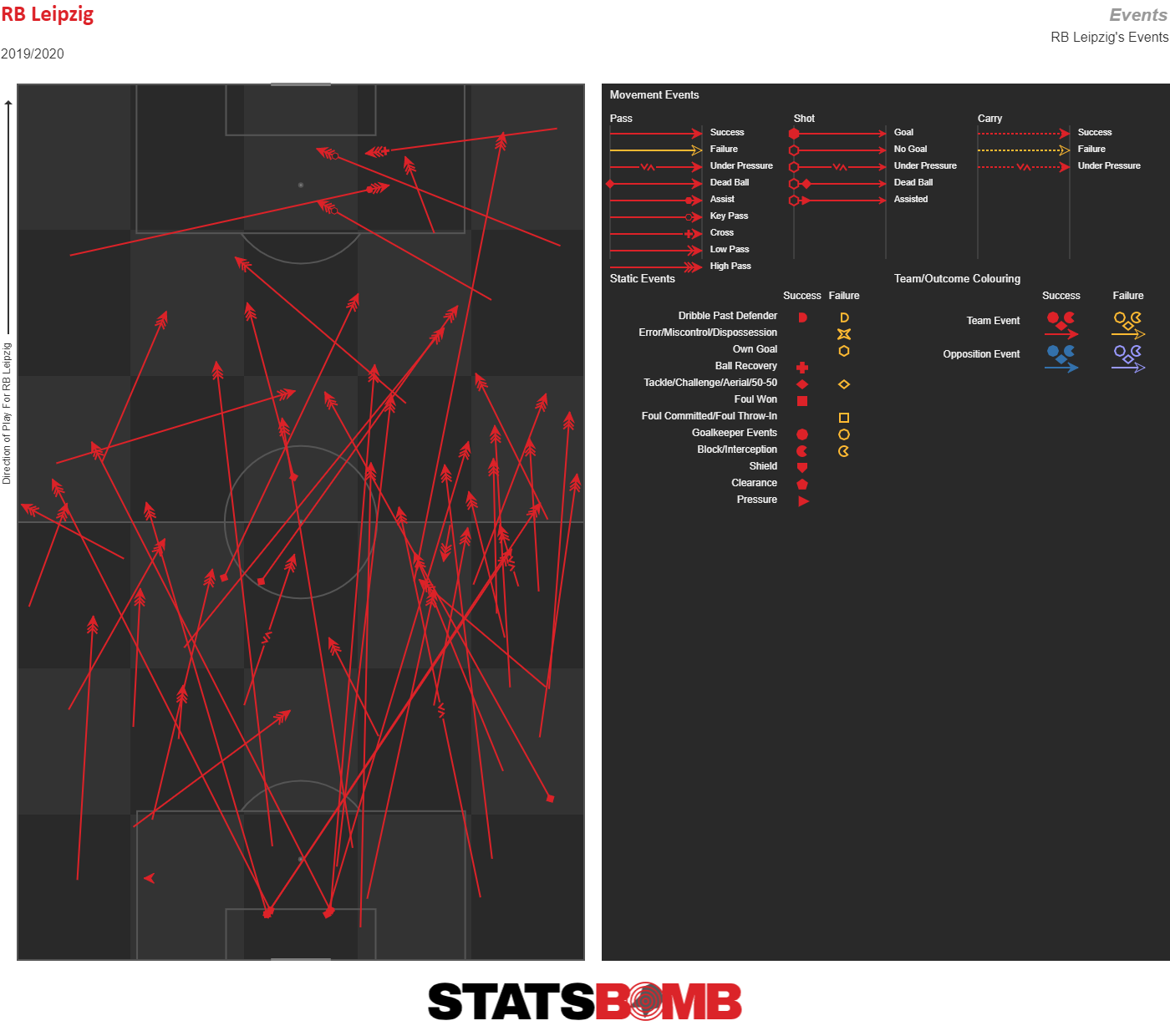

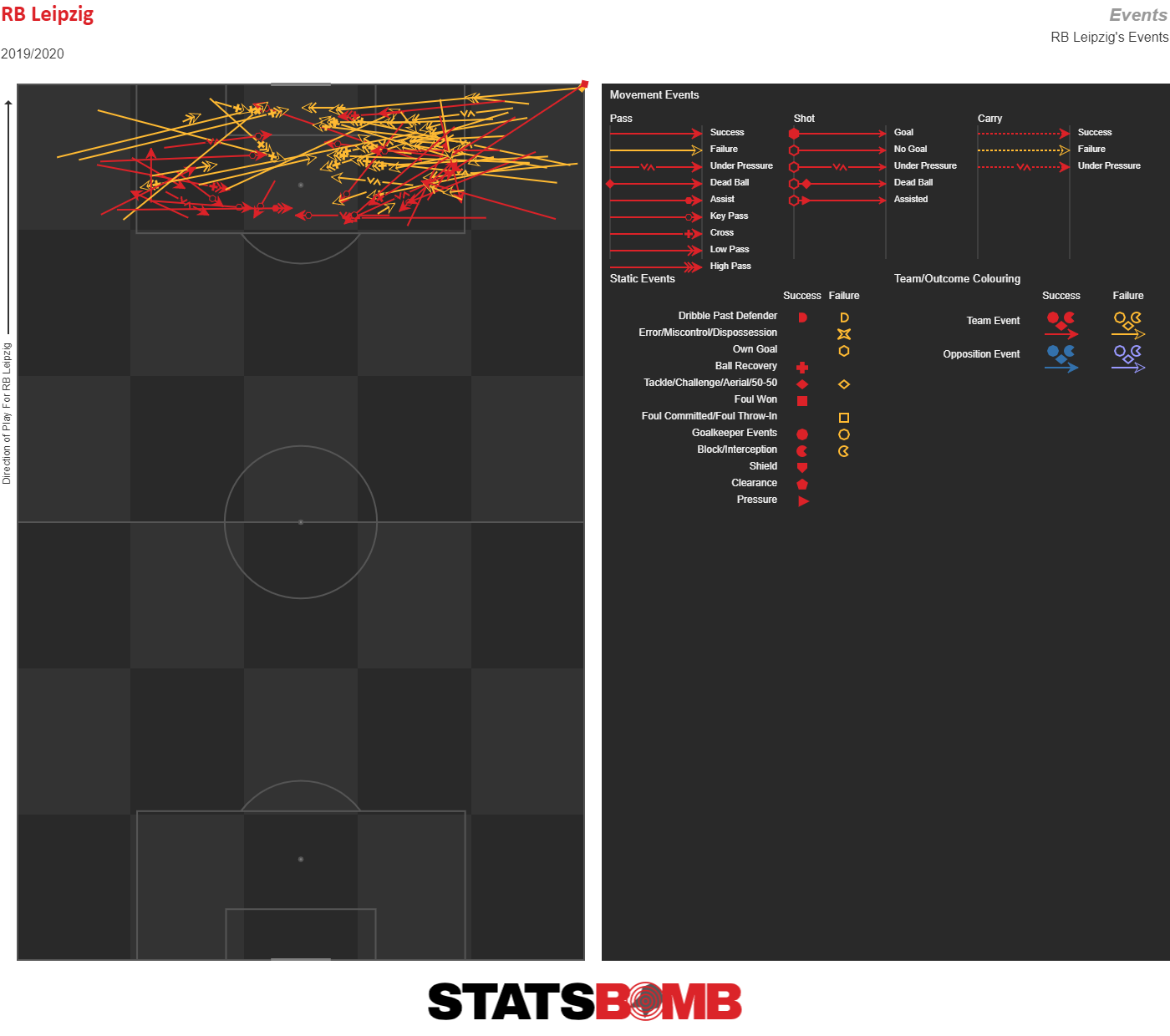

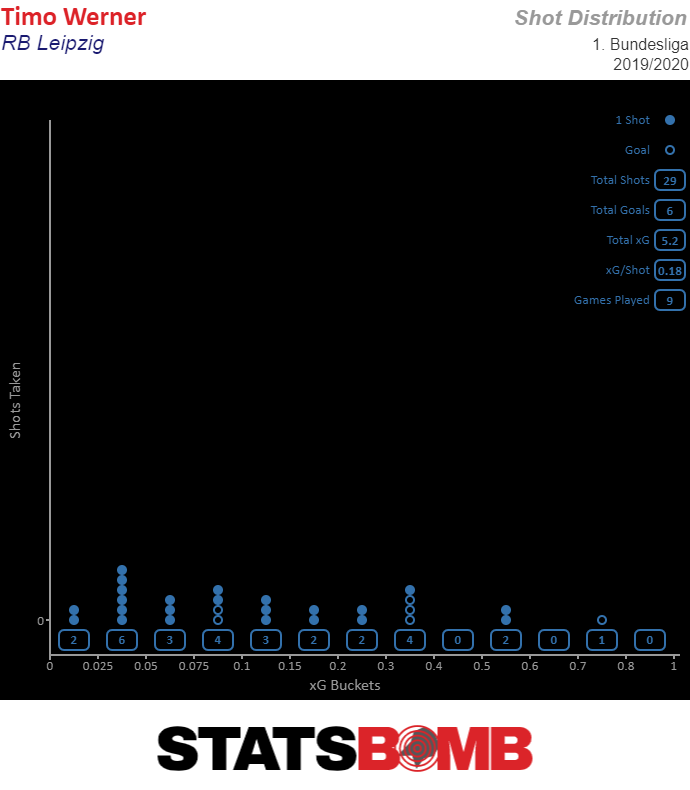

Typically, you’ll see Werner occupy positions either wide of or inside the near-sided fullback since these aerial balls are directed towards either halfspace, with his position pinning open space for Poulsen to challenge in. Deep of Werner are Sabitzer and/or Forsberg either side of the Dane, with the holding midfielder(s) pushed up to form a diamond around him, meaning that any balls coming back can be played forward into runners first-time.

