The World Cup is upon us and there are some reasons for optimism about the England national team. The side made it through qualification without breaking a sweat, conceding only three goals across ten games, and contains some of the most exciting attackers in the Premier League. One significant area of concern, however is central midfield. Looking through the team, it's difficult to find anyone who naturally excels in the all-around central midfield role. Jordan Henderson and Eric Dier are most accustomed to playing at the base of a midfield. Dele Alli and Jesse Lingard are used to playing in more advanced roles closer to the forward line than the midfield. There’s Ruben Loftus-Cheek, a central midfielder by trade, but one who has only experienced one season of regular senior football, and it was on the left of a four man midfield. Then there’s Fabian Delph, a natural midfielder who has just had the season of his life at left back. The days of Paul Scholes, Steven Gerrard, and Frank Lampard are long gone. Dealing with this issue seems to be at the heart of manager Gareth Southgate’s formation switch. After sticking with a solid 4-2-3-1 throughout qualification, he has largely embraced a 3-5-2 system since then. This is not the 3-4-3 system Southgate experimented with at times in 2017, instead it's a formation which noticeably uses a midfield three. In the friendly against the Netherlands for example, Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain and Jesse Lingard (numbers 7 and 11 in the picture) were generally found level with each other, alternating at taking more advanced roles.  Out of possession, the full backs generally moved into more defensive roles next to the centre-backs, leaving the three central midfielders to screen the back line.

Out of possession, the full backs generally moved into more defensive roles next to the centre-backs, leaving the three central midfielders to screen the back line.  While in possession, one of the forwards (more often than not Raheem Sterling, number 10 in the image) will frequently drop into a deeper role, creating space for the two central midfielders to advance.

While in possession, one of the forwards (more often than not Raheem Sterling, number 10 in the image) will frequently drop into a deeper role, creating space for the two central midfielders to advance.  This system demands a lot of energy from the central midfielders. They need to move into more advanced roles assisting the attack while also returning to their roles in a quite a defensive shape without the ball. Plenty of athleticism will be required. And while the shape is clearly designed to mitigate the problem of a lack of creative passers in the England squad, any ability to help transition the ball forward will be of great use. As such, let’s take a look at the options:

This system demands a lot of energy from the central midfielders. They need to move into more advanced roles assisting the attack while also returning to their roles in a quite a defensive shape without the ball. Plenty of athleticism will be required. And while the shape is clearly designed to mitigate the problem of a lack of creative passers in the England squad, any ability to help transition the ball forward will be of great use. As such, let’s take a look at the options:

Ruben Loftus-Cheek

Perhaps surprise inclusion in the squad, Ruben Loftus-Cheek’s skillset is fairly wide-ranging and atypical of a central midfielder. Despite being a full six foot, three inches tall, Loftus-Cheek has a lot of mobility and was able to be an important transition player on the left of Crystal Palace’s 4-4-2 system this season. While nominally playing out wide, Roy Hodgson’s system was often so narrow that he ended up in positions more commonly associated with the central role he has played for Chelsea’s youth sides. In that role he turned into a surprisingly productive dribbler of the ball. While hitting 3.5 dribbles per 90 at age 22 is a strong but not exceptional figure (the research has long indicated that players peak early in terms of volume of dribbles), many players can be generally wasteful with this. Loftus-Cheek avoided that pitfall, consistently managing to recycle the ball well after dribbling, leading to good counter-attacking opportunities for Palace. The data gathered by StatsBomb's own Euan Dewar shows the Englishman as one of the more productive dribblers around, and this is evident from watching him.

In an England squad desperately thin in terms of players able to progress the ball, he has the knack for it, albeit through running rather than passing. There are some concerns about his defensive work. While not an unwilling defender, he has spent the season in a more traditional deep block 4-4-2. StatsBomb’s data puts Palace as the second least aggressive counter pressers in the Premier League and this is down to Hodgson liking his side to return to a compact shape without the ball. Most of the England team is going to be made up of players from the aggressive pressers of Spurs, Liverpool and Man City, so Loftus-Cheek my well be a weak link when it comes to understanding when to pressure the opponents and when to sit back. Nonetheless, he does have some real tools that can help the side.

