Lord knows how much money it took to bring Alexis Sanchez to Old Trafford. And his arrival at Manchester United hasn’t gone smoothly. But after scoring the winner against Newcastle, he looks like he might finally turn things around.

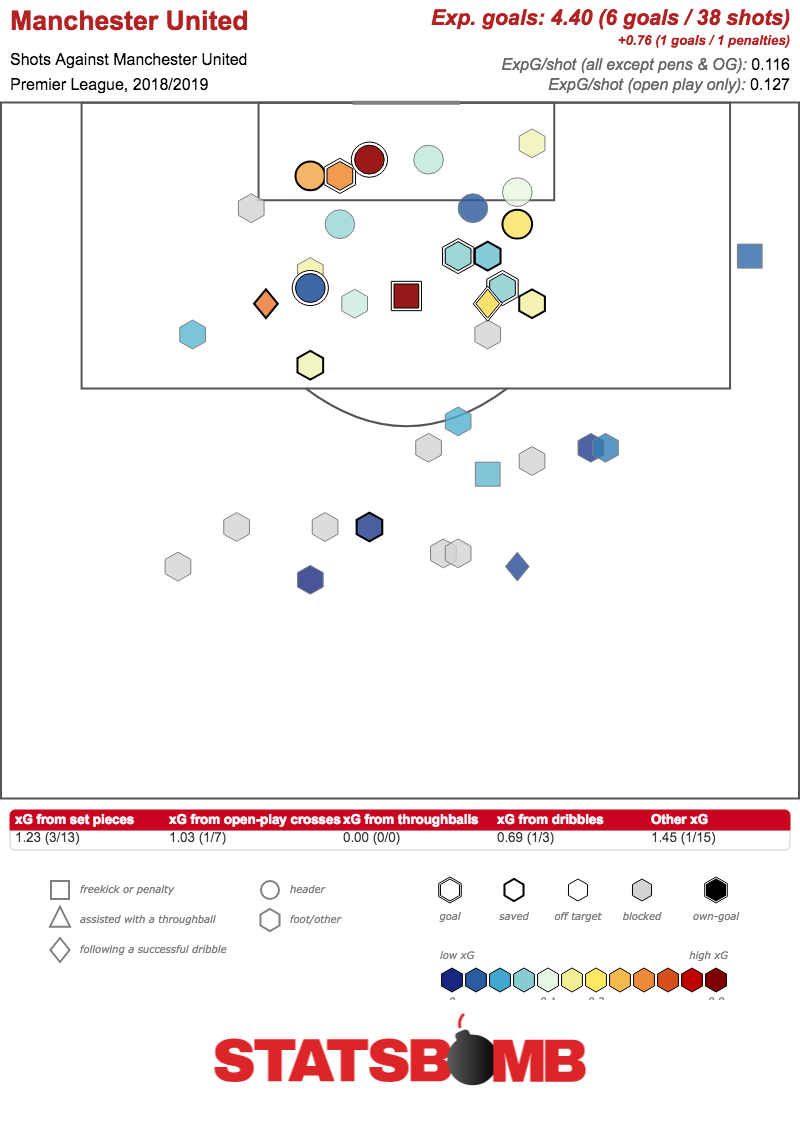

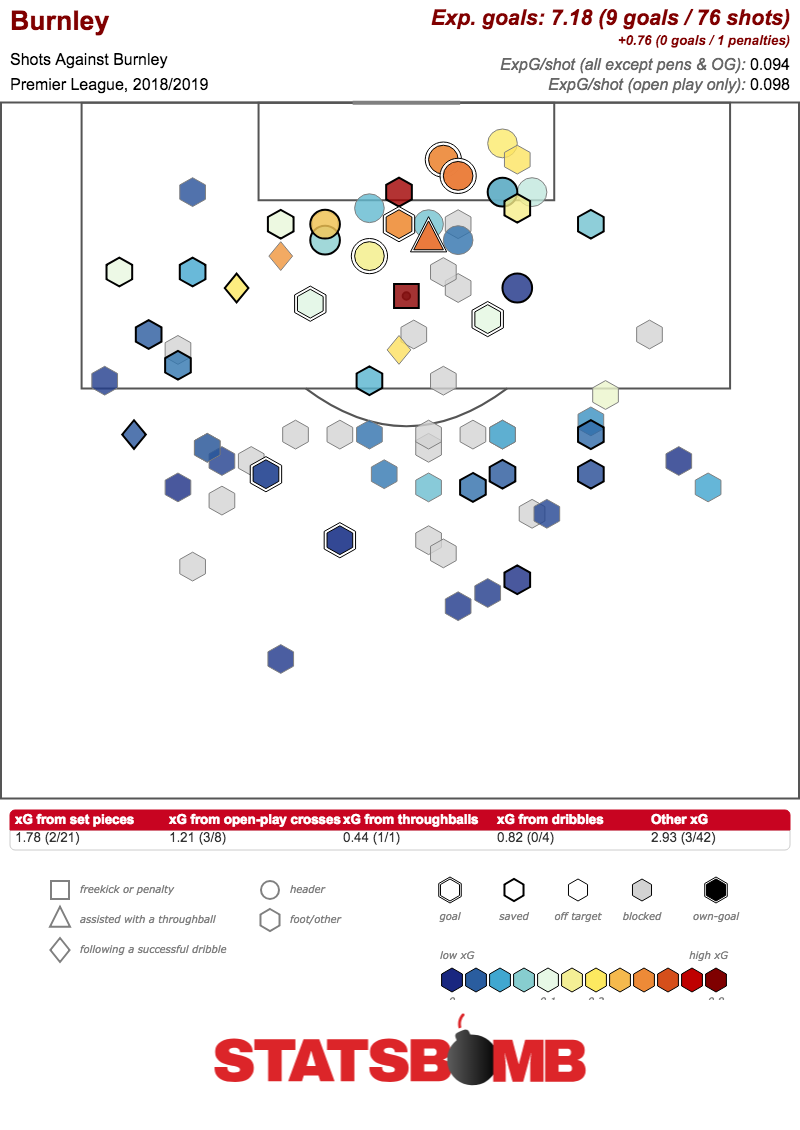

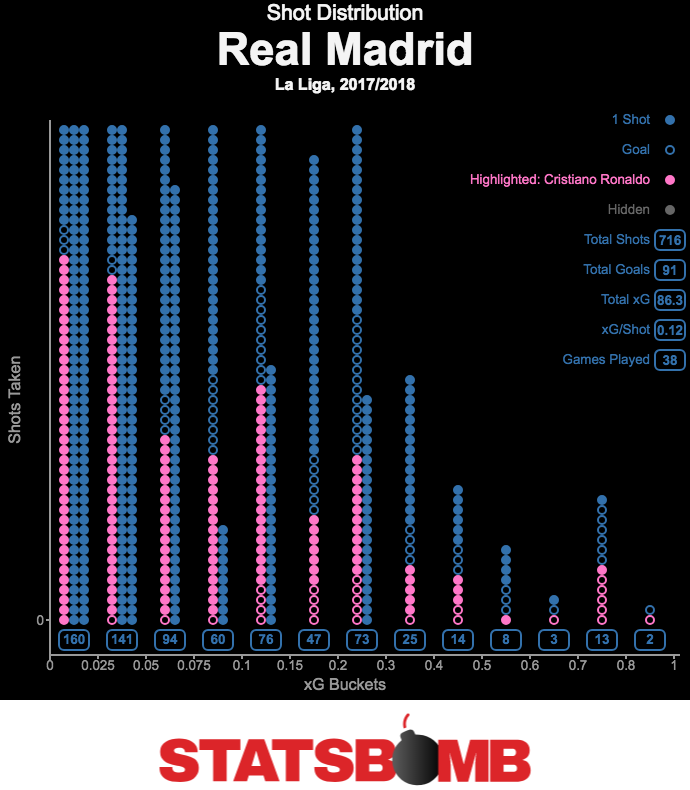

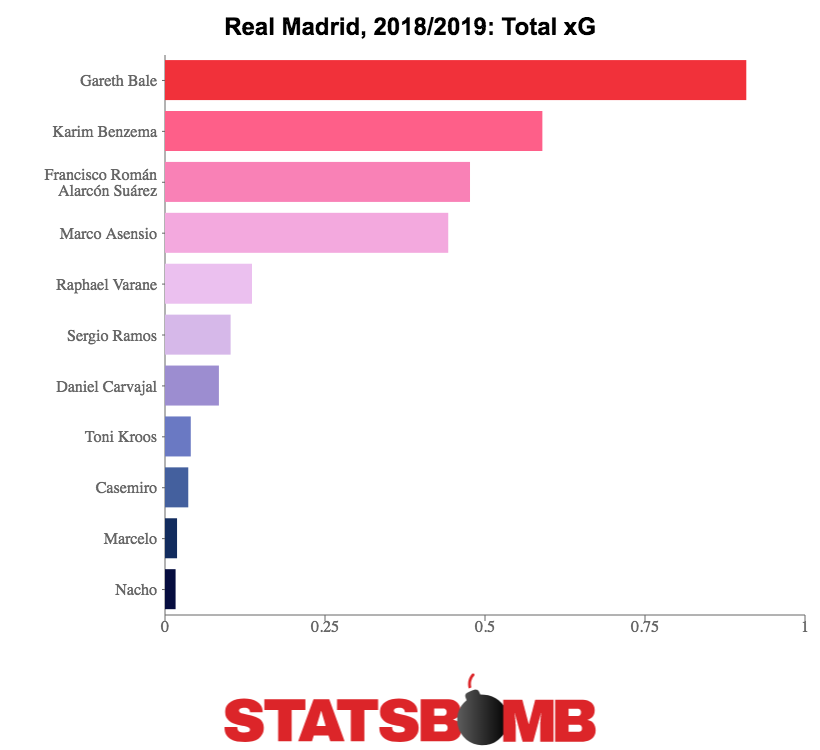

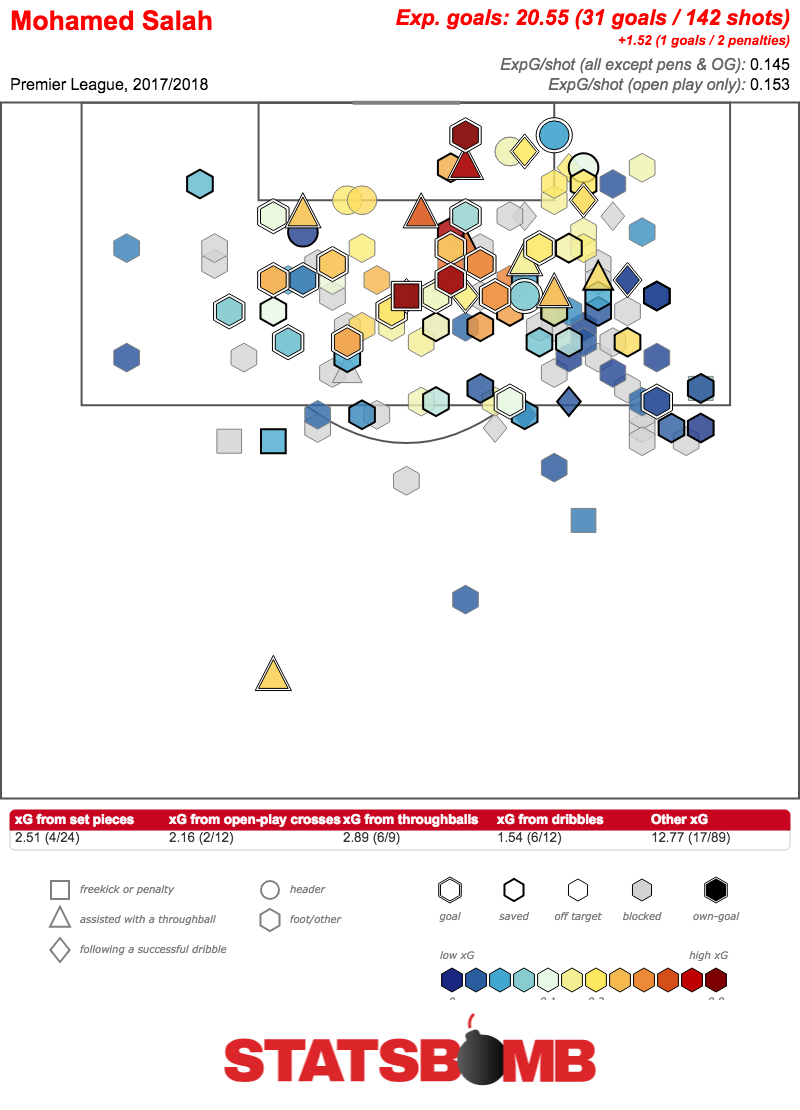

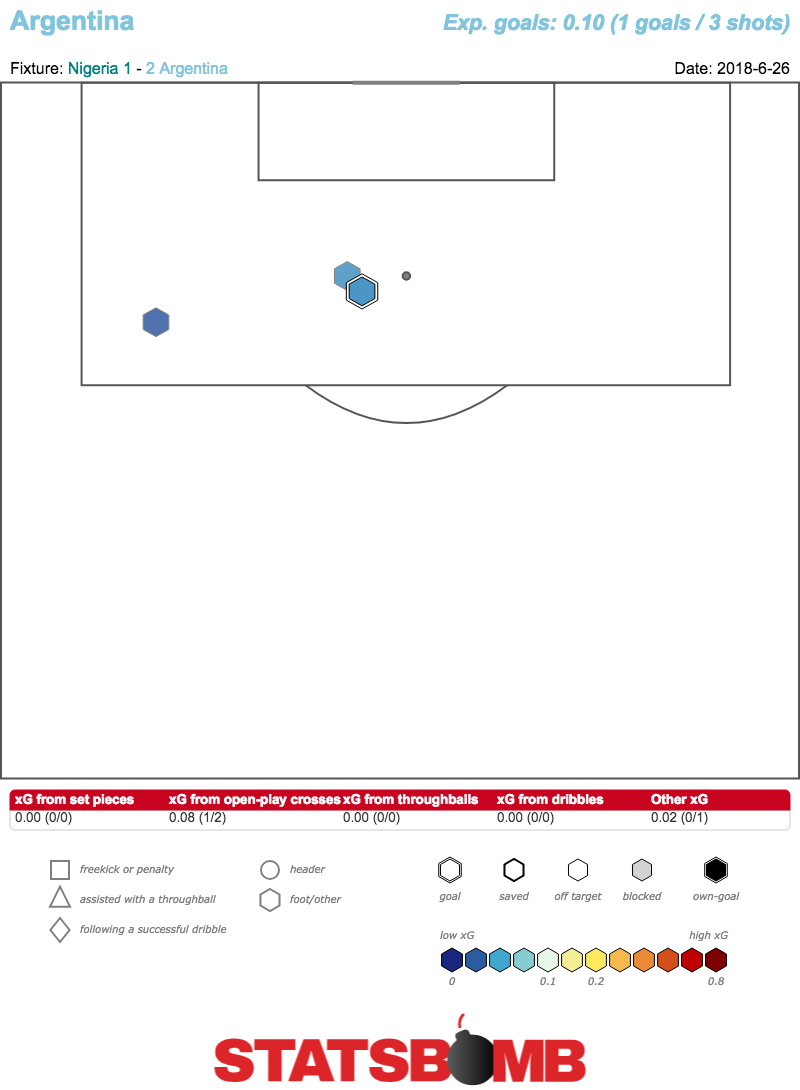

Just three goals since signing in January is, on the face of it, a terrible return for someone of his reputation. That’s a shade under his expected goals total (especially if you include the penalty he missed), but we’re still left with a very unremarkable volume of chances nonetheless:

Adjusted for time on the pitch, he’s generating 0.27 expected goals per 90, a very middling figure for a wide forward at a club with as much talent as Manchester United. In his last season at Arsenal, by comparison, he was hitting an xG per 90 of 0.42, achieved mostly through a higher volume of shots than he’s attempting at the moment, even if a fair few were from range.

The numbers show what most can see with their eyes: Sanchez is much less of a goalscoring threat at United than he was at Arsenal. To many, this is the end of the story. Of course, football isn’t just about scoring goals, so let’s take a look at what else the Chilean can do.

Evolving Role

For such a widely acclaimed talent, it’s notable that Sanchez hasn’t had a fixed position over career. Having played in a range of roles at Udinese, Sanchez went to Barcelona at a time when Pep Guardiola was experimenting with a back three. The plan seemed to be for the Chilean to offer a wider threat than the inverted forwards David Villa and Pedro. This system was similar to that of coaches’ coach and Guardiola favourite Marcelo Bielsa’s approach with Chile at the 2010 World Cup, and Sanchez’s experience in that role was surely a big part of why he was signed.