Typically, you’ll see Werner occupy positions either wide of or inside the near-sided fullback since these aerial balls are directed towards either halfspace, with his position pinning open space for Poulsen to challenge in. Deep of Werner are Sabitzer and/or Forsberg either side of the Dane, with the holding midfielder(s) pushed up to form a diamond around him, meaning that any balls coming back can be played forward into runners first-time.  Clearly, though, their best chances, as you’d expect, come through quick transitions. The main way in which they’ve looked to escape pressure and set off attacks is based around the same up-back-and-through strategy they used in settled possession. This frequently involves Poulsen being readily available to receive the ball just ahead of the midfield line, where he can then lay it off to the various runners joining the attack, or simply back to the teammate who played it his way, as they will undoubtedly have more space to operate in after the exchange. Then, further ahead, you have Werner, particularly down the left side, moving as wide as possible to be both a short option and to be an attacker who can run from out-to-in.

Clearly, though, their best chances, as you’d expect, come through quick transitions. The main way in which they’ve looked to escape pressure and set off attacks is based around the same up-back-and-through strategy they used in settled possession. This frequently involves Poulsen being readily available to receive the ball just ahead of the midfield line, where he can then lay it off to the various runners joining the attack, or simply back to the teammate who played it his way, as they will undoubtedly have more space to operate in after the exchange. Then, further ahead, you have Werner, particularly down the left side, moving as wide as possible to be both a short option and to be an attacker who can run from out-to-in.  However, when you’re looking ahead and debating whether the current profiles can do enough to last the whole season, the one qualm might be the depth offered by Matheus Cunha, who pales in comparison to the balance Poulsen offer, but, statistically at least, you have four central attackers who are so experienced with this club and all have outstanding output so far, both in terms of creating and getting on the end of chances. When looking ahead, the sky really is the limit for this side, especially under the most talented young coach in the World, whose ceiling is yet to be established. ~ Stay tuned for part two, which will look at Leipzig’s pressing and defending.

However, when you’re looking ahead and debating whether the current profiles can do enough to last the whole season, the one qualm might be the depth offered by Matheus Cunha, who pales in comparison to the balance Poulsen offer, but, statistically at least, you have four central attackers who are so experienced with this club and all have outstanding output so far, both in terms of creating and getting on the end of chances. When looking ahead, the sky really is the limit for this side, especially under the most talented young coach in the World, whose ceiling is yet to be established. ~ Stay tuned for part two, which will look at Leipzig’s pressing and defending.

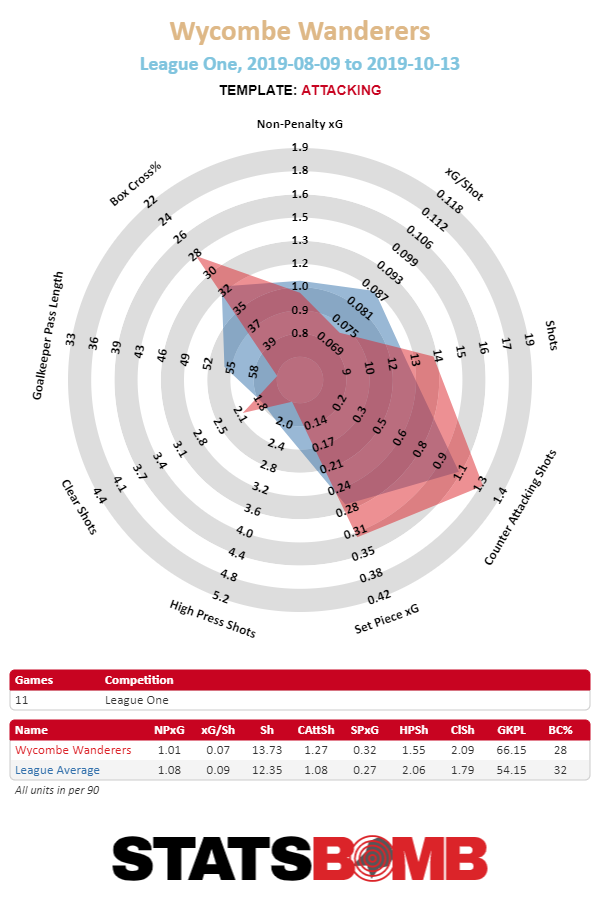

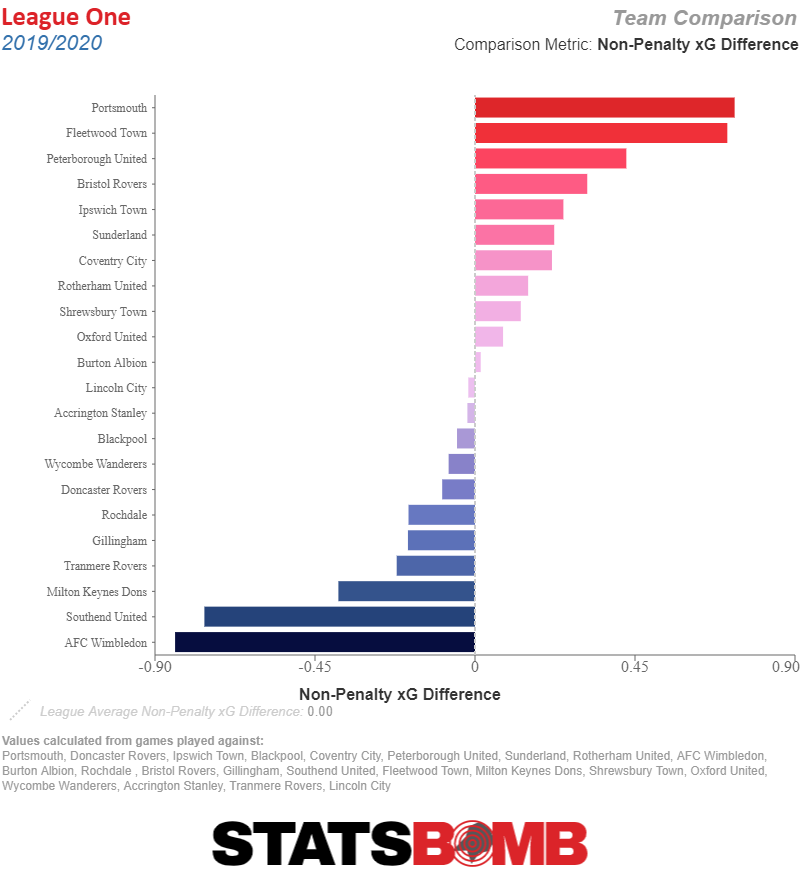

Their underlying numbers may not be as strong as their results but it’s important to note that they’ve been

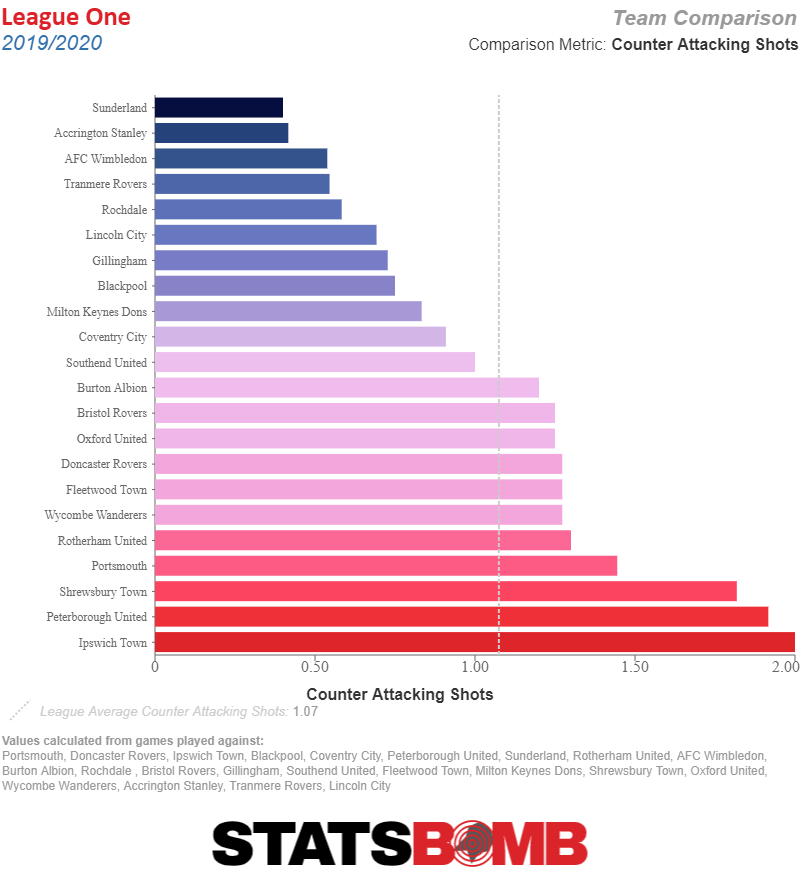

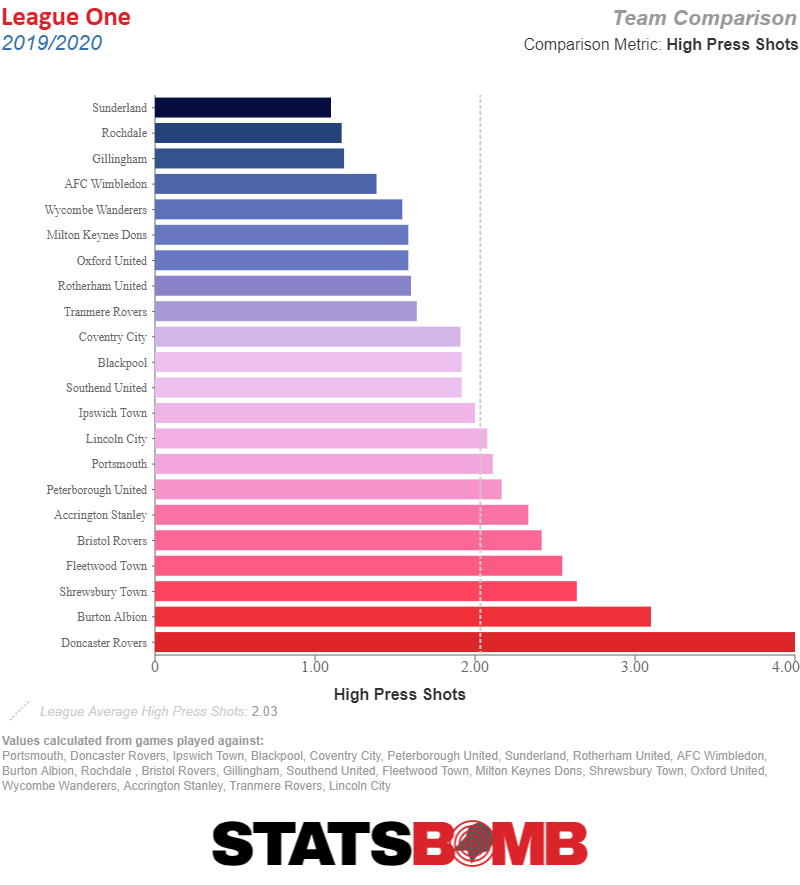

Their underlying numbers may not be as strong as their results but it’s important to note that they’ve been  If you’re not going to counter attack as a team, perhaps you might try other ways to unsettle the opposition and create decent opportunities for your side – winning the ball high up the pitch and looking to get shots off before the opponent could set themselves again maybe? Not Sunderland, they’re bottom for High Press shots too (shots generated within 5 seconds of a defensive action in the opposition half).