Fabian Delph

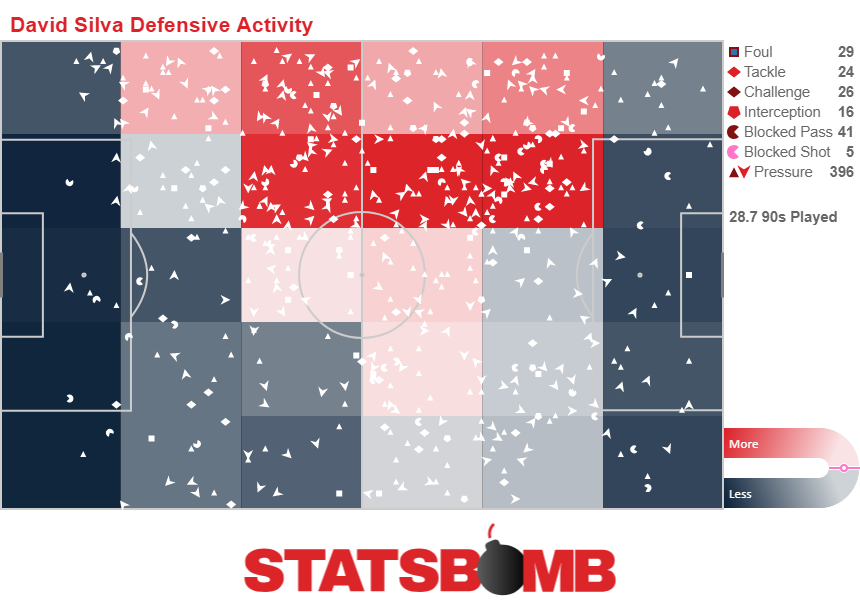

After spending his career as a solid but unremarkable central midfielder for Aston Villa and then Manchester City, converting to left-back led to his emerge as a valuable cog in Pep Guardiola’s machine. At first glance. the decision to include him in the squad as a central midfielder then may seem poorly thought out, but it does make tactical sense. Ever the innovator with fullbacks, Guardiola generally instructed Delph to move inside to a central midfield role alongside Fernandinho in possession, with Kyle Walker at right back shuffling in alongside the centre-backs (John Stones and Nicolas Otamendi for the first half of the season, though he has shuffled the pack since) to form a back three behind them. Southgate is well aware of that structure, and, in fact, referenced it while explaining his decision to play Kyle Walker at centre-back, saying, “he ends up in that area anyway." It’s not a surprise to see the England manager interpret Delph’s role similarly. The familiarity of Delph, Stones, and Walker all playing roles in a defensive unit structured similarly to Manchester City’s could be of use when international football generally doesn’t allow players the time to form strong relationships on the pitch. What’s less exciting about Delph is what he does on the ball. At City he is fortunate enough to play alongside two of the best creative passers on the planet in Kevin De Bruyne and David Silva. Delph can keep his passing relatively simple and letting those two run the show (and with Guardiola’s strict positioning, there are always a number of options available). England would require him to be a more creative outlet, which is something he’s never been able to do to great effect. As such, he might be more suited to playing in the knockout stages, against higher quality sides who will look to dominate possession, when England will need to retain a strong defensive structure before using players like Sterling and Kane on the counter.