Of course, Guardiola left Barcelona in the summer of 2012 and his successors Tito Vilanova then Tata Martino both returned to the more familiar 4-3-3 associated with the Catalan club’s best sides. This meant Sanchez competing for the inverted wide forward roles either side of Lionel Messi. Playing so close to the five time Ballon d’Or winner tends to force players to sacrifice their own games, and Sanchez was no exception, with his volume of shots and dribbles taking a significant hit in this system. Still, he proved extremely effective at the limited things he did do, contributing more than one goal or assist per 90 minutes in his final season at the Camp Nou. Sanchez was a player performing a specific role, and performing it to an extremely high level.

After that specific role came the freedom. Sanchez joined Arsenal as a marquee purchase to add speed and directness to the attack, and he could not have found himself in a more different environment in North London than the Catalan capital. Arsene Wenger (remember him?) always believed in keeping things relatively simple, opting to let the players figure things out, rather than overload them with complex instructions. This allowed Sanchez the chance to finally do his thing largely unrestrained. Usually playing on either flank in a fairly basic 4-2-3-1, Sanchez found himself with team mates well suited to complement him. In the number ten role was the perennially unselfish Mesut Ozil, extremely uninterested in much other than facilitating those around him, while striker Olivier Giroud has often been a target man who likes to link up with a goalscoring wide player. This generally saw a much more involved and active Sanchez, putting in dominant performances even if he was prone to frequently giving away possession in the final third of the pitch. In some ways he had come full circle from his Barca days, now heavily involved but with some poor involvements.

With Wenger looking to move away from the focal point and unable to sign a high profile striker, Sanchez was moved to the centre forward role himself for much of the 2016-17 season. This was clearly a big part in him reaching a career best 22 non-penalty goals that season, though it led to Arsenal having an overall less cohesive attack. Sanchez’ link-up play was significantly less tidy than Giroud, in part leading to an Arsenal side less fluid in possession in the final third. The solution that Wenger stumbled upon was a switch to a 3-4-3 formation, with Sanchez and Ozil both in relatively central attacking roles behind a true striker (initially Giroud, then Alexandre Lacazette after his summer purchase). This system certainly had its drawbacks, particularly in the way that it would expose the midfield partnership of Granit Xhaka and Aaron Ramsey. It did, though, get the best out of Sanchez, allowing him the freedom to do what he does without sacrificing the rest of the attack, as it did previously. The problem with him bleeding possession remained (as seen with the high number of turnovers on the radar below), but there was still little doubt that he was a highly productive attacking threat.

Which brings us to…

United’s Number Seven

Alexis Sanchez wasn’t supposed to go to Manchester United. He was expected to end up at Manchester City, where he would find himself reunited with Guardiola. While the City boss knows the player well, this always felt like it would’ve been somewhat of a luxury purchase, and Sanchez, who had at this point spent several years with limited tactical instruction under Wenger, may have found it difficult to adjust to the Catalan’s strict positional play.