If you’re not going to counter attack as a team, perhaps you might try other ways to unsettle the opposition and create decent opportunities for your side – winning the ball high up the pitch and looking to get shots off before the opponent could set themselves again maybe? Not Sunderland, they’re bottom for High Press shots too (shots generated within 5 seconds of a defensive action in the opposition half).  Whilst the attack was failing, a rock solid defence wasn’t bailing them out either with the team yet to keep a clean sheet this campaign. There’s plenty to improve on for the next incumbent of the Sunderland hot seat.

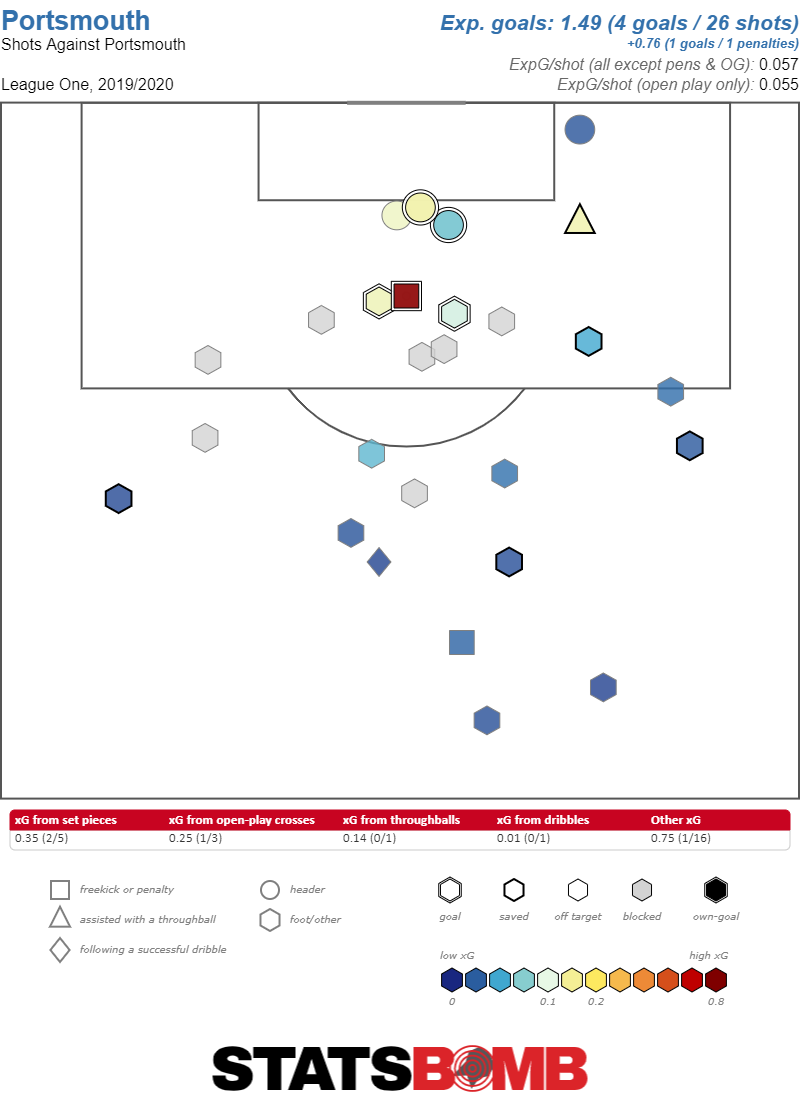

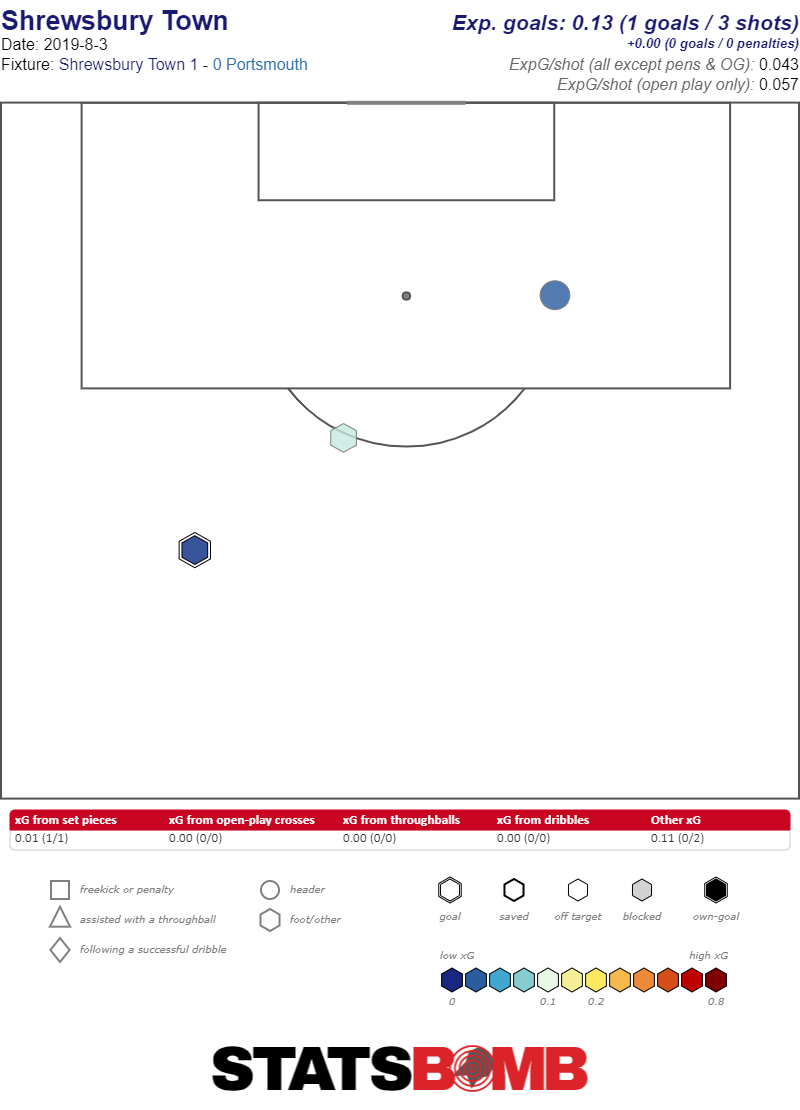

Whilst the attack was failing, a rock solid defence wasn’t bailing them out either with the team yet to keep a clean sheet this campaign. There’s plenty to improve on for the next incumbent of the Sunderland hot seat.  It’s not only when Pompey are ahead that their opponents have been finishing their chances well though. Burton Albion turned up at Fratton Park in mid-September and promptly scored their first two shots of the game, one of which was heavily deflected, to put Portsmouth 2-0 down and on the back foot six minutes in. Likewise Shrewsbury on the opening day turned what was a very robust defensive performance from Portsmouth (they conceded 3 shots all game) into an uninspiring defeat thanks to a 30 yard Ryan Giles rocket.

It’s not only when Pompey are ahead that their opponents have been finishing their chances well though. Burton Albion turned up at Fratton Park in mid-September and promptly scored their first two shots of the game, one of which was heavily deflected, to put Portsmouth 2-0 down and on the back foot six minutes in. Likewise Shrewsbury on the opening day turned what was a very robust defensive performance from Portsmouth (they conceded 3 shots all game) into an uninspiring defeat thanks to a 30 yard Ryan Giles rocket.  That’s not to say the story is solely one of hard luck. Arguments that Jackett is too wedded to his sit-deep-and-counter system that can leave them inflexible at times and unable to adapt to the game situation they find themselves in are definitely fair. If the opposition aren’t going to be drawn out, as will often be the case particularly in Pompey’s home games, then they tend to struggle to create enough and the amount of rotation that’s been made in the shape and personnel of Pompey’s frontline this season suggests that Jackett isn’t exactly pleased with what he’s seeing either. It’s true to say that there isn’t too much wrong with what Portsmouth are doing so far, but it’s also true that certain things do need tuning up if they’re to push on towards the top end. Being a full 14 points behind Ipswich likely means the title is already beyond their reach but Pompey could achieve their promotion aims yet with the aid of a few tweaks to the system. Jackett remaining in charge long enough to implement them though will depend on a pretty immediate uptick in short term results.

That’s not to say the story is solely one of hard luck. Arguments that Jackett is too wedded to his sit-deep-and-counter system that can leave them inflexible at times and unable to adapt to the game situation they find themselves in are definitely fair. If the opposition aren’t going to be drawn out, as will often be the case particularly in Pompey’s home games, then they tend to struggle to create enough and the amount of rotation that’s been made in the shape and personnel of Pompey’s frontline this season suggests that Jackett isn’t exactly pleased with what he’s seeing either. It’s true to say that there isn’t too much wrong with what Portsmouth are doing so far, but it’s also true that certain things do need tuning up if they’re to push on towards the top end. Being a full 14 points behind Ipswich likely means the title is already beyond their reach but Pompey could achieve their promotion aims yet with the aid of a few tweaks to the system. Jackett remaining in charge long enough to implement them though will depend on a pretty immediate uptick in short term results.