Jesse Lingard

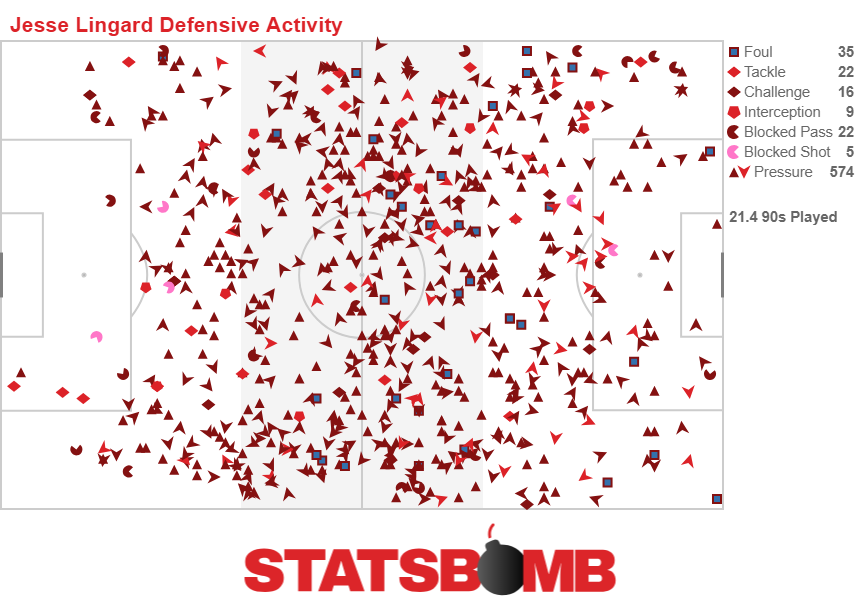

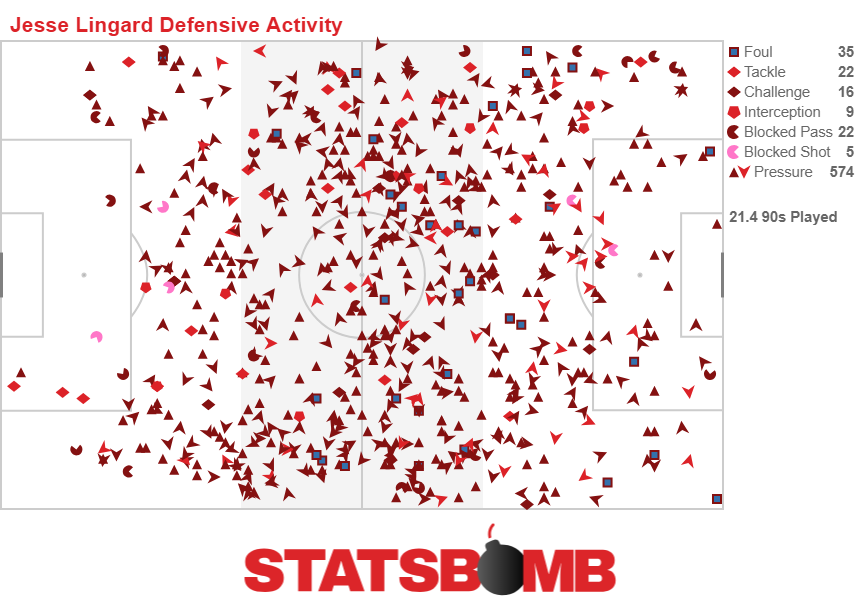

While he is not someone who might be seen as a central midfielder in, say, a 4-2-3-1, Southgate’s system does allow for players who function closer to what is now being described as a “free eight”, with the licence to play as something more akin to a number ten a lot of the time than a “true” midfielder. Lingard has played in a number of roles this season, but looked particularly dangerous playing as a free eight in Manchester United’s 3-1 victory away to Arsenal in December. The attribute Lingard probably excels at the most is pressing, with Will Gurpinar-Morgan’s research putting him as the best player in the Premier League at regaining possession via pressure, and second best at applying pressure generally. What’s interesting is how much he does this across the pitch rather than in any one specific area, as shown in this graphic:  Pressing ability is usually thought of in terms of energy and work rate, qualities Lingard has in abundance. But what is also key is the intelligence to take up the right positions to pressure the opposition player on the ball, and this is what really makes him special. This excellent positional work is to be seen in an attacking sense as well, with his 0.39 expected goals per 90 minutes the best of the players on this list. A lot of Lingard’s goals this season have come from him managing to slip away from defenders to find space for a shot, even in a congested penalty area. Lingard’s off the ball work is outstanding, but his on the ball actions don’t quite reach the same heights. His 1.18 key passes per 90 is unimpressive when one considers he’s an attacking midfielder for a team as stocked with attacking talent as Manchester United. Juan Mata, Alexis Sanchez, Anthony Martial, Paul Pogba, and the shipped out Henrikh Mkhitaryan were all better chance creators for the same United team this season. When watching Lingard, he does sometimes have the frustrating tendency to favour the safer passing option, and his passing accuracy of 87.8% is more indicative of a limited range than anything else. It seems as though he’s most suited to high tempo, frantic games, while one imagines England’s first two fixtures against Tunisia and Panama will not fit that mould.