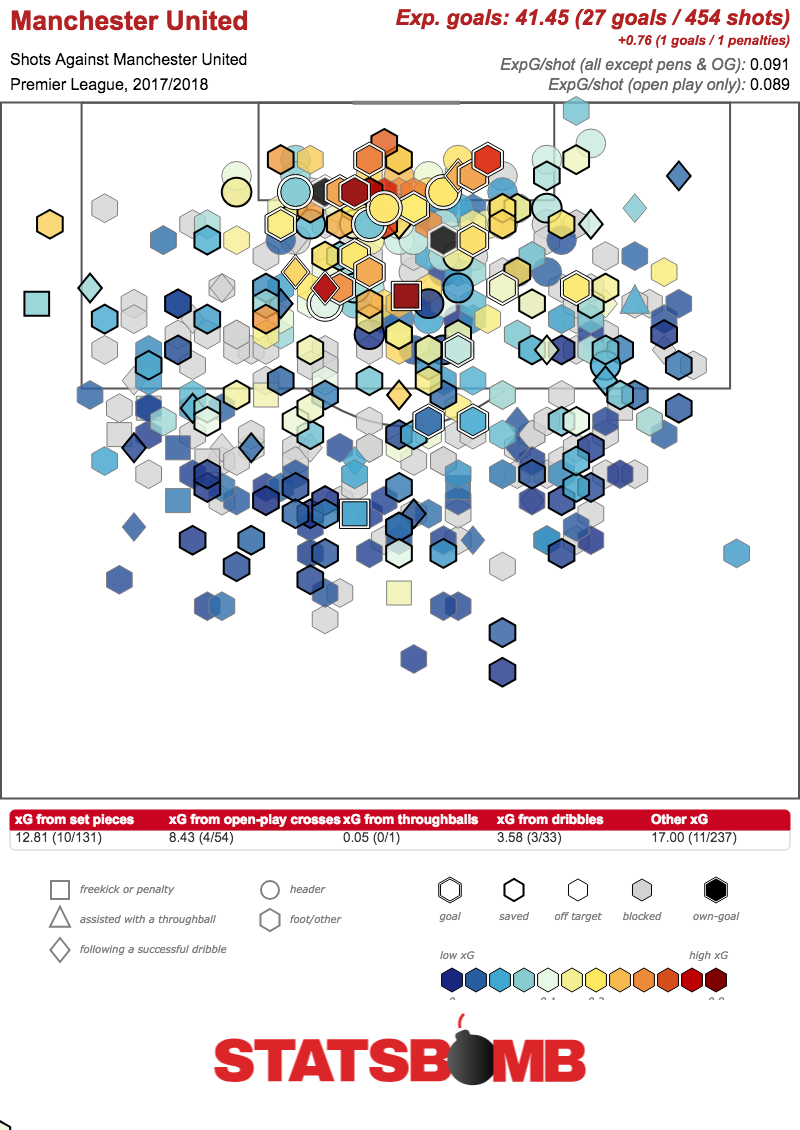

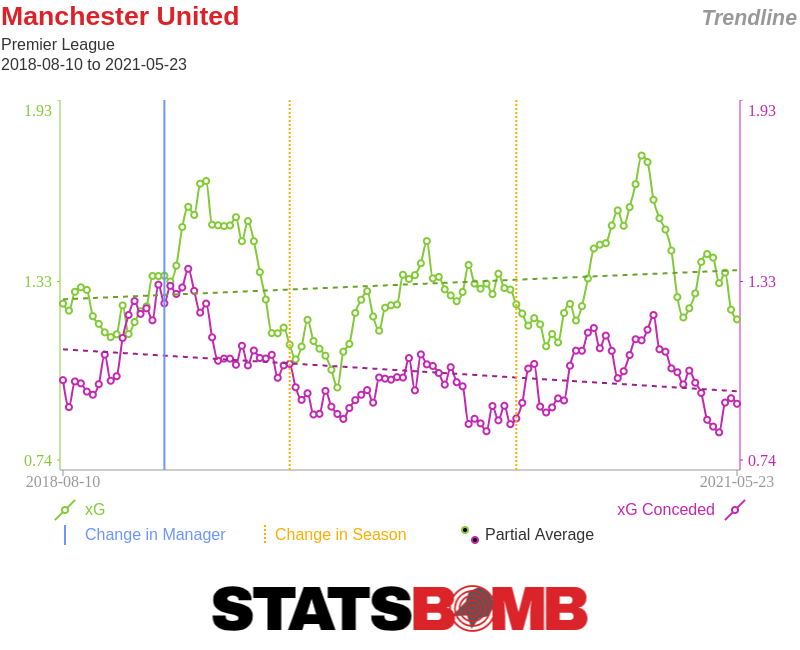

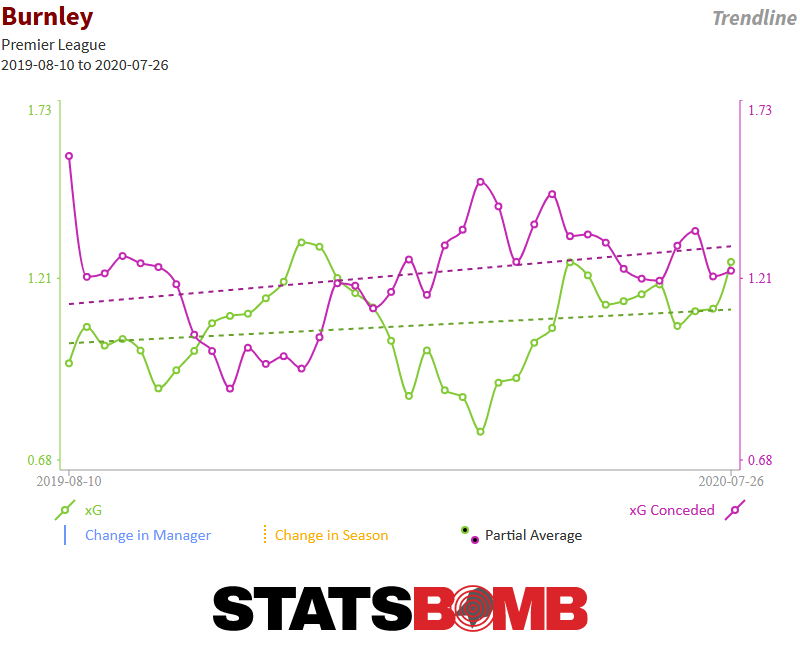

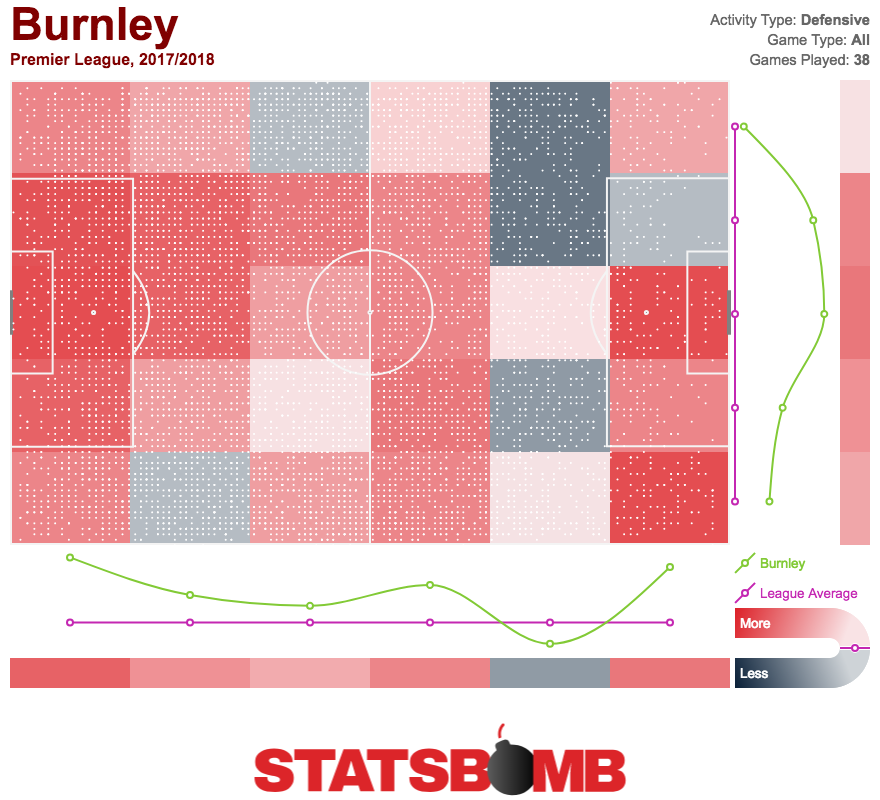

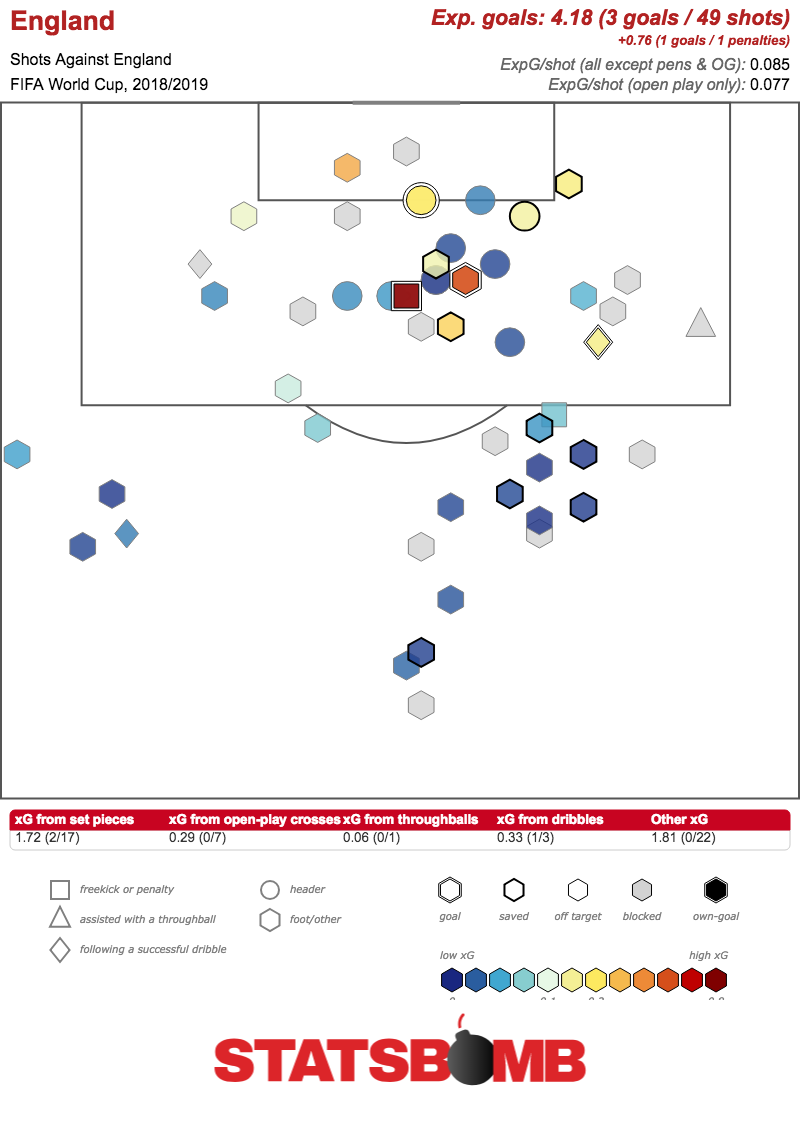

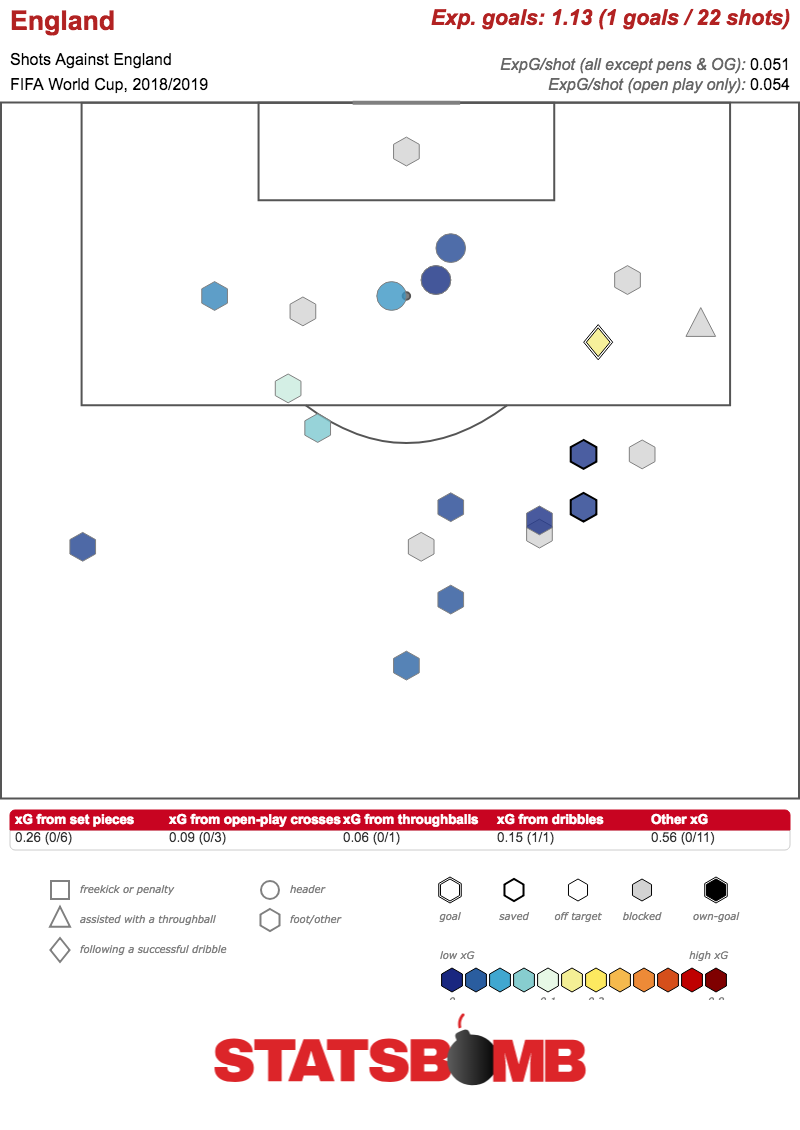

United and Jose Mourinho made more sense in this regard. Existing wide options consisted of players like Marcus Rashford and Anthony Martial, full of talent but still yet to deliver significantly in terms of goals and assists, or players without the dynamism of Sanchez, such as Juan Mata and Henrikh Mkhitaryan. In the case of Mkhitaryan, it also seemed that he was never going to be a good fit with Mourinho, so moving him on was logical, especially when he could be replaced with a player of Sanchez’s quality. Mourinho, while certainly someone much more defensively disciplined than Wenger, does like to keep it simple in attack, and allows his players much more of a licence to work it out themselves on that side of the ball than someone like Guardiola. The specifics of United, though, have proven not quite as ideal. Sanchez has generally featured in either wide role in a 4-3-3 system, which is fine. The central striker, though, has been Romelu Lukaku. There is no doubting that Lukaku is a terrific out-and-out striker, but he is someone who thrives as the side’s primary goal