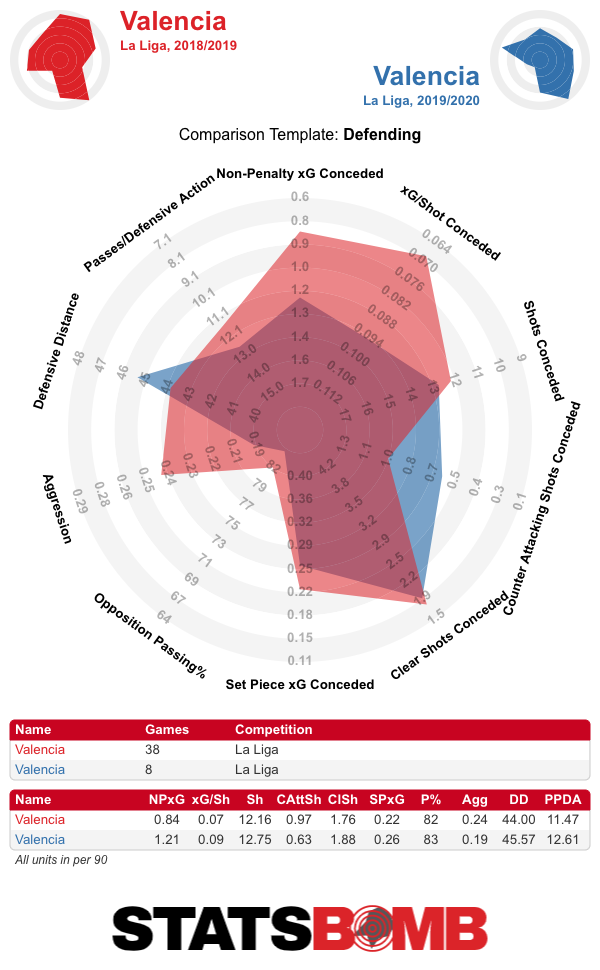

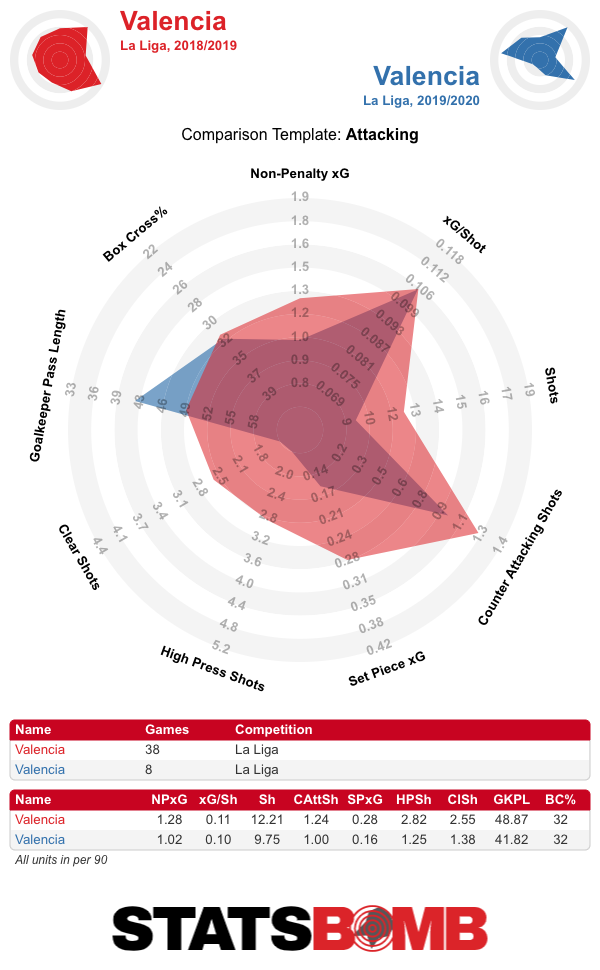

Celades wasn’t dealt the easiest of hands replacing a coach that many of the players were disappointed to see depart, and it will take some time for him to implement some of his own ideas in what is his first senior head coach role. He has only been in charge for five league matches, one of which was a 5-2 defeat away to Barcelona, so it’s not a fair sample, but his short tenure to date has nevertheless been the second worst five-match stretch Valencia have had in terms of expected goal (xG) difference since the start of the 2017-18 season. The worst comprised of his first three matches tacked onto Marcelino’s last two. They have been the worse side in xG terms in four of his first five fixtures -- against Barcelona, Leganés, Getafe and Alavés. Valencia sold none of their key players over the summer and arguably have a slightly stronger squad than they did last season, especially with Maxi Gómez getting off to a good start in front of goal following his move from Celta Vigo. But across the eight matches of the campaign to date, they’ve been worse at both a top-line and underlying level.

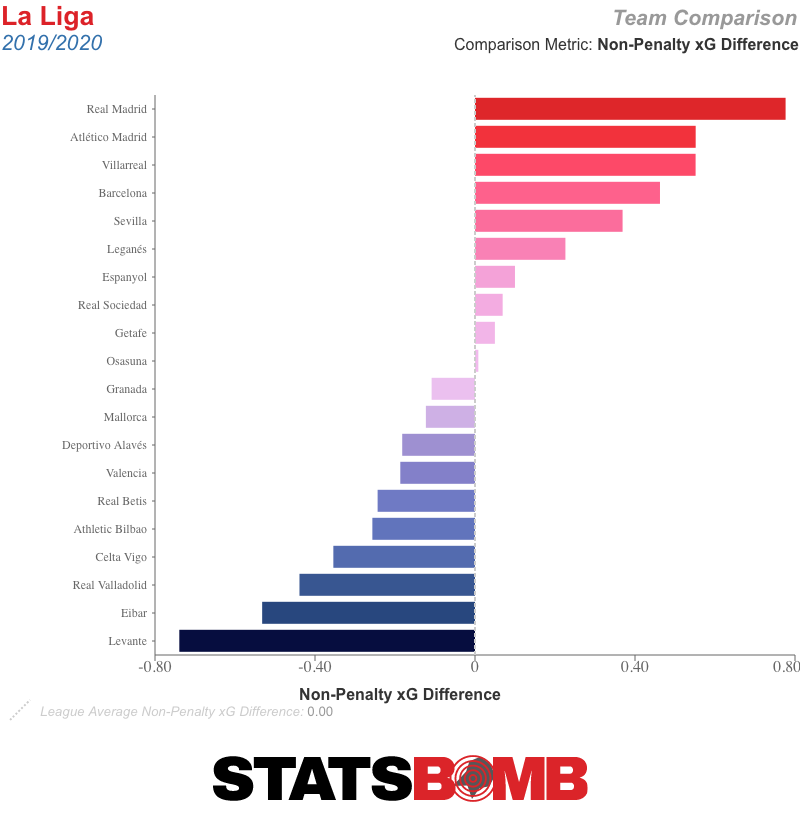

Celades wasn’t dealt the easiest of hands replacing a coach that many of the players were disappointed to see depart, and it will take some time for him to implement some of his own ideas in what is his first senior head coach role. He has only been in charge for five league matches, one of which was a 5-2 defeat away to Barcelona, so it’s not a fair sample, but his short tenure to date has nevertheless been the second worst five-match stretch Valencia have had in terms of expected goal (xG) difference since the start of the 2017-18 season. The worst comprised of his first three matches tacked onto Marcelino’s last two. They have been the worse side in xG terms in four of his first five fixtures -- against Barcelona, Leganés, Getafe and Alavés. Valencia sold none of their key players over the summer and arguably have a slightly stronger squad than they did last season, especially with Maxi Gómez getting off to a good start in front of goal following his move from Celta Vigo. But across the eight matches of the campaign to date, they’ve been worse at both a top-line and underlying level.  The fact that at least in its early stages, there seems to be little to separate a fairly large chunk of the league this season plays to Valencia’s favour, if they can swiftly find a way to improve performances and results. Consecutive wins away to Athletic Club and at home to Alavés have provided a bit of cautious optimism, but the trip to Atlético could easily temper that. Valencia last defeated them in 2014 and haven’t won away there since 2011. “Against Atlético, we will really see where we stand,” fullback José Gayá said this week. Atlético are certainly as good a barometer as any. Of all the teams who have taken part in La Liga in all of the last five seasons, only Barcelona have had a lower percentage variance between their best and worst points tallies than Diego Simeone’s side. They have been a picture of consistency, regularly converting the league’s third-biggest budget into top-three finishes. Players have come and gone, but Simeone and his staff have maintained a steady level of performance. Until very recently (