Pressing ability is usually thought of in terms of energy and work rate, qualities Lingard has in abundance. But what is also key is the intelligence to take up the right positions to pressure the opposition player on the ball, and this is what really makes him special. This excellent positional work is to be seen in an attacking sense as well, with his 0.39 expected goals per 90 minutes the best of the players on this list. A lot of Lingard’s goals this season have come from him managing to slip away from defenders to find space for a shot, even in a congested penalty area. Lingard’s off the ball work is outstanding, but his on the ball actions don’t quite reach the same heights. His 1.18 key passes per 90 is unimpressive when one considers he’s an attacking midfielder for a team as stocked with attacking talent as Manchester United. Juan Mata, Alexis Sanchez, Anthony Martial, Paul Pogba, and the shipped out Henrikh Mkhitaryan were all better chance creators for the same United team this season. When watching Lingard, he does sometimes have the frustrating tendency to favour the safer passing option, and his passing accuracy of 87.8% is more indicative of a limited range than anything else. It seems as though he’s most suited to high tempo, frantic games, while one imagines England’s first two fixtures against Tunisia and Panama will not fit that mould.

Dele Alli

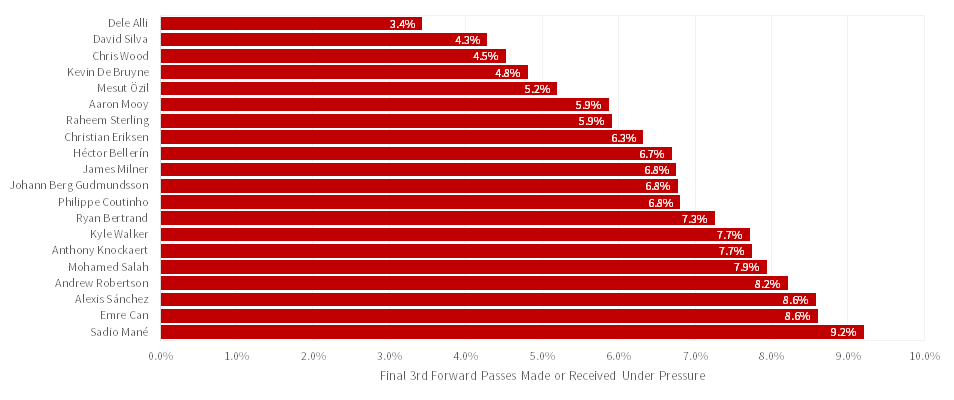

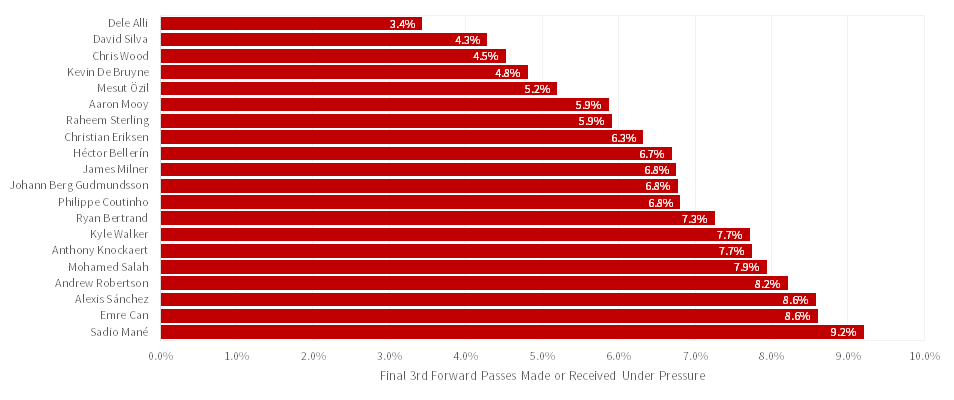

The most established player on this list and yet paradoxically the youngest. He’s coming off a season where his goal scoring work declined somewhat (0.30 expected goals per 90 compared to 0.43 the season before), but was balanced out with greater work in terms of chance creation and a strong all-around game. Alli hit almost identical xGChain in both years. He's a more than able presser, coming up not too far behind Lingard in Gurpinar-Morgan’s “possession regains via pressure” metric. Like Lingard, part of the reason for his good pressing work is in the intelligent positions he takes up, and that is one area where he measurably stands out. Looking at StatsBomb’s data for actions under pressure, Thom Lawrence showed that no player in the Premier League last season had a lower percentage of his passes made or received in the final third “under pressure”. The implied value in this is that Alli appears to be particularly adept at evading pressure from opposition players in the final third, being able to find areas of space even in an often congested zone of the pitch.  This excellent appreciation of space is probably the thing that sums up Alli’s game the best. His passing is useful, but this comes less from superb technique than good tactical intelligence that helps him find teammates in space. Part of this is from a good understanding with the other Spurs players, and while this would typically be a negative for a player in an international side, that won't necessarily be the case give how many of his Tottenham teammates are in the England side. Harry Kane is likely to be the fulcrum of England’s attack, with boths Kieran Trippier and Danny Rose probably providing delivery from wide areas. Adding another important Spurs cog in Alli could help England to have a more coherent attack than many nations selecting players from a number of different clubs.