threat. Someone like Giroud was happy to allow Sanchez to dominate the team, but a club with Lukaku leading the line need to use the Belgian as someone to get on the end of chances, not facilitate them. With the sale of Mkhitaryan at the same time as Sanchez’s arrival, and Mata’s role being largely as a substitute, there was also a lack of an Ozil style playmaker. The best creative passer already at United was probably Paul Pogba, but the Frenchman has such a wide ranging skillset that it doesn’t always make sense to define him by simply one task. As such, Sanchez would have to take on more playmaking responsibilities himself. In this new team, the Chilean has had to reinvent himself as someone who both works harder defensively and does more of his work as a creator rather than a scorer.

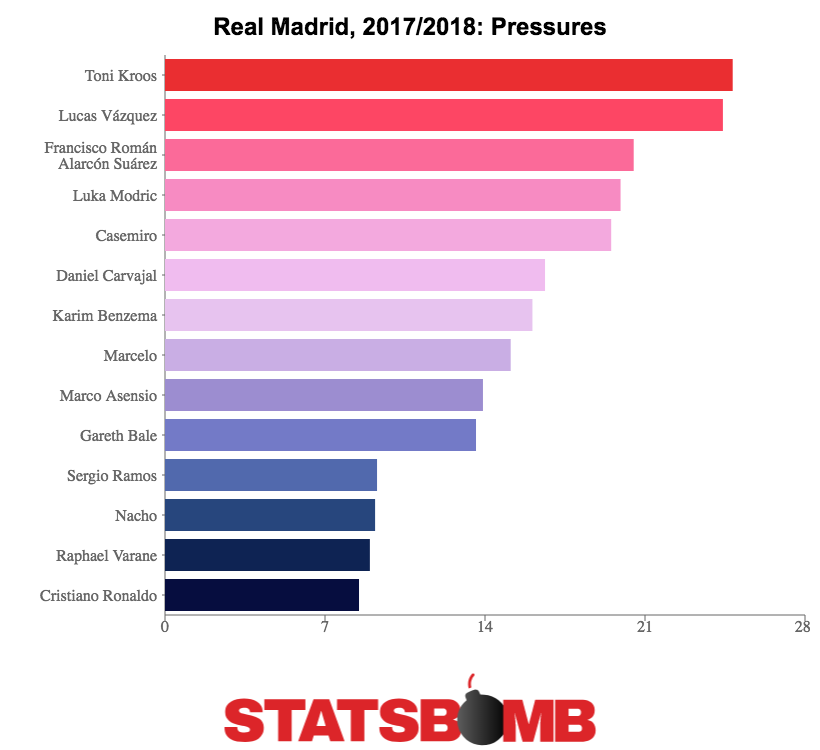

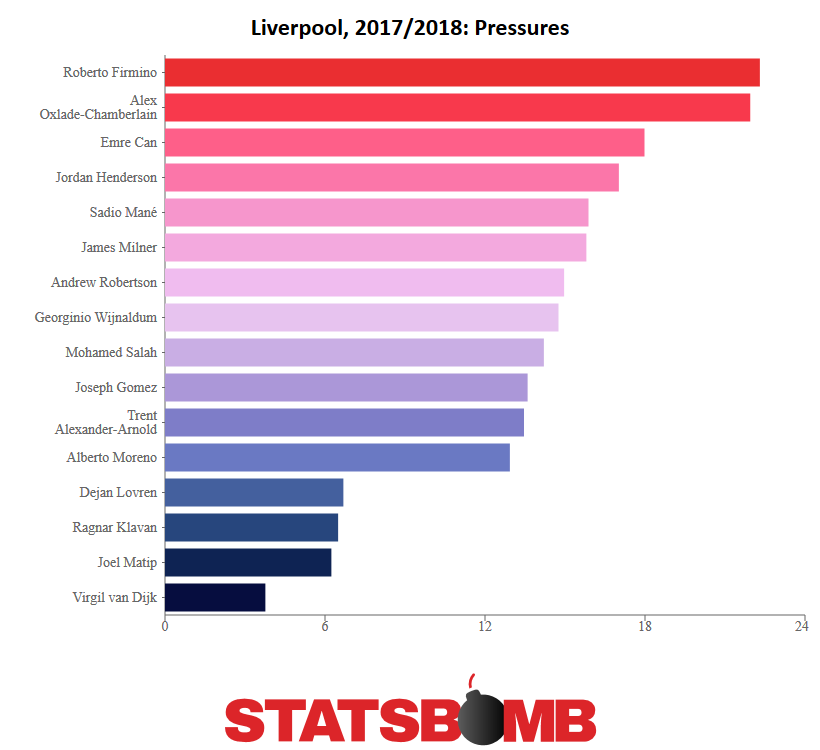

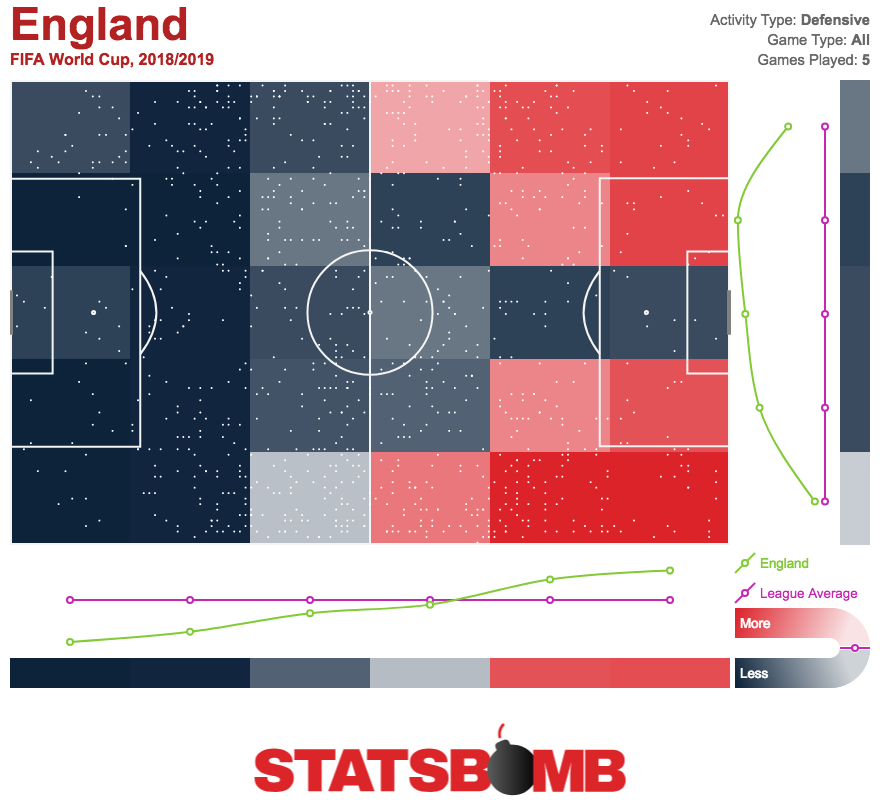

On the first count, he is certainly a more active defender than before. Looking at StatsBomb’s pressure event data shows us that in his final half-season at Arsenal, Sanchez was making 13.09 pressures per 90. Since arriving at Old Trafford, that figure has risen to 20.92. Looking at Sanchez’s output on the midfield radar, we can see that while the attacking side has dropped off a little, he is working harder defensively.