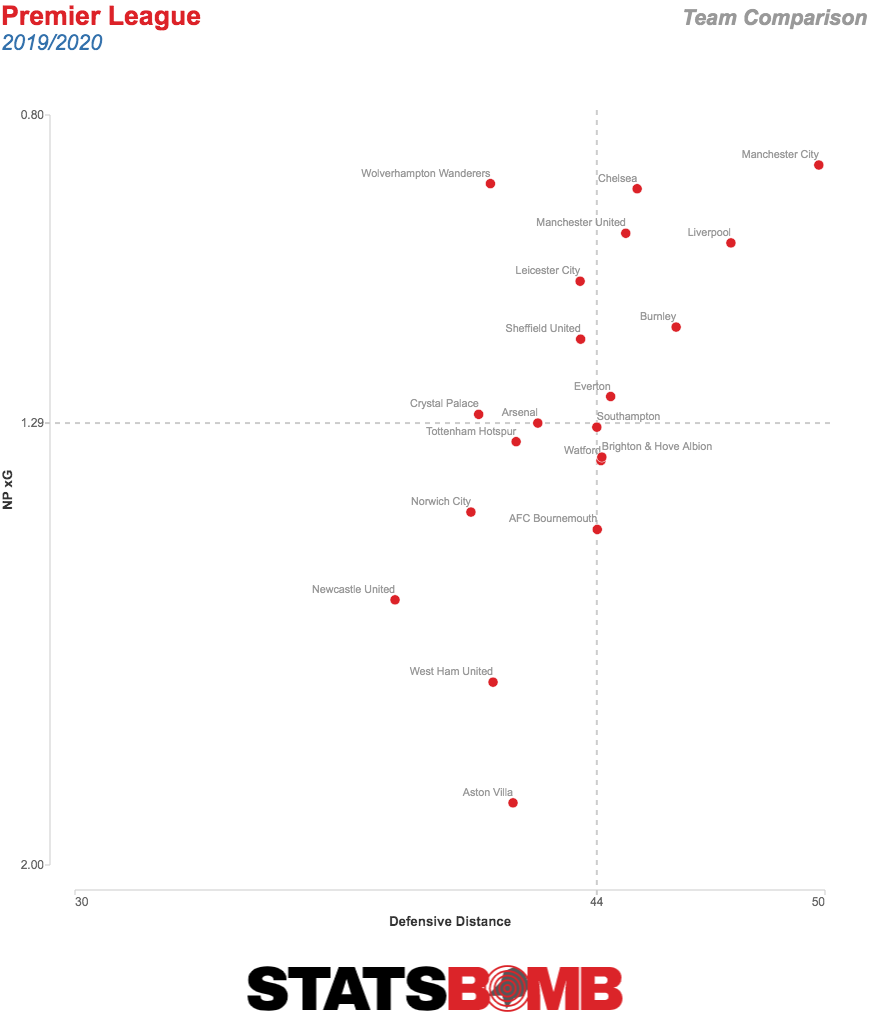

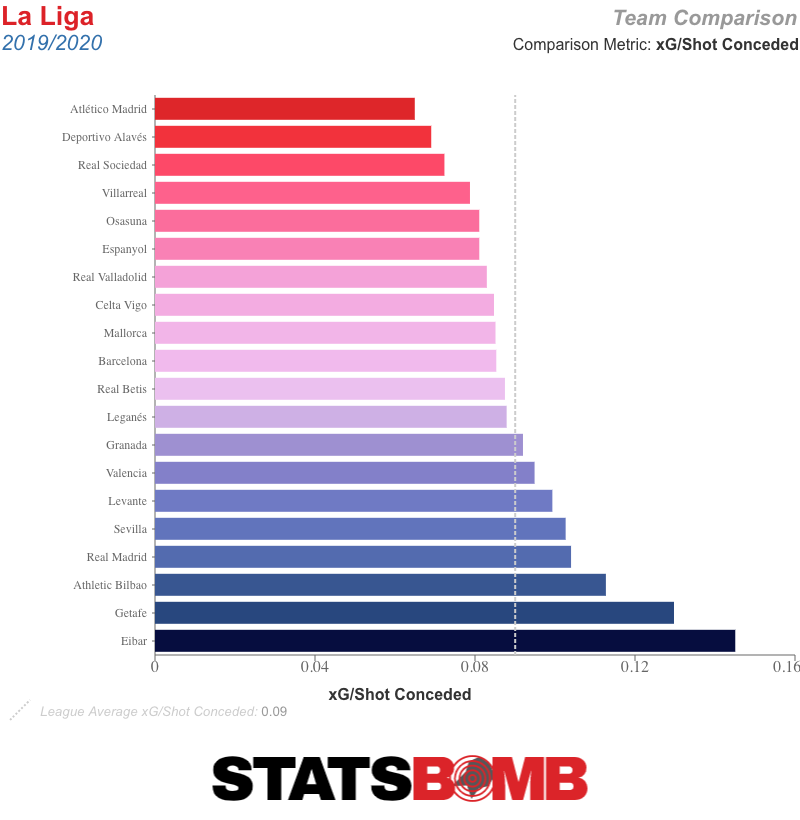

The fact that at least in its early stages, there seems to be little to separate a fairly large chunk of the league this season plays to Valencia’s favour, if they can swiftly find a way to improve performances and results. Consecutive wins away to Athletic Club and at home to Alavés have provided a bit of cautious optimism, but the trip to Atlético could easily temper that. Valencia last defeated them in 2014 and haven’t won away there since 2011. “Against Atlético, we will really see where we stand,” fullback José Gayá said this week. Atlético are certainly as good a barometer as any. Of all the teams who have taken part in La Liga in all of the last five seasons, only Barcelona have had a lower percentage variance between their best and worst points tallies than Diego Simeone’s side. They have been a picture of consistency, regularly converting the league’s third-biggest budget into top-three finishes. Players have come and gone, but Simeone and his staff have maintained a steady level of performance. Until very recently ( Simeone has really leaned hard on his defence so far. Atlético have kept clean sheets in seven of their 10 matches in league and Champions League play, including in each of the last five. Three of their last four league matches have ended 0-0. Their 0.52 xG conceded per match is comfortably the lowest mark in La Liga. Only three teams are conceding less shots, and no one is giving up such low-quality ones.

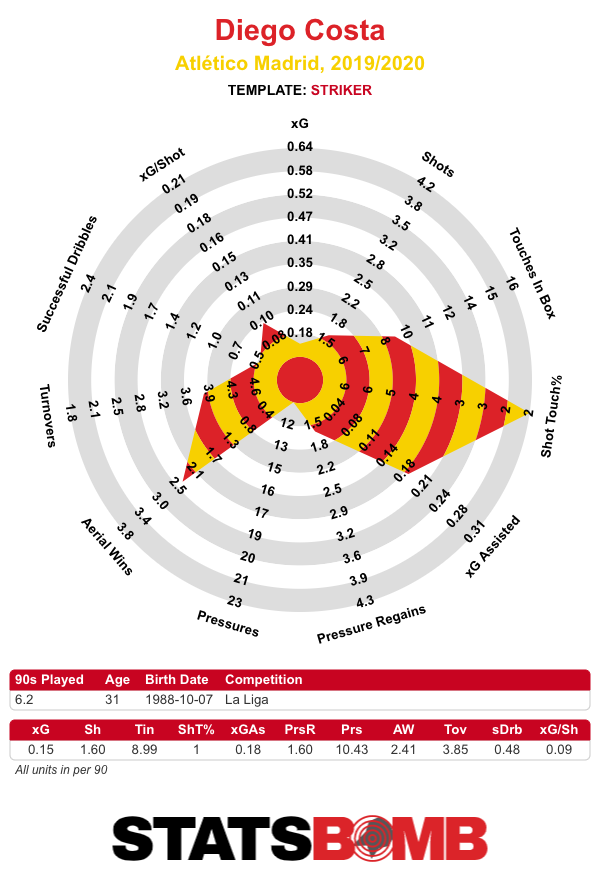

Simeone has really leaned hard on his defence so far. Atlético have kept clean sheets in seven of their 10 matches in league and Champions League play, including in each of the last five. Three of their last four league matches have ended 0-0. Their 0.52 xG conceded per match is comfortably the lowest mark in La Liga. Only three teams are conceding less shots, and no one is giving up such low-quality ones.  That is providing a stable base for Simeone’s experiments (including a midfield diamond with Thomas Lemar at its tip) as he reaches for a coherent attack. Antoine Griezmann was such an important cog in their previous set up that it was always going to take some time to work out an alternative. Atlético’s unsuccessful late-window attempts at signing Rodrigo from Valencia -- a relatively close stylistic match -- illustrated his lack of confidence that existing options would prove sufficient. So far, his side are doing enough to get by with a mix of average open play numbers and better than average set-piece output. Atlético’s supporters are likely to suffer through a fair number of low-scoring slogs this season (no other team’s matches have seen less goals so far; only those of two have seen less xG), but that might just be what is required to keep them in the realm of their usual points tally and so continue their run of top-three finishes through an eighth consecutive season. It is a bet on no one emerging from the pack below. Valencia were the most likely candidates before internecine squabbles intervened. Unless Sevilla, Real Sociedad or Villarreal show themselves to be genuine contenders over the next couple of months, it will probably prove quite a safe one.

That is providing a stable base for Simeone’s experiments (including a midfield diamond with Thomas Lemar at its tip) as he reaches for a coherent attack. Antoine Griezmann was such an important cog in their previous set up that it was always going to take some time to work out an alternative. Atlético’s unsuccessful late-window attempts at signing Rodrigo from Valencia -- a relatively close stylistic match -- illustrated his lack of confidence that existing options would prove sufficient. So far, his side are doing enough to get by with a mix of average open play numbers and better than average set-piece output. Atlético’s supporters are likely to suffer through a fair number of low-scoring slogs this season (no other team’s matches have seen less goals so far; only those of two have seen less xG), but that might just be what is required to keep them in the realm of their usual points tally and so continue their run of top-three finishes through an eighth consecutive season. It is a bet on no one emerging from the pack below. Valencia were the most likely candidates before internecine squabbles intervened. Unless Sevilla, Real Sociedad or Villarreal show themselves to be genuine contenders over the next couple of months, it will probably prove quite a safe one.  Care to venture a guess at La Liga’s most two-footed player so far this season? No, not him. Or him. Or him. Nope. It’s Tomás Pina of Alavés, with a near perfect 50/50 split between his left and right foot.

Care to venture a guess at La Liga’s most two-footed player so far this season? No, not him. Or him. Or him. Nope. It’s Tomás Pina of Alavés, with a near perfect 50/50 split between his left and right foot.