This excellent appreciation of space is probably the thing that sums up Alli’s game the best. His passing is useful, but this comes less from superb technique than good tactical intelligence that helps him find teammates in space. Part of this is from a good understanding with the other Spurs players, and while this would typically be a negative for a player in an international side, that won't necessarily be the case give how many of his Tottenham teammates are in the England side. Harry Kane is likely to be the fulcrum of England’s attack, with boths Kieran Trippier and Danny Rose probably providing delivery from wide areas. Adding another important Spurs cog in Alli could help England to have a more coherent attack than many nations selecting players from a number of different clubs.

Conclusion

With Southgate opting to start Lingard and Alli in Saturday’s friendly against Nigeria, it seems likely that these two are his preferred options in midfield. This is deserved on merit, with the two of them being the best performers of the options in the Premier League last season, but there are concerns over their fit. Both are active pressers who look to make intelligent runs off the ball and get into dangerous positions, and neither of them are associated with a lot of creative passing or dangerous dribbling through midfield. In this regard, there’s a serious case for playing Ruben Loftus-Cheek in the first two games, who has at least shown a penchant for dribbling forward through midfield and generating fast attacking chances for those in front of him. Conversely, against the better sides in the knockout stages, Fabian Delph has a strong argument for playing, having looked comfortable all season in a defensive unit with Kyle Walker and John Stones. As such, a fair amount of mixing and matching throughout the tournament could be the best approach. (Header photo courtesy of the Press Association)

He also routinely feeds balls into the attacking penalty area. He and Kevin de Bruyne excelled at getting the ball in space, turning and sliding players into the attacking Penalty area.

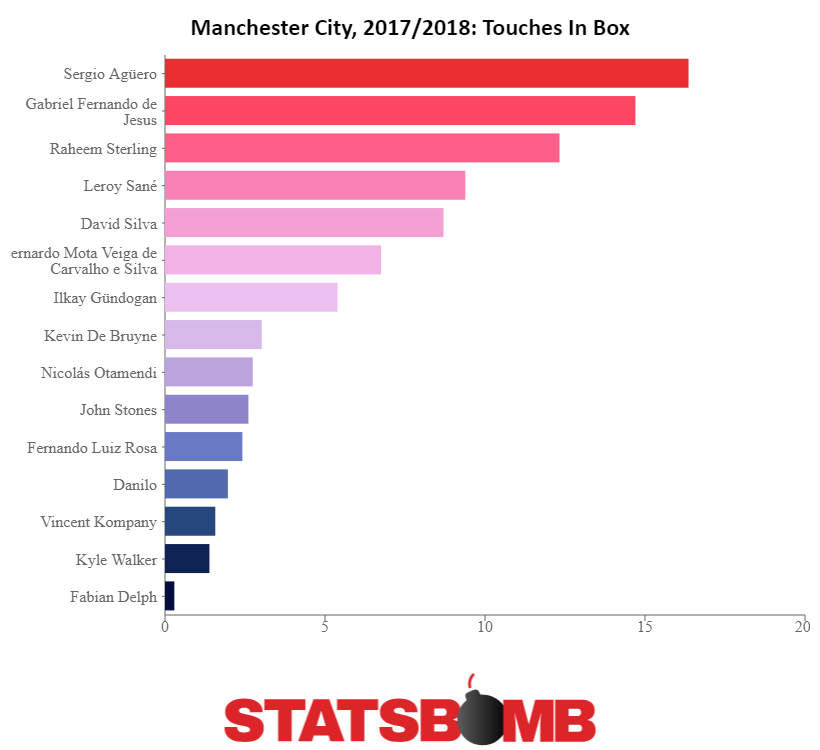

He also routinely feeds balls into the attacking penalty area. He and Kevin de Bruyne excelled at getting the ball in space, turning and sliding players into the attacking Penalty area.  Of Premier League players with over 900 minutes, Silva was fifth with 2.99 open play passes into the penalty area per game. Only Alexis Sanchez (of the Arsenal variety), De Bruyne, Philippe “no longer appearing in this league” Coutinho, and Mesut Ozil had more. It’s clear just how much City relied on the passing of their midfielders. That’s not at all surprising. This is what Pep Guardiola teams do. They get great passers into dangerous areas and then use them to spring goal scorers for great chances. In that manner Silva and De Bruyne look very similar. But, looking at them from a different angle, the midfielders differ to a large degree along another important axis. Silva also has this annoying (for opposing defenses anyway) habit of getting into the penalty area. He takes 8.70 touches in the box per 90 minutes, that’s way more than De Bruyne’s 3.02. It’s much closer to winger Leroy Sane’s 9.38, or even winger and also kind of forward Raheem Sterling’s 12.33 than De Bruyne.