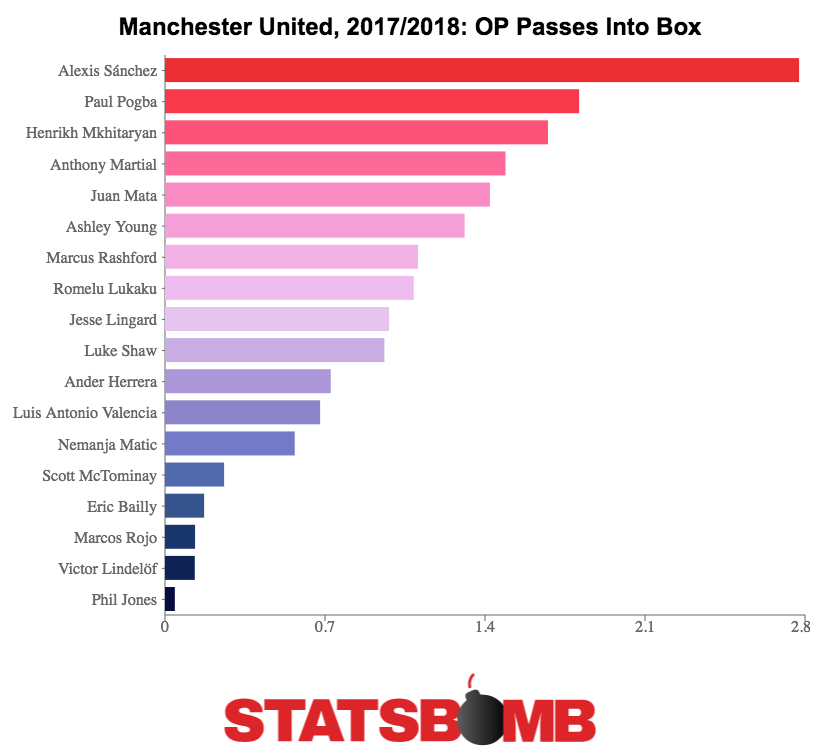

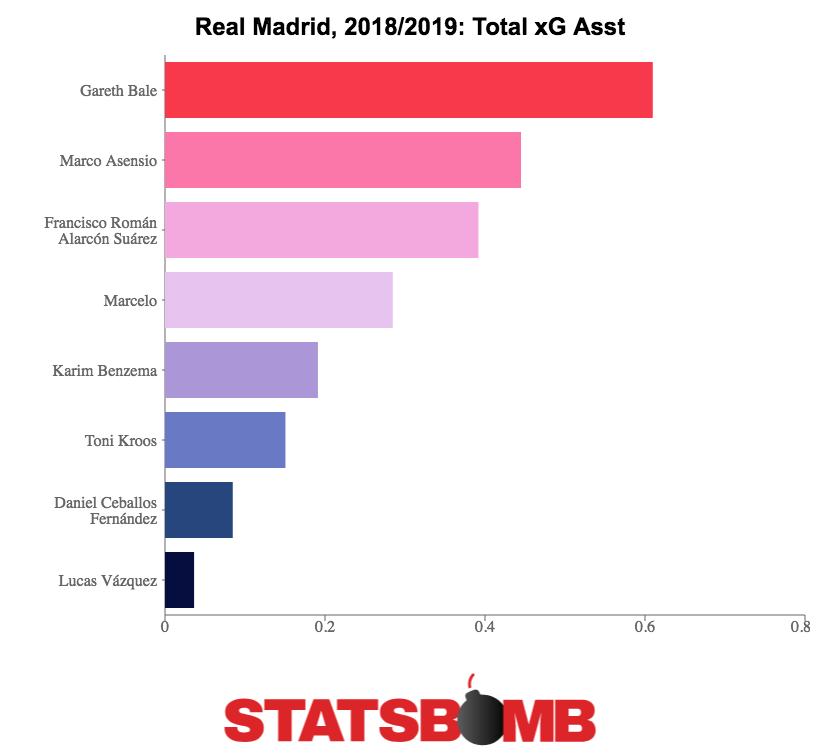

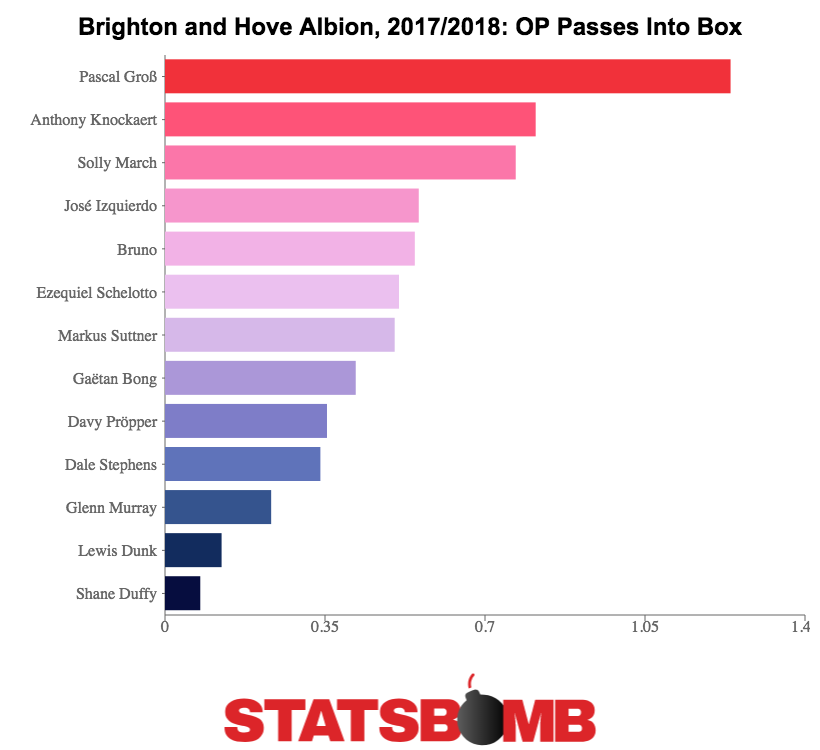

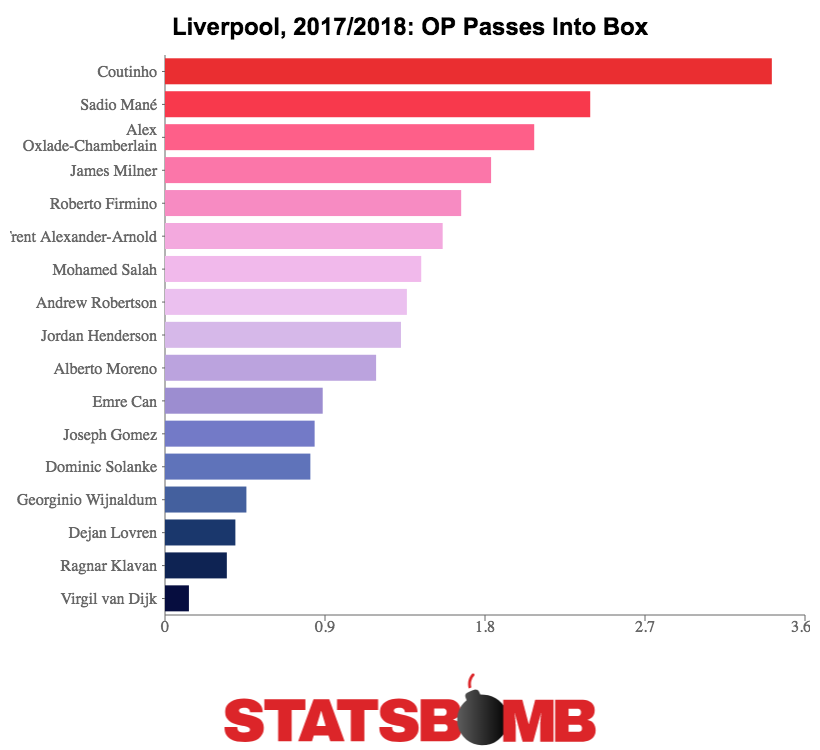

On the playmaking side, it has gone largely unnoticed that Sanchez has taken on much more responsibility. When looking at open play passes into the opponent’s box per 90 minutes, Sanchez is the clear standout among players at United (this graph only covers last season, but he is also currently top of the stat this year, too).