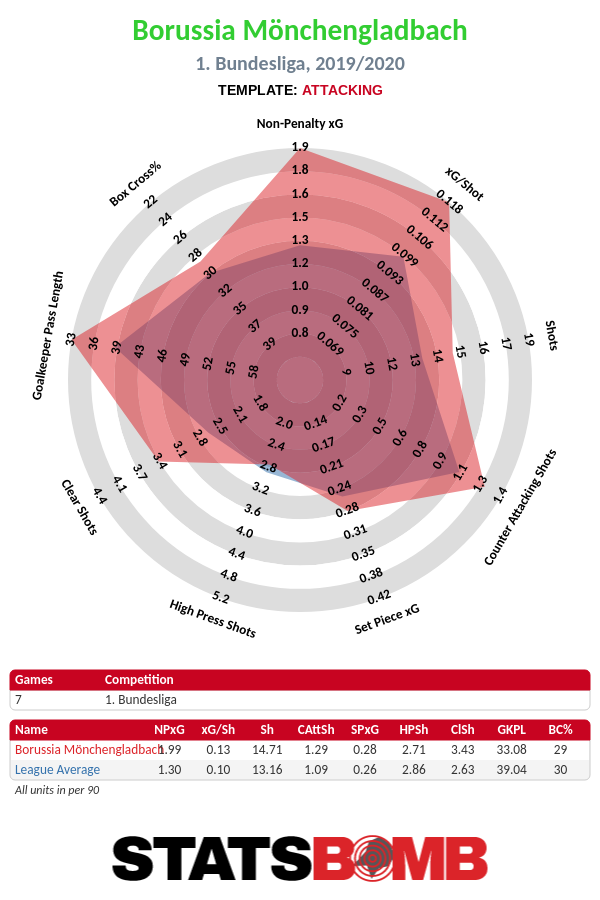

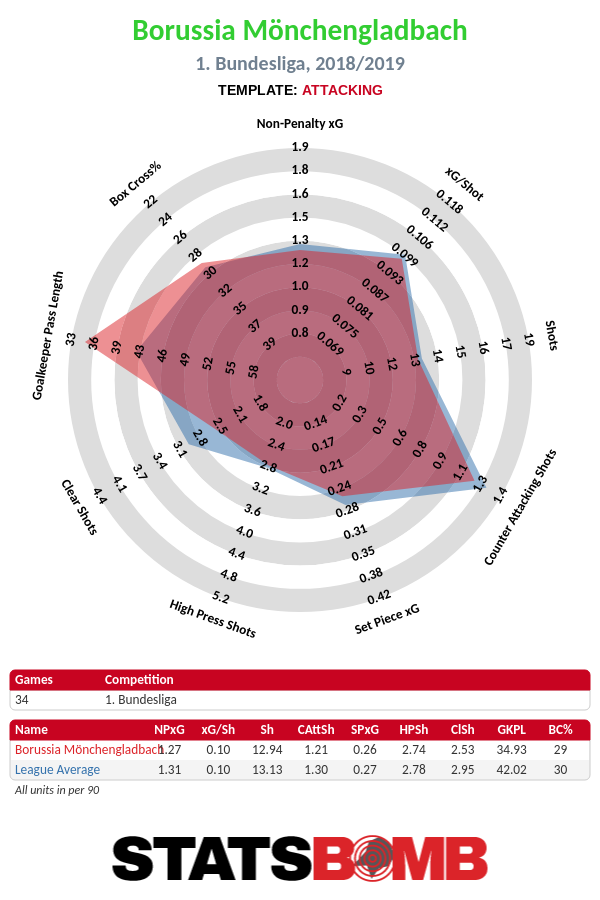

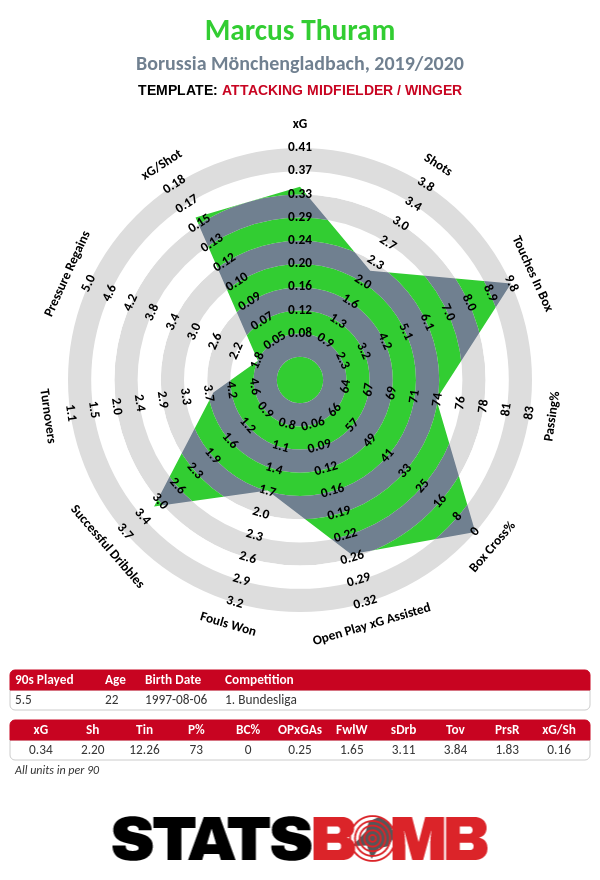

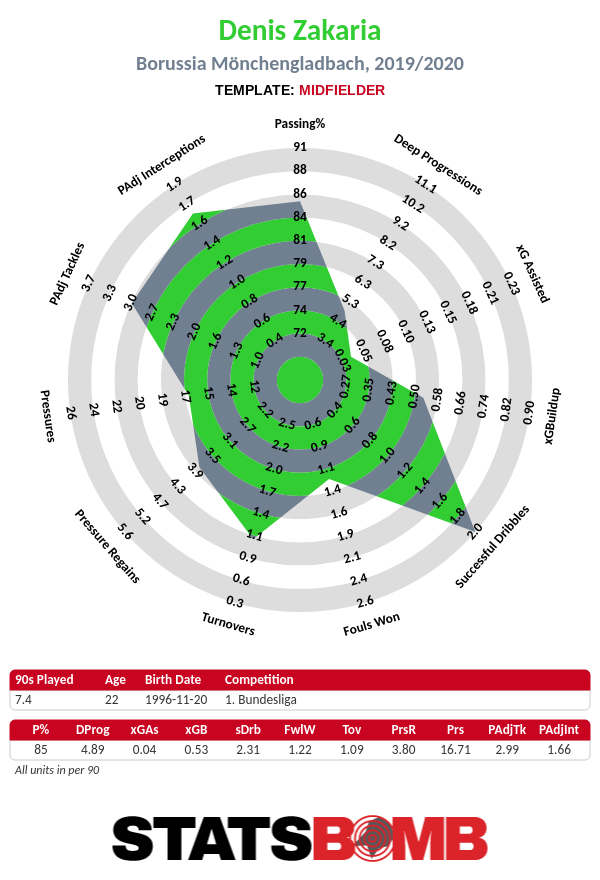

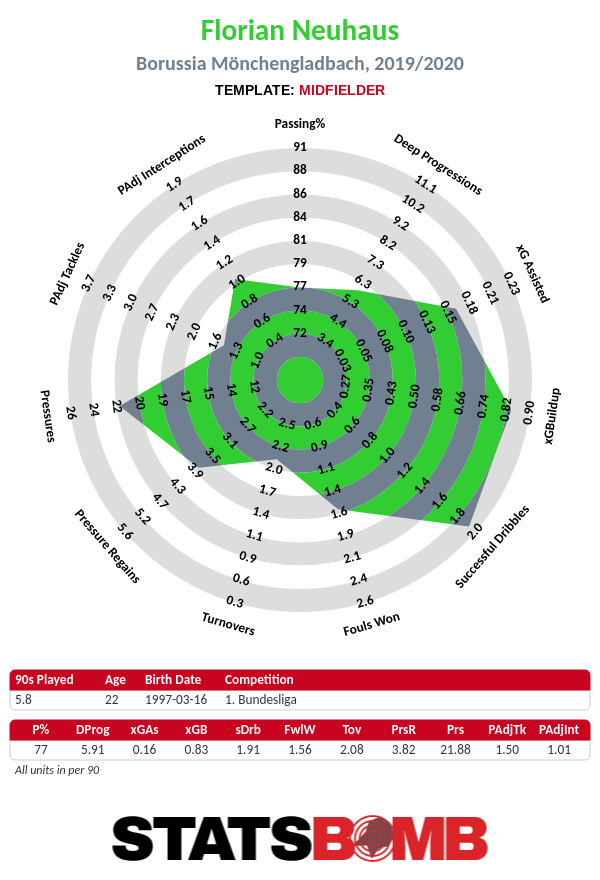

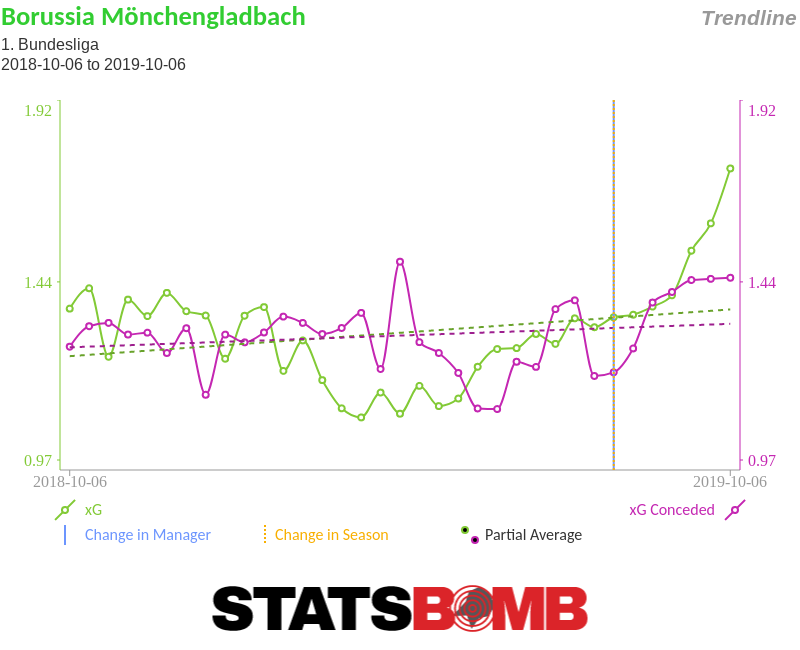

And whoo boy, Mönchengladbach can certainly play some fast-break ball at breakneck speed. Of the fifteen goals

And whoo boy, Mönchengladbach can certainly play some fast-break ball at breakneck speed. Of the fifteen goals  In the two box-to-box slots of the diamond, Rose had handed the keys to the two creatively talented youngsters of the squad, Neuhaus and the 22 year-old Slovakian László Bénes. The stylish allrounder Neuhaus (also 22) seems to be the prime candidate as a future record-sell for Mönchengladbach. He has the ball control, vision and positional smarts to excel in a multitude of midfield roles, and combines these skills with some very deft dribbling.

In the two box-to-box slots of the diamond, Rose had handed the keys to the two creatively talented youngsters of the squad, Neuhaus and the 22 year-old Slovakian László Bénes. The stylish allrounder Neuhaus (also 22) seems to be the prime candidate as a future record-sell for Mönchengladbach. He has the ball control, vision and positional smarts to excel in a multitude of midfield roles, and combines these skills with some very deft dribbling.