Of Premier League players with over 900 minutes, Silva was fifth with 2.99 open play passes into the penalty area per game. Only Alexis Sanchez (of the Arsenal variety), De Bruyne, Philippe “no longer appearing in this league” Coutinho, and Mesut Ozil had more. It’s clear just how much City relied on the passing of their midfielders. That’s not at all surprising. This is what Pep Guardiola teams do. They get great passers into dangerous areas and then use them to spring goal scorers for great chances. In that manner Silva and De Bruyne look very similar. But, looking at them from a different angle, the midfielders differ to a large degree along another important axis. Silva also has this annoying (for opposing defenses anyway) habit of getting into the penalty area. He takes 8.70 touches in the box per 90 minutes, that’s way more than De Bruyne’s 3.02. It’s much closer to winger Leroy Sane’s 9.38, or even winger and also kind of forward Raheem Sterling’s 12.33 than De Bruyne.  The combination of playing a lot passes into the box and also getting a lot of touches in the box is a rare one. Usually high numbers of touches in the box are the provenance of out and out strikers. Guys like Sergio Aguero, Harry Kane and Alexander Lacazette led the league this season along with Mohammed Salah who while not a pure striker was mostly a god, so he gets included. They were the only four players to get over 15 touches a game. But, when you narrow down the list to looking at players who both create and get into the box something interesting happens. There were only four Premier League players last season who had both more than two open play passes per 90 into the penalty box and more than eight touches in the penalty area. Silva, Sanchez, Sadio Mane, and Eden Hazard. In that company David Silva looks less like a midfielder and more like a winger who has been crammed into the midfield. There are important differences, of course. Silva is a much less prolific shooter than the other guys. He shot only 2.09 times per 90 minutes, even Hazard, who is the second least shot happy of the group shot it 2.50 times. And all these other wingers seem to spend lots of time in the box because they dribble the ball there. Silva seems to show up by magic. He only completed 0.66 dribbles per 90, the rest of them were all over 1.5 with Sanchez the highest at 3.25.

The combination of playing a lot passes into the box and also getting a lot of touches in the box is a rare one. Usually high numbers of touches in the box are the provenance of out and out strikers. Guys like Sergio Aguero, Harry Kane and Alexander Lacazette led the league this season along with Mohammed Salah who while not a pure striker was mostly a god, so he gets included. They were the only four players to get over 15 touches a game. But, when you narrow down the list to looking at players who both create and get into the box something interesting happens. There were only four Premier League players last season who had both more than two open play passes per 90 into the penalty box and more than eight touches in the penalty area. Silva, Sanchez, Sadio Mane, and Eden Hazard. In that company David Silva looks less like a midfielder and more like a winger who has been crammed into the midfield. There are important differences, of course. Silva is a much less prolific shooter than the other guys. He shot only 2.09 times per 90 minutes, even Hazard, who is the second least shot happy of the group shot it 2.50 times. And all these other wingers seem to spend lots of time in the box because they dribble the ball there. Silva seems to show up by magic. He only completed 0.66 dribbles per 90, the rest of them were all over 1.5 with Sanchez the highest at 3.25.