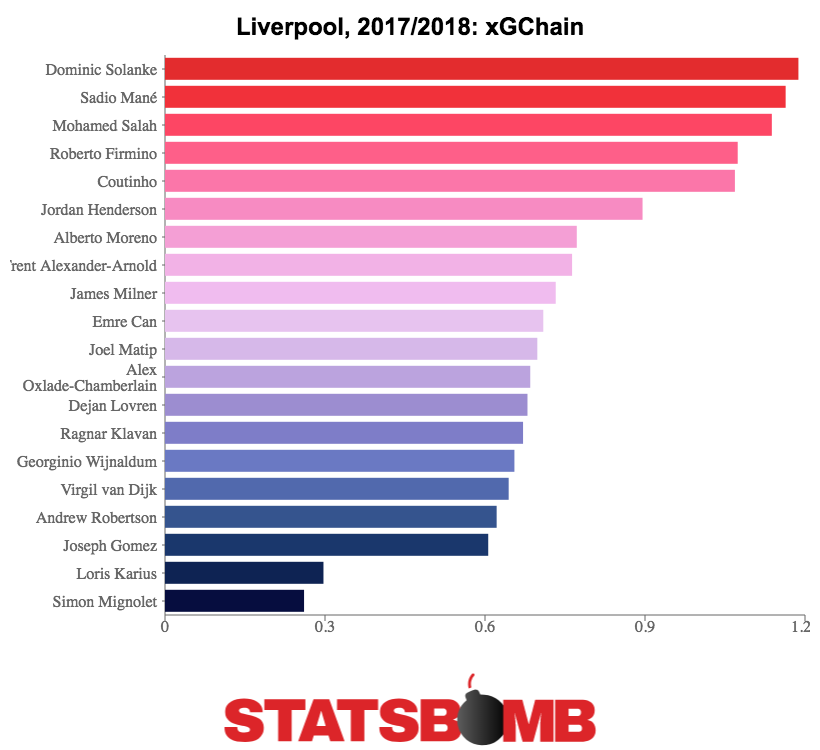

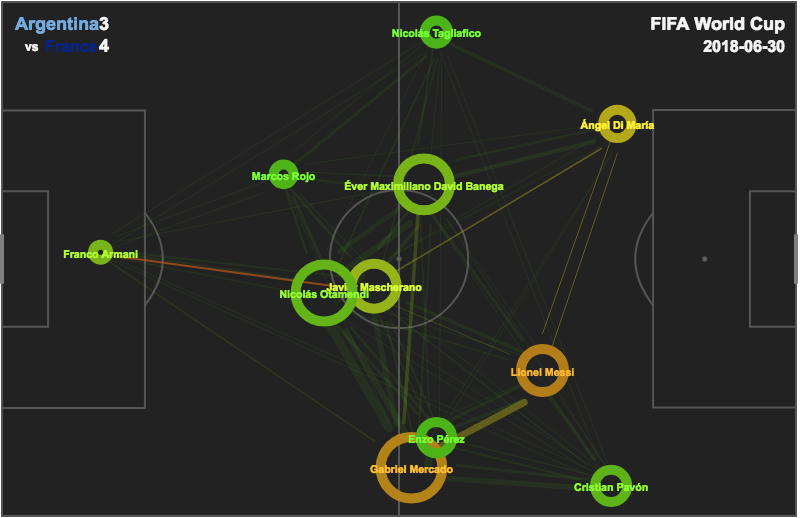

His contributions have often come at big moments, as well, with the aforementioned winning goal against Newcastle not his first game changing moment. In the now famous 3-2 win to prevent Manchester City winning the title that day, Sanchez was involved in all three United goals, providing two impressive assists and a delightful “hockey assist” (the assist to the assist). Sanchez recorded the highest xGChain of any United player that day. He changed the game.

Conclusion

Sanchez has proven to be something of a chameleon over his career. The roles he has filled for Chile, Udinese, Barcelona, Arsenal and now Manchester United have all varied in what is required, and he has always adapted to the challenge. It is his time at Arsenal that most Premier League fans primarily know him for, and as such those are the kind of performances they expect, single handedly grabbing games and driving the team forward, scoring plenty of goals in the process.

For all of the issues that Mourinho has caused himself at Old Trafford, opting not to use Sanchez in this way is not one of them. In Lukaku, United already have a primary goalscorer, while Martial and Rashford offer threat in terms of wide forwards getting in the box and on the end of chances. What Sanchez does better than those players is offer a more complete threat, as someone who works hard defensively while getting involved in the build up play. This might not be a hugely beloved era of Sanchez’s career, but it isn’t without merit, and certainly shouldn’t be considered a write-off.