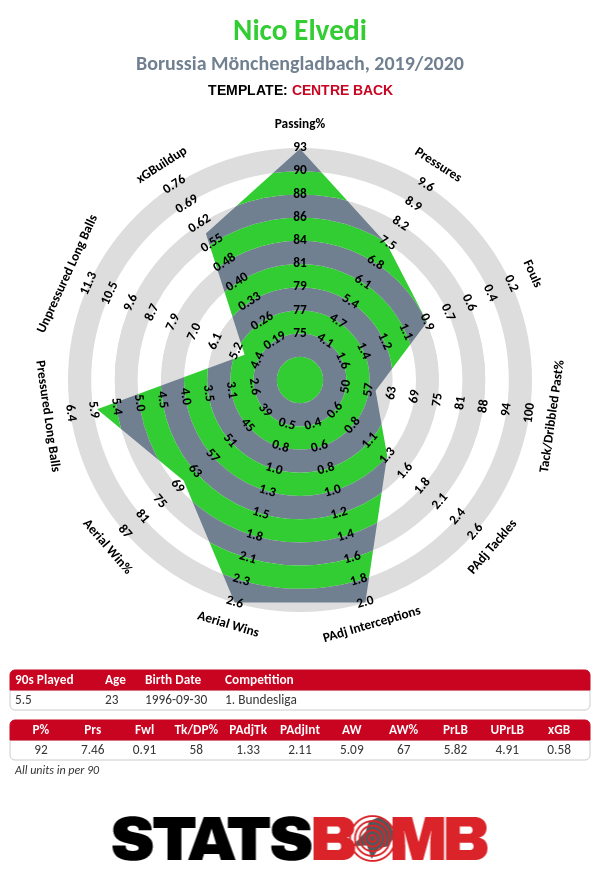

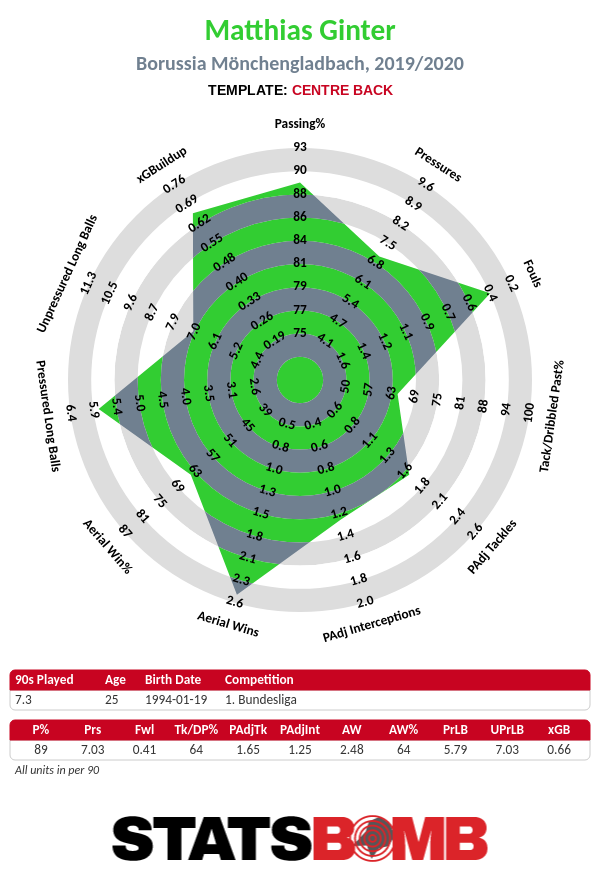

Neither Ginter nor Elvedi possess elite speed for central defenders for a top club in an elite competition, but they are both very good passers of the ball. Their swift and accurate ball movement in the early stages of Mönchengladbach’s possessions is a necessity with the current playing style.

Neither Ginter nor Elvedi possess elite speed for central defenders for a top club in an elite competition, but they are both very good passers of the ball. Their swift and accurate ball movement in the early stages of Mönchengladbach’s possessions is a necessity with the current playing style.

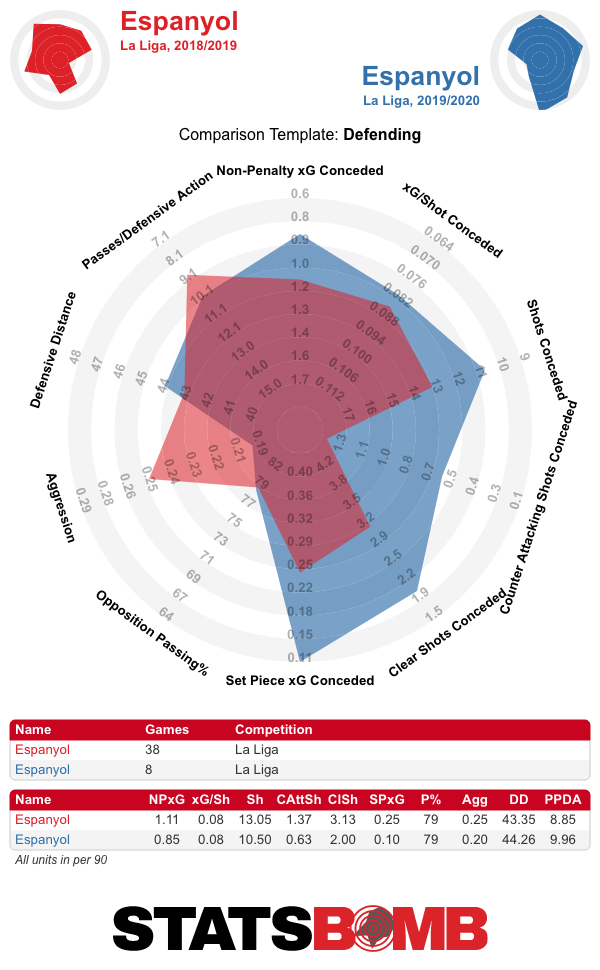

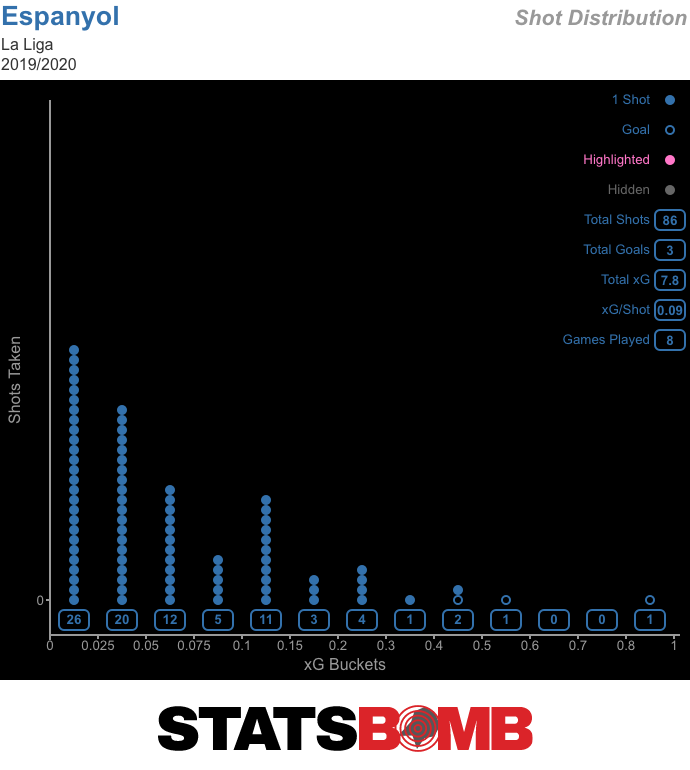

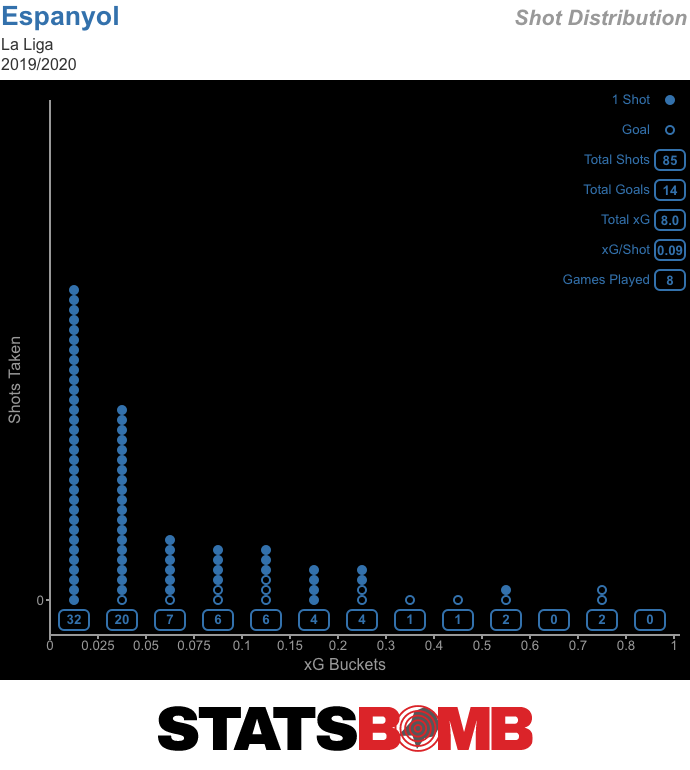

At the other end, opponents have likewise converted five of the six highest-quality chances Espanyol have conceded, but they have also scored seven times off shots in the five lowest-quality brackets -- all less than one-in-six opportunities:

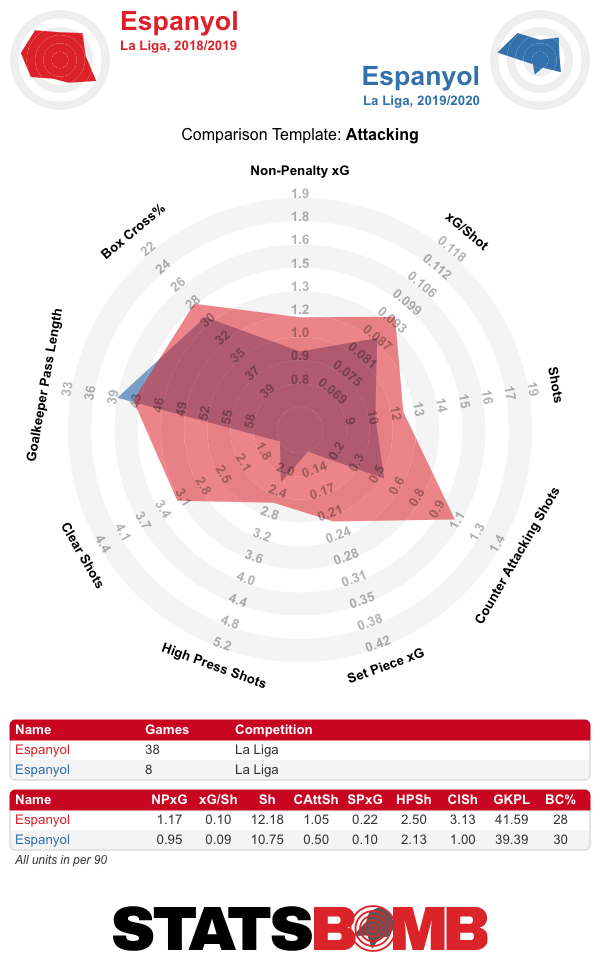

At the other end, opponents have likewise converted five of the six highest-quality chances Espanyol have conceded, but they have also scored seven times off shots in the five lowest-quality brackets -- all less than one-in-six opportunities:  Those are the kinds of things that tend to even out over time. Having successfully led the team through the Europa League qualifying rounds into the group stage, Gallego may feel that he deserved some more of that. It bears noting that the lowest any team with a positive xG difference has finished in La Liga in either of the last two seasons is 12th. Perhaps reality would eventually have caught up with the underlying numbers. That would be the generous reading. We are only eight matches into the campaign and so difficulty of schedule is still a prominent factor in team performance. Espanyol’s has been very mild to date, pitting them against two of the three promoted teams, two teams who narrowly avoided relegation last season, an Alavés side who have looked one of the weakest in La Liga so far, and none of last season’s top five. It is questionable whether their positive underlying numbers would have held through the tougher fixtures now to come. In whatever terms you look at it, Espanyol have been dreadful in the first halves of their matches to date, being comfortably outshot, outscored and out-xG’d. They’ve only taken four shots on target, to 17 against, and just one from inside the area, to 12 against. Regardless of the degree to which you are later able to create chances (Espanyol’s second-half balance is 5.94 xG to 2.13 xG conceded), consistently putting yourself at that sort of disadvantage is a recipe for failure. And then there are the subjective impressions. Gallego’s Espanyol didn’t seem to have a clear idea of how to progress the ball upfield and were heavily reliant on individual inspiration to create opportunities in attack. Summer signing Matías Vargas, the most expensive in the club’s history, took on the large majority of the creative burden (he currently leads the team in dribbles, throughballs, xG assisted and open play passes into the box). The lack of systemised ball progression surely contributed to three giveaways in defensive territory that led directly to opposition goals. In that context, and with some interesting coaches with experience and previous success freely available to take over, it is fairly easy to make a case for Espanyol’s decision to replace Gallego.

Those are the kinds of things that tend to even out over time. Having successfully led the team through the Europa League qualifying rounds into the group stage, Gallego may feel that he deserved some more of that. It bears noting that the lowest any team with a positive xG difference has finished in La Liga in either of the last two seasons is 12th. Perhaps reality would eventually have caught up with the underlying numbers. That would be the generous reading. We are only eight matches into the campaign and so difficulty of schedule is still a prominent factor in team performance. Espanyol’s has been very mild to date, pitting them against two of the three promoted teams, two teams who narrowly avoided relegation last season, an Alavés side who have looked one of the weakest in La Liga so far, and none of last season’s top five. It is questionable whether their positive underlying numbers would have held through the tougher fixtures now to come. In whatever terms you look at it, Espanyol have been dreadful in the first halves of their matches to date, being comfortably outshot, outscored and out-xG’d. They’ve only taken four shots on target, to 17 against, and just one from inside the area, to 12 against. Regardless of the degree to which you are later able to create chances (Espanyol’s second-half balance is 5.94 xG to 2.13 xG conceded), consistently putting yourself at that sort of disadvantage is a recipe for failure. And then there are the subjective impressions. Gallego’s Espanyol didn’t seem to have a clear idea of how to progress the ball upfield and were heavily reliant on individual inspiration to create opportunities in attack. Summer signing Matías Vargas, the most expensive in the club’s history, took on the large majority of the creative burden (he currently leads the team in dribbles, throughballs, xG assisted and open play passes into the box). The lack of systemised ball progression surely contributed to three giveaways in defensive territory that led directly to opposition goals. In that context, and with some interesting coaches with experience and previous success freely available to take over, it is fairly easy to make a case for Espanyol’s decision to replace Gallego.  Espanyol provide him with the opportunity to prove that was a mistake. “It is a club that is improving, that wants to progress,” he said

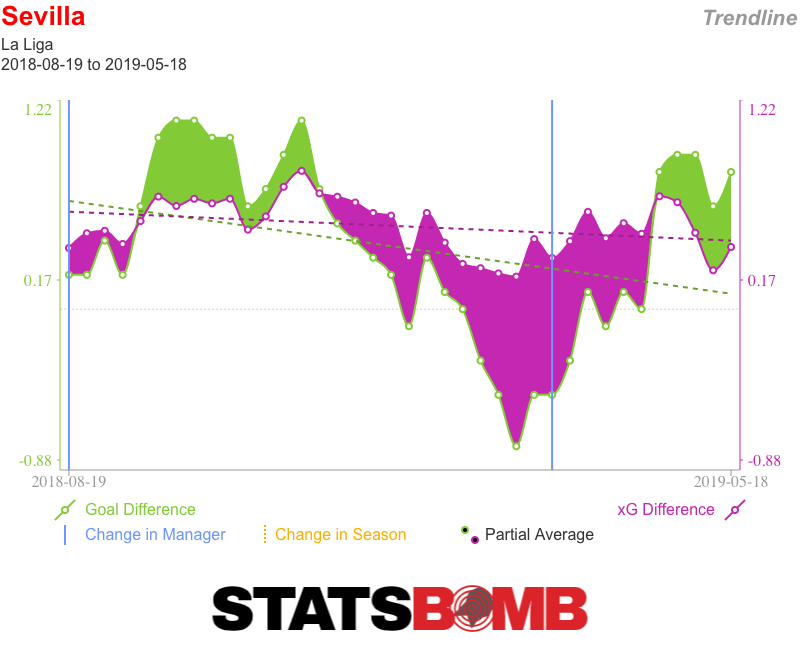

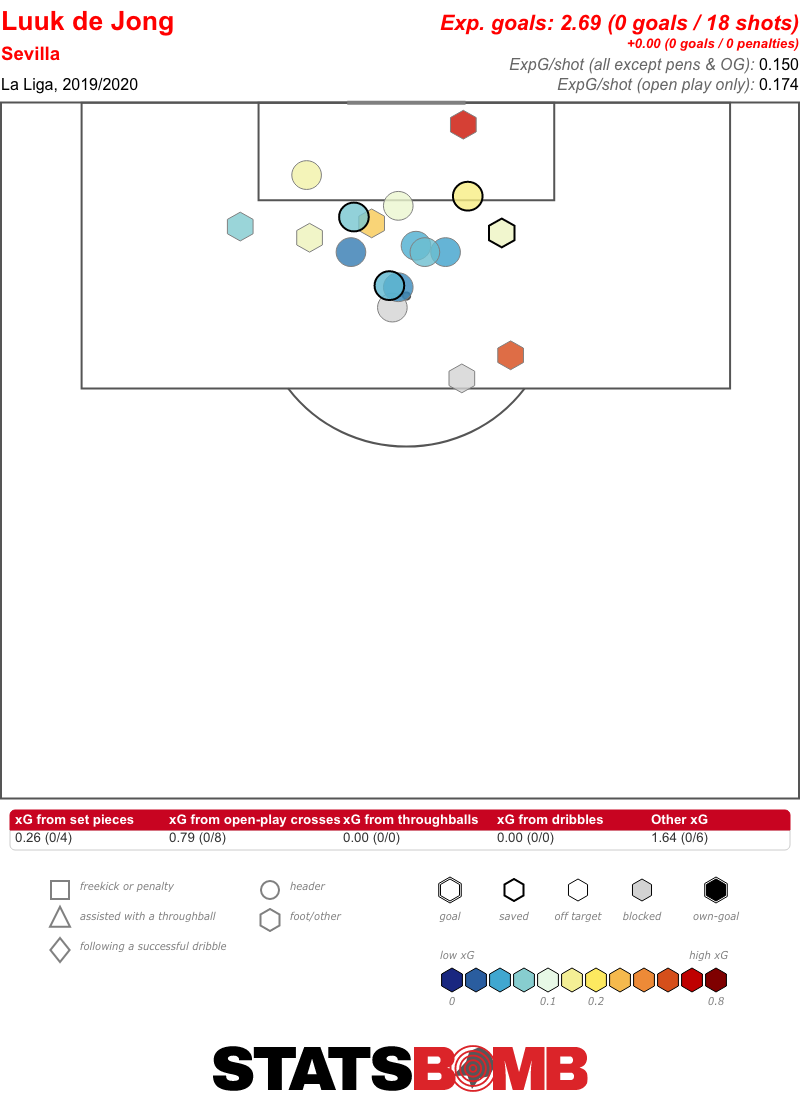

Espanyol provide him with the opportunity to prove that was a mistake. “It is a club that is improving, that wants to progress,” he said  Sevilla also have problems in the other penalty area. Goalkeeper Vaclík has been pretty bad so far this season, conceding four more goals than expected -- the biggest underperformance of any goalkeeper in La Liga to date.

Sevilla also have problems in the other penalty area. Goalkeeper Vaclík has been pretty bad so far this season, conceding four more goals than expected -- the biggest underperformance of any goalkeeper in La Liga to date.  The only team currently below Espanyol in the table are a Leganés side on two points. Their underlying numbers have been solid enough to suggest they are capable of more, and the club’s confidence in coach Mauricio Pellegrino rightly persists. But they really have to start getting some points on the board.

The only team currently below Espanyol in the table are a Leganés side on two points. Their underlying numbers have been solid enough to suggest they are capable of more, and the club’s confidence in coach Mauricio Pellegrino rightly persists. But they really have to start getting some points on the board.