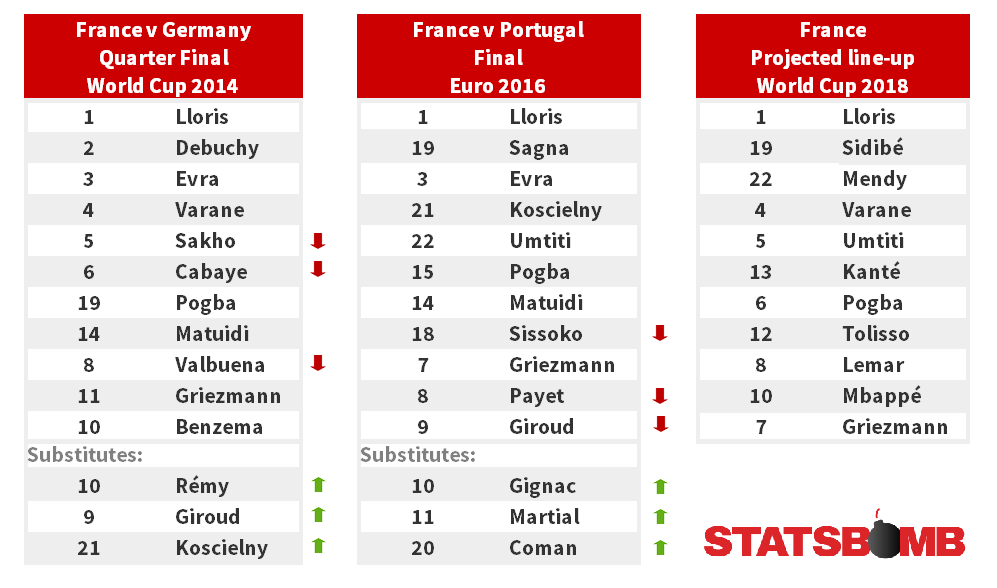

Of the starting 11, only Paul Pogba, Antoine Griezmann and Hugo Lloris are constants. It’s also possible to make the argument Blaise Matuidi will start this time around, but at the same time the only reason Griezmann started in 2014 was that Franck Ribery was hurt in the run-up to the Cup. Additionally none of the three subs who appeared in the final two years ago are on this squad. A full three quarters of the back line has changed. Samuel Umtiti is the only holdover. Four starters from two years ago, Bacaray Sagna, Patrice Evra, Moussa Sissoko and Dmitri Payet aren’t even on the squad. That’s not unreasonable. Sagna and Evra were old, even in 2016. Sissoko wasn’t very good then, and he’s still not very good now, and Payet is hurt or he certainly would have been in Russia. But it’s still a lot of turnover. Looking at it from a squad wide standpoint, only ten players played both in 2016 and made the current squad. Only five players were members of the 23 man squad in 2014, 2016 and 2018. This isn’t an issue limited to France either. Germany has only twelve holdovers from their squad two years ago. Eight players, so roughly a third of the team, have played in all three tournaments. Spain, the paragon of consistency over the years has only ten players in their squad from two years ago and nine that played in all three tournaments. This is just kind of how the international game works. This shouldn’t be surprising of course, football is a game that’s constantly in motion. Four years ago Liverpool were coming off a miracle second place season and contemplating life without their megastar Luis Suarez. This year they reached the Champions League final without Suarez, and the three other biggest attacking forces from the 2013/14 team, Raheem Sterling, Philippe Coutinho, and Daniel Sturridge. Things change fast.

Of the starting 11, only Paul Pogba, Antoine Griezmann and Hugo Lloris are constants. It’s also possible to make the argument Blaise Matuidi will start this time around, but at the same time the only reason Griezmann started in 2014 was that Franck Ribery was hurt in the run-up to the Cup. Additionally none of the three subs who appeared in the final two years ago are on this squad. A full three quarters of the back line has changed. Samuel Umtiti is the only holdover. Four starters from two years ago, Bacaray Sagna, Patrice Evra, Moussa Sissoko and Dmitri Payet aren’t even on the squad. That’s not unreasonable. Sagna and Evra were old, even in 2016. Sissoko wasn’t very good then, and he’s still not very good now, and Payet is hurt or he certainly would have been in Russia. But it’s still a lot of turnover. Looking at it from a squad wide standpoint, only ten players played both in 2016 and made the current squad. Only five players were members of the 23 man squad in 2014, 2016 and 2018. This isn’t an issue limited to France either. Germany has only twelve holdovers from their squad two years ago. Eight players, so roughly a third of the team, have played in all three tournaments. Spain, the paragon of consistency over the years has only ten players in their squad from two years ago and nine that played in all three tournaments. This is just kind of how the international game works. This shouldn’t be surprising of course, football is a game that’s constantly in motion. Four years ago Liverpool were coming off a miracle second place season and contemplating life without their megastar Luis Suarez. This year they reached the Champions League final without Suarez, and the three other biggest attacking forces from the 2013/14 team, Raheem Sterling, Philippe Coutinho, and Daniel Sturridge. Things change fast.