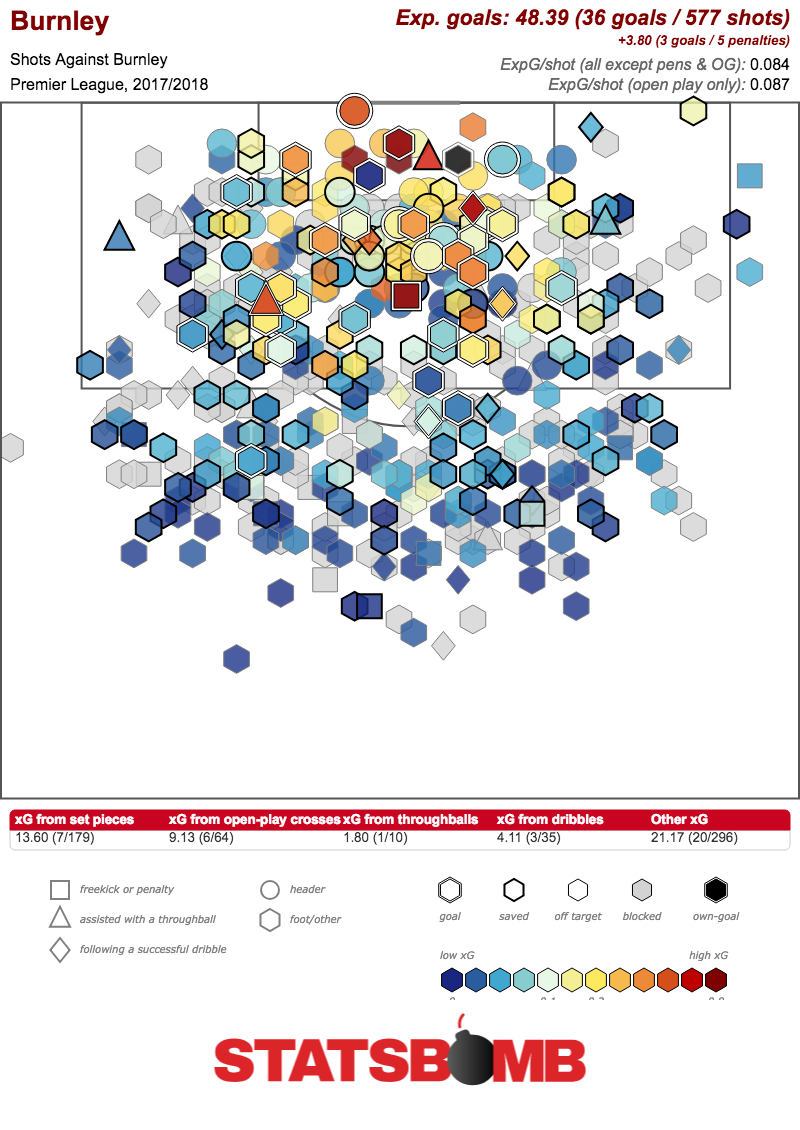

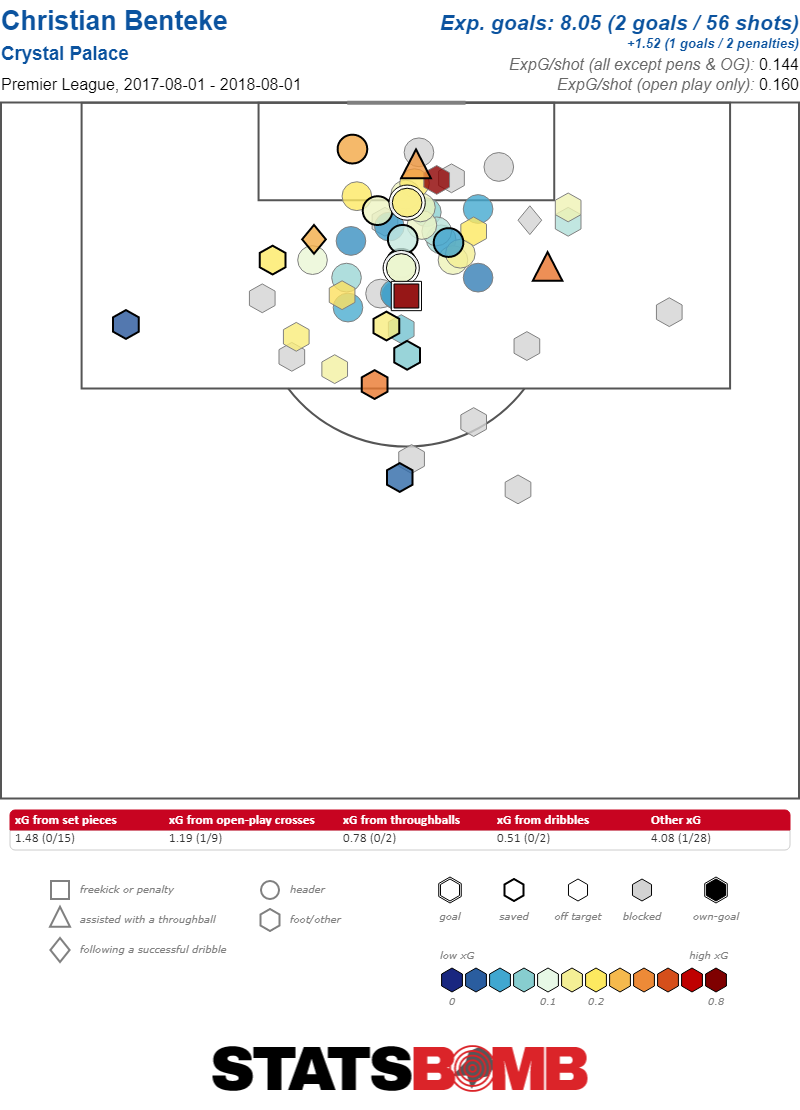

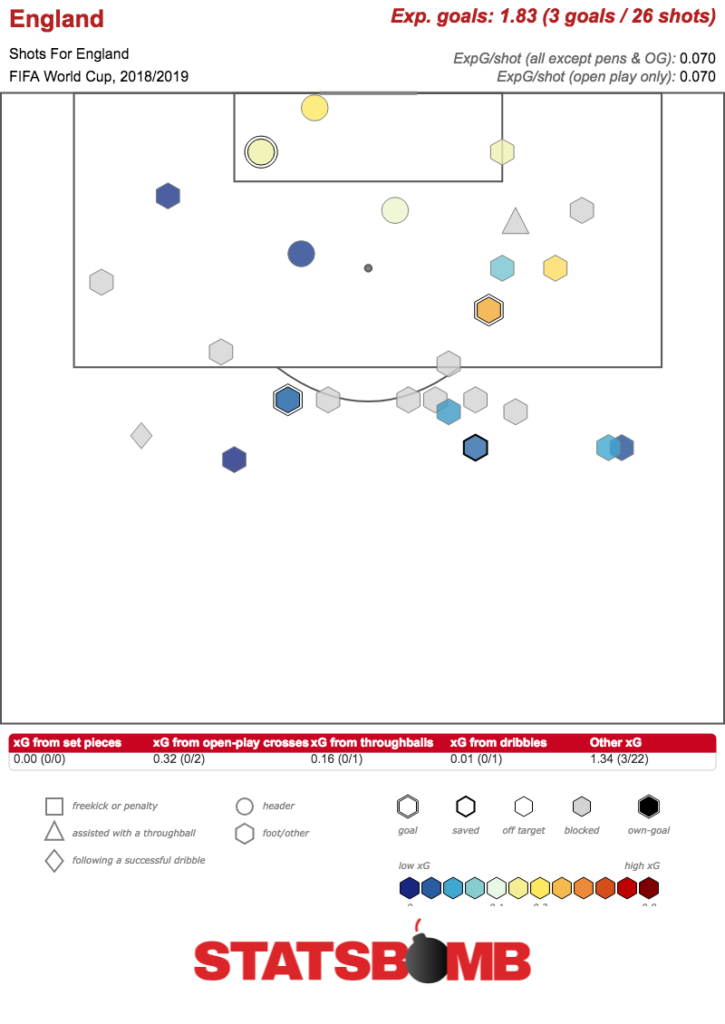

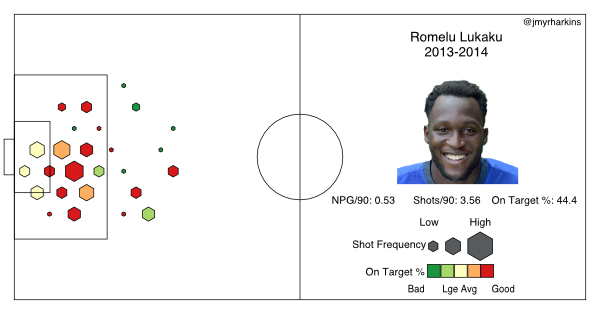

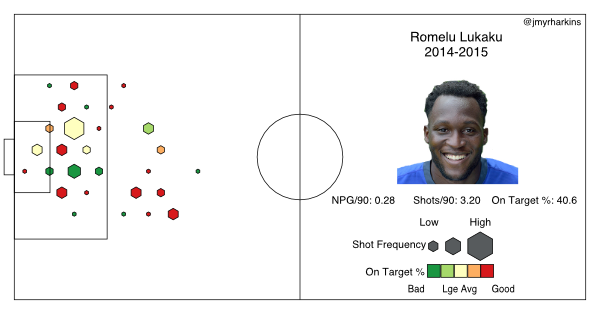

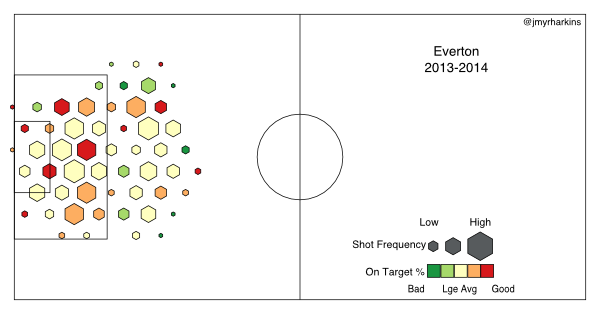

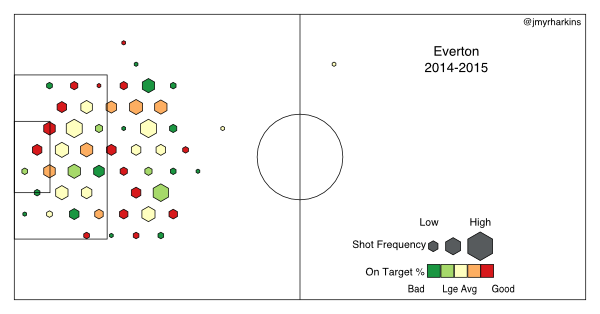

Lukaku’s own shot charts mimic those of Everton, whose accuracy and volume from within the penalty area has dropped off this year. Viewed in this context, Lukaku seems to be suffering more from Everton’s attacking dysfunction as a team than an individual inability to generate and finish chances. Romelu Lukaku may not be on fire the way he was last season, but his teammates aren’t helping, and he may take some time to settle into a full-time role as the top striker at a Premier League club. Though some of Lukaku’s struggles are real, panicking about his development now seems very premature.

Lukaku’s own shot charts mimic those of Everton, whose accuracy and volume from within the penalty area has dropped off this year. Viewed in this context, Lukaku seems to be suffering more from Everton’s attacking dysfunction as a team than an individual inability to generate and finish chances. Romelu Lukaku may not be on fire the way he was last season, but his teammates aren’t helping, and he may take some time to settle into a full-time role as the top striker at a Premier League club. Though some of Lukaku’s struggles are real, panicking about his development now seems very premature.